Introduction

Skin picking disorder (SPD), also referred to as dermatillomania, psychogenic excoriation, and excoriation disorder, was formally included into the psychiatric classification system as an obsessive-compulsive related disorder (OCRD) in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).Reference Van Ameringen, Patterson and Simpson 1 – Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 The inclusion of SPD in the nosology reflected a growing awareness of the prevalence of SPD, as well as its high comorbidity and morbidity.Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 Nevertheless, many gaps in the literature remain.

First, prevalence rates of SPD markedly varied across studies. In a telephone-based US community survey the prevalence of SPD was 1.4%,Reference Keuthen, Koran, Aboujaoude, Large and Serpe 4 while 5.4% of adults reported significant skin picking associated with distress or impact and, therefore, met criteria for SPD in another US nonclinical population study.Reference Hayes, Storch and Berlanga 5 In both studies the presence of SPD was defined by means of a self-reported instrument. There are notably few epidemiological studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).Reference Prochwicz, Kałużna-Wielobób and Kłosowska 6 – Reference Calikusu, Kucukgoncu, Tecer and Bestepe 8 Furthermore, these studies enrolled convenience nonclinical samples (eg, university students) and used a self-reported tool to assess SPD.

Second, although SPD has been associated with high rates of co-occurring anxiety, mood, substance use, and other OCRDs,Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 , Reference Lochner, Simeon, Niehaus and Stein 9 – Reference Grant, Leppink and Tsai 11 as well as with impaired quality of life (QoL),Reference Grant, Menard and Phillips 12 , Reference Grant, Redden, Leppink, Odlaug and Chamberlain 13 the impact of SPS on QoL dimensions after multivariable adjustment to sociodemographic and clinical covariates (eg, co-occurring mental disorders) remains unclear. Yet the associations of SPD and co-occurring mental disorders and QoL are to a large extent derived from clinical samples, and thus further research in population or nonclinical samples is warranted. Furthermore, in more dramatic clinical situations, SPD may result in significant and even life-threatening medical complications (eg, septicemia),Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 although the association of SPD and suicidality has not been completely elucidated. Finally, a previous community study reported a significant association between skin picking and exposure to childhood sexual abuse.Reference Favaro, Ferrara and Santonastaso 14 A recent small clinical study also found SPD to be associated with exposure to a higher number of traumatic events in childhood, as compared to a control sample.Reference Özten, Sayar, Eryılmaz, Kağan, Işık and Karamustafalıoğlu 15 However, the specificity of this finding deserves further investigation.

Due to the aforementioned gaps in the literature, the current study has 3 aims: (1) to investigate the prevalence of SPD in a large Brazilian sample; (2) to assess sociodemographic and clinical correlates of SPD; and (3) to determine the independent impact of SPD on QoL dimensions.

Methods

Sample selection

Consecutive participants (N=9,603) were recruited through a large Web-based Brazilian study (Portal Temperamento e Saúde Mental, www.temperamentoesaudemental.org), which is a project that aims to investigate the frequency and correlates of several disorders and psychopathological conditions through the use of validated self-reported measures.Reference Lima, Köhler and Stubbs 16 , Reference Nunes-Neto, Köhler and Schuch 17 This Website provides an encrypted and confidential platform for data collection. The research ethics committee of the Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio (HUWC) approved the procedures for online data collection under the protocol number 1.058.252. To access the surveys, participants were required to be at least 18 years old and to sign a digital informed consent form. Potential participants were individuals living in Brazil who had internet access; no incentives were granted for participation in this survey. Several attention and validation questions throughout the protocol were employed to assess the quality of the data. Those questions included, for example, “How old are you?” and “How much attention are you paying while answering to this survey?” Consistency of responses were verified (ie, participants had previously provided their dates of birth), while participants who indicated that they were not paying adequate attention to the questionnaires were excluded. This exploratory study included participants who had provided valid responses to these questions. From the initial sample, 9,585 participants answered the complete survey. After quality checking, 7,639 subjects remained eligible (ie, provided correct responses to the validation/attention questions) and were included in the final analyses (response rate: 79.7%). There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender distribution, and education level between participants who were not included in the final sample compared to those that did not pass our quality check, and hence were included in final analyses (data available upon request).

This online survey collected sociodemographic data (age, sex, educational level, ethnicity, marital status, religious affiliation, occupation, and gross monthly income). In addition, the web-based platform included several validated psychological and psychiatric measures, which are described below.

Measures

Skin Picking Stanford Questionnaire (SPSQ)

The SPSQ is self-report measure that comprises 13 questions that address the phenomenology of SPD using a yes/no/don’t know format.Reference Keuthen, Koran, Aboujaoude, Large and Serpe 4 The authors of the current study decided a priori to eliminate from the original version of the questionnaire the question “Could you write the name of that medical condition?”, which refers to a possible underlying medical condition that could explain the skin picking behavior. This question is not essential to the case definition of SPD based on DSM-5 criteria. 2 However, we maintained the question “Do you pick your skin because it is inflamed or itchy due to a medical condition?”, which is consistent with the DSM-5 exclusion criterion. This 12-item modified version of the SPSQ was translated to Brazilian Portuguese, then back translated into English. Three bilingual authors (MOM, CAK, and AFC) compared the back-translated version to the original version of the SPSQ, and modifications to ensure semantic equivalence were performed. This Brazilian Portuguese version of the SPSQ was tested in a pilot sample of 5 outpatients of the psychiatry service of the HUWC who reported no difficulties in understanding items of this instrument. Six experts in the field of OCRDs (see the “Acknowledgments” section of this article) provided a qualitative assessment of the content validity of the SPSQ. In brief, experts were asked to provide comments on each item of the SPSQ regarding grammar, wording, scaling, and item allocation, as well as the accuracy, clarity, style, and relevance of the translation. We calculated the content validity index (CVI) as described in detail elsewhere.Reference Câmara, Köhler, Frey, Hyphantis and Carvalho 18 , Reference Lawshe 19 To compute the CVI, members of the expert panel were asked to rate each SPSQ item in terms of relevance, clarity, and simplicity on a Likert scale from 1 to 4 (1 was the lowest grade in each of these aspects, while 4 was the highest). The CVI for each item was computed as the number of experts assigning a rate of 3 or 4 to the item divided by the total number of experts. The overall SPSQ CVI value was obtained by averaging all items. The overall CVI of the modified Brazilian Portuguese version of the SPSQ was 0.94 (range for individual items: 0.67–1.00), thus supporting its content validity. In the current sample, the modified SPSQ also had adequate internal consistent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.73; 95% CI: 0.72–0.74). The final modified Brazilian Portuguese version of the SPSQ is provided in the Supplementary Material (available online). A positive screen for SPD was considered when study participants provided affirmative responses to questions 6, 7, and 8 of the SPSQ. In addition, participants had to endorse at least one additional manifestation of SPD (ie, at least 1 affirmative response to questions 3, 4, and 5 of the SPSQ).

Hypomania checklist (HCL-32)

The HCL-32 consists of 32 yes/no questions, and investigates the presence of a wide range of (hypo) manic symptoms.Reference Angst, Adolfsson and Benazzi 20 Participants were asked to focus on the “high” periods and to indicate whether hypomanic manifestations were present during this state. In addition, the HCL-32 includes 8 severity and functional impact items related to the duration of episodes and to positive and negative consequences over different areas of functioning. We used the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the HCL-32 with the recommended cutoff of 19 for nonclinical samples.Reference Soares, Moreno, Moura, Angst and Moreno 21 In addition, for a positive screening for a bipolar spectrum disorder, participants had to endorse an impairment in at least 1 area of functioning due to the presence of hypomanic symptoms. A previous meta-analysis supports the accuracy of the HCL-32 for the screening of bipolar spectrum disorders.Reference Carvalho, Takwoingi and Sales 22 In the current sample, the reliability of the HCL-32 instrument was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha=0.82; 95% CI: 0.81–0.82).

Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the PHQ-9.Reference Santos, Tavares and Munhoz 23 The PHQ-9 questionnaire is a self-report instrument that employs the 9 DSM-IV symptom-based criteria for screening of major depressive episodes.Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams 24 A positive screening for a major depressive episode was established based on an algorithm in accordance with the validation study of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the MDQ, which was performed in the general population. Furthermore, we used question 9 of the PHQ-9 (ie, “Having thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself on at least 2 days over the past 2 weeks”) to screen for the presence of suicidal ideation.Reference Choi and Lee 25 The Cronbach’s alpha of the PHQ-9 in the current sample was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.88–0.89).

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

We used the validated Portuguese version of the FTND to screen for the presence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence.Reference de Meneses-Gaya, Zuardi, de Azevedo Marques, Souza, Loureiro and Crippa 26 In brief, the FTND is a 6-item self-report questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 10.Reference Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker and Fagerström 27 A cutoff score of 4 on the FTND was considered as indicative of nicotine dependence in the current study.Reference de Meneses-Gaya, Zuardi, de Azevedo Marques, Souza, Loureiro and Crippa 26 The Cronbach’s alpha of the FTND in the current sample was 0.74 (95% CI: 0.71–0.76).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

We used the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the AUDIT to screen for the presence of alcohol use disorders.Reference Lima, Freire, Silva, Teixeira, Farrell and Prince 28 In brief, the AUDIT is a 10-item self-report questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to screen for the presence of alcoholism (formerly referred to as hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption).Reference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente and Grant 29 A score≥8 was considered indicative of the presence of an alcohol use disorder.Reference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente and Grant 29 In the current study, the AUDIT had adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.83; 95% CI: 0.82–0.83).

Early Trauma Inventory Self Report–Short Form (ETISR-SF)

We used the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the ETISR-SF to assess exposure to early trauma.Reference Osorio, Salum, Donadon, Forni-Dos-Santos, Loureiro and Crippa 30 This is a self-report instrument that comprises 27 items grouped into 4 dimensions (general trauma, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse).Reference Bremner, Bolus and Mayer 31 The ETISR-SF exhibited adequate internal consistency reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86; 95% CI: 0.86–0.87).

Symptom Checklist-90–Revised Inventory (SCL-90R)

We used the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Symptom Checklist-90–Revised inventory (SCL-90R) to assess psychopathological dimensions.Reference Carissimi 32 , Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos 33 Briefly, the SCL-90R is a 90-item, 5-point, Likert-type inventory, which assesses several psychopathological dimensions namely somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the SCL-90R dimensions ranged from 0.79 (95% CI: 0.79–0.80) for paranoid ideation to 0.92 (95% CI: 0.91–0.92) for the depression dimension.

World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument–Abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF)

We used the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the WHOQOL-BREF to assess QoL dimension in the current study.Reference Fleck, Louzada and Xavier 34 This generic instrument consists of 26 items assessing QoL in four dimensions: physical, psychological, social, and environment QoL. 35 Each item is rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale, and scores are transformed on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher QoL. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.80 (95% CI: 0.80–0.81), 0.83 (95% CI: 0.82–0.84), 0.68 (95% CI: 0.67–0.70), and 0.79 (95% CI: 0.78–0.79) for the physical, psychological, social, and environment domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out by means of SPSS (IBM, US) version 22.0 for Windows. Continuous variables are presented as means±standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess whether variables displayed a normal distribution. Sociodemographic and psychopathological variables were compared between participants with vs those without SPD. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using independent samples Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

The associations of SPD (dependent variable) and a positive screening for MDD, BD, alcohol or tobacco use disorder, trauma, and suicide ideation, as well as SCL-90 R psychopathological domain scores were assessed using separate multivariable logistic regression models. For the association of SPD and psychopathological dimensions, the scores of each SCL-90 domain were entered as continuous independent variables in the model. For the association of SPD with suicidal ideation, the PHQ-9 question 9 response was entered in the model as a categorical variable. For the associations of SPD and trauma domains, the scores of each individual ETISR-SF domain were entered as continuous independent variables. All other independent variables were categorical. All multivariable models were adjusted by age, sex, occupation, previous use of psychotropic drugs, education level, and ethnicity. Multivariable models that assessed the presence of suicidal ideation, as well as exposure to early life trauma, were additionally controlled for the presence of a positive screening for a major depressive episode, bipolar spectrum disorder, nicotine dependence, and alcohol dependence.

The associations of the presence of SPD and each WHOQOL-BREF domain (dependent variables) were analyzed through separate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models. Each model was adjusted by age, sex, occupation, family history of mental disorders, previous use of psychotropic drugs, education level, ethnicity, marital status, gross monthly income, presence of a positive screening for a major depressive episode, bipolar spectrum disorder, a positive screen for suicidal ideation, nicotine dependence, and alcoholism. In addition, we estimated effect sizes of statistically significant (independent) associations of a positive screening for SPD and QoL domains with partial eta squared (ηp 2); effect sizes were regarded as small, medium, and large when 0.01<ηp 2<0.06, 0.06≤ηp 2<0.14, and ηp 2≥0.14, respectively.Reference Cohen 36 In addition, we estimated the internal consistency reliability of each instrument used in the current study through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (and 95% CIs). Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The total sample had a mean age of 27.2±7.9 years, was predominantly composed of women (71.3%), and most of the individuals had at least secondary-level education. The prevalence of probable SPD was 3.4% (95% CI: 3.0–3.8%). In addition, the prevalence of probable SPD was significantly higher among women, but was not associated with age or different age groups. Furthermore, participants with probable SPD significantly differed from those without SPD regarding occupation and ethnicity. Finally, participants with probable SPD were more likely to have used psychotropic agents (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics of study participants

a Pearson’s chi-square test.

b Fisher’s exact test.

c Two-tailed Student’s t test.

d Refers to an ethnic group of mixed white and black ancestry.

*Observed was higher than expected in this cell (adjusted residual>2).

**Observed was lower than expected in this cell (adjusted residual<–2).

Clinical correlates of SPD

The presence of probable SPD was significantly associated with a positive screening for a major depressive episode (ORadj=1.854), nicotine dependence (ORadj=2.058), alcoholism (ORadj=1.570), as well as a positive screening for suicidal ideation (ORadj=1.427), but not for bipolar spectrum disorders (Table 2).

Table 2 Psychopathological correlates of skin picking disorder (SPD)

Abbreviations: AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BSD=bipolar spectrum disorder; ETISR-SF=Early Trauma Inventory Self Report – Short Form); FTND=Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; HCL-32=Hypomania Checklist; MDE=major depressive episode; PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire; RASS=Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale; SCL-90=Symptom Checklist 90.

a Adjusted for age, gender, education, ethnicity, occupation, and history of psychotropic medication use.

b Adjusted additionally for a positive screening for MDD or BD, and tobacco or alcohol use disorder.

c Per unity increase in dimension score.

d Bold values are significant at a 5% alpha level after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

e Nagelkerke R2 (ie, coefficients of determination) of each multivariable logistic regression model.

The presence of probable SPD was also independently related with the obsessive-compulsive (ORadj=1.339; P=0.02) and hostility (ORadj=1.300; P<0.01) dimensions of the SCL-90R. Moreover, SPD was associated with lower scores in the SCL-90R interpersonal sensitivity dimension (ORadj=0.759; P=0.04) (Table 2).

Finally, SPD was significantly associated with exposure to general traumas, psychological abuse, and sexual abuse early in life, but not with physical abuse. However, only associations with general traumas (ORadj=1.070; P=0.03) and psychological abuse (ORadj=1.216; P<0.001) survived multivariable adjustment to co-occurring mental disorders and sociodemographic covariates (Table 2).

Impact of SPD on quality of life domains

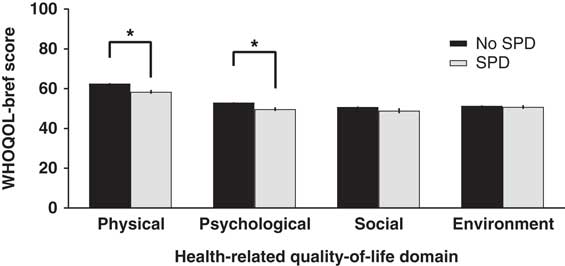

Probable skin picking disorder was significantly associated with impaired physical and psychological QoL (Figure 1), even after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and comorbidity. However, the presence of probable SPD was not significantly associated with social and environment QoL. All ANCOVA models were statistically significant (adjusted R2 values ranged from 0.195 to 0.442). Effect sizes for the adjusted associations of a positive screen for SPD and physical (ηp 2=0.33) and psychological (ηp 2=0.44) QoL domains were large.

Figure 1 Associations between the presence of skin picking disorder (SPD) and physical, psychological, social, and environment quality of life as assessed with the WHOQOL-BREF. * P<0.05 (separate ANCOVA models adjusted for sociodemographic and psychopathological variables; see the Methods section for further details). Scores of WHOQOL-BREF domains are presented as means and 95% CIs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest survey on the prevalence and correlates of SPD conducted to date. The point prevalence of probable SPD in our sample was 3.4% with a notable preponderance among women. The prevalence estimate here is within the range of previous community studies that were conducted in the US, and where point prevalence varied from 1.2% to 5.4%,Reference Keuthen, Koran, Aboujaoude, Large and Serpe 4 , Reference Hayes, Storch and Berlanga 5 , Reference Monzani, Rijsdijk, Cherkas, Harris, Keuthen and Mataix-Cols 37 while the prevalence of possible SPD was 7.6% in sample of Polish students 6 and 9.0% in a sample of 3 medical colleges from Karachi (Pakistan).Reference Siddiqui, Naeem, Naqvi and Ahmed 7 Possible sources of heterogeneity in prevalence rates across studies deserve further investigation. For example, Keuthen et al Reference Keuthen, Koran, Aboujaoude, Large and Serpe 4 performed a telephone-based survey and the presence of possible SPD was assessed with the SPSQ, while the Skin Picking Scale was used in another US community study that included a smaller sample who underwent face-to-face interviews.Reference Hayes, Storch and Berlanga 5 In addition, settings and populations have varied across studies. For instance, a prevalence of 5.4% of possible SPD (assessed by means of the SPSQ) was verified in a study that enrolled Israeli Jewish and Arab clinical samples,Reference Leibovici, Koran and Murad 38 while prevalence rates of possible SPD were 7.6% and 9.0% among Polish university students and medical students from Karachi (Pakistan) respectively.Reference Prochwicz, Kałużna-Wielobób and Kłosowska 6 , Reference Siddiqui, Naeem, Naqvi and Ahmed 7 Thus, differences in tools used to assess the presence of possible SPD as well as differences in sample selection and settings across studies could have contributed to these discrepant findings. Furthermore, although not all studies are consistent, accumulating evidence indicates that SPD is more prevalent among women.Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 The present data add to the small number of studies that have been thus far conducted in low- and middle-income countries.Reference Prochwicz, Kałużna-Wielobób and Kłosowska 6 – Reference Calikusu, Kucukgoncu, Tecer and Bestepe 8 Our study also explored several clinical correlates associated with SPD with the use of validated self-report instruments, and found that SPD has a detrimental impact on physical and psychological QoL, even when controlling for sociodemographic variables and comorbidity.

Clinical correlates of SPD

In the current study, SPD was associated with a positive screening for a major depressive episode, nicotine dependence, and alcohol dependence, even after adjustment for potential confounders. Those findings are consistent with studies conducted in clinical samples. For example, although the prevalence of major depressive disorder has varied across studies (from 12.5% to 48.0%),Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 , Reference Grant, Leppink and Tsai 11 the data suggest that depression is more common among patients with SPD than in the general population. In addition, previous studies that enrolled clinical samples with SPD also pointed to high prevalence rates of co-occurring substance use disorders, including alcohol and tobacco use disorders.Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 , Reference Lochner, Simeon, Niehaus and Stein 9 , Reference Flessner and Woods 10 This finding is arguably consistent with a recent framework conceptualizing SPD as a “behavioral addiction,” which may share some phenomenological and neurobiological similarities with substance use disorders.Reference Chamberlain, Lochner and Stein 39

No significant association was found in our sample between SPD and a positive screening for bipolar spectrum disorder. Previously, a 10.5% prevalence of pathologic skin picking was reported in a sample of outpatients with bipolar disorder,Reference Karakus and Tamam 40 but this investigation lacked a control (ie, comparison) group. A possible association between SPD and bipolar disorder does, however, deserve further investigation. In addition, we observed that SPD is associated with a positive screening for suicidal ideation that survived multivariable adjustment to potential confounders, including co-occurring affective disorders and alcohol use disorder, which are mental disorders associated with a higher suicide risk.Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki 41

As far as the SCL-90R is concerned, in our sample SPD was associated with the obsessive compulsive and hostility dimensions, with lower scores in the interpersonal sensitivity dimension. This finding suggests that SPD might share significant clinical and biological characteristics with other OCRDs,Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 , Reference Odlaug, Hampshire, Chamberlain and Grant 42 while the negative association with the interpersonal sensitivity dimension may be consistent with the view that OCRDs could be associated with anankastic personality features.Reference Stein, Kogan and Atmaca 43 However, it should be noted that a small study (N=92) indicated that participants with chronic skin picking exhibited elevated scores in experiential avoidance.Reference Flessner and Woods 10 Nevertheless, the small sample and the lack of a comparison group in that previous study may limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, no previous study had specifically addressed the possible comorbidity of SPD with social anxiety disorder. In the current study, the presence of SPD was assessed by means of a reliable self-report measure. Yet the severity of SPD was not evaluated in this study. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the association of SPD and interpersonal sensitivity could be moderated by the severity of SPD.

The association between SPD and exposure to childhood trauma (general traumas and psychological abuse) are consistent with other studies.Reference Favaro, Ferrara and Santonastaso 14 , Reference Özten, Sayar, Eryılmaz, Kağan, Işık and Karamustafalıoğlu 15 However, the specificity and impact of a history of early life trauma remains to be established. It is noteworthy that other OCRDs (eg, OCD and trichotillomania) may also be associated with childhood trauma.Reference Stein, Kogan and Atmaca 43 , Reference Lochner, Seedat and du Toit 44

Associations of SPD and QoL

Participants with SPD in our sample had significantly impaired physical and psychological QoL even after multivariable adjustment to sociodemographic and clinical variables. In addition, our data are consistent with available evidence that indicates SPD is associated with significant medical and psychological burden.Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain, Keuthen, Lochner and Stein 3 , Reference Grant, Redden, Leppink, Odlaug and Chamberlain 13 Nevertheless, SPD was not associated with impaired social QoL. Although this finding is in agreement with the observation that participants with SPD exhibited lower scores in the interpersonal sensitivity dimension of the SCL-90R, it needs to be replicated, as it may also could be modified as a function of the severity of SPD. The instrument used in this survey (ie, the SPSQ) is primarily designed to screen for SPD,Reference Keuthen, Koran, Aboujaoude, Large and Serpe 4 and not to rate the severity of this illness. Therefore, further research is warranted to assess the putative role of SPD’s severity on the associations with QoL herein described.

Strengths and limitations

Some limitations of the current study deserve to be underlined. First, we enrolled a convenience Web-based sample with a predominance of young women that may not be representative of the Brazilian population. Second, although we used validated self-report measures in our study, a positive screening for SPD or other co-occurring disorders was not confirmed by means of a validated structured diagnostic interview. However, it should be noted that all instruments used in the current study exhibited adequate internal consistency reliabilities. Third, it is possible that this Web-based project attracted a greater proportion of participants with mental disorders, and hence the prevalence of SPD could have been over-estimated. Fourth, the cross-sectional design of the current study precludes the establishment of causal inferences. On the other hand, strengths of our study include the recruitment of a large sample and the employment of validated instruments with a widespread use in the scientific community. Furthermore, anonymous participation via Internet provides a setting with low desirability bias to answer to those instruments. This could be especially relevant in the case of OCRDs like SPD, in which there is a long delay from the onset of symptoms to treatment initiation at least partly due to the “shame” individuals may experience due to their underlying condition.Reference Hollander, Doernberg and Shavitt 45

Conclusions

The current survey provides data to support the view that SPD could be a prevalent condition associated with significant comorbidities (namely depression, as well as tobacco and alcohol use disorders). In addition, SPD was associated with significantly impaired physical and psychological QoL even after adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical variables. Our findings may have some implications. First, efforts toward the early recognition of SPD (and associated comorbidities), particularly in at-risk settings (eg, dermatological clinics), seem to be warranted. In addition, future studies should investigate the determinants of QoL among people with SPD and consider using QoL as an outcome for therapeutic interventions targeting SPD.

Disclosures

Myrela Machado, Cristiano Köhler, Brendon Stubbs, Paulo Nunes-Neto, Ai Koyanagi, João Quevedo, Thomas Hyphantis, Donatella Marazziti, and Michael Maes have nothing to disclose. Jair Soares has the following disclosures: Pat Rutherford, Jr Endowed Chair in Psychiatry, personal fees; John S. Dunn Foundation, grant; National Institute of Mental Health, grant number R01MH085667-01A1; Bristol-Meyers Squibb, research support; Forest Laboratories, research support; Merck, research support; Elan Pharmaceuticals, research support; Johnson & Johnson, research support; Stanley Research Institute, research support; National Institutes of Health, grant; Pfizer, served as a consultant; Abbott, served as a consultant; Astellas Pharma, served as a consultant. Dan Stein has the following disclosures: Lundbeck, personal fees; Novartis, personal fees; SUN, personal fees; CIPLA Inc., personal fees; AMBRF, personal fees; NRGF, grant; Servier, grant; Biocodex, grant; MRC, grant. André Carvalho reports grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) during the conduct of the study.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918000871