Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) and psychotic disorders constitute two of the most serious psychiatric disorders in terms of their impact on social functioning, comorbidity with physical and mental health conditions, and raised mortality rates (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, & Nielsen, Reference Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales and Nielsen2011; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014, 2017; Walker, McGee, & Druss, Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015). Both typically emerge between adolescence and emerging adulthood (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2022) and can be conceptualised as umbrella terms that include a range of diagnoses. Psychotic disorders include but are not limited to schizophrenia, delusional disorder and schizoaffective disorder, whilst EDs include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (World Health Organisation, 2019). In addition, both EDs and psychotic disorders can each be conceptualised as a continuum ranging from subclinical symptoms that are relatively common in the general population (e.g., dieting within certain ranges, hearing voices or seeing visions others do not), to more severe presentations meeting thresholds for diagnostic criteria. Accordingly, incidence and prevalence estimates vary depending on the stringency of criteria. The estimated global incidence of all psychotic disorders is 26·6 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 22·0–31·7) (Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride, & Jones, Reference Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride and Jones2019), whilst the estimated lifetime mean prevalence of EDs is 8.4% (Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert, & Tavolacci, Reference Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert and Tavolacci2019).

EDs and psychosis have tended to be treated as separate domains in both research and clinical settings. However, several converging lines of evidence suggest that psychosis and EDs are associated in ways that hold promise for future research and treatment. Firstly, emerging evidence from genetic studies suggest a strong genetic association between eating disorders and schizophrenia. Two genome-wide association studies have reported genetic correlations between AN and schizophrenia (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Yilmaz, Gaspar, Walters, Goldstein, Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Ripke, Thornton, Hinney, Daly, Sullivan, Zeggini, Breen, Bulik, Duncan, Yilmaz, Gaspar, Walters and Bulik2017; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Yilmaz, Thornton, Hübel, Coleman, Gaspar, Bryois, Hinney, Leppä, Mattheisen, Medland, Ripke, Yao, Giusti-Rodríguez, Hanscombe, Purves, Adan, Alfredsson, Ando and Bulik2019), meaning that there are genetic variations associated with both disorders. In the study by Watson et al. (Reference Watson, Yilmaz, Thornton, Hübel, Coleman, Gaspar, Bryois, Hinney, Leppä, Mattheisen, Medland, Ripke, Yao, Giusti-Rodríguez, Hanscombe, Purves, Adan, Alfredsson, Ando and Bulik2019), genetic correlations were also found between AN, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and bipolar disorder. Meanwhile, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Larsen, Kuja-Halkola, Thornton, Yao, Larsson and Bergen2021) investigated the familial co-aggregation of EDs and schizophrenia using data from the entire Swedish and Danish population. Individuals with EDs or AN were around 5–6 times more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia compared to individuals without AN, with the odds increasing to 10–13 times more likely in men from the Swedish sample. Relatives of individuals with EDs had increased odds of a schizophrenia diagnosis, with higher odds for relatives with increased genetic relatedness such as siblings and parents.

Recent years have seen increased interest in the notion of a single dimension of psychopathology, or p factor, representing a general propensity to developing mental disorders (Caspi, Houts, Fisher, Danese, & Moffitt, Reference Caspi, Houts, Fisher, Danese and Moffitt2024). High rates of co-morbidity between psychiatric disorders have led to the suggestion that a more parsimonious structure to psychopathology might exist (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt2018). One endeavour to investigate the structure of psychopathology is the work of the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) consortium (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Forbes, Forbush, Fried, Hallquist, Kotov, Mullins-Sweatt, Shackman, Skodol, South, Sunderland, Waszczuk, Zald, Afzali, Bornovalova, Carragher, Docherty, Jonas, Krueger and Eaton2019). In Forbes et al.’s (Reference Forbes, Sunderland, Rapee, Batterham, Calear, Carragher, Ruggero, Zimmerman, Baillie, Lynch, Mewton, Slade and Krueger2021) HiTOP study, a broad thought disorder symptom cluster included eating pathology, psychotic symptoms and OCD, suggesting that eating pathology and psychosis might be more closely associated than has been assumed to be the case. This hypothesis is supported by numerous studies of clinical populations evidencing comorbidity between psychosis and EDs. Indeed, case studies reporting co-morbid psychosis presentations in EDs have been reported for at least 40 years (e.g. Grounds, Reference Grounds1982; Sarró, Reference Sarró2009).

In summary, several converging lines of evidence suggest that the overlap between EDs and psychosis could be fertile ground for clinically relevant developments in research and practice. Genetic studies point to an association between ED and psychosis, raising the possibility of shared aetiological pathways. This could have implications for prevention and early intervention efforts for both disorders. Secondly, mechanisms for the association between ED and psychosis could include nutrition, since nutritional deficiencies are a risk factor for psychosis (Firth et al., Reference Firth, Carney, Stubbs, Teasdale, Vancampfort, Ward, Berk and Sarris2018). Thirdly, understanding co-morbidity between EDs and psychosis could lead to developments in treatment, such as interventions targeting the ED voice, which is the experience of a critical voice commenting on the hearer’s weight and food intake, instructing them not to eat and telling them that they do not deserve to eat (Dolhanty & Greenberg, Reference Dolhanty and Greenberg2009; Pugh, Reference Pugh2016). Moreover, antipsychotic medication has a long history of usage in EDs, with recent interest in the potential for olanzapine in adolescent AN (see Lewis, Bergner, Steinberg, Bentley, & Himmerich, Reference Lewis, Bergner, Steinberg, Bentley and Himmerich2024, for a review). Finally, it is possible that diagnostic overshadowing may result in under-identification of ED and psychosis within clinical populations, leading to increased complexity and patient distress.

To the best of our knowledge, only two reviews of the ED/psychosis overlap have been conducted. Sankaranarayanan et al. (Reference Sankaranarayanan, Johnson, Mammen, Wilding, Vasani, Murali, Mitchison, Castle and Hay2021) conducted a systematic review of studies of eating pathology in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, finding 31 studies. This review found elevated rates of ED pathology including disordered eating behaviour (10%–41.5% of patients), binge eating (8.9%–45%) and night eating (4%–30%), with 4.4%–16% of patients meeting criteria for binge eating disorder. More recently, Lo Buglio et al. (Reference Lo Buglio, Mirabella, Muzi, Boldrini, Cerasti, Bjornestad and Tanzilli2024) conducted a prevalence meta-analysis of eating disorders and disordered eating in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis, finding a prevalence rate of 5%. Thus far, no review has investigated the association and comorbidity of disordered eating and psychosis in the general population or in the clinical ED population, resulting in a gap in our understanding of how these symptoms co-occur across populations, and how these symptoms have been assessed in research to date.

Aim

Our aim was to systematically review the evidence for an association between ED and psychosis, across the general population and in clinical ED and psychosis populations.

Method

Our review was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021231771). We followed PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness and Moher2021) and our PRISMA checklist for the study is available in Appendix A.

Searches

Searches were conducted without date restrictions in Web of Science, PsycINFO and MEDLINE up to 26th of February 2024. The search strategy was constructed by GD and TJ and adapted for each database. Free-text and index terms were used to search for literature on eating disorders and psychosis, which were combined using Boolean operators. Search terms for each database are available in Appendix B.

Screening process

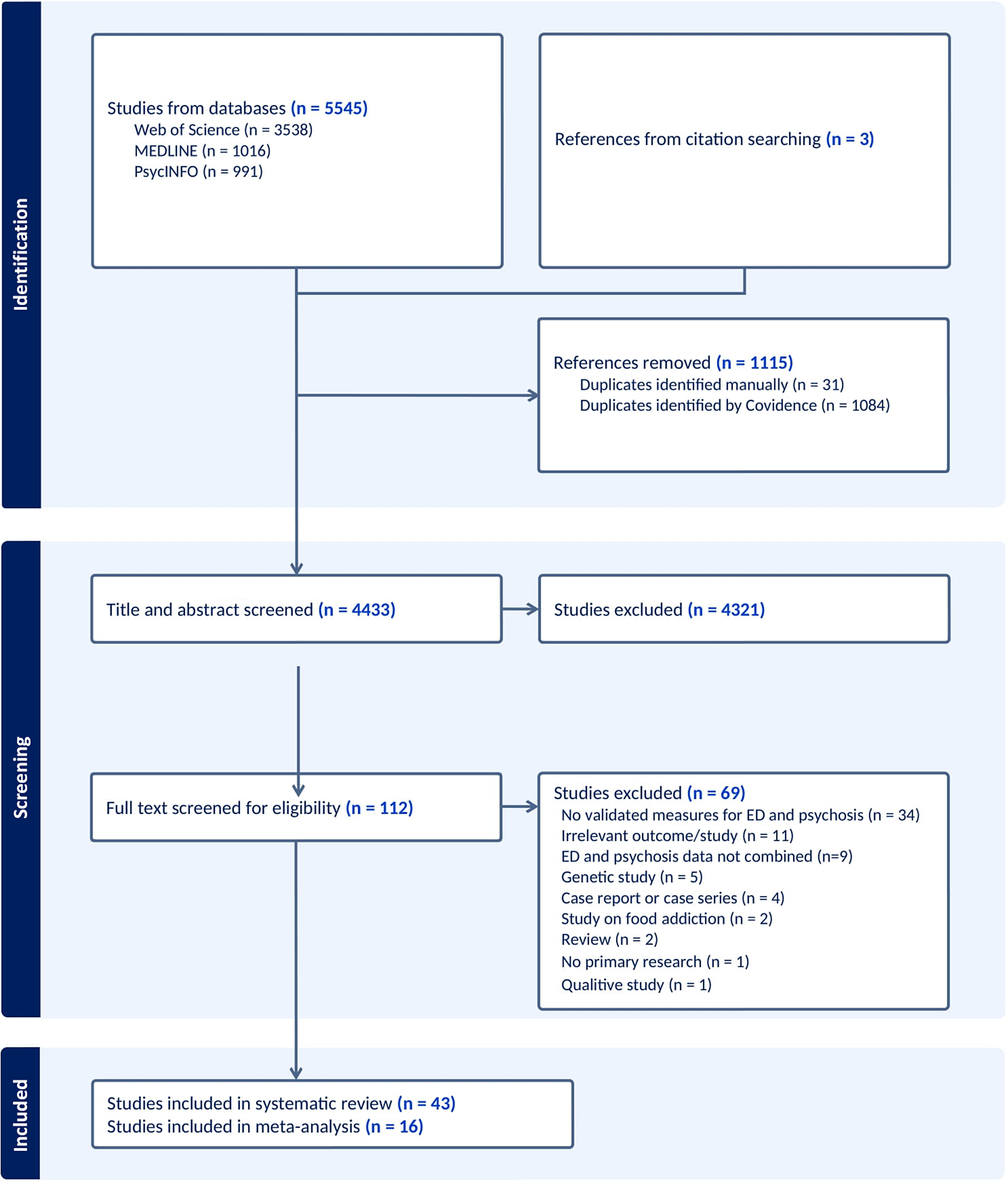

Studies were imported into Covidence for screening. RG and RMC independently screened all papers. Any disagreements were resolved by GD and TJ. Our PRISMA flowchart is presented in Figure 1. The reference lists of included studies were manually searched to identify further studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the systematic review if they were: (1) empirical studies with original data, reporting on the comorbidity of ED and psychotic disorder diagnoses, or the association between eating pathology and psychotic symptoms in clinical and non-clinical populations; (2) used validated diagnostic tools, or validated measures of eating pathology and psychotic symptoms, or diagnoses obtained from medical records made using DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria (see Appendix B for details); (3) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) in English language. Studies were excluded if they were: (1) qualitative studies; (2) case studies and case series; (3) utilized items derived from scales or interviews without validity data supporting their use; (4) studies reporting genetic correlations.

Studies were included for meta-analysis if they reported co-morbidity of EDs and psychotic disorders using ICD/DSM diagnostic criteria, based on either clinician assessment or use of a validated diagnostic interview.

Data extraction

Information presented on the methods and results section of the selected studies were extracted independently in pairs by two researchers (GD, AM, SP, MM, MJ and CN), with GD extracting data from all studies. For each study we extracted the following data, as available: the percentage of participants with co-occurring ED and psychotic disorder diagnoses; the percentage of co-occurring symptoms of disordered eating and psychotic symptoms; the association between ED and psychotic disorder symptoms, (e.g. using Pearson’s r). The following study and sample characteristics were also extracted: first author, year, country, study design, sample of participants, age, gender, ethnicity/race, socio-economic status, measure of psychosis and eating pathology and summary of main findings. For meta-analysis we extracted: (1) the number of people meeting diagnostic criteria for both EDs and psychotic disorders; (2) the total size of the sample. Where necessary, corresponding authors of eligible studies were contacted for missing data.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Scale (NOS; Wells et al., Reference Wells, Shea, O’Connell, Peterson, Welch, Losos, Tugwell, Ga, Zello and Petersen2014) for cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies. Bias was assessed independently in pairs by GD, AM, SP, MM, MJ and CN, with GD assessing all studies. The quality of the studies was assessed on three main domains: the representativeness and selection of the sample, the comparability of the groups/participants and the assessment of outcome/exposure. Studies received a maximum of eight points. Studies were defined as high methodological quality when they received a total score of 7–8 points; as moderate quality when receiving 5–6 points and poor quality when receiving 4 points or below. A modified version of NOS was created in order to assess the risk of bias of cross-sectional studies. Retrospective studies were rated as cross-sectional as their study design matched the NOS criteria for cross-sectional studies. Every study was assessed independently by each reviewer. GSP was consulted for disagreements.

Data synthesis

We planned to synthesise our findings using narrative synthesis or meta-analysis, as outlined in our preregistration (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=231771). A decision on performing a meta-analysis was made following completion of data extraction. A meta-analysis of studies reporting co-morbidity of EDs and psychotic disorders using DSM/ICD diagnostic criteria, assessed either using validated measures or by clinical assessment interviews, was possible. A meta-analysis of the correlation between psychosis and EDs was not possible due to lack of consistency in measures and statistical reporting. Therefore, a narrative synthesis was conducted for studies not meeting criteria for meta-analysis, and the findings of the studies were grouped into three categories based on sample, as follows: (1) general population; (2) clinical population with EDs; (3) clinical population with psychotic disorders.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using the proportion function within the meta suite of Stata version 18 (StataCorp, 2023) to investigate the pooled prevalence of comorbid psychotic disorders and EDs across clinical and general populations, using a random effects model. The proportion of comorbid cases (referred to as ‘Total successes’ in the forest plot) relative to the total sample (‘Total’) was calculated for each study, along with 95% confidence intervals. To explore sources of heterogeneity, meta-regressions were not indicated due to lack of studies (Deeks, Higgins, Altman, McKenzie, & Veroniki, Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, McKenzie, Veroniki, JPT, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2024), but we performed the following subgroup meta-analyses: (1) comorbidity in clinical populations with EDs; (2) comorbidity in clinical populations with psychosis. Meta-analysis of general population studies was not conducted since there were only two eligible studies with unique samples (Convertino et al., Reference Convertino and Blashill2022; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Larsen, Kuja-Halkola, Thornton, Yao, Larsson and Bergen2021), with very different methods and populations. The impact of region was explored through meta-analyses of North American and European studies. The impact of study type was explored through meta-analyses of cross-sectional and retrospective studies. No prospective studies were included in the meta-analysis. We investigated heterogeneity using I 2. Publication bias was investigated by visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test. Code and data analysis files are publicly available at https://osf.io/pgk3w/.

Results

Study selection

Our database search yielded 5545 studies, of which 1115 were duplicates and were removed. 4433 studies were screened by title and abstract. The full text was accessed for 112 studies, of which 69 were excluded, resulting in 43 studies included in the review, of which 40 studies presented unique data (see Figure 1 for details on study screening and inclusion). Three studies were identified by citation searching. Sixteen studies met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. Study and sample characteristics are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3. References of included studies, and studies excluded at full-text screening stage, are presented in Appendices C and D respectively.

Table 1. Study characteristics for general population studies

Note: AN, anorexia nervosa; BED, binge eating disorder; BMI, Body Mass Index; BN, bulimia nervosa; CAPE-42, Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences; CIDI, WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision; EAT-26, Eating Attitudes Test; ED, eating disorders; EDEQ, Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; K-SADS-PL, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version; MA, meta-analysis; MBSRQ-AS, Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales; NR, not reported; OED, other eating disorder; PDSQ, Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire; PSQ, Psychosis Screening Questionnaire; SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SZ, Schizophrenia; WERCAP, Washington Early Recognition Center Affectivity and Psychosis.

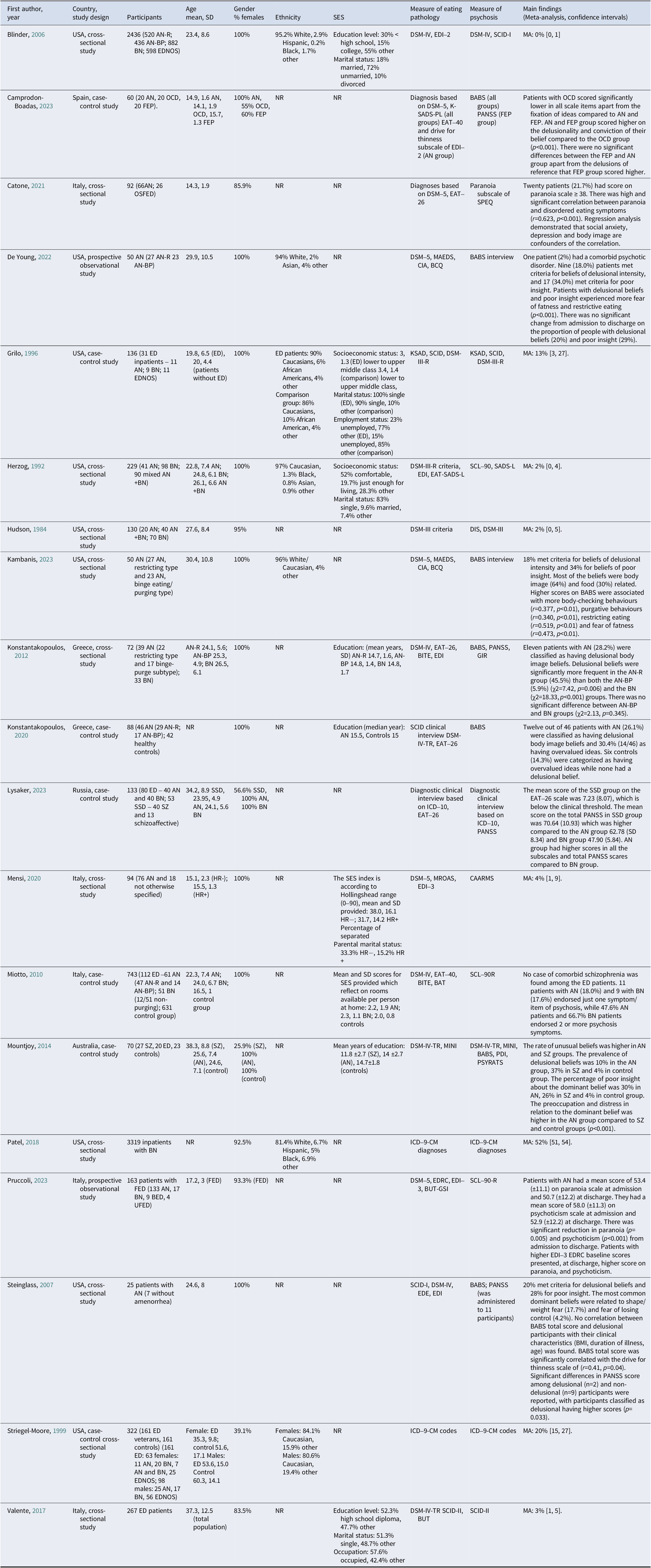

Table 2. Study characteristics for eating disorders studies

Abbreviations: BAT, Body Attitudes Test; BCQ, Body Checking Questionnaire; BITE, Bulimic Investigatory Test of Edinburgh; BUT-GSI, Body Uneasiness Test Global Severity Index; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States; CIA, Clinical Impairment Assessment, CIDI, WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview schedule; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision; EAT, Eating Attitudes Test; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination; EDI-3, Eating Disorder Inventory; EDNOS, Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified; EDRC, Eating Disorder Risk; FED, Feeding and Eating Disorders; FEP, First-Episode of Psychosis; HR−, no risk for psychosis; HR+, at high risk for psychosis/presence of subthreshold psychosis; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision Clinical Modification; KSAD, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children – Epidemiologic Version; K-SADS-PL, Children-Present and Lifetime Version; MA, meta-analysis; MAEDS, Multifactorial Assessment of Eating Disorder Symptoms; MROAS, Morgan-Russell Outcome Assessment Schedule; NR, not reported; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OSFED, other specified feeding or eating disorder; PSQ, The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire; SADS-L, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; SADS-L, modified version of Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Lifetime version to include a section for DSM-III-R eating disorders; SCAN, version 2.1, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID, Structured Interview for DSM-III-R; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Screen Patient Questionnaire-extended; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders; SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II; SCL-90-R, revised Hopkins Symptom Checklist; SCL-90-R, symptom Check List-90-R; SPEQ, Specific Psychotic Experiences Questionnaire; UFED, unspecified feeding or eating disorders.

Table 3. Study characteristics for psychotic disorders studies

Abbreviations. AMDP, Manual for the Assessment & Documentation of Psychopathology; AN, anorexia nervosa; APS, Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome; BABS, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale; BED, binge eating disorder; BMI, Body Mass Index; BN, bulimia nervosa; BSABS, Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms; DIGS, Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; EAT, Eating Attitudes Test; EAT-26, Eating Attitude Test-26; ED, eating disorders; EDNOS, eating disorders not otherwise specified; K-SADS-PL, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime vision; MA, meta-analysis; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NEQ, Night Eating Questionnaire; NES, Night Eating Syndrome; NR, not reported; PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; PDI, Peters et al. Delusions Inventory; PSYRATS, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales-Delusions; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; SCID-I/P Version 2.0, Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Edition; SCID-IV, Clinical interview using DSM-IV criteria; SD, Standard Deviation; SIPS, Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes; SOPS, Scale of Prodromal Symptoms; SSD, schizophrenia spectrum disorders; SZ, patients with schizophrenia.

The selected articles represent 40 unique studies published from 1984 to 2024. Sixteen articles contain data on clinical populations with EDs, 12 on clinical populations with psychosis, three studies compared data from clinical populations with EDs and psychotic disorders, and 12 articles utilised general population samples. The three comparative studies with data on EDs and psychosis were grouped with the ED studies. Study characteristics are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3. The risk of bias and the methodological quality of the selected studies are presented in Appendix E. All studies were of high or moderate quality.

Narrative synthesis: general population studies

In total 12 articles with community populations were included in this review, which represented 10 unique studies, as three population cohort retrospective studies in Sweden and Denmark presented data of the same population (Plana-Ripoll et al., Reference Plana-Ripoll, Pedersen, Holtz, Benros, Dalsgaard, de Jonge and McGrath2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Larsen, Kuja-Halkola, Thornton, Yao, Larsson and Bergen2021, Reference Zhang, Kuja-Halkola, Birgegård, Larsson, Lichtenstein, Bulik and Bergen2023). The publication year of the studies ranged from 2016 to 2024. The studies were conducted in European countries (three in the United Kingdom, one in Sweden and Denmark), Africa (one in Kenya, one in Tunisia), Middle East (one in Iran), USA (one) and Australia (one). One study contained data from 18 countries across all the continents. Six studies were cross-sectional studies, three were population-based cohort retrospective studies, two had prospective designs and one study had a retrospective design. Risk of bias scores ranged from 5 to 8 with nine studies rated as high quality and three as moderate quality.

An association between eating pathology and psychotic symptoms was identified in all but one study, by Mohammadi et al. (Reference Mohammadi, Mostafavi, Hooshyari, Khaleghi, Ahmadi, Molavi and Zarafshan2020). Both cross-sectional and retrospective cohort studies demonstrated a strong association between EDs and schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adults and children. Up to 3.7% of children aged 9–10 years presented EDs with psychotic symptoms and 0.8% were currently diagnosed with co-occurring EDs and psychotic disorders (Convertino & Blashill, Reference Convertino and Blashill2022). In a cross-sectional survey, 16.4% to 24.7% of adults who reported psychotic-like experience had signs of EDs (Koyanagi, Stickley, & Haro, Reference Koyanagi, Stickley and Haro2016). Individuals with AN or other EDs were at greater risk of co-occurring psychotic disorder (Rodgers, Marwaha, & Humpston, Reference Rodgers, Marwaha and Humpston2022) or developing schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders in the future (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Larsen, Kuja-Halkola, Thornton, Yao, Larsson and Bergen2021). However, Zhang et al.’s (Reference Zhang, Larsen, Kuja-Halkola, Thornton, Yao, Larsson and Bergen2021) study was the only investigation in our review to identify ED diagnosis preceding a schizophrenia diagnosis.

By contrast, people with premorbid psychotic-like experiences were at greater risk of eating pathology (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Saha, Al-Hamzawi, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet and Kessler2016; Solmi, Melamed, Lewis, & Kirkbride, Reference Solmi, Melamed, Lewis and Kirkbride2018). Of note, 29% of children with psychotic like experiences at age 13 reported disordered eating behaviours by the age of 18 (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Melamed, Lewis and Kirkbride2018) whilst McGrath et al. (Reference McGrath, Saha, Al-Hamzawi, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet and Kessler2016) found that psychotic experiences were associated with subsequent onset of both bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. One longitudinal study demonstrated that the association between psychotic experiences and disordered eating twelve months later in high school students was mediated by body satisfaction and weight preoccupations (Fekih-Romdhane, Houissa, Cheour, Hallit, & Loch, Reference Fekih-Romdhane, Houissa, Cheour, Hallit and Loch2024). Symptoms of paranoia were associated with body and weight concerns (Malcolm et al., Reference Malcolm, Phillipou, Neill, Rossell and Toh2022), while uncontrolled eating was associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic experiences (Koyanagi et al., Reference Koyanagi, Stickley and Haro2016). Psychosis and binge eating disorder were strongly correlated (Mutiso et al., Reference Mutiso, Ndetei, N Muia, K Alietsi, Onsinyo, Kameti and Mamah2022).

Narrative synthesis: eating disorders studies

Nineteen studies with ED clinical populations were included in this review. Three of these studies contained data both on clinical populations with ED and psychosis (Camprodon-Boadas et al., Reference Camprodon-Boadas, De la Serna, Plana, Flamarique, Lázaro, Borràs and Castro-Fornieles2023; Lysaker et al., Reference Lysaker, Chernov, Moiseeva, Sozinova, Dmitryeva, Makarova and Kostyuk2023; Mountjoy, Farhall, & Rossell, Reference Mountjoy, Farhall and Rossell2014). They represent 18 unique studies and two papers reported on the same dataset (De Young et al., Reference De Young, Bottera, Kambanis, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson and Mehler2022; Kambanis et al., Reference Kambanis, Bottera, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson, Mehler and Young2023). Seven studies explored the delusionality of the dominant beliefs of patients with ED and twelve studies explored the association of eating pathology with psychosis or psychotic symptoms. They were published from 1984 to 2023. Nine studies were conducted in USA, five in Italy, two in Greece, one in Spain, one in Australia and one in Russia. Ten studies were cross-sectional studies, seven were case-control studies and two were prospective observational designs. Thirteen studies were of high methodological quality according to Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria – receiving a total score of 8 or 7. Six studies were of medium quality and were rated as 6–5.

Paranoia was associated with disordered eating symptoms (Catone, Salerno, Muzzo, Lanzara, & Gritti, Reference Catone, Salerno, Muzzo, Lanzara and Gritti2021) and patients with AN reported more psychotic symptoms such as paranoia (Pruccoli, Chiavarino, Nanni, & Parmeggiani, Reference Pruccoli, Chiavarino, Nanni and Parmeggiani2023) compared to patients with bulimia nervosa (Lysaker et al., Reference Lysaker, Chernov, Moiseeva, Sozinova, Dmitryeva, Makarova and Kostyuk2023). The most common dominant beliefs in patients with EDs were related to food, body shape, weight fear and fear of losing control (Kambanis et al., Reference Kambanis, Bottera, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson, Mehler and Young2023; Steinglass, Eisen, Attia, Mayer, & Walsh, Reference Steinglass, Eisen, Attia, Mayer and Walsh2007). Likewise, 10%–28.2% patients with ED were classified as having delusional body image beliefs according to the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) (De Young et al., Reference De Young, Bottera, Kambanis, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson and Mehler2022; Kambanis et al., Reference Kambanis, Bottera, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson, Mehler and Young2023; Konstantakopoulos et al., Reference Konstantakopoulos, Varsou, Dikeos, Ioannidi, Gonidakis, Papadimitriou and Oulis2012; Konstantakopoulos, Ioannidi, Patrikelis, & Gonidakis, Reference Konstantakopoulos, Ioannidi, Patrikelis and Gonidakis2020; Mountjoy, Reference Mountjoy, Farhall and Rossell2014), 30.4% had overvalued ideas (Konstantakopoulos et al., Reference Konstantakopoulos, Ioannidi, Patrikelis and Gonidakis2020) and 28%–34% had poor insight (De Young et al., Reference De Young, Bottera, Kambanis, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson and Mehler2022; Kambanis et al., Reference Kambanis, Bottera, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson, Mehler and Young2023; Mountjoy, Reference Mountjoy, Farhall and Rossell2014; Steinglass et al., Reference Steinglass, Eisen, Attia, Mayer and Walsh2007). Delusional beliefs were significantly more frequent in patients with AN compared to patients with bulimia nervosa and controls (Konstantakopoulos et al., Reference Konstantakopoulos, Varsou, Dikeos, Ioannidi, Gonidakis, Papadimitriou and Oulis2012, Reference Konstantakopoulos, Ioannidi, Patrikelis and Gonidakis2020). The preoccupation and distress in relation to the dominant belief was higher in patients with AN compared to patients with schizophrenia (Mountjoy, Reference Mountjoy, Farhall and Rossell2014). A comparative study between patients with AN, first-episode of psychosis and OCD demonstrated that patients with first-psychosis episode and patients with AN reported higher conviction of their belief and delusionality compared to patients with OCD (Camprodon-Boadas et al., Reference Camprodon-Boadas, De la Serna, Plana, Flamarique, Lázaro, Borràs and Castro-Fornieles2023). Patients with delusional beliefs and poor insight reported more disordered eating symptoms (Konstantakopoulos et al., Reference Konstantakopoulos, Varsou, Dikeos, Ioannidi, Gonidakis, Papadimitriou and Oulis2012), more psychotic symptoms (Steinglass et al., Reference Steinglass, Eisen, Attia, Mayer and Walsh2007) more body-checking behaviours, purgative behaviours, restricting eating and fear of fatness (De Young et al., Reference De Young, Bottera, Kambanis, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson and Mehler2022; Kambanis et al., Reference Kambanis, Bottera, Mancuso, Cass, Lohse, Benabe, Oakes, Watters, Johnson, Mehler and Young2023).

Narrative synthesis: psychotic disorders studies

Twelve articles and unique studies that presented data on clinical populations with psychotic disorders were included, of which seven were cross-sectional studies, four case-control, and one prospective observational study. The studies were published between 1985 and 2023. Most of the studies were conducted in the USA (four studies), Middle East (two in Turkey, one in Iran, one in Israel) and in European countries (one in Switzerland, one in Greece). One study was conducted in Asia (Singapore) and one in Africa (Egypt). Risk of bias scores ranged from 5 to 8, with 11 studies of high quality and one of moderate quality.

The findings of the studies in patients with psychosis demonstrated a strong association between psychotic disorders and eating pathology. Patients with psychosis experienced more EDs and disordered eating symptoms compared to controls (Khazaal, Frésard, Borgeat, & Zullino, Reference Khazaal, Frésard, Borgeat and Zullino2006; Khosravi, Reference Khosravi2020; Lyketsos et al., Reference Lyketsos, Paterakis, Beis and Lyketsos1985), with 11.3% to 41.5% of patients with psychosis reporting disordered eating symptomatology (Fawzi & Fawzi, Reference Fawzi and Fawzi2012; Khosravi, Reference Khosravi2020; Stein, Zemishlani, Shahal, & Barak, Reference Stein, Zemishlani, Shahal and Barak2005; Teh et al., Reference Teh, Mahesh, Abdin, Tan, Rahman, Satghare and Subramaniam2021). Patients with disordered eating behaviours reported more and greater psychotic symptoms (Fawzi & Fawzi, Reference Fawzi and Fawzi2012; Malaspina et al., Reference Malaspina, Walsh-Messinger, Brunner, Rahman, Corcoran, Kimhy and Goldman2019; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Zemishlani, Shahal and Barak2005).

Meta–analysis

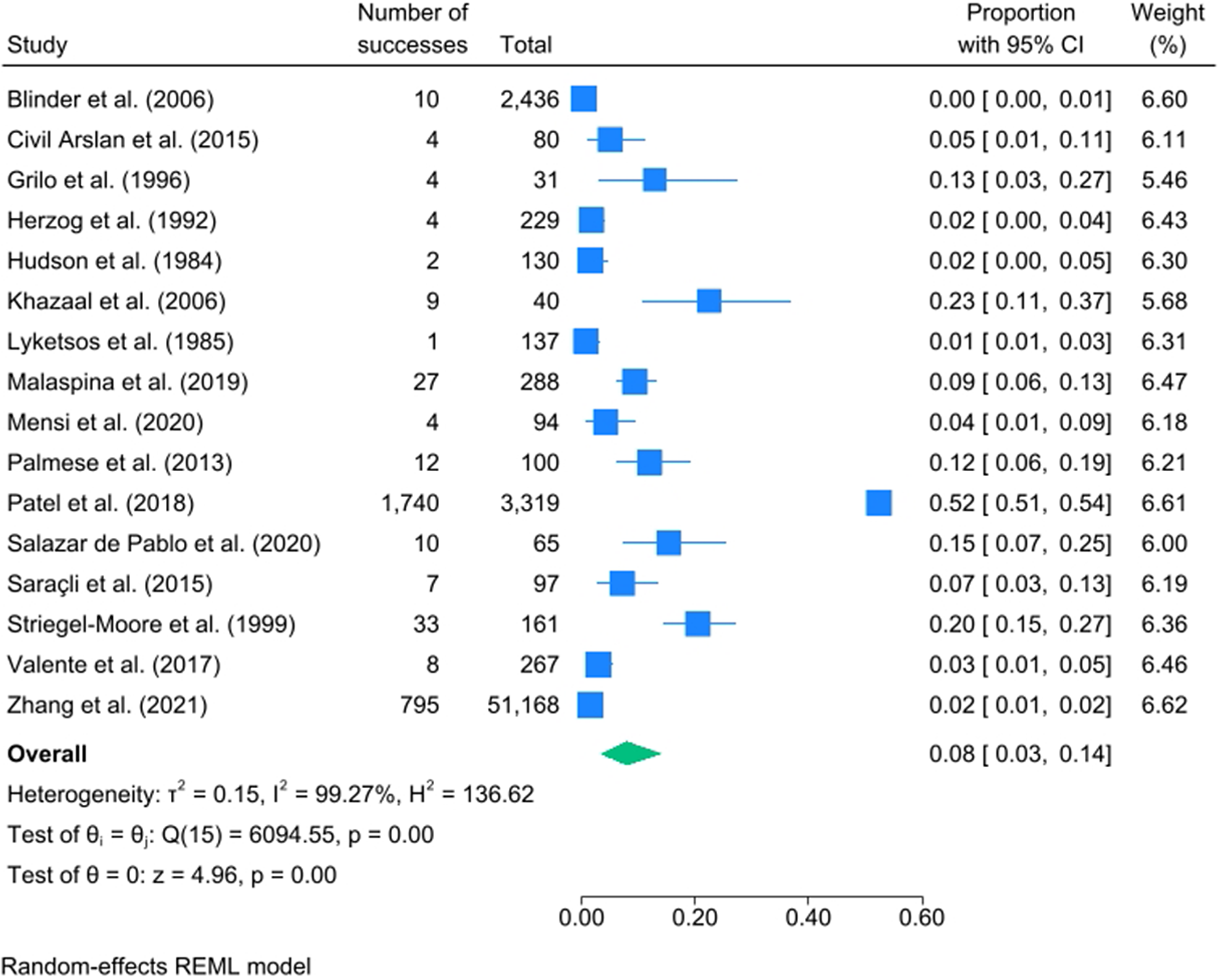

Sixteen studies met inclusion criteria for meta-analysis of the comorbidity between EDs and psychotic disorders (see Figure 2). The mean proportion of comorbidity expressed as a percentage was 8% [95% CI: 3, 14], with high levels of heterogeneity [I2 = 99.27%].

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of comorbidity across eating disorders and psychotic disorders.

Subgroup analysis – Clinical populations with eating disorders

The mean proportion of comorbidity was 8% [95% CI: 2, 19; I2 = 99.13%] across nine studies with clinical populations with EDs (see Appendix F).

Subgroup analysis – Clinical populations with psychosis

The mean proportion of comorbidity was 9% [95% CI: 4, 15; I2 = 84.18%] across seven studies with clinical populations with psychosis (see Appendix G).

Meta-analysis by region

Most studies were from North America or Europe. For North America, the mean proportion of comorbidity was 11% [95% CI: 3, 22; I2 = 99.09%] across nine studies; for Europe the proportion was 4% [95% CI: 0, 11; I2 = 95.16%] across five studies (see Appendices H and I respectively).

Meta-analysis by study type

The mean proportion of comorbidity in cross-sectional studies was 9% [95% CI: 4, 17; I2 = 98.47%; k = 13] and in retrospective studies it was 3% [95% CI: 0, 9; I2 = 94.55%; k = 3] (see Appendices J and K).

Publication bias

Inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test results suggested no presence of publication bias except for the meta-analysis of European studies (k = 5; p value for Egger’s test = 0.03). Funnel plots with results for Egger’s tests are presented in Appendices L-R.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review exploring the association and comorbidity between eating pathology and psychosis across clinical and community populations. Our findings suggest a pooled comorbidity between EDs and psychotic disorders of 8% in our meta-analysis.

Our findings have important clinical and research implications. In terms of the development of EDs and psychosis, high levels of comorbidity could speak to shared aetiological pathways, potentially offering avenues for early intervention. For example, unusual experiences on the psychosis spectrum in early adolescence might represent a risk factor for eating pathology (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Melamed, Lewis and Kirkbride2018), although these findings require replication in further samples. Future cohort studies could shed light on the onset and the prediction of psychosis and EDs through a detailed developmental framework or symptom-focused typology of symptoms associated with the intersections and/or similarities between EDs and psychotic disorders for adolescents. Earlier identification of risk factors for adolescents at higher risk of EDs and psychotic disorders, or increased risk of both due to the presence of symptoms of the other, could offer additional options for earlier intervention and improved treatment outcomes. In terms of EDs, psychological interventions that address experiences such as the ED voice at an early stage, before ED symptoms become entrenched, could help to prevent the onset and maintenance of enduring EDs. Moreover, given the relatively low rates of ED recovery (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Monaco, Højlund, Monteleone, Trott, Firth, Carfagno, Eaton, De Toffol, Vergine, Meneguzzo, Collantoni, Gallicchio, Stubbs, Girardi, Busetto, Favaro, Carvalho, Steinhausen and Correll2024), addressing psychotic-symptoms such as delusions and the ED voice in patients with EDs could represent promising lines for future research. Additionally, low-intensity intervention at an early stage and early age in community children’s mental health services and schools, offering normalising psychoeducation and coping strategy enhancement to promote communication and help-seeking, and reduce symptom related distress and the internalisation of stigma, could improve longer-term outcomes. For patients with psychotic disorders, our findings suggest high rates of ED symptoms, particularly binge eating symptomology, which warrant clinical attention. Waite et al. (Reference Waite, Langman, Mulhall, Glogowska, Hartmann-Boyce, Aveyard, Lennox, Kabir and Freeman2022) identified appearance concerns as a theme in their study of patients with psychosis and their experience of weight gain in the context of antipsychotic treatment, which is a common phenomenon. Further qualitative research is needed to better understand the experiences of such patients, including the potential impact of changes in appetite and weight caused by antipsychotic medication and shifting self-perception through turbulent developmental periods on the development of ED symptoms.

Limitations

An important factor to consider in interpreting our findings is the high degree of both statistical heterogeneity in the meta-analysis, as well as methodological heterogeneity overall. Whilst our meta-analysis only included studies which used either clinical diagnosis or formal interview assessments, studies ranged across a period of 40 years, in which time both diagnostic practice and manuals will have changed. Secondly, studies utilising self-report questionnaires and ‘cut-off scores’ to assess psychosis and eating disorder pathology will provide higher estimates of comorbidity as compared with interview-based assessment methods. Studies using active ascertainment methods will likewise identify higher rates of comorbidity than studies relying on retrospective methods such as registry studies (Uher et al., Reference Uher, Pavlova, Radua, Provenzani, Najafi, Fortea and Fusar-Poli2023). We were unable to conduct a meta-analysis of correlation due to inconsistent measurement and reporting, and we recommend standardised reporting of correlations using Pearson’s r in future studies to aid future meta-analyses.

A further limitation is the lack of validation studies of ED measures in psychosis populations, and psychosis measures in ED populations. Psychometric studies are required and should include qualitative studies to explore content validity, as well as quantitative studies of properties such as factor structure and concurrent validity. Finally, it should be noted that studies have predominantly been conducted in Western countries, with frequent non-reporting of the ethnicity of participants, thereby hampering generalisability. Further research is needed to understand the association between ED and psychosis in diverse populations, including in the Global South, with transparent reporting on social determinants.

Conclusion

Psychotic disorders and EDs represent two serious psychiatric conditions with profound implications for patients, their families and society. Our review suggests that the two conditions are associated, and frequently co-occur in clinical populations. Data from community samples also identify their co-occurrence in childhood and adolescence (e.g. Convertino & Blashill, Reference Convertino and Blashill2022; Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Melamed, Lewis and Kirkbride2018), highlighting the need for further research utilising large datasets to investigate the developmental pathways and early clinical indicators that may be involved in their onset to inform more holistic assessment approaches and preventative intervention options. Finally, our review highlights the potential for new intervention studies to address comorbid symptoms in clinical populations, especially those that may maintain the disorders. Qualitative research and co-design approaches are indicated to develop such interventions in collaboration with people with lived experience of co-occurring ED and psychosis. This approach would help expand knowledge beyond arbitrary diagnoses and treatment pathways, developing a rich and experience-led understanding of the intersections between ED and psychotic disorder onset, presentation, and maintenance to advance identification and treatment options.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172500114X.

Funding statement

This study was supported through funded research time via a National Institute of Health and Social Care Research (NIHR) Development and Skills Enhancement Award NIHR302102 awarded to Tom Jewell. The funder played no role in any aspect of the study, including the decision to conduct this review.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare related to the present work.