Introduction

Purple nutsedge is one of the most persistent and common weeds in many crops worldwide, specifically in the southeastern United States (Dowler Reference Dowler1998). Purple nutsedge is known as one of the worst weeds in the world due to its perennial nature and ability to propagate asexually through rhizomes and tubers (Holm et al. Reference Holm, Plucknett, Pancho and Herberger1977; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Renner and Penner2002; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Bond and Scott2013; Stoller and Sweet Reference Stoller and Sweet1987). Purple nutsedge is difficult to control in various row crops mainly due to its tuber longevity and sprouting ability throughout the growing season (Keeley Reference Keeley1987; Wills Reference Wills1987). Reduced competition from annual weeds due to effective control measures is also responsible for increased purple nutsedge in agricultural fields (Hauser Reference Hauser1971). Purple nutsedge interference can cause yield reductions of up to 45% to 58% in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and soybean (Glycine max L.), Mississippi’s top two crops in terms of production value (Guantes and Mercado Reference Guantes and Mercado1975; Kondap et al. Reference Kondap, Ramakrishna, Reddy and Rao1982; USDA–NASS 2024). A single purple nutsedge tuber can result in a chain-like pattern that can spread up to 90 cm within 2 mo, and if left uncontrolled, can have a ground cover of 7.6 and 56.7 m2 in the first and second seasons, respectively (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1972; Wills Reference Wills1998).

Even though the development of genetically modified herbicide-resistant crops has expanded the postemergence options for selective nutsedge control, most herbicides available today for nutsedge control are only able to suppress the plant and not completely control it due to their inability to kill the dormant underground tubers and rhizomes (Bryson et al. Reference Bryson, Reddy and Molin2003). In Mississippi cropping systems, glyphosate, glufosinate, bentazon, halosulfuron, and trifloxysulfuron are currently labeled for nutsedge management. To achieve maximum efficacy, the label recommends herbicide applications when plants are less than 15 cm tall or at the 3- to 5-leaf stage. Higher rates might be needed to achieve complete control if nutsedge plants are 15 cm or taller.

Knowledge of purple nutsedge control and related herbicide injury at different growth stages is limited across different cropping systems, vegetables, and turf. Several studies have addressed this issue in terms of nutsedge biomass (i.e., shoot and root [including tuber] biomass) degradation by herbicides (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Troxler, Wilcut and Smith2008; Zangoueinejad et al. Reference Zangoueinejad, Sirooeinejad, Alebrahim and Bajwa2022). However, little is known about new shoot development during the period after a herbicide is applied and shoot regrowth after the aboveground portion is dead or injured. Therefore, the objectives of this research were to 1) study the efficacy of commonly labeled herbicides on purple nutsedge control in terms of visual injury, shoot and root biomass, new shoot emergence, and shoot regrowth after cutting; and 2) determine herbicide efficacy at two different plant heights (growth stages).

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Experimental Setup

A greenhouse study was conducted during the summer of 2024 at the USDA-ARS Crop Production Systems Research Unit, in Stoneville, Mississippi. Purple nutsedge seedlings were obtained from two locations on a nearby soybean research plot (33.442°N, 90.909°W; 33.445°N, 90.896°W). The seedlings with intact tubers were brought to the greenhouse and planted immediately on an aluminum tray (100 cm × 70 cm) for propagation. The aluminum tray contained a custom growing mix (Jolly Gardner®; Old Castle Lawn and Garden, Atlanta, GA), and was regularly watered and fertilized (N:P:K 24:8:16; Miracle Grow, Marysville, OH) at the initial establishment stage to provide a continuous source of purple nutsedge seedlings for the study. The seedlings (with tuber attached) from the mother plants were transplanted into individual 10 cm × 10 cm square pots in the greenhouse. Conditions inside the greenhouse were maintained at 28/22 ± 3 C day/night temperature with a 12-h photoperiod supplemented by metal halide lamps at 560 µmol m−2 s−1.

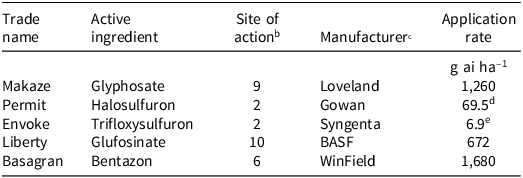

The experiment was conducted in a randomized complete block design with six treatments and five replications separately for each growth stage. The treatments consisted of a nontreated control, glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1, glufosinate at 672 g ai ha−1, bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha−1, halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha−1, and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha−1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to the spray solution with trifloxysulfuron treatments, and crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments. Detailed information on herbicides used to control purple nutsedge species such as trade name, active ingredient, site of action, and manufacturer name are listed in Table 1. Plants were treated with herbicides at two different growth stages (10 to 15 cm and 15 to 20 cm). All herbicide treatments were applied using a Generation 3 research track sprayer (DeVries Manufacturing, Hollandale, MN) calibrated to deliver 187 L ha−1 at 280 kPa. After spraying, plants were returned to the greenhouse and watered as needed. The experiment was repeated twice over two runs under the same greenhouse conditions.

Table 1. Herbicide treatments for purple nutsedge control used in this study. a

a Abbreviations: ai, active ingredient; SOA, site of action; WSSA, Weed Science Society of America.

b Herbicide site of action (as categorized by the Weed Science Society of America): 2, inhibition of acetolactate synthase; 6, inhibition of photosystem ll; 9, inhibition of enolpyruvyl shikimate phosphate synthase; 10, inhibition of glutamine synthetase.

c Manufacturer locations: BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC; Gowan, Yuma, AZ; Loveland Products, Greenville, MS; Syngenta Crop Protection, Greensboro, NC; Winfield United, Arden Hills, MN.

d A crop oil concentrate was added at 10 mL L−1.

e Induce (a nonionic surfactant) was added at 2.5 mL L−1.

Data Collection and Analysis

Visible purple nutsedge control was evaluated weekly after herbicide applications and continued for 4 wk after the final application. Evaluations were made on a scale of 0% to 100%, where 0% represented no nutsedge control and 100% represented complete nutsedge control (Frans and Talbert Reference Frans and Talbert1986). The numbers of newly emerging shoots were recorded weekly starting at 14 d after treatment (DAT) and continued until 28 DAT. At 28 DAT, the aboveground shoot biomass of individual plants was harvested, placed in a paper bag, dried at 65 C for 72 h, and weighed to obtain the shoot biomass for each treatment. After the aboveground foliage was harvested at 28 DAT, plants were allowed to regrow for the next 21 d. Root biomass and shoot regrowth numbers were then recorded at 21 d after cutting (DAC) the aboveground foliage. Both shoot and root biomass data were expressed as a percentage reduction relative to that of the nontreated check using the following equation:

where Y represents percent shoot/root biomass reduction, DWc is the shoot/root biomass of the nontreated control, and DWt is the shoot/root biomass of treated plants at 28 DAT and 21 DAC.

Data were transformed to percent nutsedge control and biomass reductions relative to nontreated plants for further statistical analyses. Treatments and growth stages were set as fixed effects, while replications were set as random effects for analysis of variance. The experiment was a randomized complete block design. The pots were blocked according to the greenhouse’s exposure to direct sunlight, which varied east to west during daylight. Every treatment’s replication was represented in each block. Fixed and random effects were analyzed nested within blocks. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for the normality test, and Levene’s test was used to test the homogeneity of variance.

A generalized linear mixed (GLM) model was used to assess response variables measured at four different days after treatment within each replicate, using repeated measures ANOVA for the two-factor experimental design. The GLM procedure was employed to specify both within-subject and between-subject factors (repeated measures). Data from the two growth stages were subjected to ANOVA and analyzed separately. Means were separated at the 5% level of significance using Fisher’s protected LSD test, declared significant at P ≤ 0.05. The analysis was performed using SAS software (v.9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results and Discussion

Percent Purple Nutsedge Control

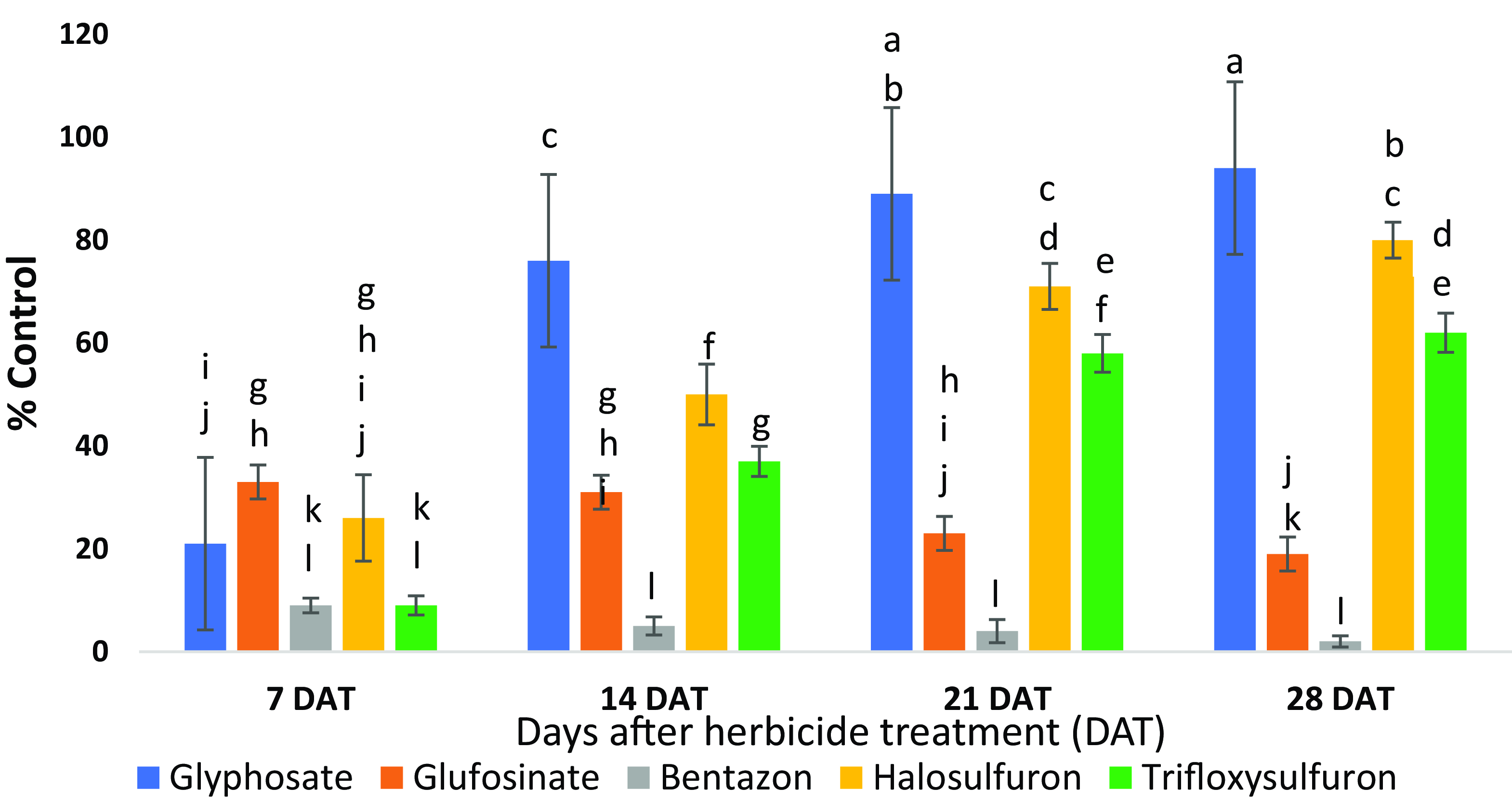

Of the five postemergence herbicides evaluated in this study, glyphosate was the most effective followed by halosulfuron for purple nutsedge control when applied at both growth stages (Figures 1–4). At 28 DAT, purple nutsedge control at the 10- to 15-cm and 15- to 20-cm growth stages was, respectively, 97% and 94% with glyphosate, 85% and 80% with halosulfuron, 76% and 62% with trifloxysulfuron, 42% and 19% with glufosinate, and 18% and 2% with bentazon. Halosulfuron will likely exhibit activity similar to that of glyphosate by 5 to 6 wk after application. In general, herbicides such as halosulfuron and trifloxysulfuron that inhibit acetolactate synthase act slowly, taking up to 14 d for herbicide symptoms to appear and up to 5 to 6 wk to achieve 100% control of susceptible weeds (Derr Reference Derr2012).

Figure 1. Purple nutsedge control at 7, 14, 21, and 28 d after treatment (DAT) with herbicides applied at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage in the greenhouse. Treatments associated with the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05). Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean for each treatment and time assessment.

Figure 2. Purple nutsedge control at 7, 14, 21, and 28 d after treatment (DAT) with herbicides applied at the 15- to 20-cm growth stage in the greenhouse. Treatments associated with the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05). Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean for each treatment and time assessment.

Figure 3. Purple nutsedge control 28 d after treatment (DAT) with herbicides sprayed at 1× rates. Herbicides were applied to plants at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage. Herbicide rates (1×) were as follows: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

Figure 4. Purple nutsedge control 28 d after treatment (DAT) with herbicides sprayed at 1× rates. Herbicides were applied to plants at the 15- to 20-cm growth stage. Herbicide rates (1×) were as follows: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

At 7 DAT, all herbicides except bentazon controlled purple nutsedge equivalently regardless of growth stage. However, differences became apparent at 14 and 21 DAT (Figures 1 and 2). Glufosinate and bentazon were weakest against purple nutsedge at 28 DAT. Plants recovered quickly from the initial injury with significant regrowth just 2 wk after glufosinate and bentazon applications (Figures 1 and 2). The least effective herbicide was bentazon with only 2% control at 28 DAT, when applied to plants at the 15- to 20-cm stage.

In this study, glyphosate was the most effective herbicide followed by halosulfuron for purple nutsedge control (>90%) when applied at both growth stages (Figures 1–4). Edenfield et al. (Reference Edenfield, Brecke, Colvin, Dusky and Shilling2005) found similar purple nutsedge control levels in the field with a single postemergence application of glyphosate to soybean and for a sequential application to cotton. In a 3-yr field study, Reddy and Bryson (Reference Reddy and Bryson2009) reported 48% to 100% purple nutsedge control when it grew among corn (Zea mays L.) plants and 81% to 100% control when it grew among soybean, demonstrating the effectiveness of glyphosate in purple nutsedge management. At 28 DAT, halosulfuron demonstrated 80% to 85% purple nutsedge control at both growth stages (Figures 1–4). A previous field study reported >80% purple nutsedge control when halosulfuron was applied early postemergence followed by late postemergence, and did not differ from a single halosulfuron early postemergence application (Brecke et al. Reference Brecke, Stephenson and Unruh2005). Czarnota and Bingham (Reference Czarnota and Bingham1997) reported 95% purple nutsedge control after a single halosulfuron application 6 wk after treatment of turfgrass. Trifloxysulfuron showed 62% to 76% purple nutsedge control at two different growth stages 28 DAT (Figures 1–4). A previous report of experiments carried out under field conditions reported similar control levels (58% to 77%) of purple nutsedge treated with trifloxysulfuron (Gannon et al. Reference Gannon, Yelverton and Tredway2012). In our study, there was an increasing trend in percent control due to halosulfuron and trifloxysulfuron throughout the 4-wk duration. As previously discussed, herbicides such as halosulfuron and trifloxysulfuron that inhibit acetolactate synthase act more slowly than other herbicides (Derr Reference Derr2012).

Glufosinate effectively controlled purple nutsedge in cotton, and when applied as a tank–mix with trifloxysulfuron, control was increased to 94% (Everman et al. Reference Everman, Burke, Allen, Collins and Wilcut2007). However, our current greenhouse study showed 42% and 19% purple nutsedge control with glufosinate at both growth stages (Figures 1–4). Similar lower purple nutsedge density control levels were observed with glufosinate applied at 656 g ai ha−1 to vegetable production systems (Sharpe and Boyd Reference Sharpe and Boyd2019). Glufosinate, a contact herbicide, kills only the aboveground portions of the purple nutsedge plant after application and may not eradicate the extensive underground root system due to a lack of systemic translocation (Corbett et al. Reference Corbett, Askew, Thomas and Wilcut2004). The least effective herbicide in this study, demonstrating only 2% purple nutsedge control, was bentazon, applied at the 15- to 20-cm growth stage. Bentazon controlled 43% of purple nutsedge when it was applied to glyphosate-resistant soybean, and control increased to 68% when it was applied as a postemergence herbicide following a preemergence application of metolachlor, sulfentrazone, or chlorimuron (Akin and Shaw Reference Akin and Shaw2001). Bentazon applied alone is known to have little to no activity against purple nutsedge (Johnson Reference Johnson1975).

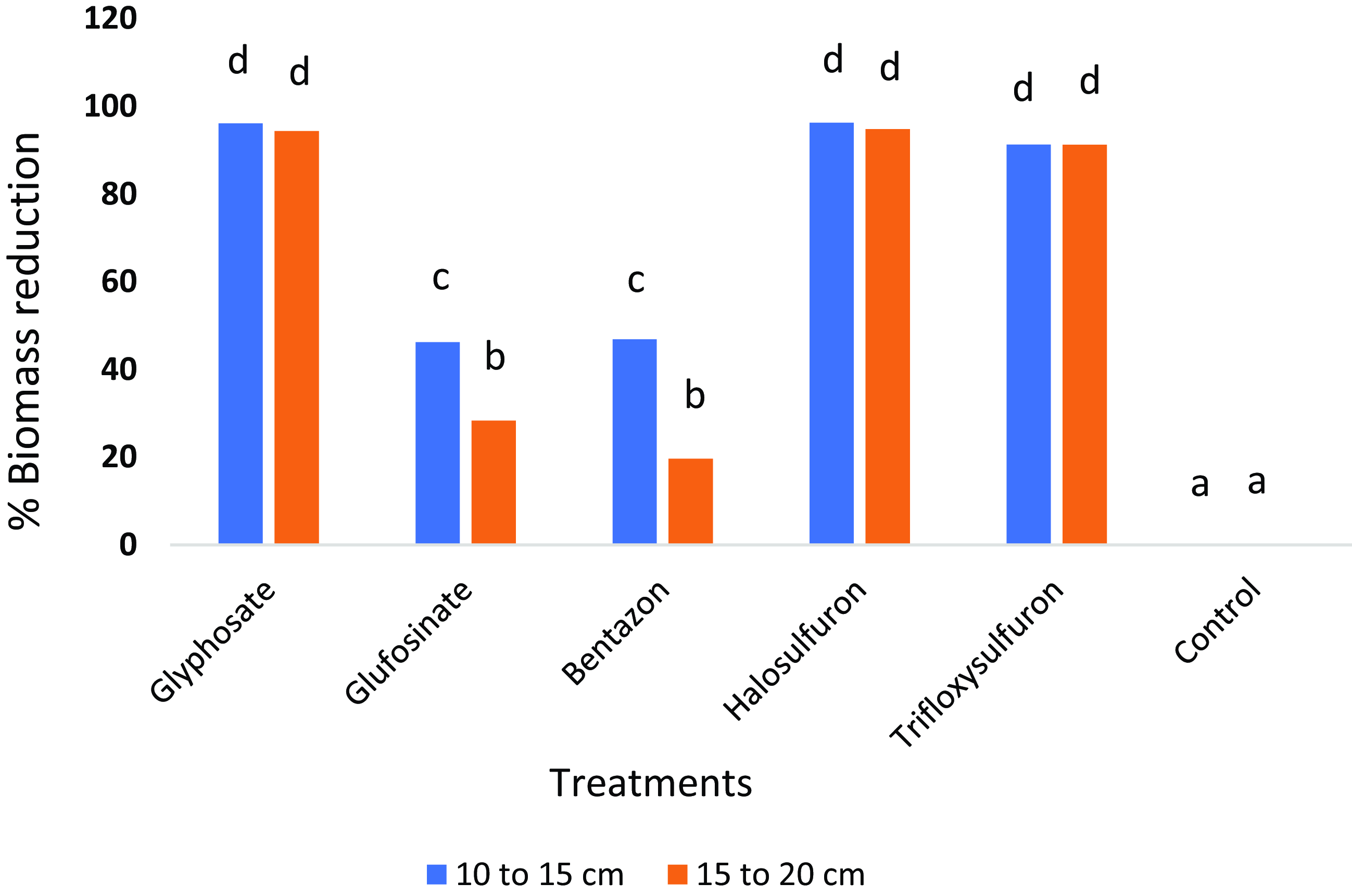

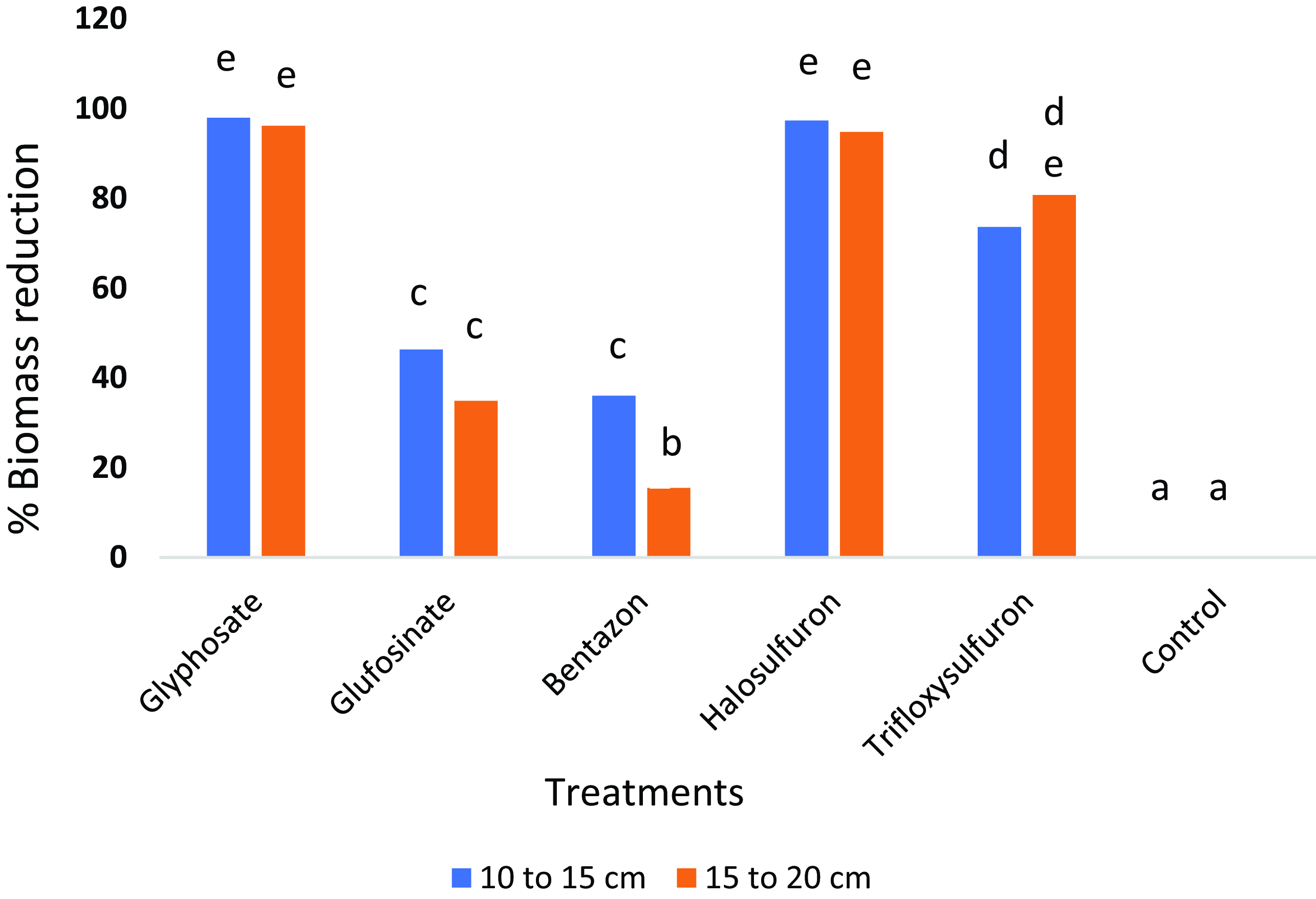

Purple Nutsedge Shoot and Root Biomass

In the present study, glyphosate, halosulfuron, and trifloxysulfuron maximally reduced the shoot biomass of purple nutsedge by more than 90% compared with the nontreated (Figure 5). Shoot biomass reduction at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage was not significantly different from that of plants at the 15- to 20-cm stage, demonstrating the similar efficacy of these herbicides at these stages. Similarly, root biomass was reduced by more than 90% when glyphosate and halosulfuron were applied, with no significant differences between the two plant growth stages (Figure 6). Glufosinate and bentazon treatments resulted in the least shoot and root biomass reduction, ranging from 20% to 46% (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Purple nutsedge shoot biomass reduction relative to the nontreated control 28 d after treatment. Shoot biomass reduction is shown for herbicide treatments at two purple nutsedge growth stages, 10 to 15 cm and 15 to 20 cm. Treatments associated with the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6. Purple nutsedge root biomass reduction relative to the nontreated control 21 d after cutting the aboveground shoot. Root biomass reduction is shown for herbicide treatments at two purple nutsedge growth stages, 10 to 15 cm and 15 to 20 cm. Treatments associated with the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Previously, Burke et al. (Reference Burke, Troxler, Wilcut and Smith2008) reported reductions in shoot and root dry weight of two plant heights (10 to 15 cm and 20 to 30 cm) of 62% to 73% when glyphosate was applied at 1,120 g ai ha–1, 55% to 79% when trifloxysulfuron was applied at 4 and 5 g ai ha–1, and 46% to 63% when glufosinate was applied at 400 g ae ha–1. The 55% root reduction in purple nutsedge after trifloxysulfuron application was found to be dependent on weed size, especially at 5 g ai ha–1 (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Troxler, Wilcut and Smith2008). In the present study, applying higher rates of glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1 and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1 likely reduced shoot biomass by more than 90% (Figure 5). Similar to the Burke et al. (Reference Burke, Troxler, Wilcut and Smith2008) study, trifloxysulfuron treatment reduced root biomass by 73% to 80%, although in our study, growth stage had no major impact on control due to the higher rates we used (Figure 6). Glufosinate applied at 400 g ae ha–1 reduced shoot and root biomass by 46% to 63%, with no significant differences between different growth stages (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Troxler, Wilcut and Smith2008). Our study found significant differences in shoot biomass reductions following glufosinate and bentazon applications at both growth stages (Figure 5).

In the current study, compared with the nontreated plants, purple nutsedge shoot biomass was reduced by more than 90% when halosulfuron was applied (Figure 5). In contrast, in another study, halosulfuron applied preemergence at 50 g ai ha–1 to a tomato crop resulted in a reduction in purple nutsedge shoot biomass by only 54% to 63% (Zangoueinejad et al. Reference Zangoueinejad, Sirooeinejad, Alebrahim and Bajwa2022). This demonstrates that halosulfuron applied postemergence is far more effective in controlling purple nutsedge than a preemergence application.

New Shoot Emergence and Shoot Regrowth

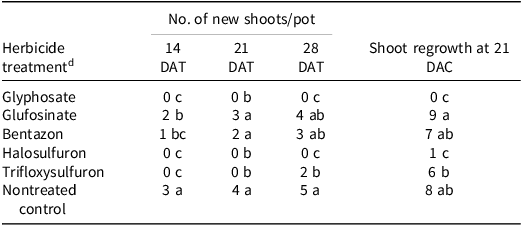

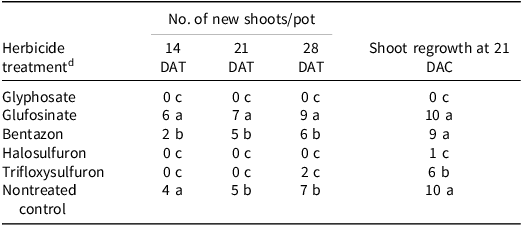

In general, purple nutsedge exhibited the highest new shoot emergence and shoot regrowth when treatments were applied at 15- to 20-cm stage rather than at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage, highlighting the importance of plant height in herbicide efficacy and weed control (Tables 2 and 3). At 28 DAT, the highest new shoot count at the 10- to 15-cm and 15- to 20-cm growth stages occurred after applications of glufosinate and bentazon (Tables 2 and 3). A previous study of purple nutsedge found that halosulfuron and glyphosate treatments resulted in fewer viable shoots under a daily watering regime compared to a weekly regime at 30 DAT (Reference Le and MorellLe and Morrel 2021). In the current study, no new shoot emergence was recorded at 28 DAT with glyphosate and halosulfuron (Tables 2 and 3). The difference in shoot numbers observed after glyphosate and halosulfuron treatments may be due to the differences in herbicide rates used and water regime status.

Table 2. Effect of postemergence herbicides on the number of new shoots of purple nutsedge at 14, 21, 28 d after treatment, and shoot regrowth 21 d after cutting. a – c

a Abbreviations: DAC, days after cutting; DAT, days after treatment.

b Herbicides were sprayed when plants were at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage. The new shoot count and shoot regrowth counts are the average of five replications from two independent runs.

c Means within a column with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test at a = 0.05.

d Herbicides were applied at 1× rates: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and a crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

Table 3. Effect of postemergence herbicides on number of purple nutsedge new shoots at 14, 21, and 28 d after treatment; and shoot regrowth 21 d after cutting. a – c

a Abbreviations: DAC, days after cutting; DAT, days after treatment.

b Herbicides were sprayed when plants were at the 10- to 15-cm growth stage. The new shoot count and shoot regrowth counts are the average of five replications from two independent runs.

c Means within a column with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test at α = 0.05.

d Herbicides were applied at 1× rates: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and a crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

A similar trend was observed with shoot regrowth 21 d after cutting the aboveground shoot. Compared to the other treatments, the maximum shoot regrowth at both growth stages occurred when glufosinate and bentazon were applied (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 7 and 8). No shoot regrowth was observed after glyphosate treatment. Interestingly, there was significant shoot regrowth after trifloxysulfuron treatment at both stages (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 7 and 8). The greatest shoot regrowth occurred in the nontreated control plants.

Figure 7. Purple nutsedge regrowth 21 d after cutting (DAC) the aboveground shoot. Herbicides at 1× rates were applied at 10- to 15-cm growth stage. Herbicides rates (1×) were as follows: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

Figure 8. Purple nutsedge regrowth 21 d after cutting (DAC) the aboveground shoot. Herbicides at 1× rates were applied to plants at the 15- to 20-cm growth stage. Herbicides rates (1×) were as follows: glyphosate at 1,260 g ai ha–1; glufosinate at 672 g ae ha–1; bentazon at 1,680 g ai ha–1; halosulfuron at 69.5 g ai ha–1; and trifloxysulfuron at 6.9 g ai ha–1. A nonionic surfactant (2.5 mL L−1) was added to trifloxysulfuron treatments and crop oil concentrate (10 mL L−1) was added to halosulfuron treatments.

As discussed above, unlike systemic herbicides such as glyphosate and halosulfuron, glufosinate acts as a contact herbicide, desiccating only the aboveground portions of purple nutsedge plants and potentially failing to reach the extensive underground root system. This sustains the underground tubers and buds, enabling them to sprout under favorable conditions. Bentazon exhibits little to no activity against purple nutsedge (Johnson Reference Johnson1975), leading to increased shoot emergence and regrowth throughout the growing season.

Practical Implications

Herbicide activity is affected by the weed growth stage at application. In this research, the activity of postemergence herbicides on purple nutsedge was studied when plants were sprayed at the 10- to 15-cm and 15- to 20-cm growth stages. The effects of herbicides were visually noticeable 7 to 10 d after their initial application. Herbicide activity increased over time for glyphosate, halosulfuron, and trifloxysulfuron, whereas the activity initially increased and then decreased for glufosinate and bentazon by 28 DAT.

Glyphosate and halosulfuron are the two most effective herbicide options for achieving complete purple nutsedge control. Trifloxysulfuron controlled purple nutsedge by up to 76%; however, shoot regrowth might be an issue after the death of the aboveground portion. Glufosinate and bentazon were ineffective at controlling purple nutsedge. Glufosinate and bentazon use can be limited to initially suppressing purple nutsedge rather than achieving complete weed control. A commercially acceptable weed control might be achieved by tank mixing glufosinate and bentazon with other herbicides that have other modes of action. Overall, herbicide activity on purple nutsedge was greater when plants were sprayed at the 10- to 15-cm stage rather than at the 15- to 20-cm growth stage. Results indicate that both herbicide mode of action and application timing are critical for purple nutsedge management.

Acknowledgments

We thank Earl Gordon, Efron Ford, and Russell Coleman for their technical assistance in greenhouse work. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.