Introduction

Linen has been used for a variety of purposes since Antiquity, in ritual or dwelling contexts as well as clothing, and from ancient Egypt to modern times (Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood, Nicholson and Shaw2000). Flax fibers were also largely produced to manufacture sails, bags and fishing equipment (Melelli et al. Reference Melelli, Jamme, Beaugrand and Bourmaud2022). Additionally, in the 15th century, linen emerged as a support for paintings and linseed oil as a pigment binder in oil paints. During the Renaissance, linen canvas proved more practical than wooden panels for oil painting, enabling artists to create large and stable works that could be transported and displayed. Over the centuries, other fabrics have been used for canvas, such as cotton and, more recently, synthetic fibers. However, even today, many contemporary artists prefer linen, as they consider it to be the best quality support due to its strength, dimensional stability, and durability (Perego Reference Perego2005).

Linen and linseed oil are derived from flax (Linum usitatissimum), a short-lived plant, making them ideal materials for the radiocarbon (14C) dating of paintings (L. Beck Reference Beck2022; Beck et al. Reference Beck2022; Caforio et al. Reference Caforio2014; Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks2019). However, a number of steps must be taken into account to estimate the completion date of a painting from a 14C date. Flax has the advantage of growing rapidly: in Europe, flax seeds are sown in April, and the plants mature in July. One month after blooming, flax is pulled up by the roots for the fibers or harvested by cutting above ground level for linseed oil production. In order to obtain fibers, flax is retted in water or by spreading the plants on the fields for several days and up to two months. The fibers are then separated by scutching and sent to a spinner that turns raw fiber into yarn. During spinning and later weaving, different batches of fibers from different parcels, different regions and different years are blended to homogenize the production. The linen canvas obtained is then covered with a ground that maintains the tension of the fibers and insulates them from chemical interactions with the paint layers. This ground is composed of the size, typically rabbit skin glue firstly applied on the canvas, and then several layers of priming. The composition of the preparation layer(s) depends on the geographical and chronological context, but lead white is one of the most widely used paints due to its density and opacity (Stols-Witlox Reference Stols-Witlox2014).

The whole process takes a certain time, which must be estimated in order to date a painting by 14C. In previous work, Brock et al. (Reference Brock2019) measured a time lag of 2–5 years, sometimes more, between the harvesting of plant fibers and the completion of a painting, based on the study of canvases of various Scandinavian artists from the mid-20th century. In the present paper, a similar approach is proposed, but combining canvas and binder and focusing on the paintings of a single artist, the French painter Pierre Soulages (1919–2022), who was active from 1939 to 2022. This internationally renowned artist had an exceptionally long career, and his paintings have another advantage for our purposes: he titled his works with the day on which he considered them finished. The titles always follow the same pattern: technique, dimensions, day, month, year, e.g. “Peinture 114 x 165 cm, 16 décembre 1959” for example. The painting conservator specialized in the artist documented his technique and collected samples of canvas from taking margin during conservation treatments (Hélou-de La Grandière Reference Hélou-de La Grandière2023; Hélou-de La Grandière et al. Reference Hélou-de La Grandière, Casadio, Keune, Noble, van Loon, Hendriks, Centeno and Osmond2019, Reference Hélou-de La Grandière2023; La Grandière Reference Grandière2005). These previous studies have made a large corpus available, in which the bomb-peak calibrated 14C dates obtained both on the canvas and on the binder of the preparatory layer can be compared to the dates of completion. This study aims to provide reliable data for tracing the 14C bomb peak fingerprint of flax in the artworks to improve the radiocarbon dating of 20th century paintings.

Methods

Samples of canvas and lead white paint layer

The pre-primed canvas samples (Figures 1 and 2) were taken from the excess canvas on the reverse of paintings by P. Soulages, with no consequence on the artwork. Twenty-five samples dated between 1956 and 1981 were collected for 14C dating. Some of them had been previously characterized by Renouvel-Coustet (Reference Renouvel-Coustet2023) and confirm the use of natural fibers, identified as linen. All the canvases were pre-primed by the artist’s supplier with a preparation layer composed of two main components: a lead white pigment containing cerussite and hydrocerussite, and a binder, mostly identified as linseed oil.

Figure 1. Canvas sample #PS3 taken from the reverse of a painting by Pierre Soulages completed in October 1959.

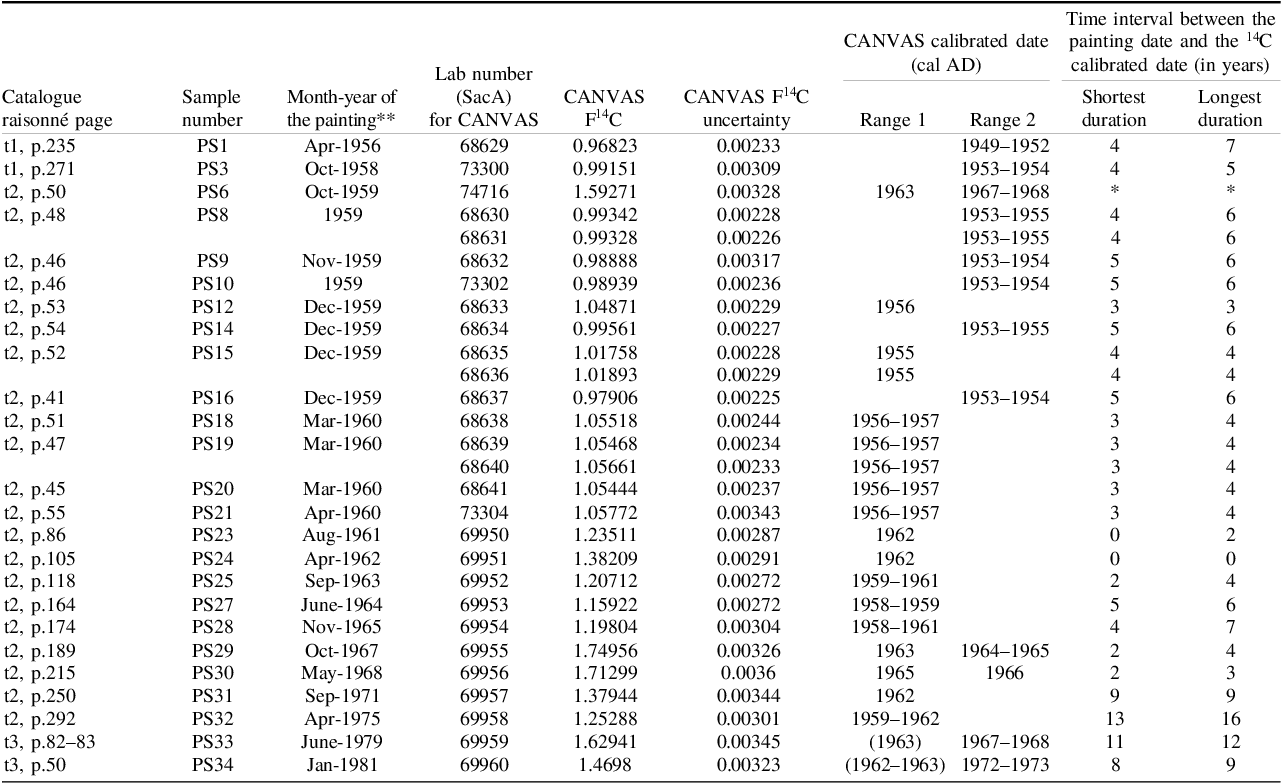

Figure 2. Preparation protocol for 14C dating of canvas and paint layer (oil binder and lead white pigment). Photo: sample #PS18, scale = 1 mm.

Preparation

Both canvas and paint were prepared for radiocarbon dating according to the protocol presented in Figure 2.

For the canvas, a fiber of 3–20 mg, taken far from the painted area, underwent routine ABA (acid-base-acid) pretreatment as follows: HCl (0.5M, 80°C, 1 hr), NaOH (0.1M, 80°C, 1 hr), HCl (0.5M, 80°C, 1 hr). Between each treatment, the fiber was rinsed with deionized water (Millipore© reverse osmosis water, COT<5 ppb) until a neutral pH was reached. After drying, the fiber was combusted in the presence of CuO and Ag at 850°C for 5 hr. The resulting CO2 (Canvas CO2) was purified and cryogenically collected in a tube through a vacuum line.

For the preparatory layer, flakes of paint layer were mechanically removed from the canvas using a clean scalpel and processed according to an improved version of the procedure developed by Beck et al. (Reference Beck2019) and Messager et al. (Reference Messager2020), which allows CO2 from pigment and binder to be collected separately (Dumoulin et al. Reference Dumoulin2024; Beck et al. Reference Beck, Messager, Germain and Hain2024a). This procedure is based on the thermal properties of lead white, which decomposes into CO2 and PbO at 350°C (C. Beck Reference Beck1950). When lead white and linseed oil are mixed, heating the mixture at 400°C results in the complete decomposition of lead white and the dehydration and partial decomposition of linseed oil (Messager et al. Reference Messager2020). Two phases are produced after decomposition: a gaseous phase containing CO2 coming from lead white and a small part of the linseed oil, and a solid residue containing the non-decomposed part of the linseed oil. This residue is therefore free of lead white and can be used to date the binder.

Between 4 and 30 mg of paint were introduced in a quartz tube and were heated at 400°C for one hour on a dedicated CO2 collection line. The resulting CO2 (LW CO2) was trapped using liquid nitrogen (–196°C) while the PbO and the non-decomposed part of the binder remained in the quartz tube. The residue was then combusted in the same conditions as those described for the fiber and the resulting CO2 produced by the binder (Binder CO2) was collected in another tube.

Radiocarbon dating

Graphite targets were produced by the reduction of CO2 by hydrogen over an iron catalyst following the reaction described by Vogel et al. (Reference Vogel, Southon, Nelson and Brown1984). Samples were accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dated using the ARTEMIS facility at the LMC14 laboratory (Beck et al. Reference Beck2024b).

On the 25 pre-primed canvases of Pierre Soulages’ paintings, 28 radiocarbon determinations were obtained for the canvas (25 canvases and 3 replicates). For some samples, the painted area was too small or contaminated by acrylic compounds from the pictorial layer or varnish. For these reasons, only 13 radiocarbon determinations were obtained for binders and lead whites. The Fraction Modern (F14C) for the canvas fibers and the linseed oil binders are reported in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Lead white results are beyond the scope of this article and will be presented in a separate publication (Coustet et al. in preparation).

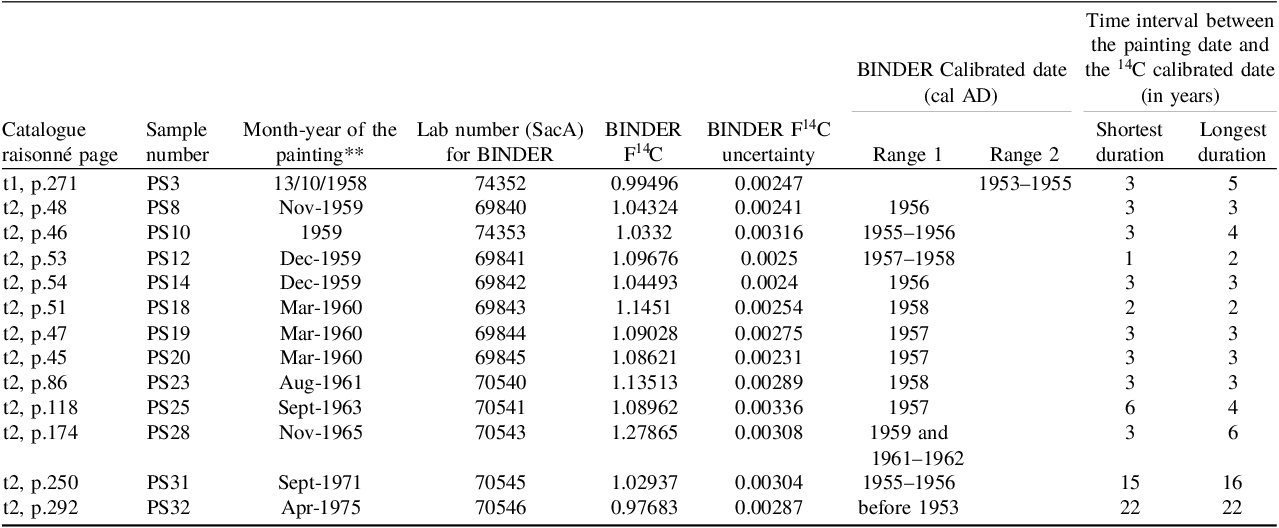

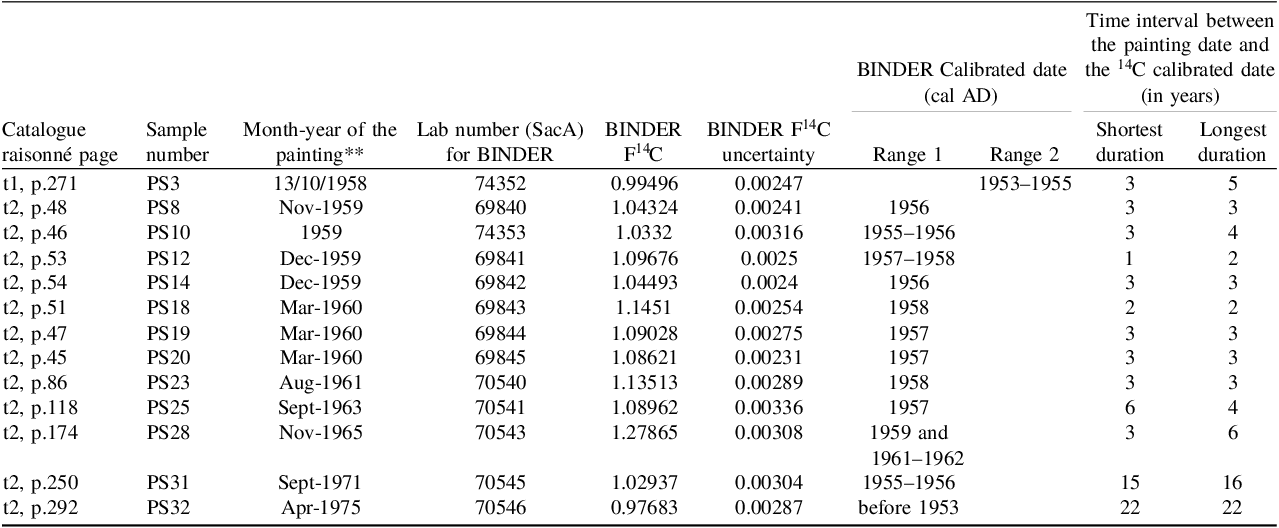

Table 1. F14C, calibrated date ranges and time interval between the painting date and the 14C calibrated date for canvas samples from the paintings by Pierre Soulages. All dates were calibrated using OxCal v.4.2.4 and the Bomb21 NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua2022) with a confidence level of 95.4 %. Dates crossed out or in brackets were rejected (see detailed explanations in the text). *: undeterminable. **: for confidentiality reasons, it is not possible to provide the full title of the paintings.

Table 2. F14C, calibrated date ranges and time interval between the painting date and the 14C calibrated date for binder samples from the paintings by Pierre Soulages. All dates were calibrated using OxCal v.4.2.4 and the Bomb21 NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua2022) with a confidence level of 95.4%. Dates crossed out or in brackets were rejected (see detailed explanations in the text). **: for confidentiality reasons, it is not possible to provide the full title of the paintings.

Calibration and calculation of the time interval between the date given by the painting title and the 14C calibrated date

As flax was mainly produced in Europe in the 20th century (Goudenhooft et al. Reference Goudenhooft, Bourmaud and Baley2019), all radiocarbon dates (pre- and post-bomb dates) for the canvas fiber and for the binder linseed oil were calibrated against the Bomb21 NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua2022) in OxCal v.4.4 (Ramsey Reference Ramsey2009).

Calibrated date ranges for the canvas fibers and the linseed oil binders are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. For all samples, two calibrated date ranges (range 1 and range 2) were obtained, corresponding to the ascending and descending slopes of the calibration curve (Figure 3). For most of the samples, one of these two ranges can be excluded thanks to the date of completion given by the artist. For the pre-bomb peak results, dates prior to 1917 were rejected as P. Soulages had not yet been born and he is not known for having reused old material. For the post-bomb peak results, date ranges were discarded when they were later than the title date of the painting. For the two later paintings, June 1979 (#PS33) and January 1981 (#PS34), as the two date ranges were anterior to the painting’s title date, it was assumed that the earliest dates (in brackets in Table 1) could be discarded because they are less likely than the dates closest to completion of the artwork (Brock at al. Reference Brock2019). For paintings completed in October 1967 (#PS29) and May 1968 (#PS30), the two date ranges were kept as they are too close to each other to be differentiated.

Figure 3. Selected F14C (>1) of canvas fibers from Pierre Soulages’ paintings calibrated using the post-bomb atmospheric NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua2022).

The time interval between completion of the painting and the 14C calibrated date was then calculated by subtracting the date of the painting given by the artist from the two extremes of the selected 14C calibrated range (range 1 or range 2). Two values were thus obtained, corresponding to the shortest and longest durations between uprooting of the flax and completion of the painting by Pierre Soulages (Tables 1 and 2).

Results and discussion

Linen canvas

The time that elapsed between the date indicated by the artist and the radiocarbon calibrated date is from less than one year to 16 years for the paintings signed between 1956 and 1981 (Table 1 and Figure 4a). The durations are from 3 to 7 years with a mean value of 5 ± 1 years in the 1950s, from less than one year to 7 years with a mean value of 3 ± 2 years in the 1960s and from 8 to 16 years with a mean value of 11 ± 3 years for the paintings of the 1970s–1980s.

Figure 4. Time range (y-axis) elapsed between the date indicated by Pierre Soulages (x-axis) and the radiocarbon calibrated date for (a) canvas and (b) binder of the lead white preparatory paint layer. The straight lines indicate the average time delay and the shaded rectangles the associated standard deviation.

For Soulages’ paintings before 1970, the results are in agreement with what was observed for other 20th century artists. For example, Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Hajdas and Ferreira2018) measured an offset of 4-5 years for the canvas of an oil painting by Franz Rederer (1899-1965), signed in 1962. Brock et al. (Reference Brock2019) found that 9 of the 16 studied post-bomb artworks dating from 1959 to 1991 gave calibrated date ranges of 1–5 years before the date of painting. Longer time lags (8–10 years) were also observed by Brock et al. (2018) for two paintings signed in 1967 and 1987.

From the 1950s onwards, Pierre Soulages purchased linen canvas in 10 m × 2 m rolls pre-primed with lead white, mainly from the suppliers Lefebvre-Foinet or Adam (Hélou-de La Grandière Reference Hélou-de La Grandière, Casadio, Keune, Noble, van Loon, Hendriks, Centeno and Osmond2019). The canvases from the rolls were then cut and stretched on wooden stretcher by the artist. Based on the 14C results with a mean F14C of 0.990 ± 0.005, it can be proposed that the supports of paintings #PS3, 8–10, and 14 were made from the same roll which was exploited for a little over one year, between October 1958 (#PS3) and the end of 1959 (#PS8 and #PS9 in November, #PS14 in December, #PS10 only dated “1959”). The flax of this roll was harvested between 1953 and 1955. In parallel, in December 1959, Soulages seems to have started two new linen rolls, each of them made with flax harvested in 1956 (#PS12) or in 1955 (#PS15). These new supplies reflect his intensive production during this period—Pierre Soulages painted around 50 artworks a year—and can also be connected to his new second workshop in Sète, in the South of France. For this period, three years seems to be the minimum duration between flax harvesting and completion of the paintings (see painting #PS12). Based on the paintings from end-1958 to end-1959, the prepared canvases appear to have been stored for at least one year, which corresponds more or less to the consumption time of an entire roll. From these results, a minimum duration of two years can be estimated for flax processing, fabric spinning, support manufacturing and selling.

In the following decade, in the 1960s, Soulages’ activity was slightly less intense, with 20–30 artworks a year. The four paintings analyzed from spring 1960 (#PS18-21) show similar F14C, with a mean value of 1.056 ± 0.001, indicating that their supports come from the same roll made with flax harvested in 1956-b1957. In the succeeding years, each painting has its own 14C fingerprint (except PS#24 and 31). This may be due to the sampling procedure, which gave access to only one painting per year for this period, in contrast to the years 1959 and 1960. The time lags between completion of the painting and flax harvesting are more variable for this decade, from less than one year to 7 years, with a mean value of 3 ± 2 years. During this period, it appears that the entire flax processing, from the field to the Soulages workshop, is shorter.

For the painting #PS24 made in April 1962, less than one year was measured, which is surprising. Broke et al. (Reference Beck2019) also observed a similar result for a painting from 1966. It can be attributed to a bias on the calibration curve or an erroneous title by the artist. This second possibility is exemplified by the case of the painting #PS6 dated 1959 but painted on a linen canvas made with flax harvested in 1963 or in 1967–1968 according to its F14C value. This result is in agreement with the conservator’s observation who suspected a later completion date in the 1960s, touched up in the 1990s, based on the examination and the condition of the paint materials. It is therefore an erroneous title (intentional or not), given a posteriori by the artist, but which does not correspond to the real date of production.

For the paintings from the 1970s and 1980s, a longer time lag was measured. From the 1970s onwards, the flax industry in Europe was disrupted by the relocation of fiber processing and spinning to non-European countries whereas cultivation remained in Europe (Messaoudi, 2011). After flax harvesting, the cut plants were sent mainly to China for all the manufacturing stages including fiber extraction, yarn spinning and fabric weaving. During the last two stages, different batches of fibers are commonly blended to homogenize the production. When production was concentrated in Europe in relatively small factories, this blending was limited in space and time, whereas after relocation it can be assumed that the blending resulted from more diverse batches of flax, coming from different regions and various years. Exporting the plants and then importing the pre-primed canvas required additional transport and most likely led to longer storage periods in warehouses. The longer time lags measured may reflect this economic transformation that occurred in the linen industry in the last decades of the 20th century.

Linseed oil

The time elapsed between the date indicated by the artist and the radiocarbon calibrated date is from one year to more than 15 years, with a mean value of 3 ± 2 years in the 1950s and 1960s (Table 2 and Figure 4b). This mean duration is equal to or less than that for the canvases, probably due to the simpler processing involved in oil production, since linseed oil is directly obtained by pressing dried and ripened flaxseeds.

As for canvas, a sudden increase in the durations is observed in the 1970s with high values from 15 to 22 years (#PS31 and PS32) that may reflect the economic transformation that occurred in the linen industry. These long time lags may also be due to the presence of undetected fossil additives, or to a change in the oil extraction mode using solvents depleted in 14C. Further analysis is required to better understand these results.

The 14C content of paintings #PS8, 10, and 14 confirms the attribution of these supports to a single primed roll, as well as for paintings #PS19 and 20. However, two individual binders (from paintings #PS3 and 8) do not match the clusters based on the canvas results. These outliers may be due to the fact that binders are more likely than the canvas to be contaminated with carbon from the paint layers or other organic solvents or additives.

Conclusion

Based on the work of Pierre Soulages, an internationally renowned artist who was active from 1939 to 2022, who titled his paintings with the day on which he considered them finished, it has been possible to measure the time elapsed between the completion date and the radiocarbon calibrated date of 25 paintings from 1956 to 1981.

The radiocarbon dates were obtained on 25 linen canvases and 13 linseed oil binders extracted from the lead white preparatory layer. After calibration using the Bomb21 NH1 curve, time intervals between completion of the painting and the 14C calibrated date were calculated by subtracting the date of the painting given by the artist from the two extremes of the selected 14C calibrated range. Two values were thus obtained, corresponding to the shortest and longest durations between the uprooting of the flax and the completion of the painting by Pierre Soulages.

For the linen canvas, three different time intervals were found: 5 ± 1 years for the paintings from the 1950s, 3 ± 2 years in the 1960s and 11 ± 3 years in the 1970s–1980s. These results are in agreement with those of Brock et al. (Reference Brock2019). For the linseed oil, the time intervals obtained were 3 ± 2 years in the 1950s and 1960s and more than 15 years in the 1970s. These long time lags could be due to the delocalization of flax processing from Europe to China. This economic transformation led to longer production times.

The determination of these time lags is important to better interpret the 14C dating results for the paintings. Collaboration with the painting conservator specialized in Pierre Soulages’ work gave us the great opportunity to specify the timeline of the flax processing as well as the practice of a 20th century painter. This study provides robust data to better date paintings by the radiocarbon method.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the LMC14 colleagues for their help during sample preparation, graphitization and AMS 14C measurements and Alain Bourmaud from the Université de Bretagne-Sud for fruitful discussion about linen production.