INTRODUCTION

Studies on media development emphasize that the media can have a liberalizing effect on political systems by serving as a watchdog, but that state-controlled media props up authoritarian rule by functioning as a government mouthpiece. This study examines the relationship between media exposure and regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes where mass media is not continuously or entirely controlled but where the regime maintains the capability of exercising control. This variation in media control in hybrid regimes allows us to explore the conditions under which media have subversive or bolstering effects on competitive authoritarian regimes.

To explore the impact of media exposure on regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes empirically, we examine South Korea's authoritarian period. South Korea experienced varying degrees of authoritarian rule from the 1960s to the 1980s. South Korea also faced severe state censorship and control throughout the twentieth century, especially under Park Chung Hee (1961–1979) and Chun Doo Hwan (1980–1987).Footnote 1 During the first decade of Park's rule (1961–1972), often characterized as “soft authoritarianism” or “democratic interlude” (Im Reference Im, Kim and Vogel2011, 234), a series of acts intended to repress news agencies and broadcasting stations took place that helped to silence the critical media and laid the groundwork for Park's absolute dictatorship, known as the Yushin regime (1972–1979). Yet during this “dark age of democracy” (Lee Reference Lee2010; Lee Reference Lee2005; Yi Reference Yi2011), a “sustained social movement for democracy,” including the free press movement, emerged in resistance to the Yushin system (Chang Reference Chang2015, 4). These diverging impacts of Park's suppression of mass media on the expression of citizens' views and support for the regime thus remain unclear. With the lack of empirical research on the role and effects of media in South Korea, these mixed outcomes call into question the relationship between media exposure and regime support in authoritarian regimes.

Despite a plethora of anecdotal evidence on the Park regime's media control, this study is the first attempt to our knowledge to empirically explore when and how media exposure affected public support for the authoritarian incumbent. This study specifically focuses on Park's pre-Yushin regime, the competitive authoritarian period in which Park contested in competitive elections until the promulgation of the Yushi n Constitution in 1972 that abolished direct presidential elections. During this period, government's control over both print media and broadcast media became more severe beginning in the mid-1960s.

We first conduct a content analysis of newspapers for more than 400 articles published in the presidential elections years to show that tighter control of media in the mid- to late-1960s is indeed associated with articles taking a more pro-regime stance. Subsequently, we carry out a series of regression analyses using county-level data on newspaper circulation and election results as well as radio signal strength, which was estimated using geographic information system (GIS) and the Irregular Terrain Model (Hufford Reference Hufford2002) based on data on radio transmitters and spatial boundaries of election districts.

The content analysis of newspapers reveals that the government's tighter control of the media in the late 1960s is associated with media coverage that favors the authoritarian incumbent, Park Chung Hee. With greater state control of news agencies, there was less coverage on the opposition candidates and fewer articles containing negative information or criticism of Park.

Corroborating our findings from the content analysis, we find that when government control of the media was weaker in the early 1960s, citizens' greater exposure to media was correlated with more opposition to the regime. However, we also find that when the media was severely controlled in the late 1960s, the correlation between media exposure and opposition disappears.

Our work advances the growing literature on competitive authoritarianism by demonstrating that the effect of media exposure in competitive authoritarian regimes is conditional on the degree to which governments allow media freedom. When regimes allow more free and independent media, media exposure has a positive effect on regime opposition. In contrast, media exposure bolsters competitive authoritarianism when there is less free media. We also add to the discussion of repression and mobilization in authoritarian regimes by showing that media control, as a form of repression, can silence opposition.

This article proceeds as follows: we first discuss the existing literature on the political effects of media development and then provide background information on Park's pre-Yushin regime and temporal patterns of media control. Subsequently we lay out our empirical hypotheses and describe the data and empirical strategy used to test the hypotheses. Lastly, we report our results and conclude.

EXISTING LITERATURE AND THE ARGUMENT

The conventional wisdom from modernization theory holds that the development of mass media leads to positive social and political changes (Lerner Reference Lerner1964). Media development is often linked to increase in freedom of expression, which is one of the key components of a liberal democracy. Scholars have used freedom of the press (from Freedom House and Polity Project) as one indicator of the extent to which a political system is liberalized. Indeed, free media—domestic and international—played a critical role in the diffusion of democratic ideas and social movements (Howard et al. Reference Howard, Duffy, Freelon, Hussain, Mari and Mazaid2011; Snow, Vliegenthart, and Corrigall-Brown Reference Snow, Vliegenthart and Corrigall-Brown2007; Strang and Soule Reference Strang and Soule1998). Television reporting was said to have facilitated public protest in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, contributing to the breakdown of the Soviet Union (Huntington Reference Huntington, Diamond and Plattner1996). Existing literature also suggests that foreign media played a key role in the 1989 East German revolution, by altering perceptions of political opportunity (e.g., Grix Reference Grix2000; Hirschman Reference Hirschman1993; Jarausch Reference Jarausch1994; Kuran Reference Kuran1991; Opp and Gern Reference Opp and Gern1993).Footnote 2 Western broadcast's coverage of domestic politics of democratic nations, in the long run, installed pro-democratic values and undermined public support for communism and authoritarianism (Rustow Reference Rustow1990; Diamond Reference Diamond1993; Dalton Reference Dalton1994; Rohrschneider Reference Rohrschneider1994; Bennett Reference Bennett and O'Neil1998; Sükösd Reference Sükösd, Gunther and Mughan2000). Criticisms voiced by mass media during regime change contributed to the erosion of regime legitimacy and propelled democratization in many third wave democracies (Lawson Reference Lawson2002; Olukotun Reference Olukotun2002; Rawnsley and Rawnsley Reference Rawnsley and Rawnsley1998).

In advanced and consolidating democracies, the development of mass media has a liberalizing, if not democratizing, effect on political systems because of the media's watchdog role in monitoring the conduct of government officials. Mass media provide information to voters to electorally punish politicians for “bad” behavior (e.g., being suspected of corruption or being captive to special interests). For instance, Chang, Golden, and Hill (Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010) find that Italian legislators suspected of wrongdoing are punished by voters only when the press begins to report on political corruption. Similarly, Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé, and Sorribas-Navarro (Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012) show that incumbent mayors in Spain are punished more for involvement in a scandal when the press devotes a large amount of coverage to the scandal. Fergusson (Reference Fergusson2014) finds that concentration of special interest contributions to incumbent senators in the United States is punished by voters living in areas where candidates receive more coverage from their local television stations. Larreguy, Marshall, and Snyder (Reference Larreguy, Marshall and Snyder2014) also show that voters in Mexico punish the party of corrupt mayors only in areas covered by local media stations.

In contrast, media exposure does not cleanly translate into political behavior in authoritarian regimes because authoritarian governments vary in the degree and ways in which they exercise control over media. Some authoritarian leaders attempt to attenuate the potentially destabilizing effects of the media by spending significant financial and administrative resources to quell their influences. For instance, the Fujimori regime paid the largest amounts of bribe money to the news media (among politicians, judges, and the news media) in maintaining its rule (McMillan and Zoido Reference McMillan and Zoido2004). Others such as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime used the press media in propagandizing the legal system as overly positive (Stockmann and Gallagher Reference Stockmann and Gallagher2011) and exercised its bureaucratic capacity to censor information on the Internet that may spur collective action (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013). This impetus to control the media is especially strong in competitive authoritarian regimes where there are constitutional channels through which opposition groups can compete for executive power in a meaningful way (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, Reference Levitsky and Way2010). As noted by Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010), leaders in competitive authoritarian regimes—whose authoritarian survival depends on votes—often control state-owned as well as private-owned media to create an uneven playing field and sway elections in favor of the ruling party.

While more access to free media can have subversive effects in authoritarian regimes, government-controlled media can bolster authoritarian rule. Recent studies suggest that media exposure can increase popular support for authoritarian regimes when the media is highly controlled. Enikolopov, Petrova, and Zhuravskaya (Reference Enikolopov, Petrova and Zhuravskaya2011) find that Kremlin's media control of state-owned television played a crucial role in Putin's electoral victory in 2000, despite his low popularity rating (below two percent) the previous year. Similarly, Adena et al. (Reference Adena, Enikolopov, Petrova, Santarosa and Zhuravskaya2015) show that while access to radio was negatively correlated with the Nazi vote before the Nazis controlled the media, it helped the Nazis electorally when they used radio as their propaganda tool.

Building on these studies, this study explores the impact of mass media on authoritarian incumbent support by distinguishing between media exposure and media control. We argue that the effect of exposure to media is conditional, especially in competitive authoritarian regimes. While exposure to different views and information within media can impact voters' political knowledge, the degree of such access to contending views will depend on the extent to which governments control the media. In fully authoritarian regimes, the state exercises extensive control over mass media. Autocrats exploit mass media to propagate their ideology and to enhance popular support for their regimes. Simultaneously, they monitor and control mass media to preempt it from becoming a focal point for political mobilization that could undermine the regime's legitimacy. However, in competitive authoritarian regimes, where formal democratic institutions such as elections, political parties, and legislature are the primary means of gaining power, independent media exist, and civic and opposition groups operate above ground (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010). The media are not entirely controlled at all times, although the regime maintains the capability of exercising control, which generates variance in media freedom across time and space. This variance in media exposure under competitive authoritarianism, in turn, can have divergent effects on regime support.

Mass media in hybrid regimes could theoretically have a subversive effect by serving as a watchdog, as the media do in other democratic regimes that hold regular, competitive elections. However, mass media could also bolster hybrid regimes by functioning as a mouthpiece of the government as they do, as in fully authoritarian regimes. Media exposure may have these contradictory effects in different competitive authoritarian regimes. Whether the development of media is harmful or beneficial for the regime is thus heavily shaped by the ways in which the government exercises its control over the media.

CONTEXT

We examine the relationships between media exposure, media control, and regime support in South Korea under Park Chung Hee (1961–1979). Specifically, we study the first decade of Park's rule (pre-Yushin regime; 1961–1972), which has been characterized as “competitively authoritarian” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010). Three direct presidential elections were held, in 1963, 1967, and 1971. Park won the 1963 and 1967 presidential elections by narrow margins and amended the constitution in 1969 to allow three terms in office. Multiparty elections in these years were competitive, and opposition candidates were able to formally contest, with no legal controls that prevented them from running public campaigns. On the other hand, civil liberties were violated, in the sense that media, opposition politicians, and activists were subject to harassment, arrest, and violent attacks.Footnote 3 In 1972 Park consolidated his authoritarian grip on power and abolished presidential elections through the inauguration of the Yushin (Revitalization) Constitution, which endowed him with near-absolute power as a “legal dictatorship.”Footnote 4

The media industry was relatively young and underdeveloped when Park Chung Hee came to power in 1961. Initially the Park government stipulated laws and legal restrictions to control the media industry. State censorship increased in the late 1960s, as a preemptive strategy in preparation for the promulgation of the Yushin Constitution. Media control strategy also became more blatant and coercive over time. This temporal variation in the extent of media control under Park during the competitive authoritarian period provides a suitable environment to explore the effect of access to mass media on regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes. We now provide descriptive information on when and how Park's government controlled the press and broadcast media leading up to the installment of the Yushin Constitution as well as how the media industry responded to such changes.

Press Media

From August 1960 to May 1961, immediately preceding Park's coup-born regime, there was a short-lived parliamentary government led by a figurehead president (Yun Bo Sŏn) and a prime minister (Chang Myŏn). Under Chang's weak government—marred by poverty, political instability, and social stagnation—the media was left uncontrolled, and the number of periodicals proliferated at an unprecedented rate.Footnote 5 Upon taking power in 1961, Park believed that the “free and chaotic press” was at least partially to blame the “social chaos” of the Chang regime (Youm Reference Youm1996, 54). In response, under his initial period of martial law (1961–1962) he introduced censorship measures that aimed to weaken overtly incendiary periodicals and news outlets. The Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (SCNR), a temporary governing body of the coup-born regime, announced Decrees No. 1 and No. 4, prohibiting the press and media from “agitating, distorting, exaggerating, or criticizing” the “revolution” (i.e., the coup). Subsequently, the SCNR announced Decree No. 11, which intended to “purify” the media by purging “pseudo-journalists and pseudo-media agencies” from the previous regime. Through Decree No. 11, the SCNR imposed strict facility standards of newspapers and news services requiring that newspapers be published only by those with complete printing facilities for newspaper production and that news services be limited to those with complete wire service facilities for transmission and reception. This resulted in a significant reduction in the number of newspapers and news agencies.Footnote 6

Nevertheless, with the lifting of martial law in December 1962, the press recovered from two years of stagnation and established a critical stance towards the regime. For instance, in 1962 Park initially took back his promise to transfer power to a democratically elected civilian government and declared that military rule would be extended for another four years. Major newspapers including Chosun, Dong-A, and Kyunghyang immediately displayed their opposition to Park's statement by not including any editorial in their editions. In response, as originally promised, Park ran as a civilian candidate of the Democratic Republican Party (DRP) in the 1963 presidential elections and won by a narrow margin of 1.5 percent.

Alongside Park's tenuous popularity, his perception of threat shifted to popular unrest.Footnote 7 Mass student protests erupted in 1964 against Park's diplomatic talks to normalize relations with Japan, which had colonized Korea from 1910 to 1945.Footnote 8 Park's normalization talks with Japan met vociferous domestic opposition from opposition politicians, college students, and the media, who criticized the talks as a “humiliating diplomacy.” The media provided extensive coverage of student demonstrations on Korea–Japan Treaty talks, including the Park regime's crackdown on these protests.

Due to the severity of the protests, Park declared martial law in June 1964 and imposed new restrictions on the media with the intention of limiting the ability of the press to incite or prolong popular unrest. In August, 1964, the National Assembly passed the Media Ethics Committee Law (Ŏllon yulli wiwŏnhoepŏp) without the presence of any opposition party members. The law aimed at “enhancing the effectiveness of self-regulation by the press and broadcasting,” further limited the autonomy of the press, and was strongly criticized and opposed by the press and the public.Footnote 9 Five newspapers with substantial readership—Chosun, Daehan, Dong-A, Kyunghyang, and Maeil—explicitly or implicitly defied this. The government retaliated by canceling the subscriptions of these five newspapers in all government organizations and households of public servants as well as excluding them from receiving any special benefits (e.g., tax breaks and free loans).

State censorship further increased in the late 1960s as Park was preparing to amend the constitution to allow a third presidential limit. After having experienced the press–government confrontation in 1964, Park looked for an alternative way to control the media without having to enact media-related laws, and he issued a special order to create a media-control unit within the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) (Kim Reference Kim2009, 180). Although the KCIA was only allowed to investigate cases involving the violation of the Anti-Communist Law, they arrested and investigated any journalists or editors responsible for articles that criticized the government (NIS 2007, 43). The KCIA agents were also stationed at central offices of the major newspapers to directly monitor and control their activities. They analyzed newspaper articles in detail, categorizing them according to the targets or issues that were being criticized, as well as according to where the article was placed in the newspaper, suggesting that the KCIA paid keen attention to the content of these newspapers and their stances towards the regime.Footnote 10

The best-known instance of media repression during this period of increased state censorship is the enforced sale of the Kyunghyang Daily,Footnote 11 which had been known to be critical of and resistant to the government ever since its founding in 1966.Footnote 12 The main reason for the sale was its failure to repay a debt of 46 million won. However, given the fact that the majority of newspapers at that time ran operating deficits, it was evident that the government wanted to control the management of Kyunghyang that had been critical of the regime and its policies. The owner of Kyunghyang was arrested in 1965 for violating the Anti-Communist Law, and the paper was sold to Kia Industry, the sole government-supported bidder in the auction in 1966. With the management change, Kyunghyang immediately became a pro-government newspaper. The Korean media—in contrast to their collective resistance in 1964—remained silent regarding the enforced sale of Kyunghyang.

The media's subordination to government control became more apparent in the run-up to the 1967 election, when the media refused to support the opposition party's effort in advocating for press freedom. The major opposition party, the New Democratic Party (NDP; Shinmindang), led a campaign for a free press, which included sending letters to international organizations such as the International Press Institute and the United Nations Commission for the Unification and Rehabilitation of Korea. When the NDP asked the press for their support, the newspapers not only turned down the request, but also criticized the opposition by questioning the political motivation of the campaign (Song et al. Reference Song, Choi, Park, Yoon, Son and Kang2000, 294–295).

By the end of the 1960s, the papers that unequivocally resisted the government in 1964 were completely subordinate to government control. Kyunghyang was sold to a government-supported company in 1966. Chosun Daily was co-opted by the government in 1967, after receiving four million US dollars of foreign loans from Japan to build a tourist hotel in Seoul. Dong-A, the last remaining resistant newspaper agency, finally gave in when the government arrested its several senior journalists for violating the Anti-Communist Law in 1968. The Korean media again took no action against government's attack on Dong-A or on press-freedom issues in general,Footnote 13 and this marked the beginning of the “dark age” of the Korean press, which lasted until democratization in 1987.Footnote 14

Broadcast Media

The Park regime also used broadcast media to propagandize and legitimize the coup-born regime.Footnote 15 Throughout Park's rule, the broadcast media were more consistently susceptible to government control than the press media. Unlike the press media, the development of commercial broadcast media was new, and was considered to be a part of the state-led modernization drive that Park considered to be a national top priority. Even the commercial broadcasters were not exempt from government control, but as long as they shared the economic and political interests of the government, Park was committed to maintaining them in operation (Kwak Reference Kwak2012, 14).

The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS), a state-owned broadcaster, lacked autonomy from the state, presenting few views that were different from those of the government. MBC (Munhwa Broadcasting Company, later renamed as Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation), although a private broadcaster, was essentially owned and managed by the ruling elite. From 1962, MBC was operated by the 5.16 Foundation,Footnote 16 which was established in 1962 by incorporating Kim Ji-Tae's Bu-il Scholarship Foundation. Kim Ji-Tae, a journalist as well as the president of Pusan MBC and Pusan Daily, was arrested in 1961 for “illegally amassing wealth” and released the following year on the condition that he “donate” his scholarship foundation to the state.

By the early 1970s both KBS and MBC essentially functioned as mouthpieces of the government, by explicitly supporting Park during the 1971 presidential elections and promoting the Yushin system in 1972. All broadcasting companies set up a separate division to provide reports and information related to the New Village Movement (Saemaŭl undong)—Park's key political initiative to modernize rural South Korean economy during the Yushin period. KBS was at the forefront, with 30 radio programs and 18 television programs (approximately three to five programs per day) broadcasted on the movement (Kim Reference Kim2007).

RESEARCH DESIGN

We first conduct a content analysis of newspaper articles in the run-up to the presidential elections in 1963 and 1967, to systematically examine whether there are in fact changes in newspaper coverage and stances towards the authoritarian incumbent, Park Chung Hee. A content analysis of newspapers allows us to observe the changes in the coverage and information that voters receive regarding the presidential candidates and their campaigns, which would in turn impact their voting decisions. To validate the historical narrative on the temporal patterns of Park's media control during his first decade of rule, we explore the differences in news coverage between the early and later years of Park's pre-Yushin regime. We expect to find the proportion of newspaer articles covering the oppositon candidates as well as articles citicizing Park to decrease in the election year following tighter media control.

Next, we explore whether and how exposure to newspaper affected Park's vote share before and after the government's tightened control of the press in the mid- to late-1960s. Given that the four national newspapers—Chosun, Daehan, Dong-A, Kyunghyang—opposed Park's plan to extend military rule in 1963 and the Media Ethics Law in 1964, we expect districts with higher circulation of these four newspapers to be less supportive of Park in the 1963 election. However, we expect this negative correlation between newspaper circulation and regime support to no longer hold in 1967 due to the fact that (1) the government directly repressed or co-opted these newspaper agencies starting with Kyunghyang in 1966 and (2) the press media did not join, but rather criticized, the opposition party's campaign for free press during the 1967 election. With this in mind, we hypothesize that the relationship between newspaper circulation and incumbent vote share depends on the government's control over the media. We specifically develop the following two hypotheses:

-

1. When the government control of the media is more limited, the incumbent vote share is lower in counties with higher newspaper circulation.

-

2. When the government exercises greater control over the media, the incumbent vote share is higher in counties with higher newspaper circulation.

Lastly, we investigate the effect of exposure to radio on support for Park. Given accounts that (1) the broadcast media, unlike the press media, were more consistently susceptible to government control and (2) the broadcast media served as a mouthpiece for the government increasingly toward the installment of the Yushin Constitution in 1972, we expect districts with more exposure to radio to be more supportive of Park towards the end of his pre-Yushin regime (i.e., the 1967 and 1971 presidential elections). We therefore present the following third hypothesis:

-

3. The incumbent vote share is higher in counties with more exposure to radio during the period in which the government has tightened its control over the media.

In our regression analyses we consider various county-level characteristics as control variables that may affect the relationship between media exposure and voting behavior. These include population size, land size, population density, percent male, percent population aged 60 and older, percent eligible voters, and percent married.

Data

Newspaper Content. Using the Naver Digital News Archive,Footnote 17 we examine all newspaper articles from Dong-A and Kyunghyang from two weeks prior to Election Day until the day before Election Day for each election.Footnote 18 For both elections, the date of the polls was announced only two weeks prior to the election itself and print coverage of the elections was heaviest during this period. The articles provide information on the elections, candidates, campaign rallies, and summaries of campaign speeches made by the candidates. The resulting sample is 412 articles. For each newspaper article, we coded (1) whether the content of the article has a negative or positive implication for Park Chung Hee and (2) the source of that information (i.e., the incumbent or the opposition party).

Newspaper Circulation. The data on newspaper circulation in 1963 and 1969 come from two volumes of the National Survey of Newspaper Circulation [Chǒn'guk sinmun pogǔp silt'ae] published by the Ministry of Communication. Using these publications, we construct the circulation data of four major newspapers—Chosun, Daehan, Dong-A, and Kyunghyang—at the county level. We linearly interpolate the circulation figures between 1963 and 1969 to get an estimate for the circulation in 1967.Footnote 19

Radio Signal. To estimate radio signal strength, we collect data on radio transmitters in South Korea using publications by the Korea Broadcasting Business Association (Broadcasting Yearbook, 1969 and 1973) containing information on location, frequency, call letter, power, and construction date of all radio transmitters in South Korea. We first identify the locations of radio transmitters in 1969 and 1971. We then calculate the signal strengths from all radio transmitters treating the geographic center of the election district as the receiving location and take the maximum of the calculated signal strengths as our measure of radio exposure of the district.

The spatial boundaries of the election districts are created based on the geographic information system (GIS) data that contain administrative districts of South Korea in 2012. We compared administrative districts in the GIS files and the election district maps for the 1967 and 1971 elections. The administrative districts tend to be finer than the election districts—that is, many election districts include several administrative districts. Therefore, we are able to combine administrative districts in each election district to generate the boundaries of the election districts.

To calculate the predicted radio signal strengths, we use the Irregular Terrain Model (Hufford Reference Hufford2002), which has been used in previous studies (e.g., Olken Reference Olken2009; Enikolopov, Petrova, and Zhuravskaya Reference Enikolopov, Petrova and Zhuravskaya2011; DellaVigna et al. Reference DellaVigna, Enikolopov, Mironova, Petrova and Zhuravskaya2014). Figure 1 displays the variation in radio signal strength in 1967 and 1971.

Figure 1 Variation in Radio Signal Strength in (a) 1967 and (b) 1971

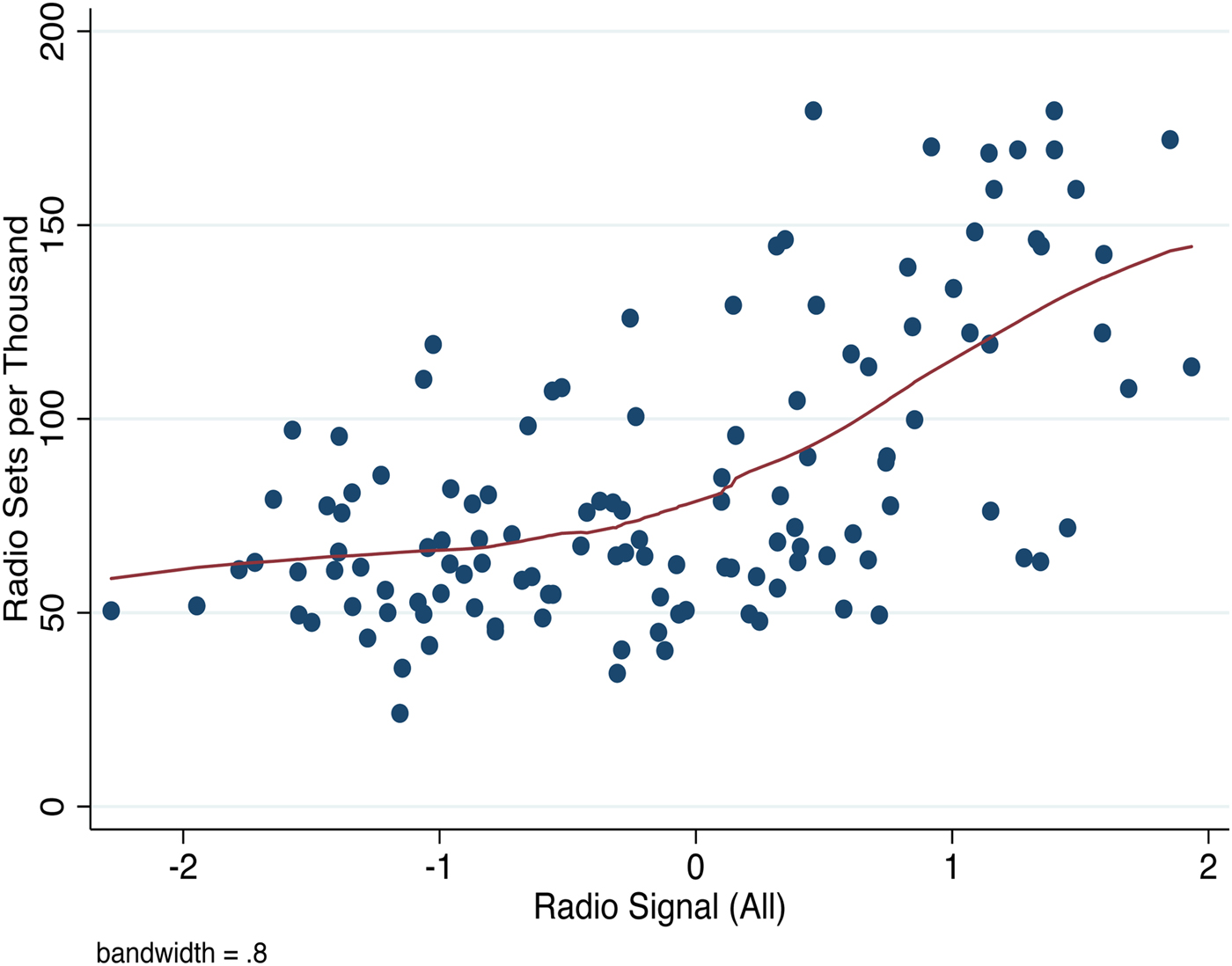

To check whether our measure of radio accessibility is correlated with radio ownership, we collect data on the number of radio sets in South Korea at the county (si, gun, gu) level in 1969 using the National Distribution of Radio Receivers [Jeonguk Susingi Bogeop Siltae] published by the Ministry of Culture and Information in 1969. The correlation between radio signal strength and the number of radio sets per thousand in 1969 is 0.67.Footnote 20 Figure 2 shows the relationship nonparametrically. The figure indicates that radio listenership, measured as the number of radio sets per thousand, is positively correlated with the predicted radio signal strengths, especially when the signal is above a certain threshold.

Figure 2 Radio Signal and Radio Sets in 1967

Election and Census Data. The election data is from an online elections data archive compiled by the National Election Commission (NEC).Footnote 21 We construct county level presidential elections data for 1963, 1967, and 1971. The data on demographic variables are from Statistics Korea.Footnote 22 We construct the following variables at the county level: population, percent male, percent population aged 60 and older, percent eligible voters, and percent married. Using GIS data, we also measure the land size (km 2) as well as population per square kilometer of each election district.Footnote 23 For the analysis of the effect of radio, we aggregate the data at the election district level.

RESULTS

Newspaper Content

Through a content analysis of 412 articles on the 1963 and 1967 presidential elections, we find that the government's tighter control of the media in the late 1960s is associated with media coverage favoring Park. Both newspapers covered accusations made by the opposition in 1963 prior to the election, but in 1967 the number of such articles decreased significantly, along with the number of articles with negative implications for Park. For example, in 1963 the opposition candidates demanded that Park resign from the race by questioning the legality of Park's having joined the Democratic Republican Party and run as a presidential candidate while being the Chief Head of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction. They also raised doubts about Park's anti-communist ideology, based on rumors regarding his past involvements with the South Korea Workers Party (a communist party in South Korea that existed from 1946 to 1949) and the Yŏsu-Sun'chŏn Rebellion, a leftist movement against the South Korean government in 1948. Furthermore, the newspapers reported the opposition party's claim that Park's Democratic Republican Party was created with funds provided by a North Korean spy. In 1967, the opposition attacked Park for an alleged intervention in election by involving government employees in campaigning and vote buying.

Figure 3 shows that for Kyunghyang the number of negative articles decreased from 54 (47.8% of the total articles) in 1963 to 15 (15.4%) in 1967, and the articles citing the opposition party decreased from 31 (27.4%) to 11 (10.6%) as well. As for Dong-A, negative articles decreased from 81 (60.9%) in 1963 to 28 (45.2%) in 1967. The articles citing the opposition party also decreased from 46 (34.6%) to 14 (22.6%). These results show that there was a noticeable change in the coverage and content of newspaper articles between 1963 and 1967 as state censorship increased in the late 1960s.

Figure 3 Newspaper Coverage of Presidential Elections in 1963 and 1967

Newspaper Circulation

Figure 4 shows the relationship between circulations (per thousand) of the four major newspapers—Chosun, Daehan, Dong-A, and Kyunghyang—and the incumbent vote share. We find that newspaper circulations are negatively correlated with the incumbent vote share in 1963, when state control of the press was weaker. This relationship, however, disappears in 1967 as the government tightened its control over the media. Consistent with the results in the previous section, Figure 4 suggests that government control over the media undermined the watchdog role of newspapers.

Figure 4 Newspaper Circulation and Vote for Presidential Party, 1963 and 1967

To examine this relationship more systematically, we estimate regressions of the following form:

where i and t index county and year, respectively. Inc Vote is the incumbent vote share, Newspaper is newspaper circulation per thousand, Y1967 is a dummy variable for the year 1967, X is a set of control variables, and ε is an error term. Negative β 1 suggests that the incumbent vote share is smaller in areas with high newspaper circulation. More importantly, positive β 3 implies that this relationship between newspaper circulation and the vote share becomes weaker in 1967.

Table 1 provides the results.Footnote 24 The coefficients of newspaper circulation are all negative and statistically significant, which implies that the incumbent, Park Chung Hee, received fewer votes in counties with higher newspaper circulations. The estimates suggest that one additional copy per thousand of Chosun, Daehan, Dong-A, and Kyunghyang is associated with 0.38, 0.37, 0.15, and 0.69 percent fewer votes for the incumbent party, respectively. As predicted, the coefficient for the interaction term is negative and statistically significant, which suggests that the negative relationship between newspaper circulations and incumbent vote share disappears in 1967. In fact, there is a substantive effect of media control on the relationship between newspaper circulation and incumbent vote share. Back of the envelope calculations suggest that one standard deviation increase in the circulation of Kyunghyang (about eight additional copies) is associated with 5.5 percent decrease in incumbent vote share. However, in 1967, after the enforced sale of Kyunghyang, one standard deviation increase in the circulation is associated with 1.7 percent increase in incumbent vote share.

Table 1 Newspaper Circulation and Vote for Presidential Party

Robust standard errors in parentheses. A dummy variable for the year 1967 is included. Control variables are: population, population per km 2, percent male, percent aged 60 and older, percent married, percent eligible voters, and the land size (km 2). All the variables except population per square km and the land size are measured at the county level. Population per square km and the land size are measured at the district level. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

In Table 2, we estimate the relationship between newspaper circulation and the incumbent vote share separately for the years 1963 and 1967. Figure 5 visualizes the coefficient estimates for each newspaper for both years, along with 95 percent confidence intervals. As the Figure shows, the coefficients for newspaper circulation are all negative and statistically significant in 1963. However, the estimates for newspaper circulation are either positive or not significant. These results confirm our results in Table 1 that the negative relationship between newspapers circulation and the incumbent vote share disappears in 1967.

Figure 5 Newspaper Circulation and Vote for President Party

Table 2 Newspaper Circulation and Vote for Presidential Party

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Control variables are: population, population per km 2, percent male, percent aged 60 and older, percent married, percent eligible voters, and the land size (km 2). All the variables except population per square km and the land size are measured at the county level. Population per square km and the land size are measured at the district level. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The Park regime's tighter control of the media in 1967 can cause a change in consumption patterns of newspapers among voters, which can bias our results. For instance, if the newspaper circulation increased in areas where the regime was successful in silencing the opposition, our estimates could be upward biased. To empirically address this concern, we repeat the analyses fixing the circulation at the 1963 level, before the government changed its tactics towards the print media. The results, reported in Appendix B Tables 3 and 4, in the online supplementary material, remain similar to our main results.

Radio

We now show the relationship between regime support and exposure to radio, a media outlet that was more consistently controlled by the Park regime. We regress the incumbent vote share on radio signal strengthFootnote 25 with the following form:

where i and t index district and year, respectively. Inc Vote is the incumbent vote share, θ t is a year fixed effect, which control for time-varying nationwide shocks. Radio is radio signal strength, X is a set of control variables, and ε is an error term. We include a lagged vote share (from 1963 and 1967 elections) to account for the possibility that radio signal strength is positively correlated with previous support for the authoritarian regime. Positive β 1 would support our hypothesis that higher exposure to radio is correlated with higher incumbent vote share.

Before we present the main results, we show the determinants of radio signal strength in Table 3. The results in columns (1) and (2) show that radio signal is positively correlated with population density and percent male and negatively correlated with percent aged 60 and older and the land size, suggesting that radio reception was higher in urban and industrialized areas. More importantly, radio signal strength is not correlated with lagged incumbent vote share, as shown in column (2). This result is assuring because it suggests that radio reception was not likely to be affected by previous electoral support for the incumbent.

The results of the main analyses are shown in Table 4. The estimate in column (1) suggests that one standard deviation increase in radio signal strength is associated with 2.6 percent increase in the incumbent vote share. The results remain similar when we include the lagged incumbent vote share, as column (2) shows. Overall, our results are consistent with our expectation that during the period in which the government tightened its control over the media, more exposure to radio is positively associated with electoral support for the authoritarian incumbent.

Table 3 Determinants of Radio Signal Strength, 1967 and 1971

Bold = Significant at .05 level. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Year fixed effect included. Radio signal vari- ables are standardized. All the variables are measured at the district level.

Table 4 Radio and Vote for Presidential Party, 1967 and 1971

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Year fixed effect included. Radio signal variables are standardized. Control variables are: popula- tion, population per km 2, percent male, percent aged 60 and older, percent married, percent el- igible voters, and the land size (km 2). All the variables are measured at the district level. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

CONCLUSION

Authoritarian rulers have long understood the power of media in influencing the mass. They exercise control over media to not only disseminate propaganda and information that favor their regimes, but also to discredit any possible political alternatives by deligitimizing opposition forces. This study explored whether and how mass media affects regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes, where independent media exist and there is variation in the extent to which these regimes exercise control over the media. Modernization theory and the democratization literature posit a positive relationship between development in mass media and political liberalization. Studies on media and elections in advanced and consolidating democracies show that media has a liberalizing effect by playing a watchdog role. However, despite the theoretical expectation in the democratization literature that media can undermine authoritarian rule, scholars and policymakers have also been pessimistic as to whether media can truly be independent from state control and play a watchdog role in authoritarian regimes; indeed, the findings are the contrary, that media is an instrument of control.

This study examined the effect of media exposure on regime support in South Korea during Park Chung Hee's pre-Yushin regime (1961–1972). This period is classified as competitive authoritarian, but over the time period, the government exercised varying degrees of control over media, allowing us to compare periods of tighter and looser control. Through a content analysis of newspaper articles, we demonstrated that there is, in fact, a difference in media content before and after the government's increased control over the media. Subsequently, using subnational level data on media exposure and regime support, we have shown that greater access to media was correlated with more opposition to the authoritarian incumbent but only when the government's control of the media was weaker.

Our work advances the growing literature on competitive authoritarianism by demonstrating that mass media has a conditional effect in competitive authoritarian regimes depending on the extent to which regimes allow free media. Given that media is neither completely free nor fully controlled in hybrid regimes, when evaluating the effect of media development on democracy, scholars and practictioners should theoretically and empirically consider the divergent effects that media have in various competitive regimes. To better understand the political effects of mass media in competitive authoritarian regimes, more attention should be paid to the conditional effects of media exposure depending on the timing and extent of media control.

Lastly, we also add to the discussion of repression and mobilization in authoritarian regimes. We have a much better understanding about the effectiveness of mobilizing support through patronage and political institutions than about the effect of state repression (e.g., Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Schedler Reference Schedler2002). Dictators can use repression to eliminate threat to their rule, but violent repression can further decrease the political legitimacy of their regimes (e.g., Gurr Reference Gurr1970; Opp and Roehl Reference Opp and Roehl1990). Our results suggest that media control—as a form of repression—can also silence opposition, but the subversive power of mass media cannot be ignored either. While government-controlled media can help bolster authoritarian regimes, more indpendent and free media in hybrid regimes can have corrosive effects on dictatortorial rule.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2016.41.