Introduction

June Boyce-Tillman completed her PhD in 1987 (Tillman, Reference TILLMAN1987) at the London Institute of Education, supervised by Keith Swanwick. Written in two volumes, her thesis considers definitions of creative processes and the possibility of their subdivision into stages. Following these discussions, the relationship with children’s own creative processes through musical composing is explored in her doctoral research project. A third element in the thesis is a cassette tape of recordings taken from the musical compositions of child participants, which Boyce-Tillman analyses in her discussions. Boyce-Tillman’s PhD includes 237 notated examples taken from children’s classroom work and her spiral of musical development, which she regarded as the beginning of a musical ‘map’ through which musical development could be charted. Her aspirations were that:

The map will encourage people to set out on their own musical voyages of discovery, helping them into possible future routes. For we all need to feel both that we know where we are and yet that there is still somewhere to go and a treasure that may be found (1987, p. 119).

Boyce-Tillman became fascinated with musical development through observations of her own children and her experiences of teaching in primary and secondary education contexts (Tillman, Reference TILLMAN1976). Through musical facilitation in preschool work, she also began to identify possible strands of musical development and, in time; this led to work with Keith Swanwick, who was then a professor at the Institute of Education. This work gradually developed into PhD study and although Boyce-Tillman’s thesis is less well known, the article which she and Swanwick published together during the final stages of her doctoral work (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986) has become widely influential in music education and forms the central core of this current special edition of the BJME.

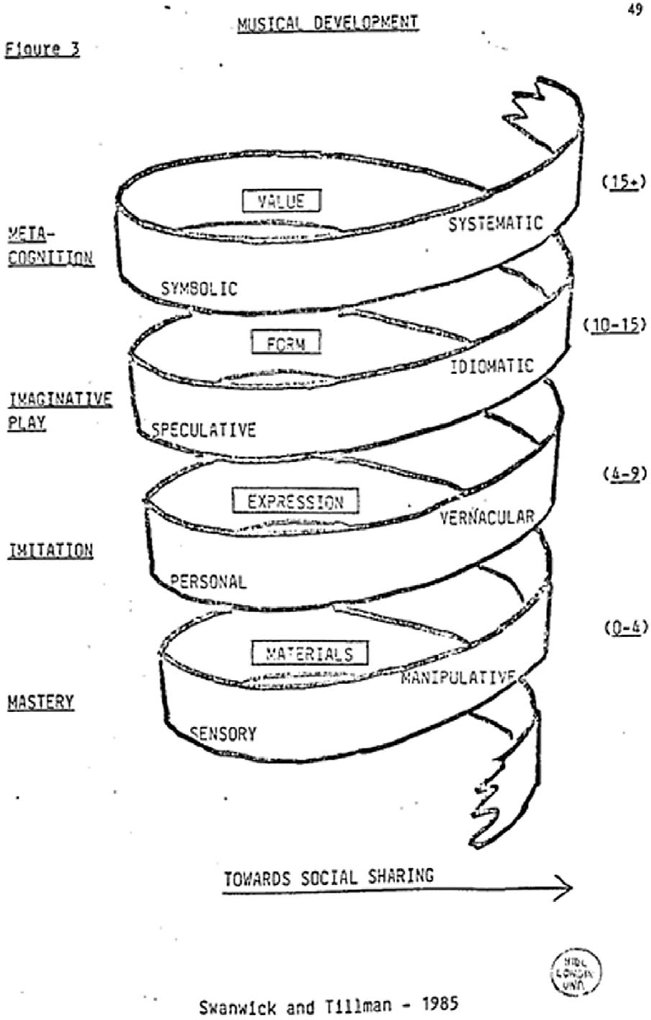

The Sequence of Musical Development: A Study of Children’s Composition (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986) sets out the premise that childhood development can, to some extent, be observed and that this also applies to the musical domain. The article’s theoretical basis builds from proposed connectivities between play and artistic activity and develops Piaget’s (Reference PIAGET1951) notions of mastery into a handling of musical instruments (manipulative control) which ultimately find their voice in composition. This leads to a discussion of sound Materials,Footnote 1 imitation, expressive character and imagination, which are represented as a triangle conceptualising three elements of music as play. In this model, mastery is connected with control of sound materials, imitation with expressive character (accommodation) and imaginative play with structural relationships (assimilation). Analysis of the 745 compositions from 48 children aged between 3 and 11, over 4 years which comprised the body of the study, is then presented and it is from this that the model of musical development emerges (see Figure 1). The paper concludes with a set of implications for music teaching, which include general curriculum planning, the musical development of individual children and the role of the teacher.

Figure 1. Spiral of musical development taken from Tillman’s doctoral thesis (1987, p. 50).

Reception to Boyce-Tillman’s research was varied, and it sparked multiple debates on the nature of musical interactions in children. Examples of these include the nature of playing by ear, which has been described as requiring the assimilation of sounds (Toplis, 1990); the significance of age-related developmental stages, where playing the violin in groups was found to replicate the findings of Swanwick and Tillman (Verney, Reference VERNEY1991); and creativity stages, which drew upon the patterns and organisations of sound presented in Swanwick and Tillman’s original paper (Levi, Reference LEVI1991). There were also critiques of the validity of Swanwick and Tillman’s approach. Lamont (Reference LAMONT1995) suggested that it lacked ‘predictive power’ (1995, p.10), indicating a retrospective rather than a representative model. It has also been considered to be culturally specific (Lehmann, Sloboda & Woody, Reference LEHMANN, SLOBODA and WOODY2007), thus limiting its value across differing contexts. There have been further suggestions that other forms of musical interface (such as music technology) may invalidate Boyce-Tillman’s account of ‘the development of musical ability’ (Cain, Reference CAIN2004, p. 218).

Despite such critiques, Boyce-Tillman’s work has continued to be influential. More recently, it has been part of discourse concerning novice composing from which Fautley developed his model for group composing in the secondary school (2005). Fautley’s model was later analysed by Hopkins (Reference HOPKINS2018) and this later article in turn references the Swanwick and Tillman model of musical development. The Swanwick/Tillman spiral has also been included in the discussion of the place of play in the development of expressive vocalising by infants (Aleksey, Reference ALEKSEY2020), and as a linkage between metacognition in adolescence to musical experience and the selection of career electives (Myung-Jin, Reference MYUNG-JIN2020). The work of Swanwick and Tillman has therefore continued to be widely cited and impactful on research formations almost 35 years after it was first published. This article seeks to explore the origins of Boyce-Tillman’s research project, providing additional contextual discussion which has, until now, been absent in this influential work.

What follows in this article is an interview which was conducted with June Boyce-Tillman as part of research into music curriculum design at Key Stage 3 (ages 11–14 in the lower English secondary school), which took place in the summer of 2017 (Anderson, Reference ANDERSON2019). The interview enabled further enquiry and interrogation of the rationales lying behind the spiral, enabling understanding of its origins in greater depth. The conversation which this paper presents is not a verbatim account, but one in which some of the strands of the spiral of musical development are unwoven, just a little, and their texture examined. The aspiration of this article is to facilitate further discussion of musical development in the context of music education, where it is anticipated that the spiral of musical development will continue to have international influence, just as it has since it was first published.

The material presented in the article has been arranged into sections which bricolage some of the central concepts of the Swanwick and Tillman (Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986) spiral. Discussions begin with the vernacular and how this connects to musical development. This prepares the foundation for the reminder of the article, as it was Boyce-Tillman’s central fascination with the vernacular and its function as a ‘funnel’ which inspired her to engage in her doctoral work. A consideration of musical literacy then follows from the vernacular, considering how vernacular modalities connect with understandings of the substance of what it means to be literate in music. The paper then moves to its central section, with an extensive discussion of Values and why these can be neglected in music educational discourse, while for Boyce-Tillman they are foundational to her musical philosophy. In considering what such philosophical perspectives might mean for classroom practices, a discussion of music curriculum design and sequencing then follows, which proposes the classroom practitioner as both music teacher and music broker. The paper concludes with Boyce-Tillman’s responses to the critical reception of the spiral of musical development and explores the implications for continued musical development debate and scholarship.

What are the origins of the vernacular?

In her later work, Boyce-Tillman (Reference BOYCE-TILLMAN2006) described how musical enculturation begins with Materials, which develop through Expression into vernacular realisations of musical idioms. In her first (jointly authored) paper which addressed this area (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986), she articulated the vernacular as the ‘common language of music’ (1986, p. 316), describing how imitation and expression combine to create a new modality. Before long, the vernacular and its substance was included in musical research analysis by others in a variety of contexts, including stage theory (Koopman, Reference KOOPMAN1995) and tradition in children’s games (Prim, Reference PRIM1995), for example. During the interview on which this article draws, Boyce-Tillman describes her early origins of the concept of ‘vernacular’:

Anthony: Your early interests in childhood development and the place of music within it, led to a huge longitudinal study. 745 recordings over 4 years from 48 children…was there anything in particular that stood out for you?

June: The move to the vernacular, is the thing that fascinates me, and the way that more conventional music teaching, slots into that. Children do so want to learn an instrument and once they are, they need to learn the conventions of that instrument. After learning these they become more willing to invent new material - to compose. But they will have gone through a time when they didn’t particularly want to innovate, they just wanted to learn the conventions of the culture.

There was the moment in the last exercise they had to do as part of my research: it was to make up or sing a song of some kind. When we got to that bit and one girl sang, [sings] ‘London’s burning, London’s burning’, and I think I probably said, ‘No, not one of those, one of yours’, and she said, ‘No, I don’t want to sing them, I want to sing London’s Burning.’ And I contemplated this, because in early thinking about creativity in the classroom, children were often kept in what I call a ‘Peter Pan’ state - making up their own songs. This can be attractive to teachers, but actually, the children themselves wanted to join the culture, so they did want to sing vernacular songs such as ‘London’s Burning’. There were some strange things going on at that time in the classroom – people were trying to do variations on ‘London’s Burning’ when the person could not even play or sing ‘London’s Burning’! [Laughs].

There were all sorts of articles, saying: ‘Isn’t it remarkable? You know, children in the classroom can produce pieces like Stockhausen!’ Now, of course, that was true, but they were profoundly different from Stockhausen, because they could do nothing else. Whereas Stockhausen was choosing to do that, the children were not! [Chuckles] They had to do what Stockhausen had done and enter the vernacular, which I describe as a funnel. You have to go through a funnel, just like you do in language. Sounds babies are encouraged to make in English are different from the sounds babies are encouraged to make in Chinese – different languages use different sounds.

So the vernacular always narrows the possibility, whether it’s language or whether it’s music. So you’ve got a continuum of pitch and western music divides it up one way and if you live somewhere else you might divide it up in a different way. Why we do it the way we do is still the bit that interests me.

What is musical literacy?

Orate traditions and their positionality in musical literacy, and how such literacy is understood, were also prominent features of Boyce-Tillman’s spiral formations. In her thesis (Tillman, Reference TILLMAN1987), she includes transcribed versions of the extracts of children’s musical creations which emerged from her sessions with them. As stated earlier, her thesis included a cassette recording of these extracts, and a smaller selection of these also accompanied the publication of the paper in which she collaborated with Swanwick as her PhD supervisor, during her doctoral studies (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986). The inclusion of recordings alongside an academic paper was less than commonplace at this time, when recordings did not exist as convenient computer audio files. The place of transcription, its validity and how it stands alongside the recordings themselves are therefore significant in Boyce-Tillman’s published work. In the context of understanding how children’s music is both realised and interpreted in notation traditions, Boyce-Tillman made the following remarks during our research discussion:

Anthony: What was the place of transcription in your research, and did that impact things, do you think?

June: Of course. One of the things that fascinates me a great deal is the interface between the orate and the literate. There are orate African drumming traditions and there are our own literate classical traditions. Of course, I was exploring that then – when does the orate become potentially literate and I’m now extremely critical of ethnomusicology – I think it’s gone down a blind alley – it shouldn’t have turned orate traditions into literate traditions, because the orate traditions are not the same and you skew them by writing them down.

You often have to skew them into the conventions of your notation, even if you know that it’s not the conventions that they are using. You only have to see that in poor old Bartok trying to collect all the Bulgarian and Romanian folk music with marginalia that say, ‘just a little bit higher,’ or ‘a little bit lower,’ and you can see that our notation system causes difficulties. In a sense it’s at the vernacular where literacy becomes possible within the conventions of the chosen culture if it is a literate one. Before that it’s not possible.

Anthony: How do you understand literacy?

June: Well, you can transcribe, relatively easily, when the child can repeat their musical utterance. But before that point, it is difficult or impossible to do. If they have waved a shaker and they’ve gone all like this [waves hands in air as if waving shaker] and you say ‘Can you do that again?’ and they can’t – there is no vernacular. Later they’ll go [claps strong rhythmic pattern] And you might say, ‘Can you do it again?’ and they’ll do exactly the same again. It’s formulated, they can do it the same, then you can start to write it down. This makes transcription possible and this is how I regard the beginnings of musical literacy.

But if you asked little children to make a group piece the child leader might give out the instruments and tell each person when to start playing. When I’d say, ‘Can you do it again?’ They’d simply get the children to play the instruments again. There was no sense that it was anything other than having that set of instruments. So it was when they get to the vernacular and can repeat what they have done, that I became able to transcribe and I did transcribe them and they are there in the thesis.

Anthony: Which is about half-way up the spiral, I think? (See Figure 1)

June: Well, you’ve got the bottom two bits, which are exploring the Materials of sound, so you’ve got, a free exploration of music; and then they can control it with a steady beat and to a certain extent you can write that down, but the beat is often unsteady, because they haven’t got control of their hands sufficiently, so it’s easier to do it with the maracas, than it is to do it with the triangle. So it depends to a certain extent on the development of manual dexterity.

Something without a beater is much easier than something with a beater, where you have to aim straight. But then you get to, a more expressive area, which is the beginning of Expression and it’s at the end of that it becomes refined, so it’s the sort of fourth area and that’s the ‘London’s Burning’ thing.

And then when you get to the area of Construction, you get [claps strong rhythm as clapped before, but with a changed ending] And the child will say, ‘You thought I was going to do it again, didn’t you?! Did I surprise you?’ So now they’re beginning to play with it and it’s formulated.

What are musical values?

Values are generally acknowledged to be important in music education. Philpott describes them as evidence of musical learning (Philpott, Reference PHILPOTT, Cooke, Evans, Philpott and Spruce2016), and Spruce includes them in his descriptions of enculturation that occur in the process of formal education (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, Cooke, Evans, Philpott and Spruce2016). Cain & Cursley (Reference CAIN and CURSLEY2017) include values in their discussion of personal pedagogical modes, where they place values in a practical tradition, centring on the what, how and why, which teachers may adopt in their own teaching practices. However, despite this recent acknowledgement of the importance of values, there has been less discussion in music education of the nature and substance of values. Taking time to consider the nature of Values is important, as it has been argued that in contemporary society values themselves have, through the nature in which they are defined and conceived, become relative or value-free (Wells, 1998) themselves. Boyce-Tillman here describes her philosophy of Values and how these impact musical experience.

Anthony: In what sense do you understand values?

June: It’s a two-fold thing. One is the context in which music is going to be placed and what people are going to make of it. If you’re going to set the room up, for example, with candles and incense – that’s one thing. If you’re going to sit them down in a concert hall, that’s another.

The second consideration is intentionality. What do you want to do? Are you doing it to heal people? Are you doing it to make money? Are you doing it to get esteem? Are you doing it to bring the school together? We’ve been appalling at teaching Values.

I used to do a final year lecture for BMus students at a London based University on intention in music. These students told me, ‘You know we’ve been studying Music for twenty years and nobody’s ever told us that there might be value systems in it.’

In terms of composition, you have to be careful, with children’s music, how far you refine them, because you are bringing your own Values to them, which might not be theirs.

We did take children’s compositions to the Royal Festival Hall and things like that. Then you’ve got various value systems operating. For example, there is one level when you’re in a class situation, where there are various groups composing and sharing and they play their pieces to one another. They’re all in it together. Another level appears when you then say, ‘Well, it would be nice if we played it in assembly, wouldn’t it?’ So you’ve now got a whole load of classes who may have done it themselves, but haven’t been involved in the class where the compositions were first created. Now it’s got to be a bit more polished and as a teacher you have to be a bit clearer about what you’re doing.

Yet another Value system appears when you say, ‘Oh, why don’t we put it in the concert for the parents?’ Now the parents have got an emotional relationship so you’ve got to refine it a bit more there.

If you’re going to put it on the stage for the Festival Hall, when you’ve got a whole load of people who don’t know them at all, then it’s got to be much more clearly defined – you may even have to put something in a programme to help people understand, whereas you don’t need that when you’re just playing it to people who are doing something similar. This is yet another layer in which a further value system is revealed.

That’s Values. You know, how far do you need to contextualise this? What level of perfection do you need? At the Festival Hall, people have paid money to come. In the school assembly, they haven’t.

Anthony: So is it the development of your thinking about Values of which you feel most proud?

June: Well, I think I do feel proud of that, but I also feel proud of the notion of Materials, because I think a lot of people never fall in love with the sound. And we make terrible mistakes.

You know, when we had instrumental lessons and a child said, ‘Well, I really want to learn the clarinet,’ the teacher often has to say, ‘I’m sorry, we only have a double-bass.’ This scenario denies the importance of the level of Materials. Children don’t want to learn music, they want to make a particular sound that they have fallen in love with. Now, okay, it may be that you haven’t got enough of them and there are all those constraints, but, it is the tone colour of a particular sound that we fall in love with. And that’s what that foundation level of the spiral says.

What spaces do curriculum design and curriculum sequencing occupy in the spiral?

It has been suggested that the music curriculum is several curricula in simultaneous co-existent operation (Elliot, 1986), and later developments have suggested that music curriculum is lived experience (Cooke & Spruce, 2016). How music curriculum is sequenced and the impact this has for learning has been infrequently discussed in music education literature, although Philpott (2007) and Anderson (Reference ANDERSON2019) have drawn attention to its importance. However, stems of discussion surrounding curriculum and sequencing in a musical context were evident in Tillman’s (Reference TILLMAN1987) doctoral spiral. These are, to some extent, tacit features, but Boyce-Tillman here gives further commentary on her conceptualisation of these characteristics of curriculum and describes how they relate to the spiral. In order to understand sequencing in a curriculum context, this section is prefaced with a discussion of sequencing as a developmental pathway and the implications this has for the formulation of the spiral.

Anthony: Is Construction where the idea that musical development is sequential comes from?

June: Yes. I would say formulated rather than sequential: it can be repeated.

Anthony: You wouldn’t use the word sequential?

June: No, because the ability to repeat is the important thing. It requires approximately the same physical movement. A child in the vernacular knows that there is a formula. They have a formula that can be repeated. In other words, they can remember what they’ve done.

I think for that bottom level of the spiral, it is very associated with physical movement – ‘What I’ve done is waved my hand around, with a sound making thing in it and this is what happens!’ It’s not primarily about the music, it’s to do with physical movement. Now once we get into the vernacular, it becomes a sound pattern that can be repeated in some way. Of course this is very much like jazz, in a sense. The feel would stay the same, but the notes would change. It’s how orate traditions work.

Anthony: Is this why you conceptualised the sequence of musical development as a spiral?

June: Yes, partly, but I think there are problems with explaining what it’s trying to represent. Originally it was a series of circles and I was trying to work out how it all fitted together. Babies and toddlers are largely interested in exploring the totality of an instrument, not just what sound a thing makes. They would lick it and look at it and hit it and there was no distinction between the ways they explore the world: whether you touch it, lick it, or taste it, or look at it, or hear it. That’s the way their exploration is.

It was the vernacular which was the turning point towards an interest in Construction. The initiation process into a culture is by listening and repeating, and that was happening. My research has been critiqued, because they say that some of the earlier examples do have a form. So it’s been suggested that to say that this was pure Expression with no form is not correct.

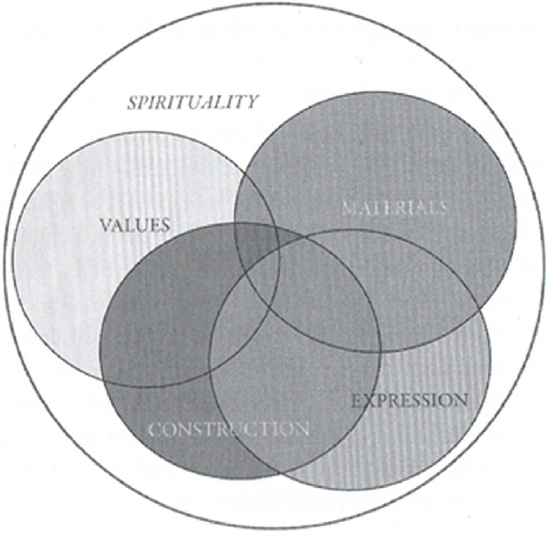

However, I would still say that broadly the young child is interested in tone colour, the growing child acquires the ability to control things and to communicate with instruments or voice, and the older child has acquired the conventions of the surrounding culture and wants to be part of it, and then starts to be able to use that in innovative ways. So the spiral very quickly became a stage-by-stage model. This is why in the end I went back to where I was originally, which was a series of interlocking circles, which is what children (and adults) experience in music.

Anthony: So what direction are you looking from in your multi-dimensional model?

June: So I looked down. I thought what would a spiral look like – or a helix as it should have been – what would it look like if you looked down from the top? And it would look like a series of interlocking circles, which is how I developed my new model. (See Figure 2).

Anthony: Do you see it as a model which you can observe in musical practices?

June: It’s a good model for looking at music education in schools. You could broadly go into a classroom of 3–7 year olds and see whether there are chances to explore sound and whether the capacity of sound to express things is developing. You could look broadly at a class to see whether the capacity of sound to express things is happening. You could look at a class of 7–11 year olds and see whether they are learning how to repeat things, and how Construction works. You could look at secondary school children and ask if they are being initiated in a particular idiom of some kind or other. Is it just one or are there many? Are they learning how sounds are put together? You could make broad assumptions about performing, listening and composing from this.

Younger children are taken up with the instruments, and how do you play it and all of that. Whereas older children will say, ‘Well I felt happy,’ and so on. And then they will notice how musical features come round; they can understand it and perform it.

There was a wonderful story of a teacher who charged one rate for teaching the notes and another if you wanted the expression! [Laughs] And to a certain extent you can’t get any Expression, until you’ve learned how to get the notes down! [Chuckles]

Sometimes you have to get used to a tone colour, before you can be drawn into it. If it is a familiar tone colour it might not take you very long, but, faced with a tradition such as Beijing opera, rather than piano, you have to get your mind round different vowel sounds before you can get anywhere with it.

Anthony: The spiral is a three-dimensional model then?

June: It’s a helix with four dimensions. It should have been called a helix, not a spiral. It is a helix with four turns. You’ve got Materials, Expression, Construction and Values – which is the context in which you’re doing it and whether people are going to pay to hear it, for instance.

Anthony: In that case, how do you think musical development sequences link together with curriculum planning?

June: I think that the model that I have is that musical development sequences always needs to be in the back of your mind whenever you’re teaching. Even teaching the scale of C major is not a given: it’s what a particular group of countries in Europe have chosen to do. It’s not the only way.

It seems to me that we’ve got so hooked in the curriculum on Construction and we still are. Whatever you do, you should be thinking – the curriculum should consist of thinking around those areas. Now whether you want to sequentialise them or not, I think is problematic. Because if your 11 year olds in the school have not had the experience of being able to bang saucepan lids together, when they were a child or in their nursery, you need to find a more sophisticated way of doing it, but the young people have got to do it – they’ve still got to learn to manage the sound.

Anthony: So young people should be driving the curriculum – is that the right term?

June: They should be driving the curriculum!

Anthony: Because the question might be how do teachers do it? Teachers have to conceptualise curricula, they have to plan curricula, they have to evidence what they’re doing to their line-managers, don’t they?

June: I think it’s a dilemma, because I think we’ve created a huge problem for ourselves. Because, you know, your 14, 15, 16 year olds are getting into particular idioms in which they wish to participate. So they might sing in the church choir, they might have a rock group, they might have a folk group, they might be playing in a jazz band… The longer they stay in school, the greater the variety of those idioms are – there’s not a hope that a school can embrace all these traditions.

I saw, at the end of the thesis, that the school should really play the role of a broker out into all of these traditions; that the Head of Music in a school should know where the rock groups, the jazz groups, the church choirs, the string quartets are locally and should be able to link those youngsters up with these local groups. And that might be listening to Stockhausen in the Festival Hall (other people working in the area of composing in the classroom had the intention of providing audiences for avant garde classical music), but it might be singing ‘O for the Wings of a Dove’ in your church choir, or it might be playing in a heavy metal band. The longer you keep young people in school, the harder it becomes to provide experience in a variety of idioms.

Anthony: As I was listening to you, I thought that you were perhaps saying that there wasn’t so much of a place for music in the curriculum and what function does it serve, but then as you’re talking at the end, you seem to be expanding that into thinking about how the spiral can bring it all together – all these different areas. Is that how you see it?

June: I think we have not used enough of the students’ own experiences in our music classes. You know, those youngsters are using music all the time and how often do we have a lesson where they’re able to bring something in, talk about it and that’s placed in this frame? I suppose this is where the value system comes in – the social world and the educational world is disintegrating; school has got to be able to teach in the curriculum as a whole, not just music, respect with diversity. If we don’t do that in school, we will fail the wider society.

Anthony: Is there a link then, into cultural diversity?

June: Yes.

Anthony: Musical identity, cultural diversity.

June: Diversity, that’s right. It’s a link. So the school has to have a link with the wider world. What’s happening often is that you’ve got a school music that bears zilch relationship with anything outside of it. So children either embrace that fully, or they say, ‘School music is rubbish and I’m going to put Spotify on.’

If people understood how different sorts of music make them feel, this would be a big step. When you’re really excited do you want to put on even louder music, or do you realise that if you put on softer music, you could calm yourself down? Do you realise what effect music has on you? Because, actually, music can do what many of our heavy pharmaceutical products can do, if you understand how the music is affecting you. And you can give them those experiences in the classroom. But if you’re busy teaching how to modulate from C major to D minor, then you’re not going to get to how does the modulation from C major to D minor make you feel? So that Expression domain of understanding why and how a person is using music has got to prepare them for the world they’re going into, by seeing the world that they’re in and widening their horizons.

That makes curriculum tricky, because what you’re putting into a curriculum has to be related to where people are; you can think about how you are going to do it in different ways, or introduce different idioms. But always bear in mind that there has to be a scope for the youngsters to bring their own experiences in…Year 7 (your first year at secondary for 11–12 year old pupils)…how are you going to tackle them in Year 8 (the second year of English secondary schools, for 12–13 year-old pupils). You can think about how you are going to do it in different ways, or is it going to be different idioms you’re going to introduce? But always bearing in mind that there has to be a scope for the youngsters to bring their own experiences, particularly in the secondary school. A teacher needs to bear in mind that there has to be a scope for the youngsters to bring their own experiences in. At the moment we’ve got a curriculum which is – ‘This is what you’ve got to learn’ and it’s the empty vessel model of pupils. But, actually, they’re not empty vessels in terms of musical experience at the ages of 14 or 15; they’re very full vessels in a very confusing world.

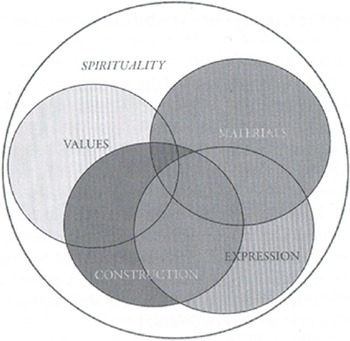

Figure 2. Boyce-Tillman’s The spiritual experience in music, 2006.

Are critiques of the spiral of musical development valid?

In response to some of the critiques which Boyce-Tillman has received about her work, she is philosophical. Just as Bernstein (Reference BERNSTEIN2000) suggested that knowledge can exist as a form of cultural consciousness, so Boyce-Tillman accepts that her earlier conceptualisations of Materials and Values were impacted by her own development and personal circumstances. The notion that staged development takes place in music in a congruent manner to Piaget (Reference PIAGET1926) is one to which she is least attached. Boyce-Tillman embraced the opportunity to develop this point of debate during our discussion:

Anthony: Do you accept any of the criticisms that have been made of your work?

June: Oh yes. I mean, I was very sorry that my supervisor wanted to bring Piaget in. We should have used Vygotsky. We should have used scaffolding. The spiral is a mode for scaffolding pupils’ learning.

Anthony: So, is that one of the things that you would change if you were able to do that work again?

June: Oh yes. My external examiner said in the exam, ‘What about Vygotsky?’ Vygotsky’s idea of scaffolding is essential in a child-centred education. So you can look at what a child is doing and then ask yourself, ‘Is this the time to teach notation?’ or ‘Is this the time to teach crotchets and quavers?’ So you follow the children, rather than prescribing at what age they are permitted to make a particular kind of music. The ages are very rough and different people move at different speeds depending on their experiences.

In a sense, if anyone is going to write a decent piece of music that is going to make sense to somebody else then they have to pay attention to the Materials, to what they want people to feel, and to the way the repetition works. And you also have to understand what your value systems are and where it’s going to be performed.

As a way of starting any project whether you’re 5, 11 or 72 you do well to say, ‘Well, what is it that’s fired you up?’ ‘Well, it’s that beautiful lake over there.’ ‘Okay, well start with Expression.’ ‘Now what range of instruments are you going to use?’ Which instruments are available? Materials at that level are important too, because it’s not much good writing for a cor anglais, if all you’ve got is a clarinet!

Next you need to think how you are going to put it together: is it going to be a classical sort of piece or do you want a folk-type piece? What idiom are you going to embrace? And then, part of that decision will be, are you having to perform it? You know, are you going to do it in a karaoke-type context or do you want it to go on the stage at the Festival Hall?

Anthony: So, when you’re talking about Vygotsky, you’re thinking about a child-centred approach?

June: Yes, child-centred and with scaffolding. If you have an idea of these musical domains, in which you’re going to work, you can see where the child is in those domains.

Anthony: How do you respond to how your spiral has been cited? You can’t read anything about musical development in any sphere without seeing your work. It’s the most widely cited article from the British Journal of Music Education (BJME) in its historyFootnote 2 . How do you respond?

June: Well, I’m honoured and I think it was a good piece of work and I think it cut through a lot of curriculum models at the time; it didn’t actually deny them, but it drew them together in some way. And I think the most dangerous thing was that because it looked hierarchical, that in the end, it became a stage-by-stage model. And it never was that. It was heavily critiqued and there are a lot of articles critiquing that… well, you know, even my baby waving a rattle has got patterns in it, so how can you say Construction doesn’t come until they’re 8?

I think the other thing it did which was helpful, at a time when people needed stage-by-stage models to justify what they were doing, was that it did justify or give some structure for the way you might introduce composing and improvising into the curriculum. And I can remember when I was lecturing in Australia, having finished playing video tapes of myself teaching, I said, ‘I hope that now if you want to introduce composing, I’ve given you a map that will help you to do it.’ The composing and improvising elements of music-making have sometimes caused confusion. My final reference from Mrs. Moore, Head teacher at the girls’ grammar school, was ‘Miss Boyce’s classes are busy, active classes,’ and I never knew whether that was the ultimate condemnation or the ultimate accolade! [Laughs]

Anthony: Did you struggle with anything as you developed the spiral?

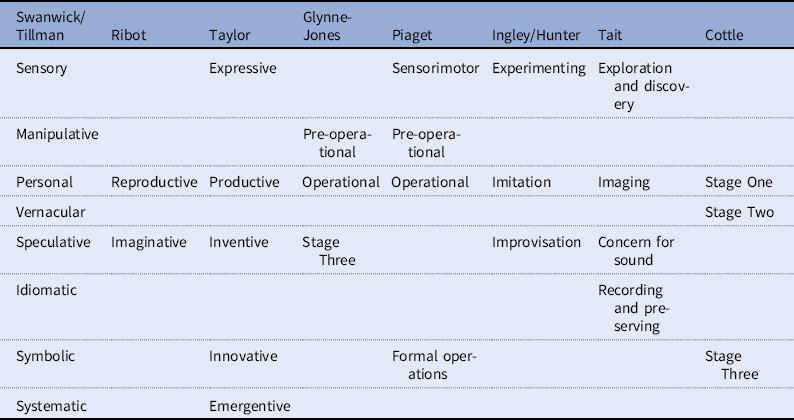

June: One interesting thing was the question that my external examiner asked in the viva, which was, ‘How do you know this isn’t simply the way you teach it, June?’ But in the thesis too, there’s a table of a number of other people, who’d seen very similar things (see table 1); in the end I can remember struggling in my viva and looking at him, sort of open eyed, and saying, ‘Because other people have seen it too!’ [Chuckles]. So there were other bits of the literature on composing and improvising from people who’d seen similar developments.

In my viva I said I didn’t claim that everything I had written was true for all children, but, I’ve seen enough children now, in various cultures and contexts to know that the broad outline has wider applications. Faced with an electronic keyboard, (which wasn’t really around in those days much), the first thing people do is to find out what tone colours there are on it and mess around with it. It’s no good hoping you’re going to start with a formulated tune. The notion that you have to be able to understand whatever Materials you’ve got before you can use them is therefore very important.

Table 1. Comparison of Various Writers’ Views of Children’s Development (Tillman, Reference TILLMAN1987, p.183)

Closing thoughts

This paper closes as the interview did, with Boyce-Tillman’s reflections on the completion of this premiere of her research projects:

Anthony: How did it feel at the end of your research process?

June: I suppose the saddest thing about it, and I should have handled it much better, was when I finally went into the school with my doctoral robes and said to the children, ‘Thank you so much, you know, for all that you’ve done, it’s been wonderful.’ A hand went up and said, ‘Does that mean we won’t be going into that little room anymore and making all those lovely sounds?’

Anthony: So interesting. June, it’s been a fascinating discussion… I don’t know if there’s anything else you want to say?

June: Well, I just hope that my work enables people to create a society where difference is given dignity, then I will have contributed something that’s most important for our society.

Boyce-Tillman exhibits humility in place of hubris in the discussion of her work. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that her spiral of musical development which emerged from her thesis has shown life well beyond the duration of most doctoral theses. It would seem to be unlikely that the next 35 years will be any different from the last 35, and it would seem probable that her work, as realised and developed with Swanwick (Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986), will continue to be embedded in articles in the field of music education. The discourse on musical development will, undoubtedly, continue to be refined. This article cannot explore every avenue of this theme. However, the aspiration has been to revisit, clarify and contribute to ongoing discussion and debate, allowing previously unknown details and complexities to find a voice. In doing so, it is hoped that the article will make both a contribution to musical practices in education and to future scholarship, inspiring new generations in their musical thinking and making.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gary Spruce for his helpful comments and ideas on an early version of this article.

June Boyce-Tillman spiral of musical development selected lectures and keynotes

1985 Children’s Development as Composers. Holland.

1986 Children’s Musical Development. Society for Research into the Psychology of Music and Music Education.

1987 Children’s Musical Development. International Society for Music Education, Melbourne.

1987 Lecture tour of Australia Tasmania. Brisbane, Canberra, Perth.

1989 Singing in the Curriculum. British Music Educators’ Conference.

1989 Children’s Musical Development. Lublin, Poland.

1990 Children’s Musical Development. Belfast Music Educators.

1990 Children’s Musical Development. Conference of Music Education, Gibraltar.

1992 What Shall I Play? Societe Italiane per l’educazione musicale

1993 Assessment of Music and the National Curriculum. UK Council for Music Education and Training, Lincoln.

1994 Assessment of Music at Key Stage Two of the National Curriculum. Barking and Dagenham Education Authority.

1994 Releasing the Musician Within. Hong Kong Music Educators.

1994 The Joy of Musical Games. Hong Kong Music Educators.

1994 Children’s Music Development. Urbana University, Illinois, USA.

1994 Children’s Musical Development. International Conductors’ Seminar, Wellington, New Zealand.

1995 Some Issues in Current Music Education: Gender and Inter-Culturalism. Association of Music Teachers in Independent Schools.

1997 Children’s Musical Development. Maribor University, Slovenia.

2006 Children’s Musical Development. Columbia University, New York, USA.

2010 Guest Lecture. Kingston University.

2013 Keynote Lecture, Workshops and Interviews. Japanese Women’s University, Tokyo.

2013 Music as Integrative Experience Keynote. International Conference on Art and Cultural Advocacy, URP Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok.

2017 Reshaping Music Education: redrawing the lines, paper in Celebration, Commemoration and Collaboration. Milestones in the History of Education Conference, The University of Winchester.