Introduction

Radiotherapy is one of the two main treatment modalities for tumour–node stage T2N0 glottic carcinoma, yielding high rates of both local control and larynx preservation.Reference Hendriksma, Heijnen and Sjögren1 However, because of the high rates of disease control, it is clear that outcome evaluation must include functional outcomes, as patients will generally live out their lives with the handicap the treatment causes. Multidimensional functional parameters such as quality of life (QoL), voice outcome (voice quality, function and performance) and swallowing performance should be included in the appraisal of treatment results.

Although there is a sizeable amount of oncological outcome data available, reported functional outcomes after treatment for T2 glottic carcinoma with radiotherapy are sparse, especially in the long term. Most studies have investigated T1 glottic carcinoma alone, or grouped T1 and T2 tumours together, such that data on T2 tumours are not extractable. The few studies that have reported functional outcomes after radiotherapy in T2 glottic carcinoma patients demonstrate an improvement in post-treatment voice, although parameters do not normalise.Reference Agarwal, Baccher, Waghmare, Mallick, Ghosh-Laskar and Budrukkar2–Reference Al-Mamgani, van Rooij, Woutersen, Mehilal, Tans and Monserez5 Studies also show that radiotherapy can affect the functional outcome after a longer period of time, probably due to progressive fibrosis in the glottic tissue.Reference Ma, Green, Pan, McCabe, Goldberg and Woo6,Reference Naunheim, Garneau, Park, Carroll, Goldberg and Woo7 However, T2 glottic carcinoma comprises a heterogeneous group of tumours with varying extension – some have a large surface area without deep extension, whereas others may have a smaller diameter but penetrate deep into the vocal fold muscle.

To our knowledge, so far only one study has reported outcomes according to tumour extension in T2 glottic carcinoma,Reference Al-Mamgani, van Rooij, Woutersen, Mehilal, Tans and Monserez5 which is of interest when comparing the outcomes of radiotherapy with those of defects created by surgical modalities. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate the long-term functional outcomes in patients who received primary radiotherapy for T2N0 glottic carcinoma at our centre between 2007 and 2016, stratified for tumour extension.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 2019 and April 2019, a cross-sectional study on functional outcomes after treatment for T2N0 glottic carcinoma was performed in the Leiden University Medical Center. The target population of the study was patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma who were treated with radiotherapy between January 2007 and December 2016. Exclusion criteria were: an inability to speak and read Dutch language, treatment for recurrent disease, treatment for other head and neck tumours, and the presence of any cognitive conditions hampering compliance with the study (e.g. dementia).

This study was approved by the Local Medical Ethics Committee (approval code: P18.150) in the Leiden University Medical Center, and all patients signed informed consent forms prior to inclusion in the study.

Treatment and radiology

Radiotherapy was applied with a linear accelerator using a 4–6 MV photon beam. For T2a tumours, the total dose ranged from 60 to 70 Gy (median of 70 Gy), administered in five fractions ranging between 2.0 and 2.4 Gy (median of 2.4 Gy) per week for six weeks. For T2b tumours, the total dose consisted of 70 Gy, administered in five fractions of 2.0 Gy per week for seven weeks. Additionally, patients with T2a tumours received unilateral elective radiotherapy to the neck at levels II, III and IV, consisting of a total dose ranging between 46.0 and 57.75 Gy (median of 54.25 Gy). Patients with T2b tumours received bilateral elective radiotherapy to the neck at levels II, III and IV, consisting of a total dose of 54.25 Gy administered in fractions of 1.55 Gy bilaterally. The field area was 6 × 6 cm. The upper limit was the hyoid bone, the lower limit was the cricoid cartilage, and the skin was the anterior border.

Chronic complications were analysed with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0.

All available pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scans were reviewed by one radiologist (BMV), and scored for superficial spread versus vocal fold muscle infiltration. If tumours were not visible on CT, they were classified as superficial.

Questionnaires

Four self-administrated questionnaires were utilised: the Voice Handicap Index-30,Reference Jacobson, Johnson, Grywalski, Silbergleit, Jacobson and Benninger8 the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‘QLQ-C30’Reference Aaronson, Ahmedzai, Bergman, Bullinger, Cull and Duez9 and ‘QLQ-HN35’Reference Bjordal, Ahlner-Elmqvist, Tollesson, Jensen, Razavi and Maher10 QoL questionnaires, and the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory.Reference Chen, Frankowski, Bishop-Leone, Hebert, Leyk and Lewin11 Patients were asked to complete the questionnaires after the voice recording during their visit to the out-patient clinic.

Voice Handicap Index

The Dutch-language version of the Voice Handicap Index is a validated questionnaire measuring voice problems in daily life.Reference Verdonck-De Leeuw, Kuik, De Bodt, Guimaraes, Holmberg and Nawka12 It consists of 30 questions with 3 subscales (functional, emotional and physical), and it is scored with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total score ranges from 0 to 120, with 120 points indicating a maximal voice handicap. A total score of 15 points or more is taken to indicate voice problems in daily life.Reference Jacobson, Johnson, Grywalski, Silbergleit, Jacobson and Benninger8,Reference Verdonck-De Leeuw, Kuik, De Bodt, Guimaraes, Holmberg and Nawka12

‘QLQ-C30’ questionnaire

The Dutch-language version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 is a validated questionnaire measuring health-related QoL in patients with cancer.Reference Aaronson, Ahmedzai, Bergman, Bullinger, Cull and Duez9 It comprises 30 questions that address patient function and symptomatology over the preceding week. The questionnaire includes: a global health scale; five functional scales (assessing physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning); three multi-item symptom scales, each containing multiple questions on the items of fatigue, pain, and nausea and vomiting; and six single item scales, each containing one single question on the items of dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties. All items are answered on a four-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very much), except for the global health status, which is scored on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 7 = excellent). Calculated scores range between 0 and 100. Depending on the item, a higher score can represent a higher (better) level of functioning or a higher (worse) level of symptoms.

‘QLQ-HN35’ questionnaire

The Dutch-language version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-HN35 is a validated questionnaire that evaluates health-related QoL specifically in head and neck cancer patients.Reference Bjordal, Ahlner-Elmqvist, Tollesson, Jensen, Razavi and Maher10 It consists of 35 questions that address symptoms and side effects of treatment, social function, and body image and sexuality. The questionnaire incorporates 7 multi-item scales (pain, swallowing, senses (taste and smell), speech, social eating, social contact and sexuality) and 11 single items (teeth, mouth opening, dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, feeling ill, analgesic use, nutritional supplement use, feeding tube use, weight loss and weight gain), which are answered on 4-point Likert scales. Calculated scores range between 0 and 100. A higher score represents more severe problems or symptoms.

MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory

The Dutch-language version of the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory is a validated questionnaire that evaluates the impact of dysphagia on QoL.Reference Speyer, Heijnen, Baijens, Vrijenhoef, Otters and Roodenburg13 It comprises 20 questions answered on 5-point Likert scales ranging between 1 (strongly agree) and 5 (strongly disagree). Two questions are scored in the opposite direction, whereby 1 represents ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 reflects ‘strongly agree’. The questionnaire is subdivided into a global score and three subscales (emotional, functional and physical). A higher score indicates higher functioning.Reference Chen, Frankowski, Bishop-Leone, Hebert, Leyk and Lewin11,Reference Speyer, Heijnen, Baijens, Vrijenhoef, Otters and Roodenburg13

Perceptual evaluation

Perceptual analysis was performed using the Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, Strain rating scale on a 30-second running speech sample.Reference Hirano14 The speech sample consisted of a standard phonetically balanced Dutch-language text, ‘80 Dappere Fietsers’ (‘80 Brave Cyclists’). The rating scale comprises five subscales (grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia and strain), of which only the grade was rated. A panel of two experienced speech and language pathologists (including BJH), familiar with the Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, Strain rating scale, who were blinded to all data, conducted the perceptual evaluation. Each speech sample was scored from 0 (normal) to 3 (severely dysphonic); a higher score therefore indicates a more dysphonic voice.Reference Hirano14

Objective evaluation and voice recording

The voice recordings were taken in a noise-free environment, and were acquired at a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz with a dual microphone headset recorder (Alphatron Medical Systems, Rotterdam, the Netherlands) and an Opus 56 microphone (Beyerdynamic, Heilbronn, Germany). The voice parameters consisted of aerodynamic parameters (maximum phonation time) and acoustic parameters (dynamic range, fundamental frequency, percentage jitter, percentage shimmer and harmonics-to-noise ratio). The acoustic parameters were measured with Praat software.Reference Boersma15 The maximum phonation time was determined by measuring the duration of the sustained letter /a/ sound at the most comfortable pitch and loudness. The longest maximum phonation time from two attempts was taken as the representative maximum phonation time. Jitter, shimmer and harmonics-to-noise ratio were measured on a stable 2-second mid-section of the sustained /a/ sound. The dynamic range (in decibels) and the fundamental frequency (in Hertz) were extracted from the patient's phonetogram, recorded with a voice range profile program (2007; Alphatron Medical Systems).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). First, descriptive statistics of the median with range were calculated for all different outcomes. Then, Spearman correlation co-efficients were calculated between the grade and the other voice outcome parameters and between the time to assessment and the different voice outcome parameters. The Voice Handicap Index-30 score was compared between tumours with superficial spread and those with vocal fold muscle infiltration; the Mann–Whitney U test was used to test this difference.

Results and analysis

Patients

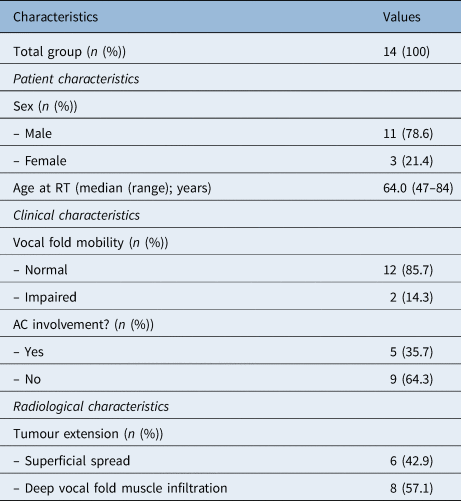

In total, 68 patients were treated with radiotherapy for a T2N0 glottic carcinoma between 2007 and 2016. Forty patients were excluded: 5 patients had disease recurrence and 35 patients died. In total, 28 patients were approached, of whom 14 agreed to participate in this study (response rate of 50.0 per cent). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median time between the start of treatment and assessment was 42 months (range, 26–143 months).

Table 1. Patient characteristics

RT = radiotherapy; AC = anterior commissure

Voice Handicap Index

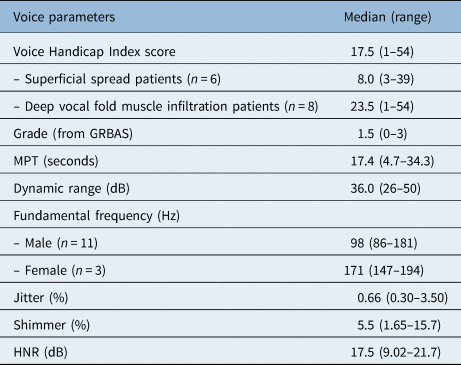

The median Voice Handicap Index-30 score was 17.5, with a range of 1–54 (Table 2). Six of the 14 patients (42.9 per cent) reported a Voice Handicap Index-30 score within the normal range (less than 15 points). The physical subscale showed the highest score with a median of 9.0 (range, 0–22). The emotional and physical subscales showed lower scores, with median values of 6.0 (range, 0–16) and 2.0 (range, 0–16), respectively. Patients with deep infiltration of the vocal fold muscle had a higher Voice Handicap Index-30 score (median of 23.5 (range, 1–54)) than patients with superficial spread (median of 8.0 (range, 3–39)); however, this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.272).

Table 2. Voice outcome parameters

Total n = 14. GRBAS = Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, Strain rating scale; MPT = maximum phonation time; HNR = harmonics-to-noise ratio

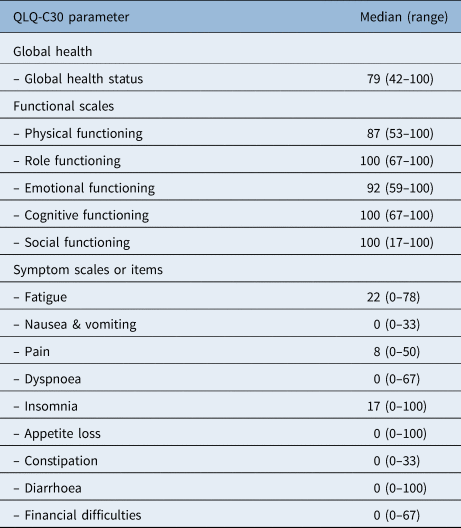

‘QLQ-C30’ questionnaire

Patients showed a good global health status with a median of 79 points at the time of assessment (Table 3). The results of the different functional scales also showed high levels of functioning, ranging between 87 and 100 points. The most frequently reported complaints were fatigue (median of 22 (range, 0–78)) and insomnia (median of 17 (range, 0–100)).

Table 3. Quality of life results according to EORTC ‘QLQ C30’

EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

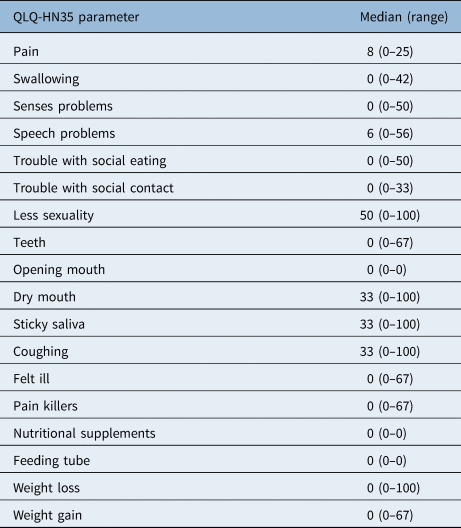

‘QLQ-HN35’ questionnaire

The symptom scale showed low symptom scores (Table 4). After a median of 42 months, the most registered complaints were dry mouth (median of 33 (range, 0–100)), sticky saliva (median of 33 (range, 0–100)), coughing (median of 33 (range, 0–100)) and a decrease in sexuality (median of 50 (range, 0–100)). Notably, few patients complained about speech problems in this questionnaire; the median score of 6 on this item is considered to be low.

Table 4. Quality of life results according to EORTC ‘QLQ-HN35’

EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory

The MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory showed high functioning, with a median score of 95.0 (range, 32–100) (maximum score is 100) (Table 5). In this questionnaire, there was one outlier with a total score of 32. We cannot exclude the possibility that this was caused by a misunderstanding of the instructions, as all other questionnaires indicated a high level of functioning in this individual.

Perceptual evaluation

The median grade of dysphonia was 1.5, with a range between 0 and 3 (Table 2). The voice was scored as normal in three patients (21.4 per cent), as mildly dysphonic in four patients (28.6 per cent), and as moderately dysphonic in six patients (42.9 per cent); the voice of one patient (7.15 per cent) was rated as severely dysphonic. The grade was lower in the patients with deep infiltration of the vocal fold muscle (median of 1.0 (range, 0–2)) than in patients with superficial infiltration (median of 2.0 (range, 0–3)); however, this result was not statistically significant. No correlations were found between the grade and other voice parameters.

Acoustic and aerodynamic parameters

The median values for the different acoustic and aerodynamic parameters are shown in Table 2. The median maximum phonation time was 17.4 seconds (range, 4.7–34.23 seconds). The voice in the patient with the lowest maximum phonation time (4.7 seconds) was so severely dysphonic that the voice range profile software was unable to analyse the voice parameters because of the irregularity of the signal; the other acoustic parameters could not be analysed in this patient either. No correlations existed between assessment time and the different voice outcome measures.

Toxicity

Treatment was not interrupted in any of the patients. In two patients (14.3 per cent), a grade 3 acute adverse event was reported. One patient required a nasogastric feeding tube during treatment for grade 3 dysphagia, and one patient required hospital admission and medication because of grade 3 dyspnoea. Five patients reported late complications of hypothyroidism (35.7 per cent), of whom three were treated with medication. In the two other patients, treatment was not necessary.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study investigated long-term functional outcomes in patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Our results show good long-term results after a median follow up of 42 months. In general, the Voice Handicap Index score was slightly elevated, whereas the perceptual evaluation showed mild to moderate dysphonia. The QoL scores indicated high functioning with low symptom scores, and the swallowing function showed high functioning as well. Patients with vocal fold muscle infiltration showed a trend towards a higher voice handicap than those with superficial spread; however, this finding was not statistically significant. No correlations were found between voice outcome parameters and the time of assessment.

Only a few studies have presented long-term (more than 24 months) functional outcomes after radiotherapy. Only two studies described acoustic and aerodynamic parameters after radiotherapy in T2N0 glottic carcinoma patients.Reference Agarwal, Baccher, Waghmare, Mallick, Ghosh-Laskar and Budrukkar2,Reference Niedzielska, Niedzielski and Toman4 Niedzielska et al. evaluated the phonatory function after one to three years in 11 male patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma.Reference Niedzielska, Niedzielski and Toman4 Their voice outcome parameters (jitter, shimmer, fundamental frequency and maximum phonation time) were comparable with our results. Agarwal et al. analysed the voice quality (jitter, shimmer and minimal intensity) before and after radiotherapy (between three and six months) in 50 patients, of whom 17 had T2 glottic carcinoma.Reference Agarwal, Baccher, Waghmare, Mallick, Ghosh-Laskar and Budrukkar2 We found similar scores for jitter but higher scores for shimmer. This difference might be explained by the fact that they used other testing conditions than ours.

A study by Remmelts et al. investigated the voice outcome with the physical subscale of the Voice Handicap Index-30 questionnaire.Reference Remmelts, Hoebers, Klop, Balm, Hamming-Vrieze and van den Brekel16 They reported a mean score of 9.9 (range, 0–30) on this subscale in 38 patients with T2 glottic carcinoma after a median time of 66 months. Our study revealed a similar score on this subscale after a median follow-up duration of 42 months. Al-Mamgani et al. investigated Voice Handicap Index scores in 223 patients with T1–T2 glottic carcinoma.Reference Al-Mamgani, van Rooij, Woutersen, Mehilal, Tans and Monserez5 The Voice Handicap Index-30 score in patients treated for a T2a tumour after 36 and 48 months was 24.3 and 23.8, respectively. The mean score in patients with T2b tumours after 36 and 48 months was 36.2 and 39.7, respectively, showing that tumours leading to vocal fold movement impairment (T2b) were associated with a higher voice handicap than tumours that did not lead to such impairment. In comparison, both our study and that by Remmelts et al. showed lower Voice Handicap Index scores for patients with T2 tumours treated with radiotherapy.Reference Remmelts, Hoebers, Klop, Balm, Hamming-Vrieze and van den Brekel16 However, in line with Al-Mamgani et al.,Reference Al-Mamgani, van Rooij, Woutersen, Mehilal, Tans and Monserez5 we did find a trend towards higher Voice Handicap Index-30 scores in patients with more deeply infiltrating tumours, which in our case were defined as tumours that infiltrated the vocal fold muscle.

• Reported functional outcomes after treatment for tumour–node stage T2N0 glottic carcinoma with radiotherapy are sparse, especially in the long term

• However, reports demonstrate post-treatment voice improvement

• This study shows good long-term functional outcomes

• Patients with a tumour infiltrating the vocal fold muscle were examined with computed tomography

• Imaging showed a trend toward higher Voice Handicap Index scores than patients with superficial spread

It is possible that our study was positively influenced by the small numbers of participants and the fact that our cohort consisted mainly of T2a tumours (n = 12 (85.7 per cent)). Even if seven (58.3 per cent) of these T2a tumours infiltrated the vocal fold muscle, the vocal fold still showed normal mobility. Therefore, T2b tumours with impaired vocal fold mobility were underrepresented in our cohort. Based on our results, we hypothesise that patients with T2 glottic tumours infiltrating the vocal fold muscle may have a poorer voice outcome, with patients with a T2b tumour and fixated vocal folds having the poorest result. This hypothesis will, however, have to be proven in larger studies. The study of Remmelts et al. did not describe the substage of T2 tumoursReference Remmelts, Hoebers, Klop, Balm, Hamming-Vrieze and van den Brekel16 (these substages are officially no longer part of the American Joint Committee on Cancer StagingReference Brierley, Gospodarowics and Wittekind17) and they only assessed the psychical subdomain of the Voice Handicap Index-30.Reference Remmelts, Hoebers, Klop, Balm, Hamming-Vrieze and van den Brekel16 It is not known whether this subdomain is representative of the total score of the Voice Handicap Index-30.

More data on functional outcomes of different subcategories of T2 tumours in radiotherapy are crucial for an adequate comparison of results with those of other treatment modalities. In surgical studies, for instance those on transoral laser microsurgery, it has long been recognised that T2 glottic carcinomas are a heterogeneous group of lesions, requiring a variety of different types of resection, with varying functional and oncological outcomes.Reference Peretti, Piazza, Mensi, Magnoni and Bolzoni18 Studies show that larger resection types as defined by the European Laryngological Society (European Laryngological Society type IV–VI resections) result in a worse voice outcome compared with superficial resection (European Laryngological Society type I–III resections).Reference van Loon, Sjogren, Langeveld, Baatenburg De Jong, Schoones and van Rossum19,Reference Roh, Kim, Kim and Park20 As the study by Al-Mamgani et al.Reference Al-Mamgani, van Rooij, Woutersen, Mehilal, Tans and Monserez5 and our study indicate, comparing functional outcomes of these different resections with a simple mean or median score for an overall cohort of patients with T2 glottic tumours treated with radiotherapy is probably not adequate when determining the relative merits of the treatments and when counselling patients in therapy choice. Furthermore, it is our opinion that to harmonise outcome studies between modalities, the subcategorisation of tumours and comparison between modalities should be based on clinical and radiological extension of the tumour in addition to vocal fold mobility (T2a or T2b).

Regarding QoL, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‘QLQ-C30’ questionnaire was designed as a general questionnaire for patients with cancer, whereas the head and neck module (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‘QLQ-HN35’) was designed for head and neck cancer patients and is thus more sensitive for specific toxicities and symptoms related to the treatment. To our knowledge, there are no studies that report results with these questionnaires for T2N0 glottic carcinoma specifically.

Two studies that used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HN35 questionnaires included both T1 and T2 glottic carcinoma patients and treated them with radiotherapy,Reference Stoeckli, Guidicelli, Schneider, Huber and Schmid21,Reference Arias, Arraras, Asin, Uzcanga, Maravi and Chicata22 but did not report separately on the two categories. The study by Arias et al. investigated QoL in 59 patients, of whom 10 had T2 tumours.Reference Arias, Arraras, Asin, Uzcanga, Maravi and Chicata22 Their results showed similar elevated QLQ-C30 scores to our results. On the QLQ-HN35 questionnaire, they showed the highest scores on the items of dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, painkiller use and weight gain;Reference Arias, Arraras, Asin, Uzcanga, Maravi and Chicata22 we reported the highest scores for less sexuality, dry mouth, sticky saliva and coughing. Stoeckli et al. investigated QoL in 16 patients with T1 and T2 tumours.Reference Stoeckli, Guidicelli, Schneider, Huber and Schmid21 They did not specify how many patients had T2 tumours. Their study also reported an elevated score for fatigue and insomnia on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C030 questionnaire, and showed the highest scores for dry mouth, sticky saliva and coughing,Reference Stoeckli, Guidicelli, Schneider, Huber and Schmid21 which was similar to our results.

A comparison of our results with normative data from the general Dutch population on the QLQ-C30 questionnaire showed comparable scores, even on the elevated items (fatigue and insomnia).Reference van de Poll-Franse, Mols, Gundy, Creutzberg, Nout and Verdonck-de Leeuw23 Therefore, the question remains whether or not these elevated items are related to the treatment in the long term. Unfortunately, no normative data from the general Dutch population exist for the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-HN35 questionnaire. Therefore, a comparison was performed with a multinational study on 108 patients with newly diagnosed laryngeal cancer (stages I–IV) and 185 disease-free patients after treatment for laryngeal cancer.Reference Bjordal, de Graeff, Fayers, Hammerlid, van Pottelsberghe and Curran24 Elevated scores in our study are comparable to their combined scores (patients undergoing active treatment and disease-free patients); only the sexuality item is higher in our study.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small and T2b tumours were underrepresented. As stated, this may have positively biased our results. Secondly, because of the cross-sectional study design, comparison between pre- and post-treatment findings was not possible. In addition, not all patients were assessed at the same time-point post radiotherapy, although there was a minimum follow up of 26 months, which in our opinion represents a long-term follow up.

Based on our findings, we conclude that patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma treated with radiotherapy show overall good long-term QoL, with low symptom scores and slightly elevated voice outcome parameters, which do not return to normal values after a median follow up of 42 months. Patients with tumours infiltrating the vocal fold muscle show a trend towards a higher voice handicap, which is supported by data in the literature. More studies are needed to investigate (long-term) functional outcomes after treatment for T2 glottic carcinoma, particularly to investigate the effect of tumour extension on functional outcomes after radiotherapy so as to allow a meaningful comparison of results with those of other treatment modalities and enable more accurate counselling of patients.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Mrs VAH van de Kamp for her assistance in the voice evaluation.

Competing interests

None declared