What role does the Internet, and specifically social media, play in the dynamics of mobilization? Over the last decade this question has become a major concern for scholars interested in contentious politics, as numerous mass movements and popular uprisings have emerged – from Hong Kong, to Turkey and Iran, to Ukraine, to Chile and Brazil – in which social media platforms appear to have had a major impact. Early accounts of the Arab Spring uprisings also granted social media a central role; at points these movements were even dubbed ‘Facebook revolutions’ or ‘Twitter revolutions’. Yet scholarship on the Internet and mobilization has yet to fully make sense of how these platforms mattered in these and other instances of mass protest.

Part of the problem, we believe, is that scholars have tried to answer too many big questions about too many cases, using too little data. Some existing scholarship on the role of the Internet in politics proposes theories framed in overly expansive terms, often based on extrapolations from the Internet’s presumed technical possibilities: for example, that it will have profound (positive or negative) effects on the practice of democratic politics (Morozov Reference Morozov2012; Shirky Reference Shirky2009), or that it will fundamentally alter the logic of collective action and social movement organization (Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012; Castells Reference Castells2015; Earl and Kimport Reference Earl and Kimport2011; Loader Reference Loader2008). We agree with Henry Farrell, who has argued in a review of this literature that ‘one should disaggregate [the Internet] into more discrete phenomena, allowing scholars to ask research questions that they have some hope, however faint, of answering’ (Farrell Reference Farrell2012, 36). We also agree with R. Kelly Garrett that more attention to context might help scholars to parse the potentially diverse effects of communication technologies on various outcomes (Garrett Reference Garrett2006). In this spirit, our goal is to present an argument that: (1) shows concretely how two social media platforms may have contributed to a specific mobilizational outcome, (2) is anchored in the single case of the 2011 Egyptian uprising and (3) is supported by a host of qualitative and quantitative data.

Specifically, this article analyzes how the social media platforms Facebook and Twitter were used to mobilize the Egyptian uprising’s ‘first movers’, or those individuals who participated in the protest on 25 January 2011 against the regime of President Hosni Mubarak. The analysis suggests that the use of these platforms contributed meaningfully to the success of this protest, by increasing turnout levels, facilitating simultaneous demonstrations across multiple sites nationwide and allowing protesters to coordinate actions in an apparently leaderless manner. Success across these three dimensions helped to convince many other Egyptians to join in subsequent protests, thus setting in motion a revolutionary cascade that resulted in the ousting of Hosni Mubarak from power. We also propose that these platforms were important for producing this outcome through three discrete mechanisms. Facebook was used for (1) movement recruitment and (2) protest planning and coordination, and Twitter was important for (3) providing live updates about protest logistics on the day of the event.

The ‘First-Mover’ Problem in Revolutionary Cascades

Scholars of collective action have often puzzled over the problem of ‘first movers’ in mobilization. The problem, first identified by Mark Granovetter in his work on ‘thresholds’ (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1978) and later elaborated in Timur Kuran’s theory of ‘preference falsification’ (Kuran Reference Kuran1997), is that most people will only participate in mass protest when they see many others doing so. Even if they harbor deep antipathies toward a political authority or leader, individuals will usually not act on those sentiments alone or in small groups. In other words, individuals have what Kuran called a ‘revolutionary threshold’ – a level of mass mobilization at which they will overcome their inhibitions and enter the streets to call for change. Granovetter argued that this is why many rebellions follow a cascade pattern: an initial thrust of mobilization motivates a group of fence sitters to join in, which in turn pushes protest levels across the threshold for a third group of individuals, and so on, until a mass uprising ensues.

Whereas other theories of revolution emphasize the broader structural conditions that make revolution possible (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1994), cascade models of revolution call attention to the importance of staging a successful first protest. The first protest is key because it has the potential, if it is successful, to convince the multitudes watching ‘from the fences’ that there is broad anti-regime sentiment in society and that subsequent protests are likely to be just as big, if not bigger. In other words, a successful first protest reveals formerly falsified preferences among considerable segments of the population and pushes the next potential wave of protesters across their revolutionary threshold.

But if the cascade model of revolution emphasizes the importance of organizing a successful first protest, it says less about how activists might go about staging such an event. More specifically, how do political activists mobilize enough first movers to stage an initial protest that will convince cautious fence sitters to join in subsequent waves of protest?

We define activists as individuals who organize and initiate anti-regime protests. First movers are those who participate in the first protest of a (potential) revolutionary cascade. Though this group includes the political activists and leaders who help organize such a protest, it also includes regular citizens who may not be political activists but who nevertheless join in the first protest. Fence sitters are individuals with sympathies towards a protest movement, but who will only join an uprising following a certain threshold of successful mobilization (that is, after the first protest, or later). Finally, a first protest is defined as ‘successful’ when it triggers a protest cascade.

We justify our focus on first movers not only because of their presumed theoretical importance in cascade models of revolutions, but also because in the Egypt case first-mover mobilization appears to have been crucial in triggering the 2011 uprising. The first protest on January 25, Egypt’s annual Police Day holiday, vastly exceeded expectations, convincing many Egyptian citizens and political groups with simmering grievances towards the Mubarak regime to join in the next major day of protest on January 28.Footnote 1 This protest, dubbed the Friday of Anger, drew so much support that it overwhelmed the regime’s supposedly indomitable security forces, causing them to withdraw from the streets and allowing protesters to occupy Tahrir Square, in the center of Cairo. Over the next fourteen days several more major protests were staged (on February 1, February 4 and February 11), with each one’s turnout exceeding the one before it. On the final day of protest, February 11, 2011, well over a million Egyptians took to the streets and Mubarak was finally forced to resign.Footnote 2

The dynamics of Egypt’s revolution therefore closely align with the patterns predicted in cascade models of revolution. Moreover, Egypt’s cascade dynamics are indicative of protest patterns in other cases of what Mark Beissinger calls ‘urban civic revolutions’ – revolutions based on rapidly amassing large numbers of civilians in central urban spaces (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2013). If, as Beissinger argues, urban civic revolutions are increasingly common in the post-Cold War era, we should expect that lessons derived from Egypt’s uprising may have broad relevance to other recent and future episodes of revolutionary mobilization.

Existing theories of revolutions and the emerging literature on Egypt’s uprising therefore both point to the importance of understanding how successful first protests come about. But to explain successful first-mover mobilization, we must first theorize what sorts of protest characteristics might contribute to such success. In other words, what types of protests are most likely to pull cautious citizens off the fence and encourage them to participate in subsequent protests? Cascade theories of revolution call attention to turnout: a first protest with a critical mass of participants will reveal to onlookers that a considerable number of individuals hold anti-regime sentiments, and this revelation will motivate participation in subsequent protests. But if turnout is one component of success, research on Egypt’s revolution points to at least two other potential contributors to first protest success.

First, the scope of the protest (the number of locations in which it is held) may also affect fence sitters’ calculations. A protest with broad scope indicates not only that many people hold anti-regime sentiments, but that those sentiments exist among broad and diverse segments of the population. Indeed, scholars have emphasized that a key part of the January 25 protest’s effectiveness was the fact that it occurred simultaneously in multiple cities around the country, rather than solely in downtown Cairo, as had been the case with most previous political protests (Clarke Reference Clarke2014; Gunning and Baron Reference Gunning and Baron2014).

Secondly, many accounts of Egypt’s revolution point to something unique in the quality and character of the January 25 protests; rather than an organized demonstration by a well-known political group, the protests had the appearance of being leaderless, spontaneous and horizontal, and therefore a more authentic expression of Egyptian popular will (Chalcraft Reference Chalcraft2012; Filiu Reference Filiu2011). The political scientist John Chalcraft eloquently captured the elements of this horizontalism as follows: ‘the decentralized or networked form of organizing; the leaderless protest movements; the eschewal of top-down command; the deliberative, rather than representative, democracy; the emphasis on participation, creativity and consensus’ (Chalcraft Reference Chalcraft2012, 6). Of course, as we document below, there were leaders and activists behind the January 25 event, and many Egyptians knew that youth movements had organized and called for it. But the touch of these leaders was light; their role was to set the protest in motion, not to guide it towards a particular end or outcome. Once the protests began they evolved and unfolded in a decentralized and seemingly spontaneous manner, and this palpable appearance of spontaneity convinced many Egyptian onlookers that the protests were a genuine and organic expression of the popular will, rather than a deliberate campaign organized by a single group or party. This dynamic has been cited as one reason that this protest had a more profound effect on onlookers than previous protests whose turnouts had actually been larger, but which had been organized by specific political groups.Footnote 3

Theory and existing research therefore point to three characteristics that seem to increase the likelihood that a protest will trigger a revolutionary cascade: sizable turnout, broad scope and apparent leaderlessness. These features matter because they affect fence sitters’ calculations about how costly participating in a protest is likely to be, how likely a revolution is to succeed and how content they are likely to be with the post-revolutionary order. In other words, large, broad and apparently leaderless first protests are more likely to convince wary but supportive fence sitters that participation in subsequent protests is worth the risk.Footnote 4 If these are the characteristics that are likely to define a successful first protest, we must then return to and rephrase the problem of first-mover mobilization: how do activists organize a first protest with the size, breadth and sense of leaderlessness necessary to trigger a protest cascade? This, as we explain in the subsequent section, is where social media may play a role.

Social Media and First-Mover Mobilization in Egypt

In explaining first-mover mobilization, much existing scholarship has focused on the biographies and personalities of the activists themselves. For example, Timur Kuran argues that effective first protests occur when enough individuals with ‘unusually intense wants on particular matters’ or ‘extraordinarily great expressive needs’ simultaneously come together to protest (Kuran Reference Kuran1997, 50). This explanation has a degree of plausibility; after all, those who organize such an event are likely to be particularly motivated and committed activists with the kind of ‘intense wants’ that Kuran suggests. Indeed, some scholars have noted that the activists who organized early protests during the Arab Spring were noteworthy for their courage and commitment (Lynch Reference Lynch2011; Weyland Reference Weyland2012). Others, following Doug McAdam’s argument that movement leaders usually have previous experience of protest and activism (McAdam Reference McAdam1982; McAdam Reference McAdam1989), have emphasized the political experience of the protest organizers during the years preceding the uprisings rather than their unique emotional commitments (Clarke Reference Clarke2014; el-Ghobashy Reference el-Ghobashy2011; Lawrence Reference Lawrence2017).

But accounting for the actions of movement leaders is insufficient to fully explain the emergence of a successful first protest. For, in the end, a successful first protest must include participants from beyond the core group of motivated and experienced activists. Such a group is likely to include no more than several hundred, or at most several thousand, individuals, whereas a successful first protest likely requires mobilizing considerably more individuals. In Egypt, for example, scholars estimate that the January 25 protest attracted upwards of 30,000 participants (Gunning and Baron Reference Gunning and Baron2014; Ketchley Reference Ketchley2017). The question then is how these motivated activists manage to turn out considerable numbers of first movers from beyond their immediate circles. In the case of the Egyptian Revolution, we argue that social media played a role in mobilizing this broader group of first movers.

Specifically, we argue that the social media platforms Facebook and Twitter helped significant numbers of otherwise isolated activists and citizens to identify each other, form networks and relationships, and coordinate their actions (pre-emptively and in real time) to stage the successful January 25 protests.

The argument builds on and nuances existing scholarship on the role of social media in the Arab Spring uprisings. Some have argued that social media was important, even imperative, for building the movements that launched the Arab Spring protests and forced four of the region’s autocrats from power (Brym et al. Reference Brym2014; Eltantawy and Wiest Reference Eltantawy and Wiest2011; Faris Reference Faris2013; Howard and Hussain Reference Howard and Hussain2013; Howard et al. Reference Howard2011; Lotan et al. Reference Lotan2011; Tufekci and Wilson Reference Tufekci and Wilson2012). These scholars argue, variously, that the Internet provided an arena for an alternative civil society to flourish, that it provided communication channels outside authoritarian control, that it allowed activists to discuss shared grievances and formulate a common agenda, that it led to the emergence of new collective identities, that it created an alternative public sphere and helped activists connect with sympathetic Western audiences, and that it made possible the sharing of tactics and frames across borders. Others, most prominently Marc Lynch, have offered a more sober assessment (Lynch Reference Lynch2011).Footnote 5 Though social media was clearly used during the Arab Spring protests, he points out that it is ‘surprisingly difficult to demonstrate rigorously that these new media directly caused any of the outcomes with which they have been associated’ (Lynch Reference Lynch2011, 302). Indeed, scholars examining other cases beyond the Middle East have suggested that social media may have the opposite effect on the capacity for resistance, by providing new tools for autocratic governments to manage public discourse and monitor activists (Deibert Reference Deibert2010; Gunitsky Reference Gunitsky2015; King, Pan and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013; Oates Reference Oates2013).

In many ways Lynch’s assessment of the literature on social media in the Arab Spring echoes Farrell’s general critique of research on the Internet in politics, and his call for more discrete and empirically grounded analysis. In this spirit, we hope to move beyond the shortcomings of earlier accounts by demonstrating a connection between social media and a discrete mobilizational outcome during the Egyptian Revolution: first-mover mobilization on January 25 2011.

We propose three discrete mechanisms linking social media use to the successful day one protests, and show how each of these mechanisms contributed to one of the three features of success noted above: large numbers of participants, broad national scope and apparent leaderlessness. We also tie these mechanisms to particular social media platforms, as we agree with those who have pointed out that not all Internet-based technologies afford the same types of opportunities for mobilization (Earl et al. Reference Earl2010; Farrell Reference Farrell2012). Rather, there are affinities between certain types of platforms and certain mechanisms of mobilization.

Specifically, Facebook helped with (1) movement recruitment and (2) protest planning and coordination. Facebook’s properties – ‘likes’, ‘walls’ and ‘friends’ – were well suited to these activities. They allowed activists to identify and ‘friend’ potentially sympathetic strangers, chat with them through a private chat portal, and then extend an invitation to ‘like’ a ‘wall’ that could easily be used as a message board for disseminating information about protest logistics. Facebook therefore mitigated the significant challenge that activists everywhere face – of recruiting thousands of followers and sympathizers, and disseminating information to them about the details of planned protest events so that they may act in unison. In this sense our argument follows others who propose that the Internet may facilitate collective action by lowering the costs of communication and movement organization, but it points to two more specific mechanisms that contribute to this general dynamic (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2006; Little Reference Little2016; Van De Donk et al. Reference Van De Donk2004). These two mechanisms are, respectively, tied to the high level of turnout and the significant breadth and scope of the January 25 protest.

Twitter, in contrast, was important for providing live updates about protest logistics on the day of the event. Twitter’s properties – instantaneous updating, ‘retweets’ and ‘hashtags’ – were conducive to disseminating live, real-time information about when and where protests were occurring, where the security presence was heaviest and, more importantly, where marchers were heading as they moved around Cairo and other cities. This mechanism contributed to the seemingly leaderless coordination of protester movements on the day of the protests. Although the activists who planned the protests had put in place a general framework for the day – the start time, where protesters should meet and the types of slogans that would be used – after the demonstrations began they evolved organically, without the guidance of activist leaders or organizations. For instance, live updating helped bring about the convergence of marches on Tahrir Square from around Cairo at the end of the day, which was not part of the original protest plan.

This account of how the January 25 protest was made possible is, in many ways, compatible with existing scholarly research on Egypt’s revolution. For example, there are a number of structural explanations for the Egyptian uprising, centered around factors like middle-class neglect (Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur Reference Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur2015; Kandil Reference Kandil2012), a youth bulge (Filiu Reference Filiu2011) or weaknesses in Egypt’s political economy (Achcar Reference Achcar2013; Campante and Chor Reference Campante and Chor2012; Soliman Reference Soliman2011). But these structural accounts focus on long-term trends and factors; they have little to say about the micro- and meso-level factors that led specifically to the successful January 25 event. Other accounts center on the strength of Egypt’s civil society (Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur Reference Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur2015; Dalacoura Reference Dalacoura2012), or relatedly, on the unappreciated tenacity of key oppositional sectors in Egypt, which had built up their strength in the previous decade (Clarke Reference Clarke2014; el-Ghobashy Reference el-Ghobashy2011; Gunning and Baron Reference Gunning and Baron2014). We believe these society-centric explanations are in many ways reconcilable with our argument, since many of these civic organizations and networks had built up their strength over the preceding years in part through the concerted use of social media platforms.Footnote 6 We also believe our explanation is compatible with the brokerage-centric argument put forward by this article’s first co-author in a previous piece of research (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). In this account, Clarke documents the crucial role of the ‘Cairo-based political opposition’ in orchestrating the January 25 uprising – precisely the sector that, we argue, effectively drew on and utilized social media.Footnote 7

That being said, we do wish to add some caveats regarding our argument. First, our claims about the importance of social media are limited to mobilization on January 25. Though we recognize that social media platforms were used at other points during the eighteen-day uprising, we believe their significance diminished during these later stages. The most obvious reason for this change is that for significant periods following January 25, the Mubarak regime managed to interrupt, slow down, or entirely block both Facebook and Twitter, requiring activists to fall back on more traditional communication devices. In fact, as Navid Hassanpour has argued, this media disruption may have contributed to the more decentralized and localized nature of mobilization on January 28 (Hassanpour Reference Hassanpour2014).Footnote 8

Moreover, two surveys conducted in the aftermath of the revolution – one of everyday citizens and one of participants in the 2011 uprising – further justify our focus on social media use on this first day. The first is Wave II of the Arab Barometer project – a set of nationally representative surveys about political life and social values in eleven Arab countries, including Egypt (n = 1,219).Footnote 9 The second is Zeynep Tufekci’s and Chris Wilson’s survey on media usage patterns during the revolution, conducted less than a month after the protests ended (Tufekci and Wilson Reference Tufekci and Wilson2012). Unlike the Arab Barometer survey, which is nationally representative, this survey (hereafter TDS, or Tahrir Data Set) used snowball sampling to survey only respondents who participated in protests during the revolution (n = 1,048). These surveys together show that social media use was higher among participants in the January 25 protest than among Egyptians who participated in later days of protest, who, in turn, used social media more than those who did not participate in the revolution at all. Statistical analyses further demonstrate that social media usage during the revolution was the strongest predictor of participation in the first day of protests when compared against use of all other media and information sources.Footnote 10 We believe this survey evidence further justifies our emphasis on social media’s role in first-mover mobilization.

A second caveat concerns the causal nature of our claims. Though we argue that social media use contributed to the success of the January 25 event, we do not claim that it was solely or crucially responsible for this success. The most obvious additional catalyst was the revolution in neighboring Tunisia which, as many scholars have noted, contributed to a new sense of possibility and hope regarding political change in Egypt. Participants in the January 25 protests were almost certainly influenced by the example of Tunisia’s revolution, and the effect of January 25 on fence sitters was likely enhanced by the recent Tunisian precedent. Furthermore, it is undoubtedly true that many non-social media communication methods, like mobile phones, emails and face-to-face communication were used to spread the word about the January 25 event and to broker the participation of different groups (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). Social media platforms clearly interacted with (and may have even enhanced the efficacy of) these other, older communication technologies, but they did not supplant them entirely.

In lieu of a more sweeping argument about social media’s impact, we aim to show simply that social media was used in important and meaningful ways by the activists who organized the January 25 protest and the Egyptians who joined it, and that this extensive use contributed to its size, breadth and character. In other words, though we do argue that Facebook and Twitter were consequential for the success of January 25, we do not make the (ultimately unprovable) claim that this event, or the Egyptian revolution more broadly, could not have happened without the presence of social media. This counterfactual is impossible to assess. Many revolutions have been staged throughout history using tools other than social media, and Egypt’s successful day one protest might well have been orchestrated through other means had social media platforms not been available. But we do believe that by carefully tracing the mechanisms connecting these two platforms to the three discrete outcomes noted above, we can establish that – in this case, at this time – social media use was consequential for first-mover mobilization.Footnote 11

The analysis proceeds as follows. First, we analyze the two mechanisms most directly associated with Facebook – movement recruitment and protest planning and coordination – to demonstrate how this platform contributed to the protest’s considerable size and scope. We then do the same for the mechanism associated with Twitter: live updating. Finally, we conclude. Throughout the article we draw our inferences from a diverse range of data: interviews conducted with thirty-three Egyptian activists in the summer of 2011 and the spring of 2017,Footnote 12 scraped Twitter data associated with the hashtag #jan25, and the content of material on key activist Facebook pages.Footnote 13 We also occasionally cite descriptive statistics from the two surveys noted above, though the bulk of our analysis of these data is presented in Appendix B.

Facebook: Recruitment and Protest Planning

The activists who organized the January 25 protest used Facebook extensively to organize the event. They discovered that Facebook’s various features – particularly the ‘group’, to which individuals can be invited, and on whose ‘wall’ messages and updates can be posted – were well suited to movement organizing and protest planning. This section documents how activists’ use of this platform contributed to the success of January 25 primarily through two mechanisms: (1) movement recruitment, which helped to ensure the protest’s significant turnout and (2) protest planning and coordination, which gave the protest its scope and sense of simultaneity.

Recruiting protesters

One of the most impressive aspects of the Police Day protests was the number of people who participated in them: whereas in the past protests in Egypt had rarely exceeded 1,000, there were likely more than 30,000 people in the streets on 25 January 2011. This significant turnout can be at least partly attributed to years of painstaking work on the part of the protest organizers in building activist networks and social movements comprising tens of thousands of members. Much of this work, it turns out, was done online, and specifically through Facebook.

The Police Day protests were organized by a coalition of activist movements and the youth wings of several opposition political parties. The leaders of these various groups had become acquainted over the previous decade, as they had participated together in activism as university students and in the 2005 pro-democracy social movement Kefaya (Clarke Reference Clarke2011). The coalition comprised activists from a movement called the 6 April Youth, leaders from a campaign supporting a presidential bid for Mohamed al-Baradei (the former director of the International Atomic Energy Agency), youth representatives of two political parties, the Democratic Front Party and the Ghad Party, certain young members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and a leftist group called Youth for Justice and Freedom. The coalition also worked closely with the anonymous administrators of a Facebook group called ‘We Are All Khaled Said’, which was established in 2010 in response to the brutal murder by two policeman of a young Alexandrian native called Khaled Said. The incident had triggered an angry reaction from many middle-class Egyptians, and the Facebook page, which focused on grievances related to police abuse and impunity, had gained a considerable following. The Facebook page therefore gave the activists a sizable and receptive audience to which they could make their protest appeals. Moreover, a number of the movements and parties had been using Facebook for several years to recruit new members into their organizations, and by the beginning of 2011 some of them, particularly the 6 April Youth, could boast considerable followings.

The availability of a large and sympathetic audience in the form of the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ group was one of the most important differences between the January 25 event and previous efforts to stage anti-regime demonstrations in Egypt. The page had been established by two Egyptian youths – Wael Ghoneim and Abdel Rahman Mansour – who had connected via Google Chat in 2009.Footnote 14 Both were frequent and active users of Internet and social media platforms; Ghonim was a marketing manager at Google and Mansour had been blogging about Egyptian politics for several years. Mansour had also been a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and had joined the 6 April Youth in 2008, so he was well connected to activist circles in Cairo. The two partners first launched a Facebook page to support the candidacy of Mohamed el-Baradei for president (though they did not coordinate it directly with Baradei’s campaign). After Khaled Said was killed in June 2010, Ghonim launched the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ group to denounce the murder and police abuse in general; after several days he asked Mansour to help him administer it.Footnote 15

The membership of the page quickly grew. Many Egyptians were outraged by the event, and they responded positively to the page’s discourse, which eschewed overtly political messages and focused squarely on grievances related to police abuse and impunity. Mansour also explained that the type of people who joined the page tended to be Egyptians who had never been active in politics before:

I have some cousins and neighbors. They were sending me the link to the page, because they didn’t know I was the administrator. And in daily life they are really silent, and not very active in politics. It was like they have two faces […] Of course, some of [those who joined the page] were part of university movements, some of them were part of political parties, some of them were part of the 6 April movement, but the majority were middle class members who weren’t involved in politics.Footnote 16

By the end of 2010, the Facebook group had attracted hundreds of thousands of followers, far more than any other activist group or political party in Egypt.Footnote 17 At the end of December Ghonim connected with Ahmed Maher, a leader from the 6 April Youth, using the anonymous email address tied to the Facebook page. The two agreed to collaborate on planning a protest for 25 January 2011, in which they would use the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ group as the primary pool for protester recruitment.Footnote 18

Leaders of more conventional social movements and parties also used Facebook to recruit new members into their organizations and broaden their followings. The best example is the 6 April Youth, which boasted one of the largest followings among the groups that coordinated the protests. The movement was founded three years before January 2011; its name derives from a protest organized on 6 April 2008 by several youth activists in solidarity with a labor strike that was being held in the working-class town of Mahalla al-Kubra. In an interview, one of the activists who called for this protest described how she stumbled onto Facebook as a useful organizing tool:

Facebook was new; the first time that we used Facebook was in the 6 April Movement. I don’t know how I came up with this idea. I just found that the ‘groups’, and the ‘wall’, and the ‘discussion board’ were very helpful. And you can invite people and learn their opinions, and you can set up meetings online, as in the ‘threads’. So I found that it was a tool that helped me to gather people around one idea. I sent it to my friends. Then everyone went to the page and then sent it to their friends.Footnote 19

The 6 April 2008 protests were not a success; too few protesters showed up and they were quickly shut down by security forces. But the group that had organized them stayed in touch, and continued to invite people to their Facebook page, whose membership quickly grew into the thousands.Footnote 20 The leaders of the group explained that they used Facebook as the first point of outreach to new members.Footnote 21 They would invite new members and receive requests to join the group, which was an easy and efficient way to identify new followers and extend their reach.

Once they had built a strong online following, the movement leaders used the group’s membership as a base from which to plan physical face-to-face meetings and forums with supporters.Footnote 22 For example, one early leader in the movement explained how, shortly after the 6 April 2008 protest, the activists created an event in their Facebook group to organize a physical meeting at the Journalists’ Syndicate for individuals who wanted to get more involved in the movement:

The people who showed up were those who joined on Facebook. We didn’t know each other. It was the first time we had met each other. I was walking around asking people their names. We moved our movement from online to be here, to be in a physical place.Footnote 23

The leaders continued to hold similar meetings, and as they did they identified a core group of supporters that they came to trust. One of the co-founders explained that they thought of their movement in terms of concentric circles. The broadest group comprised those who had connected with them on Facebook; these were followers and supporters. But this group was too large and amorphous for the leaders to know everyone, and they assumed that it included regime informants and spies. They therefore created a second circle of more loyal followers, who they had come to know and trust. These individuals, who they identified through the face-to-face meetings that they held weekly around the country, formed the core of their organization and were crucial to orchestrating the January 25 protests. The activists established cells in neighborhoods and cities across the country, and they kept a database of names, locations and contact information for these core members.Footnote 24 At the very center of the circle were the movement’s founders and leaders, a group of approximately twenty individuals based in Cairo. In this way, the 6 April Youth leaders built a movement with both a broad, online network of followers and a well-defined organization of core members – both of which were primarily recruited through Facebook.

Among the youth groups that coordinated the January 25 protests, the 6 April Youth had perhaps been the most active in using Facebook to recruit members and followers, but other movements and parties used the platform for the same purposes as well. For example, one of the leaders of the Baradei campaign explained that they used Facebook in the same way as the 6 April Youth, identifying potential sympathizers and then holding physical events to collect signatures on a petition supporting Baradei’s run for office.Footnote 25 Similarly, leaders of the Democratic Front Party and the Ghad Party explained that they used Facebook to increase their followings and their reach.Footnote 26 When it came time to get the word out about the January 25 protests, all of these groups had Facebook followings in the thousands or tens of thousands to which they could disseminate their messages. They also had a core group of trusted conspirators on whom they could depend to launch protests around the country.

The importance of Facebook for recruiting Egyptians to participate in the January 25 protests can also be inferred from responses in the TDS survey and from accounts of individual protesters regarding where they heard about the event. In the TDS survey, almost half of respondents (48 per cent) said they received their first information about the event from Facebook, more than any other media or information source (the second was face-to-face interactions at 31 per cent). Similarly, numerous interviewees, including those from outside the core activist sector of Cairo-based middle-class youth, mentioned learning about the protests first through Facebook or being recruited into activist groups via Facebook. For example, a Salafi former police officer living in Cairo who participated in the first protest cited the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ Facebook group as the source of his information about the event.Footnote 27 A youth leader in the Muslim Brotherhood also noted hearing about the protests first on this group’s wall. Similarly, a trade union organizer from Suez said Facebook was his first source of information, and a leader in the independent tax collectors’ union cited the Internet as his and his colleagues’ source of information about the event.Footnote 28 Similar accounts emerged from those who had been recruited into activist groups like the 6 April Youth. For example, three young men from Suez explained in an interview that, although they had never met any 6 April leaders and had never been to any meetings, they had joined the Facebook group in 2010 and had been able to closely follow and participate in the movement’s campaigns, including the January 25 protests. Eventually they were asked to serve as the movement’s representatives in Suez, coordinating local youth activism in the city.Footnote 29 All of these individuals were outside the core activist circles based in Cairo, and many of them, like the young men in Suez, had little experience with politics. Their participation in the January 25 protests was directly facilitated by their recruitment into activist movements and networks via Facebook.

Protest planning and coordination

A second dimension of the Police Day protests’ success was their remarkable scope and breadth. At the same time, in squares and cities across the country, demonstrations erupted making the same demands and chanting the same slogans. This simultaneity gave the impression of a truly national event, which increased the protests’ visual and symbolic impact. It also made them harder to contain, as security forces were forced to deploy troops to multiple sites. The striking coordination of these protests was also enabled by activists’ use of Facebook, which became the primary information hub on which they posted details about the event.

The TDS survey provides initial evidence of Facebook’s important coordinating role in these protests. Survey respondents were asked ‘what type of relevant information did you receive’ via various media sources, and then provided with seven possible categories: none, news and updates, coordination, documentation like pictures and videos, opinions and slogans, jokes and other. Of all the media sources that the survey examined, Facebook was used for receiving information on coordination more than any other source: 45 per cent of Facebook users reported receiving coordination information through the platform. By comparison, only 30 per cent of mobile phone users received coordination information through that channel, and only 28 per cent of Twitter users.

Interviews also corroborated the importance of Facebook for coordination, and provided additional specifics regarding how the platform was used to plan for the protests. After creating the Facebook event page calling for a protest on Police Day, the 6 April Youth leaders and ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ administrators began discussing the logistics of the event. They formed a thirty-member planning committee comprising members of each participating group, though the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ administrators never attended these meetings in person, preferring to remain anonymous and communicate with the other organizers only via Facebook and Google Chat. The planning committee divided into subcommittees responsible for different activities: picking protest locations, reaching out to other organizations, developing slogans, publishing information on the Internet and printing pamphlets.Footnote 30 The group met physically at various secret locations around Cairo. One member also visited several cells in other cities to encourage them to form similar planning committees and to ensure they were following a roughly similar routine.Footnote 31 Eventually they settled on the following general framework for the day: the protests would begin at 2PM in four locations around Cairo and in six cities where the activists believed they had a strong presence. Supporters in other locations would be encouraged to attend the protests closest to them. In addition, the activists would send some of their closest supporters to begin a ‘secret protest’, which would not be publicized, two hours earlier; this would allow them to gather followers and momentum before the main demonstrations kicked off, and would allow them to confuse and divert the security forces. They set up a control room in the offices of a friendly non-governmental organization, where several leaders would remain throughout the day to answer calls from those seeking information about the protests and to post updates to Twitter and the Facebook page.Footnote 32

The primary way that activists disseminated information about these protest details was via Facebook, using their own groups’ pages to send the details to their members and followers.Footnote 33 The most important of these pages, due to the sheer number of followers that it had collected, was the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ group. At 2:53PM on January 24, the activists posted the details of their protest plans on an event page connected to the group titled ‘Details for January 25 Protest’, which is reproduced in full in Appendix C.Footnote 34 The page begins with a description of who the activists are and why they are protesting on January 25. It then lists their demands, which include alleviating poverty, canceling Egypt’s long-running state of emergency, firing the Interior Minister Habib al-Adly and limiting presidential tenure to two terms.Footnote 35 The next section lists the locations where the protests would begin: in Cairo at Shubra circle, at Matareyya circle, in front of Cairo University, and on the major Mohandiseen thoroughfare Arab League Street, and outside of Cairo at specific locations in Alexandria, Ismailia, Fayoum, Mahalla al-Kubra, Tanta and Sohag. The page then lists some general principles for how to protest and remain safe during the event, and enumerates the various chants and slogans that protesters should use. It then lists a series of phone numbers: first those of a lawyers’ group that had committed to represent protesters, and then for contacts in each city (including the control room in Cairo) who would be available to provide logistical details and support.Footnote 36 The page concludes with a list of the groups sponsoring and supporting the event.

The event itself began largely as planned, suggesting that those attending the protests were indeed getting their information from this Facebook page. The activists staged their secret protest beginning at noon, marching through poorer neighborhoods of Cairo and collecting followers. Though the activists had called for protests to begin at 2PM at each of the designated locations, participants began arriving considerably earlier, and so they were already well underway by the time these activists arrived. One organizer from the Baradei campaign described the scene he discovered at one of these sites:

We had mentioned that the demonstration would start at 2PM, and don’t do anything before. But people came early, people from Facebook. Some of the people were from our groups, but most of them I didn’t know. They just followed the Facebook announcement. There were maybe 2,000 to 4,000 who were there before 2 o’clock. And once we found these huge numbers of people we started demonstrating.Footnote 37

Another protester, a 6 April Youth member from the small Nile Delta city of Damanhour, followed the instructions on the Facebook page and went to nearby Alexandria to protest. He described how he and six other friends found a similar scene at one of the designated protest sites there, in front of the Sidi Gaber train station:

We marched through small neighborhoods, collecting numbers. Then we moved to Sidi Gaber station; that was the plan. Other groups were to go to Egypt Station [the other protest site]. These places were published on Facebook. We went there in big numbers and found people from all over the place.Footnote 38

The fact that protesters like this interviewee followed the instructions laid out on Facebook (that is, going to Alexandria to protest rather than staying in his hometown), and the fact that in these various cities the protests started at roughly the time and in the places enumerated on the page, points to the importance of Facebook for facilitating the national scope of the event. Indeed, it appears that by publishing their plans on Facebook activists were able to organize a protest with little precedent in the recent past in Egypt: a national anti-regime demonstration drawing participation from across the country.

Twitter: Live Updating about the Protests

A final striking feature of the January 25 protests was their seemingly leaderless quality. Although, as noted above, the planning on Facebook provided a framework for the protests and ensured they would start at roughly the same time and chant roughly the same slogans, much of what unfolded after the demonstrations began was not pre-planned, for example the apparently spontaneous convergence of protesters in Cairo on Tahrir Square. This spontaneity added to the protest’s sense of authenticity. Although many onlookers knew that youth groups had called for the event, the way in which the demonstrations swelled and moved made it seem like a genuinely leaderless movement, guided to and steered by the spontaneous decisions of Egyptian citizens who felt they had the agency to contribute to and influence its movements. What enabled this seemingly leaderless coordination of action? How did activists across the city and country know what others were doing through the heat of the protests?

Although Twitter was a far less widely used platform than Facebook during the revolution, its functionality proved well suited to one crucial activity that helped enable these spontaneous movements: providing real-time, live information about events during the day, including when and where protests were taking place, where they were headed, and where resistance from security forces was particularly strong. Twitter penetration in Egypt at the time of the revolution was relatively low, and only 12.5 per cent of respondents in the TDS survey reported using it during the revolution. But usage was higher among first movers (23 per cent), and several interviewees talked about its importance for providing updates about what was happening during the Police Day protests.Footnote 39 Moreover, when answering the question noted above about the type of information received through a platform, Twitter users reported receiving information about ‘news and updates’ more than any other topic (69 per cent). And a striking 93 per cent of first-mover Twitter users received news and updates through the platform.

Just as Facebook’s properties proved well-suited to certain mobilizational tasks, so too did Twitter offer features that made it an effective tool for sending and receiving live updates about the protests. First, information sent via Twitter is disseminated to followers instantaneously, making it a useful tool for protesters demanding real-time information. Secondly, Twitter’s ‘retweet’ feature allows information to be rapidly passed along from each user to his or her followers and thus spread exponentially.Footnote 40 Thirdly, Twitter’s hashtag feature allows users to tag their tweets with short text strings, thus enabling users to reach a much broader audience of individuals seeking information about that tag. Popular hashtags become ‘trending topics’, which are seen by every Twitter user in the locations where they are popular.Footnote 41 Hashtags were utilized to share information regarding specific locations during the protests, or to maintain conversations about certain topics.

On January 25 these features made Twitter a useful tool for activists, who had few other means (besides calling and texting friends) of knowing what was occurring in other parts of Cairo or Egypt. It allowed them to learn about where the major protests were occurring, and, more importantly, where they were heading as they left the squares where they had started and began marching. For example, one activist in the Revolutionary Socialist group described how he decided to go to a particular location on January 25. He had missed the start of the protests, and he wanted to join in wherever they were biggest. He was following the event on Twitter, and learned that the protests were particularly strong in the Bulaq neighborhood, which is where he went to join them.Footnote 42 Another activist explained that Twitter helped alert him to events in more peripheral cities, like Suez, where media coverage was low and where the security reaction on January 25 was particularly violent.Footnote 43 According to Abdel Rahman Mansour, ‘Twitter played a main role in publicizing the news and information during the event – to know [about] the tactics of the police and to send news.’Footnote 44

Among the most symbolically powerful events on January 25 was the convergence of marches from around Cairo on Tahrir Square, at the center of the city. By late afternoon, protesters from at least four different sites around the city had marched to the square. This tactic had not been planned by the organizers of the event; tellingly, Tahrir appears nowhere on the Facebook page laying out the details of the protest.Footnote 45 One activist, who was at a protest in front of the High Court, near Tahrir, on January 25 described how this spontaneous turn of events occurred:

On this day [January 25] we didn’t know we were going to Tahrir with our demonstration. Because Tahrir is a red line – all the police and security say that Tahrir is a red line. But then someone said ‘go to Tahrir’. So we went.Footnote 46

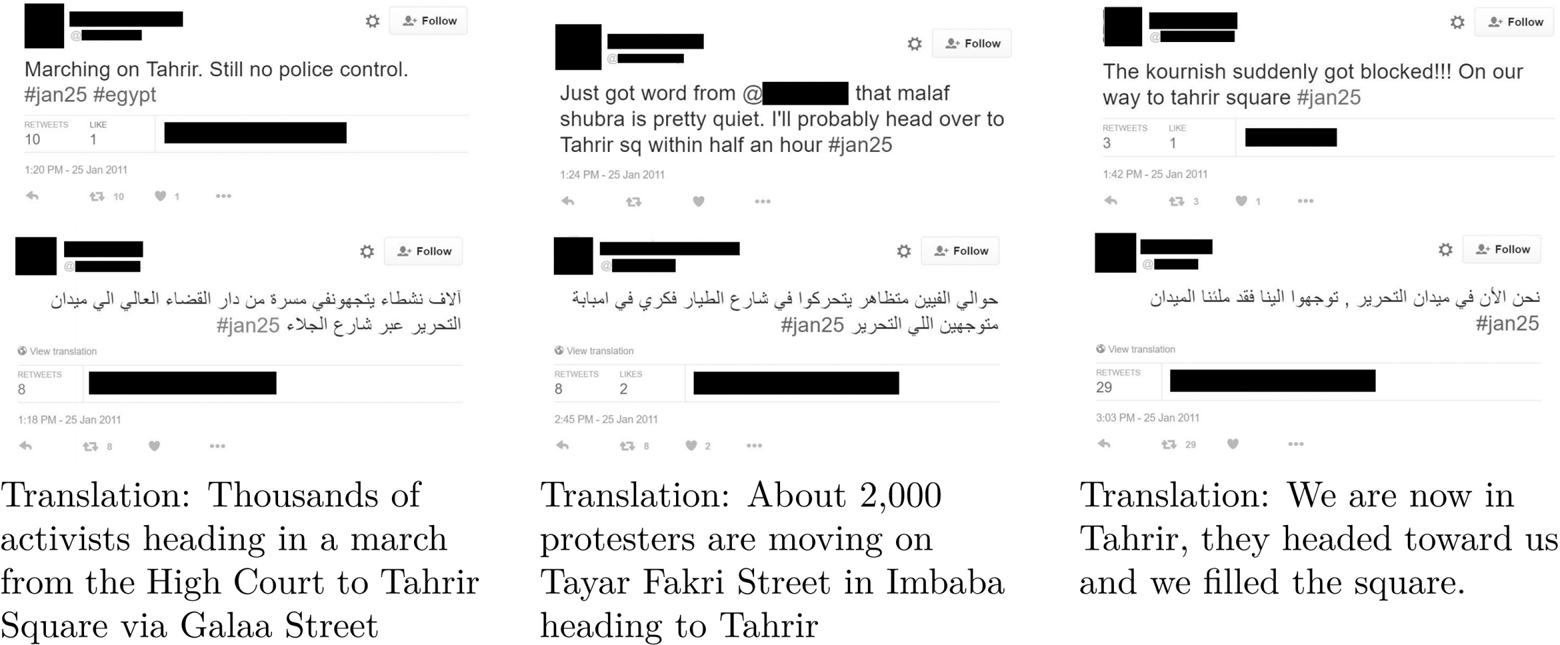

One of the primary means by which protesters learned of the marches to Tahrir was by Twitter, and many of the tweets from this period mention the convergence on Tahrir. A sample of six of these tweets is reproduced in Figure 1 – they mention variously that protesters are marching to Tahrir from various locations (the High Court, Imbaba), that the police presence is low and that protesters have taken the square.

Figure 1 Sample of tweets reporting movement towards Tahrir Square.

The timing of when these types of tweets appear points to the spontaneity with which the decision to head to Tahrir was made. As noted, the original protest plans did not say anything about Tahrir, and there are therefore few mentions of the square in the hours preceding the start of the protest. Before 1 PM there were only thirty-five English tweets and thirty-five Arabic tweets based in Egypt that mention Tahrir, corresponding to 2 per cent of Egypt-based tweets in our sample in that time frame, most of which were citizens reporting about the police presence in the square. But after 1 PM the number of tweets mentioning Tahrir escalated – 220 in English and 467 in Arabic, or 12 per cent of our sample – as protesters began noting the movement toward the square and calling for others to join.

We can also understand the effect of these tweets by studying the trajectory of one such tweet as it is retweeted by subsequent users. The first tweet on January 25 noting the movement of protesters toward Tahrir is reproduced on the bottom left of Figure 1. It noted that activists were ‘heading in a march from the High Court to Tahrir Square via Galaa Street’. It was sent at 1:18PM on January 25 by a journalist with al-Araby newspaper. It was retweeted less than a minute later at 1:19PM by a user describing herself as a medical student from the city of Tanta. The next retweet, also at 1:19PM, was from a user who describes herself as a community editor and social media specialist based in Cairo. It was then retweeted again at 1:23PM and 1:24PM, and the final retweet was at 1:42PM by a self-described ‘entrepreneur / architect / designer’ from Cairo. As the trajectory of this one tweet demonstrates, on January 25 users passed on information about protest movements via Twitter almost in real time, facilitating the simultaneous coordination of action.

A more systematic way of determining how first movers used Twitter on January 25 is to study the frequency and content of the tweets themselves. To do so we scraped and analyzed all the tweets (and retweets) associated with the #jan25 hashtag from 14 January to 16 March. The tweets were downloaded with Twitter’s API using the IDs collected by Deen Freelon.Footnote 47 The original file contains 671,417 tweet IDs; after removing duplicates and posts that have been removed by users, we are left with a total of 523,742 tweets in our sample, including original tweets and retweets.Footnote 48 We then restricted our sample to include only tweets from users based in Egypt, who we identified with the information listed in their profiles. To identify locations of tweets we used a string-matching method using a dictionary of place names that we developed based on common spellings (and misspellings) of Egypt, its nicknames, and the names of its largest cities (in English and Arabic) (Hecht et al. Reference Hecht2011; Leetaru et al. Reference Leetaru2013). This resulted in 101,778 tweets and retweets by users who listed Egypt as their location.Footnote 49

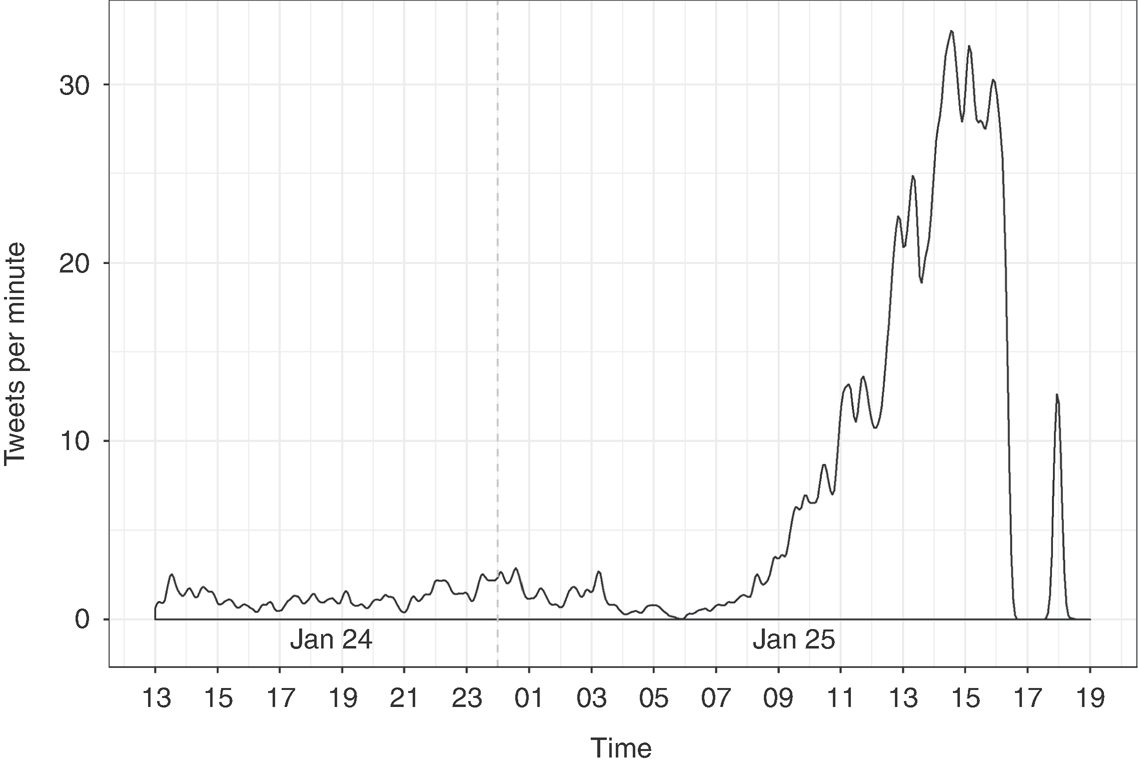

In Figure 2 we plot the density of tweets from Egypt starting from the afternoon of January 24 until Twitter was shut down around 7PM on January 25. Twitter activity increased steadily throughout January 25, beginning at 7AM. It peaked around 3PM, at which point protests around the country were well underway. The density of tweets then declined sharply, beginning around 4PM, likely due to the first of several service interruptions. Twitter then became the first social media site to be fully blocked by the government. Between 4:30PM and 5:45PM there are no Egypt-based tweets in the data set, and though service seems to have returned briefly after that, the last tweet from Cairo was sent at 6:23PM, moments before access was shut off completely. Although the platform became available for brief spells over the subsequent days, for most of the next two weeks access to Twitter was extremely limited in Egypt.

Figure 2 Twitter activity density, 24 January (1PM) to January 25 (7PM).

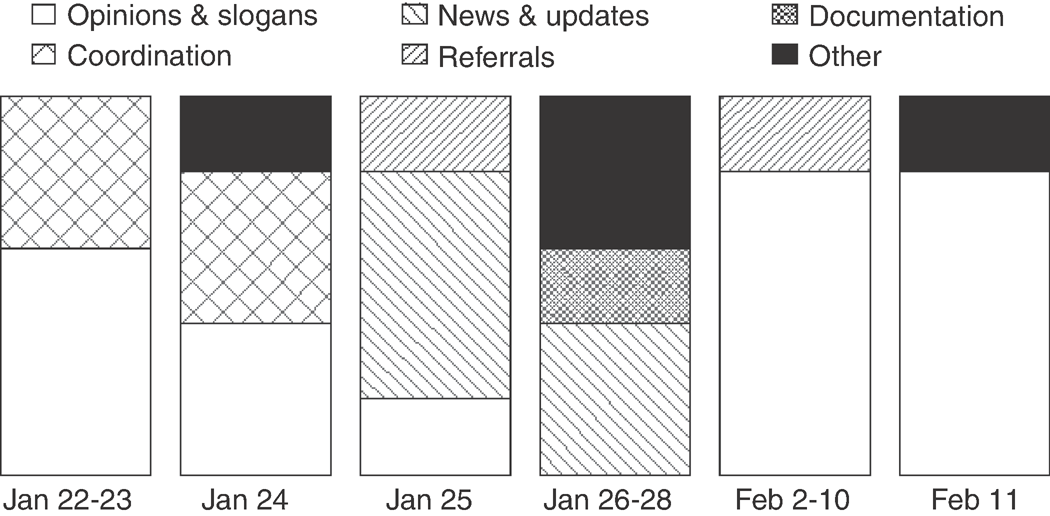

Finally, we analyze the content of the tweets themselves, using the topicmodels package in R, to discern if there are any meaningful shifts in the types of topics being discussed on Twitter during the course of the revolution (Grün and Hornik Reference Grün and Hornik2011). We divided our data set into six different periods, which track the different stages of the revolution itself: January 22 to January 23 (the run-up to the Police Day protests), January 24 (the day before the protests), January 25, January 26 to January 28 (the period leading up to and including the ‘Friday of Anger’ on January 28), February 2 to February 10 (the days of the Tahrir Square sit-in), and February 11 (the last day of the revolution).Footnote 50 Topic analysis of the Egypt-based tweets and retweets across these periods demonstrates telling shifts in the types of topics being discussed on the platform. We manually coded topics according to six categories, the majority of which we draw from the information categories used in the TDS survey (to facilitate comparison): news and updates, coordination, opinions and slogans, documentation, referrals and indeterminate.Footnote 51 The results of this analysis are plotted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Distribution of topics on Twitter during the Egyptian uprising.

Not surprisingly, the first two periods, which occur before January 25, have a higher proportion of topics categorized as ‘coordination’ (two out of five in each period), as well as several with ‘opinions and slogans’, many of which include terms referring to Khaled Said, the police and security forces, or the Tunisian uprising. The ‘opinion and slogans’ topic also dominates in later periods, but this time the content of these slogans is more focused on the Mubarak regime, the army and the demands of the revolution. The middle two periods, particularly January 25, are the only ones with a high occurrence of topics coded ‘news and updates’. On January 25, three out of five topics are about news and updates, and in the January 26 to January 28 period two topics are. On January 25 these topics seem to be primarily focused on protest locations, and reflect similar types of content to those in the tweets cited above as examples. For example, one topic includes the words (in Arabic) ‘Tahrir’, ‘square’, ‘street’, ‘security’, ‘demonstrators’, ‘demonstrator’, ‘league’ and ‘nations’ (the latter two referring to the protest site on Arab League Street). A second topic includes the words ‘Cairo’, ‘now’, ‘Tahrir’, ‘street’, ‘police’, ‘protest’ and ‘today’. And a third topic includes the words (in Arabic) ‘house’ (referring to the House of Justice, or the High Court, another protest site), ‘in front of’, ‘police’, ‘security’ and ‘now’.

The content analysis and the density plot, together with the interview and survey data, collectively indicate that Twitter was used on January 25 to disseminate live information about the protests. The platform’s attributes proved to be well suited to these purposes. Moreover, the use of Twitter in this way seems to have facilitated horizontal communication between protesters on the day itself, allowing them to synchronize and coordinate their actions in real time, despite being spread out across the city and country. Thus Twitter, although less important overall than Facebook, also seems to have enabled the successful day one protests of January 25, through the mechanism of live updating.

Conclusion

The analysis above has demonstrated the importance of two social media platforms – Facebook and Twitter – for facilitating a successful first protest in Egypt on 25 January 2011. This protest provided the initial momentum for the subsequent 17 days of mobilization that brought about the end of Mubarak’s rule. It served as an important signal to sympathetic Egyptians, watching warily from the fences, that a successful revolution in Egypt might be possible and convinced them to participate in the subsequent January 28 Friday of Anger protest, which broke the back of Mubarak’s security forces. In this article, we have shown how three mechanisms – movement recruitment, protest planning and coordination, and live updating – connected the social media platforms Facebook and Twitter to the success of this initial protest across three dimensions. Movement recruitment through Facebook helped bring about the protest’s significant size, the planning enabled by Facebook helped achieve its broad scope, and live updating on Twitter facilitated seemingly leaderless protester coordination and movement.

Our argument has been deliberately narrow; we do not claim to have captured all the ways in which social media mattered during the Egyptian uprising, or indeed in the many other instances of collective action in which it may have played a role. For example, we do not analyze the potential affective or discursive effects of social media, like how Twitter or Facebook created an ‘atmosphere of change’ or a ‘sense of possibility’ that motivated and encouraged revolutionaries, or how its usage helped to produce a particularly resonant discursive repertoire in which to couch claims and demands. These dynamics may well have been at play in this and other instances of mobilization, but, lacking the data to convincingly demonstrate their impact, we leave them for other scholars to evaluate and analyze. Instead, we have tried to empirically demonstrate, using a variety of data sources, the role of social media usage in helping to bring about one discrete mobilizational outcome.

Though our claims are modest, we hope to have made two contributions. First, we have argued that social media did matter during the Egyptian uprising, albeit in perhaps a more limited way than many initial accounts claimed. In this debate, we therefore fall somewhere in between Philip Howard and co-authors and Marc Lynch (Howard et al. Reference Howard2011; Lynch Reference Lynch2011). Our position also maps onto the broader debate about the Internet’s transformative potential for mobilization. The evidence we have presented suggests that although key Internet platforms have the potential to facilitate certain aspects of mobilization – like staging an initial successful protest – these platforms did not, at least in this case, fundamentally transform the revolution’s dynamics of collective action. When the Mubarak regime shut down these social media platforms, and then the Internet entirely, the revolution did not come to an end; rather, activists relied on tried and true tactics of mobilization that have been used for generations to maintain the uprising’s momentum (Hassanpour Reference Hassanpour2014). Nor can we say that a successful day one protest might not have been staged through other means had social media not been available – an impossible counterfactual to empirically assess.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, we hope that our study will serve as an example of how scholars might move forward in the still nascent subfield of ‘politics and the Internet’. As often occurs in any burgeoning field, much of the early research on this topic has focused on building macro theory and making broad claims, often at the expense of careful empirical analysis. We believe it is time for scholars to narrow their focus, and to make more limited but also more empirically grounded arguments about the effect of specific facets of the Internet on discrete political or social outcomes. We also believe that a focus on mechanisms can help elucidate these causal relationships more clearly. With more research of this type we believe scholars can make significant contributions in demonstrating the many important ways in which new technology is changing dynamics of mobilization and political engagement.

Supplementary Material

Data replication sets can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7910/DVN/S17DDJ and online appendices are at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000194. Arab Barometer data employed in the analysis can be downloaded from http://www.arabbarometer.org/instruments-and-data-files. The Twitter data was collected using the data and instructions on http://dfreelon.org/2012/02/11/arab-spring-twitter-data-now-available-sort-of/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mark Beissinger, John Chambers, Kosuke Imai, Manal Jamal, Arang Keshavarzian, Daniel Tavana, Yang-Yang Zhou, the editors at BJPolS, and four anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article.