1. Introduction

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a prevalent psychiatric condition, associated with high disability and poor social functioning [Reference Grande, Berk, Birmaher and Vieta1]. This condition affects about 2.4% of the adult population lifetime if the broader definition of bipolar spectrum disorders is considered [Reference Merikangas, Jin, He, Kessler, Lee and Sampson2], and, although prevalence rates may be different between countries for methodological issues [Reference Moreira, Van Meter, Genzlinger and Youngstrom3], severity and impact of BD are similar internationally [Reference Merikangas, Jin, He, Kessler, Lee and Sampson2]. In Italy about 3% of the general population seems to suffer of a bipolar spectrum disorder [Reference Carta, Aguglia, Balestrieri, Calabrese, Caraci and Dell’Osso4]. BD has a tremendous impact on patients’ and caregivers’ lives and it has been associated with high rates of divorces and volatility of social relationships [Reference Granek, Danan, Bersudsky and Osher5]. Clinical management of patients with BD can be challenging in light of frequent juvenile onset [Reference Baldessarini, Bolzani, Cruz, Jones, Lai and Lepri6], misdiagnosis with other psychiatric diagnoses (especially major depression and psychotic disorders) [Reference Altamura, Buoli, Caldiroli, Caron, Cumerlato Melter and Dobrea7] and high suicidal risk [Reference Arici, Cremaschi, Dobrea, Vismara, Grancini and Benatti8].

Several clinical factors have been associated with poor outcome of patients with BD including early onset [Reference Connor, Ford, Pearson and Scranton9], elderly status [Reference Almeida, Hankey, Yeap, Golledge and Flicker10], long duration of illness [Reference Altamura, Serati and Buoli11], long duration of untreated illness [Reference Drancourt, Etain, Lajnef, Henry, Raust and Cochet12], lifetime presence of psychotic symptoms [Reference Ostergaard, Bertelsen, Nielsen, Mors and Petrides13–Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Cremaschi, Dobrea, Buoli and Ketter15] or rapid-cycling (RC) [Reference Fountoulakis, Kontis, Gonda and Yatham16], while the role of other variables, such as gender, on BD outcome is still controversial [Reference Buoli, Cesana, Dell’Osso, Fagiolini, de Bartolomeis and Bondi17]. Of note, RC, defined by at least 4 mood episodes over a 12-month period, is reported by a significant part of patients with BD [Reference Carvalho, Dimellis, Gonda, Vieta, Mclntyre and Fountoulakis18] and different factors have been reported to increase the risk of RC in BD, including early age at onset [Reference Valentí, Pacchiarotti, Undurraga, Bonnín, Popovic and Goikolea19] and tricyclic antidepressant treatment [Reference Carvalho, Dimellis, Gonda, Vieta, Mclntyre and Fountoulakis18]. Some authors argue that RC can be a transient phenomenon of patients with BD [Reference Bauer, Beaulieu, Dunner, Lafer and Kupka20] and that treatment with antidepressants may worsen its outcome over the course of BD [Reference El-Mallakh, Vöhringer, Ostacher, Baldassano, Holtzman and Whitham21]. Of note, RC patients with BD (RCBD) were found to have more mood episodes, suicide attempts [Reference Gigante, Barenboim, Dias, Toniolo, Mendonça and Miranda-Scippa22], and more frequent comorbidity with obesity [Reference Buoli, Dell’Osso, Caldiroli, Carnevali, Serati and Suppes23] and diabetes [Reference Ruzickova, Slaney, Garnham and Alda24] than subjects affected by non-rapid cycling BD (NRCBD). Associated unfavourable clinical features and frequent medical comorbidity both contribute to the poor psychosocial functioning of RC patients, especially in terms of work impairment [Reference Reed, Goetz, Vieta, Bassi, Haro and EMBLEM Advisory Board25].

Pharmacotherapy may be less effective in RC than in NRC patients with BD, making long-term stabilization of these subjects particularly difficult [Reference Suppes, Brown, Schuh, Baker and Tohen26]. Patients with RCBD may benefit of combined pharmacotherapy [Reference Buoli, Serati and Altamura27], or of augmentative psychological or biological approaches to pharmacological treatment [Reference Papadimitriou, Dikeos, Soldatos and Calabrese28], but available data are far to be conclusive about this topic [Reference Fountoulakis, Kontis, Gonda and Yatham16]. Overall, RCBD appears to be a subtype of illness associated with worse outcome, potentially characterized by more severe biological abnormalities. More specifically, patients with RCBD (compared to NRCBD) seem to present more oxidative stress and a higher susceptibility to hypothyroidism and insulin resistance [Reference Buoli, Serati and Altamura29].

Taken as a whole, different clinical factors may contribute to the overall severity of RCBD compared to NRCBD, some of which are still controversial, such as early age at onset [Reference Joslyn, Hawes, Hunt and Mitchell30]. The search or the confirmation of clinical predictors of RC is motivated by the possibility of implementing specific prevention strategies that avoid the onset of this more severe form of illness, and by the elaboration of personalized treatments for these patients. In this framework, the purpose of the present study was to investigate, in a large representative sample of Italian patients with BD, a wide series of socio-demographic and clinical features common to and differentiating RCBD and NRCBD patients, with the aim to identify factors that may favor an early diagnosis and a personalized treatment for patients with RCBD.

2. Methods

A total sample of 1675 patients with BD, corresponding to 83.8% of a target considered as optimal in the planning phase of the exploratory survey, was enrolled from different Italian psychiatric clinics in the context of RENDiBi project (National Epidemiological Research on Bipolar Disorder). The data have been collected for patients consecutively afferent to the different clinics between 1st April 2014 and 31st March 2015. The included Italian centres were the following: Milan-Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico; Genoa-Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Turin-S. Luigi Gonzaga; Bozen-Inpatient and Outpatients Clinics; Naples-Second University (SUN); Siena-Inpatient Clinic; Pisa-Inpatient Clinic; Rome-Tor Vergata; Bari-Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Naples- Federico II; Foggia-Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Turin-Molinette; Rome-Sant’Andrea Hospital; Rome-San Camillo Hospital; Rome-Community Outpatient Clinic; Rome-Gemelli Hospital; Bergamo- Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Bra-Private Inpatient Clinic; Varese- Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Messina-Inpatient and Outpatient Clinics; Perugia-Inpatient Clinic ; Pesaro-Inpatient Clinic; Cuneo- Inpatient Clinic; Biella-Inpatient Clinic.

The protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committees. Patients were diagnosed as affected by BD according to DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) criteria [Reference American Psychiatric Association31].

Diagnoses were made by expert psychiatrists, who had regularly followed up the interviewed patients, and confirmed by the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview [Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller32, Reference Buoli, Cesana, Barkin, Tacchini and Altamura33]. Patients consecutively presenting at outpatient or inpatient services were selected for the purpose of the study.

Clinical information was obtained through a review of the clinical charts and clinical interviews with patients and available relatives. Data were entered into an electronic central database (electronic Case Report Form: e-CRF). Collected data included the following socio-demographic and clinical variables divided in three clusters:

- cluster 1 (socio-demographic variables): age, gender, education, employment, marital status (at least 1 lifetime marriage or partnership), living alone;

- cluster 2 (lifetime clinical variables): age at onset of BD, age at first pharmacological prescription (including benzodiazepines), age at first contact with psychiatric services, first psychiatric diagnosis, family history of psychiatric disorders (fathers and mothers), age at first psychiatric diagnosis, age at first diagnosis of BD, age at first being prescribed mood stabilizer/atypical antipsychotic, duration of illness, duration of untreated illness, polarity of first episode, lifetime number of manic episodes, lifetime number of depressive episodes, prevalent polarity;

- cluster 3 (clinical variables-last year of observation): type of current episode, number of hypomanic/manic episodes, number of depressive episodes, presence of psychotic symptoms, presence and number of attempted suicides and the degree of lethality, comorbidity with substance use disorders, presence of hospitalizations, presence of insight, attribution of symptoms to a psychiatric disorder, current pharmacological treatment, treatment adherence, number of visits, administration of psychoeducational interventions (according to Colom’s model) [Reference Vieta, Pacchiarotti, Valentí, Berk, Scott and Colom34].

Duration of untreated illness was considered as the time between first episode of BD and the prescription of a proper pharmacological treatment (mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic with stabilizing effects) [Reference Altamura, Buoli, Caldiroli, Caron, Cumerlato Melter and Dobrea7, Reference Buoli, Serati and Altamura27].

Prevalent polarity was evaluated according to the Barcelona proposal and it was then defined as at least two-thirds (2/3) of the total number of past episodes being from the same polarity [Reference Colom, Vieta and Suppes35].

Lethality of suicide attempts was rated according to global impression of Scale for Assessment of Lethality of Suicide Attempt (score 1–2: low; score 3: medium; score 4-5: high) [Reference Kar, Arun, Mohanty and Bastia36].

Exclusion criteria included: 1) patients who had not been screened in the last 12 months making it impossible to collect data of cluster 3 variables (last year of observation); 2) patients whose clinical information were incomplete; 3) patients with a diagnosis of dementia, mental retardation or other medical conditions (e.g. thyroid disease) potentially associated with an increased risk of RC [Reference Lorenzo Gómez, Cardelle Pérez and De Las Heras Liñero37].

The sample size of this cross-sectional study has been calculated in order to have a satisfactorily precision of estimates taking into account the power (0.80) of binomial tests against expected values ranging from 0.05 and 0.30 or 0.70 and 0.95, carried out at a significance level of 0.05. In the current case of a very big sample size unbalanced between the two groups, there is “a posteriori” power of more 0.80 for demonstrating a difference of 0.14 from a baseline of 0.50 at a chi-squared test carried out at a significance level of 0.05; in addition, the difference decreases at increasing values of the baseline. Furthermore, with the current sample sizes it is possible to demonstrate at a power of 0.80 an effect size of at least 0.3 at a Student’s t-test carried out at a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed).

Descriptive analyses of the total sample were performed. The total sample was then divided in two groups according to the current presence of RC according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, consisting in the presence of at least 4 mood episodes over a 12-month period [Reference American Psychiatric Association31]. We chose to consider the current presence of RC (in the last year) since, as mentioned before, this phenomenon seems to be transient [Reference Bauer, Beaulieu, Dunner, Lafer and Kupka20]. The two groups were compared for the abovementioned variables by t-tests for quantitative variables and chi-square tests for qualitative ones.

Owing to the large number of variables statistically related to the dependent variable (the presence of current RC) at the univariate analyses, preliminary multiple logistic regression analyses (one for each of the abovementioned clusters) were performed including only statistically significant variables. Finally, statistically significant variables from these final models were inserted in a new global starting multivariable logistic regression model to obtain the variables independently associated with the presence of current RC. Age, despite a statistically non-significant variable at univariate analysis, was inserted in the final model because the likelihood of developing rapid-cycling increases with the duration and chronicity of BD [Reference Altamura, Serati and Buoli11, Reference Maj, Magliano, Pirozzi, Marasco and Guarneri38].

The selection of the variables was done according to a backward procedure; the goodness of fitting was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by SAS® 9.2 version.

3. Results

The total sample included 1675 patients: 714 males (42.6%) and 961 females (57.4%). Overall, 128 patients of the total sample presented current RC (7.64%). Patients had an age between 18 and 80 (mean: 48.61 ± 13.44). Descriptive analyses of the total sample and groups divided according to the presence of current RC are reported in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1 Socio-demographic variables of the total sample and of the two groups divided according to the presence of current rapid-cycling.

Standard deviations are reported into brackets for the variable “age”.

In bold statistically significant p resulting from χ2 and from unpaired Student’s t-test for the variable “age”.

* Age is referred to the time of inclusion in the study.

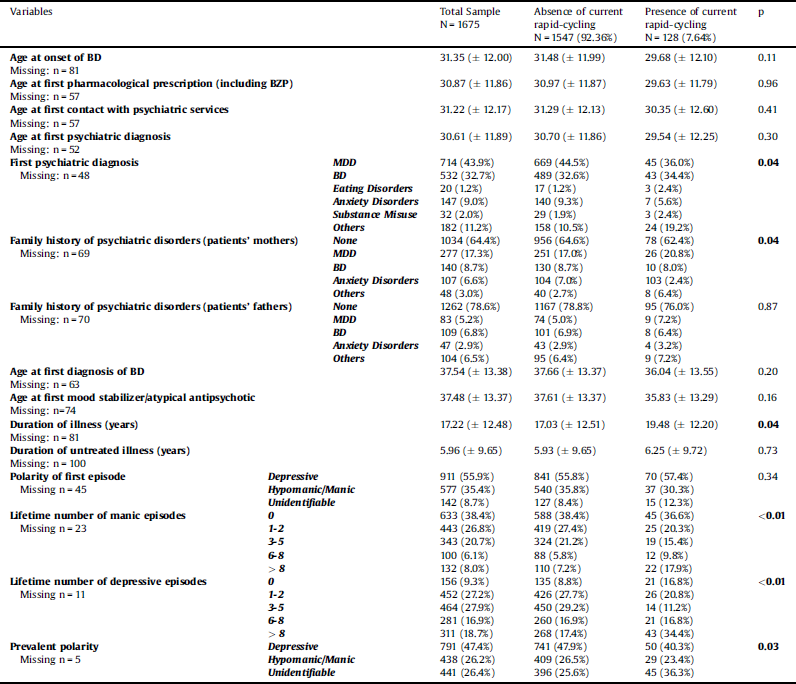

Table 2 Clinical variables of the total sample and of the two groups divided according to the presence of current rapid-cycling.

Standard deviations are reported into brackets.

In bold statistically significant p resulting from χ2 or unpaired Student’s t-test.

BZP: benzodiazepines.

BD: Bipolar Disorder.

MDD: Major Depressive Disorder.

Table 3 Clinical variables of the total sample and of the two groups divided according to the presence of current rapid-cycling (last year of observation).

In bold statistically significant p resulting from χ2 or unpaired Student’s t-test.

Standard deviations are reported into brackets.

RC versus non-RC patients resulted to be more frequently of female gender (p = 0.03) and to have more frequently: a first diagnosis of BD, family history of psychiatric disorders and specifically of Major Depressive Disorder (patients’ mothers) (p = 0.04), comorbid eating disorders and substance misuse (p = 0.04), a longer duration of illness (p = 0.04), a lifetime number of manic (p < 0.01) or depressive episodes (p < 0.01) > 6, an unidentifiable prevalent polarity (p = 0.03), history of psychotic symptoms in the last year (p < 0.01), a higher number of suicide attempts in the last year (p < 0.01), poor insight (p < 0.01), and positive history of at least one hospitalization in the last year (p < 0.01). In addition, patients with RC had less frequently a current treatment with mood stabilizers (p = 0.03) and antidepressants (others than tricyclic ones) (p = 0.02).

The results of the goodness-of-fit-test (Hosmer and Lemeshow Test: χ2 = 2.28, df = 8, p = 0.97) showed that multivariable logistic regression model including socio-demographic/clinical variables as possible predictors of the current presence of RC was reliable. Of note, patients with RC versus non-RC subjects resulted: to be less frequently of male gender (OR = 0.64, p = 0.04), to have more frequently no lifetime depressive episodes than a lifetime number of depressive episodes between 1 and 5 (0 versus 1–2 episodes: OR 2.87, p < 0.01; 0 versus 3–5 episodes: OR = 5.29, p < 0.01), to have less frequently no lifetime manic episodes than more than 6 lifetime manic episodes (OR = 0.57, p = 0.06, borderline statistical significance), to present more frequently an unidentifiable prevalent polarity than a depressive (OR = 1.76, p = 0.02) or hypomanic/manic one (OR = 2.86, p < 0.01), to be more frequently hospitalized in the last year (no hospitalizations versus at least 1 hospitalization: OR = 0.63, p = 0.02) (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Table 4 Summary of the statistics for the best-fit multivariable logistic regression model applied (variables associated with current presence of rapid-cycling).

In this analysis the dependent variable was current presence of rapid cycling. With regard to age, the odds ratio means the increase of the relationship at each unity increase.

Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ2 = 2.28, df = 8, p = 0.97.

Vs = versus; NA = not applicable; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval; p = significance p-values.

In bold statistically significant p-values.

* borderline statistically significant.

Fig. 1. Frequency of at least one hospitalization in the last year of observation between rapid-cycling and non-rapid cycling patients.

4. Discussion

The first relevant epidemiologic finding of the present large-sample multicentric study is represented by the current prevalence of RC in BD, which was found to be 7.65% of the overall sample. This figure is inferior to those reported in other papers [Reference Kupka, Luckenbaugh, Post, Leverich and Nolen39], but this can be explained by different reasons including the type of assessment of RC (e.g. current versus lifetime), the way of selection (e.g. in general medicine services or psychiatry clinics or community) or the tools used to make diagnosis (e.g. MINI versus CIDI- Composite International Diagnostic Interview) [Reference Lee, Tsang and Kessler40].

The results of the present manuscript confirm that the current presence of RC in BD is associated with a series of unfavourable characteristics, including: a longer duration of illness, more lifetime manic episodes (≥ 6), a higher recent number of depressive and hypomanic episodes, a higher number (but not the presence) of recent suicide attempts, a higher frequency of psychotic symptoms (in the last year) and of family history of psychiatric disorders (patients’ mothers), poor insight and a higher frequency of recent hospitalization (in the last year). The results are even more robust (having been confirmed by multivariable regression model) regarding the association between RC with female gender and recent hospitalization (in the last year).

The association between RC and a longer duration of illness has been reported in other socio-cultural contexts [Reference Gigante, Barenboim, Dias, Toniolo, Mendonça and Miranda-Scippa22, Reference Kupka, Luckenbaugh, Post, Suppes, Altshuler and Keck41], supporting the hypothesis of some authors that consider RC a transient phenomenon [Reference Buoli, Cesana, Dell’Osso, Fagiolini, de Bartolomeis and Bondi17–Reference Valentí, Pacchiarotti, Undurraga, Bonnín, Popovic and Goikolea19, Reference Coryell, Endicott and Keller42] which could be more frequent in the advanced stages of illness. In this sense, RC could be considered a clinical marker of chronicity [Reference Carvalho, Dimellis, Gonda, Vieta, Mclntyre and Fountoulakis18] rather than a variable of poor prognosis of subjects with recent onset of illness.

It is not surprising that patients with RC present more family history for psychiatric disorders only on the maternal side, as mothers are those who transmit more genetic material to the offspring through mitochondrial DNA [Reference Buoli and Caldiroli43]; the interesting result is that mothers with MDD, but not BD would appear to confer vulnerability to RC in offspring affected by BD. This finding should be interpreted with caution, taking also into account that female gender is more vulnerable to both RC and MDD [Reference Serra, Koukopoulos, De Chiara, Napoletano, Koukopoulos and Curto44], and this aspect could have contributed to a significant result for mother and not fathers. However, the higher probability of MDD in mothers of RC patients is in agreement with previous studies reporting more frequent family history of BD [Reference Vieta, Calabrese, Hennen, Colom, Martínez-Arán and Sánchez-Moreno45] or Panic Disorder [Reference MacKinnon, Zandi, Gershon, Nurnberger and DePaulo46] in RC versus NRC patients, supporting the view that this subtype of BD would be expression of a more prominent predisposition to psychiatric conditions.

Different studies have reported no association of psychotic symptoms with RC [Reference Vieta, Calabrese, Hennen, Colom, Martínez-Arán and Sánchez-Moreno47, Reference Azorin, Kaladjian, Adida, Hantouche, Hameg and Lancrenon48], differently of what was found in our sample. However, it needs to be highlighted that the statistical significance of this variable did not persist in the final model, and that this result can be due to the type of assessment of psychotic symptoms (lifetime versus current) and/or to the fact that in our and other samples [Reference Aedo, Murru, Sanchez, Grande, Vieta and Undurraga49] RC patients presented more manic episodes compared to NRC individuals. A higher number of suicide attempts in RC versus NRC patients has been previously reported by European [Reference Valentí, Pacchiarotti, Undurraga, Bonnín, Popovic and Goikolea19, Reference Garcia-Amador, Colom, Valenti, Horga and Vieta50] and extra-European studies [Reference Gigante, Barenboim, Dias, Toniolo, Mendonça and Miranda-Scippa22, Reference Bobo, Na, Geske, McElroy, Frye and Biernacka51]. Of note, female gender has been associated with suicide attempts in RC patients [Reference Gao, Tolliver, Kemp, Ganocy, Bilali and Brady52], supporting the hypothesis of a crucial role of sex hormones on the clinical course of BD [Reference Sher, Grunebaum, Sullivan, Burke, Cooper and Mann53]. Similarly, a higher presence of poor insight in RC versus NRC subjects has been reported by other authors [Reference Jawad, Watson, Haddad, Talbot and McAllister-Williams54], this aspect being consistent with the supposed long duration of illness and more advanced staging of this subtype of patients [Reference Kapczinski, Dias, Kauer-Sant’Anna, Frey, Grassi-Oliveira and Colom55]. Finally, subjects with RC resulted to receive less frequently a current treatment with mood stabilizers and antidepressants. This result is in agreement with previous literature that reports less efficacy of lithium in RC versus NRC patients [Reference Coryell, Solomon, Turvey, Keller, Leon and Endicott56] and a potential role of antidepressants in the development and worsening of RC [Reference Gitlin57].

The two most robust results of the present manuscript, remaining statistically significant in the final multivariable model, are the associations of RC with female gender and recent hospitalization. Indeed, a higher frequency of RC in women than men is one of the most replicated findings across studies about this topic [Reference Kilzieh and Akiskal58]. Different hypotheses have been formulated about the association of female gender with RC, including the fact that some risk factors for RC are more prevalent in women than in men, such as cyclothymia [Reference Kilzieh and Akiskal58] or suicidal ideation [Reference Valentí, Pacchiarotti, Undurraga, Bonnín, Popovic and Goikolea19]. Other authors have hypothesized that female gender is more susceptible to RC as a result of higher frequency of BD type 2 in women than men [Reference Kupka, Luckenbaugh, Post, Leverich and Nolen39, Reference Erol, Winham, McElroy, Frye, Prieto and Cuellar-Barboza59]; however, a previous analysis on our sample about differences between patients with BD 1 versus 2 did not reveal a significant association of type of cycling with bipolar subtype [Reference Altamura, Buoli, Cesana, Dell’Osso, Tacchini and Albert60]. Finally, the result of a higher frequency of recent hospitalization in RC versus NRC subjects is of clinical interest, as it stresses how pharmacological stabilization of these patients can be challenging [Reference Suppes, Ozcan and Carmody61] and that this particular subtype of BD requires careful monitoring to avoid social impairment and elevated costs associated with frequent hospitalization [Reference Gianfrancesco, Rajagopalan, Goldberg and Wang62].

Taken as a whole, the results of the present manuscript would confirm that RC can be considered a marker of more advanced staging of illness and that RC patients require careful clinical monitoring to prevent recurrent hospitalization also in the light of a more frequently observed poor compliance. These findings are in agreement with previous literature. Finally, female gender is at risk of RC and women affected by BD should receive a personalized treatment aimed to guarantee clinical stabilization. Future research would investigate the interconnection between different variables associated with BD outcome such as suicidal ideation, female gender and RC.

These limitations of the present research article need to be taken into account:

1) the different settings of care (in several Italian regions) may have impacted on the clinical features of the sample (e.g. the availability of psychoeducation to improve insight of patients with BD);

2) some data were collected retrospectively (e.g. number of mood episodes) and they might have not been always as accurate as in controlled studies;

3) the lack of a prospective monitoring due to the cross-sectional nature of the study;

4) the limited number of RC patients;

5) the impossibility to extrapolate data for the single pharmacological compounds (e.g. lithium);

6) the lack of complete information about family history of psychiatric disorders;

7) patients received a treatment which might have influenced some clinical features (e.g. some compounds might be more effective in the clinical stabilization of RC patients) [Reference Fountoulakis, Kontis, Gonda and Yatham16]. With regard to the last point it has been highlighted that in our sample the only compounds that resulted to be differently prescribed in the two groups in the last year were mood stabilizers and antidepressants (other than tricyclics). Antidepressants were more frequently prescribed in patients without rapid-cycling so that the administration of these compounds has not massively influenced the main results of this research (the association of RC with female gender and recent hospitalization). Mood stabilizers have a comparable effect on RC [Reference Fountoulakis, Kontis, Gonda and Yatham16]; olanzapine and aripiprazole are reported to be promising in the long-term treatment of patients with RC [Reference Fountoulakis, Kontis, Gonda and Yatham16], we have no information about the administration of single compounds, however the groups divided according to the presence of RC did not present a statistically significant difference in the frequency of prescription of antipsychotics.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by local Ethics Committee

Declaration of Competing Interest

None with the present manuscript

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the centers that have given the availability to participate in this study. Herein a list of collaborators:

- Prof Mario Amore, University of Genoa.

- Prof Antonello Bellomo, University of Foggia.

- Prof Alessandro Bertolino, University of Bari.

- Dr. Emi Bondi, Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo.

- Prof Andrea de Bartolomeis, University of Naples "Federico II".

- Dr Marco Di Nicola, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome.

- Dr Guido Di Sciascio, University of Bari.

- Prof Silvana Galderisi, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples.

- Prof Maurizio Pompili, Sant'Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome.

- Prof Paola Rocca, University of Turin.

- Prof Emilio Sacchetti, University of Brescia.

- Prof Gabriele Sani, Sapienza University of Rome.

- Prof Alberto Siracusano, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”.

- Prof Alfonso Tortorella, University of Perugia.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.