1. Introduction

In this position paper, we argue that second language (L2) pragmatic research needs to explore new avenues for integrating speech acts and interaction, by proposing a radically minimal, finite and interactional typology of speech acts. While we will introduce what we mean by integrating speech acts and interaction in detail below, the following argument helps us to summarise the issue we consider in this study:

When we describe language behaviour, we sometimes use terms such as ‘suggest’, ‘request’ and so on, which roughly indicate illocutionary values, and sometimes terms such as ‘agree’, ‘accept’, ‘contradict’, ‘turn down’, ‘refuse’, which are more indicative of the significance of the utterance relative to a preceding one. What we need to do is to distinguish between these two aspects of a communicative act – the illocutionary and the interactional. (Edmondson et al., Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023, pp. 25–26)

In the centre of the issue outlined here is the need to distinguish illocutionary and interactional values and relying on a speech act typology that sets up and operationalises speech act categories according to this distinction.

The reason why we believe the typology proposed in this position paper is relevant for L2 pragmatic research is the following. While many scholars in L2 pragmatics now certainly view speech acts in an interactional way, to date little attempt has been made to apply a rigorous and finite interactional system of speech acts through a clearly defined procedure. For example, with the surge of discursive pragmatics (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Bardovi-Harlig, Felix-Brasdefer and Omar2006) and research on interactional competence (Young, Reference Young and Young2011), various L2 pragmaticians have adopted an interactional view on speech acts (e.g., Al-Gahtani & Roever, Reference Al-Gahtani and Roever2012, Reference Al-Gahtani and Roever2014, Reference Al-Gahtani and Roever2015; Youn, Reference Youn2018, Reference Youn2020). However, such research essentially focused on how speech acts are co-constructed in longer stretches of interaction. We are certainly in agreement with this body of research, and we believe that the interactional typology of speech acts we are proposing in this position paper neatly complements such research owing to two interrelated reasons. Firstly, our system was designed to capture speech acts at the level of utterance, and by so doing we are able to quantify and contrast our data (see more later). Secondly, such previous research has been interactional in a somewhat different way from what we are proposing in this position paper: while the aforementioned scholars definitely studied speech acts in interaction, they did not rely on an interactionally situated typology per se. Thus, the model we present is not at all in contradiction with such research but rather complements it. The finite and interactional typology we are suggesting can also help the researcher to address various pitfalls in more traditional L2 pragmatics (see Section 2).

In the following, we first provide a critical review of traditional L2 pragmatic research focusing on speech acts. We then present our typology of speech acts. Finally, we propose a procedure through which this typology can be applied in research. We will also refer to various studies we conducted to illustrate how the procedure can be operationalised.

2. Review of literature

Here, we critically discuss three methodological approaches in traditional L2 pragmatic research involving speech acts:

1. Inventing new speech acts ad libitum

2. Conflating illocution and interaction

3. Studying speech acts in isolation

Why are these approaches problematic? As regards the case of freely inventing new speech acts, ad hoc categories such as ‘confessing’ and ‘admonishing’ are unhelpful if our goal is to undertake replicable research based on speech acts with relevance to L2 pragmatics.Footnote 1 If one wants to understand speech act-related puzzlement experienced by L2 learners, it is highly advisable to systematically investigate contrastive pragmatic differences and similarities between the learners’ first language (L1) and L2, without however falling into the trap of the strong contrastive hypothesis.Footnote 2 Yet, it is only possible to contrastively examine pragmatic phenomena that are conventionalised to a comparable degree in both the L1 and L2 linguaculturesFootnote 3 of the learner (cf. House & Kádár, Reference House and Kádár2021a). The idea of only working with comparable and similarly conventionalised units of analysis clearly precludes proliferating speech acts ad libitum. Here, we refer to the invention of new speech acts whenever it suits the researcher's agenda. This has been such a common academic practice that we cannot provide a comprehensive overview of so-called ‘speech acts’ invented for L2 pragmatic purposes owing to space limitation. While we find it difficult to pin down exactly where the idea of freely invented speech act categories originates, we believe that it appeared in the pragmatic literature at least as early as Wierzbicka's (Reference Wierzbicka1985) study, which triggered a wealth of ‘innovative’ speech act categories, such as that of ‘self-sacrifice’ (for a most recent L2 example see Allami & Eslamizadeh, Reference Allami and Eslamizadeh2022). Proliferating speech acts ad libitum precludes the desired replicability of any research because, when it comes to ‘exotic’ speech acts, there is unavoidably a strong variation across linguacultures in terms of their conventionalised existence and use (see House & Kádár, Reference House and Kádár2021a). This variation is particularly problematic in the global classroom where students come from many different linguacultural backgrounds, which means that the researcher is often unable to conveniently refer to culturally homogenous learner groups.

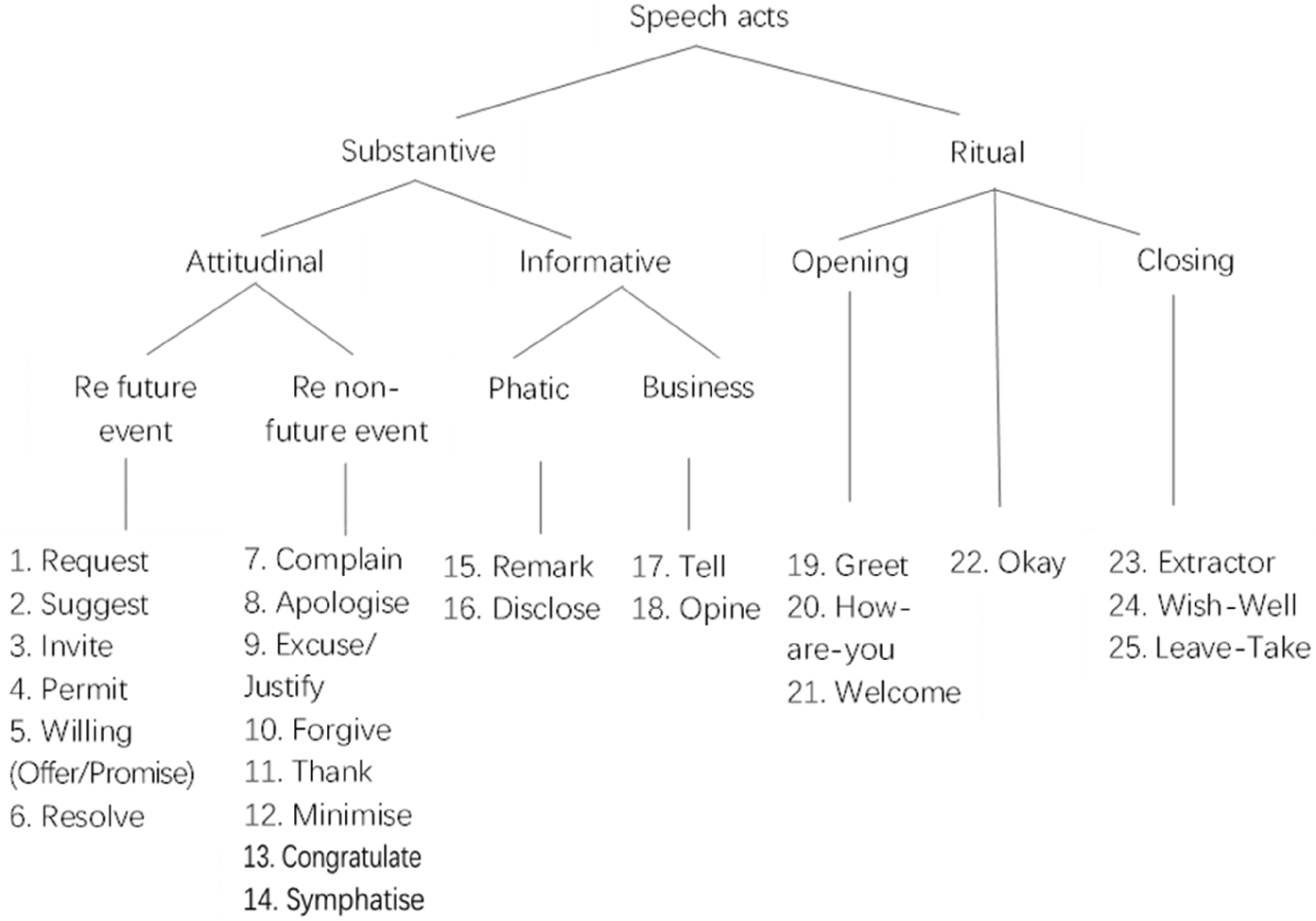

Regarding the second case of conflating illocution with interaction – for example, defining interactional categories such as ‘refusing’ and ‘agreeing’ as speech acts – this methodological approach compromises the very concept of speech act that allows us to differentiate between illocution and interaction. Among others, Edmondson and House (Reference Edmondson and House1981), Edmondson (Reference Edmondson1981) and Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023) argue that a systematic use of speech acts in the study of discourse and interaction can be achieved if we rely on a finite number of speech act categories and various interactional moves through which these speech acts are conventionally interconnected in interaction.Footnote 4 For example, the speech act Invite may be ‘refused’ in interaction through the realisation of many different speech acts, such as Opine, Request (not-to-do-x), Disclose, and so on (see Figure 1 below). Technically speaking, all such speech acts function as responding to an invitation – that is, all of them are ‘refusals’ from an interactional point of view. Exactly because of this, they do not represent the speech act of refusal, but rather they are speech acts through which the interactional phenomenon of refusing can be realised. It seems to us that many L2 pragmaticians have conflated the illocutionary and interactional values of a communicative act. For example, many scholars have taken for granted that ‘refusal’ is an illocutionary category (see e.g. Beebe et al., Reference Beebe, Takahashi, Uliss-Weltz, Scarcella, Andersen and Krashen1990; Cohen, Reference Cohen2005; Eslami, Reference Eslami, Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan2010; Félix-Brasdefer, Reference Félix-Brasdefer, Bardovi-Harlig, Felix-Brasdefer and Saleh Omar2006, Reference Félix-Brasdefer2008; and many others), some others have claimed the same about ‘agreeing’ (see e.g. Holtgraves, Reference Holtgraves2007; LoCastro, Reference LoCastro2000; Maynard, Reference Maynard and Arena1990), and still some others have argued similarly about ‘compliment response’ (see e.g. Culpeper & Pat, Reference Culpeper and Pat2021; Golato, Reference Golato2003; Ishihara, Reference Ishihara, Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan2010; Sharifian, Reference Sharifian2008; Yu, Reference Yu2004; Zhang, Reference Zhang2021). To illustrate why such a conflation is in our view problematic, let us refer here to the case of ‘compliment response’. Responding to a compliment is an interactional move and this move can be realised by different speech acts. If one does not categorise such responses as different speech acts, one unavoidably fails to capture linguaculturally embedded conventions of speech act realisation in this particular interactional slot because one lumps together such conventions under the umbrella of one ‘grand’ speech act. Note that the line of argument we are making here, which we will also revisit in Section 3, accords with the position of various discourse analysts such as Eelen (Reference Eelen2001) who criticised traditional pragmatic research on speech acts.

Figure 1. Our radically minimal, finite and interactional typology of speech acts (cited from Edmondson et al., Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023, p. 103)

Regarding the third practice of studying speech acts in isolation, it has also been criticised by various interactional L2 pragmaticians we align ourselves with (see Section 1). The narrow focus on individual speech acts ignores the fact that speech acts are inseparable parts of interaction and should only be analysed from the departure point of interaction. Regarding this third pitfall of studying speech acts in isolation, we believe that it has its roots in the 1980s. L2 pragmatic research involving speech acts can be said to have started in that period (see an early overview in Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984), with the renowned Cross-Cultural Speech Act Realisation Project (CCSARP; Blum-Kulka et al., Reference Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper1989). Although the CCSARP Project was conducted more than three decades ago, its methodology continues to be used worldwide up to the present day (see e.g. Cohen, Reference Cohen2005; Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2017; Kasper & Blum-Kulka, Reference Kasper and Blum-Kulka1993; Koike, Reference Koike1989; Olshtain & Cohen, Reference Olshtain and Cohen1990; Rose & Ono, Reference Rose and Ono1995; Vacas Matos & Cohen, Reference Vacas Matos and Cohen2022; Woodfield, Reference Woodfield, Felix-Brasdefer and Koike2012). A key strength of CCSARP-based studies is that they operate with strictly defined pragmatic categories, enabling researchers to annotate and contrastively examine L1 and L2 speech act performance in a rigorous and replicable way. However, just like the CCSARP Project itself – which was launched by the first author of this paper with her colleagues – this body of research has focused on preset speech act categories, such as Request and Apology. This predetermination of the object of analysis unavoidably led to a top–down take on speech acts in a body of L2 pragmatic research based on the CCSARP methodology. While this approach allows the scholar to examine speech act performance, it cannot capture more complex speech act-related problems, which only emerge when one views speech acts embedded in interaction in their whole complexity. For example, various scholars have studied the speech act Greet in isolation (see e.g. Shleykina, Reference Shleykina2016) – such a focus distracts the researcher away from studying the inherently important interactional embeddedness of the speech act Greet. In our view, it is far more realistic and thus fruitful in terms of L2 pragmatics to examine linguaculturally embedded L1 and L2 conventions of speech act realisation in the larger Opening phase of an interaction where Greet may (or may not) occur. Accordingly, we believe that it is essential to consider whether the Opening phase of an interaction tends to be realised by Greet or another speech act in the learner's L2 linguaculture, and how this compares with the pragmatic conventions of Opening in the L1 linguaculture. Such differences (and similarities in other cases) can in turn help us also to better understand puzzlements expressed by foreign language learners.

These critical observations of certain traditional speech act-related L2 pragmatic studies have led us to make our present claim for the need of further interconnecting speech acts and interaction in the pragmatic study of L2 learning.

3. The benefits of a finite and interactional speech act typology for L2 pragmatics

In the following, we first present our finite and interactional speech act typology that we recently published in Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023). In this new book, we revised and updated the original model of Edmondson and House (Reference Edmondson and House1981), by relating it to present-day discourse analysis and interactional ritual theory. We then discuss why this typology – which we label here as ‘radically minimal’ – may be beneficial for interactional L2 pragmatic research.

The following Figure 1 displays our typology.

This typology includes 25 basic speech acts derived on the basis of an interactional analysis of multilingual corpora. Originally, Edmondson and House set up this typology in 1981 with the aid of relatively small English and German corpora. In Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023), we tested the replicability of this typology by using large corpora drawn from a variety of typologically distant languages, such as English, German, Chinese, Japanese and Hungarian.

In using the proposed typology, we follow certain conventions. The perhaps most important ones are the following. First, we indicate the 25 speech act types in the typology with capital letters (e.g. ‘Complain’ versus ‘complaint’). Second, we distinguish our finite set of speech acts from non-finite interactional acts – we indicate the latter with the ‘-ing’ form. For example, bargaining (House et al., Reference House, Kádár, Liu and Bi2021a) is a typical interactional act that is realised through a cluster of speech acts, such as Request, Suggest, Opine and so on.

The typology is divided into two main types: ‘Substantive’ and ‘Ritual’. The ‘Substantive’ group includes speech act types that are generally considered to be ‘meaningful’, while ‘Ritual’ speech acts tend to occur in specific parts of an interaction and are, therefore, highly predictable, and have a social meaning, such that the literal meaning of the utterance – if any – is almost incidental to the significance of the utterance for the interactants. As Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023), and House and Kádár (Reference House and Kádár2021b) argued, this typology represents the default function of speech acts, and any speech act can ‘migrate’ into other slots in the typology. For example, in certain contexts a Substantive Attitudinal speech act can take on a conventionalised Ritual function. When one encounters a speech act-related problem in L2 pragmatics, the above interactional typology prompts one to consider which speech acts are frequented in a given interactional phase in the learner's L1 and L2.

To give an example of the above notion of ‘migration’ of speech acts and the application of our typology, let us refer to our recent study (House et al., Reference House, Kádár, Liu and Liu2022) dedicated to the L2 pragmatic investigation of the interactional act of greeting. This research started as the second author of this paper – who is a foreign learner of Chinese – was puzzled by the absence of the speech act Greet in certain contexts in Chinese. In other words, it was the interactional absence of Greet rather than certain greeting forms alien to him that puzzled him. In following up on this puzzlement, we did not immediately zero in on the speech act Greet, but rather contrastively examined the interactional phase of Opening Talk to investigate which speech acts tend to be conventionally realised in this phase in the L1 and L2 linguacultures. By so doing, we ventured beyond the assumption that Greet is an inherent part of Opening Talk, and also designed our methodological approach accordingly. The results of this study differed from what other researchers argued before, namely that the Chinese ‘do not greet one another’ (see e.g. Huang, Reference Huang2008; Ye, Reference Ye2007). For example, we learnt that in Chinese Opening Talk the Phatic speech act Remark is frequented while Greet is non-ubiquitous, which in turn helped us to explain L2 learner puzzlements.

Let us now discuss why we believe that this typology is beneficial for L2 pragmatic studies, which like ourselves take an interactional view on speech acts. Here, we depart from the admittedly radical statement that speech act-related L2 pragmatic research needs to be based on a finite – and thus replicable – interactional typology of speech acts. Let us start this discussion with the notion of finiteness. Finiteness is neither new nor uncontroversial (see also Jucker, Reference Jucker2008). Ever since Austin and Searle, the idea that speech act categories need to be finite has been present in the field of pragmatics (see e.g. Croft, Reference Croft and Tsohatzidis1994; Habermas, Reference Habermas1979; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Bardovi-Harlig, Felix-Brasdefer and Omar2006; Kissine, Reference Kissine2013; Vanderveken, Reference Vanderveken1990), with Levinson (Reference Levinson and Huang2017) revisiting this issue recently. As various scholars have noted, the reason why finiteness is potentially controversial is that with the passing of time one may ‘identify’ new speech acts. To provide a few examples, Nelson (Reference Nelson1991) distinguished ‘new speech acts’ emerging in world Englishes, and Kogan (Reference Kogan2008) identified speech acts coming into existence with technological advancement. While such approaches surely have their own rationale, we ourselves adopt a different position: as we argued in Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023), we take an explicitly radical stance on speech acts, by proposing a finite set of replicable and interactionally defined speech act categories and claiming that they should not be complemented with other new speech act categories. The question may rightly emerge: is a particular set of interactionally embedded speech acts ‘sufficient’ and can others not rightly identify new speech acts? Also, can we ‘reserve the right’ of insisting that only our speech act categories legitimately exist? These would be fair questions to ask, and our response would be that the speech acts we propose are ‘minimal’ in the Chomskyan sense – that is, they are designed to represent the basic pragmatic unit of speech act which is meant to be smaller than units of interaction (see also Streeck's, Reference Streeck1980 early criticism of Searle). This is also why such speech act categories are not ‘ours’, in that a radical finite typology of speech acts needs to include only those speech acts that are such simple and basic constituents of language use that they can easily be replicated in the study of interaction across languages and datatypes (see more below).

Along with finiteness, let us also explain what we mean by interactionality. When one uses a typology of speech acts like ours, one needs to break down interaction into moves and examine how moves relate to one another, as ‘initiating’, ‘satisfying’, ‘countering’ and ‘contra-ing’Footnote 5 moves (for more detail see Edmondson et al., Reference Edmondson, House and Kádár2023). Initiating refers to speech acts through which an exchange is started, satisfying includes speech acts through which an initiating speech act is satisfied, countering points to speech acts through which an initiation is countered but not entirely rejected, whereas if it is turned down it would be contra-ed in our terminology. This view is compatible with Conversation Analysis (CA) (see Pomerantz, Reference Pomerantz, Atkinson and Heritage1984), in that we interpret all basic speech acts as interactionally interrelated phenomena through which more complex interactional phenomena can come into existence. The reasons why we do not use the CA notions of ‘adjacency pair’ and ‘preference organisation’ is the following: as Paul Drew and his colleagues explained (Drew, Reference Drew2013; Drew & Walker, Reference Drew, Walker, Coulthard and Johnson2010), convincingly in our view,Footnote 6 conversation analysts use speech act theory to interpret particular conversationally relevant turns-at-talk in their data. They also study how speech acts are co-constructed in interaction, hence taking a relatively ‘broad’ view on speech acts. We believe that this view is valid and important. Yet, in our approach we use speech act categories to interpret every turn in any data as a speech act or cluster of speech acts, and also unlike conversation analysts we do not operate with the notion of extended speech act. Because of this, we also interpret the turn-by-turn relationship between speech acts and attempt to capture and quantify pragmatic conventions of this relationship by using the above-outlined non-CA terminology. Let us illustrate how our terminology can be operationalised in L2 pragmatic research with a simple example. A structurally ‘initiating’ speech act Invite (‘Would you like to come to my party tonight?’) may, in our terms, either be ‘satisfied’ (‘Would love to, thanks’), or ‘contra-ed’ (‘Can't, I'm afraid’). We may use these terms in an L2 pragmatic study of English by arguing that they show that an Invite in English can be ‘accepted’ in popular terms with the speech act Thanks – instead of the ‘responsive speech act’ of ‘invitation-thanking’ – and it can also be conventionally ‘turned down’ with the speech act Resolve instead of ‘refusal’, which is an umbrella term.

As this description illustrates, finiteness and replicability – as we interpret these notions – provide a different insight into speech acts from a body of research dedicated to ‘responding speech acts’. We believe that our approach has both research and pedagogic advantages. Take the case of ‘compliment response’ mentioned in Section 2 as an example. We do not deny the easy applicability of this category in teaching. However, there may be students who would like to know exactly what the broad category of ‘response’ actually includes in their L1 and L2. For example, U.S. American students of Chinese may wonder why native speakers of Chinese do not utter the speech act Thanks at all when they receive a compliment, which would be one possible convention in American English.Footnote 7 Instead, speakers of Chinese tend to use the speech act Minimise, for instance saying Buhui (‘How could I’), or other speech acts such as self-denigrating Opines (e.g. Wo de yifu hao chou ‘My clothes are ugly’) when they respond to compliments. Our typology therefore allows one to teach compliment responses to L2 learners in a differentiated way, by drawing learners’ attention to the linguaculturally diverse realisation patterns of the phenomenon on hand. We believe that the approach we are proposing here not only has a definite teaching advantage, but also it does not actually run counter to the findings of previous responsive speech act-oriented research and teaching practices. That is, instead of denying the validity of such research, we simply reinterpret speech act-responding phenomena at a different level of analysis – that is, as interactional moves rather than speech acts.

Another advantage of our interactional typology of speech acts is that it enables a systematic comparison of speech act-related phenomena in both the learner's L1 and L2 (see a relevant overview of contrastive methodologies in L2 pragmatics in Taguchi & Li, Reference Taguchi and Li2020). While using a contrastive pragmatic methodology can have its own pitfalls (see an overview in House & Kádár, Reference House and Kádár2021a), we would like to emphasise the important conceptual and methodological advantage of incorporating a contrastive comparative approach into speech act analysis. Let us provide an example. In the study of speech act realisation patterns in the Closing phase of an interaction, we cannot assume that it is inherently the speech act Leave-Take that is realised in both the learner's L1 and L2, even though it may appear to be ritually ‘normal’ from a ‘Western’ point of view to expect the speech act Leave-Take to be realised in this interactional slot. However, as we argued elsewhere (see House & Kádár, Reference House and Kádárin press b), in many interpersonal scenarios speakers of languages such as Chinese clearly disprefer using the speech act Leave-Take in Closing. Rather, speakers of Chinese tend to close an interaction with the speech act Remark in various interpersonal relationships. Failing to consider comparability can therefore lead to a priori assumptions that do not pass the test of language use in real life.

Having discussed the benefits of the typology of speech acts proposed here, let us now introduce a replicable procedure through which this typology can be applied in empirical research.

4. Research procedure

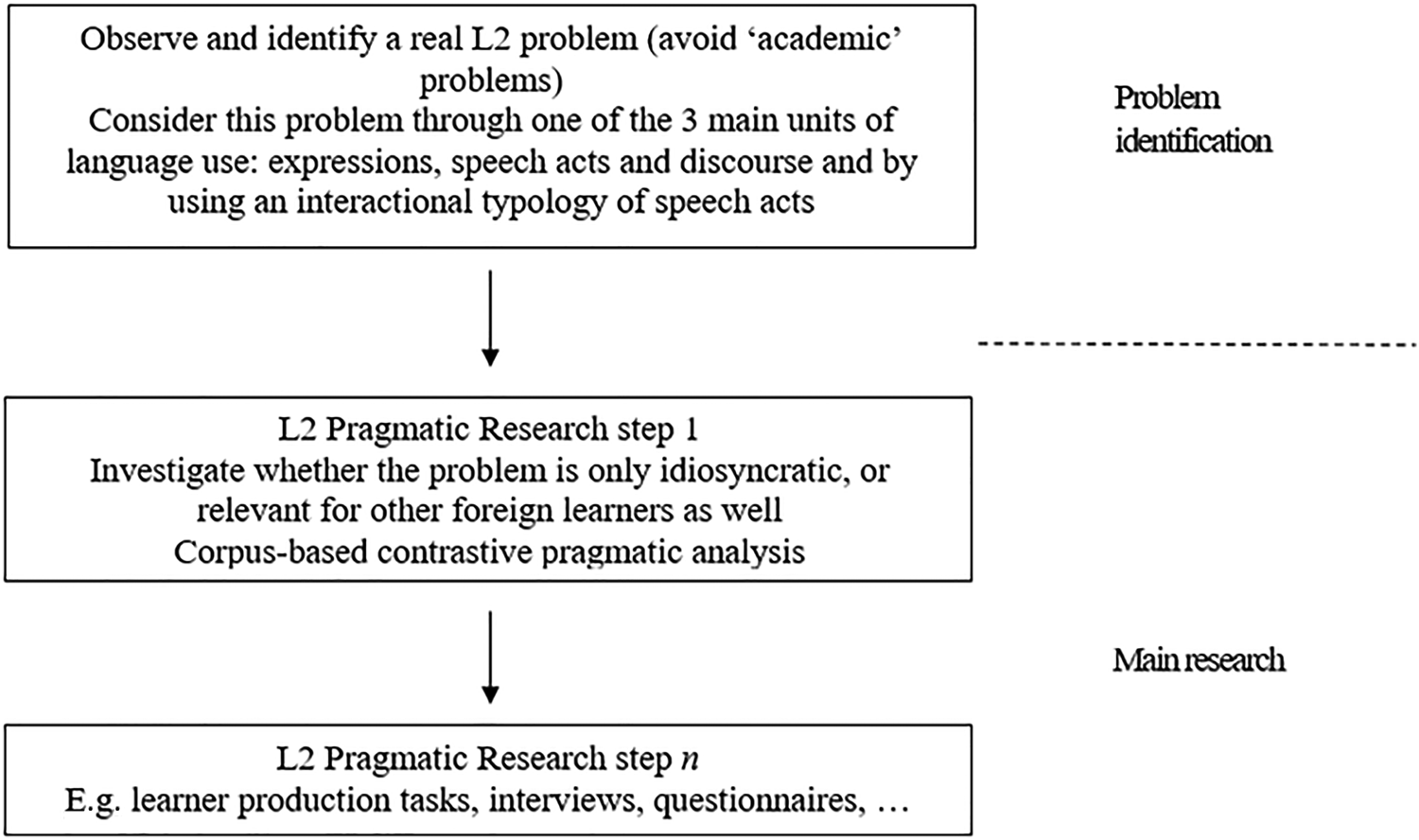

Consider Figure 2, which illustrates our research procedure below. As Figure 2 shows, our procedure is tripartite: it is divided into the two phases of problem identification and main research, with the phase of main research having at least two components.

Figure 2. Our research procedure

Regarding the phase of problem identification illustrated by the upper part of Figure 2, we believe that L2 pragmatic research needs to start with the observation of a real problem. We find it problematic to study predominantly academic questions, such as which forms of Greet should be taught to a certain learner group, without having proof of an actual L2 pragmatic problem relating to the use of the speech act Greet. This is why we propose focusing on instances of learner puzzlement, as in the case of our aforementioned research on Greet (see House et al., Reference House, Kádár, Liu and Liu2022 above). There, we found that Greet is non-ubiquitous in Chinese, while it is ubiquitous in English, and this pragmatic difference often puzzles Chinese learners of English. To explain this puzzlement, let us briefly refer here to pragmatic conventions of greeting in Chinese: in informal settings, speakers of Chinese often use speech acts such as How-are-you (e.g. Ni chifan-le ma ‘Have you eaten?’) and Remark (e.g. Qu-nar ‘Where are you going?’), without expecting to receive an answer to such rhetorical questions, instead of the speech act Greet. The departure point of learner puzzlement also allows us to interconnect our speech act research with a large body of L2 pragmatic studies starting with puzzlement (see e.g. Jaworski, Reference Jaworski1994; Schauer, Reference Schauer2022).

As Figure 2 shows, we use our typology of speech acts in the stage of identifying problems of language use faced by L2 learners. For example, in a recent study (see House & Kádár, Reference House and Kádárin press a) we examined instances of puzzlement experienced by foreign learners of Chinese when the act of congratulating is due in certain ritual occasions in their L2 linguaculture. In interpreting such cases of puzzlement, we analysed what was expected from the learners in their target linguaculture and how such conventional expectations differed from what these L2 learners actually said. This problem is more important than meets the eye because L2 learners may not only need to be able to realise the interactional act of congratulating in those few occasions when they may participate in a liminal ritual event (Turner, Reference Turner1969) in their L2 linguaculture, but also at much more mundane occasions – for example, workplace meetings when a colleague casually tells them about a family event, such as the 80th birthday of a family member. Our investigation led to the finding that many foreign learners of Chinese preferred to realise the speech act Wish-Well in the ritual act of congratulating, instead of the speech act Congratulate, and this pragmatic transfer was one of the reasons which triggered the learners’ puzzlement when they faced real instances of congratulating in the Chinese linguaculture.

As both the cases of greeting and congratulating above show, the interactional and finite nature of our typology is fundamental when it comes to problem identification. In both cases, we did not depart from focusing on a single speech act but rather we investigated phases of interaction (or Types of Talk in our terminology) in which certain speech acts conventionally occur, or do not occur.

As Figure 2 shows, the second major phase in our procedure includes the main (L2 pragmatic) research. This phase consists of at least two steps, including separating idiosyncratic behaviour from conventionalised pragmatic behaviour, and a follow-up L2 pragmatic investigation. The latter may include various steps – for example, one may here include discourse completion tests (DCTs), questionnaires, interviews and other production tasks in one's analysis.

Let us start with the first step here: once we identify a real L2 learning problem relating to pragmatics and considered it through our interactional typology of speech acts, the next step is to investigate whether this problem is only idiosyncratic and thus trivial or is relevant for other L2 learners as well. Here, we are not arguing against including individual learner considerations in one's research.Footnote 8 Rather, we wish to point out that in any rigorous and replicable research in L2 pragmatics involving speech act realisation, it is essential to identify interactional conventions of language use, including those that trigger learner puzzlement. As soon as we know that a problem is worth investigating, corpus-based research can be particularly useful to get at the heart of the reasons for learner puzzlement.Footnote 9 That is, through a corpus-based, contrastive and language-anchored study, the researcher may be able to unearth deep-rooted reasons underlying L2 puzzlement and consider such reasons through the lens of the proposed typology of speech acts. Let us provide an example here. In House et al. (Reference House, Kádár, Liu, Liu, Shi, Xia and Jiao2021b), we investigated the following L2 pragmatic problem: Chinese learners of English often find ‘altered’ uses of expressions associated with certain speech acts in English, such as complaining uses of Thank you very much, difficult to interpret. In this case, Thank you very much may not indicate the speech act Thanks, but rather the very different speech act Complain, as the speaker comments on something that annoys her or him. In other words, a ‘migration’ of speech acts can be observed here (see our discussion below Figure 1). To understand what causes learner puzzlement in this situation, we conducted a contrastive pragmatic investigation of two groups of comparable ‘Thanks expressions’ in the British National Corpus and the Balanced Chinese Corpus. Expressions such as Thank you very much were found to operate in a pragmatically much more diverse way than their Chinese counterparts such as Ganxie, which in turn provided a gateway to understand and explain the problem mentioned by the L2 learners involved in our study.

In this step, it is important to make sure that the analyst interprets the outcome of corpus analysis in a language-anchored way – that is, without overinterpreting the results by attributing them to cultural values and other grandiose nonlinguistic notions (see also Romero-Trillo, Reference Romero-Trillo2018 on interpreting L2-related corpus research). By doing so, we can avoid relying on notions such as ‘cultural values’, ‘cultural ethos’, ‘individualism’, ‘collectivity’, face-sensitivity’, and the infamous ‘East–West divide’.Footnote 10 Why do we argue against a non-language-anchored cultural view? Unfortunately, various scholars such as Byon (Reference Byon2002), Hosni (Reference Hosni2020), Maíz-Arévalo (Reference Maíz-Arévalo2017) and Meier (Reference Meier, Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan2010) discussed speech act performance in L2 pragmatics through cultural notions, arguing that assumed cultural characteristics determine language learners’ behaviour. By following an essentialist approach, the researcher unavoidably makes a priori assumptions, implying that any pragmatic difference they identify between the L1 and L2 of the learner is unavoidably influenced by innate cultural ascriptions. By degrading learners to cultural robots, the researcher precludes unearthing fine-tuned pragmatic conventions that – unlike ‘collectivism’ or its lack, and so on – may trigger real L2 learning difficulties (see also Ishihara & Cohen's, Reference Ishihara, Cohen, Ishihara and Cohen2021 discussion). For instance, it may be tempting to exoticise results of a Chinese corpus analysis when it comes to the above-mentioned instances of the speech acts Greet and Thanks, falling into the trap of presenting L2 learners as people with essentially predictable behaviour. While phenomena such as ‘face-sensitivity’, ‘collectivity’, ‘Confucian ideology’, and so on may certainly be interesting to consider, we believe that they should be avoided because they preclude looking at speech act realisation in interaction in a bottom–up manner. Also, there is no way to reliably interpret corpus-based results by using such cultural notions if, for nothing else, because no corpus is perfect nor representative (see Sharoff et al., Reference Sharoff, Rapp, Zweigenbaum and Fung2013).

We believe that corpus-based research might be ideally complemented by L2 production tasks assigned to learners, as also shown in Figure 2. Methodologically, such tasks should again rely on an interactional typology of speech acts, and also they might ideally be multimethod in nature. Let us here refer to House and Kádár (Reference House and Kádárin press b). In this study, we examined the L2 pragmatic features of a particular type of Closing phase in which one interactant intends to leave the scene while the other relentlessly goes on talking – an interactional act we define as ‘extracting’ oneself from an interaction (hence the -ing form). Anglophone conventions of extracting were found to be challenging for Chinese learners of English because extracting oneself from an interaction often triggers significant face-threat to one's interlocutor.Footnote 11 We first administered DCTs to these learners and compared them with DCTs administered to ‘native’ speakers of English,Footnote 12 both featuring the interactional move of extracting oneself from an interaction rather than a particular speech act (like Extractor itself). Following the DCTs, we conducted interviews with the same L2 learners and native speakers of English, in order to tease out their metapragmatic interpretations of the phenomenon studied.

As this overview of our procedure has shown, our concern is not so much how to use and fine-tune L2 pragmatic research methodologies like DCTs, even though such fine-tuning is an important issue, but rather how to position such methodologies in one's research by using our typology of speech acts.

5. Conclusion

In this position paper, we have made a claim for L2 pragmatic research to further integrate speech acts into interaction studies and discourse analysis, by proposing a radically minimal typology of speech acts through which we interpret speech acts interactionally. Speech act theory has been well established in L2 pragmatics and various scholars have moved speech act analysis into the realm of interaction. However, we believe that further work is needed, all the more because traditional speech act research in L2 pragmatics – which continues to have an influence on the field – has unfortunately failed to follow the robust focus on interaction that is predominant in mainstream pragmatics. Today many pragmaticians may find it problematic to study speech acts in isolation, invent speech acts ad libitum, or conflate illocutionary and interactional values. This is why various L2 pragmaticians have proposed interactional approaches to their data, and we believe that our typology and research procedure provide an important contribution to this existing body of inquiries.

Complementing interactional L2 pragmatic research on speech acts with our typology and the related research procedure would, in our view, bring advantages for the field. For example, having an interactional approach to speech acts can help us to use DCTs in a more interactional way, hence resolving many criticisms launched at this methodology over the past decades. An interactional perspective is also essential for detecting genuine problems faced by L2 learners in terms of speech acts. Instead of assuming that a particular speech act is problematic for L2 learners in an a priori fashion, it is much more productive to observe a particular interactional situation and investigate in a bottom–up way exactly which speech acts turn out to be problematic for a certain group of learners and exactly why they are problematic.

We hope that future research in the field of L2 pragmatics will witness an even closer alignment between speech acts and interaction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the funding of the National Excellence Programme of the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of Hungary (grant number: TKP2021-NKTA-02). We would also like to acknowledge the funding of the National Research Development and Innovation Office, Hungary (grant number: 132969). On a personal level, we would like to say thank you to the editor, Dr Graeme Porte, and the 4 anonymous reviewers for their expert comments, which helped us enormously to improve the quality of our work.

Conflict of interest statement

We hereby confirm that we have no conflict of interest.

Juliane House received her Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics from the University of Toronto and Honorary Doctorates from the Universities of Jyväskylä and Jaume I, Castellon. She is Professor Emerita at University of Hamburg, Professor at the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics, Distinguished University Professor at Hellenic American University, Nashua, NH, USA and Athens, Greece, and Visiting Professor at Dalian University of Foreign Languages and Beijing University of Science and Technology, China. She is co-editor of the Brill journal Contrastive Pragmatics: A Cross-Disciplinary Journal, and Past President of the International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies. Her research interests include applied linguistics, translation, foreign language learning and teaching, contrastive and L2 pragmatics, discourse analysis, linguistic politeness research and English as a global language. She has published widely in all these areas.

Dániel Z. Kádár (MAE, D.Litt, FHEA, Ph.D.) is Ordinary Member of Academia Europaea, Chair Professor, Ph.D. Supervisor and Director of the Centre for Pragmatics Research at Dalian University of Foreign Languages, China, and Research Professor at the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics. He is author of many books, produced by publishing houses of international standing such as Cambridge University Press. He is co-editor of Contrastive Pragmatics: A Cross-Disciplinary Journal. His research interests include applied linguistics, contrastive and L2 pragmatics, foreign language learning and teaching, Chinese linguistics, linguistic politeness research and discourse analysis.