5.1 Introduction

After the successful adoption of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2014, investment facilitation has been gaining in popularity. Investment facilitation can be generally defined as a set of measures for improving the transparency and predictability of investment frameworks, streamlining procedures related to foreign investors, and enhancing coordination and cooperation between different stakeholders.Footnote 1 An Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement was first suggested by a group of experts in 2015.Footnote 2 After three years of structured discussions on investment facilitation for development (2018–2020), the formal negotiations on a multilateral agreement started in September 2020 among more than 100 members of the WTO.Footnote 3 An important component of the negotiations is an assessment of impacts, so members can rationalize their participation. Quantifying the impacts of the IFD Agreement is, at the outset, challenging. Despite the dynamic debate on investment facilitation, there is no generally accepted clear definition of the concept. Investment facilitation covers a wide range of areas with the focus on allowing investment to flow efficiently and for the greatest benefit. Transparency, simplicity, and predictability are among its most important principles. Moreover, investment facilitation refers to actions taken by governments designed to attract foreign investment and maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of its administration through all stages of the investment cycle. It does not, however, incorporate investment liberalization and protection, or investor–state dispute settlement. These issues remain a subject of bilateral and regional investment agreements.Footnote 4

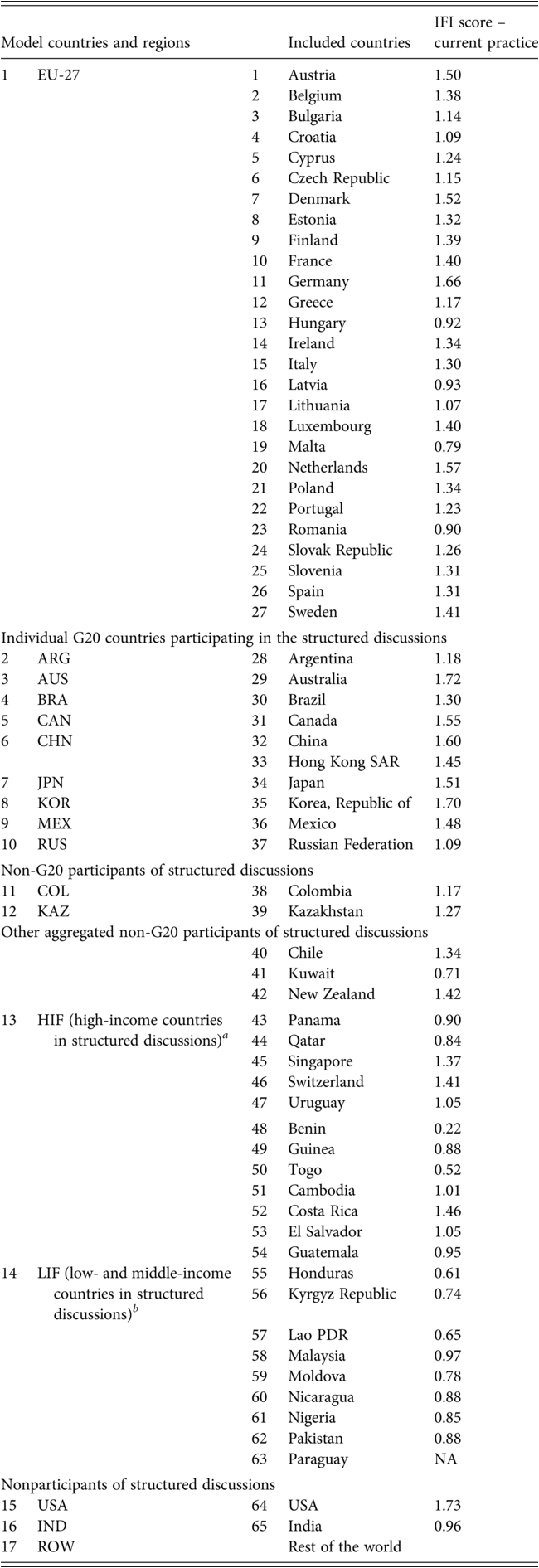

In this chapter, we use an economic model of global interactions to quantify the value of the IFD Agreement, given the outcomes of the structured discussions. The model is calibrated to GTAP 10 data characterizing trade and the social accounts. We aggregate the world into seventeen regions, including over sixty countries that participated in the structured discussions. We consider the possible IFD scenarios based on the Investment Facilitation Index (IFI) developed by Berger, Dadkhah, and OlekseyukFootnote 5 and Berger and Olekseyuk.Footnote 6 The IFI helps to conceptualize the scope of investment facilitation along 6 policy areas and 117 individual measures and provides an indication of the level of current practice in investment facilitation across a large number of countries. It clearly illustrates that there are significant variations across countries and considerable gaps between the current practices of many countries as well as what might be considered best practice. The IFI score ranges from a low of 0.23 for Benin to a high of 1.73 for the United States (with an upper bound of 2.00). It is especially true that low- and middle-income countries would gain from implementing investment facilitation provisions. We use the IFI in this chapter to inform the quantitative level of the implied reduction of FDI barriers embodied in the IFD. While the absolute scale of the implied liberalization is uncertain, we leverage the IFI to establish a sound measure of the relative shocks across countries and regions. With the shocks specified, we use the economic model to establish plausible ranges for IFD benefits. The primary measure of the value of an IFD to different regions is reported from the model in terms of changes in economic welfare.Footnote 7 We demonstrate the model’s operation as a tool for informing the policy debate, but we also warn that the model is sensitive to a set of critical assumptions. A continuation of the empirical research necessary to inform these assumptions is warranted.

To our knowledge, we are on the forefront of empirically quantifying the potential effects of the specific provisions of an IFD. Thus, we provide important and timely information at the point of policy formation. Our work provides results on the economic impact of a potential IFD on the most active countries during the structured discussions including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Russia, South Korea, and EU-27. Other countries involved in the structured discussions within the WTO are aggregated into either the High-income Investment Facilitation (HIF) region or the Low- and middle-income Investment Facilitation (LIF) regions. Apart from members of the structured discussions, we also include the United States and India, major countries that are not participating in the WTO negotiations.Footnote 8 At this level of geographic resolution, our country sample covers around 90 percent of world FDI stocks, with the rest of the countries aggregated into the rest of the world (ROW) aggregate region.

This chapter proceeds as follows. In Section 5.2, we describe the underlying data sources and the applied model of global trade. In Section 5.3, we outline the specific model scenarios and the implementation of the IFI-based shocks. Section 5.4 provides a set of results for all included countries and regions. In Section 5.5, we enumerate a set of critical ad hoc assumptions, and Section 5.6 illustrates the model’s sensitivity to our structural and parametric assumptions. Finally, in Section 5.7, we provide concluding comments and highlight follow-up research that would increase the precision of future quantitative measures of the value of investment facilitation.

5.2 Data and Model Description

The widely adopted Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) methodology provides valuable insights from policy reforms in different areas such as taxation, migration, trade and investment, development policy, climate change, carbon trading, food security, and anti-poverty policies. It is a standard tool of empirical analysis, which is broadly used for policy evaluation and advice. The method is able to capture economy-wide responses to proposed policy shocks. This approach allows for complex interactions of productivity differences at the country, sector, and factor levels, while accounting for shifts in demand as incomes change. International markets are impacted by changes in comparative advantage, trade flows, market entry, and resource reallocations following trade and FDI liberalization. CGE models simultaneously account for interactions among producers, households, and governments in multiple product markets and across several countries and regions of the world.

To quantify the impact of the IFD Agreement, we develop an innovative multiregion general equilibrium simulation or CGE model with four sectors (agriculture, manufacturing, services, and energy) and seventeen regions covering over sxity countries participating in the official negotiations (see Table 5.1 for country coverage and aggregation). The model extends the basic GTAPinGAMS structure presented by Lanz and RutherfordFootnote 9 calibrated to Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) 10 data characterizing bilateral trade and the social accounts.Footnote 10 Extensions include a consideration of FDI and imperfect competition in a multiregion setting following the model developed by Balistreri, Tarr, and Yonezawa.Footnote 11 Unlike that study, our model includes the ability to consider FDI in goods in addition to business services. For this purpose, we compute bilateral shares of foreign affiliate sales for model-specific sectors and regions using the data from Fukui and LakatosFootnote 12 and the GTAP 9 data for 2007.Footnote 13 Given the shares, we distinguish between goods and services supplied either by domestic firms or by foreign firms both operating in the host country (FDI case) and abroad (cross-border supply).

| Model countries and regions | Included countries | IFI score – current practice | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EU-27 | 1 | Austria | 1.50 |

| 2 | Belgium | 1.38 | ||

| 3 | Bulgaria | 1.14 | ||

| 4 | Croatia | 1.09 | ||

| 5 | Cyprus | 1.24 | ||

| 6 | Czech Republic | 1.15 | ||

| 7 | Denmark | 1.52 | ||

| 8 | Estonia | 1.32 | ||

| 9 | Finland | 1.39 | ||

| 10 | France | 1.40 | ||

| 11 | Germany | 1.66 | ||

| 12 | Greece | 1.17 | ||

| 13 | Hungary | 0.92 | ||

| 14 | Ireland | 1.34 | ||

| 15 | Italy | 1.30 | ||

| 16 | Latvia | 0.93 | ||

| 17 | Lithuania | 1.07 | ||

| 18 | Luxembourg | 1.40 | ||

| 19 | Malta | 0.79 | ||

| 20 | Netherlands | 1.57 | ||

| 21 | Poland | 1.34 | ||

| 22 | Portugal | 1.23 | ||

| 23 | Romania | 0.90 | ||

| 24 | Slovak Republic | 1.26 | ||

| 25 | Slovenia | 1.31 | ||

| 26 | Spain | 1.31 | ||

| 27 | Sweden | 1.41 | ||

| Individual G20 countries participating in the structured discussions | ||||

| 2 | ARG | 28 | Argentina | 1.18 |

| 3 | AUS | 29 | Australia | 1.72 |

| 4 | BRA | 30 | Brazil | 1.30 |

| 5 | CAN | 31 | Canada | 1.55 |

| 6 | CHN | 32 33 | China Hong Kong SAR | 1.60 1.45 |

| 7 | JPN | 34 | Japan | 1.51 |

| 8 | KOR | 35 | Korea, Republic of | 1.70 |

| 9 | MEX | 36 | Mexico | 1.48 |

| 10 | RUS | 37 | Russian Federation | 1.09 |

| Non-G20 participants of structured discussions | ||||

| 11 | COL | 38 | Colombia | 1.17 |

| 12 | KAZ | 39 | Kazakhstan | 1.27 |

| Other aggregated non-G20 participants of structured discussions | ||||

| 40 | Chile | 1.34 | ||

| 41 | Kuwait | 0.71 | ||

| 42 | New Zealand | 1.42 | ||

| 13 | HIF (high-income countries in structured discussions)Footnote a | 43 44 | Panama Qatar | 0.90 0.84 |

| 45 | Singapore | 1.37 | ||

| 46 | Switzerland | 1.41 | ||

| 47 | Uruguay | 1.05 | ||

| 48 | Benin | 0.22 | ||

| 49 | Guinea | 0.88 | ||

| 50 | Togo | 0.52 | ||

| 51 | Cambodia | 1.01 | ||

| 52 | Costa Rica | 1.46 | ||

| 53 | El Salvador | 1.05 | ||

| 54 | Guatemala | 0.95 | ||

| 14 | LIF (low- and middle-income countries in structured discussions)Footnote b | 55 56 | Honduras Kyrgyz Republic | 0.61 0.74 |

| 57 | Lao PDR | 0.65 | ||

| 58 | Malaysia | 0.97 | ||

| 59 | Moldova | 0.78 | ||

| 60 | Nicaragua | 0.88 | ||

| 61 | Nigeria | 0.85 | ||

| 62 | Pakistan | 0.88 | ||

| 63 | Paraguay | NA | ||

| Nonparticipants of structured discussions | ||||

| 15 | USA | 64 | USA | 1.73 |

16 17 | IND ROW | 65 | India Rest of the world | 0.96 |

Notes: This aggregation is based on the list of around seventy countries participated in structured discussions. The values for the IFI score are based on Berger, Dadkhah, and Olekseyuk (2021).

a Macao SAR is a non-G20 high-income country that took part in the structured discussions; however, it is not included in this region as it is not separately available in the GTAP database. This country is represented in the ROW region.

b This region does not include the following participants of the structured discussions: Liberia, Tajikistan, Montenegro, and Myanmar. These countries are not separately available in the GTAP database and constitute a part of the ROW region.

Given consistency of all other model features with the standard GTAPinGAMS formulation, we only document the extensions to the trade and FDI structures in this chapter.Footnote 14 In this section, we briefly describe the two model structures explored: ARM, the perfect-competition Armington structure; and BRF, a monopolistic competition structure of bilateral representative firms.Footnote 15

The agricultural (AGR) and energy (ENR) sectors are always modeled as perfectly competitive sectors with constant returns to scale (ARM). This standard modeling approach applies the Armington assumption of differentiated regional products to model foreign trade.Footnote 16 In this framework, firm-level products and technologies are assumed to be identical within a region, whereas product varieties from different places of production are imperfect substitutes. Thus, agents consume domestic and foreign varieties of the same good, which are aggregated to a composite commodity using the so-called Armington elasticity of substitution. The assumption of homogeneous firm-level goods within one region is realistic for agricultural and energy products, which are usually characterized by rather low shares of intra-industry trade (i.e., below 60 percent) and rather high elasticities of substitution between different varieties, meaning that products are closer substitutes.

In contrast to agriculture and energy sectors, manufacturing (MAN) and services (SER) are modeled as monopolistically competitive sectors with FDI (BRF). In this model framework, we differentiate all goods and services on the firm level. The first application of the bilateral representative firms structure in a multiregion trade model is provided by Balistreri, Böhringer, and Rutherford.Footnote 17 However, the authors do not consider FDI in their model specification. Thus, this is an important model extension necessary to investigate the effects of investment facilitation.

In general, contemporary trade models with monopolistic competition usually adopt either a KrugmanFootnote 18-style homogeneous firms structure or a MelitzFootnote 19-style heterogeneous firms structure. We consider a hybrid model that is computationally tractable like the relatively simple Krugman model but includes bilateral selection of firms and rents associated with each market like the Melitz formulation. In a typical Krugman formulation, firms enter based on their profit opportunities across all markets. In our formulation, Krugman-style firms choose to operate, or not, in each foreign market. That is, there is an entry margin for every market. This captures the bilateral selection feature of the Melitz structure. We achieve a stable equilibrium with bilateral entry (selection) by designating a portion of observed capital payments to a bilateral specific-factor earning rents. Thus, the input cost for firms is increasing and varies across markets. Each good or service that is modeled under monopolistic competition is assumed to be provided by a small firm selling a unique variety. We characterize supply on a given bilateral cross-border trade link or supply through bilaterally designated FDI as provided by a bilateral representative firm (BRF).

Under investment facilitation, FDI barriers in the form of reduced transaction costs are diminished and more FDI firms enter. Overall output goes up, and there are additional gains through the normal variety (extensive margin) channel. Consumers obtain access to new varieties unavailable before IFD implementation, and producers gain from a higher number of intermediate goods and services. The entry condition of a representative firm is bilateral and, therefore, different from a standard Krugman formulation. In a standard Krugman formulation, the fixed cost of establishing a variety (entry) would be assumed specific to a given source region, and this cost would be covered by profits across all host markets. Relative to a standard Krugman model, therefore, the BRF formulation generates bilateral extensive-margin responses (like the selection effect in Melitz). In addition, because there is a specific factor, changes in bilateral distortions are properly allocated to those favored firms in the markets where they operate. For a more detailed description of the BRF formulation in an application, see Balistreri, Böhringer, and Rutherford, and for an extended discussion of monopolistic competition in computational simulation models,Footnote 20 see Balistreri and Rutherford.Footnote 21

5.3 Investment Facilitation Scenarios

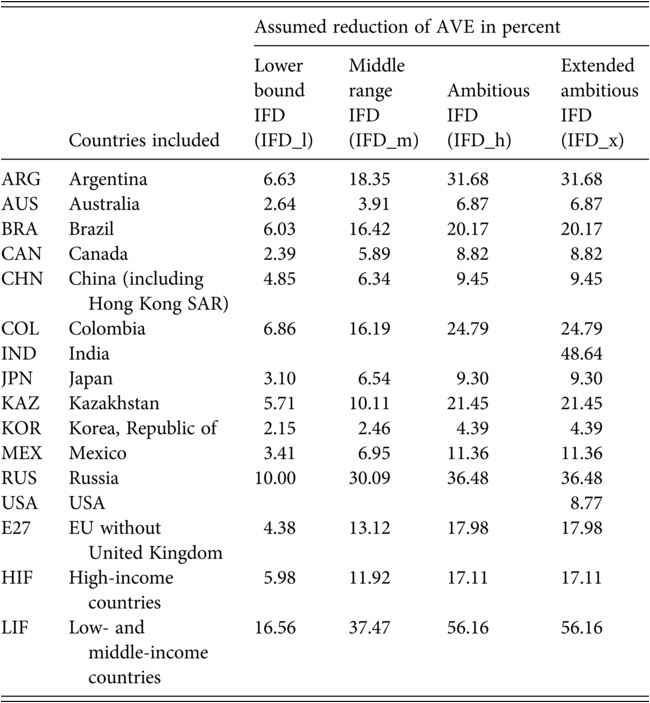

Following the detailed work on quantifying the current practice in investment facilitation as well as expected reforms due to an IFD Agreement by Berger, Dadkhah, and Olekseyuk,Footnote 22 we use the country-level improvements in the IFI induced by different frameworks of the IFD Agreement as an assumption for the relative reductions in ad valorem equivalents (AVEs) of nontariff barriers (NTBs). Using this at an assumed scale, we are able to simulate several scenarios representing different depths and country coverage of the potential multilateral investment facilitation deal. The detailed assumptions about reductions of the AVEs are illustrated in Table 5.2.Footnote 23

| Countries included | Assumed reduction of AVE in percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound IFD (IFD_l) | Middle range IFD (IFD_m) | Ambitious IFD (IFD_h) | Extended ambitious IFD (IFD_x) | ||

| ARG | Argentina | 6.63 | 18.35 | 31.68 | 31.68 |

| AUS | Australia | 2.64 | 3.91 | 6.87 | 6.87 |

| BRA | Brazil | 6.03 | 16.42 | 20.17 | 20.17 |

| CAN | Canada | 2.39 | 5.89 | 8.82 | 8.82 |

| CHN | China (including Hong Kong SAR) | 4.85 | 6.34 | 9.45 | 9.45 |

| COL | Colombia | 6.86 | 16.19 | 24.79 | 24.79 |

| IND | India | 48.64 | |||

| JPN | Japan | 3.10 | 6.54 | 9.30 | 9.30 |

| KAZ | Kazakhstan | 5.71 | 10.11 | 21.45 | 21.45 |

| KOR | Korea, Republic of | 2.15 | 2.46 | 4.39 | 4.39 |

| MEX | Mexico | 3.41 | 6.95 | 11.36 | 11.36 |

| RUS | Russia | 10.00 | 30.09 | 36.48 | 36.48 |

| USA | USA | 8.77 | |||

| E27 | EU without United Kingdom | 4.38 | 13.12 | 17.98 | 17.98 |

| HIF | High-income countries | 5.98 | 11.92 | 17.11 | 17.11 |

| LIF | Low- and middle-income countries | 16.56 | 37.47 | 56.16 | 56.16 |

Lower bound IFD (IFD_l): Investment facilitation measures are already, to some extent, included in different deep and comprehensive free trade agreements. Three recent FTAs, namely, The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (UMCA), are reviewed in the initial IFI development.Footnote 24 In the agreements’ text, they identify commitments regarding investment facilitation such as horizontal transparency provisions (dissemination of regulations affecting foreign investment), digital signature, and protection of confidential information. These are mapped to the IFI and provide the improvements of index scores in accordance to each agreement. The results illustrate that the highest increase in the IFI score arises in case of a CPTPP-like IFD Agreement. For our lower-bound scenario, we use the percentage change in the IFI score according to the CPTPP agreement. Moreover, we assume that investment facilitation commitments covered by the regional treaty are multilateralized, so we apply them to all model-specific countries and regions that participated in structural discussions. Thus, a lower bound IFD simulation covers only a limited number of measures from the detailed IFI and suggests the lowest policy shocks ranging from a reduction of FDI barriers by 2.15 percent in South Korea to the highest reduction by 16.56 percent in low- and middle-income countries.

Middle range IFD (OFDM): We assume that commitments under the IFD Agreement follow closely Brazil’s circulated proposal for a possible WTO Agreement on investment facilitation (the “Model Agreement”),Footnote 25 which covers over 30 percent of investment facilitation measures included in the IFI (e.g., single window, focal point, and transparency provisions). Again, we map Brazil’s proposal from February 2018 and provide the change in IFI scores compared to the current practice, which is used in the simulation. We apply this policy shock to all included countries, except for India and the United States. Table 5.2 shows that the lowest decline of AVE occurs again in South Korea (2.46 percent), while the highest reduction of FDI barriers is assumed for the low- and middle-income countries (37.47 percent). Hereby, South Korea, Germany, and Australia will have the least changes in their investment facilitation rules since they have already adopted most of the commitments covered by this scenario.

Ambitious IFD (IFD_h): Given several submitted proposals during the structured discussions (by Brazil, Argentina, Russia, China, Kazakhstan, MIKTA, and FIFD),Footnote 26 we assume that commitments under the IFD include all mentioned investment facilitation measures, which strongly increases the coverage of measures included in the IFI (almost 50 percent of all measures) and reflects a much deeper reform potential. Most of the proposals have similar commitments in terms of transparency, predictability, fees and charges, and electronic governance. However, focal point commitments suggested by Argentina and Brazil and outward investment provisions suggested by China provide value added to the other proposals. In terms of magnitude, due to the broad coverage of measures, this scenario assumes the highest reduction of FDI barriers from 4.39 percent in South Korea up to 56.16 percent for the low- and middle-income countries (LIF region). In general, the low-income countries will gain most from implementation of investment facilitation provisions due to the low level of current practice and, consequently, the highest improvement in their IFI scores.

Extended IFD including United States and India (IFD_x): In this scenario, we also apply the highest reduction of FDI barriers following the ambitious scenario but extend the country coverage to India and the United States. For the United States, the shock is quite small (8.77 percent) since its practice in cooperation and electronic governance is even more advanced than the expected investment facilitation commitments. Only for focal point, application process, and transparency provisions, the IFI developers find some improvements in the IFI score. For India, in contrast, the ambitious IFD scenario would lead to significant improvements across all policy areas, with the highest increase by almost 70 percent for application process provisions. India’s overall shock for the ambitious scenario equals to 48.64 percent, the highest reduction of FDI barriers among all separately included countries (only for the aggregate LIF region, the value is higher with 56.16 percent).

5.4 Results

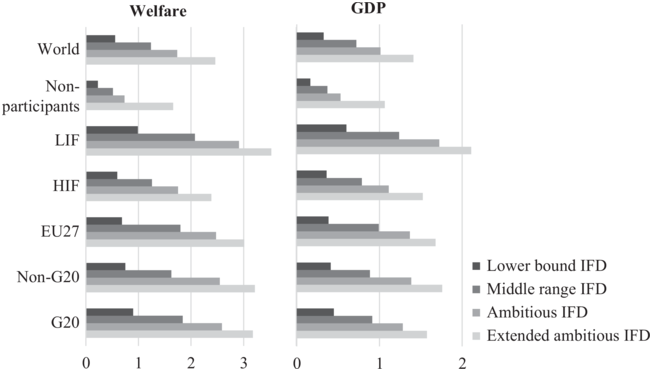

Conditional on the key assumptions, our model suggests significant gains from investment facilitation. Figure 5.1 reports the aggregated welfareFootnote 27 and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) impacts as percentage changes for the four scenarios. For the world as an aggregate, welfare increases range between 0.56 percent under the lower bound IFD and 1.74 percent under the ambitious scenario.Footnote 28 If India and the United States join the agreement, the potential gains would be even higher, with 2.46 percent. Consistently, the world GDP would also rise by 0.33 percent in case of lower bound IFD and over 1 percent in the ambitious scenarios (1.01 percent for IFD_h and 1.41 percent for IFD_x).

Figure 5.1 Aggregated regional welfare and GDP impact (percent).

Note: Table 5.1 provides country coverage for EU27, HIF, and LIF, which is identical with our model- specific regions. G20 covers all G20 countries involved in structured discussions (ARG, AUS, BRA, CAN, CHN, JPN, KOR, MEX, RUS). Non-G20 includes Columbia and Kazakhstan as participants of structured discussions. Nonparticipants include the United States, India, and the rest of the world.

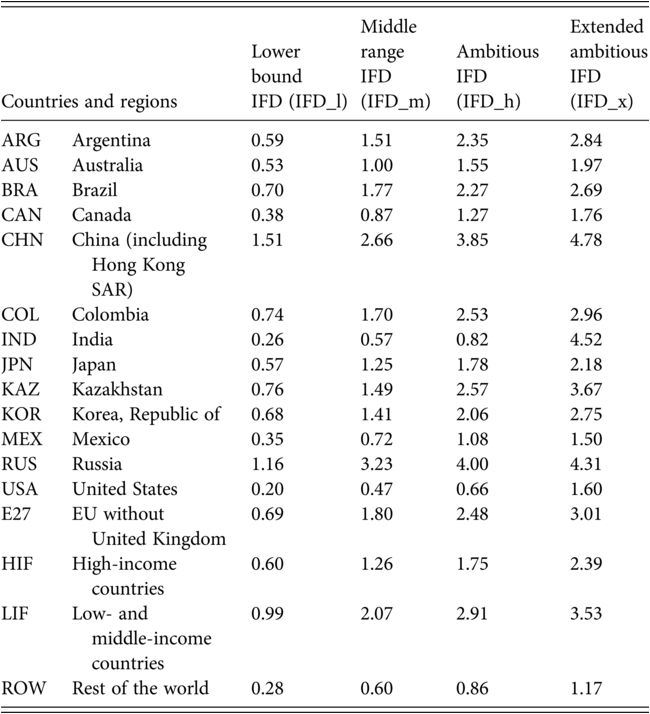

In general, the results illustrate that the broader the coverage of the IFD Agreement and the higher the applied shocks, the higher are the gains. The benefits are concentrated among the regions participating in the negotiations,Footnote 29 with the highest proportional increase in welfare realized by the low- and middle-income countries (LIF) across all scenarios (0.99 percent for IFD_l and 2.91 percent for IFD_h). The other participating regions show somewhat lower welfare increases: In the middle range simulation (IFD_m), the values range between 1.26 percent for high-income countries (HIF) and 1.84 percent for G20 countries participating in the structured discussions. For the ambitious IFD scenario (IFD_h), the respective values equal to 1.75 percent (HIF) and 2.59 percent (G20). There are notable spillovers from applied investment facilitation reforms that accrue to regions not involved in the structured discussions. Their average welfare gains amount to 0.23 percent in case of IFD_l simulation and increase up to 0.73 percent in the IFD_h scenario. However, joining the agreement is beneficial not only for outsiders but also for all participating regions since they are able to generate higher gains (by approximately 0.6 percentage points), with the extended number of members in the IFD_x scenario.

Table 5.3 reports the decomposition of the regional impacts for the individually modeled countries. We can see that China and Russia are the two countries gaining the most across all IFD scenarios. China’s welfare gains range between 1.51 percent in the lower bound simulation and 3.85 percent in case of ambitious IFD. Russia’s gains might be even higher, with 4 percent for the ambitious scenario, since this country starts with rather poor current practice, given the IFI score of 1.09. For the rest of individually included countries, the gains lie between 0.35 percent in Mexico (IFD_l) and 2.57 percent in Kazakhstan (IFD_h).

| Countries and regions | Lower bound IFD (IFD_l) | Middle range IFD (IFD_m) | Ambitious IFD (IFD_h) | Extended ambitious IFD (IFD_x) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARG | Argentina | 0.59 | 1.51 | 2.35 | 2.84 |

| AUS | Australia | 0.53 | 1.00 | 1.55 | 1.97 |

| BRA | Brazil | 0.70 | 1.77 | 2.27 | 2.69 |

| CAN | Canada | 0.38 | 0.87 | 1.27 | 1.76 |

| CHN | China (including Hong Kong SAR) | 1.51 | 2.66 | 3.85 | 4.78 |

| COL | Colombia | 0.74 | 1.70 | 2.53 | 2.96 |

| IND | India | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.82 | 4.52 |

| JPN | Japan | 0.57 | 1.25 | 1.78 | 2.18 |

| KAZ | Kazakhstan | 0.76 | 1.49 | 2.57 | 3.67 |

| KOR | Korea, Republic of | 0.68 | 1.41 | 2.06 | 2.75 |

| MEX | Mexico | 0.35 | 0.72 | 1.08 | 1.50 |

| RUS | Russia | 1.16 | 3.23 | 4.00 | 4.31 |

| USA | United States | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 1.60 |

| E27 | EU without United Kingdom | 0.69 | 1.80 | 2.48 | 3.01 |

| HIF | High-income countries | 0.60 | 1.26 | 1.75 | 2.39 |

| LIF | Low- and middle-income countries | 0.99 | 2.07 | 2.91 | 3.53 |

| ROW | Rest of the world | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 1.17 |

Of particular interest is the fact that India, as a notable absentee in the structured discussions, has a lot to gain from investment facilitation reforms. Solely spillover gains reach 0.26 percent or even 0.82 percent under the IFD_l and IFD_h scenarios, which is comparable to some participating countries like Mexico or Canada in case of the IFD_m scenario. If India joins the agreement, welfare gains would rise strongly, with 4.52 percent under the IFD_x scenario. The United States, in contrast, does not show such a dramatic increase from participation: it is only moving from a spillover gain of 0.20 percent or 0.66 percent under the IFD_l and IFD_h scenarios to a 1.60 percent gain under the IFD_x simulation.

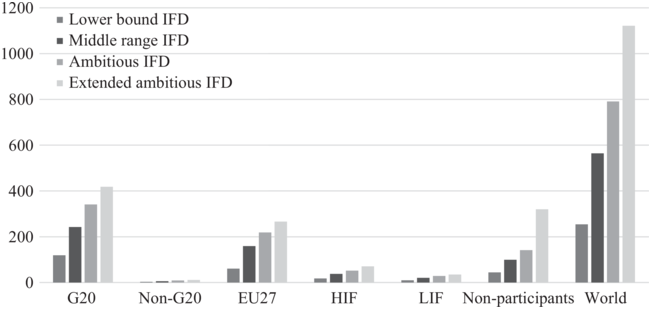

The reports of the percentage welfare changes are somewhat lower for larger developed regions (like the EU). This masks the value of an IFD Agreement in terms of dollars of benefits that accrue to these higher-income regions. Figure 5.2 reports the welfare increases in billions of dollars. We see that global welfare increases by more than US$250 billion under the lower bound scenario (IFD_l) and reaches more than US$1,120 billion in case of the extended ambitious IFD simulation. Hereby, substantial benefits accrue to the EU and other participating G20 countries. Participating G20 countries accrue 43–46 percent of the total global benefits across different IFD scenarios; for the EU, this share ranges between 24 percent (IFD_l) and 28 percent (IFD_m and IFD_h).

Figure 5.2 Aggregated regional welfare impact ($B).

Note: Table 5.1 provides country coverage for EU27, HIF, and LIF, which is identical with our model- specific regions. G20 covers all G20 countries involved in structured discussions (ARG, AUS, BRA, CAN, CHN, JPN, KOR, MEX, RUS). Non-G20 includes Columbia and Kazakhstan as participants of structured discussions. Nonparticipants include the United States, India, and the rest of the world.

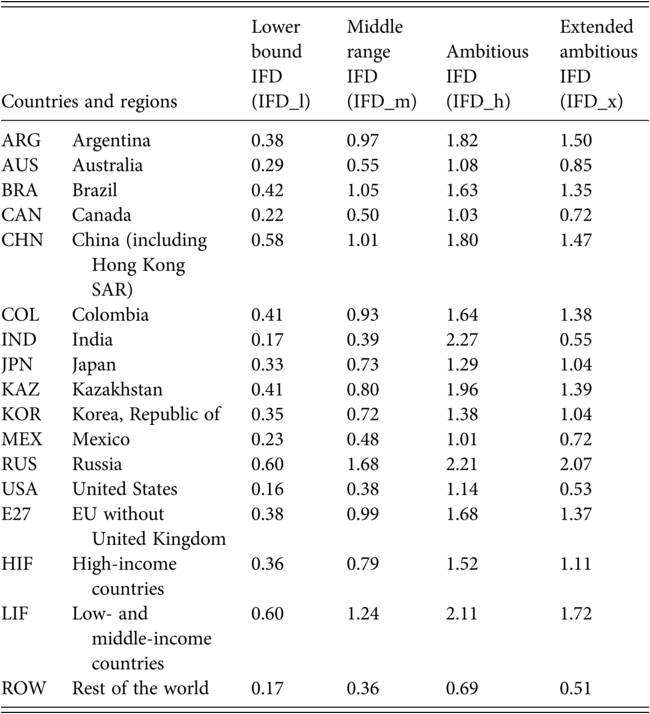

The model does report changes in GDP or regional incomes.Footnote 30 The country-specific GDP impact illustrated in Table 5.4 is generally consistent with the discussed welfare results. However, proportional changes in GDP tend to be somewhat smaller than welfare impacts because the basis is total income (including government spending and investment), whereas the basis for welfare is only private consumption. Table 5.4 and Figure 5.1 reflect this.

| Countries and regions | Lower bound IFD (IFD_l) | Middle range IFD (IFD_m) | Ambitious IFD (IFD_h) | Extended ambitious IFD (IFD_x) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARG | Argentina | 0.38 | 0.97 | 1.82 | 1.50 |

| AUS | Australia | 0.29 | 0.55 | 1.08 | 0.85 |

| BRA | Brazil | 0.42 | 1.05 | 1.63 | 1.35 |

| CAN | Canada | 0.22 | 0.50 | 1.03 | 0.72 |

| CHN | China (including Hong Kong SAR) | 0.58 | 1.01 | 1.80 | 1.47 |

| COL | Colombia | 0.41 | 0.93 | 1.64 | 1.38 |

| IND | India | 0.17 | 0.39 | 2.27 | 0.55 |

| JPN | Japan | 0.33 | 0.73 | 1.29 | 1.04 |

| KAZ | Kazakhstan | 0.41 | 0.80 | 1.96 | 1.39 |

| KOR | Korea, Republic of | 0.35 | 0.72 | 1.38 | 1.04 |

| MEX | Mexico | 0.23 | 0.48 | 1.01 | 0.72 |

| RUS | Russia | 0.60 | 1.68 | 2.21 | 2.07 |

| USA | United States | 0.16 | 0.38 | 1.14 | 0.53 |

| E27 | EU without United Kingdom | 0.38 | 0.99 | 1.68 | 1.37 |

| HIF | High-income countries | 0.36 | 0.79 | 1.52 | 1.11 |

| LIF | Low- and middle-income countries | 0.60 | 1.24 | 2.11 | 1.72 |

| ROW | Rest of the world | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.51 |

5.5 Critical Ad Hoc Assumptions

Computation of innovative models exploring new research questions like the impact of investment facilitation requires a substantial collection of data inputs. As this is a nascent attempt at quantification, we make some uncomfortable assumptions that will need to be addressed in future research. In the following, we present a set of critical assumptions made for the BRF calibration. Model results are conditional on (and sensitive to) these assumptions, which are not well informed by the data.

(1) Elasticity of substitution (

): The elasticity of substitution across BRF varieties indicates the marginal value of a new variety. The lower is the elasticity, the more valuable is a new variety. Using the value adopted by Balistreri, Tarr, and YonezawaFootnote 31 for their FDI sectors, we assume an elasticity of three. This is generally on the lower end of many estimates, and so the expectation is that welfare impacts might be mitigated as the estimate is refined.

): The elasticity of substitution across BRF varieties indicates the marginal value of a new variety. The lower is the elasticity, the more valuable is a new variety. Using the value adopted by Balistreri, Tarr, and YonezawaFootnote 31 for their FDI sectors, we assume an elasticity of three. This is generally on the lower end of many estimates, and so the expectation is that welfare impacts might be mitigated as the estimate is refined.(2) The local supply elasticity of monopolistically competitive inputs (

): The supply elasticity indicates the degree to which firms can substitute away from the bilateral specific factor. The higher the elasticity, the more responsive output is, but the less revenues are allocated to the specific factor rents. The model is sensitive to this elasticity, with larger welfare gains for liberalizing regions under higher elasticities.

): The supply elasticity indicates the degree to which firms can substitute away from the bilateral specific factor. The higher the elasticity, the more responsive output is, but the less revenues are allocated to the specific factor rents. The model is sensitive to this elasticity, with larger welfare gains for liberalizing regions under higher elasticities.(3) For the SER (services) sector, we assume that 40 percent of observed cross-border provision is a specialized input for the associated multinational. That is, for example, an EU financial firm operating in Kenya will have specialized cross-border imports of financial services from the EU that are used to facilitate FDI supply. The specialized input formulation is developed by Markusen, Rutherford, and Tarr.Footnote 32 While this parameter is necessary for an operational model, its measurement is difficult. Some limited information may be available from proprietary firm-level data.

(4) Since not all measures covered by the IFI induce costs to FDI firms, we make a scalar adjustment to the IFI of 0.05 to arrive at an actionable ad valorem model shock related to the IFD. Thus, we assume that 5 percent of the suggested reductions in investment barriers by the IFI (illustrated in Table 5.2) would lead to actual cost reductions for FDI firms. This scalar adjustment, by design, preserves the relative variation in the IFI across countries, but its level is uncertain. Conservatively, we consider at least 5 percent of the IFI as actionable under the adoption of an IFD. After applying the 5 percent adjustment, the FDI weighted average ad valorem shock across the participating countries under our middle range simulation (IFD_m) is 0.5 percent.

We consider other studies that have looked at FDI barriers to give some context to our conservative assumption that the actionable ad valorem model shock is derived by taking a fraction, 5 percent, of the reported IFI change. As a point of comparison, after applying the 5 percent adjustment, the FDI weighted average ad valorem shock across participating countries under our middle range simulation (IFD_m) is 0.5 percent. This is a small ad valorem shock in comparison to that observed in other quantitative studies of FDI liberalization. This gives us confidence that we are not exaggerating the economic impacts of the IFD. In the following section, we include a set of sensitivity runs that adopt a less conservative assumption by applying a scalar adjustment of 10 percent, effectively doubling the ad valorem shocks.

Other studies that investigated FDI barriers suggest much larger AVEs and often apply 25–50 percent of those as an actionable model shock. For example, based on information about regulatory regimes, Jafari and TarrFootnote 33 develop a database on the barriers faced by foreign suppliers (discriminatory barriers) for 103 countries and 11 services sectors. They find that professional services (e.g., accounting, legal services) are among the sectors with the highest AVEs in high income countries (around 30 percent), but high-income countries have uniformly lower estimated AVEs than transition, developing or least developed countries. For instance, least developed countries (LDCs) exhibit the highest AVE in fixed line telephone services with an average of 764 percent (for thirteen countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, the estimated AVE equals to 915 percent). For the rest of services sectors, the average AVEs for LDCs range between 3 percent for retail trade and 56 percent for rail transport.

There are also studies estimating the FDI barriers for single countries. For instance, Balistreri, Jensen, and TarrFootnote 34 estimate and apply the AVEs of discriminatory and nondiscriminatory (apply equally to domestic and foreign firms) FDI barriers in services for Kenya. The values for nondiscriminatory barriers range between 2 percent for air transport and 57 percent for maritime transport. For discriminatory barriers, the upper bound is somewhat lower, with the highest AVE of 40 percent in maritime transport . For Belarus, Balistreri, Olekseyuk, and TarrFootnote 35 use nondiscriminatory barriers between 5.3 percent in communications and 47.5 percent for water, rail, and other transport, while discriminatory barriers for the same sectors amount to 2.3 percent and 42.5 percent, respectively. Similar studies also exist for Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Tanzania, etc. and suggest a broad range for FDI barriers reaching over 90 percent (in Georgia and Kazakhstan) or even 100 percent (in Armenia).Footnote 36 Thus, assuming 25–50 percent of the described AVEs as an actionable model shock, our assumption seems to be quite conservative.

5.6 Sensitivity Analysis

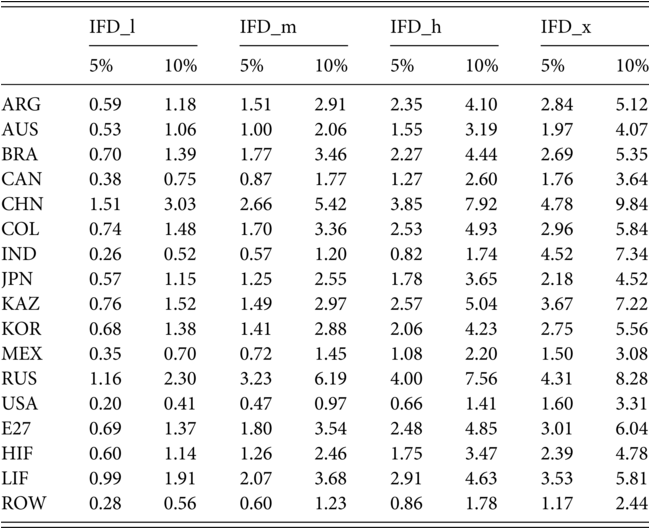

We proceed with a couple of exercises that illustrate the model’s sensitivity to our structural and parametric assumptions. Table 5.5 shows the comparison of welfare results under different assumptions of the scalar adjustment to the IFI, namely, 5 percent (our central assumption) and 10 percent. Since we prefer to be conservative in our central simulations, we would like to illustrate the magnitude of gains when we double the actionable ad valorem model shock related to the IFD. The results illustrate that a double scalar adjustment leads to welfare gains approximately twice as high as that in our central simulations. The global welfare increases by 1.11 percent under IFD_l and by 4.92 percent under IFD_x scenarios (compared to 0.56 percent and 2.46 percent in the central simulations, respectively). This corresponds to US$506 billion under the lower bound scenario and US$2,243 billion under the extended ambitious IFD.

| IFD_l | IFD_m | IFD_h | IFD_x | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 10% | 5% | 10% | 5% | 10% | 5% | 10% | |

| ARG | 0.59 | 1.18 | 1.51 | 2.91 | 2.35 | 4.10 | 2.84 | 5.12 |

| AUS | 0.53 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 2.06 | 1.55 | 3.19 | 1.97 | 4.07 |

| BRA | 0.70 | 1.39 | 1.77 | 3.46 | 2.27 | 4.44 | 2.69 | 5.35 |

| CAN | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 1.77 | 1.27 | 2.60 | 1.76 | 3.64 |

| CHN | 1.51 | 3.03 | 2.66 | 5.42 | 3.85 | 7.92 | 4.78 | 9.84 |

| COL | 0.74 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 3.36 | 2.53 | 4.93 | 2.96 | 5.84 |

| IND | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 1.20 | 0.82 | 1.74 | 4.52 | 7.34 |

| JPN | 0.57 | 1.15 | 1.25 | 2.55 | 1.78 | 3.65 | 2.18 | 4.52 |

| KAZ | 0.76 | 1.52 | 1.49 | 2.97 | 2.57 | 5.04 | 3.67 | 7.22 |

| KOR | 0.68 | 1.38 | 1.41 | 2.88 | 2.06 | 4.23 | 2.75 | 5.56 |

| MEX | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 1.45 | 1.08 | 2.20 | 1.50 | 3.08 |

| RUS | 1.16 | 2.30 | 3.23 | 6.19 | 4.00 | 7.56 | 4.31 | 8.28 |

| USA | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 1.41 | 1.60 | 3.31 |

| E27 | 0.69 | 1.37 | 1.80 | 3.54 | 2.48 | 4.85 | 3.01 | 6.04 |

| HIF | 0.60 | 1.14 | 1.26 | 2.46 | 1.75 | 3.47 | 2.39 | 4.78 |

| LIF | 0.99 | 1.91 | 2.07 | 3.68 | 2.91 | 4.63 | 3.53 | 5.81 |

| ROW | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 1.23 | 0.86 | 1.78 | 1.17 | 2.44 |

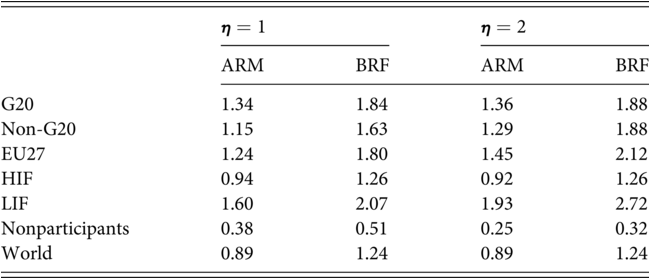

In Table 5.6, we consider the percentage welfare impact of the middle range scenario (IFD_m) under the central BRF monopolistic competition structure and under the full Armington treatment (under Armington, the MAN and SER sectors are treated as perfectly competitive).Footnote 37 The BRF structure does indicate substantially larger gains from the IFD. Across all regions, there are larger gains under the BRF structure, and even larger spillovers for the nonparticipating countries. On average, the gains are about 40 percent higher under BRF monopolistic competition. Our experience is that most of the added gains can be attributed to new variety gains. These extensive-margin gains are not available under the Armington formulation.

Table 5.6 Sensitivity across structural and parametric assumptions for the middle range IFD scenario (percent equivalent variation)

| ARM | BRF | ARM | BRF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G20 | 1.34 | 1.84 | 1.36 | 1.88 |

| Non-G20 | 1.15 | 1.63 | 1.29 | 1.88 |

| EU27 | 1.24 | 1.80 | 1.45 | 2.12 |

| HIF | 0.94 | 1.26 | 0.92 | 1.26 |

| LIF | 1.60 | 2.07 | 1.93 | 2.72 |

| Nonparticipants | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

| World | 0.89 | 1.24 | 0.89 | 1.24 |

Calculating an exact attribution of the welfare gains from new varieties is challenging because in general equilibrium, the relative prices of varieties are in flux. The complex computation of variety gains, as suggested by Feenstra,Footnote 38 for example, applies in the context of a one-sector model without intermediate inputs. We can illustrate qualitative impacts, however, by reporting the weighted average change in entry of FDI varieties. In our central middle range scenario (IFD_m), the weighted average (across participating countries) increase in FDI manufacturing varieties is 0.3 percent, and the weighted average increase in FDI service varieties is 0.4 percent. This compares to no variety gains under the Armington treatment. New varieties in our central treatment translate directly into productivity and welfare gains by better fulfilling the needs of firms buying intermediates and consumption by households.Footnote 39

We emphasize that parametric sensitivity is also important. In Table 5.6, we also provide one example for the middle range scenario. Doubling the local supply elasticity (η = 2) increases the gains from the IFD for participants but mitigates the spillovers to nonparticipants (comparison of the BRF structure for ![]() and

and ![]() ). This is logically consistent. With a higher elasticity, the participants can take advantage of the liberalization, but it also means that nonparticipants can be more easily squeezed out of the market. Thus, competitive effects are exacerbated under higher elasticities.

). This is logically consistent. With a higher elasticity, the participants can take advantage of the liberalization, but it also means that nonparticipants can be more easily squeezed out of the market. Thus, competitive effects are exacerbated under higher elasticities.

5.7 Conclusion

In this chapter, we develop an innovative quantitative model for assessing the economic impacts of an IFD Agreement. We utilize the newly developed IFIFootnote 40 to inform model shocks and run scenarios consistent with the WTO structured discussions on investment facilitation. The model includes an innovative monopolistic competition structure and is calibrated to the GTAP 10 accounts. Our objective of including FDI in manufacturing and service sectors means that the data requirements exceed those available from GTAP. In particular, we need data that establish FDI stocks and the relationships between FDI firms and their home-country (specialized) inputs. A careful collection of these data is beyond the current scope of this chapter. Thus, our results rely on a set of key assumptions that will need to be addressed in future research.

Our model results generally illustrate that the deeper an IFD Agreement and the higher the applied shocks, the higher are the gains. For the world as an aggregate, welfare gains range between 0.56 percent under the lower bound IFD and 1.74 percent under the ambitious scenario. The benefits are concentrated among the countries that participated in structured discussions, with the highest increase in welfare realized by the low- and middle-income countries. Given their low level of current practice in investment facilitation and the highest policy shocks among all regions, these countries will be the biggest winners of a deep and comprehensive multilateral deal. In monetary terms, the expected gains of the low- and middle-income countries range between US$10 and US$30 billion depending on the depth of a potential IFD. Global gains may exceed US$790 billion, with substantial benefits for the EU (24–28 percent) and other participating G20 countries (43–46 percent).

Interestingly, there are notable spillover gains from applied investment facilitation reforms to countries taking no action under the agreement (between 0.20 percent and 0.82 percent). Joining a potential agreement is still very attractive to those countries with a low level of current practice in the field. Our extended ambitious IFD scenario with India and the United States among the members indicates significant benefits for India, with a welfare gain of 4.52 percent. The United States, in contrast, does not show such a dramatic increase from participation, with a welfare gain of 1.60 percent.

The presented results illustrate the potential impact of an IFD Agreement, which is closer to the lower bound for several reasons. First, even our ambitious scenario is still quite limited since it covers around a half of measures of IFI, which provides an in-depth concept of investment facilitation. If the IFD Agreement goes beyond measures covered in our policy shocks, the impact would increase. Second, a broader country coverage would also increase the global welfare gains. In this analysis, we focus on the list of countries that engaged in the structured discussions in the beginning of the process, while there are now over 100 countries taking part in the negotiations. Third, we prefer to be conservative in our central simulations, assuming a rather low ad valorem model shock. Our less conservative sensitivity runs (doubling the ad valorem shock) indicate much higher global welfare gains: 1.11 percent under the lower bound and 3.47 percent under the ambitious scenarios. This corresponds to US$506 billion under the lower bound scenario and almost US$1,580 billion under the ambitious IFD. Overall, our empirical results and, in general, the class of models employed suggest that the potential gains from an IFD significantly exceed those available from traditional tariff liberalization.

This analysis contributes to the very scarce research on investment facilitation and has the potential to provide policymakers with important information on the effects of the multilateral agreement. Applying the demonstrated model gives useful information on what instruments and the degree of investment facilitation commitments are needed to substantially enhance economic performance. It also provides a framework for considering the impacts and incentives for those countries that have chosen not to participate in the structured discussions.

6.1 Introduction

Negotiations toward an Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement have been concluded in July 2023 at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Eight more member countries joined the negotiations in November 2021, bringing the total number of participating countries to 112. A leaked draft of the agreement, called the ‘Easter Text’,Footnote 1 suggests that parties have made significant progress toward an agreement. The conclusion of the IFD Agreement marks an important juncture in the global politics of foreign investment. Earlier attempts at negotiating multilateral investment rules – including the 1995 Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) under the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) – were thwarted in part by opposition from developing countries.Footnote 2 Investment was also one of three ‘Singapore Issues’ dropped from the Doha Agenda in 2003 after strong objections from China, India, and Brazil over expanding the WTO’s remit over non-trade-related investment matters. Momentum toward the IFD Agreement therefore raises important questions: What changes in the global politics of investment have made this initiative possible? And, what political challenges remain?

This chapter is dedicated to the political economy of multilateral investment rules. It examines the domestic and international pressures that inform the positions of three emerging powers – China, India, and Brazil – toward the IFD initiative. It focuses on these three countries not strictly for comparative purposes but to illustrate the domestic and international factors that have made progress on the IFD Agreement possible and those that may stand in the way of a successful implementation of the agreement. As three influential WTO members, India, China, and Brazil are key to the future direction of the WTO, yet they have taken different positions on the IFD Agreement. While China and Brazil champion the agreement, India is a vocal opponent. What is striking about these different positions is that all three countries claim to represent the interests of the developing world.

The chapter highlights three factors that have provided conducive grounds for the agreement, namely, the dissolution of capital-importing versus capital-exporting dichotomies in country identities; a corresponding convergence in interests among select WTO members; the questioned legitimacy in investment treaty law, which has created an opportunity for new thinking around investment rules; and expanded political space for new voices inside the WTO. At the same time, proponents will continue to struggle with lingering concerns from other WTO members about the policy space and asymmetries in existing trade rules. The chapter proceeds as follows: The next section provides necessary historical context to understanding contemporary debates on multilateral investment rules. It focuses primarily on the global politics of investment and the historic failures of countries to arrive at a multilateral investment agreement. The third section deals with the domestic and international factors driving country positions on the IFD Agreement in China, India, and Brazil. The last section offers some observations about what concessions may be needed to successfully multilateralize the agreement.

6.2 The Global Politics of Multilateral Investment Rules

The first step toward the IFD Agreement was taken during the 11th Ministerial Conference in December 2017 when WTO members adopted a Joint Ministerial Statement on Investment Facilitation for Development, calling for structured discussions on the development of a multilateral framework on investment facilitation.Footnote 3 The joint statement initiative was endorsed by seventy country members at varying levels of development from almost all continents. Notable abstentions include the United States and India. South Africa also objected, as discussed in this book (see Chapter 14). A set of informal discussions was then led by the Friends for Investment Facilitation for Development (FIFD), a coalition of seventeen developing country members with formal negotiations beginning in September 2020. Negotiations have focused on the following key areas: improving the transparency and predictability of investment measures; simplifying and speeding up investment-related administrative procedures; strengthening dialogue between governments and investors; promoting the uptake by companies of responsible business practices; and ensuring special and differential treatment (SDT), technical assistance, and capacity building for developing and least-developed countries.Footnote 4 Proponents hoped to conclude a draft agreement by November 2021 in time for the 12th Ministerial Conference in Geneva; however, that conference was ultimately placed on hold by the COVID-19 pandemic. When the Ministerial Conference resumed in June 2022, IFD was left off the agenda as WTO members prioritized negotiations on food security and intellectual property rights. Nevertheless, text-based negotiations were concluded by July 2023.

That over 110 member countries are participating in this plurilateral initiative is a remarkable success, given the politicized nature of the WTO at present and previous failures at negotiating multi- and plurilateral investment rules. To some scholars, the failure of past initiatives is hardly surprising, given that multilateral arrangements dispel the competitive dynamics between countries that are key to commitment making. Commenting on the success of bilateral investment treaties (BITs), Andrew GuzmanFootnote 5 argues that multilateral initiatives fail precisely because they apply to each participant equally as a group. That no country derives an advantage in the global competition to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) means that governments face few incentives to sign onto multilateral arrangements. Instead, governments are more likely to work together to resist since they recognize that they are better off preserving their freedom of movement.

One factor that helps to explain recent momentum behind the IFD Agreement is that it departs significantly from past multilateral initiatives in the depth of integration demanded of participants. During the MAI and FTAA negotiations, influential capital-exporting countries pushed for high standards of investment liberalization and protection as well as provisions on investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) to reinforce them.Footnote 6 These provisions evoked strong opposition from developing countries over fears that they would unduly constrain their policy space. Civil society groups also contested the regulatory amendments that would have been required to bring the agreements into force.Footnote 7 In the last two decades, investment protection standards and ISDS have faced controversy due to a growing number of arbitral claims brought against governments under BITs and investment chapters in free trade agreements. Invoking these standards, foreign investors have won multi-million-dollar awards against governments that instituted public policies that negatively impacted their economic interests, policies related to basic service provision, public health, and natural resource governance. These awards have generated fears of regulatory chill in countries that belong to BITs and growing calls for the reform of countries’ BIT commitments.

The IFD Agreement excludes issues of investment protection and liberalization. Proponents claim that it is more of a technical agreement about the ‘nuts and bolts’ of encouraging – not regulating – sustainable FDI flows.Footnote 8 While definitions vary, investment facilitation is generally understood as ‘a set of practical measures concerned with improving the transparency and predictability of investment frameworks, streamlining procedures related to foreign investors, and enhancing coordination and cooperation between stakeholders, such as host and home-country government, foreign investors and domestic corporations, as well as societal actors’.Footnote 9 By excluding investment protections, advocates claim that the IFD Agreement will avoid impinging on a domestic policy space. As GaborFootnote 10 argues, investment facilitation is not about ‘whether investment related policies, laws and regulations should be changed but rather how those policies, laws and regulations currently in place are implemented, and what could be done to make their implementation more transparent and predictable’. A common example of an investment facilitation measure is the single electronic window (SEW), a national electronic platform that would provide investors ready access to information and enable them to fulfill administrative requirements and pay relevant fees. SEWs are meant to enhance the transparency and efficiency of administrative procedures while reducing the bureaucratic burden placed on investors. Framing the IFD Agreement as a ‘technical agreement’ that complements – not impinges on – governments’ regulatory capacity seems to have eased concerns among some countries that once staunchly opposed the WTO’s oversight in matters of investment. This includes Brazil, which along with other developing countries, opposed United States’ efforts to place investment on the WTO’s negotiating agenda during the Uruguay Round.Footnote 11

Progress toward the IFD Agreement may also represent a new (and increasingly rare) instance of interstate cooperation on an economic matter vital to the interests of developing countries. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development,Footnote 12 governments of developing countries face an annual investment gap of US$2.5 trillion in meeting their sustainable development goals, and foreign investment will ultimately play a vital role in addressing this gap. There appears to be a growing consensus on the need for investment facilitation in national, regional, and plurilateral circles to help countries achieve these goals. The IFD Agreement builds on preexisting initiatives. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation endorsed an investment facilitation action plan as early as 2008.Footnote 13 Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa agreed upon a Trade and Investment Facilitation Action Plan in 2014. The OECD and UNCTAD released policy documents that called on member countries to encourage investment facilitation measures with the 2015 Policy Framework for Investment and the updated 2016 Global Action Menu for Investment Facilitation, respectively. These various initiatives suggest that investment facilitation is a promising area of agreement in an otherwise contested policy area.

The IFD Agreement builds on another important precedence: the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). WTO members accepted the notion of needing to ‘facilitate’ processes of economic integration with the conclusion of the TFA in 2013. The IFD Agreement has been framed as a natural corollary of the TFA by experts and some member states.Footnote 14 Country proposals for the IFD Agreement carry forward some of the TFA’s main elements, including its emphasis on maximizing transparency and efficiency in administrative procedures, the potential for electronic governance, and the need for capacity building. Progress toward the IFD Agreement may therefore represent an emerging norm, not about investment liberalization but about the importance of transparency and efficiency in the execution of laws and regulation that concern trade and investment (as well as their interlinkages). Underlying this emerging consensus on facilitation is a more established norm about the role foreign investors can and should play in promoting sustainable development.

Another conducive change in the global politics of investment surrounds the shifting identities of WTO members. Country positions on multilateral investment rules no longer correspond strongly to a capital-importing versus -exporting country dichotomy as they did during the MAI, FTAA, and TRIMs negotiations. Changing patterns of investment, rapid economic growth in countries like China and India, and controversies surrounding investment treaty law have complicated traditional understandings of where country interests lie. As SauvantFootnote 15 argues, emerging powers no longer consider their defensive policy interests as host-states but also their offensive interests as home-states to powerful multinational enterprises (MNEs). At the same time, advanced economies like Canada and Australia have been forced to consider their defensive interests more strongly due to rising investment from emerging markets in security-related sectors and high-profile legal claims by foreign investors.

In a stark departure from the past, developing countries are the main forces behind the reintroduction of investment-related matters in the WTO. The Joint Statement Initiative originated from the efforts of two country coalitions – FIFD and MIKTA, an alliance of Mexico, Indonesia, Korea, Turkey, and Australia – that brought forward proposals for structured discussions on investment facilitation during the 2017 Ministerial meeting. Russia, China, and Argentina and Brazil (jointly) also submitted proposals.Footnote 16 This is while traditional advocates of investment rules – namely, the United States and EU member countries – have taken a back seat.

Still, the IFD Agreement negotiations have not been without controversy. Some of the most vocal opposition has come from other emerging powers, including India and South Africa. India and South Africa objected to the negotiations on the basis that joint statement initiatives were resulting in ‘the marginalization of existing multilateral mandates arrived at through consensus in favor of matters without multilateral mandates’.Footnote 17 The Indian government also expressed concerns about the constraining effects of an IFD Agreement on government policy space. Academics and civil society groups caution that the investment facilitation agenda may focus disproportionately on making it easier for foreign investors to operate in host-countries, while more urgent concerns related to the promotion of sustainable development are neglected. For instance, Coleman et al.Footnote 18 point out that proposals to include commitments on regulatory streamlining might create incentives to ease environmental assessment regulations. Others argue that an IFD Agreement may impose steep adjustment costs on countries that are already struggling to meet their WTO commitments.

The IFD Agreement has also been bound up with political debates surrounding the WTO’s future in global economic governance. WTO members are currently grappling with foundational debates about the future of the trade organization that will inevitably affect the success of the IFD Agreement. Most notable perhaps are highly contentious debates on the dispute settlement mechanism and the SDT principle, the latter of which have been driven by United States’ demands for the ‘graduation’ from the SDT status of emerging powers like India and China.

Emergent norms and shifting identities may help explain recent momentum toward the IFD Agreement, but they do not explain why some countries continue to hold out. Explaining individual country preferences requires examining the domestic and international pressures that shape countries’ foreign policy agendas. As Robert PutnamFootnote 19 famously observed, governments are often forced to balance competing demands not just from the international arena but also from domestic actors and conditions. It is the confluence of international and domestic conditions, which will ultimately shape the success of the IFD Agreement initiative. The next section discusses how domestic and international factors have interacted to shape the preferences of three influential WTO members.

6.3 The Politics of an IFD Agreement

6.3.1 China

As coordinator of FIFD, China was a major force behind the 2017 joint statement in support of the IFD Agreement. Even before informal discussions on the IFD Agreement were launched, China encouraged consensus building on investment facilitation measures during its tenure as president of the G20.Footnote 20 China has since become one of the most vocal proponents of the agreement inside and outside of the WTO. Scholars attribute China’s interest in investment facilitation to its status as a net exporter of capital.Footnote 21 Multilateral rules on investment facilitation will reduce the transaction costs for Chinese firms and state-owned enterprises when investing abroad. However, China’s economic status does not fully explain why the Chinese government sees the WTO as an appropriate venue in which to advance multilateral investment rules nor why it stopped short of pursuing investment protections. As this section discusses, China’s interest in investment facilitation reflects a confluence of international and domestic pressures as well as its growing confidence on the world stage.

Chinese outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) has increased steadily since 2002, surpassing inward FDI flows for the first time in 2015 (see Figure 6.1) and OFDI stocks soon followed, exceeding inward FDI stocks in 2017 (see Figure 6.2). It is true therefore that China’s interest in investment facilitation has grown in step with its status as a capital exporter. But its interests also reflect important changes in China’s domestic economic and political landscape, which made this status possible.

Figure 6.1 China FDI flows inward and outward (US$ billion).

Figure 6.2 China FDI stocks inward and outward (US$ billion).

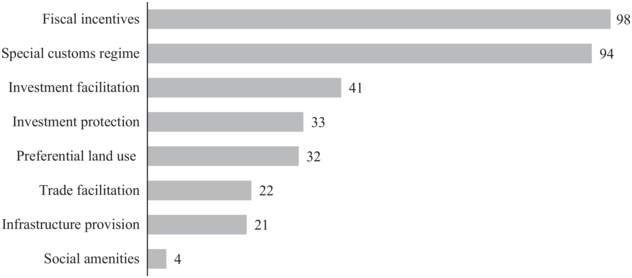

Prior to the late 1970s, China’s foreign economic policy was predominantly protectionist. The imposition of foreign investment on China after the Opium Wars and the Sino-Japanese War during the nineteenth century fostered resentment toward foreign capitalists in the decades that followed. Chinese leaders began instituting reforms aimed at liberalizing the domestic investment market as part of a broader program of ‘opening up’ the economy toward the late 1970s. By then, attitudes toward foreign investment had begun to warm amid growing demands for economic modernization. Foreign investment – and the promise of new technology, managerial skills, and access to foreign markets – came to be seen as a necessary means to modernize industrial sectors where productivity lagged. Even then, FDI was restricted to special economic zones near urban centers where foreign investors received preferential terms, including tax incentives, export duty exemptions, and fiscal and foreign exchange privileges.Footnote 22

The Chinese government began moving away from its ‘permissive’ approach toward an active program of FDI attraction in the mid-1980s. Further reforms were introduced in the 1990s, including the 1995 Interim Provisions on Guiding Foreign Investment and the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries, which aimed to attract FDI into favored sectors while protecting sensitive industry like banking, cultural industries, and telecommunications. China’s 10th Five-Year Plan marked an important departure. Launched in 2001, the Plan committed to encouraging national firms to go overseas.Footnote 23 Following the Plan, the Chinese government relaxed approval processes for overseas investment and established minor financial and diplomatic support to would-be investors. However, OFDI remained low and concentrated in a limited number of sectors. In 2012, China switched from a policy of ‘going in’ to a policy of ‘going out’, involving the more active promotion of Chinese FDI abroad. This policy was epitomized in the 2013 launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).Footnote 24

The shift in Chinese foreign investment policy was for the most part a state-led initiative. In a one-party state, private enterprise lacked effective channels of influence in policymaking circles. Chinese OFDI was also dominated by a relatively small number of state-owned enterprises administered by the Central Government’s ministries and agencies (anywhere between 73.5 and 86.4 percent of OFDI between 2003 and 2006). The remaining share of FDI flows and stocks were made by SOEs administered by regional governments. The private firms’ share of FDI was minimal: In 2005, private firms accounted for 1.5 percent of OFDI, and by the end of 2006, just 1 percent.Footnote 25

According to Cheng and Ma,Footnote 26 the Chinese government’s interest in promoting OFDI grew as a result of competitive pressures, such as the desire to secure key natural resources and technologies to feed its internal development. OFDI was directed toward sectors like agriculture, cattle breeding, fisheries, mining, manufacturing, and service industries. China’s 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) emphasized the need to secure the domestic energy supply by tapping foreign sources. OFDI in oil, gas, and other forms of energy helped feed China’s massive growth rates. There was also a growing awareness that Chinese firms needed to compete in the global arena as foreign firms expanded their presence in China. As such, China sought to promote the multinationalization of select enterprises. But as BrownFootnote 27 observes, China also needed to find a new way of spending its massive foreign exchange reserves. By the mid-2000s, China had amassed over a trillion dollars in foreign reserves due largely to the country’s trade deficit with advanced economies like the United Kingdom and the United States. Outward investment provided higher returns than purchasing additional United States’ debt and helped alleviate excess liquidity in the Chinese economy.

Promoting OFDI also fit into China’s non-material concerns. China’s international reputation suffered after the June 4 incident. International concern over the country’s human rights record remained high throughout the 1990s. As a result, the Chinese government undertook a rebranding exercise aimed at replenishing its soft power. Pledging investment and aid to developing countries was a means of improving China’s image. And more developing countries came to view China as a positive role model for how a country could transform and modernize its economy through state intervention.Footnote 28 Over time, the Chinese Communist Party also came to depend increasingly on the promise of economic progress and poverty alleviation for its political appeal at home.

Changing ideas about the role of foreign investment, global economic competition, and the search for soft power at home and abroad help explain the country’s burgeoning interests in exporting capital. Yet, China’s capital-exporting status does not fully explain why the Chinese government pursued investment facilitation measures at the WTO instead of bilateral and regional arrangements, which are easier to negotiate and where it arguably has greater bargaining power.

Understanding China’s interest in investment facilitation requires understanding its own experience in resolving bureaucratic hurdles needed to achieve its investment policy objectives. Indeed, Chinese investors did not respond automatically to government incentives aimed at promoting OFDI. Administrative barriers dampened OFDI flows until investment facilitation measures were introduced. In the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese investors were required to obtain approval from the Central Government before undertaking an investment project. The regulation of OFDI was further dispersed across various government agencies with limited administrative capacity. According to Yang and others,Footnote 29 many would-be investors found the approval process slow, complicated, and opaque. Beginning in 2009, the Chinese government began introducing measures aimed at simplifying the approval process (e.g., by delegating the power of approval to local departments). As a result, the pace of overseas investment began to increase.

The Chinese government overhauled its outward investment regime again in 2013 to coincide with the launch of the BRI. The administrative review process was further streamlined and loosened, and vertical and horizontal cooperation among regulatory agencies was enhanced.Footnote 30 Then in 2017, the National Development and Reform Commission launched the National Investment Project Online Approval and Supervision Platform with the aim of enhancing the efficiency and transparency of investment governance. This platform is akin to an SEW in that it provides a single access point for domestic and outbound investors to the investment approval and supervision process. As a result of these changes and other measures aimed at improving its business environment, China rose on the World Bank’s now defunct Ease of Doing Business Index from 90th place in 2008 to 32nd in 2019. China’s faith in investment facilitation measures may therefore reflect its own experience in tackling the bureaucratic obstacles needed to realize its capital-exporting status.

Efforts to multilateralize investment facilitation measures via the WTO reflect China’s increasing willingness to occupy center stage in the global arena. China’s confidence has grown in step with its economic clout. Chinese nationals have taken on leadership roles in several international institutions, including in UN agencies and the G20. Generally, China is not interested in restructuring or doing away with existing global economic institutions. The Chinese government has not offered new models of governance for global finance, trade, or investment. Rather, China has sought to repurpose Western laws and institutions so that they better suit the interests of new (i.e., developing country) actors and a wider array of political and economic models.Footnote 31

It follows that China has taken a more assertive role in defining the future of the WTO, largely by layering on top of existing trade rules those that better suit the needs and interests of non-Western countries. For the first fifteen years of its membership, China’s engagement within the WTO reflected a policy of ‘active learning’ aimed at building its capacity to navigate extant rules and structures. Much has changed in the last half decade. China has played an important role in several new joint statement initiatives, including investment facilitation and e-commerce. These initiatives have been framed as part of an effort to share the lessons of China’s own economic success, which includes investment facilitation. China’s permanent representative and Ambassador to the WTO Zhang XiangchenFootnote 32 explained this goal best when he stated, ‘China needs to make greater contributions and add Chinese wisdom to global trade liberalization and investment facilitation, as well as help create an in-time reform of the multilateral trade system’. The Chinese government learned from its own experience the added value of investment facilitation and now aims to export these lessons as part of a ‘win–win’ strategy.

It should also be noted that China continues to negotiate standard investment protections in bilateral and regional arrangements, including the Regional Cooperation and Economic Partnership agreement concluded in 2020. China now belongs to the second-highest number of investment treaties out of any country in the world (next to Germany). And until recently, China was a rule-taker, not a rule-maker in treaty negotiations. However, China has become more assertive in treaty negotiations. According to Levine,Footnote 33 Chinese drafters demonstrate a desire to experiment with novel formulations that expand or narrow investment protections according to China’s own interests, and recent treaties suggest that it has been successful. However, consolidating investment protections in the WTO is all but unfeasible, given the historic resistance of developing countries to these standards and the current legitimacy crisis engulfing BITs.

Championing investment facilitation measures is also more consistent with China’s foreign policy principles of nonintervention and mutual gain. As advocates argue, investment facilitation measures are less constraining on the policy space of signatory governments and therefore offer greater flexibility to governments across different political and economic systems. Investment facilitation measures are also less threatening to host-countries with lingering concerns over Chinese OFDI. The majority of China’s OFDI continues to be made by firms that have a close relationship with various levels of government, and most overseas investment by private firms continues to require government approval. Some countries have responded to the growth of Chinese investment with national security concerns as a result and have imposed new restrictions on Chinese investment. For instance, EU and the United States governments tightened the screening of Chinese investments amid concern that they might compromise national security.

Historically, China’s foreign investment policy reflected its state interventionist tradition as well as the more traditional concerns of capital-importing countries. But by the end of 2012, China moved toward a strategy of ‘going out’, combining a more concerted effort to promote the internationalization of Chinese firms with a growing role on the world stage. China aims not to revise existing trade rules but to layer on top of them rules that are more inclusive and that better fit the perceived interests of Global South members. However, as discussed in the next section, China’s efforts in layering may be hindered by the rather unstable foundations provided by the defunct Doha Development Agenda.

6.3.2 India

India was an early and vocal critic of the IFD Agreement. While some signs suggest its position has warmed, India’s signature is absent from joint statement issued in favor of the IFD Agreement in December 2021. That is not to say that India opposes international rules on investment facilitation. India has signed a host of bilateral arrangements that include investment facilitation measures, including an Investment Cooperation and Facilitation Treaty with Brazil in January 2020. Rather, India’s objections fall squarely on the inclusion of investment facilitation measures under the WTO. The Indian government frames its opposition with reference to two main points: First, Indian officials believe that no new issues should be added to the WTO agenda before the Doha Development Agenda is completed, and second, Indian officials are concerned that investment facilitation rules would constrain domestic policy space. This section details the domestic and international pressures that inform these concerns.

India has been a vocal proponent of developing country interests within the WTO since the organization’s foundation in 1995. The Indian government strongly contests asymmetries in existing trade rules, particularly in the Agreement on Agriculture. As leader of the G33 coalition of developing countries, India has pressed for protections in agriculture that would promote food security, rural livelihoods, and rural development. India’s habit of pushing back against the demands of advanced economies reflects the country’s colonial past and the historic predominance of import substitution industrialization as a policy paradigm, which began under the Nehru government (1947–1964) shortly after the country’s independence from Britain. Despite its pro-business rhetoric, the government of Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (2014–present) has pursued what Elizabeth ChatterjeeFootnote 34 calls a new developmentalist strategy combining liberalization (and the promotion of favored private industry) with the maintenance of selective intervention. Reflecting this strategy, the Modi government has sought to navigate the global trade regime and promote the growth of externally oriented business while maintaining room for India’s new developmental state. This time, however, India’s concern for policy space pits it against other developing countries.