Introduction

For a long time it has been noted that the Berber suffix conjugation, used for the PNG marking of qualitative verbs, bears a striking resemblance to the Semitic suffix conjugation, which in East Semitic is used for the conjugation of, mostly, predicative adjectives, and for the general perfect in West Semitic. While the morphological similarities have been observed, a reconstruction of what this construction would have looked like and the morphology of the words to which the suffix conjugation can be attached has not yet received in-depth attention. This article examines the development of what I propose to be a predicative adjective formation in the shared ancestor of Proto-Berber and Proto-Semitic, which I will call Proto-Berbero-Semitic.Footnote 1 Moreover, I will examine the morphological formation of adjectival stems in both branches, and show that they have a similar structure that is reconstructible for Proto-Berbero-Semitic.

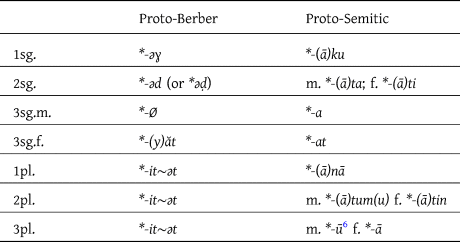

Semitic makes ample use of deverbal adjectives that convey properties onto the nouns they modify, e.g. Ar. ǧamalun mayyitun “a dead camel”. This is quite different from Berber which does not have any formal participial formations,Footnote 2 and expresses many properties that would be expressed adjectivally in Semitic with verbal relative clauses, especially with the verb in the perfective, which may express stative situations (either generally stative, or resultative) (Kossmann Reference Kossmann, Frajzyngier and Shay2012: 79). For example, the Awjili sentence nəhínət ufánət alúɣəm yəmmút=a “they found a dead camel” (Van Putten Reference Van Putten2014: 157) uses a finite verb yəmmút=a (die:PERF:3sm=RES) in an asyndetic relative clause to modify alúɣəm “camel”, something that would most naturally be expressed adjectivally in Semitic languages. Some examples of other Berber languages are, for example,

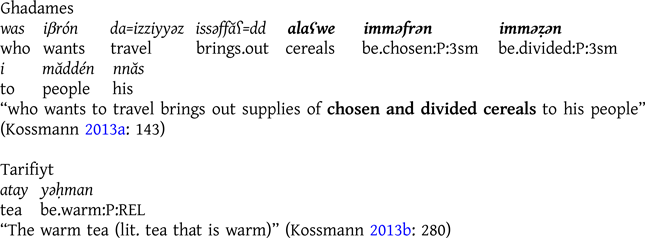

The majority of the verbs in the Berber languages receive a set of affixes very reminiscent of the affixes found in the prefix conjugation of Semitic (Kossmann Reference Kossmann2001b: 72; Prasse Reference Prasse1973: 16). These undoubtedly look similar due to their shared ancestry, as already proposed many times before (see Table 1).Footnote 3

Table 1. The prefix conjugation in Berber and Semitic

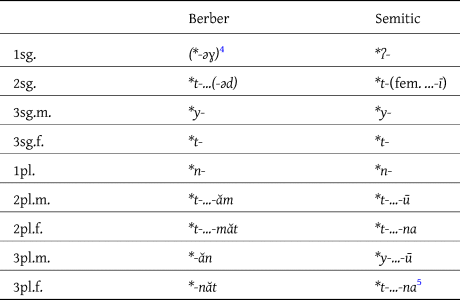

In several Berber languages, however, there is a small group of qualitative stative verbs which have a different set of suffixal PNG markers in the perfective stem of the verb, while the other stems have the regular prefix conjugation. This set will be called the Berber suffix conjugation, e.g. Ghadames (Kossmann Reference Kossmann2013a: 92) and Kabyle (Naït-Zerrad Reference Naït-Zerrad1994: 226) and examples are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The perfective suffix conjugation in some Berber languages

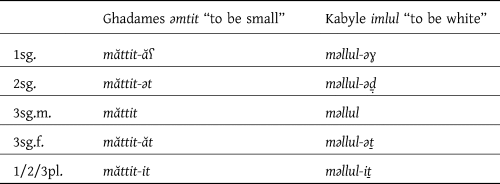

An in-depth discussion of the reconstruction of this suffix conjugation has been undertaken by Kossmann (Reference Kossmann, Chaker, Mettouchi and Philippson2009). He argues that this system, along with 1sg. and 2sg. marking, is probably reconstructible for Proto-Berber, even though some languages (specifically Ghomara Berber and Nefusa Berber) do have this suffix conjugation and do not mark for the 1sg. and 2sg.

Several languages point to a 3sg.f. suffix -yăt rather than -ăt. While I agree with Kossmann (Reference Kossmann, Chaker, Mettouchi and Philippson2009) that this may be old, I do not think his reconstruction *-yăt for sg.f. and *-ăt for the plural is justified. Kossmann assumes that the *-it ending found in the plural is etymologically identical to the *-yăt ending, but several dialects that have the plural -it, e.g. Ghadames, would not have that as the regular outcome of *-yăt. It seems to me therefore better to reconstruct a system which perhaps had variation in the 3sg.f. and pl., rather than a system where the two were conflated. What exactly the origin is of the variation of these two allomorphs is currently unclear. A possible reconstruction of the suffix conjugation is given in Table 3.

Table 3. The Proto-Berber and Proto-Semitic suffix conjugations

The morphological similarities between the predicative adjective endings of Semitic and those of stative verbs in Berber have long been recognized (e.g. Rössler Reference Rössler1950: 481; Cohen Reference Cohen1984: 111). I consider this comparison to be compelling and therefore follow previous researchers who consider these two suffix conjugations to have a single common ancestral system. However, the exact development and relation of Berber stems that take this suffix conjugation to the Semitic adjectives and the stem formations associated with them have not yet been fully mapped out. In this article I will map out this development, by examining and comparing the stem formation in Proto-Berber and Proto-Semitic, and will propose a development from Berbero-Semitic adjectival stems that yields the systems of qualitative verbs/adjectives as we find them in the two language families.

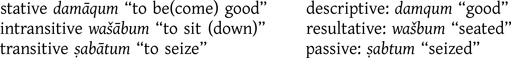

This article deals with several essential distinctions in nominal and verbal semantics. To aid the discussion, several terms need to be discussed. When speaking of verbs we may distinguish between stative and dynamic verbs. Stative verbs describe a state of being, while dynamic verbs (also called fientive verbs) describe a process. Semantically both can be intransitive and transitive, although stative verbs are usually intransitive. Huehnergard (Reference Huehnergard1987: 225), using Akkadian examples, uses the terms stative (= stative, intransitive), intransitive (= dynamic, intransitive) and transitive (= dynamic, transitive) and supplies terms for the resulting adjectival meanings relating to these verbs:

For the purposes of this article, these distinctions are essential, but the terminology will be modified somewhat. As Kouwenberg (Reference Kouwenberg2010: 54ff.) points out, thinking of Semitic verbs (and this is true for Berber verbs too) as inherently dynamic and stative is not very productive because the contrast is grammaticalized, and any verb can express both dynamic or static situations. In Akkadian, this is done by the prefix conjugation (dynamic events) and the verbal adjective (stative events). For Berber, dynamic events are expressed by the aorist and imperfective stems (with different aspectual nuances) whereas the stative is expressed by the perfective stem of the verb. Dynamic events in the past may also be expressed by the perfective in most varieties of Berber. There are, however, some varieties of Berber that distinguish a resultative (stative) from the perfective (dynamic), e.g. Tuareg (Kossmann Reference Kossmann2011: 144) and Awjila Berber (Van Putten Reference Van Putten2014: 151f.).

Kouwenberg observes, following Aro (Reference Aro1964: 7–10), that stative and dynamic are on two poles of a spectrum, where some verbs are more stative and others are more dynamic. It often comes down to interpretation whether a verb is to be considered primarily “stative” or primarily “dynamic”. Wašābum could be seen as meaning the stative “to sit”, in which case wašbum would describe the state “sitting”, or as the dynamic “to sit down”, in which case the verbal adjective would rather have a resultative meaning “seated”.

Kouwenberg (Reference Kouwenberg2010: 58f.) distinguishes a group of verbs – which basically coincide with Huehnergard's stative verbs – which he calls “adjectival verbs”. Adjectival verbs are typically not stative in the prefix conjugation, as their verbal paradigm denotes a process (usually ingressive) while it is the adjective itself that expresses the “stative”. Kouwenberg gives several criteria that allow one to distinguish adjectival verbs from prototypical fientive verbs. For example, adjectival verbs do not have a present participle, and their verbal adjective has a lexically determined vowel in the second syllable as this is the primary form from which the rest of the verbal paradigm is derived. A final useful criterion is a semantic one. Kouwenberg (Reference Kouwenberg2010: 59) states that “a verb is more positively adjectival as the corresponding adjective denotes a more stable, inherent or permanent property”.

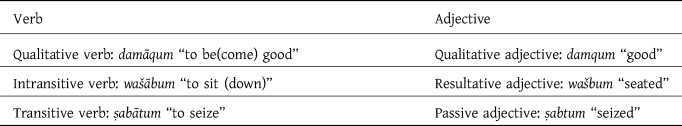

With these points in mind it is clear that the terminology needs to be adjusted slightly, although Huehnergard's triadic distinction is ultimately useful for the current discussion as the semantic distinction between qualitative (Huehnergard's stative) and intransitive verbs and their relative adjectives mark a morphological difference in Berber. Kouwenberg's adjectival verbs will be called “qualitative verbs”, and their corresponding adjectives “qualitative adjectives”. Intransitive verbs, which may be more dynamic or stative, will continue to be called intransitive verbs, but the corresponding adjective will be called the “resultative adjective”, while recognizing that in reality the state expressed by this adjective may be purely stative rather than resultative in nature. Finally, the transitive verbs, which are very often dynamic in nature, will continue to be called that, and I will also continue to call the corresponding adjective the passive adjective, which expresses the resulting state of being the object rather than the subject of the transitive verb. Table 4 summarizes the terminology used here.

Table 4. Terminology of verbs and adjectives

Berber qualitative verbs and the qualitative adjective

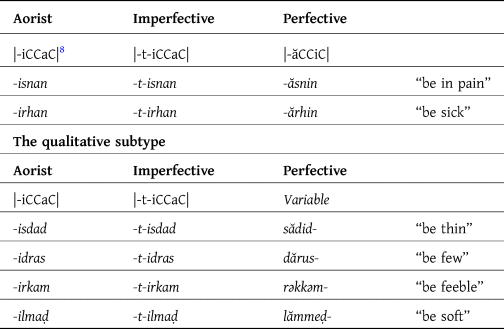

Most varieties of Berber distinguish a class of qualitative verbs. When the variety has a suffix conjugation, it is only the perfective stem (and not the aorist and imperfective stems) that takes the suffix conjugation. Different from other verbal types, these perfective stems cannot be predictably derived from their aorist form. I will call this unpredictable perfective stem the “qualitative perfective” here. In varieties where such qualitative verbs occur, these qualitative verbs generally form a subset of a verb type with mostly intransitive verbs which in Tuareg, Kabyle and Tashlhiyt are recognized by a stem-initial vowel *i or *u in the aorist and imperfective stems.Footnote 7 This larger set of stative verbs does have a predictable perfective stem and this perfective stem takes the prefix conjugation. This system is demonstrated for Tuareg in Table 5. A dash before the stem indicates that the stem takes the prefix conjugation, while a dash behind it indicates that it takes the suffix conjugation.

Table 5. Intransitive and qualitative verbs in Tuareg

Not all languages that have the qualitative perfective have also retained the suffix conjugation. Tashlhiyt and Central Moroccan Berber, for example, use the unpredictable stems of the qualitative perfective, but simply supply it with the prefix conjugation; nevertheless such forms clearly retain their unpredictable perfective formation compared to the aorist across these dialects.

Due to the loss of short vowels in open syllables and the neutralization between *ă and *ə, the perfective stative verb stem*-ăCCiC and *CăCiC- merge to CCiC in a large number of dialects. In dialects that do not retain the suffix conjugation the distinction is thus lost completely, but in those that retain it, the suffix conjugation still marks the distinction. The follow section provides an overview of the different relevant dialects that retain such qualitative verb formations. The dash before or after the stem marks whether it takes the regular (prefix) conjugation or the suffix conjugation.

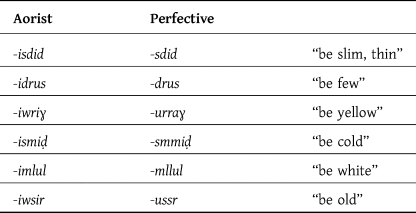

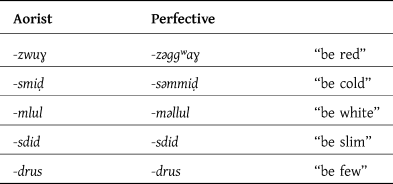

Tashlhiyt retains much the same system as Tuareg, with the difference that the perfective stem has become a prefix conjugation. As a result forms like A -isdid P -sdid “be slim” < A *-isdid P *sădid- and A -idrus P -drus “be few” < A *-idrus P *dărus- have become morphologically indistinguishable from the stative verbs where the perfective can be regularly derived from the aorist, e.g. A -iksuḍ P -ksuḍ < A *-iksuḍ P *-ăksuḍ. But for most verbs the difference in vowel and consonant length still clearly sets them apart from this verb type. Table 6 gives an overview (Sudlow Reference Sudlow2021: 96–7).

Table 6. Qualitative verbs in Tashlhiyt

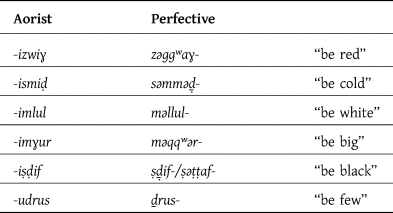

Central Moroccan Berber is similar to Tashlhiyt in this regard, except that it lacks the typical initial i vowel in the aorist (Penchoen Reference Penchoen1973: 53; Oussikoum Reference Oussikoum2013: 423, 742). Due to this missing initial vowel, the aorist and perfective of sdid and drus have merged completely. Table 7 provides an overview.

Table 7. Qualitative verbs in Central Moroccan Berber

Kabyle retains similar forms to that which we find in Tashlhiyt and Central Moroccan Berber, with the difference, however, that Kabyle does retain a suffix conjugation, and thus does not fully merge the *dărus- with *-ăksuḍ type (Naït-Zerrad Reference Naït-Zerrad1994: 217–27; Dallet Reference Dallet1982: s.v.). An overview is given in Table 8.

Table 8. Qualitative verbs in Kabyle Berber

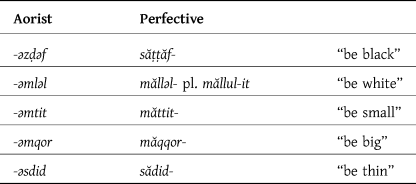

Ghadames retains the suffix conjugation, and has a good number of adjectival verbs of this type. In some cases the aorist has shortened both its stem vowels, and in others only the first one. It is not clear what causes these shortenings (Kossmann Reference Kossmann2013a: 75). Examples are given in Table 9.

Table 9. Qualitative verbs in Ghadames Berber

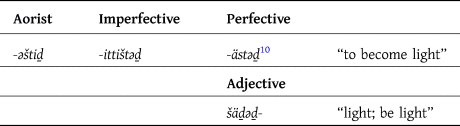

The unpredictability of the stem shape, and difference in conjugation between the aorist and perfective in some of the varieties discussed above, suggest a merger of multiple paradigms into a single verbal paradigm. Zenaga Berber appears to retain an earlier situation where such qualitative verbs still had an independent perfective. Taine-Cheikh (Reference Taine-Cheikh, Lentin and Lonnet2003) convincingly shows that for Zenaga, the etymological equivalent of the qualitative perfective stem, which like other Berber languages takes the suffix conjugation, is not part of the associated verbal paradigm, and should instead be considered a separate qualitative adjective formation. The perfective stem found in Zenaga corresponds perfectly to the *|ăCCiC| pattern that we find in regular stative verbs in Tuareg. This can be clearly seen with the cognate of the Tuareg verb isdad “to be thin” in Zenaga Berber,Footnote 9 shown in Table 10.

Table 10. Qualitative verbs and adjectives in Zenaga Berber

I agree with Galand (Reference Galand1980; Reference Galand and Mukarovsky1990) that this distribution, where this qualitative adjective was not reanalysed as the perfective, is the original situation, and that such suffix conjugation stems seem to form archaic adjectival stems that could be followed by predictive suffixes. This situation appears to not only be retained in Zenaga Berber, but also in the eastern Kabyle variety of At Ziyan, where one finds i-zwiɣ “it/he has become red” contrasting with zeggaɣ-it “it/he is red” (Galand Reference Galand and Mukarovsky1990; Achab Reference Achab2006: 67, 65). This further reinforces that the Zenaga situation is a retention rather than an innovation.Footnote 11 The Zenaga/At Ziyan situation therefore confirms that the qualitative perfectives of Tuareg, Kabyle, Tashlhiyt and Central Moroccan Berber were originally qualitative adjectives that took a special predicative suffix conjugation, which only later were incorporated into a verbal system. From the above discussion it therefore seems possible to reconstruct a Proto-Berber situation, where the qualitative verb had three regular verbal stem forms which were identical to this subclass of intransitive verbs (Prasse's Cj. II); besides that, the same root would have an adjective stem that could be followed by the predicative suffix conjugation.

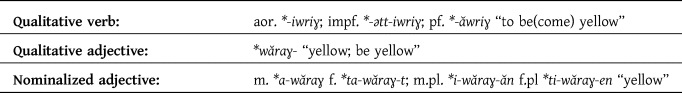

Nominalized forms of these qualitative adjective stems that take the regular nominal prefixes of Berber are fairly well attested as well, and may be reconstructed for Proto-Berber as representing “nominalized adjectives”, e.g. Central Moroccan Berber a-wṛaɣ f. ta-wṛaɣ-t “yellow” besides the verb aor. -wṛiɣ (< *-iwriɣ) impf. -ttwṛiɣ; perf. -wṛaɣ “be/become yellow”. This would seem to further confirm that such qualitative adjective stems are in some way nominal in nature.

Nominalized adjectives can be used attributively in a number of Berber languages (e.g. Figuig asəlham awṛaɣ “a yellow burnous”), but such a function is almost completely absent in others, where relative clauses with the qualitative verbs are preferred instead (e.g. Tashelhiyt, Tuareg). It seems possible that nominalized adjectives did not have an attributive function in Proto-Berber, but were purely nominal (e.g. *a-wăraɣ “the yellow one”). If this is the case, then it is likely that attribution was expressed much as in Tuareg with relative clauses using the qualitative adjectives with the suffix conjugation (e.g. *a-sălsuʔ wa wăraɣ-ăn “the yellow garment”, litt. “the garment which is yellow”). However, an ultimate resolution of this question is outside the scope of this article (but see Galand Reference Galand and Mukarovsky1990 and Chaker Reference Chaker1985 for discussions). A reconstruction of the Proto-Berber qualitative verbs and adjectives is provided in Table 11.

Table 11. Proto-Berber qualitative verbs and adjectives

The Berber qualitative adjectival stems

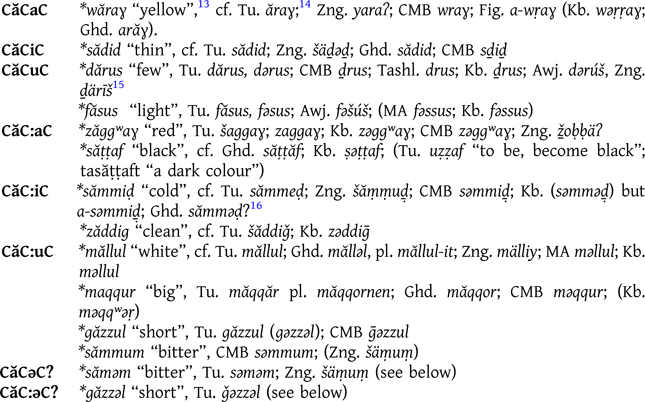

In the above section I have argued that the qualitative perfective is originally part of a system of qualitative adjective stems, rather than being part of the verbal system. There are a variety of stems associated with the qualitative adjective, all of which share a vowel *ă after the first root consonant. The second root consonant may or may not be geminated, and the vowel after the second root consonant may be *i, *u, *a and perhaps also a central high vowel *ə . These stems are lexically determined, and there is no obvious link between the semantics and the formations. Below I give an overview of several well-attested qualitative adjectives reconstructible for Proto-Berber.Footnote 12 Words placed between brackets are words of the same root, but with a different formation:

The pattern *CăCəC for qualitative adjectival stems is rare in Berber. The only example I have identified that might be reconstructible for Proto-Berber is *săməm “bitter; sour; acrid”, whose reflex is found in Tuareg səməm Footnote 17 and Zenaga šäṃuṃ /šaṃəṃ/. However, these forms generally show dialectal variation with the long vowels. This might suggest that this goes back to an original *sămum, which was shortened in these dialects for some unknown reason. Variation in length is also found in several *CăC:əC stems:

-

măqqăr (< *măqqər ?), măqqor “big”

ǧəzzəl, ǧăzzul “short”

məẓẓəǧ, məẓẓaǧ “deaf”

There is some evidence in several Berber varieties that these long and short stems originate from a single paradigm which alternated between a short stem in the singular and a long stem in the plural. Awjila Berber has short/long alternations for all verbs with a geminated second radical (except zə́wwəɣ pl. zəwɣ-ít “red”) (Van Putten Reference Van Putten2014: 97):

-

gə́zzəl pl. gəzzil-ít “short”

-

ɣə́zzəf pl. ɣəzzif-ít “long”

-

lə́qqəq pl. ləqqiq-ít “thin”

-

məllə́l pl. məllíl-it “white”Footnote 18

-

məššə́k pl. məššik-ít “small”

-

šə́ṭṭəf pl. šəttif-ít “black”

-

zə́wwər pl. zəwwir-ít “large”

-

mə́qqər pl. məqqayr-ít (= /məqqir-ít/?) “big”

Similar behaviour is found in one verb in Ghadames (Kossmann Reference Kossmann2013a: 75): mălləl pl. măllul-it “be white”. Săṭṭăf “be black” and ǧăzzəl “be short” always have short vowels, whereas măttit “be small” and măqqor “be big” always have long vowels. Such allomorphy of the adjective stem is found likewise in a number of verbs in Tuareg (Prasse et al. Reference Prasse, Alojaly and Mohamed1998: 438): wăššăr pl. wăššar-a “be old”, rəssəḍ pl. răssoḍ-a “be rotten, foul-smelling”, as well as in a number of zenatic dialects from the Atlas mountains which retain a suffix conjugation such as Ighezran 3sg.m. məlləl 3pl.m. məllul-t “be white” and 3sg.m. məqqʷər 3pl.m. məqqur-t “be big” (Roux Reference Roux1935: 73–5). While this pattern is marginal, the fact that it is widespread confirms that it must be archaic.

This situation could be interpreted as showing that *CăCəC and *CăC:əC stems indeed existed, but that these stems underwent lengthening of the final vowel in the plural.Footnote 19 Due to this allomorphy, many languages levelled the lengthened stem, merging it with the long vowel classes already discussed. Alternatively, perhaps the shortened stems are original for all the singular stems, and many languages have simply levelled out the allomorphy over time.

To sum up, the qualitative adjective stems reconstructible for Proto-Berber are given in Table 12. Notice that there is no sign of the short vowel equivalents of the *CăCaC and *CăC:aC stems.

Table 12. The qualitative adjective stems of Proto-Berber

The Semitic qualitative adjective

Semitic has a suffix conjugation that, at least in the singular, looks similar to the Berber system. However, the Semitic use of this suffix conjugation is quite different from the Berber because of its highly productive system of verbal adjectives that eventually gives rise to the West Semitic perfect system (Hetzron Reference Hetzron1976: 104f.). Such verbal adjectives are completely absent in Berber.

The available verbal adjectives in the basic stem in Akkadian are CaCiC (e.g. damiq- “good”), CaCuC (e.g. zapur- “malicious”) and CaCaC (e.g. rapaš- “wide”), where the first is by far the most common, being used as the regular equivalent of transitive and intransitive verbs; the other two are lexically determined for qualitative verbs (Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard2011: 25f.). This system essentially allows Semitic to productively form new deverbal adjectives.

Besides this regular deverbal CaCiC formation, however, there are also many adjectival formations – likewise with an *a after the first root consonant – which should be considered proper non-derivational qualitative adjectives, such as the CaCīC and CaCūC formations that are rather productive in West Semitic. Such qualitative adjectives stand in a relationship to inchoative verbs of the same root in a rather looser and less strictly deverbal relation, in much the same way as the qualitative adjectives in Proto-Berber,Footnote 20 e.g. Akkadian arrakum “very long”, šakkū̆ru “drunken” (Fox Reference Fox2003: 255, 271). In several such non-productive adjectival formations of verbs that are qualitative in nature, such as Akkadian šakārum “to be(come) drunk”, it seems likely that the adjective šakkū̆ru is the primary adjectival formation, from which an inchoative deadjectival verb form was derived. This is similar to the situation that we find in Proto-Berber, where an originally lexically determined adjectival formation was incorporated in the verbal system of an intransitive verb type.

A notable difference between the qualitative adjectives of Semitic and Berber, however, is that in Semitic such forms clearly and unproblematically function as nouns, which take nominal cases vowels, and can be used as attributive adjectives by postposing them to a governing noun. Whether such nominalized functions existed for Berber is less clear. These qualitative adjectives may also be followed by the predicative affixes to turn them into predicate phrases, and in this regard Berber clearly parallels the Semitic formations.

The Semitic qualitative adjective stems

As in Berber, Semitic has access to a variety of qualitative adjective formations, many of which follow the same basic pattern: *CaC(:)V̄/V̆C. In the following section, I will examine the evidence for qualitative adjectival formations in Semitic using Fox's (Reference Fox2003) discussion of these different formations and I will show that morphologically they coincide quite clearly with the qualitative adjective stems that we find in Proto-Berber. As deverbal derivation of adjectival forms is highly productive in Semitic, many of these stems perform other functions besides the qualitative adjective meaning. For an in-depth discussion of these functions I refer the reader to Fox (Reference Fox2003) – in the following I will only cite forms that establish that qualitative adjectival meanings exist for said stem.

*CaCāC

This pattern is often associated with qualitative adjectives (Fox Reference Fox2003: 179), e.g. Ar. barāʔ “free”, šaǧāʕ “brave”;Footnote 21 Hebr. qåḏoš “holy”, qåroḇ “near”. In Gəʕəz it is the regular feminine counterpart to the masculine CaCīC adjectives (Fox Reference Fox2003: 183): ʕăbiy f. ʕăbay “great”, ṭăbib f. ṭăbab “wise”. Syriac has a few qualitative forms as well (Fox Reference Fox2003: 186), e.g. dwāḏ “insane”, gḇāḥ “bald”.Footnote 22 CaCāC appears to be unattested in East Semitic.

*CaCīC

This pattern is especially productive in Arabic for creating qualitative adjectives (kabīr “big”, qarīb “near” etc.). While not productive in Hebrew, there are several clear examples of it with a qualitative meaning, e.g. nåʕim “pleasant”, ḥåsiḏ “pious”. Gəʕəz, likewise, retains several qualitative adjectives of this pattern, e.g. gäzif “thick”, märir “bitter”, qäṭin “thin”. In Aramaic CaCīC is the regular formation of the passive adjective, but some qualitative adjectives exist, e.g. ḥṯir “proud”, sḇiʕ “full, satiated”. Despite the widespread attestation of this pattern in all of West Semitic, there appears to be no trace of this pattern in Akkadian (Fox Reference Fox2003: 188).Footnote 23

*CaCūC

This pattern is well attested in Semitic, and besides passive participial meaning has quite a few qualitative adjectives associated with it as well, e.g. Hebr. ʕåṣum “mighty” and Gəʕəz qərub “near”, Ar. ḍaʕūf “weak”, samūl “old, worn out”, waqūr “calm”, sakūt “constantly silent”.

*CaC:āC/CaC:aC

The pattern *CaC:āC seems difficult to reconstruct with a qualitative adjectival meaning, although there are clear cases in Gəʕəz, e.g. näwwaḫ “high, long”, nädday “poor”, färrah “fearful”, bähham “mute”, ḫäyyal “strong” and Syriac zakkāy “pure, victorious”, ḥawwār “greedy” (Fox Reference Fox2003: 253).

In Akkadian CaC:aC apparently denotes adjectives, while CaC:āC denotes nouns and substantives (Fox Reference Fox2003: 254, citing Von Soden Reference Von Soden1969: 61f.). Fox points out that there are not many environments where the vowel length is expressed so that this distribution is not necessarily confirmed with the greatest clarity. Adjectives in Akkadian seem to have an intensive or iterative meaning: arrakum “very long”, ṣeḫḫerum “very small”, qattanum “very small”.

Hebrew shows several qualitative adjectives from a CaC:aC pattern, e.g. dawwåy “sick”, ḥallåš “weak”. The regular reflex of CaC:āC is very rare in Hebrew, also as a nominal form. Despite the presence of this formation as a qualitative adjective in disparate branches like Syriac and Gəʕəz, its absence in most other branches makes it difficult to establish as a qualitative adjective pattern in Proto-Semitic.

*CaC:īC

Hebrew shows a large number of qualitative adjectives mostly related to meanings of “greatness” with this pattern ʔabbir “mighty”, ʔaddir “powerful”, ʔammiṣ “mighty”, but also others such as ṣaddiq “just”. Arabic likewise shows signs of this formation, which has shifted to CiC:īC, with qualitative adjectives, often with an iterative or intensive meaning: sikkīt “constantly silent”, ṣiddīq “exceedingly truthful”, šikkīr “drunken”, siḫḫīn “very hot”. Syriac has several examples of qualitative adjectives with this formation as well, e.g. ḥakkim “wise”, zaddiq “just”, rawwiz “happy”. Fox (Reference Fox2003: 267) discusses the Akkadian CaC:īC under CaC:iC nouns, as they are generally orthographically indistinguishable.

*CaC:ūC

Fox (Reference Fox2003: 271) identifies this pattern with qualitative adjectival meaning in all languages he discusses; some examples are: Akk. šakku/ūru “drunken”; Ar. qaddūs “all-holy”, qaʕʕūr “deep”; Hebr. ḥannun “merciful”, ḥaddud “sharp”; Syr. ḥammuṣ “acid, sour”, ʕammuṭ “dark”.

*CaC:iC

Hebrew has a fair number of examples of qualitative adjectives of this pattern; many of them refer to bodily defects and other personal attributes, such as ʔillem “mute”, ʔiṭṭer “crippled”, ʕiqqeš “twisted”, gibben “hump-backed”, ʕiwwer “blind”, piqqeaḥ “seeing well”. No other branches give clear evidence for this formation, so it is doubtful that this pattern is reconstructible for Proto-Semitic. Patterns of CaC:uC do not seem to exist (Fox Reference Fox2003: 253ff.).

*CaCi/u/aC

*CaCiC is the regular verbal adjective formation. As such, *CaCiC is attested with qualitative, stative and passive meanings, especially in Akkadian. Qualitative meanings are attested in all branches, e.g. Akk. labirum “old”; Ar. fariḥ “happy”, ḥazin “sad”; Hebr. kåḇeḏ “heavy”, zåqen “old”; Syriac greḇ “leprous”, ḥḏeṯ “new”. Gəʕəz seems to show no evidence of verbal adjectives of this type at all (Fox Reference Fox2003: 168).

*CaCuC is primarily used to create qualitative adjectives, and in this function is well attested throughout Semitic, e.g. Akk. maruṣ “sick”, rašub “awesome”; Ar. ʕaǧul “quick”, nadus “intelligent”; Hebr. ʕåmoq (fem. ʕămuqqå) “deep”. Syriac and Gəʕəz appear to have lost all traces of this pattern (Fox Reference Fox2003: 174, 177).

*CaCaC is the rarest of these three patterns, but it is present in several branches as a qualitative adjective formation and it is especially well-attested in Hebrew (Fox Reference Fox2003: 162), e.g. Akk. waqar “precious”, rapaš “wide”; Ar. ḥasan “handsome”, baṭal “courageous”; Hebr. ḥåḏåš “new”, yåråq “green”, qåṭån “little”, såḵål “foolish”. Evidence for this pattern is not clearly present in Syriac and Gəʕəz.

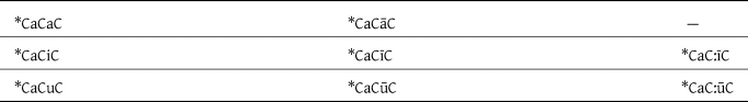

A summary of the stems

To sum up, Semitic, like Berber, forms adjectives by placing a short vowel *a after the first root consonant. The second root consonant may or may not be lengthened, and the vowel after the second root consonant may be any vowel. However, lengthening of the root consonant does not clearly combine with short vowels, nor does it seem to combine with ā. The reconstructed adjectival stems are given in Table 13.

Table 13. The adjective stems of Semitic

Some adjectival patterns that do not belong to the possible stems are left out here. For example, the active participle CāCiC quite frequently has qualitative adjectival meaning in Arabic, e.g. bārid “cold”, but Fox (Reference Fox2003: 237ff.) convincingly argues that this must be secondary, and that this participial formation originally did not apply to qualitative verbs.

Conclusion

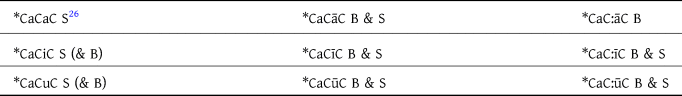

The similarity between the formation of Berber and Semitic qualitative adjectives with the patterns CaCV̄C and CaC:V̄C, combined with the morphological similarity of the suffix conjugation they may receive, makes it highly likely that these patterns originally came from a single shared formation, in a shared ancestor that I call Proto-Berbero-Semitic here.

There is, however, also an important difference. Semitic can freely form deverbal adjectives from intransitive and transitive verbs, whereas Berber adjectives are not obviously deverbal and are exclusively qualitative. It is difficult to imagine the Semitic system to have been present in Proto-Berbero-Semitic and subsequently to have been lost completely in Proto-Berber. Instead, it seems more likely that the Semitic productive derivation of verbal adjectives is an innovation. It is likely this went through several steps. First, qualitative adjectives came to be associated with qualitative verbs (which either already existed, or are deadjectival). After this the verb/verbal adjective pairing that this caused was expanded, presumably first to intransitive verbs and ultimately to transitive verbs, giving rise to the stative and passive adjectives that we find in Proto-Semitic.

The Proto-Berbero-Semitic situation and the subsequent development in Proto-Berber and Proto-Semitic can thus be described fairly easily from a basic qualitative adjectival system in Proto-Berbero-Semitic:

Proto-Berbero-Semitic

1. Qualitative adjectives are formed with *CaCV̄C, *CaC:V̄C (and perhaps also CaCV̆C).

2. Predicative adjectivesFootnote 24 are marked by a suffix conjugation that agrees with the subject in person and gender.Footnote 25

3. Deverbal stative and passive adjectives had not yet developed.

Semitic

1. Semitic forms verb/verbal adjective pairs by associating qualitative verbs with the qualitative adjectives.

2. Adjectival stems develop a regular derivational deverbal adjective.

3. The use of deverbal adjectives is spread to intransitive verbs, and eventually to transitive verbs, giving rise to the Semitic G-stem stative and passive adjectives.

Berber

1. Berber uses the (mostly) intransitive *-iCCiCFootnote 27 verb class to form deadjectival qualitative verbs.

2. (Outside of Zenaga and At Ziyan) the semantic overlap between the stative sense of the perfective, e.g. *y-ăwriɣ “it has become yellow” and the predicative adjective *wăraɣ “it is yellow”, causes the predicative adjective to be incorporated as a suppletive perfective stem of the verb.

The formations of the adjectival stems in Proto-Berber and Proto-Semitic are very similar, and its formation should be reconstructed for Proto-Berbero-Semitic. The biggest points of departure between the two systems are the possible absence of the *CaCV̆C stems in Proto-Berber, and the absence of *CaC:āC stems as a qualitative adjective formation in Semitic. Table 14 gives an overview of the reconstructible adjectival stems.

Table 14. Proto-Berbero-Semitic adjectival formations

It is important to note here that both Berber and Semitic have quite severe stem-shape restrictions. For both language families, other possible stem shapes could be imagined for adjectives, but simply do not show up. For Semitic, this is true for all three CvCC stems (CaCC, CiCC, CuCC),Footnote 28 and reconstructible stems that have a high vowel in the initial syllable (CuCuC, CuCūC, CuCaC, CuCāC, CuC̄uC, CuC̄ūC, CiCaC, CiCāC), and probably also the CāCiC pattern, which was originally restricted to active participles (Fox Reference Fox2003, esp. 291–6).

Berber likewise has many nominal stems which do not have any adjectival value in stem shapes other than the ones discussed above. Some examples are given below, with several easily reconstructible Proto-Berber nouns as examples:Footnote 29

-

CCəC (< *CəCəC?): *a-ɣrəm “village”

CCuC (< *CəCuC): *a-ɣyul “donkey”

CCaC (< *CəCaC?): *a-gmar “horse” (Kossmann Reference Kossmann1999: 151–2)

CeCăC (< *CaCăC): *e-dekăl < *a-dakăl “foot sole”Footnote 30

CuCiC: *a-gugil “orphan” (Kossmann Reference Kossmann1999: 150, 227)

CuCaC: *a-zulaɣ “goat” (Taine-Cheikh Reference Taine-Cheikh2008: 627n1138)

CaCiC: *a-maziɣ “Berber; free person”

The fact that neither Semitic nor Berber has adjectives in these other possible stem shapes, while both share the similarity that adjectives are formed with a *CaC(:)V̄/V̆C pattern, is most likely explained through shared inheritance, rather than a chance correspondence.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Benjamin Suchard, Maarten Kossmann and Lameen Souag for providing valuable feedback on this article.