Introduction

Populism, however defined, pits the people against the elite. Populists usually portray ‘the people’ as inherently good and virtuous, whose interests they defend against ‘the elite,’ who in turn are seen as evil and corrupted (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2016). While people‐centrism and anti‐elitism are considered to be essential components of populism, we lack systematic, large‐scale comparative evidence on which people or groups constitute ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ in the eyes of populist parties.

Both ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ can be seen as ‘empty signifiers’. For Laclau (Reference Laclau and Panizza2005), an empty signifier is a concept that lacks a fixed, specific meaning. Indeed, discourse‐ and framing‐based approaches highlight that empty signifiers can be mobilized and filled with various meanings by different political or social actors contingent on different political contexts (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016; De la Torre, Reference De la Torre2016; Katsambekis, Reference Katsambekis2022). As such, despite lacking a fixed meaning, the empty signifier can become a symbol of collective mobilization. This argument has been made most forcefully for ‘the people’. Margaret Canovan (Reference Canovan2005, p. 3) wrote: ‘The vagueness of ‘the people’ is a mark of its political usefulness; captured at different times by many different political causes, it has been stretched to fit their different shapes’. Also, scholars advancing an ideational approach to populism studies have highlighted that the very ‘empty’ nature of ‘the people’ makes populism such a powerful political phenomenon (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017, p. 9).Footnote 1

By contrast, which groups constitute ‘the elite’ in the eyes of populists has received far less scholarly attention. While virtually all populists target actors they claim to be the ‘corrupted political elite’, some populists also attack economic or cultural elites. Yet, also here the indeterminate nature of ‘the elite’ is a useful rhetorical device to condemn ‘those above’ who do not take ‘the people's’ true interests to heart. In other words, both concepts, ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, allow political actors to construe their meaning according to their particular worldview.

As such, we are faced with an urgent question: Can we identify patterns in the ways in which populist parties define ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’? For example, how does a left‐wing populist party, such as Podemos (We Can) in Spain, differ from a radical right populist party such as the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid (Freedom Party), in their assessment of the people and the elite? Moreover, do economic or cultural positions shape parties' conceptions of the people and the elite? And do highly populist and non‐populist parties conceive of the people and the elite in different ways?

We argue that parties' degree of populism and their ideological leaning shape parties' tendency to include certain groups as the people and regard other groups as the elite. Left‐wing populists emphasize economic factors and therefore define ‘the people’ in economic terms by excluding the super‐wealthy (March, Reference March2017; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). Conversely, right‐wing populists emphasize cultural factors, defining ‘the people’ in exclusive ethno‐nationalist, nativist terms by excluding immigrants (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). Discourse and framing approaches to populism have similarly highlighted the differences in how ‘the people’ are constructed by left‐wing and (far) right‐wing parties and movements (Katsambekis, Reference Katsambekis2022; Stavrakakis & Katsambekis, Reference Stavrakakis and Katsambekis2014; Stavrakakis et al., Reference Stavrakakis, Katsambekis, Nikisianis, Kioupkiolis and Siomos2017). While left‐wing populists construe the people as a culturally inclusive entity of the ‘non‐privileged’ (and thereby excluding privileged citizens), right‐wing populists proffer an exclusionary, ethnocentric and nativist conception of the people.

Despite these differences, both left‐wing and right‐wing populists share a common opposition to the political elite, viewing them as corrupt or malevolent (Taggart, Reference Taggart2018). When it comes to other elites such as media elites, economic elites and socio‐cultural elites, empirical evidence on how elite conceptions of left‐ and right‐wing populist parties differ is rather scarce. Right‐wing populist parties like the Dutch Forum voor Democratie are found to criticize scientific elites' influence on society (Krämer & Klingler, Reference Krämer and Klingler2020). This echoes individual‐level research on the relationship between populist beliefs and opposition to political and scientific elites (Huber Reference Huber2020; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Greussing and Eberl2021; Meijers et al., Reference Meijers, Van Drunen and Jacobs2023). What is more, case study evidence suggests that populist parties across the ideological spectrum consider the media – in particular the ‘mainstream media’ – to be part of the elite establishment (Kenny, Reference Kenny2020). Donald Trump routinely attacks media outlets such as CNN, and populist radical right parties in Europe have advocated the abolishment of the public broadcasting system. By contrast, left‐wing populist parties have targeted economic elites and multinationals in their fight to tame capitalist excesses (Ivaldi et al., Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017).

The case study evidence discussed above provides an important first step in examining how ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ are defined by populist parties. Yet, it remains unclear whether such case evidence holds in a comparative cross‐national fashion across parties in Europe. Moreover, we often lack a clear counterfactual: How do populist conceptions of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ differ from those of non‐populist parties? Incorporating this counterfactual by measuring populism as a continuous variable, we can ascertain whether a party's conceptualization of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ is driven by their degree of populism or rather by other ideational components, such as their overall left‐right position, their economic left‐right ideology or their nativism.

Distinguishing between parties' populism and other ideational characteristics is important. Previous work has emphasized that populism is distinct from other ideational constructs, such as nativism, nationalism or Euroscepticism (Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Halikiopoulou, Kaufmann and Rooduijn2019; De Cleen et al., Reference De Cleen, Glynos and Mondon2018; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). While both populism and nativism serve as binary frameworks distinguishing an ‘us’ and ‘them’, the basis of this distinction differs. While populism makes a ‘vertical’ juxtaposition between the people and the elite, nativism offers a ‘horizontal’ antagonism between natives and non‐natives. It is therefore important to distinguish populism from nativism (see also Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017). Using factor analyses, Meijers and Zaslove (Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021, p. 391) found that nativism does not load on the same dimension as populism. Moreover, Meijers and van der Velden (Reference Meijers and Velden2023) have warned that individual measures of populist attitudes should not conflate populism with nativism by using ethnically framed markers of the people. To study the effect of party ideology in addition to populism, we examine the effects of both parties' overall left‐right ideology as well as parties' left‐right economic positions and their nativism. While overall left‐right ideology usefully captures a party's ideology in a single variable, it also conflates parties' positions on the economy and culture. Distinguishing between parties' economic and cultural positions is important as cleavage theory posits that a new cleavage has emerged pitting universalists against particularists which often centres around polarization over cultural issues, such as nativism, but also includes socio‐economic divides (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008).

This research note, therefore, offers the first comparative empirical evidence about how political parties conceptualize the people and the elite – and how this differs across parties' ideological positions and across levels of populism. Using new party‐level data from the 2023 wave of the Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Meijers and Huber2024a), we examine the effects of populism, left‐right ideology and nativism on parties' conception of the ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ across 31 European countries.

With respect to parties' conception of ‘the people’, we distinguish between an economic and a cultural conception of the people. Specifically, we examine to what extent parties believe that citizens with a migration background (i.e., a cultural conception) and highly affluent citizens belong to the people (i.e., an economic conception). These two dimensions relate to cultural and economic views of the people. As Bonikowski (Reference Bonikowski2017) and Betz (Reference Betz2019) note, far‐right populism centres on ethno‐cultural notions of the nation, excluding ‘non‐natives’. In contrast, left‐wing populists, while culturally inclusive, may exclude the ‘ultra‐wealthy’ from the people, categorizing them as the ‘1 per cent’ or ‘oligarchy’ (Katsambekis, Reference Katsambekis2022). To measure parties' conceptions of ‘the elite’, we distinguish between four societal groups that reflect different types of elites: politicians (i.e., political elites), journalists (i.e., media elites), CEOs (i.e., economic elites), and academics (i.e., socio‐cultural elites).

In terms of parties' conceptions of the people, we find that both parties' degree of populism and their left‐right ideology affect parties' inclusion of citizens with a migration background and wealthy citizens as ‘the people’. With respect to elites, the differences among left‐ and right‐wing populists are most pronounced among economic and socio‐cultural elites.

Data and empirical approach

In order to study how populist parties define ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, we rely on a new wave of the POPPA (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Meijers and Huber2024a; Reference Zaslove, Meijers and Huber2024b), which was fielded in the spring of 2023. The data covers 312 political parties in 31 European countries.Footnote 2 As in the first wave of the POPPA (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021), we include a series of items to measure various dimensions related to populism to create a continuous measure of populism. Modelled after the latent individual‐level measures of populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020), such a multi‐dimensional approach to measuring populism has high construct validity as it independently captures constitutive components of populism (see also Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens and Medzihorsky2022; Meijers & Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Wiesehomeier et al., Reference Wiesehomeier, Singer and Ruth‐Lovell2021). In addition to a multi‐dimensional populism measure, the 2023 POPPA wave measures various ideological characteristics of parties – including their positions on an economic left‐right dimension and nativism. We discuss the operationalization of these measures below.

In expert surveys, country experts integrate various sources of information about political parties to provide a qualitative assessment of a party's attributes on a scale that is specified by the research team (see Meijers & Wiesehomeier, Reference Meijers and Wiesehomeier2023, for a full discussion on expert surveys). Expert judgments are subsequently combined into an average score for each party. Expert surveys therefore represent a fundamentally a priori approach and can be seen as an indirect, reputation‐based measure of party characteristics, offering a broader level of assessment than more direct measures of party policy. The advantage of expert survey data is therefore that we are able to obtain observations for each party across 31 European party systems. By contrast, evidence derived from direct measures of party communication, such as manifestos or speech data, is bound to be more fragmented and context‐dependent (Hawkins & Castanho Silva, Reference Hawkins, Castanho Silva, Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018). Thus, while textual approaches are desirable if one is interested in context‐specific political behaviour, expert surveys can provide data across a broad set of political parties at a greater level of abstraction. In contrast, textual analyses of party manifestos (when available) or press releases are vulnerable to ‘contextual bias’ since the ideological positions that parties convey often vary significantly depending on the type of document or text in which they are presented (Hawkins & Castanho Silva, Reference Hawkins, Castanho Silva, Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018; Hawkins & Littvay, Reference Hawkins and Littvay2019).

To measure parties' conceptions of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, the 2023 POPPA wave includes a novel module which captures the extent to which parties include or exclude various groups in ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. Specifically, the survey asks experts to rate the extent to which (a) ‘citizens with a migration background’ and (b) ‘very wealthy citizens’ are considered part of ‘the people’ by the party in question, reflecting a cultural and economic conception of the people, respectively. In addition, we ask experts to shed light on the extent to which parties believe (a) politicians (i.e., political elites), (b) journalists (i.e., media elites), (c) executives of large corporations (i.e., economic elites) and (d) academics (i.e., socio‐cultural elites) are part of ‘the elite’. The group membership for each of these groups is captured on a scale from 0 (completely excluded) to 10 (completely included). The scale's middle point of 5 is thus considered a neutral point. Table 1 shows an overview of the measured items to measure parties' conception of the people and the elite. The full wording and examples of the survey items are presented in Section A in the Supporting Information. We employ neutral phrasing for elite‐related items to accurately capture variations in elite perceptions across the political spectrum without introducing anti‐elite bias. This neutral wording is essential as it allows us to analyse the relationship between populism and elite perceptions without conflating populist stances with inherently anti‐elite sentiment.

Table 1. Overview of the constitutive groups measured for ‘the people’ and ‘the elite'

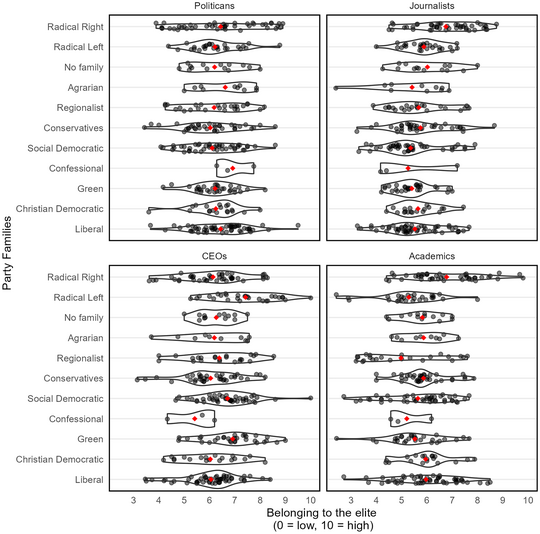

Descriptive evidence

Figures 1 and 2 show parties’ stances on the various groups outlined in Table 1 in a violin plot. The violin plot displays the distribution of data across different party families, with the width of the ‘violin’ indicating the density of data points at each level. Each observation represents a single party. The party families are ordered by their degree of populism in our dataset. Radical right parties are on average the most populist, liberal parties the least populist parties in our data. Low (high) values indicate that parties consider the societal group in question to belong less (more) to the people/the elite. Immediately, interesting patterns in line with our expectations emerge.Footnote 3 Figure 1 demonstrates that radical right parties strongly exclude citizens on cultural terms but seem rather indifferent with respect to economic factors. The pattern is precisely the opposite for the radical left party family, which shows that they are rather inclusive towards citizens with a migration background (i.e., a cultural definition of the people) but exclusionary in economic terms. These two‐party families typically contain most of the left‐ and right‐wing populist parties. Beyond the radical right and the radical left, we see moderate left‐right patterns with centre‐left mainstream parties being more inclusive in cultural terms, but less so in economic terms (and vice versa for centre‐right parties).

Figure 1. Party families and the people.

Note: Each dot represents one party. Red squares are the mean within a group.

Figure 2. Party families and the elite.

Note: Each dot represents one party. Red squares are the mean within a group.

The patterns shown in Figure 2 for parties’ elite conceptions are substantially more tentative. While there is little variation in how different party families see political elites, the radical right party family is most sceptical of media elites (journalists) and socio‐cultural elites (academics), as one would expect. The radical left is most sceptical of economic elites. However, these effects are more nuanced than in Figure 1. For mainstream parties, we fail to see clear patterns here.Footnote 4

Measurement and estimation strategy

The political leaning of parties and their degree of populism are the central predictors of parties’ conception of the people and the elite. To capture populism, we asked experts to rate political parties’ use of various dimensions of populism on a 10‐point scale. In line with the 2018 POPPA wave (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021), we ask them to rate parties on five components of populism: anti‐elitism, people‐centrism, indivisibility (or homogeneity) of the people, general will and a Manichean outlook. Table A1 in the Supporting Information shows the exact wording of the items. These items capture the full breadth of the ideational definition of populism as put forward by Mudde (Reference Mudde2004). We aggregate these five items and compute the arithmetic mean across all items to compute a party's level of populism.Footnote 5

To capture parties’ ideological profile beyond populism, we use three measures: parties’ overall left‐right position, their economic left‐right position, and their nativism. Table A2 in the Supporting Information shows the exact wording of the items and the response categories. The overall left‐right position measure captures parties’ left‐right position on a parsimonious general scale, which typically captures both parties' economic and cultural concerns. However, such a parsimonious measure may also conflate economic and cultural positions and mask relevant variation. Therefore, we also measure parties' position on the economic left‐right dimension and nativism. While the former captures parties' positioning regarding privatization, taxes, regulation, government spending and the welfare state, the latter expresses parties' idea of who can and should belong to the nation‐state. These two concepts represent the two‐dimensional European political space (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), which has been shown to be relevant to the nature of how populism operates (Huber et al., Reference Huber, Jankowski and Juen2023).

We measure parties' overall left‐right ideology by asking experts to rate parties with the following item: ‘Please tick the box that best describes each party's overall ideology on a scale ranging from 0 (left) to 10 (right) (i.e., the general left‐right scale)’. For economic left‐right positions, we asked experts to state where they would place parties using this item: ‘Parties can be classified in terms of their stance on economic issues such as privatization, taxes, regulation, government spending, and the welfare state. Parties on the economic left want government to play an active role in the economy. Parties on the economic right want a reduced role for government’. We operationalize nativism with the following item: ‘Some parties have an exclusive idea of who can and should belong to the nation‐state (nativism). Please tick the box that best describes the extent to which each party regards non‐native elements (persons or ideas) in society as a threat to the nation's culture, well‐being or sovereignty’. Overall left‐right, economic left‐right, and nativism are measured on a 0–10 scale.

In order to investigate which factors drive parties' definitions of the people and the elite, we run two sets of linear regression models. In the one‐dimensional model, we take parties' degree of populism and their overall left‐right placement as central predictors. In the two‐dimensional model, the main predictors are the nativism and economic left‐right placement of political parties. In both models parties' definition of the people and the elite are the key dependent variables.

We follow up on this analysis by interacting populism with left‐right as well as ideology nativism and economic left‐right placement to investigate whether the effects of populism are conditional.Footnote 6 Parties are the unit of analysis in both sets of analyses. We use the continuous versions of economic left‐right position and nativism for the first set of models. However, to avoid making assumptions about the functional form of the interaction term, we recode this variable into three groups: parties with a score below 3 are considered left‐wing and low on nativism (respectively), parties above 7 are considered right‐wing and high on nativism, whereas the rest is concerned centrist/medium on nativism. All models include country‐fixed effects to account for any cross‐country variation (see Figures C1 and C2 in the Supporting Information). Importantly, our statistical models aim to establish empirical associations, not causal relationships.Footnote 7

Results

How do political parties construe the people and who belongs to the elite? We present the main findings of our research note below.

Who belongs to ‘the people’?

The coefficient plot in Figure 3 sheds light on which societal groups political parties believe to belong to the people. In this regression analysis, the dependent variable for the left‐hand panel is the extent to which the party in question perceives ‘citizens with a migration background’ to belong to the people, that is, defining the people in cultural terms. The right‐hand model's dependent variable is the extent to which the party in question believes that ‘very wealthy citizens’ belong to the people, that is, defining the people in economic terms. We present both the results for the one‐dimensional and the two‐dimensional models.

Figure 3. Populism, ideology, and ‘the people’.

Note: R ![]() of the people (cult.): one‐dimensional model = 0.81 / two‐dimensional model = 0.94. R

of the people (cult.): one‐dimensional model = 0.81 / two‐dimensional model = 0.94. R ![]() of the people (econ.): one‐dimensional model = 0.75 / two‐dimensional model = 0.86. Ranges represent 95 per cent and 90 per cent confidence intervals. Low values indicate low levels of inclusion in ‘the people’. Tables B1 and B2 of the Supporting Information present the regression tables for both models.

of the people (econ.): one‐dimensional model = 0.75 / two‐dimensional model = 0.86. Ranges represent 95 per cent and 90 per cent confidence intervals. Low values indicate low levels of inclusion in ‘the people’. Tables B1 and B2 of the Supporting Information present the regression tables for both models.

Starting with a cultural conception of the people, we see that both populism and overall left‐right ideology are negatively correlated with the perception that immigrants belong to the people. This means that the more populist and/or the more right‐wing a party is, the less it perceives citizens with a migration background to belong to ‘the people’. Yet, an overall left‐right variable likely masks considerable heterogeneity. As the two‐dimensional model shows, we see that the effect of populism is reduced strongly when parties' overall left‐right position is replaced by economic left‐right and nativism positions as additional predictors. We see that parties' nativism is associated with a decrease of 0.80 in the perception that immigrants belong to the people. Populism and economic left‐right positions play a subordinate role. While populism decreases the perception that citizens with a migration background belong to the people by 0.06 points, this relationship is significant at the 10 per cent level only (p‐value = 0.08). Economic left‐right positions are also negatively associated with this outcome. However, clearly nativism is the core explanatory variable here.

When considering the economic conception of the people, we find in the one‐dimensional model that populism has a negative effect while the overall left‐right position has a positive effect. Hence, the more populist and/or the more left‐wing a party is, the less it considers the affluent to belong to the people. The two‐dimensional model shows that economically right‐wing parties are generally more favourable to include ‘the very wealthy’ as part of the people, whereas economically left‐wing parties tend to exclude them. The two‐dimensional model also shows that parties' economic left‐right position is similar to the overall left‐right effect in the one‐dimensional model, while nativism has a more limited, albeit significant, positive effect. Populism remains a significant and relevant predictor, but its effect size is reduced substantially.

We thus find that parties' populism, their nativism and their left‐right ideology matter for their conception of the people. While populism is relevant for the definition of the people, we find that parties' economic and cultural positions trump the effect of populism when it comes to an economic or cultural understanding of the people, respectively. The very high R ![]() in all four models indicates that our four predictors – populism, overall left‐right position, economic left‐right position and nativism – capture almost all variation in the dependent variables. Finally, our models indicate that it is useful to estimate both a one‐dimensional model and a two‐dimensional model. While the overall left‐right position captured the effect of nativism in the model predicting cultural conceptions of the people, the variable captures left‐right economic positions in the model predicting economic conceptions of the people.

in all four models indicates that our four predictors – populism, overall left‐right position, economic left‐right position and nativism – capture almost all variation in the dependent variables. Finally, our models indicate that it is useful to estimate both a one‐dimensional model and a two‐dimensional model. While the overall left‐right position captured the effect of nativism in the model predicting cultural conceptions of the people, the variable captures left‐right economic positions in the model predicting economic conceptions of the people.

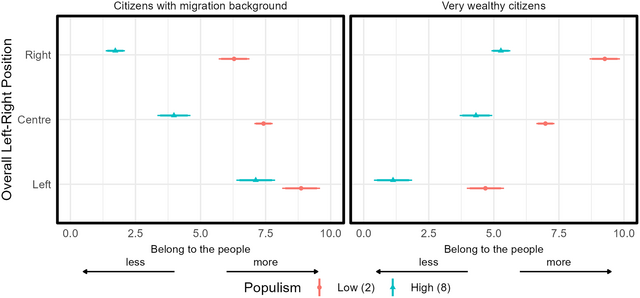

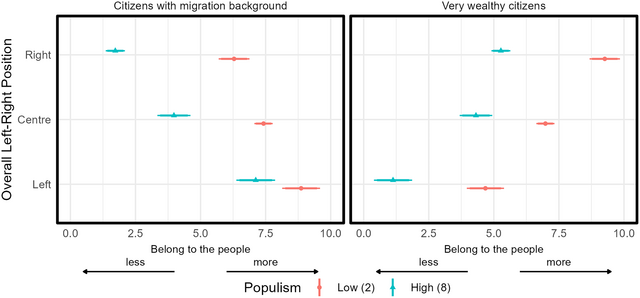

In the second step, we investigate whether the relationship between populism and group perceptions is moderated by parties' ideological positions. Figure 4 plots the findin—‐gs of the interaction between populism and overall left‐right ideology.

Figure 4. ‘The people’; the interaction between populism and ideology.

Note: Ranges represent 95 per cent and 90 per cent confidence intervals. Table B5 in the Supporting Information presents the regression tables.

We start with the cultural conception of the people. We find that highly populist parties across the political spectrum hold more culturally exclusive conceptions of the people than their ideological counterparts scoring low on populism (also see Figure D1 in the Supporting Information for the marginal effects). The negative effect of populism is most pronounced for right‐wing parties: right‐wing populists adhere to culturally exclusive conceptions of the people. Left‐wing parties are much less likely to exclude migrants from ‘the people’. Yet, also among left‐wing parties highly populist parties are more exclusionary compared to their non‐populist left‐wing counterparts. As Figure D4 and Table B6 in the Supporting Information show, this interaction effect between populism and overall left‐right ideology on cultural conceptions of the people is primarily driven by parties' nativism.

We move on to the economic conception of the people and the interaction between parties' populism and their left‐right positions (the right facet in Figure 4). Left‐wing, centrist and right‐wing parties are substantially more likely to include wealthy citizens in their conception of the people if they also score low on populism, while populist parties are substantially more exclusionary in economic terms. In line with prior case study evidence, highly populist left‐wing parties are generally most likely to exclude the wealthy from the people.Footnote 8

Overall, we find that populism, independent from political ideology, is a relevant predictor of group belonging perceptions. At the same time, the thick ideological leaning is the strongest predictor of parties' cultural and economic conceptions of the people. Our findings also outline the importance of considering the interaction between populism and parties' ideological identity. While economic left‐right positions are a strong predictor of perceptions of ‘very wealthy citizens’, its explanatory power of stances on ‘citizens with migration background’ is limited. The opposite holds for nativism.

Who belongs to ‘the elite’?

We now move on to parties' perceptions about which groups belong to the elite. Figure 5 shows the Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis of four models with each a different dependent variable. The dependent variables capture to what extent experts perceive the party to define the elite in political terms (‘politicians'), through the media (‘journalists'), in economic terms (‘CEOs') and socio‐cultural terms (‘academics'). We again plot both a one‐dimensional – with overall left‐right as an ideological predictor – and a two‐dimensional model with economic left‐right position and nativism as ideological predictors.

Figure 5. Populism, ideology and ‘the elite’.

Note: R ![]() of the elite (pol.): one‐dimensional model = 0.43 / two‐dimensional model = 0.45. R

of the elite (pol.): one‐dimensional model = 0.43 / two‐dimensional model = 0.45. R ![]() of the elite (media): one‐dimensional model = 0.49 / two‐dimensional model = 0.55. R

of the elite (media): one‐dimensional model = 0.49 / two‐dimensional model = 0.55. R ![]() of the elite (econ.): one‐dimensional model = 0.43 / two‐dimensional model = 0.44. R

of the elite (econ.): one‐dimensional model = 0.43 / two‐dimensional model = 0.44. R ![]() of the elite (cult.): one‐dimensional model = 0.56 / two‐dimensional model = 0.59. Ranges represent 95 per cent and 90 per cent confidence intervals. Tables B3 and B4 in the Supporting Information show the regression results for all four models.

of the elite (cult.): one‐dimensional model = 0.56 / two‐dimensional model = 0.59. Ranges represent 95 per cent and 90 per cent confidence intervals. Tables B3 and B4 in the Supporting Information show the regression results for all four models.

Starting with the main effects of populism, we see that populism is a statistically significant predictor of elite perceptions for all four groups. While there are minor differences, this effect holds both in the one‐ and two‐dimensional models. Parties with high levels of populism are more likely to perceive politicians, journalists, CEOs and academics as part of the elite. The effect of populism is most pronounced for media elites. This could reflect that populists often feel that the media is part of ‘the establishment’, as opposed to a check to executive power.

Turning to the effects of the overall left‐right position on parties’ elite conceptions, we find that it has no significant effect on political elites. The small positive effects on media elites and socio‐cultural elites indicate that right‐wing parties are more likely to see these groups as part of the elite. The negative effect of the overall left‐right position on economic elites suggests that right‐wing parties are less likely to see CEOs as part of the elite.

The two‐dimensional model allows us to disentangle cultural and economic connotations of the overall left‐right variable. For all four types of elites, nativism is the weakest predictor for elite conceptions. We find significant negative effects of nativism on perceptions of politicians as elites and as CEOs as elites. That is, the more nativist a party is, the less it considers politicians and CEOs to be part of the ‘elite’. These effects however are substantially very small. In addition, nativism does not uniquely explain perceptions of journalists and academics. With respect to parties’ economic positions, we find that the more economically left‐wing a party is, the more likely it is that it considers CEOs to be part of the elite. By contrast, the more economically right‐wing a party is, the more likely it believes that politicians, journalists and academics are part of the elite.Footnote 9

As in the previous analysis on belonging to the people, we are interested in understanding whether these effects of populism depend on political ideology. Hence, we replicate the analysis of interaction terms for our analysis of elite conceptions. Figures D6 and D7 in the Supporting Information show the main findings.Footnote 10 We find that populism moderates the effect of left‐right positions on media elites, with highly populist parties across the political spectrum being more likely to see journalists as elites. With respect to economic elites, we find that highly populist left‐wing parties are significantly and substantially more likely to see CEOs as elites than all other parties. Yet, also populist parties on the right are more likely to see CEOs as elites compared to their non‐populist counterparts, albeit at lower levels than left‐wing parties. Finally, with respect to socio‐cultural elites, populism only has a significant effect among right‐wing parties. In line with anecdotal evidence, we thus find that right‐wing populists are more likely to see academics as elites.

Conclusion

This research note set out to examine how political parties in Europe differ in their conceptions of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. We focused on parties’ degree of populism and their ideological profile, measured both in a one‐ and a two‐dimensional way. We do so using unique expert survey data of the 2023 wave of the POPPA (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Meijers and Huber2024a; Reference Zaslove, Meijers and Huber2024b) to measure parties’ conceptions of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. By measuring populism as a continuous variable, we capture the counterfactual of parties' lack of populist ideology. As such, we assess the explanatory effect of populism alongside parties' ideological characteristics.

In line with arguments previously made in the literature (March, Reference March2012; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), we find that parties' degree of populism as well as their left‐right and nativist ideology matters for their conception of the people. When it comes to cultural conceptions of the people, parties' nativism is the defining factor. Parties' populism however strengthens the negative effect of nativism on parties' inclusion of citizens with a migration background as belonging to ‘the people’. With respect to economic definitions of the people, parties' economic left‐right position is key – with populism again functioning as a moderator that strengthens this effect: highly populist left‐wing parties do not consider ‘wealthy citizens’ to be part of the people.

Yet, populism has a negative effect on parties' inclusion of citizens with a migration background for both left‐wing, centrist, and right‐wing populists. The effect of populism is most pronounced on the right: while non‐populist right‐wing parties score similar to left‐wing parties, populist right‐wing parties do not consider people with a migration background to be part of ‘the people’. With respect to the inclusion of wealthy citizens in ‘the people’, we find that particularly highly left‐wing populist parties espouse an exclusionary trait in this respect. On the other end of the spectrum, non‐populist right‐wing parties are most inclusionary with respect to rich citizens. But also among centrist and right‐wing parties populism matters: populists are consistently more exclusionary towards wealthy citizens. All in all, these findings confirm that right‐wing populists predominantly have an ethnic, cultural conception of ‘the people’ – excluding people with a migration background, whereas left‐wing populist parties adhere to an economic conception of ‘the people’ – excluding wealthy citizens. That said, we see that also left‐wing populists have a more culturally exclusionary view than left‐wing non‐populists and that right‐wing populists also have a more economically exclusionary view than non‐populist right‐wing parties. These findings have important implications for which societal groups parties consider to be legitimate ‘sovereigns’. Future research should therefore examine how parties‘ conceptions of the people affect their views on democracy.

With respect to parties’ construction of ‘the elites’, we see some heterogeneity across different types of elites. Populism, not left‐right ideology or nativism, is the key predictor in explaining parties' conceptions of the elite. With respect to an economic conception of elites, we find that left‐wing parties are more likely to consider CEOs to be elites than right‐wing parties. With respect to socio‐cultural elites (i.e., academics), we find that only right‐wing populists are more likely to consider them to be elites than other groups.

All in all, these findings provide the first comparative empirical test of parties' conceptions of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. In line with previous findings, we see clear differences in the conception of the people among left‐ and right‐wing populists. At the same time, we find that both populism as well as parties' host ideology have independent effects on parties' construction of the people. With respect to parties' understanding of elites, we also see that populism and left‐right ideology interact in varying ways.

We believe these are important findings which empirically confirm previously theorized patterns on how populist parties define the people and the elite. However, our study is not without limitations. We only examine a limited number of groups to belong that may be the people or the elite. Qualitative and case study research is well placed to examine in future research the extent to which (populist) parties include or exclude specific societal groups in their conceptions of the people in specific national political contexts. Moreover, the semantic meaning of societal groups may differ across national and political contexts, which we cannot capture with our one‐size‐fits‐all expert survey measure. For instance, while certain parties may welcome certain ‘citizens with a migration background’ with open arms, they explicitly close the door to others. Text‐based analyses in future research are well‐placed to explore these questions further. Finally, the scope of this research note limits the range of explanatory factors we can investigate. We encourage future studies to delve into other significant moderating factors, such as government participation, organizational transformations and historical legacies. Despite these limitations, we believe that our study makes a valuable contribution to understanding how (populist) parties construct the notion of ‘the people’.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the excellent and constructive comments by the editors and reviewers of the European Journal of Political Research. An earlier versions of this paper has been present at the ECPR General Conference in Prague (September 2023). We thank everyone envolved in the discussion. The 2023 Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey would not be possible without the expertise of the 324 experts who participated in the expert survey. We would like to thank all country experts for dedicating their time to the expert survey.

Data availability statement

The 2023 Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) data are publicly available on Harvard Dataverse at Zaslove, Andrej; Meijers, Maurits; Huber, Robert, 2024, Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey 2023 (POPPA), https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RMQREQ, Harvard Dataverse. The data can also be explored interactively with the POPPA Shiny app, which can be accessed at poppa‐data.eu. The replication data for this research note is also available on Harvard Dataverse: Meijers, Maurits; Robert A. Huber; Andrej Zaslove, 2025, Replication Data for The Anatomy of Populist Ideology: How Political Parties Define “The People” and “The Elite”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ECMQ4M, Harvard Dataverse.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1