Introduction

The illegal wildlife trade is a lucrative environmental crime. The scale is vast and as a result estimating its extent is challenging. Current estimates suggest environmental crime is worth as much as USD 23 billion per year (Nellemann et al., Reference Nellemann, Henriksen, Kreilhuber, Stewart, Kotsovow and Raxter2016), making it the fourth most valuable illicit transnational trade after the trafficking of narcotics, humans and counterfeit items (UNGA, 2015). With its global reach, the internet has become the focus of concern in control of the illegal wildlife trade, with trade occurring over a variety of platforms, including auction websites (Hernandez-Castro & Roberts, Reference Hernandez-Castro and Roberts2015) and social media (Yu & Jai, Reference Yu and Jai2015; Hinsley et al., Reference Hinsley, Lee, Harrison and Roberts2016); little has been found on the dark web (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro2016; Roberts & Hernandez-Castro, Reference Roberts and Hernandez-Castro2017). Governments and businesses have been called upon to take action to tackle the growing illegal online wildlife trade (WWF & Dalberg, 2012). However, identifying suspected illegalities online is time consuming, often involving manual keyword searches (Hernandez-Castro & Roberts, Reference Hernandez-Castro and Roberts2015).

In the online trade, the term ivory is used both for the material (including elephant, mammoth, hippopotamus, narwhal and walrus tusks, and sperm whale teeth) and for the colour. As such, use of the search term ‘ivory’ will result in a large proportion of unrelated items (Hernandez-Castro & Roberts, Reference Hernandez-Castro and Roberts2015). Furthermore, with the push for businesses to ban the trade in ivory and adapt to current legislation (e.g. eBay's ban on items with > 5% ivory; Coghlan, Reference Coghlan2008), the trading community has developed a number of code words to disguise the trade. Added to this already challenging situation, it is unclear whether these code words are common within the trading community or specific to a particular country, language or trading community.

In this study we analysed the use of 19 code words for elephant ivory (IFAW 2014; and used in a previous study: Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro2016) across eBay market places in four linguistically different European Union (EU) countries. Understanding how search terms associated with the illegal wildlife trade, including code words, are used across different languages will help inform future research into the illegal online wildlife trade and streamline manual search by law enforcers.

Methods

The research was conducted on the open, publicly available, auction website eBay, across four linguistically different eBay market places, namely eBay UK (ebay.co.uk), eBay France (ebay.fr), eBay Italy (ebay.it) and eBay Spain (ebay.es). eBay was chosen because previous studies had shown continuing trade in elephant ivory (e.g. Hernandez-Castro & Roberts, Reference Hernandez-Castro and Roberts2015) and it represented a stable platform used across several countries. The specific market places were selected based on the linguistic abilities of SA, and because they fall within the EU, allowing free trade between member states.

Following Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro2016) we consulted a list of 30 code words and phrases previously identified (IFAW, 2014) as being associated with the online trade in ivory products. Of the 30 code words, 19 were selected; excluded words or phrases were those that represented redundancy, were too generic or had an unreliable translation. Each code word was translated from English to French, Italian and Spanish. During the analysis each code word was anonymized and assigned a random alphabetical letter, to avoid compromising ongoing enforcement efforts.

A systematic search was conducted over a 21-day period (18 January–5 February 2017; this was the time taken to conduct a single search of each of the four websites using all the code words. For consistency, searches for a particular code word were conducted at the same time across all four market places, restricted to the Header and Description of the advertisements, and the Antiques section. Each search was performed only once. All items of the search results were scrutinized if the total number of items was < 5,000. In cases where searches resulted in > 5,000, a sample of the first 100 items were analysed, because of time availability. For each elephant ivory item identified, the details and sale characteristics (i.e. code word used, item number, seller's username, item location, postage options and information regarding the object's age and certifications) were recorded. Postage options were categorized into Within country, Within the rest of the EU or Outside the EU.

Given the lack of access to the physical items, identification of elephant ivory items was based on the most precise available indicator, which was the presence of Schreger lines in the images (a unique structure indicative of elephant ivory; Locke, Reference Locke2008), the only other characteristic being the shape of the item in the case of unworked ivory. An alternative option that was not used was to discount other materials associated with ivory, such as man-made materials, bone, horn and antlers, and other ivories, including hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whale and walrus, based on attributes specific to them (e.g. shape; Espinoza & Mann, Reference Espinoza and Mann1999). A 2-person Kappa analysis was performed using a sample of 100 items to test identification consistency for elephant ivory among researchers (i.e. raters 1 and 2; rater 1 was SA and rater 2 was a colleague who had a similar amount of experience researching online trade in elephant ivory). Cohen's Kappa was calculated to confirm identification consistency. Differences in the classification of items were then discussed among researchers until an agreement was reached.

Results

Identification consistency

There was a good level of agreement between the two raters in identification of elephant ivory (k = 0.67, P < 0.01). A technical issue experienced by rater 2 when using eBay's image zoom feature was identified as the main cause of difference in classification of items. After reanalysis following the correction of the problem, agreement was achieved for 14 of the 15 disputed items (k = 0.98, P < 0.01).

Characteristics of sale items

A total of 15,152 advertisements resulted from a search using the 19 code words across the four websites, leading to the identification of 183 unique elephant ivory items. Of these, 84 (1.14% of the total number of advertisements analysed on a country's website) where found on eBay UK, 55 (1.42%) on eBay France, 44 (1.42%) on eBay Italy and 42 (6.35%) on eBay Spain. These items where offered for sale by 113 unique sellers. Most sellers (n = 86, 76%) were offering a single ivory item at the time of the survey, with a median of 1 item per seller and a maximum of 14 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Number of sellers with one or more ivory items for sale across four eBay sites.

Of the 21 items located outside the EU trading area, 20 were in the USA and one was in Israel (Fig. 2a). All other items were located within the EU in the four countries of study, except for a substantial number that were for sale in Germany (n = 26, 14%). There was a significant difference in the distribution of items on offer among the categories Within country and Within the rest of the EU in each of the four countries’ eBay sites (χ 2 (3) = 51.3, P < 0.05), with the UK being underrepresented and Spain overrepresented in terms of numbers of items located within the EU. The category Outside the EU was excluded from the test because, based on the data collected, it applied only to the UK.

Fig. 2 Number of ivory items found (a) per physical location of the item being offered and (b) per postage option on the four eBay websites searched.

In terms of the postage options available for the items whose physical location fell within the four countries of study (n = 59 for the UK, n = 35 for France, n = 23 for Italy and n = 12 for Spain), there was a significant difference across countries (χ 2(6) = 31.6, P < 0.01), with Spain being overrepresented for number of items for sale within the EU (Fig. 2b). Because of several low expected counts (41.5%), a Fisher's exact test was also conducted, producing a similar result (P < 0.01).

Information regarding the declared age of the items and certifications was found in the Header or Description of most items (n = 139, 76%). One object was reported to have an antiquity certificate, 82 (45%) were dated by sellers as pre-1947, although without using the term ‘pre-convention’, and 40 (22%) were simply described as ‘antiques’. A minority were also described as ‘vintage’ (n = 7), ‘old’ (n = 3) or ‘original’ (n = 2). Only one Italian seller reported holding CITES permits for both items found for sale. Two sellers explicitly mentioned eBay's Terms and Conditions in relation to the sale of elephant ivory. Five of the items where in the recognizable form of tusks, either highly polished or carved but still obvious because of their shape.

Code word and phrase usage

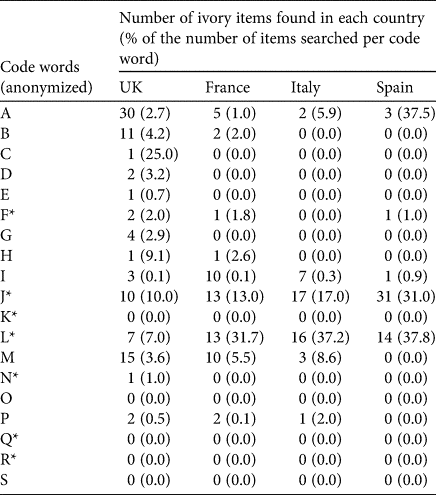

Of the 19 code words analysed, six accounted for nearly 80% (n = 276) of the total number of elephant ivory items found for sale across the four eBay websites (Table 1). Code word usage was compared across countries through the analysis of their rank order. There were significant correlations between pairs of countries in the rank order of the code word hits, with P < 0.01 for each pair (France vs Italy r s = 0.876, France vs Spain r s = 0.797, Italy vs Spain r s = 0.874), except for all comparisons with the UK (UK vs France r s = 0.701, UK vs Italy r s = 0.595, UK vs Spain r s = 0.668), which were significant at P < 0.05. Results for code words with a fixed sample size of 100 items were excluded from this analysis to avoid biases, as they are possibly not representative of the complete list of items.

Table 1 Number of ivory items found per code word on the four eBay websites searched.

* Code words whose search was limited to the first 100 items.

Discussion

Although ivory sale on eBay has been banned since 2009 (Coghlan, Reference Coghlan2008), elephant ivory is still being offered for sale across the four countries examined. However, as noted previously (Yeo et al., Reference Yeo, McCrea and Roberts2017), three-quarters of the trade was by sellers offering only a single item; although one individual was offering 14 items, the next highest number of items offered by a single seller was six items (Fig. 1).

Besides two sellers explicitly making the false statement that they complied with eBay's Terms and Conditions (eBay 2017a,b,c), a number of analysed items were potentially illegal for reasons other than the violation of the website's regulations, specifically regarding international, EU and national legislation. Most sellers identified in this study were willing to sell outside the EU, and made no explicit mention of whether the items were ‘pre-convention’ (45% were described as pre-1947) other than wording related to the age of the item (e.g. ‘antique’). There was a further lack of acknowledgement regarding the need for a CITES permit for international trade, particularly into and out of the EU. Presence of a CITES permit was mentioned by only one seller, who was not willing to send the two items for sale outside the country. Five items of ivory were found to potentially violate the EU's regulations, as they may be unworked ivory. Although in most cases the tusk was carved, the shape was still obvious; defining what is worked or unworked is contentious (DLR, pers. obs.). According to the EU regulations Article 2w of Regulation (EC) No 338/97 defines worked ivory to be ‘specimens that were significantly altered from their natural raw state for jewellery, adornment, art, utility or musical instruments … Such specimens shall be considered as worked only if they … require no further carving, crafting or manufacture to affect their purpose’. Pre-convention antiques that remain substantially unaltered from their natural state (i.e. are still in the form of a tusk) do not qualify as ‘worked specimens’.

There were differences between countries in the volume of ivory items for sale, with a higher volume in the UK. The lower overall volume of ivory items found on eBay France, Italy and Spain could be a result of the sellers’ preferential use of alternative auction websites. Unlike other countries, there were a higher number of items being offered from outside the EU (mainly USA) into the UK. In contrast France, Italy and Spain had high numbers of items for sale from other EU countries, notably from Germany.

Identification of elephant ivory items based on the unique Schreger lines was found to be consistent, even after only brief training. However, the number of photographs and their quality was a limiting factor. Although Schreger lines appear to be a simple and reproducible method for manual identification of online trade in elephant ivory, basing identifications purely on the presence of Schreger lines probably leads to an underestimation of the total volume of ivory for sale.

Unexpectedly, there were correlations in usage of code words across the four EU countries, even though they differ linguistically, suggesting such conventions may be to some extent homogeneous beyond individual markets. Correlations were highest between France, Italy and Spain, potentially because of the close linguistic relationships. Of the 19 code words associated with the trade in elephant ivory, six comprised the majority of the items traded. Restricting the code words used in a search would therefore reduce the amount of effort if the search was manual. Should new code words be identified, it would be beneficial to share these between law enforcement agencies, even if there are linguistic differences. Machine learning, based on code words and other attributes of advertisements for elephant ivory (e.g. Hernandez-Castro & Roberts, Reference Hernandez-Castro and Roberts2015), offers opportunities to automate the process of identification for law enforcement agencies and for marketplaces such as eBay, as part of their own policing.

Illegal wildlife trade is a lucrative transnational environmental crime that warrants concerted control (Economic & Social Council, 2013). The internet offers a global reach to sellers and buyers, and potentially presents enforcement officers with a problem because of the scale. However, the global market may result in homogeneity of conventions for communication. In the case of sale of elephant ivory, code word usage was comparable across the four countries and translatable across the four languages. It is less clear how these conventions translate across different online platforms, such as between free-text social media and classified advert platforms (e.g. Facebook and Craigslist), or structured auction sites (e.g. eBay), or other platforms that use limited text and/or tags (e.g. Instagram or Twitter). We therefore suggest that further research should explore the characteristics of these other platforms. However, if there is a digital fingerprint of ivory trade across platforms, languages and countries, monitoring could potentially be more manageable.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emelyne Potier for taking part in the Kappa analysis, and Julio Hernandez-Castro for providing technical advice in the design of the study.

Author contributions

Conception of the project and writing of the text: DLR; data collection and analysis: SA; writing of the manuscript: both authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the University of Kent's Research and Ethics Committee (ref. no. 0321617).