Food insecurity (FI) among higher education students, hereafter referred to as students, is an ongoing public health nutrition issue. Recent studies conducted across higher education institutions have reported prevalence estimates ranging from 19 % to 56 %(Reference Whatnall, Hutchesson and Patterson1–Reference Bruening, Argo and Payne-Sturges4). FI is defined as a lack of access to healthy, nutritious, culturally appropriate and affordable foods(5). This issue has been increasingly studied in high-income countries, with contributing factors including the recent pandemic, cost of living pressures and increasing privatisation of campus food outlets in higher education settings(Reference Jeffrey, Dyson and Scrinis6,Reference Mihrshahi, Dharmayani and Amin7) .

As a result, students are more likely to skip meals and compromise the nutritional quality of their food(Reference Jeffrey, Dyson and Scrinis6). In recent years, this has led to a growth in research efforts to understand the complexity of student FI and develop solutions.

Commencing higher education is a key transitional period, particularly for international students and those living out of home for the first time(Reference Worsley, Harrison and Corcoran8). Students are often faced with academic and financial pressures associated with tuition and accommodation, sometimes compounded by a lack of family support and knowledge gaps in food preparation(Reference Loofbourrow and Scherr9). Evidence indicates FI among students is linked with poorer mental and physical health outcomes including higher BMI and depression(Reference McArthur, Ball and Danek10–Reference Cedillo, Kelly and Davis13). Studies have identified that student food security barriers are often related to time scarcity, insufficient money for adequate, healthy foods(Reference Broton, Weaver and Mai14) and a lack of access to culturally appropriate foods, particularly for international students(Reference Bauch, Torheim and Almendingen15). This can lead to the sacrifice of nutritional quality for meals that are more accessible, increasing obesogenic behaviours(Reference McArthur, Ball and Danek10,Reference Huelskamp, Waity and Russell16) . Campus food environments are also influential in determining student dietary choices, and there is often a lack of healthy and affordable food options available on higher education campuses(Reference Henry17,Reference Keat, Dharmayani and Mihrshahi18) . FI in students has also been associated with poorer academic outcomes including lower grade point averages and class attendance(Reference McArthur, Ball and Danek10,Reference Silva, Kleinert and Sheppard19,Reference Brownfield, Quinn and Bates20) .

Patterns of FI amongst students are often tied to social and economic inequities. Several studies have shown how FI disproportionally affects students because of factors such as race(Reference Brown, Buro and Jones21,Reference Willis22) , international enrolment(Reference Mihrshahi, Dharmayani and Amin7,Reference Shi and Allman-Farinelli23,Reference Kent, Visentin and Peterson24) , gender(Reference Kent, Visentin and Peterson24), socio-economic status(Reference Hughes, Serebryanikova and Donaldson25), living away from home(Reference Kent, Siu and Hutchesson26) and existing household FI(Reference Broton, Weaver and Mai14). Recent research has also demonstrated that food-insecure students may simultaneously experience other insecurities related to basic needs and housing(Reference Payne-Sturges, Tjaden and Caldeira12,Reference Silva, Kleinert and Sheppard19) .

Increased awareness of this issue has prompted higher education institutions to develop programmes that attempt to meet students’ food needs. The most common solutions offered by higher education institutions include campus food pantries, student meal plans and financial assistance programmes(Reference Loofbourrow and Scherr9). Whilst these efforts play an important role in increasing access to food, the persistently high prevalence of FI among students, suggest they may not fully meet the needs of students. Most food security programmes are food relief-centred(Reference Gallegos, Booth and Pollard27), which can risk perpetuating the stigmatisation of already marginalised food-insecure students(Reference McNaughton, Middleton and Mehta28). There is also evidence that existing food-relief programmes often do not meet nutritional needs(Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn29). This points to the need for more multidimensional strategies including those at an institutional governance level to support and prioritise FI(Reference Loofbourrow and Scherr9). Such strategies may include policies and procedures, that allow for monitoring, investments and infrastructure to support effective and sustainable programmes(Reference Savoie-Roskos, Hood and Hagedorn-Hatfield30).

Although there is burgeoning research in this area, there tends to be a strong focus on identifying the extent of the problem through passive forms of engagement with students rather than in the development of solutions. Despite being key stakeholders and end users of the FI initiatives, students’ voices, perspectives and lived experiences are often underexplored(Reference Abu, Tavarez and Oldewage-Theron31). Effective engagement with a variety of stakeholders, including end-users, in the design and development of solutions may offer more inclusive and sustainable strategies(Reference Duea, Zimmerman and Vaughn32,Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge33) . This approach may also strengthen student agency, a pillar of food security recently defined by Clapp et al. as ‘the capacity of individuals to contribute meaningfully to the processes that govern their food systems’(Reference Clapp, Moseley and Burlingame34). By engaging with students who are directly affected by FI, through participation in research and decision-making processes, institutions can better tailor initiatives to address specific needs and barriers.

Research methodologies that emphasise participation are becoming increasingly popular in addressing public health issues(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge33,Reference Cargo and Mercer35) . Participatory research is a broad term describing research designs, methodologies and frameworks used to elicit ‘direct collaboration with those affected by the issue being studied for the purpose of action or change’(Reference Cargo and Mercer35). Participatory research methods can vary, from conventional surveys and focus groups to more involved methods such as community-led research(Reference Vaughn and Jacquez36). Participatory research methods can allow for co-design, where stakeholders collaborate with researchers to design and develop solutions or interventions that meet the needs of the population being studied, ensuring outcomes are relevant, effective and tailored to their specific context.

With the increasing recognition of student FI, higher education institutions are poised to integrate new strategies and institutional policies, that should embody students’ experiences of FI and their perspectives of effective solutions. This scoping review aims to describe and evaluate evidence of student participation in research and identifies strategies related to FI in the higher education setting. The following research questions guided this scoping review: (1) Is there evidence for the integration of co-designing methodologies in research aimed at addressing student FI? (2) What strategies and outcomes have resulted from utilising these methodologies? (3) Are there any barriers to student participation in collaborative research methodologies?

Methods

A scoping review was selected due to its capacity for broad exploration of the existing literature, particularly given the nascent nature of research on campus FI, as evidenced by the lack of comprehensive reviews. This scoping review follows Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage methodological framework(Reference Arksey and O’Malley37). The review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (see Supplementary File 1)(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin38). There was no quality appraisal as per scoping review guidelines(Reference Arksey and O’Malley37,Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin38) . A title and abstract review were conducted by one reviewer (T.S.), and articles that did not meet the defined inclusion criteria were excluded. Full-text review was then undertaken by three reviewers (T.S., N.F., G.G.). In the case of disagreement, reviewers discussed eligibility and came to a collective agreement. A protocol further detailing the study’s methodology and search strategy is publicly available through Open Science Framework, doi: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/573NT.

Search strategy and study selection

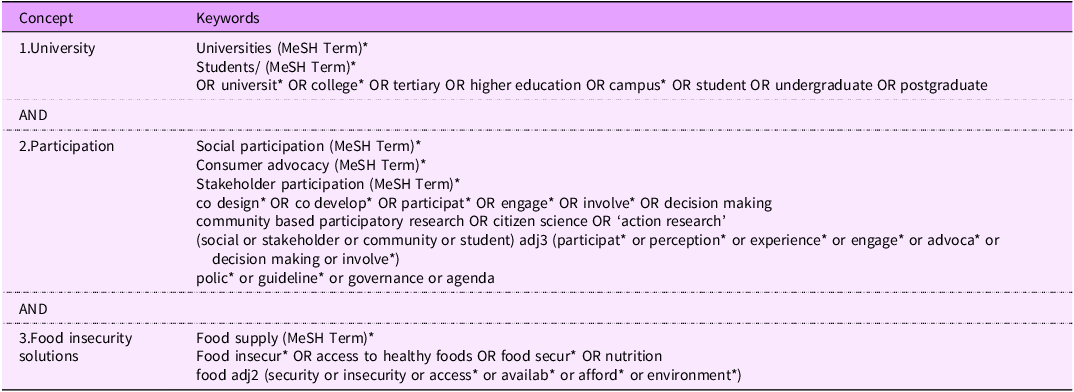

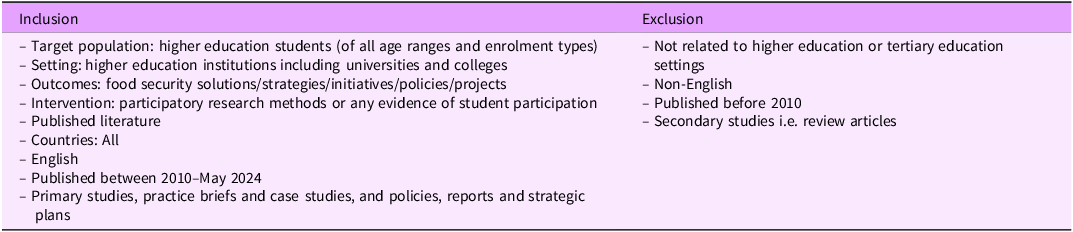

A preliminary literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE and Google Scholar to identify key search terms. Medical subject headings (MeSH) terms were selected accordingly. A search strategy was developed and piloted based on key terms identified and concepts derived from the research questions with the assistance of a clinical librarian. A systematic search using three academic databases, Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science was then conducted. An example of the search strategy is presented in Table 1. The scoping review considered all peer-reviewed primary studies and grey literature published from January 2010 to May 2024, with the exclusion of review articles. Studies were selected if they met the criteria in Table 2.

Table 1. Search terms and concepts developed for Ovid MEDLINE database

*Includes all subheadings.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for academic and grey literature

A grey literature search plan was developed for Google and Google Scholar. The advanced search feature was used to enter search terms and limit the search from January 2010 to May 2024. To further narrow the search, filtering for English language and PDF file types was applied. The search strategy included the following search terms: (university OR higher education OR college OR campus) AND (food security OR food insecurity OR food access OR food environment) AND (engagement OR participatory action OR engagement OR co-design OR co-develop OR participatory research). Due to the complexity of screening all retrieved results from Google and Google Scholar, the relevancy ranking in these search engines brought the most relevant results to the top. Then, the first ten pages of each search hit (∼100 results in total) were screened, including the title and if provided, the summary or abstract. The search strategies including the filters applied, number of hits and search terms were recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. After screening, potentially eligible grey literature was uploaded into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet before undergoing a full-text review. Grey literature was in the form of policies, strategic plans and reports that met the criteria in Table 2 and was from English-speaking countries including but not limited to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, United Kingdom and United States.

Key terms and definitions

Studies were assessed for their inclusion of key concepts related to the research questions. Such concepts are outlined here along with their definitions and the approach used for assessment.

The United Nations Committee on World Food Security describes food security as ‘the physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’(5).

In this scoping review, studies addressed any aspect of food security associated with the six pillars of food security – availability, access, utilisation, stability, sustainability and agency(Reference Clapp, Moseley and Burlingame34). Recognising that food and nutrition security often overlap, studies involving nutritional interventions were considered in the review process.

Higher education, also known as post-secondary education or tertiary education, refers to any form of education that takes place after the completion of secondary education. The structure of higher education may vary by country; however, it generally includes institutions such as universities and colleges that offer academic, professional or vocational qualifications.

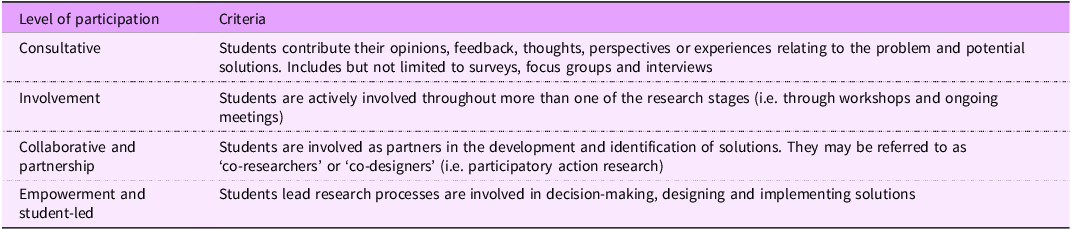

Co-designing can promote meaningful participation evoking individuals’ or groups’ perspectives, insights and ideas, with their input being taken into account in shaping outcomes, actions or policies(39). The level of participation is often proportional to the degree of influence students have in the research and decision-making process(Reference Vaughn and Jacquez36). The International Association of Public Participation’s (IAP2) Spectrum of Participation was adapted to assess studies and define a specific level of student participation in the research (see Table 3)(40).

Table 3. Level of student participation in research for food security solutions, adapted from IAP2 spectrum of public participation(40)

Participatory research sometimes incorporates specific methodological approaches, utilising conceptual frameworks, models or theories such as participatory action research, community-based participatory research, citizen science and participatory evaluation(Reference Vaughn and Jacquez36).

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction variables were selected, and a table in Microsoft Excel was iteratively developed and piloted. Data extracted from the literature included the following information: author, publication year, title, document type, country, study design and methods, study objective(s), setting, participatory model or framework, stakeholder involvement or partnerships, student demographic characteristics, outcome(s), student mode of participation, stage of research cycle, study findings (key strategies), student perceptions and limitations and barriers to student participation. Data were assessed based on the participation level (Table 3) and the step of the research process where participation occurred. The five-step research process was based on the National Health and Medical Research Council’s research cycle(41). Additionally, the themes, tools and features of participatory methods were organised into the domains specified by Duea et al. (2022): (1) Engagement and capacity building; (2) Exploration and visioning; (3) Visual and narrative; (4) Mobilisation and (5) Evaluation(Reference Duea, Zimmerman and Vaughn32). A simple content analysis approach was used to categorise the strategies and solutions identified in the included studies(Reference Hsieh and Shannon42). Using Microsoft Excel, one author (T.S.) repeatedly read the extracted text and inductively created descriptive codes that described the type of strategy or solution. Categorisation of strategies and solutions was primarily inductive; however, the socio-ecological model was considered during this process, as the resulting categories loosely aligned with its recognition of multiple levels of influence affecting students. Given the interpretive nature of this analysis and the author’s familiarity with the topic of FI, which may have influenced the interpretation of strategies identified, academic researcher reflexivity was considered to account for the author’s familiarity with the topic and academic background. There was regular consultation with co-authors (N.F. and G.G.) who acted as secondary reviewers to this coding and categorisation process. This helped with potential uncertainty and bias around interpretation, supporting the grounding of findings in the data rather than being influenced by one author’s perspective.

Results

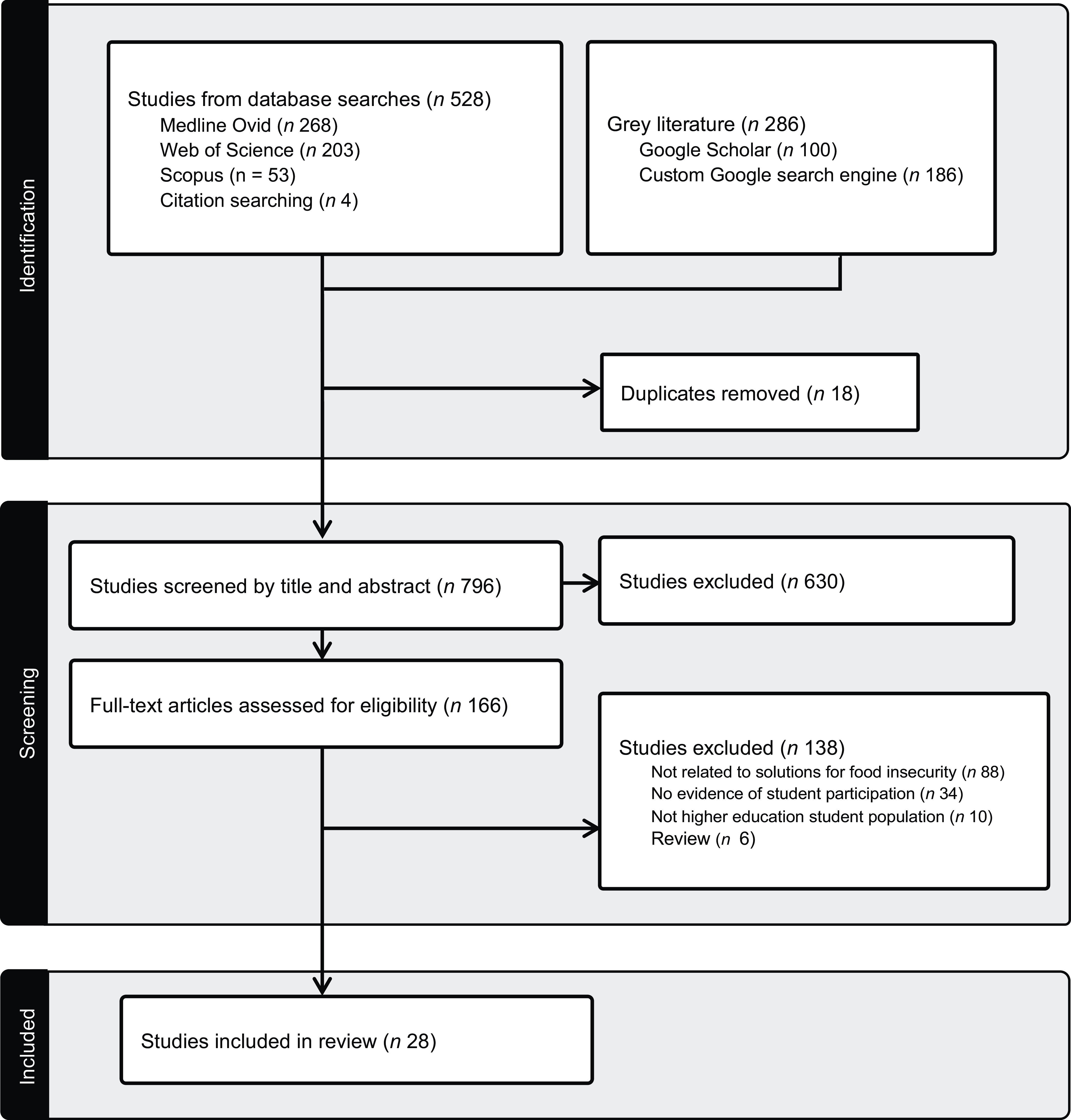

As shown in Figure 1, there were 528 results generated from the primary search strategy in three academic databases and citation searching. A total of 814 articles were screened, including 286 results from grey literature sources. After excluding 648 articles, the remaining 166 underwent full-text review by three reviewers (T.S., N.F. and G.G.). There were 138 articles excluded with reasons documented, resulting in twenty-eight studies included in the review. Findings related to the study characteristics; student participation; stakeholder partnerships and collaborations and outcomes; barriers to student participation and strategies will be provided in this section.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram: co-designing solutions for addressing student food insecurity.

Study characteristics

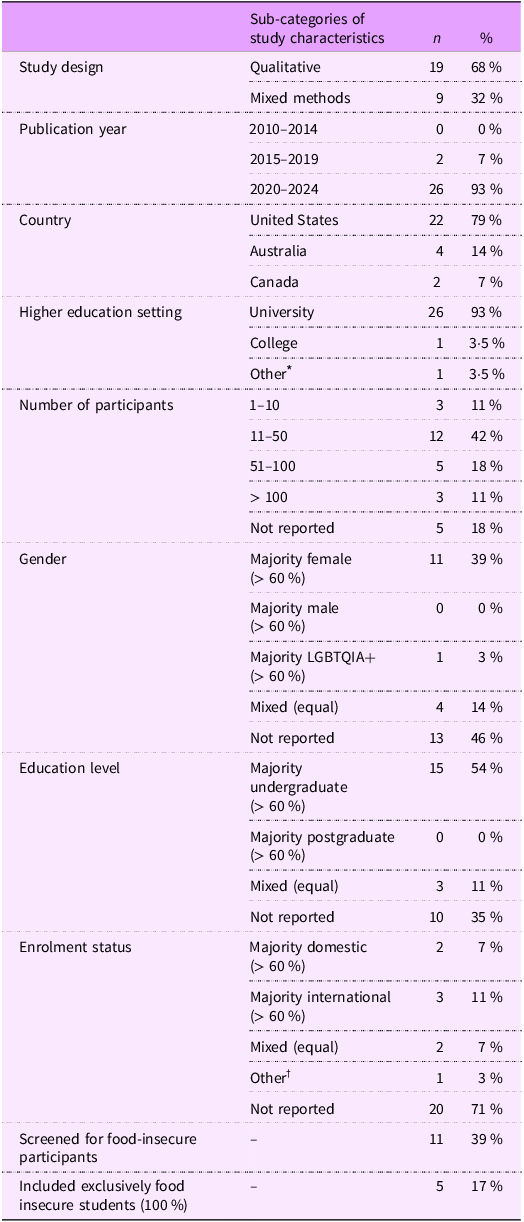

The studies were heterogeneous in study design and scope. These characteristics are detailed in Table 4. The majority of studies were conducted in higher education settings in the United States (n 22, 79 %), and the remaining in Australia (n 4, 14 %) and Canada (n 2, 7 %). The publication dates of included studies ranged from 2017 to 2023, with the majority of studies conducted between 2020 and 2024 (93 %). The study designs were classified as either qualitative (n 19, 68 %) or mixed methods (n 9, 32 %). The included grey literature was in the form of reports, strategic plans and panel summaries where co-design methodologies were utilised. Of the studies included, the majority were situated in the university setting (n 26), and the remaining were in a community college (n 1) and a Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institute setting (n 1). There were eleven studies that specifically screened students for FI who were involved in the identification of solutions in some way (39 %) and five that explicitly involved students who had been identified as food insecure (17 %). The measures used to screen food security status varied across studies. These included the United States Department of Agriculture Six-item Short Form Food Security Survey Module (n 4), United States Adult Food Security Survey Module (10 item) (n 2), Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (n 1), self-identified food insecurity (n 2) and one study where the measure was unclear (n 1).

Table 4. Summary of study characteristics

* Technical and further educational institution.

† Military-connected students.

Student participation

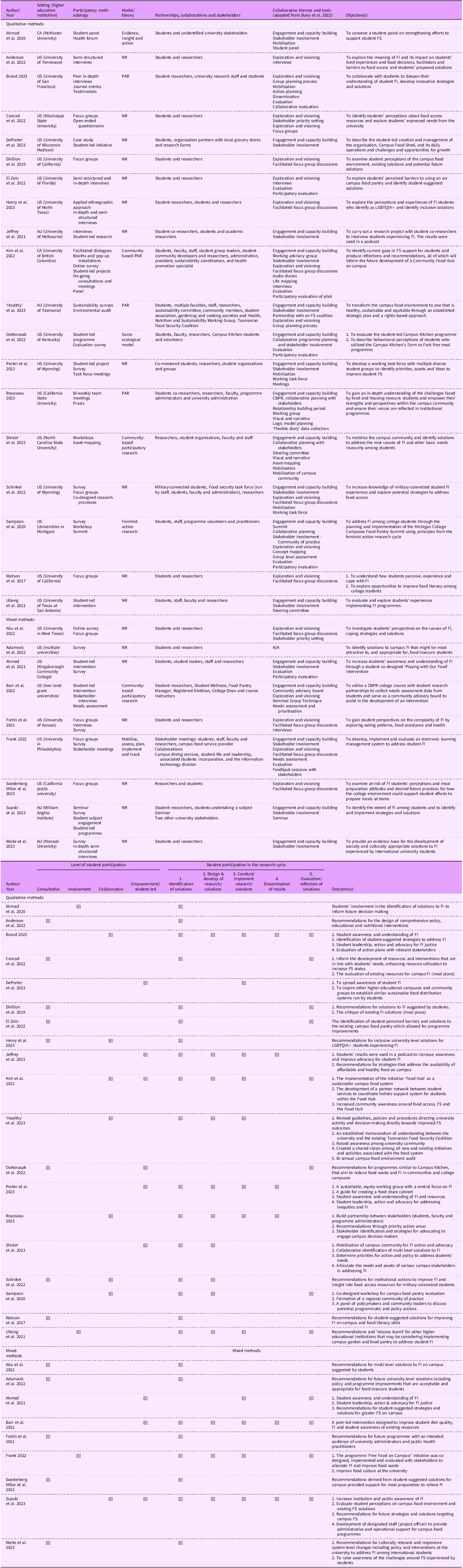

The type and degree of student participation varied across the studies which is detailed in Table 5. Twenty-three of the twenty-eight studies explicitly mentioned the number of students involved, which ranged from 2 to 339 students. Most studies had between eleven and fifty participants (n 12, 42 %).

Table 5. Characteristics of included studies for student participation in food security research

CA, Canada; FI, food insecurity; FS, food security; NR, not reported; PAR: participatory action research; LGBTQIA+, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex; AU, Australia.

The objectives of all studies were similar in that the purpose of student participation was to identify and utilise students’ experiences, perspectives and ideas for solutions. An additional reason for student involvement was that the study involved student-led interventions and programmes (n 4). In twelve of the twenty-eight studies, students participated in the research process for the purpose of evaluating or reflecting upon existing solutions to student FI (n 12).

There were three distinct student subpopulations explicitly involved in three studies: international students(Reference Waite, Gallo Cordoba and Walsh43), military-connected students(Reference Schinkel, Budowle and Porter44) and students identifying as LGBTQIA+(Reference Henry, Ellis and Ellis45). For demographic characteristics, 39 % of the studies had a majority female (n 11) and 54 % undergraduate students (n 15) reported. Many studies provided evidence of student participation; however, there was still a significant amount of unreported data on gender (46 %), education level (35 %) and enrolment status (71 %).

Ten studies specified a participatory model or framework in the study design. This included participatory action research (n 3), community-based participatory research (n 3), feminist action research (n 1), socio-ecological model (sem) (n 1), ‘Mobilize, Assess, Plan, Implement and Track’ (MAP-IT) framework (n 1) and an ‘Evidence, Insight, Action’ framework (n 1).

For the level of participation, seventeen out of twenty-eight studies had involved students in more than one step of the research cycle. However, only three studies reported student participation across all five steps, indicating continuous engagement. Evidence of co-design and co-development was found in thirteen of the twenty-eight studies. There were six studies that had evidence of student participation from the first step: identification of a solution, to the fourth step: the dissemination of results.

Regarding the four participation levels, the most common was the minimum, consultative, identified in thirteen of twenty-eight studies. The highest level of participation, student empowerment, was identified in nine of twenty-eight studies, with three of these studies specifically noting student-led research.

Three of the twenty-eight studies had the second lowest level of participation which was involvement, and eight of twenty-eight studies had the second highest level of participation which was collaborative. There were five studies that had more than one level of participation recorded. This was because the study was led by student researchers who had conducted research processes on other students, for instance, student-led interviews or focus groups. For conventional participatory research methods, studies included utilised surveys (n 13), focus groups (n 8) and individual interviews (n 6) to collect student’s experiences, opinions and ideas towards solutions.

Stakeholders, partnerships and collaborations

The types of partnerships, collaborations and stakeholders also varied across studies. Ten of the twenty-eight studies included only students and researchers in the research cycle. Whereas most of the studies had evidence of collaboration and partnership among multiple stakeholders (n 18, 64 %). These stakeholders included student co-researchers (n 7), student organisations and groups (n 3), university staff including administrators and faculty (n 8), sustainability coordinators (n 2) and food programmes staff and volunteers (n 3). Three studies also showed evidence of engagement with clinical and public health staff including practitioners(Reference Sampson, Price and Reppond46), health promotion specialists(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47) and registered dietitians(Reference Barr and McNamara48). As shown in Table 3, some studies had evidence of engagement with stakeholders through specific organisational structures or groups such task forces(Reference Schinkel, Budowle and Porter44,Reference Porter, Grimm and Budowle49) , coalitions(50,Reference Brand51) , group seminars(Reference Supski, McMillin and Guest52), panels(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Ahmad, Choi and Filbey53,Reference Ahmed, Ilieva and Clarke54) , working advisory groups(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Barr and McNamara48,Reference Rousseau55) and steering committees(Reference Shisler, Oceguera and Hardison-Moody56,Reference Ullevig, Vasquez and Ratcliffe57) .

Outcomes

The most common outcomes were recommendations for strategies including policy and programme development (n 23), evaluation of existing programmes (n 5), increased awareness of student FI among the university community (n 11) and enhancing advocacy efforts (n 5). For studies with higher levels of student participation, particularly, collaboration, empowerment or student-led, there was often more than one outcome reported. Such outcomes included increased student awareness and understanding of FI(Reference Waite, Gallo Cordoba and Walsh43,Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47–Reference Supski, McMillin and Guest52,Reference Ahmed, Ilieva and Clarke54,Reference DePorter, Moss and Puc58,Reference Jeffrey, Dyson and Scrinis59) , student leadership, action and advocacy for food justice(Reference Porter, Grimm and Budowle49,Reference Brand51,Reference Ahmed, Ilieva and Clarke54) , the development of campaigns(50,Reference Supski, McMillin and Guest52,Reference Ahmed, Ilieva and Clarke54) , working groups, partner networks and coalitions(Reference Schinkel, Budowle and Porter44,Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Porter, Grimm and Budowle49,50) .

Barriers to student participation

Understanding the barriers to student participation is important for improving participatory methodologies for future research related to food security. Barriers to student participation were identified in nineteen of the twenty-eight studies. One of the barriers was related to social desirability bias linked to the stigma of being identified as food insecure, which affected participation in the research(Reference El Zein, Vilaro and Shelnutt60). Conformity bias was also noted particularly in focus group settings, where students may have refrained from sharing unpopular individual experiences, resulting in potentially homogenised suggestions on solutions(Reference Watson, Malan and Glik61,Reference Conrad, Tolar-Peterson and Gardner62) . Both types of bias hindered open communication, leading to lower participation rates, less meaningful participation and results that were potentially not representative of the actual experiences and needs of food-insecure students(Reference El Zein, Vilaro and Shelnutt60–Reference Conrad, Tolar-Peterson and Gardner62). Co-researcher students in one study also felt uncomfortable seeking out food-insecure students for interviews due to fear of further stigmatising their food-insecure peers(Reference Brand51). Although 43 % of studies (n 12) screened students for FI, one study avoided this process to specifically reduce the risk of stigmatising student participants(Reference Shisler, Oceguera and Hardison-Moody56).

Student-led research studies (n 3) noted that barriers to sustained engagement and project task completion were most likely due to a lack of student availability, busy schedules, high student turnover rates and long-term communication issues(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Barr and McNamara48,Reference Ullevig, Vasquez and Ratcliffe57) . There were also challenges to engaging in stakeholder collaboration between and within multiple campus stakeholders and student groups to be involved in implementing food security initiatives(Reference Ahmad, Choi and Filbey53).

Four studies reported limitations of poor representation of diverse student groups including minority groups whose experiences of food security may be compounded by other experiences of stigma and discrimination(Reference Abu, Tavarez and Oldewage-Theron31,Reference Henry, Ellis and Ellis45,Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Barr and McNamara48,Reference Shisler, Oceguera and Hardison-Moody56) . In Kim et al.’s study (2022), the project outreach efforts failed to reach diverse student groups due to capacity and time constraints(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47). Additionally, the limited representation of student groups in the needs assessment further affected the final determination of a campus-wide programme in Barr’s study (2023)(Reference Barr and McNamara48).

Strategies and solutions

Seven key categories emerged for strategies and solutions for addressing FI. These include: (1) policy and institutional support; (2) community engagement, strategic partnerships and coalitions; (3) advocacy and awareness; (4) activities and initiatives for engagement with students; (5) student skill and knowledge development; (6) programmes and (7) campus food environment improvements. These are displayed in detail in Table 6.

Table 6. Co-designed strategies for higher education institutions to address student food insecurity

FI, food security; FS, food security, PAR, participatory action research; LGBTQIA+, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex.

Discussion

This was the first review to explore evidence of co-design approaches in research addressing FI in the higher education setting. Overall, the findings suggest that methodologies incorporating these approaches can promote more meaningful participation with students who may be affected by FI which can lead to more unique and inclusive solutions.

This review explored the field of FI research in higher education settings, noting that 95 % of articles were published in the last 4 years. This surge of recent publications indicates a growing recognition of the issue and increased research focus on understanding and addressing FI among students. All included studies were from higher-income countries, predominantly conducted in the United States, where the prominence of campus food security research may be linked with the country’s mainstream food movements supporting food justice and sovereignty(Reference Clendenning, Dressler and Richards63). Food justice movements emphasise the need for more just food systems, where healthy, sustainable and equitable food is recognised as a human right, while also addressing the root causes and structural inequities that contribute to FI(Reference Murray, Gale and Adams64). Some advancements in food security research and policy in the United States have led to developments in organisations such as Swipe Out Hunger and the federal food access programme known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program(65,66) .

The degree of student participation in research and decision-making processes varied across studies included in the review. Results found students were mostly engaged in the formative stages of the research cycle involving the identification of potential solutions and need assessments. There was also variation in the level of student participation across the studies. The most commonly reported level of student participation was consultative, which was the lowest level of participation. Consultative participation often involves traditional qualitative research methods such as focus groups, interviews and surveys where students participate in the research to provide their opinions, experiences and feedback on potential strategies and solutions(40). Conversely, 32 % of studies had students engaged in the highest level whereas 11 % of these were student-led.

Nevertheless, evidence of co-design and co-development was present in 46 % of the studies where 11 % had evidence of student participation in all five steps of the research cycle. Continuous engagement with stakeholders throughout each research cycle phase can characterise co-designing and co-producing processes, constituting co-creation(Reference Vargas, Whelan and Brimblecombe67). Co-creation which involves active engagement at all stages of the research cycle, promotes continued dialogue, power-sharing and reciprocity between stakeholders(Reference Vargas, Whelan and Brimblecombe67). Although, as revealed in this review, there are some challenges associated with achieving a high level of collaboration. Continuous engagement with students can be difficult to achieve because of a lack of student availability due to busy schedules, high student turnover rates and long-term communication issues. Some collaborative and student-led studies were found to utilise alternative visual and narrative methods for data collection, analysis and interpretation including journal entries, concept mapping and digital storytelling. These methods can adopt strong collaboration with students by aligning with their interests and empowering them to actively engage in the research process(Reference Duea, Zimmerman and Vaughn32,Reference Gubrium, Harper and Otañez68) .

The utilisation of participatory research frameworks can guide researchers in co-creating interventions and strategies(Reference Greenhalgh, Jackson and Shaw69). There were ten studies in this review (36 %) that utilised some form of participatory framework. These frameworks were often incorporated into course curriculums and student research projects where students were trained to use them to perform research on their food-insecure peers. These methodologies can provide the basis for effective engagement but can also facilitate community capacity building(Reference Duea, Zimmerman and Vaughn32). Participatory research frameworks can facilitate individual’s understanding of the problem and its manifestations in their communities, whilst also providing opportunities for skill and knowledge development to create new solutions(Reference Olabisi, Sidibé and Assan70). Community engagement and agency are essential for food justice, decision-making and transformative food system changes(Reference Murray, Gale and Adams64). This involvement in research processes can also have lasting impacts on community members including empowerment(Reference Röger-Offergeld, Kurfer and Brandl-Bredenbeck71). Brand (2023) highlights how participatory action research motivated students to pursue food justice beyond the scope of the study, creating a sustained interest in addressing social justice issues(Reference Brand51). Similar outcomes were observed in a study utilising the community-based participatory research methodology, where student involvement in the Food Dignity Project led to improved values and attitudes towards the food system and enhanced students’ ability to effect change in the local community(Reference Swords, Frith and Lapp72).

Developing strong partnerships was found to be critical for long-term collaboration and the development of sustainable solutions(Reference Kim, Dong and Gowda47,Reference Barr and McNamara48,Reference Rousseau55) . Rousseau’s study(Reference Rousseau55) included a 4-month relationship-building period where students could collectively express their experiences in confidence during regular meetings, leading to a sense of mutual support and empowerment. Unlike traditional research methods where participation is often one-off, effective co-design can prioritise relationship and trust-building, particularly when working with marginalised communities and addressing sensitive topics(Reference Benz, Scott-Jeffs and McKercher73,Reference Woolf, Zimmerman and Haley74) . Partnerships with students and university stakeholders were often solidified through working groups, task forces and committees which could provide an ongoing communication channel and representation of key stakeholders. Creating these partnerships requires the identification of relevant stakeholders, creating a shared vision and developing a set of values and goals(Reference Roussos and Fawcett75). Findings from this study show that this process can be facilitated through exploration and vision strategies such as group planning processes, stakeholder priority setting, asset mapping and comprehensive needs assessments(Reference Duea, Zimmerman and Vaughn32). At the University of California, Fanshel and Iles (2021) utilised foodscape mapping with student collaborators, a strategy which led to the development of advocacy projects and changes in the campus food system policy(Reference Fanshel and Iles76). Furthermore, collaborations across academic faculties and disciplines including nutrition and dietetics, public health, agricultural, environmental and social sciences are key to ensuring a comprehensive approach to supporting health and well-being, sustainability and the campus food environment. One key multidisciplinary strategy involved engaging media and creative arts students in promoting and advertising FS programmes, resources and information developed by students and staff from health and nutrition-related facilities(50,Reference Ullevig, Vasquez and Ratcliffe57) .

Successful coalitions form relationships between internal (i.e. relationships between students and researchers) and external entities(Reference Foster-Fishman, Berkowitz and Lounsbury77). The review found evidence of partnerships with local expertise such as established food security coalitions, agricultural groups, local community members, non-profit organisations and other universities to be beneficial in sharing knowledge and increasing capacity for solutions. Community-university partnerships have proven valuable in driving social change within food systems, building community skills and forming a community of practices(Reference Nelson and Dodd78).

While collaborative efforts were found to be important, the power to enable systemic changes lies with institutional leaders, who can allocate resources and infrastructure and enforce policies and procedures that shape and support student food security(Reference Savoie-Roskos, Hood and Hagedorn-Hatfield30). Several strategies were identified at a policy and institutional support level. Some of these include regular monitoring of FI risk among students, educating institution staff and incorporating comprehensive FS policies into existing health and well-being and food service procurement policies. Some of the studies found student suggestions around having trained and dedicated university staff members who could lead initiatives, drive policy changes for the campus food environment and support students experiencing FI. Findings from this review also suggest that student-led research may have a greater impact on institutional governance by enhancing the capacity of student co-researchers to engage in advocacy processes. Students involved in disseminating results through presentations, workshops and meetings with university stakeholders could help leverage the social justice issue to the forefront of the institution’s agenda.

Recent qualitative work has shown how students are often unaware of their own food security status and the resources and support available at their institution(Reference Lemp, Lanier and Wodika79,Reference Hagedorn-Hatfield, Hood and Hege80) . Consequently, they may lack an understanding of how FI manifests and the wide-ranging implications. This lack of awareness may explain why studies at the consultative level of student participation with limited representation of food-insecure students, generally identified existing, surface-level solutions to address FI. Examples of these solutions found in some of these studies include implementing campus food pantries and distributing grocery vouchers and emergency food aid. Despite the importance of these solutions, they are typically short-term, addressing immediate needs rather than the root causes of FI(Reference Seivwright, Callis and Flatau81). This highlights the strength of collaborative research methods which can provide opportunities for mutual learning and encourage participants to think critically about the problem, how it affects individuals and how to facilitate effective, systemic changes(Reference Brand51). An additional benefit is the increased awareness and normalisation of FI in the university community, which has also been outlined as a key recommendation for creating more supportive campus environments(Reference Savoie-Roskos, Hood and Hagedorn-Hatfield30).

One of the barriers to student participation was ensuring a diverse representation. This is particularly challenging given the complexity of food security, which is often intertwined with various other inequities among students. There was a high representation of undergraduate students involved (54 % of the studies), aligning with recent evidence which indicates undergraduate students were at least three and a half times more likely to be food insecure than postgraduate students(Reference Whatnall, Hutchesson and Patterson1). There was a focus on some vulnerable groups with increased risk of FI in this review such as LGBTQIA+, military-connected students and international students. Empirical research has also identified other at-risk groups including housing-insecure(Reference Silva, Kleinert and Sheppard19), disabled(Reference Stott, Taetzsch and Morrell82), parents(Reference Maroto, Snelling and Linck83) and first-generation students(Reference Tanner, Loofbourrow and Chodur84). Participatory research methodologies with marginalised communities can promote relevant, appropriate and inclusive strategies and solutions(Reference Cornish, Breton and Moreno-Tabarez85). Therefore, future student FI research should adopt similar collaborative methodologies to address the needs of other student groups at risk of FI.

Participatory research methods offer an approach to amplifying the voices of vulnerable and marginalised groups in higher education settings, particularly for FI(Reference Bergold and Thomas86). These methods can create supportive environments for developing non-hierarchical relationships and effective collaboration between researchers and participants(Reference Bergold and Thomas86). Studies in this review with higher levels of student participation, for instance, student-led research, often reported less demographic and FI screening. This likely stems from the stigma associated with FI in higher education environments, where explicit screening for FI and demographic characteristics may inadvertently cause students to feel inferior or further stigmatised, especially in group settings like focus group discussions and workshops. To address this challenge while maintaining diverse representation, one effective strategy that was identified was to integrate participatory research projects, campaigns and task forces with existing student organisations and societies that represent diverse student populations. This approach allows for engagement with diverse groups, potentially reducing stigma whilst capturing a range of experiences and perspectives on campus FI.

This scoping review is not without limitations. Firstly, although this review aimed to explore literature from all countries, findings were exclusively from higher-income nations, predominantly the United States, which limits the generalisability of the findings to other regions particularly, lower- and middle-income countries. Although most studies focused on universities, the broad inclusion for any type of higher education institution, such as community colleges, may also limit the generalisability of the findings to unique institutions which often differ between countries. Given the early nature of this research area, the review sought to capture all potential literature by including three academic databases and two grey literature sources. However, since it involves the higher educational setting, the review is unable to capture any internal institutional efforts that are not published or available online. A potential strategy to address this limitation would be to consult with relevant university stakeholders, though this was not feasible within the scope and capacity of this review. We also acknowledge that a more directed content analysis could have been applied to support deductive coding and improve consistency, thereby reducing potential bias in the categorisation process. Future research could consider adopting a more systematic coding framework when exploring solutions to FI in higher education. Furthermore, scoping reviews have innate limitations associated with having a broader scope, meaning that included studies had some degree of heterogeneity in terms of study design and methodologies. This meant that identifying similarities between studies was often challenging. Despite the use of broad search terms and a systemic search strategy, there is a possibility some studies were also missed in this review.

The findings of this review reinforce how integrating co-design research methodologies can ensure that strategies are grounded in communities’ experiences and needs, in this case, for addressing student FI in the higher education setting. This review uncovered a variety of strategies that researchers, students and university stakeholders can adopt in their respective institutions. Co-design approaches can bring about additional benefits such as enhanced student capacity, improved advocacy efforts, long-term partnerships and a deeper understanding of stakeholders’ priorities and needs. Empowering students to be actively involved in the research and decision-making processes concerning their food environments is critical for achieving equitable, healthy outcomes and long-term systemic changes. The review also identified several barriers associated with utilising such methodologies in higher education settings. As research in this field progresses, future studies should prioritise collaborative co-design approaches when exploring solutions to FI and similar social justice issues affecting students.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980025000485

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Mr Jeremy Cullis, the clinician librarian at Macquarie University, for his assistance with planning the search strategy for database searches.

Authorship

T.S. is the first and corresponding author contributing to the conceptualisation, design, planning, preparation of the study and completion of the original draft. S.M. and M.J.W. contributed to the conceptualisation and methodology. N.F. and G.G. contributed to the study selection and assisted in data extraction processes. S.M., M.J.W., N.F., G.G., A.J.B. and S.P. provided feedback and editorial support.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

Ethical approval was not required because this study retrieved and synthesised data from already published studies.