Introduction

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the military are easily depicted in antagonistic terms, as if they are enemies who are unlikely to be on speaking terms. Although it is increasingly recognised that they can meaningfully and constructively interact in conflict theatres,Footnote 1 the idea of NGOs and the military being at best ‘strange bedfellows’ remains.Footnote 2 Civil-military relations scholars have devoted much effort to studying how the democratic principle that civilians should always remain the political master of the military is being upheld.Footnote 3 However, in the study of civilian control of the use of military force by consolidated democracies, NGOs have so far mainly featured as peripheral actors. There is a tendency in this literature to focus heavily on state actors and institutions. For instance, although long considered an executive-dominated branch, research on the role of parliaments in overseeing the executive and the armed forces has mushroomed in the past decade.Footnote 4 Yet, the dominant ‘politicians vs the military’ approach in the study of civilian control of the use of military force tends to miss the potential influential role to be played by NGOs and civil society in making the use of force more democratically accountable.

Surprisingly, the field of NGO studies has also remained remarkably silent on the role that NGOs can play in security and defence policy, despite the common qualification of NGOs as ‘watchdogs’ in transnational politics.Footnote 5 Those interested in this domain have mainly studied how NGOs can contribute to activities in the field, such as by providing humanitarian assistance or empowerment,Footnote 6 or have focused on NGOs’ role in international organisations and armaments treaty making.Footnote 7 How they might affect domestic aspects of security and defence policy remains largely unexplored.Footnote 8 Moreover, we know that there is a trade-off between military effectiveness and transparency. While secrecy and confidentiality procedures are inherent to an effective security and defence policy, they can also be obstacles to enforcing accountability of the use of force. A diligent system of democratic accountability requires at least a certain level of transparency and information sharing. Yet, we know little of how NGOs can play a role in enforcing accountability around the use of force.

In this article, we follow the idea that NGOs and the military can work together and push aside their organisational, cultural, and value differences. Rather than focusing on their interaction within conflict theatres, however, we study how NGOs can directly access defence administrations in their home countries. We understand NGOs as ‘private, self-governing, not-for-profit organisations that are geared to improving the quality and sustainability of life’.Footnote 9 More concretely, we focus on international NGOs that advocate for transparency about the use of military force, as this is where the antagonism tends to be most outspoken. We use the term ‘defence administrations’ to refer broadly to defence decision-makers, including the civilian (the Ministry of Defence, MoD) and military officials involved in decision-making in consolidated democracies on the use of force abroad.

We explore how and under what conditions NGOs gain direct access to defence administrations to advocate for transparency about the use of force and civilian harm. Taking a resource exchange approach, we expect that NGOs can gain direct access to defence administrations by proving their ability to provide useful technical information. Yet, the defence administration's demand for this information is dependent on politicisation, which makes it feel that there is a need for increased legitimacy that can be gained by reaching out to these NGOs. In other words, access is ultimately a matter of supply and demand. The domestic focus in this article means that gaining access to the military implies consent from the civilian defence administration, as the civilian side is generally in control of military action in consolidated democracies. Empirically, we focus on Airwars, an international NGO that consolidates and shares data on air strikes by the US-led military coalition against Daesh in Iraq and Syria and campaigns for transparency about civilian casualties. More specifically, we study Airwars’ activities in the Netherlands, as this is a typical case of a country where NGOs managed to establish a working relationship with the Ministry of Defence, here including the Directorate of International Affairs and military staff, to improve transparency. Although it is a single case, it therefore provides important within-case variation on the outcome of access to the defence administration.

The findings of this article will contribute to the civil-military relations literature and the field of NGO studies. First, we offer insights into how and when third parties outside of the political branch can inform civilian control of the military. Second, we add to existing knowledge about NGO-military relations by looking at their relationship outside of the conflict theatres from a resource dependency perspective. And finally, we expand the NGO literature to a field that has so far been ignored. Moreover, this research also has significant social relevance: discussions about transparency around the use of force and civilian harm cut to the core of questions about civilian control over the military. The consequences for governments whose missions are not supported by the population can be highly visible, as demonstrated by European protests over the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. As NGOs have a unique position in policymaking as the voice of civil society, understanding how they play a role in pushing for transparency can indicate the extent to which the public are implicated in discussions of transparency and accountability regarding the use of force.

Civilian control by whom?

The use of force is only one aspect of the wide spectrum of military affairs and defence policy. Yet, as a matter of life and death, it is the one that attracts most attention. Civil-military relations scholars have studied extensively who controls the armed forces and their activities, and how this control takes place.Footnote 10 However, when studying civilian control of the use of military force abroad by consolidated democracies, it is remarkable to see an almost unique focus on domestic state institutions. A major share of this literature is devoted to better understanding the way in which national parliaments attempt to control military troop deployments and oversee the use of force.Footnote 11 National parliaments are the main fora where the executive is seen to be held accountable for the use of military force.

Military affairs are characterised by secrecy and confidentiality procedures, meant to safeguard matters of national security, protect forces in the field, and guarantee military flexibility. However, it is here that the shoe often pinches when it comes to guaranteeing democratic accountability.Footnote 12 Secrecy requirements and confidentiality procedures risk creating information asymmetries that can affect parliaments in their capacity to control and hold accountable the executive for the use of force.Footnote 13 While it is generally agreed that some level of secrecy is required for an effective security and defence policy, information asymmetries can tilt the balance in favour of the executive's discretion. At worst, this can even lead to situations where military force can be used without political scrutiny.

Despite being largely ignored in the study of civilian control of the use of force abroad, one may expect a valuable contribution from NGOs in mitigating this trade-off between military effectiveness and transparency. For instance, it is an ongoing academic debate as to whether politicians are vulnerable to public opposition and the prospect of elections when deciding on military troop deployment or withdrawal.Footnote 14 Likewise, while there is increased scholarly attention to how operational experiences may affect military role conceptions and their relation to civilian authorities,Footnote 15 how societal calls for transparency might affect their idea of civilian control remains so far underexamined. In a reflection on civil-military relations in the United States, Risa A. Brooks recently raised the critique that prevailing norms of military professionalism tend to foster ‘within the military an aversion to civilian oversight of battlefield activity’.Footnote 16 She convincingly calls for updating the conception of military professionalism to address contemporary challenges of politicisation and partisanship. Yet, how civil society may contribute to the politicisation of the military or how openness to calls for improving transparency practices may affect the military's legitimacy and effectiveness remains out of focus. NGOs nonetheless play a signalling function in other domains, acting as eyes and ears on the ground and the mouthpiece of public concerns. And without sufficient direct access to information, parliaments rely on fire alarms, in the form of signals by citizens, organised interest groups, or other third actors.Footnote 17 NGOs inform politics, and it is unlikely that this would be different in the domain of military affairs.

NGOs and transparency campaigns

Yet, how NGOs target militaries and executives in defence policy remains unexplored. This is surprising, given that NGOs have often been described as ‘watchdogs’ in environmental policy and human rights, where they campaign for government accountability by bringing cases to court over violations of international or domestic law.Footnote 18 Transnational NGO networks also play such a role, providing alternative sources of information and using it to hold governments accountable.Footnote 19 Such information, often gathered from organisations’ experience on the ground,Footnote 20 can in turn be exchanged for access to international organisations.Footnote 21 NGOs strategically select the targets for this information, based on their limited resources and the opportunities that arise.Footnote 22 This ‘information politics’ is used in combination with their other activities, including naming and shaming.Footnote 23

Despite this, NGOs’ roles in defining or shaping domestic security and defence policy in consolidated democracies remain underexamined.Footnote 24 The rare studies on the roles of NGOs in these domains have fallen into two main categories: NGOs’ participation in implementing civil-military missions on the ground,Footnote 25 and NGOs’ role in facilitating international peace treaties and agreements.Footnote 26 Although some of these studies include domestic aspects as key variables, including domestic political opportunity structuresFootnote 27 or institutions,Footnote 28 the dominant focus on international NGOs and cooperation among states means that NGOs’ role in consolidated democracies that engage in the use of force abroad remains unexplored. This is surprising, considering the finding that the presence of international NGOs in conflict zones can reduce civilian harm in air strikes,Footnote 29 as well as the growing literature on (international) NGOs in policymaking more generally.Footnote 30 Of course, NGOs are not always positive contributors to the political system, and their own accountability and transparency is not guaranteed.Footnote 31 For this reason, it is important to look at the individual resources that a particular NGO can provide.

Interestingly, there is a group of NGOs that campaign for transparency on these sensitive military issues and seem to bring credible resources to the table. In addition to more generalist, international humanitarian NGOs that add the use of force in military affairs to their broader agenda, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, several NGOs specialise in protecting civilians and vulnerable populations in conflict and particularly push for transparency around the use of military force. For instance, the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) has been active on the subject in the US and internationally since 2003, while the Europe-based international NGO Airwars has been active since 2014. These NGOs regularly contact militaries and have had several successful campaigns working with military and governments to reform transparency provisions – a surprising finding, given the general disinclination for military-NGO cooperation.

For instance, PAX Protection of Civilians has in recent years repeatedly offered trainings to military officials (including officials of the Netherlands and at NATO HQ) to develop and implement security interventions that pay closer attention to civilian harm and civilian protection.Footnote 32 CIVIC has not only collaborated with national armed forces in Nigeria and Afghanistan to raise awareness for civilian harm, it also claims to have contributed to the US Army doctrine on Civilian Casualty Mitigation.Footnote 33 Another noteworthy example relates to the Executive Order signed by US President Obama on 1 July 2016, requiring regular reporting about ‘assessments of combatant and non-combatant deaths’ resulting from US strikes against ‘terrorist targets outside areas of active hostilities’. It requested the Director of National Intelligence to report annually on these matters and, among others, ‘address the general reasons for discrepancies between post-strike assessments from the U.S. Government and credible reporting from nongovernmental organizations regarding non-combatant deaths’.Footnote 34 Despite the later revocation of parts of this reporting requirement by President Trump, this phrasing indicated that NGOs had managed to convince the US administration of the credibility of their information to foster transparency about the use of military force. Although Obama denied that transparency improving measures like these were a direct result of NGO campaigning, he recognised that ‘having these non-profits continue to question and protest ensured that, having made that initial decision, we kept on going and that it got pushed all the way through’.Footnote 35 Interestingly, in other countries, such as Belgium or the United Kingdom, these NGOs have not yet gained access to the defence administration, despite similar campaigns. In the following section, we outline a theoretical framework that will form the basis for the investigation of when and how these NGOs gain access to defence administrations in consolidated democracies when campaigning for transparency.

Civil-military resource exchange

In this article, we study access to defence administrations rather than policy change itself, as drawing causal links between NGOs’ actions and successful policy change is challenging. For this reason, access is often studied as one of the end goals of advocacy groups such as NGOs, as gaining access is often the first step to increasing groups’ policy influence.Footnote 36

We take a resource exchange perspective, which is a dominant perspective in studies that aim to explain when and how NGOs gain access to decision-makers. Resource dependency theory highlights organisations’ dependence on resources to survive.Footnote 37 In most fields, decision-makers require the resource of expert information to design and implement effective policies; they often rely on external organisations (including NGOs) to produce this information. These external organisations can therefore ‘exchange’ their information and resources for access to the decision-making system.Footnote 38 Such exchange models have been used to explain interactions between (international) NGOs and international organisations.Footnote 39 NGOs’ access to decision-makers therefore depends on them being able to prove themselves as reliable and credible providers of information.

The literature on NGO-military cooperation highlights that NGOs can provide resources to decision-makers around the use of force. In conflict theatres, NGOs can provide military decision-makers with technical information that generated based on their local contacts.Footnote 40 The NGOs introduced above, for example, provide military administrations with their counts of civilian casualties and their expertise about how to reduce civilian harm.

Nonetheless, an exchange relationship requires supply and demand. Although NGOs may have useful technical information that they can provide to defence administrations, gaining access requires the administrations to realise that they need this information and be willing to open up and establish a working relationship with NGOs. We argue that politicisation is a key condition that increases decision-makers’ awareness of and demand for NGOs’ technical information.

Politicisation and legitimacy

Politicisation refers to the act of moving an issue into the public sphere, allowing it to be debated and for collectively binding decisions to be taken on the matter.Footnote 41 It highlights the shift from technocratic decision-making to policymaking processes involving political and public debate, and an increased involvement of elected politicians.Footnote 42 The effect of politicisation on the responsiveness of institutions has increasingly been studied in the literature on lobbying and advocacy. Policymakers are expected to be more responsive to societal interests when an issue is politicised, as otherwise they face public or electoral backlash.Footnote 43 Politicisation seems to increase elite responsiveness particularly to civil society groups and groups with lower resources.Footnote 44 For example, groups with broad support are more likely to gain access to advisory councils in politicised policy fields,Footnote 45 and NGOs can also attempt to cause politicisation themselves through public campaigns to gain insider access.Footnote 46 Politicisation overall therefore seems to have a generally positive effect on NGOs’ access to policymakers.

We argue that politicisation of the (consequences of the) use of military force – where decisions often take place outside the public eye – may similarly have a positive effect on NGOs’ access to military decision-makers by increasing the demand for legitimacy in the decision-making process. In the fields of human rights and international humanitarian law, NGOs’ ability to provide accurate information is seen as the source of legitimacy behind their naming and shaming campaigns.Footnote 47 In NGO-military cooperation in conflict theatres, too, the potential for NGOs to provide legitimacy and improve a mission's reputation is increasingly acknowledged.Footnote 48 Demand for legitimacy can be particularly strong in policy areas where there is little or no involvement of elected officials,Footnote 49 including military affairs. Nonetheless, this demand may be dependent on politicisation. Before this, there is minimal political risk in keeping decision-making technical and behind closed doors, particularly for a traditionally secretive policy field such as defence. Once an issue is drawn into the public debate, though, defence decision-makers are compelled to include stakeholders.

Yet, we argue that control over technical information is an important prerequisite for politicisation to have this effect. Politicisation will not necessarily improve NGOs’ chances at gaining access if they have not previously proven their ability to offer useful and impartial information – in this case, data about civilian harm and proof that civilian harm reporting can effectively be implemented. Without first proving their ability to provide impartial, credible information, NGOs will not be recognised as useful partners. To rephrase the argument, we could say that politicisation opens up a policy window whereby access becomes easier;Footnote 50 NGOs – like Kingdon's policy entrepreneurs – must be prepared with their alternatives in order to make the most of this window of opportunity when it arises. Yet, this politicisation is not a purely exogeneous factor: NGOs actively attempt to politicise issues in order to draw public attention to the issue that they work on and to their provision of technical information in the policy field. Particularly in the executive-dominated field of foreign and defence policy, wider politicisation (through, for example, parliamentary and media work) may be key to drawing also executive attention to the impartial information that these NGOs can provide and therefore their added value, meaning that once the defence administration feels the need for increased legitimacy, they will ‘reach for’ the NGOs that they have heard about.

This leads to a circular logic, whereby technical resources must precede politicisation but are also reinforced by that politicisation. NGOs’ technical resources are what enable them to provide political legitimacy to the policymaking process, and it is only once the impartiality of these technical resources is established and known about that the executive will be willing to grant them access. For this reason, it is important to focus on both aspects of the process, with a proven ability to exchange resources as a prerequisite to gaining access once politicisation occurs. Establishing a cooperative relationship with defence administrations is therefore expected to require both the ability to provide technical information, but also a politicisation of concerns around the use of force. Without such politicisation, which we conceptualise as a combination of increasing media salience and political debate, defence decision-makers are unlikely to open up to NGOs.

Airwars and transparency commitments by the Dutch government

We apply these expectations to the campaigns of Airwars, an international London-based NGO that was founded in 2014 by former journalist Chris Woods with the aim of fostering transparency about military actions and civilian harm, monitoring, and assesses military actions and civilian harm claims in conflicts such as Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Somalia. We focus specifically on Airwars’ campaigns for transparency about the use of force and civilian harm in the Netherlands, which is a typical case of NGO campaigns followed by policy access. Concretely, in this case, NGOs such as Airwars not only campaigned for transparency, they also managed to establish a working relationship with the Ministry of Defence to improve transparency procedures. In a reply to the parliament on 29 June 2020, the Dutch Minister for Defence Bijleveld laid out changes to civilian harm reporting procedures.Footnote 51 The commitment followed upon a year of political debates in response to the reveal that a Dutch airstrike in Iraq in 2015 had killed an estimated seventy civilians.Footnote 52 Airwars was among the most prominent voices in pushing the Dutch government for transparency.

We are aware that the choice for a single case might be vulnerable to critique. However, the case of Airwars’ activities in the Netherlands allows us to do more than just explore how the NGO achieved access to the executive and the military. The within-case variation in terms of access also makes it possible to probe our expectation about politicisation as a condition for access, while keeping other contextual sources of variation constant (for example, government coalition constellation, executive-legislative relations, parliamentary system).

Following the presented theoretical framework, we expect that Airwars may have worked to prove itself as a source of impartial technical information, but only gained access to the defence administration after successful politicisation of their transparency concerns. This politicisation should materialise in the form of growing salience, that is, increased media attention for these transparency concerns, and growing political debate, namely increased mentioning of transparency concerns in parliamentary debate and – ideally – political recognition of Airwars as a legitimate source.

For the sake of analytical clarity, by defence decision-makers or defence administrations we mean both government officials – principally the Minister for Defence, who acts as the hierarchical superior to the armed forces, and her policy directorates – and military staff involved in decision-making about the use of force. Access is defined as being invited for meetings with these defence decision-makers to discuss policy options.Footnote 53 Given that we deal with a consolidated democracy in which there is formally a hierarchical relationship between the Minister for Defence and the armed forces, gaining access to the military defence administration by default involves gaining access to the civilian defence administration.

Empirically, we build on data from three types of sources. We conduct a content analysis of media coverage in the country's five largest newspapersFootnote 54 (collected using the Lexis Nexis database) and of parliamentary documents and meeting records retrieved from the Dutch Tweede Kamer website. To this we add insights from interviews with Airwars staff, involved members of parliament and the MoD to dig deeper into the actual advocacy practice and decision-makers’ responses.

Airwars’ resources

Airwars is a small NGO, fully funded by foundations and grants, with only a few full-time staff, who mostly come from journalistic and data analysis backgrounds. Its main aim is to achieve transparency regarding civilian casualties in international military actions. Chris Woods founded the NGO in 2014 with a €15,000 grant from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, an independent foundation that funds a variety of different causes, after his previous experience researching civilian casualties while working for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism's Drone Monitoring Project and writing a book about the topic. Airwars’ original goal was relatively narrow: to establish a methodology to count civilian casualties in an ongoing military air campaign and to provide journalists with credible numbers for these casualties. While advocacy now makes up around half of the organisation's work, Airwars’ main asset and driver in this advocacy remains its robust dataset of civilian casualty counts and its consistent use of a specific methodology.Footnote 55

Airwars operates by tracking and assessing secondary sources’ claims of civilian casualty – traditional and social media in Iraq and Syria, international and local NGO reports – and comparing these against official military reports. Airwars then provides an assessment of these figures based on the reliability and consistency of sources, ‘grading’ events along a scale from ‘contested’ (competing claims of responsibility for casualties) to ‘confirmed’ (a belligerent has accepted responsibility). Claims are also discounted if it is shown that local forces were likely responsible or if those killed were combatants. The available data are compiled, assessed, and cross-referenced with military briefings to identify discrepancies with responsibility claims by military forces. This means that Airwars gathers a wide amount of data to come up with one, accurate figure for civilian casualties in a particular airstrike.

This unique methodology, grounded in local information about airstrikes and civilian harm, makes Airwars an example of an NGO that has a clear supply of technical knowledge with the potential to inform public and political debate about transparency. Yet, that in itself does not guarantee that this information also makes it onto the agenda of the executive and military, let alone that it leads to political transparency commitments.

Outreach, naming, and shaming in the Netherlands

While Airwars initially focused primarily on US airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, attention gradually widened to other coalition partners, including the Netherlands. The choice to target the Netherlands was made for two reasons. The first was financial: a grant from Stichting Media and Democratie, an independent Dutch foundation supporting and funding critical investigative journalism and democracy, allowed the organisation to fund an advocacy officer and open a Dutch-based office in 2017. Second, the Netherlands stood out from the start of Airwars’ activities as one of the least transparent members of the US-led coalition and therefore as a potential target. According to interviewed Airwars staff, however, the organisation's advocacy was received in a rather ‘dismissive’ manner during the first two and half years, by the defence administration.

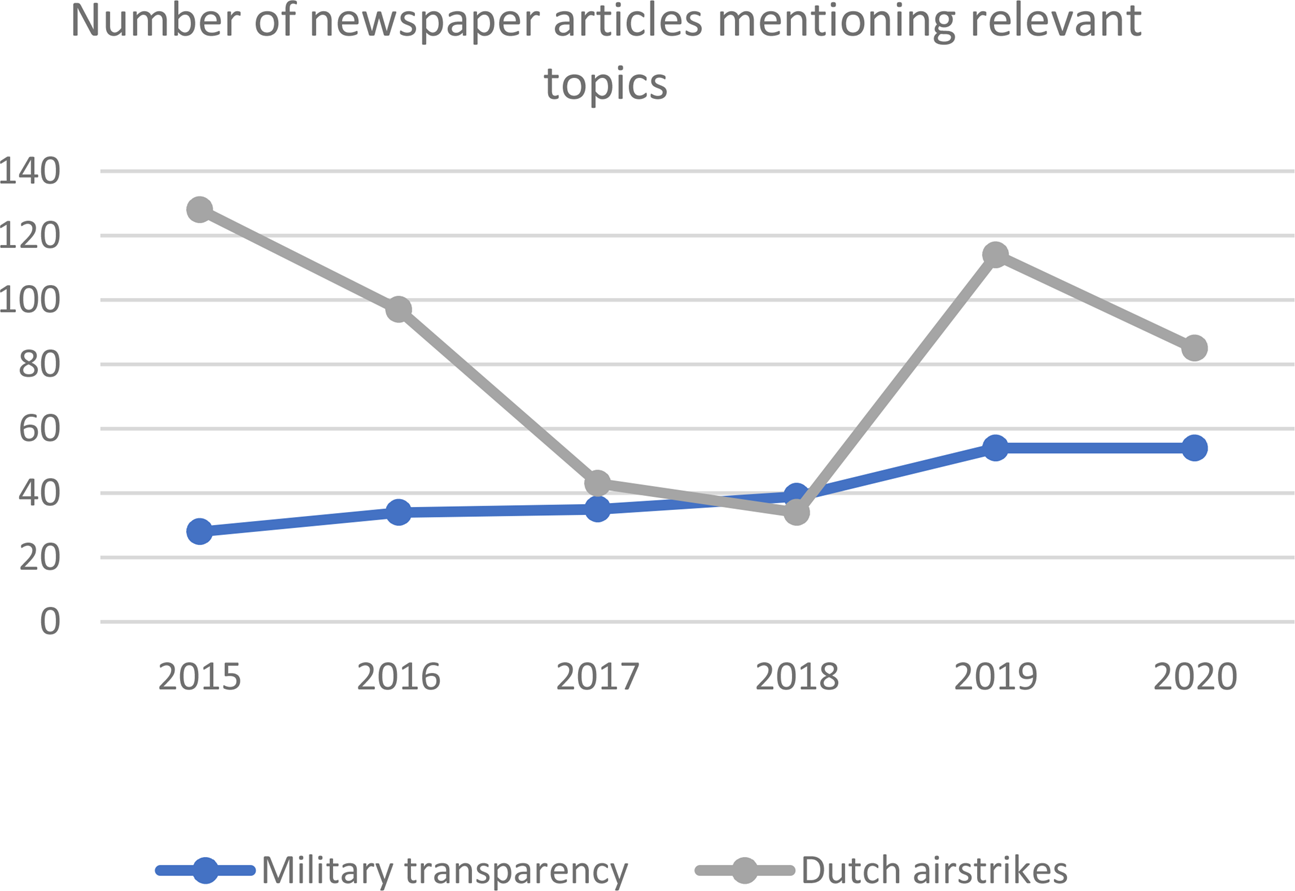

Indeed, Airwars’ transparency concerns initially gained little (systematic) traction in Dutch political debate. For instance, in the period 2015–16, Airwars was mentioned only five times in parliamentary questions and debates (Figure 3). This is not entirely unsurprising, as Airwars’ first full-time Dutch staff member only started in 2017, after establishing a local office. Access to parliamentary debate only really occurred from early 2018 onwards. Contrary to the relative absence of political attention, media did cover Airwars’ reports consistently throughout 2015–18, with 38 articles in national newspapers over this period; however, this coverage predominantly focused on civilian harm and transparency concerns about the Coalition as a whole, rather than on reporting practices in the Netherlands (see Figure 1). A similar pattern is observable when looking at media attention to military transparency: attention rose steadily from 2015, peaking in 2019, indicating the growing importance of transparency as an issue of concern. This contrasts with coverage of Dutch airstrikes, which not show the same pattern: after a peak in the early years of the Dutch contribution to the coalition, it fell sharply and only rose again in 2019 (see Figure 2). Comparing the two illustrates the rise in salience of military transparency in comparison with coverage of Dutch military activity more generally.

Figure 1. Count of Dutch newspaper articles mentioning Airwars.

Figure 2. Count of Dutch newspaper articles mentioning military transparency and Dutch airstrikes (search terms: transparant* AND defensie; nederland* AND luchtaanval* OR luchtbombardement*).

Figure 3. Mentions of Airwars in Dutch parliamentary debates and questions.

Part of the problem with attracting sufficient attention was that Airwars did not yet have a firm foot on the ground in the Netherlands. Contrary to its activities in, for example, the US, it had to start from scratch in developing a political network and finding entry points to inform political debate,Footnote 56 rather than building on existing networks. This also meant that Airwars’ initial advocacy activities towards the Netherlands largely took the form of a naming and shaming strategy, based on the datasets that Airwars was continuing to develop. By publishing transparency rankings comparing coalition partners’ reporting practices on conducted air strikes with its own data, it attempted to spark national political debate from a distance.

Early reports on civilian harm caused by coalition airstrikes that compared officially released data with Airwars’ own datasets on civilian casualties did receive some parliamentary attention in the second chamber. Yet, government reactions to these publications were largely absent and answers to parliamentary questions remained predominantly dismissive. For instance, in August 2015, Airwars published the report ‘Cause for Concern’, wherein it compared official figures with its own numbers of civilian casualties and assessed reporting practices by the coalition partners. The report explicitly recommended the Dutch MoD that it, among others, ‘[restore] its practice of reporting weekly on how many weapons are released’.Footnote 57 These concerns were echoed in a few parliamentary questions,Footnote 58 but hardly to the extent that it could be interpreted as real politicisation.

Likewise, in February 2016, Airwars submitted a report to the Dutch Foreign Affairs Committee on the lack of transparency of Dutch airstrikes in Iraq and Syria.Footnote 59 The report, which received some media attention, compared Dutch transparency to several other Coalition partners and recommended that the Netherlands adopt Coalition best practice in terms of reporting. It also reiterated an investigation from the previous year by Airwars and Dutch broadcaster RTL that showed – based on Airwars data – that a Dutch aircraft had been implicated in a 2014 airstrike that had caused civilian casualties. Airwars did not do this in an unrestrained way, including a discussion of the ways in which transparency could be ensured without threatening operational security.Footnote 60

Illustrative was the response by then Minister for Defence Hennis-Plasschaert, as she questioned Airwars’ low estimation of Dutch transparency: ‘I don't think we do things so differently to the other Coalition partners … earlier this week the media stated that the Netherlands stands far behind others. I don't recognise that picture.’Footnote 61 She furthermore relied on transparency measures taken by the US Central Command (CENTCOM) as proof that the Coalition was transparent enough, a commonly used strategy.Footnote 62 In the 2017 parliamentary debate to extend the Dutch contribution to the Coalition, the Minister for Foreign Affairs accepted a cross-party motion calling for more transparency measures, but rejected a call to allow for independent investigation of civilian casualties, highlighting that the Dutch MoD was pushing for international cooperation between Coalition partners.Footnote 63

This dismissive atmosphere and limited parliamentary engagement remained dominant throughout 2016, even when Airwars published a ranking of Coalition partners’ transparency based on several criteria (frequency of reports, nearest location given, date of strikes given, munitions/strike numbers released). Even though it ranked the Netherlands last out of the 13 countries and issued several concrete recommendations for improving transparency without threatening operational security, no parliamentary references reacting to this report were found. Quite crucially, however, this report was not without effect outside of the Netherlands. Airwars staff highlighted that the launching event was attended by US CENTCOM delegates and NATO observers. This ultimately led to a further strengthening of the already cooperative relationship between Airwars and CENTCOM, causing CENTCOM to install a range of transparency improvements.Footnote 64

Once a local office was established in 2017, also key contacts in parliament were identified or presented themselves. Particularly socialist MP Sadet Karabulut proved to be Airwars’ much needed entry point. On 28 November 2017, Chris Woods (founder and then director of Airwars), together with several other journalists and civil society representatives, was invited by MP Karabulut (SP) to a public roundtable to discuss civilian casualties in the war against ISIS. Airwars wrote a briefing in Dutch and English for this meeting, focusing on its data on civilian casualties from Dutch airstrikes and transparency reporting. In terms of parliamentary debate, this briefing and public event caused more discussion than the previous reports. Particularly the ‘uncomfortable fact that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have on occasion issued more information on their anti-ISIS air campaigns than the Netherlands’Footnote 65 was picked up by several MPs in the latter half of 2017.Footnote 66 During this period, media attention to Airwars also spiked, with twenty articles mentioning Airwars during 2017; however, these were mainly referring to Airwars on the increase of civilian casualties in the first year of the Trump administration, with only a few articles critiquing Dutch reporting practices. Nonetheless, this period saw regular use of Airwars’ data to report in the media about civilian casualties and call into question official statistics, reflecting a growth in awareness and recognition of the organisation as a credible source.

It is also noteworthy that during this period, parliamentary references to Airwars’ reports and data rose significantly. Airwars’ ranking efforts gained particular traction. As shown in Figure 3, twenty references were made to Airwars in the Defence and Foreign Affairs committee meetings in 2018 (during eight separate incidents). Yet, two remarks are quite crucial here: first, at this point, parliamentary interventions were mainly limited to two main ‘champion’ MPs – Karabulut (SP) and Öztürk (DENK) – who regularly brought up the issue of transparency and data sharing in parliamentary debates and questions; and second, this gradually growing politicisation in terms of increased political debate still did not come with access to the executive. Government reactions to these efforts remained largely dismissive, which gave the impression that a reconsideration of reporting practices was unlikely at that time.Footnote 67 When asked about how these transparency rankings were received, interviewees from the MoD responded that these were looked at with great interest, yet in their view, ‘the rankings did not fully recognize and appreciate that larger coalition partners, such as the US, likely have more information and resources for offering such transparency than smaller allies, such as the Netherlands, and that every partner is bound to make their own sovereign choices.’Footnote 68 Furthermore relevant is the fact that until this point, contacts between Airwars and the Ministry of Defence did take place, yet these did not go beyond contacts with the Communications Directorate and can in that sense not be considered real ‘access’.

The Hawijah reveal

Real progress in terms of politicisation, and first signs of a real executive openness to cooperation, could only be observed in the course of 2019. Interestingly, in April 2018, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Affairs had sent a letter to the House of Representatives, which revealed investigations by the Dutch Public Prosecution Service and Ministry of Defence into four air strikes that might have led to civilian casualties between 2014 and 2016. These investigations received some media attention yet, despite acknowledging responsibility for civilian casualties in up to three airstrikes, the MoD commented that no violation of procedures had been found and refused to identify specific dates or location. In response, Airwars published a parliamentary brief in Dutch and English again referring to its data on civilian casualties in Dutch airstrikes, comparing the Netherlands’ lack of transparency with other Coalition partners and refuting Dutch claims that transparency threatens national security.Footnote 69 Apart from a series of opinion pieces published in national and local newspapers, however, public attention to these investigations remained low. Noteworthy is that the parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee, upon the initiative of opposition MP Sadet Karabulut, consulted with officials from the US Department of Defence and CENTCOM during a working visit to the US in the course of 2019. In this way, MPs gained first-hand insights into the transparency practices applied in the US, resulting in a series of proposals submitted to the MoD in May 2019.Footnote 70 This gradual political attention further contributed to a so-called ‘culture shift’ of growing recognition of the need for transparency within the MoD.Footnote 71 It even led to a first face-to-face contact between the Dutch MoD's Directorate of International Affairs and Airwars in July 2019 about the government's transparency policy.Footnote 72 However, both sides also confirmed that these early contacts could hardly be labelled as a systematic interaction.Footnote 73

Broad politicisation in terms of media attention and political debate occurred only after the publication of a joint investigation by Dutch broadcasting agency NOS and newspaper NRC on 19 October 2019, alleging that Dutch airstrikes had caused civilian casualties in the Iraqi city of Hawijah in June 2015. These news agencies conducted their investigation on the basis of Airwars’ data about civilian casualties, which had already in 2015 reported on seventy civilian casualties caused by Coalition airstrikes in Hawijah.Footnote 74 Airwars had mentioned these numbers in its 2018 parliamentary brief on Dutch civilian harm and was ‘aware of significant private speculation by Dutch journalists as to whether the Netherlands was responsible for the Hawijah event – one of the worst casualty incidents of the early war against ISIS’.Footnote 75 Although Airwars had close contact with the media and provided its technical data as a basis for the investigation, it chose not to be named in the reveal. They were not yet absolutely certain of their data and feared that, if wrong, involvement could undermine their legitimacy and credibility as a neutral source of on-the-ground information.Footnote 76

Parliamentary and media coverage data show that the publication of this investigation was the turning point in terms of politicisation of transparency concerns about Dutch airstrikes (see Figures 1 and 2). Previous research into the same case also highlighted the importance of the investigation, which rendered the MoD's strategy of denial of civilian casualties impossible.Footnote 77 Once again, this did not immediately lead to openness for cooperation on improving transparency and reporting practices. On the contrary, reactions by the Dutch Minister of Defence Ank Bijleveld to the Hawijah accusations long remained ambiguous, with responsibility acknowledged only on 4 November 2019.Footnote 78 Four plenary parliamentary debates were held in the months following the Hawijah investigation, on 5 and 27 November 2019, 19 December 2019, and 14 May 2020.

Initial parliamentary debate focused mainly on the question of whether the then Rutte government, and particularly its then Minister for Defence Hennis-Plasschaert or any other department was informed about these civilian casualties.Footnote 79 This included repeated references to Airwars data and reports, as an ‘independent’ and ‘very, very reputable and professional NGO’.Footnote 80 During the first debate on 5 November 2019, the Minister highlighted that it had been taking steps towards improving transparency since May. She added that this included consideration of a range of proposals that she had received from opposition MP Karabalut, who had in May requested the Minister to take a closer look into the casualty reports of among others Airwars. The Minister added that in this process of improving transparency, ‘we have spoken with Airwars’, referring to the aforementioned meeting of July 2019.Footnote 81

Interviews suggest that Airwars was able to play a key role in terms of reinforcing the work of these journalists’ investigations and MPs’ pressure. The organisation arguably decided to withdraw itself from its talks with the MoD while it continued denying its involvement in the Hawijah case.Footnote 82 Moreover, shortly before a parliamentary debate about the civilian deaths in Hawijah, Airwars released a technical analysis indicating that official US data had counted the seventy Hawijah deaths, contrary to what the Dutch MoD had been claiming based on the information they had received from the US.Footnote 83 In March 2020, shortly before the fourth parliamentary debate, Airwars published an investigation alleging that at least one other Coalition member had refused to conduct the Hawijah airstrike based on intelligence indicating that the risk to citizens was too high.Footnote 84 By both withdrawing its cooperation with the MoD and providing MPs with briefings and evidence throughout the period of parliamentary debates, Airwars was able to leverage its position as a legitimate, recognised source on civilian casualties and help to shape the discussion taking place.

Access and political commitments

Transparency debates came to a peak with a vote of no confidence in Minister Bijleveld in early November 2019 after she stated that she had not known that her predecessor had incorrectly informed the Parliament about civilian casualties at Hawijah. Although the vote failed, this brought transparency issues sharply into focus and framed the subsequent debate around who had known about Hawijah.

At the same time as it was supporting media and parliamentary work, Airwars was invited to the table at the request of the MoD to start a ‘Roadmap process’. This process began after a meeting between a consortium of NGOs, academics, and defence officials, who in January 2020 began to draft a roadmap of how the MoD and military could review and improve their civilian harm transparency and accountability practices. To this end, Airwars and Open State Foundation gave the MoD a guide to transparent reporting of airstrike data in June 2020.Footnote 85 In November 2020, the process was officially launched and attended by senior Dutch military officials, with specialist sessions on specific aspects of tracking civilian harm scheduled for 2021. In total, four meetings took place between the civil society consortium partners and the Ministry of Defence during the Roadmap process.Footnote 86 Noteworthy is that this process involved not only officials from the MoD's policy directorates but also military staff members, evidence of the first systematic and formal opening-up of defence decision-makers towards NGOs to discuss transparency improvements. In that light, interviewees from the MoD indicated that such a culture shift towards transparency had already been ongoing within the Ministry for several years; yet they also confirmed that focusing events like the Hawijah reveal considerably accelerated this process. Moreover, they emphasised the need for the military side to be convinced of this need for transparency and inclusion in the roadmap discussions for the change to be successful.Footnote 87 Interviews with Airwars staff furthermore highlighted the importance of the consortium for the success of their engagement with the MoD – not only did these partnerships strengthen their position, but several of the NGOs had worked together in interactions with CENTCOM in the US, meaning that they were already aware of their strengths and weaknesses.Footnote 88

Findings

Our analysis of parliamentary meetings, media coverage, and interview data leads to three findings about how and when Airwars gained direct access to the Dutch defence administration to advocate for transparency about the use of force and civilian harm.

First, the empirics show that NGOs like Airwars, which strive for transparency about civilian harm and the use of force, can establish a working relationship with the defence administration to take steps in improving reporting procedures. While previous studies already offered strong support for such a cooperative relationship in peacekeeping missions, our analysis shows how this can also materialise domestically to the benefit of transparency and accountability.

Second, the case of Airwars in the Netherlands shows how possession of detailed, on-the-ground information can be a critical resource. In this case, Airwars’ work from 2017 onwards in the Netherlands providing information to opposition MPs and to the media established it as a credible source of technical information on civilian casualties in the war against ISIS, as reflected in the use of Airwars data in Dutch newspapers and references to the NGO during parliamentary debates. This set the foundation for Airwars to be considered as a partner by the defence administration. In addition to its data about civilian casualties, Airwars’ acknowledgement of the need for secrecy and its information on implementing transparency practices without putting operational security at risk was also key to being taken seriously, a finding that echoes previous studies of NGO involvement in military use of force.Footnote 89 This indicates that information exchange relationships, commonly studied in the literature on lobbying and NGO advocacy,Footnote 90 can apply even in more sensitive political areas.

Third, our analysis also shows that such technical information is itself unlikely to be sufficient for gaining access. This information must be recognised as credible and legitimate. Defence administrations’ recognition of the need for NGOs’ resources seems to depend on the level of politicisation of the issue. Airwars actively tried to create this politicisation itself by finding key political ‘champions’ within parliament, who repeatedly raised Airwars’ concerns in debates with the executive, and through media attention to the issue. Airwars’ own naming and shaming tactics contributed to this politicisation, reinforcing previous findings that NGOs strategically attempt to politicise issues to subsequently gain access.Footnote 91 Yet, to some extent, politicisation is also outside NGOs’ control: the Hawijah investigation by NRC and NOS was a key focusing event that sharply raised public attention to the issue of transparency around the use of force, increasing the scrutiny of military decision-makers and thereby raising their demand for Airwars’ technical information to provide legitimacy to the policymaking process. Airwars’ previous work in developing a reputation as a provider of credible data on civilian casualties was thus rewarded when politicisation did ultimately happen.

In some sense, the Hawijah investigation created a policy window that facilitated the final policy change by coupling the policy streams, and NGOs acted as policy entrepreneurs to put forwards a solution.Footnote 92 Our interviews with MoD officials, however, showed that the Dutch defence administration was already well aware of the issues and concerns about transparency around civilian casualties and was also aware of the solutions from different sources – not only campaigning NGOs, but also through the US's and CENTCOM's experience. This means that these concepts are useful, but not sufficient, for explaining the case. Instead, it seems that the politicisation and resulting policy window pushed the defence administration to accept the solutions that it was already aware of, increasing their demand for external legitimacy and therefore opening up to NGOs.

Conclusion

It is easy to consider NGOs and military decision-makers as actors with opposing organisational agendas and cultures. While this fallacy has gradually been disproved, most studies focusing on NGOs’ role in the field of security and defence have examined their relationship with the military in conflict theatres. In this article, we studied how NGOs can also play a role in the domestic process of civilian control of military affairs, examining how and under what conditions NGOs striving for transparency in the use of force and civilian harm can gain access to defence administrations. Taking a resource exchange perspective to study Airwars’ actions in the Netherlands, we found that its control of information about the consequences of the use of military force allowed it to gain access to, and engage in a constructive dialogue about transparency improvement with the defence administration, that is, the MoD and its military staff. Nonetheless, systematic access took place only after the issue was politicised through parliamentary and media attention, which increased the executive's demand for legitimacy and for Airwars’ information.

Like any study, this article has some limitations. First, our research design and data mean that we cannot make strong claims of causality. Second, our study focused exclusively on access, not on policy change. Studying the effect of civil society consultation on actual policy change would require a design that more explicitly takes into account intra-institutional dynamics, including decision-making procedures between the MoD and key military decision-makers.

Despite this, our findings are relevant for the broader fields of civilian control of the military and NGO studies. First, we extend resource exchange approaches to the field of security and defence, highlighting the ways in which NGOs can gain access to decision-makers even on politically sensitive topics, which are often characterised by high levels of confidentiality. Second, we add to the literature on NGO-military cooperation by examining their relationship in domestic politics rather than in conflict theatres. This is an important addition to the civil-military relations literature, particularly in the light of recent calls for updating ideas about military professionalism and role conceptions to meet contemporary challenges of politicisation. Finally, the findings contribute to broader discussions about transparency in the use of force and civilian harm, and civilian control of military affairs. Understanding how NGOs push for transparency can help to understand the implications for governments and armed forces whose missions are not seen as legitimate by the population.

Ultimately, we hope that this article serves as a starting point for further research into the conditions under which NGOs gain access to defence administrations, and their capacity to weigh in on debates and policymaking about the use of military force and its consequences. For instance, our single case design did not allow us to study the determining effect of the amenability of individual leaders to societal concerns about transparency of the use force. While interviews with MoD officials suggested that the Minister for Defence Bijleveld herself was one of the key drivers of the change of culture in the ministry towards transparency, this leadership argument requires testing in further cases. Similarly, future scholarly research about the party politics of security and defence affairs would do well in exploring the effect of governing parties’ ideological position on their openness to such calls for transparency.

Those interested in NGO campaign strategies could address the importance of advocacy coalitions in the field of security and defence. Airwars gradually expanded its network in the Netherlands between 2017 and 2020, teaming up with other civil society organisations and academics active on related matters; this was raised as a strength of the organisation in interviews and seemed to make its concerns echo louder. Future research could explore these conditions through, for instance, a comparative assessment of advocacy campaigns in other countries that participated in the US-led coalition against ISIL. Ideally, this would also include countries with different party-political and parliamentary systems than the Netherlands.

Civil-military relations scholars interested in changing military role conceptions might in turn do well in expanding their focus to military conceptions of transparency and accountability. Likewise, they can further investigate if the politicisation of transparency calls creates rifts between civilian leadership and the military, or between the civilian and military parts of defence administrations. Finally, full transparency about the use of military force is not desirable, and should not be the ambition. In that sense, it is still an open question how much secrecy these NGOs that advocate for transparency about the use of force and its consequences are willing to accept in return for being granted access to policymaking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants at the Politics and Culture in Europe (PCE) colloquium, as well as panellists and discussants at the 2021 ECPR General Conference, for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Dr Francesca Colli is Assistant Professor in European Politics at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Maastricht University. Her research focuses on the role and lobbying activities of civil society and social movements on national and EU policy. Author's email: f.colli@maastrichtuniversity.nl

Dr Yf Reykers is Assistant Professor in International Relations (tenured) at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Maastricht University. He studies issues relating to European security and defence policy, with a particular interest in the politics of multinational military operations, questions of accountability, and rapid response. Author's email: y.reykers@maastrichtuniversity.nl