5.1 Humanitarian Accountability

Accountability is a moral precept that holds people answerable for their deeds, either to themselves, to someone else, or to a principle. A broad definition sees it as ‘the giving and demanding of reasons for conduct’, usually encompassing the possibility of sanctions.Footnote 1 While it is a ubiquitous standard, accountability is particularly critical for organisations that pursue a moral cause and are founded on trust.Footnote 2 The various accountability obligations that guide the work of aid providers encompass hierarchical principal–agent relationships, introspection and contractual ties, and voluntary patronage. Hence, a basic classification distinguishes vertical (upwards), horizontal, and diagonal (downwards, or social) accountability.Footnote 3

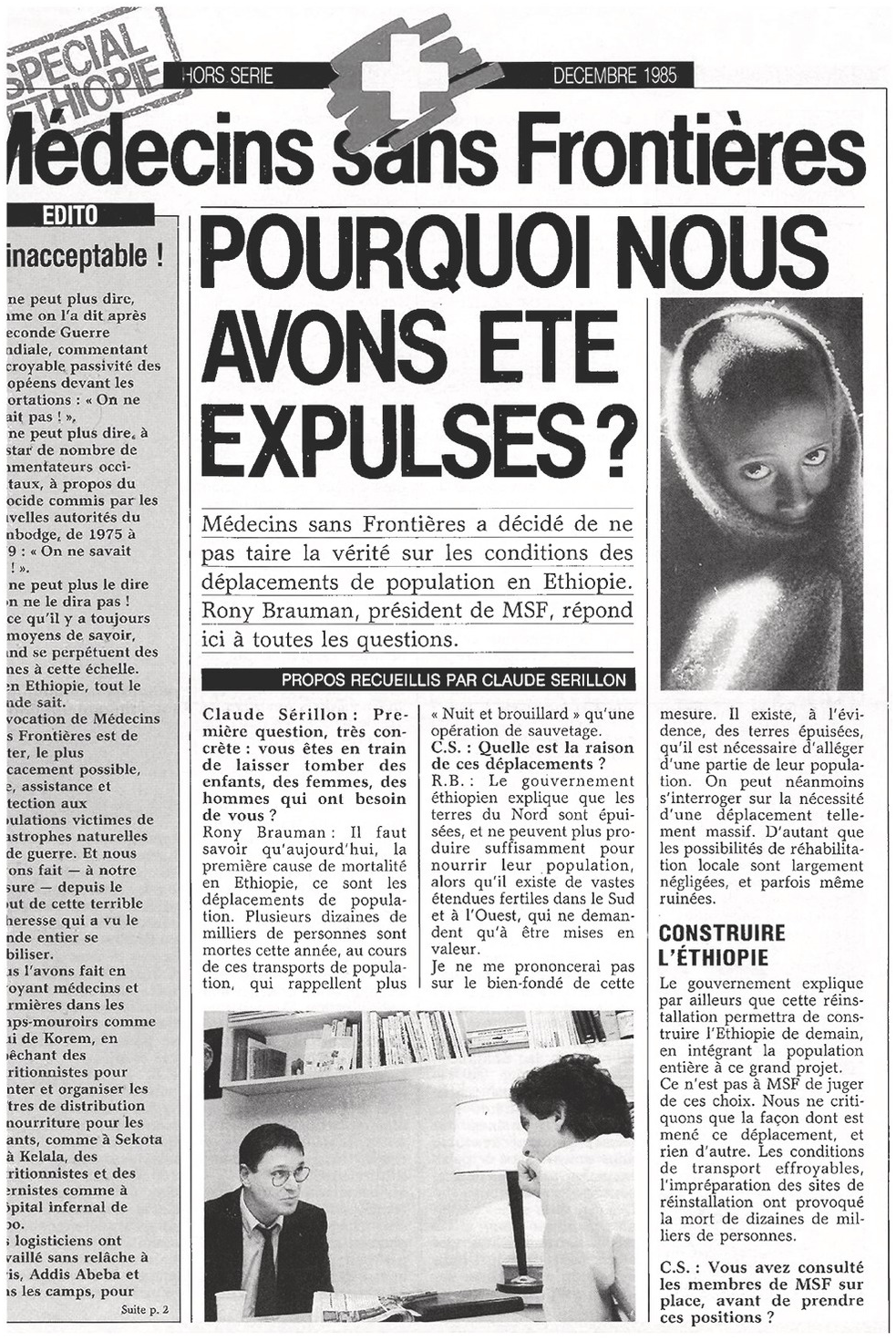

While accountability is a universal principle arising from the dependence of human action on conscious decisions, it is also a hallmark of neo-liberal governance and the notion of ‘rational choice’ that has increasingly permeated the language and culture of humanitarian affairs.Footnote 4 However, the provenance of accountability goes beyond any particular school of thought and has been strongly in evidence over the past half-century. As early as the 1970s, there was a growing interest in social accounting,Footnote 5 and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) gave it a deliberately expressive twist with the propagation of its philosophy of témoignage, or, speaking out.

Moral Bookkeeping

Accountability is a prominent concept today – so much so that it is at risk of becoming a buzzword – and has always been a prerequisite for the legitimacy of aid efforts. A rare study analysing the emergence of the British charity market in the late nineteenth century argues that self-regulation and the establishment of accountability mechanisms were crucial for this development.Footnote 6 In its affinity with history, accounting provides a normative framework for reporting and bookkeeping practices.Footnote 7 However, few studies have mapped humanitarian accounting in a historical perspective. This absence aligns with the observation that ‘the history of NGOs as businesses has yet to be written’, and with the call for an alternative narrative of humanitarianism based on its ‘capitalist logic’.Footnote 8 Moreover, it coincides with the widespread ignorance of how calculative routines foster legitimacy, something Herbert Hoover cited in a statistical overview of his Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during the First World War:

The multitude had but little concern for the bookkeepers in the back rooms of the offices of the relief organization. But the work of these men was of the utmost importance to those in official direction, not only that the relief undertaking might be effectively performed and presented to the world, but that our honor and the honor of our country in this trusteeship should never be challenged.Footnote 9

Accounts as lieux de mémoire of their relief efforts are enduring monuments for philanthropic organisations, encompassing both economic and symbolic confirmation of their power. They are documents of altruistic accomplishment, similar to those that furnish individual donors – apart from a sense of pride – with their ‘warm glow’ of inner goodness. Reports of how their gifts are delivered, what such gifts mean to the distributors and beneficiaries, and the gratitude that they produce give donors an emotional return on their investment. At the same time, gratitude is a confirmation of the donor’s role and may trigger societal, economic, and political transformation. Aid agencies are, therefore, eager to receive and document their share of moral credit. While some donors may display a lack of interest in a formal accounting, once a concern for impropriety or fraud is raised, the documentation of proper agency and the responsible administration of donations become essential. As the willingness to donate presupposes a belief in the appropriate distribution of aid, so accounting for revenues and allocations is a critical element of the moral economy.Footnote 10

All of these issues reveal characteristic differences between humanitarian accounting and that of for-profit businesses. Apart from efficiency, the moral economy of the former is also bound up with legitimacy, governance, and justice. For example, humanitarian gifts may be earmarked and subject to restriction, in which case their use for overhead expenditures or additional fundraising becomes problematic. Moreover, humanitarian organisations are generally expected to put their funds to work immediately, even at the expense of utility. Their notions of distributive justice are, thus, closely linked to procedures of accounting.Footnote 11 At the same time, donations can be badges of social status, relational aspirations, and communalisation. The representation of prominent people on ‘rolls of honour’ and other donor lists may garner attention, as may lack of charity be reputation-damaging (a phenomenon that seems to have decreased over the past century).Footnote 12 Although the economic power of donations is life-saving in absolute terms, its significance is frequently judged according to the circumstances of the individual contributor. The attention devoted to the humble gifts of poor people; donations from marginal or disadvantaged groups; and the pocket money contributed by children illustrate a ‘moral’ bookkeeping notion that may have its roots in religious tradition.

The documentation of material sacrifices affects the quality humanitarian causes acquire when adopted by a mass movement, and in turn reflects back on the movement and its surrounding society as moral high ground. A national effort thus becomes a catalyst of purification and cohesion. Moreover, the fact and spirit of giving may appear more momentous than the actual sum raised, even to beneficiaries: although the means of alleviation are commonly inadequate, the recognition of those who are suffering, the experience of solidarity and the provision of partial relief may serve to energise and raise the hopes of vulnerable populations.

Moral Economic Priorities

Viewing events from a moral economy perspective offers a partial remedy to the absence of business scripts and accounting practices in humanitarian studies. Ebrahim’s taxonomy of accountability mechanisms includes reporting, evaluations, participation, self-regulation, and social auditing.Footnote 13 Sources for investigating these dimensions include financial disclosures, annual reports, and other publications that document ideas, actions, and circumstances. Such accounting material shows how aid agencies pursued governance, justice, effectiveness, and legitimacy. The existing records supply detailed information on particular relief efforts. At the same time, any analysis of aid provision should be mindful of Giddens’s observation that the power of actors lies in their capability ‘to make certain “accounts count” and to enact or resist sanctioning processes’.Footnote 14

Accounting has been interpreted as a tool for handling ‘the tensions that surround moral-economic experience’ through an evaluation of the suitability of human choices and actions.Footnote 15 The abundance of human suffering and the consequential need of an efficient application of resources and a plausible selection among humanitarian causes are strong motives of accountability.Footnote 16 More specifically, the arena of ethical options between the donor and beneficiary commitment of relief agencies has been qualified as ‘accounting’s moral economy’.Footnote 17 This entails the prioritisation of certain stakeholders over others and, thus, encompasses needs assessment and the mechanics of triage.Footnote 18 However, the choice is generally not discretionary. Observers agree that an organisation’s upward accountability ‘for itself’ generally overshadows its social accountability ‘for the other’. The voluntary surrender of money and power disparities suggest a paternalistic moral compass that requires humanitarian agencies to be financially accountable to their funders, overriding broader normative postulates of social accountability. Much of the available literature deplores the donor-affinity of aid agencies compared to what frequently appears to be lip service to beneficiaries.Footnote 19

Thus, the moral economy in question is shaped, on the one hand, by an asymmetry of tangible material stewardship, and on the other, by the more elusive commitment that ideally accompanies a gift. The difficulty of imagining a reversed transfer of resources or compelling social accountability mechanisms is ‘the uncomfortable reality of charity’, which explains why the broadly advocated revaluation of beneficiaries makes little progress.Footnote 20 Principals may be weak, agents strong, and professional humanitarianism may have its intrinsic logic. However, this does not ultimately provide support to recipients or make ethical imperatives on their behalf coercive. As long as social accounting remains voluntary and confronts unequitable recipient societies that are hard-pressed by an emergency, it cannot advance accountability or raise critical issues effectively.Footnote 21 Rather, accountability continues to presuppose subordination under the post facto scrutiny of a legitimate superior. The basic model remains that of an agent liable to a principal who provides resources for a specific purpose. Transfers entail an understanding of the right to expect material improvement and accounts of how means have been used.Footnote 22 As an internalisation of moral claims held by an external authority, accountability frequently emphasises the asymmetry between donors and recipients.Footnote 23

Accountability is thus enmeshed with power, and at best may be a display of goodwill when exercised downwards.Footnote 24 Rather than ‘multiple accountabilities disorder’ (MAD) or agency loss through obstinate humanitarian organisations, the main problems remain the principal’s (i.e., donor’s) exercise of authority and the agent’s ‘over-accountability’.Footnote 25 Fraud and abuse are a particular concern in such an idealistic field as humanitarianism, making reliable books a necessity. However, an obsession with accountability and administrative integrity can foster proceduralism and risk aversion that may undermine relief work in emergencies – and the effectiveness and efficiency of collective action in general.Footnote 26 At the same time, visible downward accountability may serve the purpose of satisfying donors, that is, it may be a function of upward accountability, or it might entrench local inequalities.Footnote 27

5.2 Figures, Narratives, and Omissions: Ireland

Aid providers accounted for their efforts at the time of the Great Irish Famine in ways that varied greatly. Accounting was generally a tool for apportioning and keeping track of donations, satisfying donors and partners, and creating legitimacy for the aid approach chosen. In the mid-nineteenth century, there was a general expectation that relief efforts would be publicly accounted for in the press. Double-entry bookkeeping was widely practiced, but there was no overall model of accounting, and each organisation chose its own way of public disclosure. Table 5.1 presents an overview of major organisations that distributed relief in Ireland between 1846 and 1850. Many smaller-scale channels also received donations. These included local committees whose distribution need not be in compliance with government rules (and therefore not systematically registered), various community charities and churches whose social work took on the task of famine relief, and private money that was passed from individual to individual. The total sum of voluntary contributions might thus have amounted to £1.5 million (the real price equivalent of £135 million in 2018Footnote 28).

Table 5.1 Distributors of contributions for Irish relief, 1846–9.Footnote 30

| Organisation | Main collection areas | Period | Sum (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Relief Association (BRA)* | England, colonies, worldwide | 1847 | 376,397 |

| Local Irish committees | Ireland | 1846–7 | 314,259 |

| Society of Friends | USA, England | 1846–7 | 201,982 |

| General Central Relief Committee for All Ireland (GCRC) | England, colonies (Canada, India), Ireland, USA, worldwide | 1847–9 | 83,935 |

| Protestant Relief Societies (Wesleyan, National Club, Spiritual Exigencies, Evangelical, Baptist) | England | 1846–8 | 70,391 |

| Catholic Church (estimation of contributions from outside Ireland only) | England, France, Italy, worldwide | 1847 | 65,000 |

| Irish Relief Association for the Destitute Peasantry | England, Ireland, colonies, worldwide | 1846–8 | 42,346 |

| Ladies’ Relief Societies for Ireland | Ireland, England | 23,835 | |

| Society of St Vincent de Paul | Ireland, France, the Netherlands, Europe | 1846–50 | 22,895 |

| Trustees of the Indian Relief Fund** | India | 1846 | 13,920 |

| General Relief Committee of the Royal Exchange | Ireland | 1849 | 5,485 |

| Total | 1,220,445 |

* BRA’s income destined for Ireland: £391,701 (of which £20,190 passed on to GCRC). In addition to £2,606 cash documented in its report, BRA distributed £4,886 in provisions for a Bristol committee (‘Irish and Scotch Relief Committee-Room’, Bristol Mercury, 20 Nov. 1847).

** From 1847 on, revenues of the Indian Relief Fund (£9,063) were transferred to the GCRC.

At the time, the famine was considered an internal Irish matter by the British. However, others saw it as the internal administrative and moral responsibility of the UK, which at the time was the wealthiest, most powerful country in the world, with an efficient government apparatus and a strong culture of voluntary action. By contrast, foreign countries lacked the bond of a joint body politic with the Irish, commanded humbler means, and could not easily imagine the extent to which unmitigated market forces and laissez faire policies were allowed to prevail in Ireland.Footnote 29 A disaggregation of the accounts of various organisations, tracking the geographic point of origin of Irish relief donations, shows that contributions from outside Ireland comprised less than one million pounds (Table 5.2). Ireland’s own share of voluntary famine relief was probably higher than that of any external country, but is difficult to approximate; outside contributions were more systematically recorded. Irish famine relief in the 1840s was a worldwide endeavour, but our mapping shows considerable variations in the degree of responsiveness.

Table 5.2 Voluntary contributions for Irish relief 1845–9 by region (approximation).

| Country/region | Major collectors | Sum (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Ireland* | Local committees, General Central Relief Committee for All Ireland (GCRC), Ladies’ associations, Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP), Irish Relief Association for the Destitute Peasantry (IRA), Society of Friends (SoF) | 380,000 |

| Britain | British Relief Association (BRA), Protestant societies, SoF, Catholic Church, IRA, GCRC | 525,000 |

| India/Indian Ocean | Indian Relief Fund, BRA, GCRC | 50,000 |

| Canada | GCRC, BRA | 22,000 |

| West Indies | BRA | 17,000 |

| Australia | BRA, GCRC, IRA | 9,000 |

| South Africa | GCRC | 4,000 |

| Other British dependencies | BRA | 2,000 |

| USA | Local committees, GCRC, SoF, Catholic Church | 170,000 |

| France | Comité de secours pour l’Irlande (Catholic Church), SVP | 26,000 |

| Italy | Catholic Church, IRA, BRA | 13,000 |

| The Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark | SVP, BRA | 5,000 |

| Germany, Switzerland | BRA, IRA, GCRC, Catholic Church | 4,500 |

| Latin America | Catholic Church, BRA | 3,500 |

| Russia | BRA | 2,500 |

| The Ottoman Empire | BRA, SVP | 2,000 |

| Spain, Portugal | BRA | 1,000 |

* Does not include unofficial charity not meeting government standards, the work of existing charities, informal local acts of charity, or domestic Irish donations to the Catholic Church used for famine relief.

The geographical perspective is informative in some ways and misleading in others. There is insufficient data for estimating the amount individuals of Irish descent contributed to English and imperial collections, but there is evidence that they were over-represented, in particular when considering the distribution of wealth. Moreover, expatriate UK citizens were often the ones to organise donations from distant parts of the empire and other locations worldwide.

Although most donations from abroad came from England, the Irish were looked upon in Britain as an unruly and backward people, in a way we recognise from Orientalist discourse. As a people, the Irish lacked the goodwill that they enjoyed in places like the USA, France, or Italy. Irish landlords largely shared the image problem of their tenant farmers, and only in the north and east of Ireland was there a conspicuous middle class. In fact, the final report of the BRA claimed that the failure of the staple food crop in western Scotland had been as severe as in Ireland, but praised ‘the prompt and systematic exertions which were made by the resident landowners and others in Scotland’. The BRA had placed its funds for Scottish relief at the disposal of two local committees. The approach towards Ireland, where there were few reliable agents, differed, and the Irish crop failure reportedly resulted in disproportionate suffering. Therefore, rather than local civil society, a government agency for military supplies, the Commissariat, was given primary responsibility for the distribution of relief.Footnote 31

Despite prejudice towards Irish beneficiaries, the sum raised by the BRA during the Great Famine exceeded that of any other campaign at the time. It included substantial contributions from Catholics, Irish, the British Colonial Empire, and foreigners of various nations. Nonetheless, English Protestants donated more than any other source outside of Ireland.Footnote 32 Apart from reflecting geographic proximity and financial means, it illustrates that the commitment emanating from political association, although still inadequate, was greater than that resulting from ethnic or spiritual ties. Alternative means of voluntary aid, such as government relief measures, denominational prayers, and private remittances, contextualise rather than change this picture.

An analysis of the accounting message of different organisations shows both similarities and varying approaches. Most fundraisers were eager to emphasise the broad background of their donors, including those from the establishment, celebrities, and also common people and groups whose donations represented a sacrifice. Thus, contributions by convicts, slaves, and Native Americans received special attention in the press. For example, an Irish newspaper exclaimed: ‘“Lo! the poor Indian” – he stretches his red hand in honest kindness to his poor Celtic brother across the sea.’Footnote 33 The first advertisement by the BRA set a precedent, listing a few humble donations among prominent and comparatively high ones, including a collection from a family’s children and servants.Footnote 34

British accounting, both governmental and voluntary, stressed the extent of relief efforts and the discharge of one’s duty; it was geared to declare the end of famine and justify the cessation of aid. By contrast, the accounts of the Irish Quakers, who distributed most US and some British relief, tended to reveal the insufficiency of aid efforts, being both critical of the British government and self-critical, while conveying a sense of Quaker leadership in the humanitarian sector. US accounts emphasised rallying around Irish relief as a manifestation of national unity and an acknowledgement of essential humanitarian values. For the USA, supporting the Irish was both a goal in itself and a challenge to British primacy in this field (even when Britain touted their unpolitical engagement in an integral part of the UK). Finally, while the Catholic Church proper accounted for its aid sporadically, Catholic newspapers and civil society organisations like the Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP) offered some of the most transparent accounts of aid and moral economic calculations at the time.

British Relief

‘Were no accounts kept? Some people think that figures only tend to obscure (smiling).’ This sardonic remark and gesture of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland rebuffed the Reverend Townsend, a member of a deputation to Dublin, in November 1847. Townsend, who had been one of the deputies from Skibbereen to London a year earlier, had voiced the ‘belief’ that not much money collected during the previous winter was left, if any.Footnote 35 On another occasion, while documenting the use of funds in a letter to a major donor, Townsend pointed to the expense of having to account for the daily expenditure of the many small sums he received.Footnote 36

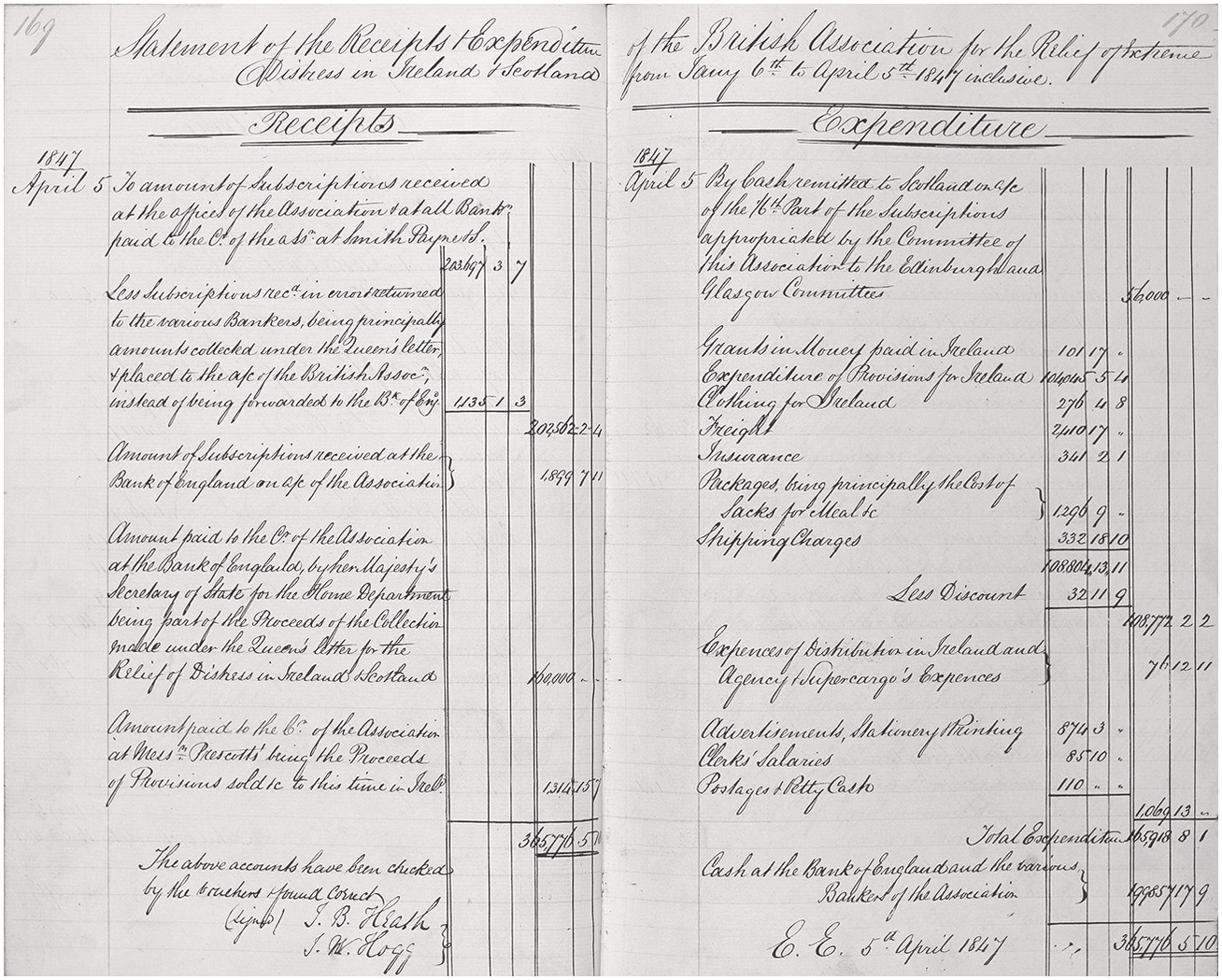

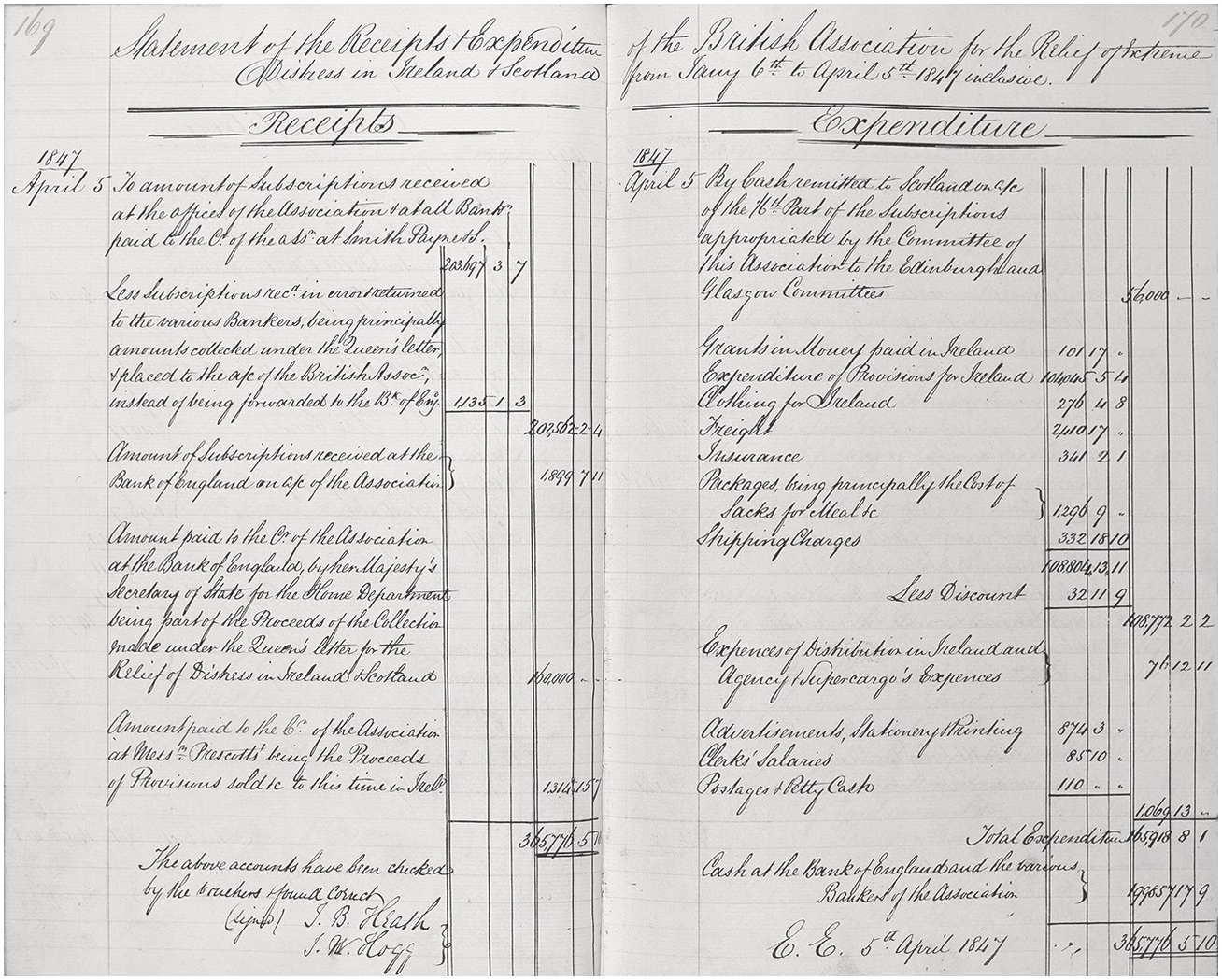

Accounting technologies were as crucial for British voluntary aid (see Figure 5.1) as they were for the government’s struggle to keep entitlements for official relief at bay – principally by excluding the purportedly ‘undeserving poor’ and by depressing benefits to an uncomfortably low level.Footnote 37 The general suspicion was expressed by a Times journalist who told the Skibbereen ministers in December 1846, during their fundraising mission to London, ‘that if the people of England were satisfied they would not be abused and laughed at by the Irish, it was not one million, but millions would be subscribed’.Footnote 38

Figure 5.1 Account book of British Relief Association, entry of 5 Apr. 1847.

Despite the safeguards they took against fraud and their blunt communication during the fundraising campaign, the BRA was not even the limited success some researchers have claimed. Rather than creating trust, prejudices were perpetuated against Ireland by the way money was spent, which may in turn have tempered donations as much as the perceived Irish lack of gratitude.Footnote 39 The contribution of one guinea by an anonymous ‘Saxon, who loves his brother Pat with all his faults’, and the tenuous documentation of gratitude in the final report of the BRA (which had a technical section headed by an address to the Ottoman sultan but without a reference to the queen) illustrates this ambiguity.Footnote 40 One-sixth of the £470,041 collected was reserved for Scotland, reducing the Irish share to £391,700. Although celebrated as an achievement, this amount barely exceeded the funds raised during the partial Irish famine of 1822, and represents a fraction of what the Times journalist had estimated would be raised if English confidence in the cause of Ireland could be inspired.

One of the functions of public accounting was the circulation of what Roddy, Strange, and Taithe call ‘a consistent tale of social hierarchies of giving’.Footnote 41 Suggested ‘appropriate’ contributions were solicited by establishing donor categories and subscription levels, and unlike later contributions, early ones were listed in order of status, rather than chronologically. Even before the first subscriber list had been published, Queen Victoria was persuaded to raise the amount of her initial subscription. Prime Minister Lord Russell also increased his contribution, giving himself precedence over the home secretary. It was not publicly acknowledged at the time that the Quaker banker Samuel Gurney made the first pledge of money, setting a benchmark of £1,000 for donations of comparable firms.Footnote 42

The official narrative started with the queen’s prompt donation and request to have her name placed at the head of the list. In light of her promise ‘of such further amount as the exigency might demand’, the queen’s failure to increase her initial subscription of £2,000 (apart from a £500 contribution to the Ladies’ Clothing Fund) signalled a lack of desire to support a greater relief effort.Footnote 43 Along with other members of the royal family, the archbishops of Canterbury and York (the latter made two donations, indicating another adjustment), the lord chancellor, and eventually his imperial majesty the Ottoman sultan, the queen’s name headed some two dozen lists of ordinary subscribers, collections, and colonial bodies, furnishing the voluntary subscription with examples of national duty among officials (within the limits indicated by the sums given) and lending the campaign exotic prestige.Footnote 44 The contributions were discussed in the press, along with rumours about a trifling royal donation of a mere £5; or a report that the sultan had been prevented, for reasons of protocol, from giving ten times as much or sending relief ships. Thus, money was seen by contemporary observers as symbolising humanitarian commitment and as a way authorities discharged their paternal and maternal responsibilities.Footnote 45

In 1846/7, the famine was viewed as a unique seasonal calamity (the role of the preceding government’s interventionist policy that had prevented excess mortality in 1845/6 was not widely known).Footnote 46 The food shortage persisted after the calamities of 1846/7, and the blight returned with full force in 1848 and 1849. Years of extreme mortality were to continue, but by autumn 1847, the UK government treated the famine as having come to an end. There was little suspicion abroad that this negation reflected wishful thinking and a preconceived downscaling of relief, rather than an authoritative statement by public servants accountable to those that they governed.

The cessation of exceptional relief measures funded by the UK government and the turn to a solely Irish-supported poor law in the autumn of 1847 marks the beginning of an ideologically motivated famine denial. Trevelyan’s quasi-official treatise, The Irish Crisis, published in January 1848, introduced a development image that attributed governmental and voluntary aid to Ireland back to ‘the potato system’ of an accounted for past. Selected data on funding, supplies, and policies corroborated the claim of an unparalleled relief effort that included a variety of experimental features. The reported figures demonstrated goodwill for the spiritual and temporal record, while claims that the Irish had been ‘saved from a prolonged and horrible state of famine, pestilence, and anarchy’, and that their case was ‘at last understood’ served to legitimise the status quo. At the same time, Trevelyan’s apologia celebrated the restrictive management of aid, including timely accounting techniques, as having laid the groundwork for a moral (and thus sustainable) improvement of Irish society that reliance on aid from outside could not undermine. As Trevelyan saw it, ‘great sacrifices’ were still required, as the Irish had been forced to realise ‘that the plan of depending on external assistance has been tried to the utmost and has failed … and that the experiment ought now to be made of what independent exertion will do’. Buttressed by conclusions drawn from recent experiences with Ireland, the underlying moral economic supposition was that relief, while occasionally a necessary evil, should exert pressure on the conscience of the local upper class and be distasteful to the pride of the lower classes in order to be properly contained.Footnote 47

With his early 1848 account of Irish misery, relief, and improvement, Trevelyan made the British government’s dismissive position on the Irish famine difficult to reverse, although those involved knew better. By 1849, the Treasury projected an outline of distressed areas of Ireland onto a railroad development plan, thus producing a contemporaneous famine map (Figure 2.1). Three colours were used to highlight (a) counties designated as ‘distressed’ by the Board of Works in May 1849 (the westernmost 60 per cent of the country); (b) areas bordering on the former that ‘should have been included’ in that category in the light of subsequent experience (10 per cent); and (c) areas that appeared ‘to be unable, under present circumstances, to provide from their own resources adequate employment for their population’ (10 per cent). However, the image of the distressed areas served as a depiction of the state of the country for internal administrative purposes only; there was no public acknowledgement of the needs depicted.Footnote 48

Against the background of generalised reluctance to provide aid, the 1847 BRA campaign demonstrated to the English, the Irish, and to the world-at-large (and even to the Almighty) that the UK lived up to a standard of civilised Christian solicitude for the well-being of fellow-citizens and supplemented government support with supererogatory voluntary action. Public accounting was a legitimising tool towards this end. At the same time, the voluntary campaign did not require the detail and frequency of governmental accounting reports. This decreased the workload on relief workers and resulted in more aid to beneficiaries.Footnote 49

Advertisements had already informed the public of some of the philosophy behind the use of funds when the BRA published its final report by early 1849. It included extracts of correspondence with agents, samples of working documents, resolutions of thanks, a balance sheet, tables of provisions, and a complete list of donors and ancillary collections. The report reveals the voluntary campaign’s dependence on official policy, but also includes one example in which public funding took over a measure instituted during the famine for some time after voluntary funds were exhausted. The issue was the feeding of school children, a major form of relief provided by the BRA from late 1847 to mid-1848, and which the BRA described as particularly satisfactory. The report viewed children as innocent victims of moral degradation who, by attending school, could be bearers of educational progress to society. The BRA chose poor law commissioners for Ireland as trustees of its remaining balance and by their actions endorsed the official denial that there was any continuation of the famine. It saw its own mission as having been accomplished and did not acknowledge the winter of 1848–9 as a period of repeated mass mortality.Footnote 50

Quaker Relief

Presuming that ‘evils of greater or less degree must attend every system of gratuitous relief’, the BRA report announced its confidence in having shown that any such evil had been ‘more than counterbalanced by the great benefits’ of its work for ‘starving fellow-countrymen’.Footnote 51 The Central Relief Committee (CRC) of the Society of Friends (SoF) in Dublin – the main broker of aid from the USA, and also an organisation supported by English Quakers and independent Irish and English donations – published its report in autumn 1852 in a different spirit. The committee explained the discontinuance of most of its efforts in the winter of 1847/8 as due to the exhaustion of relief workers (some helpers themselves having become ‘fit objects’ for aid and others dying), rather than because the situation had improved. When in the summer of 1849 Trevelyan, on behalf of the British prime minister, asked the CRC to resume its work (indirectly admitting governance failure and the premature nature of his own account), he was told that voluntary aid had necessarily been seasonal and that only the government commanded means to adequately address the prevailing distress.Footnote 52 Even the Irish Quakers admitted, ‘We have made mistakes of judgment in the selection of the means of relief, and committed errors in the details of administration; so that the means placed at our disposal have perhaps been less useful than they might have proved in other hands.’Footnote 53

The Quakers acknowledged that it was questionable for them to have used parts of the relief funds for a development project (a ‘permanent object’). While justifying an investment in their ‘model farm’, rather than in aid to the destitute, as having the greater benefit of wages compared to gratuitous relief, they showed that they had lost confidence in the profitability of their industrial experiment. Likewise, they described various fisheries projects as ‘failures as commercial undertakings’. They also discussed cash support versus relief-in-kind, anticipating much of Sen’s argument.Footnote 54

The CRC report totalled almost 500 pages. It accounted for £198,327, excluding 642 packages of clothing, the value of which remained undetermined. Of the total sum, £15,977 in cash and £133,847 worth of provisions (as its value was assessed in Ireland) had come from the USA in ninety-one shipments. The CRC discussed shifting public policy and what this meant for the liberality with which it offered its own relief. In addition, the report contained statistics on other organisations and pointed to a vast number of untraceable contributions there, estimating that the total sum of voluntary donations must have approached £1.5 million. The authors emphasised their close contact with fundraisers in the USA and fellow aid workers in Ireland. However, the voices of actual recipients were not heard in the report, and gratitude remained a minor issue in the documentation. Due to their meticulous accounting, the CRC occupied a special role among humanitarian organisations. They stressed their own reputation, including their capacity for self-criticism, which further increased the moral capital of the SoF. Moreover, they used their influence to advance the political argument that the problem of Ireland was a dysfunctional land law, rather than an improvident people.Footnote 55

US Accounts

Despite an early attempt at coordination, no joint campaign for Irish relief was launched in the USA. Regional hubs aggregated collections from areas near and distant, while Quakers, Catholics, and a number of small towns took independent action. The major regional committees were initially based in New York and New Orleans, with Washington, Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Charleston as supplementary centres.Footnote 56 The committees in New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston put out their own reports, and the Boston-based New England Committee published documentation of their field mission. Other committees probably accounted for themselves by notifying local newspapers.Footnote 57 US committees generally used their funds for the purchase of food for shipment to Ireland. In 1847, the British government defrayed freight expenses in the amount of £42,674, which was applauded in the USA. Overhead was thus significantly reduced, leading the head office of the Irish Quakers to announce, ‘The food put on board at New York, may be considered as laid down almost at the doors of the sufferers for whom it was intended.’Footnote 58 The fact that most US relief consisted of provisions-in-kind increased its value to the Irish and was so entered on the accounts of local Quakers. However, this effect seems to have been modest as famine prices rose to their highest level in Ireland before large US food shipments arrived.Footnote 59

The New York Committee, which administered cash and provisions valued at a total of US$242,043 (£50,531), tasked a subcommittee with preparing a report to satisfy contributors. It considered extensive documentation necessary because external donors could not be expected to follow account notes in the New York press. Another motivation was correcting ‘erroneous impressions that have obtained to some extent in Great Britain, in regard to the character and motives of the popular movement in America in behalf of the poor of Ireland’. The report was to show ‘an act of hearty popular benevolence, unconfined in its locality, disconnected with party, creed or sect, and coupled with no selfish end or aim’.Footnote 60 The statement also hinted at the suspicion that the USA had interfered in British–Irish affairs and had disparaged UK relief efforts, perhaps also alluding to US sympathies for the repeal of the union between Great Britain and Ireland, and UK–US rivalry over the Oregon territory.Footnote 61 While admitting that US donations were small in comparison to the country’s great wealth, the New York Committee maintained that the relief it provided had saved thousands from starvation, created ties across the ocean, and presented an example to the world. However, the committee devoted most of its space to lauding the campaign for its cohesiveness and promotion of Christian values among US citizens.Footnote 62

The Philadelphia Committee, citing the difficulty of estimating the value of the charitable acts made possible by its US$75,600 (£15,783) contribution, presented a simpler moral economic balance sheet: in Ireland, it claimed, the lives of thousands were saved, while in the USA, the hearts of thousands ‘were made to beat with pleasure, in the consciousness of good performed’. The report also suggested the enhanced positive relationship between nations as a permanent reward. Narrower in scope than the New York report, and without a list of subscribers or a full balance sheet, the Philadelphia summary presented a narrative into which key documents were integrated. It estimated that overall contributions channelled through Philadelphia had amounted to half a million US dollars, including separate collections from Quakers, Episcopalians, and Catholics, and more than US$300,000 in private remittances.Footnote 63

Boston’s first relief ship to Ireland became iconic. The USS Jamestown was a decommissioned battleship that the US government provided for a peace mission. With marked symbolism, loading began on St Patrick’s Day, and the ship’s reception in Cork was ecstatic. In place of a full account of activities and fundraising, the Boston Committee published a narrative of the voyage of the Jamestown written by its captain, Robert Bennet Forbes.

The report adhered to genre conventions with its extensive appendices of documents and economic accounts, but differed in several respects. It was more graphic than was common at the time, including a lithograph showing the ship’s departure from Boston harbour on 28 March 1847 (Figure 5.2). It also had poems of thanks that referenced the Bible: ‘A cup of water given … is registered in Heaven.’ The report’s brief first-hand accounts described scenes of horror with an accompanying comment that, considering the gravity of the situation, little more could be expected than to preserve the bare lives of the starving – with food that American hogs would reject. The report also suggested that Americans pay back a debt for relief that the Irish had provided to New England during the devastating war against Native Americans in 1676, including interest – the equivalent, it was said, of roughly US$200,000. Although the Boston Committee eventually managed to raise three-quarters of that sum (US$151,007, i.e., £31,525), in addition to receiving donations from New England through other channels, Captain Forbes wrote that Irish relief was ‘partly for the payment of an old debt and partly to plant in Irish hearts a debt which will, in future days, come back to us bearing fruit crowned with peace and good will’. Finally, while observing that England was ‘not deaf to the call of suffering Ireland’ and that the Irish expected too much, he noted their complaints of want of sympathy from the government and trusted that England would learn a charitable lesson and do more than she was doing in the future.Footnote 64

Figure 5.2 Departure of the USS Jamestown for Cork, Ireland, Boston, 28 Mar. 1847.

Accounting Practices among Catholics

Within the Catholic Church, donations were processed in a hierarchical, parish-based context; accountability was practiced through individual correspondence, epistles, and verbal communications to congregants. By the middle of the nineteenth century, these communal practices of the clergy were supplemented by such Catholic branches of civil society as voluntary associations and the religious press. While the bookkeeping practices of the Church tended to be lax, the SVP and the newspaper the Tablet represented a modernised moral economy with higher accounting standards.

Collections among Boston Catholics illustrate the poor documentation of most relief administered by bodies of the Church, reflecting the trust-base of their system. A study of Boston Catholicism, while conceding the difficulty of getting a clear picture of donated money and provisions, nevertheless estimates that Catholic charities in America conveyed US$1 million to the Irish clergy – a sum forty times the amount collected by Boston Catholics, and so highly improbable.Footnote 65

In New York, Catholics mostly transferred collections to the general city fund for forwarding to the Dublin Quaker committee in a display of ecumenical spirit. By contrast, the Catholic Church in Boston maintained their own separate fund. The documentation that has been preserved consists of correspondence between the bishop of Boston and his Irish colleague, Crolly, the archbishop of Armagh, in addition to scattered notes in a handwritten diocesan journal. These notes speak of various collection results, of an early interim ‘report to the people’ during a mass with a tally up to that point in time, and of the bishop’s estimate that the collection would amount to US$25,000 (plus private remittances by Catholics, which he believed had totalled US$125,000 for the first half of 1847). While the overall extent of the collection is evident, the only clear detail is that the bishop forwarded a total of £4,917 11 s 8 d to Crolly (US$23,550) to be distributed among the other archbishops of Ireland. But the calculation was left to the reader, and the final remittance was a round sum that must have been an approximation of a collection in US dollars.Footnote 66 At the same time, in a letter to Ireland that he read to his congregation, the bishop accurately noted that the Catholic solicitation had taken place before the general fund drive and therefore attracted early donations by Protestants; thus need, rather than faith, should determine the distribution.Footnote 67

Crolly stated that the archbishops had apportioned the distribution without distinction of creed, but did not specify the outcome of the division or the dispensation further down the aid chain.Footnote 68 Such lack of transparency was not a solitary case. Archbishop Murray of Dublin was reluctant to publicise how he distributed donations – his fear, according to one commentator, being that open accounting ‘might generate expectations which he would not be able to meet’.Footnote 69

By contrast, a nineteenth-century biography portrayed Archbishop MacHale of Tuam as a meticulous accountant and relief administrator. The writer (who lost the documents on which his book was based) claimed that MacHale did the whole work of receiving, acknowledging, and distributing donations unaided. However, MacHale’s interest in public accounting seems to have primarily emanated from the opportunity for political messaging. For example, in one acknowledgement of donations, he stated that it was a pity private charity was ‘rendered almost inoperative by the cruel and merciless theories of political economy; or, what is worse than theories, the cruel and merciless practical policy that has been adopted by our incapable rulers’. Elsewhere, he warned the government of the moral economy of hungry masses who would ‘prowl for food wherever they can find any to appease the cravings of hunger, which no argument of terror or persuasion, short of food, can appease’.Footnote 70

Vatican archives contain many details about Italian collections, and some records concerning the distribution of funds among Irish clerics; but attempts to aggregate this information have been limited and only sporadically published. A handwritten distribution chart for the second quarter of 1847 lists monies submitted to various Irish bishops and (to a lesser degree) monasteries. The total amount is £3,305, although due to a calculation error, the record underestimates the actual sum by £100.Footnote 71 In all, the Vatican sent approximately £10,000 to Ireland, £7,000 of which was collected in Italy.Footnote 72

Unlike the Holy See, the French committee for Irish relief published a concise tabulation of their accounts for the greater part of 1847, in accordance with the civil society standards to which the committee declared its adherence. However, it listed revenues per diocese, revealing its de-emphasised ecclesiastical perspective.Footnote 73 The French raised and distributed £15,917 among the Irish clergy in 1847, and an additional £4,000 in 1848 and 1849, when other relief efforts had slackened. They also published letters of thanks from the Irish clergy and a final report with an overall accounting. The report speculated that the French effort might have saved 60,000 lives directly and, as a foreign encouragement, might have produced additional ‘interest’ by stimulating the charity of the local middle and upper classes.Footnote 74

By contrast, the Catholics of England and Wales accounted for their relief work in a fragmentary manner. Proper balance sheets have come down to us only from the Lancashire District Catholic Fund, which brought in the highest proceeds of £4,921, and from the Northern District. In both cases, most of the revenue resulted from church collections. Whereas the northern distribution was scattered, the Lancashire fund was divided equally between the two archbishops in the most distressed southern and western parts of Ireland. This account also specified a minimum that Catholics from Lancashire had submitted through other channels.Footnote 75 A similar balance sheet for the district of York reported episcopal collections and donations by Yorkshire Catholics to alternative funds. The cases of York and of the Eastern District indicate that the way of publicising such accounts was as an attachment to pastoral letters delivered orally to the parishes, and only incidentally reprinted for a wider audience.Footnote 76

No other final accounts survive for dioceses in England and Wales, although some accumulated sums were published in the press at various points in time – principally in the Tablet. Thus, London reported £2,380 in early February 1847, and Wales approximately £422 in March.Footnote 77 No aggregated results are known for the Central District, but a church collection was reported from Birmingham, where relief efforts were concentrated on meeting the influx of Irish paupers to that city. As the London and the Central Districts passed their collections on to the GCRC via Murray, their overall totals may be approximated by studying the list of donations to that committee (£2,598 and £849, respectively).Footnote 78 The bishop of the Western district gave £5 to that fund out of his own pocket and published an impassioned plea for famine relief to his clergy, but his departure to Rome during the critical period seems to have preempted a coordinated effort at home. Instead, some Catholic churches of Bristol are recorded as having contributed to the city fund.Footnote 79

Not only did the Tablet’s modern approach to publicity make it the best source for information on English Catholicism and the Irish famine, but it became a channel for relief in its own right. After Fredric Lucas had issued an early call for aid, donations started coming in, and a collection began that raised more than £3,000 by the beginning of July 1847. The collection continued to amass scattered donations until 1852, the final year of the famine. No overall balance is known, but the Tablet published weekly accounts during the initial months of its drive, and an occasional summary or ad hoc notifications after June 1847. Later contributions were sometimes announced under the heading ‘Irish Poor’ and thereby merged with charity in general.Footnote 80

The amount received by the Tablet in the second week of January 1847 remained unsurpassed; the total for the last days of December and January was £1,202; the sum for February was approximately one-half of that; for March one-third; for April and May one-quarter; for June one-fifth. Contributions rapidly decreased after that. In general, donations were modest, and in many cases represented local collections taken among church congregations or solicited from the Irish community in England. ‘A few workmen’ sent five shillings, the smallest joint contribution, while the smallest individual subscription, given by ‘a poor English labourer’, was half a shilling. However, many individuals and groups donated several times over, or organised weekly collections. Some donors gave gold watches, silver cutlery, or precious textiles, which Lucas had to turn into cash. While this complicated the process of aid provision, it also conveyed a sense of the urgency of the aid cause.

Although the Tablet primarily solicited funds from Catholic residents of England, and engaged Catholic prelates and Catholic institutions for field distribution, some Protestants and people from abroad were among the Tablet’s contributors. Lucas mainly spread his relief throughout the severely afflicted western and southern parts of Ireland. Responding to appeals and correspondence published in his paper, and considering occasional requests by donors, he frequently indicated how he believed funds should be directed. To correspondents who faulted him for not sending money directly to local clerics, Lucas explained that the administrative burden of such a model would have been too high.Footnote 81

The Tablet, with its long-lasting documentation of first-hand reports on the famine, appeals for aid, and letters of gratitude, also stimulated and recorded many direct transfers by individuals or local groups of donors to Irish clerics: the aggregate sum would require a detailed analysis.Footnote 82 The most comprehensive private investment may have been made by E. V. Paul, a retired merchant from Bristol who, after having donated £5 through the Tablet, canvassed his home town for four and a half months, reportedly going several miles per day from door-to-door to solicit 1 s for the relief of sufferers in Ireland. The result of this ‘labour of love’, which he claimed made him feel ten years older, was another £115, partly submitted through the Tablet, and partly sent directly to various Irish clerics.Footnote 83 The fact that Paul suggested in the local press that he forwarded contributions directly to the neediest places, without mentioning his distribution through the Catholic Church, raises the issue of transparency.Footnote 84

In all, Catholic donations from England and Wales represented at least £20,000 out of the total of £525,000. This is double what might have been expected of a group which then comprised approximately 2 per cent of the population. The sum is even more remarkable since their numbers included many poorer individuals (frequently of Irish origin) and virtually excluded high society.

The Catholic institution that most systematically and openly accounted for its activities was the SVP. Despite consisting of a network of autonomous local branches, each of which was required to pay an overhead fee to the head office in Paris, the organisation granted the Cork ‘conference’ an extraordinary start-up gift of 100 francs (£4) in 1846. This gesture was meant to demonstrate the ‘spirit of fraternity’ among all Vincentians, and also illustrates the humble circumstances of the head office. In addition, the president and vice-president of the SVP gave a personal gift – eighteen copies of a lithograph that, when sold in Cork, brought in £25 (see Figure 5.3). Among other details and examples of field work, this event was extensively documented in the annual reports of the conference in Cork and the national council in Dublin.Footnote 85 Conferences held quarterly meetings on the local level, providing information that would ‘allow the members generally to judge of the mode in which the affairs of the society are conducted, and to do this by laying before them all the details of its usual operations’, including non-material aid such as sanitary measures and counselling.Footnote 86 By 1848, the Paris head office published the Bulletin de la Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul, with reports and financial summaries of the entire organisation’s activities, including selected details from Irish communiques.

Figure 5.3 Moïse sauvé des eaux (Moses Saved from the Water). Engraving by Henri Laurent after Nicolas Poussin, eighteen copies of which were a gift to Society of St Vincent de Paul Cork for fundraising purposes, 1846.

In 1847, the SVP’s extraordinary appeal for Irish relief raised £6,141 among its affiliates in France, Belgium, Italy, Turkey, Algiers, Mexico, England, and especially the Netherlands – the latter contributing almost half of the total sum. As an exception to general transparency, and apart from the separately transferred and reported English contribution, the aggregate sum was not broken down in the accounts and cannot be reconstructed in full detail. This levelling was intended to avoid methodological nationalism and emphasise the unity of the SVP. By contrast, the French Bulletin expected donors to read the table of distribution among Irish conferences with interest. In addition to this, the SVP chapter in Constantinople submitted £284 to the BRA.Footnote 87 The establishment of new local branches throughout Ireland was of particular concern in the matter of using additional funds from abroad. In 1847, international donations rose almost to the level of domestic contributions. However, collections from abroad tended to dry up over time and amounted to only £6,628 of the £22,895 in total funds raised between 1846 and 1850. This development can partly be attributed to the cautious financial management, reticence, and desire for reciprocity among the Irish, but also to the SVP’s aid philosophy, which favoured long-term expansion and commitment to a limited number of cases rather than indiscriminate all-around distribution. Only £2,410 of the funds from abroad were distributed by the end of 1847, facilitating sustained organisational growth over the following years.Footnote 88

In 1848, when there was still the prospect of a good harvest, the Irish SVP returned £300 for relieving the poor of Paris. The Irish branch was later convinced by the president general to retain a second instalment in order to benefit needier sufferers from the famine. This sum was invested in countering the Protestant mission in Dingle.Footnote 89 A SVP report included statistics suggesting that its work had reduced the number of converts to Protestantism (‘Soupers’) in the West Schull area, near Skibbereen, from 1,500 to 60, while the number of established Protestants had also declined from 600 to 300.Footnote 90

The SVP believed that face-to-face contact between volunteers and beneficiaries was the best means of offering assistance. For example, the Cork chapter commended itself as a powerful instrument for wealthier locals to alleviate the misery surrounding them with little cost or trouble to themselves. Unable to relieve suffering everywhere, the organisation made it clear that it needed to select its clients after the ‘likelihood of our being able to do most good’. This meant providing continuous relief, but in small increments, and preferably in kind, in order to guide clients towards self-help. Thereby, assistance could be provided to greater numbers. A particular concern was bridging periods of illness among breadwinners in order to prevent the degradation of whole families.Footnote 91 The national head office regarded such practices of triage as an economic service to the community, counteracting the increase of poorhouse inmates.Footnote 92

SVP Cork pointed out that it also attended needy Protestant families, although it did so reluctantly in order not to look like proselytisers (SVP also considered Catholics more afflicted and Protestant clergymen better equipped to provide relief). Moreover, SVP Cork maintained that its Christian charity blessed both the volunteer and the recipient, in contrast to mere almsgiving, which tended to degrade the latter.Footnote 93 They explained the shared ‘moral blessings’ of their work as follows: while the rich visitor enlarged ‘his’ mind in the encounter with a less favoured ‘fellow-creature’ and came closer to achieving salvation through charitable work, the poor counterpart experienced compassion and ‘his heart expands to the best influences of that divine Religion, which he must recognise as the principle that prompts the disinterested benevolence of which he is the object’. Ultimately, the subaltern elite who engaged in Irish SVP work stated their aim of downward accountability ambigiously as ‘raising tens of thousands of our fellow-countrymen from a state of abject misery, which makes the social condition of Ireland a disgraceful anomaly in modern civilization’.Footnote 94

Accounts as Explicit and Implicit Disclosure

Not all organisations were as bold as one Irish relief committee that claimed, in 1849, it had saved ‘probably 100,000 human beings’ with the sum of £5,485 it had raised.Footnote 95

The broadest adoption of accounting practices took place among Catholic institutions. The Church continued to utilise occasional letters circulated within its hierarchy, while contact with parishioners would take place from the pulpit. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, print media, on the one hand, and voluntary associations such as the SVP, on the other, represented an emergent culture of continuous reporting and transparency. Collaborative undertakings also enhanced open bookkeeping. Thus, while traditional trust-based modes of select accounting for charity persisted, they were (a) qualified by individual office holders; (b) supplemented by the contemporary review-based procedures of civil society; and (c) modernised by double-entry bookkeeping. Modern Church-affiliated organs and organisations also played a major role in documenting the voices of recipients and first-hand observers.

As various secular US relief campaigns show, even within civil society, there were marked differences in accounting for relief efforts. Notes posted in newspapers were standard, but some of the more significant regional organisations also published final reports or field mission documentation. The information presented varied considerably across cases. The report of the Dublin Quaker Committee appeared at a time when the famine had drawn to an end, in contrast to other final reports that were issued after the relief effort had prematurely ended. As most US relief was distributed by the Dublin Quaker Committee, their extensive documentation provides considerable insight into how resources and monies were deployed in practice.

While in a formal sense the BRA was a part of civil society, in reality it was a non-governmental organisation (NGO) commissioned by the UK government and intended to function as a form of quasi-colonial rule in Ireland.Footnote 96 The BRA thus illustrates the striking discrepancy between meticulous British public or semi-public accounting for relief (including solid and multifaceted statistical aggregates), and the complete absence of official or otherwise reliable mortality statistics of more than a fragmentary character. Among providers of relief, the BRA was also unique for its total exclusion of recipient voices and the degree to which its appeals relied on accounting – including advertising its auditors’ functions and names. The emphasis on reliable procedures, rather than compassion, reflected the a priori absence of trust in British–Irish relations. For Trevelyan, who was the acknowledged mastermind of official and semi-official famine relief, accounting for the provision of aid also became a means of relinquishing it in the future, with all due civilisational and Christian honours preserved. In the case of the BRA, morality became a de-humanised abstraction exclusively invested in the prevailing ultraliberal market economy, rather than in an equalising force that would uphold the dignity of human life.

5.3 The Power of Numbers: Soviet Russia

Supporters as well as critics of relief to Russia regularly demanded detailed information about incomes and expenses, purchasing practises, overhead costs, and the like. The lack of trust in Russian authorities and the promise of businesslike relief, but also the competition between different aid organisations, made professional bookkeeping a necessity. Accordingly, in the spirit of organised humanitarianism, relief workers were exhorted to rather ‘not … issue supplies than to issue them and be unable to account for them’.Footnote 97

Accounting was hampered by the difficulty of finding Russian personnel who were qualified for this task according to Western standards, and many local relief districts proved incapable of supplying central offices with adequate commodity reports, or they prioritised other tasks that they considered more urgent.Footnote 98 The steep currency depreciation in Russia – adding machines were soon unable to handle the high figures – led to further complications.Footnote 99 The Russian division of the American Relief Administration (ARA), which exchanged approximately US$650,000 for Russian roubles between 1921 and 1923, rejected the rates offered by the Russian government, saying that they would ‘practically amount to the confiscation of a part of our money’.Footnote 100 Until Russian banks agreed to extend market prices, the ARA bought the roubles needed to cover operating expenses from private individuals who happily accepted dollars or pounds in their foreign accounts.Footnote 101

Statistics regarding foreign relief provided under Hoover’s direction from 1914 to 1923 shows that the Russian operation was a minor endeavour, standing for 1.2 per cent of the total budget.Footnote 102 Belgium received nine times that share between 1914 and 1919, and after the war the former enemy Germany received nearly twice as much. Excluding the massive supplies sent to France, Great Britain, and Italy, and taking into account only the so-called reconstruction period between August 1919 and July 1923, the ARA’s aid for Soviet Russia comprised little more than one-third of the total tonnage.Footnote 103 Nevertheless, the ARA was the dominant force among those organisations providing Russian relief. It distributed 740,000 t under its umbrella, whereas the International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR) and its affiliated organisations, according to its own reports distributed up to 90,000 t, and the Workers’ Relief International (WIR) claimed to have distributed 30,000 t (see Table 5.3). At the same time, the relatively limited magnitude of relief for Soviet Russia does not diminish its practical and symbolic significance as a major instance of enemy aid, and as an engagement that facilitated a working relationship between the West and the victors of the Russian revolution in the early interwar period.

Table 5.3 Quantity of relief goods distributed, and available budget during the Russian Famine, 1921–3.Footnote 106

| Relief goods, tonnes | Total budget (incl. overhead and gifts in kind), US$ | |

|---|---|---|

| International Committee for Russian Relief and affiliated organisations (Save the Children Fund (SCF), International Save the Children Union, Friends’ Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee (FEWVRC), various national Red Cross organisations, various smaller groups) | 90,000 (of which c. 40 per cent was distributed by SCF and 20 per cent by FEWVRC) | 7,100,000 |

| Workers’ Relief International/Internationale Arbeiterhilfe (nearly a dozen national organisations, Friends of Soviet Russia (USA) raising more than half the budget) | 30,000 | 2,500,000 |

| Relief under American Relief Administration direction | 740,000 | 63,000,000 |

| By source: | ||

| American Relief Administration | 10,200,000 | |

| Congressional Fund/Medical Fund | 22,660,000 | |

| Food remittances | 9,300,000 | |

| Jewish Joint Distribution Committee | 5,000,000 | |

| American Red Cross Medical Fund | 3,800,000 | |

| Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial | 1,300,000 | |

| Soviet gold | 11,300,000 | |

| Other contributors include: Catholic Welfare Council, Lutheran Council, American Friends Service Committee, Young Men's Christian Association/Young Women’s Christian Association, Mennonite Central Committee, Volga Relief Society | ||

| Estimated Russian contribution in form of transport, infrastructure, etc. | – | 14,000,000 |

| Total | 860,000 | 86,600,000 |

Organisations all desired to keep costs for personnel and administration low. The ARA instituted a hire-and-fire policy whereby staff could be laid off with one month’s notice when their services were no longer needed.Footnote 104 Overhead costs – especially their public relations aspect – were a sensitive topic that led to heated debate and controversy. Relief organisations faced the difficult task of justifying their practices and expenditures, such as placing advertisements.

The sources and effectiveness of famine relief were also contentious matters and involved ideological pride, particularly between the ARA and Soviet authorities. In the resulting information war, both sides resorted to arguments partly based on ‘creative accounting’. The political circumstances of enemy aid, combined with social expectations that both the public and individual donors held in connection with transnational aid, made gratitude an important element of the accounting genre.Footnote 105 Evidence in the form of reports, photos, films, gifts, and letters of thanks became an alternative return currency within the humanitarian moral economy. Different organisations, and even countries, struggled to receive their share – something that often led to conflict.

Hoover attached paramount importance to securing the ‘national portion’ of gratitude. Even when co-operating with foreign organisations, the ARA considered it a ‘fundamental principle’ that relief coming from the USA had to be ‘distributed as American food’, and that recipients needed to understand its origin, which caused some problems. For example, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) used to co-operate closely with the British Quakers and had initially appointed one of them as its head of mission. The ARA did not understand the Friends’ ‘reluctance and opposition to letting it be known that the relief which they give emanates from America’.Footnote 107 At the end of the relief campaign, the ARA proudly stressed that relief given by its affiliated organisation to Russia ‘outside the resources of the ARA, has amounted to over twice the total relief given to Russia by all other foreign relief organizations’.Footnote 108 In an interim report, Hoover even listed the contribution of US communist organisations.Footnote 109

The British Save the Children Fund (SCF) also increasingly emphasised the national origin of relief aid. Unlike the previous Budapest effort in which International Save the Children Union (ISCU) money was pooled, in Russia it was determined ‘that separate kitchens shall be maintained with the money received from different countries’. Each national group ‘should reap the full credit which its sacrifices and generosity deserve’, an article in The Record proclaimed.Footnote 110 Consequently, despite the ISCU’s involvement and the contributions of chapters from other nations, the provision of food in Saratov was often described as the ‘generous effort of the British people’.Footnote 111

Considering the circumstances under which relief was provided, official statistics seem to understate losses and damages. The ARA claimed that the cargo shortage reported at the five main Soviet ports of Petrograd, Batumi, Novorossiysk, Odessa, and Theodosia was less than 0.5 per cent, while financial losses from damaged goods made up an average of 1 per cent of the value. During transit via trains, trucks, and interior shipment another 0.5 per cent of the cargo (less than 4,000 t) was reported as loss.Footnote 112 The British relief expert Robertson came to a similar conclusion during his trip through Russia in early 1922, estimating that losses during train transport amounted to approximately 0.5 per cent.Footnote 113

According to §11 of the Riga agreement, the Soviet government was to reimburse the ARA for ‘any misused relief supply’, including shortages during transport.Footnote 114 By March 1923, the ARA had made 1,429 such claims, ‘supported by copies of ten thousand protocols’, totalling a sum of roughly US$300,000. Although there was no similar formulation included in the agreement Nansen had signed on behalf of the ICRR, British organisations assumed that Soviet authorities would compensate them for any shortage and submitted demand notes accordingly. Thus, the Soviet government was held responsible for losses on its territory, if not always financially, then morally and politically, and therefore found it in their own interest to prevent such incidents as far as possible. Many trains were under military protection, trucks and rail cars were sealed, and convoys partly accompanied by a special ‘ARA regiment’ of the Red Army. Warehouses in the cities ‘were kept under continuous guard and under lock and seal when closed’. The feared secret police, Cheka, succeeded in February 1922 by the State Political Directorate (GPU), proceeded with rigor against any suspicion of theft, embezzlement, or diversion. For example, Cheka officers took samples of relief goods and made sure similar items were not being sold in local markets. By early 1922, the SCF had reported only four attempts to break into one of their 400 warehouses. The ARA likewise mentioned ‘only few robberies of much importance’ during the whole course of their operation, and blamed ‘petty pilferage and leakage’ for the major part of their losses.Footnote 115

Businesslike Relief and Overhead Costs

In December 1921, Hoover’s associate Rickard, like Hoover a mining engineer, stated that the ARA’s ‘governing principles’ were the same as those of US engineering companies.Footnote 116 In the Riga negotiations, the ARA stipulated such conditions to the Russian government as had been given to countries that had previously received aid. This meant that the only costs for the ARA in Russia were the maintenance of US staff and the expenses related to the Food Remittance Division (including salaries for native personnel), as the latter was considered an enterprise–charity hybrid.Footnote 117 The Soviet government covered all internal costs connected with the child and adult feeding operations, such as the salaries of personnel cited earlier, travel expenses, kitchen and office equipment, and transport.Footnote 118

In addition, the ARA staff remained small, comprising some 200 members at a time, supervising a body of about 125,000 local workers.Footnote 119 This kept administrative overhead costs low and was intended to stimulate self-initiative and responsibility, crucial elements of the ARA relief philosophy.Footnote 120 When smaller affiliated organisations wished to send their own representatives to Russia, it was regarded as a waste of money. Haskell cabled that the ‘maximum amount of good could be accomplished’ if unnecessary expenses like this were avoided.Footnote 121 The ARA considered the performance of other organisations inefficient, with few exceptions. A letter to potential donors stated that contributions were best invested in the ARA relief operation, as most other agencies worked in ‘uneconomical’ ways. At best, they were ‘well-intended and wasteful’, at worst, ‘dishonest and wasteful’.Footnote 122

For the SCF, nineteen British citizens supervised a native workforce of 5,000.Footnote 123 The SCF also stressed professionalism and formulated three aims for its relief work: ‘1. To get the food to the children; 2. To feed the children as economically as we can; 3. To feed as many children as we can.’ Thus, they mirrored the ARA’s goal of making every dollar provide the maximum relief. Compared with such goals, spontaneous charity appeared as an outdated model. Given the enormity of the Russian famine, the SCF stressed that there was ‘little room for the amateur philanthropist’. For this reason, they discouraged potential donors from giving their money to other organisations: ‘We are better fitted to deal with child relief than anybody else… It would be false modesty if we did not claim to have expert knowledge and to assert that charity if it is to be of any use at all must be conducted on efficient businesslike lines.’Footnote 124

The examples show how accounting for aid and fundraising were intertwined. Low overhead and minimal purchase costs were extensively used in public relations work. The ARA proudly claimed that ‘not one cent … has been expended for internal overhead’; the AFSC promised that every dollar ‘will be turned over without one cent deducted by us’; and the communist Friends of Soviet Russia (FSR) assured donors that ‘experts in purchasing and shipping’ will ‘make every cent you give buy its utmost in value’ by purchasing food ‘at rock-bottom prices’.Footnote 125 Meanwhile, the SCF was ‘carefully watching the world’s markets’ and ‘buying on very large scale’.Footnote 126

However, even businesslike practices made humanitarian organisations vulnerable to criticism. Its countrywide advertisements caused the SCF to face allegations that it was spending a great deal of the donated money it received on public relations instead of famine relief.Footnote 127 A lengthy article in The Record addressed this issue and informed readers that the aim of the SCF was ‘to collect and distribute the largest possible amount at the smallest expense’. Old-fashioned fundraising based on personal contact and a network of regular donors was no longer adequate. In the face of urgent need, the SCF took ‘the bold step of advertising on a large scale, proclaiming to the world what it was doing and why it was asking for help’. Readers were assured that ‘advertising pays’ and that experience had shown ‘money drops off’ without advertising.Footnote 128

In December 1921, £10,998 spent on advertising yielded £61,115 in donations.Footnote 129 While the net profit in this example may appear impressive, 18 per cent overhead costs for public relations may appear less acceptable within a moral economy context, especially if compared to costs incurred by smaller organisations. In justification of the SCF position, Treasurer Watson later argued ‘that the larger the sum which a society sets itself out to raise, the greater must be the proportional expenditure’. It was easy, he continued, to raise £1,000 by spending £100, but to achieve the same ratio when raising £500,000 was practically impossible.Footnote 130 However, the question remained as to what degree the increase of total relief was legitimate in the eyes of a critical public, if it caused a disproportionate rise in overhead costs.

This Achilles’ heel of businesslike humanitarianism was soon attacked by adversaries of the SCF. Among them, the Daily Express, with its wide circulation, fought an aggressive campaign against the SCF’s Russian operations. After unsuccessfully spreading doubts about the existence of the famine, its journalists began criticising SCF’s overhead. One of the newspaper’s first headlines read, ‘One Pound in Three Goes in Expenses’. Although this statement was factually wrong, it touched a sore point.Footnote 131

To cope with such accusations, the SCF adopted an offensive strategy and allowed the Daily Express to access its documents. The investigative journalists could only report that in the course of the two and a half years of its existence, the SCF had collected £1,115,000 and spent £204,000 on expenses, that is a moderate overhead rate of slightly more than 18 per cent.Footnote 132 Furthermore, the SCF tried to demonstrate how reasonable its overhead was by drawing comparisons with other British relief organisations. As articles critical of the SCF often referred to the Quakers as shining examples, the Friends’ Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee (FEWVRC) was involuntary drawn into the conflict. SCF representatives analysed their balance sheets and pointed out that the Friends’ overhead rate was 19.5 per cent for the period September 1918 to September 1920 – higher than that of the SCF.Footnote 133 Chairwoman Ruth Fry, in turn, protested against such publicity and justified the Friends’ overhead costs by explaining that they administered the distribution of many goods supplied by other organisations. While such distribution involved overhead costs, the relief goods themselves did not necessarily enter the credit side of the Quakers’ accounts. For this reason, Fry claimed, and because of their service-intensive programme of medical aid, ‘any comparison of the overhead expenditure of the two Societies must of necessity be fallacious and misleading’.Footnote 134 Watson replied that he was not criticising the Quakers’ expenditure, but simply wanted to show ‘that no big charitable work can be carried on nowadays except on very considerable costs’.Footnote 135 In a second letter, he pointed out that ‘we did not start these comparisons and would not have troubled to make them had it not been for widespread criticisms of our work which are largely based on an alleged extravagance in our overhead expenditure and, on the other hand, underestimates yours’.Footnote 136

While the SCF successfully repelled the first wave of attacks, the Daily Express raised another criticism, once again connected to the professionalism the SCF claimed to have embraced. Similar to profit-making companies, SCF’s public relations campaigns were partly conducted on a commission basis, something that became public when journalists scrutinising SCF accounts noticed that an unnamed agent had received £10,000 as a commission fee. SCF representatives defended the sum by referring to the conditions under which that person had led the fundraising campaign: £8,000 per month were to be raised free-of-charge; everything beyond that earned the agent a 1.5 per cent commission. SCF argued that the fee was high because the campaign was effective and justified the bonus system: ‘We distinctly do not believe, as many people do, that such business can safely be entrusted to amateurs with no business experience.’ For this purpose, ‘first-class business people’ were engaged to bear the responsibility of organising a fund exceeding one million pounds. These people were said to earn far less than they would elsewhere.Footnote 137 Nevertheless, local SFC fundraisers were also upset, demanded explanations, and some threatened to stop working unless such commissions were made public.Footnote 138