3.1 What Happened to Villas?

While unique personal, temporal, and economic circumstances dictated the decline of individual villas, by the sixth century CE, villas as a Roman-style settlement had disappeared from the landscapes of Italy and the northern and western provinces. While there were general changes specific to certain geographic regions throughout late antiquity, every site underwent changes in different ways. These differences have made studies on the ‘end of the villa’ challenging. In addition, there was not a fixed sequence of decline-abandonment-re-occupation, because while some have churches constructed on the villa sites in the fourth–fifth centuries, others underwent ‘productive’ reoccupations, and others still went into decline, were abandoned, and then destroyed under catastrophic circumstances.1

While there is a temptation to find standardizations in the decline of villas, the reality was that some villas were partially abandoned, entirely or partially transformed, destroyed in a single incident, or abandoned and left untouched. At present, as noted in Chapter 1, the type of on-site recycling that will be discussed further in the next chapter has been recognized at 5–10 percent of sites throughout Italy and the western provinces. This figure will undoubtedly increase as we gain a better understanding of the actual processes of decline of individual sites and excavate post-Roman phases with more care in future. Nonetheless, this figure may also represent the variation in the ‘end of villas,’ and the fact that there may have needed to have been specific motivations for the dismantling and reprocessing of villa materials, the conditions around which will be discussed further in Chapters 7 and 8. It is important to note, however, that while only a small sample of villas show evidence of on-site recycling, nearly all villas were subjected to material removal and salvage in their post-Roman phases.

3.1.1 State of Scholarship on the ‘End of the Villa’

Previous work on the ‘end of the villa’ has identified two general and concurrent changes to villas in the western Empire from the third century CE onwards. These changes were related to the function of villas and the economic circumstances of the owners. The first of these changes was a monumentalization of architecture, while the second was a higher frequency of transformation and abandonment.2

Villas typically underwent either monumentalization or abandonment/transformation in the third–fourth centuries. Many villas that continued to be used after the third century, and those that were newly built during this period, took on a different architectural style to those villas built in the first–second centuries. The later Roman villas often, if not always, included large bath suites and many apsidal features, including large apsidal halls, as can be seen at Masseria Ciccotti, in Basilicata, or at Piazza Armerina, in Sicily.3 New decorative elements were also part of the reconstructions and included elaborate, sometimes figural mosaics and opus sectile paving. This trend was not restricted to Italy but occurred throughout the western provinces.4 Some scholars have linked these rebuilding activities to the political and economic stability in the Empire following the so-called third-century crisis.5 However, many of the reconstructions of villas can be dated to the fourth and fifth centuries. Thus, while there were some villas that went out of use in the late second to third centuries, possibly due to diminishing agricultural exports, others particularly in southern Italy, Spain and France continued to be used and were remodelled in the decades and centuries that followed.6 The addition of large audience halls, dining, and bathing facilities could have meant that more entertaining occurred in the later style villas. There may have also been an increase in goverance that went on in villas during this period, with local aristocrats who might have previously conducted their business in cities now doing so from their rural homes.7 Regardless of the function, it is clear that at least among a segment of the elite class, there was an increase in wealth and desire to direct funds to the reconstruction of their villas in the third–fourth century.

The other change to Roman villas from the third century onwards was a higher frequency in change of use and periodic or final abandonment. While this began in the late second–third century, at villas such as Settefinestre, the majority of the ‘late Roman’ style villas, for example, Montmaurin or Carranque, then themselves succumbed to abandonment in the fifth–sixth centuries.8 This appears to have been the general case across the former Empire. In Spain, A. Chavarría Arnau has noted a rise in ‘productive transformations’ of villas and abandonment of more luxurious functions from the third century onwards in the east and south, and from the fifth century in the central plateau and western regions.9 Similar patterns have been noted in the northern provinces as well.10 Survey results from the Tiber Valley have demonstrated the dramatic reduction in rural settlements north of Rome in the fifth century based on pottery scatters.11 In addition to survey, the process of decline has been observed during excavation at individual villa sites as a lack of maintenance and irregular alterations of the structure, including the insertion of partition and wooden walls, huts, workshops, and the placement of burials inside the villa walls.12 In some cases, ovens or burials were inserted into audience halls and mosaic floors were cut through by hearths or wooden features.13 At other sites, evidence of large-scale destruction by fire was present.14

The insertion of utilitarian features or burials and the general disregard for monumental architecture at villas has puzzled many scholars.15 This phase has been interpreted by some as an abandonment of the villa site by the former owner, and reoccupation by ‘squatters’ or transients.16 This perspective was challenged by T. Lewit who believed that the frequency of this practice was too high to simply have been the work of people taking advantage of empty villas.17 Lewit asks: ‘The same kind of occupation appears consistently at site after site in Gaul, Britain, Hispania and Italy. How many squatters were there?’18 N. Christie has also suggested that villas might not have been abandoned and reoccupied, but that the owners or their descendants might have had a change in economic circumstances which was reflected in a change in the functions of their villas.19 It is clear that the previous interpretation of abandonment followed haphazard reoccupation or reuse is an outdated and simplified model which many scholars have now rejected.20

One of the problems with the abandonment-transient re-occupation model is that some villa sites show more formal re-occupation in the post-villa phases in the form of churches or small village settlements.21 Some villas, for example, became churches, initially between the fifth and the eighth centuries. The mechanisms of this acquisition of formerly private land have been much debated.22 There appears to have been a strong link between the residences of the elite and the location of rural churches in the late Roman period, suggesting there was an active transfer of property with the conversion of the elite to Christianity.

Other villas that were not subjected to church construction either had smaller semi-permanent settlements in the Early Medieval period (seventh–eighth centuries), like at Faragola, or were never re-occupied after their phase of decline. Those with Early Medieval, non-church settlements have only begun to be explored properly through excavation.23 In many cases, the archaeological features that characterized the decline of the villas and these Early Medieval settlements are thought to be the same occupation; however, in most cases, a more nuanced interpretation needs to be taken.24

This present study comes at a time when attitudes to ‘the end of the villa’ have begun to change. While much general thematic work has been undertaken through re-examining previously excavated villas, some scholars are now looking more intensively at the final phases of individual villas they are excavating. One excellent example was undertaken by G. Volpe’s team at the villa of Faragola, located in Puglia in the valley west of Ascoli Satriano, and the work being done by the team led by M. Cavalieri at the villa of Aiano-Torraccia di Chiusi in Tuscany.25 Investigations into the ‘end’ of Faragola revealed a complex sequence of decline (end of the sixth century), possible abandonment (early seventh century), temporary usage for recycling (seventh century), re-occupation with increased craft activities and continued recycling (seventh–eighth century), and final abandonment (end of the eighth century). Excavations at Faragola remind us of the complexity of the issue of ‘abandonment’ and demonstrates that more careful assessments could be profitably undertaken on the final and post-Roman phases at villas.

3.2 Chronology and Patterns of Decline and Material Salvage

The removal and recycling of materials from villas has a long chronology and was not only an activity that occurred in the late Roman period. In fact, as early as the second century CE, there was evidence of the systematic removal of materials from villas in central Italy. The practice of materials salvage from these properties goes on until the Middle Ages (thirteenth century and beyond). The circumstances of ownership and local building activities in various periods dictate when and how materials were salvaged from villas. It is also worth noting that in many cases we cannot know when materials were removed from villas, but that as circumstances of these sites and the surrounding countryside changed throughout the later and post-Roman periods, materials would have been desired and salvaged for new projects and sale. Circumstances of ownership of most villa sites are not known for the post-Roman phases, and thus it is impossible to say whether sites were stripped by their owners or someone else. But in many cases, the organized nature of the materials removal and reprocessing suggests an organized workforce, either acting under instruction of the owner or a group working under their own initiative. The ownership of villa sites after the Roman period will be discussed further in the last chapter.

3.2.1 Mid- to Late Imperial Period (Second–Fourth Centuries CE)

The earliest evidence for systematic salvage and recycling of villa materials can be seen at two types of sites: those which go out of use entirely in this mid- to late imperial period and those which are reconstructed on the same site but on new foundations.26 As construction projects more generally across the Empire thrived in this period, it can be assumed that many of the materials taken from decommissioned villas would have supported this industry.

In Italy, some villas from the late Republican and early imperial periods were abandoned in the second and third centuries to facilitate new constructions on site. For instance, the early imperial villa at San Felice was systematically dismantled to construct a later villa some 200 m away on the same property. Limestone wall blocks were dismantled – some used to build the later villa and some put into a lime kiln to produce lime for mortar and possibly for agriculture. The iron and bronze architectural components were also reprocessed in a large hearth structure cut through one of the floors of the former villa.27 At San Giovanni in Tornareccio in the Abruzzo region of Italy a lime kiln was also built in the second/third century between the older villa and new third century structures. Presumably this lime kiln was used to facilitate the construction of the third century structures, using the old limestone wall blocks. The lime kiln was almost entirely demolished, either in antiquity or after, and it is therefore impossible to know how long it was in operation. The presence of lime kilns supporting limestone salvage and reprocessing reflects the rural nature of this production activity throughout the Roman period.

Because there was active construction both in the rural and urban environments in the late antique period, for villas that went out of use entirely prior to the third century, much of what was salvaged was probably transported off site. The materials that were in highest demand in this period were limestones for lime to make mortar and concrete, wall blocks and cut stone for construction, and marble paving stones. This is evident from the numerous late antique urban and rural examples of reuse of earlier imperial marbles. At Faragola, for example, the grand fifth century cenatio was paved with reused marbles, including fragments of inscriptions. As is evident from the San Felice example, on-site reconstruction must have also salvaged and reused timber and metals as these materials were costly to import fresh to site.

In the western provinces (Hispania, Gallia, Germania, and Britannia), we see a slightly different pattern in this period. A. Chavarría has identified the two distinct changes to villas in this period in Spain28 – firstly there were those that began a process of monumentalization in the late third century (e.g. La Olmeda, Cuevas de Storia, Almenara de Adaja, Aguilafuenta, Carranque, El Ruedo), as occurred in Italy and France, but also those that underwent ‘productive transformations’. This second category tended to be smaller villa sites that evidently did not go out of use as some did in Italy but had agricultural production fixtures (tanks, presses, plaster floors) installed in former residential rooms. This included predominantly oil, wine, and fish processing villas. Chavarría has theorized that these sites actually became embedded within larger landholdings of the elite at this time.29 Similarly, P. Van Ossel and P. Ouzoulias surmised that the previously argued abandonment of villa landscapes from the fourth century in the northern parts of the western provinces, in fact, represented an archaeological visibility and prioritization problem.30 Reduced and more scattered forms of settlement continued at villa sites and were still dedicated to agricultural production, even if some of the more luxurious features of villas were lost.

3.2.2 Late Antique (Fourth–Sixth Centuries CE)

The transformation and abandonment of villa sites certainly accelerated during the late antique period. By the sixth century, most villas had been partially or fully abandoned as luxury private dwellings. Sometimes villa sites were converted to ecclesiastical centres, but that also did not guarantee longevity beyond the sixth century. In the fourth through sixth century, there was increased productive and burial activity at sites as well.

In most cases, certain sectors or specific materials were subjected to salvage operations when villas shifted from primarily residential structures to other functions or abandonment. This is usually evident in the excavated stratigraphy. For instance, at the villa site of Gerace in Sicily, all the materials from the large bath complex were removed before the site was abandoned. Traces in the mortar backing of the tubuli that heated one of the plunge pools at the large bath complex were clearly visible during the excavation.31 It was not only the ‘high status’ materials that were removed here but the specialist ceramic materials as well. At L’Horta Vella in Spain the baths were stripped of their paving, the undesired materials from the villa were dumped into the stripped baths, and pools backfilled in the fifth century. This material clearance phase appeared to make way for oil presses.32 In other cases, it is difficult to ascertain when materials were removed, particularly from the superstructure, without a final destruction event, like a fire, landslide, or earthquake to seal the material salvage phase.

Material salvage during these centuries supported the construction/reconstruction industries, ‘raw’ materials trade, and small-scale craft activities. The sometimes disorganized legislative and cultural nature of cities in this period, including the lack of regulation of craft activities in the western part of the Empire, meant that there may have been more opportunities for small-scale initiative and enterprise. Many of the craftspeople and workers dismantling villas may have been part of travelling guilds.

We see the highest frequency of multi-material salvage in this period. All materials that were useful for the individual markets around the villas were salvaged, but of course, this was not consistent across the different regions. For instance, at São Cucufate in Portugal, the walls of the villa were made of courses of brick and local igneous rocks, and most of the villa remained standing beyond its abandonment in the fifth century, suggesting that there was no demand for these materials.33 The presence of organized salvage activities and the apparent market for the materials probably represent personal enterprise within a still functional trade economy.

3.2.3 Early Medieval (Sixth–Ninth Centuries CE)

In the early medieval period, the very last of the late antique villas were then abandoned and subjected to materials salvage. This was predominantly the case in southern France (Séviac, Saint-Émilion – Le Palat), southern and eastern Spain (El Ruedo, Torre Llauder, Torre de Palma), as well as sites like San Giovanni di Ruoti and Faragola in southern Italy, and a handful of others (Aiano-Torraccia di Chiusi among them) which had very late villa occupations. Salvage and recycling at these sites again encompassed all three motivations noted (reconstruction, ‘raw’ materials, and small craft), but more frequently, salvage appears to have been for the production of new objects (small craft). Furthermore, most of the activity appears to occur in the sixth to early seventh centuries, rather than in the second half of this period, by which stage villa sites had either been completely abandoned, had new hut settlements, were being used for burials without churches present, or had already been converted into monastic or ecclesiastical sites in earlier phases.

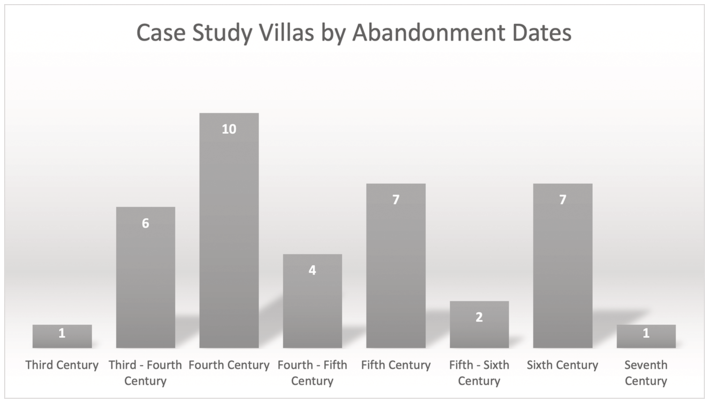

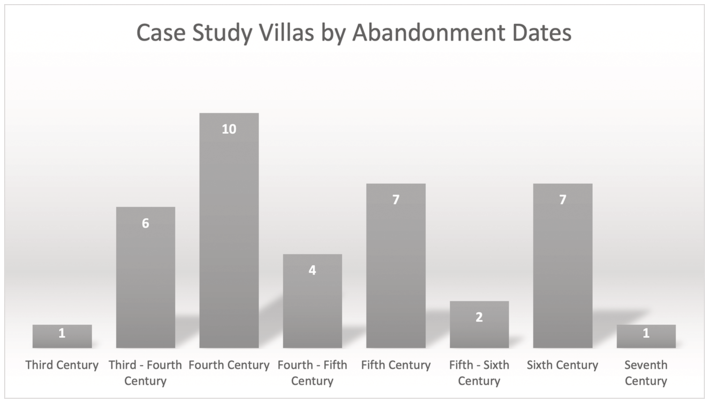

Chart 3.1 End dates for the case study villas (see Table 1.1) which then experience material salvage and recycling. Most dates are reported with reference to half or quarter centuries.

3.2.4 Medieval (Ninth–Fifteenth Centuries CE)

After what seems to be a gap in material salvage and recycling, there is renewed evidence from the medieval period of villa dismantling. For example, at the site of Villa Magna in Lazio, the limestone blocks from the imperial villa were dismantled and burnt in the lime kiln to facilitate the reconstruction of the tenth-century church. The Villa dei Quintili in Rome underwent several phases of materials salvage, up to the fifteenth–sixteenth century phase when a lime kiln was installed in the central area of the villa.34 Furthermore, at the site of San Vincenzo al Volturno, the glass workshop of the eighth–ninth century appears to have been recycling Roman glass possibly taken from a single Roman building – perhaps another imperial building in Rome but also perhaps from a large villa property on the scale of Villa Magna or Piazza Armerina, implying a site formerly owned by the imperial family or a high-ranking official.35 It is possible that the imperial ownership of some sites delayed their material salvage and recycling, adding further proof to the idea that owner permission was required to dismantle, salvage, and recycle villa materials.

At San Vincenzo al Volturno, the two workshops datable to the eighth to ninth century were associated with the ecclesiastical complex. The large-scale glass production is an example of a workshop that could have made fine-glass vessels to serve the residents and guests at the monastery and also possibly for external sale as a method to generate profit.36 Despite the fact that there was a villa on the site of San Vincenzo before the construction of the church, and it is very likely that the materials of the villa were used to construct the monastery, there is no secure archaeological evidence for this.

The location of workshops at Pieve di Manerba, next to and under the Medieval church, suggest they were also used to facilitate construction of the church. There is, however, a chronological problem at this site: the workshops have been dated to the fourth to seventh centuries CE, but the church was not constructed until the eleventh century. These workshops could not have been directly related to the eleventh century church, suggesting there might have been an early, yet undiscovered, church on site.37 Such may have been the case at many sites where a medieval church has been preserved over late antique foundations, of which little remains.

The villa dismantling that occurred in this period appears to have facilitated church construction and monastery life and perhaps involved the accessing of semi-intact villa structures for their materials. This trend continued into the early modern period, but it is fairly safe to assume that most materials from rural sites that had not been affected by a natural disaster, such as those affected by volcanic activity on the slopes of Vesuvius, would have been dismantled and most of their valuable and reusable architecture removed by the medieval period.38 This explains why it is rare to find walls that are more than several feet high and why metals in large quantities, in particular, are missing from sites.

3.3 Processes of Abandonment

Very little is known about the circumstances of abandonment at individual villas, as few written records exist of why and how owners left their properties. Even when villa lands were transferred to the Church, there was quite often no preserved record of this initial transaction, nor of the processes of transformation.39 During use-phases, the main residential sectors of villas were unlike urban domestic structures owing to the high social status of the owners and demographics of the households. For instance, many villas may not have been fully occupied all year long – some may have been seasonally visited by owners and workers, while others may have had workers who were present there all year long, with more occasional visits by their owners. This is clear from imperial texts, which document the visits of aristocratic owners to their country estates.40 Thus, the processes of villa abandonment need to be considered differently to that of Roman towns or cities. Aside from invasion, in towns and cities, depopulation and emigration caused abandonment and reconfiguration slowly, and in the rural environment, these processes may have been drawn out over even longer timescales.41 In most cases, the abandonment of villas appeared intentional and non-violent, and materials were systematically removed, if not by the owners, then by workers, with or without permission, or others who came after.42

It is also critical to note that by the third and fourth centuries CE, many of the wealthiest landowners owned multiple properties across the Empire. Thus, the abandonment of some sites may have been a process of individual ‘downsizing’ or amalgamation due to economic and political pressures on the owners themselves.43 Villas in late antiquity, specifically, were affected by the contraction of the economy across the Mediterranean, invading groups who challenged and upset political and cultural boundaries and trade networks.44 The texts which mention the infamous agri deserti refer mainly to properties in the most densely occupied and productive areas of Campania and North Africa, and Christie has noted that the state intervention to counter agri deserti was an effort to restart production not in deserted landscapes per se, but un-cultivated ones.45 The un-cultivated lands were perhaps only a result of multi-property landowners trying to amalgamate their productive outputs at a handful of larger sites. At sites where the villa residential buildings were abandoned, we must be cautious not to assume that the lands of the villa were also abandoned. Pollen analysis suggests that lands were not abandoned in many cases after the end of imperial rule in the West but that landscapes changed from intensively farmed with crop specialization to more mixed agriculture serving concentrated markets.46

It is important to distinguish between property owners and workers on the land. Just because the former left or sold their sites does not necessarily imply that the latter were forced to leave. Indeed, if an owner’s presence at the site became less and less frequent, the lands may have continued to be worked or occupied for decades, provided there was an economic or legal rationale, or subsistence benefit to doing so. The notion of an empty landscape in the villa context is usually related to the discovery of phases of unoccupied residential structures, where it appears that human habitation has disappeared.47 However, villa estates housed other classes of people in different forms of settlement which left fewer archaeological traces. The investigation of the estate community beyond the residential villa and structural agricultural equipment, such as wine presses, are rarely prioritized in archaeological excavation for practical and historiographic reasons.

That said, the extent of human presence on villa sites beyond the walls of the residential structure would have depended on the nature of the site. Villas which supplied the imperial fisc would have been much more carefully monitored and controlled than smaller farms which may have only provided a small profit for owners.48 The scale of the site also mattered – on some sites there may have been an owner, free and/or enslaved site managers, and workers, whereas on larger sites, there may have been a greater hierarchy of workers with different statuses. Thus, the variability in villa estate ownership and management was significant, and therefore, the processes of abandonment were equally varied. Indeed, in some cases, those undertaking the material salvage and reprocessing may have been extant villa site workers. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

With these caveats in mind, and returning to a focus on the residential villa structures where the archaeology obviously points to abandonment, we can posit three processes of abandonment of the residential villa structures:

1 Villa abandonment ahead of site-use transformation. This can be interpreted as infrequent use of a site or abandonment for a period before a new form of settlement was established (incl. church construction).

2 Infrequent use of a site or abandonment preceded or followed by a catastrophic event.

3 Villa abandonment without site abandonment. In this case, there was continuous occupation of a site which was then converted into a Christian church or monastery.

Archaeologically, process #1 can be identified by the build-up of debris, both natural and from the decaying structure inside the rooms, prior to new forms of settlement or the obvious absence of roof or walls, possibly due to the collapse of structures in the abandonment phase. This need not be the same across the site – indeed in many cases, portions of a villa would be initially left, while others subjected to material salvage, prior to other post-villa events, such as collapse, construction of huts or other temporary structures, or use of a site for burials. C. M. Cameron notes that after the initial clearance of personal and portable materials from a site, if the materials that remain are deemed to be potential resources (like recyclate), these too will disappear gradually over time.49 It is precisely for this reason that pinpointing when valuable materials were removed from the standing structure of an abandoned villa is extremely challenging (discussed further in the next section). Process #2 is probably the easiest to identify, as this was marked by traces of fire or destruction either with or without the build-up of debris before this final event. Process #3 is difficult to identify with certainty using archaeology, as it may not contain any obvious traces of abandonment or continued use prior to transformation.

3.4 Systematic Removal of Architecture and Movables

The way in which architecture and movable objects were removed from villas was determined by their destination. If they were going to be reused, then fragile materials, like glass, would have to be stored and shipped carefully to avoid breakage. Whereas if the materials were going to be recycled off site, they could either50

Determining whether movable items were systematically removed post-abandonment is almost impossible because they did not leave traces in the same way as larger features and architecture. But generally, when people leave landscapes intentionally and of their free will, they take their personal and movable possessions with them.51 Archaeologically, however, this means that we must argue that personal items and movable décor were removed from an absence of evidence. In particular, if there were no metal or glass objects found during excavation of a villa site, we assume they have been removed or recycled.

The systematic removal of architectural materials can be detected archaeologically in two ways: (1) by identifying an absence of expected collapsed building debris and (2) by identifying physical traces of materials removal. The first method is problematic, however, because there are several reasons why architectural material may not have been recovered during an excavation, including natural decomposition of organics, ploughing activity, and erosion. Furthermore, if the material was intentionally removed, this could have occurred during any subsequent period between antiquity and the present day, though depending on the site, this should be recognizable stratigraphically. Thus, an ideal sequence for reconstructing systematic removal within a particular period would be the removal of material followed by another phase of occupation with dating evidence.

An examination of the available evidence from villas gives an indication of the typical archaeological finds relating to systematic removal. Usually in excavation publications, only certain types of materials are listed or identified as missing from the archaeological record. For example, excavators often weigh or classify roof tiles but not stone wall blocks or windows. Furthermore, this has only been done on sites where the research question has included assessing construction materials. Metals, wood, and wall plaster are not normally considered because it is assumed that they would have been removed or were not preserved archaeologically.

The following sections will present the evidence for the systematic removal of architectural and domestic materials at case study villa sites. Both methods for detecting systematic removal (absence of material and physical traces of removal) will be used. It must be emphasized, however, that there is variability in the nature and quality of the evidence, and that only one method might be applicable to a particular site, while at others, both methods of detection can be applied.

3.4.1 Evidence of Furnishing Removal

Furniture and other portable items were not strictly speaking part of the architectural fabric of a Roman villa. However, these were regularly reused and recycled, as evidenced by reused and inherited collections of sculpture villas in the western provinces in late antiquity. Many furnishings must have been removed by owners when they left a property. However, if an owner left in haste or with the intention of returning, the first thing that would have been removed from a dwelling by demolition crews would have been the valuable furnishings.52 By definition, movable objects were the easiest to remove, resell, or reprocess because they could be easily transported. There is increasing evidence for second-hand markets in antiquity for reusable goods, and certainly metals, glass, limestone, and wood products could have been reprocessed and recycled.53

As villas were luxury dwellings, some of the furnishings were costly and of high quality. In addition to common- and cooking-ware pottery, fragments of fine wares and glass vessels are usually noted at villa excavations. In addition, some villa owners may have possessed silver plates and other fine metal objects such as bronze and marble statuary, bronze light fixtures, and silver or bronze mirrors. More common furnishings would have included wooden tables, chairs, and beds.

In addition to household items, there were large quantities of materials on the wider villa estates for agricultural processing and maintenance and repair of farming equipment. These include items like chisels, hammers, axes, and saws. Whether or not these tools would have been stored or moved to the villa building, rather than kept in outbuildings, depended on the size, type, and location of a site. For instance, the use of outbuildings in imperial villas in Gaul and Germania is well studied. This phenomenon of multiple outbuildings which surround the luxury villa building is less well understood for Italy, where excavations have traditionally focussed on the residential structures. At Villa Magna in Lazio, however, some of these outbuildings have been studied, including what appears to have been estate worker barracks.54 Also at Villa Magna, the 38 dolia in the winery were systematically removed before final abandonment in the late third century CE.55

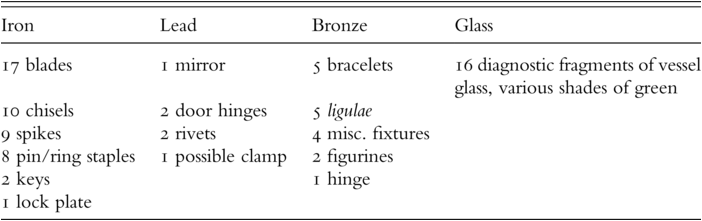

At San Giovanni di Ruoti many of the movables found in the villa were tools related to agricultural activities, such as blades for harvesting wheat or cutting wood.56 There were no tools found associated with metalworking or construction, suggesting that those who might have salvaged architectural materials would have brought their own tools with them and taken them away once the work was completed, or removed ones they found on site. As with most sites, the other movables found at San Giovanni included small items for food preparation, toilet items, small jewellery pieces, terracotta loom weights and associated weaving objects, and some equestrian related objects.57

Table 3.1 summarizes the small finds that were more than 5 cm in length or diameter and demonstrates that the only material preserved in significant amounts was iron. However, without the weight of these materials provided, it is difficult to quantify how significant this might have been. Either objects were removed from the site when the owners left, were recycled, or have been broken into many small fragments that were not recorded in the catalogue.

Table 3.1. Summary of small finds, over 5 cm long/in diameter, San Giovanni di Ruoti (based on ‘Catalogue’ Simpson 2007).

| Iron | Lead | Bronze | Glass |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 blades | 1 mirror | 5 bracelets | 16 diagnostic fragments of vessel glass, various shades of green |

| 10 chisels | 2 door hinges | 5 ligulae | |

| 9 spikes | 2 rivets | 4 misc. fixtures | |

| 8 pin/ring staples | 1 possible clamp | 2 figurines | |

| 2 keys | 1 hinge | ||

| 1 lock plate |

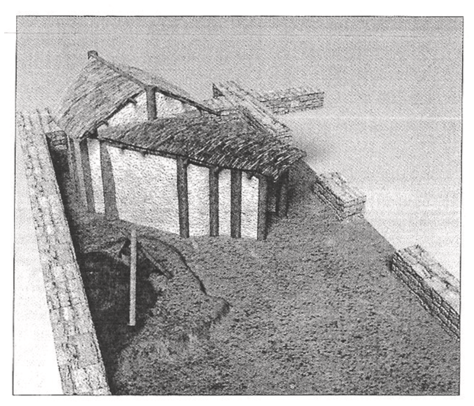

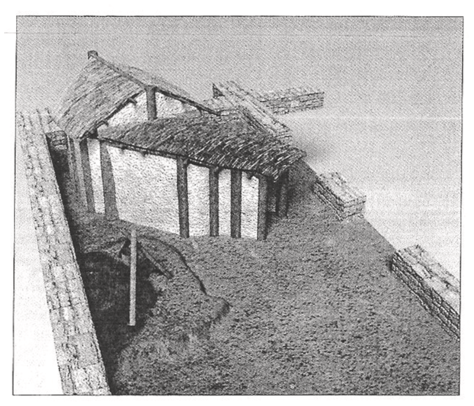

3.4.2 Evidence of Roof Removal

The roof tiles, wooden beams, nails, and other metal clamps would have provided recyclable materials for other construction projects or, in the case of wood, for more general use as fuel. But the state of the roof would have dictated whether these materials could have been reused or recycled. In many cases, there was evidence of a partial or complete roof collapse before the final phase of occupation. In the later sixth and seventh century phase at Faragola, there were hut structures built inside the former walls of the villa in Rooms 4 and 7.58 This is evident from post holes and beaten earth surfaces around the post holes. The huts would have been constructed of wood, with mud-brick walls and thatched roofs.59 It is likely that by the time these huts were built, after the phase of materials removal in the sixth century, at least the roofs of the villa had been removed or were missing, otherwise there would not have been a need to build huts inside the villa walls. In the reconstruction of these huts, Volpe imagines that the walls of the villa would also have been at least partially collapsed or dismantled (Figure 3.1). It is possible that the materials used to build these huts were taken from any remaining material on site, such as rubble from the wall or wooden posts.

3.1. Reconstruction of the huts inside room 7 at Faragola, Italy (Volpe, De Felice, Turchiano Reference Volpe, De Felice, Turchiano, Volpe and Turchiano2005a: figure 35).

If a villa roof had collapsed, most of the tiles would have smashed. Broken tile, however, was reused in the fill of floor layers, foundations, and walls. Any roof tiles still intact could have been reused as tiles. There is indirect evidence for the systematic removal of the roof at Torre degli Imbrici. As the name suggests, a medieval tower located 400 m from the site of the late Roman villa was constructed using the tiles and probably stone from the villa. The construction date of the tower is unknown; however, Roman materials are still visible in the fabric of the structure today. The roof tiles were reclaimed from the villa site, and some were likely intact, suggesting that either they had not broken when the villa roof collapsed or that the roof was systematically dismantled.

There were not, however, any opportunities to reprocess tiles, as they were ceramic and could not be reformed. But broken brick and tiles could have been used as fill in new constructions, and indeed they were also used to build some of the reprocessing installations that will be examined in Chapter 4. An unusually small number of roof tiles recovered on excavation has been used as the first indicator of roof removal. At San Giovanni, in the destruction rubble of Room 31, there was a low count of imbrices, suggesting that the roof of this room was removed before the midden built up inside.60 Conversely, at Linguella, the number of roof tiles recovered on excavation indicates that either the roof collapsed or it was intentionally destroyed, and the tiles were of no use to those reclaiming other building materials. After the roof was destroyed, instead of being cleaned up, temporary hut structures were built on top of the remaining tiles. In Room 1, post holes in the floor level over the roof collapse debris demonstrated the presence of these huts which would have been partially supported by the villa walls.61 Obviously, the material from the roof was of no interest to these inhabitants, but they did establish residences in the villa and used the standing walls, some of the stones, tiles, and likely the wood, to build their huts. Similarly, those engaged in the systematic removal of material at Settefinestre had no further use for roof tiles but obviously took the time to organize them by placing them in several designated spaces. Rooms 5 and 69 were filled with tiles and then topped with a pickaxe, which it was thought to have been used for the removal of the architectural materials.62 At the villa at Fishbourne in England, it was evident from a lack of rafter nails and intact roof tiles that the roof and timber framing of the Aisled Hall was carefully dismantled ahead of a catastrophic fire.63 Only broken tiles were left in this space, and not a sufficient amount to cover the roof. All usable tiles were evidently removed from the site prior to the fire that stratigraphically sealed this phase.

Any small pieces of wood removed from roofs would certainly have been used as fuel, while larger beams could have been reused in new construction. If a roof was still intact, the method of systematic removal would have depended on the specific demand for the materials. If tiles were of no use to those undertaking the destruction, then sledgehammers could have been used. If, however, roof tiles were desired intact, then they would have had to have been removed systematically, from the top, to ensure that they did not break, presumably by using ladders if not a system of scaffolding. The removal and use of wood, however, has not been discussed or documented in relation to any of the villas in this study, because the preservation of wood normally requires arid or boggy conditions usually lacking in the Mediterranean region. In addition, the removal of nails and clamps has also not been well documented or quantified, despite their ability to be well preserved archaeologically. As nails and clamps were potentially recyclable, knowing how many were left on site would be relevant information for this study. Without larger collections of these materials, most excavators have not quantified them in publication. Indeed, a lack of nails or clamps is also significant because it indicates that they had been removed from the site. Most evidence for systematic roof removal, therefore, comes from stockpiles of tiles set aside, or an absence of tiles, details of which normally are included in excavation reports.

3.4.3 Evidence of Wall Removal

Architectural wall fabrics and decorative facings were highly desirable materials for reuse and recycling. Limestone blocks, predominantly used to build the walls of villas, held value both as cut stones and as the starting material for producing lime. Hypothetically, before accessing any wall fabric, the facing (plaster or veneer) would first have to be removed. Again, like the roof, the method of destruction of the walls was dictated by any future material destinations. To be reused, veneer was removed by loosening the iron clamps that fastened it to the walls and pried away from the mortar backing. This needed to be rather careful work to ensure the marble stayed in large pieces. Otherwise, the wall could have been smashed and the marble pieces collected from the floor. In general, demolishing a wall with a sledgehammer would be the fastest and most efficient method. This would also have had little effect on the recycling potential of the stones, as they would not easily be broken. There is evidence of this type of demolition at Castelculier, where walls were torn down in the residential sector to access limestone blocks and marble that were in turn reprocessed in the lime kiln.64

In the section drawings from the San Giovanni di Ruoti excavations, certain layers, for example Layer 17 in Room 71, are described as containing ‘rubble’ from the Phase 3 destruction.65 The amount of pottery and tile has been quantified but not the amount of stone, even though it was mentioned as a component. There was also an absence of nails in these layers, which suggests either that the superstructure of the villa in Phase 3 was not wood but masonry, or the nails were removed from the site for recycling. It is likely that parts of the walls of Room 31 were also removed at this time, because the midden spilled over, out of the room, and into the hallway (34) during the last part of Phase 3b. If the walls had been left totally intact, then the midden would have been higher than 2.5 m (an estimated average wall height). The people who went through the trouble of removing the roof probably also removed parts of the walls, which resulted in the midden material spilling over into the hallway.

Large marble features, such as columns, lintels, and thresholds would primarily have been desirable materials for reuse, because they not only had already been imported but more importantly, they had already been skilfully worked. Similarly, veneer could have been reused as a wall treatment or for paving a new floor. At Pompeii, reused veneer paved the countertops of bars in the city.66

The large-scale recycling of glass tesserae at Aiano-Torraccia di Chiusi, to be discussed more fully in Chapter 4, suggests that this villa had wall or ceiling mosaics. In addition to the coloured glass, were also discovered with traces of gold leaf. While there were no traces of glass on the walls, the glass recycling workshop was located next to the six-apsed room, which presumably had a vaulted roof that would have supported such a mosaic.67 The proximity of the glass workshop to the source of the material suggests it was systematically removed from the walls. Several fragments of veneer in the apsidal hall suggest that this also adorned the walls, though was removed.68

The clamps for attaching veneer to walls and those used to support columns would also have been valuable, recyclable materials (Figure 3.2). These clamps were commonly made of iron and bronze, measuring 0.1–0.2 m long, and provided they had not corroded, they could be heated and reformed or simply reused if their new destination had the same dimensions and fittings. Nails and clamps would have been removed from the wood, depending on how the wood was to be recycled and whether the nails could be recycled. In theory, any nail that had not corroded could be reused. Alternatively, if there were many nails recovered that had not corroded, they could be heated and then re-smithed to patch or repair other iron objects.69 If we assume that most villa walls were constructed in a combination of field stones, wood, and brick-faced concrete (i.e., not ashlar blocks), then the predominant source of iron from the walls would have come from the nails and clamps used for timber, which was not a significant amount.

3.2. Photograph of marble column fragments showing iron attachment rod.

Plaster was non-recyclable but could be reused as fill for new floors or foundations. Plaster would have been relatively easy to remove, with a hammer or chisel. Unless plaster had been preserved under a collapse or by a higher occupation layer, it was not likely to be visible archaeologically because it disintegrates with long-term exposure to weather.

3.4.4 Evidence of Floor Removal

Salvageable material from floors (and pools in baths) would have included ceramic, limestone, and marble paving stones, and mosaics. Plaster floors were not recycled because they had no use other than providing fill for new wall constructions or make-up levels of floors. Limestone, ceramic, or marble paving stones and mosaics were valuable because they had already been cut or shaped and were relatively easy to remove and load for transport. Evidence for their removal comes in the form of a lack of extant paving, secondary source locations, and also from the remaining imprints of marble paving left behind on the mortar preparation layer.

A good example of this comes from the villa at Linguella, where the marble paving slabs were systematically removed. There was a large reconstruction of the villa between the second and third centuries CE, which included laying opus sectile and mosaic pavements. In Room 4, it is clear the marble paving stones were subsequently systematically removed because the imprints from the stones were still visible on the preparation layer underneath, sealed by the later roof collapse.70 Similar imprints can be viewed in the baths at the Roman villa at Tourega, Portugal, which was abandoned in the late fourth or early fifth century CE (Figure 3.3).71

3.3. Photograph showing imprints of removed marble paving in preparation layer at the bath complex at the Roman villa of Tourega, Portugal.

At Linguella, these marble paving slabs were taken out before the collapse of the roof and therefore targeted for removal instead of simply scavenged from debris. It is unclear whether the huts built over the roof collapse in Room 1 corresponded with the removal of materials of Room 2, or whether both roofs collapsed around the same time, making the huts a later phase than the removal of the marble. Other than the marble, there was no indication in the publication of the excavations whether there were any other materials which had been systematically removed and were missing from the archaeological record. The marble stripped from the building would have been presumably reused to pave the floor of a new building on the island, or perhaps shipped to Rome, as suggested in the excavation report. There was a pile of broken pieces of marble found in the corner of Room 4 which appear to have been discarded and left on site because of their condition.72 Evidently only the large, intact, marble paving slabs were desired in the fourth century CE, which suggests direct reuse elsewhere as paving slabs. The same partial removal of the opus sectile panels and partial removal of mosaics can be seen at Aiano-Torraccia di Chiusi. Several pieces of porphyry, serpentine green from the Peloponnese, and Carrara indicate that the floors were paved with rich marble. But most of this material appears to have been removed, because it was no longer at the site.73 In the villa baths at Gerace in Sicily, the marble, bricks, pilae, and tubuli were removed following damage to the structure by an earthquake in the second half of the fifth century. Repairs were attempted then abandoned; the reusable and recyclable materials were removed and then the bathing rooms were used as middens.74

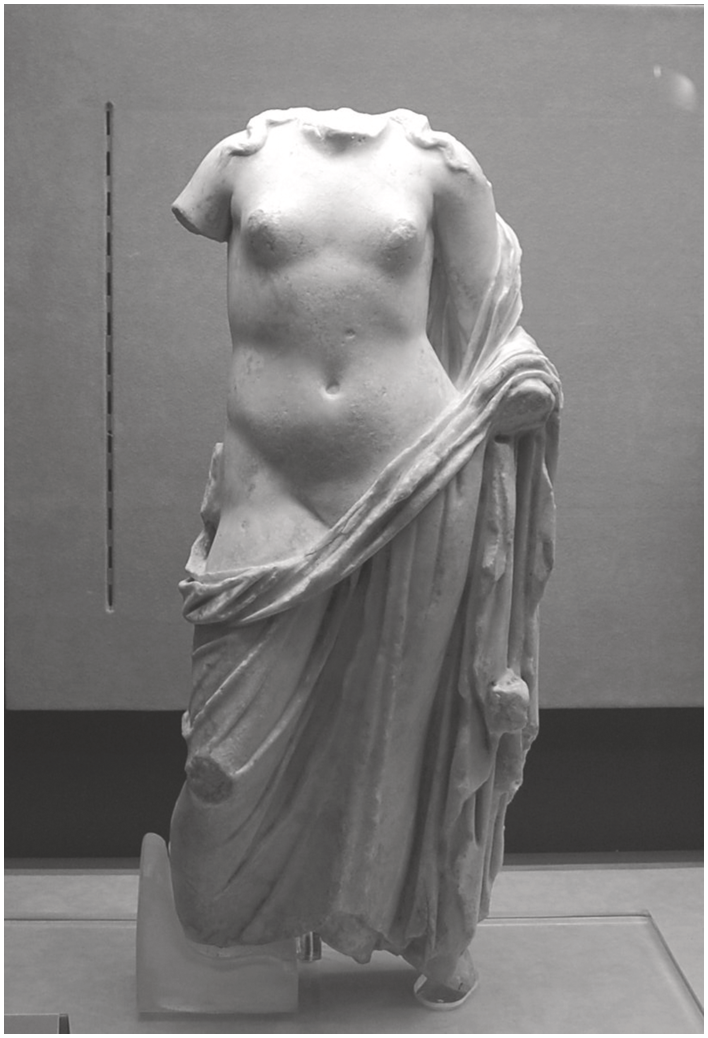

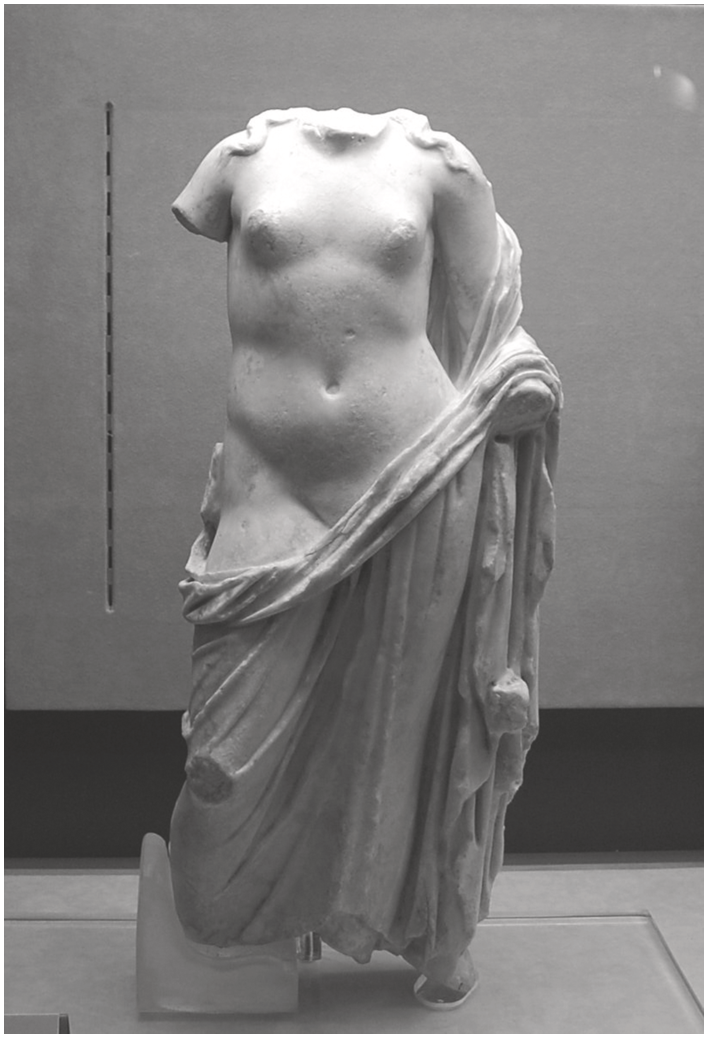

Similarly, at Torre degli Imbrici, there was distinct lack of marble paving on site. Levels below the floor of a large apsidal hall were reached with no marble left in situ. One would expect to find a good quantity of marble on a site with such a large plan and with large architectural features but only small pieces of veneer have been uncovered in the collapsed layers of a wall. Larger pieces of marble have been discovered on site, including a statue of Aphrodite, now in the Melfi museum, and several large decorative lintels in the nearby field (Figure 3.4). It is possible that the more reusable marble pieces, such as paving and veneer, were removed while the larger sculptural pieces and lintels were left on site because they were too awkward.75 It is also conceivable that there was a lime kiln here, where smaller pieces of marble were being burned, although this has not been found.

There was also the possibility that there was never any marble paving on site to begin with or that the last phase of the villa was left unfinished. This was also the case in the late antique phases at apsidal halls at the Villa of Maxentius in Rome and the Villa Magna in Lazio. At both sites too, there was no evidence of floors, suggesting that either these structures were unfinished, or materials were removed with no archaeological trace of preparation layers. C. Fenwick speculates that at Villa Magna perhaps the lack of decorative floor suggests that this apsidal hall was used instead for making wine.76 This intriguing possibility would explain the lack of flooring at these sites but would dramatically alter our understanding of the function of these ‘unfinished’ or entirely salvaged apsidal halls.

Unlike Linguella, marble was not removed from other sites, like Faragola. Here, most of the paving was in situ, which meant that there was no need or desire for marble reuse or recycling. It is worth noting at this stage that there has been no church structure or extended village discovered in the vicinity of the villa.

Pilae – as usually intact, regular tiles – from the hypocaust systems at villas were also a favoured material for removal. At Fishbourne in the late third century CE, the suspended floors of the East Wing bath complex were destroyed (Figure 3.5). The unwanted rubble was piled in the caldarium flue and space to the east, while most of the pilae were removed from site for reuse. Similarly, at Gerace in Sicily, mosaic floors were broken up to reach pilae in the heated rooms of the baths. Here too, the large bricks that spanned the gaps between pilae were also removed.77

3.5. Photograph of the wall between the caldarium (R) and tepidarium (L), showing removed pilae in the East Wing bath complex at Fishbourne, England (Cunliffe, 1971: Pl. LXIII).

Marble floor slabs could have been lifted using a prying bar and re-laid in another building, or burned for lime, if the marble was not coloured. The other recyclable item would be the mosaic tesserae. Stone tesserae could, like the marble, be removed to be re-laid in a different structure. I have already discussed an example of tesserae reuse at the villa of Badminton Park, but other examples include at Séviac, where mosaics were demolished and reused in other sections of the villa and as backfill in the rebuilt hypocaust, and at Sens (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France), where remnants of an earlier mosaic were recycled into the walls of a Late Antique structure.78

If the coloured tesserae were made of glass, they could also be removed, grouped together by colour, and then remelted to make other glass objects of that colour.79 The villa at Milhaud in southern France shows evidence of this practice – glass was separated by colour and placed into dolia set in the floor of a workshop; the glass fragments were from vessels, mosaics, and windows. Melting glass by colour was an easier way to produce coloured glass vessels than adding the colour to the glass in the primary production phase. In this respect, coloured tesserae were quite a valuable material, and if the time was taken to remove them, they would no doubt have been recycled into other vessels, or indeed reused in another floor or wall as tesserae.

The general removal and recycling of the material on the floor surfaces depended largely on the state of the floor and whether the material was needed. If there was a collection of debris from the destruction of the rest of the villa walls, the removal of the floor surfaces might not have been possible. With most of the material stripped from the walls and ceilings, there might not have been a need for this floor material, and in many cases, we see this debris from collapse or destruction left in situ and used as a fill layer for further occupation floors. This has preserved mosaic and marble floors under the destruction layer. However, if the evidence from San Giovanni is accurate, then the floors were very often the most valuable and sought-after material from a villa.

3.4.5 Evidence of the Removal of Fixtures

At many villas, lead pipes were removed in the post-Roman phases. There are, however, exceptions, including at El Ruedo in Andalusia and Torre degli Imbrici, where long pieces of pipes were discovered (Figure 3.6). The removal of lead pipes is evidenced at other sites by both the absence of lead and the recycling of lead on site. At San Giovanni di Ruoti, the almost complete absence of lead objects or pipes clearly demonstrates their removal. The only two exceptions to this were in Room 38, where a fragment of a lead pipe was uncovered, and in Rooms 57 and 48, where lead door-hinge sockets were discovered.80

3.6. Photograph of lead water pipe, recovered from the villa El Ruedo, Spain.

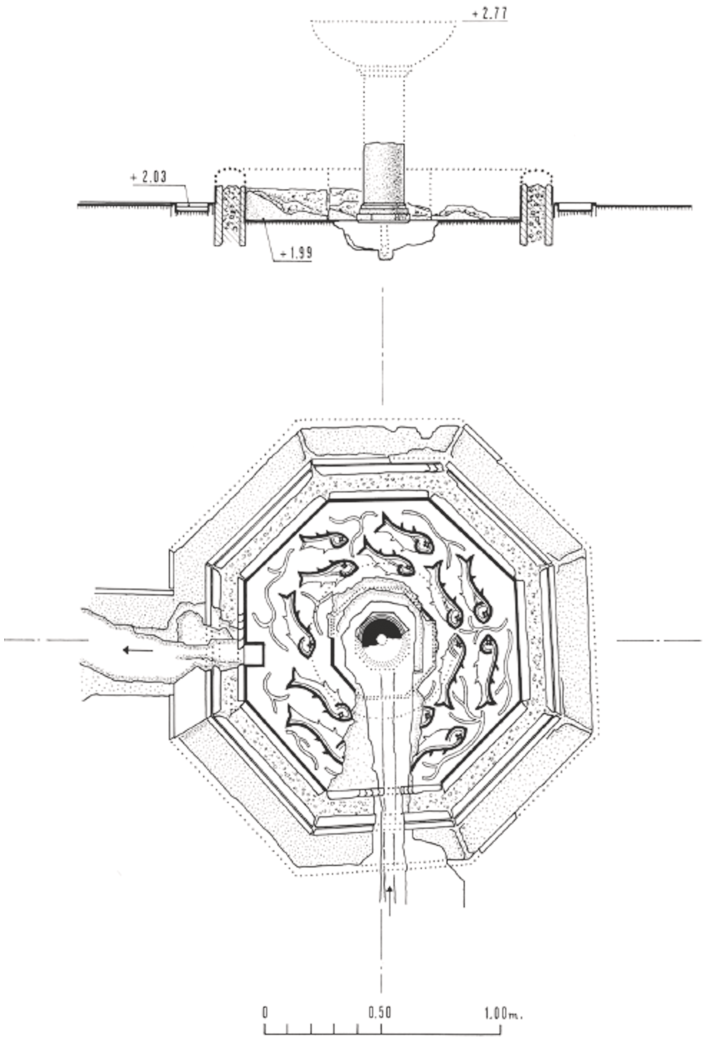

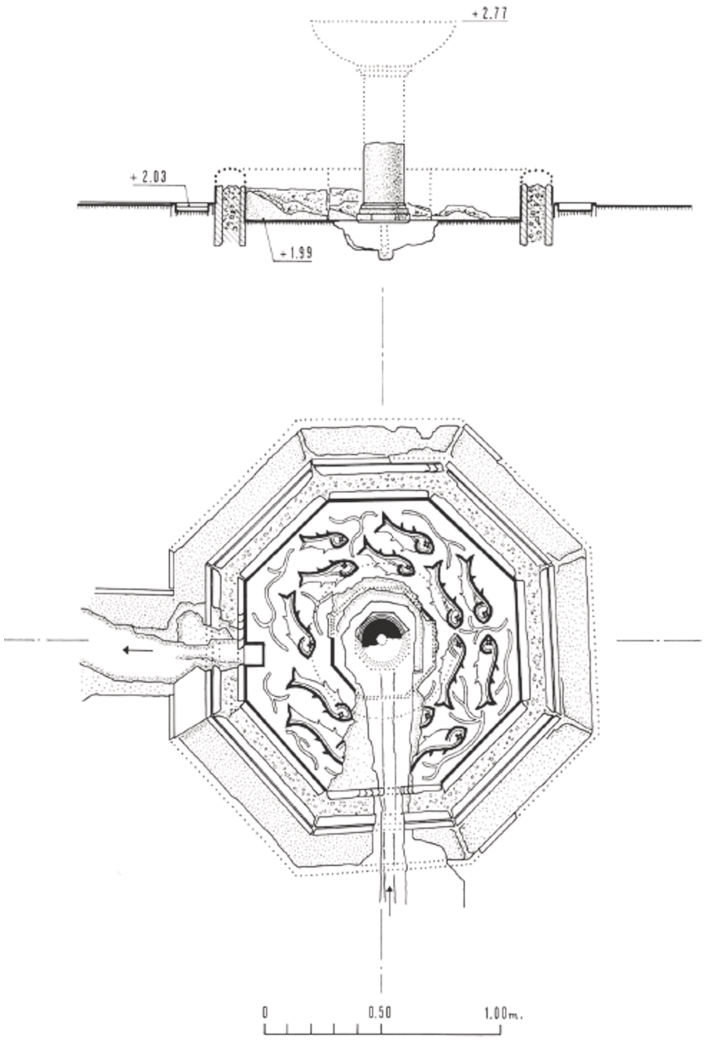

At Saint-Émilion – Le Palat, incredible efforts were taken to remove the lead piping from water features in the residential villa in the post-villa phase. Not only were all the pipes dug out from under the flooring, but in the same phase, a marble column, which supported a vertical lead pipe that fed this water feature, was broken open to access the metal (Figure 3.7).81

3.7. (L) Lower part of the marble column of the octagonal basin, that supported lead piping on the interior. 30 cm high. (R) Reconstruction of the octagonal fountain feature, Room 1, Saint-Émilion – Le Palat (after Balmelle, Gauthier and Monturet Reference Balmelle, Gauthier and Monturet1980: figs. 3 & 4).

At Faragola, the absence of lead features and the presence of lead recycling facilities suggest that not only was this material removed, but, at least to some degree, was reprocessed on site, as will be examined in Chapter 4.82 Similarly, at Monte Gelato, there were no lead pipes remaining in the baths or elsewhere on site. There were several ceramic drains and pipes preserved, so it is not clear whether the villa would have also had lead pipes.83 A lead pipe was also removed from the area of the atrium at Settefinestre (Room 52).84

In terms of evidence of the systematic removal of other decorative features and movables, it seems that, on the whole, residents of the villas would have taken most of their precious belongings with them when they left the site. There has been the occasional interesting architectural adornment found, such as a copper alloy appliqué found at San Giovanni, which indicates that this was either missed or unwanted by those salvaging materials from the site.85 The exception to this absence of décor, was marble statuary and large marble cornices, found in the fields at Torre degli Imbrici and in the lime kiln at Monte Gelato. In the case of Torre degli Imbrici, it was clear that this marble was left on site because it was too large and heavy to move. In the case of Monte Gelato, it was the opposite, where the marble statuary was indeed removed to be burned for lime. None of these marbles were taken away from the site, however, and thus were not viewed to be of sentimental value by the owners or were impractical to move.

Removal of the lead pipes may have required prior removal of floors or partial removal of walls, depending on the location of the pipes. Removal of any desired iron fixtures would have been easier and would not have required that walls or floors were destroyed to access this material. As such, this may have been one of the first things removed from the villas.

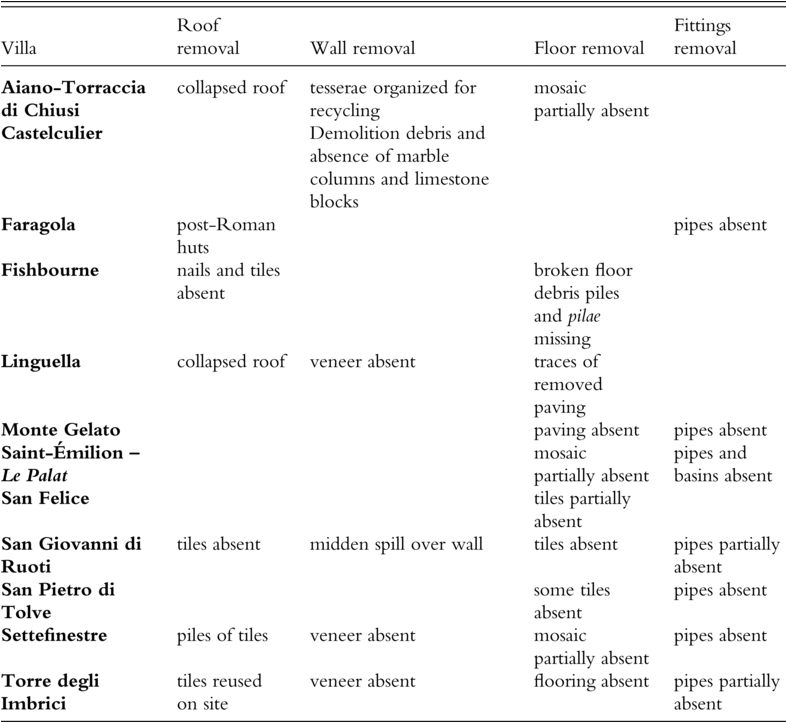

3.4.6 Summary of Evidence

The previous sections have considered the evidence for the systematic removal of architectural features and some movables. As summarized in Table 3.2, the evidence for material salvage comes from the absence of expected materials within sealed archaeological contexts. Assessing this absence, however, must be done in conjunction with a good understanding of the types and quantities of materials used to construct luxury villas. It is easier to undertake this type of assessment with luxury villas, as opposed to smaller settlements for example, because there was a range of materials used to construct and decorate the buildings.

Table 3.2. Summary of evidence for systematic removal of materials from a selection of sites.

The systematic removal of materials could have been done in a careful or a destructive manner, dependent on whether the material was going to be reused or recycled. Materials destined for recycling could have been destructively removed if they could be easily collected for storage.

It is worth emphasizing that the ability to salvage specific materials requires both materials organization and project coordination. For some material categories, such as the roof tiles and furniture and interior wall and floor treatments, there was no need to remove any other materials first. They simply needed to be pried or taken apart. But for others, such as wooden roof supports, wall blocks, iron fittings, or pipes, other parts of the villa needed to be dismantled first, making these at least a two-stage process. Neither scenario accounts for any necessary clearing that might have needed to take place before materials could have been accessed. For instance, in many cases, roofs would have collapsed before salvage, and thus roof tiles would have needed to be cleared off floor surfaces, for example, before these could have been accessed. All of this points to a basic level of organization of workers for any systematic salvage of materials. Indeed, the cases highlighted indicate that certain materials were targeted at certain sites and not others. This targeted approach necessitated knowledge of the structures, materials, and time to undertake the removals.

3.5 Demolition Workforce and Rituals

The systematic nature of materials removal in most cases indicates an organized process and workforce. However, the identity of this workforce remains largely unknown. In Rome, building demolishers were, however, a recognized workforce of professionals, who had a college associated with their ‘craft’.86 While not highly skilled, they may have been made up of general or skilled labourers, depending on the type of demolition required. Recognizing that building materials were normally valued for reuse and recycling, as demonstrated here and by others, the way in which buildings were demolished would have impacted if and how materials could be reused.87 Thus, it was not simply a case of taking a hammer or mallet to smash down walls but required both a knowledge of the construction techniques and the intended purpose of the salvaged materials. This would have required a consultation with a building owner or manager. We could either imagine this workforce as an itinerant workforce, or one that was commissioned from cities or towns, but they were most likely specialists in construction and/or demolition.

A further clue as to the identity or status of these individuals might be gleaned from what appear to be ritual demolition deposits at many of the villa sites. At present, we have a relatively poor understanding and little evidence of construction and deconstruction rituals. In part, this is due to the lack of archaeological exploration of areas of buildings that might contain evidence of such ritual deposits – specifically foundation trenches, in the case of construction rituals, and ephemeral pits in the case of both construction and deconstruction rituals. If discovered and written about, this is usually by chance, and I suspect many such deposits are missed or misreported from excavations.

Distinguishing the motivations for intentional depositions in the late Roman west has become an area of increasing scholarly focus over the past twenty to thirty years.88 Indeed, many studies attempt to classify activities under a single motivation: ideological (including religious), ritual, or pragmatic.89 A famous case comes from the villa at Chiragan, where large quantities of marble statuary were discovered in post-Roman pits. Various scholars, including myself, have interpreted these pits as the result of the Christianization of the site, its impending invasion by barbarians, and in preparation for recycling.90 However, the deposit of non-sculptural materials has received considerably less attention.

The work of R. Fleming has provided an important case study which highlights the practice of ritual deposition in the fourth–fifth centuries CE in Roman Britain. Fleming highlights the prevalence of ritual deposits associated with the closure of sites in the late antique period.91 The ritual deposits were usually made in disused water features, like wells, and included large collections of building materials (brick, tile, stone, nails, plaster) but also animal bones, human remains, especially skulls, coins, quern stones, and shoes, complete or nearly complete ceramic pots and pewter vessels, and oyster shells and hazelnuts.92 Examples come from both rural and urban domestic contexts (villas, luxury town homes, farmsteads) and some wells in Romano-British towns as well. The combination of building materials, with mammal remains, vessels, coins, and foodstuffs, and the repeated pattern of these deposits, suggests that they are of a ritual nature, not simply a rubbish dump. Fleming notes that despite the Romans leaving Britain in the fourth century, Roman masonry materials were not systematically reused for new constructions until the seventh century, presumably because builders did not possess the skills needed to construct in large scale masonry.93 The depositions, which date to earlier periods, appear to mark the closure of sites rather than any other kind of transformation or systematic material salvage.

At the villa sites in this study, there are several deposits aside from the systematic organization of single materials noted that require further exploration. From a review of the evidence, I have identified five types of ritual building material deposits:

1 Construction deposits – made during the initial construction of a building, often including coinage or evidence of a feast performed at the time of laying the foundations of walls, but also seen in pits.

2 Reconstruction deposits – made during the reconstruction of a site to mark the transition from one phase to another, these often contain building materials from the old villa mixed with ash, charcoal, animal or human bone, coins, ceramics, and food remains.

3 Closure deposits – made to mark the end of a building’s life, with similar compositions as #2, though also including personal items that were used in the estate.

4 Demolition deposits – made to mark the removal of building materials from a site. Sometimes #3 and #4 can be the same, but in some cases, these were made at different times, especially when abandonment of a residence occurred much earlier than building material salvage phase.

5 Recycling deposits – made specifically next to the workshops of craftspeople who were transforming the materials. Again, in some cases these are difficult to distinguish from the demolition deposits (#4).

All of these deposits were intended to mark a transformation, be that of a site (when a new building is constructed/when a building is reconstructed) or of materials (when they were removed or recycled). In most cases, these deposits have been identified at villas either because they seem out of place or unusual in relation to the other processes in the vicinity, or because they contained the combination of organic, building, ceramic, monetary, and/or personal materials as previously noted. The following is not intended to be a comprehensive survey of such ritual depositions at villas, but I want to highlight some examples from the sites featured in this study to note the relationship with removal and recycling processes and workforces.

3.5.1 Construction Deposits

As already indicated, construction deposits are among the most difficult to identify because they were often placed in foundation trenches, which are not often explored archaeologically or if they are, not extensively. At Montmaurin, however, a deposit in Room 59, to the left of the main entrance, contained evidence of a ritual that was performed, potentially during initial construction of the villa. Room 59 contained a tiled platform that evidently supported a hearth which had been used many times. The central tile of the hearth was not ceramic like the rest but a paving stone in marble from the local St-Béat quarries in the foothills of the Pyrenees. This stone was very burnt and worn indicating it had been subjected to fire on multiple occasions. This room also contained what Fouet described as a small bench altar, like those used in Gallic religious ceremonies. However, under the hearth paving stones was a pit of about 60 cm deep, which contained very soft and dark earth, rich in debris (small animal bones but also ceramic sherds, a bone pin, a bronze ring, fragments of glass vessels, and a lamp). Near the top of the pit, there was a dupontus of Trajan and further down two other coins: one of Tiberius, the other of Philip. The first phase villa was constructed in the mid–first century CE and was in use until the third century.94

3.5.2 Reconstruction Deposits

There is more evidence for reconstruction deposits, as they have been found in the fabric of extant villa structures. At the imperial villa at Villa Magna a single column fragment was found in a pit, intentionally cut while the villa was reconstructed in the second century. The pit was cut through the natural yellow clay. The column itself had traces of plaster, which held a fragment of Italian terra sigillata of Tiberian date. It seems to be that this column drum was a sort of votive deposit, or piaculum, to commemorate the demolition of the earlier building that was torn down to facilitate this construction. The deposit was then covered by the build-up of the ground level, before the stone paving was laid, and thus the act of deposition must have occurred before the reconstruction was finished, perhaps even before it began.95

There was also a second small, isolated pit against the southern wall of Room 59 at Montmaurin, lined with large pebbles and filled with ashes and charcoal, mixed with carbonized bone, sherds of a pitcher dated to the fourth century, and two coins of Gallic emperors from the fourth century.96 This coin coincides with the reconstruction of the villa in the fourth century. Placed in the same room as the first deposit, it appears that this space held a ritual function throughout the life of the villa and that even 200–300 years later it was used again to mark the transformation of the site.

At Monte Gelato the curious filling of the ‘fishpond’ in the second–third century points to an intentional if not ritual marking of reconstruction. This feature was located against the northern wall of the porticoed courtyard. In its original manifestation, it was a plaster-lined, rectangular tank, with pipes and drains built into the walls of the tank for water circulation. The fill of the tank contained what appeared to be at least two separate deposits, separated by a thin plaster layer. The bottom, oldest fill which dated to the early second century contained much tile, an iron key and six nails, glass bead, copper brooch, bone needles, and a strip inlay. This was then separated from the upper fill by the thin layer of plaster. The upper fill contained much more material, including copper personal items and object embellishments, lead weight, numerous bone personal items, two glass counters, stone weight, and many architectural fragments in iron, such as two keys, the complete neck of a crater, much tile, box flue tiles, mosaic pieces, and 124 fragment of marble veneer. In addition, in the upper fill there were two articulated skeletons of working dogs and both fills contained other species of animals including chickens, dormice, fishbones, and two oyster valves. The later fill dated to the later second or early third century. Both deposits contained more than 400 ceramic sherds, many of which were of local production, and there were graffiti on some fragments in both Latin and Greek. The Greek lettering is particularly fascinating and suggests that people of Greek origin worked on the site, perhaps literate enslaved peoples.97

The phasing of these deposits at Monte Gelato coincides with the site reconstruction in the second–third century; this was the phase when the bath complexes were built. By the early third century, the fishpond was entirely filled. However, the recycling activities do not appear at the site until the fourth century. What were these fills in the fishpond? The upper fill is suggestive of the type of closure deposits that Fleming discusses at Romano-British sites, however, it is not reported to have contained any charcoal, which rules out any burning or ritual feasting at the deposit. But the mix of animal bones, personal items, graffitied sherds, and a range of building materials suggests a ritual deposit, rather than a rubbish dump. If we assume that these deposits relate to the marking of a transition in the life of the building, there are two possibilities: the first is that the fills related to the end of one phase (the Augustan phase) and the construction of the second phase (the second–third century phase), or the second possibility is that the first deposit relates to the reconstruction of the villa in the second century and the upper deposit relates to the final closure of the site, when it was not totally dismantled but left by its occupiers. The recycling of the building materials then would have happened some 100 years later and remained (as far as was discovered on excavation) unmarked by ritual.

3.5.3 Closure Deposits?

Other than the example noted from Monte Gelato in the previous section, there are no deposits that we could specifically identify as ‘closure deposits’ in the way they are described by Fleming. Indeed, there are both chronological and technological differences in the recycling that occurred in Roman Britain and elsewhere in the Roman west between the fourth and seventh centuries.98 As already noted, in Britain, there does not appear to have been large scale, systematic reuse or recycling of building materials until the seventh century, but most of the residential structures went out of use in the fourth and fifth centuries. With a chronological gap, as potentially at Monte Gelato, a closure deposit would significantly precede any materials removal or recycling. However, at most of the villas in this study, this does not seem to have been the case. Materials salvage usually occurred shortly after abandonment and therefore ritual activities marking this transition could have been ‘closure’ activities. At Aiano-Torraccia di Chiusi, and others, where there was a gap of potentially fifty years between site abandonment and material salvage, it is equally possible such deposits have not been identified or reported.

Middens at both Faragola and San Giovanni di Ruoti appear to represent a clearing of materials from the villa. In the western hallway and porch of the dining room at Faragola, excavators discovered two deposits of mixed materials: kitchen ceramics, amphorae, glasses, metals, objects of personal adornment, furnishings including some fragments of the marble opus sectile panels originally housed on the stibadium of the cenatio, elements of furniture, organic remains, a human skullcap, iron waste, and burnt vegetable residues.99 Similarly at San Giovanni di Ruoti, numerous middens of mixed domestic and building materials were found in former rooms of the villa, notably in Room 77 and in the western corridor. Excavators described these as rubbish dumps from the final phase of occupation (early sixth century), but comparing this now with the results from Faragola, it seems possible that these middens were instead the result of the clearing out of the site before some material removal, and final abandonment.

3.5.4 Demolition Deposits

During the demolition of the large bath complex at Settefinestre in the second–third century, two material deposits appear. The first, already discussed, was the pool in the frigidarium, which acted as a material collection point for tiles and marble, predominantly.100 In the pool of the caldarium, however, there was a second deposit of materials, this one of a more mixed nature. The marble was firstly removed from this feature, then on top of the preparation layer was a mixture of decomposed bricks, ash, animal bones, and the remains of shells. Evidently these materials had been subjected to fire and were very possibly the remains of a ritual burning, which appears to have been contemporaneous with the material removal. Here it seems that people involved in the demolition marked these activities with a ceremony and final deposition, very unlike the remains of the intentionally collected building materials in the frigidarium pool.

A similar pit to those in the Room 59 at Montmaurin was discovered in one of the atria of the villa (Room 38). This pit contained burnt pebbles, pieces of brick, calcinated marble and sandstone, pottery and glass dating from the mid-fourth century, several dozen small cubes of mosaics in colored glass, two dozen oyster shells, and small animal bones from cow, pig, sheep, chicken, hare, and a fox. Two coins confirmed that this fill was not deposited before the third quarter of the fourth century. While similar in composition to the first two pits, this one clearly contained more and mixed building materials; its dating suggests this was a deposition relating to the material salvage phase of the site. It is worth noting as well that glass recycling operations took place in a space right outside of the atrium, in Room 40. It is not clear if the deposition preceded or was contemporaneous with the recycling.

Additionally, a ‘garbage dump’ of materials was discovered during the original 1969 and 1982 excavations at the villa of Torre Llauder on the Mediterranean coast in northeast Spain. These deposits were located away from the residential structure of the villa, though it was unclear from the excavation plan and report exactly where they were situated.101 But what is described are mixed materials deposits which were made up of large amounts of animal bones as well as building rubble, with opus signinum, bricks, marble veneer and other miscellaneous objects, including ceramics. There were five unique deposits identified. One datable to between 200 and 250 CE, while the others dated to the sixth century CE.102 The first coincides with a phase of villa reconstruction in the third century and then the bulk of the deposits align with the abandonment phase of the villa. We could posit that the third century deposit was a reconstruction deposit, while the rest were demolition deposits. Like at Montmaurin, there was the reuse of a deposition area in different phases, but likely with the same purpose in mind. There is no recorded evidence of a ritual meal here and no reported recycling at this site, but numerous reassessments have been done of the original excavations, and it would not be surprising if material salvage, ritual, or reprocessing evidence was missed.103

3.5.5 Recycling Deposits

The final category of deposits appears to be specifically associated with hearths and installations used for the transformation of materials. While at present there is only one secure case at a villa, I have also recently seen what I believe to be an example of this in the urban setting. The excavations at Aeclanum in Campania have uncovered evidence of the deconstruction and material salvage of components of the former Roman theatre in the late antique phase. During this period, a large church was constructed in the town, and it later became the seat of a bishopric. The huge ashlar limestone blocks used to build the cavea of the theatre were reused to build the church, and metal components that fed water features in the theatre (fountains, perhaps) were salvaged and reprocessed in the foundation layers of the theatre. Specifically, it appears as if they removed a large lead tank, iron features, and some of the lead pipes. At the mouth of the keyhole shaped reprocessing installation a curious set of objects was discovered: the bottom half of a courseware vessel, with a chunk of semi-fused iron inside, was covered with a fragment of marble, itself displaying evidence of exposure to heat.104 On top of the marble was a small domestic vessel filled with ash, small animal bones, and seeds. These artefacts acted as fuel to heat the contents in the top container, with the semi-molten iron used as a heat source. While this feature could have been the result of an ordinary meal shared by craftspeople, its location at the end of the flue channel of a recycling installation and the presence of iron and marble as well as foodstuffs and animals suggest that this was instead the remains of a ritual feast, intentionally left behind at the worksite. This would have marked the reprocessing of the iron (and perhaps other metals).