W. B. Yeats did not dislike impressionism; he loathed it. This is a fact often overlooked by his critics, who (like Yeats himself) usually talk about his visual interests in terms of the tastes he inherited from his Pre-Raphaelite father, or of the later poetry’s allusions to ‘Michael Angelo’ and Paul Veronese.1 As Yeats would remind his readers, he had ‘learned to think in the midst of the last phase of Pre-Raphaelitism’, and as a young man ‘was in all things Pre-Raphaelite’.2 Accordingly, the dominant assumption has been that the younger Yeats was indifferent to ‘the major figures of twentieth-century modernism’, and to recent developments on the Continent more generally, preferring to confine his attention to the ‘great men’ of the Renaissance, to their Victorian interpreters in Cheyne Walk, and to those artworks which ‘express[ed] personal emotion through ideal form, a Symbolism handled by the generations’.3

That is one part of the truth. Through his father, Yeats had been introduced to the symbolic paintings of William Blake and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and then, through Rossetti – ‘the most powerful of all’ his early artistic influences – to the richly coloured oil works of Titian (A, p. 235). Particularly important to Yeats was Rossetti’s so-called Venetian turn, where the austere bounding lines of his early paintings gave way to the dream-shadowed folds of Jane Morris’s hoopless gowns, and to Fanny Cornforth’s tumbling bronze hair, all darkened by Rossetti’s red undercoats of oil, thickly applied, after the manner of Titian. ‘I thought that only beautiful things should be painted, and that only ancient things and the stuff of dreams were beautiful’, he remembered (A, p. 92); and, indeed, many of his early poems are addressed to Lilith-like women with ‘dream-dimmed eyes’ and ‘cloud-pale eyelids’, whose ‘lips are apart’ and whose ‘breasts are heaving’.4 By his teens, however, Pre-Raphaelitism had given way to something new and different, as Yeats discovered in 1884 on entering the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, where ‘young men fresh from the Paris art-schools’ informed him, ‘We must paint what is in front of us.’ ‘If I spoke of Blake or Rossetti they would point out his bad drawing and tell me to admire Carolus Duran and Bastien-Lepage’, just as George Moore and Arthur Symons would later encourage him to admire Manet and Degas, whose devotion to ‘externalities’ left him ‘in raging hatred’ (A, pp. 114–18). But rage of this kind is significant, indicating strong feelings about visual forms in which Yeats is supposed to have had little interest. Indeed, his early theories of symbolism seem repeatedly to have been threatened or unsettled by the paintings of Manet. Time and again, Yeats countered them with the art of Titian, which came to serve as a paradigm for his own evolving poetics. The present chapter considers the opposition in Yeats’s thought between recent French painting and the art of the Renaissance, as well as the cognate binaries – of hard outline against glimmering colour, unity against disunity – this came to encompass, before exploring their formative relation to the symbolist style he was developing during the last decade of the century.

In beginning to understand Yeats’s idiosyncratic attitudes towards contemporary French art, and his unorthodox view of impressionism in particular, it is useful to retrace his steps. The dominant theme in his recollections of his initial encounters with French painting (or, more accurately, its undergraduate exponents) is disillusionment. As Yeats remembered in The Trembling of the Veil (1922), his peers at art school ‘were very ignorant men’: ‘they read nothing, for nothing mattered but “knowing how to paint”’. He ‘hated these young men’ and ‘their contempt for the past’, for ‘unlike others of my generation’, Yeats remarked, ‘I am very religious’. Having been ‘deprived by Huxley and Tyndall, whom I detested, of the simple-minded religion of my childhood’, he had founded for his own use ‘a new religion, almost an infallible church out of poetic tradition: a fardel of stories, and of personages [passed] on from generation to generation by poets and painters’. ‘I had even created a dogma’, Yeats tells us:

‘Because those imaginary people are created out of the deepest instinct of man, to be his measure and his norm, whatever I can imagine those mouths speaking may be the nearest I can go to truth’. When I listened they seemed always to speak of one thing only: they, their loves, every incident of their lives, were steeped in the supernatural.

To Yeats’s pietas, the ‘school [which] insists on the vision of the eyes and that alone’ (‘D’, p. 303), as he characterised the impressionists in his diary in 1908, seemed idolatrous; and the names Bastien-Lepage and Carolus Duran – artists not officially associated with the original impressionist group, but sufficiently ‘new’ and ‘French’ to be joined with them in Yeats’s mind – would, along with those of John Tyndall and Thomas Huxley, be yoked together in the Autobiographies to form a kind of compound expletive. He loathed Lepage’s Les foins (1877), which depicted a ‘clownish peasant’ insulated by some ‘protecting stupidity’ from the grave vision of the portrait Yeats loved most of all, Titian’s Ariosto (1510) (A, p. 121). As he recalled in ‘The Tragic Theatre’ (1910), ‘I hated at nineteen years [the] new French painting’ (EE, p. 176), later remembering ‘I found nothing I cared for after Titian’ until ‘Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites’ (A, p. 115). At the Royal Hibernian Academy as a student, Yeats saw Manet’s portrait of beer-cradling prostitutes, Les bockeuses (1878) and ‘was miserable for days’: ‘I found no desirable place, no man I could have wished to be, no woman I could have loved, no Golden age, no lure for secret hope’; ‘All that I had thought beautiful, lofty, serene was attacked’ (‘D’, p. 301).5 He was rocked, too, by his father’s abandonment of his early Pre-Raphaelite manner and his enthusiastic embrace of the new style: ‘a Dublin street scene by my father made me almost as miserable, [and] I remember arguing that modern streets could not be fitting subjects for art, for even Whistler had to half lose them in the mist to make them pleasant to the eye’ (‘D’, p. 301). Surrounded by admirers, like his mentor W. E. Henley, who not only ‘despised Rossetti’, but ‘praised Impressionist painting that still meant nothing to me’, Yeats retreated to his infallible church of pictorial tradition, where he immersed himself in symbolic patterns of colour and variegated light which ‘escaped analysis’.6

That word, ‘escape’, has a crucial significance for Yeats, and one which shapes his appraisals of impressionist art. Usually, as here, he wished to escape certain facets of his contemporary modernity: its enthusiasm for empirical ‘analysis’ was one; another was ‘abstraction’, by which he meant ‘not the distinction but the isolation’ of individuality, and which he remembered having ‘reached its climax’ in the last years of the century (A, p. 164). But if he hoped that ‘escape might be possible for many’, he would often be disappointed (A, p. 166). When A Doll’s House (1879) played at the Royalty, for example, Yeats ‘hated the play’ – ‘what was it but Carolus-Duran, Bastien-Lepage, Huxley and Tyndall, all over again’? Ibsen became the idol of ‘clever young journalists, who, condemned to their treadmill of abstraction, hated music and style’, and yet ‘neither I nor my generation could escape him because, though we and he had not the same friends, we had the same enemies’ (A, p. 219). The larger battle was with the ‘poetical dialect’ of what, in his introduction to The Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1936), Yeats termed ‘Victorianism’, recalling evenings with the Rhymers’ Club where young poets ‘said to one another over their black coffee – a recently imported fashion – “We must purify poetry of all that is not poetry”.’ This meant ‘writing lyrics technically perfect, their emotion pitched high, and as Pater offered instead of moral earnestness life lived as “a hard gem-like flame” all accepted him for master’.7 On the other hand, even while he felt a fraternal obligation to join in his generation’s rejection of the ‘analytical’ discursiveness of Browning and Tennyson, Yeats sought also to escape the alternative kind of abstraction latent in the ‘Parisian Impressionism’ of his friends (A, p. 238). In a review of Symons’s fourth collection, Amoris Victima (1897), for instance, he welcomed the replacement of a poetry which had absorbed into itself ‘the science and politics [of] its time’ by a style of verse which was more ‘personal and lyrical in its spirit’, as in the volume of ‘exquisite impressions’ under review.8 But Yeats was in fact privately sceptical of the ‘vivid impressions’ that Symons had harvested from ‘music halls and amorous adventure’.9 ‘The arts which interest me’, he wrote elsewhere, remained ‘at a distance from a pushing world’, steeped in ‘images more powerful than sense’.10 So Yeats absorbed himself in the symbolic landscapes of Spenser, Rossetti and Titian, where he found ‘forms of sensuous loveliness’ that were ‘separated from all the general purposes of life’.11 They supplied models for his early verse, of lake isles and Celtic myth, in which he began to come into a style of his own, ‘loosen[ing] rhythm as an escape from rhetoric and from that emotion of the crowd that rhetoric brings’ (A, p. 140).

While this is not the same as an escape from the crowd itself, that idea has nonetheless been important to Yeats’s critics – both those, like Ford Madox Ford and Eavan Boland, who have thought of his ‘distance’ from the contemporary as an irresponsible escapism (a tendency to ‘disappear’, in W. H. Auden’s phrase); and those, like Helen Vendler, who have wanted to divide a modernist Yeats’s ‘adult triumph’ from the naivety of his early poetry, attending to the former only to suggest its inferior relation to the latter, which is then said to have escaped, at least in part, the desire to escape.12 But Yeats spent almost all of his career addressing ‘the crowd’, and he was never unaware of the condescension of ‘The Realists’ (1912), who:

In reply, Yeats would disdain attempts ‘“to sum up” our time, as the phrase is; for Art is a revelation, and not a criticism’.13 And yet, as he argued in ‘The Autumn of the Body’ (1898), ‘modern’ poetry had left the procession: had forfeited the right to understand the world as ‘a dictionary of types and symbols and began to call itself a critic of life’, content to ‘interpret things as they are’ (EE, p. 141). It is in this context that ‘escape’ in Yeats’s early work comes to mean something more significant than has usually been allowed. From the Latin ex, meaning ‘out’, and cappa, meaning ‘cloak’, the word implies the casting away of an exterior which covers over or disguises. Escape of this kind is the guiding paradigm for Yeats’s symbolism, which promises the revelation of truths not bound by the senses, and visions of what, in his essay on ‘Magic’ (1901), he called the ‘truth in the depths of the mind when the eyes are closed’ (EE, p. 25). The Trembling of the Veil – a phrase borrowed from Stéphane Mallarmé, who wondered if his ‘epoch was troubled by the trembling of the veil of the Temple’ – is itself a title which relies on the metaphor intrinsic to the language of escape, suggesting the disturbance of a superficial outline and the revelation of some underlying reality.14 And indeed the period of Yeats’s life recalled in that volume is one marked, in his recollection, by an attempt to unmask ‘externality’, to sweep away that ‘Huxley, Tyndall, Carolus Duran, Bastien-Lepage bundle of old twigs’ (A, p. 149). The relationship between Yeats’s language of escape and his theories of symbolism is usually acknowledged only to his detriment; but it is more enlightening to observe how both aspects of Yeats’s early writings were shaped in response to impressionism.

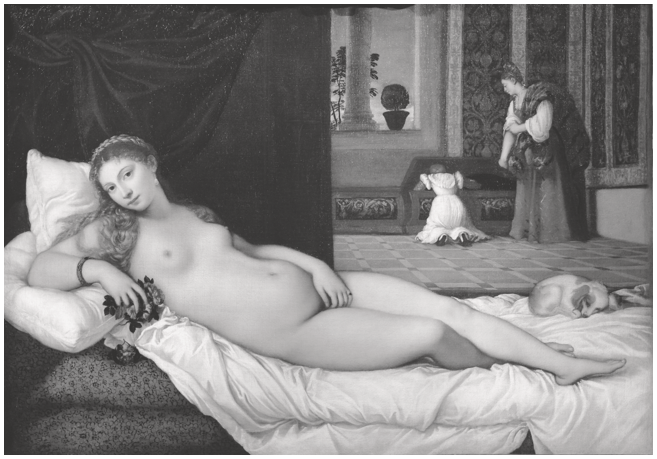

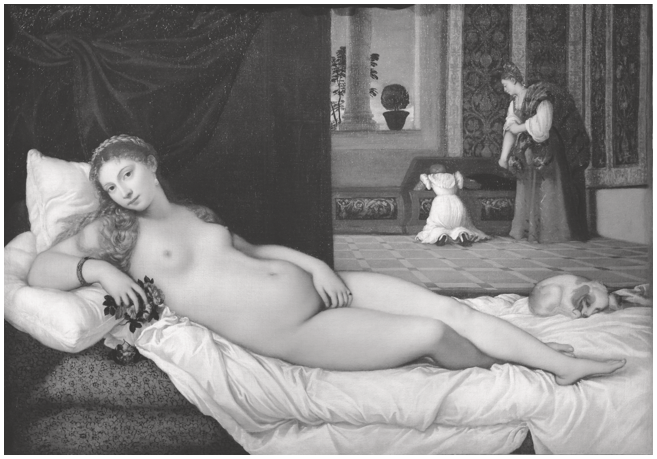

This is not a subject much treated in Yeats scholarship, which is surprising, because if ‘externality’ is the antithetical value against which his symbolism is defined, it is also the quality he most associated with ‘the new French painting’, and we can observe important shifts in Yeats’s thought which coincide with encounters with impressionist artworks in Paris and Dublin in the decades straddling the turn of the century.15 As the Autobiographies testify, his hopes for a visionary art which might supplant the twinned exteriorities of French painting and scientific positivism had been taking shape since art school, propelling his efforts, alongside Edwin Ellis, to prepare a three-volume edition of Blake’s writings (published in 1893). They received partial reinforcement in 1894 on his first visit to Paris, where Yeats attended a performance of ‘the Sacred Book I longed for’ (A, p. 246): the Axël (1890) of Villiers de l’Isle Adam. Newly receptive to its Rosicrucian mysticism following his initiation into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Yeats detected in Villiers’s visionary drama an ‘imaginative method’ wholly distinct from the ‘photographing of life’ he associated with ‘the new realism’, sharpening his desire for what, writing in The Bookman the following year, he called an ‘age of imagination’, when the arts would turn away from the ‘illusions of our visible passing life’, and those ‘many-coloured lights’, buried since the age of Titian and Veronese ‘in a great tomb of criticism’, might play once more about the ‘magical lamps of wisdom and romance’.16 A second encounter with the Parisian theatre in the winter of 1896 was less encouraging. With Symons he saw the opening of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi, which dispelled the optimism he had felt watching Villiers: ‘after Gustave Moreau, after Puvis de Chavannes’ – after all the ‘subtle colour and nervous rhythm’ of the artists Yeats thought were reviving the ancient symbolist procession – he despaired that ‘comedy, objectivity [had] displayed its growing power once more’ (A, p. 266). The gravest challenge to Yeats’s visionary aspirations came not in the theatre, however, but in the Musée du Luxembourg, which he seems to have attended on both trips (in his account of the period Yeats remembered returning to the gallery ‘again and again at intervals of years’ to stare in grim confusion; EE, p. 177).17 There he saw paintings by Carolus Duran, Bastien-Lepage, Renoir and the impressionists’ great ally, Édouard Manet – all exponents of the stark realism he despised, and whose ranks would be swollen (as he saw on later visits) by Monet, Degas, Sisley and Pissarro following the Caillebotte Bequest of 1897.18 Of the works on display, it was Manet’s picture of a nude Parisian prostitute, Olympia, which disturbed him most (1863, Figure 2.1). The painting did not elicit the same visceral disgust Yeats had felt on encountering Manet as an art student: by 1894 he had seen enough of the ‘new’ French painting (now thirty years old) not to be outraged, and was able ‘without hostility’ to observe the picture ‘as I might some incomparable talker whose precision of gesture gave me pleasure, though I did not understand his language’ (EE, p. 177). Yet Olympia seemed also to picture with appalling clarity the chasm between the art of Yeats’s own time and the more passionate, reverent art of the past. While he could make concessions to some of its forms of ‘precision’, Yeats’s pleasure was impaired by the painting’s precisely choreographed contrast to Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino’ (1538, Figure 2.2). The correspondence only served to highlight what he saw as Manet’s coarsening of the earlier picture’s heightened sensuality – a coarsening evident even in the sexual inuendo of Manet’s title – which is recast in a commercial setting hazardously proximate to a nineteenth-century (male) viewer’s historical vantage point.19 Not only that, but Manet had also eliminated half-tones and emphasised outline, so that in place of Titian’s loose impasto brushwork and diffused light, thick lines carved out Olympia’s grey hand and breast.

Figure 2.1 Édouard Manet, Olympia (1863), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Figure 2.2 Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Venus, known as ‘The Venus of Urbino’ (1538), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy.

Yeats own ‘dislike’ for the painting stemmed specifically from the ‘athletic spirit’ of its design (‘D’, p. 301). In this judgement he was invoking the Renaissance paragone, with its basic opposition of colore to disegno: of the Venetian oil works of Titian and Giorgione to the vivid Florentine designs of Michelangelo and Raphael; of complex colour tones to muscular outlines. In France, the dispute had found rancorous expression in the seventeenth-century quarrel between Rubénistes and Poussinistes – a debate with which Yeats was familiar through Balzac’s story about Poussin entitled ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ (1831) – but it was given a new lease of life in the French art press after Olympia was unveiled in 1865. Manet’s painting caused outrage not just for its dismantling of the setting of Titian’s idealised erotic vision, but also because of its dramatic departure from the style of the earlier painting, whose softened curves and twilit flesh find a provocative counterpoint in Manet’s thick bounding lines and artificial studio light. As T. J. Clark has shown, initial responses seized immediately on the ugly flatness of its outlines. The painting was described as ‘circled in black’ and mangled by ‘stripes of blacking’, as though incised with coal.20 Edmond de Goncourt complained of its assault on the Titianesque:

With Manet [what] we have is the death of oil painting, that’s to say, painting with a pretty, amber, crystalline transparency[.] Now we have opaque painting, matte painting, chalky painting, painting with all the characteristics of furniture paint. And everyone’s doing it like that, from Rafaelli to the last little Impressionist dauber.21

Symons would more favourably compare Manet’s ‘hard outlines’ to the sharply drawn portraits of the French bourgeoisie that he had discovered in the novels of Flaubert, but Amédée Cantaloube gave succinct expression to the consensus among Olympia’s earliest critics when he characterised her as a ‘female gorilla, a grotesque in India rubber outlined in black’ who ‘apes’ the ‘horizontal attitude of Titian’s “Venus”’.22

Yeats’s views on the issue of line hardened significantly in the months following his first visit to the Luxembourg. On returning from Paris, he began work on an essay about Blake’s illustrations to The Divine Comedy (published in The Savoy in the summer of 1896). In his editorial role he had wrestled privately with Blake’s hatred of Titian, but the trip to France compelled him to dissent from his visionary master. In the vellum-bound copy of Blake’s Works that Yeats had beside him while writing the essay, long marginal strokes appear beside the passages in which Blake denigrates the Venetian painters, especially Titian.23 As Blake recalls in one heavily underscored section of the Descriptive Catalogue (1809), Titian ‘was particularly active in raising doubts’ in his mind while he was attempting to paint Milton’s Satan, the muddied design of those illustrations (as he saw it) being the result of ‘temptations and perturbations’ put in his path by the ‘Venetian and Flemish Demons’, whose ‘blots and blurs’ put him in doubt of his ‘original conception’.24 As Blake remarks, Titian and Rubens were enemies ‘to the Painter himself, and to all Artists who study the Florentine and Roman Schools’: ‘They cause that execution shall all be blocked up with brown shadows.’25 In another marked paragraph he suggests that ‘everything in art is definite and determinate [because] Vision is determinate and perfect’, arguing on this basis (this time in a phrase which finds its way into Yeats’s essay) that ‘the more distinct, sharp, and wiry the boundary-line, the more perfect the work of art; and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak imitation, plagiarism and bungling’.26 Accordingly, Titian comes in Blake’s writings to be referred to as the ‘spectrous fiend’, whose loosened brushstrokes and layered velatura – those famous veils of shimmering, glaze-soaked oil – had obscured the lineaments of the divine Imagination.27 In his 1893 ‘Introduction’ to Blake’s poems, Yeats had summarised Blake’s broader argument:

We must take some portion of the kingdom of darkness, of the void in which we live, and by ‘circumcising away the indefinite’ with a ‘firm and determinate outline’, make of that portion a ‘tent of God’.28

But he stops short of assenting to this argument himself. Yeats’s absorption of Blake’s visionary precepts has persuaded one critic that Yeats’s own theories of visionary style must also follow his example in privileging ‘the separation of form by the wiry, bounding line’.29 In fact, the reverse is true. In his ‘Introduction’, Yeats acknowledges Blake’s belief that ‘to cover the imperishable lineaments of beauty with shadows and reflected lights was to fall into the power of his Vala, the indolent fascination of nature’, and that Titian’s ‘dots and lozenges’ and ‘indefinite shadows’ ‘took upon them portentous meanings to his visionary eyes’, which preferred the sharply inscribed outlines of Michelangelo and Raphael.30 In his essay on Blake’s illustrations, however, this mildly sceptical neutrality develops into positive counterargument. Again Yeats summarises Blake: ‘he believed that the figures seen by the mind’s eye, when exalted by the inspiration, were “eternal existences”, symbols of divine essences, [and so] he hated every grace of style that might obscure their lineaments’. Yet he also resists Blake’s withering judgements on the Venetians, suggesting that a too dogmatic association of divine beauty with firm outline had made him insensible to the visionary potential of Titian’s glimmering colour and light:

He refused to admit that he who wraps the vision in lights and shadows, in iridescent or glowing colour, until form be half lost in pattern, may, as did Titian in his ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’, create a talisman as powerfully charged with intellectual virtue as though it were a jewel-studded door of the city seen on Patmos.

Blake’s antipathy towards Titian, Yeats began to insist, was a consequence of the ‘intensity of his vision; he was a too literal realist of imagination, as others are of nature’ (EE, p. 90).

That last clause marks a subtle but crucial progression in Yeats’s readings of Blake which illuminates the significance of his early association of vision with the dissolution of outline. His change in tone has little to do with Yeats’s sense of the importance of Blake’s visions, which remained crucial touchstones throughout his career. Rather, it reflects Yeats coming into a new certainty in his conception of symbolic form, which not only is in tension with Blake’s, but also produces his startling suggestion that a ‘too literal’ fidelity to the imagination had bonded Blake’s visionary style to the same painters he had accused of ‘indolent’ fascination with the fractured outlines they saw in ‘the vegetable glass of nature’.31 This clarification of Yeats’s stylistic priorities occurs after he saw Manet’s Olympia, and it is here that the most important effects of his encounters with the new French painting begin to tell. In his criticism, it led him to turn away from ‘the hard and wiry line of rectitude’ favoured by Blake, which he felt had been given contemporary (if less virtuous) expression through the painting of Manet and his impressionist followers, and to privilege instead the iridescent glow of Titian. In his verse, it prompted him to couple effects of glimmering colour and light with ‘loosened’ rhythms which escape the ‘rhetorical’ monotony of the regular verse line.

This new emphasis in Yeats’s thinking became increasingly pronounced as further trips to Paris in late 1896 and early 1898 brought him back to the Luxembourg, prompting him to elaborate his position. In his essay on ‘Symbolism in Painting’ (1898), for example, Yeats implicitly extends his argument with both Blake and Manet:

All Art that is not mere storytelling, or mere portraiture, is symbolic, and has the purpose of those symbolic talismans which mediæval magicians made with complex colours and forms; and bade their patients ponder over daily, and guard with holy secrecy; for it entangles, in complex colours and forms, a part of the Divine Essence.

Besides having an occult flavour picked up from the talismanic rituals Yeats was undertaking with the Golden Dawn, the language here is of entanglement and complexity. He is drawn to the unifying patterns of shimmering colour that characterised ‘the religious art of Giotto and his disciples’, but which found only scattered expression in the ‘fragmentary symbolisms’ of their modern descendants (Keats, Calvert), and which had been broken up further – obliterated, even – by the new French painting and the lyric forms it had inspired (EE, p. 110). Returning to the opposition of firm outline to ‘complex colour’ a few months later in ‘The Autumn of the Body’, Yeats is drawn again to the ‘tremulous bodies’ of recent French symbolist painting, the ‘faint lights and faint colours and faint outlines’ of which seemed to betoken a resurgence, in another occult formulation, of ‘many things which positive science, the interpreter of exterior law, has always denied: communion of mind with mind in thought and without words, foreknowledge in dreams and in visions, and the coming among us of the dead’ (EE, p. 141). (He does not specify the painters he has in mind, but he may be thinking of Gustave Moreau, of whom Yeats was aware from his visits to the Luxembourg as well as the recommendations of his friend Charles Ricketts, and whose Licornes (c. 1885) – or a copy of it – hung in his study.32) Yeats characterises this ‘tremulous’ quality as a mark of their place in a visionary order of artists at the head of which stands Titian: the tremulousness of their pictorial personae, that is to say, becomes a sign of their place in a stylistic tradition ‘where subtle rhythms of colour and of form have overcome the clear outline of things as we see them in the labour of life’ (EE, p. 140).

While it might be objected that effects of this kind are in some ways distinctively impressionist – Yeats’s description of colour rhythms overcoming the outlines of things would apply to any number of paintings by Monet or Pissarro (for example) – it is an early sign of the dogmatic vein in Yeats’s temperament that his hostile characterisations of ‘the new French painting’ carefully exclude painters who do not conform to the oppositional architecture of his thought. (As Ezra Pound remarked, ‘The man among my friends who is loudest in his sighs for Urbino, and for lost beauty in general, has the habit of abusing modern art for its “want of culture”. [It] is chiefly the Impressionists he is intent on abusing, but like most folk of his generation, he “lumps the whole lot together”’; GB, p. 104). Yeats’s criticisms tend instead to be aimed at those who prefigured the technical innovations of impressionism (Manet) or shared its interest in the science of perception and ‘the labour of life’ (Bastien-Lepage), or both, and whose naturalistic glimpses of the disintegration of modern life are said to have broken outline in the wrong way, as if by chasing the random sensations of the visible world they had cast their vision down into shards rather than ‘entangled’ it, through ‘complex’ patterns of colour, with the Divine. Yeats’s preferred symbolic art, by contrast, combined spiritual revelation with softened outline and glowing colour or light – stylistic configurations which are also detected in the writings of his favoured contemporaries. Villiers, for example, had wrought elaborate patterns of ‘words behind which glimmered a spiritual and passionate mood, as the flame glimmers behind the dusky blue and red glass in an Eastern lamp’, while Maeterlinck had given voice to beings so faint in outline that they resembled ‘shadows already half vapour and sighing to one another upon the border of the last abyss’ (EE, pp. 139–40). And all of this seemed, to Yeats, to portend a cataclysmic event, perhaps even ‘the crowning crisis of the world’, when ‘man is about to ascend, with the wealth, he has been so long gathering, upon his shoulders, the stairway he has been descending from the first days’ (EE, p. 141). Alongside this moment of spiritual ascent, Yeats predicted a parallel change in ‘the manner of our poetry’, feeling that his generation would ‘come to understand that the beryl stone was enchanted by our fathers that it might unfold the pictures in its heart, and not to mirror our own excited faces, or the boughs waving outside the window’.33 As he remarked in ‘The Symbolism of Poetry’ (1900), there would be ‘a casting out of descriptions of nature for the sake of nature’, and the coming in their place of a poetry which would ‘escape analysis’ (EE, p. 120).

It is significant that the phrase should reappear here. It reiterates Yeats’s dismissals of empirical analysis, clearly, but what is more important is the way in which it establishes two sets of opposed attributes that correspond to the paragone, and which show the hidden sense of ‘escape’ – of trembling surfaces and unveiled truths – acquiring a technical counterpart. Instead of opposing strongly engraved outlines to softened dots and lozenges, in defining a poetry which might ‘escape analysis’, Yeats, in a quite literal way, transfers the opposition to matters of prosody, so that the argument becomes one of poetic rather than pictorial line. Thus, ‘with this change of substance, this return to imagination, [would] come a change of style’:

we would cast out of serious poetry those energetic rhythms, as of a man running, which are the invention of the will with its eyes always on something to be done or undone; and we would seek out those wavering, meditative, organic rhythms, which are the embodiment of the imagination, that neither desires nor hates, because it has done with time and only wishes to gaze upon some reality, some beauty […]

Just as Yeats would associate ‘athletic’ outline with the new French painting and contrast this with the glimmering light and prismatic colour tones he found in Titian and Tintoretto, here he opposes the ‘energetic’ rhythms of the will to those wavering rhythms which, ‘hushing us with an alluring monotony’ even while they ‘[hold] us waking by variety’, ‘keep us in that state of perhaps real trance, in which the mind liberated from the pressure of the will is unfolded in symbols’ (EE, p. 117).

The second species of rhythm Yeats had been employing haphazardly almost from the outset of his poetic career. The classic early example would be ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ (1890) – the ‘first lyric’, Yeats remembered, in which ‘I had begun to loosen rhythm’ (A, p. 139) – in which a fluctuating blend of long and short lines conveys an imaginative flight from ‘pavements grey’ to a Celtic Walden. There midnight ‘glimmers’ with a surreal luminescence and noon darkens in ‘a purple glow’, as if the poem’s habitat existed beyond the ‘push’ of time itself (VP, p. 117). This effect is both paralleled and engendered by Yeats’s wavering rhythms, which unfold languorously across each quatrain’s trio of heptameter and hexameter lines before modulating into a concluding tetrameter. Writing discerningly of its languid measure, Angela Leighton has suggested that ‘Innisfree’ leaves us ‘rhythmically marooned in a lotos-eating island-time which beautifully enacts the place that is imagined’, such that the poem’s subject is ‘lost in the drawn-out pause of its own writing’.34 And indeed for those who have wished to portray Yeats as an escapist, what Leighton calls the poem’s ‘slowed-up measure of artistic escape’ and imagined locale have made it the paradigmatic example of Yeats’s most egregious tendencies.35 But this has obscured the extent to which ‘Innisfree’ is also self-consciously a form of escape, one whose wavering rhythms and iridescent shimmer fit into a wider pattern of aesthetic preferences in which Yeats is repeatedly drawn to different kinds of trembling and diffused outline.

That pattern was already taking shape before Yeats’s visits to Paris, as ‘Innisfree’ demonstrates, but it becomes clearer after his trips abroad and while he was editing Blake. In The Countess Cathleen and Various Legends and Lyrics (1892) – and particularly in the lyrics which aim to induce a trance-like state in which the mind is susceptible to symbols, later revised and regrouped as The Rose (1895) – Yeats eschews the ‘energetic’ tramp of regular metre, preferring the looser, more hypnotic rhythms of what, in ‘To Ireland in the Coming Times’, he calls a ‘measured quietude’ (VP, p. 137). In turn, these subtler rhythms become subjects of the poems they sustain, often being suggestively allied with the emphasis on iridescent light and colour which emerges from his writings about Titian. We might think of the ‘rose-breathed’ melody invoked and realised by ‘To the Rose upon the Rood of Time’, with its inversions and incantatory repetitions, whose speaker aspires to ‘hear the strange things said / By God to the bright hearts of those long dead, / and learn to chaunt a tongue men do not know’ (VP, p. 100). Or the undulant rhythms of ‘The White Birds’, in which extravagantly long anapaestic lines convey a glowing twilit dream-vision – what Hannah Sullivan calls an ‘escapist, flyaway fantasy’ – of a space beyond time, metrical or otherwise (‘a Danaan shore, / Where Time would surely forget us’; VP, p. 122).36 Or the pairing of softly treading feet – the poem punning on its variable tetrameter – and ‘glimmering’ divine light in ‘The Countess Cathleen in Paradise’ (VP, p. 125).

Those glimmering lights and meditative rhythms are often said to be the key stylistic signatures of Yeats’s symbolist verse. Indeed, in ‘Speaking to the Psaltery’ (1907), Yeats described the two effects as though they were inseparable, remarking that ‘rhythm [is] the glimmer, the fragrance, the spirit of all intense literature’ (EE, p. 17). In due course, they would also become fused in the minds of his readers. Both effects impressed themselves indelibly on James Joyce, for example, who, after hearing Anna Mather chant ‘Who Goes with Fergus?’ in 1899, tried to set Yeats’s verse to music; and later remembered the ‘ardent roselike glow’ and ‘murmuring[,] rhythmic movement’ of Yeats’s lyrics in Stephen Dedalus’s visionary villanelle in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916).37 And they have struck, too, upon contemporary scholars of Yeats, who often identify a reciprocity between the shimmering, dream-like vagueness of the early poetry’s visual effects – in which the outlines of things are softened by ‘rose-heavy’ atmosphere (VP, p. 162) or the ‘flicker and glow’ of twilight and candle flame (p. 150) – and its tendency to blur fixed metrical divisions, either by employing ‘a fixed metre [which] is set up only to dissolve’ or by departing from accentual-syllabic norms altogether.38 What is less often noticed, however, is the extent to which this stylistic coalescence came to predominate in Yeats’s verse just as he was wrestling with Manet’s assault on the Titianesque. Confronted with Olympia’s aggressive contours and sexual coarseness, Yeats not only deepened his investment in the imaginative resources of Irish myth and the occult, but began more determinedly to express his visionary interests through forms of rhythmical diffusion and wavering outline. Where such effects are incubating in The Countess Cathleen, in the poems collected after his visits to the Luxembourg and his break with Blake on Titian and line, they are everywhere – particularly in those lyrics which are concerned with forms of immortal song or ecstatic vision (or both). They are a pronounced feature of ‘The Everlasting Voices’ (1896), for example, a poem composed in the immediate wake of Yeats’s first trip to Paris, and later forming part of a group of visionary lyrics at the heart of The Wind among the Reeds (1899) which experiment with the unmoored cadences of French syllabic verse.39 Thus, the wandering, flame-lit spirit voices who ‘call in birds, in wind on the hill, / in shaken boughs, in tide on the shore’ find themselves echoed by the ‘organic’ internal rhythms engendered by Yeats’s mounting, incantatory syntax (VP, p. 141). Likewise, in ‘The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers’ (1898), ‘Great powers of falling wave and wind and windy fire’ are asked to unfold, paradoxically, in a ‘gentle silence wrought with music’. Offering itself as oblation, the poem is wrought out of pairs of full lines and rhyming half-lines which not only lodge within the poem’s structure the deferential attitude of a poet shadowing ‘Powers whose name and shape no living creature knows’, but also create a rhythmical counterpoint which casts swaying shadows of sound across entire stanzas, encircling the poem with cinctures of rhyme (‘rings uncoiled from glimmering deep to deep’; VP, p. 174). Such poems enact what Allen R. Grossman calls Yeats’s ‘trance style’, which he characterises as an effort to escape or variegate ‘theoretical metrical’ distinctions, and which he associates with the various learned techniques of reverie that Yeats incorporated in his private experiments with the Cabbala.40 In The Wind among the Reeds, it is the style characteristic of lyrics that witness the unveiling of perfect or ideal forms – lyrics whose speakers might be describing Titian’s Venus herself, as when Aengus is struck beneath ‘moth-like stars’ by a vision of a voluptuous ‘glimmering girl’ whose outlines are cast upon the ‘dappled grass’ and fade ‘through the brightening air’ (‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, VP, p. 150); or when a mourning lover is arrested by flickering images of rose-adorned ‘dreaming ladies’ from ‘A more dream-heavy hour than this’ (‘He remembers Forgotten Beauty’, VP, p. 156) and again, later in the collection, by ‘Queens wrought with glimmering hands’ in ‘dove-grey faery lands’ (‘The Lover asks Forgiveness’, VP, p. 162).

The new emphasis in Yeats’s verse was noticed by Arthur Symons, who was then living with him in Fountain Court, and who in May of 1899 composed an appreciative review of The Wind among the Reeds for the Saturday Review. Symons praised in particular the collection’s suppleness of rhythm, comparing the slowed-up cadences of Yeats’s lyrics to ripples and waves, analogies which suggest both the disturbance of surface and the bending or dispersal of line:

He has made for himself a rhythm which is more natural, more precise in its slow and wandering cadence, than any prose rhythm. [How] few, it annoys me to think, as I read over this simple and learned poetry, will realise the extraordinary art which has worked these tiny poems, which seem as free as waves.41

Indeed, in the dedication to The Symbolist Movement that Symons wrote a month later, he identified Yeats as ‘the chief representative of that movement’, which in his characterisation sought a ‘softening of atmosphere’ and an escape from ‘definite outline’; and, in verse, had brought about a ‘breaking up of the large rhythms of literature, and their scattering in articulate, almost instrumental, nervous waves’.42 Of course, it would be wrong to attribute the evolution of Yeats’s symbolist poetics solely to his early encounters with French painting (encounters which, ironically, Symons played a part in facilitating). What is clear, however, is that those meetings decisively shaped the broader set of artistic priorities into which his first experiments with rhythm fit, and that the binaries which govern the manner of the early poetry – of glimmering colour against hard outline, the meditative against the energetic – find their sharpest expression, for Yeats, in the opposed visions of the Renaissance and the late nineteenth century.

Perhaps the exemplary poetic instance of Yeats measuring these two kinds of vision against each other is ‘The Two Trees’ (1892). Published just as Yeats was contending with Blake’s dismissals of Titian, the poem employs its titular symbols – the cabbalistic Tree of Life and the dead Christian Tree of Knowledge – to set the bountiful fixedness of an illuminating ‘gaze’ against the ‘barren’ contingency of a manner of looking which merely reflects the world around it.43 ‘The changing colours’ and ‘trembling flowers’ of the first tree’s fruit dower ‘the stars with merry light’ in a manner that prefigures the tapestries of glowing colour shortly to be found in Yeats’s criticism. Likewise, reverie and a certain kind of murmuring rhythm are paired:

After its opening inversion, the poem’s first stanza settles into a regular iambic pattern which reflects ‘the surety of its hidden root’, only to waver – ‘Tossing and tossing to and fro’ – as it unfolds in a vision of the speaker’s beloved gazing into her own heart (VP, pp. 134–5). In the second half of the poem, the metre becomes more ragged, breaking up into trochaic lines and lines knotted by hard-edged, alliterative clusters of stress (‘Cruel claw’, ‘broken branches’, ‘broken boughs’). At the same time, we find an association of ‘externality’ with ‘realism’ already forming. The speaker cautions against looking into the second tree’s ‘bitter glass’ of knowledge, ‘the glass of outer weariness’:

As Peter McDonald argues, the barren glass not only calls to mind Blake’s ‘vegetable glass of nature’, across which stream the second-order shadows of the Imagination’s ‘Permanent Realities’, but seems also to serve as an emblem of what Yeats elsewhere terms ‘art that we call real’ (EE, p. 177). ‘The bitter glass’, he suggests, ‘may well stand here for all of the realist aesthetics [that] Yeats associated with the nineteenth century – “a mere dead mirror on which things reflect themselves”’.44 Such passive reflection is actively harmful: harassed by external disorder, ‘unresting thought’ agitates the mind in a manner consonant with Yeats’s glosses of ‘vitality’, that ‘great word of the studios’, which binds itself to the world of ‘outer weariness’ and ‘laughs, chatters or looks its busy thoughts’ in a correspondingly exhausting fashion (EE, p. 179). Indeed, according to the iconography of Yeats’s thought, the broken ‘bundle of old twigs’ reflected in the poem’s ‘dim glass’ belongs properly to the corner of a Bastien-Lepage canvas, or a Manet.

The correspondence between the thematic dualism of Yeats’s poem and his writings about modern painting is not coincidental. ‘The Two Trees’ is a concentrated illustration of how Yeats’s symbolism was defined at least partly – and in the case of that poem almost literally – in opposition to a way of seeing he associates above all with impressionism, which he always describes in terms of the passive reflectivity of the mirror or glass. It is no accident that the language of the poem echoes his most emphatic rallying cries for symbolic art. Nor is it a coincidence that Yeats’s most trenchant defences of the artistic imagination should greet the arrival in Ireland of the dismally veristic French painting he had hoped his generation might escape, and which he invariably dismisses on grounds of its superficiality and shallowness.

In 1898, Yeats’s friend AE (George William Russell) called for the first loan exhibition of modern French painting in Dublin, which led eventually to Hugh Lane’s major exhibition of the French impressionists and the Barbizon School at the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1904. The show displayed over 300 paintings, including works by Manet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Monet, Whistler and Sisley – some of which Lane had acquired himself, and some of which he borrowed from Paul Durand-Ruel, who would then transport them to London for his exhibition at the Grafton Galleries the following year.45 This was the first time Irish audiences had been exposed to impressionist art, and so Lane arranged for Moore – along with J. B. Yeats, whose son sat beside him on the lecture platform – to give a series of public talks about the pictures. Moore delivered his famous lecture about his time in Paris in the 1870s, entitled ‘Reminiscences of the Impressionist Painters’, in which he eulogised the painters he had known at the Café Nouvelle Athènes.46 ‘We moderns no longer feel and see like the ancient masters’, he informed the lecture hall: in the New Athens, ‘Manet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Monet, and Sisley [were] our masters’, and these masters saw clearly. Manet in particular was ‘the great new force in painting’; he had ‘a vision in his eyes which he calls nature’, and ‘declares vehemently that the artist [should] paint merely what he sees’.47 To Moore, Yeats’s imagined persons were illusions to be disabused of, fantastic screens which in France had been swept away to illuminate nature in its naked truth. He reserved special praise for Manet’s portrait of Eva Gonzalès (1870, Figure 2.3), which, he declared, ‘is as unashamed as Whitman’. ‘The portrait of Mademoiselle Gonzalès is what Dublin needs’, Moore argued, because it will engender ‘the crisis we are longing for – [where] men shall return to nature naked and unashamed’. It had taken ‘fifteen years for the light of Manet’s genius to reach Ireland’, but the veil was starting to lift on the radial Parisian vortex: ‘A gallery of Impressionist pictures would be more likely than any other pictures to send a man to France, and that is the great point. Everyone must go to France.’48 For Yeats, listening from the stage, Moore’s speech brought to mind memories of art school. Testifying before a Commission of Inquiry into the Metropolitan School’s curriculum a year later, Yeats characterised Moore’s Francophilia as having been endemic when he had been an art student in the 1880s, recalling that ‘every student, at the time I spoke of, was trying to get away [from Ireland]’ – with, perhaps, a wry implication that this was a form of actual escapism.49 What struck him most of all, however, was the paucity of the kind of vision Moore was describing. Immediately after the lecture, Yeats questioned whether Moore was too concerned with ‘outer appearance’ and not enough with ‘internal reality’, as if to imply something impoverished and false about the mimetic procedures of his new masters by comparison with the imaginative vision of their forebears.50

Figure 2.3 Édouard Manet, Eva Gonzalès (1870), National Gallery, London, UK.

In the years that followed, Yeats would subjugate his private reservations to the public cause of Irish cultural advancement, lending his support to Lane’s plans for a Municipal Gallery of Modern Art – opened in 1908 – and later rebuking the Dublin Corporation when it refused to fund a separate gallery to house Lane’s personal collection of French painting.51 However, he experienced no personal revelation of the sort Moore describes through his encounter with Manet’s Gonzalès. Indeed, as Ronald Schuchard notes, the only complete satisfaction Yeats ever professed to derive from Manet was on discovering his caricature of Moore at the Nouvelle Athènes, in which Moore appeared like ‘a man carved out of a turnip, looking out of astonished eyes’ (A, p. 302).52 Moore’s lecture seems in fact to have reinforced Yeats’s disregard for impressionist art, intensifying his feeling that impressionism was too superficial, too much in thrall to what he referred to as ‘mere reality’ (A, p. 92). He would make barbed remarks about the ‘impressionist view of art and life’ of Symons, for example, who ‘with a superficial deduction I suppose from the chapter in Marius called “Animula Vagula”’ pursued nothing but ‘vivid impressions for his verse’, begetting an ‘unimaginative art’ content (or determined) to present a ‘piece of the world as we know it’, like ‘a photograph’, with the implication that Symons’s interest in Degas and Whistler had degraded Pater’s philosophy of intensely illuminated moments so that it more closely resembled the reflective aesthetics of the French painters (A, p. 356).53 But perhaps the most important iteration of this complaint appears in a crucial second set of ‘Discoveries’ composed in 1908, in which Yeats recalls finding on a table at the Hibernian a copy of Camille Mauclair’s recently translated study The French Impressionists (1903). He was struck especially by Mauclair’s triumphant suggestion that impressionism ‘has inflicted an irremediable blow on academic convention and has wrested from it the prestige of teaching which ruled tyrannically for centuries past over the young artists. It has laid a violent hand upon a tenacious and dangerous prejudice, upon a series of conventional notions which were transmitted without consideration for the evolution of modern life and intelligence.’54 Yeats wearily acknowledged Mauclair’s claim that the impressionists had ‘brought a complete renewal of pictorial vision [based] upon irrefutable optic laws’, but he also found himself remembering ‘some of my first dislike of Manet. I have read books on modern painting to remind myself of old studio talk as much as to learn the thoughts of better students, for all my life I have listened to the argument Mauclair describes’ (‘D’, p. 302).55 That note of exasperation betrays an impenitently ‘romantic’ strain in his thinking about art. In the painters he loved he found a ‘balance of form and feature inherited from the artists of the past – measurements made at the rediscovery of the antique and written out in books by Dürer and Da Vinci’. Against this, ‘Impressionism, modern art, had been the revolt.’ While Yeats could accept that the old style had sometimes ossified into ‘academic form’, he remained ambivalent about the French painters who had chosen to see ‘with the eyes alone’ and ‘without premeditation, without help or hindrance from deliberate thought’ (‘D’, pp. 302–3).

There are two important things to notice here. The first is that while impressionism is usually thought to involve the mediation of sense data by the personality of the artist, in Yeats’s thought it is construed as a kind of sheer empiricism, in which ‘the soul becomes a mirror not a brazier’ (A, p. 352). The second is that this criticism is always conveyed in Yeats’s writings by analogy with the imaginative vision of the Renaissance, so that where the Italian painters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are said to have been guided by the ‘inspiration of the past’, the new orthodoxy was that ‘a canon, the idea of limitation at all, was the enemy’ (‘D’, p. 302). The new dogma in both painting and verse was that every work should shed the trappings of myth, religion and tradition in order to express as distinctly as possible the immediate sensations of its creator:

Only when all that past had faded could the individual mind as it expresses itself through the senses express itself perfectly. Every painting was to be the perfect expression of a man[.] His vision of reality, that alone concerned him, and in my own art, there too we have discovered impressionism. We [are] proud only of the discovery of new material and of an impression of modernness.

In both poetry and painting, paradoxically, impressionism was at once too exterior, too concerned with the appearance of things to the perceiving self; and yet also, for this reason, too inward, too absorbed in sensations particular to the individual, and, thus, isolated from the communal language of symbol and myth. As Yeats concluded, somewhat dismally, ‘We are discovering always in our work what makes us different from all other men’ (‘D’, p. 303).

It is for this reason that impressionist ‘exteriority’ acquires its portentous significance in Yeats’s writings, which repeatedly turn to the visionary and symbolic art of the past for inspiration. In particular, what he perceived as impressionism’s isolating emphasis on the individual mind (‘abstraction’) and its too literal fidelity to the accidence of the senses are the twin defects that Yeats sought to correct with the ideal forms of the Renaissance. Thus, in the wake of his initial encounters with Manet’s Olympia, he turned to composing ‘The Celtic Element in Literature’ (1897), in which he described the Celtic Movement as a reopening of the ‘fountain of legends’ that had informed European art since the age of Dante, claiming that art ‘dwindles to a mere chronicle of circumstance [unless] it is constantly flooded with the passions and beliefs of ancient times’ (EE, pp. 135–7). Aggravated by Lane’s exhibition of 1904, he sought refuge among the Venetian painters in the National Gallery, where the ‘glowing and palpitating flesh’ of Tintoretto’s Origin of the Milky Way (1575) – which, tellingly, he confesses ‘I am too modern fully to enjoy’ – prompted him in his diaries to compare the Old Master with his ‘scientific’ descendants:

He had never seen like a naturalist, never seen things as they are, [and] nearly all the great men of the renaissance, looked at the world with eyes like his. Their minds were never quiescent, never as it were in a mood for scientific observations, always in exaltation[;] and their attention and the attention of those they worked for dwelt constantly with what is present to the mind in exaltation.

In the set of ‘Discoveries’ he published in 1907, for which the diaries formed the basis, Yeats restated his belief that the true artist ‘stands between the saint and the world of impermanent things, and just in so far as his mind dwells on what is impermanent in his sense, [will] his mind grow critical, as distinguished from creative, and his emotions wither’ (EE, p. 208). In the same series of essays, Yeats claims that the artist in thrall to the transient chaos of the senses will ‘lose rhythm’, before suggesting that the impressionist painters had exemplified this tendency to the point of amnesia, seeming to wind the veil more tightly round themselves: ‘We all feel the critic in Whistler and Degas’, ‘in much great art that is not the greatest of all’, for ‘that which is before our eyes perpetually vanishes and returns again in the midst of the excitement it creates’ – ‘the more enthralling it is, the more do we forget it’ (EE, pp. 208, 179). There are concessions to its technical virtuosity, but the new French painting falls short of Yeats’s definition of the true ‘end of art’, which ‘is the ecstasy awakened by the presence before an everchanging mind of what is permanent in the world’ (EE, p. 208).

Perhaps the major permanent value that Yeats thought had been shrouded over by impressionist ‘quiescence’ was what he called ‘unity’ – the ideal which underpins all his early writings, and the quality he most prized in the art of the Renaissance. Like Eliot, Yeats would be haunted by the idea of Europe as an organic unity that had broken apart and degraded, falling into the individualism, materialism and secularism of a debased modern age. Yeats tended to date the onset of this disintegration earlier than Eliot, so that rather than setting in after the deaths of Donne and Marvell, the etiolating effects of modernity are instead supposed to have begun in the latter parts of the sixteenth century – with the death of Titian, after which ‘painting parted from religion [that] it might study the effects of tangibility undisturbed’, eventually forfeiting the ‘all-enfolding sympathy’ that had characterised the Quattrocento and early Cinquecento. In Yeats’s version of the story, which seems to borrow some of its outline from Ruskin’s more hostile descriptions of the Renaissance as the pivotal catastrophe in the history of modernity, ‘Europe [had] shared one mind and heart, until both mind and heart began to break into fragments a little before Shakespeare’s birth’ (A, p. 165).56 Partly because Olympia seemed so starkly and self-consciously to embody the degradation of the Renaissance canon, Yeats’s encounters with the pictures of Manet and the new French painters not only impressed upon him the sense that this process of fragmentation had reached its apex in the late nineteenth century, but also called to mind the proportion and wholeness of art forms belonging to a more integrated culture:

A conviction that the world was now but a bundle of fragments possessed me without ceasing. I had tried this conviction on the Rhymers, thereby plunging into greater silence an already too silent evening. I had been put into a rage by the followers of Huxley, Tyndall, Carolus Duran, and Bastien-Lepage, who not only asserted the unimportance of subject whether in art or literature, but the independence of the arts from one another. I delighted in every age where poet and artist confined themselves gladly to some inherited subject matter known to the whole people, for I thought that in man and race alike there is something called ‘Unity of Being’, using that term as Dante used it when he compared beauty in the Convito to a perfectly proportioned human body.

Signifying both design and kinship, unity is what the early poetry attempts to salvage from a process of ‘modern’ division, of which an exclusive fixation on ‘the individual mind as it expresses itself through the senses’ was, for Yeats, the major aesthetic symptom. As he remembered in ‘Art and Ideas’ (1913), an essay which recounts his time with the Rhymers in the 1890s, ‘the manner of painting had changed, and we were interested in the fall of drapery and the play of light without concerning ourselves with the meaning, the emotion of the figure itself’, so that painters ‘gave their sitters the same attention, the same interest they might have given to a ginger-beer bottle’ (EE, p. 255). Likewise, ‘among the little group of poets that met at the Cheshire Cheese’, ‘all silently obeyed a canon that had become powerful for all the arts since Whistler [had] told everybody that Japanese painting had no literary ideas’ (EE, p. 255). The effects of this apprenticeship to the new French painting were deleterious. ‘An absorption in fragmentary sensuous beauty’ had ‘deprived us of the power to mould vast material into a single image’, Yeats argued, with the result that their poems lacked ‘architectural unity’ and ‘symbolic importance’. Even the short lyrics ‘which contained as clearly as an Elizabethan lyric the impression of a single idea seemed accidental, so much the rule were the “Faustines” and “Dolores” where the verses might be arranged in any order, like shot out of a bag’ (EE, p. 255).

Against the ‘fall of man into his own circumference’, Yeats repeatedly insisted that ‘great poets’ speak to us ‘of mankind in [its] fullness; because they have wrought their poetry out of the dreams that were dreamed’ before ‘every man grew limited and fragmentary’.57 This conviction underlay his admiration for the inherited ‘balance of form’ he found in the Italian Renaissance and propelled his interest in Ireland’s mythic iconography, each being unified repositories of ancient wisdom which he hoped would lend their durability and coherence to the individual adrift in the wash of time. Lamenting ‘the religious change which followed on the Renaissance’, after which a reverence for the ‘symbols of antiquity’ had given way to a creeping ‘individualism’, Yeats ‘filled [his] imagination with the popular beliefs of Ireland’, searching for ‘some symbolic language reaching far into the past’ in order ‘that I might not be alone amid the obscure impressions of the senses’ (EE, pp. 252–4).58 Anticipating the arrival of French painting in Dublin, Yeats composed his famous essay on ‘Magic’ (1901), in which he insisted on an invisible totality that the sensory carnival of the impressionists had obscured, setting out three doctrines ‘which have, as I think, been handed down from early times’: ‘That the borders of our minds are ever shifting, and that many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind’; ‘That the borders of our memories are as shifting, and that our memories are a part of one great memory, the memory of Nature’; and ‘That this great mind and great memory can be evoked by symbols’ (EE, p. 25). These are the culminating gestures of Yeats’s symbolism; but they also represent his most forceful expression of the values latent in his thinking about the new French painting, which even here continued to haunt his visions of singularity and wholeness. As Yeats remarked, ‘I often think I would put this belief in magic from me if I could’, for in the art of his historical present he found everywhere ‘a certain ugliness, that comes from the slow perishing through the centuries of a quality of mind that made this belief and its evidences common over the world’ (EE, p. 25). The minds of his contemporaries were now too ‘absorbed in naturalism’; they were no longer so susceptible to what Yeats, in a suggestive phrase, called ‘visionary impression’ (EE, p. 27).

We have seen that impressionist painting acquired an increasingly baleful aspect in Yeats’s mind as the prospect of an exhibition in Ireland loomed. Following Lane’s exhibition of Manet and the impressionists at the Hibernian in 1904, it became his principal antagonist, particularly in those writings which explore the connected issues of cultural and aesthetic unity. In the same writings, he repeatedly turns to images of the Renaissance, in which he found a visionary style that served as a corrective to the fragmentary art of the French painters. Thus, in his ‘Preface’ to J. M. Synge’s The Well of the Saints (1905), Yeats praised Synge for abandoning his early ‘impressionistic’ style, which was ‘full of that kind of morbidity that has its root in too much brooding [over] images reflected from mirror to mirror’, and for ‘giv[ing] up Paris’ to forge a style out of the language of the islanders of Aran (EE, p. 216). Yet when Yeats describes Synge’s style, his prose calls to mind not ‘those grey islands where men must reap with knives because of the stones’, but the rather different ambience of the Renaissance:

He made word and phrase dance to a very strange rhythm[.] It is essential, for it perfectly fits the drifting emotion, the dreaminess, the vague yet measureless desire, for which he would create a dramatic form. It blurs definition, clear edges, everything that comes from the will, it turns imagination from all that is of the present, like a gold background in a religious picture, and it strengthens in every emotion whatever comes to it from far off, from brooding memory and dangerous hope.

The blurring of definition, the softening of line, the strange measure of dreams: Yeats’s language evokes the wavering, meditative, organic rhythms he had identified in Titian’s shimmering velatura and grafted onto his theories of symbolist poetry. And the style he describes is held up not only as a corrective to the mirror-like accidence of impressionism, but also as a token and correlative of the shifting boundaries of the universal mind Yeats had envisaged in his essay on ‘Magic’.

Two years later, and with the new French painting about to find a permanent home in Lane’s Municipal Gallery in Dublin, Yeats turned again to the fifteenth-century painters for inspiration, travelling to Italy to join Robert and Lady Gregory for a tour of northern Italy. Since writing his ‘Preface’ to Synge’s play he had immersed himself in Edmund Gardner’s studies of Ariosto and the Dukes of Ferrara; now he visited their actual dwelling places, starting from Venice, the home of Titian. Ariosto appeared to him in a vision as he crossed the Apennine mountain range, silhouetted against a ‘visionary, fantastic, impossible scenery’, ‘glimmer[ing] with lightning’ and ‘windy light’, as though plucked from one of Titian’s glowing canvases (EE, p. 211).59 In Urbino, Ferrara and Florence he harvested images from a prelapsarian Europe, seeking out the visionary faces of Botticelli, dream-bound and ‘hollow of cheek’, and the grave countenances of Titian’s portraits.60 Even here, however, he was always anxiously detecting early signs of ‘an unrest, a dissatisfaction with natural interests, an unstable equilibrium of the whole European mind’ (EE, p. 215), which had begun to express itself in Shakespeare’s imagined journeys to Rome and Verona, and which had reached its most extreme expression in the impressionist painting of Yeats’s own time. Spurred by his visits to the Uffizi Gallery, he returned in his diaries to the theme of unity, transporting himself back to the age of Titian and Ariosto, ‘when all art was struck out of personality’ and ‘there was little separation between holy and common things’: ‘A man of that unbroken day could have all the subtlety of Shelley, and yet use no image unknown among the common people’ (EE, p. 214). Yeats carried the vision back with him to Ireland. That autumn at Coole, he read Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (1528) beneath prints of paintings by Giorgione, Titian and the other Italian masters. Buttressed by these images, he attended the unveiling of Lane’s collection at the new gallery in Harcourt Street in January of 1908. Yeats was at first proud of the collection as a mark of Irish cultural distinction, reporting to John Quinn that the gallery ‘contains a finer selection of modern French paintings of the Impressionist school especially, than even the Luxembourg, certainly than any gallery in England’.61 But in the months that followed he returned repeatedly to Lane’s collection to stare at Manet’s portrait of Eva Gonzalès, who, as he recorded in his diaries, now filled him with ‘doubtings, shrinkings, hatreds’, seeming to represent the total disintegration of the classical canon (‘D’, p. 303). Yeats sought solace in the company of Ricketts, who was then engaged in writing a book-length study of Titian, and whom Yeats counted as one of his ‘chief instructors’ (A, p. 150). They met often in 1909, talking always ‘of the disordered and broken lives of modern men of genius and the so different lives of the Italian painters’ (A, p. 382). When Ricketts’s Titian was published in April of 1910, Yeats read and re-read the book as he attempted to articulate a rejoinder to the new French painting.

Out of the fragments and jottings he had committed to his diaries since the opening of Lane’s gallery emerged Yeats’s essay ‘The Tragic Theatre’ (1910), which, as Schuchard suggests, is really about the ‘irreconcilable conflict of Manet’s art and Titian’s art in Yeats’s mind’, and which shows Yeats retracing through these two figures the conflicts that shaped his visions of wholeness and unity.62 Schuchard uses the essay to understand Yeats’s placement of Titian in A Vision (1925), but it is just as instructive to consider how the essay might elucidate the principles underlying Yeats’s earlier writings. The essay begins with a recollection of a ‘passionless’ rehearsal of Molière’s Les fourberies de Scapin (1671) in Dublin two years earlier, during which Yeats was struck by the realisation ‘that tragedy must always be a drowning and breaking of the dykes that separate man from man, and that it is upon these dykes comedy keeps house’. He cites in evidence a letter by William Congreve concerning ‘the external and superficial expressions of “humour”’, which Congreve defines as a ‘singular and unavoidable way of doing anything peculiar to one man only, by which his speech and actions are distinguished from all other men’ (EE, p. 177).63 The definition bears a remarkable similarity to Yeats’s definitions of ‘abstraction’. This may explain why the rehearsal, which took place shortly after the opening of Lane’s gallery, puts Yeats in mind of Manet. Yeats’s early encounters with Manet were dismal enough, but ‘since then’, he claims, ‘I have discovered an antagonism between all the old art and our new art of comedy’ which helps him to express ‘why I hated at nineteen years [the] new French painting’:

it was not until Sir Hugh Lane brought his Eva Gonzalès to Dublin, and I had said to myself, ‘How perfectly that woman is realised as distinct from all other women that have lived or shall live’, that I understood I was carrying on in my mind that quarrel between a tragedian and a comedian.

Here Manet’s thickly drawn outlines reflect a modern fall into disunity, ‘distinct’ subtly registering twinned notions of division and demarcation, with the implication that the manner in which Gonzalès is realised is a symptom – and, literally, an illustration – of the ‘abstraction’ Yeats wished to escape.

According to his latest set of opposed terms, Manet and the impressionists belonged to an ironic modern world, in which ‘fragments broke into ever smaller fragments’ and ‘we saw one another in a light of bitter comedy’ (A, p. 165). His concluding stress on a manner of seeing is a subtle indication of the forms in which this fragmentation was most apparent to Yeats. In a diary entry of 1909, he describes a corridor at Coole lined with etchings by an English devotee of Manet, Augustus John:

I pass a wall covered with Augustus John’s etchings and drawings. I notice a woman with strongly marked shoulder-blades and a big nose, and a pencil drawing called Epithalamium. In the Epithalamium an ungainly ill-grown boy holds out his arms to a tall woman with thin shoulders and a large stomach. Near them is a vivid etching of a woman with the same large stomach and thin shoulders.

‘Strongly marked’, John’s caricatures of contemporary life are rendered here in an equally robust language of the grotesque, which seems drawn to bodies ‘broken by labour’, and to linger over their uneven, ungainly outlines. And this conspicuous attention to a manner of perception is significant, because it discloses the wider symbolic function of John’s artworks for Yeats, who detects in them (as he does in Manet’s portraits) a celebration of ‘the “fall into division” rather than the “resurrection into unity”’ (A, p. 371).

As they are in his appraisals of Manet and the impressionist painters, strongly inscribed outlines are construed here as legible imprints of modernity’s collapse into self-consciousness and disunity. In response, Yeats turns to ‘an art of the flood, the art of Titian when his Ariosto, and his Bacchus and Ariadne, give new images to the dreams of youth’, investing the overflowing colour of the Venetian painters with the potential for revelation and wholeness (EE, p. 177). Both qualities are implied by the new metaphor of the flood that Yeats brings to his descriptions of Titian’s painting, a metaphor which suggests both the cleansing force of the biblical flood and burst boundaries, and which had been gestating since the threat of an impressionist incursion in Ireland had first impressed itself on Yeats. The idea of the flood is latent, for example, in his conception of symbols as portals through which ‘minds can flow into one another’, and we can observe ancestors of the metaphor in Yeats’s thought as early as 1898, when he contrasted the work of the impressionist painters with the cabbalistic artworks of Althea Gyles, who had produced the ornately symbolic cover designs for The Secret Rose (1897) and The Wind among the Reeds. Against the pictures of ‘men like Mr. Degas, who are still interested in life, and life at its most vivid and vigorous’ – a phrase that calls to mind the ‘athletic’ outlines of Manet’s Olympia – Yeats had described Gyles’s ‘rhythms of colour’ as expressions of ‘a hidden tide that is flowing through many minds’ and which was now pouring forth in ‘a new religious art’ which enabled the self to transcend the ‘egotistic mood’ and ‘merge in the universal mood’.64 Likewise, Yeats’s latest description of ‘modern art’ – which is understood best ‘through a delicate discrimination of the senses which is but entire wakefulness, the daily mood grown cold and crystalline’ – would be a portrait in prose of the deadening glass depicted by ‘The Two Trees’, just as the terms in which Yeats describes tragic art (of ‘reverie’ and ‘dream’) are congruent with the vision realised by the first part of that poem.

What has become clearer, however, is the alignment of reverie and dispersed outline with a dissolution of the partitions between selves: with a breaching of the isolating dams on which Manet’s art kept house, so that ‘the persons upon the stage, let us say, greaten till they are humanity itself’, and ‘we feel our minds expand convulsively or spread out slowly like some moon-brightened image-crowded sea’ (EE, p. 179). In this sense, the art of the flood would herald that unity which is the founding gesture of Yeats’s symbolist project, and the impulse within this apocalyptic revelation of wholeness is one of escape. As he had after his first visits to Paris, Yeats turns again to the glowing colour and iridescent light of Titian, in whose Ariosto and Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1520) he finds ‘rhythm, balance, pattern, images that remind us of vast passions, the vagueness of past times, all the chimeras that haunt the edge of trance’. All were ‘devices to exclude or lessen character, to diminish the power of that daily mood’ and ‘blind its too clear perception’: to wash away or dissipate the clear outlines of things. The picture provokes one of Yeats’s characteristic rhetorical questions, which culminates in an ecstatic vision of lines so diffuse and delicate that the individual figure escapes definition completely:

And when we love, [do] we not also, that the flood may find no stone to convulse, no wall to narrow it, exclude character or the signs of it by choosing that beauty which seems unearthly because the individual woman is lost amid the labyrinth of its lines as though life were trembling into stillness and silence, or at last folding itself away?

Following Titian’s example, then, if we are poets we will adopt (as indeed Yeats already had) ‘a flowing measure that had well befitted music’; and if we are painters, ‘we shall express personal emotion through ideal form’, enlarging and enriching our private sentiments with ‘a style that remembers many masters that it may escape contemporary suggestion’ (EE, pp. 177–9).

It is significant that, in his final reckoning with Manet and the impressionists, Yeats should invoke the idea of ‘escape’. His view of contemporary art would alter as he was introduced to the sculpture of Jacob Epstein, Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, just as he would increasingly be drawn to the muscular outlines of the later Florentine Renaissance.65 But ‘The Tragic Theatre’ marks the culmination of an initial conflict in Yeats’s thought between ancient and modern art, as those two ideas are figured through Titian and Manet. And this conflict plays out across the territory defined by the language of escape: of unveiled truth and disturbed outline, and of the unified whole as opposed to the isolated fragment. In Yeats’s handling, this language describes forms that not only blur any too clear perception of outline – wavering rhythms, for example, or glimmering colour and light – but which are also said to dissolve the cell of the self to reveal a larger unity. Escape might, then, be seen as both an emblem of the unity or totality after which Yeats searched and his guiding metaphor for the style by which it might be realised. In a wider sense, Yeats’s attempts to escape the art of Manet and the impressionists draw attention to the threats that impressionism could appear to pose even decades after its first unveiling, demonstrating the speed with which its perceived affronts to inherited canons of form could aggravate more deeply rooted anxieties about social and psychological fragmentation. Indeed, the relationship between Yeats’s early verse and his dismayed responses to impressionist painting would underline the galvanising effects of repulsion. His conception of symbolism in both verse and painting constitutes one part of the unevenness of the literary reception of impressionist art, but it also indicates the richness of irregularity itself.