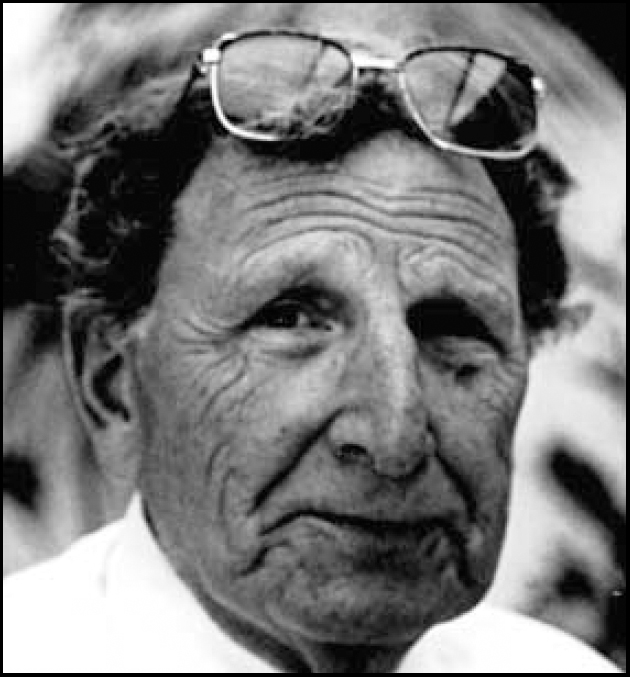

Arthur Shenkin, who died on 25 January 2002, was a pioneer in bringing psychiatry into general hospitals in post-war Glasgow, at a time of much hostility from other hospital doctors to psychiatrists and their patients. A tall man, with a commanding presence, his nature was warm and gentle. With his charm, and great reserves of patience and tolerance, he could calm the most disturbed patients and — much more difficult — awkward colleagues on medical committees.

Born on 1 March 1915 in Glasgow, the son of Latvian Jewish immigrants, he spoke in a medley of three languages in his pre-school years, and always regarded this as a formative influence. He was educated at Hutchesons' Grammar School and Glasgow University where he graduated MBChB in 1942 and elected FRCP (Glasgow) in 1971. In his student days his fierce commitment to socialism and Zionism, and his involvement in the politics of the 1930s, competed with his medical studies. When he qualified in 1942 he served in the Royal Air Force at home and in India, latterly in psychiatry. Demobilised in 1946, he joined the staff of the Southern General Hospital, where he found the psychiatric wards of the former Poor Law Hospital housing some 130 chronically ill patients. In a short time he reorganised the unit, created active treatment wards and opened the first out-patient clinic in the area. The unit thrived to such an extent that, after the NHS was created in 1948, it was chosen to house the new University Department by Glasgow's first Professor of Psychological Medicine, T. Ferguson Rodger. In his 28 years at the Southern, Arthur bore a heavy clinical load, played a full part in teaching and, in what for others would have been leisure time, developed a large private practice. He was interested in the psychological problems of the physically ill and developed services for them in the expanding general hospital. Twenty years later the rest of psychiatry caught up with him and named his activities ‘liaison psychiatry’. In the 1950s he began to instruct ministers in pastoral psychology, another innovation, which developed over the years into a regular undergraduate course in the Faculty of Theology. He was rightly proud of his respected status there. Before he retired in 1976 he had helped to secure the Walton Conference Suite for the hospital and had chaired many of its committees. Retirement for him meant continuing work until the century ended. He became a tutor in psychotherapy at Dykebar Hospital, Paisley, continued his private practice and expanded his medico-legal work. He was in demand as an expert witness in the courts until his late 70s. He lectured extensively and was president of the Glasgow Royal Philosophical Society from 1996 to 1998. He was a man of wide interests and a great and combative talker, with a fund of stories and proverbs that he deployed effectively both in company and the consulting room. He was an authority on the prophet Hosea, and over many years wrote and rewrote an epic poem in Scots on the theme of the Creation, in which God featured as a woman. This amusing and original work was acclaimed by the many learned societies to which he delivered excerpts. He remained a socialist throughout his life, and never lost his loyalty to the cause of Israel. Through all these years he was sustained by, and devoted to, his wife Lillian, also a full-time doctor, and his three daughters. He took pride in his growing band of talented grandchildren, and lived to see one of them a consultant physician. In old age he recovered completely from a fractured neck of femur and major surgery on an aortic aneurysm. He died full of years, clear-minded to the end, after a life well-lived.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.