In November 1988, as the Soviet war effort in Afghanistan was descending into disaster, a popular band from Soviet Uzbekistan traveled to Afghanistan to perform for their Central Asian compatriots from across the Hindu Kush.Footnote 1 The band, Yalla, were experienced performers: since the early 1970s, they had captivated audiences around the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, playing major stadiums from Moscow to Dresden, and drawing audiences from Morocco to Mexico and Mongolia. When visiting Afghanistan, Soviet bands often performed for Soviet troops; indeed, Yalla had already done so in 1980 before what they described as an audience of tens of thousands of soldiers.Footnote 2 The request that, this time, Yalla perform for Kabulis must have been some sort of last-ditch effort on the part of the Soviet authorities and their Afghan partners to maintain good will as the Soviet war effort collapsed around them. Taking the stage in Kabul that evening, the band began performing their biggest hits—the Russian-language songs that had catapulted them to celebrity across the socialist bloc.Footnote 3 Surely they played “Uchquduq,” the synth-pop hit that made their name in the canon of Soviet pop music. Perhaps Yalla performed The Musical Teahouse, the title track from their LP of the previous year, with its interludes on the Arab ‘oud (lute), doira (Uzbek tambourine), and electric guitar. But as the show progressed, some members of the Uzbek-speaking Kabuli public responded with frustration, heckling the band. “Sing in Uzbek!” (Uzb. o’zbekcha o’qi), they shouted, using an Afghan dialect that sounded strange to the band members. The band performed all the Uzbek songs they knew and soon ran out of repertoire in that language. Clearly, Yalla appealed to some Afghans, but the attempt to facilitate mutual recognition among the Soviet East and its foreign “Eastern” neighbors seemed, at best, imperiled. It did not improve the atmosphere when a power outage interrupted the concert and heavily armed guards emerged to encircle the band on stage, as if concerned that the Kabulis might end up a threatening enemy rather than an adoring audience. Instead of recognizing Soviet Uzbeks as their brothers across the border, some Afghan audiences might fail to recognize them as kin at all.

Playing a show in a foreign war zone on behalf of an occupying force in the process of withdrawal is undoubtedly a hard gig, to say the least; and the power outage passed quickly and uneventfully. But Yalla’s experience with their Kabul hecklers reveals more than the difficulty of that specific gig: it reveals some of the internal tensions in their performance practice. Over the course of decades, Yalla made its career by performing the East: not just in musical style, but in lyrics, costumes, set designs, choreography, and marketing. After getting its start as an amateur group in Tashkent in the late 1960s, the band quickly gained popularity not just in Uzbekistan, but in the entire Soviet Union. Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, Yalla progressively augmented its performance of the East in a series of self-reinventions. It represents a certain vicious irony that the performance of “Easternness” emerging from decades of performance experience would falter before some Uzbek audiences in Kabul—although not, it should be said, in front of all foreign easterners: the first Soviet band to perform in Vietnam, Yalla experienced runaway success at their 1980 performance there, despite being interrupted by a monsoon rainstorm; they were well received in Bahrain and Morocco.Footnote 4 If inconsistently recognizable to their fellow easterners abroad, then, what did the East really mean to Yalla and their audiences?Footnote 5

In this article, I explore Yalla’s shifting uses of the Soviet East over the course of their late Soviet career, examining their work not just as a musical, discursive, or institutional practice but as embodied material performance. Yalla mobilized the East in response to the numerous and interconnected pressures they faced as a Central Asian band (the official Soviet term was VIA, or Vocal-Instrumental Ensemble) in the latter years of the Soviet Union: the Cold War demand for Soviet entertainment that would compete on a global “internationalist” stage; the dynamics of racialization in Soviet space; the economic strains of perestroika and the Soviet collapse; and the band members’ own agenda to elevate Central Asian culture on an all-Soviet stage. After a brief overview of the band and the performance traditions from which it emerged, I trace Yalla’s development over time. I argue that over the course of their Soviet career, the band’s approach to the East changed: it first Sovietized a western musical form, integrating the Beatles with the national cultures that had been forged under Stalin; then, in the early 1980s, it turned to a more theatricalized performance of Soviet Easternness. By the perestroika years, Yalla rendered the East a flashy performative spectacle that responded to global trends in popular culture even as it tapped into longer-term Soviet and Central Asian cultural patterns. At every stage, the band negotiated the multivalent resonances of the East, from its utility for official Soviet internationalism, to its deeper roots in the shared Turco-Persianate cultural sphere that spanned from Central Asia to South Asia and the Middle East, and to its significance to the long history of Russian Orientalism. I root my argument in extensive work in the Soviet-era periodical press on Yalla in both Uzbek and Russian; published memoirs and interviews by members of the band, especially the book-length memoir of early band member Bakhadyr Dzhuraev; interviews with the band’s set and costume designer and several members of Yalla, including the band’s creative and musical directors; and videos of Yalla’s performances.

In addition to contributing the first sustained analytical study of Yalla to the burgeoning scholarship on Central Asian cultures, my analysis adds dimension to an already robust intermedial conversation on late Soviet popular culture in transnational context.Footnote 6 In particular, it shows the ways that what Masha Kirasirova terms the “Eastern international” intersected with Soviet participation in a broader sphere of popular culture through the socialist bloc and the Global South to create a distinctively Soviet popular performance of the East.Footnote 7 Recent scholarship has called attention to the cultural and geopolitical significance of the category of the East in late Soviet culture.Footnote 8 But given just how embodied and spectacular the East was as a category, it is striking that the scholarship on the category looks at it primarily as a textual discourse. This article considers what we might gain from also looking at the East as a performance practice, particularly in the context of what Masha Salazkina has termed “global-popular” culture circulating both in the Second World and Global South beginning in the 1970s.

The case of Yalla brings Central Asia into this conversation, emphasizing the political ambiguities and affective instabilities in their project.Footnote 9 Was Yalla “self-orientalizing”? To be sure. But considering the East as a performance enables us to move beyond static conceptions of identity to consider, instead, the shifting valences of Easternness for Yalla at different times and on different stages. In taking this approach, I respond to a body of scholarship that understands performance as constitutive of racial, ethnic, and gender (dis)identifications.Footnote 10 Through performatively appropriating of a range of representations of the East, Yalla both reified and reimagined the many meanings of Soviet Easternness. Yalla’s performance practice emerges as a site of negotiation between performers, publics, and the economic and political structures they inhabited.Footnote 11

Yalla and Central Asian Performances of the East

Two conceptions of the East inflected Yalla’s performances. From the very earliest years of the Soviet revolutionary project, activists from the Soviet Union and its near abroad mobilized the East to reconfigure the longstanding Turco-Persianate cultural sphere in service of socialist internationalism. For cultural producers from the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Middle Volga, Persian had been a prestige language for centuries, while Turkic-language cultural production partook of shared generic and discursive norms with the Persian. For some easterners in Central Asia and abroad, this multilingual, transregional sphere came to comprise an alternative hub for both socialist and anti-colonial self-organization in the Second and Third Worlds. As Samuel Hodgkin has argued, the (Turco-)Persianate Eastern International mobilized the “preexisting practical unity” of Persianate and Turkic culture across South and Central Asia and the Middle East.Footnote 12 For many writers, poets, and performers from Central Asia, and for their administrators in Moscow, this shared cultural heritage had potential to generate solidarities across Soviet nations and even abroad—and to legitimize pre-revolutionary cultural traditions as authentically revolutionary.

The Turco-Persianate conception of the East contended with another understanding rooted in Russian imperial and European culture. This was the Orientalist East: the luscious but brutal canvases of Vasilii Vereshchagin; the “seductive” melodies of Aleksandr Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances”; the alluring vitality of Aleksandr Blok’s Scythians.Footnote 13 In the late Soviet Union, such cultural narratives became imbricated with the emerging racialization of the people of Central Asia and the Caucasus.Footnote 14 For some Soviet people, easterners were “blacks,” eternally other, permanently locked in a timeless Oriental past. For all the insistence in Marxism-Leninism that national difference would fade away as communism came into its own, by the late Soviet period, many ordinary Soviet people saw national difference as inborn and immutable—even racial.Footnote 15 By the time Yalla emerged, the Turco-Persianate and Orientalist conceptions of the socialist East came into play in the context of Cold War geopolitics and late Soviet nationality affairs, and the nations of Central Asia became show pieces for the affordances of Soviet modernity.Footnote 16

Yalla had deep roots in the performance traditions of all these “Easts.” Yalla’s origins are perhaps best traced through the family history of the band’s co-founder and frontman, Farrux Zokirov, who came from an illustrious lineage of performers in Uzbekistan.Footnote 17 Farrux’s mother, Shoista Saidova, was the first singer to play Leili in Üzeyir Hacıbäyov’s groundbreaking Azerbaijani opera Leili and Majnun, based on a classical Persian narrative poem. Farrux’s father, the singer Karim Zokirov, trained both in classical European music at the Moscow State Conservatory and in Central Asian traditional performance. At the 1937 Dekada of Uzbek Culture in Moscow, he played the lead in the musical drama sometimes dubbed Uzbekistan’s first opera, Gulsara.Footnote 18 Karim and Shoista’s eldest son, Botir, who was also a major influence on Farrux and helped him manage the band, appeared in his first performance on the Dekada stage at just one year old, playing the infant son of his father’s character.

In the early Soviet years, when Farrux’s parents made their careers, performances of the East functioned as part of an official cultural system of national representation. Ten-day-long dekada festivals, like the 1937 event where Shoista and Karim performed, helped both to formulate nascent national categories and to cultivate a sense of multinational belonging.Footnote 19 In the dekada system, each cultural administration—from the Ukrainian (1936) to the Tajik (1941)—produced a pageantry of their modular national culture, featuring a national costume, national instruments, national dance, and ideally, a national opera.Footnote 20 Delineating distinct national cultures was a particularly difficult task for the “brother nations” of the Muslim Caucasus and Central Asia, which prior to 1924 inhabited a shared Turco-Persianate cultural space. The opera became a focal point for this effort, bringing together demonstrations of “modernity” (bel canto singing, European generic norms) with national costume, reworked folk melodies, and, often, a strategically placed national instrument. Composers from the republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus struggled to represent their nations and the East while avoiding hackneyed Orientalism.Footnote 21

Such were the dynamics in the metropole, but the Zokirovs’ repertoire went beyond representing the Uzbek nation and the Soviet East for Muscovites. Karim Zokirov and Shoista Saidova also worked to develop a musical repertoire for entertaining Uzbekistan’s “masses” on their home turf. Over the course of the 1930s and 1940s, Zokirov and Saidova worked alongside Uzbekistan’s rising stars to adapt Central Asian melodies for the first popular Soviet songs. Karim Zokirov toured Uzbekistan’s countryside, earning the adulation of many Uzbek listeners. Even at the end of his life, Farrux Zokirov would cite his father as a major influence, claiming that he decided to join the Communist Party because his own father had. For the Zokirov family, Uzbek national culture was not an exotic aberration from a Soviet Russian norm; it was Soviet culture, full stop.

Twenty years after the dekada where the Zokirovs performed, their son Botir, now a promising young singer, traveled to Moscow to perform at the 1957 Festival of Youth. Eleonory Gilburd has discussed the Festival as a watershed moment in the penetration of western culture into the Soviet Union.Footnote 22 But for Botir and his family, it also inaugurated a new phase in performances of the East. In the context of the Cold War, the nations of Central Asia and the Caucasus became major players in cultural diplomacy to the Third World.Footnote 23 Botir Zokirov’s adult career took off in this moment, embodying not just the pageantry of Stalin-era nationalities policy, but also Cold War politics. Botir performed songs from throughout the foreign East. Fresh from Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit to Uzbekistan in 1955, he performed an Indian film song while wearing a Nehru jacket. His cover of a song by Egyptian Arab singer Farid al-Atrash, which in the Soviet Union came to be known as the “Arab Tango,” rapidly catapulted him to all-Soviet celebrity of a degree that had rarely been afforded to easterners.Footnote 24 In subsequent years, he could frequently be seen wearing a turban or an Arab-style kefiyyeh and agal, singing in Persian or heavily accented Arabic, Pashto, or Hindi.

At the famed Music Hall Botir Zokirov founded after the 1957 Festival, his younger siblings, including Farrux, learned their first lessons in popular music performance.Footnote 25 It is thus no surprise that much in Yalla’s performance practice harked back to the performance practice his parents and siblings had helped to shape. Like Karim Zokirov, Yalla adapted Uzbek folk melody to western generic norms; like Botir Zokirov, the band tapped into global and Soviet popular music trends, from estrada to Beatlemania. Yalla shows both continuities and discontinuities in Soviet representations of the East.

“Ah, the Frost!”: Domesticating “East” and “West”

In their first decade, Yalla managed a delicate balancing act between its youthful interest in western rock, its roots in Soviet national culture, and mainstream pressure to assimilate with implicit Russian norms. The band members were all amateurs, students at the Tashkent Institute for Theater and Art, listening to both bootleg and official albums and piping in illicit music on the shortwave radio: Simon and Garfunkel, the Beatles.Footnote 26 They had diverse musical training in western classical instruments—the violin, the piano, the guitar—as well as Turco-Persianate instruments like the dutar and rubob (long-necked lutes) and the doira (a handheld drum similar to a tambourine). They aspired to make it big in careers in film, theater, and music, but in the meantime, they played around on an electric guitar and some decrepit amps they found in storage. Their first shows, in 1969, were amateur performances for March 8, International Women’s Day; and May 9, Victory Day. These shows were successful enough to get them a dedicated practice space and the highest-quality instruments and equipment that could be found in Tashkent at the time—in other words, not that much. They did the best with what they had.Footnote 27

Launching beyond their local popularity, Yalla made it big on an all-Soviet stage with a breakout performance in 1971 at the televised music competition show, “Allo, my ishchem talanti” (Calling All Talent!), for which they performed a sentimental song inspired by Russian folk music, “Plyvut tumany belye” (The White Fog Floats), and the “Andijan Polka,” a lively dance number accompanied by the Uzbek doira, a type of tambourine. Apart from the doira, their look was clearly calculated as an answer to the Beatles, with their mop tops and smart black-and-white suits and ties. Their set design, with a neutral white platform for the drum set and the band members positioned in a minimalist arrangement around it recalled John, Paul, George, and Ringo on the Ed Sullivan show. From their success in the competition, they launched into all-Union fame, touring the whole Soviet Union and eastern bloc, playing to packed stadiums from Kazakhstan to East Germany, and sharing a stage with stars like Alla Pugacheva and Vladimir Vysotskii.

The band began as an extension of the exuberant encounter of Soviet youth with western culture. Under the direction of Leningrad-born Evgenii Shiriaev from 1971 to 1976, Yalla capitalized on an emerging effort by the Soviet cultural establishment to co-opt and control the popularity of western rock music. Rather than banning such music altogether, the official establishment sponsored “vocal-instrumental ensembles,” or VIAs (Rus. Vokalˊno-instrumentalˊnye ansambli), which incorporated and domesticated elements of the popular music of the west.Footnote 28 In the union republics, VIAs like Yalla also became a site for negotiating the delicate balance between national belonging and Soviet civic identity. The wildly popular Belarusian VIA Pesniary, with their national embroidered tunics and Slavic folk harmonies, was one of Yalla’s early influences, while bands like the Kazakhstani Dos-Mukasan and Turkmenistani Gunesh shared Yalla’s synthesis of western popular music with Soviet estrada and Central Asian folk traditions.Footnote 29 In Central Asia, however, none were quite as commercially successful as Yalla.

Yalla’s early style emerged primarily from its engagement with British rock music: the Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Deep Purple; the band even covered Uriah Heep’s “Lady in Black” in Uzbek translation, under the innocuous rubric of an “English folk song.”Footnote 30 Even in incorporating the east in their performances, Yalla was arguably imitating the Beatles, who by the 1970s were thoroughly engrossed with Indian music and culture. Yalla’s basic creative practice included Uzbek instruments within the musical structure of a 1960s rock song. In this sense, Yalla is to the 1960s rock band as Üzeyir Hacıbäyov’s Leyli and Majnun is to the European opera: a way of demonstrating the nation’s participation in global modernity by imitating a western form. And yet, just as the opera created spaces for often-unrecognized participation “from below,” for Yalla the rock song offered opportunity not just for imitation, but for innovation.

Consider the basic composition of the band’s early hit, the “Andijon Polka.” Yalla’s arrangement of the song used tight four-part harmonies and a rudimentary chorus-verse structure that could have come straight from the B-side of A Hard Day’s Night. Yet the band members saw themselves as doing something entirely new: a synthesis between Uzbek national performance culture and western popular music. Indeed, by the time Yalla took it up, the melody of “Andijan Polka” was a well-established popular song, based on an instrumental arrangement for the accordion made by an Uzbek musician in the 1930s, and drew on Uzbek classical and folk motifs alongside Russian folk style.Footnote 31 To this basic melodic structure, the band added bilingual lyrics (Uzbek and Russian) and rousing percussion and instrumental interludes that owed much more to the classical and folk music of Central Asia than to the Fab Four.Footnote 32 In a televised New Year’s Eve performance of the song dating to the early 1970s, Farrux Zokirov interrupted the song with an extended percussion solo as another band member took the floor for a dance.Footnote 33 The song thus represented more than a mere transplantation of the Beatles atop Central Asian popular music, but an intentional synthesis of the two. More precisely, the band layered the popular western music of the 1960s onto the Soviet Uzbek mass music of the 1930s, which in turn repurposed popular and classical melodies from the pre-Soviet past. In terms of basic structure and harmony, the song may have been predictably Beatles-esque; but lyrically and melodically, it added a substantive original component. As one 1972 review put it, Yalla’s songs “take on a new, modern sound … without losing at the same time their national color [Rus. kolorit] (this is audible … in the Andijan Polka).”Footnote 34 The song became enormously successful.

In November and December of 1971, riding on their success at “Calling All Talent!,” Yalla undertook a tour of the entire Soviet Union, performing to packed stadiums alongside a roster of established and up-and-coming stars, including a young Alla Pugacheva. As the band’s popularity grew, so did pressure from the conservative cultural establishment to align themselves with all-Soviet mainstream cultural norms, given their clear infatuation with western music. If the VIA might be understood as an effort to wed “youth form” with “socialist content,” some establishment figures feared that those “youth forms”—the songs of the Beatles—could become a Trojan horse for un-socialist content. After one of the band’s early performances, for example, an older Party secretary in Tashkent told the band members they played too much “boogie-woogie” and needed to round out their repertoire with something “soulful, familiar, and patriotic” (Rus. dushevnoe, rodnoe, otechestvennoe), suggesting a waltz as a possible addition to Yalla’s repertoire.Footnote 35

Perhaps the most popular example of the “soulful, familiar, and patriotic” is the band’s early hit, “Oi, moroz, moroz” (Ah, The Frost, The Frost). This well-known song was widely believed to have Russian folk origins, and had spiked in popularity after it appeared in a 1968 film.Footnote 36 The song represents the perspective of a peasant man on the road with his horse in frigid weather, imploring the “frost” (moroz) not to freeze him. In successive verses, the singer describes how he longs to get home to embrace his wife and water his horse. It exudes the by-then well-established mythology of Russians as long-suffering victims of their climate, and the pathos of peasant life long preceding Tolstoy. At the time, most singers did the song with a kind of sentimental jollity, but Yalla’s performance leaned on melodrama with plaintive four-part harmonies that moved audiences. Yalla used rock instrumentation, with electric bass and acoustic guitar, a keyboard, a rock-band drum set, and a very prominent triangle. Still, the arrangement was conservative and vocal-forward, evoking the longer history of Stalin-era “folk” choirs. The members of the band used the song as a kind of legitimizing move for their VIA performance practice, a way to counterbalance the “boogie-woogie.”

The fundamental tension in “Oi, Moroz, Moroz” lies in precisely what Yalla’s advisers meant when they asked for something “familiar and patriotic.” Yalla performing “Oi, Moroz, Moroz” is, from one perspective, the apotheosis of an undifferentiated Soviet identity, blind to national difference—particularly given that the early composition of the band included not only Uzbeks, but also Russians, Jews, Armenians, and Tatars. In the early Soviet days, Central Asians almost exclusively performed Central Asian national belonging, representations of their own “folk” cultures, particularly when performing in the metropole. How far Yalla had come, their critics claimed, now performing in a mixed-ethnicity band as full members of a universal Soviet people, and sharing stages with VIAs from Belarus and Turkmenistan. Wherever they went—from to Dresden to Karaganda—they filled stadiums with adoring fans. To sing a Russian folk song was to demonstrate that Uzbeks had fully merged with the Soviet people.Footnote 37 Even musical form showed that by mastering vocal harmony, the band had finally “superseded” the homophonic musical forms typical of pre-Soviet Central Asian music and therefore coded as “backward.”Footnote 38 As one critic put it in 1980, “Through the performance of Russian songs … the homophonic singing tradition [of Uzbekistan] was tactically overcome.”Footnote 39

At the same time, the fact that Russian folk music constituted a necessary part of Yalla’s program showed that the band could legitimize itself only by performing Russianness better than the Russians themselves. Indeed, the astonishment that Yalla met when performing “Ah, the Frost, the Frost” outside Central Asia indicated that audiences saw them as representatives of a marked category, not an undifferentiated Soviet people. When Yalla performed the song in “Calling All Talents!,” for example, the noted Soviet composer and songwriter Ian Frenkelˊ admonished Yalla’s competitors to “learn to perform Russian songs from the Uzbek performers!”Footnote 40 Frenkelˊ, a Jew himself by ethnicity, was commending the Central Asians, not exactly for assimilating, but for performing their Sovietness by so fully inhabiting the perspective of their far-off frost-dwelling Russian compatriots. “Oi, Moroz, Moroz” thus helped Yalla earn the trust of audiences who were skeptical of the Beatles on the one hand and uninterested in “national” music on the other. It helped Yalla reach mainstream audiences that the band sang predominantly in Russian, especially when performing outside of Uzbekistan.

Yalla’s warm reception of Frenkel’’s remarks exemplifies how the band delighted in upsetting the expectations that followed them as Central Asians. In Moscow, “Oi, Moroz, Moroz” overturned metropolitan audiences’ expectations of Central Asian performance culture. Elsewhere, the band undermined conceptions of Soviet music as exclusively Slavic or Russian. For example, Farrux Zokirov describes Yalla’s runaway popularity in the GDR during the 1970s in implicitly racial terms. According to Zokirov, Germans identified Soviet culture with stodgy “Kalinka-malinka” style—a reference to the stereotypical Russian folk song, usually accompanied by a plunking balalaika. When Yalla arrived in East Germany, Germans were shocked to see these “swarthy guys [Rus. smuglye rebiata], not at all looking like ‘Kalinka-malinka,’ singing songs of their own.”Footnote 41 In Farrux’s view, Yalla’s stark difference from the presumed Slavic Soviet norm became a driver of their popularity in East Germany.

When asked about their experience as Central Asians, the band members I have spoken with generally reject the language of race and racism. Rustam Ilyasov, for example, remembered only one time he overheard an audience member say that the band was “not bad for Central Asians,” using a common racial slur for people from the Caucasus and Central Asia.Footnote 42 From another perspective, however, Yalla’s experience suggests that a certain primordial racialization dogged them all the same. When touring beyond Central Asia, regardless of their self-presentation, they remained inescapably, physiognomically, constitutionally Central Asian, even, or perhaps especially if their difference was taken as a (backhanded) compliment.

“Three Wells”: Soviet Oriental ‘Modernity’

In its early years, with its Russian-born director, Yalla built its reputation by Sovietizing the popular music of the west and amalgamating it with national performance traditions—primarily, with Uzbek national instruments and repertoires. They gained their first following by integrating Uzbek national music with both Russian and western norms. But in the late 1970s, Yalla reached a turning point. The band’s synthesis of the Beatles with Soviet national pageantry had proven massively successful in the early 1970s, but beginning in 1979, Yalla reinvented itself by leaning into a theatricalized East as its performative brand.

The reinvention began in large part as a response to a bigger crisis in Soviet popular music. As VIAs proliferated and western culture penetrated Soviet space, both audiences and critics became more exacting in their demands. Professional musicians had always complained of VIAs’ supposed amateurism and poor musicianship, and old-guard cultural figures saw them as a pathetic departure from the lofty heights of earlier Soviet music.Footnote 43 VIAs were tolerated in official culture primarily because they presented a popular alternative to western culture. But over time, their popularity declined even among mass audiences. By the early 1980s, it had become commonplace that VIAs were dull and derivative; some critics even began speaking of a “crisis” in the VIA genre.Footnote 44 VIAs came under pressure to develop new performance practices—ones that were suited not only to in-person stage performance, but to televised spectacle, as by 1980, television had thoroughly penetrated Soviet society.Footnote 45

During the “crisis of the VIA” Yalla did better than some bands, but it too experienced its fair share of disappointments. After 1974, a series of flops before audiences in the GDR, the Czech Republic, and Moscow raised concerns that they were falling behind Eastern Europe’s bands, such as the popular East German rock group Puhdys, who had a more modern sound and more advanced technological apparatus.Footnote 46 Meanwhile, the members of Yalla had their own commitments: some were called away for military service, while others turned to other creative pursuits.Footnote 47 Lacking much professional music training, the group cycled through members as the band’s repertoire stagnated. One by one, all the band’s original members left, leaving Zokirov the last man standing.

Despite the “crisis,” Zokirov was determined not to let the band fade into oblivion. Aided by his brother Botir, Farrux, now artistic director of the band, went to work assembling a group of professionals who would revitalize Yalla’s work and cement its status at the top of the Soviet popular music scene. In 1979, Farrux Zokirov attended an estrada festival in Yalta, where he met Rustam Ilyasov, an established jazz musician then working as a professional arranger in a large radio orchestra, who also had nineteen years of professional training in classical violin performance under his belt.Footnote 48 Zokirov approached Ilyasov with an invitation to join the band as musical director, but Ilyasov demurred: his interests lay primarily in jazz, and he thought of Yalla as he thought of most VIAs: frivolous and unprofessional.Footnote 49 Ilyasov agreed to join the band only after the Zokirov brothers aggressively wooed him, promising full creative control over the band’s music.

Ilyasov took it upon himself to elevate Yalla’s musical professionalism. He claims, in fact, that Yalla had never used musical notation; some of the early band members purportedly did not know how to read music. Ilyasov introduced written music and brought his extensive experience to bear in building a new repertoire and organizing a new cohort of musicians.Footnote 50 By 1981, Yalla had coalesced around a group of six: beyond lead vocalist Farrux and guitarist Rustam, they were joined by Javlon To’xtaev, Abbos Aliev, Boris Gershkovich, and Alisher Toˊlyaganov.Footnote 51 By 1986, critics were again hailing Yalla as an example of a successful VIA act at a moment when most VIAs were fizzling out.Footnote 52

But Yalla’s makeover went far beyond its music. In the 1970s, Yalla had used very simple costumes and props. Now, Zokirov sought no less than a complete makeover of Yalla’s performances: he wanted to turn Yalla into a multimedia spectacle—what he described as a “theatricalized performance” (teatralizovannoe predstavlenie). Incarnating this ambition required much more than just Ilyasov’s musical expertise. To develop the “theatricalized performance,” Botir Zokirov worked his Moscow connections, introducing Farrux to his contacts in show business. The Zokirov brothers engaged Mark Rozovskii, a renowned theater director and dramaturg then best known for producing the first Soviet rock opera, Orpheus and Eurydice (1974).Footnote 53 Tashkent-based choreographer Boris Zavˊialov helped the band develop their movements on the stage.Footnote 54 Botir Zokirov invited his friend, renowned poet and lyricist Iurii Entin, to visit Tashkent; Entin ended up writing several of Yalla’s most popular songs of the 1980s. Working together, the team of musicians and theater professionals created Yalla’s first concert program of the 1980s, “Let’s Celebrate!” (Uzb. Yallama yorim/ Rus. Davaite veselimsia).

Perhaps no one exerted a greater influence on Yalla’s performative Easternness, however, than Alla Kozhenkova, the woman who designed their costumes and sets. Kozhenkova first traveled to Uzbekistan essentially on a lark, joining Entin in Tashkent alongside a group of her Moscow friends. Kozhenkova, already well established in Moscow, had plenty of work at home and had no intention to look for more in Tashkent.Footnote 55 In an interview, she recalled attending a Harvest Festival where Yalla was playing in the Ferghana Valley city of Andijan.Footnote 56 Kozhenkova described the scene as a quaint country event: a few women chopped vegetables in shacks while Yalla played in the middle of a verdant field. Kozhenkova was impressed. All they wore was plain black-and-white suits, but those “boys [sic] in the meadow” sang so well that she could not help but be charmed.

Farrux Zokirov seized the opportunity to invite Kozhenkova to design the band’s sets and costumes for the new program. Like Ilyasov, Kozhenkova demurred at first. She had a young child at home; she could not stay in Uzbekistan any longer than the few days she had already planned to be there. But when Kozhenkova arrived at the airport to fly home to Moscow, she found a large crate of fresh Uzbek produce, a gift for her family from Zokirov. Such produce was almost impossible to obtain in Moscow, and for Kozhenkova, it was more precious than cash. This unexpected gift sealed the deal: she agreed to design the band’s sets and costumes, and would continue to do so until the end of the 1980s. Yalla’s barter, or rather, their gift economy, was just one of many material contingencies that shaped Yalla’s performance practice behind the scenes. In using Uzbek fruit to woo Kozhenkova for his performance agenda, Zokirov inverted the conventional hierarchy of socialist production: yes, Uzbekistani agricultural products flowed upward to the metropole, but only in strategic service of Zokirov’s home-grown creative project.

For Kozhenkova, Yalla’s appeal lay not in its VIA appropriation of western rock music—those bands were a dime a dozen—nor in its Uzbek national distinctiveness. What appealed to her, the potential she saw in Yalla, lay in its performance of a more exotic and less geopolitical East. Kozhenkova was almost entirely unfamiliar with Central Asia; the short trip with Entin was the first time she had ever visited Uzbekistan. To fill the gap in her knowledge, Kozhenkova consulted the research collections available at the Moscow theater where she worked. She learned everything she could about Uzbek national costume; she also consulted resources on Persian dress and ornament. After completing her sketches for the costumes, she returned to Uzbekistan to complete her work. There, the members of Yalla continued to wine and dine her. One day during her sojourn in Tashkent, Kozhenkova narrates, Farrux cooked an Uzbek meal for her in the lush courtyard (hovli) of a traditional Uzbek home. Kozhenkova was the only woman present, but the band members treated her with utmost respect; she was particularly impressed that, like good Muslims, they seemed not to be drinking.Footnote 57 She felt she was in an “Oriental fairytale,” a vostochnaia skazka.

Kozhenkova designed her sets and costumes to convey that fairytale East. Before, Yalla had usually performed in suits and ties, occasionally adding tame expressions of national color. Despite the limited materials available to her, Kozhenkova dramatically emboldened the band’s wardrobe, replacing the staid blazers of the band’s first decade with billowing silks, floor-length robes, gold and silver trim, and large embroidered medallions. Yalla’s previously austere stage design now incorporated rich decorations: one memorable set design incorporated tented domes for each band member. Another notable backdrop recalled a Persian miniature Kozhenkova had found in her research collection, complete with an architectural arc, painted birds, and inscriptions in Arabic script. The new sets and costumes surely impressed live audiences, but they were also distinctively television-friendly, with their bright, bold ornamentation and flashy colorways.

For Kozhenkova, this East was both material—swathed in bedazzled silks, adorned with ornament—and embodied, both in racial and gender terms. In her eyes, Yalla’s members were charming and talented, but also physically attractive, and she emphasized that attractiveness. When designing publicity for a performance at a theater in Moscow, Kozhenkova emblazoned the faces of the band members on a massive banner, measuring, in her estimation, twenty to thirty meters in length. She believed there was no better marketing for the band than its faces, the faces of these “wonderful, beautiful, Eastern people”—the type of people, she said, you could never find in Moscow. Their faces spoke for themselves; the costumes and sets were just window-dressing.

If relying solely on Kozhenkova’s account, Yalla fits neatly within the framework of Orientalism in Edward Said’s canonical definitions. From Kozhenkova’s perspective, Yalla and its members were charming and talented performers, but they were racialized as easterners, ensconced in a timeless “Oriental fairytale.” Kozhenkova’s Orient was ahistorical: medieval Persian ornament was just as relevant to Yalla as contemporary Uzbek costume. Her work perpetuated the long tradition of using “ornament” as a marker of national architecture and, more broadly, of visual culture, while referring to western classical traditions for its basic structures.Footnote 58 The fine distinctions and connections among Transoxanian culture and the cultures of Iran and the rest of the Middle East were of little significance to Kozhenkova. In her mind, contemporary Central Asia merged seamlessly with the Orient she had encountered growing up in Russia, and the band members’ racialized physiognomies evoked a range of associations with that imagined Orient. At the same time, at the impulse of Zokirov Kozhenkova brought the sensibilities of a cutting-edge metropolitan costume designer to the eastern material.

At the same time, Kozhenkova’s designs cannot be reduced entirely to Orientalism. While she saw Yalla as exotically Oriental, for her—and for the members of the band—the Oriental designs only amplified their masculine attractiveness, rather than feminizing them as classical Orientalist representations. Possibly, she and Zokirov saw an opportunity to tap into the glam masculinities of global pop culture. While Kozhenkova did not explicitly refer to western rockers as an inspiration, to audiences in the 1980s her costumes undoubtedly evoked the flashy designs, bright color palettes, and striking silhouettes of western rock stars like Mick Jagger. Kozhenkova’s vision adopted the Orient and made it identifiably contemporary.

While Zokirov took advantage of Kozhenkova’s sensuous Oriental vision, he also tapped into the other meanings of the East in developing the new repertoire. Two main cycles of songs structured the new concert program. The first song cycle comprised a series on the cities of Uzbekistan, including its famous cities.Footnote 59 But no song is more representative of Yalla—and the contradictions in its representation of the East—than “Uchquduq,” which reached the finals for Song of the Year in 1981–82; it soon became the title track for Yalla’s first full-length LP, Three Wells, and remains one of the most widely known Central Asian pop songs throughout Eurasia today.

The origins of “Uchquduq” can be traced to the trip that first brought Kozhenkova to Tashkent. At the beginning of their reinvention, Yalla was touring Uzbekistan, and on a sunny spring day sometime in 1980, Yalla’s tour bus departed for Uchquduq with poet Iurii Entin in tow. Founded in the 1950s after uranium was discovered in the region, Uchquduq’s name, literally meaning “Three Wells,” had an ironic ring given that the city was built in the middle of the arid Qizilqum desert. Since the city was closely linked to the Soviet nuclear industry, it did not appear on most published maps, and was largely unknown even in Uzbekistan. As the bus reached the top of a hill, the “panorama of a city in the steppe” opened out beyond the windows of the tour bus.Footnote 60 After his long, hot ride through the desert, Entin was inspired. He immediately scribbled down the lines that would become the Russian lyrics for “Uchquduq”:

Hot sun, hot sand

Hot lips—ah, for a sip of water!

In the hot desert, not a single path can be seen:

Tell me, caravan driver: when will there be water?Footnote 61

Entin was so enthusiastic about the song that he insisted Zokirov compose a melody immediately and perform it at their show that very night. Accompanied by rudimentary solo guitar, nervous about how the barely-finished song would be received, the band played the song for their Uchquduq audience, which was composed largely of miners and technical staff.Footnote 62 Despite the band’s apprehension, the audience gave the song an ecstatic reception. Fans with tears in their eyes ran onto the stage to thank the band members: a hit was born.Footnote 63

“Uchquduq” seamlessly brought together the exotic Orient with the longstanding tropes of Soviet national modernity. Like the opening lyrics, the visuals in the song’s 1984 music video emphasized exoticism: garbed in the bright-colored billowing silks of Kozhenkova’s design, the members of the band ride camels through a desert windstorm, guided by a wizened grandfather.Footnote 64 From the first verse’s cry of thirst, the song climaxes with a lyric about the modern Soviet city:

Any old man in Uchquduq can tell

How a beautiful city appeared in the desert

How houses shot up into the blue sky,

And how nature herself was amazed.Footnote 65

In its representation of the state’s victory over nature, the song evokes Stalinist resonances: the verse reads like an intertitle from the famous 1929 film about Central Asian irrigation, Turksib. It also echoed the rhetoric surrounding the massive irrigation projects of the late Soviet period.Footnote 66 Arguably, the song “Uchquduq” fed Moscow’s Orientalist culture industry, much as the rare earth elements of Uchquduq fed Moscow’s military industrial complex.

For Farrux, however, Uchquduq represented something else: an opportunity to bring the name of a little-known town in Uzbekistan to the lips of the entire Soviet people. Indeed, in their 1980s repertoire Yalla singularly focused on elevating Turco-Persianate cultural products to an all-Soviet stage. Perhaps the best example of this is the second song cycle of the early 1980s, which centered the verses of eastern poets, both classical and modern. The idea came to Farrux Zokirov after he covered a popular song from a Soviet film melodrama, “The Last Poem,” based on a rough “translation” from Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. While the film version of the song was performed by a Russian singer, the more popular rendition was Yalla’s, which beat the original to reach the finals of the televised Song of the Year competition in 1980–81. Unlike the original version, Yalla’s added a distinctive eastern flavor, adding a prelude on the sitar and featuring an Arab ‘oud on stage. So popular was this rendition that Zokirov was inspired to compile a full cycle of songs from poets of the East, including classical Persianate poets Rudaki, Omar Khayyam, Makhdum Qoli, Amir Khosrow, and Ali Shir Nawa’i, alongside the “Persian motifs” of Sergei Esenin.Footnote 67 Beyond their canonical status in Turco-Persianate letters, however, the poets also aligned with the socialist Eastern International: Makhdum Qoli and Ali Shir Nawa’i were recognized national poets of the Soviet Republics of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, respectively; Amir Khosrow harkened from Delhi. A song by Soviet-aligned Turkish modernist poet Nazım Hikmet rounded out the cycle. Yalla’s performance of the Eastern International became part of Soviet cultural diplomacy abroad in this period as the band performed in strategically important regions of the Global South.

For Farrux Zokirov and the band, the cycle of eastern poetry emerged both from audience demands and from Yalla’s personal commitment to the cultural heritage of the East. But while Zokirov may have taken advantage of Kozhenkova’s Oriental vision, he brought his own agenda to bear. The new program, he hoped, would demonstrate the “high level of Eastern and, naturally, Uzbek poetry.”Footnote 68 In this respect, Yalla took the metropole’s demands for Oriental exoticism and turned them toward a very personal artistic project, one that strategically harked back to Karim Zokirov’s performances in the 1930s and even what he understood as the performances of his ancestors in Turkestan. If the VIA was under attack as a vapid low-cultural form, Yalla used the traditions of the Turco-Persianate East to elevate Uzbekistan and the Eastern International, not as a retrograde backwater, but as a hub of “high” culture and a paragon of modernity.

“The Musical Teahouse” and the Oriental Market

By 1985, Yalla had compiled a repertoire and performance practice that seamlessly melded the multiple valences of the Soviet East. It tickled the fancies of metropolitan interest in Oriental exoticism, and it remediated a longstanding vision of the global Eastern International by turning to Turco-Persianate cultural legacies. But as perestroika came into full swing, Yalla’s East performance responded to another set of pressures: those of an emerging market. As perestroika reforms took hold, the ideological narratives around Soviet modernity and Eastern Internationalism fell away in favor of an increasingly deterritorialized, highly stylized performance of the East.

As Zbigniew Wojnowski has argued, pop music industry professionals were early advocates for economic reforms in the Soviet Union.Footnote 69 By the early 1980s, a status quo had developed in which top pop artists bankrolled less profitable folk ensembles and classical orchestras. Rustam Ilyasov reported that in the early 1980s, Yalla would undertake grueling tours for a mere pittance. For example, during an ordinary visit to Karaganda, Kazakhstan, the band played two shows per day in the city’s hockey stadium over the course of ten days, serving as many as 100,000 viewers total. For this immensely profitable work, each band member would earn a mere ten rubles per show.Footnote 70 To purchase expensive synthesizers, update their sets and costumes, or pay tour expenses, the band was forced to comply with meager budgets handed down from above. After 1986, the introduction of khozraschet, or “enterprise accounting,” allowed Soviet artists to begin managing their own finances within some limitations.Footnote 71 Beginning in May 1988, Yalla became “the first group of its type in the country” to switch to khozraschet.Footnote 72 Instead of tens of rubles, the band members suddenly made thousands per show.

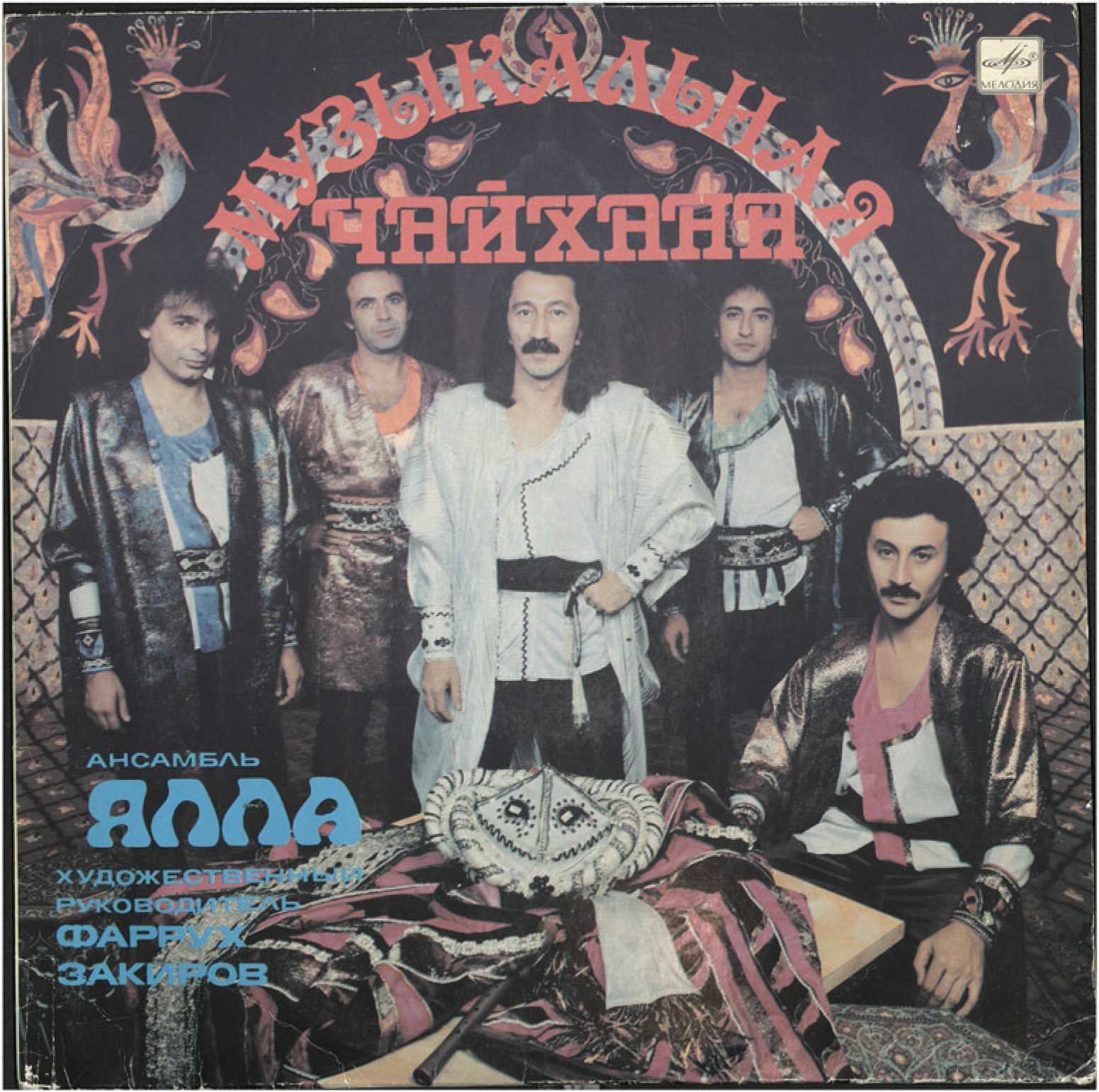

Figure 1. Album cover for “The Musical Teahouse” (Muzykalˊnaia chaikhana, 1988), displaying Kozhenkova’s costume and set designs.

In the context of perestroika reforms, Yalla debuted a new concert program in Kyiv in 1987, “The Teahouse for All Time” (Rus. Chaikhana na vse vremena), followed by an album under the same name (Figure 1). Like “Let’s Celebrate!,” “The Teahouse for All Time” dramatized the Eastern International, including songs with lyrics by Persianate poets Nizami Ganjavi and Omar Khayyam. For Zokirov and his fellow band members, the “Musical Teahouse” program provided an opportunity to properly showcase both the poetry and popular performance traditions of Transoxiana. The program comprised three main parts, in which the band members not only sang and played, but also acted in small dramatic skits. At the beginning of the show, Farrux Zokirov invited audience members to join him at the teahouse: “Today, Yalla invites all to our musical teahouse for a festival, where there will be competitions of singers and poets, jokers and jesters (maskharabozov i ostroslovov)!” Soon, the lights drop and a video backdrop glows as the audience joins the band on a fairytale journey through the East. “Stars light up. An ancient fairytale eastern city with towers and minarets appears. Toward the city moves a camel caravan.”Footnote 73 The show’s second portion was billed as a mushaira, a poetry symposium, using some of the songs from the old poetry cycle and premiering some new ones. Tagore, Shakespeare, and Esenin all made appearances. In the third and final section of the program, the band elevated features of popular entertainment in Central Asia: songs focused on tightrope walkers (in Russian, the song “Kanatokhodtsy”) and jesters (Uzb. masxaraboz).

In many ways, the new program echoed the band’s work in the early 1980s. Still, compared to the performative East of those years, the new show dramatically heightened the spectacular, often at the expense of “socialist content.” For audiences around the Soviet Union, the multimedia spectacle the band produced was unlike anything they had ever seen. For the new program, Kozhenkova designed an entirely new set of costumes, using the same flowing silhouettes of the costumes in the “Uchquduq” video, but bejeweling them with “twenty or thirty kilograms” of Swarovski crystals, to which she had access through her work in the Moscow theater world.Footnote 74 Gilded embroidery adorned the parts of the robes (Rus./ Uzb. chapans) that were not bedecked with crystals. Zokirov claims that Kozhenkova’s spectacular costumes triggered a “chapanization of the entire country”: before long, massive pop stars like Filipp Kirkorov and Valerii Leontˊev began wearing sparkly eastern robes. If for Zokirov the robes represented an attractive eastern masculinity, for stars like Leontˊev and Kirkorov they became part of an emergent camp aesthetic.Footnote 75 Such costumes became a mainstay of the Uzbekistani estrada industry even post-independence.Footnote 76

So flashy were the new costumes that some band members reportedly worried they might distract from the music, with its self-conscious references to Uzbek folkloric tradition.Footnote 77 At Song of the Year 1988, where Yalla performed the song “Musical Teahouse” in Kozhenkova’s costumes, the glittering of the Swarovski crystals was matched only by the sparkling of tinsel and disco balls on the bedazzled stage.Footnote 78 That performance amplified all the Oriental trappings of previous performances. It begins with an unmistakably eastern sound, even before the band members enter the stage. As the musicians appear, we learn the source of the sound: an ‘oud, which a band member strums unconvincingly as he strides down the stairs onto the main stage.Footnote 79

Published reviews of the new program almost universally commented on its spectacular nature. One reviewer cited its “captivating melodies, luxurious arrangements, gorgeous decoration, and magnificent costumes,” continuing, “a sense of harmony … inhabits every gesture, the performers’ manner of behavior on stage.”Footnote 80 A Pravda reviewer effused, “How colorful (koloritny) are their theatricalized concert programs! Anyone who has seen, say, ‘The Teahouse for All Time,’ will no doubt remember that unique spectacle (samobytnoe zrelishche) for a long time to come.”Footnote 81 In the early 1980s, “Let’s Celebrate!” had played up the spectacle of Oriental form while retaining some semblance of Soviet content; “The Teahouse for All Time” dispensed with content altogether. The Swarovski crystals, at the same time, expressed a turn toward a decidedly un-Soviet mode of conspicuous consumption.

In the context of perestroika, is Yalla’s East apolitical and frivolous or is it subversive? On the one hand, in the context of Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms, we might read Yalla’s performance of the East as a capitulation to the emerging Soviet market’s demands for an exoticized Orient. On the other, we might see the very same performances as a way for Yalla to reconfigure the very racialized Orientalist tropes that bedeviled Central Asians and Caucasians in the late Soviet years, and that had defined Yalla’s early performance practice. In performing these tropes, and with such glam excess, perhaps Yalla made a space for Central Asians in the Soviet mainstream by simultaneously identifying with and expanding the boundaries of mainstream categories. Regardless of how we interpret it, the tension in Yalla’s perestroika-era performance of the East echoes the broader tensions in Soviet society on the eve of collapse: between the market and the state; between official and unofficial culture; between national difference and Soviet belonging; between ideological commitment and performative discourse.Footnote 82 When the Soviet Union ceased to exist, the fate of Yalla’s “Orient” was profoundly unpredictable.

Conclusion: Yalla’s “Delicate” Performance of the East

When discussing his late Soviet work, Farrux Zokirov repeatedly cited the adage from the popular Soviet comedy White Sun of the Desert (1970): “The East is a delicate matter.” In the film, the quote lends itself to precisely the popular conceptions of Central Asia as backward, wild, and unmodern, underpinning decades of (post-)Soviet cultural imperialism. For Farrux Zokirov, to the contrary, the quote amplified his vision of eastern cultural sophistication. This article has demonstrated the profound ambiguity in Yalla’s performance of the East, stemming from the many pressures shaping their performance practice. Yalla’s East began as a dialogue with western culture in the Soviet Union, becoming a way both to reify and to revise Soviet pop Orientalism. Responding to the material contingencies of late Soviet music industry, Yalla’s East became increasingly market-driven over the course of the 1980s. Yalla’s changing East can thus be read in contradictory ways: as a cunning strategy to bring Turco-Persianate cultural traditions into the racialized Soviet mainstream; a tool for internationalist propaganda; an expression of Moscow Orientalist sensibilities; and, finally, as part of Yalla’s effort to maintain its edge as the market, or something like it, reshaped Soviet culture. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Yalla only gained in relevance, as Farrux Zokirov became a Minister of Culture under Uzbekistan’s first post-Soviet president, Islam Karimov. Most of Yalla’s members continued to perform in Uzbekistan, frequently appearing as part of the mass spectacles of Uzbek national identity that characterized Karimov’s reign.Footnote 83 Under these conditions, as global-popular culture became increasingly available to everyone with a television, the familiar category of the East changed almost beyond recognition. But that is a story for another day.

Claire Roosien is an assistant professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University. She holds a PhD in History and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago. She has published on a range of topics in Central Asian cultural and social history, and is currently completing her first book, provisionally entitled The Making of Soviet Culture in Uzbekistan: Socialism Mediated.