In today’s social environment, our daily life is filled with electronic media devices such as smartphones, tablets and computers. With the development of technology and expansion of many functions, smartphones have replaced cell phones, personal computers and other devices. They are used not only for social networking purposes but also for features including checking emails, texting, playing online games and watching videos. As necessities, smartphones can bring great convenience to our lives and gratify our desires and needs. However, we should note that as many individuals repeatedly use these devices, users increasingly struggle to escape the trap of smartphones and make themselves susceptible to excessive use (Thomée, Härenstam, & Hagberg, Reference Thomée, Härenstam and Hagberg2011). Due to continual use, such users might neglect their schedules and become economically and psychologically affected (Aljomaa, Qudah, Albursan, Bakhiet, & Abduljabbar, Reference Aljomaa, Qudah, Albursan, Bakhiet and Abduljabbar2016).

Excessive smartphone use is also known as mobile phone addiction, mobile phone dependence, mobile phone addiction tendency, and no cell phone anxiety (Billieux, Van Der Linden, & Rochat, Reference Billieux, Van Der Linden and Rochat2008; Ezoe et al., Reference Ezoe, Toda, Yoshimura, Naritomi, Den and Morimoto2009; Hong, Chiu, & Huang, Reference Hong, Chiu and Huang2012). It has been argued that excessive smartphone use could be viewed as a form of behavioral addiction like gaming addiction or problematic social networking service (SNS) usage (Cha & Seo, Reference Cha and Seo2018; Demirci, Orhan, Demirdas, Akpinar, & Sert, Reference Demirci, Orhan, Demirdas, Akpinar and Sert2014; Van Deursen, Bolle, Hegner, & Kommers, Reference Van Deursen, Bolle, Hegner and Kommers2015). Concerning debate about behavioral addictions (Peters & Malesky, Reference Peters and Malesky2008), excessive use implies that a person uses his/her smartphone in a manner that leads to excessive outcomes. Thus, without making a clinical judgment concerning whether a person has the mental disorder of addiction, the term excessive smartphone use is used herein to refer to problematic mentality or behavioural occurrence due to smartphone overuse (Su et al., Reference Su, Pan, Liu, Chen, Wang and Li2014).

Prior studies have demonstrated that excessive smartphone use could accompany negative outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, self-disclosure, and poor academic performance (Aljomaa et al., Reference Aljomaa, Qudah, Albursan, Bakhiet and Abduljabbar2016; Goswami & Singh, Reference Goswami and Singh2016). However, excessive smartphone use is positively associated with perceived stress (Wang, Wang, Gaskin, & Wang, Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015), child neglect, and psychological abuse (Sun, Liu, & Yu, Reference Sun, Liu and Yu2019). Although existing studies have mostly focused on the negative outcomes of excessive smartphone use, little knowledge has been gained on the dynamic and protective factors in the development of excessive smartphone use. Excessive smartphone use is similar to other forms of excessive use, such as online game addiction, problematic SNS use, and cyber addiction (Samaha & Hawi, Reference Samaha and Hawi2016; Snodgrass, Lacy, Eisenhauer, Batchelder, & Cookson, Reference Snodgrass, Lacy, Eisenhauer, Batchelder and Cookson2014; Tavolacci et al., Reference Tavolacci, Ladner, Grigioni, Richard, Villet and Dechelotte2013). However, excessive smartphone use can be different from these types because smartphones are multifunctional aggregates, which probably lead to more serious consequences (Rhiu, Ahn, Park, Kim, & Yun, Reference Rhiu, Ahn, Park, Kim and Yun2016).

In short, few studies have investigated what dynamic factors might lead to excessive smartphone use and whether protective factors might act as buffers that influence the relationships between these factors and excessive smartphone use. Thus, the present study aims to synchronously examine the role of two dynamic factors (i.e., escapism and social interaction motivation) and a protective factor (psychological resilience) in facilitating excessive smartphone use in Chinese college students. Specifically, we investigate the effect of escapism or social interaction motivation on excessive smartphone use and whether psychological resilience moderates the relationship between motivations and excessive smartphone use. We then present a literature review and relevant theories for why we chose these variables.

Motivations and excessive smartphone use

Psychologists (Hull, Reference Hull1943; Maslow, Reference Maslow1943) consider motivation an internal process that arouses, guides, maintains, and adjusts human behavior. Because excessive use requires time to develop, motivations might play a key role. Motivations are the driving forces behind users’ decisions to use smartphones continuously. Moreover, users might derive pleasurable and rewarding feelings from media usage. Such behavior could thus become habitual or ritualistic (Khang, Kim, & Kim, Reference Khang, Kim and Kim2013). This stage can be further explained by the theoretical perspective of the Uses and Gratification approach. The Uses and Gratification theory treats this behavior as a means of satisfying a user’s psychological needs (Song, Reference Song2004). Moreover, it posits that individuals are active and goal-directed in their media use and intentionally choose media and content to gratify psychological needs or certain types of motivation (Blumler & Katz, Reference Blumler and Katz1974).

Prior studies have examined motivations as predictors of users’ excessive reliance on media. Concerning mobile phone use, users’ need for instantaneousness, mobility, interest, information and social status serve as primary motives that can lead to excessive reliance on mobile phones (Lee, Reference Lee2002). Lee, Chang, Lin, and Cheng (Reference Lee, Chang, Lin and Cheng2014) indicated that entertainment, stress relief, instantaneousness, mobility, interest, information, and social status were the major motives for smartphone use. Furthermore, Lowry, Gaskin, and Moody (Reference Lowry, Gaskin and Moody2015) discovered that entertaining oneself and escaping reality were two of the essential functions of smartphone use and that this usage pattern might help people relax. Other motivations for using smartphones include strengthening users’ family bonds, expanding their psychological neighborhoods, facilitating symbolic proximity to the people they call (Wei, Reference Wei2006), and passing time (Wei, Reference Wei2008).

Among all the motivations, we chose escapism and social interaction motivation for our study. Since a mobile phone is predominantly utilized for communicating with others, social relationship was the only motive found to be significantly associated with mobile phone addiction (Khang et al., Reference Khang, Kim and Kim2013). To escape the harsh realities and worries of life or to relax after a hard day at work can impel people to continuously use media (Henning & Vorderer, Reference Henning and Vorderer2010; Yee, Reference Yee2006; Yen et al., Reference Yen, Yen, Chen, Wang, Chang and Ko2012). Both Western and Eastern research on adults or teenagers has shown a positive correlation between escapism and excessive smartphone use (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Gaskin and Moody2015; Wang, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015). Therefore, we propose our first two hypotheses:

H1: Escapism motivation would have a significantly positive correlation with excessive smartphone use.

H2: Social interaction motivation would have a significantly positive correlation with excessive smartphone use.

Psychological resilience and excessive smartphone use

Confronted with pressures in their education, romantic relationships and employment, teenagers’ mental health problems have also become increasingly serious. Many factors can affect their mental health and lead to risky behaviors, of which one frequently studied factor is resilience. Resilience is a multidimensional concept, including process, dynamic, capacity, and outcome dimensions (Masten, Reference Masten2011; Rutter, Reference Rutter2010). Following the framework of positive psychology and its buffering effect on problem behaviors, psychological resilience refers to a personal trait that inoculates individuals against the impact of adversity or traumatic events (Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003). Moreover, psychological resilience attaches great importance to the potential forces of individuals and related environment factors, which is also conducive to the overall development of individual quality.

Evidence suggests that resilient people have a better mental health status, including factors such as greater self-regulatory skills, higher self-esteem and greater parental support. Moreover, individuals’ psychological resilience might play an important role in preventing the emergence of problematic behaviors. Several studies have found that psychological resilience correlated negatively with smartphone addiction (Kim & Roh, Reference Kim and Roh2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Huh, Cho, Kwon, Choi, Ahn and Kim2014; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Ye, Jin, Xu and Li2017), problematic social networking use (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Wang, Guo, Gaskin, Rost and Wang2017), and internet addiction (Eksi, Reference Eksi2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Shi, Wang, Shi, Yang, Yang and Shi2010; Robertson, Yan, & Rapoza, Reference Robertson, Yan and Rapoza2018; Wolfradt & Doll, Reference Wolfradt and Doll2001; Wu, Chen, Tong, Yu, & Lau, Reference Wu, Chen, Tong, Yu and Lau2018; Zhou, Zhang, Liu, & Wang, Reference Zhou, Zhang, Liu and Wang2017). Furthermore, its protective role in decreasing problematic behaviors has also been reported in the fields of gambling addiction (Lussier, Derevensky, Gupta, Bergevin, & Ellenbogen, Reference Lussier, Derevensky, Gupta, Bergevin and Ellenbogen2007), alcohol misuse (Alvarez-Aguirre, Alonso-Castillo, & Zanetti, Reference Alvarez-Aguirre, Alonso-Castillo and Zanetti2014; Green, Beckham, Youssef, & Elbogen, Reference Green, Beckham, Youssef and Elbogen2014), frequent smoking (Goldstein, Faulkner, & Wekerle, Reference Goldstein, Faulkner and Wekerle2013), eating disorders (Hayas, Calvete, Barrio, Beato, Muñoz, & Padierna, Reference Hayas, Calvete, Barrio, Beato, Muñoz and Padierna2014), and drug abuse (Buckner, Mezzacappa, & Beardslee, Reference Buckner, Mezzacappa and Beardslee2003; Cuomo, Sarchiapone, Giannantonio, Mancini, & Roy, Reference Cuomo, Sarchiapone, Giannantonio, Mancini and Roy2008).

Based on the aforementioned studies, psychological resilience might play an important role in preventing the emergence of excessive behaviors. Following this logic, we adopt psychological resilience as a protective factor and propose our third hypothesis:

H3: Psychological resilience would have a significantly negative correlation with excessive smartphone use.

Psychological resilience as a moderator

Based on the Resilience Framework theory, Kumpfe and Bluth (Reference Kumpfe and Bluth2004) suggested that psychological resilience would be an important protective factor of individual mental health and problem behavior. Moreover, as a multidimensional construct, resilience includes stable personality variables as well as skills (Li & Miller, Reference Li and Miller2017). In extant studies, psychological resilience was found to buffer the relationship between risk factors (i.e., learning stress, perceived stress and depression) and addictive behaviors (i.e., internet addiction and problematic SNS use; Choi, Shin, Bae, & Kim, Reference Choi, Shin, Bae and Kim2014; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Wang, Guo, Gaskin, Rost and Wang2017).

Prior studies have also proved that excessive use was directly related to the users’ motivations and psychological resilience (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Wang, Guo, Gaskin, Rost and Wang2017; Lee, Reference Lee2002; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chang, Lin and Cheng2014). However, few have examined how the interaction effect of motivations (i.e., escapism and social interaction) and psychological resilience might affect excessive smartphone use. Employing a direct effects approach, it remains unclear how an individual’s dynamic factors and their motivations for using the smartphone together shape how the phone is being used (Katz & Blumler, Reference Katz and Blumler1974) and when this usage leads to excessive outcomes (Kardefelt-Winther, Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014a). Therefore, additional research is needed to accurately simulate the more complex and interactive nature of the antecedents of excessive use.

The theoretical basis of this interaction model is based on the excessive technology use theory. According to Compensatory Internet Use theory, negative life situations can give rise to a motivation to go online to alleviate negative feelings, which means that a user’s motivations to cope with life problems via internet use is determined by the degree of life problems experienced (Kardefelt-Winther, Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014a). That being said, the relationship between motivations and excessive smartphone use should be moderated by their level of psychological resilience. From this perspective, an individual’s psychological well-being and motivations for using the smartphone should be combined to understand how the process underlies the problem. Based on this logic, Kardefelt-Winther (Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014b) examined the interaction effects of stress or self-esteem and escapism motivation on excessive online gaming and found that both stress and self-esteem moderated the association between escapism motivation and excessive online gaming. Similarly, Wang, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015) investigated the effects of perceived stress and motivations on problematic smartphone use among college students and found that of the users who scored high on problematic use, the relationship between entertainment or escapism motivation and problematic smartphone use was moderated by perceived stress. As psychological resilience provides individuals with the ability to respond effectively to risk and protect their mental health (Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003; Dyrbye et al., Reference Dyrbye, Power, Massie, Eacker, Harper, Thomas and Shanafelt2010), it is an important indicator of psychological well-being. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to examine whether psychological resilience is a protective factor between motivations and excessive smartphone use, and our specific hypotheses are:

H4: Psychological resilience would moderate the relationship between escapism motivation and excessive smartphone use.

H5: Psychological resilience would moderate the relationship between social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use.

Methods

Participants

From two universities in Sichuan Province, China, 600 students were selected as our subjects from whom we obtained 576 (M age = 20.05, SD age = 1.38, 45% male) valid questionnaires, which represent a 96% response rate. All participants identified themselves as smartphone users. Concerning their grades, 20.1% were freshmen, 43.1% were sophomores, 27.6% were junior students, and 9.2% were senior students. The major distribution of the participants was 46.9% for natural science (computer science, chemistry, physics, math and biology) and 53.1% for social science (philosophy, politics education, law, business administration, economics and philology). Selected via advertisements in the autumn semester in 2018, all the participants provided written informed consent and received monetary compensation (¥10, or about $1.5 USD) if they finished their questionnaires. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of our university.

Measures

Smartphone Addiction Scale for College Students (SAS-C)

Items for measuring the degree of excessive smartphone use were designed by Su et al. (Reference Su, Pan, Liu, Chen, Wang and Li2014). Containing 22 items, the self-report SAS-C scale used a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The higher scores imply higher levels of excessive use. Sample items included “If I couldn’t play with my smartphone for a while, I would feel anxious” and “Because of my smartphone, my academic performance has dropped”. The Cronbach coefficient was .91 in this study. The scale also had good construct validity and the estimates of the measurement model were χ2/df = 4.32, comparative fit index (CFI) = .88, incremental fit index (IFI) = .88, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .07, standardised root mean residual (SRMR) < .001.

Smartphone Usage Motivation Scale

Adapted from the Social Media Usage Motivation Scale (Wang, Jackson, Wang, & Gaskin, Reference Wang, Jackson, Wang and Gaskin2015), the items for measuring escapism and social interaction motivations were revised to fit the background of smartphone use. Responses were obtained using a 5-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating a higher motivation. The Escapism Motivation subscale had three items; sample items were “I use my smartphone to escape from my family or other people” and “I use my smartphone to get away from what I’m doing”. The Social Interaction subscale included three items; sample items were “I use my smartphone to keep in touch with my friends and family” and “I use my smartphone to keep in touch with my close friends”. Cronbach coefficients in our study were .86 and .82 for escapism and social interaction motivation respectively. The scale also had good construct validity and the estimates of the measurement model were χ2/df = 3.71, CFI = .94, IFI = .94, RMSEA = .07, SRMR < .001.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003) was used to measure psychological resilience, which consisted of 25 items. Participants responded to each item according to their experiences during the previous month. Each item used the form of a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (true nearly all of the time). The higher scores represented higher levels of psychological resilience. Sample items included “I have a strong sense of purpose” and “I would not be easily defeated by failure”. In this study, Cronbach’s coefficient was .92. It had good construct validity and the estimates of the measurement model were χ2/df = 3.73, CFI = .90, IFI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR < .001.

Analytic strategy

SPSS19.0 and Mplus 7.4 were used to conduct descriptive, correlation, and moderation analyses. First, we conducted descriptive statistics and correlation analysis using SPSS 19.0. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the strengths of linear relationships among all the variables. Then, a latent moderated structural equations (LMS) method was conducted to analyse the moderating effect using Mplus 7.4. As a method to analyse the interaction effect of latent variables, LMS was implemented with Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2010). When the moderating effect was significant, we then followed Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken’s (Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2013) recommendations and plotted the results to interpret the nature of the interaction between the two predictor variables. Specifically, the relationship between the first predictor variable (i.e., escapism motivation) and the dependent variable (i.e., excessive smartphone use) was plotted when levels of moderator (i.e., psychological resilience) were one standard deviation below and above. The statistical significance of each of these two slopes was also tested (Aiken, West, & Reno, Reference Aiken, West and Reno1991), which represented the simple effects of the predictor variable on excessive smartphone use at two levels of psychological resilience. Moreover, considering that prior studies have demonstrated that gender (Takao, Takahashi, & Kitamura, Reference Takao, Takahashi and Kitamura2009) and age (Walsh, White, & Young, Reference Walsh, White and Young2008) influence smartphone use, age and gender were involved as control variables in our model.

Results

Descriptive analyses

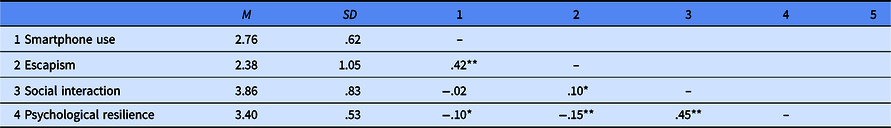

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables in our study. Escapism motivation correlated significantly with excessive smartphone use (r = .42, p = .00; supporting H1). However, social interaction motivation (r = −.02, p = .81) had no statistically significant correlation with excessive smartphone use (H2 was not supported). In addition, concerning H3, psychological resilience had a significantly negative correlation with excessive smartphone use (r = −.10, p = .04; H3 was supported).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations of variables for the participants (N = 576)

Note: **p < .01, *p < .05.

Moderating effect analyses

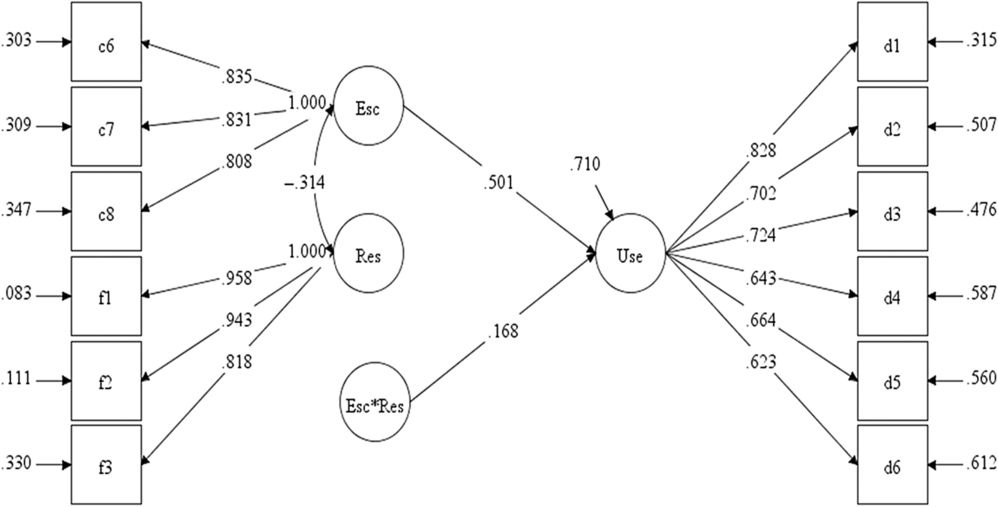

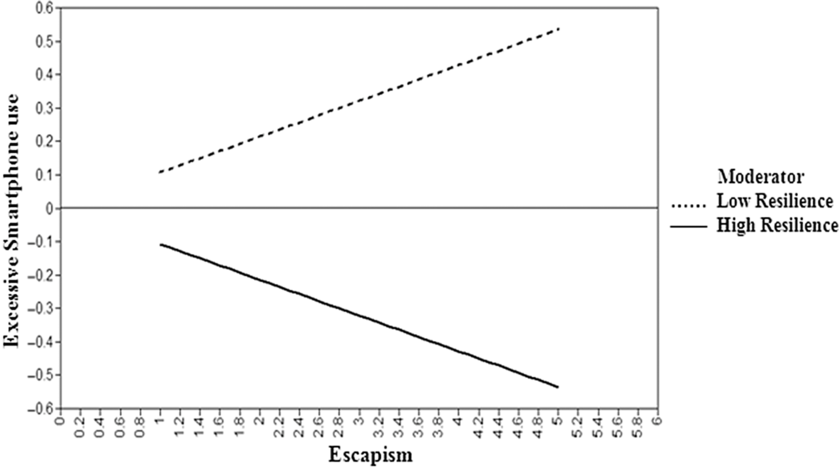

Regarding H4, we ran an LMS analysis that included the interaction term between escapism motivation and psychological resilience. Figure 1 shows that psychological resilience did not significantly predict excessive smartphone use (β = −.03, p = .73), whereas escapism motivation and the interaction term were significantly related to excessive smartphone use, with β = .50, p = .00 and β = .17, p = .02 respectively. Based on these results, psychological resilience was a moderator between escapism motivation and excessive smartphone use. Furthermore, we conducted a simple slope analysis to explore the influence mechanism of the moderator on excessive smartphone use. The results indicated that the relationship between escapism motivation and excessive smartphone use was significant for participants with low psychological resilience (β = .30, p = .00), whereas no significant relationship was obtained for participants with high psychological resilience (β = −.14, p = .26) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Path graph of the moderated mediation model for entertainment motivation.

Figure 2. A diagram of how psychological resilience moderates the relationship between escapism motivation and excessive smartphone use.

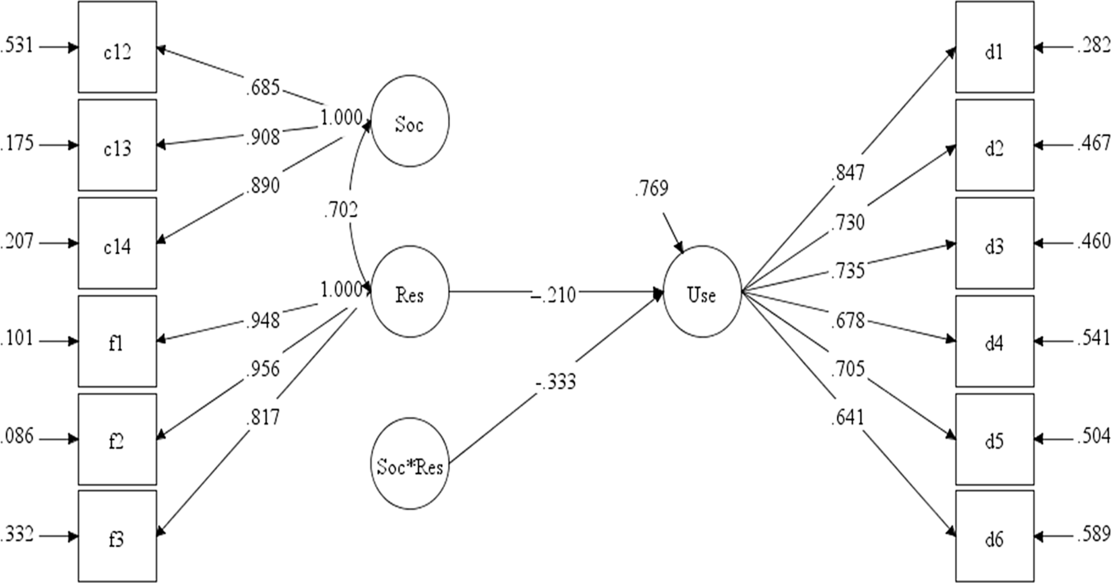

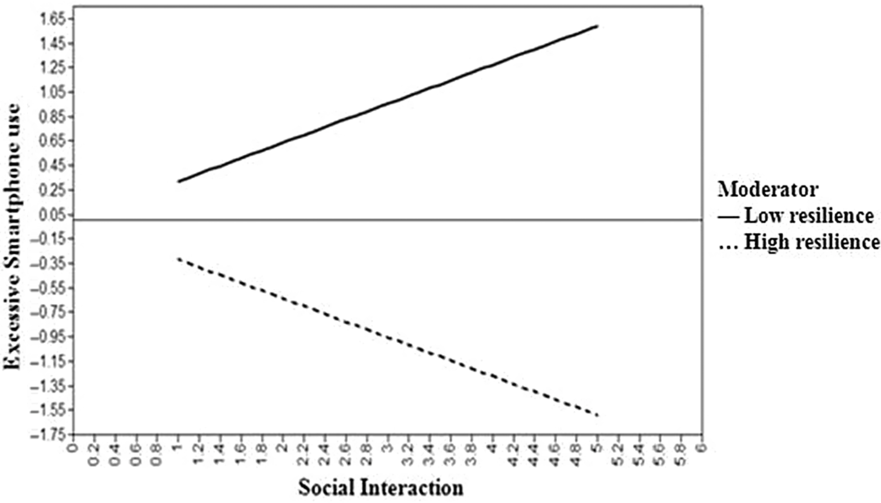

A similar procedure was conducted to test H5 and included the interaction term between social interaction motivation and psychological resilience. As shown in Figure 3, psychological resilience and the interaction term were significantly related to excessive smartphone use (β = −.21, p = .01, and β = −.33, p = .00 respectively), whereas social interaction motivation was not (β = −.06, p = .37). We then conducted a simple slope effect analysis, which showed that the relationship between social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use was significant for participants with low resilience (β = .21, p = .01), whereas this association became nonsignificant for participants with high resilience (β = −.12, p = .29) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Path graph of the moderated mediation model for entertainment motivation.

Figure 4. A diagram showing how psychological resilience moderates the relationship between social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use.

Discussion

Our contribution to the literature is that we have tested the protective factor of psychological resilience between motivations and excessive smartphone use. Our findings demonstrated the important role played by real-life needs in explaining this maladaptive usage of smartphones. Following the framework of positive psychology and compensatory internet use theory, our present work employed an LMS to analyse the moderating effect of psychological resilience between motivations and excessive smartphone use. Here, it was interesting that escapism motivation and psychological resilience had significant correlations with excessive smartphone use, whereas social interaction motivation did not. Furthermore, for escapism and social interaction motivation, psychological resilience moderated the relationship between these two motivations and excessive smartphone use.

Of our five hypotheses, four have been supported by our findings. H1 and H2 indicated that the correlations between escapism, social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use were significantly positive. Concerning our findings, H1 has been supported. We found that escapism motivation had a positive correlation with excessive smartphone use, which is consistent with previous studies (Wang, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015). This could be partially explained by the uses and gratification theory, which emphasizes the users’ own conscious dynamic role and their media use intent to satisfy their inner needs rather than passive reception. Thus, escapism motivation stimulating a human being’s evasive desires was considered a significant predictor of excessive smartphone use. However, H2 was not supported, as we did not find a significant positive correlation between social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use. This result was different from previous research, which found that social relationships was the only motive found to be significantly associated with mobile phone addiction (Khang et al., Reference Khang, Kim and Kim2013). A possible explanation is that with their rapid development, smartphones are no longer extensions of communication but combinations of surfing the internet and entertainment. Concerning H3, we found that psychological resilience had a significantly negative correlation with excessive smartphone use. This finding was consistent with previous studies (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Wang, Guo, Gaskin, Rost and Wang2017; Liao, Ye, Jin, Xu, & Li, Reference Liao, Ye, Jin, Xu and Li2017). Possessing specific characteristics such as a sound perspective on reality, a strong capacity for reflection, a responsible nature and a high tolerance for negative feelings, highly resilient people could be more proactive in challenging situations and better able to cope with life problems. Moreover, when facing negative life events, these individuals might not indulge themselves in smartphone use but adopt positive and effective coping strategies to solve these problems (Sun, Niu, Zhou, Wei, & Liu, Reference Sun, Niu, Zhou, Wei and Liu2014).

Moreover, our study attempted to investigate whether psychological resilience would be a protective factor between motivations and excessive smartphone use, and we built two moderation models to clarify their internal mechanisms. As expected, we found a significant interaction term between escapism motivation and psychological resilience, which could significantly affect excessive smartphone use. From this, we knew that psychological resilience was a protective factor between escapism motivation and excessive smartphone use, which confirmed H4. The same finding emerged with H5, which obtained an interaction term between social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use. Especially for those scoring high on psychological resilience, escapism and social interaction motivations had not led to maladaptive patterns of uncontrollable smartphone usage that can result in social or occupational negative outcomes. These findings demonstrated that theories of positive psychology and the compensatory internet use were consistent with previous studies (Kardefelt-Winther, Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014b; Wang, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015). Kardefelt-Winther (Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014b) found that the interaction of psychological well-being and escapism motivation led some people to be excessive users, which may eventually result in excessive consequences. Likewise, Wang, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Wang2015) indicated that the effects of motivations on excessive smartphone use depended upon the level of users’ perceived stress. These findings illustrated how the multiple mechanisms between motivations and individuals’ personality traits in leading to excessive outcomes when using media served as a major coping strategy for life problems (Kardefelt-Winther, Reference Kardefelt-Winther2014a). Specifically, it should be noted that the relationship between motivations and excessive smartphone use was significant for participants with low psychological resilience. Therefore, when designing interventions to target excessive users, mental health practitioners should focus on the training of psychological resilience and coping skills in life events rather than overemphasize behavioral therapy to decrease users’ motivations.

Several study limitations should be acknowledged. First, when generalizing to other populations, the levels of education background and specific characteristics of our participants should be considered. Second, as our study was a cross-sectional design, regarding causality, special attention should be devoted to the interpretation of our results. Future studies might use experimental and longitudinal designs, which could identify causal relationships among these variables. In addition, Knobloch-Westerwick, Hastall, and Rossmann (Reference Knobloch-Westerwick, Hastall and Rossmann2009) noted that it should be crucial to investigate how specific media content provides solutions for real-life problems in a more detailed manner. Future researchers should consider whether different functions of smartphones reflect different motivations for their use; this subdivision of functions can be more useful for understanding the mechanism behind the overuse of smartphones.

Conclusion

To summarize, we found that escapism motivation and psychological resilience correlated significantly with excessive smartphone use, whereas social interaction motivation did not. Considering the moderating effect, psychological resilience moderated the relationship between escapism or social interaction motivation and excessive smartphone use. Therefore, our study highlights the protective factor of psychological resilience and confirms that excessive users use media more often as a coping mechanism for life problems. From this perspective, future researchers can emphasize resilience training that would help train people to be able to cope with life problems more effectively.