Introduction

The electoral breakthrough of radical right populist parties (RRPPs) has become a global phenomenon. While pundits are concerned that nativism and authoritarian attitudes erode democracy (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), a potential connection between political violence and right‐wing populism is one of the most high‐profile debates ramping up in public discourse. Between 1990 and 2019, the Global Terrorism Database reports 772 right‐wing terrorist attacks in Europe (START, 2019).Footnote 1 The literature suggests that attacks against refugees in Germany are more likely to occur in districts where electoral support for Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is high (Jäckle & König, Reference Jäckle and König2017), the effect of radical right political representation on right‐wing violence is conditional on regional and economic heterogeneity (Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2018), there is a link between politicians’ hate speech and hate crime (Müller & Schwartz, Reference Müller and Schwartz2020) and there is a mediation effect of radical right representation on the right‐wing terrorism and refugee inflow nexus (Matsunaga, Reference Matsunaga2023). Public scepticism towards right‐wing populism peaked after the attack on the US Capitol in January 2021. The attack raised the concern that violence‐justification attitudes may be widely shared among right‐wing populists beyond the small number of extremists. Prior research has demonstrated a link between individual‐level populist attitudes and support for political violence (Armaly & Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022; Levi et al., Reference Levi, Sendroiu and Hagan2020; Piazza, Reference Piazza2023). Although they offer important insights, which ideological component of populism relates to violence‐justification attitudes and whether the relationship between populist ideologies and justification of violence exists beyond single‐country studies remain untested.

This research addresses the gap by examining different political ideologies. I assume that right‐wing populists, defined here as RRPP voters, are more likely to justify political violence than those who support different ideologies such as left‐wing populism and centrist political ideologies. RRPPs tend to create inter‐group conflicts (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Haüsermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021) and condone right‐wing violence. However, evidence of a direct link between RRPPs and right‐wing violence is scarce (Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023). Empirical studies in Germany and the United States illustrate that right‐wing violence wins the hearts and minds of in‐group individuals (Armaly & Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022; Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2023) and increases support for radical right parties among the most right‐leaning individuals (Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023; Ohlemacher, Reference Ohlemacher1994). Conversely, RLPPs (radical left populist parties) adopt a universalist rhetoric that does not exclude ethnic out‐groups. RLPPs generally do not support violent class conflicts or left‐wing terrorism (Przeworski & Wallerstein, Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982). Furthermore, while society accepts non‐violent left‐wing protests, right‐wing ideology is socially stigmatised (Hager et al., Reference Hager, Hensel, Hermle and Roth2022). The asymmetry of public perceptions can create the attitudinal difference in justifying political violence.

This research note makes two main contributions to the literature. First, it provides a generalised account of which ideological components of populism connect with violence‐justification attitudes in electorate democracies. Second, by revising the economic deprivation theory, I investigate the relationship between partisan attitudes towards violence and deprivation. Drawing on the European Values Survey (EVS) Wave 5 (EVS/WVS, 2022), I examined 18 Eastern and Western European countries that have accepted immigrants and experienced right‐wing populism surges (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Norway, Romania, Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, Sweden and Switzerland) between 2017 and 2019 (N = 15,759). Cross‐national analyses suggest that right‐wing populists are most likely to approve of political violence. However, a positive correlation is also observed regarding left‐wing populist individuals approving political violence, although the effect is comparatively smaller. By contrast, centre‐right voters and non‐voters have negative and statistically significant effects in justifying political violence. Subsequent analyses establish that right‐wing populists’ attitudes are conditional on gender, city residence and immigration background. Educational attainment, economic grievances and age have null or weak effects. Contrastingly, left‐wing populists’ attitudes towards violence are influenced by educational attainment and age. These attributes are unique compared to other voters. Furthermore, anti‐immigration attitudes and nativism do not affect right‐wing populists’ attitudes justifying violence. Therefore, no evidence that right‐wing populists holding such perceptions are more radical than others with similar perceptions exists. These findings from the cross‐national analysis help construct a more generalised argument on the relationship between populist ideologies and political violence. Furthermore, this study also contributes to the discussion on the nature and consequences of populism in electorate democracies.

Political violence and right‐wing populism

To identify causal determinants of radicalisation, prior studies have focused on inequality (Falk et al., Reference Falk, Kuhn and Zweimüller2011), psychological shock due to high‐profile violent incidents (Frey, Reference Frey2020), the liberal government (Koch & Cranmer, Reference Koch and Cranmer2007), exposure to online campaigns (Mitts et al., Reference Mitts, Phillips and Walter2022), exposure to violence (Braun & Koopmans, Reference Braun and Koopmans2010; Lyall et al., Reference Lyall, Blair and Imai2013), and other socioeconomic conditions. Political ideology is equally important to individual radicalisation. The level of violence employed by extremists is conditional on terrorist attacks from different ideological backgrounds (Jasko et al., Reference Jasko, LaFree, Piazza and Becker2022).

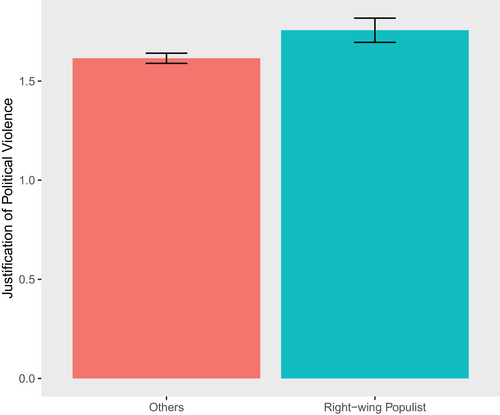

Attitudes towards violence justification can be stronger among right‐wing populists. Based on data from 18 countries in EVS Wave 5, Figure 1 compares the overall mean of attitudes towards political violence between right‐wing populists and others (including non‐voters) with 95 percent confidence intervals. On average, right‐wing populists tend to justify political violence 0.14 points higher than other voters. In contrast, centre‐right individuals have a comparatively lower tendency to justify political violence than other individuals.Footnote 2 Figure B1 and Figure B2 in the Supporting Information further depict the attitudinal differences at each country. In most countries, RRPP voters are more likely to justify political violence, but heterogeneity exists between countries where RRPPs are opposition parties and those where RRPPs hold government.

Figure 1. Partisan difference in justification of political violence.

I discuss several mechanisms that explain how right‐wing populist ideologies relate to individual attitudes towards political violence. The first mechanism under which right‐wing populists fall into radicalisation is exclusive nationalism, which distinguishes them from other political ideologies (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). The nativist rhetoric that distinguishes ethnic natives (us) from others (them) allows the scapegoating of minorities and immigrants. While extremists dominate a small proportion of right‐wing populists, grievances are publicly shared. When problems relating to intergroup competition capture extensive public attention, the level of tolerance for violence tends to be higher; thus, individuals are more likely to justify political violence if they share ethnic, ideological or societal similarities with the perpetrators (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2023; Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023).

Second, right‐wing populist leaders send oblivious cues to villainise societal out‐group members and approve of political violence to achieve their political goals (Merkl, Reference Merkl1995). In 2021, Eric Zemmour, a former candidate for the 2022 French Presidential Election, was tried for his remark claiming that unaccompanied child migrants are ‘thieves, killers and rapists’.Footnote 3 Jean‐Marie Le Pen of the National Front in France condemned the Norweigian government in the face of the 2011 Oslo and Utøya attack (Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023). Similarly, AfD Bundestag members did not condemn the perpetrator who assassinated Walter Lübcke, a pro‐immigrant politician in Hesse, Germany. Although radical right populist parties are not actively involved in violence owing to the accompanying risk to their parliamentary seats (Matsunaga, Reference Matsunaga2023), the inflammatory attitudes of some elites may convey mixed signals to voters that right‐wing populist parties justify political violence (Müller & Schwartz, Reference Müller and Schwartz2020). Therefore, supporters consider violent strategies plausible to achieve the political goals such as cultural protectionism (Sabucedo et al., Reference Sabucedo, Blanco and De la Corte2003). In this context, radical right populist party leaders perpetuate that they at least condone or lend ideological support for the forcible elimination of ethnic or societal out‐group members.

Third, the stigmatisation of right‐wing populism causes political exclusion, resulting in the growing frustration of right‐wing populists. Right‐wing populist ideology is often punished by political competitors, as demonstrated by the banning of Austrian FPÖ from the European Parliament in 1999 (Freeman, Reference Freeman2002; Schain, Reference Schain2006). Similarly, Thomas Kemmerich of the FDP, elected Minister President of Thüringen in 2020, was forced to resign as he was endorsed by AfD.Footnote 4 A survey conducted shortly after the failed Capitol attack in the United States indicated that 40 percent of Republicans justified political violence, endorsing the argument that exclusion (from political power) may relate to radicalisation.Footnote 5 The anecdotal evidence suggests that in response to moral concerns by political competitors and widespread public backlash, some right‐wing populists extricate themselves from radicalismFootnote 6, while others are excluded from political scenes. Under‐representation prevents right‐wing populist politicians from bypassing constituencies and policy making. Betrayed expectations reduce trust in the democratic system and radicalises a portion of right‐wing populists rather than following democratic procedures.

To summarise the argument, I formulate the first hypothesis as follows:

H 1: Right‐wing populists are more likely to justify political violence than other partisans.

Contrary to right‐wing populism, left‐wing populism defines ‘people’ in civil terms and not in ethnic terms (Meijers & Van Der Velden, Reference Meijers and Van Der Velden2023), which implies that their in‐group concept is based on universalist/socialist languages that address labourers, as opposed to corrupted elites. However, as Przeworski and Wallerstein (Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982) notes, class conflict in democracies does not bring substantive confrontation between the elites and the working class, as their representation is secured through the political system. Indeed, despite ideological homophily, RLPPs and their voters distance themselves from violent Marxist revolutions and value the democratic systems. Hence, I expect that left‐wing populist voters do not have substantial incentives to justify political violence to outbid political enemies since their political representation is secured compared to right‐wing populists.

Empirical strategy

This study utilised the EVS Wave 5 (EVS/WVS, 2022) and selected 18 European democracies with different political systems and economic development. Although I examined all countries included in both the EVS/WVS Wave 5 and PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), countries not covered by PopuList data (e.g., Asia Pacific countries and North Americas, Greece and Belgium), without pre‐treatment variable data (e.g., the United Kingdom and the Netherlands) and without established RRPPs before 2017 (e.g., Portugal, Spain) were excluded. The EVS benefits us in several ways. First, it provides a question to measure attitudes towards violence, which other major surveys, such as ESS and Eurobarometer, do not have. Second, it allows for a cross‐national analysis. Finally, the fieldwork period (between 11 September 2017 and 30 January 2019) covers a period corresponding to major RRPPs’ electoral breakthroughs.

After excluding observations without answers, the dataset contained 15,759 respondents. They were categorised based on party preference: right‐wing populist party supporters (N = 2,945), left‐wing populist party supporters (N = 1,234), centre‐right supporters (N = 5,616), centre‐left party supporters (N = 3,982), green and environmental party supporters (N = 1,052), non‐voters (N = 663) and other small party and centrist party supporters (N = 267). The party identification of right‐wing and left‐wing populists was based on the PopuList Project (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), and other parties’ ideologies were retrieved from the Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR) (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018).Footnote 7

I created a simple multilevel model that includes a random intercept, random slope and fixed effects. Considering heterogeneity and different political systems (e.g. populist regimes, electoral systems, economic development and the level of democracy) among the 18 countries,Footnote 8 a multilevel analysis seems appropriate.

where Yi,j is the outcome variable that evaluates individual attitudes towards violence. A corresponding question (E290) measures respondents’ self‐identification of political violence resistance on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 denotes ‘Never justifiable’ and 10 denotes ‘Always justifiable’. The model consisted of two levels. γ 00 + γ 10Xij is a fixed part, where X denotes the independent variable, ‘Right‐wing populist’. I exploited the respondents’ party affinity. A corresponding survey question (

![]() $ {\rm{E181}}\_{\rm{EVS5}}$) asks for the respondents’ partisanship as follows: ‘Which political party appeals to you most?’ with given a set of choices for party names. I created a dichotomous variable, ‘Right‐wing populist’ equal to 1 if a respondent chose right‐wing populist parties or far‐right parties, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, I prepared dichotomous variables for other party families: centre‐right, centre‐left, left‐wing populist, green and non‐voters. μ 0j + μ 1j + εi,j is a random part where μ is independent from an error term ε. I added several pre‐treatment variables to the model, including respondents’ age, gender, immigration background, education, income, size of the residential community and unemployment status. Since terrorist attacks and the electoral presence of RRPPs can affect the attitudes towards political violence, I added the logged count of domestic terrorist attacks that occurred in the previous 2 years of the survey fieldwork (2016 and 2017) and the logged vote share of RRPPs in previous general elections. Data on terrorist attacks are retrieved from START (2019), and election data from Comparative Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018). Additionally, I added the population weight to the formula. I provide the descriptive statistics which appear in the Supporting Information Appendix (Table A1) and summarise the corresponding EVS questions in Supporting Information Table A20. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2.

$ {\rm{E181}}\_{\rm{EVS5}}$) asks for the respondents’ partisanship as follows: ‘Which political party appeals to you most?’ with given a set of choices for party names. I created a dichotomous variable, ‘Right‐wing populist’ equal to 1 if a respondent chose right‐wing populist parties or far‐right parties, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, I prepared dichotomous variables for other party families: centre‐right, centre‐left, left‐wing populist, green and non‐voters. μ 0j + μ 1j + εi,j is a random part where μ is independent from an error term ε. I added several pre‐treatment variables to the model, including respondents’ age, gender, immigration background, education, income, size of the residential community and unemployment status. Since terrorist attacks and the electoral presence of RRPPs can affect the attitudes towards political violence, I added the logged count of domestic terrorist attacks that occurred in the previous 2 years of the survey fieldwork (2016 and 2017) and the logged vote share of RRPPs in previous general elections. Data on terrorist attacks are retrieved from START (2019), and election data from Comparative Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018). Additionally, I added the population weight to the formula. I provide the descriptive statistics which appear in the Supporting Information Appendix (Table A1) and summarise the corresponding EVS questions in Supporting Information Table A20. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2.

Results

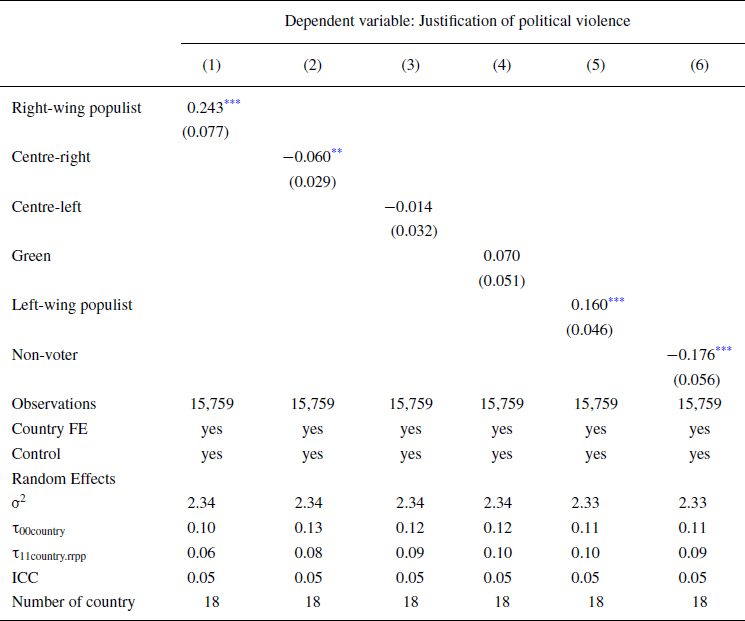

I start with a null model to check the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which determines the overall variation to be attributed to the variance between the countries. In the null model (with all covariates), the ICC is 0.05, and the intercept is 1.86 (p < 0.01). Next, Table 1 reports the results of the multilevel analyses. In line with the expectation, the estimate of right‐wing populist voters is 0.243 (p < 0.01). The estimates of centre‐right voters and non‐voters are −0.060 (p < 0.05) and −0.176 (p < 0.01). Voters of the latter two groups do not justify political violence in pursuit of their political goals. Centre‐left and green ideologies have null effects. However, the average marginal effect of left‐wing populists is 0.160 (p < 0.01); while the effect is smaller than that of right‐wing populists, left‐wing populists also tend to justify political violence. To facilitate the interpretation of b‐values, I mathematically transformed all Likert variables (e.g. 4‐point scale and 9‐point scale) to a single scale ranging from 0 to 1. For example, a Likert variable with a 4‐point scale was converted to 0, 0.33, 0.67, and 1. The results are presented in Table A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix. In the multivariate multilevel analysis presented in Table A5, the estimate of the right‐wing populist is 0.027 (p < 0.01), centre‐right is −0.007 (p < 0.05), centre‐left is 0.002, Green is 0.008, left‐wing populist is 0.018 (p < 0.01) and non‐voter is −0.019 (p < 0.01). The results suggest that right‐wing populists and left‐wing populists are 2.7 and 1.8 percent more likely to justify political violence than other voters, respectively. Similarly, centre‐right voters and non‐voters are 0.7 and 1.9 percent less likely to justify political violence, respectively.Footnote 9

Table 1. Multivariate multilevel analysis

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

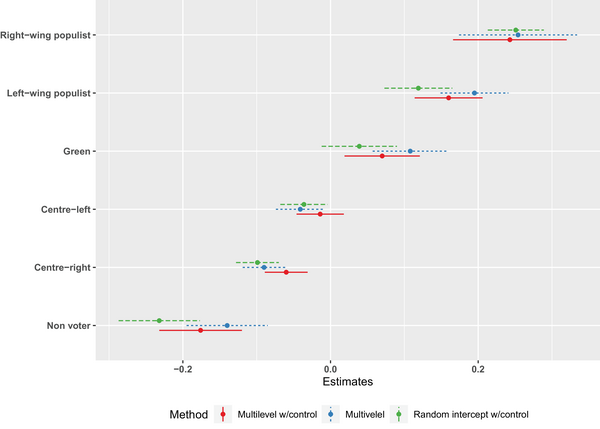

Turning to the main results, ICCs in Table 1 are 0.05; if an ICC is below 0.05, it suggests that the variability within the clusters should be high, but the variability between clusters is relatively low, although it is still meaningful to explore. Thus, as Stegmueller (Reference Stegmueller2013) recommends, I additionally tested a simple linear model with a random intercept. The results are reported in Table A6 in the Supporting Information Appendix. The complete results show similar directions with statistical significance. The estimates of right‐wing populists, left‐wing populists, centre‐right, and non‐voters are 0.251 (p < 0.01), 0.119 (p < 0.05), −0.099 (p < 0.01) and −0.232 (p < 0.01), respectively. The estimates of centre‐left and green respondents are positive, but not statistically significant. The ideological effect on the justification of political violence in three different models is illustrated in Figure 2: bivariate multilevel models, multilevel models with controls and ordinary least squares (OLS) with random intercept. The results are all consistent.

Figure 2. The partisan effects of the justification of political violence.

Overall, these results support the main hypothesis. Right‐wing populists have stronger violence‐justification attitudes than other partisans and non‐voters. Despite its ideological homophily, centre‐right individuals have negative attitudes on violence justification. Mainstream individuals exhibit either negative or null effects. Contrary to expectation, left‐wing populists also tend to justify political violence, although the effect size is smaller than that of right‐wing populists. The complete results are reported in Tables A2–A7 in the Supporting Information Appendix. Note that the effect varies across the countries. According to Figure B4 in the Supporting Information Appendix, the violence‐justification attitudes of right‐wing populists are mostly driven by specific countries where right‐wing populist ideologies are not (yet) normalised. Right‐wing populists from countries where RRPPs hold governments (e.g., Hungary and Poland) or join coalition governments, are less radical than others with different ideologies.

Alternative explanation: Deprivation

Deprivation might be another source of radicalisation. There are mixed findings on whether individuals exposed to deprivation have violence‐prone attitudes. Abadie (Reference Abadie2006) suggests that inequality in political participation affects the incidence of terrorism. Similarly, some studies propose that unemployment increases the frequency of right‐wing political violence in Germany (Falk et al., Reference Falk, Kuhn and Zweimüller2011), individuals with lower educational attainment are most likely to volunteer for terrorist groups (Bueno de Mesquita, Reference Bueno de Mesquita2005), and minority grievances are the driving factor of political violence (Ghatak et al., Reference Ghatak, Gold and Prins2017). However, Piazza (Reference Piazza2017) finds no supporting evidence for an argument that economic grievances could lead to domestic right‐wing terrorist attacks in the United States. While these studies focus on the link between extremists and deprivation, it is possible that deprived non‐extremist individuals increase their violence‐justification attitudes. Accordingly, I formulate the following hypothesis:

H 2: Deprived right‐wing populists are more likely to justify political violence.

Figures B5 and B6 in the Supporting Information Appendix compare the mean attitudes towards political violence between the deprived and non‐deprived populations of right‐wing populists and non‐right‐wing populists, respectively. These figures imply that some deprived right‐wing populists (i.e., unemployed, males, immigration status) are more likely to justify violence. Studies indicate that higher support for right‐wing populist parties depends on individuals’ socioeconomic circumstances and perceptions. For instance, individuals from financially unstable households give more support to right‐wing populist parties (Abou‐Chadi & Kurer, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Kurer2021), and males generally give higher support (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2023; Bolet, Reference Bolet2023; Ralph‐Morrow, Reference Ralph‐Morrow2022). Similarly, anti‐immigrant sentiments (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2023), xenophobia and economic concerns facilitate right‐wing populism. Furthermore, right‐wing populist parties thrive in urban areas (de Decker et al., Reference de Decker, Kesteloot, de Maesschalck and Vranken2005).Footnote 10 Although support for right‐wing populism does not automatically relates to justification of political violence, right‐wing populist voters with significant grievances or deprivation may have higher violence‐justification attitudes.

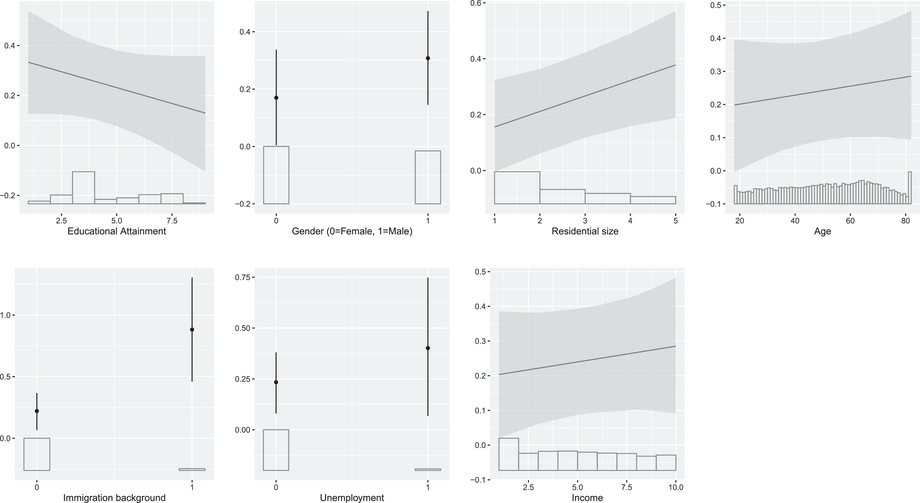

I build models with interaction terms between right‐wing populist ideology and seven socioeconomic factors that could lead to deprivation. Figure 3 presents an overview of these results.Footnote 11 In the top row, the second figure from the left indicates that male right‐wing populists have a higher approval rate of political violence. The estimate of the interaction between right‐wing populist party support and the gender dummy is 0.139 (p < 0.05). The interaction term of the residential community size is 0.055 (p < 0.05) and 0.658 with an immigration background (p < 0.01). These interaction terms indicate that right‐wing populists who identify as male, live in urban cities, or have a history of immigration are more likely to justify political violence. Other factors, such as educational attainment, age, unemployment and income, have null effects.

Figure 3. Interaction between right‐wing populism and socioeconomic factors.

Next, I compare the results in Figure 3 to other voters. Tables A9–A13 in the Supporting Information Appendix present the results.Footnote 12 Although centre‐left and non‐voters attitudes towards violence do not depend on socioeconomic factors, centre‐right voters from small residential communities and native‐born green voters are more likely to justify political violence. Furthermore, left‐wing populists with higher educational attainment or younger age have a similar tendency.

The findings clarify that right‐wing populists have a unique source of marginalisation that justifies political violence. Rather than age, education or economic grievances, right‐wing populists’ attitudes towards political violence are conditional on urban residence and gender. Moreover, despite the exclusive nationalism of right‐wing populist ideology, such voters with immigration backgrounds are more likely to justify political violence. This finding may be related to ‘within’ resource competition inside the immigrant community.

Social perceptions

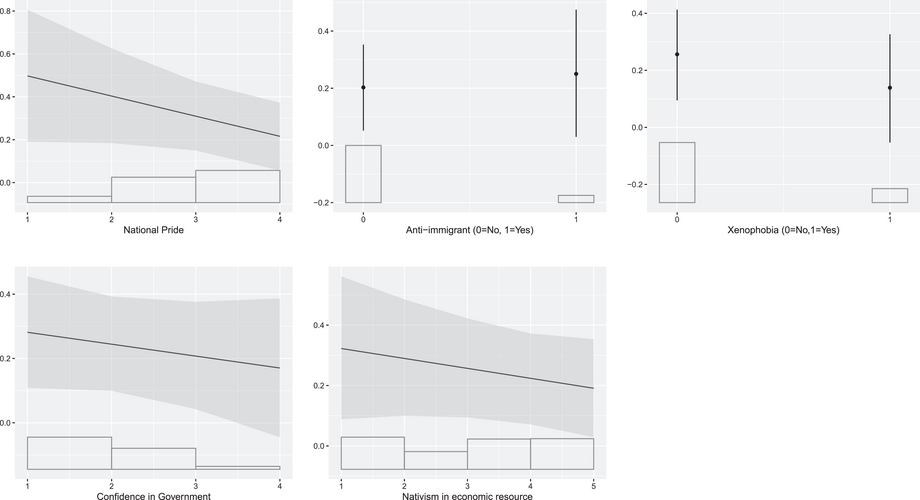

Studies have documented that anti‐immigrant attitudes, nationalism, government distrust, authoritarianism and xenophobia are related to electoral support for right‐wing populist parties (Donovan, Reference Donovan2019; Evans & Mellon, Reference Evans and Mellon2019; Golder, Reference Golder2003; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004, Reference Mudde2007; Williams, Reference Williams2006). This section examines whether these perceptions are related to justification for political violence. I employed additional interaction terms of attitudes towards political violence and (i) national prideFootnote 13, (ii) anti‐immigrant attitudesFootnote 14, (iii) xenophobiaFootnote 15, (iv) confidence in the government and (v) nativism in economic resource competitionFootnote 16.

Results are reported in Table A14 in the Supporting Information Appendix and the effects of the interaction terms are illustrated in Figure 4. While the figure visualises how the social perceptions of right‐wing populists interact with violence‐justification attitudes, none of the interaction terms are statistically significant at the 95 percent significance level. Furthermore, the violence‐justification attitudes of non‐voters and green voters are not affected by social perceptions. However, left‐wing populists with lower levels of national pride, centre‐right voters without anti‐immigrant sentiments and centre‐left voters with higher levels of national pride tend to justify political violence.

Figure 4. Interaction between right‐wing populism & perception.

The findings extend the research by suggesting that the nativist and anti‐immigration sentiments of right‐wing populist voters do not lead to the affirmation of political violence. The analytical results and figures of the interaction between ideologies and social perceptions are provided in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Discussion

Despite an increasing demand to examine the relationship between populism and individual attitudes towards political violence, the components of populist ideology that drive such attitudes have been understudied. Drawing on the EVS, this research note provides evidence that right‐wing populists, in general, are more likely to justify political violence than centrists, green voters or non‐voters, although heterogeneity exists across countries. Left‐wing populists also justify political violence. Furthermore, the attitudes of right‐wing populists are conditional on deprivation factors such as gender, residential community size and immigration background. Left‐wing populists’ violence‐justification attitudes depend on their age and educational attainment. Social perceptions, such as anti‐immigration sentiments and nativism, are not driving factors. These findings are applicable to countries where right‐wing populism is not mainstream. Comparative analyses ensure the external validity and provide generalised implications beyond single‐country studies.

This note contributes to academic discussions on political violence and populism. One strand of research has established that right‐wing populist representation is systematically related to political violence that targets immigrants, refugees and ethnic/sexual minorities (Jäckle & König, Reference Jäckle and König2017; Matsunaga, Reference Matsunaga2023; Müller & Schwartz, Reference Müller and Schwartz2020; Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2018). Another strand of research focuses on the reverse causality and studies the effect of political violence on public support for right‐wing populist parties and ideologies (Armaly & Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022; Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2023; Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023). I extend the discussion by comparing the attitudes towards violence among right‐wing populists, left‐wing populists, mainstream voters and other partisans in 18 European countries, and document that populists tend to approve of political violence even though they are not extremists. Cross‐national findings provide a generalised argument on whether and why populism is associated with violence‐justification attitudes. As terrorist attacks, hate crimes and violent protests are often situational acts by lone‐wolf perpetrators with no previous criminal record, understanding the mechanism of public radicalisation has become increasingly relevant.

This research has several limitations. First, we need more evidence to identify whether populists are inherently equipped with violence‐justification attitudes or whether (radical) populist parties, politicians and the media influence them. Second, although this study expands the scope of observation from a single country to multiple European democracies, observing different regions enriches this line of research.

Nevertheless, the findings have serious policy implications for the nature of populism and causes of political radicalisation. Right‐wing populist ideology is considered violence prone, as the election trend indicates that supporters remain with such parties even after a series of right‐wing terrorist attacks (Krause & Matsunaga, Reference Krause and Matsunaga2023). This note is embedded in this line of burgeoning research and reveals that left‐wing populists also hold similar attitudes. Hence, populist ideologies, by and large, are more likely to be associated with the justification of political violence than mainstream left and right ideologies. These findings suggest a way to resist the radicalisation of non‐extremist individuals with both populist right‐wing and left‐wing ideologies.

Acknowledgements

I am especially thankful to Yuliy Sannikov, Joost van Spanje, editors and four anonymous reviewers of EJPR for helpful comments and suggestions.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: