German federal elections have long drawn international attention due to the country’s economic influence and its pivotal role in the European Union. Over time, forecasting these elections has evolved into a sophisticated discipline, incorporating diverse models and refined methodologies to improve accuracy. Since 2013, PS: Political Science & Politics has played a key role in tracking these developments by publishing three special symposia dedicated to forecasting German elections (Jérôme Reference Jérôme2013, Reference Jérôme2017; Jérôme and Graefe Reference Jérôme and Graefe2022). This 2025 symposium marks the fourth installment, continuing a tradition of providing scholars with a platform to share insights and reflect on the field’s ongoing expansion.

THE EVOLUTION OF GERMAN ELECTION FORECASTING

Other than the pioneering work of Jérôme, Jérôme-Speziari, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Jérôme, Jérôme-Speziari and Lewis-Beck1998) and Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth and Gschwend2003), whose foundational models focused on economic performance and leadership evaluations as key indicators, forecasting German elections remained largely overlooked for many years. In the first PS German election forecasting symposium, efforts to predict the 2013 election were based primarily on refined versions of these two earlier models (Jérôme Reference Jérôme2013). The 2017 symposium marked a shift, with a broader range of forecasting techniques being included (Jérôme Reference Jérôme2017). Kayser and Leininger (Reference Kayser and Leininger2017) proposed a Länder-based approach, which incorporated regional political and economic data. Graefe (Reference Graefe2017) presented the PollyVote method—a combined forecasting approach previously utilized in US presidential elections since 2004 as well as in the 2013 German election. By 2021, German elections forecasting had become notably more comprehensive, as evident in that year’s symposium. Eight contributions from 19 researchers highlighted increased interest in innovative predictive models (Jérôme and Graefe Reference Jérôme and Graefe2022). Existing methods, such as the PollyVote and the Länder-based model, were updated and refined, and new approaches also emerged. The Zweitstimme model (Gschwend et al. Reference Gschwend, Müller, Munzert, Neunhoeffer and Stoetzer2022), for example, used Bayesian inference to integrate polling data with key political factors, and the citizen-forecast method focused on voter expectations rather than direct voting intentions.

THE 2025 GERMAN ELECTION: CONTEXT, OUTCOME, AND FORECASTS

The 2025 election, originally set for September, unexpectedly was moved up to February 23 on short notice, after the collapse of the SPD–Greens–FDP “Traffic Light Coalition,” which was triggered by the Free Democratic Party (FDP) withdrawal. This sudden shift occurred amid a complex political landscape shaped by the emergence of new parties including the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), founded in January 2024, and the continued rise of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), established in 2013.

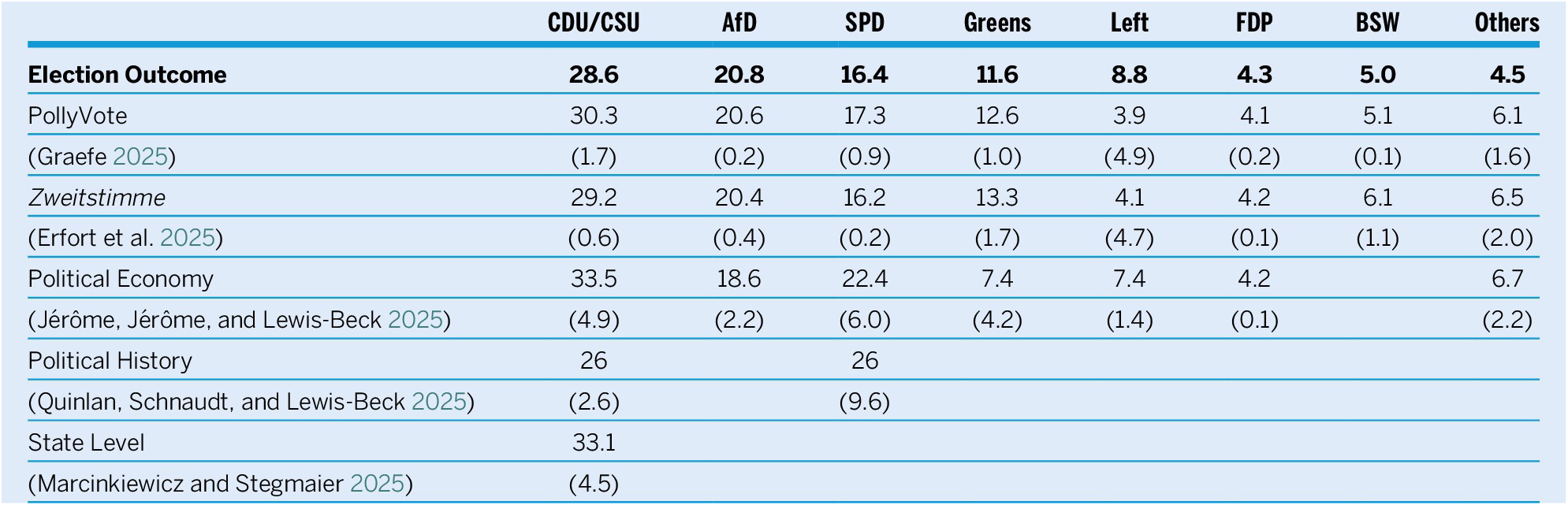

The election outcome yielded significant shifts in Germany’s political landscape. Table 1 shows the vote shares achieved by each party. The Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) alliance, led by Friedrich Merz, secured a plurality with 28.5% of the vote, marking a modest gain from 2021 but still less than historical highs. The far-right AfD achieved a record 20.8%, becoming the second-largest party in the Bundestag. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) suffered its worst postwar result, garnering only 16.4% and falling to third place. The Greens received 11.6% and The Left (Die Linke) rebounded to 8.8%, after previously failing to surpass the 5% threshold in the 2021 election. Both the FDP and the newly formed BSW failed to surpass the 5% threshold, thus not entering parliament. In the absence of viable alternatives, the CDU/CSU and SPD formed a grand coalition, commanding 328 of the 630 seats.

Table 1 Predicted and Actual Vote Shares in the 2025 German Federal Election

Notes: Absolute errors are in parentheses. Empty cells indicate that a model did not provide a forecast for that party. BSW missed the 5% threshold with 4.98% of the vote. Forecasts are ordered by the number of available forecasts and accuracy.

ATTEMPTS TO FORECAST THE 2025 GERMAN ELECTION

Due to the election’s sudden rescheduling, the 2025 symposium had to be organized on short notice—a key reason why it includes fewer contributions than in previous years. Nonetheless, it includes five contributions, presented in table 1, from a total of 14 researchers.

Graefe (Reference Graefe2025) presents the combined PollyVote forecast, which averaged predictions from three different methods: polls, expectations (i.e., betting markets), and models. The following four models are part of this symposium:

-

1. Erfort et al. (Reference Erfort, Stoetzer, Gschwend, Koch, Munzert and Rajski2025) present their Zweitstimme model—a dynamic forecasting tool that combines voting-intention polls with political-economy fundamentals, and which already was featured in the 2017 and 2021 PS symposia. Their latest innovation integrates individual survey data into the existing model, which allows for predictions of party vote shares as well as candidate support at the constituency level.

-

2. Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier (Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2025) focus on forecasting outcomes for the CDU/CSU using a state-level approach. Their model integrates economic indicators (e.g., GDP growth), social factors (e.g., religious affiliation), and political variables (e.g., past party performance). The model evaluates the current political climate through public-opinion data on the popularity gap between the CDU/CSU’s chancellor candidate and the SPD’s candidate.

-

3. Quinlan, Schnaudt, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Quinlan, Schnaudt and Lewis-Beck2025) build on the premise that political history often follows recurring cycles, which allows the identification of patterns that are likely to repeat. Although this model maintains the structural framework of traditional voting models, it moves away from conventional variables (e.g., the state of the economy and public opinion), focusing instead on politically historical variables (e.g., coalition frequency). To develop their model, the authors constructed a historical voting model based on data from 1951 to 2021 that analyzed the two main German parties (i.e., SPD and CDU/CSU) and aggregated the remaining parties into a single variable.

-

4. Jérôme, Jérôme, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Jérôme, Jérôme and Lewis-Beck2025) update their political-economy model—which has undergone several revisions since its inception in 1998—to reflect the evolving nature of electoral competition in Germany. This led to a gradual shift from a single equation focused on the incumbent to a seemingly unrelated regression model beginning in 2013. For five of the past seven elections, this model successfully predicted the political leanings of the future chancellor, although it failed in 2002 and 2021. In 2021, the model failed to predict the SPD’s unexpected victory. One potential explanation is that the model did not account for the popularity of the main opposition party relative to the outgoing chancellor’s party, as well as the growing electoral influence of the AfD. The authors integrated these two factors into their 2025 model.

Most of the models, regardless of their approach, provide vote-share forecasts, but not all of them provide estimates of seat allocations for the parties involved. Zweitstimme and Jérôme, Jérôme, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Jérôme, Jérôme and Lewis-Beck2025) both provide forecasts for votes and seats across all political parties, whereas Quinlan, Schnaudt, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Quinlan, Schnaudt and Lewis-Beck2025) forecast votes and seats for only the CDU/CSU and SPD, grouping the other parties together. Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier (Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2025) forecast votes exclusively for the CDU/CSU.

FORECAST ACCURACY

Table 1 presents an overview of the model forecasts and their corresponding errors for predicting each party’s vote share. Forecasts from all models were available for only one party (i.e., the CDU/CSU). Notably, all but one forecast overestimate the strength of the CDU/CSU; the exception was Quinlan, Schnaudt, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Quinlan, Schnaudt and Lewis-Beck2025), who underestimate the party’s vote share by 2.6 points. Across forecasts, absolute errors for predicting the CDU/CSU vote share range from 0.6 to 4.9 percentage points.

For the SPD, forecasts from four models were available, with Zweitstimme and the PollyVote providing relatively accurate forecasts; Jérôme, Jérôme, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Jérôme, Jérôme and Lewis-Beck2025) and Quinlan, Schnaudt, and Lewis-Beck (Reference Quinlan, Schnaudt and Lewis-Beck2025) were substantially off the mark.

Only two models, the PollyVote and Zweitstimme, provide forecasts for each of the seven parties listed in table 1 and all other parties combined. There are differences in both models’ accuracy when predicting individual parties; however, their mean absolute error across parties is almost identical: the PollyVote is missing by 1.3 percentage points compared to 1.4 percentage points for Zweitstimme.

In summary, the forecasting models for the 2025 German federal election are largely successful in anticipating the main electoral trends—an improvement over their 2021 performance. Traditional structural models, valued for their theoretical grounding and explanatory power, continue to provide important insights into the drivers of electoral outcomes. However, those that rely primarily on long-standing fundamentals (e.g., the incumbent’s popularity and macroeconomic indicators) struggled to account for the full complexity of the 2025 result, particularly the performance of the outgoing chancellor’s party. In an increasingly fluid political environment—marked by new party formations and shifting alliances under proportional representation—the adequacy of these fundamentals for forecasting election outcomes is a question for future research. More adaptive models such as Zweitstimme, which combine structural variables with real-time opinion data, and aggregators such as the PollyVote, which average across different forecasting approaches, delivered more accurate results in this election. Although foundational models remain appealing for their interpretability, forecasting accuracy remains an important criterion. Symposia such as those hosted by PS: Political Science & Politics are essential for benchmarking progress and encouraging innovation in the field.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NHKBP8.