Introduction

Authoritarian regimes pose unique obstacles to legal mobilization, particularly in contexts where state power is wielded to suppress dissent and control civil society. Activists in such settings risk violence, severe legal sanctions, and personal persecution (Currier Reference Currier, Bernstein and Marshall2009; Fu and Distelhorst Reference Fu and Distelhorst2018; Lemaitre and Sandvik Reference Lemaitre and Sandvik2015; Van der Vet Reference Van der Vet2018). Access to justice is further constrained by narrow standing rules and the systematic incapacitation of cause lawyers (Ghias Reference Ghias2010; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2014; Rajah Reference Rajah2012). Beyond these direct forms of repression, civil society organizations encounter significant operational hurdles, including restrictions on fundraising, limits on networking with international allies, and censorship of publicity efforts (Bromley et al Reference Bromley, Schofer and Longhofer2020; Chua and Hildebrandt Reference Chua and Hildebrandt2013; Lei Reference Lei2018).

In recent years, the global rise of autocratic or authoritarian legalism – a system in which legal frameworks are manipulated to legitimize state control – has introduced an even more insidious challenge: co-optation (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018; Tushnet Reference Tushnet2014). States increasingly deploy NGO management laws to categorize activist groups as either “untrustworthy” or compliant, tightening administrative oversight and severing ties with foreign civil society actors (Bromley et al Reference Bromley, Schofer and Longhofer2020; Toepler et al Reference Toepler, Zimmer, Fröhlich and Obuch2020). At the same time, official funding programs incentivize NGOs to shift from advocacy to apolitical welfare provision, effectively neutralizing their potential for dissent (Dirks and Diana Reference Dirks and Diana2023; Fröhlich and Skokova Reference Fröhlich and Skokova2020; Spires Reference Spires2020). This dual strategy of suppression and co-optation raises a critical question: can legal mobilization survive in such environments, and if so, what are the consequences?

This study examines the transformation of environmental public interest lawyering in China against the backdrop of expanding authoritarian legality. It introduces the framework of “guerrilla lawyering” as both a product of and response to the narrowing space between state suppression and co-optation. Drawing on in-depth interviews and participant observations, the research investigates how the focus on survival and autonomy has driven guerrilla activists to employ adaptive and innovative tactics when engaging with the legal system. Guerrilla lawyering relies on loose, decentralized networks of a broad coalition between lawyers and nonlawyer activists who share knowledge and resources for legal mobilization. This approach fosters agility and resilience while remaining elusive to state surveillance and crackdowns. The adaptability of guerrilla lawyering is enhanced by a “learning through combat” philosophy, where each legal engagement, win or lose, serves as a reconnaissance mission to uncover vulnerabilities in the legal system and refine tactics for future resistance. Similarly, flexible funding and media strategies are crafted to complement the hit-and-run approach, utilizing crowdfunding to increase financial resilience and diffused online mobilization to mitigate the risk of state censorship. Together, these innovative strategies not only sustain the movement amid tightening authoritarian legality but also highlight the ingenuity and tenacity of activists pushing the boundaries of legal advocacy in a constrained environment.

The emergence of guerrilla lawyering underscores profound divisions within China’s environmental movements, divisions that have been intensified by authoritarian legal reforms. Conventional environmental lawyering adheres to a law-centric approach, emphasizing strict compliance with state regulations, such as standing rules and court procedures, and focusing on impact litigation as a mechanism for achieving incremental policy reform. In contrast to conventional, lawyer-centered and law-centered approaches, guerrilla lawyering prioritizes collaboration between lawyers and non-lawyer activists and actively incorporates extra-legal tactics, such as social media campaigns, alongside litigation. Guerrilla lawyering frequently circumvents procedural requirements, by using “shell” organizations to file lawsuits and avoiding clear compensation claims to reduce costs. Meanwhile, it embraces an experimentalist attitude toward litigation, prioritizing agility over the pursuit of landmark cases. The division between conventional and guerrilla lawyering can be attributed to their different movement goals and attitudes towards the state. While conventional lawyering seeks to effect change from within the system, guerrilla lawyering, though recognizing that “law is the only game in town,” strives to avoid the pitfalls of co-optation (Halliday and Morgan Reference Halliday and Morgan2013). These observations contribute to the burgeoning body of scholarship examining the divisions among activist lawyers in authoritarian settings (Hendley Reference Hendley2017; Mustafina Reference Mustafina2022; Pils Reference Pils2014).

Guerrilla lawyering significantly enriches the theoretical framework of legal mobilization under authoritarianism by illuminating how activists strategically navigate the dual threats of state suppression and co-optation, thereby extending beyond the pragmatic survival strategies documented in prior scholarship. Drawing on studies like Chua (Reference Chua2012) and Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2017), which emphasize pragmatic gains and movement persistence in repressive contexts, and McEvoy and Bryson (Reference McEvoy and Bryson2022), which explore legal activism under constraint, guerrilla lawyering introduces a novel dimension: the dual notion of survival – sustaining the movement through evading crackdowns and securing resources while preserving an independent identity and the autonomy to dictate its own agenda and tactics. Through innovative tactics such as hit-and-run litigation, reliance on decentralized, individual-based networks, and a “learning through combat” strategy, guerrilla lawyering transforms courts into spaces for generating critical information and exposing systemic vulnerabilities, rather than solely pursuing legal victories. This strategic engagement not only addresses the understudied risk of co-optation but also offers a model of legal mobilization that resists assimilation into state-controlled frameworks. By integrating these insights, guerrilla lawyering provides a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how legal activism adapts and thrives amid expanding authoritarian legality.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section “Cause Lawyering and Environmental Legal Mobilization in China” reviews the literature on cause lawyering and environmental legal mobilization, with a particular focus on China. Section “The Context: China’s Changing Legal Landscape and Its Impact on Environmental Litigation” examines China’s legal reforms since 2012, which have aimed to strengthen authoritarian legality. Section “Data and Methods” describes the data and methods used in this research. Sections “The Conventional Model: Impact Litigation as Professional Advocacy” and “Guerrilla Lawyering: Motivations and Tactics” present and discuss the empirical findings, focusing on the conventional and guerrilla models of environmental lawyering. The final section concludes by reflecting on the broader implications of guerrilla lawyering for understanding resistance under authoritarianism.

Cause lawyering and environmental legal mobilization in China

Cause lawyers are those who utilize legal skills and institutions in the service of broader social and political transformation, pursuing civil rights, environmental protection, and other causes (Sarat and Scheingold Reference Sarat and Scheingold1998). Early scholarship celebrated impact or test‐case litigation, portraying lawyers as the principle architects of social reform whose courtroom victories dismantled formal barriers to equality (Rabin Reference Rabin1976; Tushnet Reference Tushnet1987). Yet over the past three decades practitioners and scholars have increasingly critiqued this lawyer-centered model. They observe that high-profile rulings often stall at the implementation stage, alienate the very constituencies they aim to benefit, and leave unaddressed the deeper economic or cultural structures that perpetuate injustice (Sarat and Scheingold Reference Austin and Stuart2006; Lobel Reference Lobel2006). Rosenberg’s influential account (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1991) argues that even the most celebrated judicial victories yield limited change unless they coincide with supportive political coalitions, administrative capacity, and sustained public mobilization. Likewise, McCann (Reference McCann1994) demonstrates that coalition building – cultivating allies in legislative, bureaucratic, and community arenas – is critical for translating legal wins into tangible social gains.

More recent work situates cause lawyering at the intersection of lawyer–client relationships and the wider political environment, reframing attorneys not as lone crusaders but as one set of actors embedded in multi-actor struggles (Lynn Reference Lynn, Sarat and Stuart2006; McCann Michael and Silverstein Reference McCann Michael, Silverstein, Sarat and Scheingold1998). In this vein, Marshall and Hale (Reference Marshall and Hale2014) shift the emphasis from “cause lawyers” as individuals to “cause lawyering” as an ensemble of social, professional, political, and cultural practices deployed by lawyers and other agents to mobilize law either to advance or to resist social change. The value of law, from this perspective, lies less in discrete judicial victories than in its capacity to generate incremental policy shifts, raise public consciousness, and strengthen community ties (Lobel Reference Lobel2006). Drawing on social movement theory, contemporary scholarship highlights horizontal alliances between legal professionals and non-lawyer activists, the use of multi-method tactics, and the co-creation of strategy with affected communities in order to build resilient, movement-centered change (Cummings Reference Cummings2017, Reference Cummings2018; McCann Reference McCann2006).

Despite these advances, strategies forged in relatively open societies may prove difficult to transpose wholesale to contexts where both cause lawyering and social movements are subject to tight state control. Systematic repression through surveillance, funding restrictions, and criminal prosecutions severely undermines grassroots mobilization and coalition-building efforts (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2007; Mustafina Reference Mustafina2022; Zhu and Jun Reference Zhu and Jun2022). Equally, rights-based discourse rooted in neoliberal norms often falters in polities dominated by strong ideological oversight or where collective cultural priorities eclipse individual entitlements (Liu and Sitao Reference Liu and Sitao2024; Morag-Levine Reference Morag-Levine, Sarat and Scheingold2001). At the same time, lawyers who adopt more cautious, compliance-oriented tactics to maintain their operating space risk stifling creativity and exposing themselves to state co-optation (Chua Reference Chua2012; Lemaitre and Sandvik Reference Lemaitre and Sandvik2015). China, where legal advocacy and civil society operate under stringent political oversight, epitomizes these tensions. It thus offers a crucial case for investigating how cause lawyering must adapt, both tactically and discursively, to endure and drive change in authoritarian environments.

Since the 1990s, scholars have documented a remarkable expansion of cause lawyering in China (Fu and Cullen Reference Fu and Cullen2008; Michelson Reference Michelson2020). Two interlocking developments made this possible. First, the state promoted “rule by law” as a core element of its modernization and governance agenda. Second, the gradual privatization and commercialization of legal practice generated a professional class both capable of and, in some cases, sympathetic to rights-based work. Within this more permissive space, Chinese cause lawyers have been motivated by vastly different imperatives: some driven by personal exposure to injustice, others influenced by global neoliberal ideals of individual rights, and still others inspired by indigenous norms of socialist egalitarianism (Pils Reference Pils2014; Stern Reference Stern2017). These varied motives have produced a corresponding diversity in tactics – ranging from narrowly technical, procedure-focused litigation to more overtly political strategies that frame individual cases as symptomatic of broader systemic failures (Fu Reference Fu2014).

Fu and Cullen’s (Reference Fu and Cullen2011) influential “weiquan ladder” charts how many cause lawyers’ practices evolved over time: beginning as cautious, rights-assertion interventions and, as confidence and networks grew, moving toward more forceful, confrontational approaches. By the early 2010s, a core cohort of “die-hard” lawyers galvanized by high-profile cases such as the criminal defence for Li Zhuang had begun to organize collective defence alliances. They complemented courtroom advocacy with performative tactics like public protests outside courthouses and “dramaturgical” courtroom strategies aimed at attracting media and public attention (Liu and Halliday Reference Liu and Halliday2019; Pils Reference Pils2018).

Under Xi Jinping, however, these opportunity structures have been dramatically eroded. The 2015 nationwide crackdown on rights lawyers (the “709” campaign) was accompanied by sweeping new regulations: prohibitions on livestreaming or otherwise documenting hearings, harsh sanctions for “disturbing court order,” and the criminal prosecution of high-profile practitioners (Fu Reference Fu2018; Pils Reference Pils2018). At the same time, the state has deployed ostensibly neutral instruments – stringent bar-exam requirements, “outstanding lawyer” awards, and expanded state-funded legal aid – to cultivate a compliant legal profession (Fu Reference Fu2025; Stern and Liu Reference Stern and Liu2020; Xia Reference Xia2024). This dual strategy of repression and co-optation has all but eliminated the political ambivalence that once afforded cause lawyers room to maneuver. Increasingly, lawyers must choose either to align with state-controlled legal aid programs, thereby relinquishing more contentious forms of advocacy, or to risk surveillance, harassment, and imprisonment (Stern and O’brien Reference Stern and O’brien2012; Fu and Zhu Reference Fu and Zhu2017; Zhu and Jun Reference Zhu and Jun2022; O’brien Reference O’brien2023). As a result, the efficacy of cause lawyering in China has been substantially weakened under authoritarian tightening.

Despite the richness of existing scholarship on cause lawyering, two interrelated gaps limit our understanding of the potential of legal activism to navigate or transcend the suppression/co-optation dilemma under authoritarianism. First, most analyses underplay the new openings for legal mobilization that have emerged alongside China’s legal reforms. Over the past decade, for example, Chinese courts have seen greater budgetary and personnel centralization, alongside measures to enhance judicial accountability and professionalization (He Reference He2024; Yueduan Wang Reference Wang2019). At the same time, legislation has broadened standing rules and strengthened statutory protections for property, environmental, and administrative rights (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2017; Wang and Xia Reference Wang and Xia2024).

Environmental public interest litigation (EPIL) illustrates this shift vividly. Before the 2010s, environmental litigation was hampered by restrictive standing rules, which limited lawsuits to direct pollution victims, many of whom were deterred by a lack of legal awareness or economic dependency on polluting enterprises (Van Rooij Reference Van Rooij2010; Wang Reference Wang2006). Judges and lawyers also faced significant challenges, including a lack of expertise and political pressure from local governments (Stern Reference Stern2011, Reference Stern2013). The 2015 introduction of environmental public-interest standing, however, has enabled Chinese environmental NGOs to file over 800 suits, redirecting enforcement, increasing public awareness, and holding polluters to account (Ren and Liu Reference Ren and Liu2020; Xia and Wang Reference Xia and Wang2023; Xiao and Ding Reference Xiao and Ding2023). Meanwhile, fissures in street-level control have prompted women’s rights and LGBTQ + advocates to pursue litigation as one of the few remaining avenues for public mobilization (Parkin Reference Parkin2017; Qi et al Reference Qi, Wu and Wang2020; Wang and Liu Reference Wang and Liu2020). In these fields, courts remain a contested but indispensable site of resistance.

Second, most studies of Chinese cause lawyering remain lawyer-centric, overlooking the indispensable contributions of non-lawyer actors, such as grassroots organizers, investigative journalists, donors, and volunteers – who shape case selection, argumentation, and social mobilization. In the United States, critical scholars have long called for a movement-centered approach that integrates litigation into broader campaigns, thus bridging the divide between lawyers and lay activists (Ashar Reference Ashar2017; Cummings Reference Cummings2018). In China, research has documented how labor NGOs contributed to the legal capacity building of aggrieved workers (Fu Reference Fu2017; Xu Reference Xu2013), but systematic analysis of collaborative networks between law firms, environmental NGOs, and digital media platforms remains scarce. Nor have we fully explored how non-legal tactics like fundraising and volunteer mobilization are employed to sustain legal activism in spite of official restrictions.

To address these lacunae, I propose a theoretical framework grounded in the logic of guerrilla warfare, a strain of strategic thought emphasizing adaptability, surprise, and decentralized initiative when confronting a far stronger adversary. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War counsels concealing one’s strength while identifying and exploiting the enemy’s weaknesses. Mao Zedong later distilled these precepts into a doctrine of protracted struggle in which small units choose their battles, retreat when necessary, and draw on local support to survive and expand (Mao Reference Mao1954). Guerrilla forces stress the importance of speed, improvisation, and local intelligence to evade repression and seize unexpected openings (Perry and Heilmann Reference Perry, Heilmann, Elizabeth and Heilmann2011). In China’s regionally differentiated authoritarian system where fiscal, administrative, and political controls vary markedly from province to province, such guerrilla-style legal activism can exploit uneven implementation to create pockets of relative autonomy (Fu Reference Fu2017; Lieberthal and Lampton Reference Lieberthal and Lampton1992).

By reconceiving cause lawyering as a form of tactical, networked resistance rather than as a set of formalistic or top-down strategies, we can gain better insight into how lawyers and their allies press forward even under intensifying state constraint. Guerrilla lawyering treats the law itself as a tool of resistance, calibrated to evade both direct suppression and gradual co-optation. Unlike earlier models of cause lawyering, which often centered on the legal profession and law-centric tactics, guerrilla lawyering emphasizes close collaboration between lawyers and activists, enabling joint goal-setting and resource sharing. Aware of its vulnerability, guerrilla lawyering deploys flexible, adaptive tactics that pursue pragmatic objectives and seize fleeting openings within an authoritarian regime. China’s EPIL regime, which since 2015 has granted standing to some environmental NGOs, offers a particularly fruitful context for assessing the viability and limits of guerrilla lawyering in an evolving legal landscape.

The context: China’s changing legal landscape and its impact on environmental litigation

Over the past decade, China’s legal landscape has undergone profound transformation, reflecting the state’s evolving priorities and its strategies for consolidating control. Under the Hu–Wen administration (2002–2012), a premium on social stability over strict legal formality created a gray zone between permissible and impermissible actions, an ambiguity within which legal and social mobilization could briefly flourish (O’brien and Li Reference O’brien and Lianjiang2006; Xie Reference Xie2012). Since 2012, however, the Xi Jinping administration has pursued a series of sweeping reforms aimed at narrowing this gray zone and clarifying the boundaries of permissible conduct.

A watershed moment came with the “709 Crackdown” in 2015, when authorities detained over 200 human-rights lawyers and legal activists, coerced many into televised confessions, and in some cases charged them with subversion. This crackdown produced a debilitating chilling effect, discouraging rights‐based litigation and activism (Pils Reference Pils2018; Fu Reference Fu2018). At the same time, Beijing has imposed tighter regulations on the legal profession, outlawing activities deemed to “disturb court order,” including live-streaming hearings or staging protests outside courthouses, which are practices once common among activist lawyers (Liu and Halliday Reference Liu and Halliday2016). Law firms are now required to monitor their attorneys and impose sanctions on those who publish open letters or make statements critical of ongoing cases (Fu and Zhu Reference Fu and Zhu2017). Moreover, reforms to standing requirements have constructed a discriminatory legal opportunity structure that privileges practitioners with state affiliations, induces self-censorship among others, and deepens divisions within the broader community of legal mobilization (Wang Reference Wang2024).

Simultaneously, the state has reinforced its control over social organizations, moving away from the previous policy of “no recognition, no banning, and no intervention” (Deng Reference Deng2010; Shieh Reference Shieh2018). In 2016, the State Council mandated that all local governments tighten the dual management of NGOs, making it mandatory for NGOs to obtain approval from both the Civil Affairs Department and a professional supervisory agency for registration and operations. That same year, the Charity Law increased reporting obligations for NGOs and linked legal compliance with eligibility for fundraising and tax benefits (Dirks and Diana Reference Dirks and Diana2023). In 2017, the Overseas NGO Law further restricted the operation of foreign NGOs, requiring them to register with the Public Security Department and seek prior approval for their activities, including grant-making.Footnote 1 These measures have led many foreign NGOs to scale back or close their operations in China, exacerbating funding shortages for domestic NGOs (Holbig and Lang Reference Holbig and Lang2022; Xia Reference Xia2024). Although environmental protection was traditionally considered a less sensitive issue, the state’s tightening grip has also significantly impacted environmental NGOs. A 2022 survey found that only 15% of active environmental NGOs were registered after 2010, reflecting the growing difficulty of maintaining legal status (Vanke Foundation 2023).

Despite the intensifying repression and scrutiny of grassroots mobilization, judicial reforms and new legislation have arguably opened some space for cause lawyering, particularly for state-sanctioned actors. Centralized reforms have aimed at reducing local political influence over courts, such as transferring control over court personnel and budgets from local to provincial governments (He Reference He2024; Wang Reference Wang2021). The introduction of a case filing system, which replaced the previous case approval process that allowed courts to filter out unwanted cases before hearings, has removed informal barriers to court access (He Reference He2021; Liu and Liu Reference Liu and Liu2010). Moreover, since 2010, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) has overseen the establishment of specialized environmental tribunals in more than 2,800 courts nationwide,Footnote 2 aiming to enhance professionalism and efficiency in environmental adjudication (Wang and Xia Reference Wang and Xia2023; Zhai and Chang Reference Zhai and Chang2018).

In the realm of environmental protection, new legislation has been enacted to bolster legal protections for environmental interests and broaden standing to sue. More national environmental laws were introduced or revised over the past decade than in the previous 30 years. In 2018, the concept of ecological civilization was enshrined in the Chinese Constitution, signaling its legal and political importance (Wang and Xia Reference Wang2024). A new environmental code, currently being drafted, is set to become China’s second code, following the Civil Code. Since 2012, the Civil Procedure Law has granted NGOs standing to initiate civil lawsuits in environmental cases, a provision further detailed in the revised Environmental Protection Law of 2015. This law extends EPIL standing to social organizations that: (1) are registered with a government civil affairs department at the prefecture level or above; (2) have engaged in public interest environmental activities for at least 5 consecutive years; and (3) have not violated laws in the 5 years prior to initiating a lawsuit.Footnote 3

However, the institutionalization of EPIL carries subtle risks of co-optation. The requirements for registration with the prefecture-level Civil Affairs department and the 5-year “work experience” mandate restrict court access for smaller, grassroots environmental groups (Gao and Whittaker Reference Gao and Whittaker2019; Zhai and Chang Reference Zhai and Chang2018). Moreover, the “no violation of law” condition may further entrench state compliance requirements for NGOs, as many courts interpret this clause broadly to include failures to complete annual inspections by the civil affairs department.Footnote 4 Additionally, critics argue that state control over the judiciary and funding mechanisms creates an uneven playing field that favors NGOs working on less politically sensitive issues and adopting moderate advocacy strategies (Wang and Xia Reference Wang and Xia2024). These dynamics raise critical questions about whether Chinese environmental NGOs can resist state co-optation while leveraging the opportunities presented by the expanded legal framework for environmental litigation.

Data and methods

This study employs a qualitative research design, utilizing in-depth interview, participant observations, and online ethnography to investigate the dynamics of environmental activism in China. Between June 2021 and November 2023, I conducted four field trips to China, during which I engaged in semi-structured interviews and participant observations with 49 environmental activists and lawyers.Footnote 5 The goal was to understand their motivations, objectives, and tactics in legal mobilization under authoritarian conditions. To safeguard interviewee identities, I took detailed notes during all interactions and events but refrained from recording them. All names mentioned in this article are pseudonyms.

The interviewees are categorized into two distinct groups: the “conventional camp” and the “guerrilla camp,” each representing different models and networks of activist lawyering. Thirty of the interviewees belong to the conventional camp, while 19 identify with the guerrilla camp. While the conventional litigation cohort consists mostly of credentialed attorneys, the guerrilla camp spans a much broader professional spectrum. Only about a third of guerrilla activists hold legal credentials; the remainder are NGO staff, investigative journalists, fundraisers, and grassroots activists. The characterization is based on both each interviewee’s own self‐identification and how they were described by their peers. Although the distinction is not perfectly rigid – several lawyers now labeled as guerrilla began their careers with more conventional tactics – I found virtually no collaboration between the two camps, since each tends to critique the other’s approach to legal mobilization. To structure my coding framework and interview guide, I focused on five core dimensions: their attitude toward the state, case‐selection strategy, organizational structure, funding sources, and media engagement. The demographic characteristics of these groups, along with the methods employed in studying them, are discussed further below.

The conventional camp is primarily centered around two prominent environmental organizations headquartered in Beijing: Friends of Nature (FON) and the Center for Legal Assistance to Pollution Victims (CLAPV). FON was founded by the late Professor Liang Congjie, a descendant of the late Qing intellectual leader Liang Qichao. As a member of the National People’s Political Consultative Conference, Liang supported a long-lasting policy advocacy for establishing public interest litigation in China (Xia and Wang Reference Xia and Wang2023). After the EPIL system was officially introduced in 2015, FON shifted the focus of its advocacy towards litigation, using impact cases to influence environmental decision-making (Liu Reference Liu2019; Zhuang and Wolf Reference Zhuang and Wolf2021). CLAPV, led by Professor Wang Canca, a renowned environmental law academic, has been collaborating with international foundations and law school clinics for over two decades to promote environmental legal aid in China. Both FON and CLAPV have provided various capacity-building programs to local NGOs and lawyers, including legal training, funding support, and assistance with grant applications. In addition to interviewing management staff and in-house lawyers from both organizations, I also spoke with representatives from six local NGOs that have worked closely with them, as well as the lawyers representing these NGOs in court. Each interview lasted between 30 minutes and 2 hours. My initial contacts with FON and CLAPV were facilitated through Chinese environmental law professors, and I employed the snowball technique to reach other interviewees. I also gained access to court decisions from 64 lawsuits brought by the eight NGOs affiliated with the conventional camp.

In contrast, gaining access to the guerrilla camp was initially more challenging, as several members were hesitant to speak with an outsider. However, an opportunity arose in July 2023 when a friend from a wildlife enthusiast community invited me to join a field trip organized by guerrilla activists to collect evidence for a potential lawsuit. During the grueling eight-hour hike in a remote forest, I engaged in extensive discussions with several guerrilla activists on topics ranging from outdoor adventures to social movements and political philosophy. This interaction not only built trust but also provided a unique window into their worldviews and operational strategies. After this experience, they agreed to my request to stay on for participant observation. Over the following weeks, I became recognized as a “zijiren” or insider within their community (Hsiao-Tan Wang Reference Wang2019), which allowed me to engage in deeper conversations and explore the first-person narratives of their work and beliefs. I completed over 146 hours of field observations, which included attending trial proceedings, participating in site visits, and observing internal meetings and semi-public workshops. Additionally, I conducted one-on-one interviews with 19 core members of the guerrilla camp, including lawyers, journalists, NGO staff, and volunteers.

Given that the guerrilla camp operates primarily through individual-based networks rather than formal organizations, providing an exact count of the group’s size is difficult. Nonetheless, my experience during internal meetings indicated that in addition to the core members, many volunteers have participated in case proceedings, conduct on-site investigations, circulate information via social media, and advise on environmental science and engineering matters. These volunteers often hail from diverse backgrounds, including performative artists, ecological experts, and animal rescuers. Guerrilla activists’ online workshops and discussions relating to specific cases typically attract 20 to 80 attendees. While both the conventional and guerrilla camps engage in litigation activities across various regions of China, there are significant differences in their internal structures of operation. The conventional lawyering group operates with a more hierarchical structure, with FON and CLAPV leading advocacy efforts and providing support to smaller NGOs. In contrast, the guerrilla lawyering group functions through more decentralized and flexible networks, with most participants acting in their personal capacities.

To complement the interviews and participant observation, my research assistant and I conducted online ethnography to gather additional insights into the guerrilla camp. We analyzed 32 trial recordings, totalling 108 hours, related to lawsuits filed by the guerrilla activists. Of these, 25 were publicly available on the official website of China Court Trials Online, while the remainder were provided by the interviewees. We also monitored their activities on Chinese social media platforms, including WeChat and Weibo. Unlike members of the conventional camp, who typically use their own accounts for social media engagement, guerrilla activists adopted a “diffused” social media strategy, relying on multiple alternative accounts for posting and reposting contents. Using the snowball technique, we identified 24 social media accounts and 650 articles relevant to the guerrilla activists. However, this method may not guarantee exclusivity or completeness. Based on the official database from Court Judgment Online, social media posts, and internal records shared by interviewees, we confirmed that the guerrilla activists collectively brought over 200 EPIL lawsuits between 2015 and 2023. This constitutes approximately a quarter of all officially reported NGO-led EPIL cases in China, which is a notably high proportion given the relatively small size of the guerrilla camp.

The conventional model: impact litigation as professional advocacy

The conventional model of environmental lawyering centers on the strategy of impact litigation, which seeks to address systemic issues and influence law and policy through high-profile court cases. A key tenet of this approach is the alignment of litigation efforts with state priorities, which is considered essential for enhancing the legal and political influence of NGOs (Interview, Bo, NGO staff, August 2021). For instance, in 2016, the central government introduced a 5-year action plan to combat soil pollution. Viewing this as an opportunity to influence government policy, FON filed the Changzhou toxic school case, in which hundreds of students fell ill after attending a school built on a toxic waste dump. This case not only highlighted the lack of liability frameworks for soil pollution incidents but also garnered significant public attention, enabling FON to participate in consultations for the new Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law and successfully advocate for the inclusion of the “polluter pays” principle in the final version of law (Sixth Tone, April 16, 2021).

In addition to leveraging the synergy between litigation and lawmaking, the conventional model emphasizes consensus building with state institutions and officials (Ren and Liu Reference Ren and Liu2020). Since the early 2000s, CLAPV has organized environmental law training programs for legal professionals across China, including many environmental judges. These programs have fostered relationships between activists and the judiciary, reportedly making CLAPV-trained judges more receptive to hearing NGO-led environmental cases (Interview, He, Lawyer, June 2021). Furthermore, several NGOs in the conventional camp have signed memoranda of understanding with local procuratorates to facilitate cooperation in public interest litigation. For two of the interviewed organizations, local procuratorates have served as litigation supporters in a majority of their lawsuits,Footnote 6 assisting with evidence collection and environmental appraisals (Interviews, Peng and Ying, NGO staff, 2023).

Another common practice within the conventional model is the involvement of local legislators and environmental bureau officials in public interest work. These personal networks have been instrumental in securing funding for environmental NGOs. Many of the interviewed organizations in the conventional camp have received public procurement contracts for conducting research and environmental inspections, which account for 20–30 percent of their income (Interview, Jun, NGO staff, August 2022). Additionally, officials sympathetic to environmental causes have proven valuable allies in the lawmaking process, collaborating on legislative proposals and providing policy recommendations within the party-state apparatus (Interview, Bo, NGO staff, August 2021). Political connections have also been used to enhance the symbolic legitimacy of these NGOs. For example, one interviewee, who heads an NGO in Jiangxi, leveraged his personal network to register a volunteer group under the local Communist Youth League and operated under its name when necessary (Interview, Dan, NGO staff, October 2023). Another NGO operates from an office within the local environmental bureau, which is used for negotiations with polluting enterprises (Interview, Lin, NGO staff, September 2023).

While alliances with state actors are widely regarded as the most effective strategy for environmental legal mobilization in the conventional model, this approach has had significant effects on its litigation tactics. One consequence is case screening. Several NGOs reported instances where they were pressured to withdraw from controversial cases due to local government interference. An interviewee from Hubei mentioned a case in which he was pressured to “voluntarily withdraw” the lawsuit by both the local government and the court, because the government was worried about the negative publicity while the court was concerned that a protracted lawsuit will impact its case conclusion rate (Interview, Lin, NGO staff, September 2023). To avoid future conflict, the organization decided to report to and seek approval from the local environmental and civil affairs bureaus before filing lawsuits.

Additionally, the conventional model is cautious about engaging in public advocacy. Many interviewees described the media as a “double-edged sword” and preferred to collaborate with state-owned newspapers, which are viewed as more politically credible. In social media engagements, they emphasized avoiding sensitive topics, such as discussing ongoing court proceedings or criticizing judicial officials (Interview, Deng, NGO staff, August 2023). In one case, an NGO that had previously used social media to expose environmental pollution ceased this activity after receiving social service contracts from local environmental bureaus. The organization now believes that leveraging investigation reports in government-mediated negotiations is more desirable than litigation or social media mobilization, especially when the latter risks straining relationships with the government (Interview, Jun, NGO staff, August 2022).

Moreover, the “no violation of law” requirement for public interest standing has led many of the interviewed organizations to place increasing emphasis on legal compliance for NGOs. This was particularly evident in a recent controversy in which an NGO lost its standing to sue after receiving an administrative warning from the Ministry of Civil Affairs for alleged violations of fund management regulations. Reactions from the environmental activist community reflected two divergent perspectives. Supporters of the NGO, including many guerrilla activists, viewed the administrative warning as a pretext to punish the organization for filing lawsuits that embarrassed the government and deter others from pursuing future litigation (Online workshop, Green Development Foundation, December 2022). In contrast, members of the conventional camp stressed the importance of strengthening legal compliance and enhancing the reputation of NGOs, often invoking the Chinese proverb, “it takes a good blacksmith to make good steel (打铁还需自身硬)” (Online workshop, The Air Hero, December 2022). While acknowledging the existence of informal barriers to court access in certain regions, they attributed these challenges to individual judges’ lack of legal expertise or experience and reaffirmed their confidence in the progress of China’s evolving environmental rule of law. When it comes to legal representation, the conventional camp prefers full-time public interest lawyers who are considered to have greater expertise and devotion to public interest litigation than commercial lawyers who deal with environmental cases on the side. FON now handles all its lawsuits through its in-house legal team, while the less resourceful local NGOs file many of their cases in collaboration with lawyers at FON and CLAPV.

The focus on legal compliance and professional integrity also contributes to driving the divisions between the conventional camp and activists and groups seen as politically risky and reputationally tainted. For instance, Xiang, who has now become a leading lawyer member of the guerrilla camp, was once an active member of FON’s volunteer community and collaborated with FON on two EPIL lawsuits. However, they eventually drifted apart due to “differences in values and methods” (Interview, Xiang, Lawyer, September 2023). FON colleagues were concerned that Xiang’s use of social media strategies might compromise legal professionalism and increase the risk of suppression, while Xiang perceived FON as being excessively conservative and inflexible due to its fear of jeopardizing government relations. After the conclusion of the second lawsuit in 2020, they have never worked together.

Guerrilla lawyering: motivations and tactics

Unlike the conventional model, which emphasizes coordination with state actors, guerrilla lawyering is determined to navigate the precarious terrain between state suppression and co-optation. Over the past decade, many environmental activists have shifted away from public advocacy, either voluntarily or under duress, due to the chilling effect of crackdowns and a growing sense of futility in effecting change. In this context, guerrilla activists stress movement survival as a key mission, employing a pragmatic approach to litigation that prioritizes managing political risks and securing financial support (Halliday and Morgan Reference Halliday and Morgan2013). At the same time, they are deeply critical of the co-optation effects of court-centric strategies, viewing legal formality as a threat to the operational and ideological autonomy of social movements. The ultimate objective of guerrilla lawyering is to leverage the legal process to advance movement goals while guarding against the legal system’s potential to co-opt their agenda or dilute their original intent.

To pursue these objectives, guerrilla lawyering emphasizes mobile resistance in their tactics concerning organization, litigation, fundraising, and media engagements. Instead of relying on formal organizations, guerrilla lawyering underscore relies of informal, individual-based networks to reduce operational cost and circumvent formal legality restrictions. Furthermore, guerrilla lawyering refuses the impact litigation strategy and takes an experimentalist stance toward litigation, viewing it as a learning process to generate otherwise inaccessible information, discern informal rules, and identify vulnerabilities with the state system. Meanwhile, flexible funding strategies such as crowdfunding and diffused media engagements are used to enhance financial self-reliance and divert state surveillance and censorship.

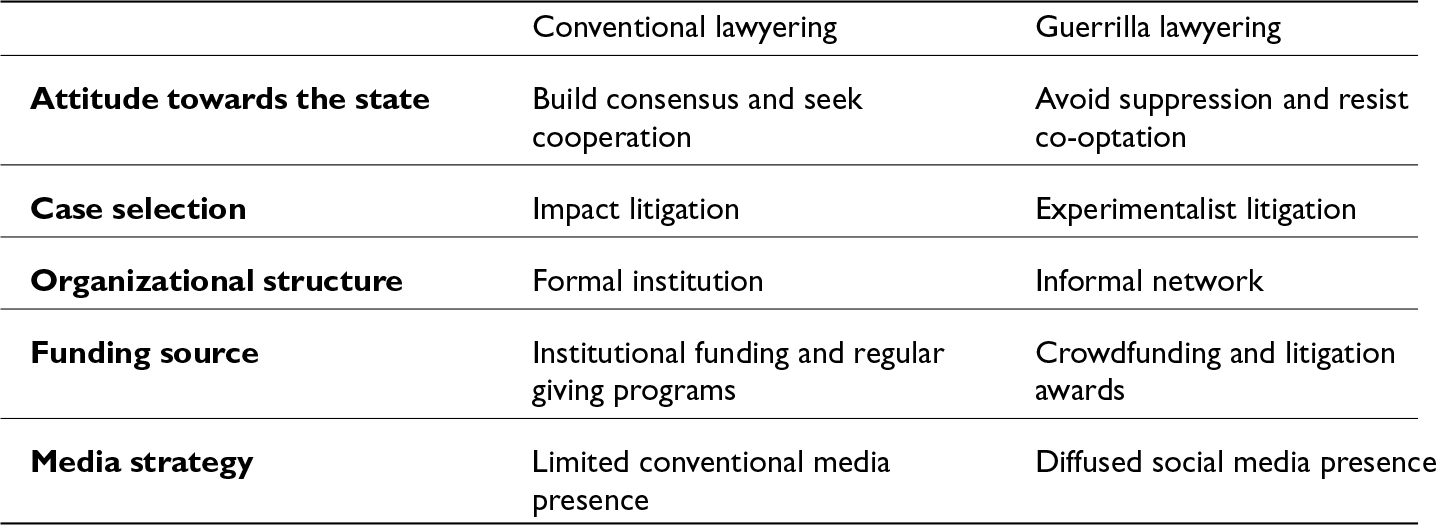

Table 1 provides a comparison between conventional and guerrilla lawyering. Conventional lawyering typically seeks to build consensus with government bodies and foster cooperative relationships, concentrating its efforts on a limited number of high-profile “impact” cases. Practitioners operate within formal institutions, such as legal aid clinics or established NGOs, with stable budgets, and they maintain a relatively restrained presence in traditional media. Guerrilla lawyering, by contrast, adopts a more adversarial posture toward the state, by resisting both co-optation and suppression, and experiments with novel claims and strategies through numerous litigations. Guerrilla attorneys mobilize through loose, informal networks, fund individual cases through crowdfunding and litigation awards, and leverage a diffused, real-time social media strategy to rally grassroots support and shape public narratives.

Table 1. Features of conventional lawyering vs guerrilla lawyering

Navigating suppression and co-optation

Guerrilla activists operate with a heightened awareness of the risks posed by state suppression. Over the past decade, numerous activists and groups have exited the field of advocacy due to the chilling effect of crackdowns and diminished confidence in their ability to catalyze social change. Environmental groups face increasing scrutiny in obtaining and maintaining legal registration. For example, one environmental NGO in Yunnan ceased operations after failing to obtain registration, a failure arguably linked to its prior involvement in the grassroots Nu River anti-dam movement (Interview, Gang, former NGO staff, October 2023). Similarly, a Guangdong-based NGO was labelled an “untrustworthy organization” for not reporting its collaboration with a foreign NGO, leading to increased administrative monitoring and the withdrawal of funding from various sources (Interview, Chun, NGO staff, March 2024). Investigative journalists, once active in environmental advocacy, are also under tighter control. Two of the five interviewed journalists resigned and moved overseas after their reports were censored (Interviews, Shuo and Li, Journalists, 2024). Another retired early, and a fourth shifted to less sensitive topics like technology (Interviews, Chen and Xin, Journalists, 2023). These departures motivate guerrilla activists to prioritize survival and exploit litigation as a feasible alternative to street-level mobilization. As one interviewee noted, “law is the only game in town now” (Interview, Feng, journalist, April 2024).

With the tightening of state control, law has become a vital means of mitigating political and legals risks for environmental activism. Environmental NGOs often endure routine harassment from public security officers who label them “troublemakers” (Interview with Jian, NGO staff, October 2023). Individual activists and volunteers have even been sued for defamation or prosecuted under the catch-all criminal offence of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” (Ye Reference Ye2021). Against this backdrop, Qin, who conducts site investigations for EPIL lawsuits, argues that “lawyering up” is both effective and necessary to protect activists and their cause. As he explains: “Grassroots activists are the most vulnerable. It is so common for police to threaten us with fines, license revocation, and detention to prevent us from exposing environmental violations. However, the moment we mention having legal representation, they tend to think twice before issuing such threats” (Interview, Qin, Volunteer, August 2023). Qin’s views, along with those of other interviewees, reflect what the literature describes as defensive legal mobilization, or the use of law as a shield (Sarat and Scheingold Reference Austin and Stuart2006; Mustafina Reference Mustafina2022).

While survival is paramount, guerrilla lawyering places equal, if not greater, emphasis on preserving autonomy. Activists perceive the legal system as designed to fragment civil society and align it with state priorities through legality requirements and government funding. To counter these co-optation effects, guerrilla lawyering prioritizes operational autonomy, particularly the freedom to set its own agenda and choose tactics. This requires circumventing legal and political restrictions on civil society and securing alternative funding sources. Additionally, guerrilla lawyering seeks to sustain a collective identity independent of the state, using court proceedings as interaction rituals that generate emotional energy and reinforce movement solidarity (Collins Reference Collins and Goodwin2001; Jasper Reference Jasper2011). Such efforts of collective memory-making are especially vital as the space for resistance narrows under authoritarian conditions (Johnson Reference Johnson2023; McEvoy and Bryson Reference McEvoy and Bryson2022). Occasional courtroom victories, whether in case registration, perceived triumphs in debates, or favorable decisions, provide the moral satisfaction needed to sustain participation. For example, Xiang felt empowered after being expelled from a courtroom for challenging a judge’s impartiality, realizing that his anger resonated with observers (Interview, Xiang, lawyer, December 2023). Similarly, Nan described a transformative moment when she faced a hostile judge, quoting, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” (Interview, Nan, lawyer, September 2023). Thus, guerrilla lawyering focuses less on catalyzing broad change and more on resisting assimilation, living to fight another day.

Informal networks of coordination

In contrast to the conventional model, which prioritizes reputation building and legal compliance, guerrilla lawyering views organizational formality as a barrier to flexibility and autonomy. Instead, it relies on informal, trust-based networks where core members take on specialized roles: Meng handles investigations, Xiang provides legal representation, Qi leads fundraising, and Feng manages media relations. Rather than establishing institutionalized cooperations, they collaborate through a case-based alliance, working together on evidence collection, strategy development, and resource mobilization whenever a case arises. This informal network of coordination is favored for its flexibility and cost-effectiveness.

While recognizing the instrumental value of public interest standing, guerrilla activists are critical of the legality requirements imposed on NGOs as prerequisite for gaining access to court. One activist, Jian, argued that the legality requirement is employed by the state to keep “untrustworthy” organizations and undesirable cases out of the court, citing the common practice of local governments to use threats of deregistration to compel NGOs to withdraw or settle EPIL lawsuits (Interview, Jian, NGO staff, October 2023). To circumvent such legal constraints, guerrilla lawyering uses NGOs instrumentally – as “shells” for court access – while avoiding reputational ties that attract scrutiny. Over half of the interviewed guerrilla activists possess two or more NGOs, which enable them to substitute plaintiffs if one loses standing.

This is made possible by bureaucratic fragmentation and local variations in implementing national laws. For example, local governments have interpreted the Charity Law differently on the requirements for obtaining consent from a professional supervisor as a precondition for NGO registration. Cities such as Chongqing and Shenzhen have been more lenient, allowing environmental NGOs to register without professional supervision (Interviews, Jie, NGO staff, 2023-2024). Conversely, Beijing enforces additional, unofficial restrictions on NGO registration, including mandating party membership and requiring social organizations to support investment promotion goals (Interview, Yu, former NGO staff, April 2024). Moreover, relationships with individual officials are often deemed more important than adherence to formal legal rules. For instance, when the environmental bureau rejected Yuan’s initial registration attempt for an environmental NGO, citing a policy of allowing only one NGO in the sector, he approached the justice bureau and secured registration with its support (Interview, Yuan, lawyer, October 2023).

To expand their access to court, guerrilla activists also actively recruit NGOs nationwide to serve as plaintiffs or co-plaintiffs, using personal networks and online appeals. In seeking collaborators, Qi deliberately targets organizations with controversial reputations, contending that “in China, scandals often suggest these organizations have taken bold stands and are more likely to speak out fearlessly” (Interview, Qi, foundation manager, March 2024). Qi himself has switched affiliations four times over the past decade, driven by political pressure on his organizations. He remarked, “This is the cost of pursuing my goals. If I were limited to government-approved projects, I would have left the public interest sector and returned to entrepreneurship” (Interview, Qi, foundation manager, March 2024).

These informal, flexible networks enhance strategic coordination and bolster the movement’s resilience. Since NGOs are vulnerable to interference from local civil affairs departments that control registration, guerrilla activists frequently enlist non-local NGOs to file lawsuits in specific regions (Interview, Jian, NGO staff, October 2023). Interviewees from Hubei and Jiangxi even agreed to exchange plaintiff roles in several cases (Interview, Liu, NGO staff, September 2023). This “litigant shopping” tactic enables local organizations to act as anonymous partners, assisting with evidence gathering and field investigations while shielding them from political repercussions. Another tactic to counter local protectionism involves naming multiple organizations as co-plaintiffs, making it harder for government agencies and defendants to apply extra-legal pressure. For example, Jie described a situation where a local party organ pressured him to withdraw a water pollution lawsuit. He refused and deflected the blame onto two non-local co-plaintiffs, claiming they were unwilling to withdraw (Interview, Jie, NGO staff, November 2023).

Experimentalist litigation

When engaging with the legal system, guerrilla lawyering follows a “learning through combat” approach, viewing litigation as a process to generate information that is otherwise inaccessible, and identify implicit rules and weaknesses within the authoritarian regime. In China, access to information is both vital and challenging in environmental litigation, where local governments and industrial actors frequently withhold essential documents. For instance, in a case involving a proposed hydropower project that allegedly threatened the critical habitat of the endangered Sichuan Taimen fish, the government approved the project without publicizing the required environmental impact assessment. During a court-ordered investigation, activists obtained a copy of the study, which revealed that the environmental bureau deemed a captive breeding program sufficient to mitigate the project’s impact. Leveraging this finding, the activists refined their litigation strategy and are now preparing an administrative lawsuit to challenge the assessment, contending that effective mitigation must include the successful reintroduction of captive-bred fish into the wild (Interview, Jie, NGO staff, November 2023).

In a separate case, guerrilla lawyering practitioners sued a tourist company for abusing elephants during training for public performances. The defendant initially argued that all elephants were legally imported from Laos under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, rendering them exempt from China’s Wildlife Protection Law. However, evidence from the company’s own submissions uncovered by the plaintiffs showed that at least two rescued wild elephants had been trained to play soccer. Although this discovery did not sway the court’s ruling, media coverage of the proceedings triggered widespread online debate about banning elephant performances due to their association with animal abuse. This public reaction reportedly influenced the Yunnan Provincial government’s eventual decision to prohibit such performances.Footnote 7

Experimentation also proves essential in exposing vulnerabilities within the official system. Nan shared an anecdote demonstrating how she exploited the state’s censorship mechanisms to counter a local court’s delaying tactics:

In one instance, I had a case registration pending at a court in Henan for three months. I posted an open letter on WeChat addressed to the court president. Within four hours, the head of the case registration division called me, profusely apologizing for a technical mix-up that had caused the delay and assuring me it would be resolved promptly. He then asked me to remove the post. The next day, after receiving confirmation of the case registration, I deleted it. I was astonished by their swift response, given that the post had fewer than 300 views. After similar experiences, we deduced that the courts’ internal public opinion monitoring teams had flagged the posts, prompting preemptive action to avert a potential backlash. This insight increased our confidence, revealing that even the mere perception of public attention, rather than actual scrutiny, could spur action (Interview, Nan, lawyer, October 2023).

Guerrilla lawyering’s emphasis on volume contrasts with the conventional model’s reliance on impact litigation. While the latter focuses on high-profile cases that have the potential of bringing about policy change, guerrilla lawyering shows less regard for the symbolic significance of individual lawsuits. Many of its cases address small-scale, routine industrial pollution incidents, which conventional practitioners consider to have limited regulatory value for driving legal innovation or systemic reform. Critics further contend that this preference for quantity over quality has resulted in many opportunistic and frivolous lawsuits, potentially undermining the legitimacy of the EPIL system (Interview, Ma, NGO staff, February 2023; Interview, Wen, lawyer, June 2023).

Unfazed by such criticism, guerrilla lawyering prioritizes action over selectivity. Most guerrilla activists harbor skepticism about the progressive evolution of China’s legal system. As Xiang remarked, “Major cases are determined by politics, medium-sized cases by guanxi, and small cases by luck (大案看政治, 中案看关系, 小案看运气)” (Online workshop, Xiang, November 2023). He stressed, however, that persistence and luck are crucial for advancing public causes when opponents – defendant companies and their party-state allies – wield substantial financial, legal, and political advantages (Interview, Xiang, lawyer, December 2023). Thus, rather than pursuing systemic change through a handful of landmark cases, guerrilla lawyering adopts a human wave tactic, rallying support from diverse stakeholders whenever and wherever opportunities emerge. In several guerilla-led lawsuits advocating for animal welfare protection, volunteered from across China have come to assist with evidence collection and attend the hearings as a demonstration of moral support. Other stakeholders include performative artists who have designed creative art projects to raise public attention to ongoing trials. For example, during the hearing of the elephant abuse case, an art professor from an American university launched an interactive digital experience to display a 3D model of a scarred elephant in front of the courthouse.Footnote 8 As Long, whose organization filed the elephant performance case, stated, “Public interest litigation is the people’s war, and we can never succeed without a broader support. Litigation is not just a legal action, but also a public process in which environmental issues can be exposed, discussed, and debated.” (Interview, Long, NGO staff, October 2024).

Flexible funding

In addition to organizational flexibility, financial self-reliance is perceived as a pivotal factor in securing operational autonomy. As Xiang observed, “public interest depends half on passion and half on funding (一半靠情怀,一半靠算账)” (Interview, Xiang, lawyer, November 2023). Organizations adhering to the conventional model typically rely on three funding sources – social service contracting, project-based grants, and individual giving programs – yet guerrilla activists view these as restrictive due to their inherent limitations. Social service contracting often depends on fostering favorable government relations and demands commitment to party-building initiatives. Project-based grants enable donors to influence the recipient institution’s agenda and priorities, with most donors, whether Chinese or non-Chinese, hesitant to support confrontational endeavors such as litigation.

Similarly, regular giving programs are subject to government scrutiny and suppression. Since 2019, the Chinese government has reportedly instituted an annual review process for monthly giving programs, resulting in the sudden termination of a program led by Qi that had garnered 10,000 donors over 4 years (Interview, Qi, foundation manager, March 2024). Moreover, regular giving programs require substantial effort to establish and sustain the organization’s reputation, which can curtail operational freedom. Consequently, guerrilla activists favor crowdfunding as their primary fundraising approach due to its adaptability and lack of stipulations (Interviews, Meng and Long, NGO staff, September 2023). Unlike regular giving programs, crowdfunding hinges less on the organization’s reputation and more on the project’s topical appeal. For instance, Zhou highlighted a notably effective campaign to prevent companion animal abuse, which raised over 1 million yuan to fund six EPIL lawsuits (Interview, Zhou, NGO staff, March 2024).

Another approach to bolster the financial sustainability of guerrilla lawyering is the strategy of “sustaining litigation through litigation (以讼养讼)” (Interview, Xiang, lawyer, December 2023). Interviewees consider it permissible to leverage litigation to impose financial penalties on polluters and extract contributions from defendants for environmental public interest efforts. In instances where legal success appears unlikely or offers minimal strategic benefit, guerrilla activists have opted to settle, provided defendants cover litigation costs and donate, typically between 100,000 and 200,000 yuan, to environmental charity initiatives (Interview, Xiang, lawyer, December 2023). While this practice has prompted allegations of profiteering from proponents of the conventional model, guerrilla activists reject the premise that financial gain and moral integrity are mutually exclusive. They contend that deriving profit from certain lawsuits is defensible to offset expenses and mitigate losses in other cases, as their primary goal is to sustain public advocacy rather than to amass personal gains (Interview, Nan, lawyer, March 2024).

Despite these adaptable fundraising strategies, the absence of institutional funding suggests that guerrilla lawyering generally encounters greater financial constraints than the conventional model. Concurrently, its experimentalist orientation necessitates an increase in litigation volume. To reconcile these financial challenges with an expanding caseload, guerrilla lawyering exploits ambiguities within legal frameworks to alleviate its financial burden during the litigation process. For example, Chinese civil procedural rules mandate that plaintiffs specify the claim’s value in their submission and pay a case registration fee proportional to that amount.Footnote 9 Given the significant costs of environmental appraisals and case registration fees, guerrilla activists frequently submit an initial nominal claim of 1 yuan, later amending it after a court-initiated investigation determines the actual value at stake. Advocates of the conventional model have voiced strong disapproval of this tactic, deeming it an unethical exploitation of legal loopholes (Interview, Wen, lawyer, June 2023). In contrast, guerrilla activists defend it as a necessary response to biased local courts that persistently disregard the Supreme People’s Court’s directive to waive case registration fees in public interest litigation.

Diffused media strategies

Compared to the conventional model, which approaches media engagements with caution, guerrilla lawyering actively incorporates media strategies into its legal mobilization efforts. Guerrilla activists regard media mobilization as a vital tool for addressing the power imbalances inherent in environmental litigation, where defendant companies often benefit from local political protection. Social media platforms are preferred over traditional media due to their accessibility and dynamic potential. As one interviewee explained, “Traditional media offers only static communication, whereas self-media provides a platform for information aggregation that is both temporally and spatially fluid. It is always in motion” (Interview, Jie, NGO staff, November 2023). This mobility and diffusion are essential for both offensive and defensive purposes in media engagements. For example, in some ongoing trials, the plaintiff organization and its lawyer have refrained from posting comments in their own names to avoid closer scrutiny, while encouraging volunteers to contribute third-party perspectives (Interview, Long, NGO staff, September 2023). In one instance, a volunteer described his observation of perceived bias in court proceedings:

The court rejected the plaintiff lawyer’s request to use the large screen for displaying images and videos of abused animals. Instead, they were required to use a personal computer and present the evidence individually to the judges, people’s assessors, and defendant’s lawyers. Throughout the process, they all persistently averted their gaze and refused to examine the evidence. Other manifestations of discrimination were more subtle. For instance, judges, people’s assessors, and defendant’s lawyers were all supplied with bottled water, while the plaintiff and the plaintiff’s lawyer received none. (Social media post, Brother Nut, performative artist, March 2023).

Given that Chinese censorship typically involves the targeted deletion of specific content and accounts, guerrilla activists operate multiple accounts and frequently switch between different self-media platforms to post and repost content. They employ anonymity and a “strike and move on” tactic to diffuse attention and minimize risk. Feng illustrated this strategy of deception with the following account:

The objective is to catch them off guard, and sometimes, simple solutions are the most effective in averting major crises. In one instance, my anonymous post about an ongoing case garnered significant viewership and drew the attention of the national security department. Several colleagues advised me to leave the country temporarily to avoid repercussions. However, when the officers arrived, I had a junior colleague take responsibility for the post. Since he was young and not on any watchlist, they dismissed it as an accident and issued only a verbal warning (Interview, Feng, journalist, April 2024).

Some guerrilla activists do not perceive state censorship as inherently detrimental to their movement, as it can only remove content but cannot undo the viewership and impact already achieved. Long cited an example of how media mobilization contributed to a recent courtroom victory, in which his organization successfully halted the construction of an RV campsite to protect the habitat of the endangered golden eagle. During the initial hearing, the presiding judge was inclined to dismiss the lawsuit based on the defendant’s claim that no golden eagles inhabited the affected area. In response, activists posted on social media, tagging the city’s mayor and inviting him to a birdwatching tour. Although the post was deleted shortly after reaching 100,000 views, it reportedly prompted the judge to take the case more seriously, allowing additional volunteers to attend the trial and organizing site visits to gather further evidence (Interview, Long, NGO staff, October 2024).

Conclusion

This research unveils the increasing divisions between different forms of environmental cause lawyering amid the rise of authoritarian legality in China. The conventional lawyering model adopts compliance-oriented strategies. They engage in impact litigation and policy consultations to push for incremental environmental reforms. This approach aligns with state-sanctioned channels, securing legitimacy and access to resources, such as funding or policy influence. However, it exposes them to co-optation, as their advocacy often conforms to state priorities, limiting the freedom of agenda-setting and public engagement.

In contrast, guerrilla lawyering adopts an instrumental approach to litigation and adaptive tactics designed to circumvent the limitations imposed by the authoritarian legal system. Informal networks and the utilization of multiple “shell” NGOs provide a discreet infrastructure for sharing resources and maintaining operational flexibility. Experimentalist litigation allows the guerrilla activists to turn the courtroom into a stage for generating information and exploiting legal loopholes, despite the unlikelihood of favorable rulings. Flexible funding tactics, such as crowdfunding and “sustaining litigation through litigation,” ensures financial independence, enabling activists to sustain their efforts without reliance on state resources that might compromise their objectives. Diffused media strategies allow them to mobilize public support for environmental causes while mitigating the risk of state censorship. Collectively, these tactics enable guerrilla lawyers to navigate the suppression/co-optation dilemma, using the law as a contested space for environmental activism.

Beyond the environmental protection sphere, recent legal reforms have created pathways for cause lawyering using guerrilla tactics to pursue other social movement goals. Despite the shrinking space for street-level activism, new women protection laws have bolstered equal work rights, property rights for rural women, and protections against sexual harassment. Although social organizations cannot initiate public interest litigation, they can act as litigation supporters in victim-initiated lawsuits. Here, guerrilla lawyering tactics, such as informal networks to coordinate support and diffused media strategies to amplify cases, enable activists to transform individual grievances into broader advocacy. In the realm of labor rights, some labor organizations have already been involved in providing legal training and advice for individual-led lawsuits (Fu Reference Fu2017), while new laws enhancing substantive protection alongside local experiments permitting social organizations to participate in labor dispute arbitration open additional avenues. Guerrilla lawyering can involve experimental litigation through these processes, testing legal boundaries while relying on flexible funding and informal coordination to sustain efforts.

Guerrilla lawyering emerges as a distinctive form of legal mobilization in authoritarian contexts, where activists strategically engage with a discriminatory legal system to advance their causes while evading state suppression and co-optation. Its theoretical significance lies in its embodiment of a strong situational awareness of asymmetric conflict, mirroring guerrilla warfare tactics by eschewing direct confrontation with the state’s overwhelming power in favor of a protracted struggle that secures small, symbolic victories and gradually undermines state legitimacy. This approach prioritizes dependence on popular support over professionalization, fostering alignment with grassroots communities rather than state-sanctioned legal structures, thereby enhancing its legitimacy and flexibility. Furthermore, guerrilla lawyering demonstrates adaptability and resourcefulness through decentralized operations, experimental litigation tactics, and counter-conduct, enabling activists to subvert the legal system from within while resisting assimilation. Within its institutional context, guerrilla lawyering capitalizes on specific legal openings, such as procedural ambiguities or progressive laws, that persist despite tightening state control, providing critical avenues for resistance. Additionally, bureaucratic fragmentation and regional diversity within the state apparatus generate inconsistencies that activists exploit, leveraging local variations in policy enforcement to sustain their efforts. By elucidating these dynamics, this study enriches our understanding of legal mobilization under authoritarianism and provides a robust framework for examining analogous resistance strategies in other repressive settings.

The suppression/co-optation dilemma, wherein states deploy both overt repression and strategic integration to neutralize dissent, is not unique to China but represents a widespread challenge across nations pursuing authoritarian legality. In recent years, this dynamic has intensified globally as authoritarian regimes implement measures to constrain civil society and consolidate control over legal and activist spheres. A notable trend is the surge in NGO management laws, such as Russia’s 2012 “foreign agents” law and India’s 2020 amendments to the Foreign Contribution Act, which impose stringent registration requirements, financial oversight, and restrictions on foreign funding to limit the autonomy of non-governmental organizations (Bromley et al Reference Bromley, Schofer and Longhofer2020; Chaudhry Reference Chaudhry2022; Van der Vet Reference Van der Vet2018). Similarly, tightened control over the legal profession has become a critical mechanism of authoritarian governance, exemplified by Turkey’s purges of lawyers and judges and Egypt’s judicial restructuring, both of which align legal systems more closely with state interests (Kadıoğlu Reference Kadıoğlu2021; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2014). Beyond these, other measures, such as expanded surveillance technologies in Iran and restrictive public assembly laws in Hungary, further constrict the operational space for independent activism (Akbari and Gabdulhakov Reference Akbari and Gabdulhakov2019; Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018). These global patterns create repressive environments where activists must navigate the dual threats of suppression and co-optation, providing a critical backdrop for understanding the transformation of environmental public interest litigation in China.

The insights derived from guerrilla lawyering may offer a transferable framework for activists operating in other authoritarian contexts where similar dynamics of suppression and co-optation prevail. In nations such as Russia or Turkey, where judicial independence is undermined and dissent is tightly regulated, the tactics of informal networks and diffused media strategies could facilitate coordination and amplify advocacy efforts. Similarly, flexible funding and experimentalist litigation might empower activists to challenge state policies while minimizing direct confrontation. Although these strategies require adaptation to local legal and cultural conditions, their underlying principles of adaptability and strategic resistance provide a robust model for legal mobilization under repressive regimes. This reveals that the expansion of authoritarian legality is fundamentally a double process, characterized by absorption and assimilation on the one hand and extrusion and resistance on the other (Scott Reference Scott2009). Despite the heightened risk of legal co-optation, engagements with authoritarian legality do not inevitably result in acquiescence and subordination to law’s hegemony (Hull Reference Hull2016; Richman Reference Richman2010). To identify more adaptive patterns of counter-hegemonic resistance, it is necessary to shift focus from ordinary individuals to those actively involved in legal campaigns, and to examine not only what people’s perceptions of law but also their actions in response to it (Halliday and Morgan Reference Halliday and Morgan2013; Lovell Reference Lovell2012).

Furthermore, guerrilla lawyering charts new territory in cause lawyering scholarship by demonstrating that legal advocacy can prosper outside the formal, organization‐centered models that have traditionally dominated the field. Seminal studies emphasize how lawyers’ professional identities and institutional affiliations shape strategic litigation, typically focusing on well‐resourced groups operating within established legal opportunity structures (Epp Reference Epp1998; Sarat and Scheingold Reference Sarat and Scheingold2001). In contrast, guerrilla lawyering flourishes through decentralized networks of individual advocates and diversified, dispersed funding. This approach both builds on McCann’s insight that local actors co‐produce legal meaning and departs from his organizational emphasis by foregrounding digitally mediated, low‐visibility tactics (McCann Reference McCann2006). It also refines Vanhala’s analysis of formal opportunity structures by showing how adaptability and informality can substitute for institutional leverage (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2012). Ultimately, guerrilla lawyering deepens our understanding of how cause lawyers and their allies can mobilize under repressive conditions through innovative, networked, and experimental forms of legal activism.

Acknowledgements

I extend my sincere thanks to all interviewees and research assistants whose dedication made this study possible. I am also indebted to the editors of Law and Society Review and to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable suggestions and feedback. Finally, I appreciate the insightful comments of William P. Alford, Alec Stone Sweet, Sida Liu, and Yueduan Wang, as well as those offered by participants at the Harvard Law School Comparative Law Workshop, the Training Initiative for Asian Law & Society Scholars (TRIALS), and the Junior Faculty Workshop at Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong. All errors are my own.

Funding statement

This research was generously supported by the Research Grants of Council of Hong Kong (project number 27613822).

Conflict of interest

There are no competing interests to declare for the author.