Introduction

A large and vibrant literature investigates whether, and under what circumstances, voters will punish corrupt politicians (e.g. Ferraz & Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Fernández‐Vázquez et al., Reference Fernández‐Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016; Winters & Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Winters and Weitz‐Shapiro2013). Often using survey experimental vignettes, research in this tradition has found mixed evidence overall (De Vries & Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2017; Incerti, Reference Incerti2020) but also highlighted important conditions including partisanship (Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013), economic performance (Klašnja & Tucker, Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013), gender (Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2018) and type of corruption (Mares & Visconti, Reference Mares and Visconti2020; Weschle, Reference Weschle2016).

Research on corruption itself, meanwhile, is undergoing a ‘transnational turn’ (e.g., Cooley & Sharman, Reference Cooley and Sharman2017; Findley et al., Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Heywood, Reference Heywood2018; Transparency International UK, 2019) with increasing emphasis on the roles of transnational actors and linkages in enabling and driving corruption. This work seeks to reorient the study of corruption away from a ‘methodologically nationalist’ focus (Cooley & Sharman, Reference Cooley and Sharman2017). Recent events such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine have also turned increasing attention to the roles of major financial hubs like the United Kingdom in enabling transnational corruption (e.g., The Economist, 2022).

This paper brings these two streams of research together. To date, studies of voter behaviour in response to corruption have neglected the basic empirical fact that much real‐world corruption is transnational in nature, with the supply of bribes and other illegal payments often arising from outside the country in question. It is thus a pressing question whether voters might differentially punish politicians associated with transnational as opposed to domestic corruption. In the extreme, studies that neglect the transnational dimension might fail to adequately generalise to much of the real‐world behaviour of interest. Alternately, voters may pay little attention to transnational dimensions of corruption, even as policymakers increasingly do so.

Given the prevalence of transnational corruption and prominent examples of public outrage when it is publicised, it is also of substantial theoretical importance to better understand the precise mechanisms through which voters might differentially punish transnational corruption. We elucidate four such mechanisms – information salience, country‐based discrimination, economic nationalism and expected representation – and test each of them.

We study these questions using a pre‐registered survey experiment in the United Kingdom in 2020, with a vignette describing a hypothetical incumbent accused of accepting gifts in exchange for influencing decisions but varying the stated headquarters of the bribe‐offering firm between domestic (‘London based') or foreign (‘Moscow based’ or ‘Berlin based'). We find evidence suggesting that voters indeed differentially punish transnational corruption, but only involving the Moscow‐based firm.

This is most consistent with a mechanism of country‐based discrimination and suggests that transnational corruption is punished primarily insofar as it links politicians with countries that are negatively perceived by the public generally, paralleling similar findings on attitudes towards foreign direct investment and trade (Carnegie & Gaikwad, Reference Carnegie and Gaikwad2022; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Kerner and Sumner2021; Jensen & Lindstädt, Reference Jensen and Lindstädt2013). We do not find evidence consistent with any other hypothesised mechanism.

These results highlight that, under certain circumstances, voters do indeed punish politicians for transnational corruption. Past experimental research on voter responses to corruption has neglected the frequency with which real‐world corruption allegations involve transnational partners, and thus potentially understates the potential for effective electoral accountability.

Integrating research on domestic and transnational corruption

Theories of electoral accountability presume that voters will punish politicians for poor performance and wrongdoing in office and reward them for positive performance (Przeworski et al., Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). A large literature has investigated this proposition empirically, often with a focus on how voters respond to information about corruption, and the conditions under which they may or may not do so (for a review, see De Vries & Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2017). Such studies have used a variety of methods, including natural experiments (e.g., Berliner & Wehner, Reference Berliner and Wehner2022; Ferraz & Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Fernández‐Vázquez et al., Reference Fernández‐Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016), field experiments (e.g. Boas et al., Reference Boas, Hidalgo and Melo2019; Chong et al., Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015), and survey or conjoint experiments (e.g. Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013; Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2018; Winters & Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Winters and Weitz‐Shapiro2013), and yielded important findings as to conditions under which voters are more or less likely to punish corruption. However, the literature as a whole offers largely pessimistic conclusions, often finding no average effects of corruption information (e.g. Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Grossman, Humphreys, Hyde, McIntosh, Nellis, Adida, Arias, Bicalho and Boas2019), and voters willing to overlook corruption in light of partisanship or economic growth.

Across this literature, however, researchers have only explicitly examined voter responses to domestic corruption. The corruption information that is provided to participants in these studies involves either a domestic politician alone or a domestic politician acting for the benefit of some other entity that is either explicitly or implicitly in‐country. In some cases, particularly natural‐experimental studies of responses to real‐world corruption scandals (e.g. Fernández‐Vázquez et al., Reference Fernández‐Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016), the corruption in question may in fact have involved some transnational element, but this has (to our knowledge) never been included explicitly as a research design element for focused study.

This neglect of transnational corruption in the electoral accountability literature stands in stark contrast to developments over the last decade in research on – and policymaker understandings of – corruption itself. A growing ‘transnational turn’ in corruption studies has led to a substantially greater focus on corruption as a transnational problem rather than a purely country‐by‐country problem. Cooley and Sharman (Reference Cooley and Sharman2017, p. 746) argue ‘that the methodological nationalism that frames much research and policy on corruption skews our understanding of its increasingly transnational nature’. More recent research focuses instead on the transnational actors that often instigate corruption and the transnational networks that enable it (Findley et al., Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Dávid‐Barrett & Tomić, Reference Dávid‐Barrett and Tomić2022; Heywood, Reference Heywood2018; Soares De Oliveira, Reference Soares De Oliveira2022).

Many recent corruption scandals highlight these transnational dimensions of corruption. Revelations in major leaks of documents pertaining to offshore finance, such as the Panama Papers, have had widespread political consequences in both global ‘north’ and ‘south’ (Graves & Shabbir, Reference Graves and Shabbir2019). The revelations of transnational bribery by the Brazil‐based construction company Odebrecht have had major political implications across multiple Latin American countries. Research on corruption itself also often focuses on foreign firms as the key agents offering bribes or other forms of irregular benefit to domestic politicians (e.g. Jensen & Malesky, Reference Jensen and Malesky2018; Malesky et al., Reference Malesky, Gueorguiev and Jensen2015; Wu, Reference Wu2005). And yet, no research has sought to differentiate whether the domestic or transnational nature of corruption allegations matters for electoral responses. For several reasons, which we develop below, voters may respond more harshly to transnational corruption allegations than to purely domestic ones.Footnote 1

Although we focus in this study on electoral responses to corruption in the United Kingdom, that jurisdiction has been no stranger to allegations of corruption by politicians. In some cases, MPs and local councillors have been directly accused of accepting bribes, often allegedly in exchange for assistance in obtaining contracts or planning permissions.Footnote 2 Notably, our survey was fielded in 2020, before both a 2021 period of heightened public attention to MPs potentially involved in favouritism in contracting during the Covid‐19 pandemic; and before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine increased public attention to allegations of foreign involvement in politics.

Integrating these two literatures – on electoral responses to corruption, and transnational dimensions of corruption – generates our primary hypothesis:

H1: Respondents are more likely to electorally oppose politicians being investigated for transnational corruption than for domestic corruption.

However, we also develop a series of secondary hypotheses pertaining to the specific mechanisms that might generate such a difference.

Differentiating mechanisms

We suggest several potential mechanisms through which voters might differentially punish transnational corruption, drawing on a variety of cognitive, affective, ideological and rational theoretical approaches used in past research: Information salience, country‐based discrimination, economic nationalism and expected representation.

First, information about corruption involving foreign firms might be more cognitively available to voters and thus operate through an information salience mechanism. Existing research on information and electoral accountability has also investigated the potential role of information salience (e.g. Adida et al., Reference Adida, Gottlieb, Kramon and McClendon2020; Berliner & Wehner, Reference Berliner and Wehner2022). In real‐world voting behaviour, foreign corruption might be more salient due to macro‐level features as well, such as media agenda‐setting, but these cannot be tested at an individual level. For individuals, involvement of foreign actors might make allegations of corruption more memorable and thus more cognitively available in processes of vote choice. Such a mechanism would be purely cognitive, rather than rational or ideological.

H2: Information salience mechanism: Respondents differentially punish transnational corruption because it is more cognitively available.

We test this hypothesis by evaluating whether respondents are more likely to correctly recall the type of allegation when involving transnational (as opposed to domestic) corruption. If this is the case, it will suggest that the transnational allegation was more memorable. This approach allows us to empirically assess information salience without directly manipulating it.Footnote 3

Second, corruption involving foreign firms might be differentially punished due to country‐based discrimination, suggesting that the effect of information depends on the country in question. Past research has found biases against specific countries – whether for ethnocentric or geopolitical reasons – to be relevant for attitudes towards foreign trade or investment (Carnegie & Gaikwad, Reference Carnegie and Gaikwad2022; Jensen & Lindstädt, Reference Jensen and Lindstädt2013; Zeng & Li, Reference Zeng and Li2019). Jensen and Lindstädt (Reference Jensen and Lindstädt2013, p. 3) find more positive attitudes towards foreign investment among respondents with ‘a favorable opinion of the foreign investor's country of origin’. Corruption involving foreign firms might also be evaluated in country‐specific ways if respondents consider some countries more corrupt than others, and thus some allegations are more likely to be true. Such a mechanism could thus either be driven by negative affect or be rationally information based.

H3: Country‐based discrimination mechanism: Respondents differentially punish transnational corruption only for countries viewed negatively.

We test this hypothesis by evaluating whether electoral opposition is greater for transnational corruption allegations involving such countries that the public tends to view more negatively.

Third, corruption involving foreign firms might be differentially punished through an economic nationalism mechanism. That is, voters might oppose foreign economic involvement more generally and thus disapprove of corrupt actions for transnational partners specifically because they potentially enable even greater such involvement. Research on public attitudes to international trade and foreign investment has often found such economic nationalism at work (e.g. Feng et al., Reference Feng, Kerner and Sumner2021; Mansfield & Mutz, Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Margalit, Reference Margalit2012). Unlike the other mechanisms considered, this one would be largely ideological in nature.

H4: Economic nationalism mechanism: Respondents differentially punish transnational corruption due to nationalist attitudes opposing foreign involvement in the economy in general.

We test this hypothesis by evaluating whether electoral opposition to transnational corruption allegations is greater among economically nationalist respondents.

Finally, corruption involving foreign firms might be differentially punished through an expected representation mechanism. Voters might expect that politicians linked to transnational corruption allegations will be more prone to represent interests further from those of their own constituents. Some studies of domestic corruption allegations have suggested that voters might forgive corruption in settings where it helps promote local economic growth (Fernández‐Vázquez et al., Reference Fernández‐Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016; Winters & Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Winters and Weitz‐Shapiro2013). While in such settings, corruption could arguably be interpreted as an indication that politicians are indeed representing voters’ economic interests, voters may see corruption involving foreign firms as a sign that politicians are representing interests outside their constituency instead. Such a mechanism would be largely rational in nature, using information on foreign corruption to update assessments of incumbent type.

H5: Expected representation mechanism: Respondents differentially punish transnational corruption because they think involved politicians will be poorer representatives of their interests.

We test this hypothesis by evaluating whether respondents expect poorer representation from politicians alleged to have been involved in transnational (as opposed to domestic) corruption.

Methods and results

We carried out a survey experiment in 2020, embedded in YouGov's UK Political Omnibus survey. We approached our main research question by providing respondents with a vignette of a successful politician running for re‐election but being investigated for corruption and randomising the domestic or transnational nature of the corruption allegation. We used a series of additional features of the survey in order to test different potential mechanisms.

The survey sample included 1621 adults eligible to vote in the United Kingdom in September 2020. The design for this study and all hypotheses were pre‐registered.Footnote 4 Each participant was shown a vignette presenting a hypothetical incumbent politician standing for re‐election but accused of involvement in corruption. We randomised the stated location of the bribing firm, for example, a London‐based firm if referring to domestic corruption and a foreign‐based firm for transnational corruption. This allowed us to estimate the average punishment differential for a politician associated with a transnational corruption allegation versus a domestic one. In order to focus most effectively on this difference, and in order to make the scenario more informative, all respondents were given the same information suggesting good performance‐in‐office by the politician.

In order to test a country‐based discrimination mechanism, we include two different foreign headquarters for the hypothetical bribing firm: either ‘Berlin’ or ‘Moscow’. These choices reflect the starkly differing favourability towards these countries, as reflected in YouGov's 2020 ‘The most popular countries in the United Kingdom’ results, showing Germany as the 22nd most popular and Russia as the 118th most popular.Footnote 5 The three treatment cities were randomised with an equal probability of assignment among all participants. We thus offered respondents the vignette below:

‘Imagine you live in a similar neighbourhood to yours but in a different part of the country, and that a General Election will be held soon. The constituency's MP is running for re‐election, after what most constituents consider a successful time in parliament. New GP practices have opened, and improvements have been made to local primary schools. However, the MP is also under investigation following accusations of accepting gifts from a [London/Berlin/Moscow]‐based company in exchange for help obtaining government contracts. How likely would you be to vote for the MP in the upcoming election?'

The latter question provided the main outcome variable, with five possible responses ranging from ‘Very likely’ to ‘Extremely unlikely’. We coded these from 1 to 5, with higher values expressing greater electoral opposition (lower support) to the politician. In our first test, of Hypothesis 1, we simply regress this on an indicator for foreign firm – combining both ‘Berlin’ and ‘Moscow’ conditions.

However, we also asked three additional questions to test additional potential mechanisms.

In order to test Hypothesis 2, we include an additional question later in the survey, asking: ‘Earlier in this survey you read about a hypothetical MP who was accused of accepting gifts from a company. What was the MP accused of providing in exchange for these gifts?’, with response options (presented in random order) ‘Help obtaining government contracts’, ‘Help obtaining planning permissions’, ‘Help obtaining tax exemptions’, ‘Help obtaining information on upcoming regulatory changes’. We code whether or not respondents correctly recalled that the accusation pertained to government contracts, in order to produce an indicator of information salience. We use this as an alternative outcome variable and regress it on the foreign firm treatment.

In order to test Hypothesis 3, we interact foreign firm with an indicator for the Moscow‐based firm. This tests whether electoral opposition is significantly different between the two foreign headquarters. In an alternative test in the online Online Appendix, we instead test whether responses are significantly different between Moscow and London.

In order to test Hypothesis 4, we measure economic nationalism with an additional question appearing several questions before the vignette: ‘In recent years, many foreign companies have invested in the United Kingdom. Do you think these investments are good for the United Kingdom?’ We interact the main foreign firm treatment with the resulting economic nationalism indicator, equal to 1 for respondents answering ‘No’ and equal to 0 for respondents answering either ‘Yes’ or ‘Don't know’.

Finally, in order to test Hypothesis 5, we included another additional question which appeared after the vignette. We measured expected representation by asking: ‘How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement: ‘The MP will be dedicated to working for the interests of their constituents.’’. Responses ranged from ‘Very likely’ to ‘Extremely unlikely’ on a five‐point scale. We used this as an alternative outcome variable, regressing it on the foreign firm treatment.

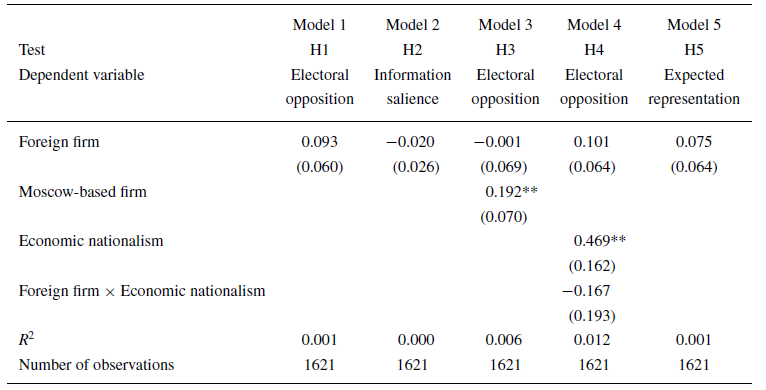

Table 1 shows the results for these five tests using ordinary least squares regression.Footnote 6 In the Online Appendix, we present balance tables indicating some imbalance among treatment groups on two variables: income and 2019 party vote. As pre‐registered, we thus present robustness checks in the Online Appendix that control for these variables (but all our findings remain substantively highly similar).

Table 1. Results of models testing hypotheses 1–5. Intercept not shown. The ‘electoral opposition’ dependent variable is oriented such that higher values reflect greater electoral punishment (lower support). (See Online Appendix for robustness checks controlling for unbalanced covariates.)

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$;

$^{**}p<0.01$;

![]() $^{*}p<0.05$.

$^{*}p<0.05$.

Model 1 tests our first hypothesis but finds no significant difference in electoral opposition to the hypothetical candidate whether the accusation is of corruption involving a foreign or domestic firm. The ‘foreign firm’ group here combines both Berlin and Moscow headquarters treatments. Model 2 tests our second hypothesis, that information is more salient when corruption accusations involve foreign firms. However, we find no significant difference in our information salience–dependent variable. Model 3 tests our third hypothesis that respondents punish corruption accusations more when they involve a foreign firm based in a negatively viewed country. Here, we see a significant difference, with greater punishment involving a Moscow‐based firm than a Berlin‐based one. In the Online Appendix, we also show an alternative version of this test, comparing the Moscow‐based firm against the London‐based firm instead. In Model 4, we test our fourth hypothesis, that economically nationalist respondents will be more likely to punish corruption accusations. However, we find no significant interaction term. Finally, Model 5 tests our fifth hypothesis, that respondents view politicians accused of corruption involving foreign firms as less representative of their constituents. However, we see no significant coefficient on the foreign firm variable.

Thus the only mechanism that we see evidence in favour of is one of country‐based discrimination. Respondents’ electoral opposition to a politician accused of corruption is 0.192 higher (on a five‐point scale) when that accusation involves a Moscow‐based firm than a Berlin‐based firm. As shown in the Online Appendix when we compare the Moscow‐based firm and London‐based firm directly, this difference is 0.19. In covariate‐adjusted models in the Online Appendix, results are highly similar in substance and significance.

The Online Appendix also presents purely exploratory results that were not pre‐registered, modifying Models 2, 4 and 5 by adding the same differentiation between Berlin‐based and Moscow‐based foreign firm as appears in Model 3. We find no significant differences, except for the information salience outcome, for which we find that respondents recall the detail of the vignette worse under the Moscow‐based treatment condition. Although purely exploratory, the negative direction of this result appears to further confirm the absence of an information salience mechanism. It might also tentatively suggest that the country‐based discrimination mechanism is more likely to operate for purely affect‐based reasons rather than due to differential knowledge of corruption relating to Russia.

Conclusion

Research on voter responses to corruption has to date neglected the empirical prevalence and theoretical importance of transnational corruption. We carried out a survey experiment in the United Kingdom in 2020 to understand whether voters differentially punish politicians associated with transnational and domestic corruption allegations. Although we do not find evidence that transnational corruption is punished more in all circumstances, we do find that voters punish politicians more when the hypothetical allegation involves a Moscow‐based firm.

Although we develop four potential mechanisms through which transnational corruption might be differentially punished, we only find support for one: A country‐based discrimination mechanism by which corruption involving foreign firms links politicians to countries which are negatively perceived by the public. Respondents differentially punished corruption involving a ‘Moscow‐based’ firm but not a ‘Berlin‐based’ firm. Thus while respondents differentially punished one of the two instances of transnational corruption, they did not differentially punish both, indicating some form of country‐based discrimination. Although this difference could be for reasons of negative news coverage, ethnocentrism, geopolitics or perceptions of corruption, these are difficult to disentangle empirically given that they may align with British public perceptions of Russia (even in 2020 when the survey was carried out). Future research should investigate this difference further by assessing transnational corruption allegations involving a broader array of countries with different public reputations. We do not find any evidence in support of three other mechanisms: information salience, economic nationalism or expected representation.

This study brings together literature on transnational corruption and electoral accountability, offering new insights on how and why voters respond to corruption allegations. The finding that transnational corruption is, under some circumstances, subject to greater electoral punishment suggests that existing empirical research might understate the relevance of such electoral accountability by neglecting the corruption allegations’ frequent transnational dimension. Our findings also highlight the role of negative public perceptions of certain countries but not three other potential mechanisms, evidence that can inform anti‐corruption advocacy work oriented at mobilising public opinion and changing societal norms that enable corruption to persist (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Florian Foos, Nikhil Kalyanpur and Sara Hobolt for their helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by the LSE Department of Government Departmental Research Fund.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Information

This research was supported by the LSE Department of Government Departmental Research Fund.

Data availability statement

Replication data and code are available on the journal's web page associated with this article.

Ethics statement

The study was determined to be low risk by the LSE Research Ethics Committee and subsequently approved by the LSE Government Department.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table 2: Balance tests across three treatment categories.

Table 3: Results of models testing hypotheses 1‐5, including controls for covariates that were unbalanced across treatment categories.

Table 4: Robustness check comparing ‘Berlin’ and ‘Moscow’ indicators directly against ‘London’ reference category, rather than including interaction term between ‘Foreign firm’ and ‘Moscowbased firm’.

Table 5: Robustness check of the main models, M2 Information salience, M4 Economic Nationalism and M5 Expected Representation, all interacted with the Moscow‐headquartered firm.

Table 6: Ordered logit robustness checks of the main models with Likert‐scale outcome variables (Models 1, 3, 4, and 5).

Data S1