What do adolescents want from democracy in the twenty-first century? This is a crucial question, not only because adolescents form the next generation of democratic citizens but also because democratic support of young people matters for the quality of future liberal democracy (Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Tomescu‐Dubrow, Slomczynski and Dubrow2020). Previous research has concentrated on preferences of young citizens for democracy per se. In this regard, Foa and Mounk (Reference Foa and Mounk2016) diagnosed a ‘democratic disconnect’, suggesting that young people are abandoning democracy as a key value and are more open to alternative forms of government, such as strongman leaders or even military rule. These findings provoked much criticism and were largely refuted by subsequent studies (e.g., Huttunen & Saikkonen, Reference Huttunen and Saikkonen2023; Norris, Reference Norris2017; Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022). A key counterargument is that young citizens may be dissatisfied with the performance of democracy but still support democratic principles. They are just not happy with how mainstream political practice works and feel excluded and ignored in the political process (Pickard, Reference Pickard2019). Building on this perspective, our article turns a new page: instead of analysing support of young citizens for democracy per se, we ask more precisely what they want from democracy, that is, how democracies should be designed to generate support and legitimacy for young citizens.

This research note provides fresh empirical evidence on this under-researched question.Footnote 1 It also addresses the question how current crises of democracy with rising levels of political polarization, growing inequality and the failure of established democratic procedures to address existential problems such as climate change affect democratic preferences. Are young citizens ‘turning away’ from the legacy institutions of the current representative democracy and seeking something new, such as direct rule by citizens (e.g., in the form of randomly selected citizens’ forums) or executive forms of governance (e.g., a democratically elected assertive leader)? Or do adolescents want to preserve what they have and know, which in terms of democracy in Germany are the legacy institutions of the representative system?

To test these two basic expectations, we map adolescents’ attitudes toward different forms of decision making – ranging from representative to participatory and executive modes – by studying a specific policy decision on the introduction of a carbon tax to mitigate climate change.Footnote 2 We conducted a pre-registered conjoint experimentFootnote 3 with a unique, representative sample of 1,970 mostly 15-year-olds in Germany. Compared to standard surveys, conjoint experiments are better suited to capture abstract concepts such as process preferences for democratic designs. Conjoint experiments confront participants with realistic decision-making processes on salient political issues, which helps adolescents to better imagine what they want from democratic governance. While it could be argued that research on process preferences of young people might tap into non-attitudes, previous research has shown that adolescents (and even children) are capable of evaluating decision-making processes and different government systems (see Helwig et al., Reference Helwig, Arnold, Tan and Boyd2003). To address potential concerns, we conducted a cognitive pretest and a pilot study and included several robustness checks.

Our conjoint experiment employs a novel modular design, enabling respondents to directly compare different decision-making models, including the option of ‘blended’ forms of governance, that is, combinations of representative and direct-democratic modes of governance (see Saward, Reference Saward2021). Specifically, we presented respondents with three main decision-making institutions: a parliament (representative mode), a randomly selected citizen forum (participatory mode) and a democratically elected assertive leader (executive mode). By adding an executive-mode scenario, we expand existing research on process preferences, which usually focusses on contrasting representative with participatory or deliberative modes. Yet, recent research on process preferences suggests that some citizens may favour more delegative and executive forms of decision making (see Bertsou, Reference Bertsou2021). It is imperative that respondents with attitudinal sympathies for executive modes of governance are given a relevant choice option in surveys (rather than being forced to choose between alternatives they may not fully endorse). We further innovate by combining the three main institutions with additional qualifications and institutional options, such as special consideration of expert or public opinion, fast and slow decision making, and final decisions made by referendum or by the main institution. With special consideration of expert opinion and fast decision making we measure preferences for expertocratic and efficient modes of governance, respectively. Final decision making by referendum captures preferences for citizen involvement via direct democracy (participatory mode), while final decision making by the main (or multiple) institution(s) measures preferences for majoritarian and executive modes of governance.

In the remainder of this article, we first formulate general expectations about process preferences of adolescents, followed by expectations about the preferences of specific subgroups. We then present the setup, the data and methods, followed by the results and a discussion.

Theoretical framework

Our research questions revolve around general preferences for various decision-making procedures and heterogeneity in preferences, with a focus on (dis-)satisfaction and political sophistication. Since research on process preferences of young citizens and adolescents is in its infancy, we cannot rely on established hypotheses. However, our research is not entirely exploratory. To formulate theoretically informed expectations, we draw on research on adolescents as well as the growing literature on procedural preferences of adults (for an overview on current research on process preferences see König et al., Reference König, Siewert and Ackermann2022).

Regarding preferences for governance models, a first expectation is that adolescents may be generally open to alternative forms of governance because their political preferences are not as firmly established as those of adults, making them ‘influenceable’ in their so-called ‘impressionable years’ (Alwin & Krosnick, Reference Alwin and Krosnick1991). In addition, several studies found that young people are generally disappointed with electoral politics and have a negative view of politicians and political parties since the latter are not responsive to their demands (Chou, Reference Chou, Chou, Gagnon, Hartung and Pruitt2017; Pickard, Reference Pickard2019). Times of crisis might exacerbate antipathy to the current system (see Foa & Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Wenger, Rand and Slade2020). Another argument is that due to generational differences in values, adolescents are in general more open to participatory modes of governance (e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton2016). However, as we argue below, this may only apply to some adolescents. ‘Influenceability’ is open-ended and can make adolescents also susceptible to populism, for instance (Noack & Eckstein, Reference Noack and Eckstein2023). Hence, demands for alternatives may also entail support for an assertive leader who ‘gets things done’ in an efficient and fast way.

Expectation 1a: Adolescents prefer alternative forms of governance (citizen-led institutions or an assertive leader) to the status quo (representative institutions).

An alternative expectation is that adolescents stick to what they have and support the legacy institutions of the representative system, even – or especially – in times of crisis (see Huttunen, Reference Huttunen2021). German adolescents have most likely been socialized in a representative democratic system (e.g., Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2013). According to political socialization research, the development of political orientations is highly influenced by prevailing norms and the values of the current democratic system (e. g. Almond & Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963).

Expectation 1b: Adolescents prefer the status quo (representative institutions).

Research on adults, however, suggests that a large majority of German citizens support an integrated (or ‘blended’) system of democratic governance, involving multiple players and combining representative, deliberative and direct-democratic elements (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Wyss and Bächtiger2020; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Vittori, Rojon and Paulis2023a). We argue that this might be also true for adolescents. They may want to enrich the legacy institutions of the representative system (e.g., with direct-democratic instruments) so that representative institutions become more responsive.

Preference heterogeneity

We expect considerable preference variation among different subgroups of adolescents, a topic neglected in previous studies on adolescents’ democratic preferences (e.g., Foa & Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2016). Given the fact that democratic attitudes developed in adolescent years influence attitudes in adult years (see Hooghe & Wilkenfeld, Reference Hooghe and Wilkenfeld2008), it matters for future democratic stability (see Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Tomescu‐Dubrow, Slomczynski and Dubrow2020) when some groups of young citizens have highly divergent process preferences. This may undermine attempts to build robust democratic architectures that are supported by large societal majorities. Following the literature on adults, we focus on two crucial dimensions of preference heterogeneity, namely democratic (dis-)satisfaction and political sophistication, and explore how much different types of adolescents actually differ in their process preferences.

Dissatisfied versus satisfied adolescents

In expectation 1a, we describe a general trend of adolescents’ dissatisfaction with the current system, prompting demands for alternative forms of governance (e.g., Foa & Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019). However, the number of adolescents who are unhappy with how current democracy works, while significant, is not indicative of a general trend.Footnote 4 Research on adults (see e.g., Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Wyss and Bächtiger2020; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2023b; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2021) shows that dissatisfied citizens do want something else from democracy and prefer any alternative to the current representative system (including participatory alternatives), whereas satisfied citizens are more likely to prefer the status quo (representative forms of governance; see Coffé & Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2014).

Expectation 2: Dissatisfied adolescents are more likely to prefer alternatives (citizen forums or assertive leader) to the status quo than satisfied adolescents.

High versus low political sophistication

Drawing on the ‘new politics’ approach (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Burklin and Drummond2001), we expect that especially politically sophisticated adolescents (with higher education and higher political interest) prefer participatory forms of governance. They feel competent enough to have a say in politics and are doubtful of hierarchical authority structures in the representative system (Dalton, Reference Dalton2016). In contrast, we expect politically less sophisticated adolescents to have process preferences that are less carefully considered (and to be more receptive to alternatives that are less democratic, such as assertive leaders).

Expectation 3a: Sophisticated adolescents – with higher education and higher political interest – are more likely to prefer participatory forms of governance than less politically sophisticated adolescents.

There is, however, an alternative expectation. Education in particular is closely linked to the social status of the adolescents’ parents (Ermisch & Pronzato, Reference Ermisch and Pronzato2010).Footnote 5 Ceka and Magalhães (Reference Ceka and Magalhães2020) show that citizens with a higher socioeconomic status are associated with a preference for the status quo (regardless of whether the regime is democratic or autocratic). Based on these findings – using education as a proxy for privileged adolescentsFootnote 6 – we expect that adolescents with higher education have strong attitudinal sympathies for the status quo, since they (or their families) have benefited – and will benefit – from the current system.

Expectation 3b: Adolescents with higher education (proxying higher social status) express stronger preferences for the status quo (representative system) than adolescents with lower education.

At the same time, politically sophisticated adolescents (including higher educated adolescents) might have contradictory motives, both for preserving the status quo and for adopting more participatory forms of governance. These may foster attitudinal sympathies for ‘blended’ governance systems combining representative and participatory modes.

Outcome favourability

Finally, procedural preferences need to be analysed in conjunction with substantive preferences. Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002) have long argued that support or legitimacy feelings for governance systems hinge both on institutional design and on substantive policy preferences. Several studies highlight the magnitude of the effect of outcome favourability, showing that the less the outcomes of a governance system correspond to respondents’ own policy preferences, the less positive their evaluation of this system is (e.g., Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Therefore, we expect outcome favourability to play an important role in the evaluation of governance systems, especially when an important issue such as climate change mitigation measures (in our case, the introduction of a carbon tax) is under scrutiny. In addition, we analyse whether preferences for institutional choices differ according to outcome favourability or whether they are robust regardless of whether respondents are ‘winners’ or ‘losers’.

Expectation 4: Adolescents are more likely to prefer a decision-making process that leads to their preferred outcome.

Setup, data and methods

We conducted a conjoint experiment with 1,970 German pupils aged 14 to 17, most of whom were 15 years old. The data was collected online from February to April 2022 in the context of a youth study of the Ministry of Education in Baden-Württemberg (Germany). It comprised 93 year-nine classes of all school tracksFootnote 7 in Baden-Württemberg. The response rate was 76 per cent, which is very high compared to standard surveys. The cases were weighted by school track, since the response rates differed per school type. Overall, our sample corresponds to nation-wide distributions regarding gender and high-school attendance for 15-year-olds (for a full documentation, see Supporting Information Appendix A1).

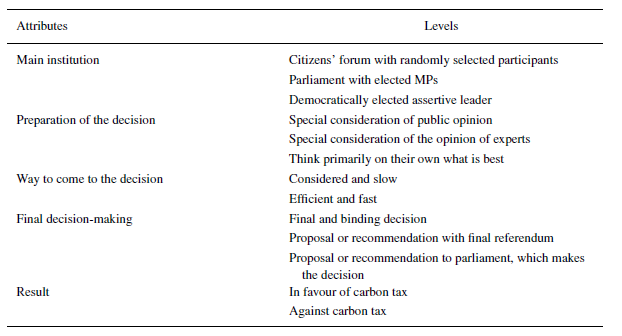

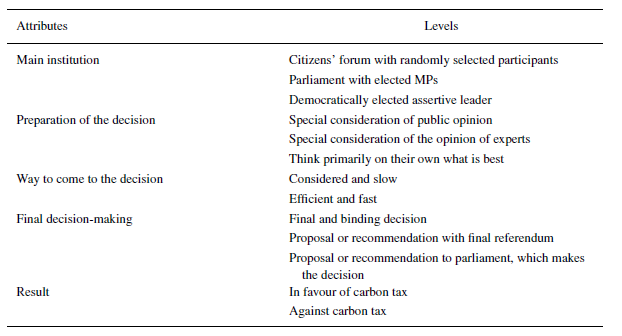

Our setup builds on the idea that governance systems have some foundational main institutions. We focus on a parliament with elected representatives, a democratically elected assertive leader and a citizen forum.Footnote 8 We add further qualifications and institutional options to the main institutions: (1) preparation of the decision, with the options of special consideration of expert opinion, special consideration of public opinion and preparation by the main institution itself; (2) the way to come to a decision, where we focus on fast and slow decision making; and (3) final decision making, where we distinguish between a final and binding decision by the main institution, a proposal or recommendation with a final referendum (adding a direct-democratic component) and – in the case of the citizen forum and the assertive leader – a proposal or recommendation to the parliament, which makes the final decision. To capture outcome favourability, we focus on climate change, which turns out to be a highly salient issue for our respondentsFootnote 9 and is one of the most pressing issues for the youth (e.g., Sloam et al., Reference Sloam, Pickard and Henn2022). Specifically, we asked about the introduction of a carbon tax on flights (Table 1).Footnote 10

Table 1. Conjoint design.

Our conjoint experiment has five dimensions, with each dimension comprising two or three levels, all randomized.Footnote 11 Each respondent was confronted with twelve randomized scenarios, comparing two scenarios in each round (see Supporting Information Appendix A3 for examples of the conjoint comparison). For our main analysis we used binary choice questions on support. In addition, all effects were calculated with rating questions on decision acceptance as a robustness check. Prior to the conjoint experiment, respondents were presented with an information sheet, including explanations on each dimension and attribute level (see Supporting Information Appendix A2). Given the fact that a conjoint setup is novel in the study of adolescents’ process preferences and that adolescents often have little knowledge about politics, we performed a cognitive pretest (face-to-face interviews) and a pilot study. We confronted them with think-aloud questions and verbal probing questions to identify any difficulties and misleading phrasing and explanations.Footnote 12

For the subgroup analysis, we employed the following survey questions. For satisfaction with democracy we used standard items, whereas political sophistication was measured through political interest. As recent research suggests, political interest may also represent an excellent proxy for political knowledge (Rapeli, Reference Rapeli2022). For both variables, we applied median splits (see Supporting Information Appendix A4). Regarding education, we focused on pupils attending the ‘highest’ school track in Germany (Gymnasium) versus pupils attending one of the other three school tracks.Footnote 13 Finally, outcome favourability was calculated by comparing respondents’ preferences on the introduction of a ‘carbon tax’ with the randomly assigned output of the conjoint exercise, assigning participants to ‘match’ or ‘mismatch’.

To analyse support of adolescents for different democratic scenarios, we use both average marginal component effects (AMCEs) (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and marginal means. AMCEs are causal estimators and allow a causal interpretation of the effect of an attribute compared to the set reference category. However, Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) have warned that using AMCE analysis for descriptive purposes can lead to misleading interpretations; therefore, we also estimated marginal means for the main preferences and the subgroup preferences (see Supporting Information Appendix A6). Results, however, do not differ, neither for the overall nor for subgroup analysis. Our reference categories for the AMCEs are chosen on the following basis: the status quo of decision making (e.g., representative system) and minimal influence on the preparation of the decision (e.g., ‘the main institution thinks primarily on its own what is best’ / ‘the actors think primarily on their own what is best’). Since every respondent had to choose from six comparisons and rate 12 profiles in total, choices and ratings are not independent from each other. To account for non-independence of responses, we clustered the standard errors by respondents (see Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).

Results

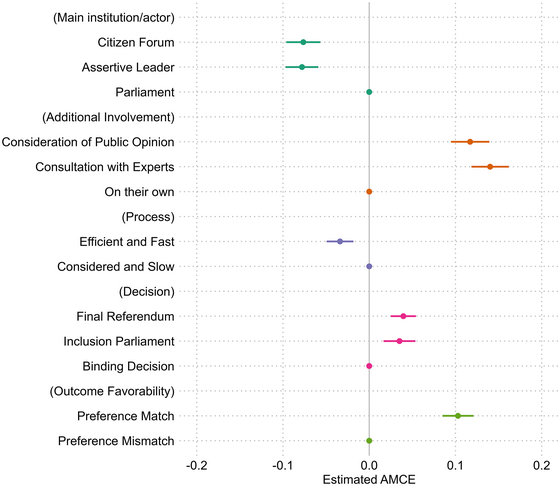

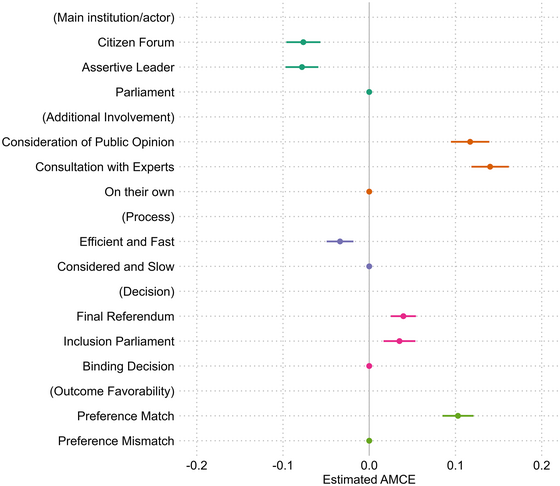

In a first step, we analyse the general preferences of adolescents with a benchmark model that includes all respondents. Figure 1 shows the AMCEs of the design elements and outcome favourability, with the dots with 95 per cent intervals showing the effect of each attribute in comparison to the reference category.

Figure 1. Effects of design levels on choice. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Benchmark model for all respondents. Standard errors clustered at the individual level to take into account that each respondent made several comparisons. N = 23.438 (1970 respondents × 8–12 scenarios). Effects are measured in percentage points. Weighted data.

Respondents of our conjoint experiment in general are less likely to choose a process involving a citizen forum or an assertive leader than a parliament (representing the status quo in Germany)Footnote 14 as the main institution (rejecting expectation 1a but supporting expectation 1b). This is accompanied by preferences for augmenting the legacy institution. Respondents are more likely to choose a decision-making process with additional involvement, namely special consideration of expert or public opinion, than decision making by the main institution on its own. The probability that the decision-making process wins support increases by around 14 percentage points when experts are involved and by around 12 percentage points when public opinion receives special consideration, compared to an independent preparation of the decision by the main institution (these effects represent the strongest observed effects in the conjoint experiment).

Contrary to the popular assumption that rapid decision-making processes or technocratic forms of decision making (especially in the context of pressing environmental problems) are particularly appealing, our respondents are more open to considered and slow than to efficient and fast decision making. The probability of choosing the respective decision-making process increases when the decision is accompanied by a direct-democratic referendum or, in the case of the assertive leader or citizen forum, when the parliament is involved compared to a binding decision by the main institution. Finally, in line with expectation 4, outcome favourability strongly matters to our respondents. Decision-making processes are around 10 percentage points more likely to win support when the outcome aligns with the respondent's policy preference. However, being a policy winner or loser does not alter procedural visions of governance: in both situations, respondents opt for almost similar procedural designs (see Supporting Information Appendix A6).

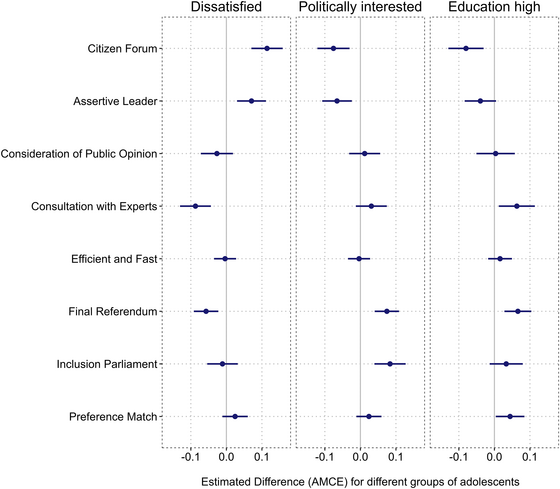

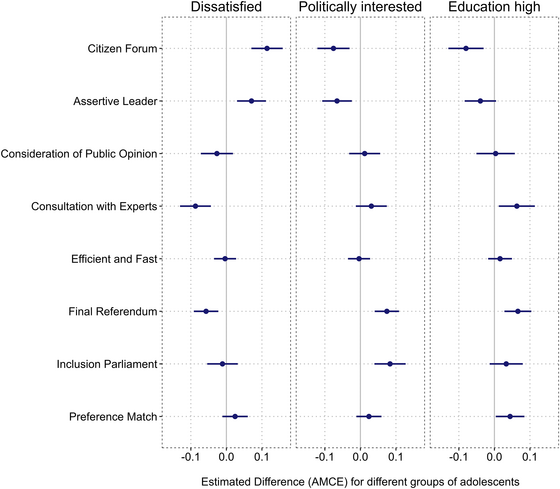

Turning to variations between different types of adolescents (see Figure 2Footnote 15), we focus on dissatisfied and politically sophisticated respondents. Note that all the subgroup effects represent only the difference to the respective opposite group. Supporting expectation 2, we find that dissatisfied respondents are significantly more likely than satisfied respondents to choose a process involving a citizen forum or an assertive leader compared to a parliament as the main institution. This, however, does not mean that they have a clear preference for alternative main institutions; as the descriptive analysis of marginal means shows (see Supporting Information Appendix A6), they also prefer a parliament to an assertive leader. Dissatisfied respondents are as supportive of a citizens’ forum as they are of a parliament as the main institution. Moreover, they are less likely to support a decision-making process with expert involvement than a process with the main institution preparing the decision independently, and less likely to choose a decision-making process with a final referendum. No differences can be found for fast versus slow decision making nor for outcome favourability.

Figure 2. Estimated differences (AMCEs) for different groups of adolescents. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Effects show the increase/decrease in the probability of choosing a scenario for a particular attribute level relative to its baseline level for the specific group (dissatisfied; politically interested; education high) minus the probability of choosing a scenario for the opposite group (satisfied; not politically interested; education low) for the same attribute level relative to its baseline category. Reference categories not shown. Weighted data.

Next, we find that sophisticated respondents – politically interested as well as higher educated respondents – have nuanced preferences, namely both for preserving the status quo and for participatory complements. On the one hand (and in line with expectation 3b), they are significantly less likely to choose a process with a citizen forum as the main institution and, in the case of politically interested adolescents, less likely than less sophisticated respondents to choose a scenario with an assertive leader compared to a parliament. On the other hand (partially in line with expectation 3a), they are also significantly more likely to choose a scenario with a final referendum than politically less interested and less educated respondents. Furthermore, respondents from a Gymnasium are more likely than respondents from other school tracks to choose a scenario where experts are involved in the decision-making process than a scenario where the main institution prepares the decision without external input. They are also significantly more likely to choose a decision-making process where the outcome matches their preference in comparison to lower educated respondents. The fact that climate change represents a more important issue for Gymnasium pupils than for pupils from other school tracks might amplify the effect of outcome favourability.Footnote 16 No differences can be found for fast versus slow decision making.

We ran a number of robustness checks (see Supporting Information Appendix A6-A7): (1) we estimated the cognitive ability of respondents to evaluate decision-making scenarios over contest rounds to probe for the stability of preferences across comparisons; (2) we re-ran all analyses with rating outcome variables as well as models using marginal means estimationsFootnote 17; (3) we compared respondents who spent more time with the pre-conjoint information or the conjoint to respondents who spent less time with that material; (4) we applied an ‘attention check’; and (5), we ran a replication study with a sample of 163 students at the University of Stuttgart in June 2022 (with most respondents aged 21 to 25; see Supporting Information Appendix A8). The findings generally confirm the results reported above with respondents who spent more time with the information sheet and the conjoint tasks, and attentive respondents even showing slightly more pronounced results, strengthening our conclusions.

Discussion

Multiple crises of democracy have not only stimulated a broad debate in society about the future design of democracy, they have also sparked rich academic research on citizens’ preferences for (different) democratic designs. However, young people are mostly excluded from this picture. This is a crucial mistake, since democracies will only thrive when they meet the expectations of the next generation of citizens. Our article addresses this under-researched issue by zooming in on the process preferences of German adolescents using a unique, representative sample of mostly 15-year-old pupils in Germany. Our results show that in general adolescents are solid status-quo democrats who prefer the parliament (the central institution of the existing representative system) to alternative institutions, namely a citizen forum and an assertive leader. This is especially true for sophisticated adolescents with higher political interest and higher education. But our respondents also want additional qualifications and innovations: they prefer qualified input (in the form of expert and public opinion), slow and considerate political decision-making processes and a final referendum or – in the case of the alternatives (assertive leader or citizens’ forum) – an involvement of the parliament as the final decision maker. Put differently, adolescents prefer checks and balances as well as responsible and responsive forms of governance (Mair, Reference Mair2009), demonstrating considerable democratic maturity and sophistication. By the same token, outcome favourability strongly matters for our respondents: when decisions go against their substantive preferences, their support for the decision decreases. But the fact that being a policy winner and loser does barely affect procedural choices also suggests that our findings for institutional design preferences may reach beyond substantive concerns.

When we focus on dissatisfied adolescents, the picture is slightly different. The latter are significantly less supportive of the parliament as the main institution. However, this does not mean that dissatisfied respondents would actually prefer alternative main institutions, for example, an assertive leader, to the parliament. The preference for the representative main institution is just less pronounced. The existing democratic architecture in Germany not only yields strong support among adolescents, there is neither an indication of a ‘democratic disconnect’ (even dissatisfied adolescents dismiss an assertive leader) nor a desire for a citizen-centric alternative (in the form of randomly selected citizens’ forums). Yet, adolescents do support decision making with a direct-democratic referendum, which is, at least at the national level in Germany, a clear departure from the status quo. Nonetheless, the clearly pronounced preferences for a representative governance as the main institution indicates that adolescents mostly ‘stick to the stuff they know’Footnote 18. As such, a radical overhaul of the existing democratic infrastructure does not seem to be a priority for the next generation of citizens, even if their preferences show a clear need for qualification plus some desire for innovation in the form of ‘blending’ representative institutions with more citizen participation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eva-Maria Trüdinger and Saskia Goldberg for essential conceptual input into the conjoint design and extremely helpful comments on the article. Additionally, we thank Hannah Werner for her insightful feedback and comments on the article. We are indebted to Michael Bechtel for his excellent methodological advice. We also thank the participants of the Deliberative Democracy & Public Opinion Summer School 2022 organized by the Åbo Academi in Turku, Finland and participants of the 2022 ECPR General Conference Panel ‘Do citizens even like democratic innovations?’ for their highly valuable feedback. Moreover, we thank the Ministerium für Kultus, Jugend und Sport in Baden-Württemberg and the team of the youth study 2022 for their support and collaboration. Finally, we are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers who provided extremely valuable and constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Ministerium für Kultus, Jugend und Sport (project number KM56-6950-25) and the European Research Council (ERC) (project number 101054111).

Data Availability Statement

Replication material (Data set and R code) is included in the Supporting Information.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 1: Distribution sample and population

Appendix 2: Pre-Conjoint Information

Appendix 3: Conjoint task examples

Appendix 4: Variables

Appendix 5: Feature distribution and subsets

Appendix 6: Additional analysis

Appendix 7: Robustness checks

Appendix 8: Student experiment

Appendix 9: Deviations from Pre-registration