Introduction

Academic research on human-animal interactions has only recently gained momentum. Cohen (Reference Cohen2009) attributes this delay to the widespread belief that a fundamental divide exists between nature and culture, separating human society from the animal kingdom. However, this assumption has changed as modern natural sciences have shown the continuities between animal and human development. Concurrently, social scientists have destabilized the culture-nature divide by recognizing many nonhuman animals existing in an overlapping ‘border zone’ between nature and culture (Ingold Reference Ingold, Manning and Serpell2002). These advancements have emphasized the importance of studying multispecies engagements in today’s world, including in our home discipline of (socio)linguistics.

Tourism is arguably one primary domain that offers humans the opportunity to engage with the more-than-human world. Nonhuman animals are a significant component of tourist attractions and serve as the principal icons of some destinations (Cohen Reference Cohen2009; Lamb Reference Lamb2024a). Wildlife tourism in particular has grown into a major global industry, allowing us to observe how modern urbanites interact with wildlife in its natural and contrived settings. A notable number of studies have emerged on human engagement with various species of wild animals: with chimpanzees in Spain (Alcayna-Stevens Reference Alcayna-Stevens2008), hyenas in Ethiopia (Baynes-Rock Reference Baynes-Rock2013), sharks in Australia (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018), elephants in Nepal (Szydlowski Reference Szydlowski2024), and sea turtles in Hawai‘i (Lamb Reference Lamb2024a).

The wildlife tourism industry is uniquely positioned between two seemingly contrasting ideologies: one that views nature as a commodified spectacle, influenced by neoliberal logics, portraying humans as spectators to the remarkable displays of nonhuman animals; and the other that regards tourism as a strategic financial instrument for conserving wildlife itself (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2015). Studies critical of the use of the wildlife in tourism suggest that the phenomenon operates within an anthropogenic framework where human intervention reshapes natural environments through urbanization, deforestation, and habitat encroachment. Such engagement with the nature reproduces colonial legacies and capitalist expansion by exploiting indigenous lands and ecosystems, often reconfiguring these natural landscapes for economic gain (see Smith’s introduction in this issue). The same dynamic persists in wildlife tourism, where global capitalist interests commodify nature and transform wildlife into a resource to be consumed by tourists. In many marginalized communities, encounters with the wildlife have been deployed as part of the country’s economic development strategy (Uddhamar & Ghosh Reference Uddhamar and Ghosh2009), including an approach to secure funding and financial support. These conditions demonstrate a neoliberal mode of wildlife conservation (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2015) in the Anthropocene.

Although research on tourist-wildlife encounters is expanding, there remains limited engagement with these contexts through a sociolinguistic lens. I posit that sociolinguistic concepts and tools are well-positioned to understand the neoliberal mode of wildlife conservation embedded in tourism economies. The present study attends to this concern by providing an empirical case of human-elephant engagement at Sauraha, a suburban tourist town located at the eastern edge of the Chitwan National Park (CNP), Nepal. The aim is to examine how elephant tourism reproduces the modern binary between nature and culture, and what economic and ideological purposes this divide continues to serve in the context of the Anthropocene. In doing so, it attends to two key questions: (a) How do semiotic interventions, such as sculptures, signs, and other visual symbols, construct value around elephants and nature? and (b) In what ways are elephants commodified through their symbolic and corporeal encounters in the landscape? Using ethnography, I collected photographs of semiotic signs, material artifacts, and media interviews with tourism stakeholders in Sauraha. Using the conceptual heuristic of sites of engagement (Scollon & Scollon Reference Scollon2003; Jones Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014), I demonstrate that multispecies engagement through verbal inscriptions, visual semiotics, material artifacts, and environmental elements constitutes a complex nexus of practice that gives rise to contested ideologies that co-exist side-by-side, often shaped by the neoliberal economy, local cultural tradition, and wildlife conservation discourse. I find that the awkward simultaneity of these multispecies encounters appears to promote responsible tourism narratives, while obscuring the precarious conditions of elephants, erasing the labor of mahouts, and overlooking affective practices that gesture toward more reciprocal interspecies relationships.

Elephants in wildlife tourism

Research shows that tourists’ appeal to elephants oscillates between two distinct experiences: the fascination with encountering a wild animal in its natural habitat and the amusement derived from observing their human-like behaviors in contrived settings (Mullin Reference Mullin1999; Cohen Reference Cohen2009). These dynamics manifest differently across countries. In the East African nations of Kenya and Tanzania, elephant tourism centers on observing elephants in the wild through non-intrusive safari experiences, whereas in South Asia including Nepal and India, the experience emphasizes embodied encounters and curated performances (Uddhamar & Ghosh Reference Uddhamar and Ghosh2009). What remains consistent across these contexts is the way elephant tourism is positioned as a dual vehicle for promoting wildlife conservation and economic development (see Laws, Koldowski, & Scott Reference Laws, Koldowski, Scott, Jafari and Xiao2024 for a review).

In the case of Nepal, private ownership of elephants for tourism purposes commenced around the 1960s, primarily catering to tourist-driven safari activities. This marked a significant development in the burgeoning tourism sector of southern lowlands, notably at Chitwan National Park, complementing the already popular mountaineering expeditions in the northern regions. Over the subsequent six decades, there was a notable expansion in the number of hotels and infrastructure centered around elephant-based tourism, peaking at nearly eighty privately owned elephants by 2020. Presently, elephant-based tourism in CNP encompasses four main categories: rides, walks, baths, and festivals (Jacoves Reference Jacoves2023), and Sauraha is an urbanized hub to offer those infrastructure services.

In Nepal, elephants are revered both for their economic potential but also for their cultural significance. Locke (Reference Locke, Locke and Buckingham2016) highlights the historical interconnectedness between elephants and humans in the region, where they have symbolized power and prestige, been exchanged for profit, and utilized in biodiversity conservation and wildlife tourism. Their territories at CNP have steadily shrunk since the 1930s due to habitat fragmentation, ivory poaching, and escalating human-elephant conflicts (Ram et al. Reference Ram, Yadav, Subedi, Pandav, Mondol, Khanal, Kharal, Acharya, Dhakal, Acharya, Baral, Dahal, Mishra, Naha, Pradhan, Natarajan and Lamihhane2022). The emergence of elephant tourism in the 1980s in particular brought about significant changes, impacting not only the elephants but also the local community, including the mahouts, whose roles and livelihoods have evolved in tandem with the elephants (Jacoves Reference Jacoves2023). The park has made advancements in recent years leading the captive elephant population to increase to about one hundred and fifty (Szydlowski Reference Szydlowski2024).

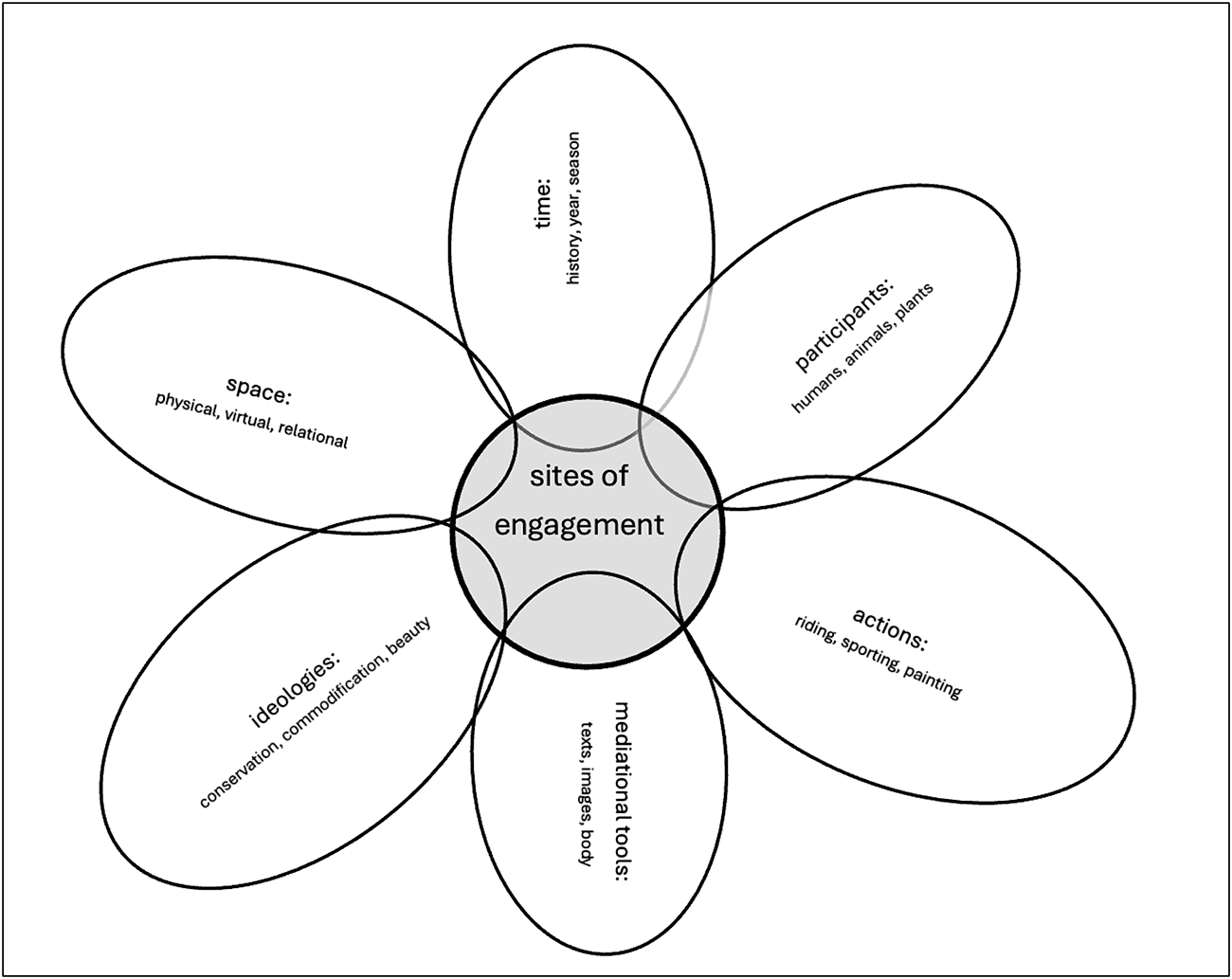

These elephant-human engagements in CNP are notable precisely due to what Lorimer (Reference Lorimer2015) calls their ‘encounter value’ to describe the worth derived from multispecies interactions (e.g. rides shown in Figure 1). Encounter value, much like charisma, is a relational concept that pertains to both the properties of the organism being encountered and the affective logic that shapes any encounter and determines its value. The demand for these encounters is materially transforming the reproductive ecologies of wild spaces, including the material and the semiotic affordances that shape a variety of tourism activities in Sauraha.

Figure 1. Elephant tourism in CNP (photo: author).

Neoliberal conservation

Neoliberal conservation reimagines nature as something that can, and should, be saved through markets. This approach, which took root in the 1980s and surged with global enthusiasm for ‘green growth’, positions capitalism not as a threat to the environment but as its savior. Conservation is recast through tools like ecotourism, payments for ecosystem services, and biodiversity offsets, turning animals and entire ecosystems into commodities that generate revenue. As Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2020) explains, this strategy arose from a desire to align conservation with development agendas and corporate funding streams, with ecotourism often leading the charge. By commodifying ecosystem services and promoting nature as natural capital, neoliberal conservation reshapes the biophysical world into an asset class for investors. However, Allen (Reference Allen2018), taking the case of Costa Rica, warns that this framing prioritizes short-term monetary incentives and reduces diverse human-nature relationships into exchange values which can undermine ecological sustainability and fail to account for the incommensurable values that characterize human-nature relationships. What appears as a win-win solution often masks deep social and ecological contradictions.

Tourism is one of the most visible instruments of neoliberal conservation, celebrated for offering a harmonious blend of economic growth and environmental stewardship (Uddhamar & Ghosh Reference Uddhamar and Ghosh2009). Yet, this model is steeped in contradictions. Nature-based tourism turns ecological crisis into profit-making opportunities, rebranding degraded or threatened landscapes as spaces of emotional and aesthetic consumption. Duffy (Reference Duffy2015:529) argues ‘nature-based tourism allows neoliberalism to turn the very crises it has created into new sources of accumulation’ by commodifying not just animals and habitats, but also the emotional experience of close interactions. Igoe & Brockington (Reference Igoe and Brockington2007:434) likewise highlight the seductive, yet misleading, fantasy of these models, in which ‘it is possible to “eat one’s conservation cake and have development dessert too”’, while on the ground they document patterns of coercion, including threats to communities near wildlife areas. This way, prevalent discourses of conservation, such as ethical elephant encounters, often overlook historical context, unequal political economies, and consumers’ roles in perpetuating conservation issues. These discourses craft lucrative tourist encounters with ‘charismatic species’ creating affective connections between humans and wildlife (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2015). Affective images of these species then become commodities, promoting a superficial and inadequate approach to understanding and addressing the intricate social and ecological dimensions of conservation.

Sociolinguistic and discourse analytic studies show how language and visual tools commodify nature in ecotourism by branding landscapes as authentic and aestheticized experiences for consumption. From Instagram’s ‘promontory witness’ motif (Smith Reference Smith2019) to the Faroe Islands’ branding of raw weather (Nilsson Reference Nilsson2024) and Alsace’s nature-centered discourse (Wilson Reference Wilson2022), studies show how place, identity, and nature are stylized for market appeal. Lamb’s (Reference Lamb2024a) research on sea turtles in Hawaiʻi illustrates the tensions of neoliberal conservation by closely analyzing the discourse and interactional practices of volunteers, tourists, and conservation officials at Laniākea Beach. Through sociolinguistic and discourse analysis, Lamb shows how volunteers like the honu guardians attempt to mediate tourist behavior using language ideologies rooted in education, politeness, and the ‘Spirit of Aloha’ (2024a:13). Tourists, by contrast, often enact a discourse of entitlement, expecting close, physical encounters with turtles framed through social media imagery and commercial spectacle. Lamb captures these tensions by illustrating how neoliberal conservation transforms sea turtles into ‘spectacular’ commodities, while the labor of care is linguistically and socially distributed across uneven relations of power.

Eco-semiotic landscapes

Research on linguistic and semiotic landscapes in sociolinguistics and related fields has largely focused on the built environment. While studies engaging with the natural world and more-than-human spaces are beginning to emerge (see Lamb & Sharma Reference Lamb, Sharma, Blackwood, Tufi and Amos2024 for a review), examinations from a political-economic perspective remain notably scarce. This gap is significant, as a political-economic lens reveals how neoliberal conservation often commodifies nature through tourism-driven interventions that are reliant on semiotic and linguistic practices. These placemaking practices function within the political economy of tourism experience by turning signs, symbols, and objects embedded in the landscape into sources of economic value (Jaworski Reference Jaworski2015). As Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2024) demonstrates in his study of Miajadas, Spain—self-declared Tomato Capital of Europe—the town deploys monumental sculptures, multimodal signage, and social media to mediatize and remediate its identity by transforming tomatoes into spectacles that represent both local pride and economic ambition.

Although not always explicitly focused on the political economy of signs, research on linguistic and semiotic landscapes of the natural environment offers important insights into the multimodal and semiotic dimensions of spatial configurations shaped by the nature and material infrastructure. Despite the recent surge in interest, research has predominantly focused on human-centric cultural artifacts within the environment, heavily influenced by Western reading culture, sign creation, and consumption (Banda & Jimaima Reference Banda and Jimaima2015). Such a narrowed focus is problematic because the semiotic dynamics of natural landscapes, including wildlife, can contribute to a fundamentally different semiotic production and consumption process. Examining signage in interpretive paths in Tampa Mountain in Romania and nature walks in Lincoln Park in the US, Soica & Metro-Roland (Reference Soica and Metro-Roland2022) advocate for understanding the indexical connection between multimodal texts and natural environment objects. By considering natural processes like seasonal species changes, the authors argue, researchers can gain insights that extend beyond human culture and contribute to a more holistic semantic interpretation of nature. Likewise, Banda & Jimaima (Reference Banda and Jimaima2015) explore sign- and place-making in rural communities of Zambia and illustrate how cultural artifacts such as unwritten signs and natural objects, such as trees and hills, are part of everyday acts of landscaping.

Further, studying the commodified production of multispecies encounters in wildlife spaces, as this study does, requires attention to actors and elements that extend beyond the linguistic and the human. The semiotic co-production of ecotourism spaces recognizes that humans are not the sole agents shaping the world; nonhuman species also play meaningful roles in shaping environments, cultures, and societies (Tsing Reference Tsing, Omura, Otsuki, Satsuka and Morita2019). Lamb (Reference Lamb2024b) illustrates this through his analysis of the Hawaiian monk seal conservation context, where humans and animals are mutually entangled in shaping the spatial and affective contours of conservation spaces. He documents how monk seals’ physical presence and movement co-construct conservation sites through affective responses, public discourse, and signage. These multispecies entanglements, he argues, are central to understanding how conservation is practiced and negotiated on the ground, not only through policies, but through the lived and communicative relations between species.

Taking inspiration from semiotic and multispecies landscape studies on the natural environment, I propose that sociolinguists can advance productive conceptual and empirical moves to better align wildlife research spatially. This shift broadens the scope of semiotic landscape research to include environmental meanings alongside cultural and social ones, which can foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of nature while critically examining human engagement with it. In line with this, the present study emphasizes the importance of recognizing the shared resources in multispecies entanglements in the co-existing world by demonstrating how such entanglements create an empirical opportunity for researchers to critically engage in dialogs about elephant conservation efforts in the neoliberal world.

Analytical framework: sites of engagement

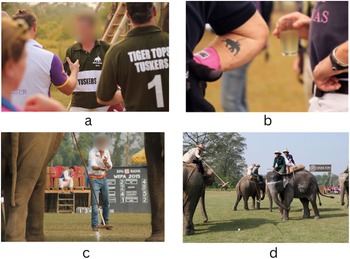

Drawing on Jones (Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014) and Scollon & Scollon (Reference Scollon2003), I employ the notion of sites of engagement as an analytical heuristic to consider the discursive, semiotic, and material dimensions of those moments in time and points in space where actions take place. Sites of engagement, as Scollon (Reference Scollon2001:4) notes, are ‘a window that is opened up through the intersection of social practices and mediational means (cultural tools) that make that action the focal point of attention of the relevant participants’. Jones (Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014) argues that any site of engagement is considered a nexus where bodies, objects, texts, and social practices come together, each with their own histories—the trajectories along which they traveled to reach this moment. This way, we can understand the consequences of this nexus on the agency of those involved in the action, distributed among multiple species, spaces, objects, texts, and social practices (see also Lamb & Sharma Reference Lamb, Sharma, Blackwood, Tufi and Amos2024), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sites of multispecies engagement, adapted from Jones (Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014), Scollon (Reference Scollon2001), and Scollon & Scollon (Reference Scollon2003).

Figure 2 shows that different elements that make up the sites of multispecies engagement are interconnected and entangled with one another, and meaning is a dynamic interaction between these elements. Consider the experience of touching the elephant as a form of engagement, for example. This haptic action is mediated through the convergence of physical counterparts as there is a human hand, the elephant body, the facilitating role of a mahout, and all the physical structures at the contrived natural setting that make the action possible. Tourists can recreate this memory through semiotic-textual practices (e.g. by posting a selfie accompanied by a textual update on social media) or local tourism business can remediate the phenomenon through a promotional discourse (e.g. by featuring the tourist-animal interaction on its homepage). It should also be noted that sites of engagement can be ‘sites of political struggles’ (Jones Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014) that arise due to competing ideologies and discourses. These struggles get prominence when tourism stakeholders in Sauraha, for example, claim elephants are utilized not only for profit but also for wildlife conservation.

While all elements that make up the sites of engagement are crucial, I pay special attention to the spatialization of human-elephant engagement because understanding the spatial dynamics of these (inter)actions can reveal important insights into how space both constitutes as well as is constituted in participants’ actions. This study references various spaces shaped by the actions of humans and nonhuman animals: physical spaces (e.g. ticketing offices, parks), micro-spaces (e.g. body inscriptions), virtual spaces (e.g. social media), relational spaces (e.g. human-animal interactions), and third spaces (e.g. ideological positions invoked in these actions). I trace the relationships among texts, actions, and objects in both online and offline spaces because, I believe, doing so offers us empirical validity for understanding the multispecies world.

Fieldwork and data

The fieldwork centers on wildlife tourism and its associated built and natural environments at CNP and its vicinity in southern Nepal. Ethnography was conducted through multiple short visits in 2015, 2019, and 2024. Data collection involved gathering observation notes, conducting interviews, and capturing photographs of tourism-related spaces and activities. I frequented key locations such as the CNP itself, elephant riding areas, and the elephant breeding center. For this article, I concentrate on the town of Sauraha, where tourism facilities are concentrated and which represents the coalescence of natural and cultural elements relevant to wildlife. The town serves as a gateway to the park and is a popular base for tourists who wish to explore the park and participate in wildlife-related activities such as jungle safaris, elephant rides, and bird watching. To account for how the spaces in Sauraha engage with the wild, I conducted a walking ethnography, taking pictures of signage and architecture that feature the elephant in discursive and material forms. To capture humans’ direct engagement with the animal, I attended elephant-related cultural activities aimed at tourists, particularly elephant polo championships and elephant beauty pageants. These events serve as active ideological spaces where researchers can observe the processes shaping social actions.

The audience of these spaces and events in Sauraha included domestic Nepali tourists, regional tourists from India and Sri Lanka, and international visitors from countries such as the UK, Germany, the United States, China, and Australia. Visitors also included volunteer tourists, researchers, and conservation interns. Events like the Elephant Polo Tournament and Elephant Beauty Pageant attracted wide-ranging spectators. Polo players represented countries including India, England, Scotland, Iceland, Hong Kong, and Australia, while the pageant drew both domestic and international attendees. These events and their visual-material environments were not only consumed by those physically present but were also circulated by international media including Aljazeera, Reuters, The Telegraph, and China Daily to wider audience.

Positionality

My interest in this research is deeply personal as well as academic. Having spent a significant portion of my youth in a town close to CNP, where elephants were a visible and often celebrated part of the local tourism economy, I developed both a sense of familiarity with and critical distance from this environment. Over time, I have encountered numerous reports and testimonies—both journalistic and ethnographic—detailing the physical coercion and psychological stress inflicted on elephants during training, particularly in preparation for tourism activities such as rides and performances. These accounts have shaped my ethical stance. I do not support the use of elephants or other animals in tourism, even when such practices are framed in terms of conservation or the livelihoods of mahouts. While I recognize the complex socioeconomic realities that sustain these practices, I believe that ethical conservation must prioritize animal agency and well-being. My position is that elephants thrive best in their natural habitats, free from the demands of tourist entertainment. My approach to this research is thus informed by a commitment to multispecies justice, and by a motivation to critically examine how commodified multispecies encounters reproduce hierarchies of control, care, and value.

And, my ontological position on language is grounded in an expanded understanding that goes beyond human-centered linguistic codes to include gestures, material symbols, spatial arrangements, and multisensory cues (Shankar & Cavanaugh Reference Shankar, Jillian, Jillian and Shankar2017; Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018). This conceptualization challenges sociolinguists to reconsider the object of study, where language may not always hold primary importance. Moreover, this ontological shift turns the focus away from humans as the center of social analysis and instead encourages us to ‘attune’ more closely to the many ways humans and other species interact (Tsing Reference Tsing, Omura, Otsuki, Satsuka and Morita2019). This invites a renewed curiosity and attention to the roles that nonhuman beings and their actions play in shaping these connections (Lamb Reference Lamb2024b). In wildlife tourism contexts like elephant tourism at Sauraha, human interaction with nonhuman animals often relies on non-verbal modalities such as gaze, touch, and ride. Additionally, actions are not always human-shaped; wildlife can influence human’s interactional, embodied, and spatial practices at the micro-level and cultural, economic, and political worlds at the broader level.

Findings

Spatializing the elephant as a tourism object

In this section, I address my first research question and argue that neoliberal conservation in Sauraha is enacted when tourism stakeholders intervene in both material and digital spaces through signs, texts, and objects imbued with rich indexical meanings that highlight the elephant’s economic potential. Here I find it useful to draw on Shankar & Cavanaugh (Reference Shankar, Jillian, Jillian and Shankar2017:2) and others who argue that integrating language and materiality in analysis helps us understand how meaning and value are produced, while also shedding light on how ‘language is embedded within political economic structures and relations’. I start with the analysis of how the tourist town engages with the elephant through representational discourses and material semiotics. I then pay special attention to how local tourism stakeholders navigate tensions created by the commodity value of wildlife tourism on the one hand and the discourses of ethical tourism and wildlife conservation on the other.

One key mode of engagement I notice is the ‘lifting’ of the wild into the material environment where tourist booking offices and restaurants are located. During my multiple walking tours in the town, the signage landscape depicted interaction with the elephant as a must-have tourist experience. The signage of the tour booking office in Figure 3a, prominently features ‘elephant ride’ and ‘E.B.C.’ (Elephant Breeding Center) as key attractions, alongside other nature-based activities such as ‘jeep safari’ and ‘jungle walk’. This promotional material suggests that the elephant ride is not merely a trip in itself but an opportunity to encounter other exotic and endangered species, including the one-horned rhino and the Royal Bengal tiger. Embedding the elephant image into these various elements gives rise to a semiotic configuration that generates specific values and facilitates distinct social interactions for visitors. Collectively, these elements transform the multispecies space into a commodified entity, defining it and its contents as attractions for tourist consumption. The signs, both linguistic and otherwise, have significant tangible effects: the economic viability of the location is heavily reliant on the presence of these signs, objects, and services. The use of English on the signage might suggest that it primarily targets English-speaking tourists, presumably from Western countries, since CNP’s tourism has historically catered to the imagination of the West. However, the situation has changed today. Given the recent increase in Nepali domestic and regional tourists (Jacoves Reference Jacoves2023), particularly from India and China, the signage and the material environment reconfigure the location both as local and translocal.

Figure 3. (a) Promotional signage featuring tourist activities, inclucing elephant ride; (b) elephant sculpture at the intersection of tourist town; (c) elephant sculpture in hotel swimmming pool; (d) elephant head sculpture at hotel gate; (e) coin bank with elephant carving; (f) elephant statuette (photos by the author).

The elephant sculptures in Figure 3 placed at some key locations of the tourist town including at a road intersection (b), swimming pool (c), and hotel gate (d) serve as an iconic symbol for place branding. This form of human-animal engagement involves the creation of representations that are not meant to deceive but can produce convincingly realistic outcomes. The material presence of the elephant itself becomes a semiotic resource in the meaning-making process, its significance influenced by how locals leverage its presence to participate in the global economy of tourism. The elephant object (b) is entangled with the words ‘HATTI CHOWK’, which give name to the location, translating to ‘ELEPHANT JUNCTION’. Emplaced alongside the animal icon are the words printed on heart shapes ‘LOVE SAURAHA’ (b) and ‘CHITWAN PALACE’ (d), apparently reflecting the symbolic, affective, and commodity value of the animal. Much like the iconic HOLLYWOOD sign functions as an emblematic language object to brand and commodify place identity (Smith, Järlehed, & Jaworski Reference Smith, Järlehed and Jaworski2025), the elephant sculptures and signage in Sauraha similarly operate as symbolic anchors in the construction of a tourist-oriented landscape. The meanings and significance generated through these entangled emplacements are shaped by the spatial, socioeconomic, and historical contexts in which they are situated. Following Jaworski (Reference Jaworski2015), these words function as language objects, symbolically contributing to the social construction of space through a ‘thingification’ of the heart, the animal, and language. Likewise, in the same figure, the coin bank with an elephant carving (e) and a elephant statuette (f) found at a souvenir store are largely indexical of the intersection between local identity, cultural authenticity, and political economy (Pietikäinen & Kelly‐Holmes Reference Pietikäinen and Kelly‐Holmes2011) in connection to the ecology wildlife tourism. Following this conceptualization, elephants are enregistered sources of value, and their emplacement within the landscape generates commodity values that transform both the context and the landscape, mediated by political economy.

The material structures and words in Figure 3 serve as an illustrative example of tourism’s reliance on the aesthetic economy where values influenced by charismatic wildlife intersect with commodity values. Drawing on Jaworski (Reference Jaworski2015), I argue that this process manifests in two significant ways: first, materials hold cultural significance beyond their practical utility, conveying meaning beyond their function. Second, cultural and ecological elements that were previously not tied to exchange value are now produced, circulated, and utilized within economic frameworks. The aestheticization process aims to create uniqueness, surprise, and excitement for both locals and tourists. This is demonstrated through a link between the animal, material space, text, and ideograph (heart). In a world increasingly shaped by capitalism and consumption, the aesthetics of this place is more complex than mere decoration; it is a reflection of capitalism’s drive to turn novelty into profit (Weaver Reference Weaver2009). Furthermore, echoing Jaworski (Reference Jaworski2015), the mediated actions that might emerge when tourists interact with the objects, with the sense of ‘been there, done that’, the sites of engagement link them with the values of this specific place, practice, and ideology. The deployment of such animatronic architectures is not strictly local but can be observed in various global locations. The portrayal of these animals as synecdochic figures has anthropogenic implications, representing the condition today of their own habitats and the landscapes they traverse. In these complex arrangements, Sauraha’s elephant sculptures and statuettes play a mediating role (Jones Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014) by bridging diverse elements such as art, corporate interests, and threatened territories in the wild.

The second part of my argument is that even stakeholders who claim to practice ethical tourism continue to use wildlife as a core element of their branding strategies. Over the past decade, increasing awareness of animal rights (cf. O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2025) has led to a decline in the popularity of elephant rides among Western tourists in Sauraha although this decline has been counterbalanced to some extent by the rise of a new category of tourists from India, China, and Nepal (Jacoves Reference Jacoves2023). Local businesses must now navigate the tension of making profits while addressing concerns about animal abuse and wildlife conservation, particularly through responsible tourism activities. In alignment with global trends in neoliberal conservation (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2015), the private sector in Sauraha has followed the footprints of the neoliberal market where discourse plays a central role in shaping the ideologies of ethics through which animal care and conservation are mediated and assigned social significance.

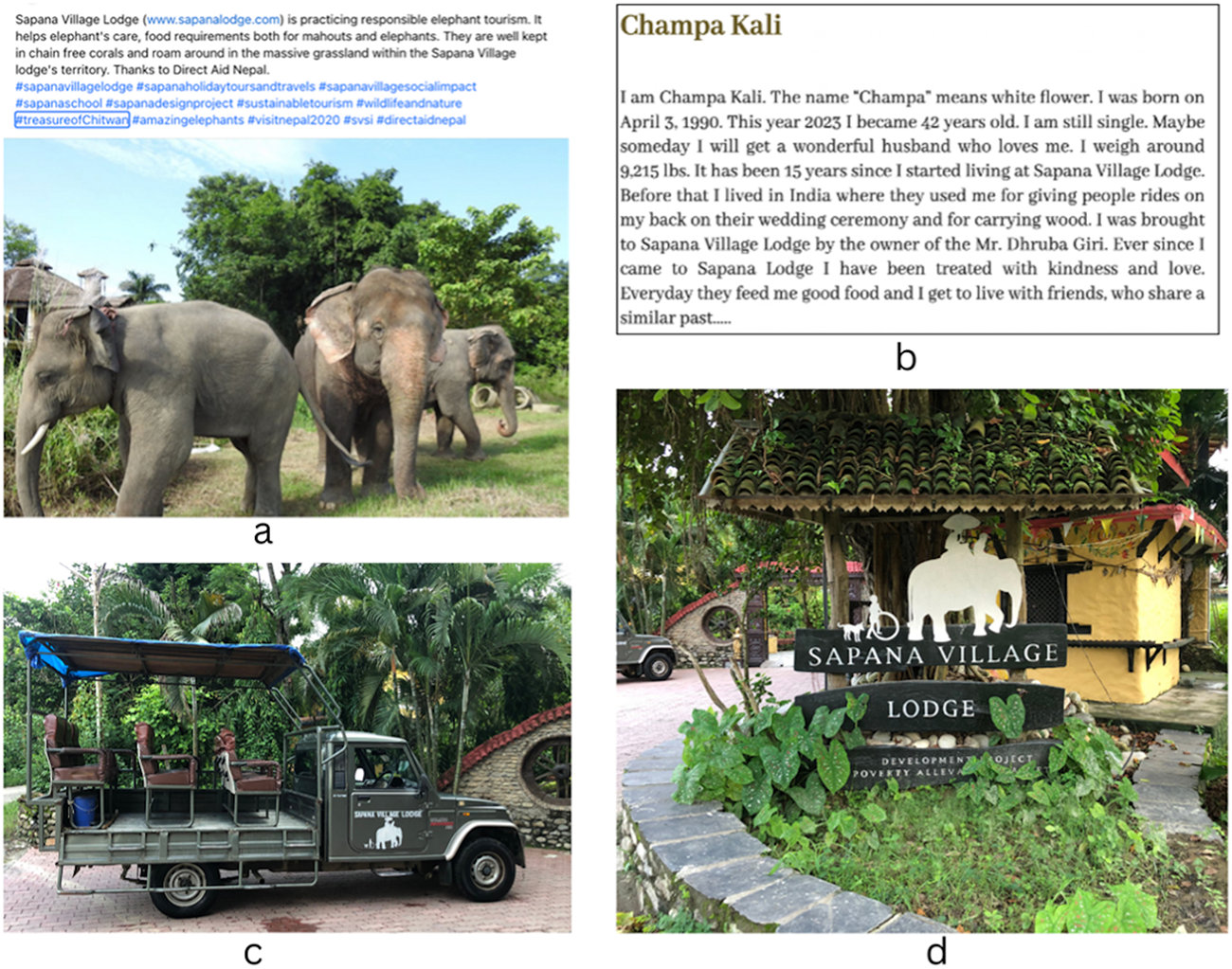

From my fieldwork, I provide the oft-noted example of Sapana Village Lodge, which, in collaboration with the non-governmental organization Direct Aid Nepal, now owns six elephants, including a recently born calf. The enterprise positions itself as a leader in ‘responsible elephant tourism’, claiming to spend its proceeds from its activities towards the care of elephants and their mahouts. The social media text by the business owner in Figure 4a not only contrasts its practices with traditional, more restrictive methods practiced in the area but also aligns them with global concerns regarding animal rights and sustainable tourism. The language used in the text appears to appeal to a socially conscious audience by showcasing its dedication to humane treatment and ethical standards. The hotel employs images of its elephants as part of its business branding strategy (Figure 4d), promoting activities such as ‘breakfast with giants’ and ‘bush walk with the elephant’.Footnote 1 While the practice of keeping elephants ‘chain-free’ and allowing them to ‘roam around in the massive grassland’ is commendable, the use of these discursive strategies to market hotel accommodations raises ethical concerns. Furthermore, a humanized testimonial from one of the elephants, Champa Kali, creates a humorous narrative (“I am still single. Maybe someday I will get a wonderful husband who loves me.”) and contrasts her past hardships in India with a better life at Sapana Village (Figure 4b). By attributing personified characteristics to Champa Kali, the text relies on the potential affect economy by showing emotional connection with the animal and challenging traditional views of animals as mere objects of the tourist gaze. In the process, the strategic use of first-person narration recognizes the sense of agency and subjectivity attributed to Champa Kali, portraying her as a sentient being with feelings and desires. By engaging audience through affect, empathy, and ethics this way (“Ever since I came to Sapana Lodge I have been treated with kindness and love”), these discourses position visitors less as mere participants in the tourism market and more as responsible humans. However, the fact that these encounters are employed as promotional discourses suggests that the hotel fulfils its claim to distinction as a high-end resort by metonymically associating the animal with the space and experience.Footnote 2 Such instances exemplify the prevailing orthodoxy in conservation in neoliberal societies like Nepal, where privatized wildlife encounters are claimed to be effective conservation tools (Szydlowski Reference Szydlowski2024).

Figure 4. (a) Resort’s social media post; (b) testimonial on resort’s homepage by elephant; (c) resort’s logo on jungle safari vehicle; (d) elephant image on resort’s gate.

Anthropomorphic engagement with the elephant as a spectacle

Extending the argument that spatial (re)configurations are integral to neoliberal conservation strategies, I turn to my second research question: How are elephants commodified through their embodied presence and performances in the landscape? I analyze various dimensions of corporeal human-elephant engagements, which are mediated through linguistic, visual, and kinesics enactments within tourism spaces. This process raises a critical question: how are such commodified encounters sustained in an era marked by growing awareness of the tensions between animal abuse and ethics? I find that tourism’s anthropomorphic engagement with elephants in Sauraha encapsulates these very tensions and contradictions. Here, I focus on two elephant-related events: polo championship and beauty pageant.

Elephant polo typically features teams of four players riding atop each elephant. The equipment includes cane sticks with polo mallet heads, and the pitch is three-quarters the length of a standard polo field to accommodate the elephants’ speed. The activity closely mirrors the rules of traditional horse polo but with adaptations to suit the slower pace and unique dynamics of the game. As the matches unfold, each elephant is guided by a mahout, with players directing the mahout’s movements and striking the ball to score points (Zinggl & Cachafeiro Reference Zinggl and Cachafeiro2015). Beyond entertainment, both the organizers and the players claim that the tournaments serve as a platform to raise awareness about elephant conservation efforts and support local communities through charitable initiatives.

I argue that elephant polo exemplifies how capitalist logics appropriate wildlife and cultural spectacle for elite leisure consumption by reinforcing colonial legacies and commodifying animal labor in the guise of sport. The activity quintessentially shows the convergence of various spaces, participants, and mediational means through which elephants are enregistered as sources of value via traversing discourses, historical bodies, and participation frameworks (Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2014). For the mahouts who steer the elephants, the action is made possible through strong affective relationships, care, and trust with the animal, developed over the years of mutual adaptions, grooming, and training (Locke Reference Locke, Locke and Buckingham2016). For the mahouts, the actions constitute work rather than sports where resources, bodies, and skills are constantly valued and transformed into capital and commodities. For the players, every action is conceivably taken as a source of fun, control, and conquest. For the spectators, the activity can appear as an elegant and light-footed ballet due to the slower speed of the heavyweight elephants as they take unexpected turns and display seemingly incongruous behaviors (Zinggl & Cachafeiro Reference Zinggl and Cachafeiro2015). And for the elephants, their spatial movements are controlled by the humans on their backs, often mediated via verbal, corporeal, and material tools, directing them where to move on the field and when to stop. Activities that exploit elephants to facilitate such engagement entail significant emotional labor from both human and nonhuman participants. And, while the elephants appear to have agency to decide the speed and the direction of their movement, they are significantly constrained. These modes of engagement illustrate ambivalent deployment of trust and domination in the relationship between the two species (Ingold Reference Ingold, Manning and Serpell2002), where trust fosters an ethical form of coexistence by acknowledging the agency the animal, whereas domination reduces the animal to a mere tool for human use. This tension is visible when the elephants do not always obey the mahouts and the players, or do not perform as directed.

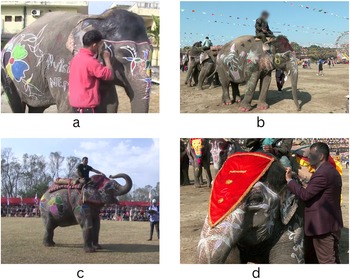

Under capitalist logics, the symbolic and material elements of elephant polo are deployed to generate and reinforce the commodity value of both wildlife and elite sports. The way this is achieved using discursive and semiotic tools not only sustains that value but also reflects the interplay between local traditions and global trends in sports tourism. I find that these processes deploy visual displays that turn bodies into corporeal landscapes or skinscapes (Roux, Peck, & Banda Reference Roux, Peck and Banda2019). For the preparation of each event, the mahouts adorn their elephants with colored chalk, with each elephant receiving its own distinctive human name such as Selfie Kali, Rimjhim Kali, Srijana Kali, Lucky Kali, and Champa Kali. As shown in Figure 5, the inclusion of Nepali designation on the body in Romanized English—such as Durga Kali—blends traditional religious name दुर्गा [Durga] with a nature symbol कली [kəli]. Traditionally, Durga is typically depicted as a Hindu warrior goddess riding a lion or tiger and associated with protection against evil forces. When it is combined with kali, which literately translates as ‘flower bud’, it further feminizes the elephant’s name. The name arguably signifies feminine courage and strength, presumably necessary to defeat the opposing team and win the game.

Figure 5. (a) Polo players with ‘Tuskers’ t-shirts; (b) elephant polo prints on player’s arm; (c) player practicing with elephant; (d) players on the field (photos: Martin Zinggl).

Further, several semiotic interventions at the site of engagement enhance the value of the elite leisure. The material sign in English TIGER TOPS seen at the margin of the polo field or on the shirt of a player in Figure 5a and 5d indexes the history of elephant safari and elephant polo. In 1982, two British nationals established the World Elephant Polo Association at Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge—a site emblematic of the colonial legacy of animal exploitation. The lodge then became a central hub for elephant polo, hosting the annual World Elephant Polo Championships from that year onward (Zinggl & Cachafeiro Reference Zinggl and Cachafeiro2015). Likewise, players, who are the raison d’être for the activity, embody distinct identities. For example, consider the print image of an elephant on the body or on the shirt of the players in Figure 5a and 5b. The elephant polo tattoo and the print hold significance as the individuals appear to imbue them with their relationship, histories, and affect related to the activity. These texts are an elite identity marker of the polo player who appear to be members of the World Elephant Polo Association.

Elephant polo in Sauraha, thus, encapsulates a broader nexus of practice and ideology, centered on symbolic consumption of the wildlife and the conspicuous display of such consumption to the public. The seemingly innocuous sports activities are deeply rooted in the material privilege that allows the tourists to partake in such activities, including financial means, time, and opportunities. Although the organizers claim that the proceeds from the event are spent for the conservation of the very animal, the whole project benefits global capitalism through the commodification of nonhuman animals and constitutes an instance of animal abuse and cheap local labor exploitation.

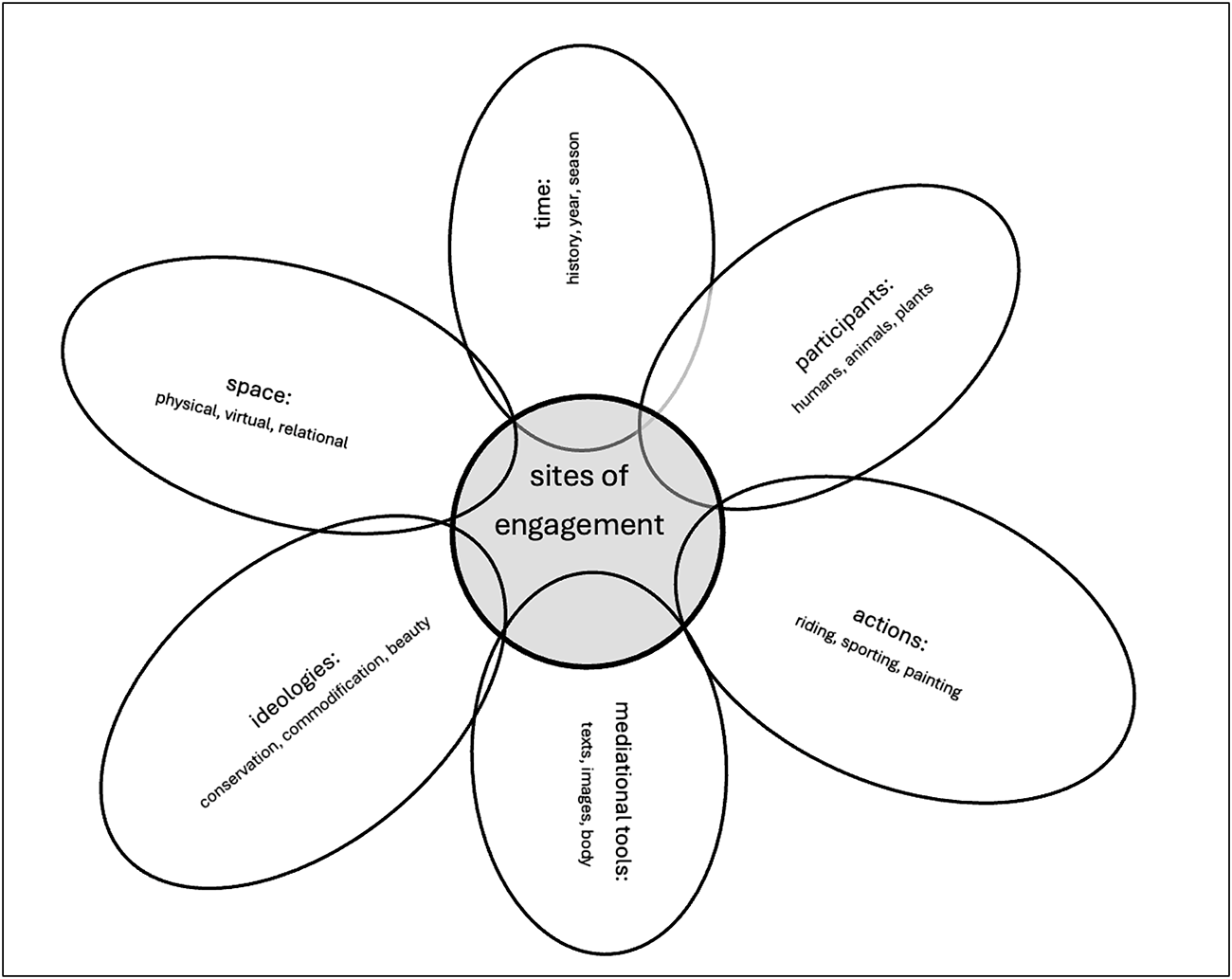

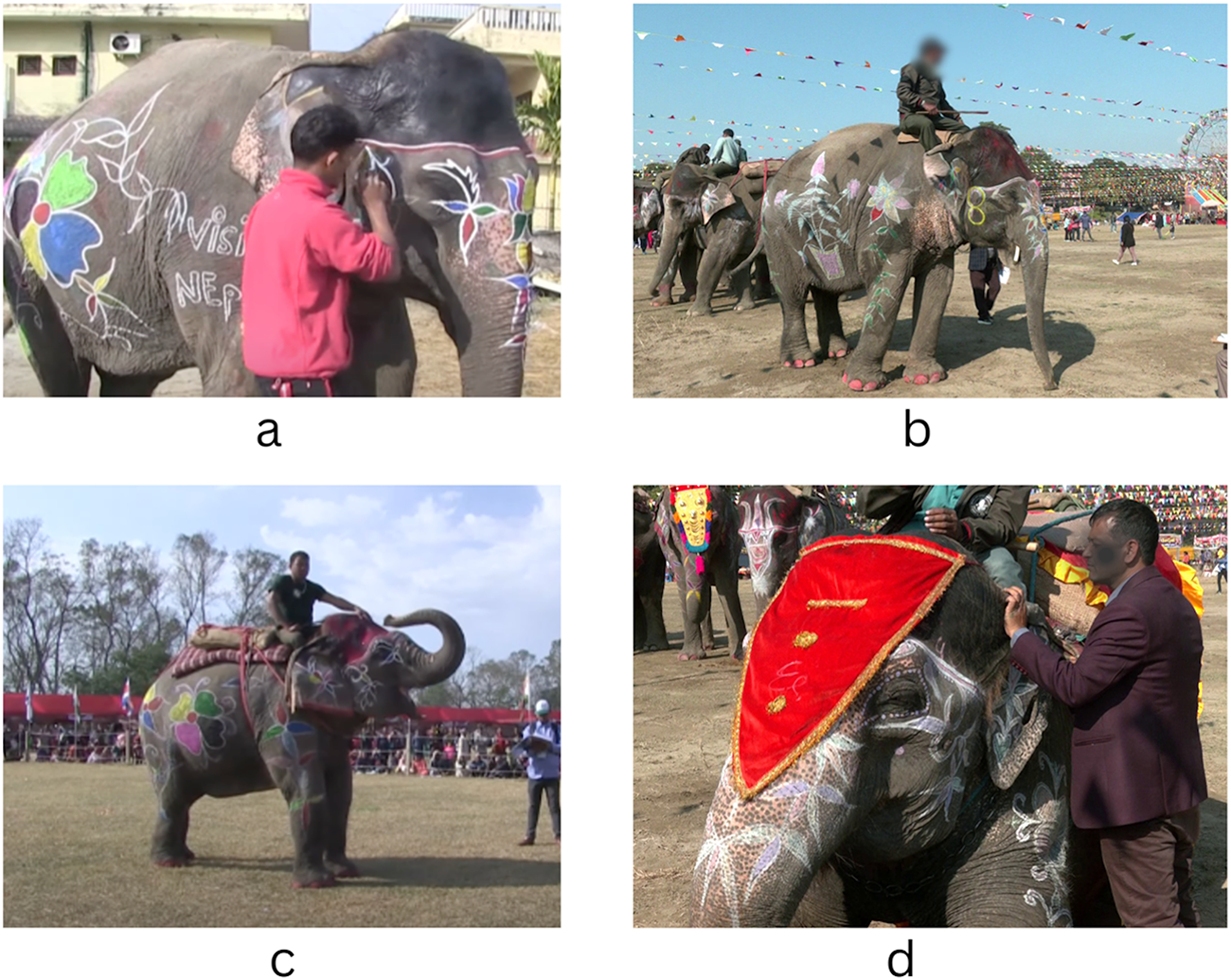

After the cessation of the polo championship in 2019,Footnote 3 the Elephant Beauty Pageant has started becoming the signature event of the multi-day festival although the tradition started in 2010. Observing the pageant in its entirety, I find that the event unfolded as a series of semiotically and interactionally mediated anthropomorphic actions. These performances demonstrate the interplay between tradition and commodification, both shaped by the political-economic value of human-elephant engagement. To prepare elephants for the contest, mahouts typically offer the elephants baths, trim and paint their nails, and apply eyeliner to enhance their appearance. The elephant’s body arguably becomes a living canvas, featuring religious symbols such as flowers, peacocks, colored powders, and sacred geometries (see Figure 6a). The inscriptions in Figure 6 point to the Hindu tradition in which the elephant is considered a divine animal due to its association with the elephant-headed god Ganesh, who symbolizes strength, power, and auspiciousness. And Ganesh is portrayed sitting on lotus petals, which is considered to signify purity and enlightenment for many (Grewal Reference Grewal2009). The semiotics of the sophisticated artwork, thus, not only adorns the elephants but also reshapes their identities, authoring their bodies anew, and instilling them with layers of cultural significance. These actions shift the mode of human-elephant engagement from the spectacle of tourist gaze to mutuality and co-existence characterized by affect and multispecies care (Curtin Reference Curtin2005; Locke Reference Locke, Locke and Buckingham2016).

Figure 6. (a) and (b) Preparing (body and nail painting) the elephant for pageant; (c) elephant performing mahout’s commands for judge; (d) judge examining elephant’s cleanliness (photos: Binod Adhikari).

However, the Elephant Beauty Pageant in Sauraha is far from just being a cultural event; it is shaped by problematic ideologies in which elephant contestants are evaluated through anthropomorphic beauty standards that both objectify and commodify the animal. This becomes evident during the contest, as the elephants perform a sequence of humanoid acts under the direction of their mahouts, which are then evaluated by a panel of judges (Figure 6c). Citing comments from one of the pageant judges, excerpt (1) taken from a published YouTube videoFootnote 4 offers some details.

(1)

1 We had nine criteria to announce an elephant the winner.

2 The most important thing to consider at the time of judgement

3 is the body figure of the elephant. Then we pay attention

4 to how the elephant is decorated. We judge based on that.

5 Likewise, we consider the elephant’s walk; we call it catwalk;

6 we make decision based on that. Then we look at whether the

7 elephant is obedient to the mahout in following directions;

8 we consider how disciplined the elephant is. Then we pay

9 attention to the cleanliness of the ear and the toenails

10 and, based on these we announce the finalist.

Excerpt (1) elucidates how the judgement of the pageant reflects market-shaped anthropomorphic views of the animal kingdom, in that individuals transpose human societal values onto animals and see their world through their own human reference (Curtin Reference Curtin2005). The hierarchical listing of criteria in the extract places significant emphasis on the elephant’s physical appearance. Attention to beauty details is shaped by a human perspective, emphasizing criteria such as the cleanliness of the ears and toenails (lines 7–8 and Figure 6d). The use of metaphors often used in fashion shows, such as describing the elephant’s walk as a “catwalk” (line 5), projects one animal’s style of walking onto another animal, mediated by human indexical conventions and actions. This value-laden anthropomorphism is problematic, as it disregards the natural characteristics and physical abilities specific to the animal species. Additionally, the reference to the elephant’s obedience to the mahout reproduces the domination-submission relationship between the two species (lines 6–7 and Figure 6c) while also acknowledging the possibility that such a relationship is not guaranteed.

The anthropomorphic aestheticization of the elephant and its market-shaped judgement present us with contentions. Some (e.g. Burns Reference Burns, Burns and Peterson2014; Manfredo, Urquiza-Haas, Don Carlos, Bruskotter, & Dietsch Reference Manfredo, Urquiza-Haas, Carlos, Bruskotter and Dietsch2020) argue that anthropomorphism can serve as a catalyst for shifting from a dominant human-centered perspective to one of mutualism, where wildlife is regarded as part of the social community, while also deepening emotional bonds and fostering ethical relationships that contribute to a shared interspecies future. However, others (e.g. Lorimer Reference Lorimer2015) caution that anthropomorphism can reinforce human-centered perspectives, potentially marginalizing or overlooking the unique characteristics and needs of non-human animals and prioritizing human values over those of other species or ecosystems. I argue that the sites of human-elephant engagement during the beauty pageant, on the one hand, reflects the local tradition of venerating elephants through body painting and religious symbolism, but it, on the other, signals aspects of wildlife tourism shaped by tourist gaze in neoliberal societies. The tension constitutes an awkward simultaneity between pride and profit, tradition and commodification (Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2012).

Conclusion

This study’s analysis of human-elephant engagement at Sauraha’s eco-semiotic landscapes has illuminated a form of neoliberal conservation operating within Nepal’s most prominent ecotourism site. The commodification of wildlife reflects a specific ideological framing of nature, shaped by the enduring modern binary of the nature and culture. This anthropogenic engagement materializes when stakeholders make deliberate semiotic and spatial interventions to brand the wildlife through an entangled relationship of various modes, including written language, visual representations, material displays, and multispecies performances. The notion of sites of engagement (Scollon & Scollon Reference Scollon2003; Jones Reference Jones, Norris and Maier2014) helped to conceptualize and expand the analysis by attuning to human interaction with the more-than-human world, where sign-making is not just about written language or visible objects in space but also about nonhuman species, cultural meanings, and economic ideologies. Sauraha’s tourism practices are unavoidably mapped onto geographies of power and intertwined with histories of anthropogenic practices. As such, I argue that the multispecies landscapes are intricately entangled with global inequalities, shaped by neoliberal and neocolonial sleights of hand that strategically serve the interests of the privileged. These formations often obscure the historical roots and material consequences of such inequalities (cf. Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2014). This dynamic is especially evident in promotional discourses and practices surrounding commodified encounters between humans and elephants, particularly in Sauraha’s luxury hotels and leisure sports, which frequently overlook the precarious conditions of the elephants and the low-paid labor of their mahouts. While my data are limited, they offer a glimpse into how mahout-elephant engagements may point toward a different version of human-wildlife relations—one in which all species act as lively agents in the co-production of landscapes. A salient example is the care and ritual adornment of elephants in preparation for festivals, which reflects affective and mutual dimensions of multispecies life (see Locke Reference Locke, Locke and Buckingham2016 for details on such relationships). Moreover, the apparent tension between acts of multispecies care and anthropogenic control may at times show fractures in the singular narrative of an anthropocentric tourism landscape, such as when elephants disobey mahouts or polo players. Nevertheless, the tourism industry largely fails to acknowledge these relational dynamics.

Of all the justifications offered by local businesses for the use of elephants in tourism, the most unanimous response I encountered was: ‘The proceeds go to the conservation of the elephants’. Despite this rhetoric, Sauraha’s wildlife tourism practices spatialize anthropocentric ideals and values and raise questions about the justification of conservation efforts through the commodification of elephants, regardless of how ethical they might appear. Here, I find that my observations align with those concerning anthropomorphic practices described by Lamb (Reference Lamb2024a), and I argue that the interspecies relationships established through a series of spectacle-oriented discourses and actions are, at best, superficial and, at worst, socially and ecologically harmful. Rather than confronting planetary crises as shared consequences of entangled existence, neoliberal conservation in Sauraha reinscribes old separations, delaying the possibility of more ethical and reciprocal interspecies futures. The case shows that unless these ideological fault lines are addressed, tourism will continue to aestheticize nature while effacing the very ecological urgency it claims to valorize. Amidst these realities, I argue that anthropomorphism should be embraced by humans in a way that does not privilege humans and therefore engagements with wildlife, semiotic and otherwise, should ‘relocate ourselves with animals instead of above them’ (Szydlowski Reference Szydlowski2024:21, emphasis in original). Interspecies ethics is necessary for guiding human interactions with nonhuman entities as we navigate the challenges posed by humanity’s significant impact on the planet.

Acknowledgments

The images I reproduce here are either my own or are used fairly for the purposes of scholarly comment and critique. I am particularly grateful to Martin Zinggl and Binod Adhikari for their permission to reproduce their images. Also, I am grateful to the CLASS Summer Research Grant 2024 at the University of Idaho.