Introduction

There is growing evidence that companion animals may promote physical, mental, and social health and well-being for older adults. Less is known, however, about ways that pet-related challenges may simultaneously influence aging-in-place experiences. Evidence of the health-promoting potential of pets later in life is mixed and even at times contradictory, as captured by two recent reviews (Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud, & Provencher, Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020). Both reviews note that companion animals’ positive influences include enhanced emotional well-being, increased function via meaningful care-related occupation, and increased physical activity with reduced sedentarism (Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020). Negative influences may include the potential for extreme grief upon loss of a pet, risks of pet-related injuries (i.e., falls and bites), and stressors related to demands and costs of pet care (Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020). Given the methodologically diverse state of the literature on pets and aging, both reviews consider findings from a range of study designs (Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020).

These recent reviews have been timely and helpful in recognizing the need to better understand the relational quality of pet ownership. This approach can be challenging when using data sources that are quantitative in design, such as survey-based cohort studies. In many such studies, outcomes of interest are subjective in nature, such as measures of life satisfaction, loneliness, and other forms of psychological or psycho-social well-being. Even when subjective survey measures are valid and psychometrically sound, however, they may be difficult to interpret meaningfully. When considering this situation, Mallinson (Reference Mallinson1998, Reference Mallinson2002) notes several limitations with generating an accurate, trustworthy interpretation of survey data as responses may obscure intricate processes that underlie individuals’ final selections. She argues for the value of using qualitative approaches in concert with quantitative measures to obtain a more nuanced understanding of the meaning of such quantitative measures.

As a case in point, this current study has been inspired by a curious and pervasive quantitative survey finding, that older pet owners’ life satisfaction scores tend to be lower than those of non-pet owners (Himsworth & Rock, Reference Himsworth and Rock2013; Norris, Shinew, Chick, & Beck, Reference Norris, Shinew, Chick and Beck1999; Toohey, Hewson, Adams, & Rock, Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018). This finding contradicts a wealth of literature suggesting that having a companion animal later in life can be beneficial to quality of life, as noted in the above-cited literature reviews (Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020) as well as in a range of methodologically diverse empirical studies (e.g., Bennett, Trigg, Godber, & Brown, Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015; Bibbo, Curl, & Johnson, Reference Bibbo, Curl and Johnson2019; Bibbo, Curl, Johnson, & Marble, Reference Bibbo, Curl, Johnson and Marble2015; Enders-Slegers, Reference Enders-Slegers, Podberscek, Paul and Serpell2000; McLennan, Rock, Mattos, & Toohey, Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward, & Abernathy, Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999; Rock, Reference Rock2013; Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Simonsick, Brach, Ayonayon, Satterfield and Harris2006; Toohey, Hewson, Adams, & Rock, Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). If viewed uncritically, the lower life satisfaction reported by older adults in survey data suggests a direct link between having a pet and experiencing diminished emotional well-being. This simplistic interpretation disregards the fundamental supportive roles that companion animals may play – particularly for socio-economically disadvantaged older adults (Matsuoka, Sorenson, Graham, & Ferreira, Reference Matsuoka, Sorenson, Graham and Ferreira2020; McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Rauktis, Rose, Chen, Martone, & Martello, Reference Rauktis, Rose, Chen, Martone and Martello2017; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). At the root of this problem is a common methodological presumption that having a pet can be likened to an epidemiological “exposure” that will lead to either beneficial or harmful outcomes in those who are “exposed” versus those who are not exposed (i.e., non-pet owners). This view, however, overlooks the relational quality of animal companionship.

Ongoing experiences of having pets later in life are ultimately shaped by a wide array of factors, ranging from individual characteristics of people and pets, their particular life circumstances, and systemic considerations, including availability of affordable and appropriate pet-friendly housing, social support to assist with pet care, and costs of caring for a pet (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). With these concerns in mind, an aim of this current study is to trouble the notion that quantitative measures – even those considered to be psychometrically robust, like the life satisfaction scale (Pavot & Diener, Reference Pavot and Diener2008) – will adequately capture the relational complexities of having a pet. To do this, a re-examination of qualitative data that were originally collected to describe the aging-in-place experiences of a socio-economically diverse sample of older pet owners is presented. This secondary analysis explores the nuanced ways that companion animal relationships may simultaneously support and challenge older adults’ aging-in-place experiences.

Theoretical Framework

Relatively few studies have adopted a population health approach to the study of pets and aging. As such, the physical and social contexts in which both aging and human–animal relationships are experienced have received surprisingly little attention in the literature on pets and aging. A socio-ecological framework (Richard, Gauvin, & Raine, Reference Richard, Gauvin and Raine2011) acknowledges the multiple factors and influences that may shape the quality of human–animal relationships, accounting for individual characteristics as well as community and cultural considerations, systemic practices, and policies. This current study applies a relational socio-ecological framework (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017), which extends Putney’s (Reference Putney2013) original relational ecology theory of the human–animal bond. Relational ecology is rooted in concepts from developmental psychology and human ecology, including lifespan development theory, object relations, holding environment, liminality, and deep ecology (Putney, Reference Putney2013). A relational socio-ecological understanding of human–animal relationships inserts additional layers of influence onto these dimensions by also considering the physical, social, cultural, and policy environments within which older people and their pets experience daily life (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017). Applying a relational socio-ecological lens to the health-promoting potential of pets also accounts for ways that lived experiences of aging-supportive communities are shaped by policies and practices (Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst, & Eales, Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011).

Methodology

Because the phenomenon of aging in place with pets is shaped by multiple, intersecting influences that include individual characteristics, socio-cultural qualities, and policy-level factors, it lends itself to Yin’s (Reference Yin2009) multiple case study methodology. As such, experiences of aging in place with pets were explored within our local setting, Calgary, AB, Canada, from several perspectives, and also in relation to a national longitudinal study that included data about pets (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018). Our municipality is internationally recognized as both a “pet-friendly” and an “age-friendly” city due to its progressive municipal policies (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017), making it an instructive setting for considering this phenomenon. The qualitative components of this case study have involved ethnographic interviews with representatives of the social services and animal welfare sectors, as well as with older adults who were aging in place in a range of social and economic circumstances, to explore both benefits and challenges of aging in place with pets (see McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Krahn, Reference Toohey and Krahn2018; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). The primary quantitative component explored baseline data of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (Kirkland et al., Reference Kirkland, Griffith, Menec, Wister, Payette, Wolfson and Raina2015; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Balion and Cossette2019) to understand associations between pet-ownership, life satisfaction, and social participation (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018).

As an additional qualitative component of the broader case study introduced above, this current study revisits semi-structured interviews originally conducted in 2015 with community dwelling, socio-economically diverse older adults (≥ 60 years) residing with one or more pets. While the original data considered in this study were collected several years prior to embarking upon this secondary analysis, little has changed locally or nationally in the meantime, in terms of policies and practices that enable older adults to manage pet ownership later in life. Furthermore, the dates when these qualitative data were collected are well-aligned with the quantitative component (i.e., Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018), which reports on findings that inspired this secondary analysis. Thus, data contained within these interviews remain relevant to the overarching case study’s objective. Ethics approval for this study was provided by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics Certification REB14-1445).

Research Setting

Previously published components of this case study have drawn attention to the mismatch between our city’s progressive pet policies, its leadership in age-friendly policy implementation, and the systemic barriers to having pets that many older adults face. These barriers include a lack of affordable, appropriate pet-friendly housing as well as a historic lack of coordination between community-based human social service and animal welfare supports (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Krahn, Reference Toohey and Krahn2018; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). These challenges are not unique to our setting (see, e.g., Arrington & Markarian, Reference Arrington and Markarian2018; Matsuoka et al., Reference Matsuoka, Sorenson, Graham and Ferreira2020; Rauktis et al., Reference Rauktis, Lee, Bickel, Giovengo, Nagel and Cahalane2020, Reference Rauktis, Rose, Chen, Martone and Martello2017). Veterinary services in Calgary are also costly, and there is a recognized gap in terms of service support for lower income pet owners (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Van Patten, Chalhoub, Baker, Rock, & Adams, Reference Van Patten, Chalhoub, Baker, Rock and Adams2021). As older adults are often subsisting on pension income, many experience the constraints of living on a fixed or low income.

Sample Recruitment

To recruit socio-economically diverse older adult participants, posters were displayed in the city’s largest community centre for older adults (i.e., “seniors centre”), a central food bank, and a public library. Flyers were also displayed and distributed by two animal shelters that ran active pet adoption programs and had participated in the broader case study (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017). Word-of-mouth voluntarily initiated by key participants in this current study and by representatives of community organizations involved in the study also led to recruiting four socio-economically disadvantaged participants who would not likely have seen the posters. Inclusion criteria for participation included age (≥ 60 years) and living independently in the community with a pet, although one participant (Participant 6) had recently lost her dog companion.

Sample Description

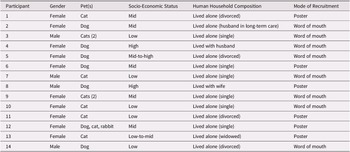

As illustrated in Table 1, 12 of the 14 older adults who voluntarily participated in this study lived alone. Of these 12, 6 were single, 4 were divorced, 1 was married with a spouse living in a long-term care facility, and 1 was widowed. Most participants (10) were female. Seven participants owned one or more cats, 6 owned a dog, and 1 had multiple pets.

Table 1. Overview of participants recruited for interviews to explore community-dwelling older adults’ experiences with aging in place with companion animals

Nine of the study participants were retired. Nine owned their own home, including condominiums. The remaining 5 lived in disadvantaged circumstances, with 3 residing in subsidized older adult housing units and 2 in private market rentals. Lower income participants were supported by government-sponsored disability income, old-age pension, low-income supplement, or a combination of these, depending upon eligibility (Government of Alberta, 2020).

Data Collection

The author conducted semi-structured ethnographic interviews (Spradley, Reference Spradley1979) with eligible participants (n = 14). Informed consent was provided and interviews typically lasted 60 minutes, ranging from 45 to over 90 minutes. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed in all but one case, as Participant 4 declined to be recorded. Detailed field notes were prepared immediately following each interview to capture impressions and insights (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, Reference Emerson, Fretz and Shaw1995), and research memos were also created by the author during transcription and analysis, when additional insights arose.

Nine interviews took place in a participant’s home, with their pet(s) present and interactions observable (Ryan & Ziebland, Reference Ryan and Ziebland2015); 2 interviews took place in a community-based old adults centre that supported this study’s recruitment, 1 happened in a public library, and 2 occurred outdoors in public parks, each with the participant’s dog present. The participants interviewed at the older adults (“seniors”) centre shared photographs of their pets. All but 1 participant declined to choose a pseudonym for their pet and preferred that their pet’s or pets’ given name(s) be used.

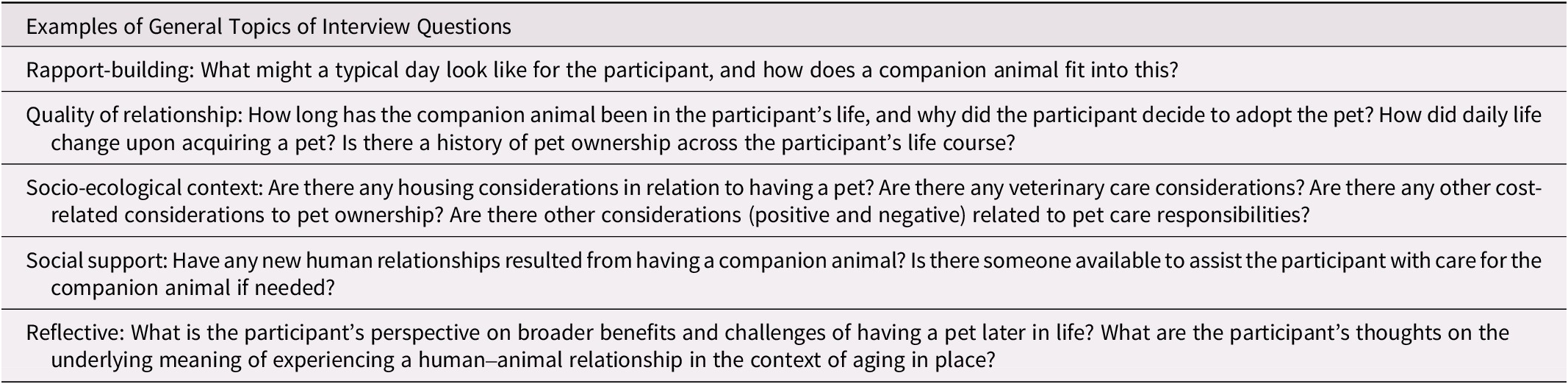

To build rapport at the outset of the interview (Spradley, Reference Spradley1979), the author asked each participant to describe their daily experience of living with and caring for their pet. Additional prompts ranged from requesting descriptions of daily activities and routines, to inquiring about reflections on perceived benefits and challenges of having pets in later life, both personally and for older adults more generally (Table 2).

Table 2. Sample interview questions used to facilitate semi-structured interviews with research participants

Analytic Approach

At the outset of the secondary qualitative analysis, the author’s re-immersion into these data involved an in-depth review of initial field notes for each interview, followed by rereading all interview transcripts. These initial impressions helped inform the reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2020) that was then undertaken. The next analytic step was to consider the entire set of interviews, paying close attention to instances when participants reflected on the challenges of their overarching life circumstances, in relation to both aging in place and their companion animal(s). Simultaneously, the author considered participants’ descriptions of the different ways that companion animals shaped quality of life both positively and negatively, broadly, as well as in relation to the challenges they faced. Comparisons were made both within and between interviews. Attention was paid to semantic rather than latent meanings of the data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2020), because the participants’ own words depicted meaningful interactions between current life circumstances and relationships with pets.

Through a process of (re)immersion and crystallization (Borkan, Reference Borkan, Crabtree and Miller1999), the author identified thematic patterns across the corpus of interviews that offered insights into ways that both the benefits and challenges of companion animals influenced older adults’ aging-in-place experiences. As the sole interviewer and research lead for the case study, the author’s intimate familiarity with the complete data set underscored an immersive, substantive qualitative analysis, as has been well-described by others (Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, Reference Eakin and Mykhalovskiy2003). The analysis was reflexive, shaped by the author’s understandings of both theoretical and practical dimensions of aging in place with pets and the various contradictions that exist within its evidence base. The author’s own experiences with the complexities and negotiations of having both cat and dog companions at different life junctures also informed how participants’ accounts were interpreted.

Findings

In reflecting on their experiences of aging in place with a pet, participants discussed many positive and compelling attributes of having an animal companion later in life. However, many also recounted challenges they were facing, linked to later life issues and related transitions. Recurring examples of challenging circumstances brought up by participants included loneliness, chronic illness, reduced mobility, depression and anxiety, financial uncertainty, housing insecurity, reduced social support, feelings of social isolation, loss of people and pets, and constrained personal freedoms. The various, and often contradictory, ways that pets were experienced in relation to this array of challenging life circumstances are encapsulated in the four themes discussed below.

Theme 1: Lonely But Not Alone

The first theme describes both the impacts and limitations of human–animal relationships on loneliness. Several participants reflected on experiences of loneliness and their sense that they lacked fulfilling human relationships. Yet these feelings were balanced by recognizing ways that their pets enhanced their day-to-day experiences and made them feel less solitary in their lives. For instance, Participant 3 was a highly educated single man in his late 60s who was experiencing severe mental and physical health challenges, extreme low income, and social isolation. He lived with a pair of cats, Brady and Kaboodle, one of whom he was fostering for a local rescue and treating for Feline HIV. He was candid about his sense of isolation and loneliness, and reflected the following:

I’m still lonely a lot of the time here. I’m isolated. I don’t have a tremendous social life. And my cats give me something (pauses) ‘someones’ [sic] to attend to … I can’t imagine being without them. I can’t imagine being here alone. But at the same time, they don’t fulfil all my affiliative needs, you know? Being single and having cats is better than being single and not having cats. But – I’d rather not be single.

Participant 5, on the other hand, was an educated, divorced woman in her early 70s who had financial security and family support. She spoke openly about the ways that her dog, Molly, had extended her social network via meeting people at her local dog park: I spend a lot of time by myself, so being forced into social contacts is very good for me. And yet, like Participant 5, she also recognized the limitations of Molly’s companionship:

One of the hard times of the day for me is going home from the dog park. That’s really the time of day I feel alone. I think it’s kind of a low time of the day, you’re hungry, and you know (pauses), and a lot of people are going home to somebody else and I’m not. So Molly doesn’t fulfil that need, right?

Participant 1, an older, divorced woman in her mid-80s was financially comfortable and was actively engaged in community services. She described her recent acquisition of an older cat named China:

So she came to my house … and she just immediately settled into the whole place, she was all over the place, making herself right at home. And I found I really liked her. She’d be running to the door to meet me at night, and then she’d be there in the morning, and I just liked it.

The simple presence of another living creature co-habiting within a solitary home environment brought a new dimension of comfort and companionship to Participant 5’s life.

Theme 2: Precarious But Committed

The second theme reveals ways that older adults felt a deep sense of solidarity for their companion animals and responsibility for their pets’ lives and well-being, even as these commitments exacerbated challenging circumstances. One such situation was described by Participant 10, a single, lower-income woman in her mid-60s, who had unexpectedly lost her mobile home due to water damage:

… three years ago, there was trouble in my trailer. There was a leak in the water main and they couldn’t turn it off…so my trailer eventually had to be destroyed… and that’s when I realized the chief of my concern was my cat. ‘Cause what will you do with your cat, right?’

Her age and income rendered her eligible for subsidized older adult housing, yet she could not find housing that would accept her cat, Kismet. As a result, she navigated three years of housing insecurity, during which time she described situations where she placed her integrity and even personal safety in danger, first by keeping her cat illegally in a subsidized housing unit (they were ultimately evicted), and next by boarding with a man whom she knew to have alcoholism linked to violent outbursts. Still, she remained steadfast that throughout this time, noting: my cat, she was a saving grace really because she was so resilient.

Participant 14 was an older, single gentleman in his early 80s, whose monthly income consisted solely of government pension and low-income supplements. He had little familial support, having been divorced and pre-deceased by all his siblings and his two children. His large dog, Jellybean, was his sole companion. When we spoke, Participant 14’s apartment building was for sale, and he was becoming increasingly desperate to find an affordable rental that would accept Jellybean. Few apartments in Calgary, let alone affordable ones, permitted tenants to keep dogs (as described in Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017), and those that did had a strict size limitation that Jellybean, over 100 lb in weight, substantially exceeded. Participant 14 reflected:

That’s why a lot of dogs and cats get abandoned! It’s because the people have [the pet], and they gotta move—they get evicted, or they just have to move for some reason, and they got a pet, and they can’t find a place, So the only way they can do it is they gotta abandon the—I’d never do that with him anyway. I’d live on the street first.

These types of concerns were not limited to participants with lower incomes. Participant 13 was a widowed 65-year-old who lived alone in a condominium that she and her then-deceased husband had purchased, and which she outright owned. A year prior to our interview, she had spent a substantial portion of her retirement savings on cancer treatment for Casey, her cherished dog. Her account of this decision was unequivocal:

The cost of handling Casey was so high, I just ended up shredding everything. I didn’t want to know what the final bill was. That’s why I won’t be able to retire… And I do not begrudge any money I spent to make sure Casey was well looked after or anything, but it’s led to other issues.

At the time when we spoke, she had acquired a new kitten, Mara, to offset the loneliness of widowhood. She was struggling with the costs of addressing the kitten’s severe dental issues: I have financial worries, but because I had a dog for 15 years, and my husband was gone, everything was gone. I needed something to take care of. She admitted to worrying about the possibility of losing her home, and yet parting with her new kitten was not negotiable. The need to care for and love another creature outweighed her unexpected insecurity around her finances and even her home.

Theme 3: Caring as Defying Emotional Adversity

The third theme illustrates ways that pet-care roles and animal companionship offered a form of meaning and continuity in older adults’ lives as they experienced life-altering situations that might otherwise erode emotional well-being. One such narrative was shared by Participant 9. She was a single, retired woman in her mid-60s who lived with her two cats, Nick and Stella, in a condominium she owned. Following a routine surgical procedure on her spine, she was left with severely reduced mobility. She discussed coming to terms with her physical impairment and, especially, her shrinking physical and social worlds. Her attachment to this pair of rescued cats and the continuity her cats facilitated, despite the major upheaval taking place in her life, helped her experience an emotional richness that she felt would otherwise have eluded her:

The cats have been my biggest and longest emotional commitment. I didn’t know I had this in me, I really didn’t, you know. Like when people say they have a child they never realized they were capable of loving something that much, and I feel that way about the cats.

Participant 7 described another scenario where continuity was paramount to his ability to cope with a life-changing event. He was a well-educated single man in his early 60s who had held a fast-paced professional career in sales. He suffered a sudden, major stroke, which was then followed by a lengthy rehabilitation period. He depleted his retirement savings during his initial years of recovery, anticipating an eventual return to the workforce. The cognitive damage caused by the stroke prevented this from happening: I went from a six-figure-a-year job to a $502/month pension. That was it!

Early in his recovery, when his physical and cognitive regains were unknown and his financial reserves disappearing, Participant 7 focused on caring for his cat, Kleo. The routines of care he had established for his cat provided meaningful links to his previous state of being. Even as he came to terms with his declining function, his new life circumstances revolved around a precise feeding schedule, methodical litter box cleanings, and a comforting bedtime routine as he and his cat settled in for the night. He described these activities in a way that reflected both their crucial importance to his sense of self-efficacy and his deep attentiveness to his cat’s needs. Eventually, when Participant 7 could no longer afford to stay in his rented apartment, he was shocked at how few options remained:

I couldn’t believe when (the housing advisor) told me there was only one place – with all of the money and everything we have in Calgary, and where’s the legislation? I wouldn’t be living at [Building Name], or anywhere without Kleo. I’d be renting a room somewhere for $500 a month. In a basement. Probably an illegal (secondary) suite. Because there’s no way I would give up the cat!

Over the course of our interview, Participant 7 described a multitude of indignities and hardships. His story illustrated how his reliance on both the affection and continuity offered by caring for Kleo helped him transition through these challenging and adversities.

Theme 4: Losses Versus Gains

The fourth and final theme explores pet-related constraints that some participants described, yet also illuminates a subtle process of balancing costs versus benefits of having companion animals in later life. One relevant account was shared by Participant 2, an older, married woman in her mid-70s whose husband was residing in a long-term care facility due to advanced dementia. Relocating from her longtime detached home into a congregate rental apartment gave rise to challenges with her small Havanese dog, Toad (this requested pseudonym symbolized for Participant 2 the enduring friendship described in Lobel’s (Reference Lobel2013) classic children book series, “Frog and Toad”). She reflected:

I can’t leave him in the apartment. Because he will bark if he’s left alone. And this was new to me when I moved into the apartment…I can’t go to a restaurant! I live in a neighbourhood with interesting restaurants, and stores, and I can’t go and just dawdle along the street and enjoy myself because of him…

Toad’s behaviour, which led quickly to complaints from neighbours and warnings from management, severely constrained Participant 2’s ability to manage her new situation in the way she had envisioned. She eventually solved this challenge by enlisting the services of a pet-sitter and also enrolling him in a part-time “doggie day care” service. Notably, though, Participant 2 also credited Toad with social benefits, including a growing sense of belonging and community: And the dog of course is always an intro [sic]… it’s a positive note in a day. She also described Toad’s ability to facilitate positive interactions with her husband and the care staff when they visited him in his care home. In essence, Participant 2 viewed Toad’s barking as a singular problem with a solution, while she recounted numerous other ways that her relationship with Toad enhanced her quality of life and ability to cope with new challenges. Observing Participant 2’s interactions with Toad during our interview also confirmed her strong attachment to and fondness for him.

Costs and benefits of pets later in life were also considered by Participant 12. She was a recently retired professional in her mid-60s who had four companion animals: two cats (I adore them), a domesticated feral rabbit (…really a sweet pet), and a beagle whom she had adopted from neighbours to prevent the dog’s being relinquished to a shelter (But the work, oh, you can imagine). In volunteering to participate in this study, she had been especially anxious to ensure that the oft-ignored challenges of having pets after retiring were articulated and considered. Reflecting on the varied ways that these three relationships shaped her life in retirement, she shared:

It is difficult at times, because we wait for those golden years, senior years. I’m a young senior, I’m just 65 this year and I come into having the dog now, she is going to be 8. You know what I’d say to [other] seniors: get a rabbit, get a gerbil, or a hamster. I’d say get a rabbit or a cat. If you’re a senior, avoid a dog unless it’s a real old dog, small and doesn’t need a lot of walks and you have an area where the dog can relieve itself.

Her frustration with the complexities of being responsible for a dog was tangible throughout our interview. Still, she also noted several positive dimensions of caring for Sophie. These included their regular walks through her neighbourhood, during which informal interactions led to a sense of being recognized and valued in a meaningful way. Overall, she confided: So I feel ethically, morally like I’ve done something good for a creature…(but) I’m on overload. I’ve done too much. I tell myself this all the time. I should surrender one of the pets. Participant 12’s retired life had not unfolded as she had hoped, and she understood this to be a direct result of her over-extended responsibilities for her animal companions. Of all 14 interviews, hers was the singular one that conveyed a concern with the potentially negative impact of pet ownership later in life. For Participant 12, the costs associated with her pets, and particularly her dog, outweighed the benefits and were eroding her quality of life.

Discussion

The insights shared in the above thematic analysis illustrate a balance of both positive and negative dimensions of pet ownership later in life, and the potential of human-animal relationships to shape overall quality of life and influence individual experiences of aging in place. Within this socio-economically diverse sample, many older adults’ stories highlighted challenges that they were facing in their later years, ranging from catastrophic illness to financial insecurity, to unfulfilling personal relationships. While relationships with pets were sometimes central to these challenges, pets were consistently recognized as enhancing quality of life in a compelling range of ways. Companion animals were able to offset loneliness. They provided companionship and opportunities to enact routines of care. They were an avenue for deep emotional connection while embodying qualities like resilience, that older adults could emulate. In almost all cases, they were experienced as a source of continuity, during periods when older adults were redefining their selves and identities through adverse life changes. In one case, the toll taken by commitments to pet care was felt to be too high, despite the acknowledged benefits. The realities shared in the participants’ narratives confirm the relational nature of human–animal relationships as being contingent on the circumstances of people’s lives and personal situations, as other researchers have also found (Applebaum, MacLean, & McDonald, Reference Applebaum, MacLean and McDonald2021; Bibbo et al., Reference Bibbo, Curl and Johnson2019; Gee & Mueller, Reference Gee and Mueller2019; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Michaud and Provencher2020; Obradović, Lagueux, Latulippe, & Provencher, Reference Obradović, Lagueux, Latulippe and Provencher2021; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019).

It is valuable to consider both the benefits and challenges of human–animal relationships from a social justice perspective. The perspectives of socio-economically disadvantaged pet-owners are largely absent from the study of pets and aging. Social justice arises when some groups face forms of oppression or unfair restrictions on autonomy due to their particular situations or identities. Within this study’s socio-economically diverse sample of older adults, those participants living in lower income and socially isolated circumstances often experienced pressing systemic-level uncertainties. Their commitments to their pets were non-negotiable, though, even as they faced, considered, or directly experienced precarious and inappropriate housing to protect their animal companions. The continued shortage of pet-friendly and affordable housing for older adults perpetuates an ongoing source of social injustice for this sub-group of older adults, who often have little more than the relationship with their pet to help retain a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives (Matsuoka et al., Reference Matsuoka, Sorenson, Graham and Ferreira2020; McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Krahn, Reference Toohey and Krahn2018; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). Issues around pet care challenges also emerged frequently, including looming costs of veterinary care when their pet became ill. As a promising response, however, community-based, pet-care assistance programs for older adults are becoming increasingly common worldwide (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022). Even so, such support falls short in situations where appropriate, pet-friendly housing supply is lacking (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Krahn, Reference Toohey and Krahn2018; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019).

The nuanced complexities of human–animal relationships described by the study participants support continued efforts to bring together animal welfare and human social services agencies to serve older adults and their pets in an integrated rather than disparate way. This would ideally include relational coordination across sectors (Gittell, Reference Gittell, Spreitzer and Cameron2011; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017), such that housing providers, veterinarians, health care providers, charitable organizations such as food banks, the pet industry, local bylaw officers, and other relevant stakeholders are able to work together to support the multiple and multi-species facets of aging in place. As noted in McLennan et al.’s (Reference McLennan, Rock, Mattos and Toohey2022) environmental scan, efforts to protect human–animal relationships for older adults are gaining traction on an international scale. Despite these efforts, demand exceeds supply when it comes to scarce resources dedicated to keeping human–animal relationships intact when personal or systemic barriers arise. The complexities and contradictions revealed by the older adults participating in this study lend further evidence to the importance of ensuring that efforts to support aging in place consider pets. Gaining an understanding of whether a pet’s role in an older person’s life may be simultaneously contributing to and eroding function, mental health, and social connection for the older adult will help establish appropriate supports that are both humane and anchored in values of social justice and social inclusion. Increasing the scope and capacity of community supports that cross species lines is a promising way forward from both population health and animal welfare perspectives.

The complexities and contradictions linked to human–animal relationships presented in this study also confirm the necessity of adopting methodologically nuanced approaches that can appropriately address the relational and multidimensional influence pets may have on health and well-being. The finding that inspired this analysis – that older adults with pets are often found to report lower levels of life satisfaction than those without pets – raises methodological questions. Practically speaking, there are numerous rich, comprehensive, and often longitudinal survey-based studies available to researchers that offer a wide range of health-related and socio-demographic data and that often include measures of pet ownership. Quantitative work to date has undeniably advanced understandings of pets and aging (e.g., Bibbo et al., Reference Bibbo, Curl, Johnson and Marble2015; Enmarker, Hellzén, Ekker, & Berg, Reference Enmarker, Hellzén, Ekker and Berg2012; Garrity, Stallones, Marx, & Johnson, Reference Garrity, Stallones, Marx and Johnson1989; Himsworth & Rock, Reference Himsworth and Rock2013; Pikhartova, Bowling, & Victor, Reference Pikhartova, Bowling and Victor2014; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999; Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Simonsick, Brach, Ayonayon, Satterfield and Harris2006; Toohey, McCormack, Doyle-Baker, Adams, & Rock, Reference Toohey, McCormack, Doyle-Baker, Adams and Rock2013, Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018). Yet contradictory evidence arises, often across the quantitative and qualitative divide.

To start bridging this divide, mixed methods that combine qualitative and quantitative approaches hold promise. Many of the challenges captured in this study’s findings might suggest a link between pets and lower life satisfaction, as measured using the popular Satisfaction With Life Scale (Pavot & Diener, Reference Pavot and Diener2008). This interpretation would certainly be consistent with the published literature (Himsworth & Rock, Reference Himsworth and Rock2013; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Shinew, Chick and Beck1999; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018), and yet the qualitative results reported in this study also reiterate that the direction of influence of a pet on this subjective psychological state is not predictable, as per Mallinson’s (Reference Mallinson1998, Reference Mallinson2002) observations around ways older adults may complete survey questionnaires. Even when pets were central to older adults’ challenges, the relational benefits of companionship, responsibility, acts of care, and other dimensions of pet-keeping were also recognized as anchoring and enhancing quality of life.

This present qualitative study is a component of a broader case study that was determined a priori to involve a mixed methods approach, considering both quantitative and qualitative data sources. However, qualitative data are not always readily available to enhance quantitative, survey-based analyses. In such cases, the use of appropriate statistical approaches to drill down into complex mechanisms, such as exploring mediation or effect modification, holds promise. For instance, by stratifying their national Statistics Canada-derived data set by sex, marital status, and household composition, Himsworth and Rock (Reference Himsworth and Rock2013) found that companion animals appeared particularly supportive for older women who were divorced and living alone, compared to their non-pet owning counterparts. Similarly, Toohey et al.’s (Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018) stratified analysis of Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) participants suggested that while older pet owners reported significantly lower life satisfaction than non-pet owners, pets appeared to have a positive influence on the well-being of those older pet owners when poor health and social isolation were barriers to achieving desired levels of social participation. In considering loneliness, Pikhartova et al.’s (Reference Pikhartova, Bowling and Victor2014) analysis of European Longitudinal Study on Aging (ELSA) participants found that older pet owners were significantly more likely to report loneliness than were non-pet owners. Yet this longitudinal analysis also suggested that for older women, pet ownership both had a protective effect on loneliness over time, while loneliness also predicted pet acquisition later in life. Taken together, these examples reinforce the importance of recognizing the complex mechanisms that may shape the direction of association between relational phenomena and subjective outcomes like life satisfaction or loneliness, as are frequently used to understand and represent quality of life of older adults.

The complexities of older adults’ experiences with pets, including contradictory ones, can be understood with reference back to the relational socio-ecological framework. Putney’s (Reference Putney2013) original understanding of the human–animal bond (i.e., relational ecology) was derived by exploring the experiences of older lesbian women who were aging with pets. While this original conception of relational ecology is informed by Bronfenbrenner’s (Reference Bronfenbrenner1979) ecological understanding of “individuals as being in a dynamic and reciprocal relationship with their environments across micro, macro, meso, and exosystems” (Putney, Reference Putney2013, p. 68), the locus was the individual. This current study’s participants’ accounts highlight instances when the multifaceted ways pets shape individual lives are also contingent upon systemic-level considerations. The health promoting potential of pets within an aging population may well be leveraged through community- and policy-level supports for pet ownership that address social justice considerations, such as the provision of affordable, pet-friendly housing for those who need it; the subsidization of veterinary care for those on reduced incomes; and creation of vibrant, age-friendly communities designed to support both pet-related needs and social inclusion. This study’s findings illustrate that despite the complexity of human–animal relationships, cross-sectoral supports for aging in place with companion animals merit further consideration at the community (i.e., meso) and policy (i.e., macro) levels.

Strengths and Limitations

The participants in this study, while purposively sampled for age and for pet-ownership, were socio-economically diverse. Recruitment of disadvantaged populations is often challenging, and disadvantaged older adults’ relationships with companion animals are not well represented within the literature. The diverse socio-economic representation in this study suggests both similarities and differences in how pets are experienced across socio-economic lines and sheds light upon systemic factors that may differentially influence these experiences. Conversely, the sample lacks ethnic diversity, thus diverging somewhat from the socio-demographic profile of older Canadian pet owners (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018). Further study is recommended to understand how various ethnic and cultural norms, including those held within Indigenous communities (Fraser-Celin & Rock, Reference Fraser-Celin and Rock2022), influence both experiences of aging in place and relationships with pets.

As both a strength and limitation of this study, all but two study participants (i.e., 86%) lived alone, which was unexpected. In Canada, approximately 30 per cent of women and 16 per cent of men 65 years and older live alone (National Seniors Council, 2017) and, prospectively, 30 per cent of those living alone may have pets (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2018). It is unclear whether this self-selection represents a flawed recruitment strategy or whether pets play a particularly instrumental role for this sub-population of older adults, piquing their interest in being involved in the study. While this sample characteristic may limit the extent to which the study findings reflect experiences of older adults in different living arrangements, it nonetheless contributes to understandings of contextual factors that may influence how pets are experienced later in life,when social isolation is increasingly prevalent (Cudjoe et al., Reference Cudjoe, Roth, Szanton, Wolff, Boyd and Thorpe2020; Menec, Newall, Mackenzie, Shooshtari, & Nowicki, Reference Menec, Newall, Mackenzie, Shooshtari and Nowicki2020).

In terms of the research setting, Calgary is internationally recognized for its progressive animal ownership bylaws (Economy and Infrastructure Committee, 2016; Rock, Reference Rock2013). Yet Calgary also features a younger-than-average population (City of Calgary, 2015), a high cost of living, and a low level of affordable housing (Kneebone & Wilkins, Reference Kneebone and Wilkins2016). Moreover, subsidized pet-friendly housing for older adults is scarce here (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; Toohey & Krahn, Reference Toohey and Krahn2018; Toohey & Rock, Reference Toohey and Rock2019). These place-specific considerations may also shape ways that our participants have experienced aging in place with pets.

Finally, this analysis represents a reflexive process. As a sole author, all analytic choices – including the understanding of salient themes – are shaped by a longtime engagement with the study of older adults and pets from a public health vantage. Personal experiences with pets over many years cannot be discounted, either, for shaping the understandings put forward in this paper. While another researcher may understand these data differently, reflexive and deep theoretical engagement with the subject matter may lead to valuable and informed insights on phenomena (Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, Reference Eakin and Mykhalovskiy2003).

Conclusion

By adopting a relational socio-ecological framework, this study draws attention to the relational influence of companion animals on aging-in-place experiences as being shaped by both individual and socio-ecological considerations. Pets were sometimes distal and other times central to challenges older adults faced while aging in place, but animal companions were also consistently credited with contributing to older adults’ quality of life in an array of different ways. Furthermore, pets were experienced within the broader context of an older individual’s particular life circumstances, which may also shape the direction of influence pets have on people’s health and well-being. This study’s findings confirm that human–animal relationships must be understood as relational. Findings also point to the value of combining multiple data sources or applying nuanced statistical approaches to help interpret the complex, relational ways that pets may influence quality of life for older adults. Enhanced cross-sectoral community and policy-level supports for aging in place with pets may have a population-level influence on health, well-being, and social justice across the socio-demographically diverse aging population.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the older adults who participated in this study for the rich, personal accounts they offered. I gratefully acknowledge Dr. Melanie Rock and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable contributions in reviewing earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grant (#MOP-130569) held by Dr. Melanie Rock. The author received additional funding for this project via a University of Calgary – Achievers in Medical Sciences Recruitment Scholarship, a CIHR Population Health Intervention Research Network (PHIRNET) Doctoral Studentship, and an Alberta Innovates Graduate Studentship (#201504).

Competing interest

None.