1. Introduction

We are living in an era characterized by multilingualism, global mobility, superdiversity (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2010), and digital communications. Mobility and multilingualism, however, have long characterized most geolinguistic contexts, including those where monolingual ideologies have influenced the formation of contemporary nation states (Cenoz, Reference Cenoz2013). As language is a pillar of both curriculum and instruction, in many academic spaces around the world efforts are on the rise to acknowledge the colonial origins of English, decenter the dominance of Standard English(es), and decolonize knowledge production (e.g., Bhambra et al., Reference Bhambra, Gebrial and Nisanciuglu2018; de Sousa Santos, Reference de Sousa Santos2017). Additionally, many ‘inner circle’ (Kachru, Reference Kachru and Mesthrie2001) Anglophone contexts have long witnessed the centrifugal forces of multilingualism. Yet what prevails in institutional academic contexts is a centripetal pull toward what has been captured in phrases such as ‘linguistic mononormativity’ (Blommaert & Horner, Reference Blommaert and Horner2017) or ‘Anglonormativity’ (McKinney, Reference McKinney2017). Nowhere is this pull more evident than in the sphere of writing for publication, relentlessly construed as an ‘English Only’ space, as exemplified in Elnathan's (Reference Elnathan2021) claim in the journal Nature: ‘English is the international language of science, for better or for worse.’

In this position paper, we set out to challenge both the reality and desirability of continuing to configure academic/scientific knowledge production and exchange as an ‘English Only’ space. We explicitly borrow the term English Only from the movement in the United States – although this impulse is evident in many parts of the world (see, e.g., Phillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, Reference Phillipson and Skutnabb-Kangas1996) – that aims to erase the multilingualism that predated settler colonialism and has persisted throughout waves of immigration. The tenets of the English Only movement – that English plays a unifying social role, fosters ease of communication, and empowers those who use it in other ways (Crawford, Reference Crawford2000) – resonate uncomfortably with the anointing of English as the privileged language of knowledge dissemination by policymakers (Durand, Reference Durand2006), researchers, instructors of (English) language and academic literacy, and many students and scholars themselves (e.g., Cook, Reference Cook2017). The push over the last few decades for multilingual scholars to publish particularly in specific indexed English-medium journals stems from the neo-liberal imperative for increased global science and technology research output. In rhetorical if not actual terms, such research output tends to be equated to increased economic productivity (Leydesdorff & Wagner, Reference Leydesdorff and Wagner2009). The commonplace that English is used in 90% or more of academic journal publications (e.g., Hernández Bonilla, Reference Hernández Bonilla2021) is often used to justify a hyper focus on the holy grail of high-status (English-medium) indexed journal articles. This focus obscures the considerable scholarly activity that continues to take place around the world in multiple languages, signaling the value these languages have for academic writers as well as readers. The global reality of multilingualism across domains (May, Reference May2013), not least the academic, calls into question the naturalization of English as the privileged language of publication.

In this paper, we argue that it is time to put English in its place by shifting the emphasis to the multilingual realities inhabited and enacted by scholars around the world. By ‘multilingual realities’, we mean both practices that involve the use of languages as relatively discrete semiotic resources (e.g., talking and/or writing ‘in Spanish’ as compared with talking and/or writing ‘in German’) as well as translingual practices (after García, Reference García, Skutnabb-Kangas, Phillipson, Mohanty and Panda2009; Williams, Reference Williams1994) involving the mixing of linguistic/semiotic elements in acts of spoken or written communication (see Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curryin press). We view multilingualism in academic contexts as encompassing not only the use of ‘standard’ varieties of named languages (e.g., English, Spanish, Russian) but also ‘non-standard’ or vernacular varieties (Strauss, Reference Strauss2017). This point surfaces the problematics of labelling and categorizing language(s) as descriptors of the semiotic resources being used across contexts, recognizing that labels are as much artifacts of historical and political forces as descriptors of linguistic variation. In this paper, we use a number of terms to signal the positionality of language(s) in what can be described as the ‘economies of signs’ within academic publishing (Lillis, Reference Lillis2012, after Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2005), which whilst contested, help make visible certain relationships: for example, ‘local’ and ‘local/national’ to refer to language(s) used in particular geolinguistic locations that also have variable relationships to dominant, official, and ‘world’ languages (e.g., Catalan, Hungarian, Portuguese; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010); ‘indigenous’ to refer to pre-(Western) colonial languages that occupy a subordinate position within the dominant economy of signs (McCarty & Nicholas, Reference McCarty and Nicholas2014, p. 109); and ‘home’ to refer to the language(s) people use in everyday domains of practice, which are often positioned as subordinate to other official or dominant languages (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2010).

We view academic literacy practices as emerging from the repertoires of semiotic resources that multilingual scholars fluidly draw on in their/our communications.Footnote 1 We argue that such resources should be explicitly acknowledged as legitimate in not only the processes of knowledge production but also in academic outputs. The position we set out in this paper is supported by considerable evidence about multilingual knowledge production practices, evidence that tends to be downplayed or ignored in many discussions of global academic publishing. In particular, we draw on research findings from our 20-year longitudinal ethnographic study of the writing and publishing practices of 50 multilingual scholars in southern and central Europe, Professional Academic Writing in a Global Context (PAW), as well as bibliometric studies and research by other scholars. From early in the PAW project, even while focusing on the role of English in twenty-first century academic communications, we have documented how multilingualism is woven into participants’ oral and written research communication practices (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2004; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2006a, Reference Lillis and Curry2006b, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Reference Lillis and Curryin press).

Of course, English-medium publishing has a valuable place in the academic output of many scholars, as we and others have extensively documented (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2014; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010). However, this use of English often takes place within the context of multilingual practices, and multilingualism in terms of outputs remains an active and important dimension of global knowledge production, as shown by the bibliographic data we discuss in the next section. In this paper, we argue for a more comprehensive understanding of scholars’ practices and aspirations for linguistic media in academic communications. We contend that scholars around the world should be free to choose communicative means for their/our work without concern for the pressures of academic evaluation regimes and/or the hegemonic ideologies of English. This position is grounded in the principles of academic freedom and linguistic human rights that do or should underpin scholarly work (Moore, Reference Moore2021; Skutnabb-Kangas, Reference Skutnabb-Kangas, Tiersma and Solan2012).

In what follows, we sketch out the scope of multilingualism in academic publishing, discuss how multilingualism characterizes many scholars’ research practices, explore scholars’ commitments to publishing in local/national and regional languages or bi/multilingually, and outline approaches to supporting the production of multilingual academic knowledge. At a minimum, these may include reconsidering the taboo against the practice of ‘dual publishing’ and instead valuing the goal of ‘equivalence’ in publishing by multilingual scholars (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010). We discuss the affordances of networked activity as well as online translation tools and foreground the value of pedagogies drawing on translation studies and translingualism (Gentil, Reference Gentil2019; Gentil & Séror, Reference Gentil and Séror2014). Overall, we advocate for scholars to be able to exert greater agency in choosing the language(s) of academic dissemination, for evaluation regimes to explicitly acknowledge and reward multilingualism, for researchers to examine more robustly the role of all languages and varieties in knowledge production, and for instruction in academic language and literacy to encompass the greater use of multiple languages.

2. Multilingualism as the hidden norm of academic publication

Around the world, approximately 10 million scholars (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2019) produce more than 3.5 million journal articles per year in multiple languages (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Watkinson and Mabe2018). Precise numbers for academic publishing across all languages are hard to obtain because of how numbers are tallied. Research articles tend to be more systematically counted because they are more visibly included in evaluation metrics, while practitioner-oriented and other types of articles, book chapters, and books are less consistently tallied.Footnote 2 In addition, variations in how citation indexes or journal directories tally publications can result in very different pictures of global knowledge production being created (Nygaard & Bellanova, Reference Nygaard, Bellanova, Curry and Lillis2018).

Unpacking the statistic that English is used in more than 90% of academic articles sheds light on how the counting of publications is skewed. Comparing coverage by the UlrichsWeb Global Serials DirectoryFootnote 3 with prominent journal citation indexes – the Web of Science (WoS) (e.g., its Science, Social Science, and Arts & Humanities Citation indexes) and Scopus – shows that these indexes cover only two-thirds of the 49,000 active, peer-reviewed, abstracted/indexed academic journals listed in Ulrichs (Scopus, 2021; https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/; UlrichsWeb.com as of October 2021). Additionally, assumptions about how extensively English is used in the smaller selection of journals covered by the WoS and Scopus indexes need to be questioned, because the threshold for inclusion in these indexes is only the use of English in article titles and abstracts, rather than in the whole text. As a result, journals that predominantly use other languages in the body of articles are often categorized as English-medium, thus inflating the number of English-medium publications (Liu & Chen, Reference Liu and Chen2019). In addition, considerable bibliometric research on language use in academic publishing relies only on WoS and Scopus data (e.g., van Weijen, Reference van Weijen2012) to support the claims being made. UlrichsWeb classifies a smaller number of journals as using some or all English at 80% (UlrichsWeb.com, as of March 2021). The remaining 20% comprises more than 6,600 journals mainly published in other languages, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. UlrichsWeb coverage of journals published in languages other than English (ranked by largest number)

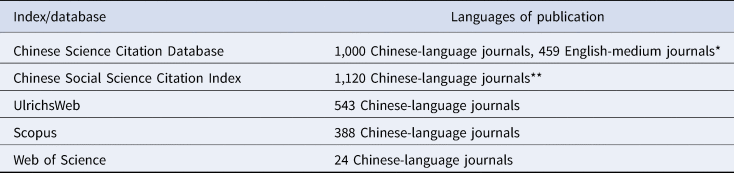

In addition to these publications, many other academic journals are produced in many languages, as are bi/multilingual journals. While it is difficult to provide comprehensive figures, this greater activity is attested by the existence of some 600 indexing and abstracting services (UlrichsWeb.com) for journals produced in local languages or in particular global regions, signaling their value to researchers and to the institutional evaluation regimes tracking these publications. As an example, Table 2 compares the coverage of journals published in Chinese or in China, currently the top producer of academic journal articles, by different indexing services.

Table 2. Coverage of Chinese journals in various indexes/databases

Thus, despite China's push in recent decades for scholars to publish in high-status English-medium journals, this has been accompanied by state-level imperatives to publish in Chinese as well (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Beckett and Huang2013). Indeed, Zhang and Sivertsen (Reference Zhang and Sivertsen2020) note, ‘Most scientific publications are still published in Chinese’ within China; further, open-access journals published in China also predominantly use Chinese (Shen, Reference Shen2017).

Similar discrepancies exist for other languages used in publication between what is included in high status indexes and other lists of publications. As another example, the Arabic Citation Index, launched in 2020 as a partnership between Clarivate Analytics and the Egyptian Ministry of Education, shows 290 journals produced in Arab League countries, with 93% of articles using Arabic (Clarivate Analytics, 2018; El Ouahi, Reference El Ouahi2021). The WoS, in contrast, covers only 146 Arabic-language journals (El Ouahi, Reference El Ouahi2021), while UlrichsWeb lists 107 journals. This pattern holds for journals published in Thailand, Korea (Kim, Reference Kim2018), Russia (Smirnova et al., Reference Smirnova, Lillis and Hultgren2021), and other global areas. Regional indexes such as Latindex (Online Regional Information System for Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal; Latindex.org) and SCIELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online; www. Scielo.br) cover journals published in Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula, many of which are open access, and most of which are excluded from more prestigious indexes (see Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2018, Ch. 1).

The high-status journal indexes also favor research journal articles over publications aimed at practitioners (articles, books, and book chapters), and many of these genres are published in scholars’ local or regional languages (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Ch. 1). Another category of excluded publications is ‘outreach’ genres using local languages aimed at general audiences and shared on digital platforms such as websites, academic and other blogs, YouTube, and social media (Reid, Reference Reid2019). The production of these genres is increasing, however, as funding agencies require scholars to evidence the social impact of their/our research (e.g., McGrath, Reference McGrath2014; Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Young, Pedersen, Sørensen, Geschwind, Kekäle and Pinheiro2019).

These variations and omissions in the classification and counting of scholarly texts contribute to the skewing toward publications in high-status journal indexes in any discussions of research production and policies of evaluation. This skewing hampers accountings of the totality of what scholars produce, notably communications in multiple languages and for different audiences (see, e.g., Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, North and Slowtow2021, for the example of research publications on climate change). The hyper focus on English tends to obscure the enduring value of other publications – in all languages – both to academics and to knowledge production in general. A comprehensive accounting of academic knowledge production thus needs to encompass the inherent multilingualism of many scholars’ practices and texts.

3. Scholars’ practices of research and knowledge production: Multilingual realities and imperatives

The products of research – especially journal articles – have been the dominant focus of much research on global knowledge production. By paying attention to the place of language(s) and literacy/ies in the full range of scholars’ research practices, multilingualism becomes more visible, evident in practices from conducting research to communicating within collaborations to sharing findings at conferences and in publications for local, regional, and international research and practice communities as well as the general public (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2004; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Reference Lillis and Curryin press). The rise in transnational research collaborations (Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Rapini, Silva and Albuquerque2018) and the broader ‘internationalization’ of higher education taking place through the migration of scholars and students means that multilingualism now characterizes many research settings (Melo-Pfeifer, Reference Melo-Pfeifer2020), including those previously considered monolingual. These research findings challenge the default assumption that English is the linguistic medium of communication in transnational collaborations, particularly in science and technology fields (e.g., Chawla, Reference Chawla2018).

The place of multilingualism not just in scholarly output but also in many scholars’ core research practices becomes visible through studies of knowledge production that explore not only writing practices and texts but also the research activities and communications that precede the production of these texts. In the PAW study, local and regional languages occupy a central place in most participants’ research activities: Scholars use multiple languages to do research, communicate within collaborations, and share research findings orally at conferences and in writing across a range of genres (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Reference Lillis and Curryin press). Scholars conduct interviews, take field notes, administer surveys, and analyze the resulting data using local or regional languages; scholars who participate, for example, in European Union-sponsored multilateral research projects may translate the data collection instruments that are shared across partner countries to be administered in local or regional languages, and they later analyze locally generated data. Other research has underlined how Spanish earth scientists’ flexible use of linguistic resources was prompted by the different locations of their field work, using Spanish and Portuguese while working in Argentina and Brazil, respectively (Pérez-Llantada, Reference Pérez-Llantada2018). The function of multiple languages as ‘link’ languages in transnational research collaborations is attested by Holmes's (Reference Holmes, Kuteeva, Kaufhold and Hynninen2020) study of so-called bilingual Swedish academia, in which a Malay-speaking Ph.D. student communicated in Chinese with a Chinese Ph.D. student working in the Netherlands while collaborating on research, although their ultimate publication was written in English. The linguistic repertoires of some members of transnational research collaborations inform which languages become the official working languages of the collaboration – and not always English (e.g., Lüdi, Reference Lüdi, Jessner-Schmid and Kramsch2015; Melo-Pfeifer, Reference Melo-Pfeifer2020; Zarate et al., Reference Zarate, Gohard-Radenkovic, Rong, Jessner-Schmid and Kramsch2015). Scholars’ multilingual practices emerge organically by drawing on their/our repertoires to interact with the linguistic and cultural identities of research partners, languages used locally, and languages sanctioned for use in conferences and publications (Salö et al., Reference Salö, Holmes and Hanell2020). These practices complicate understandings of the place of language(s) in the types of communications occurring along a research trajectory that may span study design, grant writing (and participating in grant applications of partners in academic research networks), data collection and analysis, and the dissemination of findings to different communities in multiple languages and genres. In the rest of this section, we explore some of the key imperatives evident in scholars’ multilingual practices in research and writing.

3.1 Expressing multilingual identities

Language is more than a functional medium for communicating about academic work; rather, scholars are informed by their/our identities while exercising agency in choosing languages to use in particular situations. For example, when Canadian scholar Payant took a job in Québec, she explicitly decided to publish in her home language of French with the goal to ‘develop a bilingual professional identity’ (Payant & Belcher, Reference Payant and Belcher2019, p. 16), despite being keenly aware that in the Canadian evaluation regime: ‘It's really not advantageous to be publishing in a language other than English’ (p. 19). While adding to her workload, Payant's commitment to bi/multilingual writing and publishing stemmed from deeper concerns about her professional role and the status of academic French in Canada. Professional identity also informs scholars’ desires for the sense of control over their voice in writing. Not surprisingly, it is often easier for a writer to articulate complex ideas in a local language(s) – that is, the language or languages used on a regular basis in academic and other domains – than in another language (Belcher & Yang, Reference Belcher and Yang2020; Monteiro & Hirano, Reference Monteiro and Hirano2020). Studies indicate scholars' concerns about the loss of voice in writing in English, as signalled by an Icelandic economist who felt that when writing in English, ‘My personal style is lost … my own voice,’ in contrast to her writing in Icelandic (Arnbjörnsdottír & Ingvarsdottír, Reference Arnbjörnsdottír, Ingvarsdottír, Curry and Lillis2018, p. 79).

Researchers’ academic identities often emerge from, and are enacted through, local/regional intellectual and epistemological communities, traditions and academic-social commitments, particularly in the humanities and social sciences (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Alastrué and Pérez-Llantada2014). The scholars that Arnbjörnsdottír and Ingvarsdottír interviewed felt ‘tensions and trepidations’ in using English as ‘a language they see as distant from their ways of thinking’ (p. 74), despite being highly proficient in academic English. One of them, a philosopher, opts for Icelandic in academic publishing, viewing it as ‘more rewarding and more authentic’ than English (p. 82). What emerges from the PAW study is a complex and multidirectional orientation to the relationship between language(s) and the kinds of knowledges scholars develop and produce. This orientation is connected to scholars’ sense of themselves as academics. For example, Katja,Footnote 4 a Hungary-based scholar, sees her academic identity as being bound up with theory building and clinical practice in local (Hungarian) and transnational (e.g., Mexico, Sweden) contexts (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curryin press).

In English-dominant and officially bilingual contexts in North America, some academics also negotiate the use of languages besides English in their scholarly work, even with English as the default language of their institutions. They publish in multiple languages with the purpose of enriching disciplinary conversations. In the United States, scholars across disciplines at a Hispanic-serving university acted from strong commitments to publishing in their ‘home’ languages as well as English (Cavazos, Reference Cavazos2015). Foreign language faculty in another U.S. institution also used their home languages in research and publications, successfully flaunting English Only institutional publishing policy (Fuentes & Gómez Soler, Reference Fuentes and Gómez Soler2018). Beyond using French for reasons of identity and personal commitments, Canadian scholar Payant also feels a ‘moral obligation’ (Payant & Belcher, Reference Payant and Belcher2019, p. 19) to perpetuate the use of academic French in officially bilingual Canada, where English and French have unequal status. Similarly, a participant in Payant and Jutras's (Reference Payant and Jutras2019) study reported a commitment ‘de contribuer au développement d'une langue scientifique en français’ (p. 9) to counteract domain loss in French.

3.2 Sustaining indigenous languages and cultures

In a manifestation of scholars’ social and cultural commitments, in contexts around the world indigenous languages are also being used in academic publishing. Though English Only proponents might see as impractical the project of using indigenous languages in academic communications, given the small numbers of speakers of many indigenous languages, a few recent studies highlight the place of indigenous languages in research studies and dissemination of findings. In northern Scandinavia, scholars at the Sámi University of Applied Sciences who are dedicated to perpetuating ‘Sámi culture, languages, and ways of living, and to strengthen[ing] the development of the Sámi society’ (Thingnes, Reference Thingnes2020, p. 156) write for publication in Northern Sámi. Communicating research findings on indigenous cultures and related topics in local languages also shares such knowledge with the communities that have informed or participated in the research. Koller and Thompson's (Reference Koller and Thompson2021) survey of the extent to which indigenous languages are represented in academic publishing outlets identified, for example, three bi/multilingual journals that publish articles in the Hawaiian language, providing an outlet for scholars to write in Hawaiian and helping to revitalize the language. Short videos have also been produced in the indigenous languages of Guaraní (South America) and Tsonga (Mozambique) to share research findings with members of these communities (Ramos, Reference Ramos2017).

3.3 Benefitting local communities

The commitment to sharing research with communities that can benefit from the knowledge created in local contexts underpins many scholars’ commitments to publish in local, regional, and other languages (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010; Kulczyki et al., Reference Kulczyki, Guns, Pölönen, Engels, Rozkosz, Zuccala, Bruun, Eskola, Starčič, Petr and Sivertsen2020; Schluer, Reference Schluer2014). Martin, a Slovak psychology scholar in the PAW study, noted in an interview his desire to introduce to the local community topics such as the need for sexual education for people with disabilities. While local audiences are clearly likely to be interested in topics related to local languages, linguistics, literature, history, and politics (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2019), there is also a need for research to be published in local languages particularly on issues such as climate change, local environmental ecosystems, and health, so this knowledge can be available in directly affected areas. As Hunter et al. (2021, p. 218) argue, ‘local language research is more likely to incorporate local nuances, challenges, or solutions that may be unique to specific contexts or borne of a unique worldview, than research in a foreign language [i.e., English]’. Local-language publications are being seen as increasingly valuable in providing readers in transnational contexts with detailed scientific research results about specific geolinguistic locales. Here, we reiterate the point that many scholars, including natural scientists, have never abandoned the use of local/regional languages in their publications (e.g., Hanauer & Englander, Reference Hanauer and Englander2011; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Reference Lillis and Curryin press).

Multilingual scholars participating in numerous research studies report that local academic and practice communities may be more likely to read local language publications than English-medium texts (e.g., Bajerski, Reference Bajerski2011; Purnell & Quevedo-Blasco, Reference Purnell and Quevedo-Blasco2013; Shehata & Eldakar, Reference Shehata and Eldakar2018). Academic publications in local/regional languages are often more accessible and more affordable than high-cost English-medium journals (which are also unaffordable for many under-resourced Anglophone-center academic libraries) (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis, Curry, Erling and Sargeant2013). These local journals benefit from the explicit support of authors as well as editors and publishers. Thus, an additional imperative driving scholars’ publishing in local/national languages is to sustain and build local knowledge infrastructures, such as journals produced in local languages, as highlighted by López-Navarro et al. (Reference López-Navarro, Moreno, Burgess, Sachdev and Rey-Rocha2015) with regard to Spanish; Smirnova et al. (Reference Smirnova, Lillis and Hultgren2021) with regard to Russian; and Lillis (Reference Lillis2012) with regard to Spanish, Portuguese, Hungarian, and Slovak.

Publishing in local/regional journals in both local languages and English provides multilingual scholars with opportunities for intellectual work that has sometimes been misrecognized (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu2000) by Anglophone-centre editors and reviewers, as evidenced in the experiences of scholars participating in the PAW study. For example, Portuguese scholars Aurelia and Ines decided to resist the demands of Anglophone reviewers and editors to ‘simplify’ the theoretical aspect of a paper, as they felt local readers were better equipped to grasp it intellectually because of longstanding engagement with the authors’ work that was published in the local language (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Chs. 4, 7). Slovak psychology scholar Géza discusses how there are greater opportunities for transdisciplinary conversations in local (in this case, English-medium) journals (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Chs. 4, 7). Marta, a Spanish psychology scholar, found Spanish journals to be more interested in her research using a case study approach than were English-medium journals (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2004). Similarly, the Russian scholars studied by Smirnova et al. (Reference Smirnova, Lillis and Hultgren2021, p. 9) reported that Russian journals were more open to research on local topics and using qualitative methodologies, in contrast to the quantitative research methodologies favored by English-medium journals included in the top quartile of the indexes recognized by Russian evaluation systems. The Russian scholars also found that the process of publishing in local journals was faster than in high-status Anglophone journals, an important consideration for many scholars in meeting the demands of evaluation policies. In Latin America, Perrotta and Alonso (Reference Perrotta and Alonso2020) highlight, the ‘research agendas within MERCOSUR [contexts] are more likely to share theories, methods and approaches which allow them to circulate more fluently in the regional circuit’ (p. 89). A plethora of substantive reasons to favor publishing in local/national languages and in local journals has thus been identified in the research.

Multilingual scholars also distribute their/our work in local and regional languages to enact commitments to developing local researchers and practitioners. For example, Olivia, a Slovak educational scholar in the PAW study who took part in a multilateral European Union literacy research collaboration, preferred to disseminate the project's findings in Slovak-language publications as she felt the knowledge would benefit local schoolteachers and members of her research team, who would be unlikely to access the publications in English (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2010).

3.4 Responding to institutional evaluation regimes

Despite the highly documented fetishization of the English-medium journals included in high-status indexes, and sometimes only in their top quartiles, many academic evaluation regimes do actually reward publications in local/regional languages. This finding was demonstrated in policy documents collected from the four national contexts of the PAW study that award specific numbers of points for different kinds of publications and scholarly activities such as making transnational conference presentations and participating in transnational research collaborations, including but not limited to English (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010). The continued inclusion of texts written in local/national language in evaluation regimes in part reflects a push back against the idea of an English Only academic space and may enable scholars’ social commitments while also supporting their research opportunities and career progression (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2014). For example, Hungarian scholars in the PAW study, including education scholar Julie, felt the need to publish in Hungarian to be competitive for grant funding in Hungary. In Mexico, according to Olmos-López (Reference Olmos-López2019), Spanish has an important place in the evaluation of academic communications, particularly if:

a lecturer at a university wants to belong to the PRODEP (Programa para el desarrollo del Personal Docente del tipo superior), the national distinction for quality work as a lecturer and researcher [ … as] the official papers have to be written in Spanish’ (p. 33).

In the case of China, after its strong push for English-medium publishing in WoS journals (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Beckett and Huang2013), the pendulum appears be swinging back – at least to some extent – to recognizing Chinese-medium publications. In 2020, the Chinese government issued guidelines calling for one-third of academic articles to be published in domestic journals and for publication metrics to cease serving as the main evaluation criterion for scholars’ academic work (Zhang & Sivertsen, Reference Zhang and Sivertsen2020). Indeed, cultural capital can be associated with publishing multilingually (rather than monolingually in English), as underscored in Anderson's (Reference Anderson, Curry and Lillis2018) study of young, mobile European researchers: Publishing in local languages helped them qualify for hiring opportunities in other European countries.

4. Shifting practices over academic careers

Another commonplace in research on academic publishing is the notion of a generational shift toward the exclusive use of English; that is, the belief that younger scholars are predominantly communicating in English while mid- and late-career scholars persist in publishing only in local language(s) and journals (either because of their assumed low English proficiency levels or their stubborn resistance to the hegemony of English). While individual scholars’ choices of language can and do change at particular moments in their careers, the PAW study as well as the other studies of scholars’ multilingual practices we discussed above challenge the notion of unidirectionality toward English in academic publications. In conducting a recent retrospective analysis of the curriculum vitae (CVs) of the scholars in our PAW study, we found, strikingly, that the majority of scholars have consistently used two and sometimes three or more languages along the length of their careers (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curryin press). The only two scholars who currently publish exclusively in English – Julie, an education scholar, and Tadeus, a psychology researcher – now work in predominantly Anglophone academic contexts, but they both spent earlier phases of their careers working in Hungary and publishing in Hungarian.

Depending on discipline and the requirements of evaluation regimes, some later-career scholars who have been promoted or accomplished other goals feel less pressure to publish in English and thus shift to publishing in local languages and/or in genres other than research articles (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2018). For instance, Esther, a Turkish scholar of foreign languages working in the United States who was interviewed by Fuentes and Gómez Soler (Reference Fuentes and Gómez Soler2018), initially used English tactically (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2014) – ‘Before I became full [professor], I made sure I published in English’ (p. 200) – but now she feels freer to write in Turkish. What becomes clear in examining these dimensions of scholars’ publishing practices is the strong sense of agency that scholars exert along the span of their/our work lives. Even while responding to pressures – both empirical and hegemonic – to publish in English in particular journals or in journals listed in particular indexes, because of various commitments multilingual scholars continue to invest time and effort in using local/national, regional, and other languages.

5. Discussion: Putting English in its place

In focusing on how multilingualism is woven throughout the research settings, practices, and texts of scholars in many locations, we are not ignoring the real and powerful pressures for English created by many evaluation regimes, nor the cultural capital that English-medium publications often provide for scholars, as we and others have documented (Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2002; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Reference Lillis and Curry2018). Many scholars see publishing in English as a pathway to greater visibility for their work to reach wider audiences and to having their English-medium publications cited, particularly if their local language is not a major world language (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2004), their field is highly specialized (Lillis, Reference Lillis2012), and/or the local language is densely populated with Anglophone terms (Rhekhalilit & Lerdpaisalwong, Reference Rhekhalilit and Lerdpaisalwong2019). But acknowledging the privileged position of English does not mean – as has often come to be the case – that global academic knowledge production is or should be an English Only space. By relegating discussion of the role of English to the end of this paper, we aim to turn the predominant focus on English, and the English Only ideology, on its head. Instead, we have aimed to emphasize the multilingual realities of academic knowledge production globally. We want to underline the importance of legitimizing multilingual practices and enhanced possibilities for increasing multilingual practices in knowledge exchange that can be facilitated by: (a) sanctioning and supporting the publishing of multiple versions of the same text for different audiences in various languages; (b) adopting a networked approach to knowledge exchange where scholars share resources, including expertise in different languages, to facilitate the production and uptake of academic texts; (c) increasing the use of open-access online translation tools; and (d) expanding pedagogies to include translingual approaches.

Though ‘parallel language use’ (McGrath, Reference McGrath2014) has in some contexts been an established approach to distributing research to markedly different audiences – research, practice, public – the historic taboo against scholars publishing a research text in multiple publishing outlets, often seen as self-plagiarism, results from monolingual assumptions that scholars produce academic knowledge only for one audience, with which they share one language and academic culture. These assumptions are outdated in their understanding of how and where scholars can and should distribute knowledge. We have previously advocated for this taboo to be abandoned in recognition of the contemporary realities of the global academic landscape – the affordances of electronic communication and the negative consequences of increased English-medium publishing that remove research from contexts of potential use (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2019; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010; see also Wen & Gao, Reference Wen and Gao2007). Instead, we argue that, as many research funders already have, institutional policymakers and journal gatekeepers should acknowledge the benefits of distributing knowledge globally in multiple forms and languages by rewarding such efforts. The PAW study demonstrates the strategic ways that multilingual scholars work to direct different versions of texts to specific audiences by reframing texts and selectively including different kinds of information (Curry & Lillis, Reference Curry and Lillis2014; Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010). For example, in writing related articles for British and Portuguese research journals, education scholars Ines and Aurelia changed their citations as well as the type and amount of contextual background they provided to each audience. Furthermore, as Durand (Reference Durand2006) emphasizes, there can be value in publishing research in a local language before distributing it in English to protect scholars from having their ideas claimed by others.

The current reality of electronic communications also crucially enables a networked approach to publishing multilingually that enables scholars around the world to collaborate and share resources across global contexts (including language expertise, research data, electronic copies of publications, and other useful information such as conference and publishing opportunities) (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010, Ch. 3). The development of (better quality) online translation tools such as DeepL is enabling such tools to be used more frequently (see Gentil, Reference Gentil2019), offering alternatives to resourcing issues faced by multilingual scholars, as emphasized by scholars in the PAW study (e.g., costs of translation, necessary time, and quality of translation) (Bowker & Buitrago Ciro, Reference Bowker and Buitrago Ciro2019). These tools also create opportunities for monolingual scholars to engage in multilingual knowledge-production practices, an important development that we believe should be supported (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curryin press).

Pedagogies of academic literacy and writing for publication should not start from the position of English as the only (viable/legitimate) language for research communications, as is the default in many educational contexts and in research on English academic literacy practices and pedagogies. Rather, academic language pedagogues should work from a premise of academic multilingualism and consider not only the texts being produced but also the trajectory of texts from their origins in research and scholarly activity. A translingual approach to teaching English for Academic Purposes (EAP) is one way to create ‘a social space where [learners] can draw on their linguistic resources and experiences of writing practices’ (Kaufhold, Reference Kaufhold2018, p. 1) that may sustain academic registers and academic literacy in multiple languages (Payant & Belcher, Reference Payant and Belcher2019). While most discussions of translingualism have focused on student writing (e.g., Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2013; Sun & Lan, Reference Sun and Lan2021), academic publications themselves increasingly also feature translingualism (e.g., Gentil, Reference Gentil2019; Lillis, Reference Lillis and Avila-Reyes2021; Musanti & Cavazos, Reference Musanti and Cavazos2018); this phenomenon should inform publishing pedagogies.

6. Concluding remarks

In this paper, we have argued for putting English in its place by taking greater account of the place of multilingualism in academic knowledge production. This position aligns with recent movements such as the Helsinki Initiative on Multilingualism in Scholarly Communication (www.helsink-iniative.org) and the Manifesto in Defense of Scientific Multilingualism (Remesal Rodríguez, Reference Remesal Rodríguez2016). By exploring how multilingualism is woven into the practices of conducting and communicating about research and scholarship, we have advocated for researchers and practitioners to resist the increasingly circulated ideology of English Only in global academic knowledge production and communications. In fact, as this paper documents, many scholars are already publishing in multiple languages. We also urge policymakers designing and implementing research evaluation regimes at institutional, national and international levels to explicitly recognize the value of publishing multilingually – including the additional time, resources, and effort it requires – and to provide support for this work. While some evaluation regimes reward publications in local/regional languages, in policies gathered as data for the PAW study these rewards are often lower than for English-medium publications, presentations, and transnational collaborations (Lillis & Curry, Reference Lillis and Curry2010).

Journal publication requirements that exclude languages other than English could also be expanded creatively; for example, by allowing, as Dołowy-Rybińska (Reference Dołowy-Rybińska2021) promotes, scholars to submit journal articles in their preferred language and not worry until acceptance about preparing a translation into English. Additionally, the affordances of the Internet enable all journal publishers to create space for multiple language versions of articles to be made available to various audiences. In sum, we argue for better policies and practices that will recognize the multilingual nature of contemporary academia to enable all scholars’ greater participation in multilingual knowledge exchange and thus help sustain ‘epistemological diversity’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Alastrué and Pérez-Llantada2014, p. 30) across cultures.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to University of Rochester education librarian Eileen Daly-Boas for help with bibliometric research and to Ph.D. students Adel Alshehri and Xiatinghan Xu, who served as research assistants.

Mary Jane Curry is Associate Professor in the Department of Teaching and Curriculum at the Warner Graduate School of Education, University of Rochester, USA. She has published seven books including, with Theresa Lillis, Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English (2010); Global academic publishing: Policies, perspectives and pedagogies (2018); and A Scholar's guide to getting published in English: Critical choices and practical strategies (2013), as well as Language, literacy and learning in STEM: Research methods and perspectives from applied linguistics (2014); Educating Refugee-background students (2018), and An A-W of academic literacy: Key concepts and practices for graduate students (2021). Curry is co-editor of the Multilingual Matters book series, Studies in Knowledge Production and Participation. She has been a Fulbright scholar in Chile, co-associate editor for TESOL Quarterly's Brief Research Reports, and principal investigator of a US Department of Education grant on English language teaching.

Theresa Lillis is Professor Emeritus of English Language and Applied Linguistics at The Open University, UK. She has been researching academic and professional writing for over 30 years, focusing on the politics of production and participation. Key publications include Student writing: Access, regulation, desire (2001); Academic writing in a global context (2010, with Mary Jane Curry); The sociolinguistics of writing (2013); Academic publishing in English (2013, Special issue, Language Policy, with Mary Jane Curry); Theory in Applied Linguistics (2015, Special issue, AILA Review); Gender and academic writing (2018, Special issue, Journal of English for academic purposes, with Jenny McMullan and Jackie Tuck). She has published on academic literacies in Language and Education, Cahiers Théodile, Signo y Pensamiento, Enunciación and Arts and Humanities in Higher Education and on social work writing in Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, Journal of Corpora and Discourse Studies and Written Communication.