1. Introduction

Willingness to give is often influenced by one’s views about the causes of the need (i.e., Cozzarelli et al., Reference Cozzarelli, Wilkinson and Tagler2001; Davidai, Reference Davidai2022; Koo et al., Reference Koo, Piff and Shariff2023; Piff et al., Reference Piff, Wiwad, Robinson, Aknin, Mercier and Shariff2020). Hence, giving to a person in need may depend on one’s attitude and beliefs regarding the cause of need. At the same time, people often intentionally avoid information (Golman et al., Reference Golman, Hagmann and Loewenstein2017; Hertwig and Engel, Reference Hertwig and Engel2016; Serra-Garcia and Szech, Reference Serra-Garcia and Szech2019). Terms such as ‘deliberate ignorance’, ‘active information avoidance’, and ‘information gap’ are often used to describe the behavior of agents who are aware of the availability of relevant and important information, yet nevertheless choose not to obtain it. In the present research, we explore the role of entitlement on the decision to pursue information.

Whereas previous research has shown that people who are entitled are less willing to share or give to charity (i.e., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004), we ask whether entitlement may lead individuals to pursue information about a helping situation. Earlier research that focused on attitude change and explored willingness to pursue counter-attitudinal information may provide a clue to the possible role of entitlement in this context (Albarracín and Mitchell, Reference Albarracín and Mitchell2004). This research showed that people who are confident in their ability to defend their attitudes are more likely to pursue information that counters their attitudes. Presumably, they are less worried about regret associated with the realization that they were wrong. Ironically, as a result, they are more likely to change their attitude. In a similar vein, a sense of entitlement may lessen the distress that would otherwise arise when encountering information about a needy person who could place demands on their resources. People with a high sense of entitlement may be less worried about experiencing such distress and hence more likely to pursue information about the needy. We elaborate on this shortly.

At a broader level, the present research contributes to our understanding of entitlement. For one, although the literature has identified many downstream consequences of entitlement such as unrealistic expectations (Grubbs and Exline, Reference Grubbs and Exline2016), anger when expectations are not met (Zitek and Jordan, Reference Zitek and Jordan2021), and unethical behavior (Schurr and Ritov, Reference Schurr and Ritov2016), here we seek to establish a novel link between entitlement and the pursuit of information. In doing so, we also seek to show that entitlement can also be associated with more, not less, helping behavior. At the same time, we also seek to contribute to the literature on deliberate ignorance and avoiding information. While this literature has already examined how decision makers often avoid knowing the consequences of how their choices affect others in need (Hertwig and Engel, Reference Hertwig and Engel2021; Vu et al., Reference Vu, Soraperra, Leib, van der Weele and Shalvi2023), the present research—on the flip side—explores how decision makers pursue information about the a priori reasons why others are in need.

2. Information seeking and self-image

While people often seek non-instrumental information out of curiosity (Fath et al., Reference Fath, Larrick and Soll2023; Litovskya et al., Reference Litovsky, Loewenstein, Horn and Olivola2022), seeking information about others can increase the empathy we feel toward them, and it can also affect one’s own self-image (Golman and Loewenstein, Reference Golman and Loewenstein2018; Golman et al., Reference Golman, Loewenstein, Molnar and Saccardo2021a, Reference Golman, Gurney and Loewenstein2021b). In particular, if we seek information about another’s need but then do nothing about it, such information seeking could affect our self-image, especially since maintaining one’s self-image as a moral person is a major determinant of social behavior in various situations (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Mitchell and Hannah2015). Indeed, our desire to maintain a positive self-image is so strong that we are vulnerable to self-deception just to preserve it (e.g., Bazerman and Banaji, Reference Bazerman and Banaji2004; Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, Reference Bazerman and Tenbrunsel2011; Bereby-Meyer and Shalvi, Reference Bereby-Meyer and Shalvi2015; Gneezy et al., Reference Gneezy, Saccardo, Serra-Garcia and van Veldhuizen2020; Grossman, Reference Grossman2014; Pittarello et al., Reference Pittarello, Leib, Gordon-Hecker and Shalvi2015; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Tenbrunsel and Bazerman2019; Shalvi et al., Reference Shalvi, Dana, Handgraaf and De Dreu2011). Thus, avoiding information can likewise preserve our self-image and set the stage for making a self-interested choice instead of a morally superior one (Dana et al., Reference Dana, Weber and Kuang2007; Vu et al., Reference Vu, Soraperra, Leib, van der Weele and Shalvi2023). In fact, consistent with our explanation, people who actively pursue information about the consequences of their choice for affected others are more generous than those who were passively exposed to the same information (Grossman and van der Weele, Reference Grossman and Van der Weele2017).

Along these lines, the present research seeks to explore how people may tend to avoid information about a person in need. Previous research has explored how people avoid information about the consequences of their decisions. The present research seeks to explore when people pursue information about a priori factors such as the reasons or circumstances that led another person to be in need (i.e., ‘Were the circumstances due to “bad luck” vs. failure to pursue income opportunities?’). More specifically, when the information regarding the cause of need is not initially available, we ask decision makers who are in a position to help whether they would like to find out why the person is in need; we then probe how the decision to pursue this information is related to the decision maker’s decision to make a donation. We test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Decision makers who pursue information about the cause of the person’s need are more likely to give resources than decision makers who chose not pursue this information.

3. Moderating role of entitlement

If avoidance of information is driven primarily by the need to maintain a positive self-image, it becomes necessary to understand how one’s behavioral choices affect one’s self-image. We note, first, that the effect of one’s choices on one’s moral self-image depends not only on the choice itself, but also on the relevant worldview of the decision maker. A behavioral choice that is incompatible with one’s beliefs is more likely to challenge one’s moral self-image than a compatible choice. For instance, individuals who view generosity as a core moral value but act selfishly are likely to experience guilt and a diminished moral self-image. In contrast, those who do not regard generosity as important may feel little or no guilt when they choose not to give. Therefore, when it is possible to overlook information about the effect of one’s behavior, people who anticipate guilt for a selfish choice are more likely to avoid such information.

An important aspect of one’s worldview is perceived entitlement, a pervasive sense that one deserves more than others, an expectation of special privileges over others. Although extensive research shows that a high sense of entitlement can lead to a host of negative behaviors such as selfishness (i.e., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004) and unethical behavior (Schurr and Ritov, Reference Schurr and Ritov2016), some studies highlight the complexity of the entitlement effects (i.e., Lange et al., Reference Lange, Redford and Crusius2019; Lessard et al., Reference Lessard, Greenberger, Chen and Farruggia2011). Here, we posit that one’s sense of entitlement can form a basis of one’s self-image. More specifically, we ask whether entitlement may insulate people against guilt feelings. If individuals who feel generally entitled do not experience guilt about being better off than others (because they think they deserve it), they should not worry much about learning of needy others who might be helped by them. For example, if the decision maker considers herself entitled to her own resources more than others who are less endowed, learning about those others is not likely to evoke guilt and harm her self-image, regardless of whether she chooses to help them or not. Consequently, she would not worry about the mental risk of obtaining this information. Our reasoning here is similar to that proposed by Albarracín and Mitchell (Reference Albarracín and Mitchell2004) concerning the insulating effect of defensive confidence against revealing counter-attitudinal information. This pattern may reflect a broader principle of when information is sought: the less threatening the potential implications of new information, the greater one’s willingness to acquire it.

In order to explore the role of entitlement in this context, we propose to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: The more entitled a potential giver considers herself, the more likely she is to pursue information regarding the cause of the target’s lack of resources.

People who seek information may feel more responsible for what they learn from it. Thus, deliberately leaning about the need of others, relative to randomly obtaining this information, may lead to increased willingness to help. Whereas the entitlement literature suggests that those who are high in entitlement may become selfish and unwilling to help (i.e., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004), adding the possibility to pursue information before choosing whether to help can ironically increase helping behavior, especially among those who are high in entitlement. This would suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: When obtaining the information regarding the cause of the target’s lack of resources requires active choice, entitled individuals would be more likely to pursue the information and more likely to give to the target than when this information is presented openly.

4. Overview

Four studies explore the above questions. Study 1 probes for potential evidence of Hypotheses 1 and 2 by presenting participants with a scenario about a person in need to whom they can give, followed by an option to pursue—or avoid—information about the cause of the person’s need. Study 1 also measures entitlement after these decisions. Study 2 also probes for the hypothesized effects, but in a design where entitlement is manipulated prior to the donation and information pursuit decisions. Study 3 examines whether the effects obtained in Studies 1 and 2 critically depend on the order of the activities (information search and giving choice). Finally, Study 4 instantiates the hypothesized effects by capturing real giving behavior in a dictator game, while also capturing the decision to pursue information prior to making a donation. The data files and questionnaires, including coding of the variables for all four studies, can be found at https://osf.io/jw6zx. The sample sizes in all studies were determined so that each condition will include approximately 100 subjectsFootnote 1.

5. Study 1: The decision to give and post-measures of entitlement

Study 1 prompts participants to consider a plea for help from a person in need. A link to more information about this person is presented in the appeal. This study probes whether respondents would be likely to follow the link to obtain more information about the cause of this person’s need.

5.1. Participants

A total of 200 participants (119 men, 72 women, 9 unspecified) were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT).

5.2. Procedure

In a within-participants design, all participants first read a plea for help:

Imagine you received an appeal to help a person in dire need. You are familiar with the organization that sent the appeal and have no doubts about its authenticity. However, you do not know how the needy person came to be in this situation. In particular, you do not know if he was responsible for being in this situation, or if it was simply the result of pure bad luck.

Next, participants were asked whether they would make a contribution (i.e., ‘Would you contribute any money to help the person?’ (Yes/No)), and, if yes, how much money would they contribute (i.e., $ amount). No guidelines were provided regarding the amount to be contributed or the hypothetical financial situation of the contributor. On the next screen, participants were asked to imagine that they could find out what chain of events led to this person’s present circumstances by simply clicking a link included in the appeal and asked, ‘Would you take the time to check this information?’ (Yes/No).

In order to examine whether the choice to obtain information had an instrumental value, after making this choice all respondents were asked to consider two situations, in counterbalanced order. They were asked to assume they followed the link and learned that (1) the person in need had several opportunities to improve his financial situation but failed to take advantage of those opportunities (i.e., person is to blame) and then (2) unfortunate circumstances provided the person in need no opportunities to improve his financial situation (i.e., circumstance is to blame). For each situation, participants were asked whether they would contribute any money to help the person in need and, if so, how much.

Finally, participants were asked to complete the Psychological Entitlement Scale (PES) rating nine statements (e.g., ‘I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others’) on a seven-point scale. Concern for the needy and general beliefs about the causes of poverty were also elicited. The poverty attribution measure reflects the degree to which the respondent attributes poverty to dispositional rather than situational factors. While dispositional attribution of poverty may diminish willingness to help the poor, we asked whether holding such a belief may have an insulating effect against a potentially distressful effect of pursuing information, similar to the effect of entitlement. The responses to those measures are reported in the Supplementary Material.

5.3. Results

Because earlier research (Dickert et al., Reference Dickert, Sagara and Slovic2011) showed that the initial decision process to give is distinct from the ancillary decision process determining the amount to give, we focus on the initial decision. Of the 200 participants who completed the survey, 56.5% (n = 113) decided to give to the needy person. Examining the likelihood of pursuing the additional information provided in the link, 70.5% of participants (n = 141) said they would pursue the information. However, in line with Hypothesis 1, the decision to give was significantly related to willingness to check the link: of those who opted to pursue the information, 62.4% indicated they would help the person in need; of those would not pursue the information, only 42.4% indicated they would make a contribution (χ 2 (1, N = 200) = 6.796, p = .009). Of the respondents who would pursue the information, 51.1% said they would help only if the person was needy because of bad luck, whereas among the respondents who would avoid the information, only 25.4% differentiated in this way between the two cases. The difference between the two proportions is significant (χ 2 (2, N = 200) = 11.370, p = .003), suggesting that participants pursued information for its instrumental value.

Moreover, although we made no prediction about giving amounts, we did examine the amounts of contributions by those participants who said they would contribute to the needy person before knowing the cause of need according to whether or not they pursued information; the differences were non-significant. Participants who would pursue the additional information contributed similar amounts to those who would not pursue the information (M = 33.98, SD = 41.197 and M = 31.96, SD = 25.856, respectively; t(111) = .222, p = .825, Cohen’s d = .050).

In accordance with Hypothesis 2, we next probed whether participants who revealed the information had higher levels of entitlement than those who avoided it. To do this, we computed a single entitlement score by averaging the responses on the entitlement scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .920), and in line with the hypothesis, entitlement scores differed between those who said they would follow the link and those who would avoid it. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, participants who would pursue the additional information felt more entitled (M = 3.126, SD = 1.359) than participants who would avoid checking the information in the link (M = 2.363, SD = 1.131; t(198) = 3.792, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .588).

6. Study 2: Manipulating entitlement

Study 2 sought to replicate the support for Hypotheses 1 and 2 found in Study 1. Study 2 also sought to further explore the link between feeling a sense of entitlement and information seeking, by manipulating entitlement at the onset rather than measuring entitlement after the decisions. Study 2 used the identical design of Study 1, with a single change: entitlement was manipulated using a preliminary task.

6.1. Participants

A total of 210 participants (99 men, 110 women, 1 unspecified) were recruited from AMT.

6.2. Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two entitlement conditions (based on Zitek and Vincent, Reference Zitek and Vincent2015). They were asked to write three reasons why they should (High Entitlement) or should not (Low Entitlement) feel more entitled than others. Following this, as a manipulation check, participants filled out the PES. The rest of the questionnaire was identical to that of Study 1. We note that unlike Study 1, in this study, entitlement was manipulated and measured before presenting the donation opportunity and eliciting choices.

6.3. Results

Of the 210 participants who completed the survey, 67.1% (n = 140) indicated they would give some money to the needy person. A substantial majority –71.9% of respondents (n = 151)—indicated they would take the time to follow the link. As in Study 1, we again found support for Hypothesis 1, as giving was significantly related to willingness to check the link: 75.5% of those who said they would follow the link in order to obtain more information indicated earlier that they would contribute money, while only 45.8% of those who indicated they would not look for the information contributed money (χ 2 (1, N = 210) = 17.001, p < .001). Of the respondents who would pursue the information, 50.3% said they would help only if the person was needy because of bad luck, whereas among the respondents who would avoid the information, only 13.6% differentiated between the two cases. The difference between the two proportions is highly significant (χ 2 (2, N = 210) = 26.339, p < .001). However, as in Study 1, participants who would pursue the additional information did not significantly contribute higher amounts than those who would not pursue the information (M = 46.03, SD = 105.841 and M = 22.42, SD = 23.425, respectively; t(138) = 1.128, p = .261, Cohen’s d = .245).

Finally, examining the role of entitlement, we note first that the entitlement manipulation proved effective: we computed a single entitlement score (Cronbach’s alpha = .937) and found that participants in the High Entitlement condition (M = 3.475, SD = 1.700) scored higher on this measure than participants in the Low Entitlement condition (M = 2.834, SD = 1.761, t(208) = 2.677, p = .008, Cohen’s d = .370). This allows us to treat entitlement as a dichotomous between-subject measure, with participants randomly assigned to one of the two entitlement levels. Importantly, while entitlement categorization differed from Study 1, the effect of entitlement replicated the effect found in Study 1, again supporting Hypothesis 2: 81.2% of the participants in the High Entitlement condition indicated they would open the link, while only 63.3% of participants in the Low Entitlement condition indicated so (χ 2(1, N = 210) = 8.301, p = .004). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported both in Study1, where entitlement levels were measured after the decision, and in Study 2, where entitlement was manipulated prior to the decisions.

7. Study 3: Pursuing information before or after giving decision

While Studies 1 and 2 provided an opportunity to pursue information after the giving decision, Study 3 counterbalances whether participants are asked about the hypothetical opportunity to pursue more information about a person in need either before or after their giving decision. Moreover, we also seek to establish whether, among those who pursue information, givers exhibit higher entitlement scores than non-givers. Preregistration can be found at https://aspredicted.org/5f8w-fdvz.pdf.

7.1. Participants

A total of 203 participants (124 men, 78 women, 1 unspecified) were recruited from AMT.

7.2. Procedure

Two between-participants conditions varied the order of the questions about revealing the information and choosing to give. In the Giving-First condition, participants first read a plea for help:

Imagine you received an appeal to help a person in dire need. You are familiar with the organization that sent the appeal and have no doubts about its authenticity. However, you do not know how the needy person came to be in this situation. In particular, you do not know if he was responsible for being in this situation, or if it was simply the result of pure bad luck.

Next, participants were asked whether they would make a contribution (i.e., ‘Would you contribute any money to help the person?’ (Yes/No)), and, if yes, how much money would they contribute (i.e., $ amount). On the next screen, participants were asked to imagine that they could find out what chain of events led to this person’s present circumstances by simply clicking a link included in the appeal and asked, ‘Would you take the time to check this information?’ (Yes/No). In the second, Information-First condition, the order of the two screens was reversed, such that respondents were first asked about their willingness to pursue the information and then they were asked for their willingness to contribute. Finally, participants were asked to complete the PES rating nine statements (e.g., ‘I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others’) on a seven-point scale.

7.3. Results

Of the 203 participants who completed the survey, 71.9% (n = 146) decided to give to the needy person and 70.5% (n = 141) said they would pursue the information. Importantly, the ordering of these two counterbalanced questions (i.e., Give-First condition vs. Information-First condition) did not significantly affect giving (77.0% vs. 67.6% Give-First and Information-First, respectively, χ 2(1, N = 202) = 2.204, p = .138), or pursuing information (76.0% vs. 75.5% Give-First and Information-First, respectively, χ 2 (1, N = 202) = .007, p = .933).

Once again, consistent with Hypothesis 1, the decision to give was significantly related to willingness to pursue information. Across the two order conditions, 82.4% of those who opted to pursue information indicated they would give to the person in need, compared to only 40.8% of those who chose not to pursue the information (χ 2(1, N = 202) = 31.957, p < .001). The link between giving to the needy person and pursuing the information about the cause of need was significant in both conditions (84.2% vs. 54.2% givers, χ 2 (1, N = 100) = 9.296, p = .002, in the Giving-First condition; 80.5% vs. 28.0% givers, χ 2 (1, N = 102) = 23.785, p < .001, in the Information-First condition).

Once a decision to give was reached, pursuing information did not significantly predict the actual amount of contribution. Among participants who would choose to give, the difference between the amounts given by participants who would pursue the additional information and those given by participants who would not pursue the information was not significant (M = 1994.669, SD = 18649.020 and M = 27.100, SD = 29.57221, respectively; t(133) = .470, p = .639, Cohen’s d = .114). As the standard deviations suggest, large outliers may have affected this result. To correct for this, we log-transformed the amounts and compared the log-transformed means of the two groups. The difference between the two groups still did not reach a significant level (M = 1.521, SD = .822, and M = 1.204, SD = .463, respectively; t(133) = 1.674, p = .097, Cohen’s d = .408).

To test Hypothesis 2, we next probed whether participants who revealed information had higher levels of entitlement than those who avoided information. To do this, we computed, as in Study 1, a single entitlement score by averaging the responses on the entitlement scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .956). As in the previous studies, entitlement scores differed between those who said they would pursue additional information and those who would avoid it. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, across the two conditions, participants who pursued additional information felt more entitled (M = 3.708, SD = 1.631) than participants who avoided the additional information (M = 2.898, SD = 1.301).

An ANOVA of entitlement scores by condition (i.e., Give-First vs. Information-First) and the choice to pursue information yielded a significant effect of information pursuit (F(1,199) = 9.464, p = .002, ηp2 = .045). The effect of condition was not significant (F(1,199) = 004, p = .949, ηp2 = .002). Including an interaction term in the model did not substantially change the results, and the interaction itself was not significant (F(1,198) = 016, p = .898, ηp2 < .001).

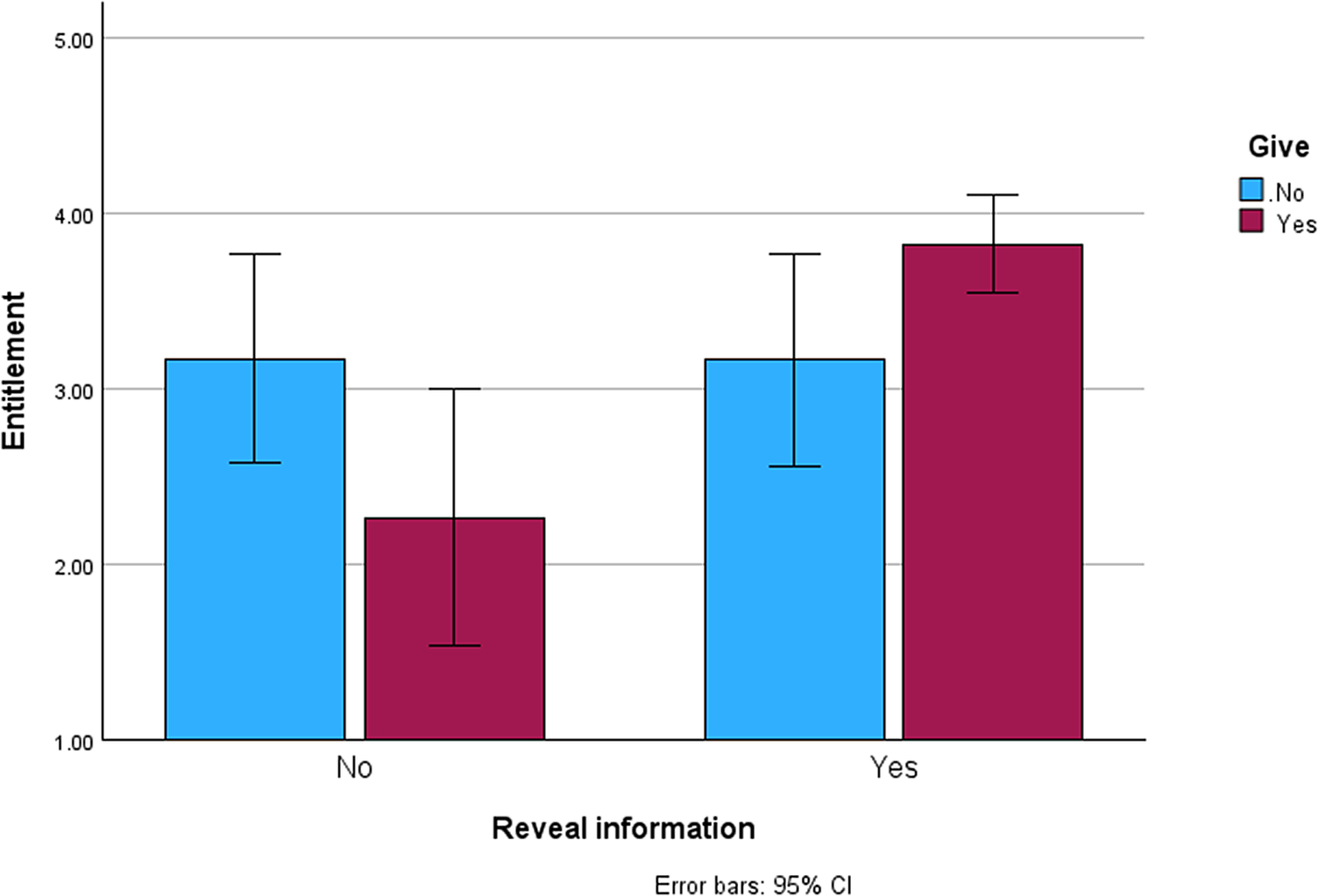

Hypothesis 3 pertains to the link between giving, pursuing information, and a sense of entitlement. An ANOVA predicting entitlement scores by the three main factors: giving decision, pursuit of information, and condition (i.e., Give-First vs. Information-First), reveals only a significant main effect of pursuing information (F(1,198) = 6.643, p = .011, ηp2 = .032). The effect of giving did not approach a significance level (F(1,198) = .357, p = .551, ηp2 = .002), and neither did the effect of the order condition (F(1,198) = .017, p = .897, ηp2 < .001). A full factorial model including all interactions revealed a significant interaction between pursuing information and giving (F(1,194) = 7.117, p = .008, ηp2 = .035). The interaction is presented in Figure 1. As illustrated, among participants who said they would pursue the information, givers were higher in entitlement than non-givers. On the flip side, among participants who would not pursue the information, givers were lower in entitlement than non-givers. No other effects approached a significance level. And, once again, the Give-First vs. Information-First conditions did not significantly affect entitlement, nor did they interact with any other factor.

Figure 1 Mean entitlement of respondents who revealed/did not reveal the information, separately for those who donated and those who did not donate.

8. Study 4: Real giving

Whereas Studies 1, 2, and 3 utilize vignette scenarios to establish the effect, Study 4 seeks to instantiate the effect with real giving behavior. To this end, we examine giving in a dictator game. In the initial stage of the experiment, some participants received a bonus payment, some did not. The reason for participants not receiving the bonus could be either their poor performance on an effort-based task (i.e., internal cause) or their losing a lottery draw (i.e., external cause). In the second stage, a dictator game is played, where participants who received the bonus were ostensibly randomly matched with participants who did not receive the bonus. The dictators either knew why their matched partners did not receive the bonus (i.e., Overt condition) or could find out (i.e., Concealed condition). More relevant to our hypotheses, we examined whether the dictators in the Concealed condition would be interested in pursuing the reason why the partner did not receive a bonus, and how this information, or its deliberate absence, affects their giving decisions. Earlier research showed that allocations in dictator games are more generous for recipients who are deemed more deserving (e.g., Eckel and Grossman, Reference Eckel and Grossman1996; Engel, Reference Engel2011). Hence, the information concerning the reason for the recipient’s lack of bonus would likely be considered relevant by the allocator. Furthermore, because the option to obtain the missing information was presented before the dictators made their giving decisions, this design allows us to test Hypothesis 3 by examining the effect of entitlement on generosity under these conditions.

8.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from AMT. Those who did not complete the initial task were not allowed to continue the experiment. The final sample is composed of eight hundred and sixty two participants (422 men, 438 women, 2 unspecified) who completed the study.

8.2. Procedure

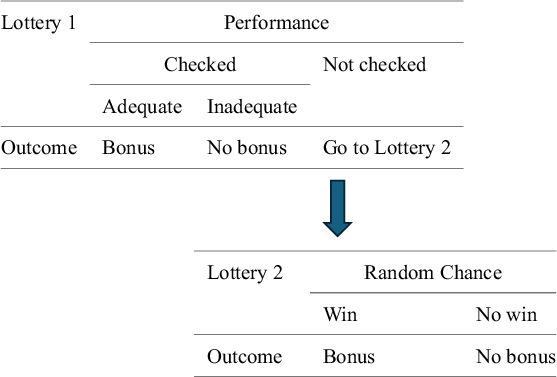

At the initial stage, all participants performed a sequence of tasks (i.e., count the number of N’s in a given line of random letters) and were informed that they may receive an 80¢ bonus, depending on their work. The process of determining the bonus was explained as follows:

First, a lottery will determine if your outcome will be based on your performance or not. If you win this lottery, the program will check your performance level and you will receive a bonus of 80¢ if your performance level is equal or higher than the average of participants in the previous session. If your performance is lower than average you will not receive any bonus. The participants who are not assigned to the performance condition will enter a second lottery. The second lottery will randomly determine who receives a bonus of 80¢, regardless of the performance on the initial task.

Two comprehension questions checked respondents’ understanding of the procedure and its implications (‘Is it possible to receive the bonus, even if performance level is low?’; ‘Would all participants with high performance level end up receiving the bonus?’). Respondents who failed to answer correctly the two questions did not proceed to the main experiment.

After a brief pause, in the second stage, all participants were informed that they received the bonus and by what qualification (i.e., their performance on the task vs winning the second lottery). Respondents then read that they would be randomly and anonymously matched in pairs—and, importantly, that their matched partner did not receive the bonus.

Cause of Respondent’s receiving the bonus and cause of the counterpart’s Zero Bonus were orthogonally manipulated. Additionally, Presentation Mode was manipulated, such that information concerning the reason for the counterpart not receiving a bonus was either Overt or Concealed. In the three Overt conditions, the respondents were informed either (1) that their matched participant won the first lottery but their performance fell below the average (Performance), (2) that their performance was not checked and they did not win the second lottery either (Luck), or (3) that the cause was not known and they could not find it out (Unknown). In all conditions, participants were given the opportunity to give their matched partner any part of their bonus (any amount between 0 and 80¢). In the Concealed condition, the cause for the partner not receiving the bonus was not disclosed, but participants had the option to find this out by clicking on a ‘Reveal’ key, before making their donation decision. If they did not wish to reveal the information, they simply continued to the next screen. Table 1 provides a summary of the different conditions, detailing the possible routes through which the counterpart of the respondent could have ended up without a bonus.

Table 1 Outline of the procedure through which the bonus is allocated

After making their decision, participants rated their concern for the counterpart’s outcome and filled out the PES and the Poverty Attribution questionnaire.

8.3. Results

Here, we focus on the allocators’ decision. Of the 863 allocators who completed the survey, 41% (n = 350) gave part of their bonus to their un-endowed partner. The cause for the allocator’s receiving the bonus did not affect any of the measures of interest (all p’s > .2) and did not interact with any of the other factors (all p’s > .3); therefore, we collapsed the data across the two causes for the allocator’s bonus.

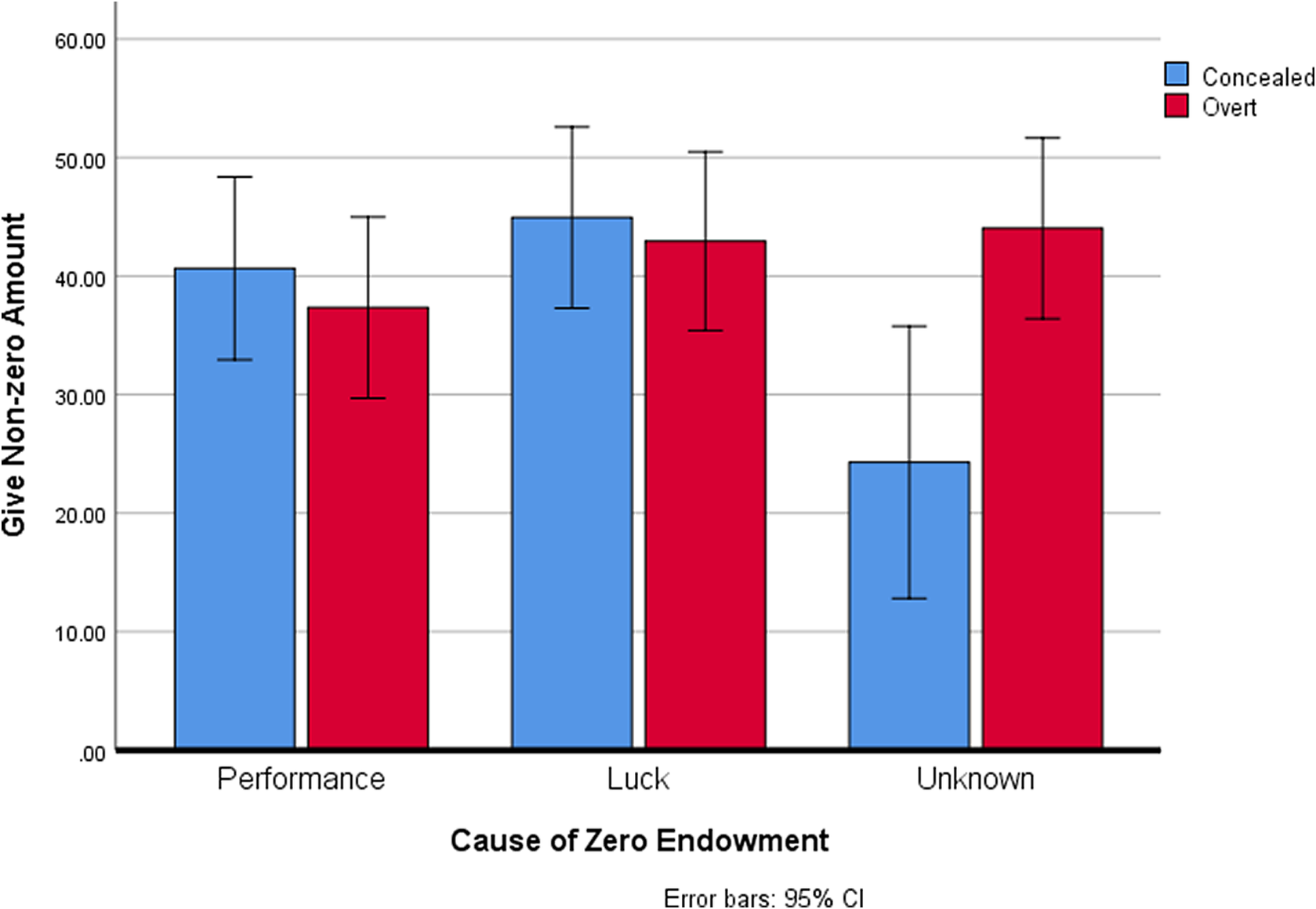

As in the previous experiments, here too we focus on the allocators’ binary decision whether to give at all any of their bonus. Figure 2 shows the percent of givers in each condition, by Presentation Mode (Concealed/Overt) and Cause of the counterpart not receiving the bonus. We note that the cause of the lack of the bonus could be unknown either because it was deliberately ignored (in the Concealed Presentation Mode) or because it was not specified (in case the respondent was randomly assigned to the ‘unknown’ condition in the Overt Presentation Mode). As is apparent, the difference between the two Presentation Modes is most noticeable when the cause is unknown: if the cause was unknown due to deliberate avoidance of the information, as in the Concealed condition, willingness to give was lower than if the information was simply unavailable, as in the Overt Presentation Mode (24.3% vs. 44.0%, respectively, χ 2 (1, N = 229) = 8.039, p = .005). Presentation Mode did not significantly affect giving when the cause of the lack of bonus was poor performance (40.6% vs. 37.3%, respectively, χ 2 (1,N = 313) = .359, p = .549) or bad luck (44.9% vs. 42.9%, respectively, χ 2 (1,N = 321) = .129, p = .719).

Figure 2 Percent of givers by Presentation Mode and Cause of the counterpart not receiving the bonus.

Analysis of the actual amount that would be given by participants who said they would give some of their bonus did not yield any significant effects (F(1, 344) = 1,522, p = .218, ηp2 = .004; F(2, 344) = 1.319, p = .269, ηp2 = .008; and F(2, 344) = .170, p = .843, ηp2 = .001, for Presentation Mode, Cause, and the interaction between Presentation Mode and Cause, respectively).

More importantly, we next explore the decision to pursue additional information in the Concealed condition and its effect on giving behavior. Of the 383 respondents, 313 (81.7%) chose to reveal why their partner did not receive the bonus. Of those who pursued additional information, 42.8% gave their partner some of their bonus; of those who avoided this information, only 24.3% gave their partner any money (χ 2 (1, N = 353) = 8.221, p = .004), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Incidentally, among those who chose to pursue cause information, the actual cause did not appear to have an effect on giving: 40.6% of participants gave money to the partner without the bonus when the partner’s cause was underperformance, compared to 44.9% of participants gave money when the partner’s cause was due to luck (p = .443). Hence, the effect of revealing the cause of the counterpart’s deficiency does not appear to stem from the content of the information. Furthermore, analyses of the choices by participants assigned to the Overt conditions also did not yield significant differences between the percentage of givers in the three conditions (44.0%, 37.3%, and 42.9% for Unknown, Performance, and Luck, respectively, χ 2 (2, N = 480) = 1.683, p = .431).

We next turn to exploring the role of entitlement in pursuing versus avoiding the relevant available information in the Concealed condition. We used the aggregated single entitlement score, as in the previous studies (Cronbach’s alpha = .939). Supporting Hypothesis 2, participants who revealed the information regarding the cause considered themselves as being more entitled than participants who did not reveal the information (M = 3.690, SD = 1.641 vs. M = 2.941, SD = 1.539 vs. for revealers and non-revealers, respectively, t(381) = 3.492, p = .001).

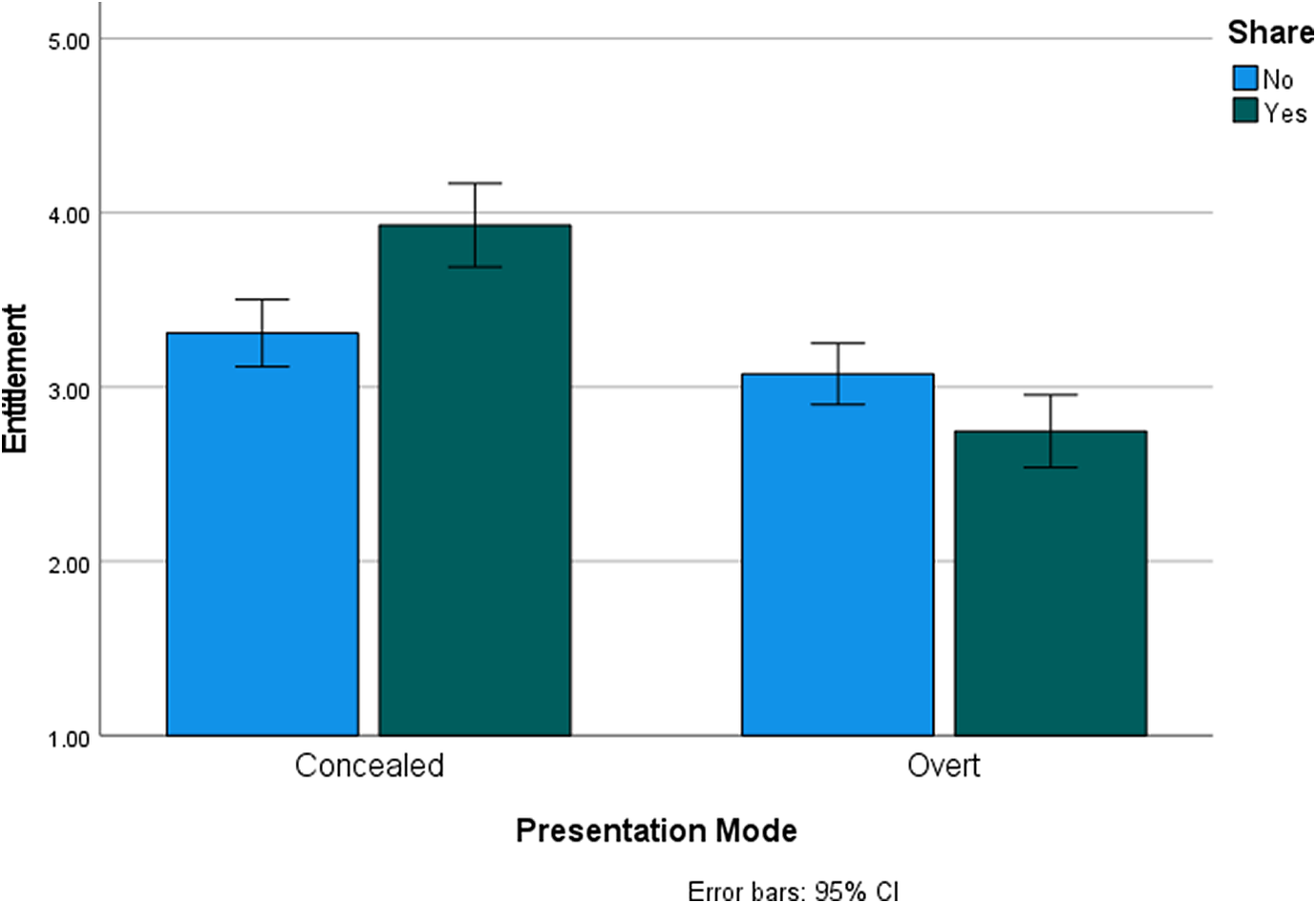

Next, we examine the relationship between entitlement and giving behavior across the two Presentation Modes. Figure 3 presents the mean entitlement score for participants who decided to give and those who did not give, separately for the Concealed and Overt Presentation Modes. ANOVA of entitlement by Presentation Mode (Concealed vs. Overt) and giving decision revealed an unexpected significant effect of Presentation Mode, whereby mean entitlement of participants allocated to the Concealed Presentation Mode was higher than mean entitlement of participants allocated to the Overt Presentation Mode (M = 3.553, SD = 1.647 vs. M = 2.939, SD = 1.398, respectively, F(1,859) = 35.123, p = .001, ηp2 = .039). This effect was not expected. In retrospect, one may speculate that offering the opportunity to decide about obtaining additional information may in itself have increased the sense of entitlement. However, at the stage, this account is completely speculative.

Figure 3 Mean entitlement scores for Concealed and Overt Presentation Modes separately for participants who shared the bonus with their counterpart and participants who did not share.

Giving decision did not significantly predict entitlement in this analysis (M = 3.258, SD = 1.542 vs. M = 3.181, SD = 1.545, for those who shared and those who did not, respectively, F(1,859) = .717, p = .397, ηp2 = .001). Importantly, including an interaction term in the model reveals a significant interaction between giving decision and Presentation Mode (F(1,859) = 20.562, p < .001, ηp2 = .023). Supporting Hypothesis 3, in the Concealed condition, entitlement was associated with an increased likelihood of giving: entitlement scores of participants who gave some of their endowment were higher than the scores of those who did not give (M = 3.929 SD = 1.554 and M = 3.309 and SD = 1.662, respectively, t(381) = 3.658, p < .001). On the flip side, entitlement had the opposite effect when giving did not involve the option to pursue additional information: in the Overt condition, entitlement scores of participants who gave to their counterpart were lower than the scores of those who did not give (M = 2.746, SD = 1.323 and M = 3.075, SD = 1.435, respectively, t(477) = 2.551, p < .011). In sum, entitlement correlated negatively with donation when the respondent could not act to reveal the cause of the recipient’s need. However, when the opportunity to reveal is present, entitlement correlated with revealing, and revealing correlated with donating. Consequently, the overall effect of the opportunity to reveal is to reverse the overall relationship between entitlement and donation.

9. General discussion

We can see that many people are in need. We see it when those who are unhoused are living in tents in urban areas, and we see it when people are panhandling outside the supermarket or at the traffic intersection. Yet how do we respond to these situations? Here, we examine how deliberately avoiding information—‘looking the other way’, so to speak—leads to less giving behavior. We also untangle the role of entitlement in the tendency to avoid information about those in need. All four studies show that people who avoid information are less likely to give than those who pursue additional information about a person in need. Importantly, however, these studies also link the tendency to pursue information to entitlement. Study 1 shows that the tendency to pursue additional information is more common among those who rate themselves as being high in entitlement. Study 2 complements and replicates this relationship between pursuing information and entitlement by experimentally manipulating entitlement before the decisions to give and seek information. Study 3 replicates the findings of Studies 1 and 2 and further shows that among those who seek information, higher entitlement is associated with greater willingness to give. Finally, Study 4 brings the effect full circle, in a decision paradigm that captures real giving behavior. Here, in the condition where decision makers can acquire information prior to making a contribution, people who are high in entitlement are more likely to pursue the information.

These findings offer multiple insights. First, we learn that avoiding information—‘looking the other way’—does enable one to behave more selfishly. When given the opportunity to pursue information to learn the reasons why a person is in need, a substantial minority, in all three studies, preferred to forgo this opportunity (29.5%, 28.1%, and 19.3% in Studies 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and 18.3% in Study 4). Second, we find that people who are high in entitlement are more likely to take the opportunity to pursue more information, when such an opportunity exists.

If people who are high in entitlement are more likely to pursue information about the less fortunate ones, are they also more likely to donate money to help those targets, regardless of whether they pursued the information or not? Conventional wisdom suggests that people who are high in entitlement would be less likely to give to those in need than those who are low in entitlement (i.e., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004). However, we find that this effect of entitlement reverses under some conditions. In particular, in Study 4, in the Concealed condition, where the opportunity to search for more information was presented before the donation question, respondents characterized by high entitlement donated more than others, regardless of whether they pursued the concealed information. By contrast, in the Overt conditions, where an opportunity to search for more information was not presented, high entitlement led to lower willingness to donate. These findings raise the question of whether presenting the donation request in a context that calls for information search is sufficient for moderating the effect of entitlement on selfishness.

Study 3 allows for directly testing this question by comparing one condition in which the opportunity to pursue information was presented before the donation choice and a second condition in which the order was reversed. If presenting the opportunity to search for information is sufficient for reversing the effect of entitlement on giving, we would expect entitlement to play a different role in the two conditions. While across the two conditions, entitlement was marginally positively correlated with donation, the two conditions did not significantly differ from each other and the effect of entitlement did not reach a significance level in any of them.

Studies 1 and 2 do not allow for testing of the above question, as the opportunity to reveal additional information was presented after the donation decision was made. It is perhaps still worth noting that in Study 1, the positive correlation between entitlement and donation was marginally significant, and in Study 2, the correlation did not approach a significance level. In sum, more research is needed in order to establish under what conditions the effect of entitlement on donation depends on the opportunity to search for additional information before making a choice.

Our findings further speak to the motivation behind seeking and avoiding of information. They support the notion that deliberate ignorance in situations like the ones studied here is motivated by the wish to maintain a positive self-image, even as one chooses to behave selfishly. At the same time, the findings suggest that if one’s values and beliefs render the available information less harmful to one’s self-image, the tendency to avoid the information diminishes. Thus, information avoidance as a means to maintain a moral self-image depends on one’s moral and social attitudes. Indeed, in all four studies, we found that self-entitlement was associated with greater willingness to reveal the concealed information. Decision makers who chose to reveal the information were more generous. Thus, while entitlement has a negative effect on generosity when all relevant information is presented, this effect may reverse such that entitlement results in increased generosity when decision makers could pursue additional information. Nevertheless, future research is needed to understand more fully the role of entitlement under different circumstances. Certainly, the fact that entitlement can lead to greater generosity when people have the option to pursue additional information is quite ironic. It would be interesting to study this effect in a real donation context by exploring whether an option to pursue additional information before committing to donate could become a means to garner increased donations from those who are highly entitled. In other words, adding an option to pursue information may well be an intervention, or antidote, to those high in entitlement who would otherwise remain stingy. Relatedly, it would also be interesting to explore the correlates of entitlement to see whether they follow a similar pattern. For example, recent research suggests that people of high economic status from wealthy backgrounds are particularly likely to be high in entitlement (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Stellar, Willer, Forbes, Martin and Bianchi2021). Thus, perhaps adding an option to pursue information in donation solicitations may be one way to get the wealthy to contribute even more to a needy person or cause. Finally, another direction would be to probe for these effects using a different measure of giving behavior. In the present analysis, we focused on donations to a needy person or giving to an underdog who did not receive a bonus in a dictator game. However, would these effects obtain when the measure of giving was different, say the willingness to volunteer at a soup kitchen, the willingness to march for the welfare of the homeless, or even the willingness to sign up for service assignments at work?

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jdm.2025.10027.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by the US Israel Binational Science Foundation (grant number 2022239).