Despite the heavy criticisms that have been launched against the concept of “meme” ever since its inception by the zoologist Richard Dawkins (Reference Dawkins1989) concerning the attempt at drawing tenuous analogical relationships between cultural and biological phenomena and discourses, as well as insofar as memetics “says very little about the politics of social power” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 74), it still constitutes a useful heuristic for interpreting how cultural phenomena emerge, propagate, and perish, but also a robust conceptual platform for quantifying the extent and rate whereby messages propagate virally, as well as their life cycle. Furthermore, there is ample research evidence (e.g., Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Shankar, Elliot and Canniford2009) that speaks for how linguistic and, more generally, multimodal signs that are communicated in discourses such as advertising, attain to colonize ordinary language by spreading mimetically.

According to Dawkins’s original conceptualization, “genes have only one purpose in life, to replicate themselves. As a by-product of this continuous replication, life also produces its multifarious individual phenotypes” (Kilpinen Reference Kilpinen2008, 218). By analogy to the role performed by genes in the evolution of natural organisms, Dawkins postulated the meme as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation. … Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation” (from Dawkins’s 1976 edition of The Selfish Gene, as cited in Nöth Reference Nöth1990, 166; also see Danesi Reference Danesi2009, 195, and Grant Reference Grant1990). In our case the “ice-bucket challenge” constitutes a meme, and more specifically a video meme (Shifman Reference Shifman2011), as multimodal unit for cultural analysis (further decomposable into subunits) that is as a filmic unit with various identifiable sequences comprising profilmic expressive elements, such as manifest discursive actorial figures (e.g., Tom Cruise, Bill Gates, George Bush, Eminem, Stephen Hawking) who produce performatively in their utterances one or more cultural representations by drawing on one or more semiotic modes, such as kinetic, lexical, visual, and musical (as will be shown in greater detail below). Let it be noted that when we refer to “culture,” a multifariously defined and heavily abused concept, Hall’s (Reference Hall and Hall1997) definition is endorsed as shared meanings among the members of a community. According to Hall (Reference Hall and Hall1997, 4) the representations that are carriers of meaning in a culture assume meaning by virtue of common cultural codes that are shared by the community’s members. However, in order to streamline the analysis of the concerned video meme with the employment of sign-oriented terminology that is recruited both in the analysis of the formal structure of the message, as well as in the exploration of its ontological structure, I am employing the term “cultural sign” in lieu of “cultural representation” (but in any case, “sign” was used interchangeably with “representation” or “representamen” in Peirce’s original triadic semiotic typology; cf. Nöth Reference Nöth1990). The adoption of a sign-oriented terminology also highlights the significant overlaps in the modes of address of cultural phenomena by the discipline of semiotics that antedated memetics and by the newly emergent discipline of memetics. Deacon (Reference Deacon1999) was quite explicit and emphatic about this intricate relationship between memetics and semiotics: “Memes are signs, or more accurately, sign vehicles. … Signs are concrete things, or events, or processes and they have been categorized and studied systematically for centuries. Memes are thus the subject of a body of theory called Semiotics!” “Were Peirce around today to hear what the meme scholars have to say, he would not just answer that they are reinventing his old wheel. He would add that the newfangled meme is an underdeveloped special version of his concept of sign. Why so? Because memetics, with its notion of universal replication, recognizes only one of those dimensions that constitute signs, according to the general theory. It is aware of the interpretive dimension, but has little if anything to say about the representative dimension” (Kilpinen Reference Kilpinen2008, 221). A similar conclusion regarding the relationship between semiotics and memetics was reached by Maran (Reference Maran2003, 211) who went on to add that “for semiotics the problem of mimesis raises questions about the formation of new structures by semiosis as well as the development and changeability of semiotic systems.”

Memetics as the artful science that accounts for how cultural life is predicated on the emergence and propagation of memes has been endorsed by marketers in an attempt to understand and plan for message strategies in a networked economy where new media and communication vehicles such as viral marketing (or “eWord of Mouth”) by now constitute a mainstay in integrated marketing communications plans. Memes have been tagged by Godin (Reference Godin2000) in marketing language as “ideaviruses,” namely, fashionable ideas that propagate through discrete target groups, changing and influencing everyone they touch. The proliferation of cultural representations or cultural signs by end users as the outcome of widely accessible technological means has been coupled with a shift in media studies from theorizations that assume a centralized outlook to the production of cultural representations (e.g., media conglomerates) toward progressively decentralized approaches that revolve around the power of individual consumers to kick start and propagate cultural trends and fads. We are concerned with an economy of signs, where, once produced, they assume a life of their own, while their life cycle eschews the control of a centralized planning team. This cultural predicament is particularly demanding not only as regards the typology of media representations that are produced, but, moreover, how such representations propagate.

This mode of propagation abides neither by linear models offered by cognitive psychology that attempt to account for how messages are memorized by starting from simple attention and culminating in storage in episodic memory, nor by semantics, which seeks to unearth the invariable structure beneath haphazard semiotic constellations. Messages in a networked economy are occasionally valorized provisionally not because of their consonance with an organic axiological framework and their ability to sustain belief systems, but because of their sheer “fascination” and their ability to foster bonds among members of ephemeral networks (either online or offline). In this context, the value of signs is not dependent on their exchangeability for a semantic content, but on their pragmatic outcomes in terms of consolidating bonds among community members. This predicament does not posit affect as an enabler for deeper cognitive processing, but rests with subconscious affective processes as responsible for the valorization of signs. This reorientation in the relative contribution of affect to the sustenance of affective and imaginary communities calls for theorizations on the memetic potential of cultural signs, in which case signs are tantamount to memes as minimal units of cultural reproduction.

Now a crucial distinction between genes and memes is that, whereas the replication of the former is evinced in an identical reproduction, the cultural reproduction of memes allows for mutations, or differentiation of the expressive inventory of memes as they pass along from host to host, without, though, losing sight of invariable elements that allow for the assignment of a meme to a particular type (in which case memes display similarities with the classic linguistic model of “type”/”token”). Yet, this variation or what may be termed in cybernetic lingo “memetic oscillations” is enacted performatively within bounds as a set of semiotic constraints that determine to what extent a meme’s components may deviate from a set of invariable expressive elements that would waive their recognizability as partaking of a specific type and, hence, of the possibility of ascribing the status of replicability or reproduction.

In other words, if a culture is reproduced mimetically, then we must at least be capable of accounting formally for the structural components of memes prior to laying claim about their propagation, their life cycle (Bjarneskans et al. Reference Bjarneskans, Grønnevik and Sandberg2011), and their mortality rate (Bouissac Reference Bouissac and Deely1992). To this end I am proposing that memes should be viewed as structural gestalts that allow for their recognizability by virtue of semiotic constraints in the form of an invariable inventory of expressive elements.

The second point that sets apart memes from genes consists in the fact that the former are not a positivistic construct, but a rhetorical one, a neologism that allegedly (i.e., based on Dawkins’s [Reference Dawkins1989] own assertion) instantiates the formal structure of a pun (being related to memory and the French word même, denoting “same”). I would like to emphasize this perhaps “marginal” reading of the term “meme” insofar as it points quite lucidly to the rhetorical mission of memes as responsible for maintaining an imperial structure of the Same by short-circuiting the cognitive elaboration of the components of a message structure in favor of affectively loaded multimodal signs that aim at subduing memory under the mandates of a memetic ethos or a culture made of memes. Memes do not demand critical engagement of their hosts, but prereflective, unconscious propagation, a point that will be further elucidated below. A most striking example of such unconscious propagation of memes, as argued by Heylighen (Reference Heylighen1998), is the memetic adoption of hand gestures, but also, as eloquently demonstrated by Blackmore (Reference Blackmore1999), of belief systems, including religion.

The life of a meme is dependent on the suspension/interruption of the mind’s critical faculties. Insofar as this call issued by the meme would be unbearable to the defense mechanism of the ego, given that the homeostatic stability of a self is incumbent on a preconscious and conscious regulation of threatening presentations and representations—but also, and even more importantly, affects that emanate from the unconscious—the reproductive success of memes rests with putting the mind to sleep, with sedating it and hence with bypassing rational calculation that depends on the subsumption of the components of a meme under a propositional calculus with view to discerning its truth value or pragmatic value. “Memes (just like genes) exist for their own benefit” (Kilpinen Reference Kilpinen2008, 219). This point that is central to the argumentation that is pursued in this article will be addressed in greater detail below with regard to Sampson’s (Reference Sampson2012) revival of Tardean sociology and the coinage of the “virality” perspective that offers, in some respects, a more nuanced understanding of how memes propagate in the current networked economy of signs.

In the light of these introductory arguments that hopefully facilitate the reader to navigate the “epidemiological space” of memetic culture and its “epidemiological representations” (Sperber Reference Sperber1985), as will be mapped out with regard to the ice-bucket phenomenon throughout this article, the next section describes the formal structure of the ice-bucket message, prior to proceeding with unpeeling its communicative function or its role as unit of cultural reproduction. In this case, we are not concerned with the identification of a “cultural code” and the meaning of cultural representations, but with the effects of multimodal memes (signs) on linguistic community members and with the extent to which discernible pragmatic effects are driven by a need for and are conducive toward the consolidation of ephemeral networks of hosts, regardless of the meaning of signs. In short, what is of greater value in a meme—so goes the fundamental hypothesis that is put forward in this article—is not its meaning, but its relational value in effecting preconscious bonds among network community members. “Effectively, the repetition of imitation becomes the infinitesimal rhythm of social relationality, triggered by the desire-event” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 24). This relational function, which is also effected through the usage of “empty signifiers” in populist discourse (see Laclau Reference Laclau2005) or “empty signs” as viral memes that circulate online and whose function is conviviality plain and simple (Varis and Blommaert Reference Varis and Blommaert2015) or what has been eloquently termed by Heidegger (Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson[1927] 2001, 211–13) idle talk, is brought about by “memetic tricks” (Blackmore Reference Blackmore1999, 193). Memetic tricks constitute a complex of mutually supporting memes or what the author calls a “memeplex” (Blackmore Reference Blackmore1999, 86), rather than a set of rational propositions.

What was the trick in this case? As reported by Conner (Reference Conner2014), “the campaign engaged something deep enough in the psychology of enough viewers that millions of people moved one step closer to donating than before. This phenomenon is known as ‘successive approximations’ or the-foot-in-the-door technique.” “Blackmore’s goal is ultimately to expose the illusionary paradox of the conscious self ‘in charge’ and ‘responsible’ for individual action in the face of a barrage of autonomous, self-propagating memes” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 74). This shift in favor of relationality pure and simple has also been cited as a fundamental value of the networked society: “Relations themselves are getting more important at the expense of the elements or units they are linking” (Van Dijk Reference van Dijk2006, 37). At the same time, the preponderance of the relational value of memetic communication opens up the function of a video meme’s formal structure to an ontological dimension, as will be shown below, by drawing on relevant concepts from Heidegger’s fundamental ontology. Let us recall that Heidegger’s original conception of the sign entailed a purely relational dimension: “A sign is a universal structure of relation” (Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson[1927] 2001, 107–8).

In anticipation of what follows, the potential value of a meme for network members is not incumbent on the meaning of its component signs that may be decoded based on salient cultural codes, but rather on the illocutionary force of the interaction of signs in structural gestalts in the context of multimodal performative utterances.

Deconstructing the Formal Structure of the Ice-Bucket Challenge Video Meme

The ice-bucket challenge was described as the “Harlem Shake of Summer 2014” by Mashable, the first of its kind, as regards the social media counterpart of similar challenges that had been undertaken in the past and most probably not the last.Footnote 1 The ice-bucket multimodal meme or, rather, memes—since we are concerned with a series of variations on a basic theme—are particularly noteworthy and merit addressing as a special case for various reasons.

First and foremost, they have not been generated by random new media end users, for example, by user-generated content, such as memetic videos (Shifman Reference Shifman2011), or by user-generated advertising (Rossolatos Reference Rossolatos2014c). On the contrary, the participants in this virally deploying signifying chain constitute the pinnacle of a global cultural nexus: they are “cultural mediators” (in Bourdieu’s Reference Bourdieu1993 terms) spanning all sectors of the economy (media and entertainment, politics, software development, science, sports) of the highest visibility and ranking. Second, even though the majority of those who were challenged responded positively to the call of their peers to engage in the exponentially augmenting memic spectacle, only a small fraction of those who accepted the challenge donated to the charitable cause that seems to constitute an addendum to the task this meme is summoned to accomplish. “A whopping 26% of participants didn’t even mention ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis] in their videos, and only 20% of participants mentioned donating money at all” (Conner Reference Conner2014). Third, there doesn’t appear to be a centralized coordinating team that is moving this viral semiotic chain, in exactly the same fashion that memes deploy, as discussed above.

These crucial differences that set apart the ice-bucket phenomenon from random user-generated content in the context of a technologically enabled participatory culture (Kirby and Marsden Reference Kirby and Marsdenl2006; Tuten Reference Tuten2008; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2009; Wiggins and Bauers Reference Wiggins and Bowers2014) pose particular interpretive challenges for media and cultural studies. The explanation offered here favors an ontological approach in an attempt to justify the magnitude of this memetic spectacle that exceeds the boundaries of a short-lived fad and cuts straight through the very heart of a cultural machine in the context of a networked economy. But before proceeding with the display of the ontological importance of this phenomenon and in order to anchor as succinctly as possible the argument in concrete signs that make up the edifice of this multimodal meme, it is prudent to begin with a sketch-map of its formal structure.

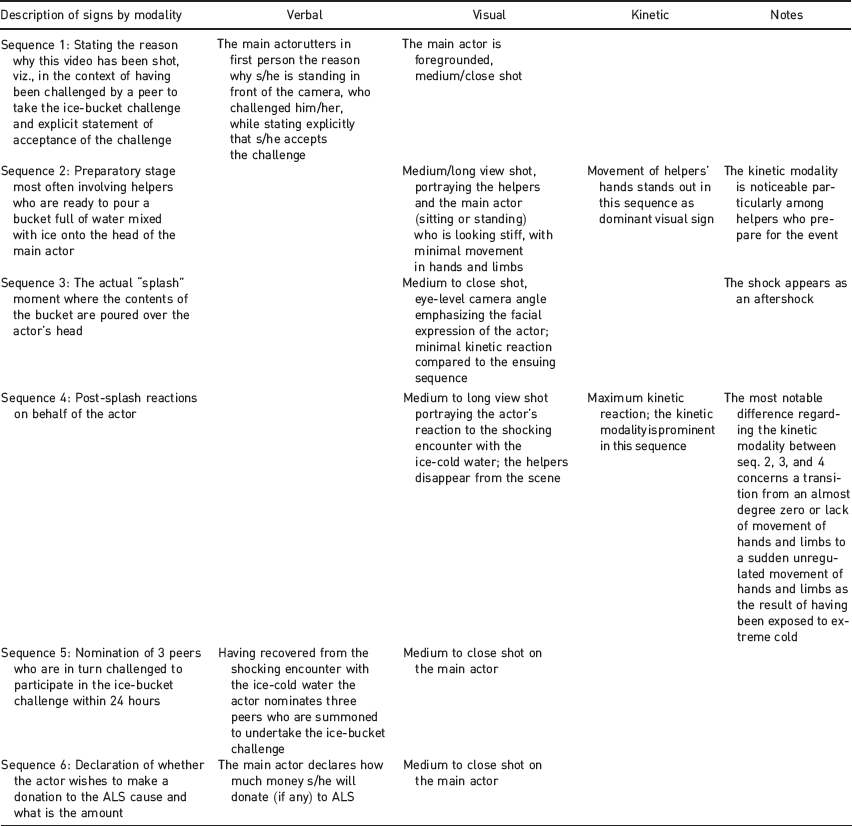

As a preparatory stage to the actual analysis of the formal multimodal structure of the featured films,Footnote 2 a sample of 250 ice-bucket challenge videos was screened in order to obtain a primary feel for the invariant expressive elements that are encountered as common denominators across the entire corpus. The videos were selected from YouTube.com, which constitutes the most popular destination for watching, downloading, and spreading the concerned videos. As soon as this initial screening was complete, I proceeded with a systematic recording of the key signs that are invariably encountered across the filmic corpus, while classifying them by modality (verbal, visual, kinetic). Given that the involved modalities consisted almost invariably in these three categories, they were subsequently employed for classifying the typical film or mimetic video or multimodal meme of which individual instantiations constitute tokens, or replicas. Additionally, the typical meme was split into sequences, in order to allow for more focused and nuanced analyses. The above procedure culminated in the sequences/modalities as portrayed in table 1.

Table 1. Sequences/Modalities/Signs Making Up the Structure of the Typical Ice-Bucket Challenge Video Meme

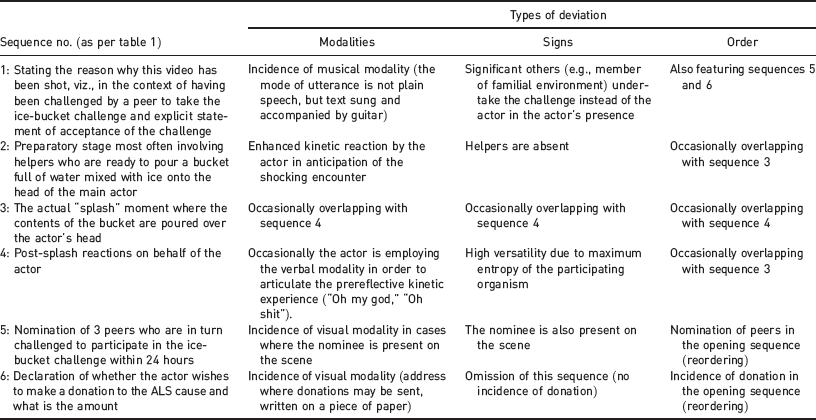

The mapping of the transition between sequences in terms of modalities displays an invariant preponderance of the visual/verbal modalities in the first and last two sequences, whereas in the intervening sequences 3 and 4 a preponderance of visual and kinetic modalities. This differential pattern in the incidence of the involved signs’ modalities is indicative of a more direct (with the end viewer) communication of the actors’ encounter with the shocking event of ice-cold water pouring over their heads, marked by an almost complete absence of the verbal modality. The climax of the meme, its experiential apex, is articulated in nonverbal signs and, hence, is represented (insofar as each video constitutes a replica of an original script) as a raw, prereflective encounter with a shocking event. This encounter will be further qualified interpretively below. For the time being let us proceed with a display of some deviations (table 2) from the invariant expressive inventory of the video meme (table 1), in terms of signs and modalities.

Table 2. Expressive Deviations by Sequence/Modality/Sign Encountered in Replicas of the Video Meme

The above multifarious variations in terms of modalities, signs, and ordering of the involved sequences are affirmative of the key difference between memes and genes, as discussed above. This meme as a performative enactment of a multimodal language game of cultural reproduction allows for modifications of its surface structure without affecting the invariant elements that are constitutive of its essence. For example, Stephen Hawking brings his family into play who take the challenge instead of him for purely practical reasons; George Bush’s performance is interrupted by Barbara Bush, who undercuts the donation in favor of a pursuit of her own grooming goals; Tom Cruise’s performance repeats the ice-cold shower over and over. Nevertheless, beneath these variations an invariant memic structure is discernible that allows us to proceed with the interpretation of the function(s) of the ice-bucket meme.

Interpretation of the Function(s) of the Video Meme as Exchanges in a Structural Edifice

“Much of the work of representation depends on first having established relationships of equivalence” (Webb Reference Webb2009, 10): a sign for a concept, a memory for an absent or imaginary event or state-of-affairs, and so forth. The same holds for how meaning emerges from the interplay among the signs that make up the multimodal meme or video meme, in our case. The meaning of the cultural representation is construed through multiple acts of exchange/equivalence among individual signs or sign constellations and the concepts to which they give rise. The function of the video meme is incumbent on communicating to its hosts the meaning that emerges from the cultural representation that is formed within its expressive contours.

Let us attempt to reconstruct this meaningful mimetic experience in the context of the ice-bucket challenge in the light of the formal structural elements of the message that were identified in the previous section, while pointing out their function on both ontic and ontological levels (Heidegger Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson[1927] 2001, 117) by drawing on Heideggerian fundamental ontology. The primarily ontological function of viral communication has been emphatically noted by scholars in the new media literature (e.g., Sampson Reference Sampson2012), albeit not qualified by recourse to an ontological theory. In an attempt to unearth the ontological dimension of viral communication as succinctly as possible, I draw on Heidegger’s fundamental ontology, while unpacking its ontological conceptual armory from its hermetic folds and rendering it as closely relevant to the interpretive endeavor at hand as possible. In these terms, the ontic level is the level of determinate beings or cultural artifacts toward which “Dasein” (or the subject as ec-sistence [being there], according to the terminology of Heidegger’s fundamental ontology) is comported in its ordinary involvement in the world alongside others. The ontological level concerns Dasein’s relationship to Being or culture as totality (system) of signs or artefacts (from a culturological point of view) that functions as fundamental presupposition for the ec-sistence of Dasein in terms of an open semiosic horizon wherein Dasein may actualize its possibilities-of-Being. The relationship between these two mutually presupposing levels (ontic/ontological) is evinced most eminently in Heidegger’s distinction between the “indexicality” and the “reference” of signs ([1927] 2001, 107–14). Signs as indices concern the facticity of Dasein, that is, its concrete relations with objects, events in the world to which it may point determinately. The ultimate referential ground to which such indexical acts point is Being as those acts’ ontological substratum. The discovery or knowledge of a determinate object or event in the world is dependent on Being as totality of involvements (yet, an absent totality that appears alongside our knowledge of and involvement with determinate beings and never as such). This conceptualization of Being may be likened to Saussure’s conception of langue as the linguistic system that is presupposed by parole or acts of speaking but never appearing in its totality within parole.

The key argument that I wish to put forward is that the key message of the ice-bucket challenge concerns the very mode of propagation of messages in a networked society where mandatory connectivity has been catapulted to a nouveau ideologeme. This mode is evinced in the video meme under analysis here, as a signifying chain comprising potentially infinitely replicable cultural memes as minimal units of cultural reproduction. The emphasis on mode as the kernel of a message structure urges us to effect a radical reorientation from medium to mode and to boldly declare, while paraphrasing McLuhan’s infamous dictum, “the mode of propagation is the message.” “Whether the message is a text, an image, or a video is of lesser importance since the medium is merely the substance that the idea lives in” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 72).

By attending more closely to the structuration of this video meme in terms of the interaction among the signs that make up its structural edifice and with reference to the typical film’s segmentation as portrayed in table 1, we notice primarily that the climaxing sequence 4 (or 3, in replicas where the two sequences appear to be overlapping; cf. table 2) institutes within its expressive contours a shocking (although not accidentally so) experience undergone by a celebrity, that of the encounter of the body (and mainly the head) with extremely cold (ice-cold) water. This is an act of suffering, and at the same time of autopathic communication. Just like in the case of an autopathic disease,Footnote 3 where the disease is dependent on the structure of the diseased organism, the contagious intrusion of the meme into the host’s life-world establishes a communication that is dependent on the host’s unique memic adoption and propagation potential. The addressee of the action that is portrayed in the concerned sequence is the actor himself, albeit also involving in an indirectly participating fashion as addressee the end viewer who becomes part of this autopathic communicative predicament by sucking in mimetically the actor’s reaction that springs from the encounter with the shocking event. And the fact that the climaxing sequence is evinced in a visual/kinetic mode, in marked absence of the verbal one, suggests a higher likelihood of this meme’s passing on to the viewing hosts prereflectively and hence more directly compared to its alternative mode of propagation that would also feature the verbal mode. Let us recall, as Sampson (Reference Sampson2012, 78) notes, that “memetics treats social encounter as the passive passing on of a competing idea. By attributing this level of intentionality to the fidelity, fecundity, and longevity of the meme itself, the theory crudely consigns the by and large unconscious transmission of attitudes, expectancies, beliefs, compliance, imagination, attention, concentration, and distraction through social collectives to an insentient surrender to a self-seeking code.”

The meaning of the different signs that make up this multimodal meme as emerging in the context of their embeddedness in a structural gestalt may be reconstructed as follows. As regards the employment of ice, first we note that ice interrupts cognitive processing, while opening the subject through shock to enhanced suggestibility. Then, the representation of an ice-cold shower functions as an enhancer of the legitimacy of memes as units of cultural reproduction as scripted (but not necessarily coded) sequences. Representation involves repetition of something that has already become a “dead form,” that is, the meme as minimal unit is a dead form awaiting to be hosted by agents of cultural reproduction in a potentially infinite chain of signification, where each node consists of a replica of the Same as dominant or mass culture, or the imperial cultural space of the Symbolic Order.Footnote 4 What is enacted performatively by each subject as reproducer of dead memes is representations or frozen presentations as expressive articulations that valorize their semantic content in a mode of uncritical giveness. Due to freezing, critical faculties are suspended, suggestibility is enhanced, and memes may propagate endlessly in an uninterrupted fashion. In short, the interruption of critical faculties is a necessary precondition for the uninterrupted blossoming and propagation of memes as “frozen representations” (a pleonasm, since representation presupposes freezing). The uncritical acceptance of freezing on behalf of performers is a prerequisite for the inscription of memes as frozen representations in a cultural short circuit or signifying chain that reproduces the symbolic order of the Same through refracted homologations of the key signs that make up the structural edifice of the multimodal linguistic game of the ice-bucket challenge.

At this point it also merits drawing a sharp distinction between meme and cultural representation. A meme constitutes a performative enactment of a Symbolic Order as dominant cultural paradigm that seeks propagation through prereflective recognition and endorsement by a receiver, while bypassing the critical faculties of conscious elaboration. On the contrary, a cultural representation calls for identification through attention, conscious processing, and the attendant processes of conscious elaboration that involve reflexivity and judgment. A meme constitutes a prereflective scaffolding whereby culture is propagated contagiously through engagement in multimodal language games, whereas a cultural representation spreads through a conscious quest of identity construction by subscription to meaningful resources already available to the members of a community. “What radiates out imitatively (what spreads) should not be confused with a purely cognitive, ideological, or inter-psychological transfer between individuals and organic social formations (groups, masses, etc.). The imitative ray comprises of affecting (and affected) non-cognitive associations, interferences and collisions that spread outward, contaminating feelings and moods before influencing thoughts, beliefs, and actions” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 19).

Most importantly, the mode of communication in the climaxing sequence 4 (table 2) of our video meme is autopathic. The continuity of the actor’s being is suspended in the shocking encounter while being relocated as an act of transcendence to the system of culture that conditions him. The act of suffering as autopathic communication opens up the actor to his “ownmost potentiality-for-Being.”Footnote 5 The receiver (viewing audience) is summoned to participate in the shocking encounter that is mediated by a visual sign. The viewer is summoned to identify with this condition prereflectively through the relationship that is established between the “gaze” and what is gazed at, that is, in the context of an immediate prereflective relationship between the gaze and the visual signs that make up the multimodal meme (cf. Wolff Reference Wolff2012). Since one’s ownmost potentiality-for-Being sustains one’s life project on a prephenomenal level, the memetic mode of cultural reproduction is catapulted to ontological underpinning of existence and, hence, to uncritically endorsed ethical imperative: imitate or perish.

As regards predicating “challenge” of the noun phrase “the ice-bucket,” it is worth pondering whether the subsumption of a clearly ludic activity under the auspices of a challenge is oxymoronic, unless we are not concerned simply with a ludic activity, but with a goal-oriented one, while bearing in mind that motivational structures constitute a necessary presupposition for the engagement in the production and reproduction of cultural memes, as suggested by Wiggins and Bowers (Reference Wiggins and Bowers2014, 8). The cold shower, in this manner, is assigned the status of a goal-oriented activity and not mere play (any extension of “play” to ontological dimensions put aside for the sake of the argument).

But what is the goal or what kind of cause underpins the transition among the states of being that make up this multimodal meme as language game? Again, we are confronted with an invisible structure behind the manifestly ludic game, of a utopian space that functions as the actual milieu wherein the seemingly frivolous performance is located, a space demarcated discursively by an uncritical acceptance of what is given in its mode of giveness (i.e., as a meme qua minimal unit of cultural reproduction) and of giving to others what has been given to oneself. The most conspicuous “cultural mediators” who are given and who pass over the meme bring about the “in-space” in their performative multimodal utterances. In Heidegger’s (Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson[1927] 2001, 169–70) terms, Being-in as such denotes a primordial existential mode of Dasein that does not entail a relationship of inclusion of a spatially determinate territory within another, but an all-encompassing spatiality as condition of determinate space’s spacing. This is the space of culture, and the way this space (as “in-space”) is coarticulated with the Symbolic Order, as above delineated, surfaces in ordinary discourse in the employment of the locative expression “Be-in,” denoting being fashionable or in line with the present-at-hand, inauthentic modes-of-Being-in-the-world or modi vivendi circumscribed by a dominant Symbolic Order. The space of culture as primordial dwelling,Footnote 6 “wherein we are sheltered” (Heidegger Reference Heidegger and Hofstader1975, 217–18), then, is produced performatively in the deployment of a signifying chain of performative utterances that repeat the Same through the replication of a video meme. The primary function of the meme, in these terms, is the reproduction of the Order of the Same as the ontological (in-)space of culture. Moreover, by virtue of the meme’s constituting the primary mode whereby the totality of culture as system appears, the signifying chain also affords to legitimate the meme as primary mode of being in the world as participating in a culture.

The nexus finalis as ontological structure that underpins the ontic manifestations of the ice-bucket challenge rests with the valorization of an impersonal structure of giveness and of memes as mode of propagation of culture. The goal of engaging in this performative act or giving in to what is given is to accept frozenness as state of being and frozen representations as memes as mode of giveness. This interplay of frozenness and giveness on ontological and ontic levels, which function in parallel and in mutual presupposition, is the ultimate goal of the ice bucket challenge. Giving in or surrendering uncritically to the overarching role of memes as mode of propagation of culture is the ultimate cause (and driver) for engaging in this multimodal meme. The donation “addendum” (table 1, sequence 6) that did not fare particularly well among the participants, as aforementioned (even though the total amount that accrued for ALS in the face of this year’s fund-raising initiative by far exceeded last year’s revenues), functions as an ontic pretext that is hierarchically of less importance for this multimodal meme compared to the pure form of giveness as underpinning ontological structure.

As regards the actors in these multimodal memes, these highly visible cultural mediators spanning all sectors of society, we notice the formation of the following equivalences/exchanges between the employment of these cultural signs and the concepts to which they give rise and hence the investment of the multimodal memes with the following meanings. First and foremost, the participating personas are owners of sizable cultural capital (over and above holding, at least for the majority, sizable tangible assets) that is exchanged for a source of legitimacy of memetism as mode of cultural reproduction and propagation of culture. The difference is that these carriers of cultural capital are not paid to perform in this instance, but are summoned to unconditionally give what they are given, to pass on virally (like an Olympic flame) what appears in the performative act of giving, that is, the meme as mode of cultural reproduction. At the same time, in the same homological structure, the exchange of the meaning of a dominant cultural figure for a cultural axiological element as minimal unit of cultural reproduction is also coupled with a monetary act of exchange in the sense of giving (donating) money for a good cause.

At this juncture, a homological co-belonging that emerges through the contiguous embeddedness in the structure of the same performative act is transformed into a causal structure that involves monetary exchange and, thus, a moral dimension. At this very turning point in the performative act of the ice-bucket challenge, the frivolity and the ludic axiology of an innocuous language game that is played by children who have not yet been incorporated into the symbolic structure of the machinery of the Same (of the meme as même) is transferred to another plateau of valorization, that of a symbolic exchange act, where money is given for a “good,” “ethical” cause. In short, the exchange of a frivolous act for a ludic value of fun is sublimated into a symbolic act of exchange of money for a good cause. By virtue of the co-belongingness of these two mutually supporting performances in the same structural gestalt, the frivolous is transformed into a symbolic act. In this act, the performer does not question why an ice bucket and not, for example, a piranha bite, but accepts uncritically the cold shower. What ultimately deploys is a signifying chain that urges each host to become its member as it deploys under the auspices of the giveness of what is, that is, the omnipresent meme as node in the chain. By analogy, the enunciatees or receivers of these memes are summoned to accept them as they come and to inscribe them in their behavioral comportment, rather than reflect on alternative response patterns and courses of action.

This is not a call to members of Habermasian rational actors driven by pragmatic criteria,Footnote 7 but to prerational social actors who absorb (like water is absorbed by the skin) memes, because memes are “good” and “cool.” Moreover, what also becomes apparent is that the frivolous (the playful) in a networked economy is the pathway to the Symbolic. It is through a structure of play that the serious exchange is brought about and propagated. And there is a quite plausible explanation why this is so, given that the structure of play is axiomatic and not dialogic. It is, in Wittgensteinian terms, a matter of “following the rules” of a cultural “language-game,” rather than engaging in a dialogue about the epistemic status of the language game’s rules. Additionally, the structure of play is of greater ontological gravitas (more primordial, in Heideggerian terms) compared to a cognitively elaborated message where the employment of a sign of suffering might be mitigated by the homeostatic Cerberus of the ego. In these terms, masochism as mood-state is tantamount to an unconditional openness to what is given in its mode of giveness. In this instance, “subjectivity is open to the magnetizing, mesmerizing, and contaminating affects of others” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 29).

The postclimax affective reactions of the actors (table 1, sequence 4), by extension, constitute flows of signs of intensity, whose object is lost in the permutations of nanoparticles of water, and hence only schematically constituting an object, but rather aberrant object or abject. The postencounter reaction retains the moment of the encounter with an original force, whose memory lives in its inscription in a cultural sign whose meaning is “shock” (ice falling on the head). As noted by Virilio (Reference Virilio2005), shock is the model of sensation, as it happens, and is closely related to a contraction of the domestic domain, the domain of safety and control over the body. “Unlike a social body composed of collective representations, this is a subrepresentational flow of events” (Sampson Reference Sampson2012, 6).

Conclusion and Areas for Further Research

The ice-bucket challenge constitutes a seminal milestone in the evolution of viral communications as the dominant paradigm in a networked economy by virtue of the stature of its participants in a global cultural nexus, as well by the extent and rate whereby this video meme spread in a condensed time period. This article sought to map out the antecedents and implications of this cultural phenomenon by contributing to the scholarly literature on video memes with a systematic analysis of its formal multimodal expressive structure in an attempt to anchor as succinctly as possible the subsequent analysis of its function(s) on ontic and ontological levels. Going forward, it would be of particular scholarly interest in the field of new media studies, but also for marketing research, to conduct a comparative analysis of different tactical implementations of the same fund-raising activity throughout time on the basis of the blueprint offered in this article with view to determining correlational patterns between form and function that are conducive to superior bottom-line results.