1. Introduction

Future Design (FD) refers to designing and implementing practices that create a society for which future generations will be grateful (Krznaric, Reference Krznaric2020; Saijo, Reference Saijo2018). This paper develops a comprehensive theoretical framework for FD by introducing three key abilities – futurability, presentability, and pastability – and their corresponding design approaches. Through this framework, we aim to address the accelerating ‘future failures’ – crises that have intensified since the Industrial Revolution (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015), with researchers warning that we have already crossed planetary boundaries in six of nine Earth system domains (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges and Rockström2023).

Our framework responds to the inadequacy of existing mechanisms – markets, democracy, and scientific innovation – in addressing intergenerational concerns. By reviewing evidence from experiments and field applications, we demonstrate how these three abilities function as ‘leverage points’ (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999) that can transform decision-making across temporal scales and catalyse systemic change.

The pattern of innovation with mixed intergenerational consequences is exemplified by cases such as the Haber-Bosch process (see Text Box 1). This pattern – technological innovations optimised for immediate gains but creating long-term consequences – illustrates our difficulty in balancing present needs with future responsibilities, a central tension that FD seeks to address.

Text Box 1: The Haber-Bosch Process – Innovation with Mixed Consequences

The Haber-Bosch process exemplifies how technological innovations can have profound but contradictory intergenerational impacts (Erisman, Reference Erisman2021; Erisman et al., Reference Erisman, Sutton, Galloway, Klimont and Winiwarter2008; Hager, Reference Hager2008). Developed in the early twentieth century, this process enabled industrial nitrogen fixation, preventing widespread famine and supporting unprecedented population growth. However, it simultaneously facilitated weapons manufacturing – with nitrogen-based explosives from this process used in virtually every major conflict from World War I to the present – and has disrupted natural biogeochemical cycles on a global scale.

Fritz Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for this discovery, though he led Germany’s chemical weapons programme during World War I. Carl Bosch, who industrialised the process and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931, later reflected on these contradictions. As Hager (Reference Hager2008:262) documents, ‘Back in 1932, just before Hitler first took power, Bosch had said about the Haber-Bosch ammonia process, “I have often asked myself whether it would have been better if we had not succeeded. The war perhaps would have ended sooner with less misery and on better terms. Gentlemen, these questions are all useless. Progress in science and technology cannot be stopped. They are in many ways akin to art: One can persuade the one to halt as little as the others. They drive the people who are born for them to activity.”’

FD originated in Japan in the early 2010s (Saijo, Reference Saijo2018, Reference Saijo and Saijo2020a, Reference Saijo2020b, Reference Saijo2025). It requires a methodology that works with individuals’ inherent temporal cognitive capacities to design a society that avoids future failures and that future generations will appreciate (Ord, Reference Ord2020). Thus, we aim to design mechanisms that activate our ‘futurability’ – the human capacity to derive satisfaction from prioritising future generations’ happiness, even when this requires sacrificing immediate gains (Inoue et al., Reference Inoue, Himichi, Mifune and Saijo2021; Saijo, Reference Saijo2018; Shahen et al., Reference Shahen, Kotani and Saijo2021).

This framework differs significantly from the mechanism design (MD) approach in traditional social sciences (Baliga & Sjöström, Reference Baliga and Sjöström2007). MD formulates societal goals in terms of distributive justice, allocative efficiency, and sustainability, then designs mechanisms through which individuals achieve these goals by pursuing self-interest. Crucially, MD treats participants’ preferences and values as fixed inputs – predetermined evaluations that remain unchanged throughout the process.

FD, by contrast, targets these evaluations themselves (Saijo, Reference Saijo2020b). Rather than taking preferences as given, FD aims to transform our fundamental way of thinking through mechanisms that activate specific abilities. By increasing futurability, we cultivate a society where considering the ‘happiness of future generations’ becomes natural rather than exceptional. This paper introduces two additional abilities – presentability and pastability – alongside their corresponding design approaches: present design (PrD) and past design (PaD). Together, these form a comprehensive framework for addressing both present and future challenges through transformed temporal perspectives.

FD aims to develop mechanisms that activate three abilities for overcoming future and present failures. This approach builds upon an interdisciplinary foundation. Philosophically, it engages with Parfit’s (Reference Parfit1984) seminal work on intergenerational ethics and the ‘non-identity problem’ – our difficulty in conceptualising obligations to specific future people whose very existence depends on our present choices. Bykvist (Reference Bykvist2007) and Gosseries and Meyer (Reference Gosseries and Meyer2009) further enrich this discourse by providing frameworks that legitimise incorporating future generations’ interests into current decision-making processes.

From systems theory, we adopt Meadows’s (Reference Meadows1999) concept of ‘leverage points’ – places in a complex system where small interventions produce disproportionate changes. We propose that futurability, presentability, and pastability function as such leverage points, where targeted interventions could catalyse broader paradigm shifts (Abson et al., Reference Abson, Fischer, Leventon, Newig, Schomerus, Vilsmaier and Lang2017; Fischer & Riechers, Reference Fischer and Riechers2019). This connects with psychological research on ‘prospection’ (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Railton, Baumeister and Sripada2013), which examines how future-thinking capacities influence present decision-making.

The paper is structured as follows: Sections 2–4 define the three abilities and mechanisms to activate them; Section 5 explores optimal sequencing of design approaches; Section 6 clarifies relationships among abilities and designs; Section 7 addresses participant selection; and Section 8 connects FD to inner transformation approaches and suggests future research directions.

2. Futurability

This section examines futurability – the ability to prioritise future generations’ happiness over immediate gains – by tracing its evolutionary roots, differentiating it from related concepts, and reviewing evidence for mechanisms that activate this ability.

2.1. Evolutionary origins and definition

The origins of future-oriented thinking can be traced to our earliest ancestors. Evidence from archaeological sites in South Africa suggests that hominins developed the capacity for future-oriented planning over a million years ago (see Text Box 2). This evolutionary development laid the foundation for what we now call transcendability and, eventually, futurability.

Text Box 2: Fire, Predators, and the Origins of Future Thinking

Between 1.5 and 1.8 million years ago, a hominin boy was attacked and killed by a leopard in Swartkrans, South Africa, with bite marks from the predator’s canines evident on his skull (Brain, Reference Brain2009; Cribb, Reference Cribb2017). Our ancestors lived under constant threat from such predators.

Strong evidence from the same site suggests that hominins began using fire 1.0–1.5 million years ago (Brain & Sillent, Reference Brain and Sillent1988) to protect themselves from predators like leopards, which feared fire. As Cribb (Reference Cribb2017:5) observes:

‘To conquer their own fear of fire, and to exploit the leopard’s, was a spectacular leap forward into the age of humanity. To do such a thing requires a very special skill: the ability to look into the future, to imagine a possible threat – and to conceive, in the abstract, a way of meeting it.’

This represents a paradigm shift in cognitive evolution. Our ancestors understood predators’ fear of fire and overcame their own fear to exploit this advantage. In doing so, they realised they could protect not just themselves but their descendants as well. This marks the emergence of transcendability: ‘The ability to transcend immediate circumstances, project into the future, and develop abstract solutions for survival and welfare.’

Unlike other animals, our distant ancestors developed and utilised this transcendability, leading to a fundamental cognitive paradigm shift (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999). This evolutionary breakthrough – the capacity to transcend the present moment – laid the foundation for what we now call futurability and represents humanity’s unique ability to consider the welfare of future generations.

We can observe this transcendability in parental behaviour: when food is scarce, parents prioritise providing for their children, even if it means reducing their own food intake. Although this demonstrates transcendability, it applies to blood relatives. We want to extend this to future generations not related by blood and make the sacrifice of our own generation explicit. Therefore, futurability is defined as follows:

‘The ability to feel happiness by aiming for the happiness of future generations, even at the expense of immediate gains.’

This definition positions futurability as both a cognitive capacity and an affective disposition. This concept relates to, but is distinct from, several established theoretical frameworks.

2.2. Distinguishing futurability from related concepts

Futurability shares conceptual space with MacAskill’s (Reference MacAskill2022) ‘longtermism’ – the view that positively influencing the long-term future is a key moral priority. However, while longtermism proposes a normative ethical stance, futurability emphasises the psychological capacity that enables such moral consideration. Similarly, UNESCO’s concept of ‘futures literacy’ (Miller, Reference Miller2018) addresses the cognitive ability to understand how futures shape present perceptions, but lacks futurability’s explicit focus on happiness derived from intergenerational care.

Futurability builds upon Parfit’s (Reference Parfit1984) work on intergenerational ethics and extends more recent work by Bykvist (Reference Bykvist2007) and Gosseries and Meyer (Reference Gosseries and Meyer2009). By focusing on this foundational ability rather than specific domains like environment or peace, we target what Meadows (Reference Meadows1999) calls a ‘leverage point’.

How does futurability relate to sustainability? While sustainability encompasses diverse domains – ‘water’, ‘food’, ‘energy’, and ‘nature’ (Carmody, Reference Carmody2012) – futurability specifically centres on humanity’s flourishing across generations. This aligns with Ord’s (Reference Ord2020) concept of ‘existential risk’ and Krznaric's (Reference Krznaric2020) concept of ‘good ancestor thinking’.

Futurability transcends conventional sustainability by positioning the ‘survivability of humanity’ (Cribb, Reference Cribb2017) as articulated in Saijo's (Reference Saijo2024) conceptualization of ‘survivability’. While traditional sustainability often focuses on maintaining current systems with minimal disruption, futurability may require transformative changes in how we organise society. This echoes Bostrom’s (Reference Bostrom2013) distinction between ‘sustainability’ (preserving particular resources) and ‘existential risk reduction’ (preserving humanity’s future potential).

2.3. Why current systems fail to activate futurability

Although we may have inherited traces of futurability from our evolutionary past, modern society lacks mechanisms to systematically nurture this ability. The three pillars of contemporary society – markets, democracy, and science – each fail to adequately prioritise future generations.

Consider markets first. Even when we invest for the future, markets systematically prioritise present generations through ‘discounting’ – converting future benefits into present values. This mechanism serves current generations’ interests, not future generations’ well-being. While this is not intended to deny investments that activate futurability, little evidence exists that this is mainstream practice. Furthermore, consider the resources that future generations want the current generation to leave behind. Future generations lack the financial means to purchase them in current markets. In other words, markets are not mechanisms to bring future generations into the present (MacAskill, Reference MacAskill2022).

Next, consider a democratic system, especially a representative democracy. A mayoral candidate promising to immediately ban all fossil fuel vehicles, power plants, and chemical fertilizers for future generations’ benefit would likely lose the election. Therefore, most candidates for election are thoroughly beholden to the voters of the ‘present’. Democracy is not a system that considers the happiness of future generations (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie, González-Ricoy and Gosseries2016; Manin, Reference Manin1997).

Scientists and engineers basically invest all their energy into what they want to do. While some may conduct their research with full consideration of how their work will affect future generations, their efforts may result in future failures, as the Haber-Bosch example in Text Box 1 illustrates.

While the three pillars are not mechanisms for fostering futurability, a complementary concept called Sustainable Development (SD) exists, proposed by the Brundtland Commission in 1987 (Brundtland & Khalid, Reference Brundtland and Khalid1987). SD involves ‘meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the needs of future generations’. However, this concept raises several questions (Sneddon et al., Reference Sneddon, Howarth and Norgaard2006). Is SD sufficient even if each generation continues to make future failures? Moreover, what are the ‘needs of the present generation’? Globally, one in ten people lives in extreme poverty on less than $1.9 a day, while others live in affluence, causing future failures. Must we meet the needs of those responsible for future failures?

The definition of futurability recognises the possibility that a person’s present needs will not necessarily be met because of a ‘reduction in present gains’. To advance to a sustainable state of development with no future failures, can we achieve such an ideal situation without reducing some people’s present gains? O’Sullivan (Reference O'Sullivan2023) points out that if the population continues to grow at its current rate, providing sustainable food for 10 billion people and meeting the 2°C target for climate change may not be possible.

FD’s approach aligns with emerging institutional innovations like Wales’ Well-being of Future Generations Act (Davidson, Reference Davidson2020), which established a Commissioner for Future Generations to represent unborn citizens in present policy decisions.

2.4. Mechanisms for activation: IM and AM

Let us now turn to the mechanisms by which we can activate our futurability. The Imaginary future generation Mechanism (IM) refers to the current generation mentally time-traveling to the future without ageing, assuming the role of a future generation, proposing a vision of the future, and designing a history from now to that future – a concept we call future history, presenting choices to be made in the present.

This approach builds upon behavioural research on temporal perspective-taking. Hershfield et al. (Reference Hershfield, Goldstein, Sharpe, Fox, Yeykelis, Carstensen and Bailenson2011) demonstrated that when people connect with their future selves through age-progressed renderings or vivid imagination, they make more future-oriented decisions. The IM extends this principle beyond self-continuity to intergenerational imagination. Seligman’s research on ‘prospection’ (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Railton, Baumeister and Sripada2013) further clarifies the cognitive mechanisms underlying our ability to simulate possible futures.

2.5. Evidence from experiments and practice

The effectiveness of the IM has been confirmed through experimental testing and practical applications. The first such experiment was conducted by Kamijo et al. (Reference Kamijo, Komiya, Mifune and Saijo2017), in which a group of three participants represented a generation. The group had to decide through discussion between an unsustainable option (A) and a sustainable option (B). Option A offered a greater monetary gain than did option B. Although the participants were not informed, this difference corresponded to the ‘reduction in present gains’ in the definition of futurability. The group then divided the money from their chosen option among themselves. However, the experiment included a twist: If the group chose option A, both options would yield reduced amounts for the next generation. Conversely, if they chose option B, the amounts for both options in the next generation would remain the same as in the current generation.

Initially, only 28% of the groups chose option B. However, when one of the three participants was designated as an imaginary future person and asked to negotiate with the other two from the perspective of future generations, the selection rate for option B increased to 60%. This was the first test that demonstrated the effect of introducing imaginary future people into decision-making processes. This experimental setup is called the ‘Intergenerational Sustainability Dilemma Game’ (ISDG). Kobayashi and Chiba (Reference Kobayashi and Chiba2020) have developed a theoretical model to explain the result.

The same experiment was conducted in Dhaka, Bangladesh, but the introduction of an imaginary future person had no effect (Shahrier et al., Reference Shahrier, Kotani and Saijo2017a). The selection rate for option B remained at approximately 30%, regardless of whether an imaginary future person was present. To address this, the researchers modified the experiment: All participants played the role of the imaginary next generation and chose what they believed the next generation would want the current generation to choose. Then, they returned to their role in the current generation and made their choice again. If their choices remained the same, that represented the group’s decision. If they disagreed, a majority vote among the three participants determined the outcome. This modification resulted in the selection rate for option B increasing to over 80% (Shahrier et al., Reference Shahrier, Kotani and Saijo2017b).

In addition to the IM, field experiments have confirmed the effectiveness of an accountability mechanism (AM), where the current generation’s decision rationales are publicised and preserved for future generations (Timilsina et al., Reference Timilsina, Kotani, Nakagawa and Saijo2023). An ISDG field experiment in Nepal revealed that when reasons were not publicised, 64% of participants chose sustainable options. With AM in place, this increased to 85%.

However, this mechanism has not been widely adopted in Japanese law. The Law on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs (1999) does not require public disclosure of information related to decision-making processes unless specifically requested. Meadows (Reference Meadows1999) highlights examples illustrating the effectiveness of information disclosure as a ‘leverage point’ in systems analysis.

Practices based on experimental results have been implemented throughout Japan. The first and most comprehensive was in Yahaba Town, Iwate Prefecture (see Text Box 3). FD practices have since expanded to other municipalities and companies across Japan, including Matsumoto City (Nishimura et al., Reference Nishimura, Inoue, Masuhara and Musha2020), Kyoto City (Hara et al., Reference Hara, Nomaguchi, Fukutomi, Kuroda, Fujita, Kawai and Kobashi2023; Kobashi et al., Reference Kobashi, Yoshida, Yamagata, Naito, Pfenninger, Say and Hara2020), Kyoto Prefecture, Uji City (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Mori, Yamada, Hata, Sugimoto and Saijo2024), Kijo Town (Saijo, Reference Saijo2025), and Okayama Prefecture.

Text Box 3: Yahaba Town – Pioneering FD in Practice

In 2015, Yahaba Town in Iwate Prefecture became the first municipality to implement FD comprehensively (Hara et al., Reference Hara, Yoshioka, Kuroda, Kurimoto and Saijo2019; Hiromitsu et al., Reference Hiromitsu, Kitakaji, Hara and Saijo2021). The Cabinet Office had asked Japanese local governments to create a vision for 2060. Over six months, Yahaba structured discussions into two groups: citizens from the present generation considering the future from the present perspective, and individuals acting as imaginary future generations contemplating the present from the future perspective.

The contrast was striking. Present-generation groups consistently framed future problems in terms of present-day issues, saying things like ‘We don't want to have too few nursing homes for the elderly’. In contrast, members of the imaginary future-generation groups wore traditional ‘happi’ coats during town festivals to imagine themselves time-traveling to 2060 while maintaining their current age.

The imaginary future-generation discussions were notably creative. As an example, consider Mt. Nansho, a symbol of the town from where the fictional Galactic Railroad departed. The townspeople knew that Kenji Miyazawa, a famous Japanese author, climbed this mountain and was inspired to write Night on the Galactic Railroad (Miyazawa, Reference Miyazawa1991). Drawing on this cultural heritage, the imaginary future generation proposed transforming Mt. Nansho into a nature park dedicated to Kenji Miyazawa.

Following this success, Yahaba conducted another FD session on water supply with the same citizens, who proposed an increase in water rates that was later implemented. The Yahaba practices yielded significant insights. Changes to the ‘way of life and thinking’ were observed among both participating citizens and session supporters (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Nakagawa and Saijo2024). Staff members who implemented the FD practice underwent a paradigm shift, moving from simply adding originality to supervisors’ work orders to recognising their mission of exercising creativity for both current and future citizens.

Impressed by the outcomes, Mayor Shozo Takahashi officially declared Yahaba a ‘Future Design Town’ in 2018 and established the Future Strategy Office, which evolved into the Future Strategy Department (Saijo, Reference Saijo2025).

Additionally, FD has begun addressing major thematic challenges such as the Japanese agricultural system (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Hayashi, Kameoka, Sasaki, Kuriyama, Ichihara and Saijo2025a), sustainable food consumption (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khatun, Islam, Saijo and Kotani2025), and the nitrogen cycle (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Hayashi, Matsubae, Nishina, Lin and Saijo2025b). The Ministry of Finance (2023) established the Future Design Group, initiating workshops to introduce FD to schools, communities, and local governments and creating an information-sharing portal (https://www.futuredesign.go.jp/). Masters and Ramakrishnan (Reference Masters and Ramakrishnan2024) document several FD practices outside of Japan.

Although IM and AM have shown promise, the search for mechanisms that can effectively activate futurability continues. Experimental studies on alternative mechanisms, such as Demeny Voting (Demeny, Reference Demeny1986; Kamijo et al., Reference Kamijo, Hizen, Saijo and Tamura2019; Katsuki & Hizen, Reference Katsuki and Hizen2020; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Hizen and Saijo2023) and the Veil of Ignorance (Klaser et al., Reference Klaser, Sacconi and Faillo2021; Rawls, Reference Rawls1999), have failed to demonstrate effectiveness in laboratory settings.

FD approaches may face implementation challenges across different cultural contexts. The success observed in Japanese municipalities might not translate directly to other societies with different governance traditions. Additionally, the long-term effects of FD interventions require further longitudinal research. Despite these limitations, evidence suggests that IM and AM offer promising pathways for activating futurability when properly implemented.

3. Presentability

This section explores presentability – the ability to feel happiness by aiming for the happiness of others within the current generation, even at the expense of immediate gains – and its relationship to both present and future failures. We examine why conventional approaches struggle to activate this ability and how FD mechanisms might overcome these limitations.

3.1. Definition and relationship to present failures

FD aims to create a society in which we can activate our futurability to avoid future failures. However, activating futurability can also lead to overcoming present failures, which are failures within a generation in the current time. Present failures extend beyond economic market failures to include social inequities and political dysfunctions.

Consider a market that efficiently coordinates supply and demand without waste. From a conventional economic perspective, this would be considered successful. However, if significant inequality in income distribution exists, it would constitute a present failure, even though it is not technically a market failure. Such failures undermine societal survivability by creating political instability and weakening social cohesion – essential conditions for sustainable societies. Furthermore, extreme inequality threatens trust and cooperation essential for societal functioning (Rothstein & Uslaner, Reference Rothstein and Uslaner2005).

The extent of such inequalities is substantial. The World Inequality Report 2022 shows that the top 1% owns 37.8% of global assets, while the bottom 50% own just 2%. Gender disparities persist as well, with women accounting for only 34.7% of labour income. These examples represent present failures because they compromise social cohesion and stability – prerequisites for addressing future challenges effectively.

Present and future failures are intertwined. The top 10% of carbon dioxide emitters account for 48% of all emissions. The wealthy burn significantly more fossil fuels than those who do not. Over time, the carbon dioxide emissions of the wealthy increase while those of the less wealthy decrease (Otto & Schuster, Reference Otto and Schuster2024). Since burning fossil fuels contributes to climate change, this situation exhibits characteristics of both present and future failures.

Starting from the status quo, those in advantageous positions will be unlikely to address either present or future failures. Democracy and government, which are supposed to correct these present failures, have failed to fulfil their roles effectively, leading to a ‘democracy failure’ or a ‘government failure’. In light of these challenges, we define presentability as ‘the ability to feel happiness by aiming for the happiness of others within the current generation, even at the expense of immediate gains’.

3.2. Theoretical foundations

However, designing mechanisms that enable people to activate their presentability is not straightforward. This challenge connects to several established research traditions.

Batson’s (Reference Batson2011) work on the empathy-altruism hypothesis demonstrates that altruistic behaviour towards contemporaries can arise from empathic concern. Evolutionary approaches by Nowak (Reference Nowak2011) and Fehr and Fischbacher (Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003) explain how cooperation beyond immediate self-interest evolved through mechanisms like ‘strong reciprocity’ – the predisposition to cooperate with others and punish non-cooperators, even at personal cost.

Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) research on governing commons reveals how communities develop institutions that enable individuals to prioritise collective well-being over immediate self-interest. Similarly, Yamagishi’s (Reference Yamagishi2011) trust research examines how cooperation emerges in social dilemmas through trust-building mechanisms.

These research traditions offer theoretical foundations for understanding presentability, though they have not explicitly addressed the design of mechanisms to systematically activate this ability across societal scales – a gap that FD seeks to address.

3.3. Challenges in activation

The concept of presentability extends beyond psychological constructs like empathy (Cuff et al., Reference Cuff, Brown, Taylor and Howat2016). While empathy involves understanding others’ feelings, presentability explicitly incorporates willingness to sacrifice ‘immediate gains’ – adding an economic dimension to social perspective-taking. Numerous studies show that empathic concern does not always translate into costly altruistic action (Bloom, Reference Bloom2016). Empathy without sacrifice may generate understanding but not behavioural change.

Moore’s (Reference Moore2013) work on ‘creating public value’ provides complementary insights, emphasising how individuals and institutions can prioritise collective welfare over narrow self-interest in public administration. Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) research on common-pool resources demonstrates how communities develop sustainable governance arrangements through institutions that activate something akin to presentability.

Current research on activating presentability remains limited, with most approaches focusing on indirect pathways. Shahrier et al. (Reference Shahrier, Kotani and Saijo2024) have begun investigating how mechanisms designed to activate futurability might simultaneously enhance presentability – suggesting intriguing connections between temporal perspectives.

Among members of the current generation, those with higher social status distribute more to themselves. However, when the participants are imaginary future people who consider the income distribution of the current generation, they distribute the income almost equally (Shahrier et al., Reference Shahrier, Kotani and Saijo2024). This equal distribution would reduce gains for higher-income individuals, suggesting that participants had activated presentability – prioritising collective well-being over personal advantage. Future research should further examine the relationship between futurability and presentability.

3.4. Present design (PrD) and its limitations

Present design (PrD) can be defined as the conventional process of envisioning the future from the present perspective. This method is commonly employed in various organisations such as the United Nations, national parliaments, city councils, citizens’ assemblies (OECD, 2020), and corporate decision-making.

Experiments and practical applications have demonstrated that, in PrD, individuals are entrenched in their current circumstances, making it challenging to reform the status quo or envision a transformative future (Hara et al., Reference Hara, Yoshioka, Kuroda, Kurimoto and Saijo2019; Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Kotani, Matsumoto and Saijo2019a). It is not easy to activate presentability or futurability in PrD. Personal interests and incentives hinder reaching consensus on a future vision. Consequently, people default to extending the path from the past to the present directly into the future, an approach known as ‘business as usual’ (BAU).

Experiments with IM have revealed that the older generation typically struggles to activate futurability in conventional PrD, becoming attached to their current positions. However, when assuming the role of imaginary future people, the older generation tends to activate their futurability and demonstrate more originality and creativity compared to the younger generation.

The reasons for this phenomenon are not yet fully understood. One hypothesis is that when older individuals assume the role of imaginary future people, they project themselves beyond their lifetimes, freeing themselves from current constraints when considering the future state of society (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Guizar Rosales and Knoch2023).

Conversely, the younger generation demonstrates limited creativity in PrD. They tend to either extend the BAU approach or imagine unrealistic futures (e.g., flying cars). While the younger generation shows more creativity in FD than in PrD, it still does not match the creativity demonstrated by the older generation in FD visions.

There appears to be a global tendency to prioritise proposals from younger generations because they represent the future. This has been observed in communities, local governments, and even international organisations like the United Nations. However, this approach may lead to an abdication of adult responsibility.

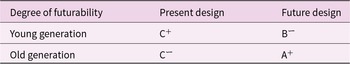

While not based on rigorous academic research, Table 1 presents observations derived from numerous practices, representing the author’s subjective evaluation of these trends. While these observations require systematic empirical validation, they provide valuable insights for FD practitioners and suggest directions for future quantitative research.

Table 1. Degree of futurability of younger and older generations

Note: Degree of futurability is rated on a scale where A represents the highest level of futurability (strong prioritization of future generations’ happiness), B represents a moderate level, and C represents a lower level. The plus (+) and minus (−) symbols indicate gradations within each level.

Even when a young activist such as Greta Thunberg criticises the present situation, demonstrating high futurability (e.g., A++), the older generation – often attached to its current position and interests (C −) (Pearson, Reference Pearson2024) – may not be receptive. This combination can lead to a stalemate.

Applying the FD framework to this generational divide suggests a potential approach: How might Thunberg’s generation more effectively influence the decision-making generation? One strategy could involve inviting the older generation to become the imaginary future generation within structured FD processes, while younger activists participate alongside them, supporting their own ideas while engaging with the visions that emerge from the older generation’s future perspective. This hypothetical application of FD suggests that developing systems that enable the older generation to activate their futurability might bridge generational communication gaps more effectively than direct confrontation.

This approach builds on the observation that older generations demonstrate increased futurability when asked to think as future generations. It fosters a collaborative process where both generations contribute their unique perspectives, potentially bridging the generational gap and leading to more effective decision-making.

A key limitation of current approaches to presentability is their focus on individual rather than systemic transformation. While empathy-building interventions may enhance interpersonal concern, addressing complex societal challenges requires institutional mechanisms that systematically activate presentability across diverse populations. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between futurability and presentability require further empirical investigation.

4. Pastability

This section introduces pastability – the ability to evaluate decisions and actions of people in the past – and its role in complementing futurability and presentability. We explore how this third temporal dimension enhances decision-making and examine mechanisms that activate this ability within the FD framework.

4.1. Definition and purpose

Present decision-making benefits from critically reflecting on past events and historical decisions. In FD, beyond merely examining historical facts, we aim to design systems that activate our ‘pastability’ – a capacity that extends our temporal perspective backward.

Initially, we may consider defining pastability from the perspective of people in the past, mirroring the definition of futurability:

(*)‘The ability to feel happiness by aiming for the happiness of future generations, even at the expense of immediate gains (of that time).’

However, this definition involves several inconsistencies: The ‘immediate gains’ belong to people in the past, not your present self; the ‘happiness of future generations’ includes your present self, shifting the target from others’ happiness to your own; and the ‘feeling of happiness’ belongs to the past person, not your present self.

These inconsistencies arise because we are trying to define pastability as a present-day ability while incorporating historical perspectives. If the goal of FD is to activate futurability, then exercising pastability as described above is not necessarily a primary objective of FD. From the perspective of those in the past, you represent a member of future generations. Thus, pastability must be defined in a way that utilises this fact while acknowledging that we cannot change past events. Therefore, a more appropriate definition of pastability may be:

‘The ability to evaluate the decisions and actions of people in the past.’

This definition distinguishes pastability from mere historical knowledge. Activating pastability involves making thoughtful evaluations of past events and decisions, considering their contexts, intentions, and long-term consequences. This concept connects to established fields in historical research.

4.2. Theoretical connections

Wineburg’s (Reference Wineburg2010) work on ‘historical thinking’ demonstrates that understanding history requires more than factual knowledge – it demands skills in contextualizing, corroborating, and critically evaluating past actions. Seixas and Morton’s (Reference Seixas and Morton2013) ‘historical thinking concepts’ framework emphasises ethical dimensions of historical judgment. Pastability builds upon these approaches by focusing on the evaluation of past decisions for informing future-oriented action.

The concept also relates to Halbwachs (Reference Halbwachs1992) and Assmann’s (Reference Assmann2011) work on ‘collective memory’ – how societies remember, interpret, and use their past. Rüsen’s (Reference Rüsen2005) concept of ‘historical consciousness’ further examines how historical understanding shapes identity and guides action. Pastability extends these concepts by emphasising their role in future-oriented decision-making.

4.3. Past design (PaD) implementation

When implementing IM, people often struggle to embody imaginary future generations and activate futurability. Past design (PaD) addresses this challenge by requiring individuals to evaluate past decisions after reflecting on current conditions (Krznaric, Reference Krznaric2024; Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Kotani, Matsumoto and Saijo2019a, Reference Nakagawa, Arai, Kotani, Nagano and Saijo2019b). This process involves three types of evaluations: gratitude, criticism, and indifference (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Teisl and Noblet2012).

This approach connects to Hirsch’s (Reference Hirsch2008) concept of ‘postmemory’ – how later generations inherit and process memories of events they didn’t directly experience. Similarly, Rothberg’s (Reference Rothberg2009) work on ‘multidirectional memory’ examines how different historical narratives interact and shape each other.

The practical implementation of PaD involves participants assessing whether their present state reflects gratitude or criticism towards past decisions. When past decisions have yielded positive outcomes despite uncertainties, participants express gratitude. Conversely, when future failures stem from past prioritisation of immediate interests, participants critically evaluate these decisions.

PaD then encourages constructing alternative histories – considering what different decisions might have produced. This counterfactual thinking serves as preparation for FD by strengthening temporal imagination. Research confirms that individuals who experience PaD subsequently demonstrate greater futurability activation during FD exercises (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Kotani, Matsumoto and Saijo2019a, Reference Nakagawa, Arai, Kotani, Nagano and Saijo2019b), suggesting that historical evaluation enhances future-oriented thinking.

PaD also considers the sense of obligation towards the dead that may develop over successive generations (Thompson, Reference Thompson2009), which may stem from personal ties, community membership, or a perceived need to make amends for past wrongs. Evaluating these obligations is a crucial aspect of PaD practice.

As definition (*) suggests, potential exists for a form of PaD where one becomes an imaginary past person to activate pastability. However, the effectiveness of this approach has not been verified through experiments. The development of various mechanisms to activate pastability remains an important area for future research.

While pastability shows promise as a complement to futurability, several challenges merit consideration. Cultural and historical contexts significantly influence how past decisions are evaluated, potentially leading to divergent interpretations. Additionally, power dynamics may privilege certain historical narratives over others. Future research should explore how PaD practices can incorporate diverse perspectives while maintaining effectiveness across cultural contexts.

5. Future design, present design, and past design

Having defined the three key abilities – futurability, presentability, and pastability – and their corresponding design approaches, this section examines how these designs should be sequenced in practice to optimise their combined effectiveness.

5.1. Optimal sequencing

In Section 2, we introduced IM and AM as mechanisms for activating futurability. For clarity, in this discussion FD refers specifically to the process of becoming imaginary future people, designing a future society, and creating a future history to reach that vision. We now examine how FD interacts with PrD and PaD when implemented in sequence.

Nakagawa (Reference Nakagawa2024) has investigated optimal sequencing of these three design approaches. The most common sequence – Present, Past, Future – creates a progressive expansion of temporal perspective. This sequence creates a deliberate cognitive journey: participants first consider issues from their immediate perspective (PrD), then evaluate historical decisions (PaD), and finally imagine future generations’ viewpoints (FD).

This sequencing produces observable transformations in participants’ thinking. After experiencing all three stages, participants typically notice significant differences between their initial perspectives (PrD) and their imaginary future perspectives (FD). This cognitive dissonance becomes a catalyst for integrative thinking, as participants work to reconcile these different temporal viewpoints internally.

5.2. Alternative approaches

Alternative approaches have been explored. One variation involves separate groups for current and imaginary future generations (Hara et al., Reference Hara, Yoshioka, Kuroda, Kurimoto and Saijo2019; Saijo, Reference Saijo and Saijo2020a). While this approach can generate creative tension between perspectives, it may also lead to adversarial dynamics where groups struggle to reconcile their fundamentally different temporal viewpoints. The current generation tends to prioritise immediate concerns, while imaginary future generations advocate for longer-term considerations, often resulting in deadlocked discussions. By contrast, when individual participants experience all three design stages, they internalize and reconcile these different temporal perspectives within themselves (Hara et al., Reference Hara, Kitakaji, Sugino, Yoshioka, Takeda, Hizen and Saijo2021; Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Nakagawa and Saijo2024), potentially producing more integrated solutions that harmonize short and long-term priorities.

Research also indicates that sequencing affects outcomes. When the order is changed to Past, Present, Future, participants’ present-focused thinking (PrD) becomes more future-friendly compared to when PrD precedes PaD. This suggests that historical evaluation prepares participants for future-oriented thinking by expanding temporal awareness (Nakagawa, Reference Nakagawa2024).

The implementation of these design sequences faces practical challenges. Time constraints often necessitate prioritising certain stages over others – frequently leading to the omission of PrD while retaining PaD and FD, or in some cases implementing only FD. The role of facilitators also deserves careful consideration. While facilitators ideally maintain neutrality, experience shows they may inadvertently influence discussion content and direction. Some FD practitioners therefore minimize facilitator involvement to prevent such steering, though this approach varies depending on the implementing organization’s previous experiences and preferences. For example, Yahaba Town had been training many of its staff as facilitators even before it started FD, so it was natural for them to be used in FD as well. The selection of appropriate historical examples for PaD exercises is another important factor affecting outcomes.

6. Three abilities and three designs

Having defined three abilities and their corresponding design approaches, we now examine their interrelationships and mutual influences. This analysis reveals complex interconnections that go beyond simple one-to-one correspondences between abilities and designs.

Regarding presentability, as outlined in Section 3, direct activation remains challenging. Traditional PrD approaches, which focus on present circumstances without temporal perspective shifts, do not effectively activate this ability. Similarly, conventional policy mechanisms like income redistribution may address symptoms of present failures without activating the underlying ability to prioritise others’ happiness over immediate gains.

Futurability, by contrast, can be activated through specific mechanisms like IM and AM, as demonstrated in multiple experiments. Most intriguingly, evidence suggests that activating futurability can indirectly enhance presentability – creating a positive spillover effect between temporal perspectives. In Yahaba, participants who experienced IM demonstrated increased ‘compassion’ for current low-income residents and developed more creative housing solutions (Saijo, Reference Saijo2025). This finding suggests a novel mechanism whereby adopting future perspectives may enhance compassion for present others – a relationship that remains underexplored in existing temporal psychology and empathy research, representing a promising avenue for future investigation.

Similarly, pastability appears to enhance both presentability and futurability when activated through PaD. Nakagawa et al. (Reference Nakagawa, Kotani, Matsumoto and Saijo2019a) found that participants who evaluated past decisions demonstrated increased capacity for future-oriented thinking in subsequent exercises. This suggests a potential virtuous cycle where historical perspective strengthens both present and future orientation.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the relationships between the three abilities and designs. The diagram should be interpreted as follows:

Figure 1. Three abilities and three designs.

1. Starting point (left): The human subject begins with minimal activation of presentability, pastability, and futurability (represented by small cylinders). The connecting lines between abilities indicate their inherent interdependence – these are not separate capacities but interrelated aspects of temporal cognition.

2. Design sequence (horizontal arrows): The arrows represent the deliberate application of design interventions in sequence:

o Present Design primarily targets presentability

o Past Design then activates pastability

o Future Design finally activates futurability

3. Cross-activation effects (vertical changes in cylinder heights): Each design intervention increases its corresponding ability while also influencing the others to varying degrees. This creates a cascading effect, where

o Present Design slightly increases presentability and futurability

o Past Design significantly increases pastability while further enhancing presentability and futurability

o Future Design maximises futurability while sustaining growth in the other abilities

4. Final state (right): The fully developed state shows all three abilities activated, with futurability reaching its highest level – representing the intended outcome of the complete sequence.

This visualisation helps explain why the sequence of designs matters and how each intervention builds upon previous ones to create cumulative effects. While empirical research confirms these relationships, their precise mechanisms require further investigation.

Note that higher levels of the three abilities, as shown in the right side of the figure, can expand a person’s time and space axes, allowing for integrated thinking.

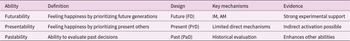

Table 2 provides the summary of three abilities and design approaches.

Table 2. Summary of three abilities and three designs

7. How the future design process should work

As illustrated in Figure 1, the FD Process can be created by focusing on the three abilities (presentability, pastability, futurability) and determining the flow of the three designs (Present, Past, Future), along with participant selection, nature of deliberation, and result utilisation. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020) evaluates various forms of deliberations, including citizens’ assemblies and mini-publics, according to three criteria: representativeness (randomness), deliberation, and impact. This evaluation framework, called a deliberative process, can be created from each of these positions. Since the OECD includes mini-publics in the category of citizens’ assemblies, we compare citizens’ assemblies and FD, paying close attention to their different approaches to participant selection.

7.1. Participant selection considerations

The principle of citizens’ assemblies is that participants in deliberations are basically selected at random (Curato & Farrell, Reference Curato and Farrell2021; OECD, 2020), ensuring the legitimacy of the participants, which is crucial for maintaining inclusiveness and equality in a democracy (Landemore, Reference Landemore2020).

In contrast, FD does not insist on randomly selecting participants, primarily because it is impossible to randomly select people from non-existent future generations. However, selecting only volunteers does not guarantee legitimacy either. In Yahaba’s comprehensive planning, the visions proposed by participants acting as imaginary future generations were not directly adopted as the town’s future vision (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Nakagawa and Saijo2024). To address this legitimacy issue, they voted on specific tactical proposals that aligned with the town’s strategic goals rather than adopting volunteers’ entire vision wholesale. This approach balanced creative input from imaginary future generation participants with democratic accountability to the broader community.

7.2. Expanding applications

FD also proposes that world leaders, such as the G7, allocate time in their meetings to discuss issues as imaginary future leaders (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Kobayashi, Jimbo, Yamashita, Yoshioka and Saijo2023; Saijo et al., Reference Saijo, Shrivastava, Setälä, Schmidpeter and Islam2022). Since these leaders are elected by their respective countries, they have a form of legitimacy. As imaginary future leaders, they could envision themselves in the year 2050, considering a vision that includes peace, drawing a future history to achieve that vision, and determining what actions should be taken now.

Although such discussions have not yet been held, they would be possible if we relaxed the randomness requirement in participant selection, thereby opening up the possibilities for FD to be used in international organisations, national and local parliaments.

The integration of FD with existing democratic institutions presents both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, FD could complement representative democracy by incorporating future generations’ perspectives into current decision-making. On the other hand, questions of implementation, including who organises FD processes, how outcomes are incorporated into policy, and what mechanisms ensure accountability, require careful consideration. Additionally, power dynamics may influence whose imagined futures receive priority, necessitating thoughtful design to ensure diverse perspectives are honoured.

8. Conclusion

This paper has developed a comprehensive framework integrating three human abilities – futurability, presentability, and pastability – with corresponding design approaches. By synthesising evidence from experiments, practical applications, and interdisciplinary research, we have demonstrated how these abilities function as leverage points for addressing both present and future challenges.

Our analysis reveals both similarities and differences among these abilities. While futurability and presentability share a common structure of prioritising others’ happiness over immediate gains, they differ in temporal focus. Pastability involves a distinct evaluative process directed towards historical decisions, complementing but differing from the other two abilities.

The activation pathways for these abilities exhibit asymmetric properties. Pastability appears most readily activated through PaD approaches. Futurability can be effectively stimulated through IM and other FD mechanisms, particularly after pastability activation. Presentability remains more challenging to directly activate, though evidence suggests it may be indirectly enhanced through futurability activation – creating a potential pathway through temporal perspective expansion.

Emerging evidence suggests that activating futurability may indirectly activate presentability (Shahrier et al., Reference Shahrier, Kotani and Saijo2024). This points to a potentially fruitful avenue for future research. It suggests that to activate presentability and address present issues such as disparities and inequalities, an indirect route, involving designing mechanisms to realise pastability and futurability, rather than directly targeting presentability, may be more effective.

One such indirect method is the proposed Future Design Linkage (Saijo, Reference Saijo and Saijo2020a), which involves individuals from other regions acting as imaginary future generations to help solve a region’s present problems. While promising, the effectiveness of this approach in activating presentability in problem areas requires further investigation.

The FD approach shares similarities with the ‘inner transformation’ approach, which emphasises complementing outward-looking science and technology with inward-looking psychological, cultural, artistic, and spiritual aspects of human life (Wamsler et al., Reference Wamsler, Osberg, Osika, Herndersson and Mundaca2021; Woiwode et al., Reference Woiwode, Schäpke, Bina, Veciana, Kunze, Parodi and Wamsler2021). It targets ‘inner transformation’ as a highly effective ‘leverage point’ for sustainable change. In this context, FD can be viewed as a paradigm shift to activate ‘futurability’ as a form of ‘inner transformation’.

Several key challenges and future research directions emerge from this analysis. First, while the effectiveness of IM and AM has been demonstrated in specific contexts, their cross-cultural applicability requires further investigation. Cultural variations in temporal perspectives, intergenerational relationships, and decision-making norms may influence mechanism effectiveness. Second, long-term studies are needed to assess whether activated futurability persists beyond initial interventions and translates into sustained behavioural change. Third, scalability remains a critical question – whether mechanisms effective in small-group settings can be adapted for larger institutional contexts.

Future research should focus on further developing mechanisms to activate all three abilities, with special emphasis on presentability. Investigating the indirect activation of presentability through futurability and pastability, exploring the potential of Future Design Linkage in various contexts, and collaborating with fields studying inner transformation to enhance the FD framework are promising research directions that can enhance our understanding of FD and its potential to address complex societal challenges. This will pave the way for more effective and sustainable solutions to our present and future problems.

The introduction of FD to education represents an important development. At Kyushu University, Tsuyoshi Okamoto initially observed in his assigned students that their statements were typically dominated by personal ‘gains and losses’. However, when he experimentally introduced FD methods around 2023, the content changed dramatically, with focus shifting from personal gain to considerations for the future, community, and society.

Based on these promising results, Kyushu University has planned to scale this approach to all approximately 2,700 new students annually. Beginning in the fall semester of 2025, sixty faculty members will implement FD in first-year education after receiving specialized training. This comprehensive approach aims to develop students’ capacity for long-term thinking, enhance their ability to consider multiple perspectives across time, and cultivate responsibility towards future generations. Okamoto has established the Future Design Consortium (https://www.future-design-consortium.org/) to share know-how and enable educational institutions and other organizations to experience FD.

Humans possess a unique capacity: we can mentally project ourselves into the future to evaluate present decisions. Yet we rarely utilise this ability systematically. Could this capacity be what we need to overcome the threats we have created? The transformation towards a society that can activate futurability, presentability, and pastability represents a ‘quiet revolution’ now beginning to emerge.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Julian Cribb and Masako Ichihara for their detailed comments.

Author contributions

T.S. conceptualised the study, developed the theoretical framework, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Financial support

The author acknowledges the research grant from the Japan Centre for Economic Research and JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (24K04798), as well as the workshop support from the Canon Institute for Global Studies.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

This article is a theoretical and review paper. Data from cited experimental studies are available in the respective publications referenced throughout the article.