Introduction

Catalonia’s position on the frontier between what have become Spain and France has made it the sort of periphery which can be critical to a ruling core, but which rarely directs core policy, despite some economic importance.Footnote 1 Only in the Middle Ages can a Catalonia be found that was not governed either from a distant centre to which its counties were, if not peripheral, at least secondary – such as the united Spanish Crown – or by a Catalonia-based power whose legitimacy derived from elsewhere, such as the kings of Aragón. To complicate matters, medieval Catalonia was not a unit, but a disparate set of counties initially grouped under rival families of counts, not all related.Footnote 2 Nonetheless, from the tenth century, the growing importance of the count-marquises of Barcelona gave this ‘pre-Catalonia’ its own peripheries, initially in the Pyrenees, but more famously thereafter in the ‘no-man’s land’ between Christian and Muslim polities to the south-west.Footnote 3 Over the following centuries, accelerated by the collapse of Umayyad rule at Córdoba after 1013, that space was closed up by colonization and military take-over, in a process many scholars no longer call Reconquesta (Sp. Reconquista; ‘reconquest’).Footnote 4 But in the tenth century, the south-western edge of this cohering space was substantially ungoverned, and subject to pioneer efforts by various agencies, although which agencies is a matter of historiographic debate. This article’s task is to reassert the secular church as a factor in that debate.

A good place to start is the city of Manresa. One of the Catalan counties’ more substantial urban foci, Manresa was also one of the furthest-flung, an originally Roman town deep in the Llobregat valley.Footnote 5 It was neither the seat of a count, the centre of a county nor an episcopal see. For these functions, Manresa looked to the older city of Vic d’Osona to its north-east.Footnote 6 Vic’s bishop acted as the distant head of Manresa’s clergy and, to some extent, as the local count; mostly, however, the town and its church were left to govern themselves.Footnote 7 It is, nonetheless, quite well documented, which allows a close study of how the church was established, or re-established, in this peripheral zone.

Debate over Frontier Settlement

There already exist competing answers for how this happened.Footnote 8 Peasants might begin a settlement venture themselves, or with capital provided by an aristocrat or monastery with conditions involving dependence or renders. Once established, they might demand or even construct protection through fortifications. Alternatively, deeper needs of defence against Muslim raids might press the authorities to establish fortifications first, after which settlers would move in under their protective shadow or because of incentives offered by relevant patrons. Either way, before long they would need a church. With that church’s (re-)establishment, Christianity’s periphery was extended another step closer to Islam’s.

The agencies that founded churches in this zone are also debated. It is accepted that monasteries, aristocrats and bishops all did so,Footnote 9 but the balance between them is contested. Moreover, some communities took the initiative themselves, as shown by the acts of consecration of the resulting churches.Footnote 10 These documents, almost unique to Catalonia, show bishops being brought out to areas that are sometimes not subsequently documented for decades, but which on such occasions still engaged with central authority.Footnote 11 The church on the periphery was thus one engine of that authority’s expansion.

Nature of the Frontier

There is, of course, an extensive historiography about the nature of frontiers, now and in the Middle Ages.Footnote 12 Its competing typologies of the frontier suggest the need to make clear what kind of frontier is envisaged in this article.Footnote 13 Likewise, in the light of anthropologically informed scholarship suggesting that borders have meaning only because of being enacted, it is worth asking who, in this article’s understanding, did the ‘borderwork’ of constructing a periphery as different from the spaces on either side of it.Footnote 14

The traditional dyad of open or closed frontiers, usually but wrongly attributed to Frederick Jackson Turner, is of limited help here.Footnote 15 The space beyond the developing edge of the Catalan counties clearly had geographical depth. The distance from Manresa to the nearest then-Muslim city, Lleida, was and is 100 km, and Manresa was itself somewhat of an outpost; from Lleida to both Barcelona and Vic, governmental centre to governmental centre, is 160 km. Much of the space between them was thinly populated, settled only by dispersed villa communities arrayed over some distance around their notional centres (often churches), or in isolated homesteads not part of wider units (and thus usually unknown to us except through archaeology).Footnote 16 What Turner called ‘free land’ was widely available, but the people to exploit it were not.Footnote 17 In this sense, this frontier was ‘open’; but since there was also a substantial power on its far side, it was finite and therefore also ‘closed’. On the Christian side, a network of fortresses spread into this zone from points of established government; some also existed outside central control.Footnote 18 The historiography in recent decades has de-emphasized emptiness, instead emphasizing the existence of ‘unconnected’ populations in these zones, whom sources from the centre considered bandits or heretics, if they were even mentioned. Even so, few would deny a lower population density in these areas than in those under more established governmental, and ecclesiastical, provision.Footnote 19 As to the enaction of this frontier, such ‘bordering’ was partly done by scribes who referred to such locations as being in marcis, marginis, limitibus (‘marches’, ‘margins’, ‘limits’) and so on, even though they also recorded established land tenure and boundaries there. However, it was also done by settlers who moved there to occupy land under favourable conditions which did not pertain closer to home, even though they probably had to compete for such lands with locals.Footnote 20 A difference regarding these spaces was recognized, if sometimes exaggerated, by contemporaries.Footnote 21 In accordance with the writings of those contemporaries, this article therefore understands this frontier as a space of low population density, with its population grouped sporadically, unrecognized by most wider governmental structures.

The Church and the Historiography

There is, as has already been noted, a reasonably settled paradigm that describes how and whence that population was increased and brought under authority.Footnote 22 The settling agency is almost always reckoned as monastic. This paradigm is quite easy to substantiate in the sources, but raises two problems which this article seeks to address.Footnote 23

The first is the peripheral church itself. The standard paradigm tends to assume a starting position of no church presence. Some outside agency would then have established churches and these, eventually, became sufficiently numerous to develop something like a parochial structure.Footnote 24 This presents two difficulties. Firstly, it is clear from the archaeology, especially from Santa Margarida de Martorell north-north-east of Barcelona, that churches could and did operate in these unconnected areas despite the lack of a supporting ecclesiastical structure; in Santa Margarida’s case, for six centuries before making it into the written record.Footnote 25 Ecclesiastical ground zero should therefore not always be assumed. Secondly, there is an intermediate step which is left unexplored: what happened between the first church consecration and the completion of the parish structure, and who brought it about? In this, the first churches and their incumbent clergy must have been critical.

Manresa and its Church

These are issues that the records from around Manresa can help us address. Hundreds of documents survive covering the city’s area following the Frankish conquest of the area in the early ninth century. Despite this, only one scholar has written about Manresa in this era, Albert Benet i Clarà.Footnote 26 Benet catalogued the area’s churches as they appear in the documentary record, but for the processes behind their appearance, he was reliant on the paradigm outlined above.Footnote 27 Despite his close acquaintance with the city, Benet did not make it one of his case studies of frontier development, focusing instead on the county around Manresa and the development of lay jurisdictions there. This makes sense for frontier development as Benet understood it: its first step was fortification, which was for him primarily the task of lay noble landowners, not the church.Footnote 28

Since Benet wrote, two things have happened which allow for a more detailed treatment of Manresa as a peripheral church in development. The first is a swing in the wider scholarship of frontiers and borderlands from studying processes of political control and settlement by outsiders, to studying the experiences and everyday strategies of the emplaced inhabitants of the border.Footnote 29 The second is the full publication of almost every surviving document covering the area up to the year 1000 as part of the century-long Catalunya Carolíngia project, with painstaking indices and now a digital search, making available to all data that even Benet did not have.Footnote 30 The area has also been mapped in the ongoing Atles dels comtats de la Catalunya carolíngia, thereby fixing many obscure locations.Footnote 31 With that apparatus to hand, it is possible to identify some of the local church’s principal figures, determine their spheres of action and rebalance the agency in their organization, between the usually-dominant monastic colonization and the organic expansion of local secular church provision.

Methodology and Material

The record is, however, neither straightforward nor narrative. There is no chronicle evidence beyond a few notes in Frankish sources; there are no episcopal or abbatial gesta or other forms of ecclesiastical history; there is not even much hagiography, and what does exist is of uncertain date or focused primarily on externalities.Footnote 32 Instead, the historian must work with hundreds of charters, detailing land sales and donations, wills, disputes and so forth.Footnote 33 This privileges the visibility of not just certain forms of social action, but also of certain social strata, the landed and respectable, with the poor or subject making few appearances. It also privileges men over women, although not to exclusion. And, perhaps surprisingly, it preserves lay interests over ecclesiastical ones. The preservation of this material, however much is now in public archives, has almost all been due to the church at some point, and it is therefore an understandable starting assumption that it concerns property that was of interest to, or ultimately owned by, the church, monastic or secular.Footnote 34 It is often possible to disprove that, however, and safer to say that the evidence we have was collected by people, or families, whose materials subsequently came to the church or were at some time stored in churches.Footnote 35

The major preserving institution in this article is the monastery of Sant Benet de Bages.Footnote 36 Sant Benet was founded in 950 by a magnate called Sal·la, who was a comital deputy (vicarius) and was responsible for many frontier building projects.Footnote 37 Of these, Sant Benet was probably the most enduring and successful. Admittedly, by the time the church there was consecrated in 972, Sal·la and one of his sons were already dead, and the other soon followed. The one grandson seems not to have taken an interest in the monastery, which was thus left unexpectedly independent, and in difficulties, by the 990s. Monks only begin to be recorded there after the consecration and, in general, development there seems to have been slow. Yet it survived, in some form or another, until 1835, along with most of its archive. That archive was scattered during the Spanish Civil War, but much has been reassembled at Santa Maria de Montserrat or in the Archivo de la Corona de Aragón in Barcelona.Footnote 38

I take as my area the terminium or jurisdictional limit of the city church of Santa Maria, defined in a papal privilege of 978 and mapped by Bolòs and Hurtado (Figure 1).Footnote 39 Using this and the indices of the Catalunya Carolíngia establishes the documentary sample set out in Table 1.Footnote 40

Figure 1 Map of the assigned territory of Santa Maria de Manresa, with locations mentioned in the text shown where known; after Bolòs and Hurtado (see n. 39). © The author.

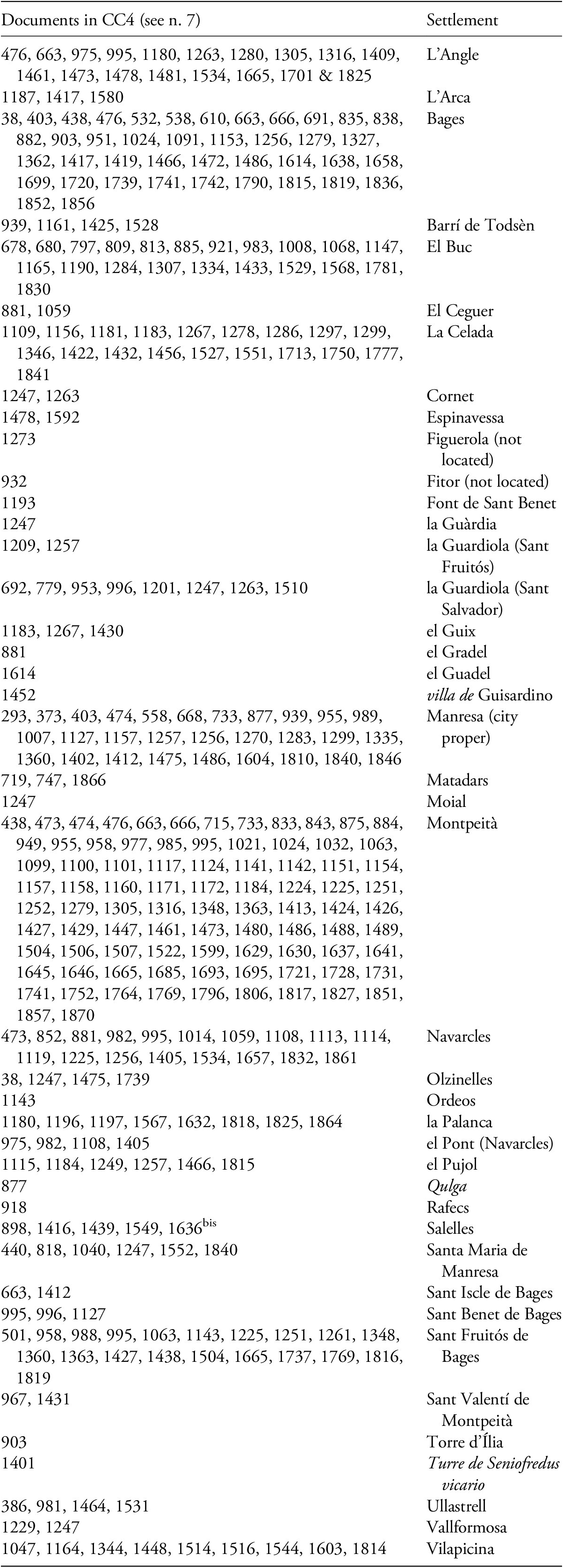

Table 1 Documentary sample from the terminium of Santa Maria de Manresa as found in CC4 (see n. 7).

This naturally involves some duplication, as several documents feature more than one place. The actual number of individual documents from between 898 and 1000 tabulated above includes 253 documents from Sant Benet de Bages, as opposed to fifteen from all other sources. Of these, however, only seventy-six mention Sant Benet or its lands, and a number actually predate the monastery.Footnote 41 Those presumably survive because they were somehow associated with documents that did relate to the monastery’s rights; but some of our evidence has only passed through that filter by association, which gives us some chance of seeing beyond the monastery’s concerns.

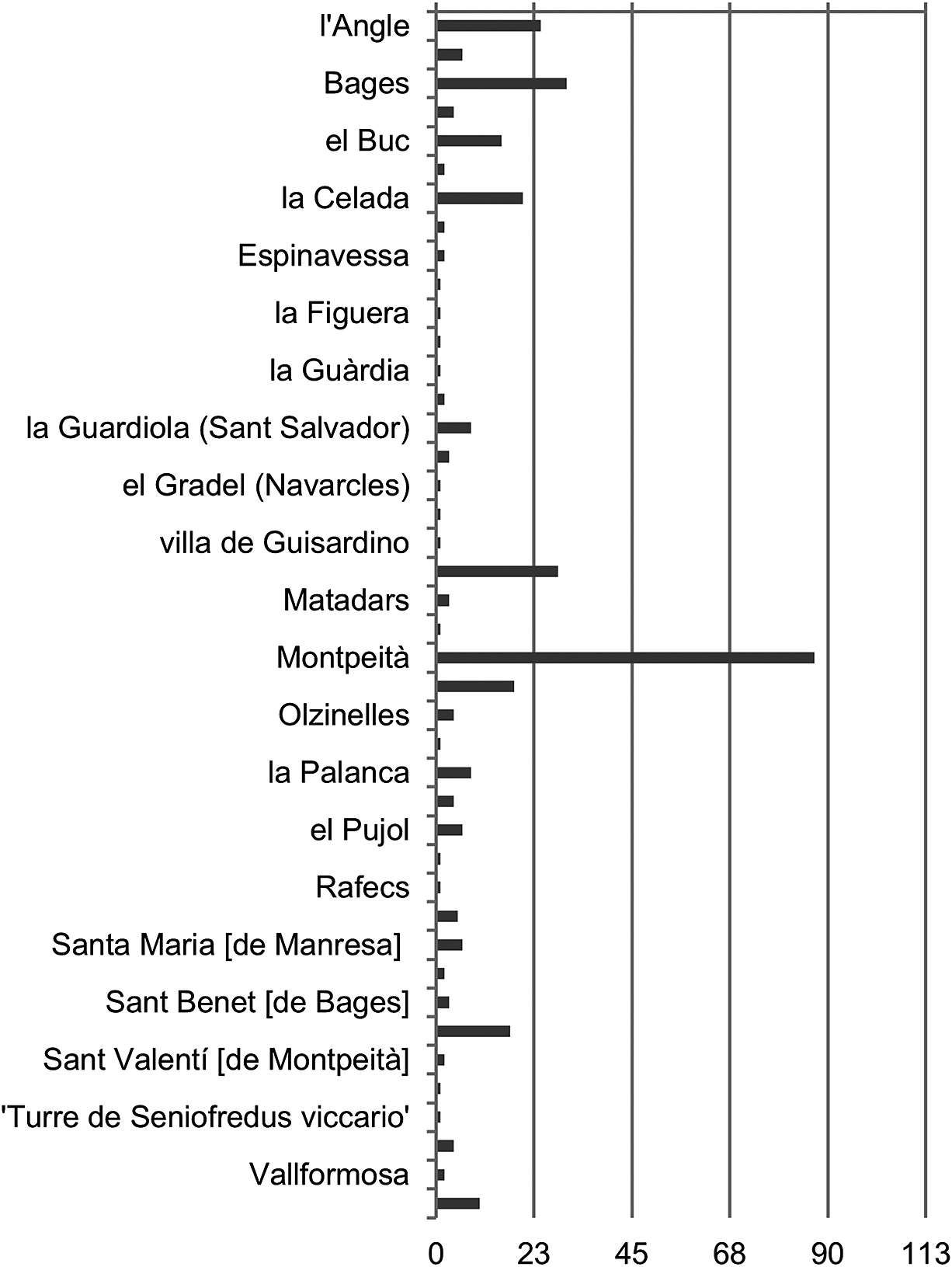

This is also shown by mapping the areas concerned in the documents, which has been done by Bolòs and Hurtado. (Figure 2) While the monastery’s interests are certainly represented in that map, there are substantial foci where the house itself did not, as far as can be seen, hold any substantial property. In fact, although it originated many of the documents, the monastery’s own territory hardly features in the sample. And while Bages, Montpeità and Navarcles loom large in the monastery’s property, none of the other stand-out areas in Figure 2 were particular foci for that property.

Figure 2 Settlement foci in the Manresa documentation. © The author.

A considerable difference is, however, noticeable between the settlement to the north and east of the city, and that to the south and west. The former zone presents a relatively crowded picture, in which communities, albeit quite small ones to judge from the recurrences of witnesses and neighbours, jostled for space and for access to the city. To the south and west, settlements seem sparser and smaller, without the same sense of who the people who usually took part in things were. This may be because there simply were fewer of those people, or because they were not engaged in the land transactions that would have brought them into the records, or because they did not archive the charters with our institutions if they were. Even these latter options, however, suggest an earlier stage of settlement here, in which the inheriting generations who might be selling, rather than clearing, land had not yet arisen. These differences remind us that Manresa itself denoted the edge in terms of the kind of civil operations that generated our source material, and thus demonstrates its peripheral location with respect to both church and government.

Delving more deeply into demography, the sample records 5,264 appearances of persons. That includes many people occurring more than once, but it is still a large number, of whom 807 used a clerical title, in 468 cases a priestly one (presbyter, sacer or sacerdos). These numbers illustrate the lay predominance in the record. They also demonstrate that the area was far from deserted, and while they give us no basis for guesses at local population figures, there is a difference between this landscape and that around the more northerly frontier redoubt of Cardona, where a city population had repeatedly to be re-established over the ninth and tenth century; or even places in other parts of the Iberian frontier, such as Castilian Sepúlveda, whose relatively early fuero or town law code records a similarly small scale community.Footnote 42 This part of the frontier was admittedly governmentally peripheral, but still fairly populous, with connections to central hierarchies through the city.

On the other hand, no documentation survives from what should be the most important institution in this study, the city church of Santa Maria.Footnote 43 It is mentioned here and there in what we have and, as shown below, must have maintained a reasonably numerous staff of clergy; but, in its perilous frontier location, the city was sacked at least once and possibly twice by Muslim armies between 997 and 1003, and this appears to have destroyed the church’s archives.Footnote 44 It was sacked again during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), with similar effects.Footnote 45 We are, therefore, trying metaphorically to see into the next room through a door that is only ajar, and must be thankful that the view is even this good.

Churches and Clergy

None of the churches recorded in the documents of the area show any pre-Romanesque fabric, so their dates can only be suggested from the charter evidence, whose first mentions may considerably postdate their actual establishment.Footnote 46 By that inadequate metric, the oldest was Santa Maria de Manresa itself, whose consecration can probably be dated to 937.Footnote 47 Outside the city, Sant Fruitós de Bages, the most north-easterly, is first recorded in 942, and Sant Iscle de Bages in 950.Footnote 48 No other church is mentioned until after 1000. The pattern thus matches that of settlement, suggesting that churches were established on the city’s ‘homeward’ side early on, but not in the zone between it and the far frontier until after the turn of the millennium and the unexpected collapse of the Andalusī caliphate after 1009.Footnote 49

The ratio of known clergy to known churches in the Manresa area is therefore quite high, suggesting that most churchmen were otherwise organized. The material does not identify clergy as belonging to particular churches, so affiliations can only be deduced by association. Several other features of the evidence deserve note before that is attempted, however.

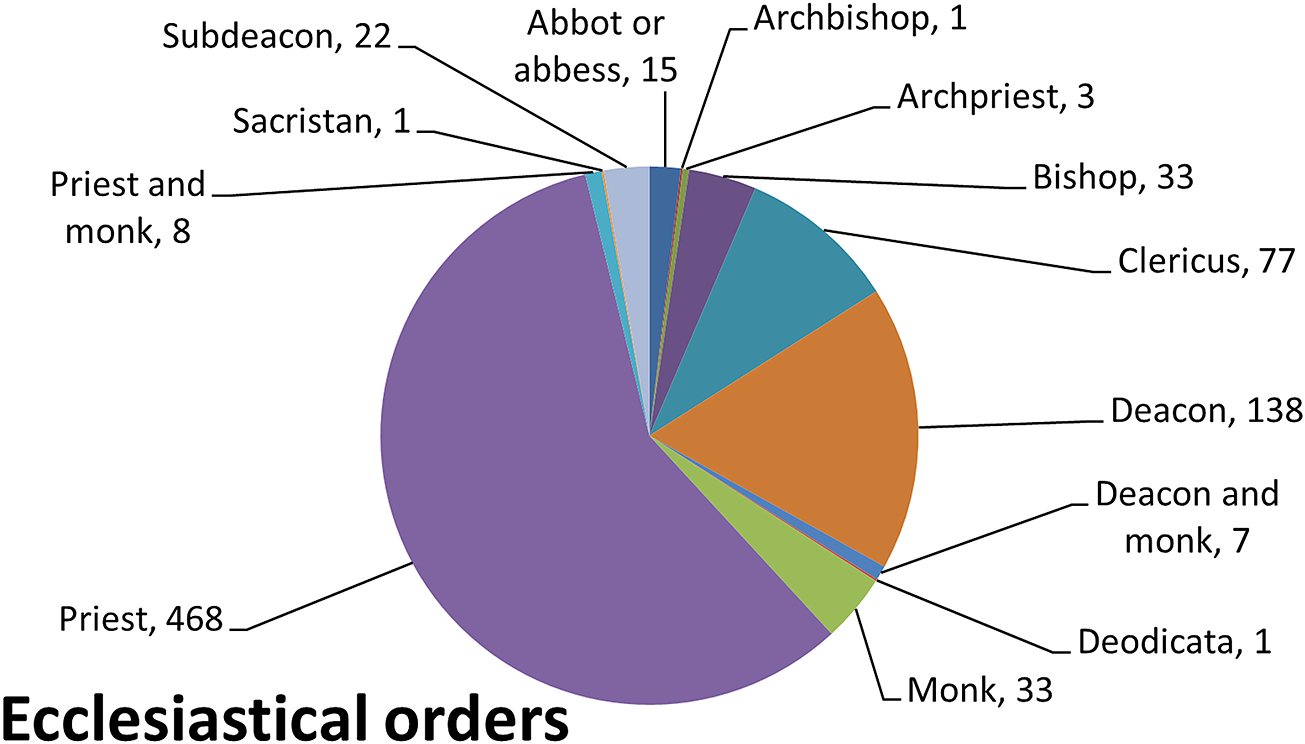

In the first place, the visible structure of the clergy is strongly top-heavy (Figure 3). The material records 476 appearances of priests, as opposed to 145 of deacons, twenty-two of subdeacons and seventy-seven of clerici (various other grades of cleric). Examining these clerical appearances by role suggests a reason for this, which is the pre-eminence of priests as agents of the written record. It is not only that priests were literate; fragmentary evidence, including some non-clerical scribes attested writing charters, suggest that writing was not a clerical monopoly here.Footnote 50 It seems clear from our sample, however, that it was usual and perhaps preferable for a priest to write one’s charter.Footnote 51 This is true in sixty-nine per cent of our documents, with deacons, clerici and subdeacons writing in rough proportion to their overall frequency of occurrence, among a few other scribal dignities, including apparent laymen. This, of course, means that most charters show us at least one priest, but often involve no other churchmen. If we saw priests only when they were actually party to, witnesses of or neighbours in the transaction of land, more than half our count would disappear.

Figure 3 Chart of clerical titles in the documentary sample for Manresa, 898–1000. © The author.

Even then, though, the number of priests would nearly equal appearances of all other ecclesiastical orders combined and be double the next most numerous one (deacons), so there seems genuinely to have been a large proportion of priests in the clergy here (Figure 3). Perhaps this was because, unlike other dignities, it is one which could be held for decades.Footnote 52 It is also possible, however, that priests appear in such numbers because they were the basic unit of ecclesiastical provision. A rural church could be operated by a single priest. He might prefer to have a deacon or two, a doorkeeper and so on; but without a priest, the others would probably not be there.Footnote 53

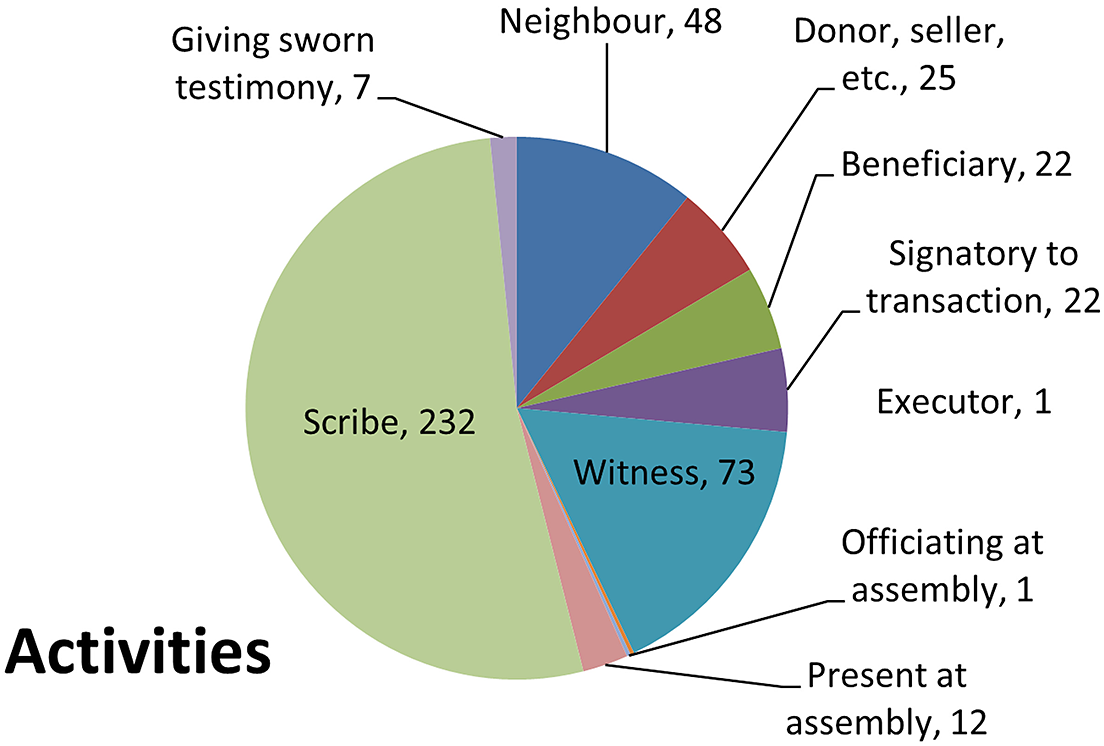

Because of their predominant role in documentary production, however, priests naturally appear first and foremost as scribes, three times more often than as witnesses, their next most commonly recorded activity (Figure 4). They were directly party to transactions much less often. Were the priests working as scribes associated with the communities who thus enlisted them? If so, we would expect consistent appearances of a given priest in a particular area. It transpires, however, that things were not that simple.

Figure 4 Activities of priests in the documentary sample for Manresa, 898–1000. © The author.

Priestly Profiles

Some places do indeed seem to have had associated clergy. The strongest case is Santpedor, in whose territory a settlement called el Buc shows nine priests: firstly Arduin in 957; then, in the period 958–63, one Abo, who would later join Sant Benet de Bages; with some interleaved appearances by one Sendred. In 963, there is a single appearance by Eliseu; then Esteve in 966–87, as well as Sesgut in 970–80 and Julià in 990–1000, with two further priests mentioned later.Footnote 54 They all appear as scribes, and several occur nowhere else. It thus seems reasonable to assume that Santpedor had a steady establishment of one, and perhaps sometimes two, priests, including at least Abo, Esteve and Julià.

It is possible to attempt the same exercise with the two secular churches of Bages, although their proximity to each other adds to the problems caused by their closeness to the monastery. Montpeità also offers a plausible sequence, although complicated by the fact that almost all the priests involved, and all the scribes, became monks at Sant Benet and were involved with the house before joining it. There seems to have been some kind of church at Montpeità, but its ministry was being delivered by priests connected to Sant Benet.Footnote 55 These two to four churches supply the only cases where the presence of established clergy is even this plausible.

Indeed, when the exercise is performed within the city limits of Manresa, the result is quite different: nineteen priests in total, of whom twelve wrote documents, none more than one each.Footnote 56 That suggests that many priests were available in the city. If Santa Maria’s archive had survived, these men might be more clearly recorded; but, as it is, they might either be very local to the places with which their appearances are associated, or, conversely, associated with the city church rather than any specific locale outside.

The latter suggestion can be supported by looking at some specific priests. A problem is that those associated with the monastery appear most in our record, not because the monastery employed them, but because they apparently deposited their documents in its archive. Two in particular have to be ignored: Baldomar, one of the confusing presences at Montpeità, apparently himself from Balsareny to the north-west, but not clearly the priest there; and the slightly older Badeleu, whose origins are obscure. Both had comital connections; both became stalwart, if perhaps retired, members of the monastic community at Sant Benet; and both fail to help us with this question, because the material they deposited at the monastery had more to do with their landholding interests than their pastoral roles.Footnote 57 A more helpful example is Sunyer, who wrote, among many other documents, the monastery’s 972 endowment.Footnote 58 His hand is recognizable in extant autograph documents, and he spelled his name unusually (Sunierius), which helps identify him in others.Footnote 59 Despite his presence in their archive, and an evidently important role there, he does not seem to have been either a monk or a client of Sant Benet’s founders; he is never entitled monachus and does not otherwise appear with Sal·la’s family.

Sunyer is not the only such priest. One Esclúa is attested between 982 and 1000 in seven documents.Footnote 60 Two late ones concern property at Montpeità, but the others do not. One deals with Sant Fruitós de Bages and one with la Palanca, which were close by, but another is focused far off to the north at l’Arca. Two more tie him to Manresa itself. An explanation for this diffuse focus is that interests were coming to the priest rather than the other way round, and the obvious locus is the city church. Whether transactors knew Esclúa because he sometimes ministered to their areas, or whether he was simply on duty as notary when they came into town to have their transaction solemnized, cannot be known. Similarly unclear is whether Sunyer was chosen to write prestigious documents because he was a close connection of someone important, or because his importance was institutional, but the town is likely to have been the significant location in all cases.

It is perhaps also possible to see a process of change, from provision orchestrated out of Santa Maria, to ministry by a fixed incumbent of a rural church. At la Celada, close to the city, seven priests occur, three of them more than once, all as scribes.Footnote 61 The scribes overlap, and while a sequence is possible to construct, it is broken, with one Eldovigi appearing discontinuously and much scribal work being done by a deacon, Elies. All the priests appear in connection with other places, as does Elies. This looks like a collegiate operation in which duty at or concerning la Celada fell to outside clergy, presumably from the city, on some kind of rotation. After a while, however, only one priest appears, Llobet. He also appears elsewhere, but between 984 and 997, he was the priest who wrote documents about la Celada. Had he been assigned there on an ongoing basis? La Celada never acquired its own church, but it may have been given its own part-time priest.

Catalonia and Elsewhere

So far, these pre-Catalan priests have been considered in splendid isolation, but they were part of a wider church, indeed of a church much affected by the eighth- to ninth-century Carolingian conquest of the area and its alterations, as some argue, to religious, intellectual and scribal culture.Footnote 62 Moreover, a recent store of scholarship on local priests of this era makes possible a comparison between the Catalan material and findings from elsewhere.Footnote 63

Many contributors to this recent scholarship have been concerned with the question of priests’ learned apparatus, in the form of education and books.Footnote 64 Michel Zimmermann’s expansive study of the Catalan evidence reveals a priesthood with something like a standard equipment of texts.Footnote 65 This picture is harder to get in Manresa, because it derives principally from church consecrations and priests’ wills, neither of which survive in any number through Sant Benet. The observance by our scribes of what, it has been suggested, was a Carolingian modification of local charter formularies, however, implies that that was enforced here too (although with a sample dominated by documents from after 940: we see the results only several generations later).Footnote 66 This may also explain some negative features of our evidence, which studies of other areas make ours seem peculiar. There are, for example, no families of clergy in the Manresa evidence, though these were common in Italy and not unknown elsewhere. Even away from the frontier, there seem to be only occasional uncle-nephew successions, with nothing like the clerical dynasties visible in Tuscany.Footnote 67 Likewise, there is almost no record (here or in Catalonia more widely) of priests owning their own churches. The sole case known to me, not from Manresa, involves a priest who was appointed by someone else (the count of Urgell, to the north of our area, at his chief castle’s church).Footnote 68

Instead, the weight of power in the appointment of priests seems to have lain with bishops.Footnote 69 The possibility that such priests were trained at the cathedrals also raises the likelihood of episcopal preferment. This may be why the counts of Urgell, where more direct comital control of appointment is apparent, came in for occasional critique in their cathedral’s documentation.Footnote 70 If Urgell is the exception that proves the rule, then the silence of the quite voluminous evidence perhaps suggests this was a church established on fairly canonical lines, arguably even more so than some closer to the core. One might suppose that a frontier church would be unguided and anarchic, but the process of establishment visible here seems to have set things up as reformers would have wanted.

One place, however, where the wider scholarship does find an echo in Catalonia in general, and Manresa specifically, is the idea of superior churches below cathedral rank. The model of the early English minster seems relevant here, even if disputed. This proposes a pastoral structure in the early English church centred on large, collegiate churches, each covering a wide area in which, locally, there might only be chapels or outdoor locations of worship.Footnote 71 In this respect, it is not unlike the Italian system of plebes or baptismal churches, with plural priests, each holding rights over smaller, more local churches with fewer and more dependent clergy.Footnote 72 The newer English system naturally had fewer churches, and over the tenth to twelfth centuries, it is argued, the establishment of local churches broke the early minster territories up into parishes that largely still exist.Footnote 73

This model, and the less disputed Italian structure, have obvious resemblances to the situation outlined in Manresa, with Santa Maria as minster or plebs. There are, nonetheless, four important differences. Firstly, Santa Maria seems to have been quite a large establishment, functionally a delegated episcopal outpost that furnished clergy for pastoral operations near and far, although there is no sign that it had any kind of canonry. It may be unhelpful to compare Santa Maria with any but the largest minsters, or with any plebs. Secondly, Santa Maria sat in a town. The size of that town is a mystery, although it had at least one suburb (Barri de Todsèn), but Santa Maria was not its only component, or even its only church, and was not therefore a settlement centre in its own right, like some English minsters.Footnote 74 Thirdly, both in Blair’s English hypothesis and in the Italian layout of plebes, the system was stable and not intended to develop, whereas there are signs here, both in the priestly provision and the subsequent parish map, that part of the role of Santa Maria de Manresa and its clergy was to generate new parish foci. Fourthly, in the minster hypothesis, as in the Italian context, there was little difference between a collegiate church of priests and a monastery.Footnote 75 In the Catalan counties, however, those institutions had different jobs.Footnote 76 Sant Benet de Bages may have largely drawn its community from among the pastoral clergy, but the monastery itself had no parrochia (parish) and no visible ministry outside its own confines (except, perhaps, at Montpeità). Everywhere else’s ministry was handled from the city.

All this offers another, more or less Carolingian, micro-Christianity that might be added to our bank of comparative studies of the early medieval church, but there was something distinctively peripheral about priestly provision around, and especially beyond, Manresa.Footnote 77 Firstly, it was more thinly churched than most places, except the mission ground of early England; and priests from a large, but vulnerable, sub-cathedral in an insufficiently fortified town did much of the work. Secondly, the visible churches around Santa Maria de Manresa, even behind the frontier from it, seem to have been small; none of them except the monastic Sant Benet seem to have had more than two priests or other clergy visibly assigned, although plenty more priests can be seen. While it is possible that the lack of detectable dynastic or aristocratic control of churches or priestly office reflected the rigour of Carolingian reform in the area, the fact that what reformers would have considered failings are easier to find further east and north also points to the small size and newness of churches here; there were probably just not sufficient clergy established long enough to have built such structures of patronage or reproduction. As in England, albeit in a different context, we are seeing a church forming at its own edge.

Conclusion

Catalonia – and specifically the Manresa area – remained a frontier. The destruction of Santa Maria around the year 1000 shows this clearly, but even without it, our limited map of church provision on this periphery underlines Manresa’s pivotal position. Beyond it were communities cut off by stretches of no-man’s land (and considerable geographical obstacles); behind it were communities in development, both secular and pastoral, as well as a coalescing monastery.

In standard accounts of the extension of control on the Catalan frontier, monasteries, such as that one, perform a central function as colonizers of wasteland and sponsors of settlement, and indeed churches. Bishoprics are given a lesser role, more reactive to demands from settlers than actually responsible for settlement (though bishops are in fact documented awarding frontier development concessions).Footnote 78 Frontier churches like Santa Maria de Manresa are, however, absent from such accounts. These churches, collegial or otherwise, may also have been sponsors of development, settlement and pastoral provision, which would, when the military context allowed, be bases for the next steps in the return of organized Christianity to this area, and perhaps others like it elsewhere.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0424208424000330.