Inequality in Prehistoric Europe?

Since the seventeenth century, the origin of social inequality has been one of the central questions—perhaps the central question—of the social sciences, preoccupying theorists such as Hobbes, Rousseau, and Marx in philosophy, politics, sociology, and anthropology. Archaeologists have also contributed to the discussion, particularly since the development of New Archaeology’s social evolution agenda, which still provides many basic operational concepts used in the archaeology of politics.

Prehistoric Europe provides an indispensable case study for this discussion. It is one of the best-studied archaeological sequences in the world, with 6,000–8,000 years of sedentary pre-state life and thousands of excavated sites. However, it has repeatedly defied development of any clear story of how inequality developed. Attempts to document a steady “rise of inequality” have never been successful. Neolithic societies with florid ritual systems lack prominent individuals and centralized political power; Bronze Age societies with elaborate burials and extensive trade lack monumental constructions and economic accumulation. The most convincing narrative that archaeologists have been able to construct is one in which inequality changed its nature partway through prehistory from group-oriented ritual knowledge to individualizing prestige competition (Renfrew et al. Reference Renfrew, Todd and Tringham1974). This fragmented picture underlies two apparently unbridgeable chasms in current studies. One is a discrepancy between a Neolithic era in which politics is almost invisible (Fowler et al. Reference Fowler, Harding and Hofmann2015) and a Bronze Age sometimes portrayed as dominated by its political economy (Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). The other is a Bronze and Iron Age literature split between separate, parallel realities—one focused on strategic, ambitious elite male leaders (Earle Reference Earle2002; Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005) and the other encompassing gender, ritual, cosmology, and other themes (Fokkens and Harding Reference Fokkens and Harding2013; see Collis and Karl [Reference Collis, Karl, Haselgrove, Rebay-Salisbury and Wells2023] and Moore [Reference Moore, Haselgrove, Rebay-Salisbury and Wells2023] for balanced assessments of the Iron Age).

The failure of European prehistory to contribute to understanding early inequality derives from both its conceptual foundations and how data are interpreted. I first discuss how prehistoric inequality in Europe has been conceptualized and then provide a broad assessment of how much inequality there actually was, using the Central Mediterranean sequence as a capsule illustration. I then outline an alternative “people’s history” of prehistoric society involving complex, heterarchical social orders and people’s capacity for self-governance.

An Unhealthy Fascination with Inequality …

In social evolution approaches, after agriculture was achieved and before urban states emerged, “the origins of inequality” form the central storyline (Service Reference Service1962, Reference Service1975). But today and in the past, inequality is theoretically complex. In the most general sense, it refers to a situation in which people have differential access to social value, resources, and social position. Archaeologists studying inequality often reduce it to a manageable problem through a series of assumptions:

• Inequality is a matter of individual agents exerting power over others to accomplish their will (rather than being class-based as in most Marxist approaches); power is personalized, instrumental, and a single universally defined quantity, rather than systemic, diffuse, or culturally defined.

• Inequality is explicitly “political” as opposed to “domestic,” gendered, aged, et cetera.

• “Political” agents are explicitly or implicitly adult males: they are either all adult males or a subset of “aggrandizers” who inherently wish to dominate others (Clark and Blake Reference Clark, Blake, Brumfiel and Fox1994; Hayden Reference Hayden, Price and Feinman1995). Adult women and people of other ages are invisible or seen principally as a compliant source of labor.

• Inequality consists of a permanent, structural hierarchy; it involves generalized powers of organizational control or management.

• Power tends to be unquestioned, and inequality provides an unambiguous social order. People accept power because they are compelled through military, economic, or political control or are ideologically deluded (Mann Reference Mann1986).

• Inequality can be represented as a single quantity that is associated with “complexity” and that generally increases throughout history.

Defining the problem in this way reframes inequality: the problem to solve thus becomes how ambitious individuals create strategies to dominate others (Earle Reference Earle1997; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery2012; Hayden Reference Hayden1990; Price and Feinman Reference Price and Feinman1995). The individuals and their motivation and power in general are seen as existing prior to and outside culture; the constitution of social class in a Marxist sense or power in a Foucauldian sense is thus lost. Even recent “collective action” approaches (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016) follow this paradigm in assuming that politics emerges from the actions of preconstituted, rational social actors; whether people act collectively is not a matter of culture but of choosing an instrumental strategy that will work in a particular setting.

Part of the reason that this approach has dominated social archaeology is its narrative mandate. Narratives of hierarchy familiarize the past in our terms (for instance, equating inequality with explicit organizational structures), and rational, strategic male actors replicate our ideas about successful life strategies and power domination. Looking for a clear, explicit institutional politics and regarding a proclaimed social order as an uncontested fact may reflect modernist attitudes. Moreover, such narratives rest on implicit assumptions about equality:

• Inequality is active and is done by individuals; equality, a “natural” prior state, just happens passively.

• Inequality is competitive and involves doing thing to other people; equality is cooperative and involves doing things with others.

• Inequality is something men do; equality is something everybody does.

Because equality happens as a default ur-state while people actively develop inequality, “origins of inequality” narratives implicitly valorize inequality as progress, whether that is positive or negative. Moreover, the expected pattern is a continual, concurrent increase in population, technology, “complexity,” and inequality. Thus, finding inequality not only confirms our expectations but also enables exciting things; for instance, the fancy finds highlighted in publications and exhibitions. In contrast, not finding inequality implies failure, stagnation, and lack of a result or storyline.

It is no surprise therefore that when archaeologists spot something they can identify as inequality, they tend to prioritize it as the most important thing to state about the social order and as an absolute, defining fact. This is the “defining impurity” model of inequality, in which any trace of inequality suffices to disqualify a society from being “egalitarian,” much as any trace of meat disqualifies a dish from being vegetarian. The bias in this model would be evident if we were to invert it and consider that any trace of equality disqualifies a society from being “hierarchical”! Attributing undue importance to any inequality detected is a sign of our unhealthy fascination with inequality.

Alternative Models for Social Action

Fortunately, the theoretical landscape is well stocked with critiques and alternative models. Feminists have cautioned against centering historical narratives on adult males and treating perceived male modes of behavior as universal human standards (Gero Reference Gero, Dobres and Robb2000). Heterarchy theorists (Ehrenreich et al. Reference Ehrenreich, Crumley and Levy1995) point out the importance of horizontal structures, multiple organizational principles, and cooperative effort in all societies. Other critiques claim that inequality should be measured not by universal market-based criteria but by people’s capabilities (Müller et al. Reference Müller, Arponen, Hofmann and Ohlrau2015). Social anthropologists have shown that different, contradictory forms of leadership coexist in all societies, particularly nonstate ones in which the political structure may be deeply ambiguous (Roscoe Reference Roscoe2000). Both Geertz (Reference Geertz1980) and Foucault (Reference Foucault1977) have shown how power is culturally constituted, diffuse, and not restricted to explicitly “political” domains.

Within alternative traditions, a robust Marxist tradition characterizes some non-Anglophone traditions, particularly in Iberian prehistory (Chapman Reference Chapman2008; Cruz Berrocal et al. Reference Berrocal, María and Gilman2013; Gilman et al. Reference Gilman, McC. Adams, Maria Bietti Sestieri, Cazzella, Claessen, Cowgill and Crumley1981; Lull et al. Reference Lull, Micó, Herrada and Risch2010; see also the Italian studies reviewed later). In another direction, structural Marxists draw attention to the interplay of gender, kinship, knowledge, and seniority in inequality, especially in nonstate societies (Bloch Reference Bloch1989; Meillassoux Reference Meillassoux1981). Classically, Engels (Reference Engels1972) also argued that prehistoric tribes were based on the subjugation of women by men, although feminist archaeologists have pointed out the presence of powerful women in all societies. Marxists also show how inequality may be masked, submerged, or ambiguous; it is also never uncontested and may be subjected to pushback, dispute, or the expectation of real benefits for the group as a whole (Levy Reference Levy1992; McGuire and Saitta Reference McGuire and Saitta1996). Scott (Reference Scott1990) shows how even in strongly exploitive situations people find ways to evade, resist, and contest power. In postcolonial thought, colonial worlds do not simply reflect a single determining order emanating from metropolitan centers that is passively accepted; instead, they comprise differently positioned individuals pursuing their own agendas (Wolf Reference Wolf1982). Such views underlie a “people’s history” approach, in which history is a story of conflict as ordinary people defend their rights against encroaching power plays (Zinn Reference Zinn1980).

The most recent voice is anarchy theory, which argues that all people are active participants in creating their own social order (Angelbeck and Grier Reference Angelbeck and Grier2012; Flexner and Gonzalez-Tennant Reference Flexner and Gonzalez-Tennant2018; Furholt et al. Reference Furholt, Grier, Spriggs and Earle2020; Graeber Reference Graeber2004; Graeber and Wengrow Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021; Joyce Reference Joyce2023; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Furholt and Austvoll2022; Politopoulos et al. Reference Politopoulos, Frieman, Flexner and Borck2024; Sanger Reference Sanger2022). They may or may not try to dominate others, but they do manage their own lives and defend their rights and freedom from constraint. Doing so may involve many tactics, both conscious and structural. To take a few examples, mobility is important, as when people withdraw their support and move away from restrictive situations. Dividing social roles and powers heterarchically—for instance, having separate leaders for war, peace, ritual, and kinship—limits how much any one role or leader can dominate others. Expecting leaders to redistribute or dispose of wealth (as in feasts or sacrifices) ensures that leaders remain poor, dependent on their supporters, or both. Anarchy theory provides not only examples of how people inhibit the growth of inequality but also positive models of how collectivities successfully manage projects, ranging from economic survival and risk management to building infrastructure and monuments (Graeber Reference Graeber2004).

All these add up to a strong bottom-up approach to how inequality developed (see also Furholt et al. Reference Furholt, Grier, Spriggs and Earle2020; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Furholt and Austvoll2022; Thurston and Fernández-Götz Reference Thurston, Fernández-Götz, Timothy and Fernández-Götz2021):

• People’s motivations, actions, and forms of power should be understood as culturally constituted within a particular context and set of social norms. Ancient people do not try, anachronistically, to create novel social orders that we might imagine; they modify the world of what is thinkable within their social context.

• All societies include multiple forms of social relationships, often expressed through different fields of action. As an evidential corollary, any one field of action and any one form of archaeological data may reflect only some of the relationships that are important within a society. We should be cautious about privileging any single context (as burial traditionally has been privileged) as a key to unlocking ancient social orders.

• All human societies contain social inequalities; the key question is not their mere presence but how they are organized with other forms of relationship into an overall social order. Moreover, inequality or the lack of it may be deeply ambiguous rather than clear-cut. Such “ambiguous” situations are not anomalous or transitional; they may persist stably for centuries or millennia—indeed, they may be more stable than situations in which inequality is patently unambiguous.

• Ideology typifies this ambiguity. It can be a powerful tool for social control, as in the classic Marxist sense. However, both leaders and followers share ideologies, and ideology gives form to their ambitions in particular directions and subject to certain constraints; for instance, about what makes power legitimate in any given context. This may limit any attempt to maximize advantage (see the later discussion of Bronze Age display for an example).

• Social tensions within groups will be a major driver of long-term social change. Many archaeologically evident social actions may involve not attempts to create power or inequality but instead tactics for preventing, channeling, or resisting them.

• Equality and self-determination are always potentially under threat; maintaining them is a continuous social achievement.

With these precepts in mind, let us look at the actual evidence for inequality in European prehistory.

Inequality in Prehistoric Europe: The Greatest Hits?

Reviews of inequality in prehistoric Europe often involve recital of the same list of sites.Footnote 1 There have been occasional claims for Upper Paleolithic leaders, based mostly on the Arene Candide (Pettitt et al. Reference Pettitt, Richards, Maggi and Formicola2003) and Sunghir (Trinkaus et al. Reference Trinkaus, Buzhilova, Mednikova and Dobrovolskaya2014) burials. After these burials, there is a long gap in time; even the few Neolithic burials with individualized burial treatment (notably the Linearbandkeramik) rarely supported interpretations of social inequality. Large Neolithic ritual systems—notably Stonehenge (Pearson Reference Pearson2012) and Malta (Cazzella and Recchia Reference Cazzella and Recchia2015)—are sometimes mentioned as having hierarchical leaders commanding special ritual knowledge. For the Copper Age, the outstanding examples are the Varna and Durankulak cemeteries in Bulgaria (Gyucha and Parkinson Reference Gyucha and Parkinson2023), with burials containing elaborate stone, copper, and gold objects, and Iberian sites such as Los Millares, Valencina de la Concepción, and others with centralized fortified settlements, rich burials, intensified agricultural systems, centralized fortified settlements, megaliths, and possible ritual leadership (Chapman Reference Chapman2008).

For much of the third millennium BC, single depositions with individual grave goods were the rule (whether in single graves or collective tombs), and the range of variation in burial mode and grave assemblages was limited; this evidence signals changing modes of social action, rather than strongly defined new hierarchies. Except for Aegean Bronze Age “palace” societies, which need to be understood in the ambit of interaction with Egyptian and Levantine cities, the story quickens with enclaves across Europe of elaborate Early Bronze Age burials in Leubingen (Germany), Argaric sites (Spain), the Wessex Culture (England), and others. These are often covered by mounds and include central burials accompanied by rich personal objects, particularly metalwork. Such examples underwrite a story of chiefs (Earle Reference Earle2002; Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Carman and Harding1999) or “kings” (Gyucha and Parkinson Reference Gyucha and Parkinson2023) who led warfare, collected agricultural surplus, developed far-reaching networks, redistributed goods to their followers, and used them to proclaim their status.

Such Early–Middle Bronze Age inequality appears somewhat fragile or evanescent, in almost all cases giving way to less ostentatious later Bronze Age and Iron Age societies (Harding Reference Harding2000). Around the Mediterranean coastline, later Bronze Age fortified sites may show where elites collected surplus and traded with Aegean networks (Cazzella and Recchia Reference Cazzella and Recchia2021). Later, in the Iron Age, early Mediterranean urban societies may have been governed by land-owning elites; cemeteries often include rich burials, including ostentatious “princely burials” of the eighth to seventh centuries BC (Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2016). North of the Alps, early proto-urban societies include sixth to fourth century BC “fürstensitze” sites such as the Heuneburg (Germany) and later “oppidum” sites such as Bibracte (France). Throughout Europe, such sites and Iron Age hillforts generally have been interpreted as loci of hierarchical elites (Collis and Karl Reference Collis, Karl, Haselgrove, Rebay-Salisbury and Wells2023).

Assessing Prehistoric Inequality in Europe

This “greatest hits” list presents us with an image of accelerating inequality, which satisfies the social evolution narrative mandate discussed earlier. But this view evokes three related critiques. First, some components are questionable on their own terms. For example, the deceased in Upper Paleolithic burials are more usually interpreted as ritual specialists or people dying in particular circumstances than as “chiefs” (Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011). Similarly, a reexamination of Iberian Copper and Bronze Age sequences shows that interpretations of hierarchy have often been overstated and that resistance to hierarchy was common (Cruz Berrocal et al. Reference Berrocal, María and Gilman2013).

Second, there are theoretical grounds for questioning this image of growing inequality. It takes a sectional view of society, particularly that of “politically active” adult males—perhaps 10%–20% of prehistoric society—and treats it as universal, as representing the central facts about society. It also focuses narrowly on one form of interaction—hierarchy—rather than assessing social interaction more globally. Similarly, it relies above all on burial evidence, particularly for periods before the Iron Age. It is generally assumed that a person’s persona in burial not only provides a truthful report on their social role in life but also represents the most central social fact about them—how they would actually have interacted with others in everyday contexts—rather than how they were presented in a particular ritualized, formalistic context. For example, the elaborate Early Bronze Age burials noted earlier show individuals whose social persona (as represented in death) displays exotic valuable goods, implying they controlled economic resources; yet, this picture is virtually never mirrored by the evidence from life of similar levels of distinction in housing, storage capacities, management of collective projects, occupational status, conditions of life, and so on. Thus, nonburial evidence is discounted, and burial evidence is both taken at face value and relied on disproportionately to proclaim a general state of inequality, much as in the “defining impurity” paradigm. Moreover, as Fontijn (Reference Fontijn, Timothy and Fernández-Götz2021) insightfully points out, “power requires others”: perhaps influenced by neoliberalism, a narrow focus on individuals ignores social interaction of all kinds.

The third critique goes to the heart of the “greatest hits” approach: it treats a subset of sites and cultures as representing the whole picture of European prehistory. How representative is this subset? Quite possibly, it is highly unrepresentative. One reason the same examples are repeatedly cited to illustrate prehistoric inequality may be that most other contemporary societies do not actually provide such evidence. If you were walking across Europe at a given moment, would inequality be normal? To return to the paradigm example of lavish Early Bronze Age (EBA) burials, such burials are found sporadically. In much of EBA Europe (as in most of the Mediterranean), the dead were not even commemorated in ways that preserved their social persona intact. Where individual burials were the norm—such as the huge EBA cemeteries at Franzhausen and Gemeinlebarn in Austria and at Arano in Italy—they usually show a much more restricted range of differentiation. To take one well-studied example, O’Shea’s (Reference O’Shea1996) analysis of the Maros villagers in Serbia/Hungary explicitly attempted to use burial data to find social inequality in the New Archaeology tradition. It succeeded in outlining social roles in a small community of a dozen or two families. Families differed in access to wealth, yet the range was very limited; there were multiple complementary social roles, and differentiation based on age and gender was more important than status (see also Žegarac et al. Reference Žegarac, Winkelbach, Blöcher, Diekmann, Gavrilović, Porčić and Stojković2021). It is hardly a picture of life driven by dominant “elites” or “chiefs”: it is much more complex and interesting than that.

For any period in European prehistory, you can always find inequalities of some kind if you search for them assiduously enough. That does not mean that they always represent the same kind of social phenomenon. Nor does it mean that inequality provided the only or dominant way of organizing social interaction, so that we can designate that period “inegalitarian” and close the book. Hence, let me present an alternative hypothesis: in all periods up to and including the Iron Age, most archaeological contexts do not provide convincing evidence of social inequality as a central principle of social organization. This hypothesis can be tested.

Inequality in the Prehistoric Central Mediterranean

Methods for Qualitative, Big-Picture Assessment

Assessing social inequality archaeologically is complex, and identifying relevant data depends how we define inequality itself. Here we are simply interested in a coarse-grained, broad qualitative assessment. And because it addresses an argument posed originally by New Archaeology social evolutionism, it seems appropriate to use New Archaeological evidential criteria. Table 1 lists a range of traits that classic New Archaeological sources (Peebles and Kus Reference Peebles and Kus1977; Wason Reference Wason1994) consider to be indicative of inequality. Such traits still provide the backbone of most archaeological analyses of inequality. New evidence is emerging from more recently developed methods, particularly stable isotopic and aDNA analyses, but it is not widely available enough to provide a general picture, particularly within any specific region. Every trait obviously indexes social inequality accurately in some circumstances. Equally obviously, each also affords counterexamples where archaeologists try to read generalized individual inequality into something that is heterarchical, collective, ambiguous, or contextual. Thus, including a trait here does not mean that its presence necessarily implies social inequality, merely that it has sometimes been considered as doing so. However, the exercise still gives a prima facie idea of whether there might be a case for inequality in any given period and what the preponderance of evidence suggests.

Table 1. Archaeological Criteria Used to Assess the Possible Presence of Social Inequality.

1 This criterion is omitted from the analysis here as textual records are lacking for all but a few of the Iron Age II groups.

Evaluating the entirety of European prehistory would be an immense task. As a sample area of manageable size, I review the prehistory of the Central Mediterranean, including Italy, Malta, and adjacent areas of Croatia, Slovenia, and France (Figure 1). This is one of the best-researched prehistoric sequences in Europe. It extends from Mediterranean islands to high Alpine peaks, includes maritime and continental zones, and connects mineral-rich zones, landscapes of transhumance, trans-Alpine trade routes, and colonial contacts with Eastern Mediterranean civilizations. Although every area of Europe has its own unique features, the Central Mediterranean provides an unusually diverse and representative sequence, indeed a microcosm of European prehistory.

Figure 1. The Central Mediterranean.

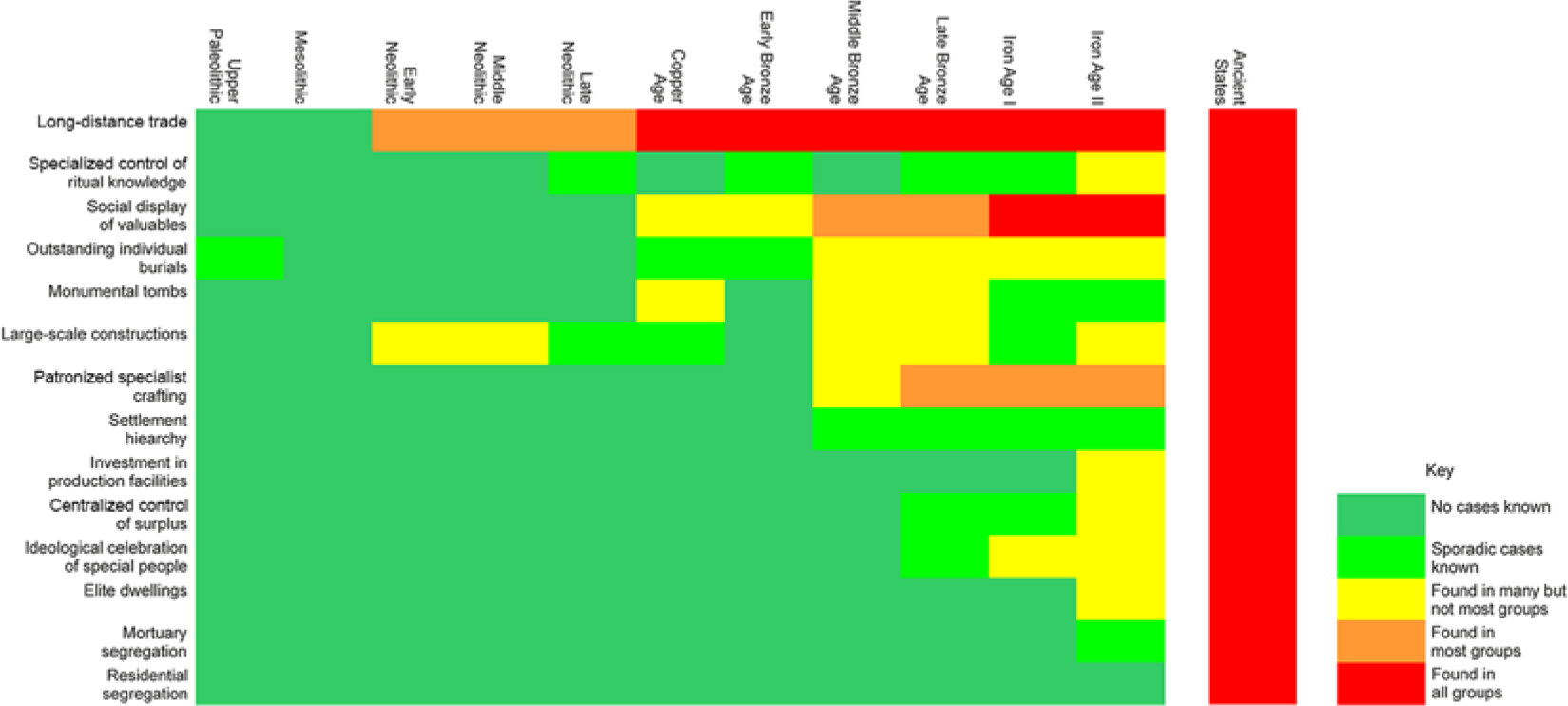

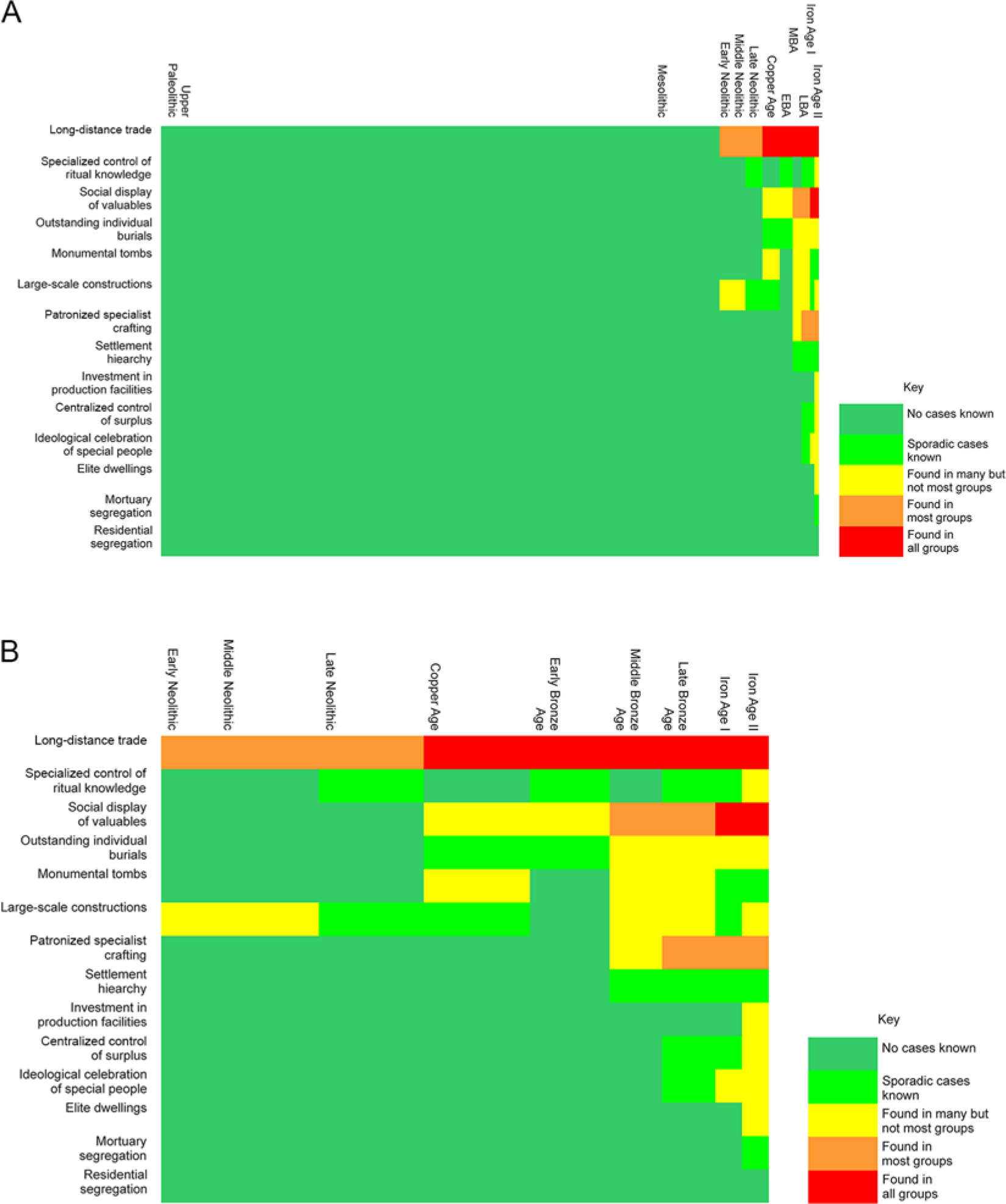

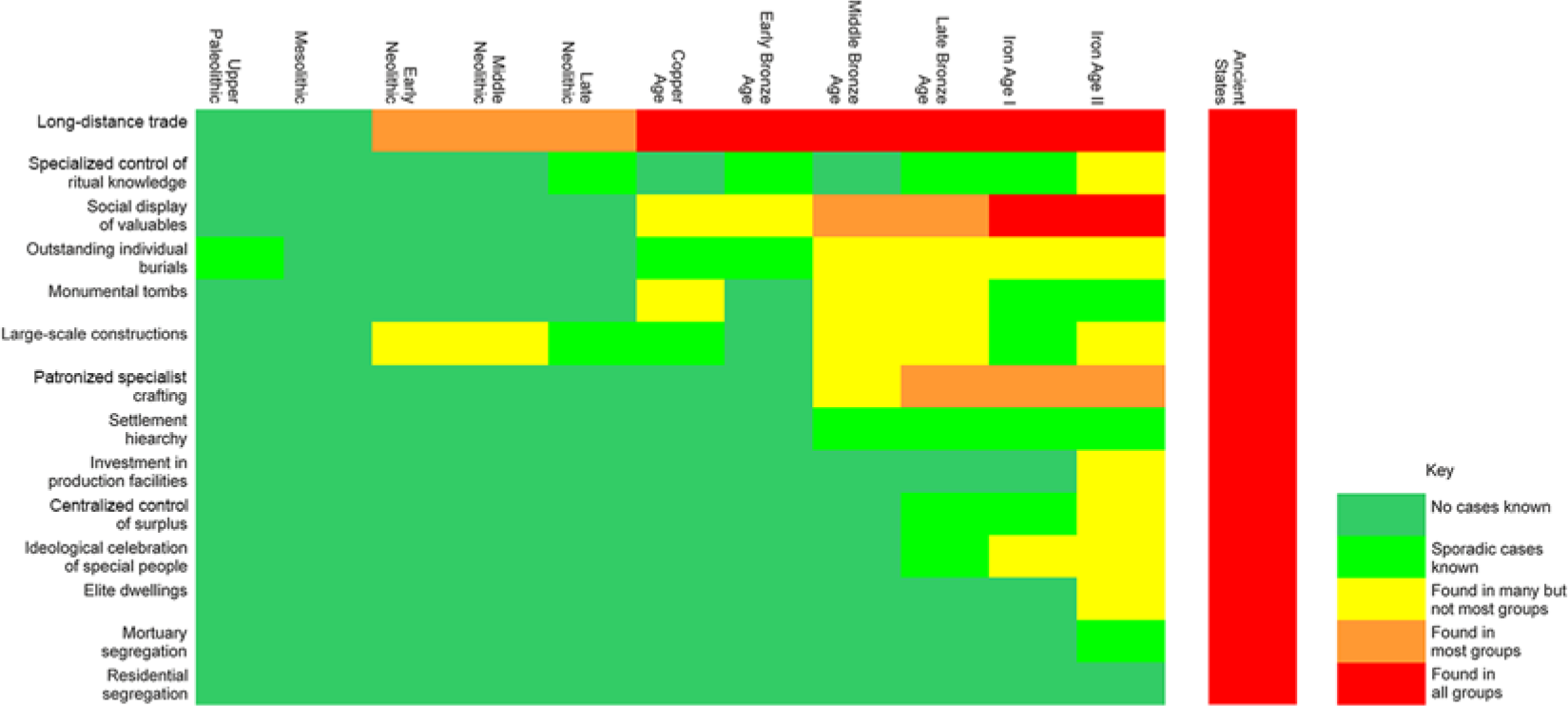

For the Central Mediterranean prehistoric sequence, the criteria listed in Table 1 were evaluated through a broad qualitative review (see Supplementary Text 1). For each period, each trait was categorized broadly: 0 = no cases known; 1 = sporadic cases are known, but it is not found in most groups; 2 = it is known in many groups; 3 = it is known in most groups; and 4 = it is found in all groups. These were tracked for conventional archaeological periods (see also Supplementary Text 1). Bases for qualitative assessments and some typical or important examples are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Results are presented in Figure 2. (For comparison, Figure 2 also includes a characterization of societies in which social inequality is unequivocally present, such as Mesopotamian city-states, ancient Egypt, the Maya, the Inka, ancient Rome, and medieval Europe.) However, archaeological periods may not represent the balance of human experience accurately; for instance, “periods” vary greatly in duration, from the 30,000+-year Upper Paleolithic to the 300-year Iron Age I, so that treating all archaeological periods equally valorizes change over stability. Hence Figure 3 charts the results by real-time chronological intervals.

Figure 2. Possible archaeological indicators of social inequality in Central Mediterranean prehistory. (Color online)

Figure 3. Possible archaeological indicators of social inequality in Central Mediterranean prehistory scaled according to chronological time: (A) Upper Paleolithic through Iron Age; (B) Neolithic through the Iron Age. (Color online)

Results: Most of the People, Most of the Time …

Does the preponderance of archaeological evidence support a picture of widespread, systematic inequality? Coarse-grained though this exercise is, the results are clear. When the project prioritizes finding inequality, as in the “greatest hits” approach, attention focuses on individual cases of its presence. But assuming that the clearest expression of inequality represents how most people actually lived everywhere or how they would have lived in an ideally evidenced, unilinear developmental narrative is simply a way of prioritizing inequality over equality in narrative.

In fact, when we flip the narrative and ask how most people really lived, the picture changes dramatically. The only “indicator” of inequality that is consistently found across deep time is the long-distance exchange in exotic objects, such as spondylus shell, obsidian, and axes. But such exchange is common in both nonhierarchical and hierarchical contexts around the world. Furthermore, although exotic objects were certainly valued, handled, assessed aesthetically, and sometimes ritually deposited, they do not seem to have been regarded as accessories for personalizing value; before about 3500 BC they were almost never deposited with burials. Moderate levels of ritualism may imply the presence of local ritual leaders, but there is no evidence that they held powers in other contexts. Similarly, skillfully crafted objects such as pottery may have been made by certain people with recognized special abilities, but there is no suggestion that such objects formed part of projects of political patronage and display.

Two suites of related developments appear in the fourth millennium BC in Central Mediterranean and in Europe as a whole. One is monumentalization of the landscape, evident in new kinds of sites: rock art, rock-cut tombs, statue-stelae installations, and megaliths. In varied local forms, monumentalization created landscapes of memory oriented around local origins, ancestors, and probably kinship. The other development is having new material objects, notably metals and weaponry, accompany new forms of burial, thereby presenting an individual with status-coded grave goods. But what is not present is equally important. Ritual systems imply ritual leaders, but there is no evidence that such people served as leaders with generalized capacities. Although there have been sporadic attempts to construe fourth- to third-millennium BC burials as containing “princes” or “chiefs,” burial evidence from Copper Age and Bell Beaker contexts shows much more uniformity than differentiation. Individuals with elaborate burials were more likely firsts among equals with unusual biographical circumstances (Dolfini Reference Dolfini2021). Such burials signal a critical innovation in personhood, demonstrating a generalized political status through gendered display—but not systematic inequality (Dolfini Reference Dolfini2020).

Early and Middle Bronze Age social prominence seems mostly to be about personal display (particularly in death) and about obtaining and circulating the suite of personal objects needed to do so. One relevant question, therefore, is to what extent this display implies any systematic institutionalized inequality. The real inflection point seems to be the later Bronze Age, from the mid- to late second millennium BC onward, when specialized workshops and places for trade, centralized collection of surplus production, imports and consumption of special objects, and a multitiered settlement hierarchy appear patchily in regions such as the terramare of the Po Valley, the Adriatic and southern Italian coasts, and the central Tyrrhenian area (Blake Reference Blake2014). They have been interpreted as signaling the transformation of traditional lineage-based societies into a nascent stratified society organized around bonds between patrons and clients (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015; Cazzella and Recchia Reference Cazzella and Recchia2021; Peroni Reference Peroni1996). Pan-Mediterranean trade networks also appear (Iacono et al. Reference Iacono, Borgna, Cattani, Cavazzuti, Dawson, Galanakis and Gori2022). Even so, such communities remained small and were based on face-to-face interactions among close-knit communities; their “elites” may have actually been ordinary people who were prominent in local kin segments (Vanzetti Reference Vanzetti, Meller and Bertemes2010, cited in Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015:173). It is only well into the first millennium BC in specific regions such as the Central Tyrrhenian that distinctions between “elite” and “non-elite” residences appear, along with potential differences in basic consumption, funerary segregation, and the ideological celebration of individuals or groups.

We can draw two principal conclusions for the prehistoric Central Mediterranean. First, for most of the people most of the time, some elements of social distinction were present, but they did not form the dominant principle of social organization. Indeed, if we turned the question around and ask, equally assiduously, Is there evidence for social equality? we would come up with a much more resounding “yes.” Trying to arrive at a single prehistory of inequality based on places where we feel it can be clearly discerned obscures the great diversity of experiences and historical pathways.

Second, social distinction changes its nature throughout prehistory. In some periods, it is manifest mostly in ritual knowledge or leadership of collective projects; in others, in the display of valuable personal items and embodiment of the ideals they symbolize; and in still others, in the accumulation of wealth and the control of economic infrastructure. In other words, inequality always formed one qualitatively defined element among others in a changing, heterogeneous system of social reproduction.

Prehistoric Europe: Outline of a People’s History

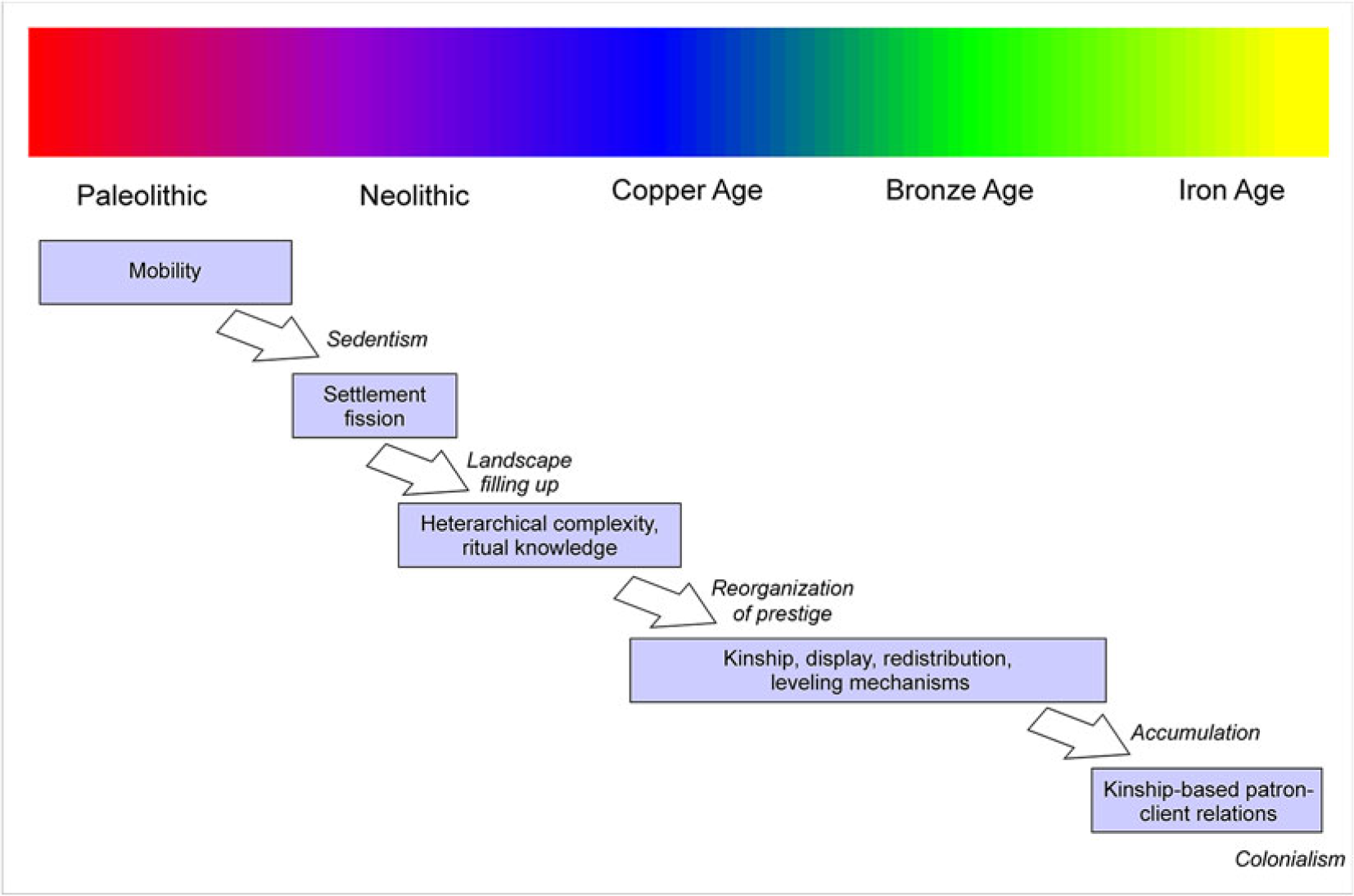

These insights direct us to conceptualize an alternative history of inequality—and of equality. A big-picture, bottom-up prehistory of both the Central Mediterranean and Europe more generally reveals how equality was actively maintained over millennia.

The Age of Mobility. Ethnographically, foragers often resolve conflicts simply by living in small, highly mobile groups that fission easily when tensions build up (Kelly Reference Kelly2013). Mobility effectively limits the accumulation of material differences and the potential for coercion. No doubt, there were social inequalities in Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Europe (Pettitt Reference Pettitt and Moreau2020; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Henderson, Czermak, Zarina, Zagorska, Lee-Thorp and Moreau2020), but they were limited in scope, probably by mobility and social sanctions. The result is an archaeological record characterized by small, short-term campsites (such as Pincevent and Star Carr, to name famous examples), cave occupations, and lithic scatters, evidencing millennia of stable, resilient forager life. This stability would be facilitated by the general practice, in all but rare inhumations, of dissolving the dead into the landscape, rather than preserving their memory. Perhaps relatedly, in Upper Paleolithic art at sites such as Lascaux and Altamira, there are virtually no representations showing humans hunting animals, in contrast to Bronze and Iron Age farmers’ art in southern Scandinavia and Alpine Italy, which frequently depicts individual hunters in action. This may reflect a strategy of spreading credit for hunting success among members of a group, rather than favoring potentially divisive individual boasting (see also Lee Reference Lee1979).

Internal Tensions and the Spread of the Neolithic. Perhaps the defining feature of the initial spread of farming through Europe is its remarkable speed. Impressed and Cardial Ware settlement spread along the Mediterranean coastline from the Adriatic to the Atlantic in about 500 years (6000–5500 BC). The expansion of Linear Pottery culture (LBK) across northern Europe between Poland and France took about the same time (5500–5000 BCE). Although aDNA evidence has clarified that the initial Neolithic spread involved both the expansion of Near Eastern populations and the integration of local hunter-gatherers, the mechanism was not a “wave of advance” that saturated the landscape demographically; instead, it was a rapid, targeted “leapfrog” or “enclave” expansion (Bogucki Reference Bogucki and Price2000; Robb Reference Robb2013; Zilhão Reference Zilhão and Price2000). Villages budded off new settlements readily, targeting the next available patch of a highly selected environment. What has never been explained is why they did so: What social mechanism drove such rapid fissioning?

Sedentism opens up new possibilities for social division (Zilhão Reference Zilhão and Price2000); people tethered to places, crops, and labor investments cannot move away flexibly as social tensions build up. In Zilhão’s model, Early Neolithic villages were unstable, prone to increasing internal tensions and conflicts, perhaps generationally or over rights to land. Inevitably, a village would fission, with a faction establishing its own settlement in available land close by. In a lightly occupied landscape, the faction could target its preferred environment selectively. What held groups together was not political mechanisms but cultural uniformity, the shared habitus visible in the remarkably homogeneous LBK and Impressed Ware material culture. Groups may also have been integrated without hierarchy by collective projects such as digging a village ditch or raising the massive timbers of a longhouse. The result would be a chain of small, identical settlements snaking rapidly from coastal plain to coastal plain or from river terrace to river terrace. Thus, the unrecognized motor of the Neolithic spread was villages fissioning to discourage the internal buildup of tensions or hierarchy.

The “Missing Millennium” of the Neolithic: Radical Heterarchy and the Ritual Mode of Production. Social evolutionary accounts often fast-forward through the middle and later Neolithic, a period when apparently little of importance happens. Yet “ordinary village life” is full of cultural politics and counterpolitics. Moving away from social problems only works when land is freely available. As the Neolithic matures and landscapes infill, other strategies develop.

The signature of middle- to later Neolithic politics is radical heterarchy: we can identify multiple arenas that could potentially be harnessed to power-play agendas but instead are maintained as separate spheres of value. Gardening and herding were important skills. But the limiting factor on how much food people produced and accumulated was not ecological or technological but social, as people worked to meet socially defined needs (Halstead Reference Halstead, Halstead and O’Shea1989); in such small-scale groups in which security ultimately derived from social relationships, not wealth, it is likely that norms of sharing and reciprocity and sanctions such as ostracism curbed overproduction for political gain. In crafting throughout Neolithic Europe, we find expertly made things. Pottery repertories include vessels made with visible, even ostentatious skill: pots were precisely thinned, flawlessly burnished, and ornately decorated. Such products were probably made by recognized practitioners prominent in local communities of practice. But these were “specialists” without patrons; skill was exercised for its own sake, not to make “prestige goods” yoked to political projects. In many regions such as Middle Neolithic southern Italy, highly local styles proliferated. Stylistically, most Neolithic pottery involved producing not identical, competitively evaluated products but creating difference through the creative recombination of a decorative repertory to create styles, substyles, and local micro-styles that would have been legible at multiple levels down to the individual practitioner. It was a material culture that created heterarchical relations (Robb Reference Robb2007).

Trade provides a parallel example. Neolithic trade systems moved stone axes from the Alps to the Atlantic and Mediterranean, spondylus shell from the Black Sea or Aegean to Germany, and obsidian more than 1,000 km from its sources on Mediterranean islands. Axes were used both practically and ritually; they must have been displayed, discussed, and caressed (Pétrequin and Pétrequin Reference Pétrequin and Pétrequin1993). Spondylus shell rings were used to construct diverse, decentralized, enchained social relationalities (Chapman and Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007). Trade in such objects created social relations, yet none involved clear hierarchies. We have little idea why people wanted obsidian; it had no clear functional use, nor was it deposited in special contexts or involved with projects of identity (for instance, the presentation of self in burials; Robb Reference Robb2007). As with crafting, trade produced valuables and value for diverse, unlinked social projects.

Ritual was pervasive in Neolithic societies. Burial involved diverse, complex processes to reconstitute the moral community on a spiritual plane and cope with varied circumstances of death. Neolithic groups had always had collective building projects that integrated communities; for instance, making village ditches or palisades. When they began to make large ritual constructions, such as northern European enclosures at Sarup, Denmark, and Goseck, Germany, in the fifth to fourth millennia BC, this opened a new arena of social action. Ritual leaders curated valuable knowledge and managed large projects. In a society without developed coercive powers, such leaders must have led as long as they could motivate a constituency and within the limits granted them by their constituency.

This usefully frames the social role of ritual. Large collective projects were not the leader’s project, they were “our project”: the construction of monuments built communities. The same was true of feasting events; someone coordinating surplus and administering a feast may have been more a servant than a master. Provisioning work parties and feasts may have been a form of forced sharing to keep leaders poor or dependent on their constituents. The lack of evidence for the collection and administration of surplus, differential consumption, and mortuary commemoration of individuals all underlines how specialized ritual authority provided a narrow, not generalized, domain of authority. The trajectories of individual ritual systems give a sense of the boundaries of such a world. Ritual cycles of 200 to 500 years show continual tinkering by the local Megalith Committee as a group worked through an envelope of possibilities. Occasionally—in Stonehenge, Avebury, Carnac, and Malta—a system would go supernova, but even large works may not imply rigid hierarchies (Cazzella and Recchia Reference Cazzella and Recchia2015). The limiting factor is political structure: the larger the system, the more fragile it becomes, and they do not remain at their extended peaks for long.

Overall, Neolithic Europe exemplifies the “ritual mode of production” (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002): politics, trade, and crafting served the needs of ritual and social reproduction, rather than their serving politics. Norms of Neolithic culture and the heterarchical distribution of knowledge and authority discouraged any one field of action from controlling others or providing a platform for domination. Many Neolithic fields of action channeled social energy into projects of knowledge, creativity, skill, social reproduction, and identity—but they all remained different projects, ends in themselves rather than reduced to a political functionalism of some generalized structure.

Ancestors and the Ambiguity of Kinship. Monuments are not merely big constructions to be project-managed; they create landscapes of memory and relationships based on shared ancestry. This became widespread in different forms throughout fourth- to third-millennia BC Europe. This may have emphasized the rise of kinship as a major principle of group identity. As production changed with innovations in plowing and herding, an increasing emphasis on kinship may have helped assemble people into larger formations to meet the needs of an increasingly diversified use of landscape.

Here it is worth noting the inherent political ambiguity of kinship (see also Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015:156). Kinship creates relations of shared identity, solidarity, and mutual support. At the same time, it also provides ranked oppositions: elders versus juniors, lineal versus affinal kin, and central or senior lineages versus peripheral or junior lineages. Kin relations thus always contain the potential for both equality and inequality. However, kinship provides a flexible rather than deterministic system. People participate in multiple kin relationships and continually reshape their genealogies and memories creatively. In this period, on balance, kinship seems to swing much more toward equality and solidarity than toward internal distinction, as suggested by the mostly uniform burial treatment and merging bodily substance in tombs. People could vote with their feet and change allegiance if they felt that kin group leaders overstepped or were unresponsive to their needs.

Display, Feasting, and Bronze Age Collectivities: “Kings,” “Chiefs,” or Farmers-and-Kinsfolk-in-Chief? New idioms of politics emerge in the Bronze Age. The most obvious one is individual display. Recurrent combinations of objects characterized males and females. These included things worn on the body (ornaments, clothing, armor), things habitually associated with it (weapons, knives, and spindle whorls), and things related to consumption (food and drink habits and paraphernalia; Robb and Harris Reference Robb and Harris2013). Such objects are known mostly from burials, but iconography and use wear suggest that people also used them habitually in life. The warrior was a particular form of social display (Harding Reference Harding2015). Such assemblages are sometimes interpreted as evidencing the “origins of patriarchy” (Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005), but clearly, Bronze Age gender and potential gender inequality were much more complex than any simple reading: there were distinct, complementary male and female repertories, and within each there was the potential for both solidarity and distinction. Such widespread, ordinary objects provided a diffuse, habitual idiom of comparative personhood that mostly expressed social adequacy rather than prominence, but which less common, upscale versions (sometimes including materials such as gold) built on. Thus, access to everyday objects one could obtain and display was central to social distinction in this period. Ostentatious burial, participating in commensality, and providing leadership in feasts and warfare may also have been important.

Narratives of Bronze Age inequality focus on infrequent, rich burials, but in such small-scale, face-to-face societies, the most important limited resource for work, security, and personhood was people: real social capital lay not in the gleaming objects that fascinate us but in the social relationships these objects negotiated, symbolized, or hid. How did display and performative personhood fit into an overall social formation? Almost nowhere in Bronze Age Europe outside the Aegean is there evidence for the large-scale centralized storage and control of produce or for the accumulation of wealth beyond personal display objects. Nor is there evidence that “elites” lived much differently than anybody else; for instance, the glorious picture of the Argaric Bronze Age afforded by burial evidence is not substantiated in other spheres (Gilman Reference Gilman, Berrocal, Sanjuán and Gilman2013). aDNA analysis of Bronze Age burials shows possible differentiation between more important and less important lineages (Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik, Massy, Knipper, Wittenborn, Friedrich, Pfrengle and Burri2019; Žegarac et al. Reference Žegarac, Winkelbach, Blöcher, Diekmann, Gavrilović, Porčić and Stojković2021) but among people living closely together in very small groups and sharing most conditions of life. By and large, rather than heroic “kings,” we might imagine such people as central members of kin-based extended rural families. Whether they were goading the plow oxen or spreading manure, they lived in the same farmhouses, ate the same food, and thought about the same tasks as everybody else.

In such a social landscape, informal cooperation, reputation, and gossip, not abstract institutionalized roles, would have been vital. This constrained and directed potential inequality:

• Display is a self-limiting form of differentiation. There is a limit to how many shining objects one can hang on one’s body. Ethnographies of face-to-face societies often note valuable objects such as headdresses being collective property, borrowed, or even hired for an occasion, rather than closely associated with individuals. When ostentatious consumption involves putting valuables beyond reach, as in watery hoards, a pan-European Bronze Age innovation (Bradley Reference Bradley, Fokkens and Harding2013), or in burials, they pass out of possession, resetting levels of wealth accumulation. Indeed, depositing such attributes so they could not be retrieved may have been a leveling mechanism to limit their use as ongoing economic assets of a dominant family or faction.

• Whose mound or feast was it? The assumption that a burial event or monument refers principally to an individual inhumed within it, rather than the group making or performing it, treats a sectional point of view as exclusive and universal. People may have felt that a mound or feast represented “our group,” rather than a particular protagonist; Metcalf and Huntington (Reference Metcalf and Huntington1991) provide a classic ethnographic cautionary tale in which an Indonesian group wanting to stage an elaborate funerary feast used the death of an insignificant, peripheral member as a convenient occasion for it. Similarly, although feasts provide a means by which ambitious leaders can attain prominence (Dietler and Hayden Reference Dietler, Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2001), ethnographic accounts suggest that organizing them involves a huge amount of work and that the feast may be seen as “belonging” not to the organizer but to the group contributing the resources.

• Leaders were tied to members of their household and group by bonds of kinship, history, and close daily cooperation; “non-elites” had claims of solidarity, obligation, and a stake in collective enterprises. It may be an unflattering self-commentary that we picture leaders as perceiving followers principally as a source of labor and production, rather than as objects of familiarity, affection, loyalty, or responsibility. Collective identities may have worked in very concrete ways; for instance, herds may have been considered not as unrestricted individual property but as belonging to a kin group that had to collectively approve how animals were managed and consumed.

• Leader–follower bonds may have provided the ultimate factor curbing Bronze Age leaders’ ambitions. Aspiring leaders needed to perform leadership, including generosity—something that may have kept successful leaders poor or, at least, circulating wealth rather than accumulating it. Maintaining such bonds may have motivated institutions of conviviality (and the resulting ceramic assemblages). If a leader did not treat a client well, he risked not only the client’s withdrawal of support but also “reputational damage” and disaffection from others. It may be relevant that many Bronze Age settlements were short-lived and relatively insubstantial rather than requiring substantial investment in houses and facilities; people may have kept open the option of moving to other groups as a check on social control.

Such considerations suggest that Bronze Age display does not represent a stable, entrenched system of inequality. Rather, it may have been a functionally egalitarian world, with the display of bling providing an index of a leader’s salience and ability to deliver services, as well as a personification of a group’s well-being. Moreover, if Bronze Age display was a politico-economic game for attaining status—rather than, say, a way of performing a specific culturally constituted idea of personhood—it operated within strong social constraints. In a small social world of personal relationships, conceptualizing the relationships that constructed leadership as an instrumental “masking” ideology intended to deceive may be alien to how the participants themselves—both leaders and followers—would have experienced it. Instead, the social order would have emerged from a negotiation of interests, some sectional and some collective, in a way not easily classifiable as “egalitarian” or “hierarchical.”

The Iron Age continued Bronze Age trends, although the level of ostentatious display often decreased, undercutting any narrative of a continual increase in inequality. In much of Europe, much larger cemeteries suggest that communities increased in size, and this may have placed strains on kinship as an integrating idiom. In some cemeteries—for instance, Osteria dell’Osa (Bietti Sestieri Reference Sestieri and Maria1992)—there may be emerging differentiation between central and peripheral members of a kin group. There is also evidence for slavery in some areas, which provided another route to recruiting subordinate labor (Arnold Reference Arnold, Blair Gibson and Geselowitz1988). Stable isotopes show that in some cases, people buried with “elite” treatment may have consumed diets with more animal protein (Knipper et al. Reference Knipper, Meyer, Jacobi, Roth, Fecher, Stephan and Schatz2014; Le Huray and Schutkowski Reference Huray, Jonathan and Schutkowski2005). If kinship was associated with economic production, this may have opened an exit route into a world in which inequality was increasingly based on the accumulation and control of economic resources by central members of the productive unit (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015; Cazzella and Recchia Reference Cazzella and Recchia2021; Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2001, Reference Pacciarelli2016; Peroni Reference Peroni1996).

Thus, archaeologically less ostentatious Iron Age societies may have been more susceptible to inequality, because it could have been entrenched in the low-key control of productive resources, rather than performed individually. Even so, these remained small-scale, face-to-face societies, and negotiation and the power of the collectivity must have still been important. For example, forming towns was not inevitable or obviously advantageous but must have been contingent on the consent of the people deciding to join or withdraw from them (Jinoh Kim, personal communication 2024). As a recent general review highlights, much of Iron Age Europe may have worked on heterarchical principles (Moore Reference Moore, Haselgrove, Rebay-Salisbury and Wells2023). Even the most apparently hierarchical hillforts, “elite” burials, and proto-urban sites may actually be evidence of horizontally organized communities (Arnold Reference Arnold, Timothy and Fernández-Götz2021; Moore and González-Álvarez Reference Moore, González-Álvarez, Timothy and Fernández-Götz2021).

Colonialism and Equality? A generation of postcolonial archaeology has explored how Europeans creatively managed the colonial encounter with Mycenaeans, Greeks, Phoenicians, and, later, the Romans (Dietler Reference Dietler2010; Hodos Reference Hodos2020; Mac Sweeney et al. Reference Mac Sweeney, Sánchez, Kotsonas, Waiman-Barak, Osborne, López-Ruiz and Hodos2023; van Dommelen Reference Van Dommelen, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Woolf Reference Woolf1997). Responses to colonialism were remarkably varied. Around the Central Mediterranean, for example, they included simply opting out of contact with traders or colonizers; incorporating foreign techniques into local production (for instance, making “Mycenaean” pottery in southern Italy); dictating market conditions that traders conformed to; integrating foreign items and customs selectively into local practices; maintaining multiple or mixed political and cultural identities, often through intermarriage; and living on the margins of colonial systems or in the interstices of state attention to benefit from new opportunities while evading control.

What has been less explored is how this intersected with equality and inequality. Many Iron Age societies became more hierarchical in the period of intense contact with colonizing groups; the Iron Age II sees the rapid formation of class-based urban societies in Tyrrhenian Italy, Sicily, Puglia, and elsewhere. However, it may be simplistic to blame social stratification on colonial contact. Colonialism may have presented different challenges and opportunities for people in different structural positions. Responses to it may have been aimed as much at curbing the growth of power within indigenous societies as at preventing encapsulation or subjugation by the foreign. Central questions include the following:

• Did local groups set the terms of contact to limit the growth of indigenous elites; for instance, insisting that a would-be leader had to work through traditional, local forms of relationships and authority?

• Did colonialism undercut traditional forms of hierarchy; for instance, by making exotic goods formerly circulated through elite networks more widely available or by introducing new forms of value?

• Did colonial contact afford new opportunities; for instance, for economic participation independent of local relationships and developing urban settings as places where one could fashion new identities?

• Were “Greek,” “Roman,” or “local” not primordial terms of identity but instead created or heightened in particular settings, perhaps in ways that undercut local forms of distinction?

• Did colonialism create frontier zones that could act as preserves of equality; for instance, zones of state inattention, areas of flexible identities, and places of escape?

Colonial encounters may have simultaneously expanded inequality and created new possibilities for resisting it. Exactly how is a problem yet to be investigated.

Conclusions

The goal of this article is simply to introduce ideas and interpretations; fully exploring them would take much more extensive treatment. However, we can summarize its basic theses briefly.

Empirically, there was much less political inequality in prehistoric Europe than archaeologists often suppose. In all periods, there were elements of inequality, but archaeologists have focused on them disproportionately, taking selected kinds of evidence (notably burial evidence) at face value as representing a total social order and using a few cherry-picked, usually atypical instances to typify the general situation throughout Europe. What was important was not the presence of any social inequality at all, but how it was integrated into a social order. “Was society hierarchical or inegalitarian?” is the traditional question to ask, but it is the wrong one and guarantees a polarized, distorting answer. Because of the way inequality and equality are embedded in cultural values and social relations, any system for expressing inequality short of a totalitarian regime is also a system for channeling, containing, and limiting it. Up to the end of prehistory, inequality was rarely the major structuring principle in most societies. Instead, it was part of a complex social order involving a heterarchical and often ambiguous mixture of multiple principles of social reproduction.

Based on this conclusion, we can see European prehistory in a new light. In each period, major archaeological features do not simply reflect power strategies by ambitious politicians. They may represent culturally constituted ways of seeking locally defined forms of power. Equally often, however, they reflect both local forms of power and resistance to the concentration of power or ways of structurally limiting it. Or, because power is collaborative and constitutive, as well as dominating, people took forms of power specific to each period and used them to ground forms of social action accessible to and inhabitable by different kinds of people, not merely the political protagonists we imagine theoretically.

The result was as much a history of equality as of inequality. As the landscape of action changed, so did ways of both developing and limiting power (Figure 4). These defined worlds of diversity, not uniformity across Europe, as local societies explored what was socially possible. In the broadest terms, the most typical features of the archaeological record display working against power as much as working in pursuit of it. In the world of Paleolithic and Mesolithic foragers, an aesthetic of mobility gave people the means to respond to tensions and problems within groups. With such an ethic, newly sedentary Early Neolithic groups became brittle and fissioned readily, budding off new settlements to spread rapidly into lightly occupied areas. As such areas filled up after 5000 BC, a more complex Neolithic developed. It involved many different features, but the common denominator was developing specific domains of value linked to specific fields of action—crafting, trade, ritual, and others—that remained structurally independent. The result was the typical texture of Neolithic archaeology characterized by complex rhythms of everyday lived experience, highly skilled stylistic involution in crafts, long-distance trade systems for culturally important objects, and cycles of local ritual histories—all juxtaposed in a heterarchy of distributed value. Structural constraints, such as the lack of political integration, imposed limits on growth and meant that attempts to leave the envelope of the possible failed sooner or later. Economic and social reorganization in the fourth to third millennia BC introduced a new emphasis on kinship relations and on a generalized, politicized, gendered form of prestige. The new habitus involved personal display as a way of enacting political personhood—a common Bronze Age form of action. But such display did not signify broader, underlying systems of inequality, and there were many constraints that made it self-limiting and kept the overall tenor of society horizontally oriented. This remained true through the Iron Age, although increasing community size and the beginnings of accumulating wealth or control of resources placed increasing tensions on kinship as a traditional form of organization. The impulse to inhibit the growth of inequality persisted into the historical era; colonial contact and the rise of cities may have provided both openings for inequality and new opportunities for equalities.

Figure 4. Changing modes of creating equalities in prehistoric Europe. (Color online)

Deep-history narratives often valorize inequality as a key evolutionary threshold, as something central to our modern world, as progress or change rather than a static past, and, not least, as something that generates eye-catching finds, funding, and dynamic storylines. But perhaps we should flip the frame around the picture to recognize the values of the past, rather than the teleology of today. It is traditional to see a history of millennia without inequality as flatlining, as a failure to progress, as something about which we have little to say. But this reflects mostly our incapacity to imagine such a world. It does not do justice to the ways in which people actively built tactics for discouraging the growth of hierarchy in their ways of life. And these tactics worked effectively for millennia. Recognizing this means recognizing millennia not of stagnation but of stability, not of regress but of resilience. It means recognizing equality not as a passive, natural state but as a pervasive, hard-fought, human achievement—and one we could learn to imitate today.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to audiences and colleagues at Cambridge, Oxford, University College London, the University of Kiel, and the University of Copenhagen for comments on the seminar on which this article is based. I am also grateful to Andrea Dolfini, Giulia Recchia, Guillaume Robin, Jess Thompson, and Alessandro Vanzetti for informative conversations on Italian prehistory and to Emma Blake and several reviewers for comments that improved this article. I am grateful to Andrés Troncoso for the Spanish translation of the abstract.

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by European Research Council Advanced Research Grant 885137, “Making Ancestors: Politics, Ritual, and Death in Prehistoric Europe.”

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2025.19.

Supplementary Text 1. A Note on Sources.

Supplementary Text 2. A Comment on Periodizations and Chronology.

Supplementary Table 1. Approximate Concordance between Periods and Chronological Intervals.

Supplementary Table 2. Tabulation of Archaeological Data.