To many Americans in the late nineteenth century, international arbitration seemed a topic reserved for men. The idea—that of settling a dispute among nations by submitting the case to a neutral judge whose decision the parties agreed in advance to accept—had been gaining traction among peace advocates, lawyers, and policymakers over the previous decades. Republican Senator Charles Sumner saw it as the most just and practical method for resolving conflicts, “so that war may cease to be regarded as a proper form of trial between nations.” Philip C. Garrett of the National Arbitration League, formed in 1882 to harness public support for the cause, justified the league’s creation by arguing that all American men should join the movement: “I think the time is ripe for the participation [of] … all prominent men who have humanity at heart.” In 1885, the league argued in its annual report, “The people must be taught that the people of all countries have a common brotherhood … [and] the United States finds its best armies in the silken robes of peace.”Footnote 1 Like many Americans at the time, Garrett and others used masculine language when speaking ostensibly in universal terms, but the ideal world they envisioned was very much still dominated by men. It likely never occurred to Sumner or Garrett to enlist women in the cause.

They would have found eager—and prominent—recruits. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, at the first major international conference of women in 1888, argued that greater cooperation among women would “help forward the day when all international difficulties would be settled by arbitration.” Other well-known women such as Frances Willard, May Wright Sewall, and Belva Lockwood regularly spoke on the subject. The largest national women’s organizations of the time, including the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and the National Council of Women (NCW), established committees dedicated to studying and promoting arbitration. The International Council of Women (ICW), which by the mid-1890s represented thousands of women around the world, broke its own rule against taking stands on political issues in order to join the movement. And in May 1899, more than 175,000 women across the United States demonstrated in support of demands for the governments of the world, then gathered for a peace conference at The Hague, to establish a permanent international court of arbitration.Footnote 2

These women had been paying attention as arbitration increased in use and popularity over the nineteenth century. The idea was not new; the Greeks, the Romans, and even the Catholic Church had used arbitration to resolve disputes with other peoples and territories. Beginning in the seventeenth century, it was used most often among nation states, often to resolve tensions over territorial boundaries, monetary claims, or colonial questions. Typically, representatives of the nations involved would request a neutral individual or a panel of arbitrators to weigh the evidence on both sides and come to a resolution. (This is not to say, of course, that arbitral decisions were always observed or enforced.) In the late eighteenth century, states began to use treaties as a way to signal good faith by agreeing in advance to arbitrate certain disputes. The United States and Great Britain first agreed in 1794 to use arbitration in select diplomatic instances, but they did not make much use of the practice until the mid-nineteenth century, when they increasingly used it not only with each other but with other nations as well. The United States resolved minor issues with several Latin American countries in the 1850s and 1860s through arbitration. In 1872, an Arbitrator awarded the United States $15 million in damages arising from attacks by British-built Confederate raiders against Union merchant ships during the Civil War. In the 1880s, both major U.S. political parties included support for international arbitration in their platforms. And by the 1890s, the principle had gained endorsements from a range of international jurists, diplomats, and statesmen.Footnote 3 Most governments, it is important to note, including the United States, refused to endorse agreements that would bind them to the process under most circumstances. A majority of men in Congress and the executive branch saw both arbitration, and anything resembling international law, as an attack on U.S. sovereignty.Footnote 4

Like Garrett and his contemporaries, most historians who have traced these developments have also treated international arbitration as the province of men. Among those writing before the advent of women’s history in the 1960s and 1970s and relying solely on government documents, this is not surprising. Two of the first scholars to survey the subject made little mention of any nongovernmental efforts toward its promotion and none at all of women.Footnote 5 Historians working amid the rise of social history and women’s history devoted more attention both to popular support for arbitration and to women’s peace efforts, but rarely connected the two.Footnote 6 In other words, their work gives the impression that only men spoke about arbitration while women did not know it existed. This tendency to overlook women’s interest in international arbitration has continued into more recent studies. Those who discuss arbitration in the context of international law, international organization, and nongovernmental peace efforts, for example, still rarely mention women.Footnote 7

This is disappointing but also not surprising, particularly given the sources these scholars often use. Examining the ways in which arbitration gained acceptance among statesmen is a worthwhile endeavor, but official state records and the personal papers of diplomats and officials are unlikely to betray any hint of women’s activism. Approaching the issue from the perspective of international lawyers leads to the same result; the American Society for International Law, for instance, founded in 1906 to promote law and justice in relations among nations, forbade women members.Footnote 8 And the records and publications of nongovernmental groups, such as the American Peace Society, the Universal Peace Union, and the National Arbitration League, reflect the fact that women rarely occupied leadership roles in those organizations. This lack of women in the sources leads to the assumption, whether implicit or explicit, that they played no part in the movement for international arbitration.

Sources centered on women, however, tell a different story. International arbitration was in fact the first foreign policy issue that galvanized women on a large scale. Evidence of women’s international consciousness dates back at least to transatlantic discussions of women’s rights at the turn of the nineteenth century and continues through the long years of the anti-slavery and early women’s rights movements.Footnote 9 And individual women like Lydia Maria Child, Jane McManus Storm Cazneau, and Victoria Woodhull certainly spoke out on U.S. foreign policy.Footnote 10 But it was not until the rise of mass organizations like the WCTU, the ICW, and NAWSA that women began to use their platforms to weigh in on foreign policy debates. Historians of women’s peace activism have recognized this; they often date the origins of women’s interest in foreign policy to the anti-imperialist movement of the late 1890s.Footnote 11 But reaching back a decade further reveals that arbitration set the stage for these later mobilizations by creating the organizational mechanisms and the language women used at the turn of the century and beyond.

Arbitration sparked women’s interest in foreign policy because it resonated in the context of their other reform campaigns, especially temperance and suffrage, and they integrated their demands for the peaceful settlement of disputes into their calls for prohibition and political equality. Their advocacy was an acknowledgment of the fact that war touched every aspect of society and made work for any other causes doubly difficult. “Nothing increases intemperance like war,” WCTU founder Frances Willard argued, “and nothing tends toward war like intemperance… . Nothing would today set back the temperance cause like the outbreak of war.”Footnote 12 Moreover, women believed there was a reciprocal relationship among these reforms. Temperance and equal suffrage would help bring about peace between nations. Sober men would see the need for arbitration treaties, and women voters would pressure policymakers to implement them. Women’s calls for international arbitration were thus a key component of their arguments for inclusion in the public and political life of the nation.

Arbitration and Maternalism

Despite the fact that most prominent men seem never to have considered the notion that women might be interested in international arbitration, many women saw it as a natural outgrowth of the maternalist and domestic ideologies that shaped many of their reform efforts in the late nineteenth century. Just as women’s childrearing and caregiving duties within the home authorized them to advocate for the health and well-being of their communities, it also equipped them to settle fights and squabbles—even among nation states. Willard, for instance, believed women were endowed with the “finest qualities of diplomacy.” For centuries they had been the “chief member of a board of conciliation in the home, hearing complaints, adjusting differences, forming treaties of peace, administering justice, and anointing the machinery with patience and goodwill.”Footnote 13 Women’s roles as mothers not only made them more able to appreciate the sanctity of life, it also gave them practical skills that Willard saw as readily transferable to international relations in general and to arbitration in particular. This attitude infused the majority of women’s arguments for arbitration in the late nineteenth century.

Broad support for arbitration among women first surfaced at the International Council of Women in 1888, the gathering that launched the great wave of transnational activism that persisted until the 1930s. Co-organizer Elizabeth Cady Stanton argued not only that greater participation of women in political life would further the cause of international arbitration, but that women’s international activism itself would further peace among nations. The “great moral struggles” for education, temperance, religious freedom, peace, arbitration, and other causes would be accomplished in the end only through the efforts of governments, she contended, and “without a direct voice in legislation, woman’s influence will eventually be lost.” In the meantime, however, “closer bonds of friendship between the women of different nations may help to strengthen the idea of international arbitration in the settlement of all differences, that thus the whole military system, now draining the very lifeblood and wealth of the people in the Old World, may be completely overturned, and war, with its crimes and miseries, ended forever.”Footnote 14 Women’s suffrage was necessary for international arbitration to succeed, Stanton believed, while the work of organizing for suffrage and other causes would in turn bolster arbitration campaigns.

Other speakers, including Willard, connected arbitration to maternalism and domesticity more explicitly. Clara Neymann, a German immigrant and suffragist, argued that the advent of arbitration made it more necessary than ever for women to reject persistent images of themselves as frail and frivolous and embrace their responsibilities: “Since questions of peace, of arbitration, of reconciliation have superseded those of war and conquest, it is folly, sheer sentimentality to still hold up the medieval ideal of womanhood. … The coming woman must be strong and sweet. She must come from her well-ordered home and bring grace and dignity and purity into our public and political life.”Footnote 15 Willard reflected that if only Eve had not been cast out of Eden, if men and women had remained hand in hand, the world would have become as Christ intended. Men acting alone, without women’s influence or participation, always produced harm, she argued. The persistence of war was the most obvious example. But women’s entry into public life would bring about “the reign of peace.” “The mother heart that cannot be legislated in and cannot be legislated out would say: ‘I will not give my sons to be butchered in great battles,’ and we would have arbitration.”Footnote 16 Neymann and Willard made it seem perfectly natural that domesticity, maternalism, and arbitration were all connected, and that women had both a right and a duty to involve themselves in campaigns for international arbitration.

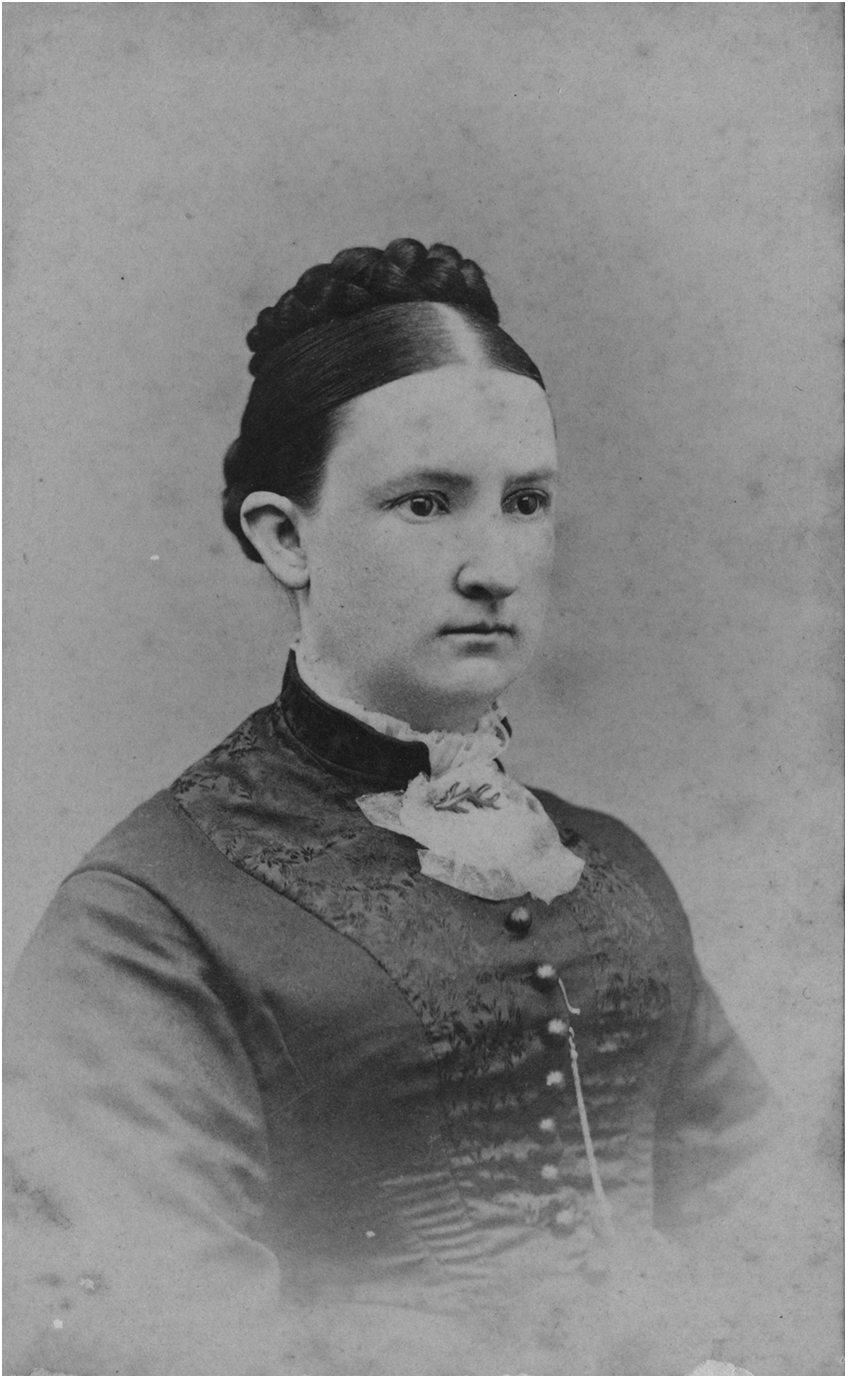

The WCTU was the first mass organization of women to include arbitration in its platform. The U.S. national group created a Department of Peace and Arbitration in 1887; the World’s WCTU followed suit two years later. Both were chaired by Hannah Johnston Bailey. Born in 1839 into a Quaker family in upstate New York, she married Moses Bailey in 1868, and moved with him to Maine, where he had a prosperous oilcloth business. Upon her husband’s death in 1882, Bailey found herself one of the wealthiest women in Maine, able to devote the remaining forty years of her life to various reform causes. She worked for many years to establish a state reformatory for women, she served as president of the Maine Woman Suffrage Association, and in 1883, she joined the WCTU. Bailey’s commitment to peace was rooted in her Quaker faith. War was a sin, she asserted, and only by following Jesus’s example of compassion and humility would human beings be able to abolish war. As the director of the WCTU’s peace campaigns, Bailey wrote and distributed literature, organized public meetings, and spoke in a variety of venues on behalf of arbitration. She also dramatically expanded the reach of the World’s WCTU’s efforts; by 1897, her annual report included updates from the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Uruguay, Egypt, Iceland, Palestine, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Italy, and Spain.Footnote 17

Figure 1. Hannah J. Bailey, 1884. Hannah J. Bailey Papers, SCPC-DG-005, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Unsurprisingly, given not only her affiliation with the WCTU but also the historical context of mainstream women’s reform efforts in the late nineteenth century, Bailey’s rhetoric in support of peace and arbitration was highly gendered. She recognized that not all women were pacifists; the pages of history were full of women who had sent armies out to conquer or inspired violence through love or revenge. But she believed women’s experiences as mothers best suited them to advocate for and to maintain peace. The power they exercised in their homes and communities could, if directed properly, give rise to a generation of children opposed to war. In homes, in schools, and in churches, children—boys, in particular—should be taught to abhor violence and militarism.Footnote 18 To that end, Bailey and her committee sought to eliminate all toys, songs, games, and activities that fostered the martial spirit in boys and young men, including military drills in public schools and colleges. “I think it would be well to concentrate our efforts to remove these obstacles until they are removed,” she told the WCTU in 1893, “and then ask for courts of arbitration to be instituted for the peaceable settlement of all disputes, and they will soon be granted, and when obtained, they will be permanently sustained by these children who are to be the men and women of the near future.”Footnote 19 Eliminating militarism in children was thus not only a precursor to advocating for arbitration; it was necessary to ensure the method’s long-term success.

As she grew more experienced, Bailey began broadening her audiences. She looked beyond the WCTU and other women’s organizations and sought to convince more men that women had an important role to play. Befitting her status as one of the most active women supporters of arbitration, Bailey spoke in 1895 at the first Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration. Convened by Quaker brothers Alfred and Albert Smiley, the conference brought pacifists, lawyers, educators, and other public figures from around the country to upstate New York every spring for more than twenty years. Though women attended in significant numbers and took more active roles at the conference after 1900, for the first several years men dominated the program. Bailey was one of the few exceptions. Both in 1895 and two years later at the third conference, she acquainted the attendees with the work of the arbitration committees of the National and World’s WCTU, emphasizing the widespread commitment among women to the cause.Footnote 20

Her goal was to convince her audience of women’s vested interest in arbitration, to claim space for them in the campaign and explain why women had as much right and as much desire to participate in securing arbitration as any man. Her own perspective was innately gendered, but she also understood that arguments grounded in maternalism and domesticity would play well with her audience of genteel male reformers. She recounted the work her committee had done to remove martial toys and activities from homes and schools, and she reiterated the WCTU’s arguments about women’s desire to save their sons from war. “The subject of peace is one of vital importance to woman,” she told the attendees. Moreover, “woman, who suffers so through warfare, certainly desires arbitration. With the banishment of militarism we shall banish myriad evils.” Echoing Willard, Bailey also made the case that motherhood made a woman something of an expert on arbitration: “As part of the duty of a mother is to make peace in her family when contentions exist, or, better still, to prevent them by timely care, it is fitting that the WCTU have a department of Peace and Arbitration.” By all accounts her speeches at the Lake Mohonk Conference over its first few years were well-received.Footnote 21

The WCTU’s commitment to both temperance and international arbitration was the result of its “Do Everything” approach. In recognition of the fact that all reforms were interconnected, members were encouraged to pursue any and all causes aimed at ameliorating social problems. Bailey subscribed to this approach as well, and over the course of the 1890s the issue of suffrage appeared more frequently in her speeches and writings on arbitration. “Many women do not realize it,” Bailey argued as early as 1893, “but, being disfranchised they can only raise their voices against this evil in their own homes. Worn out with the care of her family and of her husband’s work which she must carry on while he is engaged in active service, she can only patiently bear the heavy burdens of militarism.” Nothing would further the cause of arbitration more than the ballot, Bailey felt. Women voters would oppose militaristic measures and help redistribute national resources to efforts that would benefit society.Footnote 22

Maternalist and domestic ideologies suffused women’s advocacy for international arbitration throughout the 1890s. Proponents like Willard and Bailey held that women were naturally suited to promote the cause because it fit with their family roles as peacemakers. This approach, endorsed by the 150,000 members of the WCTU, resonated with the gendered worldview of many Americans. It provided a way for women to assert a greater public role without upsetting the fundamental order of society. As such, it was also employed by many suffragists, though not, in general, to the same extent.

Arbitration and Women’s Suffrage

Women also tied their advocacy for international arbitration to their demands for political reforms, especially suffrage. Like members of the WCTU, other women rarely compartmentalized their work for various causes. They integrated their campaigns for temperance and suffrage, for education and an end to child labor, and for public health and an end to prostitution. The same was true of suffrage and international arbitration, as evidenced especially by the work of the International and National Councils of Women under the leadership of May Wright Sewall.

Many suffragists and other women reformers had long supported arbitration as a method for settling labor disputes. Bailey, who successfully managed her husband’s oilcloth business after his death, deplored conflicts between labor and management and believed arbitration could be a way to settle conflicts between employers and employees and even to forestall a class war.Footnote 23 Clara Bewick Colby, a British American suffragist and newspaper editor, explicitly connected the industrial and diplomatic uses of arbitration. At a meeting of the Association for the Promotion of Arbitration, a short-lived group organized by prominent lawyer Belva Lockwood, Colby added to a list of resolutions in favor of international arbitration the necessity of using the method also “for the purposes of settling differences between employers and employed, and thus averting violence and bloodshed.” Those present approved the amendment.Footnote 24

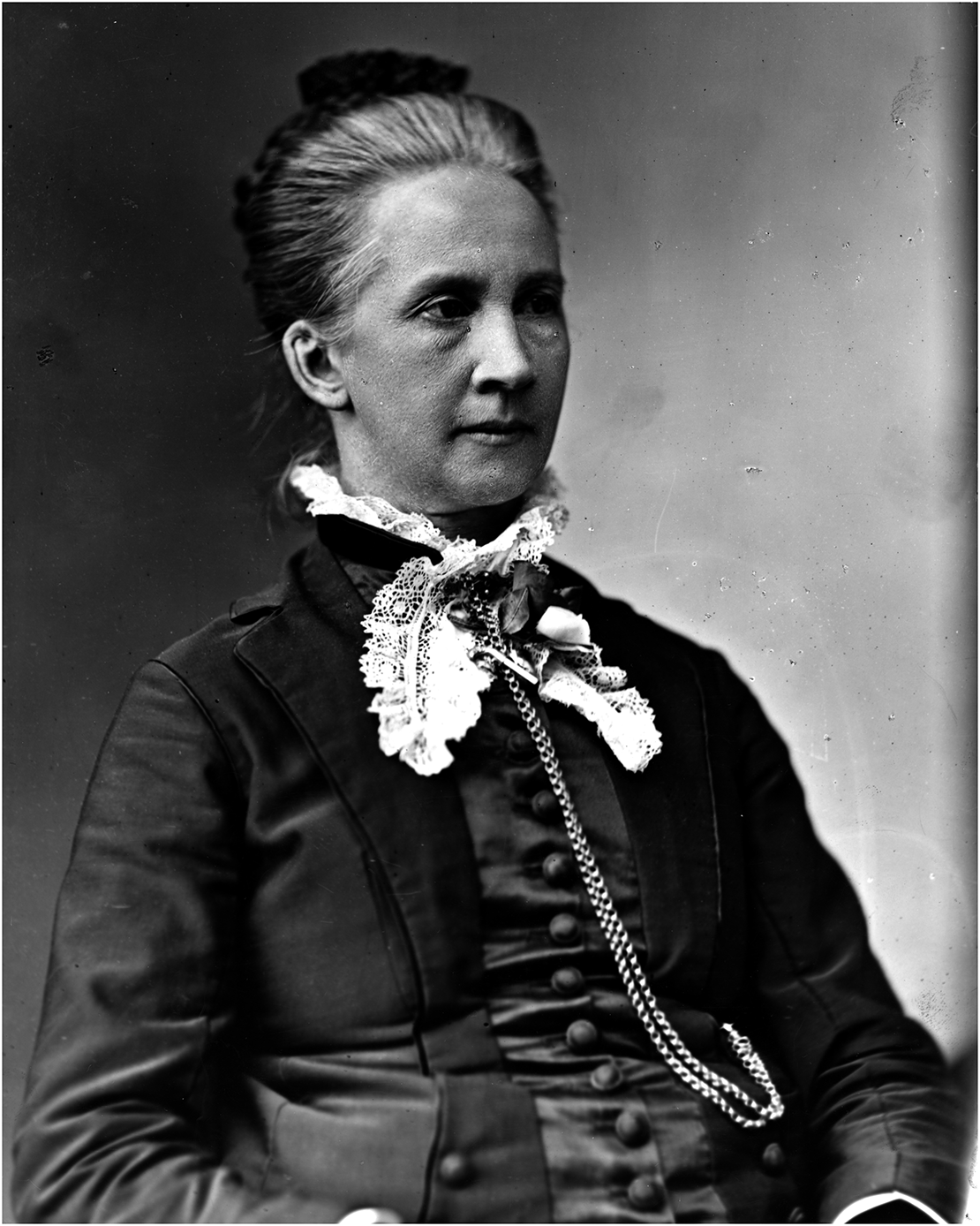

Meanwhile, in the wake of the 1888 conference, arbitration was one of the first principles adopted by both the ICW and the NCW during the 1890s. The nature of both organizations as broad umbrella groups made them reluctant to embrace specific policy agendas. They avoided taking political stances on issues such as suffrage in the interest of bringing together as many women as possible. International arbitration was the first cause for which they broke that rule.Footnote 25 Sewall steered much of both councils’ formative work on arbitration. Born in 1844, she was a longtime teacher and school administrator from Indianapolis who served as president of the NCW from 1897 to 1899 and of the ICW from 1899 to 1904. Though she respected the councils’ nonpolitical stance, she was an ardent suffragist. She helped organize the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society in 1878 and later chaired the executive committee of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.Footnote 26

Figure 2. May Wright Sewall, 1904. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Sewall’s ideology was gendered but not especially maternalist. She believed women had particular points of view on issues ranging from education to labor to politics to diplomacy and that they needed their own venues in which to express and debate those viewpoints. She envisioned the ICW, for example, as the germ of an “international parliament of women,” at which “all the great questions that concern humanity shall be discussed from the woman’s point of view.”Footnote 27 She also believed women should take part in the machinery of arbitration among governments. In 1895, the NCW, under Sewall’s leadership, passed a resolution calling on the U.S. government to establish a “permanent National Board of Peace and Arbitration” and a “Peace Commission composed of men and women” that would “confer with the governments of other nations upon the subject of establishing an International Court of Arbitration.”Footnote 28 Throughout her life Sewall remained determined to secure a political voice for women, primarily through the ballot box but also through direct participation in the broader political affairs of the nation. Lasting peace, she believed, was among the most pressing of those affairs.

Sewall believed greater international cooperation among women could lead to better relations among their governments. She played a prominent role at the large worldwide gathering of women that took place five years after the International Council. The World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 brought more than twenty-seven million people from forty-six nations to Chicago for a six-month celebration of culture, technological innovation, advances in manufacturing, and other human achievements. Women’s organized participation took two principal forms. Sewall convened the World’s Congress of Representative Women, one of a series of congresses held at the Art Institute in conjunction with the exposition. Over 150,000 attendees gathered to listen to lectures on and discuss education, literature, science, religion, labor, moral reform, and the civil and political status of women. Arbitration as such was not on the agenda, but many speakers invoked the theme of peace. Amanda Deyo, a prominent minister and leader in the Universal Peace Union, spoke on “women’s war for peace.” She called on women “from all nations of the world” to raise their voices and say together: “God has given to man the power of reason, and judgment, and understanding, and we demand the settlement of the disputes of the world by arbitration.”Footnote 29

The second and even larger assembly of women took place in the daily congresses held in the Woman’s Building on the fairgrounds. Steered by the Board of Lady Managers, the official planning committee for women’s participation in the exposition, the congresses featured speakers from all corners of the world on every imaginable topic. Eleanor Lord, a history professor at Smith College, spoke on international arbitration. Among other things, Lord’s address is notable for its lack of gendered arguments or any mention of women. Her goal was to educate her listeners on the issue. She surveyed historical efforts toward peace and outlined a handful of occasions during the nineteenth century on which international arbitration had been used successfully. The biggest roadblock to its wider use, she argued, was a disagreement among adherents as to the best method of implementing it—whether a temporary commission or a permanent court was preferable, and how arbitration decisions should be enforced. Lord favored a permanent court, which in her mind would not preclude the possibility of temporary commissions being appointed as needed. As for enforcement, she argued that “any government which refused to abide by decisions of so august a body would suffer eternal disgrace in the eyes of the world, to say nothing of the material loss of commercial good-will.” She ended with a call for Americans to lead the way forward. “Whatever is done,” she declared, “the world looks to America for leadership.”Footnote 30

In the wake of the Columbian Exposition, Sewall kept arbitration at the forefront of the agenda of the National Council of Women. Two years after the council approved her resolution calling for a permanent national board, they established a standing committee on the subject.Footnote 31 As tensions between the United States and Spain grew, many council members lamented the fact that U.S. President William McKinley did not submit any aspect of the disputes to arbitration. After the war began, Sewall sent a message to McKinley on behalf of the NCW, urging him to end hostilities and seek a peaceful resolution. “United in their advocacy of the doctrines of Social Peace and International Arbitration,” she wrote, the more than one million affiliated members of the council implored McKinley to seize the opportunity to become “not merely the defender of the rights and honor of your own country, but the protector and the defender as well of the sublime principle of peace for the world.”Footnote 32 Other peace organizations echoed these calls, though their voices were drowned out amid the clamor for war that swept the nation in 1898.

Other women and organizations continued their advocacy as well. Throughout the 1890s Bailey connected the WCTU’s work for arbitration to its support for women’s suffrage, trying to persuade her colleagues that the former would never be achieved without the latter. Voting women would send representatives to Washington who supported arbitration, and they would pressure the government to reduce military spending and naval armaments. “The cause of justice is well represented by the course of equal suffrage and of arbitration,” Bailey wrote; “and where the two go hand in hand great results will follow.”Footnote 33 Myriad suffragists agreed. Ida A. Harper, chair of the California State Suffrage Press Committee, noted the increasing appeal of arbitration as a method of international dispute resolution, but without women, without “an element in the Government which is anxious not to fight,” that method would never take hold. “As a nation,” she argued, “we shall never reach to our highest and best estate until we have the combined influences of both men and women expressed at the ballot-box, and, through that medium, crystallized into the power that governs.”Footnote 34 And at its conventions in 1896, 1897, and 1899, the National American Woman Suffrage Association passed resolutions in support of an International Court of Arbitration.Footnote 35

Suffragists also protested the lack of recognition for women at the National Conference on International Arbitration, held in Washington, D.C., in 1896. Organized by a group of prominent lawyers and reformers, the conference featured only male speakers. The Woman’s Tribune, edited and published by Clara Bewick Colby, cited the need for suffrage in order to make women’s voices heard on international affairs: “The incident should serve to show women of how little weight they are in movements which are to shape National policy as long as they are disfranchised. If women had been a recognized factor in government, the President of Wellesley College would have been invited as urgently as the President of Harvard.”Footnote 36 Women activists felt they had a responsibility to work for peace, and they called on their government to let them exercise it.

Even some prominent men agreed. Henry Blackwell, editor of the Woman’s Journal, the organ of NAWSA, agreed with Bailey that women’s experiences as mothers naturally rendered them pacifistic. “They have periled their lives in giving [men] birth,” he wrote in the wake of the 1896 conference, “and have spent years of toil in rearing them to manhood. Therefore they are more keenly aware of the cost and value of human life. Women, therefore, when enfranchised, will, as a rule, vote against war and in favor of arbitration.”Footnote 37 George A. Marden, State Treasurer of Massachusetts, addressing a gathering of Republicans who supported women’s suffrage, noted that men were slowly learning more peaceful methods to govern the world but needed women’s presence to support them. “We are learning to govern by arbitration,” he argued, “by leaning toward the things that make for peace, and in that attitude woman ought to be, as she might be, the prevailing influence in our government.”Footnote 38

For all proponents, the 1890s culminated in the convening of the First Hague Conference on International Arbitration (discussed at greater length below). At the second meeting of the ICW in London, held just a month after the conference, Sewall steered passage of a resolution to make permanent various agreements on and mechanisms for arbitration. She used the prestige and extensive reach of both the ICW and the NCW to publicize the Hague Conference and mobilize women to support the cause. She recounted to her colleagues in London how the NCW had won the endorsements of over 175,000 women, even in the face of public derision of the Hague Conference. And at the close of the ICW gathering, she spearheaded a successful drive to pass a resolution in support of the Hague resolutions.Footnote 39

The cause of arbitration, and of peace in general, permeated women’s arguments for suffrage and political equality as much as it did their campaigns for temperance. For U.S. women, the connection between arbitration and suffrage seemed natural. Once equipped with the ballot, they would endorse the method, and their international cooperation would in turn nurture an environment in which arbitration could be successful. Until then, they would continue to exert pressure on the U.S. government to use arbitration to resolve its conflicts. Over the course of the 1890s, tens of thousands of women members of organizations like the NCW and NAWSA threw their weight behind the movement and demanded the founding of a permanent court. U.S. foreign policy thus became a crucial domain in which women future voters could contribute to a better, safer world.

Arbitration and Civilization

The third component of women’s advocacy for international arbitration was more subtle. Like many of their contemporaries, women peace advocates in the 1890s adhered to whiggish, racialized notions of “progress” and “civilization” in which the renunciation of war was a key standard of measurement. According to this mindset, human societies progressed in a gradual, linear fashion from early stages of ignorance to more “enlightened” stages marked by industry, capitalism, and liberal democracy. A willingness to settle disputes through negotiation and compromise was one way of demarcating civilized societies, like the United States and Britain, from uncivilized ones.Footnote 40 In the years before World War I, many Progressives believed that the United States represented the pinnacle of modern society against which all other nations and peoples should be judged. Adopting international arbitration would cement that status. Whether women advocates tied their arguments to maternalism, suffrage, or both, they promoted arbitration as the highest marker of civilization. This attitude later suffused women’s comments on U.S. intervention in Cuba and the Philippines in 1898, but it had been taking shape for several years within discussions on arbitration.

One notable example of the civilizationist viewpoint was Belva Lockwood, probably the most prominent woman promoter of international arbitration in the late nineteenth century. Born in 1830, Lockwood had been a feminist and committed suffragist her entire adult life. After earning her law degree in 1873, she became the first woman to argue a case before the United States Supreme Court in 1879. In 1884, she ran for president as the nominee of the National Equal Rights Party, whose platform included equal rights for all, equal marriage and divorce laws, temperance, and international peace. She received only a few thousand votes, but the effort, along with her legal career, made her a minor celebrity on the political lecture circuit throughout the 1890s. In that decade she turned her attention primarily to peace activism. She was a longtime member of the Universal Peace Union, serving as its delegate to the first Universal Peace Congress in Paris in 1889. She later joined the Peace and Arbitration Committees of both the NCW and the ICW, through which she met May Wright Sewall.Footnote 41

Figure 3. Belva Lockwood, between 1880 and 1890. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Lockwood was an enthusiastic adherent to the peace cause. “War has always been and will always be legalized murder,” she argued, “and the twentieth century should usher in a humane method of settling difficulties.”Footnote 42 In her speeches and articles she frequently contrasted the casualties of armed conflicts such as the Civil War with a long list of disputes that had been settled by arbitration since 1865. She wanted to see not only more arbitration agreements among nations but also a permanent court of arbitration that would serve as a resource for all governments that wanted to use it. The method would not only save lives, she often pointed out; it would also preserve national honor, protect the moral standards of society—which she believed declined among soldiers in wartime—and save money.

The most noteworthy characteristic of Lockwood’s arguments for arbitration was her reliance on Progressive theories of civilization. “We have in the last century,” she told the Universal Peace Union in 1890, “grown out of the savage and heathen idea that we have a right to conquer a nation and appropriate her goods and territory—dismember her for our aggrandizement. We relegate it back to the dark ages of the world.” She highlighted several efforts in Europe toward disarmament and away from militarism. And, with an optimism that seems almost naïve in retrospect, she characterized the U.S. naval buildup advocated by Alfred Thayer Mahan as a matter of national pride rather than a need for defense and predicted the ships would rot in their berths. “They are being built under the old mistaken idea that should now be exploded by civilized nations … that a nation’s grandeur depends upon her ability to make conquests.” Grandeur, Lockwood believed, should depend instead on advancements in industry, commerce, and the arts and sciences, as well as general obedience to the rule of law.Footnote 43

For Lockwood and other Progressive peace advocates, the distinction between civilized arbitration and savage warfare was captured by the near simultaneity of the War of 1898 and the First Hague Peace Conference the following year. Despite innumerable pleas and petitions from peace organizations such as the American Peace Society and the Universal Peace Union, President William McKinley and Congress refused to consider seriously alternative methods of resolving the dispute with Spain, including arbitration. This stance prevailed in the aftermath of the brief war as well; while the United States congratulated itself on its “benevolent” attitudes toward Cubans and Filipinos, McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt waged a bloody war of pacification in the Philippines, at a cost of over four thousand American and two hundred thousand Filipino lives.Footnote 44 Meanwhile, just twelve days after Spain surrendered to the United States, Russian Tsar Nicholas II issued an invitation to the governments of the world to send representatives to a conference on arbitration and disarmament at The Hague. “In the course of the last twenty years,” he wrote, “the longings for a general appeasement have become especially pronounced in the consciences of civilized nations.” His aim was to harness that sentiment against the ongoing threats of militarism.Footnote 45

The juxtaposition of these events was not lost on peace advocates. They wasted little time calling on Americans to support the Hague Conference as a necessary reaffirmation of America’s civilized nature in the wake of the recent—and ongoing—uncivilized war. “War belongs to the barbarism of the past,” Lockwood argued in 1899, as she reflected on the war. In her mind the war was merely an aberration on the United States’ record of civilized advancements, and she believed it had reinforced Americans’ desire for peace. Whipped into a frenzy by the press, Americans “forgot our civilization, our culture,” she lamented, “and with headlong haste, regardless of rights and wrongs we rushed into war.”Footnote 46 But she was confident that in the war’s wake the “moral force and real civilization of our boasted Christian nation” would prevail, and the United States would relinquish any claim to territories seized from Spain.Footnote 47 Simultaneously, the war had exposed the lack of civilization among Cubans and Filipinos. Like many of her contemporaries, Lockwood cited as evidence Cubans’ lack of gratitude toward the United States. They did “not yet appreciate the great blessings that we desire to confer upon them,” she contended, and she questioned whether such a population would “give us strength and add to our own civilization, who are themselves not yet fully removed from barbarism?”Footnote 48 Nations such as Cuba, Lockwood believed, should not be admitted on equal grounds to the world polity until they were prepared to denounce war and militarism.

By contrast, Nicholas II’s call to The Hague represented for Lockwood a new achievement in civilization. As President of the National Association for the Promotion of Arbitration, she sent a message to the president of the conference underscoring the importance of establishing a permanent arbitral court, both to further the process of disarmament around the world and to eradicate the “old barbaric method of warfare.” To the Universal Peace Union she sent encouragement to continue their work in support of the conference, reminding them that warfare and militarism were still too widely celebrated in American society. And in her 1899 pamphlet, Peace and the Outlook, she expressed her hope that “the day is not far distant when [war] will be banished, not only by civilized, but by savage nations, and all of their difficulties be settled by International Courts.”Footnote 49

Lockwood was by no means the only woman peace reformer who espoused civilizationist rhetoric. It was common within the WCTU and appeared regularly in Bailey’s speeches and writings on arbitration. “The eyes of the people of all civilized nations are surely opening to the sinfulness of warfare and the righteousness of peace,” she told the first Lake Mohonk Conference in 1895.Footnote 50 In addition to progress on arbitration, she saw the institutionalization of international law as a sure sign of progress: “It is an encouraging sign of the times that some of the colleges have professorships of International Law, and one can advance the cause of civilization by furnishing funds to institute such a chair where there is none. Law is the opposite of war, as order is of chaos.”Footnote 51 The WCTU greeted Nicholas II’s invitation to the Hague as the “beginning of the end of wars” and announced they were “in favor of a permanent court of arbitration for all civilized nations.” Bailey even suggested that had such a court existed earlier, the War of 1898 might have been averted.Footnote 52

Many women proponents of arbitration joined the anti-imperialist movement in the wake of the war, although they had a harder time marshaling opposition to U.S. foreign policies in Cuba and the Philippines than they had marshaling support for arbitration. Not all suffragists, for example, condemned the imperial endeavor, and not all of those who did believed weighing in on U.S. policy was as important as the ongoing struggle for the vote. Susan B. Anthony supported arbitration and the Philippine War, arguing that if left to their own devices Filipinos would “murder and pillage every white person on the island.”Footnote 53 She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton also hoped supporting U.S. foreign policies would help curry favor with lawmakers. The war thus did not spark a uniform position among organization women as arbitration had done, but the latter issue primed them to make connections between suffrage and foreign policy.Footnote 54

Just as it had for the causes of temperance and suffrage, the issue of arbitration fit easily into women’s calls for civilized conduct in international affairs. It became the centerpiece of Lockwood’s agenda in the 1890s, not only because she earnestly believed in the cause but also because it fit with her general mindset that human society was progressing away from barbarism and toward civilization. For her, the gradual widespread adoption of law and peaceful methods of settling disputes was both a symptom of that progress and a catalyst for its continuance. The same mindset informed women’s perspectives on the War of 1898 and its aftermath. Whether they supported or opposed U.S. policy, they could use arbitration as a standard for measuring both the capacity of Cubans and Filipinos for self-government and their own country’s adherence to civilizational norms.

***

Representatives from twenty-six countries, including the United States, Britain, France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary, attended the First Hague Conference in 1899, where they agreed to prohibit certain war tactics and establish a Permanent Court of Arbitration. The conference represented the first modern effort to create institutional mechanisms for cooperation among nations. In its wake, governments continued to take tentative steps toward that end, while the peace movement in the United States grew rapidly. In 1907, the Second Hague Conference brought forty-four nations together to establish conventions on the laws of war, naval warfare, neutrality, and on renouncing the use of force to collect international debts. The delegates also agreed that periodic conferences were helpful in making progress toward solutions of international problems and agreed to meet again in 1915. That meeting never took place.

All of these efforts were superficial at best. None of the agreements reached at the Hague conferences was binding, and the United States was not the only country that routinely flouted them. They provided opportunities for congenial rhetoric, but they did not lead to peace or even to a genuine acceptance of international arbitration. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, touted his success at arbitrating a settlement of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905—and accepted the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts—and then sent the U.S. Navy around the world in a vast display of military might.

For organized women, the arbitration movement of the 1890s left a different legacy. Mobilization in support of the cause nurtured women’s sense that they had important contributions to make in the realm of U.S. foreign policy and spurred organizations like the WCTU and the NCW to pressure policymakers. Women’s knowledge on the issue gave them the language with which to call on President McKinley to avoid war with Spain in 1898 and to critique the subsequent war in the Philippines. After the turn of the century, women’s organizations continued to voice their opinions on arbitration as well as issues like militarism and naval buildup.

In many ways these arbitrationists were the foremothers of the world citizens who rose to prominence after 1900. World citizenship, as I have defined the term, represented three things for women in the early twentieth century: a determination to participate in shaping the global polity, particularly through some form of world government; an obligation to work for peace; and a belief in the equalizing potential of citizenship.Footnote 55 Bailey, Sewall, and Lockwood did not envision a world government as such, but they undoubtedly felt a strong sense of responsibility to create a peaceful world, and they certainly saw in women’s suffrage an opportunity for more equal citizenship for white women. Their work inspired women like Lucia Ames Mead, who became the most widely recognized women’s peace advocate in the country between 1900 and 1914 and who discerned in the Hague Conferences the germ of a potential world federation.Footnote 56

Women’s advocacy for arbitration also laid the groundwork for the broad, transnational peace movement that arose during World War I. Jane Addams cited arbitration as a key precursor to international law and a necessary step toward reducing the “impulses to war.”Footnote 57 In 1915 Addams cofounded the Woman’s Peace Party and presided over the International Conference of Women at The Hague. There the delegates called on warring nations to begin peace negotiations and on neutral nations to mediate an end to the war. It was one of women’s broadest international attempts up to that time to influence foreign policy. Even after World War I, echoes of suffragists’ demands for a permanent court of arbitration could be seen in the League of Women Voters’ appeal to the United States to join the World Court.Footnote 58

Women’s advocacy for international arbitration in the 1890s thus not only helped propel that movement; it also established the idea that organized women could and should influence U.S. foreign policy, whether by educating Americans on the issues, mobilizing members, drafting resolutions, or lobbying policy makers directly. The ways in which women connected the cause to their efforts for temperance and suffrage made the inclusion of foreign policy seem a natural outgrowth of their existing work. In the process, women’s support for arbitration in the 1890s set the stage for the dramatic expansion of their efforts to shape U.S. foreign policy throughout the twentieth century.