On 6 June 1910, the satirical weekly Molla Nasraddin, published in Tbilisi, featured a captivating illustration on its cover: a figure with seven heads, labeled, clockwise from the left, as socialist, intellectual, pilgrim, nationalist, spy, and mullah (figure 1). The caption offered these as “seven professions” in Azerbaijani and “seven convictions” in Russian.Footnote 1 Seasoned readers of the magazine familiar with these recurring types would readily discern that the socialist, intellectual, and spy belonged to the Russian realm, the mullah and pilgrim to the Iranian realm, and the nationalist to the Ottoman realm. However, one figure remained unnamed despite being at the forefront, cloaking and carrying the rest. His attire and features suggested a typical man of the time from the South Caucasus. But why was he left unidentified, and what significance lay in his unnamed presence? What can this enigmatic figure and the incongruous bunch he supports tell us about the relationship between these typified characters and their convergence in the Caucasus?

Figure 1. Cover illustration, “Seven Occupations,” Molla Nasraddin, 6 June 1910. Illustrator: Oscar Schmerling. Image reproduced by Çınar-Çap Nəşriyyatı (vol. 3, 2005).

In the pages of Molla Nasraddin, this deliberate anonymity becomes an expression of a remarkable capacity forged at the convergence of empires: to move fluidly between different imperial affiliations while maintaining a perspective that belonged wholly to none of them.

While critical studies of empire have powerfully demonstrated how imperial power shapes local life, from technologies of rule (Go Reference Go2023; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2002; Stoler Reference Stoler2010) to cultural categories (Cohn Reference Cohn1996; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1988; Said Reference Said1978) and patterns of inequality (Elkin Reference Elkin2022; Mbembe Reference Mbembe2001; Tlostanova and Mignolo Reference Tlostanova and Mignolo2012), these dynamics are typically examined through the lens of a single empire. In the Caucasus, where imperial control has repeatedly shifted hands since antiquity and multiple empires simultaneously vied for influence, locals navigated a palimpsest of imperial worlds and legacies rather than confronting a single colonial power. Through its vibrant mix of cartoons, character types, and multilingual satire, Molla Nasraddin showcases the creative engagements with a sophisticated cultural repertoire built up over centuries of imperial encounters, inviting us to reckon with local-imperial relations that cannot be captured by conventional binary oppositions—center versus periphery in spatial terms, indigenous versus foreign in cultural terms, and resistance versus accommodation in political terms.

The magazine emerged from a rich heritage of cultural synthesis in the Caucasus—a tradition exemplified by nineteenth-century Muslim intellectuals like Abbasgulu Bakikhanov, Gasim bey Zakir, and Mirza Fatali Akhundov. Drawing on Turkic and Persian traditions while engaging with modern reformist thought from the Russian Empire, these writers developed distinctive eclectic perspectives that resonated across generations in both Turkish and Iranian intellectual life.Footnote 2 Heir to this synthetic tradition, Cəlil Məmmədquluzadə, an Azerbaijani teacher-turned-journalist, launched Molla Nasraddin from a renovated print house in Tbilisi in March 1906.Footnote 3 The timing was crucial—shortly after the Russian constitutional revolution of 1905 and just before similar revolutions took place in Iran in 1906 and the Ottoman Empire in 1908. Working with a dedicated team of writers and illustrators, he created what soon became the most influential Muslim periodical of its era, reaching approximately twenty-five thousand readers across the Caucasus, Iran, Muslim regions of Russia, and the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 4

The magazine achieved this remarkable reach through its masterful synthesis of diverse influences, beginning with its namesake Nasraddin, the medieval wise fool whose stories circulated from the Balkans to Central Asia. Its satirical style borrowed from Russian writer Nikolai Gogol’s blend of realism and absurdity (Feldman Reference Feldman2018), while notable contributors like poet Ələkbər Sabir drew inspiration from Persian classics (Siegel Reference Siegel and Unbehaun2004). This engagement with both classical and modern forms manifested across a range of genres—poetry, travelogues, humorous telegrams, essays, fake news, and tongue-in-cheek open letters. Satire functioned as the magazine’s primary mode of critique, unifying diverse literary forms: telegrams mixed real and fake news to expose absurdities across imperial boundaries; poems deployed traditional forms for contemporary critique; and travelogues enabled sustained commentary through the eyes of a supposedly naïve observer. Completing the magazine’s creative arsenal were vivid cartoons from German-Georgian artist Oskar Schmerling and his colleagues Josef Rotter and Əzim Əzimzadə, who drew from a wide range of European and Russian artistic influences (Afary and Afary Reference Afary and Afary2022).

Though primarily written in the Turkic vernacular spoken by Muslims in the South Caucasus, the magazine regularly featured fragments or entire texts in Persian, Ottoman Turkish, and Russian, often without translation. Despite advocating for “plain Turkish” in submissions, the editors maintained this multilingual approach, recognizing their readership’s facility with these languages. This linguistic dexterity was further showcased through a recurring section featuring poems that alternated between Turkish and Persian couplets.

Through these varied influences and editorial choices, Molla Nasraddin crafted a distinctive voice couched in a Turkic vernacular, infused with the style of modern Russian satire, all while grounded in the culturally rich material of Persian classics.Footnote 5 Attending to this voice opens a rare perspective on the Caucasus, one that elevates it from an imperial periphery to an inter-imperial center in its own right, offering a panoramic view of all three empires during their near-simultaneous transformations. While historical studies have examined the interconnections between these revolutions (Atabaki Reference Atabaki2008; Atamaz Reference Atamaz2021; Berberian Reference Berberian2019; Clark Reference Clark2006; Deutschmann Reference Deutschmann2013; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2011; Sohrabi Reference Sohrabi2002; Reference Sohrabi2011; Yaşar Reference Yaşar2014; Zarinebaf Reference Zarinebaf2008; Zürcher Reference Zürcher2019), Molla Nasraddin offers something more vivid and immediate—a perspective on these revolutionary movements that emerges not through historical reconstruction but through contemporary literary imagination and aesthetic expression. The magazine’s rich textual and visual compositions, circulating among a readership dispersed across empires, held together a public that never found a representation as a whole in the historical record. While archival sources offer only partial views of it, this inter-imperial public otherwise hidden in plain sight comes fully into view in the magazine’s pages through a distinctive blend of visual satire, literary innovation, and multilingual discourse.

What distinguished this public was its capacity to inhabit multiple imperial worlds simultaneously, translating between them while maintaining critical distance from each. In this study, I conceptualize this shared capacity as inter-imperial literacy Footnote 6 and ground it in the magazine’s unique cultural positioning: while deeply engaged with Slavic and Orthodox cultures, it remained firmly grounded in Muslim sensibilities and moral codes shaped by centuries of engagement with Turkic and Iranian traditions. Week after week, the magazine cultivated this literacy through a form of satirical pedagogy, deploying recurring characters, costumes, and juxtapositions that taught readers how to think across imperial boundaries and reflect on their connections and contradictions. Bringing Molla Nasraddin’s expansive geography of circulation into conversation with its visual and textual forms illuminates a public that transformed apparent peripheral distance into a unique vantage for interrogating the puzzles and possibilities of a new era.

Returning to the magazine’s cover, the seven-headed figure visually embodies this literacy through its unnamed central character who carries multiple imperial types while remaining distinct from them all. This positioning—at the crossing point where Iranian, Turkish, and Russian influences converged upon and were carried by local bodies—enabled both engagement with and detachment from multiple imperial worlds. Taking this comical aberration as a serious invitation, I delve deeper into Molla Nasraddin’s material in the following pages to show how empire-spanning borderlands can transform into wellsprings of creative engagement, offering platforms for resilience and renewal amid revolutionary changes.

Grasping these creative possibilities demands an analytic language attuned to catch the resonance between textual creation, revolutionary moments, and public formation. I first develop such an analytic to highlight the magazine’s singular position as a voice that could observe and critique overlapping empires without being constrained by conventional center-periphery dynamics. The empirical analysis then unfolds in three parts. First, I examine the magazine’s satirical pedagogy that taught readers how to think with multiple empires and recognize their parallels, connections, and disjunctions. I then trace how this literacy evolved through the magazine’s intertextual dialogue with mobile activists and writers whose revolutionary trajectories intersected in the Caucasus. Third, I analyze how the magazine’s engagement with cultural difference revealed the protean nature of locals moving between personhoods and possibilities amid revolutionary transformations. The analysis concludes by situating Molla Nasraddin within a broader pan-Caucasian perspective shared by parallel Armenian and Georgian publications, before its eclipse by the emergence of nation-states. Tracing this trajectory challenges us to reimagine what we consider center and periphery in the heart of Eurasia.

Reading between Imperial Lines: The Making of a Revolutionary Public

Michael Warner (Reference Warner2002) contends that texts—whether oral, visual, or audiovisual—do not circulate within preexisting publics; rather, they summon them by addressing strangers, capturing their attention, and conditioning their own circulation. The characteristics of any public—such as its scope, duration, and influence—are thus deeply intertwined with the generic qualities and discursive potential of the texts that summon them.Footnote 7 Through its sophisticated deployment of recurring character types and visual juxtapositions, Molla Nasraddin summoned a public whose coherence rested precisely on their shared ability to decode and critically engage with the ironic parallels and disjunctures that such juxtapositions produced.

Revolutions, similarly, have the capacity to summon publics by interpolating any stranger who pays attention to the revolutionary event.Footnote 8 These strangers might be incorporated into the ideal society envisioned by the revolution, become its critics and defectors, or serve as spectators whose undecided gaze is ever critical to keeping the revolutionary fervor alive. This co-constitutive relationship between a revolution and its public is especially salient in constitutionalist revolutions, where the idea of the public acquires moral weight vis-à-vis the excesses of monarchical power. In the case of Molla Nasraddin, a publication circulating amidst three constitutional revolutions, we are presented with a rare opportunity to explore the qualities of a public engaging with all three monarchies simultaneously.

The concurrent rise of constitutionalist movements across three empires was not merely a backdrop for Molla Nasraddin’s emergence—it fundamentally shaped the magazine’s expressive possibilities by destabilizing conventional binaries. The relation between sovereign and subordinate was subjected to scrutiny as constitutional movements challenged absolute monarchies. The spatial logic of center and periphery was unsettled as revolutionary movements gained momentum in borderland regions like the Caucasus or the Balkans before reaching imperial capitals. As activists and ideas flowed across imperial boundaries, the magazine’s pages became a space where categories and personhoods could be playfully recombined—where resistance might look like accommodation, and accommodation might mask resistance. While other publications might have struggled to capture the rapid political transformations and emerging possibilities through conventional formats, Molla Nasraddin’s eclectic universe moving between different genres and imperial worlds was uniquely suited to represent a transregional landscape where traditional orders were being radically questioned and reimagined.

The magazine’s position at this critical juncture—not just spatially between empires but stylistically between genres—resonates with Isabel Hofmeyr’s (Reference Hofmeyr2015) conceptualization of Indian Ocean cultural forms as operating across “high,” “low,” and “in-between” registers. Molla Nasraddin navigated between seemingly contradictory modes: it combined the gravitas of high literary critique with the accessibility of popular satire. While its sophisticated analysis of imperial interconnections and constitutional revolutions aligned with the “high” tradition of noble epic and political consciousness, its deployment of visual humor, multilingual wordplay, and irreverent character types drew from the “low” tradition of slapstick comedy and popular culture. Yet Molla Nasraddin was most at home in what Hofmeyr terms the “in-between” space, a position that allowed it to “relativise romantic accounts” while tracing the “frictions and faultlines” between imperial projects (ibid.: 99).Footnote 9 Working at the jagged edges between imperial traditions, the magazine used satire to illuminate both the possibilities and tensions of cultural transformation across imperial boundaries.

Dustin Griffin describes satirical irony as more than a mere binary switch; he likens it to a rheostat, “a rhetorical dimmer switch that allows for a continuous range of effects between ‘I almost mean what I say’ and ‘I mean the opposite of what I say’” (Reference Griffin1994: 65–66). The expressive range afforded by this rhetorical dimmer switch gave Molla Nasraddin its distinctive power to move between earnest critique and playful subversion. While satirical irony and humor broadly thrive on exposing incongruities and overturning common sense, this exposure relies on an audience capable of recognizing it as such, thereby evoking a shared basis—a sensus communis (Critchley Reference Critchley2002: 79–90). In other words, while the satirical form creates discordance, its performance—in the case of Molla Nasraddin, its circulation—restores a sense of unity, even community. What kind of community emerged from sharing laughter with Molla Nasraddin over its own incongruities?

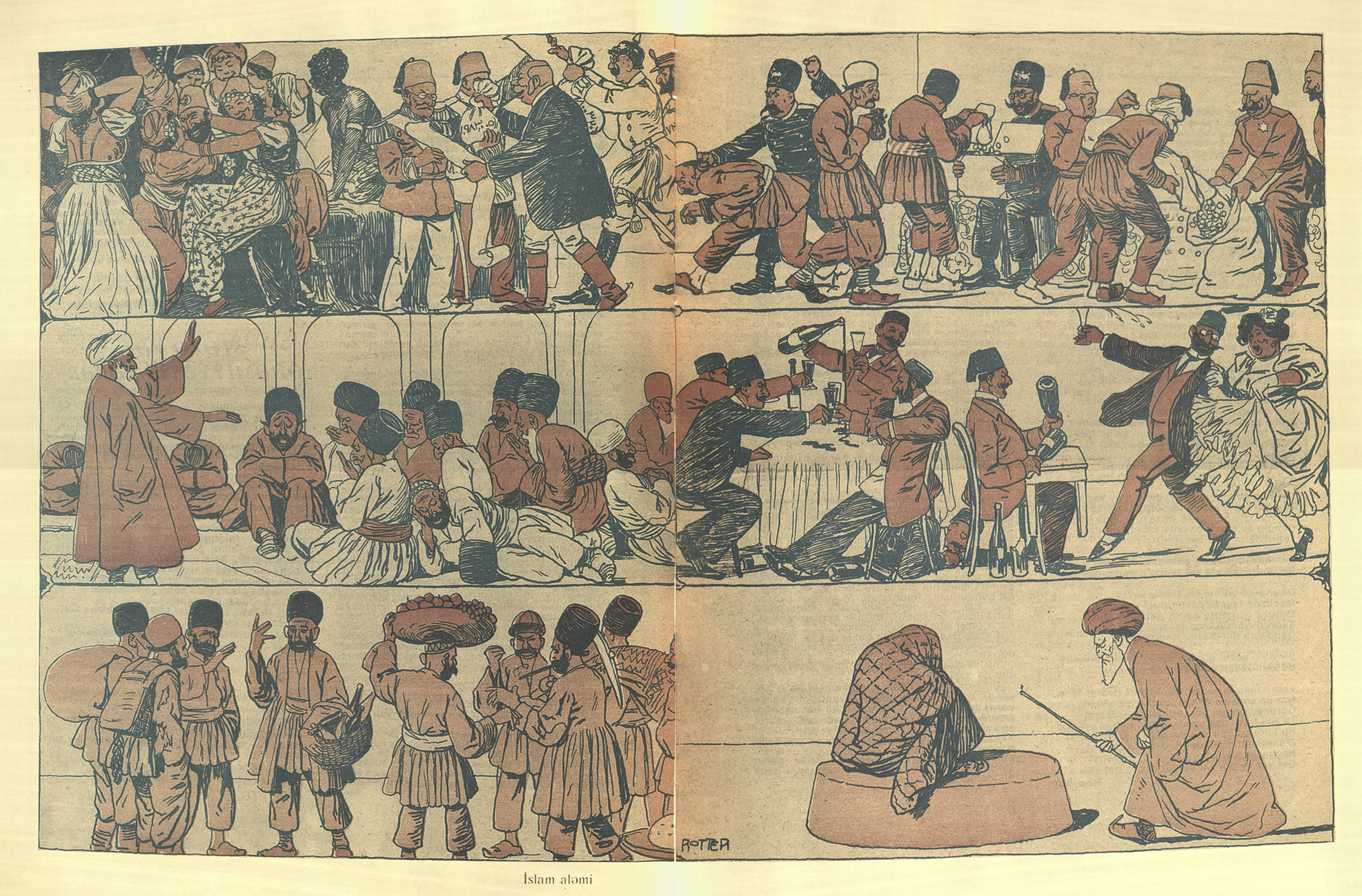

In addresses to readers, the magazine frequently used the phrase “we Muslims.” To the best of my reading, this identification rarely signified the ummah, the universal Muslim community. Instead, it referred to a public that, while broadly spanning various empires, was specifically united by a Turkic vernacular, which the magazine referred to as Musəlmanca, or “the Muslim language.” This readership, concentrated in the Caucasus and extending across empires, did not fall under a single name. In the historical record, we find them variously identified as Azerbaijanis, Azeris, Russian Muslims, Iranian Turks, Tatars, Persians, and Turks, among others.Footnote 10 In the eclectic material of Molla Nasraddin, these various designations converge into a nomenclature of an inter-imperial public, revealing a Caucasus intricately entwined with the surrounding empires (figure 2).

Figure 2. Cartoon, “Muslim World,” Molla Nasraddin, 24 November 1906. Illustrator: Josef Rotter. Image reproduced by Azərnəşr (vol. 1, 1996). The settings, characters, and costumes reveal a Muslim world through a distinctly Caucasian lens—a perspective that is both expansive (spanning the Russian, Ottoman, and Iranian domains) and distinctly selective in its omission of Muslims from British India, the Dutch Indies, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa.

This expansive Caucasus has been coming into sharper relief with more scholars unearthing its transregional cultural orbit through literary texts (Feldman Reference Feldman2018; Gould Reference Gould2015; Reference Gould2016), mobile activists (Berberian Reference Berberian2019; Shissler Reference Shissler2002), historical practices (Grant Reference Grant2009; Yolaçan Reference Yolaçan2025), and artistic production (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2023; Rice Reference Rice2021). Drawing on this body of work, my analysis of the magazine moves beyond regional clamps that have confined its study to specific national contexts. More importantly, I unsettle the lopsided emphasis on the magazine’s “progressive” role as a reformist and anti-colonial enterprise, which has dominated much of its scholarship.Footnote 11 Rather than viewing Molla Nasraddin as either a proto-nationalist project or a modernizing force, I argue that its significance lies in how it captured and cultivated a complex inter-imperial terrain through satire.

This approach requires seeing texts, following Karin Barber, not as windows onto social reality, but as constituting—through their forms, circulation, and mutations—the very social terrain that demands empirical study (2007: 9). Barber defines text through “the idea of weaving or fabricating—connectedness, the quality of having been put together, of having been made by human ingenuity” (ibid.: 21). This perspective places written words and visual images on the same analytic plane, allowing us to read Molla Nasraddin’s visual and textual elements as part of the same fabric. If genres are forms of weaving that invite specific kinds of attention, then Molla Nasraddin cultivated such attentiveness through a distinctive visual-textual vocabulary that playfully reworked relationships between cultural personhoods and imperial affinities.

This vocabulary took shape through the magazine’s sustained correspondence with its readership, whose letters and submissions brought local accounts into conversation with broader imperial narratives, connecting subjects of different empires in an ongoing dialogue over shared concerns. From this satirically reflexive dialogue emerged a kind of auto-ethnography of an inter-imperial public, documenting how people across these imperial boundaries made sense of their entangled worlds amidst profound political transformations.

This auto-ethnographic practice met the magazine’s satirical pedagogy in the figure of Nasraddin himself, who regularly appeared on the cover as the master of ceremonies, inviting the readers to the theater of social critique and humor within its pages. A wise fool found in folkloric traditions across Anatolia, Iran, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, Nasraddin embodies both clever trickster and naïve simpleton—a character whose predicaments could variously illuminate the human condition, convey moral lessons, or challenge conventional wisdom.Footnote 12 His reach extends beyond Muslim contexts, appearing in Greek (Fedai Reference Fedai and Birgül2021) and Armenian (Vartanian Reference Vartanian1943) folklore, and even reaching China through the TV animation series The Tales of Afanti (1979–1980), where his character acquired a communist inflection.Footnote 13 His name itself, derived from the Arabic Nasir al-Din (نصير الدين, meaning defender of the faith), demonstrates this adaptive quality, taking on regional variations: Uzbeks know him as “Khoja Nasreddin,” Uyghurs as “Nesirdin Ependi,” Turks as “Nasrettin Hoca,” and Iranians as “Molla Nasraddin.”Footnote 14 As both a cultural touchstone and an adaptive character, Nasraddin exemplifies the kind of fluidity required to move between imperial worlds while remaining locally grounded in diverse contexts.

The magazine often mobilized Nasraddin’s protean character to visualize the multiplicity within its own public. In the opening cover illustration, he stands in the background in his distinctive red robe and leaning on a cane, mirroring the unnamed figure in the foreground. Through this mirroring, the magazine suggests that a “typical” Muslim man from the South Caucasus contains within himself the same capacity for multiplicity embodied by Nasraddin. The local and transregional converge in this reflection. As the unnamed figure takes on characteristics of recognizable types from neighboring empires, we begin to see how the Caucasus itself becomes Nasraddin territory—a space where multiple imperial affiliations converge, manifesting as different cultural personhoods sometimes housed within the same body. Like its namesake who taught wisdom through wit, the magazine transformed this capacity for multiplicity to cultivate a new kind of literacy among its readers.

Satirist’s Types: Monarchs, Mullahs, and Making Empire Legible

Revolutionary discourse and satire share a fundamental pedagogical strategy: both teach through the deliberate deployment of social types. As Caroline Humphrey (Reference Humphrey2008) observes, transformative societal moments crystallize personalities that persist as historical markers of these upheavals. In revolutionary discourse, these crystallized personalities are simplified and exaggerated into types that exploit, oppress, suffer, resist, outwit, or protect each other. This dramatization of power relations serves to call for action—whether to overthrow, liberate, enlighten, unite, or eliminate these types. Similarly, satire relies on familiar types as its raw material but transforms them through humorous misplacement or subversion. The effectiveness of both revolutionary and satirical discourse hinges on their audience’s ability to think with types—to recognize these simplified characters as embodiments of social forces and relationships that can be transformed.

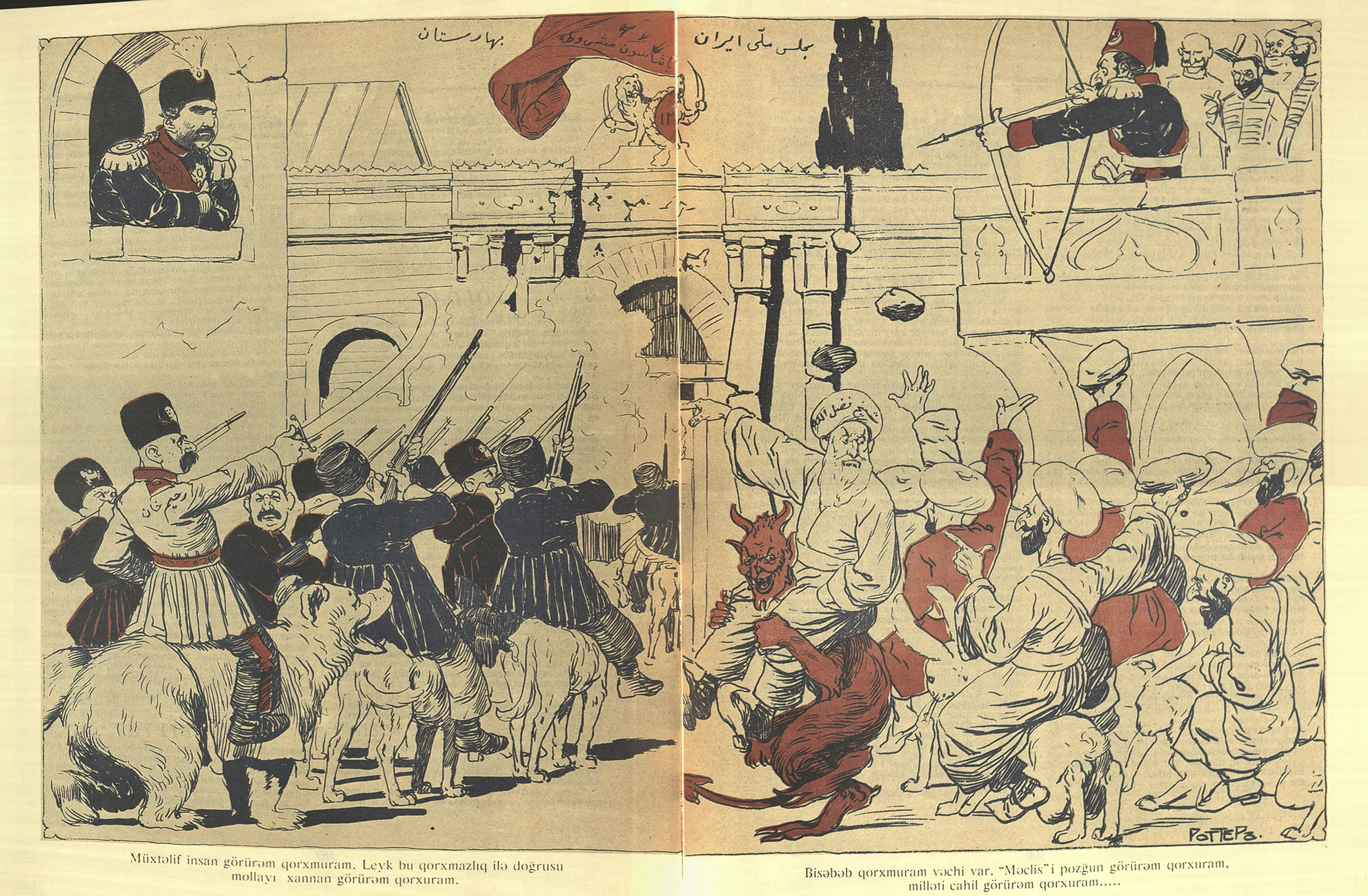

In Molla Nasraddin’s universe, we encounter character types that operate at what Engseng Ho calls the intermediate scale—the expansive domain of adjacent regions forged through historical patterns of circulation and exchange, one that exceeds localist and nationalist frameworks while resisting dissolution into the abstractions of globalism (Reference Ho2017: 922). This is vividly demonstrated in a cartoon from 17 September 1907, which presents a chaotic scene where monarchs, mercenaries, and mullahs are attacking the Iranian parliament (figure 3). On the right, mullahs are riding giant hares, led by the influential cleric Sheikh Fazlullah—a constitutional ally turned enemy—carried on the devil’s shoulders. On the left, a paramilitary brigade, led by their tribal chief Rahim Khan, a henchman of the Iranian Shah Mohammad Ali, are firing their rifles. The Shah, eager to dismantle the parliament and reclaim absolute power, is watching from the top left corner. Opposite him, Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II, faced with similar challenges in his empire, is drawing an arrow at the Iranian parliament under the watchful eyes of European monarchs. The Russian Tsar, absent from the scene (likely to avoid censorship), is allegorized as a bear carrying Rahim Khan, exposing tsarist support for royalist forces in Iran. Captured in a single frame is an international coalition of monarchs, mullahs, and mercenaries intent on undoing Iran’s constitutional revolution.

Figure 3. Cartoon, “Iranian Parliament, The Abode of Spring,” Molla Nasraddin, 17 September 1907. Illustrator: Josef Rotter. Image reproduced by Azərnəşr (vol. 1, 1996).

While these caricatured figures represent real historical personalities, they also embody broader types. Mullahs, frequently targeted by the magazine, appear as corrupt, parasitic figures whose entrenched influence over the populace hinders social and political progress. Monarchs resisting constitutional limitations are portrayed as outdated and in need of reform. Tribal chiefs, though less frequently depicted, represent loyalties that should be obsolete but are instead harnessed by monarchs for their dirty work in exchange for special privileges. These types are not just antiquated but insidious: mullahs claim to serve Allah while working for the devil, and tribal mercenaries who fight for the shah are in collusion with the tsar.

Through these typified portrayals of historical figures from neighboring territories, Molla Nasraddin highlighted the interdependence of imperial domains. This interdependence was evident to those at the top—the monarchs—who had much to lose amidst the political turmoil in their realms. A perspective of matching breadth, but from below, was available to the readers of Molla Nasraddin. The ambitious scope of this bottom-up view was showcased by the magazine’s “telegrams” column which blended actual news and satirical dispatches on a weekly basis. In the magazine’s inaugural issue, the purported locations of the first three telegrams were as follows:

-

Petersburg, 30 March: All of Russia is peaceful. The wolf and the lamb are grazing together.

-

Tehran, 30 March: His Majesty the Shah is preparing for a journey to Europe.

-

Istanbul, 29 March: The Ottoman government has prohibited coughing on the streets.

In a reversal of the typical dynamic, these telegrams originating from various imperial capitals reached the Caucasus, much like a newspaper transmitting news from distant colonies to an imperial metropole. This was not a case of superficial reach masking provincial limitations, as in the French saying about culture being like jam: spread ever thinner when scarce. The vast space between these three capitals was thickened through weekly letters streaming into Molla Nasraddin’s editorial room—from Tabriz to Kazan, Odessa to Ashgabat, and many cities throughout the Caucasus—and the magazine’s editorial responses to these letters. Through this two-way traffic emerged not only telegraphic observations but also vivid ethnographic portrayals of everyday life, popular trends, subterranean social tensions, and economic disparities across these territories.Footnote 15

The magazine’s telegraphic dispatches reflected the telegraph’s growing significance as a revolutionary communication technology at the time. The encoding-decoding process fundamental to telegraphy paralleled the interpretive mechanics of printed cartoons, with each medium demanding its own form of literacy: telegraph operators transformed speech into electrical signals for decoding at distant stations, while cartoonists distilled complex political realities into visual archetypes that required readers’ political sophistication to interpret.Footnote 16 These interwoven networks of communication accustomed readers to movements between local and imperial scales. In the pages of Molla Nasraddin, local grievances about Tbilisi mullahs appeared alongside constitutional developments in Tehran, while a merchant’s struggles in Baku illuminated broader patterns of economic transformation across the Russian Empire. By revealing unexpected connections between the more immediate experiences and the broader imperial changes on a weekly basis, the magazine cultivated a particular kind of literacy among its readers that could connect and compare the three imperial worlds.

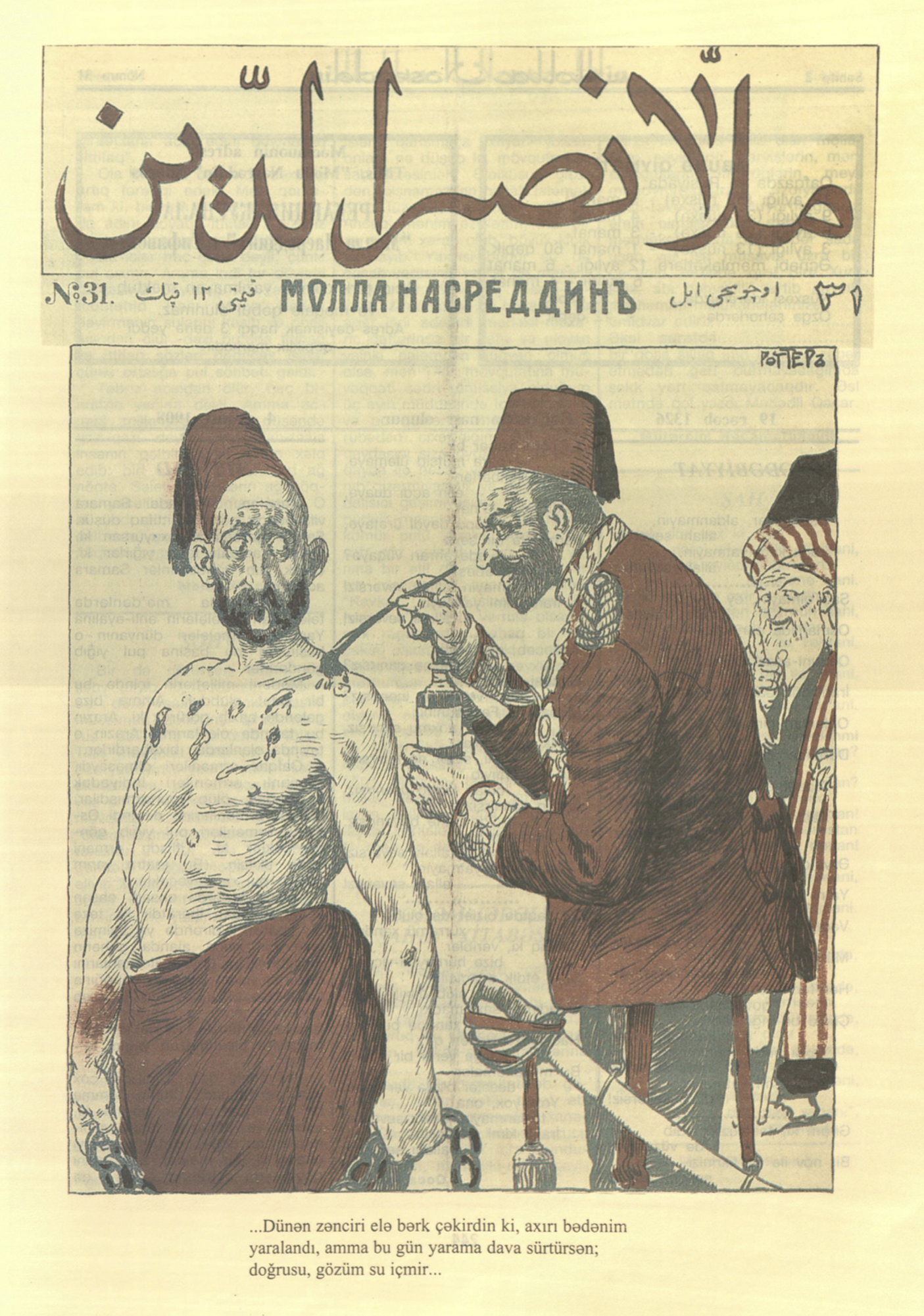

Opening virtually any volume of Molla Nasraddin reveals the cultivation of this inter-imperial literacy in action. The 4 August 1908 edition offers one such view, featuring on its cover a poignant caricature of Sultan Abdulhamid II tending to the wounds of an Ottoman citizen (figure 4). The citizen, having endured decades of authoritarian rule, is astonished by this sudden display of care and remarks, “Yesterday, you were wielding the chain so hard that it left wounds on my body, and now you are applying medicine to them. Frankly, I am doubtful.” The scene captures the sultan’s abrupt change in attitude as a strategic move to remain on the throne following the constitutional revolution led by the Young Turks in July of that year.Footnote 17

Figure 4. Cover illustration, (no title), Molla Nasraddin, 4 August 1908. Illustrator: Josef Rotter. Image reproduced by Azərnəşr (vol. 2, 2002).

Turning the page, we encounter a poem addressed to Ottoman subjects, urging them not to be swayed by the apparent success of the Young Turk Revolution. Drawing parallels to the Iranian experience, it advocates for unwavering commitment to constitutionalist ideals while emphasizing the importance of unity. Another section, titled “Peterburq,” details the tyrannical measures taken by Iranian Shah Mohammad Ali and executed by Cossacks and Amir Badirhan. The passage highlights the distorted perception of Iranian affairs in St. Petersburg, where Mohammad Ali Shah is unequivocally admired. This distortion is attributed to the manipulation of telegrams sent from Tehran, where the telegraph is said to be controlled by the Shah, the Cossacks, and Amir Bahadir.

Next is a feuilleton titled “Mr. Mozalan’s Travelogue.” Within this segment, Mozalan—slang for “joker”—guides us through the streets of Mashhad in search of a telegraph station. Along the way, he observes the Iranian branches of various Russian companies and banks, lamenting how they extract the lifeblood of Iran. In an alley, he stumbles upon rare rifles from the era of Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747), their stocks now stained crimson black. These rifles poignantly remind Mozalan of Iran’s past military prowess, a stark contrast to the country’s current state, reflected in the disorganized telegraph office where Mozalan watches an officer struggling to find paper for his telegram.

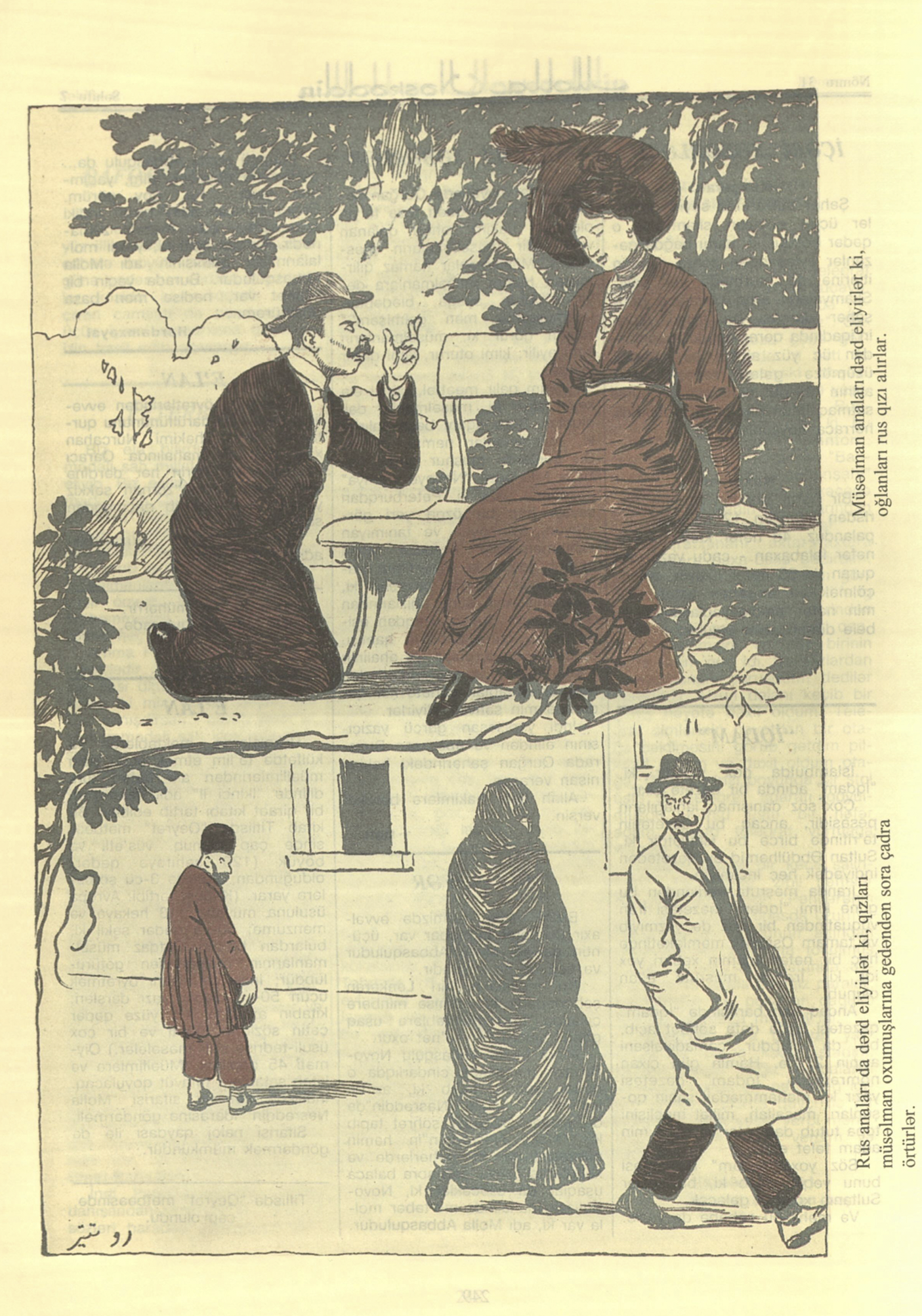

Another section, “Delightful News,” reports from Qurgan in Bukhara, where a newly appointed judge from Saint Petersburg strolls around a local mosque during prayer time. “Stand up, infidels. Can’t you see I have arrived?” the judge exclaims, only to be confused by the reactions of Muslims variously standing, sitting, and bowing—they were, in fact, simply continuing their prayers. The judge’s ignorance of Muslim practices is highlighted to support the Georgian writer Niko Nikoladze’s commentary in the Russian newspaper Novoye Vremya, which criticized officials appointed from Saint Petersburg to govern the Caucasus as being utterly ignorant of local customs. The issue concludes with a caricature humorously juxtaposing the concerns of Muslim mothers, worried about their sons marrying Russian women, with the anxieties of Russian mothers fearing their daughters might adopt veiling after marrying a Muslim man (figure 5).

Figure 5. Cartoon, (no title), Molla Nasraddin, 4 August 1908. Illustrator: Josef Rotter. Image reproduced by Azərnəşr (vol. 2, 2002).

From just a glimpse into a single issue of Molla Nasraddin, we witness Iran’s dire economy and failing infrastructure through a stroll in Mashhad while learning about its contrasting perceptions in the Russian capital. The challenges faced by Ottoman constitutionalists are highlighted in light of the Iranian experience, accompanied by critiques of the Russian imperial administration’s short-sighted decisions in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Additionally, we uncover parallel concerns among Muslim and Russian mothers, each worrying about their children’s marriage prospects. Such expansive coverage relied on readers who could recognize and interpret complex political references across imperial boundaries. When the magazine depicted such scenes—whether Sultan Abdulhamid II tending to the wounds of his subject or the Russian Tsar as a bear supporting royalist forces in Iran—it assumed an audience capable of decoding both the immediate political commentary and its broader implications.

In cultivating this sophisticated readership through its multilayered content—from cartoons and telegrams to poetry and local reportage—the magazine revealed how the three imperial centers that appeared distinct and oppositional from their centers were in fact deeply entangled, their policies and problems mirroring each other in ways that only became apparent from a Caucasus-centered vantage point. Week after week, this kaleidoscopic view circulated across imperial boundaries, with each issue bringing together stories gathered along its routes—from activities of Christian missionaries among the Tatars in Kazan (10 November 1908) to rapid urbanization in Ashqabat (30 June 1908), unsanitary conditions in public baths in Mashhad (28 July 1908) to mistreatment of Muslim pilgrims in Odessa (17 November 1908).

The revolutionary transformations were not merely a backdrop to these observations—rather, it was these very observations, circulating through texts and activist networks between neighboring empires, that equipped imperial publics with new frameworks for understanding their conditions and catalyzed collective action. As revolutionary movements encouraged people to situate local problems within broader imperial frames, those in the Caucasus who could navigate multiple imperial contexts were uniquely positioned to influence various imperial publics by cross-pollinating ideas. The inter-imperial literacy cultivated by Molla Nasraddin transcends a mere response to revolutionary conditions—it helps explain how revolutionary ideas gained unstoppable momentum across imperial boundaries. The local-imperial entanglements revealed in the magazine must therefore be examined alongside the textual output of activists who moved between imperial centers via the Caucasus, transforming this historical borderland into a backroom where empires were reshaped through mutual influence.

Backroom of Empires: Revolutionary Passages, Intertextual Dialogues

The revolution that swept through Russia in 1905 opened new avenues for political representation among the empire’s diverse populations, including Muslims in the Caucasus. They found a voice in the newly established State Duma through their Russian-educated leaders, who, alongside Muslim activists from the Volga, Crimea, and Central Asia, formed the liberal-constitutionalist Ittifaq al-Muslimin (The Union of the Muslims of Russia). Molla Nasraddin closely observed this development, adopting a cautiously optimistic stance toward the efforts to secure a dignified status for Russia’s Muslims within the empire.

While the high politics of the Duma were accessible to only a select few, the burgeoning press provided a broader platform for educated Muslims from the Caucasus to engage in debates about the empire’s future and their place within it. During this period, over sixty newspapers and journals were published in Azerbaijani Turkish (Altstadt Reference Altstadt1992: 207), with Molla Nasraddin emerging as arguably the most popular among them. Together, the Duma and the vibrant publishing industry offered an intellectual and political arena for this Muslim public to reassess their status within the empire and explore alternative pathways. Reading rooms proliferated throughout the region, providing physical spaces for the cultivation of an engaged reading public (Rice Reference Rice2024).

Discussions in these various platforms were enriched by the experiences and proposals of a broader network of activists—agitators, journalists, novelists, parliamentarians, and exiles—who participated in revolutionary movements not only in Russia but also in the neighboring domains of Iran and the Ottoman Empire. As these activists traversed borders, their ideas found fertile ground in the Caucasus, where they collided with local debates, sparked new conversations, and evolved in unexpected directions. Thanks to this heightened traffic, the region became a laboratory of sorts where reformist and revolutionary visions from three empires were constantly tested, transformed, and rewoven into new possibilities.

One such influential text that captured Molla Nasraddin’s interest was a fictional travelogue titled Siyahatname-i Ebrahim Beg (Travelogue of Mr. Ebrahim). Published in Persian across three volumes between 1895 and 1900, the travelogue found eager audiences among both Iranian reformists and dissident networks of Iranian Azerbaijani merchants trading in the Russian Caucasus and Ottoman Anatolia.Footnote 18 The travelogue offered a scathing critique of Iranian affairs, but its appeal was also bolstered by its rich ethnographic narrative that drew on the experiences of its merchant-turned-author, Zeyn al-Abedin Maraghei (1839–1910).

Maraghei began his career in Tabriz as the son of an affluent Iranian trader. When his business ventures in Iran faltered, he resettled in Tbilisi, where his reputation for charitable works earned him appointment as Iran’s deputy consul general. Financial setbacks later drove him to Crimea, where he and his brother adopted Russian subjecthood and traded textiles from Istanbul in Yalta, a retreat favored by Russian aristocracy. After moving to Istanbul, Maraghei drew on the support of Iranian Azerbaijanis at the embassy to reclaim his Iranian subjecthood and soon began contributing to the Persian-language weeklies Akhtar and Shams, both published in Istanbul by diasporic Tabriz intellectuals. During this period, he undertook the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, an experience that inspired his fictional travelogue chronicling his journey backward from Egypt to Iran, by way of Istanbul and Tbilisi.Footnote 19

The cross-border movements in the itineraries of both Maraghei and his fictional character Ebrahim transcended simple unidirectional journeys between homeland and host country. Instead, they followed circular routes crowded with activists who shifted between occupations, citizenships, and worldviews as they moved. Molla Nasraddin’s own circulation paralleled these transimperial routes. In fact, directly inspired by Maraghei’s Siyahatname-i Ebrahim Beg, the magazine created its own traveling observer in Mozalan, whose itinerary was announced on 9 March 1908, as follows:

We inform our readers that our companion, Mr. Mozalan, will soon embark on a journey from Tbilisi to Ganja, and after exploring the city of Ganja, he will proceed to the Erivan Governorate. There, he will visit its cities and continue through Kars toward Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe, making his way to Batumi. From Batumi, he will tour the northern regions, meet with the Russian Tatars, and return to Baku. From Baku, he will head to Khorasan, Tehran, and, via Tabriz and the Jolfa route, will return to Tbilisi.

Beginning in the Russian Empire’s administrative center in the Caucasus, this ambitious itinerary winds through Muslim-majority cities under Russian rule, territories newly acquired from the Ottomans, and the Black Sea region, before crossing into Iran through Central Asia and finally returning to the Caucasus through the border crossing at Jolfa. Yet characteristically for Molla Nasraddin, this grand tour is introduced with satirical irony—before embarking, we learn, Mozalan must first obtain “a fake certificate of nobility for himself” through “various tricks, schemes, and cunning,” highlighting how such mobility often required creative navigation of imperial bureaucracies.

Like a continuous tracking shot, Mozalan’s travelogue moves seamlessly between intimate local scenes and broader imperial vistas. In Ashgabat, one of his stops in Central Asia en route to Iran, Mozalan notes the city’s transformation “from a wild desert twenty-five years ago” into “a respected city adorned with flowing waters, wide boulevards, gardens, grand buildings, hotels, twenty bathhouses and two clubs, schools and gymnasiums.” Yet in the same city, he encounters a preacher categorizing animals as Sunni and Shi‘i, reducing the vast sectarian divides that shaped imperial politics to an absurdist taxonomy. Crossing into Iran, Mozalan depicts the failing infrastructure of a once powerful empire. And back in the Russian Caucasus, one of his dispatches unveil unexpected connections between Ordubad’s local elections, rising rice prices in Sharur, and the inflow of Iranian eulogy reciters to Ordubad from across the Aras River.

While Molla Nasraddin welcomed some texts as creative kindred, others became objects of pointed critique. Chief among its targets were the more sober Baku journals Hayat and its successor Fiyuzat, both funded by oil magnate Zeynalabdin Tağıyev in Baku and edited by Əli bəy Hüseynzadə, an intellectual activist with strong ties to Istanbul. These rival publications promoted a vision of Muslim unity centered on Ottoman cultural forms. Hüseynzadə, in particular, vigorously advocated for the adoption of Ottoman Turkish as the common vernacular for all Turkic-speaking Muslim subjects of the Russian Empire, sparking fierce rebuttals from Molla Nasraddin. The ensuing debate between Fiyuzat and Molla Nasraddin reached such intensity that their rivalry is now regarded as a milestone in the history of language reform in the region (Uygur Reference Uygur2007).

It would be misleading, however, to frame the rivalry between Fiyuzat and Molla Nasraddin as a contest between an authentically Caucasian perspective and a distinctly foreign one. Hüseynzadə, a key figure in Baku’s vibrant print scene, was no less a prominent local voice than Molla Nasraddin’s editor, Jalil Mammadgulizadeh, in Tbilisi. Yet his vision had been shaped by diasporic encounters in imperial centers. Originating from a family of Shi‘i clerics in Salyan, Hüseynzadə attended high school in Tbilisi before pursuing a double degree in mathematics and physics at St. Petersburg University. His exposure to the anti-monarchist Narodnik ideology in Russia, which advocated for mobilizing peasantry against autocracy, politicized him and made him receptive to a wider range of anti-monarchist ideas. After moving to Istanbul to enroll in the Military Medical School, he collaborated there with like-minded peers to form a revolutionary group that later became known as the Young Turks. After returning to the Caucasus in 1903 to avoid increasing Ottoman scrutiny, Hüseynzadə became deeply involved in debates about the future of Muslims in Russia, arriving at his vision of Ottoman-centered cultural unity through this trans-imperial journey.

The intertwining of the local, the diasporic, and the imperial in figures like Hüseynzadə requires, in James Clifford’s words, “loosening the common opposition of ‘indigenous’ and ‘diasporic’ forms of life” (Reference Clifford, de la Cadena and Starn2007: 198–99). This entanglement of the seemingly distinct forms resonates deeply in the Caucasus where, as Bruce Grant notes, “peoples who entered as foreign and who emerged, in most cases, as native, have left many peoples of the Caucasus quite practiced in the arts of fraught cohabitation” (Reference Grant2020: 4). The dance between “foreign” and “native,” constantly shifting and merging, animated the visual tensions that gave Molla Nasraddin’s compositions their distinctive power. A caricature from 22 December 1906 crystallizes this tension: The illustration portrays a man under duress, restrained by three figures—a Russian, an Iranian, and an Ottoman—each attempting to impose their language on him (figure 6). While the seven-headed figure in the opening illustration embodies a capacious individual capable of embracing and assimilating strangers, here he appears overwhelmed, even subdued, by them. Yet these are not simply foreigners imposing an alien will. They could very well be familiar strangers, like Hüseynzadə—a Muslim from the South Caucasus turned Ottoman Turk who sought to impose his adopted vernacular on his həmşəhriləri, or fellow countrymen.

Figure 6. Cartoon, (no title), Molla Nasraddin, 22 December 1906. Illustrator: Oscar Schmerling. Image reproduced by Azərnəşr (vol. 1, 1996).

Within the Caucasus worlds, the potential to morph into powerful strangers and the risk of being overwhelmed by them were two sides of the same coin. Which side one saw hinged on the moral evaluation of the transformation: Was it enhancement or degradation? What potentials were unleashed or suppressed? What virtues were remembered or forgotten? By providing a vibrant platform for such moral debates, Molla Nasraddin did not merely represent the seven-headed public but animated its world into being. It did so through its intertextual conversation with the writings of peripatetic individuals such as Hüseynzadə and Maraghei, who moved between different imperial publics, passing through or returning to the Caucasus.Footnote 20 Through the magazine’s pages, seemingly peripheral subjects emerged as sophisticated actors, embodying and navigating different projects of cultural personhood—whether as Ottoman Young Turks, Iranian patriots, or Russian Muslims. By juxtaposing different aspects of this mobile public to reveal their correspondences and disjunctures, the magazine invited readers to think through, laugh at, and take positions vis-à-vis the familiar strangers within their midst.

Juxtapositions at the Crossroads: Familiar Strangers and the Art of Becoming Other

George Simmel (Reference Simmel, Oakes and Price2008) defines strangers as individuals who, despite being part of a group, remain distinct from its “native” members due to their external origins. Unlike transient foreigners who come and go, strangers maintain a constant relationship with the group while being perceived as somewhat alien. Molla Nasraddin’s cartoons were populated with such figures, whose distance from one another could abruptly collapse or expand unpredictably. On the unstable ground of swirling revolutionary currents, strangers might seem remarkably familiar, while familiar figures could suddenly turn into strangers. The inter-imperial public that emerges in Molla Nasraddin should thus be understood not through who its members were but through who they could become.

An illustration from 1 February 1910 presents six consecutive images of the same man (figure 7). As his outfit and posture change in each shot, we witness a sober mullah from Ganja gradually transforming into a playful gentleman in Tbilisi. Without knowing that this transformation occurs within the Caucasus, one might easily mistake it for the evolution of an Iranian mullah into a Russian gentleman. In fact, that is precisely the point this tongue-in-cheek portrayal of a “mullah’s progress” underscores: cultural types within the Caucasus are rooted elsewhere, and individuals can grow into them in a relatively short time.

Figure 7. Cartoon, “A Mullah’s Progress in a Decade,” Molla Nasraddin, 1 February 1910. Illustrator: Unknown. Image reproduced by Çınar-Çap Nəşriyyatı (vol. 3, 2005).

This visual sequence illuminates a perspective on cultural difference that emphasizes possibilities rather than fixed identities, revealing a form of social encounter that takes things seriously but not literally. In the revolutionary Caucasus, where cultural personhoods were closely associated with specific imperial domains, difference did not emerge in absolute terms, but rather provisionally, through recurring cycles of differentiation and symbiosis. This perspective suggests a more nuanced relationship between the local and the imperial, where mutual influence and integration carried elements from each into new contexts.Footnote 21 Through these cycles of exchange, the seemingly foreign could reveal unexpected undercurrents of familiarity, while the ostensibly familiar could become strange and remote when displaced.Footnote 22

Such modulations, as depicted in Molla Nasraddin, did not always require a complete reinvention of self. Instead, people could gradually adopt new elements—different clothes, hats, grooming styles, or even ways of carrying themselves. To the extent that these outward changes were perceived to signal deeper shifts in a person’s character or telos, they became subject to moral examination. On 14 October 1908, Molla Nasraddin directly addressed Muslim mothers, cautioning them about a growing trend in Tbilisi with Muslim parents entrusting their children to Russian families during their studies in Russian schools:

At the age of six or seven, the Muslim child, upon entering the Russian household, starts slowly speaking Russian. Gradually, they adapt to katlet (Russian cutlet) and forget the kofta, embrace Mariyas, and forget about Zeynabs…. Upon returning to their homeland, they begin to converse with Aunt Fatma in Russian. Five or six years later, they become so accustomed to the Russian way of life that they enjoy their good and bad deeds alike. Eventually, they start looking down upon Muslims while proudly showcasing their Russian lifestyle.

Like these shifts in daily habits, the adoption of names and patronymics served as a gauge for assessing one’s cultural orientation. In a humorous anecdote from 13 June 1906, Mozalan—one of Məmmədquluzadə’s pseudonyms according to Agayev (Reference Ağayev2007)—recounts his quest for a dentist in Vladikavkaz, a city in the North Caucasus. Following directions from locals, he encounters various establishments with names displayed in different scripts, such as “Aliakper Aliakperovich Aliyev” in Cyrillic and “Quseyn Amirovich Quseynov” in Latin. Unable to find a dentist among these Russified Muslim names, Mozalan ironically shares with a shopkeeper how the town’s Muslim residents have embraced progress by adopting Russian naming conventions. The shopkeeper shares a comical tale about a seminary student named Ali who, fearing his classmates would mock his Muslim name, asks his father to address his monthly stipend to “Alyosha Aleksandrovich” instead. Haji Isgender, the father, wryly responds, “You changed your name, fine. But turning me into Aleksandr in my old age?”

Molla Nasraddin’s editorial from 15 September 1908 highlighted the logistical challenges faced by the magazine due to frequent changes in subscribers’ names. Managing address changes and complaints about undelivered issues, the editors struggled with multiple patronymics and honorifics associated with each account. The editorial, titled “Muslim Names,” provided an example of a subscriber who was recorded under various names, including Mirza Ahmad Ahmadzada, Aga Muhammad Ahmed oglu, Muhammad Bey Ahmadov, and Muhammad ibn Ahmad. “We would mistakenly record four different names,” the editorial noted, “only to later discover that these four names referred to the same individual.”Footnote 23

These interchangeable cultural markers—from culinary and sartorial preferences to the choice of patronymics—reflected a remarkable characteristic of a local landscape that straddled three imperial worlds. In their most pronounced extremes, Turkic-speaking Muslims inhabiting this historical borderland might appear more similar to people from neighboring empires than to their local neighbors. The social proximity of these extremes is vividly illustrated in the cast of characters that opens Cəlil Məmmədquluzadə’s play, Anamın Kitabı (My mother’s book), which he wrote after closing Molla Nasraddin in 1917 in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. Published in 1920, the play features the following cast:

Rustәm bey—Wearing Russian attire: a jacket, a razor, a starched button-up shirt, a scarf around the neck, and starched white sleeves. He is a supporter of Russian education and upbringing, having graduated from a Russian university. He moves slowly and cautiously. Always with his head uncovered and wearing glasses. He is forty years old.

Mirzә Mәhәmmәdәli—Wearing Iranian religious clothing, including a tall Iranian hat, a long Iranian cloak, a thick robe over the cloak, a long Iranian tunic, loose trousers, and white socks. He takes off his shoes at the door and sits on the floor. He always carries prayer beads and wears glasses. He rarely smiles and looks serious. He supports Iranian culture and education. He is thirty-five years old.

Sәmәd Vahid—He studied literature in Istanbul. He wears a red fez on his head, and his attire includes a jacket, a razor, a white button-up shirt, and a scarf around his neck. He wears glasses and is calm and composed. He supports Ottoman culture and education. He is thirty years old.

Gülbahar—She is beautiful in appearance. She wears the common Muslim girls’ clothing, with a scarf on her head. She is pious in a Muslim manner and deeply cherishes her mother. She is twenty years old.

Zivәr xanım—She has received a Russian education. She wears Russian women’s clothing. Her neck and arms are uncovered, and she lacks Muslim modesty.

Qәnbәr—He has a fair complexion. He wears a tattered robe, a belt, and sandals. He carries a whip in his hand.

Aslan bәy—He resembles Rustam bey in all respects.

Mirzә Bәxşәli—He resembles Mirzә Mәhәmmәdәli in all respects.

Hüseyn Şahid—He resembles Samad Vahid in all respects.

Senator Mirzә Cәfәr bәy—Wearing Russian official clothing. He wears glasses.

These characters, though rendered as satirical types seemingly from different societies, coexist in a single village, held together through kinship and neighborly bonds. The first four are siblings. Zivәr xanım is Rustem bey’s wife, and the three individuals who resemble the first three characters “in all respects” are marriage candidates for Gülbahar. The remaining two are local notables closely connected to the family. Through this familial microcosm, we see how cultural differences that seem to originate in distant lands converge intimately in the Caucasus, sometimes under a single roof. If mobility of activists and traders spun a social tissue connecting the Caucasus to different imperial worlds, those worlds were writ small in the form of different cultural personhoods brought side by side within the region.

In Molla Nasraddin, these fraught intimacies could be scaled up by way of further juxtapositions to index unexpected connections and stark contradictions across imperial boundaries. A vivid illustration of this technique appears in a two-part caricature from 3 December 1913 (figure 8). The first part depicts an illegibly grandiloquent speech by an Ottoman Turk from Istanbul, which is met with a dismissive retort from an Iranian Turk in Tabriz: “What on earth are you talking about? In Tabriz, our samovar boils like three cauldrons at the public bathhouse.” The Ottoman speaker, entangled in pretentious rhetoric, fails to communicate effectively despite shared ethnolinguistic ties, while the Iranian speaker, absorbed in superficial pride, contributes nothing of substance. The second part shifts to a geopolitical critique, juxtaposing Ottoman writer-statesman Suleyman Nazif Bey with Russian journalist-publicist Mikhail Menshikov. Nazif Bey appears as a snake, willing to marry his daughter to Bulgarians or Greeks but not to a Shi‘i Turk—revealing how his sectarian prejudices belie his public advocacy for Islamic unity. Meanwhile, Menshikov, a Russian nationalist, sheds crocodile tears while professing concern for Muslims. The caricature literalizes their hypocrisies by connecting their serpentine tails, binding together their parallel deceptions.

Figure 8. Cartoon, “A Conversation between Two Turks” and “Two Respected Protectors of Islam,” Molla Nasraddin, 3 December 1913. Illustrator: Josef Rotter. Image reproduced by Çınar-Çap Nəşriyyatı (vol. 4, 2008).

Such strategic contrasts defined the magazine’s visual repertoire: whether revealing the cultural gulf between supposedly kindred peoples, exposing shared hypocrisies beneath political rivalries, or bringing daily experiences into dialogue with geopolitical pronouncements. With such compositions, Molla Nasraddin presented its inter-imperial public not through harmonious fusion but through elements in constant tension—a tension that could either bind them together or pull them apart. Whether readers perceived imminent chaos or provisional order in these elements, the sense of a shared fate remained unmistakable. The magazine’s commitment to revolutionary change in neighboring domains was deeply rooted in this sense of intertwined futures, resonating with both itinerant activists traversing these empires and readers whose attention constantly turned to developments beyond their borders.

As revolutionary movements swept across the Russian, Iranian, and Ottoman empires, the magazine sought to memorialize this palpable sentiment of shared fate through a special wall calendar for 1909. The calendar, announced on 8 December, was designed to feature “prominent figures of Russian Muslims depicted in five colors,” alongside “the heroes of the Ottoman Revolution, Niyazi Bey and Enver Bey, and the Iranian mujahideen-martyrs Jahangir Khan and Malik al-Mutakallimin.” This remarkable visual synthesis reflected an inter-imperial awareness that brought revolutionary figures from different imperial contexts into a single frame. Through such bold visual gestures, Molla Nasraddin did not just report on revolutionary changes across imperial boundaries—it helped its readers see themselves as partaking in the same transformative moment.

A Pan-Caucasian Vision and Its Eclipse

Molla Nasraddin was not alone in weaving together the revolutionary currents of three empires. Its Caucasus-centered satirical vision found parallel expression in Khatabala (meaning misfortune), an Armenian satirical magazine also published in Tbilisi (1906–1916). Armenian activists shared similar patterns of trans-imperial mobility and revolutionary spirit with Turkic-speaking Muslims (later Azerbaijanis) at the turn of the twentieth century. However, their distinct cultural markers—a unified ethnic name, an ancient Apostolic Church, and their unique script—made them readily traceable in imperial archives, unlike their Turkic-speaking Muslim counterparts in the region who often went under the radar as Iranians, Turks, Tatars, or Muslims.

This correspondence between satirical visions extended further still. Eshmakis Matrahi (The Devil’s whip), a Georgian satirical weekly published in Tbilisi (1907–1916), would emerge to complete this triumvirate of Caucasian critique (figures 9a, 9b, 9c). Remarkably, all three publications were illustrated by the same Georgian artist, Oskar Schmerling.Footnote 24 That these publications—Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Georgian—shared not just an illustrator but an approach to viewing imperial relations suggests something broader about the Caucasian position at this historical moment.

Figures 9a, 9b, 9c: Three covers of Molla Nasraddin (7 February 1910), Khatabala (17 June 1906), and Eshmakis Matrahi (10 August 1908). Illustrator: Oscar Schmerling. Images from Beyond Caricature: The Oskar Schmerling Digital Archive, https://schmerling.org/en.

This central position opening the Caucasus at once to three empires unraveled with another series of near-synchronous developments: the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Turkish Independence War in 1919, and the Pahlavi coup in 1921. As the new regimes emerging from these upheavals consolidated their power in 1920, 1923, and 1925, respectively, their parallel foreign policies of nonintervention and domestic policies of national homogenization pulled the rug from under these three magazines. Before it disappeared, this shared regional consciousness crystallized, however briefly, in the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, founded in 1918 by Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis. Though the Republic dissolved within a month of its establishment, it left behind a striking artifact: a banknote that juxtaposes the languages of these three neighbors, enshrining their proximity on paper—a final testament to the possibility of pan-Caucasian unity (figure 10).

Figure 10. Banknote issued by the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, May 1918. Original copy with the author.

The Bolshevik takeover of 1920 transformed the Caucasus irrevocably. Although Molla Nasraddin outlived its sister publications—surviving first in Tabriz for eight issues in 1921, then in Baku from 1922 to 1931—its persistence belied a deeper transformation. When Cəlil Məmmədquluzadə returned to the Caucasus at the invitation of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, both the region and his magazine had fundamentally changed. The vibrant inter-imperial crossroads had become a periphery within a socialist empire of nation-states, and Molla Nasraddin’s voice adapted accordingly. Its Soviet debut on 2 November 1922 featured a telling meditation on the Arabic word shura (Soviet, in Russian)—a familiar Islamic term carefully repurposed to capture the essence of Soviet rule. Even more revealing was the change in the magazine’s scope: where its early telegrams had once connected imperial capitals with sweeping views of revolutionary transformations, its Baku-era dispatches now focused narrowly on the Soviet Union and its Caucasian periphery. In this shift from broad imperial vistas to confined Soviet horizons, we see how a distinctive Caucasian perspective on empire gradually faded from view, dissolving along with the inter-imperial terrain it had helped cultivate.Footnote 25

Conclusion

In mapping the expansive cultural geography of early twentieth-century Caucasus through the lens of Molla Nasraddin, we have discovered in the seven-headed figure not a mere comical oddity but a profound expression of how empire appears from spaces of multiple imperial convergence. Emerging powerfully from the magazine’s pages is a sophisticated engagement with empire: one that can invest in different imperial projects, while maintaining the critical distance to expose their deep connections, parallels, and tensions. Rigid taxonomies that rest on spatial distinctions of center and periphery, cultural oppositions of indigenous and foreign, and political binaries of resistance and accommodation falter before such protean engagements.

Through its polyglot Turkic/Eurasian profile and its steadfast yet mercurial platform, where the playful and serious intermingled unpredictably on a weekly basis, Molla Nasraddin fostered a distinctive form of inter-imperial literacy. Collectively cultivated by activists, publicists, and readers, this literacy could bridge distant places and personhoods across imperial boundaries. Recovering the perspectives illuminated by this literacy demands we fundamentally reorient our historical gaze—viewing empire not from its self-proclaimed centers but from its creative borderlands, not through authoritative accounts but through unsuspected genres, learning from these spaces where multiple imperial worlds converged to offer views of empire both intimate and askance.

This reorientation takes on renewed urgency today, as Turkey’s, Iran’s, and Russia’s competing influences breathe new life into old imperial borderlands, while China’s Belt and Road Initiative traces new pathways across these long-standing zones of cultural translation and critique. Rather than analyzing these neo-imperial overtures through conventional frameworks of domination and resistance, the Caucasian experience suggests examining how communities in these historically contested spaces can draw upon deep reservoirs of imperial engagement to forge new forms of inter-imperial literacy, transforming apparent constraints into resources for cultural and political renewal just as their predecessors did. At a time when the world seems increasingly trapped between the twin dead ends of insular nativism demonizing external engagements and untethered cosmopolitanism floating above local concerns, recovering these borderland engagements with difference lights another passage.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply indebted to Bruce Grant, Thomas Blom Hansen, Engseng Ho, Ameem Lutfi, Nisha Mathew, Kabir Tambar, and the anonymous reviewers at CSSH for their critical insights that honed this work to its essence.