In the past decade, scholarship on race in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) has increasingly embraced Critical Whiteness Studies (CWS) to better understand the relationship between race and identity in the region.Footnote 1 Partly driven by debates on “Europeanness” and the growing xenophobia against central and east Europeans in western Europe—especially in Britain after Brexit—this scholarship critiques the notion of a “raceless”Footnote 2 or post-racial CEE. In doing so, it highlights the significant role that “whiteness” plays in shaping cultural norms, political debates, and public attitudes in the region.Footnote 3 As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed has noted, whiteness should not be described as an “ontological given” but “as that which has been received, or become given, over time.”Footnote 4 While western Europe, North America and regions in the Global South are grappling with their histories of race and racism shaped by slavery, colonialism, and imperialism, these concepts are often considered to have little or no role in shaping debates on national character in CEE.Footnote 5 The narrative of non-involvement in transatlantic slavery and colonialism consequently strengthened the prevailing perception of the region as racially neutral, a view which also shaped much of the socialist rhetoric developed during the Cold War.Footnote 6

For example, the fact that the Roma people were enslaved for almost five centuries in Moldova and Wallachia was conveniently ignored until very recently.Footnote 7 Similarly, few scholars acknowledged the fact that, during the 1930s and early 1940s, theories of race were eagerly embraced not only in Paris, London, and Berlin but also in other cities such as Bucharest, Budapest, and Warsaw. During this period, Romania and other nations in CEE generated their own versions of whiteness that were wedded to debates on national character. In interwar Romania, a distinct notion of whiteness prevailed that was driven by a racist belief that “pure-blooded Romanians” (românii de sânge) were ethnically distinct from marginalized groups such as Roma.Footnote 8 This distinction assigned whiteness to presumed native Romanians, while blackness was attributed to Roma communities. One cannot understand the former description without a proper understanding of the latter. In this context, skin color worked with other factors such as nomadism, “backwardness,” and non-European origins to shape, not simply reflect, the projection of blackness onto the former Roma slave communities.Footnote 9 Consequently, making whiteness visible was paramount in both defining national belonging and delineating ethnic and racial boundaries.Footnote 10

Public discussions in which the concept of race was taken seriously were slow to emerge in Romania, notwithstanding the intense focus on nationalism after 1989.Footnote 11 It was the growing interest in the history of eugenics in CEE―itself an area completely ignored by scholars until the late 1990s―that provided the much-needed reappraisal of outdated historiographic interpretations of the national past, which ignored the relevance of race.Footnote 12 Through the prism of eugenics, it became possible to explain how the body of the nation was recurrently racialized, and thus the centrality of race to the project of national belonging.Footnote 13 This made the categories of whiteness and blackness visible across multiple intersecting aspects of identity, not only in terms of ethnicity but also through social and cultural dimensions. This process of racialization survived the end of the Second World War. While racism was indeed abandoned officially, eugenics was reinscribed into the emerging socialist worldview, targeting social rather than racial degeneracy.Footnote 14 This transformation gave rise to what feminist scholar Miglena Todorova terms “socialist racialism,” a framework that distinguishes racial formation in socialist states from Euro-American models and highlights the unique operations of racial sciences and imaginaries under socialism.”Footnote 15

In the rest of this article, we consider the ways in which blackness and whiteness are formulated in dialogue with each other. By emphasizing the role of race in the production of these categories, we attempt to re-problematize not only the concept of national belonging and its application to the Roma peoples, but also the very notion of a post-racial CEE. To do this effectively, we focus predominately on how various Roma communities were ascribed negative traits, portrayed as racially inferior and culturally backward, and perceived as non-white within the Romanian worldview. What whiteness has done―and continues to do―to Roma people must be historically contextualized. Beyond this, we can see how the idea of Roma blackness emerged in interwar Romania and elsewhere in CEE as the result of a long process of rejection from the dominant nation, which self-identified as native, European, and therefore as white.

“Black” Roma in Interwar Romania

At this juncture, it may be useful to highlight how racial traits were attributed to various Roma communities in interwar Romania. These traits marked the Roma as specimens of a different kind of humanity, much as scientific racism has repeatedly categorized Black populations globally.Footnote 16 Here, a useful example comes from Ion Chelcea, a Romanian ethnographer, who in the early 1930s sought to describe the Rudari community (also known as Boyash or Băieși) from the Apuseni Mountains in Transylvania. Chelcea believed that this community could be easily identified as representing an inferior form of humanity based on their phenotypical characteristics. Many Rudari, Chelcea claimed, had a “platyrrhine nose,” which was a “sign of their racial primitiveness.”Footnote 17 Similarly, in a book published in 1944, Chelcea did not hesitate to suggest that some nomadic Roma, those who were deemed the least mixed with Romanians, should be spared sterilization and deportation to Transnistria. This was not an expression of a humanitarian impulse; in this context these nomadic Roma people were seen merely as objects for preservation, akin to being displayed in a “human zoo,” where the public could come and see them and where anthropologists could in turn search for answers about their ethnic specificity and pathology.Footnote 18

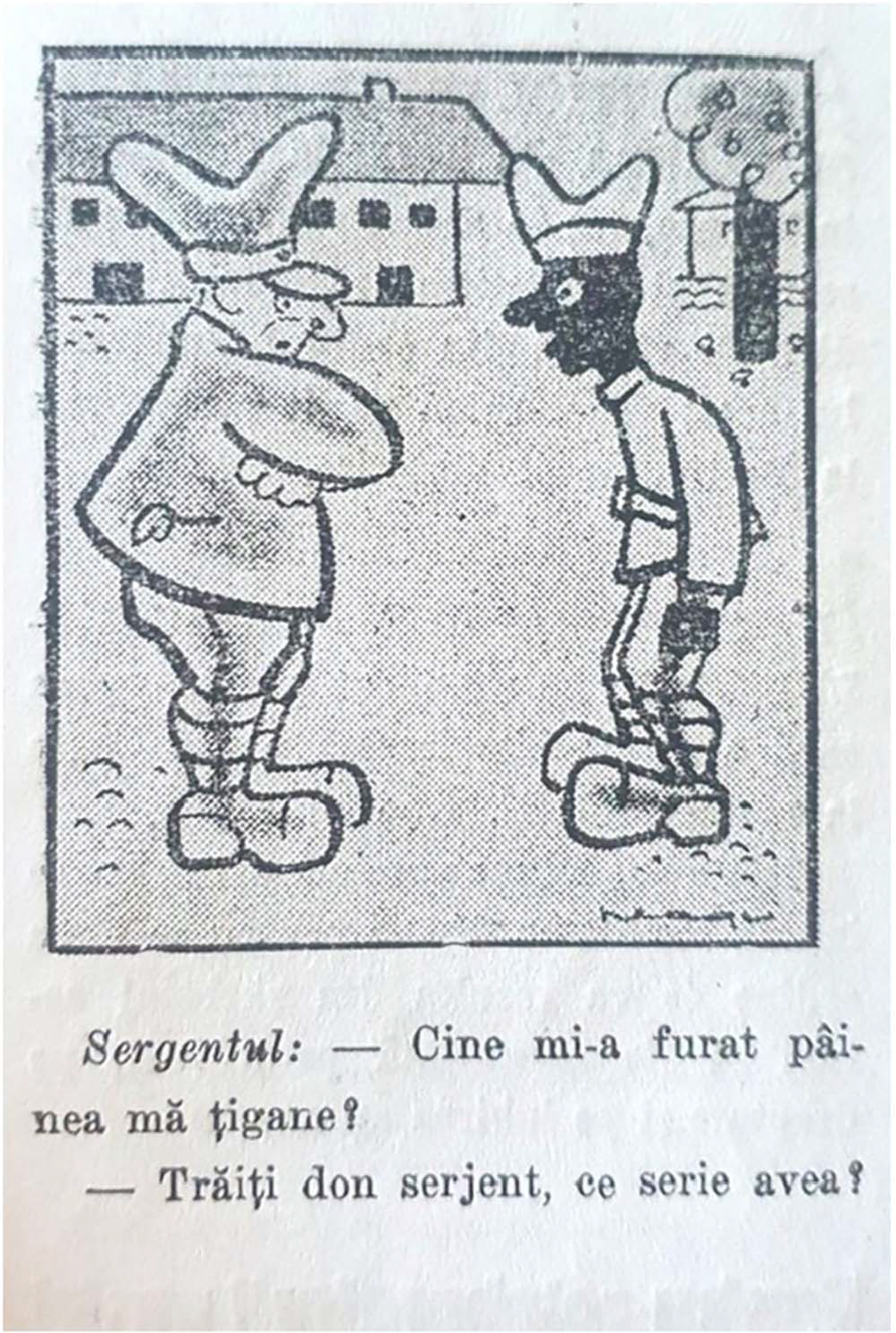

Furthermore, the representation of Roma people as Black appeared not only in articles dealing with the anthropology of the Romanians, but also in newspapers and popular magazines. One evocative example is provided by the Romanian newspaper Sentinela: Gazeta ostăşească a naţiunii (Sentinel: The Nation’s Military Gazette) in its June 30, 1940 issue. To counterbalance the seriousness of military communiques and official proclamations, the newspaper devoted one page to jokes, cartoons, and caricatures, fittingly entitled the “Happy Page,” with contributions from the Romanian writer Neagu Rădulescu. In one such comic strip, a Roma soldier is being questioned by his superior, a sergeant, to ascertain whether he stole his bread, directly invoking the pervasive stereotype of Roma people as thieves. As clearly demonstrated in the image below, Rădulescu depicted the Roma soldier as a Black person, contrasting him not just socially but also racially with the assumed white Romanian.Footnote 19 In this context, under the guise of humor, Roma characteristics are racialized through blackness, reinforcing a widely held perception of the Roma people in Romanian public imagination (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Representation of a Roma soldier as Black. (trans. Sargeant: Hey Gypsy, who stole my bread? — Sir, Sargeant, what serial number did it have?).

In keeping with the above representation, the manner in which some Roma people were assumed to desire whiteness was redefined. This form of “passing” suggests the ways in which some Roma people assimilated into the dominant community. Such reasoning goes back to a distinction made by the physician Leopold Glück, who worked in hospitals in Sarajevo in the 1890s, between the nomadic Black Roma (schwarze Zigeuner) and the white assimilated Roma (weisse Zigeuner).Footnote 20 In this context, the former spoke Romani and kept up their lifestyle and customs, while the latter had adopted the language of the dominant groups, absorbing the identity offered by the white environment into which they aspired to integrate. This was often perceived by the majority as a false, almost fraudulent, assimilation.

The racialization of Roma as Black, went beyond skin color. Their perceived social degeneracy, a result of their former existence as slaves, was also highlighted. For example, in 1932, a Romanian researcher traveled to Bessarabia to evaluate the social integration of formerly enslaved Roma communities within the region’s former Romanian villages. During her visit, she encountered a resident who insisted that the Roma in his community, as former slaves, could never truly become Romanian, even if they had changed the color of their skin to white.Footnote 21 In this situation, there were assumptions that some Roma had attempted to turn white, culturally and linguistically, and thus to pass as Romanian. Here, ontological borders were crossed, and the anxious resident insisted on maintaining the separation of those defined as Romanian by blood from those who only claimed to be Romanian through marriage or other forms of assimilation.Footnote 22 The situations described above obstruct any effort to open up communities to outsiders, particularly if those outsiders are perceived to be Black.Footnote 23 This suggests that being foreign connotes strangeness and unfamiliarity. Such perceptions regard blackness as an identity to be avoided or as something that is specific to the Roma.

Racialization of Blackness Elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe

Looking now beyond Romania, there are numerous contemporary examples of how the putative blackness of the Roma continues to be racialized in CEE in opposition to the assumed whiteness of the ethnic majorities. The role of whiteness in this context must be understood within a broader historical framework. Whiteness and blackness are historically, culturally, and geographically contingent. Their meaning has changed over the course of time, but it should not be assumed that they had always been defined in opposition to each other.Footnote 24 It took centuries for whiteness to emerge, not just as a symbol of power and domination, but also as the normative European identity.Footnote 25 This was particularly evident in the sixteenth century, in the historical entanglement between whiteness and blackness that enabled the creation of empires and nation-states, solidifying and legitimizing racial regimes across the world. It also shaped and was shaped by racism and the variegated traditions of race which flowed from it. While whiteness entrenched itself within the matrix of global culture and politics, blackness―its historical counterpart―was constructed as the opposite of it. From the eighteenth century onwards, whiteness became the criterion of inclusion and exclusion in the emerging nations of Europe and the Americas. Consequently, whiteness, as aptly summarized by the African-American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, soon became “the ownership of the earth.”Footnote 26

Importantly, CEE adds a distinctive dimension to the broader framework of whiteness through the racialization of ethnic minority groups systematically positioned as the region’s symbolic blackness.Footnote 27 Starting in the late nineteenth century Roma, along with Jews, were singled out as the epitome of a dysgenic Other in CEE. During the heyday of scientific racism, institutional violence was directed toward the Roma, whose normative definition of belonging was racially codified. To this end, Roma people’s lives were constantly surveilled, their bodies recurrently examined, their right to exist treated as something yet to be determined. Often, scientific research that attempted to explain their ethnic traits was unethical and carried out without their consent, and these practices continue to this day.Footnote 28 The concept of blackness, we argue, helps to better understand the inferiorization of Roma peoples. In pursuit of a homogeneous white space, after the First World War, nations in CEE imposed surveillance and regulation of Roma bodies. During the interwar period, eugenics completed this process of racialization. Nomadic and sedentary Roma communities were stigmatized and dehumanized to justify their excision from the national community.Footnote 29

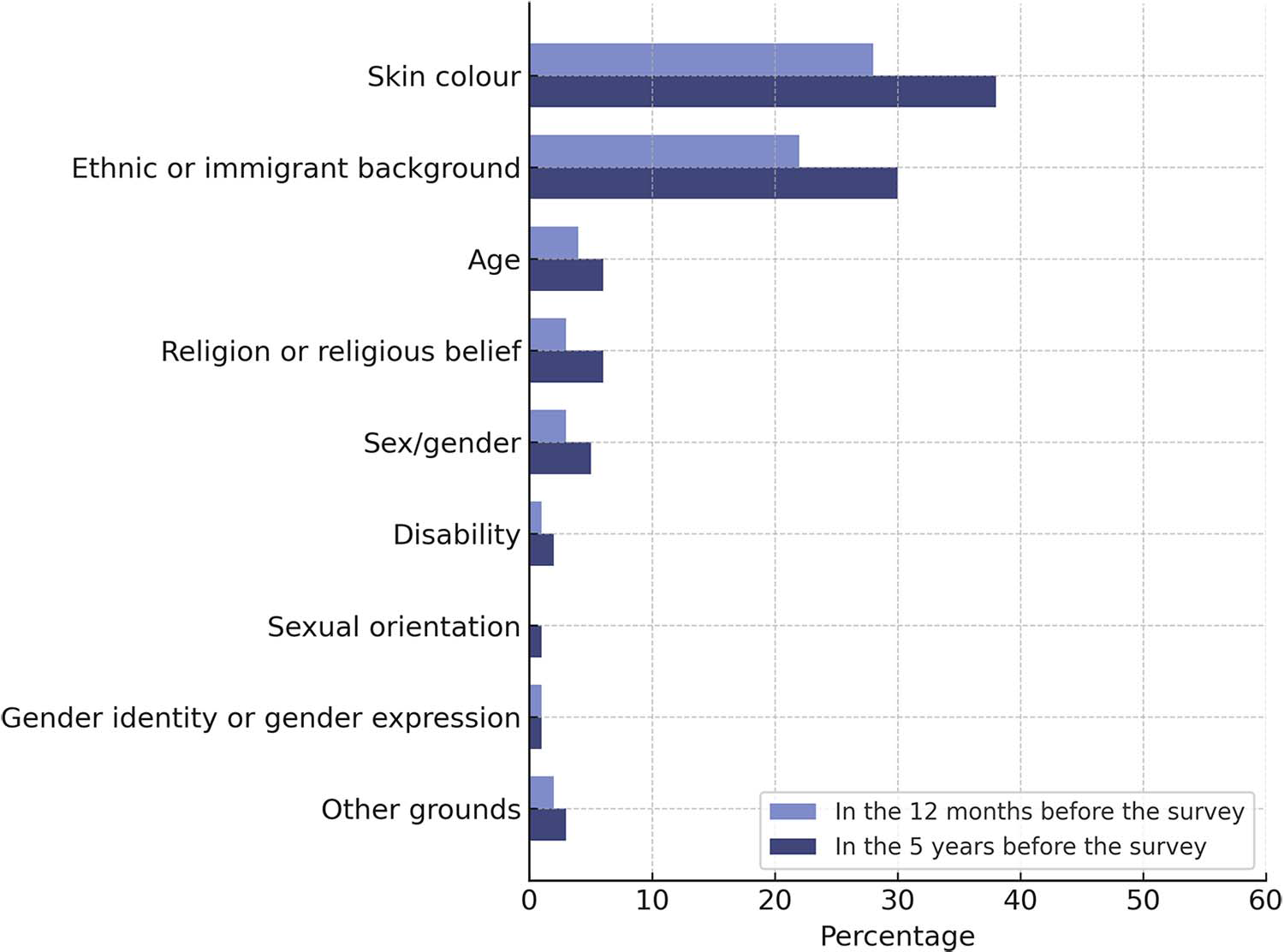

The above logic of racialization of Roma peoples as Black manifests itself in several ways that include language and culture. For example, scholars have demonstrated that the division between whites and Blacks is deep-seated in Polish culture, leading to people of African descent being perceived through a racialized lens.Footnote 30 The Polish term Murzyn (Negro/Black), which refers to people of color regardless of their ethnicity or nationality, systematically reinforces a distinction based on skin color. In this way, blackness is categorized and labeled in multiple ways that are influenced by racialized norms, informed by stereotypes that portray Black or colored individuals as perpetually foreign. This categorization shapes not only racial discourse but also everyday language that serves to highlight whiteness in Poland. Several other cultural expressions tie neatly to these views, as evident in common Polish expressions such as pracować jak Murzyn (work like a Negro), which invokes a similarly inferior connotation of blackness in the Russian expression pashet kak negr (works hard like a Negro).Footnote 31 Similarly, expressions such as “In Slovakia, you will always be only a black Gypsy!” or “Gypsies will always be humiliated” do more than simply reinforce the binary between the Black Roma and the white Slovaks. They also indicate the measures of “darkness” against whiteness. Here, the perception of the Roma through the lens of blackness does not exist in a vacuum. As Jan Grill argues, it is interwoven with the assumed categories of Slovak “nation (národ), nationality (národnosť), and ethnicity/ethnic identity or culture (kultúra)” that are frequently blurred in everyday usage, serving as equivalents to race.Footnote 32 In this way, the term černoch (black person) signifies a distinction from Slovaks’ whiteness. These expressions in Polish, Russian, and Slovak―though merely minimal examples―reinforce the racialization of blackness as an inferior identity. As political theorist Cedric Robinson notes, what matters is the “assertion of the sanctity of whiteness and the shame of blackness.”Footnote 33 In this sense, skin color appears to have an objective reality that seems “visible” and “measurable” with meaningful and impactful effects on non-white identities. It provides a window into the way people perceive “human difference that uses notions of genealogy, ‘blood,’ and inheritance as ways of conceptualizing differences and similarities, individual and collective, between people.”Footnote 34 This is exemplified by the 2023 EU survey showing that many people of African descent living in the EU feel that some of the discrimination they face is based on the color of their skin (Figure 2).Footnote 35

Figure 2. Grounds of discrimination experienced by people of African descent.

To understand and engage with the above provocations, one must first understand the longstanding traditions of both acceptance and rejection of the Roma people in CEE. The inclusion and exclusion of Roma communities have been shaped by definitions of identity that stigmatize them as foreign members of the nation, whose ethnic origin is described as non-European and whose presence in society is deemed problematic. In this context, national belonging is closely tied to the “native” population, and this form of autochthonism became not only a marker of national belonging but also a framework for the social, cultural, and political transformations that persisted from the interwar period through the socialist era. These attitudes, in turn, deeply influenced perceptions of the Roma in the post-communist period.Footnote 36

This short article has explored several manifestations of blackness, especially those reinforcing the inferiorization of Roma people in interwar Romania and beyond. In doing so, it contends that decolonial pedagogies in CEE more broadly are inadequate unless they address the influence of whiteness within debates on national character, while also emphasizing the often-neglected importance of blackness in shaping national identities in the region. This neglect has given rise to identity categories and hierarchies in which blackness has been, and continues to be, regarded as inferior to whiteness. Whiteness, in turn, has been embraced as the dominant national identity that defines who is and is not considered Romanian, Polish, or Slovak.

By examining the historical and contemporary marginalization of Roma communities, we underscored how racial categorizations have permeated debates on national character in CEE. We also aimed to critique national historiographic canons in CEE which not only neglect the role played by race in processes of nation-building, but also ignore whiteness and blackness as key markers of ethnic belonging. To this end, the Roma had always existed at the margins of whiteness, never fully accepted as members of the idealized nation.

Invoking examples from the interwar period suggests that the racialization of Roma peoples as Black had played a crucial and constitutive role in their perception by the “white” majority. Therefore, it is essential to expand CWS beyond its Euro-American focus to encompass the diverse racial dynamics in CEE. This expansion not only enriches our understanding of race and identity in the region but also contributes to global discussions on the intersections of race, nationalism, and processes of inclusion and exclusion. By focusing on the specificity of blackness in CEE, we call for a more inclusive approach to studying and addressing racial inequalities in a region that produced a very different engagement with race than traditional historical narratives currently suggest.

Marius Turda is Professor and Director of the Centre for Medical Humanities at Oxford Brookes University, having previously taught at University College London and University of Oxford. He has authored, co-authored and edited more than 20 books on the history of eugenics, race, and racism in East-Central Europe and beyond. He is the General editor of A Cultural History of Race published in 6 volumes (2021; paperback 2025). His latest book is In Search of the Perfect Romanian: National Specificity, Racial Degeneration and Social Selection in Modern Romania (2024; Eng. ed. 2026). He has also curated four exhibitions on eugenics, racial anthropology and biopolitics, most notably the one entitled ‘We are not Alone’: Legacies of Eugenics (2021-present).

Bolaji Balogun is a Lecturer in Sociology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. His research focuses on the intersection of Race, Migration, and Colonization in central and eastern Europe. He has authored multiple articles in leading interdisciplinary journals such as the Journal of Ethnic & Racial Studies, Sociological Review, and Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies. He is the author of Race and the Colour-Line: The Boundaries of Europeanness in Poland (Routledge, 2024).