Introduction

The transformation from industrial to post-industrial knowledge economies challenges welfare states around the globe. As human skills and capabilities are at the centre of the knowledge economy, social policy experts and policymakers have been pushing for an expansion of ‘social investments’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2002; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2017; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012), that is, policies that aim at creating, preserving or mobilizing human skills and capabilities (Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann, Palier and Zollinger2017). Examples of social investment policies are early childhood education and care, education, skill-focused active labour market and conditional cash transfer policies.

Yet, in a time of ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) the expansion of new social policies comes at a price and social investments need to be financed, typically by raising taxation, increasing public debt or retrenching other public spending. Accordingly, policy and fiscal trade-offs have become omnipresent in welfare politics. The politics of trade-offs have been analyzed on the country level (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Huber, Ray, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Jacques, Reference Jacques2020), but how trade-offs are perceived by public opinion remain understudied. Social investments are extremely popular with the general public (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and Nezi2018; Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018). At the same time, however, most citizens also oppose tax hikes, public debt and welfare retrenchment (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2016; Pierson, Reference Pierson2000). In short, citizens tend to demand ‘something for nothing’ (Citrin, Reference Citrin1979).

Under what conditions are citizens willing to accept future-oriented investments, even if these come at a price, that is, imply trade-offs? We argue that political trust, particularly citizens’ trust in and satisfaction with their governments, is a crucial factor in these trade-off contexts. Trust in and satisfaction with government matter because welfare state reforms generate uncertainties and risks among citizens. This is particularly true for future-oriented reforms, that is, for reforms that might require ‘costly action in the present, while the benefits of such action will be slow to arrive, fully emerging only years or decades hence’ (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016, p. 434), as in the case of social investments. While social investments do also have present-day benefits, their main effects are likely to appear only in the more distant future when today's children enter the labour market, whereas their costs are felt immediately.

We argue that trust in and satisfaction with government – two distinct but related dispositions towards the role of governments – can attenuate these uncertainties, as high-trusting individuals are more likely to believe that their governments are ‘doing the right thing’. Moreover, following pioneering work by Hetherington (Reference Hetherington2005) and Rudolph (Reference Rudolph, Zmerli and van der Meer2017), we argue that trust and satisfaction can moderate individuals’ materialistic self-interests and ideological positions: governmental trust and satisfaction increase support for welfare state reform even among the losers of such reforms.

We test these hypotheses using two research designs. First, we exploit several survey experiments included in a representative population survey of almost 9,000 citizens in eight European countries (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and Nezi2018). Second, we replicate the analysis using European Social Survey (ESS) data to show that the findings hold for a larger sample of 22 countries and for all common measures of political trust. The findings strongly confirm our expectations and hold when controlling for rival explanations, such as whether respondents voted for the governing parties. Moreover, a causality test proves that trust and government satisfaction do not automatically increase support for any kind of reforms, but only in scenarios that include future-oriented policy trade-offs.

These findings contribute to several important debates. First, we expand the literature on politics in ‘hard times’ (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Huber, Ray, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) by turning from the macrolevel to the microlevel of individual-level preferences and pointing at the crucial role of trust therein. Second, we contribute to the literature on welfare state reform in post-industrial societies, adding to recently growing scholarship on the microlevel foundations of social investment policies. Third, we speak to the large literature on political trust by showing that trust matters particularly in the realm of policy trade-offs. As trade-offs gain importance in today's policymaking, our study implies that the relevance of political trust will also increase. Finally, we expand the literature on the formation of welfare attitudes in general, by investigating the complex interrelation of materialistic self-interest, ideological standpoints and social capital; in the existing literature these three explanations are still too often unconnected, or even treated as rival explanations.

Under what conditions do citizens accept reforms?

Under what conditions are citizens willing to accept (welfare) reforms, especially when these reforms promise uncertain future returns in exchange for concrete costs in the present? These kinds of policy trade-offs remain understudied so far, as most existing work on social policy attitudes works with ‘unconditional questions’ that measure support for specific policies while disregarding their costs. We know much less about citizens’ preferences in more realistic trade-off scenarios (for recent exceptions and contributions, see Armingeon & Bürgisser, Reference Armingeon and Bürgisser2020; Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Borsch-Supan, Tabellini, Moene and Lockwood2001; Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018).

We argue here that political trust in and satisfaction with the government are crucial, but hitherto neglected factors shaping citizens’ attitudes towards (future-oriented and uncertain) welfare state reforms. The limited existing work on trade-offs so far focuses on materialistic self-interest and ideological orientations, but has not systematically analyzed the role of trust and government satisfaction yet. Vice versa, a sizable amount of scholarship on political trust has analyzed the measurement and determinants of political trust (for a recent overview see Citrin & Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018), but focused less on the effects of political trust on temporal trade-off decisions (Kumlin & Haugsgjerd, Reference Kumlin, Haugsgjerd, Zmerli and van der Meer2017; but see: Harring, Reference Harring2016; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1999; Scholz & Lubell, Reference Scholz and Lubell1998; Konisky et al., Reference Konisky, Milyo and Richardson2008). Following Breustedt (Reference Breustedt2018, p. 15) we conceive of political trust as ‘people's positive anticipatory expectation that, despite uncertainty, the conduct of the political trustee in question will be in line with their normative expectations’.

In our endeavour, we can build on a few existing studies on the relationship between political trust and citizens’ social policy preferences, which have – however – produced mixed and inconclusive results: While Jacoby (Reference Jacoby1994) and Chanley et al. (Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000) found that trust affects welfare state support in the United States, Edlund (Reference Edlund1999) and Svallfors (Reference Svallfors1999) were unable to replicate this in a country-comparative sample. Aiming to reconcile these contradictions, more recent contributions have shifted focus to the question of under what conditions trust matters. Hetherington (Reference Hetherington1999, Reference Hetherington2005; Hetherington & Globetti, Reference Hetherington and Globetti2002) showed that trust matters when policy proposals affect citizens’ self-interest, for example, imposing more costs than benefits on them, and Rudolph and Evans (Reference Rudolph and Evans2005) found that trust does not moderate materialistic costs alone, but also ‘ideological costs’. Policy reforms can be ideologically costly in the sense that individuals might have to ‘sacrifice ideological principles’ (Rudolph & Evans, Reference Rudolph and Evans2005, p. 660). Gabriel and Trüdinger (Reference Gabriel and Trüdinger2011) continued along these lines, showing that trust can work as a cognitive heuristic when uncertainty about reforms is high.

Most of these studies have, however, concentrated on single countries (mostly the United States) and only explored observational data in correlational analyses that do not allow for causal interpretation. What is more, these arguments have not yet been connected with the burgeoning literature on the politics of trade-offs despite the fact that trade-offs have become omnipresent (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Huber, Ray, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) and political trust should be even more important when costs and benefits are explicit and visible and when citizens cannot have ‘something for nothing’ (Citrin, Reference Citrin1979). A prime example should be policy trade-offs between future-oriented social investment policies and present-day costs, as social investments by definition take a long-term perspective and therefore include large uncertainties and risks (another example might be future-oriented environmental policies). Accordingly, trust should be highly relevant as countries seek to transition from industrial into post-industrial knowledge economies. We develop this argument in the following.

Why governmental trust and satisfaction affect support for future-oriented welfare state reforms

Our core argument is that individuals’ trust in and satisfaction with their governments affects their preferences towards future-oriented welfare state reforms – such as the expansion of social investments – in two ways: Trust and satisfaction exercise a direct effect as well as interaction effects by moderating the effect of self-interest and ideological standpoints.

Our starting point is that while every political reform implies some uncertainties and risks for citizens, this is especially true for future-oriented reforms, that is, reforms whose main consequences are expected to materialize in the more distant future but whose costs might appear already here-and-now (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011, Reference Jacobs2016). The recalibration of welfare states from a traditional model centred on compensatory social policy towards a ‘social investment’ model (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2002; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2017; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012) is a good example. Social investments by design entail several types of uncertainty and risk. First, the future socioeconomic outcomes of the reforms are unknown and can only be estimated with considerable uncertainty. Investing in (early childhood) education, for example, might increase the cognitive and non-cognitive skills and capabilities of children, but whether and how these investments pay off economically – for example in better labour market performance, higher growth and higher tax revenues – only becomes apparent when the current generation enters the labour market, that is, 20–30 years after the investments. While paying the costs would thus be necessary and visible today, the main (positive) outcomes were only to materialize in the future – a typical ‘time-inconsistency problem’. Of course, there can also be shorter term benefits, such as the effects on the children's parents (e.g., facilitated work-life reconciliation), but the main effect is usually argued to run via the children's enhanced skills and capabilities, which materialize in the future.

Second, social investments are uncertain and risky because during the long investment process the governments will probably change, so there is some uncertainty to what degree future governments will remain committed to the implementation of these goals, that is, problems of agency loss (Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2017).

At the same time, the reform costs are immediate and visible. In an age of ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) expanding public expenditure, like social investment, is only possible at the expense of other public policies or at fiscal expenses, that is, by raising taxes or public debt. These trade-offs have become more pressing than in the past both because economic constraints and vested interests constrain policymakers’ room for manoeuvre (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Huber, Ray, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Jacques, Reference Jacques2020). Furthermore, increasing taxes or public debt as well as cutting back spending are deeply unpopular with voters (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2016; Pierson, Reference Pierson2000; Stix, Reference Stix2013). Elected politicians are thus in a politically difficult terrain. Consequently, the recalibration of welfare states from a consumption-orientation towards a social investment paradigm provides an ideal testing ground for arguments about the role of political trust for citizens’ preferences.

Moreover, it can also be shown formally that uncertainty (over the distributive outcomes of a reform) is a crucial factor in understanding whether policy reforms fail or succeed, resulting in bias towards the status quo (Fernandez & Rodrik, Reference Fernandez and Rodrik1991).

We argue that trust and government satisfaction can mitigate the (perceived) uncertainty and risks of such future-oriented reforms. While we certainly do not equate political trust and government satisfaction (see the extensive literature e.g., by Breustedt, Reference Breustedt2018; Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; Marien, Reference Marien, Zmerli and Hooghe2011; Norris, Reference Norris, Zmerli and van der Meer2017; PytlikZillig & Kimbrough, Reference PytlikZillig, Kimbrough, Shockley, Neal, PytlikZillig and Borstein2016; van der Meer & Ouattara, Reference Van der Meer and Ouattara2019; Zmerli & van der Meer, Reference Zmerli and van der Meer2017), we regard satisfaction with and trust in the government as two distinct, but highly related phenomena that – for our purpose – work in the same way: Our notion is that citizens, who trust and are satisfied with their government, will also believe that the present and potential future governments will be implementing the best possible reforms and will act on their behalf. In other words, when individuals have to form an opinion about (complex) policy issues under uncertainty, trust and government satisfaction are activated as heuristics (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005).

This reasoning and its cognitive mechanisms can be backed by psychological research showing that humans often rely on heuristics to facilitate and speed up challenging cognitive decision-making processes, especially in situations that contain complexity, uncertainties, risks and imperfect information (Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier, Reference Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier2011). Observational and experimental evidence (Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Alhakami, Slovic and Johnson2000; Slovic & Peters, Reference Slovic and Peters2006) shows that when people's feelings towards an activity are favourable, ‘they tend to judge the risks as low and the benefits as high’ (Slovic & Peters, Reference Slovic and Peters2006, p. 323). That is, when citizens have positive evaluations and feelings towards their governments, they should be more likely to accept their actions, even if they imply significant costs in the short term. Hence, we argue that feeling satisfied and confident about the government – that is, both government satisfaction or trust in government – increases people's support of future-oriented (welfare) policy reforms. At the same time, we would not expect effects on support for any kind of policy reform. If a reform does not include trade-offs, or if the trade-offs do not contain a future-orientation, we would expect a much smaller effect of trust – if any at all. Thus:

Hypothesis 1 (direct effect): The more individuals trust in (are satisfied with) their government, the more they are likely to accept future-oriented welfare reforms at the expense of present-day costs.

We, moreover, expect that the (perceived) costs and benefits as well as the uncertainty of reforms are not equal for all citizens, but dependent on their respective labour market situation and their status as welfare recipients. We know from cognitive psychology and behavioural economics that humans value losses more than gains, tend to be risk-averse and use heuristics to make decisions in these scenarios (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). We thus expect that trust and government satisfaction should particularly matter for those with a lot to lose from a specific reform (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005; Hetherington & Globetti, Reference Hetherington and Globetti2002), that is, those for whom the reforms would imply clear and visible personal costs. Reform losers who positively evaluate the government might believe that the government will find a way to satisfy their needs, so that in the end everybody, including themselves, will be better off. In other words, trust and government satisfaction increase support for welfare state reform even among those groups that lose from the proposed reform.

When expanding social (investment) policies, funding can come from three main sources: cutbacks in other spending areas, taxation or debt.Footnote 1 When financed by cutbacks, policy trade-offs emerge. The obvious losers are recipients of the programs that would be retrenched. The largest recipient groups of traditional compensatory policies are pensioners and the unemployed. Both groups would lose from a reduction in compensatory spending. Thus, we expect that if welfare reforms come at the expense of pensions, pensioners are more opposed, but their opposition softens the higher their level of trust or government satisfaction. Similarly, the unemployed would oppose cuts in unemployment benefits, but should be more likely to accept such retrenchment in favour of new investments when they are satisfied with and trust the government.

When, in contrast, funding for welfare expansion comes from increasing taxation or public debt, fiscal trade-offs emerge. We know that support for taxes and public debt decreases by individual income, as richer individuals face higher materialistic costs (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2016; Stix, Reference Stix2013). Objectively, this makes sense, given that – despite several changes and reforms – the tax systems of all countries in our sample are progressive (OECD, 2021). In line with this, while people in general are not very good at estimating precise levels of current taxation and debt, they do perceive the tax systems as progressive (Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2020). We therefore expect that richer citizens are more opposed to taxation and debt. Yet, we argue that trust and government satisfaction can mitigate this opposition:

Hypothesis 2 (materialistic costs effect): The higher individuals’ trust in (satisfaction with) government, the more likely they are to support welfare reforms even if these imply materialistic costs for themselves. That is, trust (government satisfaction) alleviates the effect of materialistic self-interest on support of costly reforms.

Finally, we agree with Rudolph and Evans (Reference Rudolph and Evans2005, p. 660) that policy reforms can also induce ‘ideological sacrifices’ in citizens, when they have to ‘sacrifice ideological principles’. We expect that trust and government satisfaction matter more for those individuals, who have to sacrifice ideological core beliefs. In our trade-off scenarios, two ideological sacrifices are possible. First, expanding welfare benefits for one group at the expense of another (e.g., cutting unemployment benefits or pensions to finance social investment) implies ideological costs for left-wing individuals, because they support benefits for all under-privileged groups (Iversen & Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001). We argue that trust and government satisfaction matter here, as these costs can be mitigated if citizens believe their government is ‘doing the right thing’.

Vice versa, when proposed welfare reforms imply fiscal trade-offs, that is, increasing taxes or public debt, ideological costs will arise for right-wing individuals. Conservatives would ideologically prefer decreased public spending (Iversen & Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001), lower taxation (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2016) and lower public debt (Stix, Reference Stix2013). Again, these costs could be moderated. We thus expect:

Hypothesis 3 (ideological costs effect): Trust in and satisfaction with government mitigate the effect of ideology on social policy preferences, that is, ideological differences become smaller at higher levels of governmental trust and satisfaction.

Research design

We test our theory using two large representative public opinion surveys. In Study 1, we employ three survey experiments in a representative sample in eight European countries, which allow for causal interpretation. In Study 2 we show with ESS data that these findings also hold for a broader country group (22 countries) and for all common operationalizations of political trust and government satisfaction. That is, while Study 1 provides confidence in the internal validity of our results, Study 2 explores their external validity.

Study 1: Three survey experiments in eight countries

We test our propositions with a representative survey in eight European countries (see Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and Nezi2018 for details of the survey). The unique advantage of this survey is that it allows measuring attitudes towards policy and fiscal trade-offs at the individual level and includes survey experiments that allow for causal interpretation. Eight European countries are selected as representatives of different welfare state regimes: Denmark, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The survey was conducted by a professional survey institute using computer-assisted telephone interviewing. After a pre-test and careful translation-checks, the actual fieldwork took place in 2014. The target population is adults (age ≥ 18). The number of interviews differed slightly between countries (1,000–1,500) to acknowledge differently sized target populations (see Appendix Table A.1). The average response rate was 30 per cent, which is satisfactory (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and Nezi2018). Compared with the high-quality sample of the European Social Survey (ESS), we find few discrepancies on key variables, confirming the high data quality (see Appendix Table A.2). The average interview length was 25 minutes.

Constructing welfare reform scenarios

We designed several fictive but realistic welfare state reform scenarios that include different policy and fiscal trade-offs. We focused on the most typical trade-offs, that is, social investment comes at the expense of (1) other social policies, (2) taxation or (3) debt. Citizens seem well aware of these trade-offs and find them realistic: ‘no less than eighty percent of the respondents agree that “the limits of taxation have been reached”, and over two thirds of respondents agree that “social policy improvements for one social group sooner or later come at the expense of other social groups”’ (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021, p. 2).

Each respondent faced three trade-off scenarios to measure their support for social investments under different kinds of constraints. In order to capture the effects as cleanly as possible, we used experimental split sample designs where respondents are randomly assigned to different groups. Balance tests reveal no significant differences in the relevant variables across subgroups (Appendix Table A.3).

In a first scenario, the dependent variable is respondents’ support for public spending on education – a paradigmatic social investment policy:

Split 1: ‘The government should increase spending on education.’

Split 2: Split 1 + ‘…, even if that implies higher taxes.’

Split 3: Split 1 + ‘…, even if that implies a higher public debt.’

Split 4: Split 1 + ‘…, even if that implies cutting back spending in other areas such as pensions.’

Respondents could ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’, which we dichotomized in general support (1), versus opposition or choosing the middle category (0) to facilitate interpretation.Footnote 2 Two residual categories (‘don't know’ and ‘no answer’) are coded as missings. To reiterate our theoretical expectation, we would expect trust and government satisfaction to increase support particularly for Split 2 and 4 as these expand future-oriented social investments at the expense of present-day costs. Split 1 does not entail trade-offs and Split 3 includes a ‘future benefits versus future costs’ trade-off.

In a second scenario, we focused on policy trade-offs between two ideal-typical social investment policies and two ideal-typical compensatory social policies. Respondents were again randomly assigned to four groups:

‘Imagine the government plans to…’

Split 1: ‘… increase spending on education by 10% and wants to finance this by cutting the benefits for the unemployed.’

Split 2: ‘… increase spending on education by 10% and wants to finance this by cutting old age pensions.’

Split 3: ‘… enact reforms involving a 10% increase in the budget for financial support and public services for families with young children, and wants to finance this by cutting the benefits for the unemployed.’

Split 4: ‘… enact reforms involving a 10% increase in the budget for financial support and public services for families with young children, and wants to finance this by cutting old age pensions.’

Again, respondents had to indicate their support on the five-point Likert scale, which we dichotomized in support versus opposition defined as above. We expect trust and government satisfaction to increase support for all four scenarios, as they all expand future-oriented social investments at the expense of present-day social compensation.

Finally, we designed a third set of policy trade-offs to test our proposition that trust and government satisfaction matter particularly for future-oriented reforms, rather than increasing support for any kind of welfare reform. A first group read:

Split 1: ‘To be able to finance more spending on education and families, the government should cut back on old age pensions and unemployment benefits.’

A second group read vice versa:

Split 2: ‘To be able to finance more spending on old-age pensions and unemployment benefits, the government should cut back spending on education and families.’

The final trade-off is important because it serves as a causality test for our arguments that trust and government satisfaction should be particularly important in trade-offs with future and uncertain outcomes (Split 1), while it should not matter in Split 2.

Measuring trust in and satisfaction with government

A broad literature discusses the meanings, measurements and the dimensionality of political trust and government satisfaction (e.g., Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; Marien, Reference Marien, Zmerli and Hooghe2011; Norris, Reference Norris, Zmerli and van der Meer2017; Zmerli & van der Meer, Reference Zmerli and van der Meer2017). Discussion is ongoing whether political trust is a uni- or multidimensional phenomenon (Breustedt, Reference Breustedt2018; PytlikZillig & Kimbrough, Reference PytlikZillig, Kimbrough, Shockley, Neal, PytlikZillig and Borstein2016; van der Meer & Ouattara, Reference Van der Meer and Ouattara2019). For our purpose it suffices to say that while we would not equate all measures of political trust and government satisfaction, they are for our present purpose functionally equivalent. That is, we conceive of different measures of political trust and government satisfaction as distinct, but related phenomena. More specifically, we are less interested in whether individuals support their political system in general, but whether they believe that their government is doing a good job in shaping policy-outputs, hic-et-nunc and in the future. The measure we employ in Study 1 focuses on respondents’ satisfaction with their government. Abundant studies have shown that satisfaction with the current government is a very good predictor of trust in future governments and future government action, as citizens’ assessment of government performance shapes their trust in future governments, too (Chanley et al., Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Citrin, Reference Citrin1974; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005). We used the most recognized question wording in the literature (e.g., used in the ESS): ‘Now thinking about the [COUNTRY] government, how satisfied are you with the way it is doing its job?’ Respondents could chose: ‘Very satisfied’, ‘satisfied’, ‘neither satisfied nor unsatisfied’, ‘unsatisfied’, ‘very unsatisfied’ or a residual category (‘don't know’ or ‘no answer’).

Given limited question time, our survey in Study 1 does not include other measures of political trust. Yet, we show in Study 2 that our findings replicate for all other common measures of political trust. It also deserves mentioning that the trust questions were asked before measuring the dependent variables; therefore, reversed causality is not a concern.

Methods

In the first step of the analysis, we estimate the effect of government satisfaction on support for each individual reform scenario (10 in total), using multilevel logistic regressions with country-level random intercepts. The results are highly similar when using country fixed effects (see Robustness).

In a second step, we explore the theorized interactions. To do this, we pool the answers of all fiscal trade-offs (i.e., scenarios 2 and 3) and of all policy trade-offs (scenarios 4–9).Footnote 3 This procedure allows us to use the largest possible number of observations (see Rehm et al. (Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012) for a similar approach). As each respondent answered three questions, we have up to 14,958 observations here. Due to the split sample design, the number of observations becomes small for some combinations,Footnote 4 so pooling all questions gives us more statistical leverage.Footnote 5 To acknowledge the fact that the pooled observations are not independent, we use three-level logistic regression models with answers nested in individuals and individuals nested in countries.Footnote 6 Moreover, we add dummy variables for the respective trade-off scenarios.

Concomitant variables

We run models with and without a range of potential concomitant variables, which could also be associated with people's preferences towards welfare state reform under trade-off conditions (Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Borsch-Supan, Tabellini, Moene and Lockwood2001; Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018): AGE, GENDER, HIGHEST EDUCATIONAL DEGREES (basic education, higher education, vocational education), HOUSEHOLD INCOME (in country-specific quintiles), CURRENT LABOR MARKET SITUATION (working full-time, being unemployed, student, retired, residual category), SUBJECTIVE RISK OF BECOMING UNEMPLOYED, HOUSEHOLD SIZE ( = whether the household is larger than a single adult) and whether respondents have CHILDREN LIVING IN THE HOUSEHOLD.

In additional models we also control for respondents’ IDEOLOGICAL LEFT-RIGHT POSITION and stated ELECTORAL SUPPORT FOR THE INCUMBENT PARTIES. The latter two are important to ensure that we control for aspects of our government satisfaction measure that are related to the respondents´ (ideological) distance from the current government, as government satisfaction and political trust tend to be higher among government voters (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005). Including attitudinal variables on both sides of regression equations is controversial because these variables control away some of the effects of the variables of theoretical interest and because they generate endogeneity problems. For these reasons, we present models with and without the attitudinal variables.Footnote 7 Appendix Table A.4 lists the question wordings and descriptive statistics.Footnote 8

Findings

Direct effects

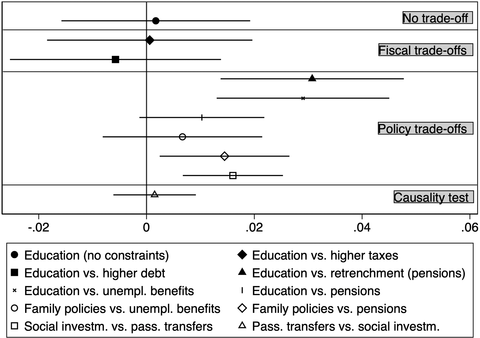

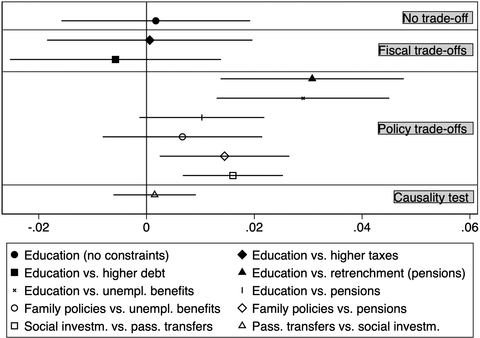

Figure 1 shows average marginal effects of government satisfaction on support for the 10 reform scenarios (regression tables in Table A.5). We highlight four important findings:

Figure 1. Direct effects of government satisfaction on attitudes towards 10 different reform scenarios. Notes: Average marginal effects and 95 per cent-confidence intervals. Multilevel random country-intercept logistic regressions, maximum likelihood estimations.

First, as expected, we do not find that government satisfaction matters in the control group reading the unconditional question frame without trade-offs: When increasing education spending does not imply any costs, support is very high among many citizens and not systematically higher among individuals with positive evaluations of government.

Second, we find positive effects for all policy trade-offs where future-oriented policies come at the expense of hic-et-nunc costs. The effects are significant at the 95% level for four of the six models. For the other two (‘raising education by 10 per cent at the expense of pension cutbacks’ and ‘families versus unemployment benefits’), government satisfaction also exhibits a positive effect, but these effects are only significant at lower levels, arguably because these questions are formulated in a more concrete and less vague and ambiguous way.Footnote 9 The effect of government satisfaction is strongest for the ‘education versus pensions’ trade-off. A one-unit change in government satisfaction increases reform support by 3.07 percentage points. Overall, these findings confirm Hypothesis 1.

Third, we do not find that government satisfaction matters for either of the two fiscal trade-off scenarios (social investment vs. taxes or debt). As theorized, a potential reason for the ‘investment versus debt’ trade-off might be that both are future-oriented, as the costs of public debt also do not materialize hic-et-nunc, but rather add to future costs. Yet, this reasoning cannot explain the non-findings for the ‘investment versus taxation’ trade-off. It seems more plausible to take-away from these findings that fiscal trade-offs and policy trade-offs seem to follow different logics, as government satisfaction matters in the latter but not in the former. This deserves further exploration. We return to this finding when exploring conditional interaction effects below.

Fourth, and most importantly, the results of our causality test (trade-off 3) are strongly in line with our expectations: Government satisfaction significantly increases support for the ‘social investment versus social compensation’ trade-off, but vice versa, there is no significant effect when trade-offs would cut social investments to increase compensatory spending. Thus, it is not the case that the acceptance of trade-offs in general depends on respondents´ government satisfaction. As theorized in Hypothesis 1, government satisfaction matters only for future-oriented reforms with uncertain outcomes.

Interaction effects

Does government satisfaction also have the theorized interaction effects by moderating respondents’ self-interest (Hypothesis 2) and ideological standpoints (Hypothesis 3)? Given the above non-finding for the fiscal trade-offs, we concentrate on the moderating role of government satisfaction for policy trade-offs and only briefly discuss results for the fiscal trade-offs (full models in Tables A.14 and A.18 and Figure A.3).

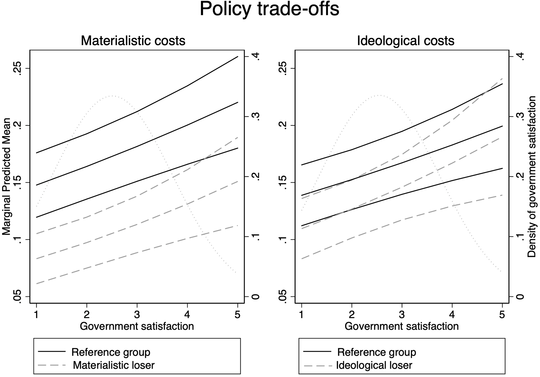

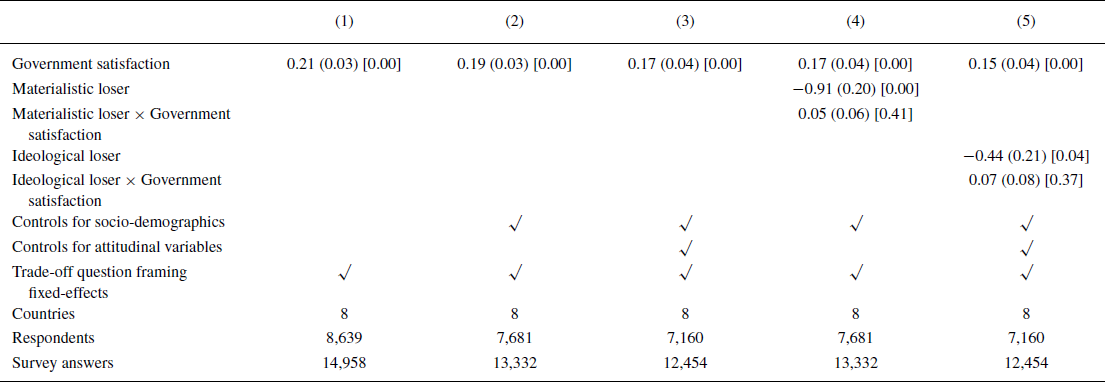

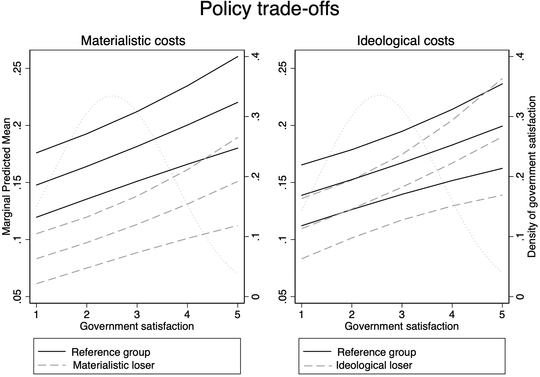

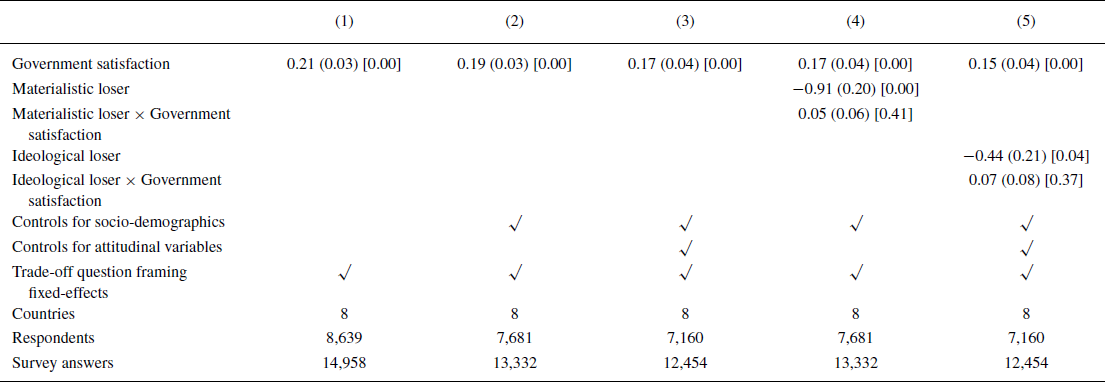

Table 1 shows the main results for the pooled policy trade-offs (full regression table in Appendix Table A.6). We present several models with different numbers of concomitant variables: Model 1 includes government satisfaction as the only predictor variable; Models 2 and 3 add additional socio-demographic and attitudinal concomitant variables, respectively. Models 4 and 5, finally, test for the presence of the theorized interaction effects between government satisfaction and self-interest, respectively ideology. Figure 2 plots the interaction effects as predicted probabilities.

Figure 2. Interaction effects between government satisfaction and materialistic costs (left side) and ideological costs (right side). Notes: Predicted probabilities and 95 per cent-confidence intervals, based on Table 1, Models 4 and 5. Density plots (in light grey) show the distribution of observations.

Table 1. Support for welfare reforms in policy trade-offs

Logistic multilevel models, random intercepts at the individual- and the country-level; maximum likelihood estimates. Standard errors in parentheses. p-values in brackets.

Confirming the results of Figure 1, we find a direct effect of government satisfaction on reform support under policy trade-offs. The effect is significant at the 99 per cent level and substantial in size. In Model 1, a one-unit increase in government satisfaction is associated with an increase in support for social investment reforms by 1.90 percentage points. The difference between a typical low-satisfied and a high-satisfied person amounts to up to 7.92 percentage points. The effect of government satisfaction decreases only slightly once we add concomitant variables in Model 2: Here, the difference in reform support is 7.10 percentage points. This means that an individual's socio-economic position explains only a (minor) share of the effect of government satisfaction on reform support. The same applies when adding ideological concomitant variables in Model 3. Here, the difference between a typical low-satisfied and a high-satisfied individual is 6.55 percentage points. In sum, the effect of government satisfaction on reform support involving trade-offs is substantial in size and robust across model specifications.

Materialistic costs

Next, we test the theorized interactions, focusing on the policy trade-offs as discussed above. We start by analyzing interactions between government satisfaction and self-interest (Hypothesis 2). Reforms are more costly for some than others, but positive feelings towards government should mitigate these effects. We designed the trade-offs in a way that makes costs and benefits very visible for respondents. A dummy variable, MATERIALISTIC LOSER, captures whether respondents are likely to experience materialistic costs from the proposed trade-off scenarios: In the trade-offs that expand social investment at the expense of pensions, pensioners and individuals aged 60+ receive the value ‘1’ on the MATERIALISTIC LOSER variable. In the trade-offs that imply retrenchment of unemployment benefits, the unemployed are the clear and visible losers and are thus coded with the value ‘1’ as well.Footnote 10

Model 4 in Table 1 interacts our materialistic loser variable for policy trade-offs with government satisfaction. The results, shown graphically in the left-hand panel of Figure 2, are in line with our expectations (Hypothesis 2): government satisfaction increases reform support even among those individuals who are likely to bear direct material losses associated with the proposed reform scenarios. Moving from the lowest to the highest level of satisfaction increases the support of reform losers by 6.77 percentage points. While support of those individuals with direct materialistic costs is still below the rest of the population, government satisfaction leads individuals towards a more favourable assessment of social investment reforms, even if these reforms imply direct material losses for themselves.

Ideological costs

Does government satisfaction also moderate the role of ideological costs? As theorized (Hypothesis 3), policy trade-offs, that is, here the expansion of social investment at the expense of compensation, bear ideological costs for left-wing voters. Thus, we defined a dummy variable, IDEOLOGICAL LOSER, which takes the value ‘1’ for left-wing respondents in the policy trade-off scenarios.Footnote 11

In Model 5 of Table 1, we interact this ideological loser variable with respondents’ government satisfaction to test whether satisfaction can weaken the effects of ideology on people's support of welfare state reform in the presence of policy trade-offs (Hypothesis 3). The empirical findings, plotted in the right side of Figure 2, support this argument: Government satisfaction moderates opposition by those groups that should be particularly opposed to the proposed reform scenario. For low-satisfied individuals, support for reforms that are at odds with one´s ideological standpoint is 2.92 percentage points lower than in the rest of the (low-satisfied) population and this difference is statistically significant. But government satisfaction is particularly important in moderating the support of this group. At high levels of satisfaction, support among those that should be opposed to reforms thanks to ideological reasons is about the same level as the remaining high-satisfied population. That is, at high levels of government satisfaction, ideological standpoints are muted. Trust effectively mitigates ideologically motivated opposition to reforms.

Fiscal trade-offs

Can we identify a moderating effect of government satisfaction also for the two fiscal trade-offs? Although the direct effects of government satisfaction on reform support were insignificant (Figure 1), government satisfaction might still play a role for reform losers. To test this, we first need to identify the losers in the fiscal trade-offs. The existing literature on preferences towards taxes (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2016) and public debt (Stix, Reference Stix2013) shows that preferences differ systematically by household income, with the highest income groups being most strongly opposed to increases in taxes or debt. Objectively, (almost) all tax systems are progressive (OECD, 2021), even if at different rates, and they are also perceived as such by the public (Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2020). Thus, higher income groups (the highest income quintile) receive the value ‘1’ on the materialistic loser variable in the fiscal trade-off scenarios. Ideological losers in the fiscal trade-offs are ideologically right-wing respondents who would favour to decrease both taxation and debt.

The results in Table A.14 in the Appendix for the two pooled fiscal trade-offs disconfirm the materialistic costs hypothesis, but we can confirm the moderating effect for ideological costs. Moving from the lowest to the highest level of government satisfaction increases the predicted probability of reform support among reform losers by 3.77 percentage points and the difference in support between reform losers and the reference group becomes statistically insignificant at high levels of government satisfaction. Running the models separately for the two fiscal trade-offs (Table A.18 and Figure A.3 in the Appendix) suggests that, in particular, the trade-off involving tax increases seems to follow a different logic than postulated in our theoretical considerations. One possible explanation could be that individuals with high incomes could be less opposed than the literature has suggested to tax increases designated specifically to increases in public education spending (see also Table A.5, Model 2). Accordingly, while we did not find support for a direct effect in the fiscal trade-offs, trust in and satisfaction with the government to some extent still play a moderating role.

Robustness

The results are robust in a variety of tests. First, the results do not depend on the inclusion of specific concomitant variables: We added respondents’ ideological and partisan preferences (Table A.16, Model 1), preferences towards public social spending (Table A.16, Model 2), and whether they voted for the current government. None of these changed our results. In a model without government satisfaction, voting intention for the incumbent government is a strong predictor of reform support (Table A.7, M1), but this effect disappears when controlling for government satisfaction (Table A.6, M3). We run additional models where we interact government satisfaction with voting intention for the incumbent government (Table A.7, M2) finding that the effect of government satisfaction for reform support is strongest for those being in favour of opposition parties. Thus, in particular for those who do not electorally support the current government, government satisfaction appears to alleviate scepticism towards the government´s willingness to pursue social investment reform. Again, this raises the credibility and relevance of our findings since it highlights conditions under which individuals who do not electorally support the government can still accept its policies.

To address potential effect heterogeneity, we run all models by country (Table A.8). The results support our expectations. The main difference is that – because of the smaller number of cases – the effects show lower levels of significance, but reveal a high degree of consistency, except in Germany (see Appendix Table A.8). The results are furthermore robust when using logit regression models with country fixed effects (Appendix Table A.11).

Moreover, we tested for non-linear effects. A Likelihood Ratio test suggests that using a linear measure of government satisfaction is appropriate. Adding a squared term of government satisfaction to the interaction term slightly increases the model fit. However, replicating the interaction models with squared government satisfaction shows a pattern similar to the one from the main analysis. In particular, for materialistic and ideological losers, the effect of government satisfaction is essentially linear (Appendix, Table A.15 and Figure A.1). What these findings do reveal is that differences are particularly pronounced between low- and medium-high levels of trust.

In sum, the results are robust to a range of empirical tests.

Study 2: ESS survey

The survey experiments in Study 1 show strong support for our arguments. Yet, the study has two limitations. First, we were only able to test these propositions in a sample of eight Western European countries, so we do not know whether it also holds in other country contexts. Moreover, Study 1 could only focus on government satisfaction, and thus left open the question of whether the findings depend on this operationalization or also hold for different forms of political trust.

In order to address these limitations, we conduct a second study, using the eighth wave of the European Social Survey (ESS, 2016). Wave 8 is unique because it includes trade-off questions and offers a multidimensional measure of political trust. To foreshadow the results, we will demonstrate that we can replicate the direct effect identified in Study 1 in the sample of 22 European countriesFootnote 12 and that the findings hold for all common measures of political trust.

The survey includes two trade-off questions between future-oriented social investments and present-oriented policies that we use as dependent variables. The survey opens by telling respondents: ‘In the next 10 years the government may change the way it provides social benefits and services in response to changing economic and social circumstances’. A first question focuses on skill-oriented active labour market policies (ALMPs), that is, a typical future-oriented social investment policy, at the expense of present-oriented unemployment benefits, that is, a typical compensatory policy:

‘Now imagine there is a fixed amount of money that can be spent on tackling unemployment. Would you be against or in favor of the government spending more on education and training programs for the unemployed at the cost of reducing unemployment benefit?’

A second trade-off focuses on facilitating reconciliation between work and family life (an explicit social investment policy) versus higher taxation:

‘Would you be against or in favor of the introduction of extra social benefits and services to make it easier for working parents to combine work and family life even if it means much higher taxes for all?’

The answer categories to both questions are ‘strongly against’, ‘against’, ‘in favour’, ‘strongly in favour’, ‘refusal’ or ‘don't know’, which we again dichotomize.

The advantage of these questions is that they provide trade-offs between future-oriented welfare policies and present-oriented benefits for a large set of countries. There are, however, two disadvantages. First, in contrast to Study 1, the questions are not implemented as experiments, that is, all respondents answered both questions, which is less ideal because we lack randomization as well as a control group against which to compare the results. Second, the questions are formulated in a way that does not allow for clearly identified (potential) materialistic winners and losers of the reforms.Footnote 13 We can, however, test the direct effect as well as the hypothesis about the moderation of ideological costs.

The ESS included a well-established battery of questions on political trust. For our purpose, five of these are theoretically most relevant: TRUST IN PARLIAMENT, TRUST IN THE LEGAL SYSTEM, TRUST IN POLITICIANS, TRUST IN PARTIES, as well as GOVERNMENT SATISFACTION. The question wordings and descriptive statistics are listed in Appendix Table A.9.

Methodologically, we use the exact same setup as in Study 1, that is, we run multilevel logit models with country-level random intercepts on the dichotomized dependent variables. The results are highly similar when we use logit models with country fixed effects (Appendix Table A.12).Footnote 14 We include the same control variables as in Study 1. All details can be found in Appendix Table A.9.

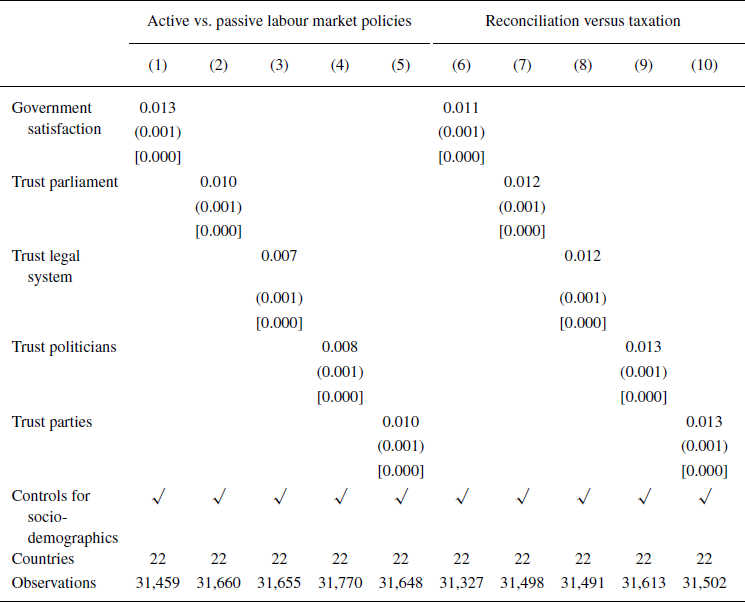

Findings

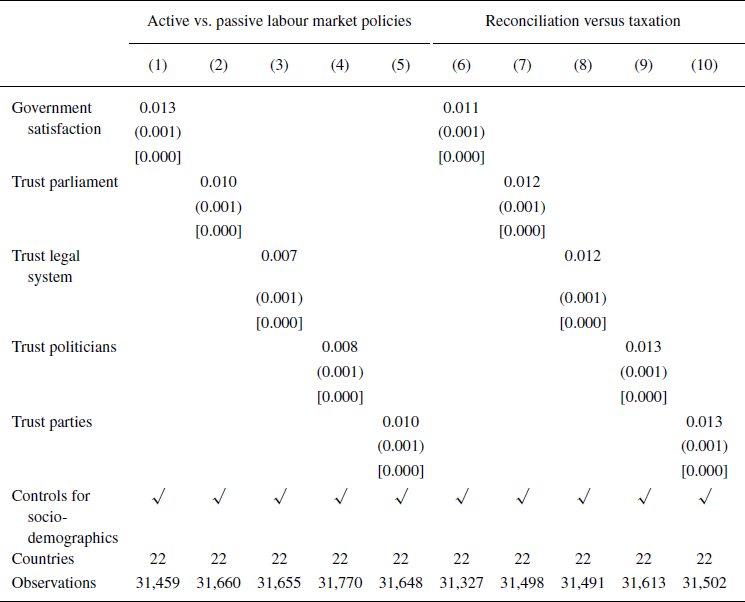

Table 2 displays the main findings. Models 1 through 5 analyze preferences on future-oriented active versus present-oriented passive labour market policies, using different trust measures, and Models 6 through 10 study preferences on the reconciliation versus taxation trade-off. The findings are very clear and consistent: Across all models we find that government satisfaction and political trust – irrespective of the measure – are positively associated with support for future-oriented social investment policies over more present-oriented benefits. Moreover, while there are some smaller differences, the effect sizes are highly similar. These findings confirm the findings of Study 1 and show that the results depend neither on a specific operationalization of political trust, nor on the narrower country sample in Study 1. As theorized, political trust and government satisfaction increase support for future-oriented welfare policies, even if these imply visible costs.

Table 2. Average marginal effects of political trust on support for welfare state reforms, ESS data

Marginal effects, logistic multilevel models, country-level random intercepts. Standard errors in parentheses. Brackets report p-values. Full regression table in Appendix A.10.

We find less support, however, for the hypothesis about trust in and satisfaction with government moderating ideological costs. Given that the first trade-off is a policy trade-off, ideological costs emerge for left-leaning respondents, since they – qua ideological standpoint – would support both policies. In the second, fiscal trade-off, ideological costs emerge for right-leaning respondents. While we do find that trust and satisfaction matter even among ideological losers (see the marginal effects in Appendix Table A.20), only seven out of 10 are significant at conventional levels. Moreover, the interaction effects (see Table A.19) do not support the hypothesis that ideological costs are smaller at higher levels of trust/satisfaction in Study 2. A potential reason is that not only the country sample is more heterogenous in Study 2, but that the policy trade-offs here also different in their redistributive dynamics, which might add additional complexity. Yet, as we cannot test this properly empirically here, we conclude more carefully by saying that Study 2 showed strong support for the direct effect of political trust (irrespective of the operationalization), but with much weaker evidence than Study 1 when it comes to the ideological moderation: While trust/satisfaction matters even among ideological losers, it does not matter especially under losers in Study 2. Future research could explore further how and why the interaction effects potentially differ in different kinds of trade-offs (for example with different distributive dynamics).

Concluding discussion

How can policymakers find public support for welfare state reforms that create significant benefits in the long term, but impose concrete, visible and tangible short-term losses on clearly identifiable groups? We argued and found that political trust and government satisfaction increase support for future-oriented reforms, especially when these reforms entail policy trade-offs. This observation also holds across a variety of different reform scenarios, for various trust measures and for a large set of countries.

This positive effect even exists among those who would incur material losses due to the proposed cutbacks, and it holds among those who are opposed to the reform proposals for ideological reasons. This implies that political trust and government satisfaction can mitigate materialistic and ideological sacrifices of reforms. At high levels of trust, ideological differences in citizens’ attitudes towards welfare reform are even muted (although this mainly appeared in Study 1).

These findings have several important implications. First, our results imply that there is a tight connection between countries’ stock of political trust and policymakers’ room-for-manoeuvre. The higher citizens’ trust in and satisfaction with their government, the more they are willing to accept future-oriented (welfare state) reforms. This means that a shift towards a social investment welfare model is politically more feasible in countries with high levels of trust and satisfaction.

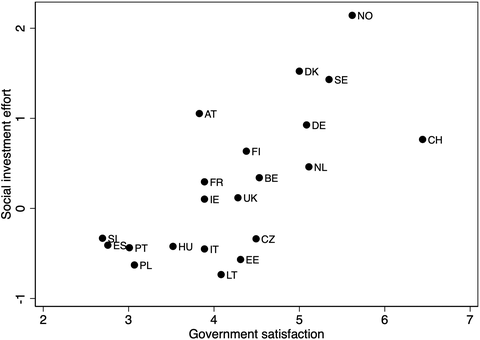

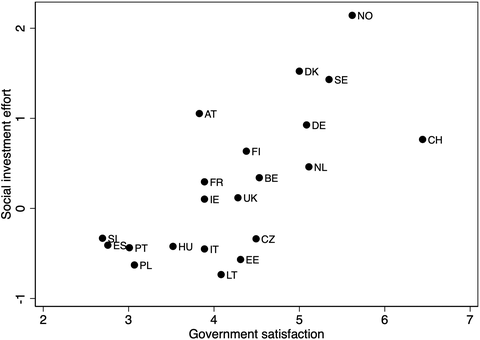

If true, we should see a tight relationship between countries’ level of political trust or government satisfaction and their social investment effort. To explore this, Figure 3 plots countries’ social investment effort (using a measure by Ronchi, Reference Ronchi2016) over their average levels of political trust (using ESS data). We observe a quite tight linear relationship between countries’ stock of government satisfaction and their extent of social investment expansion. While we hasten to say that we would neither argue that countries’ social investment effort is a direct function of their level of government satisfaction nor that government satisfaction or trust are the only or the main factor explaining social investment effort, we do claim that government satisfaction and political trust is one important (and neglected) factor because it provides policymakers with political room-for-manoeuvre to engage in difficult reforms. In this sense, government satisfaction and political trust might be thought of as a necessary condition for social investment reforms.

Figure 3. Countries’ average level of government satisfaction and their level of social investment effort (2014). Notes: SOCIAL INVESTMENT EFFORT is countries’ social investment spending (in constant prices), standardized and deflated by the number of beneficiaries in the respective target populations (Ronchi, Reference Ronchi2016). GOVERNMENT SATISFACTION is the country-mean of government satisfaction using ESS wave 8 (including survey weights). The figure looks highly similar when using other measures of political trust.

Our findings thus help explain why some countries have been able to re-adjust their welfare states to the challenges of the post-industrial knowledge economies more than others. Supporting our reasoning, countries with high political trust levels (Nordic Europe) have already gone the furthest in the direction of social investment policies, whereas countries with lower trust and satisfaction levels (Southern Europe) remain much more consumption-oriented and have not yet met the demand to cover the rising new social risks. Moreover, Kumlin (Reference Kumlin2004) has shown that a specific welfare design can also create feedback effects on citizens’ level of political trust, so these effects can further stabilize themselves.

These findings imply a ‘Catch-22 situation’, as countries can resemble one of two scenarios: On the one hand, we find a group with low trust and satisfaction levels, therefore also low-reform potential, but large unmet popular demands, as social investments remain underdeveloped and therefore new social risks uncovered. On the other hand, we observe a high-trust, high-reform potential, high-social investment cluster. Our survey experiments provide micro-level causal evidence for this interpretation and show that in today's trade-off ridden politics, there is a tight connection between political trust, public opinion and welfare state reform.

An important and interesting avenue for future research is thus: How is it possible to create and maintain political trust and government satisfaction to be able to conduct successful reforms? Oftentimes, a lack of fiscal resources is portrayed as the biggest obstacle to reforming welfare states – but our results show that political trust and government satisfaction might be another crucial scarce resource. While political trust and government satisfaction may be able to increase public support for welfare state reforms, it is important to keep in mind that we found average support for reforms involving trade-offs to be low, in particular when expansive social investment reforms would come at the expense of existing compensatory spending. As political trust also hinges on citizens´ evaluations of whether the compensatory functions of the welfare state are able to protect them from economic hardship (Kumlin & Haugsgjerd, Reference Kumlin, Haugsgjerd, Zmerli and van der Meer2017), governments thinking about reshuffling welfare state benefits between different constituency groups should be wary not to undermine the political capital needed for welfare state reform.

Acknowledgments

We presented previous versions of this paper at several conferences (APSA, CES, EPSA, ESPAnet, ECPR Joint Sessions, SVPW) and at workshops in Berlin, Boston, Florence, Frankfurt, Göteborg, Köln, Konstanz, Mannheim and Zurich. We thank the discussants and participants at these occasions for many helpful suggestions. In particular, we wish to thank Björn Bremer, Reto Bürgisser, Leslie McCall, Marc Hetherington, Thomas Kurer, Nathalie Giger, Olivier Jacques, Staffan Kumlin, Yoshi Kobayashi, Hanna Schwander, Marco Steenbergen and Eva-Maria Trüdinger. We also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for constructive feedback. Research for this paper was supported with a Starting Grant from the European Research Council, Grant No. 311769.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1: Number of interviews, and response rates by country

Table A.2: Comparison of our dataset (INVEDUC) to the European Social Survey (ESS)

Table A.3: Balance test for the split-sample questions, checking the randomization

Table A.4: List of question wording and descriptive statistics for all variables for Study 1

Table A.5: Regression table – effect of government satisfaction on 10 reform scenarios (Study 1)

Table A.6: Regression table – all trade-off questions pooled (Study 1)

Table A.7: Regression table – robustness test: including vote intention for the incumbent government (and its interaction with government satisfaction) (Study 1)

Table A.8: Regressions by country (Study 1), pooled policy trade-offs

Table A.9: List of question wording and descriptive statistics for all variables for Study 2 (ESS)

Table A.10: Regression table – effect of different measures of government satisfaction and political trust on reform scenarios (Study 2)

Table A.11: Regression table – robustness test: including country fixed effects (Study 1)

Table A.12: Regression table – robustness test: including country fixed effects (Study 2)

Table A.13: Regression table – robustness test: testing for the influence of missing values (Study 1)

Table A.14: Regression table – all fiscal trade-off questions pooled (Study 1)

Table A.15: Regression table - robustness test: test for nonlinear interaction effects (Study 1)

Figure A.1: Predicted probabilities - robustness test: test for nonlinear interaction effects (Study 1)

Table A.16: Regression table - robustness test: including attitudinal control variables (Study 1)

Figure A.2: Predicted probabilities – robustness test: policy trade-offs, including attitudinal control variables (Study 1)

Table A.17: Regression table - robustness test: including attitudinal control variables (Study 2)

Table A.18: Regression table – tax and debt trade-off questions (Study 1)

Figure A.3: Predicted probabilities - robustness test: support for reform under tax and debt trade-off conditions (Study 1)

Table A.19: Regression table – interaction effects for ideological costs (Study 2)

Table A.20: Marginal effects of political trust and government satisfaction for ideological loser groups (Study 2)

Table A.21: Correlations between government satisfaction and political trust by country (Study 2)

Table A.22: Regression table – Consistency check for the two education vs. pensions trade-offs (Study 1)