Introduction

In 2008, around half of pregnancies were unintended in the ‘less developed’ regions of the world, declining to around 40% in 2012. About a half of these pregnancies ended in an induced abortion (hereafter: abortion); 38% in a live birth; and 13% in a miscarriage (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Singh and Hussain2014). Even though this means many women make the choice between continuing or aborting unintended pregnancies each year, the likelihood of choosing an abortion over an unintended birth, and its interdependence with both individual-level characteristics and country contexts, have not been researched before. Existing studies provide evidence from single countries in Europe (Sihvo et al., Reference Sihvo, Bajos, Ducot and Kaminski2003; Font-Ribera et al., Reference Font-Ribera, Pérez, Salvador and Borrell2007; Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007; Levels et al., Reference Levels, Need, Nieuwenhuis, Sluiter and Ultee2010) or North America (Gomez-Scott & Cooney, Reference Gomez-Scott and Cooney2014) leaving low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) understudied.

For LMICs, there are a few international comparisons of the determinants of unintended pregnancy (Hubacher et al., Reference Hubacher, Mavranezouli and McGinn2008), birth (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998) or abortion (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Singh and Haas1998, Reference Bankole, Singh and Haas1999; Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell and Sedgh2017a), but they treat these events separately rather than examining the process leading to unintended birth or abortion in a single study. Research that examined both abortions and unintended births (Pallitto et al., Reference Pallitto, García-Moreno, Jansen, Heise, Ellsberg and Watts2013) or abortions and unintended pregnancies (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Keogh, Akinyemi, Dzekedzeke, Awolude and Adewole2014) focused only on one specific determinant of these outcomes (intimate partner violence and HIV status, respectively), and used data encompassing only selected regions of the countries. There is a lack of nationally representative studies documenting the process of unintended pregnancy resolution (i.e. experiencing an unintended pregnancy and subsequently choosing an abortion or birth) examining these events across LMICs. This study aimed to fill this gap in the literature by analysing Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) for twelve LMICs.

Following Rossier et al. (Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007) and Coast et al. (Reference Coast, Norris, Moore and Freeman2018), this study approached unintended pregnancy resolution as a process (see Conceptual Framework section). It examined how the likelihood of experiencing an unintended pregnancy rather than an intended pregnancy, and subsequently choosing an abortion or birth, are associated with individual and contextual factors. The focus was on individual reproductive histories: family composition (number and sex of existing children), fertility desires (the difference between the ‘ideal’ and actual family size), contraceptive use before pregnancy and interval since last birth. It also explored how context is associated with unintended pregnancy resolution. A cross-country comparative approach was taken and thus countries were divided into four context groups based on the legal status of abortion and cultural context (see Cultural-Legal Context section): (1) Post-Soviet/communist and (2) Asian countries with liberal abortion legislation, and (3) Asian and (4) Latin American countries with restrictive abortion legislation. Twelve DHSs that had calendar data on the timing and planning status of births, timing of abortions and contraceptive use available were included. Due to the very low number of unintended pregnancies reported among nulliparous women in these data (see Methods) and due to one of the key explanatory variables being time since last birth, the analyses focused on parous women. The study provides new information on unintended pregnancy resolution, and tells policymakers which groups of women might be more likely to experience an unintended birth or abortion.

Unintended pregnancy resolution: current evidence

Previous studies on unintended pregnancy resolution have mostly focused on high-income countries (HICs) and on individual-level socio-demographic characteristics. Reproductive histories in HICs have been associated with unintended pregnancy resolution. In the Netherlands, women who had fewer than two children were more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy than those with more children, but parity was not associated with subsequently choosing an abortion (Levels et al., Reference Levels, Need, Nieuwenhuis, Sluiter and Ultee2010). In France, women in their mid-20s to mid-30s often reported wanting to stop childbearing as the motivation for abortion (Sihvo et al., Reference Sihvo, Bajos, Ducot and Kaminski2003). In some LMICs, such as Zambia and Nigeria, the likelihood of unintended pregnancy increased with parity, whereas those who had no children were much more likely to abort an unintended pregnancy than parous women (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Keogh, Akinyemi, Dzekedzeke, Awolude and Adewole2014). Many studies either did not include parity in their analyses or did not compare results between different parities (Font-Ribera et al., Reference Font-Ribera, Pérez, Salvador and Borrell2007; Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007; Gomez-Scott & Cooney, Reference Gomez-Scott and Cooney2014).

Socioeconomic position’s association with unintended pregnancy resolution has been studied in HICs. In Barcelona, Spain, young women with low education were more likely to choose an abortion rather than unintended birth than those aged 25 years or more with more education (Font-Ribera et al., Reference Font-Ribera, Pérez, Salvador and Borrell2007). In France, young women often chose abortion due to being a student, whereas older women often did so due to their work situation (Sihvo et al., Reference Sihvo, Bajos, Ducot and Kaminski2003). In the United States, adolescent women with strong educational aspirations were more likely to terminate an unintended pregnancy than those without (Gomez-Scott & Cooney Reference Gomez-Scott and Cooney2014).

Relationship status is linked to the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and subsequent decisions to terminate or continue the pregnancy. For instance, French women without a cohabiting partner were less likely to experience an unintended pregnancy, but more likely to subsequently abort one than those with partners (Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007). Unstable partnerships and being single have also been cited as important reasons for abortion in France and Barcelona (Sihvo et al., Reference Sihvo, Bajos, Ducot and Kaminski2003; Font-Ribera et al., Reference Font-Ribera, Pérez, Salvador and Borrell2007).

For LMICs, a multi-country study (fifteen urban/rural sites) showed that intimate partner violence increased the odds of unintended birth and abortion among pregnant women (Pallitto et al., Reference Pallitto, García-Moreno, Jansen, Heise, Ellsberg and Watts2013). A complex relationship between women’s HIV status and experiencing an unintended pregnancy, and subsequently choosing an abortion, was found in three provinces in Nigeria and four states in Zambia (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Keogh, Akinyemi, Dzekedzeke, Awolude and Adewole2014). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study in LMICs has examined in a comprehensive manner the process of unintended pregnancy resolution and its socio-demographic determinants more broadly.

These previous results, albeit very limited, for the most part including both parous and nulliparous women unlike this study, and mostly focused on HICs, were used to identify potentially important individual-level explanatory variables. The focus here is on how the previously understudied aspects of reproductive histories and contraceptive use are associated with unintended pregnancy resolution among parous women.

Role of family composition and contraceptive use in unintended pregnancy, birth and abortion

Unintended pregnancies and births

Family composition (i.e. number, sex and age of existing children) may affect the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and birth. Unintended pregnancy can be mistimed (occurred earlier than desired) or unwanted (occurred when no [more] children were desired) (D’Angelo et al., Reference D’Angelo, Gilbert, Rochat, Santelli and Herold2007). Across ten LMICs, women with no children, or a small number of children at the time of conception, were less likely to classify births as unintended than women with more children (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998). Son preference shapes pregnancy intentions in some countries (Gipson & Hindin, Reference Gipson and Hindin2009; Hussain et al., Reference Hussain, Fikree and Berendes2000; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Sánchez-Barricarte2016). Finally, a short interval since last birth is often associated with reports of mistimed pregnancy, as these are pregnancies that happened earlier than desired (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998).

Contraceptives can be used to prevent unintended pregnancies. Yet, in six LMICs, women using contraception at the time of conception were also relatively likely to report the resulting pregnancy as intended, particularly at lower parities (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Evens and Sambisa2011). A qualitative study in Honduras showed many women who used contraception said that it would not be a problem if they conceived (Speizer et al., Reference Speizer, Irani, Barden-O’Fallon and Levy2009), highlighting the complex relationship between contraceptive use and pregnancy intentions. The type of contraceptive method used can send signals about the strength of motivation to avoid pregnancy, at least if modern contraceptives are widely accepted and easily available. For instance, in the US women with ambivalent or weak intentions to prevent pregnancy used less-effective methods than those with stronger desires (Frost & Darroch, Reference Frost and Darroch2008). In Ecuador, women who used a modern method were more likely to report a resulting pregnancy as unintended (Eggleston, Reference Eggleston1999). However, the relationship is not always clear: another US study found no association between pregnancy intentions and method choice (Schünmann & Glasier, Reference Schünmann and Glasier2006). Other than in Curtis et al. (Reference Curtis, Evens and Sambisa2011), parity was either not studied or not significant in the models.

Abortions

Abortions can be used to postpone, avoid, space or stop childbearing (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Singh and Haas1998). One of the most common reasons for abortion across countries is the desire to limit family size (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell and Sedgh2017a). Among married women in Asia, almost all abortions occur to parous women (spacing/stopping), whereas in Eastern Europe 13–16% of abortions occur to childless women (postponing/avoiding) (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell, Sedgh and Singh2017b). Sex of existing children can also affect abortion decisions, especially if son preference is strong (Edmeades et al., Reference Edmeades, Lee-Rife and Malhotra2010; Puri et al., Reference Puri, Adams, Ivey and Nachtigall2011; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Sánchez-Barricarte2016).

Contraceptive use prior to an unintended pregnancy may be associated with the likelihood of subsequently having an abortion. At the country level, higher use of contraception is typically associated with lower abortion rates, unless the country is in the midst of rapid fertility decline (Bongaarts & Westoff, Reference Bongaarts and Westoff2000). However, at the individual level the associations may differ. In Turkey, propensity to terminate a pregnancy was not found to be associated with the contraceptive method type or non-use among married women of reproductive age (Senlet et al., Reference Senlet, Curtis, Mathis and Raggers2001), but in Bangladesh the use of modern contraceptives was found to be associated with a higher probability of abortion if a pregnancy occurred among parous married women (Edmeades et al., Reference Edmeades, Lee-Rife and Malhotra2010). Women not using contraceptives before an abortion often report not using due to low perceived risk of pregnancy (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Darroch and Henshaw2002; Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Aneblom, Odlind and Tydén2002; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Trussell, Desfreres and Bajos2010) or unmet need for contraception (Westoff, Reference Westoff2005). These studies included both parous and nulliparous women, but did not report the results by parity (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Darroch and Henshaw2002; Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Aneblom, Odlind and Tydén2002; Westoff, Reference Westoff2005; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Trussell, Desfreres and Bajos2010).

Conceptual framework

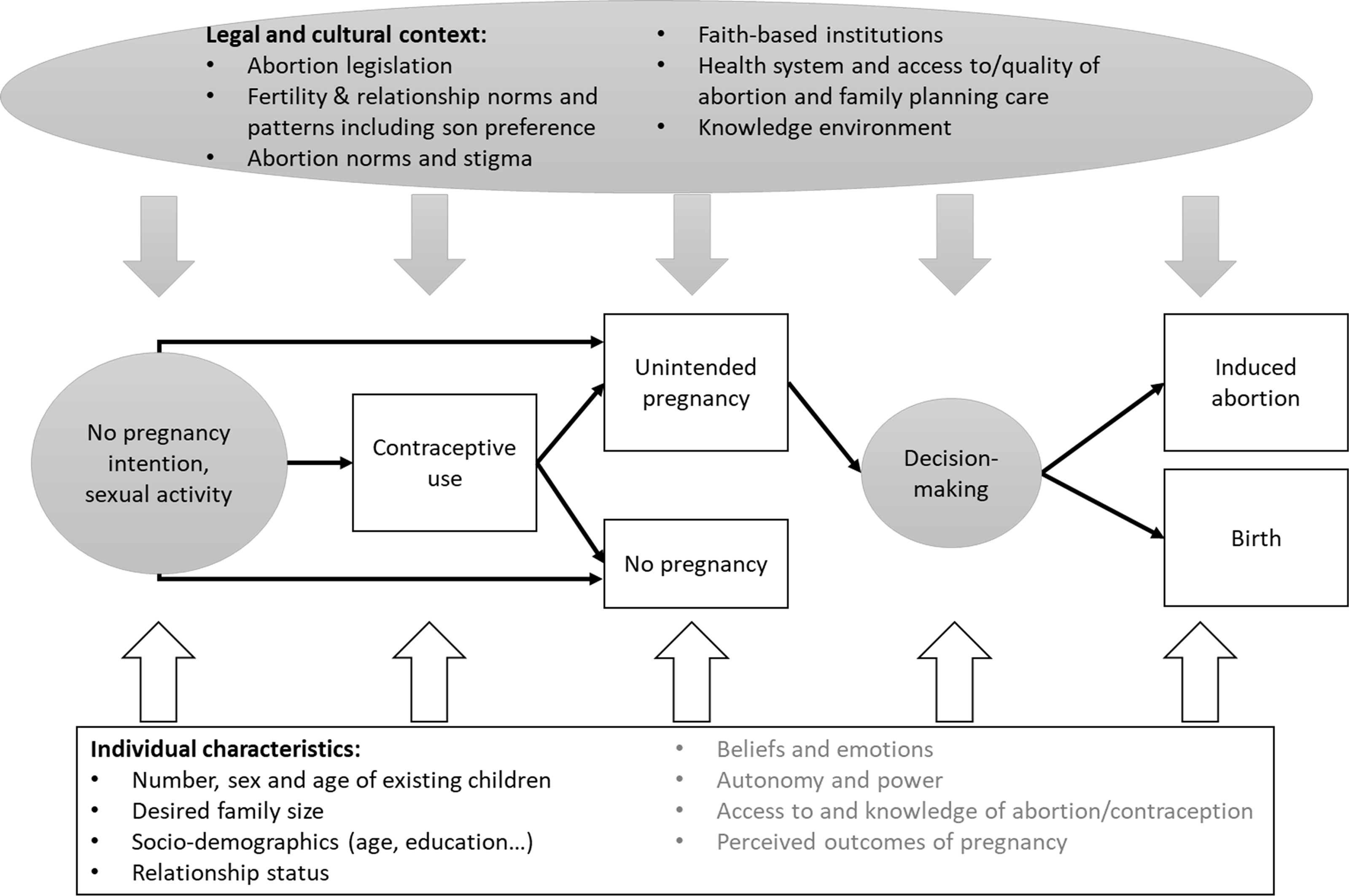

To understand pathways to unintended pregnancy resolution, Coast and colleagues’ (Reference Coast, Norris, Moore and Freeman2018) conceptual framework for understanding trajectories to abortion was combined with Rossier and colleagues’ (Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007) sequential model to analyse the process leading to unintended pregnancies and subsequently abortions. Rossier and colleagues (Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007) break abortion decision-making into five stages: 1) sexual exposure without the intention to become pregnant, 2) contraceptive use, 3) unintended pregnancy, 4) decision to terminate and 5) obtaining abortion services. Each step of the process is influenced by various individual-level as well as legal–cultural characteristics.

Women’s pregnancy intentions and further decisions about terminating or continuing a pregnancy are not independent of the cultural–legal contexts they live in. Legality of abortion, knowledge about legislation, accessibility and quality of reproductive health care, as well as wider norms around abortion and childbearing, affect women’s pathways to abortion (Coast et al., Reference Coast, Norris, Moore and Freeman2018). The legal context can, for instance, affect women’s perspectives regarding whether they would have an abortion if they unintendedly became pregnant: a lower number of abortion restrictions in a state in the US was found to be associated with a higher likelihood to choosing an abortion (Gomez & Acara, Reference Gomez and Acara2018). However, at a population level, restrictive abortion legislation does not reduce abortion levels in any significant way, but it does increase unsafe abortions (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Bearak, Singh, Bankole, Popinchalk and Ganatra2016).

Cultural abortion stigma influences unintended pregnancy resolution. In some contexts, pregnant women who do not wish to have a child may not choose an abortion due to the stigma attached to it (Tsui et al., Reference Tsui, Casterline, Singh, Bankole, Moore and Omideyi2011; Arambepola & Rajapaksa, Reference Arambepola and Rajapaksa2014). Elsewhere, however, stigma attached to a childbirth in specific circumstances (e.g. out of wedlock) can be larger than that attached to an abortion, leading women to choose termination (Johnson-Hanks, Reference Johnson-Hanks2002). Abortion stigma increases under-reporting of abortion (Tierney, Reference Tierney2019). The legal context can affect abortion stigma and consequently reporting of abortion: women may wish to conceal clandestine abortions more strongly than legal ones.

When it comes to the health system, cost and availability of effective contraceptive methods is associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancies (Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007; Levels et al., Reference Levels, Need, Nieuwenhuis, Sluiter and Ultee2010) and many such pregnancies result from unmet need for contraception (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Sahin-Hodoglugil and Potts2006). Non-use can be related, for instance, to cost of methods and lack of availability, fear of side-effects, misinformation/lack of information, provider biases or women’s limited decision-making possibilities (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Sahin-Hodoglugil and Potts2006; Sedgh & Hussain, Reference Sedgh and Hussain2014). Among those who use contraception, an unintended pregnancy might result from a method failure (Black et al., Reference Black, Gupta, Rassi and Kubba2010).

Following the conceptual framework (Figure 1), the unintended pregnancy resolution process was examined sequentially. First, the analyses estimated the likelihood of experiencing an unintended pregnancy followed by estimating the likelihood of choosing an abortion among those who experienced an unintended pregnancy, while controlling for contraceptive use in the month before conception and other socio-demographic characteristics.

Figure 1. Pathways to unintended pregnancy resolution: a conceptual framework adapted from Coast et al. (Reference Coast, Norris, Moore and Freeman2018) and Rossier et al. (Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007). Grey background/text means it was not possible to explicitly measure this in the study models.

Cultural–legal context

To understand the importance of the cultural–legal context on unintended pregnancy resolution, the twelve countries were divided into four contextual groups based on geographical location (Asia vs Latin America); geo-political history (post-Soviet/communist countries vs other countries) to approximate cultural similarity; and legal status of abortion (‘liberal’ if abortion is available on request/socioeconomic grounds, and ‘restrictive’ if abortion is allowed only based on health or threat to life or not at all) to crudely account for access to abortion and likely under-reporting patterns for abortion. Post-Soviet/communist countries were included as a separate group because they traditionally have lower abortion stigma than most other countries (Popov, Reference Popov1991; Popov et al., Reference Popov, Visser and Ketting1993; Agadjanian, Reference Agadjanian2002; Westoff et al., Reference Westoff, Sullivan, Newby and Themme2002). Thus, the resulting groups were: 1) Post-Soviet/communist countries (Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Ukraine) with liberal abortion legislation, 2) Asian counties with liberal abortion legislation (Bangladesh, Cambodia and Nepal), 3) Asian countries with restrictive abortion legislation (Indonesia and the Philippines), and 4) Latin American countries with restrictive abortion legislation (Bolivia and Colombia).

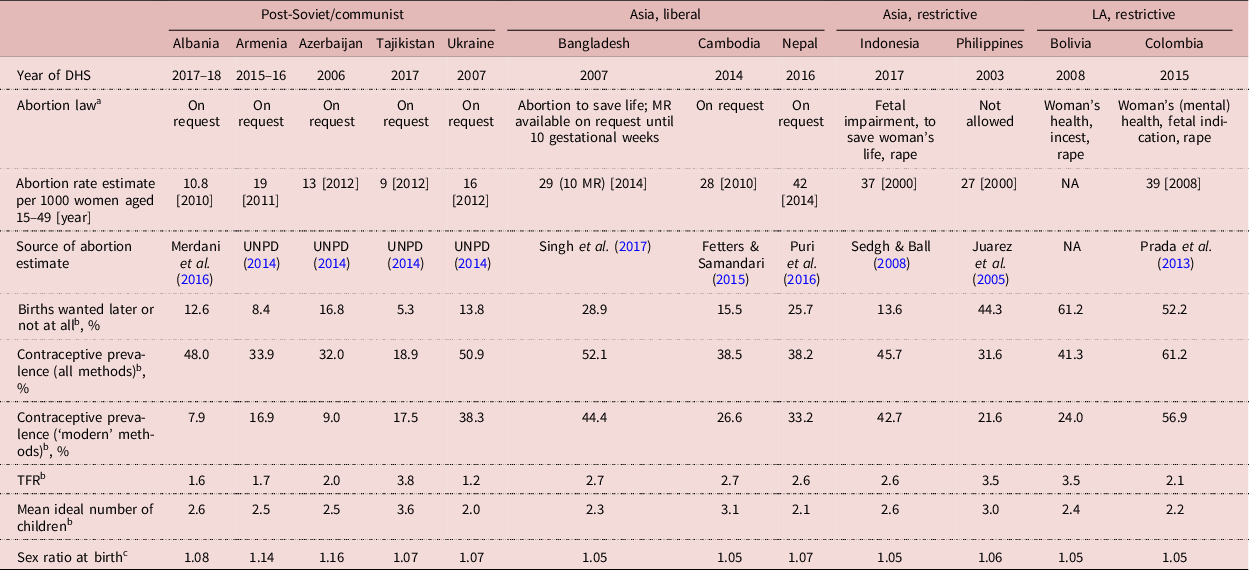

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of each country. The countries differ in their levels of unintended births, (modern) contraceptive prevalence and the mean desired number of children. Armenia and Azerbaijan have a high sex ratio at birth, meaning more boys than expected are born, which may indicate use of sex-selective abortion. In terms of similarities, all the countries are in the last two stages of fertility transition, as the mean ideal number of children varies from 2.0 in Ukraine to 3.6 in Tajikistan. As unintended pregnancies and consequently abortions tend to be more common at the later stages of the transition (Bongaarts & Casterline, Reference Bongaarts and Casterline2018), women in all these countries are exposed to a risk of an unintended pregnancy for significant periods throughout their lives.

Table 1. Summary of country contexts

a Source: worldabortionlaws.com and https://www.guttmacher.org/report/menstrual-regulation-postabortion-care-bangladesh.

b Source: statcompiler.com/en/.

c Source: World Population Prospects 2017 (https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html) (for years 2010–15).

NA = not available; MR = Menstrual regulation; LA = Latin America; UNPD = United Nations, Population Division.

The prevalence of unintended pregnancies and abortions varies by context. In 2012, the share of pregnancies that were unintended was 62% in South America, 36% in South-central Asia, 44% South-eastern Asia and 52% in Eastern Europe. South America had the highest regional level of unintended pregnancies ending in births (46%) compared with the other regions discussed in this paper: South-central Asia (40%), South-eastern Asia (31%) and Eastern Europe (15%) (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Singh and Hussain2014). Abortion rates per 1000 women aged 15–44 vary across the regions too. In 2010–14, in South and Central Asia the rate was 37/1000, in South-eastern Asia 35/1000, in South America 47/1000 and in Eastern Europe 42/1000 (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Bearak, Singh, Bankole, Popinchalk and Ganatra2016).

Methods

Twelve countries were chosen based on DHS calendar data on the timing and planning status of births, timing of abortions and contraceptive use being available. Surveys that only interviewed ever-married women were excluded. If a country had more than one eligible survey, the most recent one was used. The surveys span the years 2003–17 (Table 1) and most regions covered by the DHSs. These surveys include retrospective data on whether any births in the last 5 years were wanted then (wanted birth), wanted later (mistimed) or not wanted at all (unwanted) at the time of conception (DHS, 2013). Mistimed and unwanted births were analysed as one category of ‘unintended birth’ due to small numbers in each more precise category. The surveys also asked whether (the most recent) terminated pregnancies were abortions, miscarriages or stillbirths. It was assumed all abortions were unintended pregnancies, although sometimes they may have been initially wanted, but terminated due to change in life circumstances or medical reasons.

Researching unintended pregnancies, births and abortions is challenging. Women may not want to report an existing child as unwanted: there are discrepancies between retrospective and prospective reports (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Acharya, Singh and Roy2006). However, the validity of the measure is high, at least in HICs (Bachrach & Newcomer, Reference Bachrach and Newcomer1999; Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Kaestner and Korenman2002). Although evidence from DHSs is lacking, in HICs sometimes more than half of abortions are not reported in surveys (Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Bajos and Bouyer2004; Jones & Kost, Reference Jones and Kost2007; Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Kost, Maddow-Zimet, Desai and Zolna2020). It is difficult to estimate the proportion of under-reported abortions if abortion is not legal, but it is likely to be even more severely under-reported. Surveys also miss reports from women who died due to complications of unsafe abortion (N’Bouke et al., Reference N’Bouke, Calvès and Lardoux2012), which are more common where abortions are legal only under restricted or no circumstances. Although not all unintended pregnancies are captured in retrospective surveys, most countries do not collect prospective longitudinal data on pregnancy intentions. While abortion data are often under-reported, only a few Scandinavian countries have medical registers that can be used to study abortion without under-reporting. Therefore, retrospective self-reports are the only way to study the topic in LMICs from a cross-country comparative perspective.

The DHSs selected for this study interviewed 207,472 women. The analytical sample excluded women (in the following order) who were younger than age 15 (N = 2739), whose last pregnancy outcome was a miscarriage/stillbirth or missing (N = 5555), who had no pregnancy during the 5-year DHS calendar (N = 135,908) and who had no children (N = 20,353). The final analytic sample thus included parous women who had a pregnancy that ended in a birth or abortion during the 5-year DHS calendar (N = 42,917). Women without any pregnancies during the 5-year period were excluded, as information on their pregnancy intentions was not available. Nulliparous women were excluded, because interval since previous birth, which is one of the key explanatory variables, is not meaningful for them, and because they reported few unintended births (apart from the two Latin American countries) and very few abortions (in all countries) (see Table 2). Sensitivity analyses including nulliparous women often failed to converge.

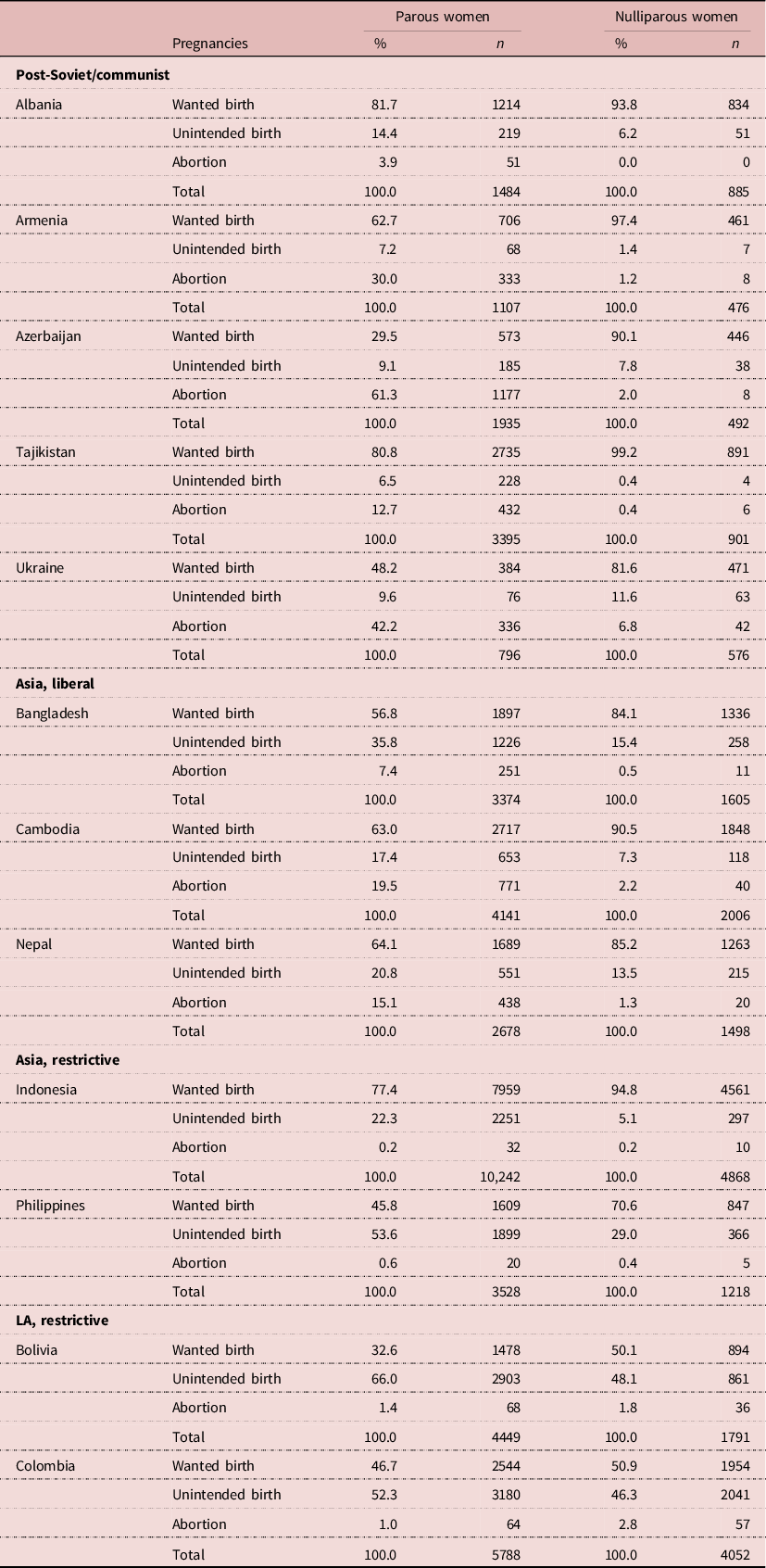

Table 2. Pregnancy outcomes by women’s age and parity

The women in the analytic sample were on average older (31 years) than those excluded (30 years), had a higher desired family size (2.8 vs 2.4), were less likely to have higher education (15.3% vs 23.2%) and less often belonged to the richest 20% of the sample (17.0% vs 23.4%) (data available on request).

There were two binary outcome variables extracted from the DHS calendar: whether a woman’s most recent pregnancy was unintended (i.e. unintended birth or abortion), and who chose an abortion among those who experienced an unintended pregnancy. The study only considered the most recent pregnancy, because the DHS calendar only collects data for the 5 years preceding the survey and thus left-censoring was high. Moreover, in DHSs, unintended pregnancies are more likely reported for more recent births (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998), so using data from most recent events is likely to reduce under-reporting.

The main independent variables included: family sex composition (has at least one child of each sex, has boy(s) only or has girl(s) only); number of living children (1–2, or 3 or more children; family size measured before the outcome pregnancy); whether used contraceptives in the month before the outcome pregnancy (non-use; less-effective methods, i.e. barrier and traditional; more-effective methods i.e. pill, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) or sterilization); interval between the outcome pregnancy and the end of preceding birth (short <19 months, medium 19–36 months or long >36 months); and desired number of children (whether the woman had her exact desired family size before the most recent pregnancy; had fewer children than desired; or had more children than desired). The last variable is the difference between the number of living children before the outcome pregnancy and the desired family size (based on question ‘If you could go back to the time you did not have any children and could choose exactly the number of children to have in your whole life, how many would that be?’) reported at the time of survey. Thus, the assumption was that these preferences did not change as a result of the most recent pregnancy. This was a necessary compromise, since internationally comparable data collecting prospective longitudinal data on such preferences was not available.

The analyses also controlled for socio-demographic characteristics that have been shown to be associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancies and abortions. These variables were: education (up to primary, secondary or tertiary); wealth (DHS wealth index quintiles) (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Singh and Haas1999; Eggleston, Reference Eggleston1999; Font-Ribera et al., Reference Font-Ribera, Pérez, Salvador and Borrell2007; Barden-O’Fallon et al., Reference Barden-O’Fallon, Speizer and White2008; Väisänen Reference Väisänen2015; Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell, Sedgh and Singh2017b); place of residence (urban/rural) (Prada et al., Reference Prada, Singh, Remez and Villarreal2011); age (continuous variable) (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998; Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell, Sedgh and Singh2017b); and partnership status (no partner vs married/cohabiting) (Adetunji, Reference Adetunji1998; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Singh and Haas1999; Westoff et al., Reference Westoff, Sullivan, Newby and Themme2002; Sundaram et al., Reference Sundaram, Juarez, Bankole and Singh2012).

Binary logistic regression was used to study which characteristics were associated with (i) the likelihood of experiencing an unintended pregnancy (vs a wanted pregnancy) and (ii) choosing an abortion among those who experienced an unintended pregnancy. Both models included the same explanatory variables apart from partnership status, which was not included in the second model due to a very low number of unpartnered women in it. The analyses were conducted separately by country. Interactions between parity and desired family size were tested, but they were not significant.

There were missing data for desired family size (N missing = 1351), birth interval (N missing = 157) and contraceptive use (N missing = 1133). Since there was no more than 2.6% of data missing in any of these variables in the analytical sample, ‘missingness’ was treated with listwise deletion.

Results

Descriptive statistics

In the post-Soviet/communist contexts of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Ukraine, the proportion of pregnancies reported as abortions was larger than those reported as unintended births (Table 2). The most extreme case was Azerbaijan, where 61% of the outcome pregnancies ended in an abortion, and only 30% of pregnancies were wanted births. Albania stands out in this group, as women were more likely to report an unintended birth than an abortion.

In the liberal Asian contexts, 7–20% of pregnancies were reported as abortions (Table 2). In Bangladesh, a higher percentage of women reported unintended births (36%) than in Cambodia (17%) and Nepal (21%). In Cambodia and Nepal, abortions and unintended births were almost equally common. In Bangladesh, unintended births were more common than abortions.

Reporting abortions was extremely rare in the Asian and Latin American restrictive contexts (0.2–1.4% of pregnancies) indicating high levels of under-reporting (Table 2). Three of these four countries reported relatively many unintended births (52–66% of pregnancies), but in Indonesia the level was lower (22%).

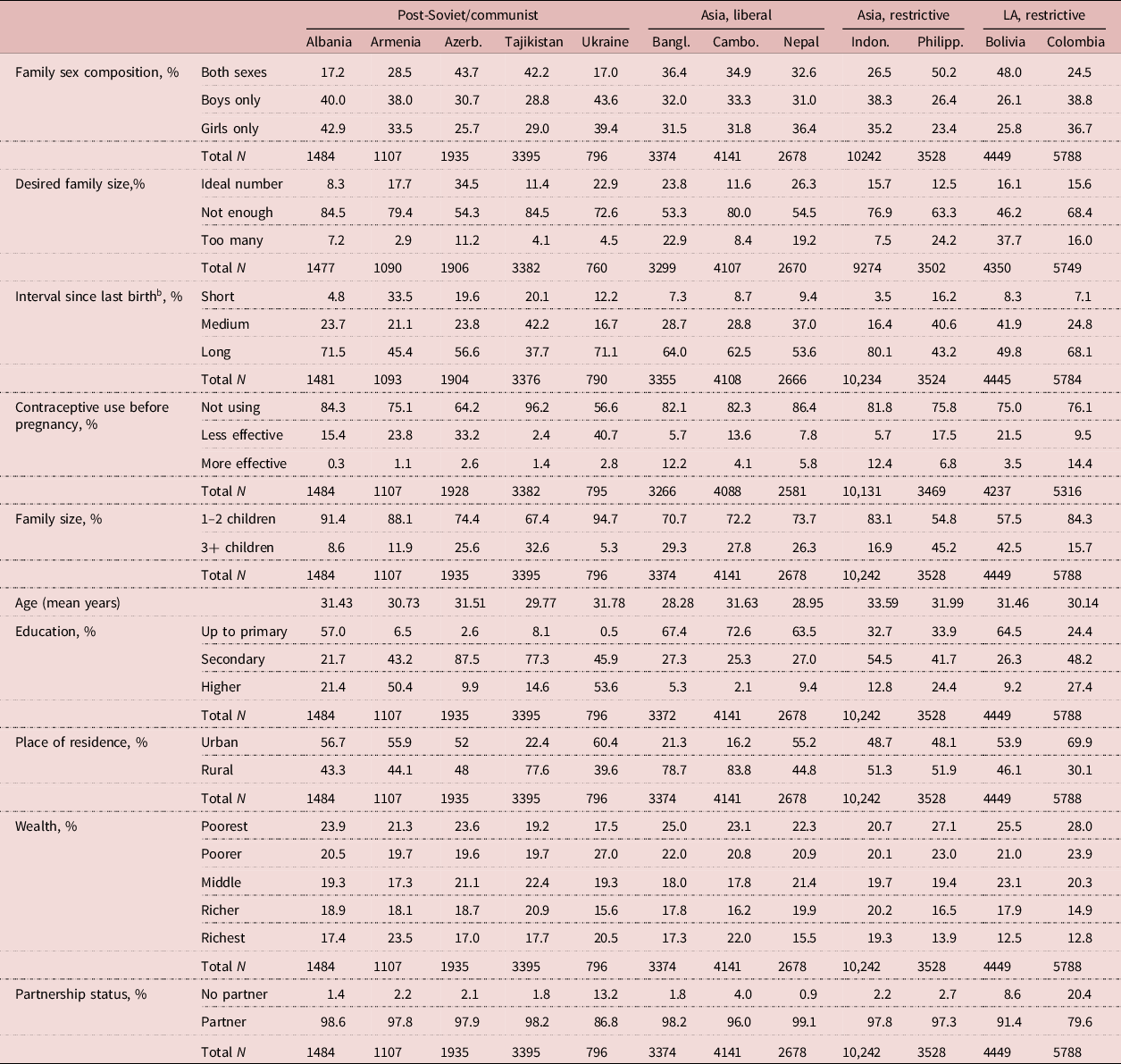

Table 3 shows the distribution of the explanatory variables among the analytic sample by country. The proportion of families with children of both sexes varied from 17% in Ukraine to 50% in the Philippines, partly reflecting the parity levels in the countries: while 95% of women had one or two children in Ukraine, in the Philippines this was only the case for 55% of the analytic sample. Almost four in ten women (38%) in Bolivia had exceeded their desired ideal family size, compared with 3% in Armenia. Most women in the analytic sample (46–85% depending on country) had not yet reached their ideal family size. The vast majority of women were not using any contraception the month before pregnancy (57% or more depending on country).

Table 3. The distribution of explanatory variables by country among the analytic sample, %/mean (N) a

a Column parentages add up to 100%.

b Short interval, <19 months; medium interval, 19–36 months; long interval, 37+ months.

LA = Latin America.

On average women were in their late 20s or early 30s in the study sample. Educational levels varied vastly by country, as did the proportion of the sample living in urban/rural areas. In most countries, women in the analytic sample were more likely to belong to the poorer rather than richer wealth quintiles. Only a small proportion of the sample did not have a partner at the time of the survey (Table 3).

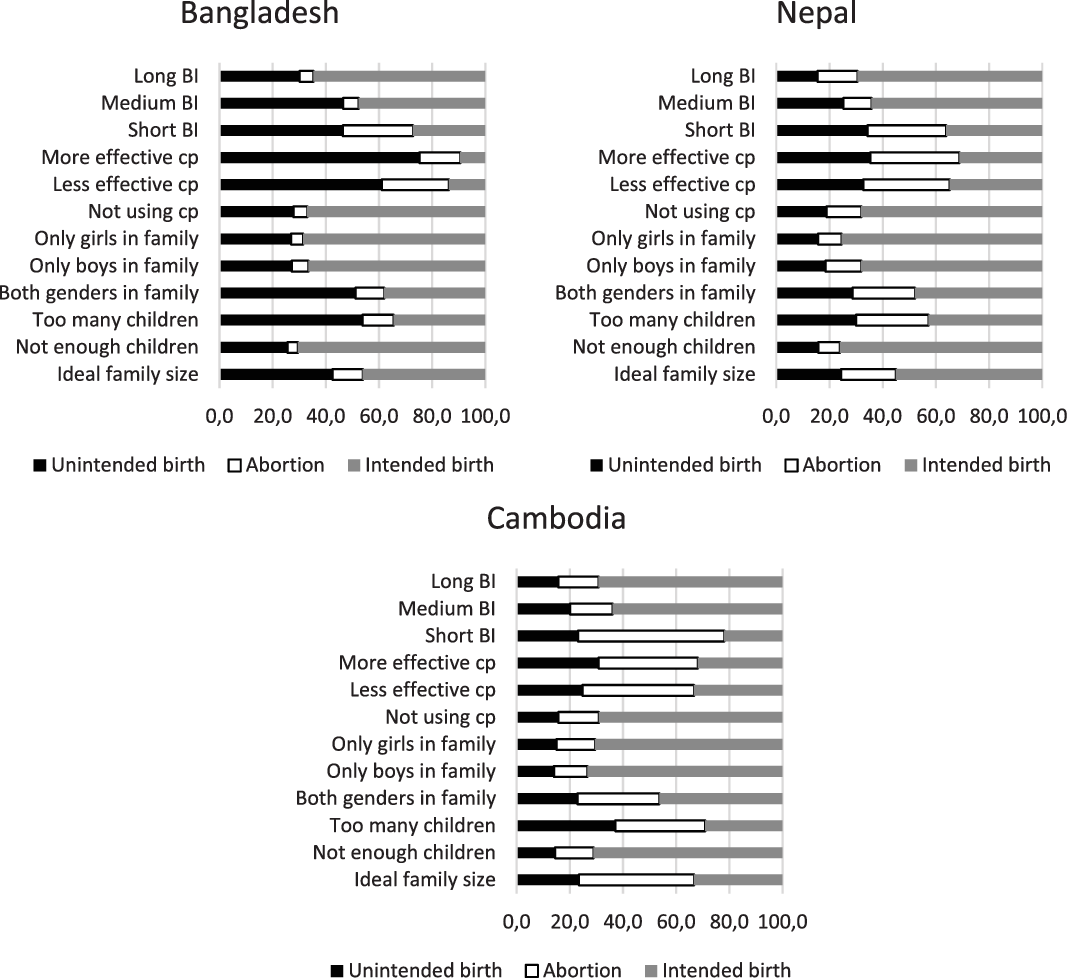

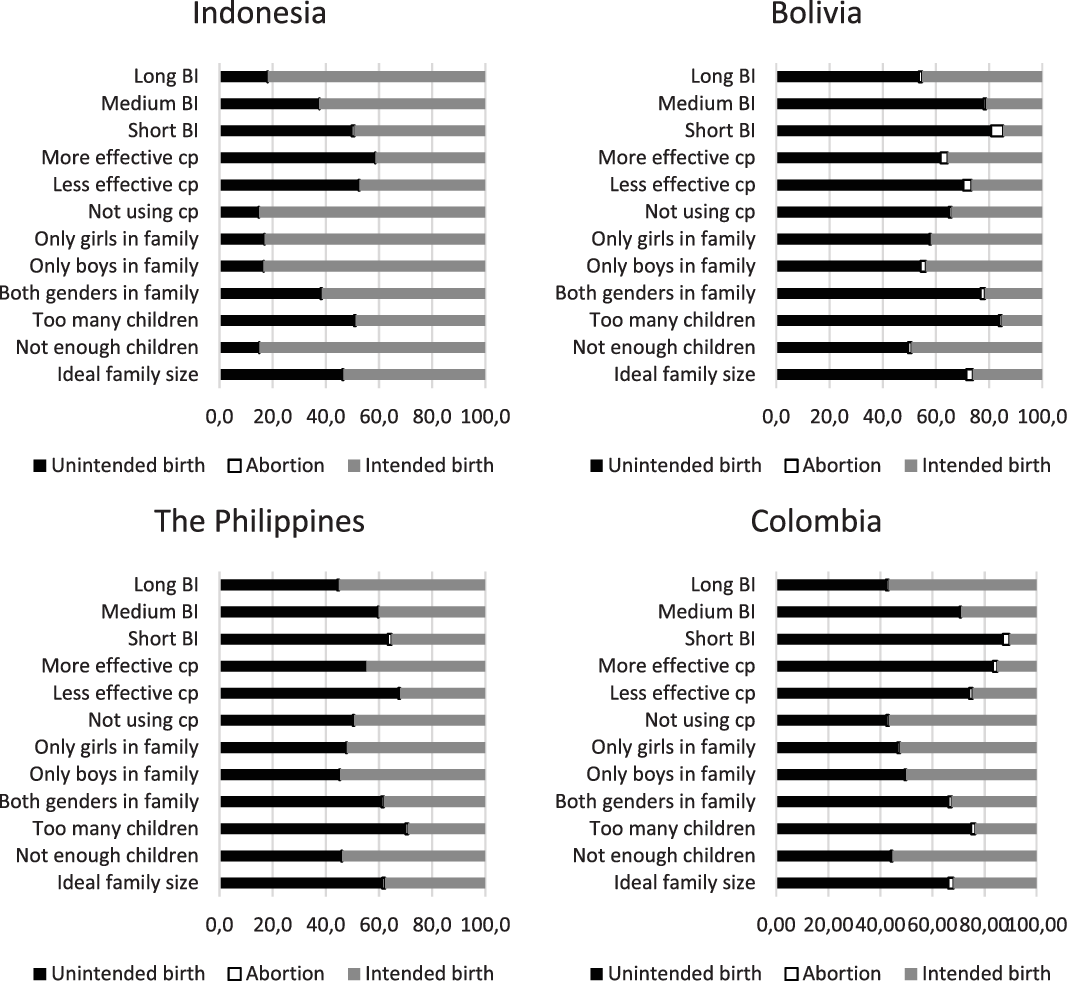

Figures 2–4 show how the pregnancy outcomes were associated with family composition and contraception by country context groups. All associations were statistically significant (p<0.001 in all countries). Some patterns varied little across contexts. Those who had not yet reached their desired family size were less likely to experience an unintended birth than those who had. For example, in Albania, the percentage of unintended births among women who had reached their ideal family size was around 22, whereas women who were below (13%) or had exceeded (18%) their ideal family size experienced fewer such pregnancies. In all countries, women who had children of only one sex were more likely to report an intended birth than those who had children of both sexes (e.g. in Albania, 66% of pregnancies to women with children of both sexes were wanted births, whereas the figures were 83% and 87% for those with boys or girls only, respectively). In all countries, a short interval since last birth was associated with more reported unintended births and abortions than long or medium intervals. Using contraception during the month before the outcome pregnancy was associated with more reported abortions and unintended births (combined) than wanted births in most countries (Figures 2–4). However, in Albania and Tajikistan, most women who had used contraception nevertheless reported the pregnancy as wanted. In Albania, all women who had used more-effective methods and 72% of those using less-effective methods reported a wanted birth (Figure 2). The corresponding percentages were 82% and 73%, respectively, in Tajikistan (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentages of unintended births, abortions and intended births by family composition and pregnancy history, post-Soviet/communist countries. All bivariate associations significant at p < 0.001; BI = birth interval; cp = contraception.

Figure 3. Percentages of unintended births, abortions and intended births by family composition and pregnancy history, liberal Asian countries. All bivariate associations significant at p < 0.001; BI = birth interval; cp = contraception.

Figure 4. Percentages of unintended births, abortions and intended births by family composition and pregnancy history, restrictive Asian and Latin American countries. All bivariate associations significant at p<0.001; BI=birth interval; cp=contraception.

Likelihood of unintended pregnancy

According to the regression models, in both liberal and restrictive Asian and Latin American contexts, women who only had children of one sex were less likely than those with children of both sexes to experience an unintended pregnancy. Only in Colombia was the effect of having girls only not statistically significant. For instance, in Bangladesh, the odds of reporting an unintended pregnancy were 57–66% lower among those with boys or girls only, respectively, than among those with children of both sexes. In the post-Soviet/communist context, the results were similar, apart from Ukraine, where sex composition was not associated with unintended pregnancy. In Albania only those having only girls were less likely to report an unintended pregnancy than those with girl(s) and boy(s) (Table 4).

Table 4. The likelihood of an unintended pregnancy, odds ratios (ORs)

a Short interval, <19 months; medium interval, 19–36 months; long interval, 37+ months.

Bold ORs significant at 5% level; LA = Latin America.

Sensitivity analyses including only multiparous women checked whether these results were driven by women with only one child (not shown, available on request). The odds ratios stayed qualitatively the same, but the statistical significance of the effect of having only boys compared with having both sexes was no longer significant in Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Nepal, but having girls only was still significant. In Bolivia and Cambodia, having only girls compared with having both sexes became non-significant, but having boys only was still significant. In Armenia and Colombia the effect was no longer significant at all. In Albania, Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Philippines both odds ratios and significance stayed similar.

In all countries, the likelihood of an unintended pregnancy was lower among those who had not yet reached their desired family size than among those who had (ORs from 0.07 to 0.49 depending on country). Interestingly, in the post-Soviet/communist contexts of Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine, the likelihood of an unintended pregnancy was lower among those who had exceeded their desired family size than among those who had reached the exact desired size (Table 4). This result should be examined in more detail in future studies with richer datasets, or in qualitative studies, to explain why the pattern was observed.

There were no clear contextual patterns by parity. In most countries those with more than two children were more likely to report an unintended pregnancy than those with smaller families, or there was no effect. Armenia and the Philippines stand out, because women with larger families were less likely to report an unintended pregnancy than women with 1–2 children (OR = 0.48 and OR = 0.74, respectively) (Table 4).

In all countries except Albania, a short birth interval was positively associated with the likelihood of an unintended pregnancy (ORs from 2.20 to 10.67 depending on country), and in most countries (excluding Azerbaijan) a long birth interval was negatively associated with it (ORs from 0.33 to 0.66) (Table 4).

In all countries except Tajikistan, compared with non-use, having used less-effective contraception the month before the outcome pregnancy was positively and strongly associated with the likelihood of experiencing an unintended pregnancy (ORs from 1.99 to 18.14). Having used more-effective methods was also positively associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancy, with the exceptions of the post-Soviet countries of Albania, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, as well as the Philippines, where there was no effect (Table 3).

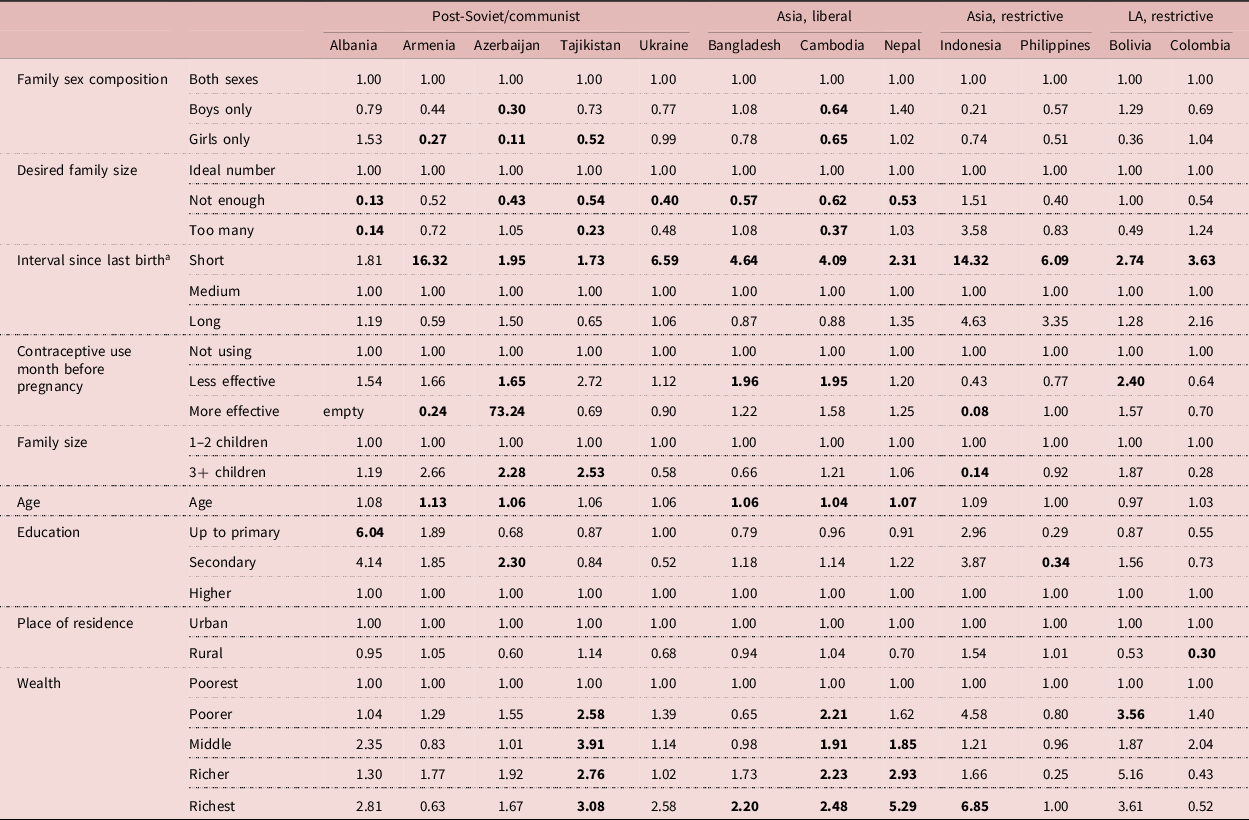

Likelihood of abortion among women who had an unintended pregnancy

In the restrictive settings of Asia and Latin America, there was no statistically significant association between family sex composition and the likelihood of choosing an abortion over unintended birth (Table 5). This was true also for Albania and Ukraine among the post-Soviet/communist group, whereas in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan having only girls was associated with a smaller likelihood of choosing abortion than having children of both sexes (ORs from 0.11 to 0.52 depending on country). In Azerbaijan, this was true also for families with boys only (OR = 0.30). Among the liberal Asian contexts, family sex composition was only significant in Cambodia, where having children of one sex only (whether girls or boys) was associated with a lower likelihood of abortion compared with those with children of both sexes (OR = 0.62 and OR = 0.37 for boys and girls only, respectively).

Table 5. The likelihood of an abortion among those who had an unintended pregnancy, odds ratios (ORs)

a Short interval, <19 months; medium interval, 19–36 months; long interval, 37+ months.

Bold ORs significant at 5% level; LA = Latin America.

Again, sensitivity analyses including only multiparous women checked whether these results were driven by women with only one child. The results were no longer significant for most countries, apart from Azerbaijan and Nepal. In Azerbaijan those with only girls were less likely to choose abortion, whereas in Nepal those with only boys more likely to do so (not shown, available on request).

In the restrictive settings of Asia and Latin America, no statistically significant association between desired family size and choosing an abortion was detected (Table 5). In all liberal contexts apart from Albania, those who had not yet reached their ideal family size were less likely to abort an unintended pregnancy than those who had (ORs 0.13–0.62 depending on country). Interestingly, in Albania, Tajikistan and Cambodia those who had exceeded their ideal family size were less likely to abort than those who had the exact ideal family size before the outcome pregnancy (ORs from 0.14 to 0.37).

In all countries except Albania, the odds of abortion were higher among those who had a short birth interval than those with a medium interval (ORs from 1.73 to 16.32 depending on country) (Table 5).

The results regarding contraceptive use month before the pregnancy were mixed. In most counties, the effect was not significant. Having used less-effective contraception before the outcome pregnancy was positively associated with the likelihood of an abortion in Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Bolivia. Having used more-effective contraception before the outcome pregnancy was positively associated with the likelihood of an abortion in Azerbaijan, but negatively in Armenia and Indonesia (Table 5).

Family size was only significant in the two post-Soviet/communist countries of Azerbaijan (OR = 2.28) and Tajikistan (OR = 2.53), where those who had three or more children were more likely to have an abortion than those who had 1–2, whereas in Indonesia those with larger families were less likely to choose abortion than those with smaller families (Table 5).

Discussion

Individual-level characteristics with similar effects across contexts

Many of the characteristics associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancy, and some characteristics for subsequently choosing abortion, were similar regardless of context. In most countries, a short interval since last birth was associated with a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancy and abortion. This shows women wish to space their pregnancies and many will use abortion to do so. While the association between a short birth interval and unintended pregnancy can partly be explained by our definition of unintended pregnancy (i.e. it includes mistimed pregnancies taking place earlier than desired), it is important to note that it is also associated with decisions of whether to continue or terminate such pregnancy, as shown by the association between short birth interval and a higher likelihood of abortion.

As expected, in all countries women who had not reached their desired family size were less likely to report their most recent pregnancy as unintended than those who had reached it. In addition, having completed one’s desired family size was associated similarly with experiencing an unintended pregnancy and deciding to terminate it in countries with liberal abortion legislation. Regardless of context, women preferred to have children of both sexes, as their likelihood of reporting an unintended pregnancy was lower if they only had children of one sex (apart from Ukraine). These results are in line with studies in Pakistan (Hussain et al., Reference Hussain, Fikree and Berendes2000) and India (Edmeades et al., Reference Edmeades, Lee-Rife and Malhotra2010), where even despite strong son preference couples expressed a desire to have a daughter as well. However, some of these associations may have been driven by women with only one child preferring to have a second birth, as some of the significant associations disappeared once women who only had one child before the outcome pregnancy were removed from the model. In Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Colombia and Nepal women were happy to settle for two (or more) boys or (at least) one child of each sex, but less happy to settle for two or more girls only. In Bolivia and Cambodia, women were happy to settle for two (or more) girls or (at least) one child of each sex, but less happy to settle for two (or more) boys only.

There were no significant associations between family sex composition and the likelihood of choosing an abortion among women with at least two children apart from in Azerbaijan, where those with two (or more) girls were less likely to choose an abortion than women with other sex combinations, signalling son preference – sex ratio at birth is high in Azerbaijan (Table 1). In other contexts, sex of existing children did not seem to be an important factor when women weigh their abortion decisions, although some of the associations may have failed to reach statistical significance due to under-reporting. More studies on the topic are needed.

Using less-effective contraceptive methods was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting an unintended pregnancy than not using any method in all countries except Tajikistan. It shows that there is a complex link between using a contraceptive method and experiencing an unintended pregnancy. The desire to avoid a pregnancy may lead women to use a contraceptive method, but using traditional or barrier methods may result in a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancy among this group due to higher failure rates.

Unintended pregnancy resolution within different legal and cultural contexts

There were some contextual patterns in women’s experiences of unintended pregnancy and abortion. In all countries where abortion legislation was restrictive, reporting of abortion was lower than in countries where legislation was liberal. Given that estimates of abortion levels worldwide show that observed incidence of abortion is not lower in countries with restrictive legislation (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Bearak, Singh, Bankole, Popinchalk and Ganatra2016), these results reflect heterogeneity in under-reporting of abortion in surveys by legal context. More-restrictive legislation is probably correlated with higher abortion stigma, resulting in more under-reporting. Therefore, some of the results, particularly in the abortion models, were affected by this variation in reporting. This indicates that the cultural–legal context, including perceived abortion stigma in the conceptual framework (Figure 1), has important implications, not only for women’s unintended pregnancy resolution experiences, but also their likelihood to report the event.

Using less-effective contraceptive methods in the month before conception was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting an abortion, apart from in countries where abortion legislation was restrictive. Thus, in contexts with liberal abortion legislation there might be a similar link between using a contraceptive method and wanting to avoid childbearing, as observed for an unintended pregnancy: women use a method to avoid pregnancy, but risk experiencing one due to the relatively high failure rates. In countries where abortion legislation is restrictive, the relationship might be different, or the lack of association may be due to low statistical power following under-reporting of abortion.

In the post-Soviet contexts of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, those with girls only were less likely to abort than those with children of both sexes. These results were partly driven by those with only one child. When only multiparous women were included, this result remained significant only in one country, Azerbaijan, where those with two (or more) girls were less likely to choose an abortion than women with other sex combinations, signalling son preference. Other studies have shown family sex composition can affect abortion decisions (Edmeades et al., Reference Edmeades, Lee-Rife and Malhotra2010; Puri et al., Reference Puri, Adams, Ivey and Nachtigall2011; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Sánchez-Barricarte2016), but this study is different, as it shows whether women who experienced an unintended pregnancy choose an abortion depending on the sex of their existing children.

Interestingly, unlike elsewhere, in the post-Soviet/communist countries (apart from Tajikistan), those who had already exceeded their desired family size were less likely to report an unintended pregnancy than those who were at their exact desired family size. In Albania and Tajikistan they were also less likely to report an abortion following an unintended pregnancy. This may be due to different reporting of unintended pregnancy compared with the other contexts, as explained below.

In post-Soviet contexts, women reported more abortions and fewer unintended births than in the other contexts. These states traditionally had difficult access to modern contraception, but relatively easy and non-stigmatized access to abortion (Popov, Reference Popov1991; Popov et al., Reference Popov, Visser and Ketting1993; Agadjanian, Reference Agadjanian2002; Westoff et al., Reference Westoff, Sullivan, Newby and Themme2002). While reporting an abortion seems to be more liberal in these contexts than in the other countries of the study, reporting an existing child as unintended may be stigmatized, or perhaps in the context of liberal abortion legislation and lower abortion stigma, women simply carry fewer unintended pregnancies to term. In the post-communist context of Albania, abortion was only allowed under strict medical grounds until 1990, but it shares the difficult access to modern contraception with the post-Soviet states (Falkingham & Gjonça, Reference Falkingham and Gjonça2001; Gjonça et al., Reference Gjonça, Aassve and Mencarini2008), which may explain why it differs slightly from the other post-Soviet/communist countries in its abortion and unintended pregnancy reporting.

These results raise questions regarding what is measured when we ask women about their pregnancy intentions and desires. The ways women internalize and report their pregnancy intentions are complex and culturally specific (Kalamar & Hindin, Reference Kalamar and Hindin2015). Women may feel ambivalent about their pregnancy desires (Trussell et al., Reference Trussell, Vaughan and Stanford1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Barber and Gatny2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Tapales, Lindberg and Frost2015; Väisänen & Jones, Reference Väisänen and Jones2015) and the meaning of ‘fertility intention’ may differ by culture (Santelli et al., Reference Santelli, Rochat, Hatfield-Timajchy, Gilbert, Curtis and Cabral2003). The measure of desired family size might relate to the number of children a woman would like to have under ideal conditions in life, which might not match actual life circumstances. This mismatch has been found to explain the discrepancies between reported fertility intentions and fertility behaviour (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Wong and Miranda-Ribeiro2018). Therefore, the cultural–legal context in the conceptual framework (Figure 1) has important implications for perceptions and reporting of unintended pregnancy.

There were hardly any patterns to report that were unique to Latin America. This could be partly because most abortions were missed in the DHSs in Latin America due to severe under-reporting, or because only two countries in the region were included in this study. Similarly, in Asia there were no patterns that would have been specific to that region only, probably reflecting the cultural diversity of the countries and their abortion stigma.

One characteristic set the Latin American and Asian countries apart from the post-communist/Soviet contexts, though: in all countries of these two regions except the Philippines, women using more-effective contraceptive methods were more likely to report an unintended pregnancy than non-users. This was the case only in two post-Soviet countries (Armenia and Ukraine). It may be that the choice of contraceptive method is associated with the motivation to avoid pregnancy in these contexts (in line with Eggleston, Reference Eggleston1999, in Ecuador), whereas in others contraceptive method choice may not reflect the strength of motivation to avoid pregnancy (in line with Schünmann and Glasier, Reference Schünmann and Glasier2006, in Scotland). Another explanation could be different patterns of failure and discontinuation behind the use of the less- and more-effective methods, as well as the variation in that between the contexts. Method discontinuation could be related to lower motivation to avoid pregnancy (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Evens and Sambisa2011). If the episodes of the use of more-effective methods before pregnancy were more likely to end in discontinuation, as opposed to failure, that could explain the weaker association between the use of these methods and unintended pregnancy reporting. Thus, the results reported here support the mixed results of previous studies on the topic, and highlight a need for more investigations about the relationship between pregnancy intentions and contraceptive practices. Such investigations should take into account relevant cultural–legal elements, such as women’s knowledge about contraceptive methods, the state of the country’s health system and access to/quality of family planning care (see conceptual framework in Figure 1).

Implications

The study found that there was an increased likelihood of unintended pregnancy and abortion after a short birth interval. In Indonesia, Philippines and Bolivia, more than 50% of women had an unmet need for contraception in the postpartum period; in Nepal and Bangladesh this percentage was as high as 84% and 74%, respectively (Ross & Winfrey, Reference Ross and Winfrey2001). Given that postpartum family planning is important for birth spacing (World Health Organization, 2013), the findings of this study suggest women need more support in contraceptive use during the postpartum period. Better access to a wide choice of contraceptives among parous women could also reduce unintended pregnancies among those who have completed their desired family size.

The variation in the ‘determinants’ of unintended pregnancy resolution by cultural–legal context and stage of the process (experiencing an unintended pregnancy vs choosing an abortion) shows that no ‘one size fits all’ approach is likely to be effective when policymakers consider how to best to help women avoid unintended pregnancies. Any interventions should be tailored to fit the context and focus on reducing unintended pregnancy.

The results presented here also have implications for data collection. Due to data unavailability, no countries in Africa were studied here. While some African DHS calendars collect information about the timing of pregnancy terminations, they do not distinguish between abortions, miscarriages and stillbirths. Including this information would allow studying unintended pregnancy resolution in Africa, where its levels are known to be some of the highest in the world (Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Bearak, Singh, Bankole, Popinchalk and Ganatra2016).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the cross-country comparison element in various LMIC contexts. This is the first multi-country study to compare the determinants of unintended pregnancy (including both unintended births and abortions) and unintended pregnancy resolution in a range of LMICs discussing both the importance of wider contexts as well as individual-level characteristics.

The main limitation was the difficulty in measuring abortion and unintended pregnancy. As discussed in the Methods section, women tend to under-report abortions and prospective reports of pregnancy intentions might not match retrospective ones. Thus, the estimates presented here should not be viewed as true estimates of abortion but rather reflect the prevalence of reported abortions. Nevertheless, studying these phenomena is important with the data that are currently available. Future multi-country studies should focus on developing methods that better capture these under-reported events.

Differences in reporting unintended pregnancy and abortion indicate that culture and stigma impacted the results of this study. Thus, some of the results reported here may reflect variation across contexts in reporting of abortions/unintended pregnancies rather than differences in the propensity to experience these events. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the literature given the lack of international comparisons around this topic in LMICs.

There were some further limitations in the data. Since most variables were only measured at the time of the survey, it had to be assumed that, for instance, women’s level of education or marital status had not changed in between the outcome pregnancy and the survey interview. Similarly, the assumption was that the women had not changed their family size preferences as a result of their most recent pregnancy. While these assumptions meant that a minority of the women may have been misclassified into the wrong marital and education categories, it is unlikely the results of the study were fundamentally affected, as these were control variables and thus not the main focus here. Future longitudinal studies should examine the extent to which women change their reports of the desired number of children as a result of new pregnancies. Moreover, it was not possible to distinguish between pregnancies that resulted from contraceptive method failure or discontinuation among women who used contraception before pregnancy due to these data being lacking for some of the countries included in the analysis. Lastly, as mentioned above, unfortunately no DHSs in Africa had collected the information needed for this analysis.

Conclusions

Cultural–legal contexts and individual-level characteristics are associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and the subsequent decisions to keep or terminate a pregnancy. Contextual factors most clearly associated with unintended pregnancy resolution were type of abortion legislation and living in post-Soviet/communist contexts. The former probably affected the results partly due to severe under-reporting of abortion. The latter is a context where abortion stigma is traditionally low, so women’s experiences and reporting of both unintended pregnancies and abortions differed from the other contexts. Some individual-level characteristics had associations in the same direction with both the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and abortion, including short birth intervals and family size being smaller than desired. However, other characteristics operated differently depending on which stage of the process was examined. The number and sex composition of existing children were similarly associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancy across different contexts. Yet, family sex composition’s association with the likelihood of abortion varied across contexts. Similar patterns were observed for contraceptive use, which was differently associated with the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and abortion. This may be due to there being a difference between fertility and pregnancy management: while a woman may seek to avoid pregnancy by using a contraceptive method, the situation changes when an unintended pregnancy actually occurs. The decision to abort depends on the circumstances around that specific pregnancy (Coast et al., Reference Coast, Norris, Moore and Freeman2018) and may not agree with women’s pregnancy intentions prior to that pregnancy. This explains why it is important to study unintended pregnancy resolution as a process (Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007) – the characteristics associated with contraceptive use, reporting an unintended pregnancy and deciding to abort such pregnancy can be strikingly different.

More research on the topic is needed, ideally using longitudinal data. Innovative ways to measure abortion and unintended pregnancy would also be welcomed in any such data collection efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of Session 228: Fertility Intentions and Consequences in Population Association of America Annual Meeting 2019 and Dr Amos Channon for their helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Board of the University of Southampton. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.