Introduction

A long‐standing literature in political science demonstrates the corrosive effects of corruption on trust in democratic institutions (e.g., Andersen & Tverdova, Reference Andersen and Tverdova2003; Ares & Hernández, Reference Ares and Hernández2017; Bowler & Karp, Reference Bowler and Karp2004; Chang & Chu, Reference Chang and Chu2006; Chanley et al., Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Mishler & Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001; Van der Meer & Hakhverdian, Reference Van der Meer and Hakhverdian2017). Maintaining a democratic political system requires that voters are attentive to political malpractice and able as well as willing to ‘throw the rascals out’ (see Miller, Reference Miller1974). While there is strong evidence in favour of such democratic punishment effects, it has also been shown that several contextual factors, such as prevalent grand corruption among elites, voters' political sophistication or partisanship, can undermine political accountability for corruption scandals (e.g., Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013; Bauhr & Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2018; Breitenstein, Reference Breitenstein2019; Hakhverdian & Mayne, Reference Hakhverdian and Mayne2012; Klašnja, Reference Klašnja2017; Solaz et al., Reference Solaz, De Vries and De Geus2019). For instance, Bauhr and Charron (Reference Bauhr and Charron2018) show that citizens living in countries characterised by high levels of grand corruption tend to be less likely to hold corrupt politicians accountable, who can rely on a broad network of insiders benefiting from the corrupted system. Furthermore, partisans often tend to be more tolerant towards corruption when their own party is involved in the scandal (e.g., Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013). Corruption, therefore, is not automatically translated into popular punishment.

Democratic accountability mechanisms can also be substantially weakened in political systems that lack transparency and suffer from low popular mobilisation (see Bauhr & Grimes, Reference Bauhr and Grimes2014). In this regard, the European Union (EU) is often portrayed as a prime case of such a regime, with its democratic procedures being frequently described as too removed from its citizens to foster meaningful popular involvement (Follesdal & Hix, Reference Follesdal and Hix2006; Hix, Reference Hix2008). Moreover, the second‐order nature of European elections (Hix & Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2007, Reference Hix and Marsh2011) and the institutional complexity of EU politics in general (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014) provide further evidence in favour of a ‘democratic deficit’ in the EU (but see, Majone, Reference Majone1998; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik2002). Compared with national politics, public scrutiny of EU politics is thus often regarded as weaker. In this sense, political scandals in EU institutions might simply be ‘out of sight’ for citizens, hindering effective accountability via electoral participation.

Besides electoral institutions, accountability can also be brought about by other mechanisms. In particular, studies of democratic systems in Latin America have pointed to alternative channels of political accountability, such as monitoring and transparency measures by civil society organisations (Smulovitz & Peruzzotti, Reference Smulovitz and Peruzzotti2000). Similar arguments have been made regarding the role of civil society involvement for the EU's political legitimacy (Kohler‐Koch, Reference Kohler‐Koch2010). This ‘societal accountability’ can serve as an additional source of political control by representing, informing and mobilising citizens via civil society actors. However, increased civil society engagement does not automatically lead to more democratic mobilisation. More information about political malpractice can also foster resignation, leading to political demobilisation (Bauhr & Grimes, Reference Bauhr and Grimes2014). Therefore, having political malpractice ‘being in sight’ does not necessarily improve democratic accountability but can further erode institutional support.

While existing research on corruption and political accountability is divided on whether the uncovering of political malpractice results in electoral punishment or resignation, it agrees that public attentiveness is a minimal requirement for electoral and societal accountability mechanisms to work. Put differently, public attentiveness is a necessary condition for political accountability, as it can lead voters to punish politicians for malpractice via electoral and societal processes. Yet, public attentiveness is not a sufficient condition for accountability, as increased attentiveness to corruption can also lead to resignation.

In this research note, we investigate whether the EU's complex political regime fulfils this necessary condition for political accountability, presenting novel causal evidence from a recent corruption scandal. Research on the effects of corruption on public opinion in the EU is scarce, even though it potentially carries important implications for the state of democracy in the EU. One notable exception is a survey‐based panel study by Van Elsas et al. (Reference Van Elsas, Brosius, Marquart and De Vreese2020), who find that knowledge of and media exposure to the 2018 ‘Selmayr Affair’ depresses trust in EU institutions. Furthermore, analysing the impact of the 2011 ‘Cash for Influence’ scandal in the European Parliament (EP), De Vries (Reference De Vries2018) shows that Cypriot citizens decreased their trust in the EP as a reaction to the scandal. Against the backdrop of this scant literature, more (ideally causal) evidence is necessary to further investigate the consequences of corruption scandals for EU politics. In this regard, we shed light on some of the specific complexities emerging from political accountability structures in the EU's political system. More specifically, this note addresses questions about transnational accountability, as members of the EP (MEPs) should represent the interests of all EU citizens, but are elected in their respective national political arenas. It, therefore, remains unclear, whether, for example, French citizens react to a corruption scandal involving an Italian MEP.

Empirically, we provide evidence about the effect of the so‐called Qatargate corruption scandal among Greek and Italian MEPs on trust in the EP within the French and German electorates. We conceptualise EP trust as an indicator of EU regime support (see De Vries, Reference De Vries2018) and thereby cover a case of political malpractice at the heart of EU democracy, for which previous studies would expect a negative effect (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018; Van Elsas et al., Reference Van Elsas, Brosius, Marquart and De Vreese2020). Yet, neither such a negative effect nor its implications are obvious. The scandal's transnational nature, its potentially restricted effects among highly informed voters (Van Elsas et al., Reference Van Elsas, Brosius, Marquart and De Vreese2020), as well as the remoteness of EU institutions call a strong public reaction into question. Moreover, pre‐existing scepticism towards EU intuitions, especially in EU member states with well‐performing institutions (see Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Torcal and Bonet2011), could lead to a situation in which new information about corruption is already priced‐in in citizens' EU regime evaluations.

On 9 December 2022, Belgian police raided various addresses in and around Brussels, executed several arrests and seized more than half a million Euros in cash. Allegations concern MEPs, including then Vice‐President of the EP Eva Kaili, accepting bribes from Qatari government officials to influence their stance on Qatar's labour reforms ahead of the 2022 FIFA World Cup.Footnote 1 To this date, investigations are still ongoing, however, Qatargate has been dubbed as one of the most serious corruption scandals in the history of the EU.Footnote 2

We analyse Qatargate's public opinion effects by leveraging an ‘Unexpected Event during Survey Design’ (UESD) identification strategy (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020), as news about the scandal broke in December 2022 during the fieldwork period of two surveys we conducted in France and Germany. Estimating the effect of Qatargate on French and German citizens' trust in the EP, our UESD reveals a sizeable negative effect. This negative effect of Qatargate on EP trust is present in both countries and across different education groups, underlining how broadly the scandal reverberated in popular evaluations.

In this regard, our findings provide causal evidence that citizens react to the corruption scandal by adjusting their EU regime evaluations. This suggests that a necessary condition for EU accountability – public attentiveness – is given. The implications of this finding for political accountability in the EU are open to two alternative interpretations and depend on various contextual factors that require further research. On the one hand, increased attentiveness can point towards a working accountability mechanism, in which voters might be willing to punish MEPs, and MEPs would be cautious not to risk falling in disgrace with their constituents. Swift action by the EP in the aftermath of the Qatargate scandal to improve lobbying and transparency rules within the EP provides indicative evidence that a majority of MEPs saw a need to signal accountability by initiating reforms.Footnote 3 In this view, the EP as a whole responds to the scandal, also to address the negative public backlash observed in our data, and voters would vote out politicians that did not show accountability at the next election. This should ensure accountability and – in the long run – also popular support.

On the other hand, this negative effect could be an indication of resignation in the electorate, which could lead to a demobilisation of voters, which – in turn – favours the continuous presence of corrupt politicians due to a lack of electoral punishment. We want to underline that this reading of our finding is highly context dependent, as resignation requires a substantial level of grand corruption around voters (Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2018). In this regard, resignation might be a more plausible scenario in EU member states with higher levels of corruption than commonly perceived among French and German voters.Footnote 4 Put differently, the resignation interpretation of our findings is more likely to apply to other country contexts than the ones studied in this paper. This also highlights an important scope condition for the more optimistic interpretation of our finding and for our study as a whole.

Research design

To investigate the effect of the Qatargate corruption scandal on trust in the EP, we exploit the fact that the first news about the scandal broke during the fieldwork of two surveys we conducted in France and Germany. Data were collected between 29 November and 20 December 2022 via an online access panel managed by the survey company Bilendi. Respondents were sampled according to nationally representative quotas of age, gender, education and NUTS‐2 region.Footnote 5

Following Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020), we employ an UESD identification strategy, comparing respondents that were interviewed before the news about the Qatargate scandal broke (control group) with those that were interviewed afterwards (treatment group). Since allegations of misconduct in the EP were first reported on 9 December 2022, our treatment indicator is equal to 0 for all respondents interviewed before 9 December 2022, and 1 for all respondents interviewed after that date.Footnote 6 We measure trust in the EP using a standard survey item asking respondents how much they personally trust the EP, ranging from 0 = (‘no trust at all') to 10 = (‘complete trust').Footnote 7 We rely on a simple ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator, regressing the EP trust variable on our treatment indicator. As a robustness check, we also employ a Kernel Regularised Least Squares (KRLS) estimator (Hainmueller & Hazlett, Reference Hainmueller and Hazlett2014) as a non‐parametric alternative to account for possible non‐linearities in our data, especially with respect to time trends.Footnote 8

For the UESD to yield an unbiased estimate of Qatargate's causal effect on citizens’ trust in the EP, two key assumptions need to be satisfied. First, any differences in EP trust between treatment and control group have to be the result of the event in question and cannot be the consequence of another simultaneously occurring event (i.e., excludability). Second, the time at which a respondent is interviewed should be independent from the time at which the given event has occurred (i.e., temporal ignorability).

To meet these assumptions, it is crucial that respondents were not able to anticipate the event. In our case, the breaking of the Qatargate corruption scandal was connected to Belgian police acting on a secret investigation opened in July 2022.Footnote 9Police activity relating to corruption allegations in the EP became public on 9 December 2022 when the raids were executed. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that respondents were unaware of the event before 9 December 2022.

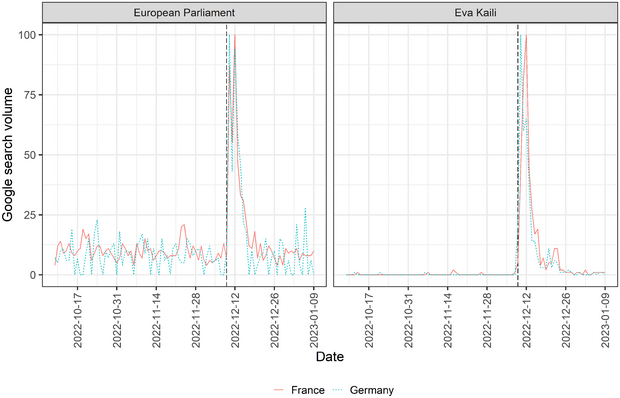

It also seems reasonable to assume that Qatargate was salient to our respondents. Figure 1 presents Google Trends data showing the search volume for the terms ‘European Parliament’ (left panel) and ‘Eva Kaili’ (right panel) for France and Germany between 9 October 2022 and 9 January 2023.Footnote 10 Each value represents the search interest on a given day relative to the highest point on the chart for the given country and time. A value of 100 means that the term is at the peak of its popularity, a value of 50 means that it is half as popular and a value of 0 means that there is no sufficient data for the given date. Clearly, Qatargate was a salient event. After 9 December 2022, searches for ‘European Parliament’ and ‘Eva Kaili’ increased significantly in both France and Germany. While we cannot preclude that some respondents had not heard of Qatargate when they were interviewed, it is likely that a sufficient number of respondents in our data had been exposed to the treatment.

Figure 1. Google trends data in France and Germany for ‘European Parliament’ and ‘Eva Kaili’ searches, 9 October 2022–9 January 2023.

Note: Each data point represents the search interest of a given term on a given day. A value of 100 means that the term is at the peak of its popularity, while a score of 50 means that it is only half as popular. Data points with a value of 0 denote days with no sufficient data. The data points in the left panel denote the popularity of the search term ‘Parlement européen’ in France and ‘Europaparlament’ in Germany relative to the highest point on the chart for the given country and time. The data points in the right panel show the popularity of the search term ‘Eva Kaili’ in France and Germany also relative to the highest point on the chart for the given country and time. For the term ‘Eva Kaili’, 17 observations in Germany and four observations in France which were coded as

![]() $<$1 in the Google trends data were re‐coded as 0. The dashed lines indicate 9 December 2022, the date when the first news about the Qatargate corruption scandal broke. Data were accessed in July 2023.

$<$1 in the Google trends data were re‐coded as 0. The dashed lines indicate 9 December 2022, the date when the first news about the Qatargate corruption scandal broke. Data were accessed in July 2023.

At a similar moment in time to Qatargate, another scandal concerning European politics became public. On 8 December 2022, a team of European journalists, including the French newspaper Le Monde Footnote 11 and the German news magazine Der Spiegel Footnote 12, uncovered illegal practices of the EU‐agency Frontex on the EU's external border. Frontex is an independent EU agency and, therefore, not directly connected to the EP. Yet, negative reporting on the agency's activities could result in declining support for the EU in general and by way of that influence citizens’ trust in the EP. In this case, the exclusion restriction would be violated. However, as we show in Figure A.2 in the Online Appendix, the scandal involving Frontex was much less salient than Qatargate. Based on this, it seems unlikely that the effects we attribute to Qatargate simply mask the effects of the Frontex scandal. The strong rise in attention for the search term ‘Eva Kaili’ also clearly demonstrates the heightened popular attention to the specificities of the Qatargate scandal.

Another violation of the exclusion restriction might relate to other pre‐existing time trends in our outcome variable. In this scenario, the treatment effects estimated might simply be driven by other time‐varying variables that are also related to the outcome, besides the event itself. Following Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020), we test for this possibility by estimating placebo treatment effects left of the cutoff point using the empirical median of the control group as a new cutoff (i.e., 6 December 2022). This means that the placebo treatment variable takes 0 for those interviewed on 29 and 30 November and a value of 1 for those interviewed on 7 December and 8 December 2022. We find no statistically significant effect of this placebo treatment. Furthermore, during the pre‐event period, there also seems to be no relationship between the timing of the interview and trust in the EP. Results of both robustness checks can be found in Tables A.4 and A.5 and Figure A.3 in the Online Appendix. Both of these robustness checks increase our confidence that the results reported are not driven by pre‐existing time trends. Furthermore, our 17 days fieldwork period was rather short, which makes pre‐existing time trends less of a concern (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020).Footnote 13

Besides these robustness checks, we also conduct balance tests to investigate if there are statistically significant differences between treatment and control groups in our data. The results reported in Table A.8 in the Online Appendix show that individuals interviewed after 9 December 2022 are somewhat younger and less educated than respondents who were interviewed before this date. Figure A.4 in the Online Appendix also reveals some imbalances concerning a number of regions in both France and Germany. To account for these imbalances, we control for age and education and include region fixed effects at the NUTS‐2 level in our models.Footnote 14

Results

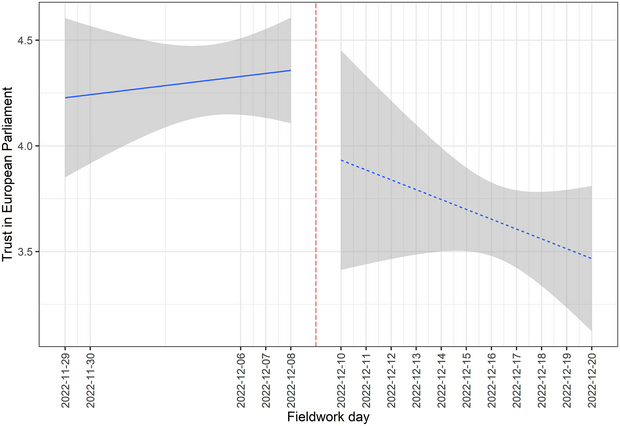

Did the Qatargate corruption scandal decrease EP trust in French and German electorates? Figure 2 presents a visual description of the discontinuous shift in EP trust over the fieldwork period of our surveys in France and Germany. The linear trends indicate that trust in the EP fell sharply after the Qatargate scandal became public on 9 December 2022. Following this date, trust in the EP continuously declined further.

Figure 2. Linear fit of survey fieldwork days on trust in the European Parliament, before and after 9 December 2022.

Note: The shaded area denotes a 95 per cent confidence interval. The dashed red line indicates 9 December 2022, the date when the first news about the Qatargate scandal broke.

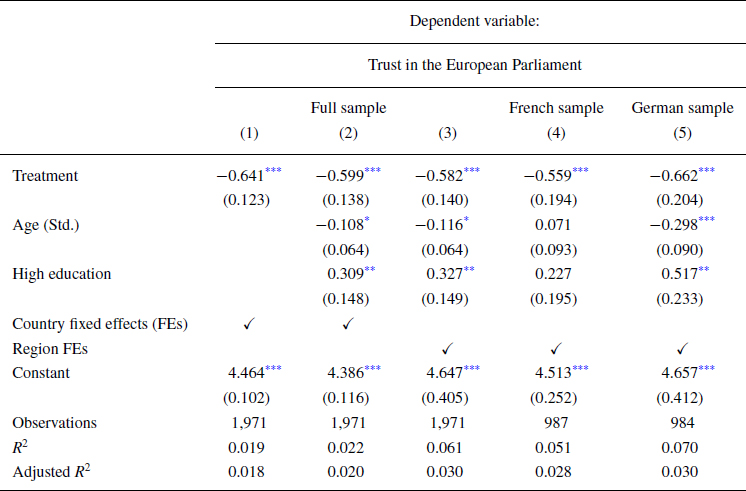

Table 1 presents the results of the main UESD analysis. Our baseline model (Model 1) shows a negative and statistically significant (p

![]() $\nobreakspace <\nobreakspace $0.01) effect of Qatargate on trust in the EP. On average, respondents who were interviewed after 9 December 2022 have about 0.64 points less trust in the EP than respondents who were interviewed before this date. This effect corresponds to approximately one‐fourth of a standard deviation in the EP trust variable and remains robust when we control for age as well as education (Model 2) and add region fixed effects to the model (Model 3). Furthermore, when looking at the French (Model 4) and German (Model 5) sub‐samples separately, Qatargate had a negative effect on trust in the EP in both countries. While EP trust declined somewhat stronger in Germany than in France, the corrosive effect of the scandal seems to be rather symmetric.

$\nobreakspace <\nobreakspace $0.01) effect of Qatargate on trust in the EP. On average, respondents who were interviewed after 9 December 2022 have about 0.64 points less trust in the EP than respondents who were interviewed before this date. This effect corresponds to approximately one‐fourth of a standard deviation in the EP trust variable and remains robust when we control for age as well as education (Model 2) and add region fixed effects to the model (Model 3). Furthermore, when looking at the French (Model 4) and German (Model 5) sub‐samples separately, Qatargate had a negative effect on trust in the EP in both countries. While EP trust declined somewhat stronger in Germany than in France, the corrosive effect of the scandal seems to be rather symmetric.

Table 1. OLS regression results of trust in the European Parliament on treatment.

Abbreviation: FEs, fixed effects.

![]() $^{*}$

p

$^{*}$

p

![]() $<$0.1;

$<$0.1;

![]() $^{**}$p

$^{**}$p

![]() $<$0.05;

$<$0.05;

![]() $^{***}$p

$^{***}$p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

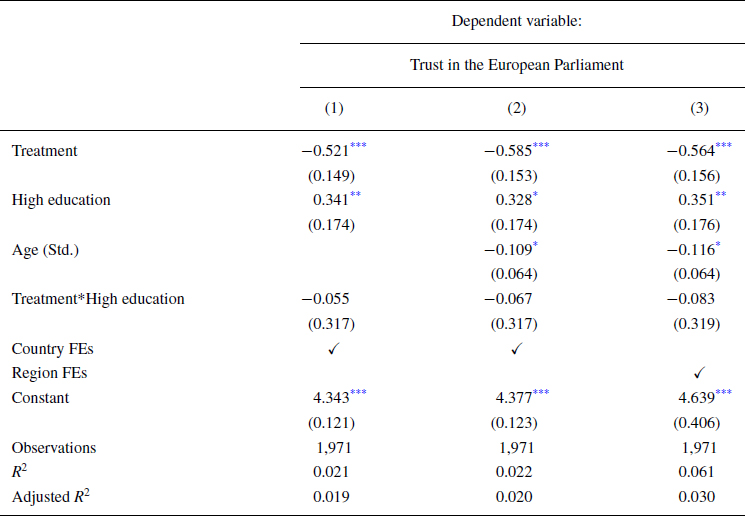

Furthermore, the negative effect of Qatargate on trust in the EP does not seem to differ by level of education. Table 2 presents UESD regression results where the treatment indicator is interacted with a dummy variable indicating respondents' level of high or low education. Respondents are coded as highly educated if they have completed a degree of higher education at a university or a similar institution. Regardless of the model specification, none of the interaction terms reach conventional levels of statistical significance. In this sense, Qatargate appears to have decreased trust in the EP for individuals with high and low levels of education alike. Importantly, this contrasts with studies finding that the corrosive effects of corruption on trust increase with higher levels of education (Hakhverdian & Mayne, Reference Hakhverdian and Mayne2012) and political sophistication (Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013).

Table 2. OLS regression results of trust in the European Parliament on treatment, conditional on education.

Abbreviation: FEs, fixed effects.

![]() $^{*}$

p

$^{*}$

p

![]() $<$0.1;

$<$0.1;

![]() $^{**}$p

$^{**}$p

![]() $<$0.05;

$<$0.05;

![]() $^{***}$p

$^{***}$p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

In summary, our findings have a number of important implications in light of existing debates about EU democracy and political accountability. First, we show that Qatargate, as a salient corruption event surrounding the EP, has an immediate effect on EU public opinion, as we would expect in democratic political systems. Since our research design rests on a sharp daily cutoff, we want to underline the apparent swift channelling of political events in Brussels into national political arenas. Our findings demonstrate that relevant political events from the EU level appear to be quickly communicated to the national contexts covered in this study.

Moreover, our findings reveal that EU politics appears to fulfil an important necessary condition for political accountability – public attentiveness. The transnational nature of the scandal also suggests that EU citizens do not only care about their own country's MEPs but are also concerned about the EU's quality of government more generally. French and German citizens reacting to misconduct by Greek and Italian MEPs point towards the presence of at least some form of transnational accountability.

Discussion

Citizens' ability to hold corrupt politicians accountable for misconduct is a cornerstone of democratic political systems. However, in particular in the EU, societal and electoral accountability might be hard to achieve, as a basic requirement for political accountability – citizens' attentiveness to politicians' behaviour – might not be given. Hindered by a complicated institutional architecture (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014), complex democratic procedures and a lack of a common public sphere (Follesdal & Hix, Reference Follesdal and Hix2006; Hix, Reference Hix2008), accountability mechanisms are often argued to malfunction in the EU. In this regard, political scandals at the European level might simply be too removed for citizens to hold corrupt politicians accountable.

Yet, the findings of this study provide causal evidence for the presence of important minimal requirements for effective accountability mechanisms in the EU. Despite the inefficiencies and complications of the EU's democratic system, public opinion responds to political scandals in Brussels and citizens adjust their evaluations of the involved political institution accordingly.

The implications of this finding are open to alternative interpretations. On the one hand, attentiveness to the scandal can lead to electoral punishment, which – however – is complicated by the multi‐level EP electoral system that does not (yet) have EU‐wide party platforms and a joint supranational vote. Besides this, attentiveness to EU scandals can still support mechanisms of societal accountability, with civil society organisations increasing pressure on the EP to improve transparency. Indeed, the popular backlash detected in this study can support attempts of pushing the EP towards more transparency in its internal processes.

On the other hand, the negative backlash uncovered in this study can also point to a political resignation in the electorate, which could lead to a demobilisation of voters. This could enable the continuous presence of corrupt politicians due to a lack of electoral and/or societal punishment. Yet, resignation might be a more convincing interpretation for the persistence of corruption in highly corrupt contexts (Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2018), but less so for the more high‐quality governance contexts covered in our study.

Our study comes with some important limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we cannot track potential electoral consequences of the scandal with our research design and data at hand. Punishment at the ballot box is more complicated in the case of the EP compared to national politics, as citizens think less in terms of European party groups and more in terms of national parties and politicians (see Hix & Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011). Hence, it is likely that electoral accountability mechanisms for the EP do still mainly work within national political contexts (and not transnationally). This, at least, provides important ground for future research on the topic.

Second, due to our UESD's focus on causal identification, we cannot say anything about the long‐term consequences of corruption scandals for EU politics. However, given the negative effects documented in this and the few other existing studies (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018; Van Elsas et al., Reference Van Elsas, Brosius, Marquart and De Vreese2020), it appears that the EU risks losing public legitimacy under the continuous presence of corruption. There is a risk of asymmetric attention towards negative EU news (e.g., scandals). Combined with the more difficult paths towards political accountability in the EU, asymmetric attention to bad EU news could pose a serious challenge to the EU's public support in the long run. At least, a convincing political response would be required on the EU level to tackle the popular backlash in regime support after a scandal, as to prevent negative long‐term consequences.

Third, we have covered a rather prominent case of political malpractice in Brussels, using data from two of the EU's founding member states, which had none of their own politicians involved in the scandal. Future research should study more systematically how different country contexts (involved/not involved; high level of corruption/low levels of corruption) shape popular reactions to scandals in the EU.

Fourth, while our study offers the advantage of providing causal evidence on popular reactions to an EU scandal, it falls short of clearly establishing the mechanisms leading voters to become attentive to EU politics. Related to this, our UESD can ultimately not completely rule out that other alternative explanations may have caused the decrease in EP trust we observe. Yet, in light of the numerous robustness checks conducted, we are confident that the underlying assumptions of the UESD hold for the case at hand, making a causal effect of Qatargate on EP trust plausible. Following experimental research on mechanisms behind popular reactions to corruption within national politics (e.g., Anduiza et al., Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013), future research should investigate with similar designs how reactions to corruption work within EU politics. Moreover, it remains important to further study the transmission of EU politics through media channels as to improve our understanding of citizens' attentiveness to political processes.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments on a previous version of this paper, we are thankful to our colleagues at the Department of Politics and Society, Aalborg University. This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF Ambizione Grant: N° 186002).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure A.1 Number of completed interviews per fieldwork day.

Figure A.2 Google trend data in France and Germany for ‘European Parliament’ and ‘Frontex’ searches, 09 October 2022‐09 January 2023.

Figure A.3 Average trust in European Parliament by day in pre‐event period (0 = 08 December 2022).

Figure A.4 OLS regression results of region on treatment.

Table A.1 Summary statistics of sample.

Table A.2 Details on measurement of variables.

Table A.3 KRLS regression results of trust in European Parliament on treatment (average marginal effects).

Table A.4 OLS regression results of trust in European Parliament on placebo treatment.

Table A.5 OLS regression results of trust in European Parliament on fieldwork days (pre‐event period).

Table A.6 OLS regression results of placebo test for left‐right ideology on treatment.

Table A.7 KRLS regression results of placebo test for left‐right ideology on treatment (average marginal effects).

Table A.8 OLS regression results of socio‐demographics on treatment.

Table A.9 OLS regression results of trust in EP on treatment (entropy balancing weights).

Table A.10 OLS regression results of trust in EP on treatment conditional on education (entropy balancing).

Data S1

<

<