Social media summary: Early adversity and related adult lifestyle factors increase susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder among US soldiers.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the USA. Over 8 million Americans suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); 6.8% of the population will develop PTSD at some time in their lives (Dückers et al., Reference Dückers, Alisic and Brewin2016). PTSD can be understood as a disorder of evolved defensive reactions following exposure to trauma (Cantor, Reference Cantor2009). Indeed, consistent with the condition's being rooted in species-typical psychology, despite some variation, it occurs across widely divergent sociocultural and ecological contexts (Zefferman & Mathew, Reference Zefferman and Mathew2021).

While trauma exposure is definitional to PTSD, there is nevertheless substantial inter-individual variation in the extent to which such experiences result in the condition. According to the DSM-5, pre-trauma risk factors include prior mental disorders, lower socioeconomic status, childhood adversity, minority racial status and reduced social support (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Risk is higher among females and younger adults. These individual factors predisposing PTSD risk support the deficit model of PTSD wherein one's ability to emotionally process a traumatic experience is debilitated by early adversity, resulting in dysregulated, overactive coping mechanisms persisting beyond their usefulness and long after the initial experience. This construal of adversity as cumulatively damaging or hindering an individual's cognitive and emotional capacity for coping with potentially traumatic experiences is a component of all major existing theories and perspectives on PTSD etiology.

Viewed from an evolutionary perspective, the deficit model can be understood in one of two ways. First, the extent of developmental canalisation may have been inherently constrained. All else being equal, a developmental process robust to perturbation would seem optimal. However, all else is not equal, as such robusticity may be prohibitively expensive (coming, for example, at the expense of the pace of development, total number of offspring, etc.). If the average payoff across individuals of robust development exceeds the cost, canalisation will be incomplete – in essence, selection will favour a degree of developmental fragility as a price worth paying, the consequence being that adverse early experiences may set the stage for multiple adult pathologies. Alternately, selection may favour developmental plasticity rather than canalisation. Insults during development may constitute cues regarding the expected payoffs of enduring investments in maintenance.

Life history theory seeks to understand key aspects of the adult phenotype in terms of inherent tradeoffs between growth, reproduction and longevity. Of direct relevance here, various versions of life history theory hold that adverse early experiences can indicate that, given corresponding expected high adult mortality, on average fitness will be optimised by devoting resources to rapid maturation and reproduction at the expense of longevity (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Bianchi, Griskevicius and Frankenhuis2017; Figueredo et al., Reference Figueredo, Vásquez, Brumbach, Schneider, Sefcek, Tal and Jacobs2006; Hill & Kaplan, Reference Hill and Kaplan1999; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Griskevicius, Kuo, Sung and Collins2012; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Guo, Gao and Kou2020). Considerable debate surrounds various applications of life history frameworks to individual variation among contemporary humans (see Frankenhuis & Nettle, Reference Frankenhuis and Nettle2020; Stearns & Rodrigues, Reference Stearns and Rodrigues2020; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Guo, Gao and Kou2020). Furthermore, observers (see Frankenhuis & Nettle, Reference Frankenhuis and Nettle2020; Sear, Reference Sear2020) have distinguished between the use of the life history framework in the measurement of features directly associated with the key tradeoffs (such as morphological and physiological attributes; the timing of sexual maturation and reproduction; total fertility, etc.) and the use of this framework in the measurement of psychosocial features that, conceptualised as part of overall strategies, are more distally related to these tradeoffs (such as personality, sociosexual orientation, future discounting, cooperativeness, etc.). Critics (ibid.) argue that, unlike the former corpus, the latter body of work is too far removed from the tradeoffs central to life history theory to be informed by such considerations – and at least one study has found that, when psychometric measures are directly pitted against biodemographic indices more closely linked to the key tradeoffs, the former fail to predict the latter (Međedović, Reference Međedović2020).

While acknowledging the limitations of some translations of life history frameworks to the psychological domain, in an attempt to better illuminate the relationship between early experience and PTSD, here we suggest two applications of the life history approach which apply the construct of a life history strategy while conceptually centring the key principle of tradeoffs between growth, reproduction and longevity. Deferring for the moment the details of how we operationalise life history strategy, below we outline these two theoretical applications.

First, if a harsh early environment is treated by evolved calibration mechanisms as predictive of high extrinsic mortality in adulthood, investments in rapid maturation and reproduction may be privileged over investments in long-term maintenance and repair, leading to a less resilient adult phenotype. This provides an ultimate explanation for the patterns posited by the conventional deficit model of PTSD etiology. Individuals who experienced adverse early environments will be more vulnerable to a variety of insults to fitness not because building resilience was inherently precluded by deprivation, but rather because the resources necessary for such resilience were instead committed to rapid growth and reproduction. If any potential gains from greater durability would probably be precluded by fatal challenges against which no degree of resilience would suffice, then building resilience yields lower expected payoffs than accelerating reproduction.

The deficit model of PTSD is both intuitive and supported by a considerable corpus of epidemiological findings. For example, for US disaster workers who responded in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the PTSD incidence was higher among those whose lifestyle characteristics were associated with greater early adversity (Giosan & Wyka, Reference Giosan and Wyka2009). However, not all available evidence supports this model. Despite the description present in the DSM-5, meta-analyses have shown that racial minority status – which, reflecting the consequences of discrimination, is frequently associated with adverse early experiences – is a weak or absent predictor (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli and Vlahov2007; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau and Koenen2011). Moreover, research into psychological resilience has demonstrated that, under certain circumstances, adversity is critical to developing resilience (Luthar, Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). Within the US military, reserve forces – who, being more educated and enjoying higher socioeconomic status, can be presumed to have suffered fewer adverse early experiences – sometimes have similar or higher PTSD rates compared with active-duty troops (Lane et al., Reference Lane, Hourani, Bray and Williams2012; Milliken et al., Reference Milliken, Auchterlonie and Hoge2007). Lastly, a recent study of PTSD in 24 nations found that measures of adversity such as malnutrition, income inequality and access to sanitation were negatively, not positively, associated with rates of PTSD, even controlling for exposure to traumatic experiences (Dückers et al., Reference Dückers, Alisic and Brewin2016). Such observations suggest that alternative accounts may be required.

Life history theory can again be a fertile source of possibilities. Emergency responses to imminent threats are costly. The value of extensive responses thus hinges in part on the expected frequency of crises, as frequent high levels of activation throughout adulthood will often not be sustainable. If early experiences provide cues of the expectable adult environment, then, in the service of sustainability, adverse early experiences may tamp down adult emergency reactivity. Such a pattern is particularly adaptive if many of the most significant sources of adult mortality are truly extrinsic, such that marshalling resources to address a source of danger will do little to buffer the individual against the threat. Rather than being wasted in the fruitless pursuit of longevity, such resources are instead better spent in enhancing reproduction. If PTSD constitutes a pathological chronic hyper-activation of emergency responses, then, being less reactive to crises, individuals with a history of adverse early experiences could actually be at lower risk of PTSD – the opposite prediction to that of the deficit model. In this application of life history theory, individuals who experience propitious early environments will deploy extensive resources in the face of fitness insults in order to pursue longevity; ironically, however, this very reactivity will make them vulnerable to pathologically excessive defensive responses that endure long after a momentous threat has passed.

Epidemiological data support the association of early adversity with such physiological and behavioural characteristics as faster development, more offspring, decreased self-investment, higher preference for risk-taking, more selfish and less pro-social attitudes, steeper future discounting and present-orientation, and a preference for shorter-term sexual relationships (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Ruttle, Boyce, Armstrong and Essex2015; Brumbach et al., Reference Brumbach, Figueredo and Ellis2009; Carver et al., Reference Carver, Johnson, McCullough, Forster and Joormann2014; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Lester, DeGarmo, LaGasse, Lin, Shankaran and Higgins2011; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Hilton, Park, Tooley, Boroshok, Mupparapu and Mackey2021). In short, existing evidence suggests that there is indeed adaptive calibration of life history trajectory early in life. However, it remains an open question whether such traits reflect a phenotype in which the individual is more vulnerable to, or, conversely, better prepared for, potentially traumatic experiences.

To explore the competing possibilities described above, using a large military sample, we examined the extent to which early life adversity influences lifestyle and personality characteristics in adulthood that, in turn, may correlate with PTSD risk. A military sample affords relatively high rates of both exposure to traumatic events and PTSD, increasing statistical power for detecting correlated traits. For much of the past two decades, the US has been actively involved in armed conflict. Throughout this period, the US military has screened service members for PTSD following deployment. Relative to the general population, US military personnel thus constitute a community both at greater risk of developing PTSD and more likely to have been evaluated for PTSD. The Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) dataset includes detailed records on exposure to potentially traumatic experiences, as well as personal, health and lifestyle data, allowing for a multiplex assessment of life history orientation and its relationship with PTSD.

Sample

Our data derive from the United States Army STARRS Consolidated All Army Survey (AAS), an epidemiological study that combined data across three surveys:

(1) the core AAS, a survey administered from 2011 to 2012 in a probability sample of 17,462 active Regular Army, National Guard, and Army Reserve units worldwide, excluding soldiers deployed or in basic training;

(2) a 2012–2013 AAS expansion that surveyed 3987 deployed soldiers stationed in Afghanistan while in Kuwait awaiting transit to or from mid-deployment leave; and

(3) the baseline STARRS Pre-Post Deployment Survey, which surveyed 8558 soldiers in three Brigade Combat Teams shortly before deploying to Afghanistan in 2012.

The recruitment, informed consent and data collection procedures, described in more detail elsewhere (Kessler, Colpe, et al., Reference Kessler, Colpe, Fullerton, Gebler, Naifeh, Nock and Heeringa2013), were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, MD, USA) for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (the primary grantee), the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA, the organisation collecting the data), Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA, USA), and the University of California, San Diego (La Jolla, CA, USA). All study participants gave written informed consent.

Information on handling bias, including sample weighting, response rate and sample exclusions, is reported elsewhere (Kessler, Heeringa, et al., Reference Kessler, Heeringa, Colpe, Fullerton, Gebler, Hwang and Ursano2013). We focus on the 21,449 respondents who completed a survey. We excluded respondents who did not consent to link their administrative records to their survey for analyses that include service component as a covariate. In total, 17,462 soldiers who completed the survey consented to administrative data linkage. One-hundred and eighty respondents were omitted because the survey data did not include PTSD symptom and/or age data; 1443 were excluded owing to their reporting subadult-onset PTSD. A further 3,730 respondents’ data did not include one or more set of survey items on which we conducted our life history orientation principal components analysis. This left a sample of n = 16,096; see Supplemental Table S1 for sample characteristics.

Methods

Variables extracted from STARRS

PTSD

A majority of participants answered nine PTSD checklist (PCL)-based survey questions about PTSD symptoms (Bliese et al., Reference Bliese, Wright, Adler, Cabrera, Castro and Hoge2008). Some 4,102 of those did not record age of onset, so a second survey item and its associated age of onset was used where present (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Wickramaratne, Adams, Wolk, Verdeli and Olfson2000).

Exposure level

Participants responded to 14 questions about potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs) during deployment (e.g. combat patrol duty, assault, firing rounds at the enemy or taking fire, being wounded in combat). Each question asked about the number of times each PTE occurred during any previous deployment.

Early adversity measures

Parent's education: maximum education level of either parent was used as a proxy for childhood socioeconomic status (SES). The dataset values ranged from 1 (no education) to 8 (post-graduate; see Supplemental Table S1).

Early head injuries: childhood head injury sufficient to cause loss of consciousness, eardrum perforation, memory loss or dazing comprised the second measure of early adversity. These four possible head injury conditions suffered in childhood were added together to form a composite with a range of 0–4. The multiple durations of ‘loss of consciousness’ were collapsed into a binary value for the loss of consciousness injury condition prior to compositing with the other early age head injury conditions.

Life history construct

From the wide array of survey items employed in the STARRS, we identified those relevant to psychological traits hypothesised to be associated with differing life history orientations, including self-investment, relationship quality, prosociality and reproduction (Brumbach et al., Reference Brumbach, Figueredo and Ellis2009; Figueredo et al., Reference Figueredo, Vásquez, Brumbach, Schneider, Sefcek, Tal and Jacobs2006). Multiple survey items were composited for each of the eight categories: relationship quality, education, health, tobacco addiction, substance use and abuse, antisocial attitudes, criminal involvement and number of children. When items within the same category used different scales, items were normalised by dividing the value by the maximum item value within each category. To facilitate interpretation of results, where necessary, scales were inverted such that a higher numerical value was consistent with the predicted trait associated with early adversity (see Supplementary Materials, life history category construction). A principal component analysis was performed on the eight category composites. The first principal component (PC1) accounted for a 23.8% plurality of the variance (see Figure 1). Every category composite loaded positively and, other than the number of children item, quite substantially on PC1, therefore PC1 was selected as the life history orientation construct for subsequent analyses.

Figure 1. Principal component analysis of the lifestyle latent variables. (a) Proportion of variance explained by each of the eight principal components. (b) Loadings of PC1 and PC2 on the eight variables. For information on how the variables were constructed from the Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) dataset, see Methods and Supplementary Materials.

Covariates

Age, race, sex, service component, location of the interview

Age was a continuous variable. Sex was a binary variable. Race was coded in three ways, white or not white, Black or not Black, or as a categorical variable with eight levels (white, Black, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, bi-racial, or other). These were exclusive categories, i.e. individuals were placed in one and only one category. Multi-racial refers to individuals who checked yes to at least two of the categories. Service component was a categorical binary of active duty or not, in which ‘not’ meant a member of the National Guard or Reserve who had been activated and deployed. Location of the interview was coded as a categorical variable with three levels: USA, overseas base and overseas theatre.

Subjective coping resources

Subjective coping resources act as buffers against stress and adversity. These can include the degree of direct and indirect social support, as well as pre-trauma well-adjustedness. For deployed soldiers, their professional setting is also their de facto community and base of social support for months or longer. Therefore, their view of the degree of acceptance, respect, support, competence, fairness and professionalism should be an important factor aiding them in coping with PTEs. The 14 items chosen for this composite included the participant's rated morale, whether they feel discriminated against, the degree to which they can rely on peers and superiors for help, how well leaders treat soldiers, and whether they respect the unit leadership (for a complete list, see Supplemental Table 2). Coding of eight of the variables was inverted so that higher values consistently indicated greater subjective coping resources across all items. The items were normalised and averaged together to produce the coping resources composite variable.

Resilience to stress

Participants responded to five items by indicating their ability to keep calm in a crisis, manage stress, try new approaches when old ways do not work, get along with people when ‘you have to’ and keep a sense of humor in tense situations. The encoding was inverted so that higher values indicated increased self-reported resilience. They were summed to produce the resilience composite variable.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using RStudio version 1.4.1106. Principal component analysis was used to extract the main axis of variation (PC1) from the eight compiled measures of life history orientation described above. The probability of PTSD diagnosis was analysed as a linear function of multiple continuous and categorical predictor variables using logistic regression implemented using the ‘glm’ function and entering family as ‘binomial’. Fisher's exact test was used for pair-wise comparisons of the probability of PTSD diagnosis between two groups without correcting for any covariates (e.g. two sexes, two races). Mediation analysis was conducted using the mediation library in R. Two separate mediation analyses were conducted for each of the early adversity measures: number of head injuries and parent's education level. Specifically, the extent to which each of the early adversity measures influenced PTSD probability via its influence on the life history construct (PC1 from the principal component analysis; see above) was evaluated. Correlations between two continuous variables were evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results

Early adversity increases PTSD risk

Analysis of PTSD risk as a function of early head injuries showed a positive correlation by logistic regression (no covariates, slope = 0.3; p < 0.0001). Parent's education was significantly negatively correlated with PTSD risk (no covariates, slope = −0.035, p = 0.01). The two measures of early adversity were weakly positively correlated with each other (Pearson's r = 0.073; p < 0.0001).

Life history metric

The first principal component (PC1) extracted from 44 variables (see Supplemental Table S2) explained 23.8% of the variation in the data (Figure 1a). Each of the variables was positively loaded on PC1, indicating that all the variables contributed to PC1 in the expected direction, with the weights shown in Figure 1.

Life history strongly predicts PTSD risk

In a logistic regression analysis predicting PTSD risk as a function of exposure, number of head injuries in childhood, parent's education, survey location, service component (active duty vs. guard/reserve), sex, coping, resilience, age, race and PC1, all of the variables were significant (Figure 2)(type III sums of squares) except parent's education (Table 1). Race was marginally insignificant (p = 0.057). We analysed race both as a categorical variable with eight levels (see above) and on the presumption that, although many people of colour suffer discrimination in the US, on average, Black individuals plausibly suffer the greatest disadvantage, as a binary variable (entered as Black or not Black). In all cases, race remained not significant (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2. Estimated probability of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; ± SE) shown for three levels of exposure to potentially traumatic experiences during deployment for representative low vs. high score for the lifestyle factor (PC1). PTSD risk increases with the lifestyle latent variable independent of degree of exposure to potentially traumatic experiences during deployment. Estimates were from a linear model that included all the covariates entered as average values from the sample, and in cases where the variables are categorical, we entered the first level as coded, which ended up being male, white, active duty, base location. Exposure levels were the first, second and third quartiles in the sample (Exp = 0.0, 19.3, 33.3). First and third quartiles were used for low and high values for the lifestyle construct (PC1 = −0.885, 0.751).

Table 1. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) risk logistic regression model

PTE, Potentially traumatic experience; PC, principal component.

Race is not a significant predictor of PTSD risk even without correcting for covariates

We also analysed PTSD risk as a function of only race (Black or not Black) absent other factors. The result was marginally not significant with a trend towards reduced PTSD risk for Black soldiers (p = 0.09381). When all races were entered as a categorical variable (1–8), race was also marginally not significant (p = 0.05).

Sex is a highly significant predictor of PTSD risk

Without correcting for any covariates, women displayed a 1.27-fold increased risk compared with men. This difference was larger (1.71-fold) after correcting for all covariates (Supplemental Figure S1b).

Number of traumatic experiences is also a strong predictor of PTSD risk

Figure 3 shows the probability of suffering PTSD as a function of the number of traumatic experiences (first quartile, mean, third quartile), separately for individuals with a low vs. high score for PC1 (first and third quartiles for PC1), illustrating the large effect that life history orientation has on risk independent of the number of traumas experienced.

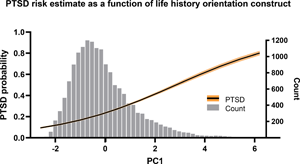

Figure 3. Estimated probability of PTSD (± SE) as a function of lifestyle orientation (PC1) and PC1 frequency histogram. PTSD probability is estimated from the linear model shown in Table 1, with all the covariates entered as average values from the sample, and in cases where the variables are categorical, we entered the first level as coded which ended up being male, white, active duty, base location. Lifestyle orientation as measured by PC1 is significantly positively associated with PTSD risk after controlling for all covariates in the full model.

Guard and reserve soldiers had a marginally lower value for life history orientation, and lower PTSD risk

Active duty status was associated with increased PTSD risk after controlling for all covariates (s = 0.1852, p < 0.001, n = 1).

Mediation analysis

The results reveal that both early adversity measures affected PTSD risk via life history characteristics. The number of early head injuries had a significant direct effect and a significant mediation effect (Table 2). Approximately 25% of the total effect was mediated via life history factors. Parent's education did not have a significant direct effect, but there was a significant mediation effect (Table 2). Approximately 84% of the total effect was mediated by life history factors.

Table 2. Mediation analysis

Discussion

The hypothesis that a life history orientation associated with early adversity could buffer against PTSD risk was not supported in our results. On the contrary, a life history orientation characterised by greater risk-taking and anti-social behaviour, and fewer long-term investments was a potent positive predictor of PTSD risk. At the lower end of the life history orientation distribution (associated with a nurturing early environment), PTSD risk was about 15%; at the higher end (associated with a harsh early environment), this risk was over 50% (Figure 2). This relationship held even controlling for exposure, early adversity, sex, age, race, resilience and subjective coping resources. In our analytical model, a soldier at the low end of the life history construct (PC1 first quartile) would require more than double the number of exposures to potentially traumatic events to equal the PTSD risk for the high end (PC1 third quartile) given mean exposure. Few epidemiological PTSD studies have controlled for both the frequency and degree of exposure to potentially traumatic experiences and pre-existing childhood trauma.

Evolutionary perspectives on PTSD

To our knowledge, we are the first to hypothesise that a fast life history orientation might buffer PTSD risk. Our analysis does not support this hypothesis. Instead, it supports the prevailing deficit model, an account congruent with either constrained developmental canalisation or the dominant view among psychological life history theorists, namely that health, including mental health, is traded off against other demands among ‘faster’ individuals (Del Giudice, Reference Del Giudice2014; Giosan & Wyka, Reference Giosan and Wyka2009): the fast life history developmental syndrome sacrifices elements of phenotypic robustness in order to prioritise faster development and earlier reproduction, similar to the way that immune system competence and somatic maintenance are diminished. This appears to extend to the mind as well, with fewer resources dedicated to managing substantial adversity because superlative (vs. adequate) coping with such adversity may principally benefit only those phenotypes betting on a longer life.

We acknowledge that it is difficult to fully adjudicate among the possible explanations described above. While this application of life history theory can be seen as complementing the standard deficit model, providing an account of ultimate causation that interdigitates with the latter's proximate explanation, by virtue of their complementarity, it is difficult to determine whether one, the other or a combination of these accounts is correct. Nevertheless, some evidentiary space may exist between the stand-alone conventional deficit model and a version thereof that is informed by life history theory. Specifically, in addition to making sensical the relationships between early experience, adult lifestyle factors and PTSD risk, it is possible that the addition of life history highlights some aspects of developmental experience that underspecified notions of ‘abuse and neglect’ might otherwise overlook. For example, investigators have only recently begun exploring the covariation between (conventionally defined) adverse childhood experiences and childhood food insecurity (e.g. Baiden et al., Reference Baiden, Labrenz, Thrasher, Asiedua-Baiden and Harerimana2021). However, whereas a deficit approach explains the detrimental developmental effects of the latter in terms of nutritional inadequacy, a life history perspective dictates that, even if nutritional needs are met, the experience of food insecurity may constitute a developmental cue that, being predictive of an adverse adult environment, results in a faster life history strategy (Nettle, Reference Nettle2017), including both associated lifestyle factors and reduced investment in maintenance, with corresponding increased vulnerability to disorders such as PTSD.

Lastly, adjudicating among the potential explanations for results such as ours is further complexified by the possibility that patterns evident among contemporary soldiers in a highly developed nation may reflect evolutionary disequilibrium. The virtues associated with a nurturing environment, e.g. prosociality, conscientiousness and self-investment in education and skill, are all highly rewarded in the US. Conversely, potential virtues theorised to result from a harsher environment, e.g. aggression, risk-taking and short-term mating preferences, are today punished by law or social censure. In addition, early adversity increases the risk of poverty (Frederick & Goddard, Reference Frederick and Goddard2007), and in the US, poverty exacerbates and magnifies many hindrances to flourishing that compromise coping resources, such as a lack of access to healthcare, the inability to legally defend oneself from undue insults of the state, poor access to quality education, poorer nutrition and food insecurity.

Early adversity

Working within the constraints of the STARRS dataset, our lack of rich data on early adversity is a significant limitation of the current study. The direct association between head injuries during childhood and PTSD risk could be mediated by traumatic brain injuries, as such injuries have been associated with PTSD risk in previous studies (Hoge et al., Reference Hoge, McGurk, Thomas, Cox, Engel and Castro2008; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Whitehead, Otte, Wells, Webb, Gore and Maynard2015; Schneiderman et al., Reference Schneiderman, Braver and Kang2008; Yurgil et al., Reference Yurgil, Barkauskas, Vasterling, Nievergelt, Larson, Schork and Baker2014). The mediated effect suggests that physical damage to the brain also interacts with resulting life history orientation that, in turn, increases PTSD risk. The SES proxy of parent's education was a weak but significant positive predictor of the life history orientation composite variable (without covariates) and PTSD (without covariates, see Figure S1 C), consonant with predictions and previous studies (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli and Vlahov2007; Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz, Davis and Andreski1998; Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews, Valentine and Holloway2000; Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Poulton, Martin and Caspi2007). The mediation analysis suggests that the influence of parent's education on PTSD risk was nearly entirely indirect, through its influence on the life history latent variable. More early adversity measures that do not involve head trauma, such as other SES measures, witnessing violence, losing family members, food insecurity and harsh and inconsistent parenting, are needed to strengthen the evidence for a positive association between early adversity and the life history construct.

Race

We found a small, marginally non-significant effect of race, such that being Black, arguably the most disadvantaged racial identity in the US, trended towards offering protection from PTSD. The deleterious effects of discrimination and racism on mental health have long been a focus in psychopathology research, particularly for Black and Latinx individuals in the US. These effects are implicated in elevated rates or severity of depression, anxiety and substance use disorders among some racial minorities. The deficit model predicts substantially increased PTSD rates for persecuted minority groups, particularly when exposure to potentially traumatic experiences is higher. Although elevated risk for PTSD among minorities has been reported (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz, Davis and Andreski1998), controlling for appropriate factors such as SES, life stress and degree of exposure tends to eliminate effects of race (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews, Valentine and Holloway2000; Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli and Vlahov2007; but contra Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau and Koenen2011). Accordingly, we conclude that direct measures of adversity and lifestyle are likely to be more informative than race as regards PTSD risk.

Age

Previous studies generally find PTSD risk to be somewhat higher among younger adults (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli and Vlahov2007; Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews, Valentine and Holloway2000). However, results from military samples have been mixed in this regard (Xue et al., Reference Xue, Ge, Tang, Liu, Kang, Wang and Zhang2015). We found a small (slope = 0.035, p < 0.0001) positive association between age (older) and PTSD risk when controlling for covariates. Holding aside geopolitical vagaries that increase or decrease US military engagement, among career soldiers, age can be expected to correspond to total exposure to PTEs, hence a positive correlation with PTSD is in keeping with the impaired-resilience account.

Sex

Consonant with numerous other studies, women exhibited higher risk of PTSD (Supplemental Figure S2g). The disparity increased when covariates were controlled for, increasing from 1.27 times to 1.71 times the risk for PTSD among men. Consonant with the notion that, in an effectively polygynous species such as ours, females are characterised by a slower life history orientation than males (Kruger & Nesse, Reference Kruger and Nesse2006; Tarka et al., Reference Tarka, Guenther, Niemelä, Nakagawa and Noble2018), the mean PC1 value was lower among women (−0.1274) than among men (0.1234). Nevertheless, the benefits of lower values on our life history orientation factor were not enough to offset other factors that magnify PTSD risk among women. In non-military samples, across cultures, women evince greater anxiety, neuroticism and pain sensitivity than men, and lower sensation seeking, attributes which are consistent with a more cautious, harm-avoidant strategy consonant with lower sex-specific variance in fitness (Benenson et al., Reference Benenson, Webb and Wrangham2021; Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Fessler, Chan, Ashokkumar and Holbrook2018). These personality correlates themselves constitute risk factors for PTSD (Calegaro et al., Reference Calegaro, Mosele, Negretto, Zatti, Da Cunha and Freitas2019; Jakšić et al., Reference Jakšić, Brajković, Ivezić, Topić and Jakovljević2012). Hence, although a slower life history orientation appears to generally buffer against PTSD, the sex difference in PTSD risk may ironically be due to ‘slow’ personality features which are more common among women. We acknowledge, however, that it is an open question whether results such as ours are explicable in this manner, as highly anxious, harm-avoidant individuals are unlikely to volunteer for military service, and unlikely to be accepted or retained if they do. Lastly, women suffer sexual assault in the military at far higher rates than men, and this crime is probably significantly underreported (Wilson, Reference Wilson2018), hence the sex difference in PTSD risk may partially reflect patterned differences in exposure to unreported potentially traumatic experiences.

Limitations

As some of the above points suggest, a military sample is not representative of the US civilian population. It is demographically distinct, being mostly male and having many more younger vs. older adults, with service being restricted to those who meet many qualifications of health and legal good-standing. Likewise, viewed cross-culturally, both the norms within the US military and the beliefs of the larger US society are not representative of the diverse meaning systems within which individuals may situate traumatic experiences, with corresponding implications for some facets of PTSD (Zefferman & Mathew, Reference Zefferman and Mathew2021).

Importantly, as noted above, our measures of early adversity are quite limited, with only a proxy for SES (parent's education) and a few items comprising the head injury measure. Consonant with the logic of the deficit model, head injury is associated with PTSD independent of other factors, potentially confounding our use of this variable. For these reasons, the connection we draw between early adversity measures and the life history orientation latent construct is tenuous, although other studies have provided evidence of such a link (Brumbach et al., Reference Brumbach, Figueredo and Ellis2009).

Conclusion

Millions of Americans suffer debilitating effects of PTSD, some for many years. Effective pharmaceutical and therapeutic solutions have remained elusive. Prevention is therefore all the more important. In turn, efforts to prevent PTSD hinge on understanding underlying risk factors. Early life adversity as a predisposing risk factor is both intuitive and empirically supported, and appears to act in part through features of adult lifestyle characteristic of a fast life history trajectory. With the caveat that our measures are subject to substantial limitations, our findings bolster the prevailing view of developmental adversity as erosive to psychological capacities to cope with trauma. Institutions, such as modern armed forces, in which exposure to potentially traumatic events is likely to occur, may therefore better serve both their members and society at large by assessing such risk factors during selection and training, and directing enhanced resources to members at greater risk.

Acknowledgements

This publication is based on public use data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Service members (Army STARRS). The data are available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan (http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR35197.v2). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Army STARRS investigators, funders, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense. We thank Justin Rhodes (the loyal opposition), Andrew Shaner and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful input.

Author contributions

Daniel Fessler and Edward Clint conceived and designed the study and wrote the article. Edward Clint performed the statistical analyses and produced the tables and graphs.

Financial support

Daniel Fessler benefited from the support of the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Award FA9550-15-1-0137.

Conflicts of interest

Edward Clint and Daniel Fessler declare none.

Data availability

The data are available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan (http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR35197.v2).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2022.19