Introduction

Through a street-level perspective, this paper examines cross-jurisdictional policy interactions between centralised and devolved youth (un)employment policies and programmes. Focusing on the point of delivery we find significant implications for young people framed by a critique of privileging methodological nationalism in welfare regime categorisation. Set against the backdrop of trends towards activation measures across Europe, welfare retrenchment, mixed economies of welfare and work first in the UK, devolved education, skills, training and mental health policy show important variation underpinning interactions at the intersections of youth employment provision. This, crucially, adds timely critique to the privileging of methodological nationalism in the study of welfare regimes (Pearce and Lagana, Reference Pearce and Lagana2023) through a substate lens (Daigneault et al., Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021). The UK is labelled ‘Liberal’ in every international study categorising global welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Bambra, Reference Bambra2007). However, increasing critique of methodological nationalism (Daigneault et al., Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021) and growing evidence of the impact of devolution on social policy (Birrell and Gray, Reference Birrell and Gray2016; Chaney and Wincott, Reference Chaney and Wincott2014; McEwen et al., Reference McEwen, Kenny, Sheldon and Brown Swan2020; Tarrant, Reference Tarrant2023; Needham and Hall, Reference Needham and Hall2023; Birrell, Carmichael and Heenan, Reference Birrell, Carmichael and Heenan2023) poses questions around the label in practice.

Welfare regime typologies based on country averages perpetuate dominant methodological nationalism (Wimmer and Glick Schiller, Reference Wimmer and Glick Schiller2002; Sager, Reference Sager2016; Kettunen, Reference Kettunen2022), which implicitly assumes that nations are congruent entities, homogeneous across social policy domains. In this context, the research presented highlights the importance of attention to subnational welfare regimes when it comes to understanding power dynamics that operate ‘below’ the nation state at regional, provincial or municipal levels (Daigneault et al., Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021, p. 242). Drawing on the case of Britain our findings address the question: What implications do cross-jurisdictional interactions in employment support have for conventional understandings of welfare based on methodological nationalism? Proceeding from a discussion of the devolved policy context, we draw on qualitative interview data to show how differences play out on the ground, reshaping welfare delivery in ways that complicate the UK’s historically centralised approach.

Policy context

The UK

The UK’s welfare regime is increasingly characterised by quasi-Federalism (Gamble, Reference Gamble2021), ongoing central-devolved tensions and power struggles (exemplified by the Brexit negotiations and the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic).Footnote 1 Since 1999 the devolved administrations of Scotland and Wales have steadily accumulated power, status and permanency (Scotland Act 2017 and Wales Act 2017). However, significant areas of social policy remain reserved to the UK Government both interacting with and curtailing the influence of devolved policy. The case of youth unemployment and work insecurity provides a complex mix of devolved (education, skills and training) and reserved (welfare and social security) competencies with ensuing interaction on the ground.

The UK government takes a work first approach to employment support and welfare, focused on moving (young) people into employment (Theodore and Peck, Reference Theodore and Peck2001; Jones and Carson, Reference Jones and Carson2024). The UK government’s employment and welfare policies are delivered through Job Centre Plus (JCP) and more recently Youth Hubs, based within communities in an attempt to overcome the (recognised) intimidating and inaccessible nature of JCP for young people. In August 2024 there were 576,000 unemployed sixteen- to twenty-four-year-olds in the UK (13.6 per cent), and the following month just 296,200 of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds claimed unemployment-related benefits. Based on these figures, approximately half (51 per cent) of unemployed young people are seeking state support through JCP (HoC Library, 2024). In line with work first most UK government employment programmes are compulsory and a core component of the conditions on welfare receipt with job-seeking (hours spent) at its heart. While employment, education, skills and training are devolved to the Scottish and Welsh governments, conditionality and sanctions on welfare are fully reserved to the UK Government. This makes youth unemployment and work insecurity a partially devolved and partially reserved area of social policy, providing rich scope for the study of cross-jurisdictional interactions below the national level.

In the UK, tightening welfare conditionality and increased use of sanctions is framed by a wider shift from passive to active labour market policies (ALMP) internationally, across Europe since the 1990s (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Scullion, Jones, McNeill and Stewart2022, p. 12). Embracing flexicurity has meant decreasing state intervention in the labour market, erosion of employment rights and a stronger ‘push’ into work (Redman et al., Reference Redman, Fletcher, White and Mccarthy2022, 7). In this context, compulsory employment support programmes to increase labour market participation against a backdrop of under- and overemployment, low pay and work insecurity (Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2015; Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Scullion, Jones, McNeill and Stewart2022) negatively impacts quality of work and life, in the longer term reducing chances of finding employment and exacerbating transitions to nonemployment or economic inactivity (Loopstra et al., Reference Loopstra, Reeves, Taylor-Robinson, Barr, McKee and Stuckler2015; Pattaro et al., Reference Pattaro, Bailey, Williams, Gibson, Wells, Tranmer and Dibben2022, p. 611). Behavioural conditionality attributes poverty to the individual’s attitude (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Fletcher and Stewart2020; Wright, Reference Wright2023; Wiggan, Reference Wiggan2015), thus individualising structural problems and political choices.

Fletcher and Redman’s (2022, p. 1) research shows the pervasive influence of this individualisation on the unemployed, who are broadly supportive of capitalistic reforms that precipitate deepening of poverty, health inequalities and insecure poverty labour. Young people not only are the most highly represented age group in any form of insecure work but view insecure work as legitimate and inevitable and as a life stage and the price of autonomy (Trappmann et al., Reference Trappmann, Umney, McLachlan, Seehaus and Cartwright2023). This exacerbates the erosion of welfare (through a decline in unionisation, for example) in an increasingly punitive approach to work first:

…since 2010 the dominant form which labour market interventions towards young people have taken are coercive and disciplinary. Young people have … been targeted by punitive active labour market policies such as the ‘Work Programme’ and ‘Youth Obligation’ (in Etherington Reference Etherington2020, p. 102)

The research for this paper was conducted and analysed during the final, fourteenth year of a Conservative-led UK government. Since being elected to power on 4 July 2024 the Labour Government has announced its New Deal for Working People, underpinned by rights, responsibilities and consequences (UK Government, 2024a). Significant reforms of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) have also been announced by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions. These are highly relevant to the findings presented here and can be summarised as: (1) a new national jobs and career service; (2) new work, health and skills plans for the economically inactive, led by mayors and local areas; and (3) a youth guarantee of employment, education or training anyone aged sixteen to twenty-one years in England. There is also a strong emphasis of devolution in the current government’s Manifesto, King’s Speech and reform announcements.

Scotland

In contrast to the prevailing work first approach in the UK, narrative of the Scottish Government (led by the Scottish National Party since 2007) on employment, work and welfare is underpinned by human rights:

When people use a public service, they should have no concerns about how they will be treated… they should have full confidence that they will be treated with dignity and respect (Scottish Government, 2019: webpage)

Employment support for young people in Scotland is guided by the principle of no one left behind: dignity, respect, fairness, equality and continuous improvement; a person-centred approach; centralised, statutory delivery of employment support; integration and alignment with other programmes; pathways to sustainable and fair work; evidence-based; and supporting people into the right job at the right time. Scotland’s main employment support programme for young people, Developing the Young Workforce, is based on these principles and has had notable success in supporting young people through transitions (DYW, 2019; Scottish Government, 2023). It is a core part of the Scottish Youth Guarantee of employment, education or training.

Social Security is partially devolved to Scotland. Currently the UK government is in the process of transferring approximately 25 per cent of social security competencies to Scotland. Since April 2020 Scottish Ministers have had full legal and financial responsibility for devolved benefits under the Scotland Act 2016 and the Social Security (Scotland) Act (2018). In the meantime, the DWP delivers benefits on the Scottish Government’s behalf under ‘agency agreements.’ Simpson (Reference Simpson2022, p. 68) locates Scotland’s devolved social security system within the ideology of social citizenship citing the strapline of ‘dignity, fairness and respect’ adopted by Social Security Scotland. Significantly, devolved social security in Scotland is seen by Simpson as different to the UK system not least in its deliberate attempt to move away from what has been called a ‘manifestly inadequate’ level of income support which undermines social rights (Simpson, Reference Simpson2022, p. 93).

Wales

Under Welsh Labour since 1999, youth employment support is underpinned by a rights-based ideology which has led to the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act (2014) and the Welsh Youth Guarantee of Employment Education or Training. The Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure (2011) has also incorporated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in Welsh law, putting a legal duty on public bodies to protect the rights of children and young people, upheld by the Children’s Commissioner. Wales, as in Scotland but not England, has put Sections 1–3 of the Equalities Act (2010) into effect, placing a duty on all public bodies to reduce socio-economic inequalities.

One key Welsh employment programmes run through Careers Wales is Jobs Growth Wales+, a £200 million programme giving individualised support to young people and focused on skills, qualifications and experience. ReAct+ is an employment programme targeting young people not in employment, education or training (NEET), under the Youth Guarantee umbrella. The Youth Engagement and Progression Framework, running across all twenty-two local authorities in Wales, aims to identify and respond to young people at risk of becoming NEET and/or homeless. These and other, smaller Welsh youth employment programmes emphasise an individualised or tailored approach to support and are voluntary, most are delivered by the Wales National Career Service in local authorities across Wales.

Social Security in Wales is fully reserved to the UK government; however, as this paper goes on to show, the holistic, voluntary and more generous nature of employment, skills and training in Wales is framed by Welsh Labour’s culture of piecemeal but progressive social policy divergences (Pearce, Sophocleous, Blakely and Elliott, Reference Pearce, Sophocleous, Blakely and Elliott2020).

Methodology: a street-level perspective

The findings presented here are based on street-level data showing ‘patterns of informal practices’ that contribute to political change, capturing a ‘new organizational environment’ (Brodkin, Reference Brodkin2017, pp. 18–19). Deriving from Lipsky’s (Reference Lipsky2010) street-level bureaucracy, which emphasises the power of discretion used for day-to-day interactions by street-level bureaucrats, street-level research since the 1970s has sought to better understand the complex and often disjointed relationship between policy and its delivery. Lived experience of policy implementation reveals complexities and nuances not visible in programme evaluation. In the case of cross-jurisdictional interactions of employment policy and welfare for young people, a street-level perspective is arguably the only way to understand policy co-existence, overlaps and conflict through tensions, dilemmas and accountability (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010).

Many studies have drawn on street-level perspectives to examine work, welfare, sanctions and conditionality in the UK since the 2010/2012 welfare reforms and the start of universal credit rollout in 2013 (Jordan, Reference Jordan2018; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2020; Wright, Robertson and Stewart, Reference Wright, Robertson and Stewart2022) and have shown the importance of front-line studies in understanding what welfare reforms look like in practice with implications for people who are unemployed. Many of these studies focus on young people and youth employment policies or welfare (Cagliesi and Hawkes, Reference Cagliesi and Hawkes2015); however, very few take devolution into account. Despite this van Berkel (Reference van Berkel2020, p. 191) argues that the street-level implementation of welfare conditionality is influenced by wider forces of governance, which presents street-level workers with a variety of signals and incentives that direct their discretion; devolution is no exception.

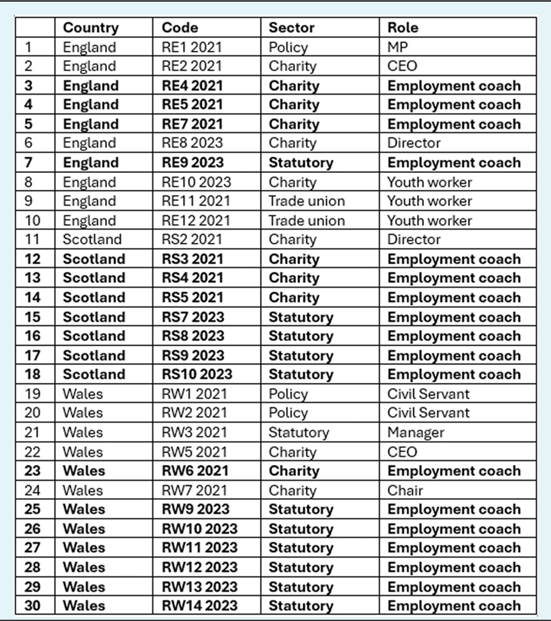

This study draws on thirty qualitative interviews with policy, civil society and employment coach staff in England, Scotland and Wales. Data was collected in two phases – Spring 2021 and Spring 2023 – as part of a three-year Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) New Investigator project (ES/R007314/1).

Table. Respondents

The sample was recruited through, first, purposive sampling drawing on existing links and networks within the research team and then snowball sampling. In most cases the Spring 2021 interviews with more strategic-level roles led to recruitment and interviews with employment coaches, which took place in Spring 2023. Due to the difficulty of DWP access, these employment coaches were recruited from a wider variety of organisations including small, medium and large charities and statutory bodies involved in employment service delivery, making the sample more representative of the welfare provision and employment service delivery landscape in the three devolved nations under study. Importantly, the charities and statutory organisations included are different for England, Scotland and Wales, and therefore offer a unique understanding of distinct devolved contexts, necessary for this research.

The findings presented here are drawn more directly from the twenty employment coach interviews, while the most strategic interviews with civil servants, managers, policy actors and CEOs provide a valuable contextual overview and are detailed in a separate paper (Pearce and Lagana, Reference Pearce and Lagana2023). ‘Employment coach’ is used to refer to anyone on the ground working to deliver employment policy or programmes to young people; for the purposes of anonymity the label is unspecific.

The term ‘employment coach’ refers here to staff employed to work with young people and not JCP staff who are ‘work coaches’; the difficulty of obtaining interviews with JCP staff is well documented and largely due to gatekeeping (Grant, Reference Grant2017; Redman and Fletcher, Reference Redman and Fletcher2022). We have used the term ‘employment coach’ for its broad and deliberately vague nature to protect anonymity, as the devolved programmes use specific terms for their staff working with young people, and using those terms would make clear the organisations involved and violate ethical conduct.

Interviews spanned thirty to ninety minutes and averaged around sixty minutes each. They were analysed using Braun and Clarks’ Reference Braun and Clarke2021) flexible and inductive thematic analysis, which allowed themes to emerge from the data without imposing preconceived frameworks or theories, through identification of recurring patterns, concepts or themes across dataset. Coding was done using NVIVO and generated approximately seventy-five descriptive codes, each of which was manually analysed to draw out categories and themes. Descriptive codes were then categorised to become interpretive codes; for example, ‘JCP’ or ‘DWP’ within the Scottish and Welsh Data became ‘devolved–central interaction’.

The project has received institutional ethical approval and adhered to ethical requirements in full, including strict confidentiality protocol, anonymity throughout and careful, policy-led data management and handling. Throughout we have acknowledged with participants the sensitivity of discussing their role and of potentially being critical of sub- or national- government policies or approaches, encouraging the prioritisation of self-protection and wellbeing during interviews.

Findings

Three themes have emerged from street-level data that illuminate the nuances in devolved employment, education and training provision. They are (1) formal and fluid networks, (2) different devolved approaches to conditionality and sanctions and (3) devolved support for young people beyond job-seeking.

Centralised-devolved working relationships: formal and fluid interactions

The interview data depict different working relationships between Welsh and Scottish employment coaches in their dealings with JCP and DWP staff. Narratives on communication and referrals back and forth between central and devolved programmes appear formalised and linked to strategic-level policy in Scotland and, while also formalised, more fluid and focused on day-to-day (interpersonal) interactions in Wales.

Scottish participants discussed sharing good practice, sharing data and investing in partnerships with the DWP, which was the basis for a formal partnership alongside a pragmatic or instrumentalised take on the relationship with the young person’s best interests at heart. Earlier work has highlighted bureaucratic barriers to effective welfare delivery in quasi-federal systems. Our study also found critiques of the complexity and bureaucracy within JCP coming from Scottish participants. This aligns with what we know about the Scottish Government centralising its youth employment programmes and moving programme delivery over to the statutory sector to decomplexify the notoriously difficult-to-navigate landscape of support available, particularly for young people:

So, I’ll just say it, it’s such a mess. When I [worked in JCP] … I was working with people with additional support needs and disabilities and stuff, and it was just a total, nightmare, trying to get it all sorted from them and making sure they got what they were entitled to. But they needed like massive support, to operate through the system and things… (respondent from Scotland [RS] 8 2023)

Through a more formalised partnership based on acknowledgement of strategic differences, there was a clear separation between the ‘Scottish approach’ and the JCP and DWP approach. One participant discussed the time and effort that goes into generating a genuine understanding of the Scottish political, cultural and employment landscape amongst DWP staff:

I think a lot of the work we have to do with these organisations is for them to understand the Scottish landscape and the Scottish approaches and, and once they get that, they understand the value of working together. You have to invest the time in that to get that right… We’ve got a different education system, we have a different school system… the devolved nature of Scotland can add a complexity … (RS7 2023)

The above quote speaks to the increasing power over social security in Scotland, where employment coaches were, on the whole, comfortable with their working relationships and partnerships with DWP and JCP. However, the formality of these relationships based – at least partly – on Scottish terms, underpinned by a clear awareness of devolved policy and the two-way sharing of best practice, information, support and referrals, reflects the constitutional separation between the two countries. This was not the case in Wales, where relationships were more fluid interactions between street-level staff. Welsh participants related a good day-to-day working relationship with JCP staff:

I’m quite fortunate, my links with the Jobcentre are fab, I’d say my colleagues but obviously they’re not my personal colleagues because they’re an external agency but I work really well as a team and it’s really, really nice to support them. … Just so that we all fit part of a jigsaw puzzle and that we’re not all offering the same or different things and just so people are more clear and concise on how I can support the customer (respondent from Wales [RW] 11 2023)

Unlike in the Scottish data, there were consistent references to the physical closeness of JCP and the Welsh devolved programmes, often in relation to Youth Hubs. This made the referral process even more fluid:

… because we’re physically there for two days a week … [we] have a physical presence there …. The Job Centre usually refers to us first …. (RW14 2023)

I sit in a canteen type style with the team and because this is my base we have a very good open and honest conversation about customers. That happens on a daily basis so we will have regular updates, obviously making sure confidentiality is kept and data protection regulations are adhered to but we share a lot of information to make sure that the paths we’re sending our customers to are aligned and that we’re working in a partnership instead of working in a silo…I don’t think it’s about differences it’s more about the similarities really. There’s a lot of interaction … (RW12 2023)

While formalised systems existed for referrals between JCP and Welsh employment programmes, the fluid, harmonious working relationship enabled a more multifaceted approach where young people are referred to and from Welsh employment coaches:

Usually it’s very early on, so once the claim has started, the minute they have that first interaction there is usually a referral straight away, at that point. If a young person puts in a sick paper, then we’ll say that they’re not ready to engage…Anybody who puts a sick paper into DWP will be formally assessed by a board, just to make sure that they are fit for work, or not. ….Then, depending on that outcome … they’re put into an intensive work search category, they would be referred to us. It’s a regular … it’s all the time. It’s sort of fluid. It’s moving all the time. In fairness to DWP, they try and engage us straight away, as quick as possible (RW10 2023)

While devolved Welsh employment programmes are mentioned, there is not the same sense of a strategic Welsh policy direction to match the Scottish principle of no one left behind or fair start Scotland, for example. Welsh employment programmes are part of the wider offer for claimants (as well as non-claimants) and are presented in practical terms based on a person-centred approach. This belies a working relationship between Welsh devolved and JCP non-devolved coaches based on interpersonal exchanges, with less narrative on formal separation between devolved and centralised policy, government or strategy. Scottish employment programmes are also part of the wider offer for claimants (and non-claimants) and part of that but with an awareness of the Scottish approach.

Conditionality and sanctions: devolved distance and instrumentalisation

This second theme is based on data showing different interpretations and engagement with conditionality and sanctions. Participants in both Wales and Scotland separate themselves and their work from conditionality and sanctions and simultaneously interweave it with day-to-day activity, including through instrumentalisation. The data show devolved programmes impacting and being impacted by conditionality and sanctions through interactions at street level, and from a street-level perspective.

For those facing sanctions for not meeting the conditions of their claim, both Scottish and Welsh data highlighted the value of their formal links (in Scotland) and relationships (in Wales). Scottish employment coaches supporting young people talked about the complex relationship with JCP when it comes to conditionality and sanctions. Many talked about how they dealt with stress and loss of autonomy felt by those facing sanctions or struggling with conditionality:

… we kind of make sure we sit away from any sanction element so when a customer is working with us or they’ve been referred to us from DWP…They can present to us in a very stressed or anxious way because they’re under some form or sanction. There’s a desperation that needs to come into it, and that’s sometimes where we’ve got to maybe spend a bit of time trying to enable the customer, again giving guidance to feel that they have a bit of control over this…. that they still have agency in this (RS7 2023)

Here the devolved employment coach is talking about providing reassurance presented as damage control for young claimants. However, the same employment coach also discussed the potential for sanctions to increase engagement with devolved employment programmes:

…. I suppose if I think of a positive side of it…. I don’t even really want to say it’s positive …. but sometimes the sanction element actually can be the, it’s putting someone into that discomfort zone that will, if you think of the growth model, it makes somebody a bit uncomfortable for them to move into that and need to grow out of this. We can use that with someone (RS7 2023)

Here, the employment coach acknowledges a pragmatic instrumentalisation of sanctions to push someone to seek support from the devolved programmes. This is set in the context of a relative active and effective system of referrals from JCP to devolved employment programmes incorporating without endorsing the use of sanctions.

In Wales, however, due to the active, fluid and interpersonal central-devolved relationship and referral systems outlined above, the Welsh employment coaches seemed to intervene earlier in the process of sanctions, with more discussion around preventing sanctions and less on dealing with the fallout, this involved reassuring JCP employment coaches that the young claimant is engaging.

I think we do everything we can to support young people so that they’re not sanctioned…. I will email their work coach and let them know what they’re doing and say, sorry about this (RW13 2023)

So before any sanctions could be brought in, the Job Centre would talk to [us]… and say, look, they’re not attending, are they attending with you? And we could say, yes they are… (RW14 2023)

The narrative coming from the Welsh data on sanctions is highly relevant to theme three, below, on support for young job seekers beyond job-seeking in devolved jurisdictions. Welsh employment coaches not only talked about trying to prevent sanctions through contact and communication with JCP work coaches but also discussed utilising the full range of devolved employment support available from the Welsh Government:

… if they’re struggling with [attendance] and they need somebody to go with them, then maybe I’d refer to the youth service. I think because we offer the wrap around service from all the provision …. we can work with anyone, it doesn’t matter their situation and we are quite happy to make referrals to whoever is needed because we’ve got that joined up working and we will email a college we will contact the youth service, we will try to prevent those sanctions because it’s just not beneficial for anybody is it? (RW13 2023)

While the Welsh narratives reflected positively on JCP and DWP, they did distinguish between the people they work with (JCP staff) and the systems within which they have to deliver, reflecting more negatively on the latter:

No, I don’t think that Job Centre Plus want to sanction people do they? The work coaches on the ground, they are people, they don’t want to sanction people but it’s their rules isn’t it, so I don’t think they want to do it. … there’s a difference between what goes on in the top and people that are at ground level that are delivering it. … It’s the last chance saloon isn’t it, when they get sanctioned… we all do try to stop it getting to that (RW13 2023)

In Scotland, conversely, and again in line with theme one, employment coaches drew a sharp, clear line between the organisational culture of JCP and their own working practices implementing Scottish employment support for young people and firmly placed responsibility for the damage caused by sanctions on the DWP and UK Government, which further reinforces the Scottish position as more strategically and politically separate from England:

… they’re not our sanctions and they’re not our targets. … our job, my job is not target driven, my job is about building a relationship with young people and about coaching them and hoping that they find something that they enjoy doing…. Whereas the Job Centre is very much more about moving them into something whether it’s correct or not, I would say…Ours is much more about, as I say, guidance (RS9 2023)

… a lot of the young people have been sanctioned because of confidence issues going into the Job Centre, because they’re not ready to access work, because they’re homeless….I had a young girl who was travelling 40 miles to go up to her sign in appointment, and she was being sanctioned because she was late for an appointment every week…I think it would be much more beneficial if somebody spent time and looked at why the young person was being sanctioned (RS9 2023)

Critique of UK Central approach within the Scottish data was directed towards a lack of a person-centred approach, which bring us to theme three.

Support for young jobseekers beyond job-seeking in Scotland and Wales

This final theme shows claimants in Scotland and Wales receiving much more holistic and person-centred support than claimants in England. In Wales the term ‘customer-centred’ (as opposed to ‘claimant’, which was often used by English respondents) recurred throughout the dataset and belied an approach that involved investing time in a young person, building relationships, referring to a wide range of services and supporting each customer to apply for training, work or educational opportunities. Crucially this was done without the goal of moving them into paid employment and without associated targets for doing so:

We’ve got a designated mailbox where DWP can send referrals and, likewise, partner agencies … We get referrals, you know, from everywhere but our approach is very customer-focused. They are the central point of everything we do, so depending on that customer, the barriers, what they’re looking for, their immediate plan, their long-term plan, that would then depend where we would refer them. Each program offers slightly different support, so we make sure that the support they get is tailored and bespoke to them (RW10 2023)

The Welsh data in particular presented a striking narrative around the different types of support and the effective way in which devolved and non-devolved programmes work together to support young people beyond pushing them into employment:

Say for instance …. it is mental health support, I know instantly that I would refer them to an external agency because that is not something I can support them with. I then action plan them, so I say to come in a few weeks, set a date with them and I send them a list of activities or things I would like them to do before the next appointment…. A one [hour] appointment is lovely, you’ve got an hour appointment… I also then book a second appointment where we can review everything and we’re able to move forward from that appointment and provide the best support possible (RW11 2023)

This was coupled with an effective wraparound approach which benefits from flexibility in terms of timelines and needs:

I would say all the way through we’re there for them…specifically the youth, because there’s an advisor in the job centre every week offering appointments …. so they’ve gone in, made a claim and then they will be referred to a careers advisor. We might see them, and they might feel they’re fine, you might have a look at their CV and often …. if they’re going, ‘no, no, I’m fine, I’ll be alright by myself’ …, okay, why don’t we have a catch up in a month’s time just to see how you’re getting on … so I suppose it’s quite fluid … I suppose that’s the flexibility … we’re just always there … quite flexible just whenever they need it. (RW13 2023)

In Wales, as in Scotland, the more person-centred, holistic wraparound of devolved support directly linked to mental health barriers to work:

Since the pandemic we have seen a massive amount of mental health. It’s increased like nothing that I could have ever imagined. The waiting times to get support for mental health are much longer so now, in my opinion, they are much further away from entering the labour market than they were four years ago… (RW10 2023)

The Welsh data in particular revealed the level of support needed by some young people with mental health issues and the support required to make a young person see their worth. In Scotland discussions around mental health as a barrier to work were linked to critique of DWP, JCP, conditionality and sanctions. Scottish employment coaches placed responsibility for causing and then failing to address mental health problems firmly upon UK government:

So we get a lot of young people who have a fit note, who have been told by their doctor they’re not fit to look for work. But they still have to attend the Job Centre. …They’re quite often upset or quite anxious … you really need to be able to explain how the organisations differ…. we’re very much about supporting them when they’re ready, ….whereas the Job Centre, …. they’re very much about you need to get off benefits, you need to look at opportunities …. So the Job Centre will tell him he needs to take a job, any job, because he’s claiming benefits, so again, there’s a conflict there (RS9 2023)

Conversely, in England employment coaches and civil society representatives alike related the centrality of JCP in delivering provision to young people seeking work or needing support. The lack of consistent and holistic provision for support outside JCP was criticised by all respondents and, in one case, aligned with a critique of Youth Hubs. This is in stark contrast to the Scottish and Welsh data which discussed a wide range of holistic support mechanisms:

There’s a group of people out there that are needing extra support… and DWP’s answer is everything flows through job centres. So, it’s like asking what’s, what kinds of life is there outside of our universe? …. with DWP it’s like well, how do you help the people that are outside the job centre… and their answer seems to be well, they should be engaging with job centres and it’s like yeah, okay, so what about those that aren’t? (respondent from England [RE] 10 2021)

Reflections on the difficulties that young people who are unemployed faced from employment coaches in England were linked with the labour market and job opportunities, and to a lesser extent lack of support, notably in contrast with the discussion around social policy and governance so prevalent in the Scottish data:

And as someone who worked in a job centre, during the last crisis, I’ve kind of seen that people were losing their jobs, on the back of the financial crisis, people losing their jobs at the beginning of the coalition government and austerity, young people were still coming in through the door after that, there still kind of not the opportunities being created for them, and not getting the same kind of quality of opportunity within the labour market…. (RE12 2021)

Referral systems and co-working between JCP and non-governmental organisations was discussed only at a local, geographical level and not something happening consistently across England as it is happening in Scotland and Wales. All referrals were about getting young people into work, without exception, rather than a mix of work coaching, career advice, training, looking at educational opportunities or supporting mental health or other barriers:

… [I am] working with work coaches from JobCentre Plus organisations in the area. So, they referred candidates to us, basically to see if they were suitable. If they were suitable, then we also provided employability soft skills development and coaching …. or, if we have opportunities, we will advertise those vacancies… (RE8 2023)

As well as getting young people into work, JCP was depicted by English representatives as working to get young people off benefits and not necessarily into a positive destination:

… Job Centres and work coaches, in my experience, the individual staff do care and want to try and help as much as they can …. [but] their primary focus is …. getting benefit claimants off benefits (RE8 2023)

Some of the Welsh respondents reflected second-hand on English provision:

I know in England …. from dealing with [people] in England they say, ‘You know, there’s no support there,’ and they’re quite shocked to see what we offer. …all I can say is that I feel that the Welsh Government are doing as much as they can for the Welsh people (RW10 2023)

When it comes to employment support in England, participants highlighted the diminishing support for young people in particular:

… I think something that’s missing in all of this, particularly around young people, is that the role of the state, role of governments, institutions, like … Job Centre Plus, to support people, whether they’re in work, or out of work… (RE12 2020)

The closest equivalent to devolved support visible in the English data is a civil society–central government relationship, but as previous research relating to this study shows (Pearce and Lagana, Reference Pearce and Lagana2023), civil society networks and infrastructures in England have been decimated in recent years.

So, we might work with a young person that is potentially working in a retail job, who is degree educated, maybe neurodiverse, may really struggle to break into a professional career. Yet we would have the flexibility, thanks to our private funding, to be able to help that individual. Whereas a government-funded organisation, or the Department for Work and Pensions, is not going to have any contact with them, because They’re not NEET, do you know what I mean? They don’t meet the requirements. So… those kinds of cases, are more generally dealt with by the voluntary sector… (RE8 2023)

Significantly there was an absence of joined-up networks between JCP and organisations providing wider holistic support to young people:

… we received a referral of a young person from a Job Centre fairly recently, and then, upon calling them, one of my team discovered that they didn’t actually speak English. So, someone in a neighbouring flat … was basically translating for this individual, but our understanding was the Job centre was very keen for this individual to find employment. … So, they just simply pointed them to us, because we have a bit of a relationship, but …we’re not an English language-providing organisation….the Job Centre clearly doesn’t have necessarily an understanding of what local services are there. … Whereas I feel our local authority, and those networks and forums, would have a much deeper understanding (RE8 2023)

There is evidence in the English data reinforcing the absence of a person-centred approach within JCP in an English context:

It felt to me like people assumed the worst about young people, were expecting them not to attend appointments. …When I was in the Job Centre, working … ‘Let’s see if this one turns up.’ …. Just low expectations of young people… I have persistently high expectations of young people, but … I don’t expect that they’ll do stuff without support, or without help to overcome barriers, but I think that young people can achieve really great things, given the right circumstances and support (RE9 2023)

The English data did discuss the idea of devolving employment support to local authorities because of the local knowledge and understanding embedded in local authorities, which would allow the development of better referral systems, networks and a wider, more holistic support system. This was coupled with references to the physical and political distance of DWP from the issues faced on the ground:

Job Centres and work coaches, in my experience, the individual staff do care and want to try and help as much as they can …. [but] they don’t have a responsibility, or mandate, to try and connect organisations that have a different interest and would potentially work together. …because their primary focus is …. getting benefit claimants off benefits. Whereas I think local authorities, in my experience, have more of an interest and motivation and responsibility for wider holistic development, bringing together stakeholders who can cooperate towards that end. …. (RE8 2023)

This is highly relevant to the current Labour Government’s plans to devolve employment support in England (DWP, 2024). These discussions on devolved–centralised interactions at local authority level depict local authorities as the solution to the absence of person-centred and holistic support for young people as seen in Scotland and Wales underpinned by devolved policy. The same respondent discussed the aim of having similar referral networks to those we see in the Scottish and Welsh data through localised devolution:

It’s being able to reach out to those Job Centre work coaches and say: ‘Look, what are … What is the situation? What is the regulation here? What can we do to help this young person?’ And in my experience, I know sanctions do happen. But generally, a lot of the individuals I have contact with within the Department for Work and Pensions are genuinely … [looking] for a way to help us navigate the rules and regulations, basically (RE8 2023)

While the data on devolved support presented here are delivered through the different formations identified in theme one, there are striking similarities when contrasted with the English data. Both Scottish and Welsh employment coaches discuss support beyond job-seeking taking a person-centred approach and incorporating the identification of mental health problems as a legitimate barrier to work. The English data depict an absence of the same consistency of support for young people beyond JCP which is acknowledged across the board as being focused on getting young people into work and off Universal Credit (Prandini, Reference Prandini2018). While many holistic, voluntary and supportive employment initiatives – often driven by civil society – run across England, they are not underpinned by a ‘national’ Act or policy as they are in Scotland and Wales, making access to such programmes hostage to geographical or demographic fortune rather than delivering it consistently across the jurisdictional territory.

Discussion and conclusions

What implications do cross-jurisdictional interactions in employment support have for conventional understandings of welfare based on methodological nationalism?

Conventional understandings of employment support and welfare systems are underpinned by a privileging of methodological nationalism (Daigneault et al., Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021). The findings presented here contribute to a growing body of literature on the significance of substate social policy to welfare and rights, often amounting to devolved welfare (Chaney and Wincott, Reference Chaney and Wincott2014; Birrell and Gray, 2016; McEwen et al., Reference McEwen, Kenny, Sheldon and Brown Swan2020; Birrell, Carmichael and Heenan, Reference Birrell, Carmichael and Heenan2023; Needham and Hall, Reference Needham and Hall2023; Tarrant, Reference Tarrant2023). This paper adds further nuance to these approaches by combining substate social policy divergence with cross-jurisdictional policy interactions from a street-level perspective to develop a novel critique of methodological nationalism in the study of welfare. The qualitative and street-level approaches presented here resonate with the work of Daigneault et al., who caution against separating the study of welfare from its roots in quantitative, national-level approaches from qualitative, substate approaches or pitting them against each other; rather with this paper we aim to ‘build bridges between the two literatures’ (Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021, p. 2).

The perspectives presented could not be captured in a national-level analysis and show devolved employment policies in Scotland and Wales actively reshaping welfare delivery in ways that resist the UK’s historically centralised and work first approach. This speaks to wider literature on accountability and the interpretation within service delivery (Skjold and Lundberg, Reference Skjold and Lundberg2022). Street-level workers are simultaneously navigating and coordinating the different work ecosystems as well as the different organisational goals, ethics, ideologies, approaches and normative environments associated with these.

The way cross-jurisdictional, street-level (inter)action driven by substate policy is diverging from the UK’s work first approach is in-line with the devolved government emphasis on territorialising social rights, social citizenship and social justice (Chaney and Wincott, Reference Chaney and Wincott2014; Simpson, Reference Simpson2022; Birrell et al., Reference Birrell, Carmichael and Heenan2023). Within ‘…one of the most centralised welfare-to-work systems [in the world] …’ (Finn, 2015, in Etherington, 2023, p. 113), devolution is influencing the impact of centralised policies on the ground changing the lived experience of young people within delineated policy spaces. These ‘sites of policy conflict’ frame the power of discretion held by street-level workers (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010). While employment coaches as agents of social control are ‘[restrained]…by rules, regulations, and directives from above, [and] by the norms and practices of their occupational group’ (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010, p. 14), such norms and practices are shaped by the complexities, continuities and nuances surrounding the welfare ‘state’ through a devolved lens (Wincott et al., Reference Wincott, Chaney and Sophocleous2023).

Substate organisations delivering employment policy have adapted to the new governance structures since devolution (Brodkin, Reference Brodkin, Brodkin and Marston2013) but are also built on the distinctive socio-economic, cultural, demographic, historical and geographical characteristics that led to devolution in 1999 (Wincott, Chaney and Sophocleous, Reference Wincott, Chaney and Sophocleous2023). The basis for devolution, led by civic nationalism and opposition to the rise of the New Right from 1979, has its roots in social democracy, which the Scottish and Welsh Governments, and local policy spaces, have sought to protect and extend since their creation. In this context ‘landscapes of antagonism’ challenging hegemony through discursive constitution have led to both resistance and alignment (Newman, Reference Newman2014, pp. 3298–3299, in Etherington, Reference Etherington2020, p. 111). These landscapes shape the norms and practices directing street-level workers who play ‘a critical part in softening the impact of the economic system on those who are not its primary beneficiaries’ (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010, p. 14).

While devolved regional and local governance in England must at once deal with and reproduce centralised employment policy and culture (Etherington, Reference Etherington2020), Scotland and Wales can reinforce ideologically driven policy with legislation. However, what we are seeing here is the devolved navigation of centralised policy through both institutional, constitutional or ‘formal’ approaches and the informal, with devolved employment policy interacting directly to provide welfare. The ideological underpinnings of policy driving employment support in Scotland and Wales are represented in a wider, devolved socio-political and institutional culture. The territorialisation of social justice driven through Acts, law and civil society are forging policy spaces and institutional cultures within which street-level workers can use their discretion in different ways – specifically, the way employment coaches delivering devolved programmes negotiate, work around and contend central UK Government policies, work first and the individualisation and internalisation of responsibility for unemployment couched in stigma (Redman and Fletcher, Reference Redman and Fletcher2022).

As a concluding comment, this paper was written shortly before and shortly after the Labour Government was elected in the UK 2024 General Election (4 July), led by Kier Starmer. Many of the themes covered here are highly relevant to this new administration’s plans to reform the Department for Work and Pensions and the welfare system (UK Government, 2024a), as well as its plans for devolution (UK Government, 2024b). This includes plans to work closely with devolved, mayoral authorities and to a lesser extent the devolved governments on employment support.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the JSP editorial team and two anonymous reviewers for a productive, very smooth and engaging process. Huge thanks are also due to the research participants in England, Scotland and Wales for their valuable time and insights. Thanks to the ESRC for funding the research on which this paper is based. Thank you to Dr Giada Lagana for her invaluable work on Phase 1 of the project. Finally, the authors would like to thank the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD) colleagues for their support and particularly Prof Paul Chaney for his time and the valuable knowledge contributed to this paper and the project.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.