Introduction

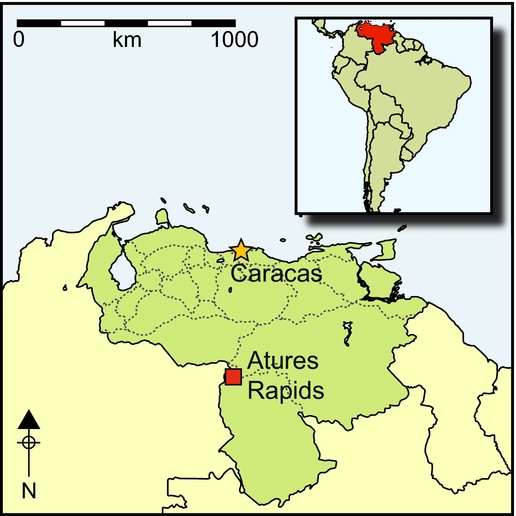

This article presents new findings of engraved rock art in the Atures Rapids of Amazonas state in Venezuela (Raudales de Atures, henceforth the Rapids), and offers the opportunity for new insights into their archaeological and ethnographic context. Pre-Columbian art has a long history of study by naturalists and scientists travelling the Orinoco, and has been the subject of archaeological research in the region for over half a century (von Humboldt Reference von Humboldt1810; Chaffanjon Reference Chaffanjon1889; Koch-Grünberg Reference Koch-Grünberg1921, Reference Koch-Grünberg2010[1907]; Cruxent Reference Cruxent1950, Reference Cruxent1953, Reference Cruxent1955; Tavera-Acosta Reference Tavera-Acosta1956; Sujo Volsky Reference Sujo Volsky1975; Scaramelli Reference Scaramelli1992; Greer Reference Greer1995; Costas Goberna et al. Reference Costas Goberna, Novoa Alvarez, Fernández, Costas Goberna and Hidalgo Cuñarro1996; Tarble de Scaramelli & Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Scaramelli, Pereira and Guapindaía2010). The Rapids are historically reported as the home of the native Adoles (del Rey Fajardo Reference del Rey Fajardo1966, Reference del Rey Fajardo1974), from which the later toponym of ‘Atures’ derives. Early missionary sources state that the Adoles were speakers of a Sáliban language, and had sizeable settlements on the islands within the Rapids (Gumilla Reference Gumilla1945[1745]; Gilij Reference Gilij1965[1782]). The Rapids are especially notable for being the last point at which the Orinoco is easily navigable by boat. The physical barrier they form, as well as their intense history of contact through the Colonial period, has led to the suggestion that they are a natural fulcrum of interaction between the prehistoric upper Negro/Amazonia, the Guianas, and the Llanos to the west (Ojer Reference Ojer1960; Gassón Reference Gassón2002).

Petroglyphs (rock engravings) of the Middle Orinoco River have featured in regional reviews for several decades (Tavera-Acosta Reference Tavera-Acosta1956; Sujo Volsky Reference Sujo Volsky1975; Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986). Yet systematic survey of engravings on a scale comparable to neighbouring regions remains unrealised here (see Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1978, Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1987; Pereira Reference Pereira, McEwan, Barreto and Neves2001; Koch-Grünberg Reference Koch-Grünberg2010[1907]; Valle Reference Valle2012). Conversely, more comprehensive studies of pre-Columbian pictographs (rock paintings) hint that the practice of rock art creation has considerable time-depth (see Scaramelli Reference Scaramelli1992; Greer Reference Greer1995; Tarble & Scaramelli Reference Tarble and Scaramelli1999). Supported by the long history of exploration along the river, the information presented here substantially broadens the focus of study beyond well-known terra firme sites, such as Cerro Pintado (see Tavera-Acosta Reference Tavera-Acosta1956). This represents a major step towards an enhanced understanding of the role of the Orinoco River in mediating the formation of pre-Conquest social networks throughout northern South America (Lathrap Reference Lathrap1970; Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Gassón Reference Gassón2002; Zucchi Reference Zucchi, Hill and Santos-Granero2002, Reference Zucchi, Pereira and Guapindaía2010). Systematic surveys undertaken along the Rapids allow us to propose that the style and content of the engraved rock art corpus implicate it in wider webs of shared indigenous conceptions of cosmology and ritual throughout the pre-Columbian and Colonial periods (Boglar Reference Boglar and Bharati1976; Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1978; Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985; Overing Reference Overing and Arnold1996). Through examination of a large corpus of riverine engravings, this study introduces significant new information to improve our understanding of the connectivity evident in pre-Columbian iconography across northern South America.

Context: the Atures Rapids within the Middle Orinoco

The Rapids are an ethnic, linguistic and cultural convergence zone. This is demonstrated by the presence of several distinct linguistic stocks that originate from elsewhere. These include several groups of Arawakan- (Curripaco, Piapoco, Baré) and Carib- (Mapoyo, Ye'kuana) speakers (Gassón Reference Gassón2002; Zucchi Reference Zucchi, Pereira and Guapindaía2010). Some of these, such as the Hiwi (Guahibo), are probably historic migrants to the study area (Zent Reference Zent1992; Tarble de Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Voss and Conlin Casella2012). The presence of Sáliba-speaking groups, such as the Piaroa (Wothuha) and the historic Adoles, may, by contrast, be of a much deeper antiquity (Zent Reference Zent1992). By the mid eighteenth century, these groups had retreated inland and the missions remained largely populated by Arawak speakers (see Gumilla Reference Gumilla1945[1745]; Gilij Reference Gilij1965[1782]). Each indigenous group will have, at different times, contributed to the overall cultural mosaic of the Middle Orinoco (Gassón Reference Gassón2002). Authors as early as Koch-Grünberg (writing in 1907) posited that the pre-Columbian artistic corpuses could indicate where interactions between diverse groups of people had taken place along the course of the river, suggesting that exchange occurred via major waterways in this vast region. Rock engravings may be included in this concept of embeddedness in broader-scale patterns, as many motifs are similar or identical to others along the Orinoco and into neighbouring areas (Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985: 378; Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986; Pereira Reference Pereira, McEwan, Barreto and Neves2001; Haviser & Strecker Reference Haviser and Strecker2006; Valle Reference Valle2012).

Archaeologists continue to debate the scale and antiquity of contact between the Llanos-Guyana-Amazonia-Caribbean region via the Orinoco and the extent to which this contact may explain the spread and endurance of ceramic traditions and ethnolinguistic groups (Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Gassón Reference Gassón2002; Zucchi Reference Zucchi, Hill and Santos-Granero2002, Reference Zucchi, Pereira and Guapindaía2010; Hornborg Reference Hornborg2005; Rostain Reference Rostain2014). Archaeological investigations on the islands in the Rapids have, for example, successfully documented the presence of several major ceramic traditions, possibly insinuating millennia of continuous occupation (Lozada Mendieta et al. Reference Lozada Mendieta, Oliver and Riris2016). Within this broader context, the Rapids are recognised as a hotspot with a high abundance and diversity of rock art between the Maipures Rapids upstream and the Meta confluence with the Orinoco. It has been proposed that this region formed a “special area” within the Orinoco-Amazon interaction zone (Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986: 126), as downstream petroglyph sites only become more abundant after the Apure confluence, while engravings are sparsely reported upstream until the Casiquiare distributary (Sujo Volsky Reference Sujo Volsky1975; Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986). The rocky Rapids also contrast with the scarcity of large islands outside the middle course of the Orinoco. Against this complex backdrop, it is imperative to understand it not only as a landscape of confluence, but also one of contestation.

Recording with computational photographic techniques

Rock art was recorded on five islands (Figure 1) and their environs, including exposed bedrock outcrops (Raudales Wayuco, Yavarivén and Zamuro) within the Rapids themselves. The latter was made possible by historically low water levels in the Orinoco during February 2015 (Figure 2). These areas were targeted based on prior knowledge (F. Scaramelli pers. comm.), and were subsequently surveyed systematically. The geographic coordinates of all encountered panels were recorded, and the panels themselves were photographed with a DSLR camera and 80mm scale. In addition to the painted and engraved rock art, several flat outcrops (lajas) bore numerous cupules and axe polishers segregated from the other engravings (Figure 3), thereby adding to the small quantity previously documented on Cotúa (Cruxent Reference Cruxent1950). Cupules were also encountered alongside petroglyphs on earthbound boulders within large, multi-period surface scatters. These cap deeply stratified (>2m) and continuous archaeological layers that span from early Ronquinoid to late Arauquinoid deposits (Lozada Mendieta et al. Reference Lozada Mendieta, Oliver and Riris2016). The largest cluster of cupules is located on the northern tip of Picure Island, and comprises 56 grooved axe polishers adjacent to 40 cupules.

Figure 1. The five main areas surveyed: 1) Cotúa and Raudal Wayuco; 2) Picure; 3) Zamuro; 4) Viboral and Raudal Zamuro; 5) Raudal Yavarivén; 6) Sardina. Points with black outlines usually inundate, while white outlined points very rarely inundate.

Figure 2. The Atures Rapids. a) View of Raudal Wayuco and Picure (background), facing south; b) Raudal Yavarivén looking west, c) overview of the Atures Rapids from mainland Venezuela (photograph by José Oliver); d) view from Picure looking north towards Cotúa.

Figure 3. Axe polishers (left) and cupules (right) recorded on Picure (80mm photographic scale on the left).

Eight principal groups of engraved rock art in the Rapids can now be defined (Table 1), the largest of which is on a north-facing outcrop on Picure Island (304m², containing at least 93 individual motifs). Here, the conspicuous size of some animal motifs (>5m2 for a single engraving, in one case) and the panel itself would render sketching prohibitively time-consuming and liable to suffer from gross recording errors. Hence, two orthomosaics were generated from low-altitude aerial photographs taken with a Phantom 2 Vision+ drone (Figures 4–5), scaled to ground-level benchmark photographs. This provided a high-resolution in situ record of this group of panels. Three motifs from Picure and a composite engraving from Raudal Yavarivén were also subjected to data capture with polynomial texture mapping (PTM) to provide an additional record of production techniques (excision, incision, pecking) for motifs of particular interest (see Duffy et al. Reference Duffy, Bryan, Earl, Beale, Pagi and Kotoula2013; Riris & Corteletti Reference Riris and Corteletti2015). The data discussed in this article is available as supplementary information in Riris et al. (Reference Riris, Oliver and Lozada Mendieta2017).

Table 1. Motif counts for the eight principal groups of engravings in the Atures Rapids.

Figure 4. Top-down aerial perspective of east panel on Picure, with interpretative overlay of main engravings. North is at the bottom of the image.

Figure 5. Oblique aerial view of western panel on Picure, with interpretative overlay of main engravings. North is at the bottom of the image.

Taphonomy and spatial organisation

The formation processes affecting the corpus, and hence the placement of engravings in relation to the river, are central to understanding it as a whole. The bedrock of the islands is composed entirely of hard Precambrian granite typical of the western Guiana shield (Gaudette et al. Reference Gaudette, Mendoza, Hurley and Fairbairn1978), forming large tabular outcrops that are capped with relatively thin Quaternary deposits of silty sand in the island interiors. Although hard and coarse-grained, the exposed geology is subject to cyclical stress through a combination of insolation, precipitation and the life cycles of epilithic algae. The latter lends many rocks a black patina (Huber & Zent Reference Huber and Zent1995; Crispim & Gaylarde Reference Crispim and Gaylarde2005). In addition to these biotic and abiotic weathering factors, almost all of the engravings found in the Rapids are inundated and exposed to varying degrees by seasonally rising and falling water levels in the Orinoco. Depending on fluctuating upstream precipitation, the relative height of the river also varies annually by up to several metres during the extremes of both seasons. Consequently, in any given year, certain panels may never be inundated, while others may never be exposed. The duration and intensity of contact that engravings have with flowing water also varies. Their orientation and local topography, therefore, strongly affect the relative degree of preservation (as observed by Williams (Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985: 339)).

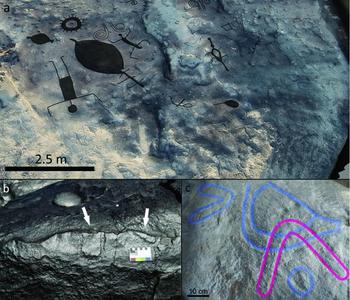

Differences were observable between engraved motifs located at comparable heights above the water (<0.5m) in the fast-flowing main channel of the Orinoco and the more meandering side channels of the Rapids. Figure 6 illustrates the low-lying panel on Picure (a) alongside motifs in Raudal Yavarivén (b–c), all of which were exposed during the peak of a drier-than-average season. The bedrock in Yavarivén is smoothed and the engravings, produced by incision and pecking, are relatively shallow. Thus, these motifs were probably severely eroded over time, and some are almost completely destroyed. Conversely, the edges of the engravings (excised, incised and pecked) around the sides of Picure are sharp and well defined. The rock in these two locations is identical. Despite the pockmarked appearance of the laja on Picure, there is no evidence of partially preserved motifs where the rock has formed small laminar fractures typical of the local geology. These two fluvial zones share stylistic content (dots, concentric circles, opposed scrolls, human figures and animal profiles), suggesting that some of the motifs were probably produced at roughly similar times, and have been exposed for comparable timescales.

Figure 6. a) Oblique view of lower panel on Picure with good preservation; b) broken motif in Raudal Yavarivén; c) extremely eroded geometric motif in Raudal Yavarivén, captured with polynomial texture mapping and traced. Pink lines overlay blue.

A parsimonious explanation for observed variability in the condition of the engravings is differential exposure to turbulent water: even under extreme drought conditions Raudal Yavarivén has high-speed flows running through portions of it. During wetter years, these flows would also cover most areas with engravings in this part of the Rapids. Engravings on the north side of Picure, however, are located in the draft of the island itself; they are subject to relatively slow flows, thereby explaining the good preservation of even shallow motifs. Similarly, engravings in Raudal Wayuco, to the immediate north-west of Picure, are placed both in the open and sequestered in rockshelters. Comparable differences can be observed within this cluster (Figure 7). The engravings recorded in the Rapids probably represent a small proportion of the original extent of the corpus, noting also that two isolated panels of recorded pictographs are located well above the Orinoco high-water mark. Making engravings in areas that are seasonally flooded is typical across the whole of northern South America; seasonal exposure may be intimately linked to the usage or symbolism of engravings (see Im Thurn Reference Im Thurn1883; Koch-Grünberg Reference Koch-Grünberg1921; Cruxent Reference Cruxent1955; Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985; Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1987; Valle Reference Valle2012). Detailed archaeological studies of riverine geomorphology are necessary to understand further the relationship between topography and surviving rock art.

Figure 7. Severely eroded concentric lozenge motifs (left) and relatively well-preserved human figures in sunken relief (right) in Raudal Wayuco. Note modern vandalism (fine incisions, possibly made with metal tools) covering the former (80mm photographic scale on the right).

Chronology and authorship

The broad timespan of putative human occupation of the Orinoco complicates the dating of this corpus. Cotúa, Zamuro and Picure Islands have extensive scatters of surface archaeology that include Barrancoid, Arauquinoid and Valloid ceramics. These represent extremities of the ceramic traditions defined in the Orinoco (Lozada Mendieta et al. Reference Lozada Mendieta, Oliver and Riris2016). The nearby site of Pozo Azul, on the right bank of the Orinoco, also has a pre-ceramic component associated with a radiometric date on charcoal of 8532–7836 cal BP at 95.4% probability (date modelled in OxCal v.4.3, using IntCal13 calibration curve, Beta-22638; Barse Reference Barse1989; Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Superimposed motifs are rare in the Rapids, making relative dating challenging. Through close reading of the pictographic record, Greer (Reference Greer1995) suggests seven successive phases for painted rock art spanning the Archaic to Colonial periods, and maps them on to major traditions in the Middle Orinoco. Although valuable on its own merit, this work lacks chemical or radiometric verification. Nor can it date petroglyphs by stylistic association. Tarble de Scaramelli and Scaramelli (Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Scaramelli, Pereira and Guapindaía2010) have tentatively correlated curvilinear motifs and the Saladoid/Barrancoid ceramic series (2500–700 BC/700 BC–AD 400, respectively), and rectilinear motifs (see Figure 7, left) and the Arauquinoid (AD 500–1500), all of which are present in the Rapids. They also note some similarities between sunken-relief animal and human motifs (see Figures 4–5) and Greer's Period 3 (Saladoid) pictographs (Tarble de Scaramelli & Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Scaramelli, Bahn, Franklin and Strecker2012).

The ethnographic record of the Middle Orinoco has figured prominently in prior discussions of its pre-Columbian artistic corpus (see Greer Reference Greer1995). Although native groups no longer produce pictographs or petroglyphs in the region, several groups historically used rockshelters with paintings as cemeteries, and attributed the creation of the paintings to their ancestors (Marcano Reference Marcano1889; Scaramelli Reference Scaramelli1992). First-hand accounts of natives making engravings were documented in the Vaupés, north-west Amazonia, by Koch-Grünberg (Reference Koch-Grünberg1921: 144). Von Humboldt (Reference von Humboldt1810) relates that engravings in Caicara were, according to native tradition, the work of ancestors drawing on young, soft rock. To interpret three extremely large horned snake motifs found in the Atures region (the Cerro Pintado example is >30m long: Figure 8), Tavera-Acosta (Reference Tavera-Acosta1956) cites a Sáliba myth describing the slaying of a monstrous serpent by the son of the creator deity and culture hero Wahari (Gumilla Reference Gumilla1945[1745]: 111–12). The Piaroa worldview strongly distinguishes between benign and dangerous phenomena, and stresses the importance of ritual knowledge for safely mediating relations with the latter (Boglar Reference Boglar and Bharati1976: 353, Reference Boglar1978; Overing Reference Overing and Arnold1996). Disease and death are caused by acting against prescribed conventions towards non-Piaroa agencies, which includes rock art (Marcano Reference Marcano1889: 393; del Rey Fajardo Reference del Rey Fajardo1974: 174; Boglar Reference Boglar1978: 84; cf. Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998). Historic attitudes towards petroglyphs in the region thus range from indifference to fear and reverence (Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986: 57–58). While some posited links are compelling, independent verification for the association of mythological accounts with specific panels and motifs remains elusive. Aspects of certain indigenous practices documented in the Middle Orinoco can nonetheless usefully inform us about the role of engravings in these societies, even if authorship cannot be ascertained.

Figure 8. Aerial photograph of monumental Cerro Pintado petroglyphs with enhanced image overlay.

Indigenous myth and sacred topography

In Piaroa cosmology, the Rapids are identified as both the birthplace of the sun and the residence of Wahari (Boglar Reference Boglar1978: 34). The cultural importance of the islands in this regard is reflected in the presence of specific motifs. Pre-Columbian engravings depicting flute players in the Upper Negro-Vaupés basins have been linked to the Yuruparí ritual complex, a set of practices and material culture that includes several types of wind instruments (Valle Reference Valle2012). The Yuruparí rite is most famously documented among Tukano and Arawak groups in western Amazonia (Koch-Grünberg Reference Koch-Grünberg1921; Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1978; Hugh-Jones Reference Hugh-Jones2016). Its northernmost expression is found among the Middle Orinoco Piaroa as the Warime ritual. The rites are seasonal and strongly male-gendered, and aim to protect the extended familial unit, ensure prolific agricultural production and re-establish the cosmological order (Mansutti Rodríguez Reference Mansutti Rodríguez2012). Central components of these performances are interpreted in a literal manner. Specifically, the sound made by one of several types of flute is understood as the voice of Wahari. Ceremonial masks worn by participants are the actual presence of sacred animals joining the rites, as opposed to merely representing masks for individuals to wear (Boglar Reference Boglar and Bharati1976: 348, Reference Boglar1978: 42; Mansutti Rodríguez Reference Mansutti Rodríguez2012).

Myths and their ritual expression are viewed as more than performative in this context, as their effects for the participants are anchored in specific articles of material culture and iconographic elements, which possess their own agencies and identities (Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998; Hugh-Jones Reference Hugh-Jones2016: 163). The motif of a flautist surrounded by other human figures from the main panel on Picure probably depicts part of a Yuruparí/Warime-linked rite (Figure 9). Performances conceivably coincided with the seasonal emergence of the engravings from the river just before the onset of the wet season, when the islands are more accessible and the manioc harvest takes place (Zent Reference Zent1992; Huber & Zent Reference Huber and Zent1995; Mansutti Rodríguez Reference Mansutti Rodríguez2012: 64; Valle Reference Valle2012). Although the majority of the Atures rock art corpus is cyclically submerged and exposed by the waters of the Orinoco (see Figure 1), the flautist panel is unique in that it can be linked to elements of recorded, extant indigenous practice. In light of the multi-period settlement site adjacent to the engravings, experiencing the rock art may be inextricably linked to the rhythm of their spatial context in the Rapids (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre2004). While stylistic similarity between the rock art of the Orinoco and Amazonia is well attested (Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985; Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986; Pereira Reference Pereira, McEwan, Barreto and Neves2001), this is the first instance where relationships can be established in terms of indigenous beliefs and local variations on shared practices (see Valle Reference Valle2012). The archaeological and iconographic records together suggest that the Rapids were, and remain, a markedly significant topographic feature (Santos-Granero Reference Santos-Granero1998), connected to symbolic patterning far beyond their immediate setting.

Figure 9. Six human figures on the western panel of Picure (see Figure 5), including a Yuruparí flautist. Note that in the Vaupés region, opposed scrolls denote masculine energy (Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1978). Inset: polynomial texture mapping detail of flautist.

Rock art was produced by both indigenous people and people of European descent throughout the Orinoco and northern South America (see Im Thurn Reference Im Thurn1883; Chaffanjon Reference Chaffanjon1889; Koch-Grünberg Reference Koch-Grünberg2010[1907]; Scaramelli Reference Scaramelli1992; Tarble de Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Voss and Conlin Casella2012). Close to the right riverbank, Raudal Zamuro hosts a large cross motif engraved in the centre of a cluster of seven pre-Columbian petroglyphs (Figure 10a). This is one of several non-indigenous motifs recorded in the Rapids (Figure 10b–c). The area with the cross motif is easily accessible on foot during the dry season. As with rock art, powerful abilities were attributed to the missionaries by the natives. Historically, Jesuit fathers in the Middle Orinoco demonstrated their power to the mission populations whenever possible, in particular under perceived threat from the supernatural. In one notable account from the Tabaje mission between the Meta and the Rapids, blessings were said to be administered by the priest to protect against the spectre of a recently deceased member of the group (del Rey Fajardo Reference del Rey Fajardo1966: 151). In another example pertaining directly to rock art, in 1691, missionaries visited a Sáliba “oracle” in the Atures region, which took the form of images located high on a hillside:

When our missionaries came to this place Satan was silenced at once, and the Devil disappeared from there, the diabolical responses ceasing henceforth with the astonishment and admiration of the pagans [. . .] whom before had treated with the demon so easily. With this the infidels knew the power of God, and the force and efficacy of the ministries against the powers of Hell (Rivero Reference Rivero1883: 284, translation by P.R.).

Figure 10. a) Colonial cross motif inserted among a group of indigenous motifs in Raudal Zamuro; b) oblique view of graffiti ‘M’ on an animal in profile on Picure (see Figure 4); c) early modern inscription in Raudal Wayuco.

The cross motif fits within the historical trajectory of colonialism in the Orinoco from the seventeenth century onwards, and reveals the engagement of Christian individuals with the indigenous meanings attached to significant landscape features, such as the Rapids and Cerro Pintado. The insertion of the cross among native motifs is testament to the acknowledgement and endurance of native memories that surrounded rock art at this time. The need to contest these meanings materially was crucial during the evangelisation of the region. This directly parallels processes of spiritual exchange that have been documented through rock art elsewhere in the frontiers of early colonial America (see Recalde & González Navarro Reference Recalde and González Navarro2015; Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Samson, Nieves, Lace, Caamaño-Dones, Cartwright, Kambesis and del Olmo Frese2016), to which the Orinoco may now be compared.

Conclusion

Examining the corpus in light of the available archaeological and ethnographic information places the Rapids rock carvings within a long trajectory of interaction along the Orinoco watershed (Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986; Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Gassón Reference Gassón2002). Although no rock art in the region has been directly dated, there are clear links between its content and culturally significant indigenous beliefs across the pre-Columbian and Colonial periods. Consequently, this multifaceted corpus can be viewed as a local manifestation of a constellation of broadly comparable indigenous practices that spanned the Orinoco interaction sphere. This shared tradition of symbolic expression can be found in the arc bounded by the Vaupés River, the Guianas and the upper Negro (Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985; Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986; Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1987; Valle Reference Valle2012). Certain common motifs, such as opposed scrolls, may have had context-specific meanings lost to time (cf. Reichel-Dolmatoff Reference Reichel-Dolmatoff1978; Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985). Their similarity and recurrence along and within waterways, however, suggest that the people responsible for their production shared enduring norms on how to make use of engraved iconography to imbue the landscape with meaning, well into the Colonial period.

The diversity of motifs in the sample underscores the centrality of the Middle Orinoco landscape in mediating cultural contact between several regions. While painted rock art is principally associated with relatively remote funerary sites (see Scaramelli Reference Scaramelli1992; Greer Reference Greer1995), engraved art is embedded in the everyday lived experience of travel and habitation in the Middle Orinoco River, including its rhythmic rising and falling, and its strong associations with important aquatic resources (Williams Reference Williams, Wendell and Close1985: 380). With archaeological confirmation of long-term settlement on the islands (see Cruxent Reference Cruxent1950; Lozada Mendieta et al. Reference Lozada Mendieta, Oliver and Riris2016), the corpus presented above can be placed within a complex social terrain that was inhabited by several different ethnolinguistic groups within an important zone of contact.

Close to the Rapids, previously documented sites such as Cerro Pintado and Cerro Paloma (left bank, opposite the Rapids) have some of the largest petroglyphs currently known in northern South America. The production of engravings on this monumental scale is a phenomenon apparently unique to the Middle Orinoco (see Tavera-Acosta Reference Tavera-Acosta1956)—these motifs share stylistic elements with the Rapids. Future research will focus on linking the Rapids rock art to neighbouring regions through analytically explicit techniques (e.g. locational modelling and formal network analysis). Although the study area stands out in many respects, the corpus is clearly embedded in a broader supra-regional aesthetic tradition. It is undoubtedly the work of multiple authors working in significantly different cultural milieux and conditions. This necessitates clearer definitions of the many overlapping elements and characteristics discussed here, which will provide stronger models of the social roles played by rock art over time, across this vast region.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under a Leverhulme Trust Research Grant (RPG-2014-234) obtained by project PI José Oliver. His help in the preparation of this paper is gratefully acknowledged, particularly regarding access to J.M. Cruxent's unpublished diaries. The fieldwork in Venezuela was made possible by support from the Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas, and from Juan Carlos García in Puerto Ayacucho. Tom Owen is also thanked for his insightful comments. Any errors are the author's responsibility.