‘And those who were seen dancing were thought

to be insane by those who could not hear the music.’

–Friedrich Nietzsche

Discussion piece

I open this discussion with a picture (see Figure 1) I took last year in Nazaré, Portugal, known as the surfing capital of the world infamous for its thirty-meter-high waves. This is the place where surf legends are born while others tragically succumb to the wrestling waters of this apparent geological wonder. Upon reaching the ‘terrestrial seascape’ (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025), one is encountered by a 6.3-meter-high anthropomorphic sculpture entitled Veado (meaning ‘deer’ in Portuguese) made out of marble and steel. While Veado represents a twelfth-century legend of an animal-saint encounter within the local topographic landscape, its mere presence and sturdy structure epitomizes the contemporary and multidisciplinary terrain of the Anthropocene and the semiotic resources that are mobilized in the production of nature and the more-than-human environment given its high regime of visibility to just about any passer-by. Such a structure, regardless of one’s tastes, invites us to critically consider Anthropocenic landscapesFootnote 1 and question how they are ideologically represented, materially produced, geographically emplaced, symbolically situated, semiotically indexed, digitally mediated, and globally circulated within both physical and digital spaces that are driven by the political economy addressing several themes in this special issue.

Figure 1. Veado sculpture in Praia do Norte, Nazaré, Portugal.

The world is in flux and no doubt it always has been, but our access to both information and misinformation has experienced a major shift in the ‘age of digital transnational interaction and AI interventions’ (Erdocia, Migge, & Schneider Reference Erdocia, Migge and Schneider2024:3; see also Harari Reference Harari2024). What we consume literally and ideologically will affect how we feel and even dictate the discourses we take part in or rebuff. Whether we are in the age of the Anthropocene (Ellis, Magliocca, Stevens, & Fuller Reference Ellis, Magliocca, Stevens and Fuller2018), Capitalocene (Moore Reference Moore2017; Nae Reference Nae2023), Westernocene (San Román & Molinero-Gerbeau Reference San Román and Molinero-Gerbeau2023) or any other, is perhaps not our call as sociolinguists, but continuing to expand our scope of study is not only worth considering, but also inevitable. However we label such processes and periods, they are no doubt ‘academic constructs’ (Snajdr & Trinch Reference Snajdr and Trinch2025), in an era where societal divisions seem heightened, and censorship is on the rise (Roberts Reference Roberts2020; Desmet Reference Desmet2022). For these reasons, we must remain open to debates and welcome perspectives that differ from our own. For what it’s worth, I hope readers of this piece will find it fruitful.

Nearly twenty years ago within the context of language and globalization Coupland (Reference Coupland2003) asserted that sociolinguistics ‘is already late getting to the party’ while Eckert (Reference Eckert2003), maintained that ‘research is a zoo’Footnote 2 equipped with ‘elephants in the room’. Eckert was referring to large presences that scholars collectively ignore in order to carry out their research. Could similar sentiments be said about the study of sociolinguistics and the Anthropocene in 2025? For some time now, several language scholars have questioned the assumptions about the literal nature of language and how it has been conceptualized (Makoni & Pennycook Reference Makoni, Pennycook, Makoni and Pennycook2006). More recently and perhaps somewhat paradoxically, language scholars have de-centered language as their main unit of analysis turning their empirical and analytical gazes to pressing issues concerned with post-humanist theorization and ontological biases that privilege human exceptionalism (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018; Lamb & Higgins Reference Lamb, Higgins, Fina and Georgakopoulou2020; Wee Reference Wee2021; Schneider & Heyd Reference Schneider and Heyd2024). Some of these projects center on human-animal communication (Kulick Reference Kulick2017; Cornips Reference Cornips2022; Lamb Reference Lamb2024; Lind Reference Lind2024) while questions of embodiment (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Coupland2016), materiality and place (Scollon & Scollon Reference Scollon2003) aren’t really all that new. Most recently, and unsurprisingly, digitized technologies and AI (Purschke Reference Purschke2017; Schneider Reference Schneider2022; Kelly-Holmes Reference Kelly-Holmes2024; Voss Reference Voss2024; Maly Reference Maly2025; Erdocia, Schneider, & Migge Reference Erdocia, Schneider and Migge2025) have taken center stage.

In this collection of articles, we hone in on complex, assemblaic relations of human, non-human, more-than-human, animal, spatial, digital, environmental, and political economic questions trying to tease out the relevant role that language and other modes of semiosis have in the powerful production of planetary matters.

In preparing for this discussion, I read Animals by Don LePan (Reference LePan2009). The novel takes us on a disturbing but equally fascinating journey exploring the blurred boundaries between humans and non-humans, raising ethical and moral questions about the value of life, which are always intertwined with sociocultural issues and trends as well as political economic agendas and questions of power. LePan’s (Reference LePan2009) work made me question my own as well as other’s banal choices and its effects on the world, not only in terms of daily food consumption (which I’ll come back to later) but of our everyday social practices as privileged academics (i.e. engaged in highly mobile, digital, and often remote work). Let’s be honest, how many of us would be willing to forgo an invited talk in a foreign country due to carbon emissions? Can we really afford to miss the chance to top up our CVs in an effort to better manage ecosystems given the pressures of our performance-based profession? In 2003, the elephant in the room Eckert was referring to was the ideological construct of authenticity ‘that is central to the practice of both speakers and analysts of language’ (2003:392). Within the context of the Anthropocene, one elephant may be the ideological construct of the Anthropocene while other elephants in the room may be all of us unless you are of the opinion that natural causes are to blame for planetary crisis rather than human intervention (see Figure 2). Such sentiments inevitably reconstruct the problematic dichotomy of ‘nature’ versus ‘culture’ (Smith Reference Smith2025). For Veland & Lynch (Reference Veland and Amanda2016:1) ‘increasingly fortified stances on the ‘right’ definition of the Anthropocene epoch follow traditions of linear and authoritarian historical accounts and prevent discovering epistemes of human-environment interactions that are open for coexistence’.

Figure 2. A picture of the Mittellegi hut originally built in 1924 equipped for climbers and mountaineers, which sits at 3,355 meters (11,007 feet) above sea level on the Mittellegigrat ridge, a salient feature of the Eiger mountain in the Junfrau Region in Switzerland.

Regardless of one’s personal beliefs, as academics, our job is to remain open, critical, and reflexive about sociolinguistic practices (Gonçalves & Schluter Reference Gonçalves and Schluter2024; Gonçalves & Lanza Reference Gonçalves, Lanza, Røyneland and Wei2024), and discourses knowing that we are not outside of them, but complicit in their production and dissemination resonating with Cameron’s (Reference Cameron2020) well-known assertion that no researcher is outside of research. In laying the groundwork for new theoretical and methodological frameworks through which sociolinguistics may address planetary crisis, three distinct directions for the study of space and semiosis are proposed, all of which are taken up in the articles in this issue. They include: (i) entangled and expanded space, (ii) attunement as method and praxis, and (iii) political economy as planetary actor.

Indeed, all of these directions are relevant for the analysis of Anthropocenic landscapes as we move forward in our transdisciplinary endeavors or epistemic assemblages (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018). And while I do not necessarily think these directions are new within applied or sociolinguistics, they certainly are for the field of linguistic landscape studies. In this issue we encounter ‘epistemic rupture’ (Bachelard Reference Bachelard1938/1986) within numerous sensescapes (Medway Reference Medway, Kavaratzis, Warnaby and Ashworth2015) on land, sea, and in the sky that are being explored in terms of signage (or lack thereof) and the complex networked relations in various spaces that demand our attention with regard to what I call planetary repertoires—semiotic de-coding and meaning making as it pertains to the Anthropocene. ‘I may be wrong’ (Lindeblad, Natthiko, Bankeler, Modiiri, & Bromme Reference Lindeblad, Bankeler, Modiiri and Bromme2023), but from my reading, it appears that interpretive codes including perceptual codes and ideological codes among multispecies gain currency and are valued above certain modes and linguistic codes among humans only. This is perhaps somewhat of a paradox given that all articles (to the best of my knowledge) are written by human researchers. This also raises questions about ‘ethical loyalities’ and their conflicts (Fair, Scheer, Keil, Kiik, & Rust Reference Fair, Scheer, Keil, Kiik and Rust2023). But since ‘money talks’, I’ll begin by addressing the political economy as planetary actor.

Economy as planetary actor

The political economy of language is one which has continued to be relevant to linguistic anthropologists and critical sociolinguists since the seminal work of Irvine (Reference Irvine1989). And while the political economy of signs is not new (Baudrillard Reference Baudrillard1976/1993), it gained momentum within the field of linguistic landscape (LL) with Jaworski & Thurlow’s introduction of Semiotic landscape (2010:10) forcing us to shift our analytical gaze beyond language only to include ‘any public space with visible inscription made through deliberate human intervention and meaning making’. While public space is rarely public (Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2019) and never neutral (Harvey Reference Harvey2005; Gonçalves & Milani Reference Gonçalves and Tommaso2022), the emphasis here was still on human agency. Underlining semiotic practices was an important reminder that language (regardless of one’s philosophical orientation) is just one part of a larger system of communication. In 2016, Gal reminds us that semiotic practices are valued differently depending on the semiotic ideologies we ascribe to them.

As we know, a plethora of economies exist and therefore also different forms of capital, some of which include financial, human, symbolic, network, economic, cultural, spatial, residential, intellectual, attention, and natural. And where there is capital, there are also currencies (Agha Reference Agha2017), which vary in value and societal significance depending on the master narratives of our time, one of which currently appears to be polycrisis with the planet as protagonist (Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves, Bianco and Lundberg2026). Footnote 3

Nature and wildlife in the forms of untouched baren landscapes (Smith Reference Smith2025; Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025), exotic creatures (Lamb Reference Lamb2025; Sharma Reference Sharma2025) or organic food (Kosatica Reference Kosatica2025) gain currency and become iconic and indexical of both spatial and visual semiotic systems and examples of nonlinguistic enregisterment (Telep Reference Telep2021; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2024), that are highly valued within visual, attention, tourist, and extractive economies (Poole Reference Poole1997; Goldhaber Reference Goldhaber2006; Heller, Jaworski, & Thurlow Reference Heller, Jaworski and Thurlow2014; Sultana Reference Sultana2023). Within the field of sociolinguistics, Kelly-Holmes (Reference Kelly-Holmes2005) has long claimed that the role of visuality in advertising is becoming increasingly central to contemporary consumer culture. This resonates with Ledin & Machin’s (Reference Ledin and Machin2018:1) more recent assertion that society is becoming ‘more visual’ and dominated by images that are in line with predicaments about our ocular-centric society that is epistemologically biased by vision.Footnote 4 While different eyes may have different sociocultural perspectives (Andreotti & de Souza Reference Andreotti and Lynn Mario2008; Vold Lexander, Gonçalves, & De Korne Reference Vold Lexander, Gonçalves and De Korne2020), not all eyes see, read, or are visually literate, thus not all distinctions are visible.

The powerful pictures and plans discussed by Snajdr & Trinch of the Atlantic Yards project underscored the sense of vision. A large professional sports arena and high-rise residential towers does not visually sit well in the center of leafy low-rise Brooklyn due to its emplacement, high regime of visibility, and where social class divisions become symbolically and literally materialized. For Baudrillard (Reference Baudrillard1981/2019) the transcendence of economic privilege into a semiotic privilege ‘represents the ultimate stage of domination’. Spectacles of semiotic privilege emerge in many of the articles in this issue. We see this in Kosatica’s study where pristine images of cows grazing in grasslands become enregistered emblems for visual and eventually human bodily consumption where the powerful rhetorics of ‘natural’ and ‘nutrious’ seem to celebrate both planet and cows via greenwashing and financial gain. In Sharma’s study, we see how elephant polo is driven by capitalist logics where wildlife becomes apropriated for elite leisure (and touristic) consumption by reinforcing colonial legacies through the commodification of animal labor framed by sports and conservation. Such economic erasure is also found in Moriarty’s work of the Wild Atlantic Way (WAW) designed to attract tourists to more remote, rural, and ‘authentic’ parts of the country, where spatio-temporal relations of connectedness are underscored rather than economically driven interests. While this could fit in well with the ethos of the Anthropocene that fundamentally undermines orthodox economic paradigms, it also means rejecting economic and political success by long-standing metrics such as GDP (Thomas, Williams, & Zalasiewicz Reference Thomas, Williams and Zalasiewicz2020).

Within such contexts, the political economy as planetary actor mushrooms into hegemonic discourses of sustainability (McManus Reference McManus2007), which become mobilized in different industries and markets on a global scale. The motto ‘sustainability sells’ (with a nod to the mighty rhetorical functions of both anthropomorphism and personification) emerges within complex, contradictory, and clashing economies of capitalism, ecology, digitization, affect, and care within several articles in this issue.

How sustainability becomes a commodified linguistic resource and semiotically framed varies (Archer & Björkvall Reference Archer, Björkvall, Sherris and Adami2019; Kosatica & Smith Reference Smith2025) but it is no doubt prevailing, highly valued, and according to German architect Sascha Arnold, sustainability is also ‘sexy’ (Gruner & Jahr 2025:25). Everything from transportation (Figure 3), clothing (Figure 4), homes (Figure 5), workplaces (Figure 6), bags (Figure 7), banking (Figure 8), and paper (Figure 9) currently multimodally and thus semiotically bombard us with implicit messages of planetary crisis while simultaneously serving as signs of ecological, industrial, professional, societal, and individual responsibility, where minute changes have the potential to benefit people and the planet, the human and the more-than-human. But where does this leave room for structural implementations? While the post-colonial era has seen the rise of ‘human development’ as a global sociopolitical goal (Sen Reference Sen1999), we must not forget that the dominant form of development is still first and foremost, capitalist (Srinivasan & Kasturirangan Reference Srinivasan and Kasturirangan2016) ‘infused with the priorities of neoliberalism’ (Machin & Liu Reference Machin and Lui2023:4).

Figure 3. Sustainability billboard by the Jungfraubahn, a local private railway company in the Bernese Oberland, Switzerland, which transports over one million guests a year to the ‘Top of Europe’.

Figure 4. A bilingual Sanskrit-English sign, NISHTA Sustainable Livin’ clothing store in Interlaken, Switzerland.

Figure 5. The August 2025 special issue of the magazine Schöner Wohnen (Europe’s largest living magazine) entitled Natürlich Nachhaltig, wir lieben Holz ‘Naturally sustainable, we love wood’.

Figure 6. ‘Be productive, be sustainable’ at a plant-based workplace in Austria.

Figure 7. A recycled bag that used to be a plastic bottle.

Figure 8. ‘Sustainable investment’ bank advertisement at Zurich airport.

Figure 9. Gras Papier Nachhaltig ‘Sustainable grass paper’.

We see ‘sustainable development’ unravel in Snajdr & Trinch’s (Reference Snajdr and Trinch2025) article where concerns over redevelopment, whether utopian or dystopian, are grounded in a neoliberal framework that favors individual achievement, land use, and economic capital. Such human-centric behavior has led the authors to coin the term mytopic to index such individualistic perspectives on the future of place, private property, and private profit. Moriarty’s (Reference Moriarty2025) study alludes to a form of blue sustainable tourism, where the seascape becomes a commodity to be leveraged in the pursuit of economic gains at local, regional, and national levels within an Irish tourism context. Here, we have the example of the WAW being branded as a quiet, peaceful, and remote place plush with the aim of luring urbanites to explore and exploit natural landscapes (on foot and by car) for the sake of both symbolic and network capital while simultaneously gaining economic profit. An example of ‘structural unsustainability’, such ‘commodified spectacles’ become an example of Disneyfication and a modern-day Irish bucket list with a passport to prove it resonating with what Urry (Reference Urry2002:129) calls a ‘vicious hermeneutic circle’.

Similarly, Smith (Reference Smith2025) introduces us to one Anthropocenic landscape in a small village in Oman that is remote and abandoned due to reasons of modernization, industrialization, and domestic migration based on the government’s provisions of services (i.e. schools, hospitals, etc.) in larger towns. While attending to the ‘semiotics of nonexistence’ (Karlander Reference Karlander2019) may be relevant for our field, this could come at a considerable cultural, social, and ecological cost resulting in what’s been referred to as ‘wilderness gentrification’, or ‘greentrification’ (Smith, Philipps, & Kinton Reference Smith, Philipps, Kinton, Lees and Phillips2018).Footnote 5 Indeed, tourist consumption resonates with broader economies of value and attention and the discourses of nature tourism and conservation (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025; Sharma Reference Sharma2025; Lamb Reference Lamb2025; Smith Reference Smith2025), simultaneously index processes of branding. For Goldman & Papson (Reference Goldman and Papson2006:328), ‘it sometimes seems as if there is hardly any market arena, not even a niche, that has been left uncolonized by branding processes [where] branding represents one institutionalized method of practically materializing the political economy of signs’.

We see this in Kosatica’s (Reference Kosatica2025) study of mediatized ‘beefy landscapes’ that index tensions between lifestyle and sustainability in the semiotic and discursive construction of social class, green political orientations, and individual and collective identities (Cooper, Green, Burningham, Evans, & Jackson Reference Cooper, Green, Burningham, Evans and Jackson2012). Through her analysis, Kosatica shows how so-called meaty routines are deeply entrenched in environmental escapism pushing lifestyle trends to ‘eat right’ contributing to the reproduction of social hierarchies and distinctions of taste (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1984). Kosatica’s study also reveals the literal and symbolic dirty work that goes into the production and maintence of organic farming capturing the politics of agricultural labour where invisible migrant workers are exploited and faceless.

While organic beef might taste better, it is not an option for the average citizen given its higher costs. Organic anything is unlikely to become standard unless we begin to critically think about replacing mainstream economics (where infinite growth is hegemonic) with ecological economics, where ‘green growth’ reigns (see also Sharma Reference Sharma2025). Yet how can the political economic and planetary clashes be reconciled given contemporary ‘Trumponomics’ (Moore & Laffer Reference Moore and Laffer2018; Scanlon Reference Scanlon2025), which has ramifications for the global economy? History has shown us that most superpowers will go to extraordinary measures to maintain their geopolitical and economic power on the world stage regardless of the costs (human, animal, environmental) (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2017; Chomsky & Robinson Reference Chomsky and Nathan2024). And history has versions, none of which are universal (de Souza & Duboc Reference De Souza and Duboc2021).

Indeed, the discourses and images surrounding beefy landscapes counteract the recent message on a parasitic sign (Kallen Reference Kallen, Jaworski and Thurlow2010) and ‘transcultural text’ (Purschke Reference Purschke2017, Reference Purschke, Amos, Blackwood and Tufi2024; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves, Lee and Rüdiger2025) found outside my workplace (Figure 10).

Figure 10. ‘STOP EATING ANIMALS’ at the corner entrance of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Bern, Switzerland, 2024.Footnote 6

‘I may be wrong’ but bottom-up ecological (and vegan) landscapes in the form of stickers are on the horizon (Reershemius Reference Reershemius2019; Gonçalves, Erba, Semadeni, & Demircan Reference Gonçalves, Erba, Semadeni, Demircan, Gorter and Cenoz2024; Gonçalves, Erba, & Semadeni Reference Gonçalves, Erba and Semadeni2025; Reershemius & Ziegler Reference Reershemius and Ziegler2025). In this example, sign posters seem well aware that meat production is a leading driver of environmental change on a global scale. This anthropocenic sign echoes Sharma’s call for considering an interspecies ethics where hierarchies between humans and animals dissolve, points that were also raised in the articles by Lamb (Reference Lamb2025) and Moriarty (Reference Moriarty2025).

Attunement as method and praxis

In this collection of articles, we learn about researchers’ firsthand experiences from their deep immersion and commitment to their particular units of analyses through ‘embodied ethnography’ (Jeffrey, Barbour, & Thorpe Reference Jeffrey, Barbour and Thorpe2021; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves, Lee and Rüdiger2025), multi-species ethnography, and cyberethnography in their very own performances of place (Goffman Reference Goffman1959; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2020a). Whether it be swimming with jellyfish off the Irish coast (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025), engaging in ‘wild camping’ without birds in Oman (Smith Reference Smith2025) attending elephant polo championships and elephant beauty pageants in Nepal (Sharma Reference Sharma2025) or doing ‘digital intimacy’ with monk seals in Hawaii (Lamb Reference Lamb2025), a methodological shift is currently underway, where all of our senses are required (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025). This aligns with Pennycook’s earlier (2022:572) predictions of engaging in multisensory assemblage since ‘we do not engage with the world one sense at a time [and where] synaesthesic sensibilities may be the norm (Howes & Classen Reference Howes and Classen2014)’.

Linguistic landscape studies have already extended its scope well beyond multimodal visual analysis of material signage to include a wider range of semiotic forms such as soundscapes, smellscapes, and skinscapes (see articles in Shohamy & Ben-Rafael Reference Shohamy and Ben-Rafael2015). Such sensescapes could align with Kusters’ (Reference Kusters2017) notion of sensory ecology and the importance of touch as sites of engagement (Sharma Reference Sharma2025).Footnote 7 In any interactional encounter, orchestration matters (Hua, Otsuji, & Pennycook Reference Hua, Otsuji and Pennycook2017; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2020b) and attunement is key (Lamb Reference Lamb2025). Within the context of the Anthropocene, relational attunement is called for (Lamb Reference Lamb2025; Smith Reference Smith2025) that encompasses ‘more-than-human voices, temporalities, and material processes’ (Brigstocke & Noorani Reference Brigstocke and Noorani2016:2). This is not an easy task given that temporal and spatial scales where the scales of geological significance and the scales of social significance are not the same (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Williams and Zalasiewicz2020). The planet appears to be multidialectal equipped with its own repertoires based on Indigenous philosophies and knowledges (Selin Reference Selin2003; Dei, Karanja, & Erger Reference Dei, Karanja, Erger, Dei, Karanja and Erger2022). The question becomes: do we place value on actually listening (Staddon, Byg, Chapman, Fish, Hague, & Horgan Reference Staddon, Byg, Chapman, Fish, Hague and Horgan2023), learning and trying to decipher its many codes and cultural meanings (Carbaugh Reference Carbaugh, Cantrill and Oravec1996)? For attunement to even happen we must be open and physically present in order to actually make sense of what we sense in our local surroundings (see also Deumert & Storch Reference Deumert, Storch, Deumert, Storch and Shepherd2020). This demands our undivided attention on how planetary repertoires and semiotic ideologies are produced and interpreted and where silence (Smith Reference Smith2025) and extinction (Lamb Reference Lamb2025) become emblematic signifiers worthy of semiotic investigation or in the case of blight (Snajdr & Trinch Reference Snajdr and Trinch2025) convenient discursive forms that rhetorically and economically justify geographic displacement and human erasure. Complete focus necessitates absorption verging on monomaniacal tendencies, including that of the self (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. A photo taken by the author in Vienna airport in July 2025.

On the one hand, attuning to local surroundings could require some digital detoxing (Radtke, Apel, Schenkel, Keller, & von Lindern Reference Radtke, Apel, Schenkel and Keller2022), a daring move in our current post-digital societies (Tagg & Lyons Reference Tagg and Lyons2022), where the boundaries of off and online spaces are invariably blurred. We see this in Smith’s analysis of the Grand Canyon of Arabia, where all space becomes ripe for sociolinguistic and semiotic study. On the other hand, contemporary society is ‘consumed by digital invasion and addictive trivial diversion’ (Sharma Reference Sharma2024:34), where more intrusive options are necessary to become digitally intimate (Lamb Reference Lamb2025) through wildlife surveillance and tracking via crittercams. Lamb (Reference Lamb2025) shows the inherent paradoxes of how digital infrastructures of surveillance are pulling humans and nonhumans into competing multispecies futures, with some oriented toward experimental possibilities for flourishing cohabitation, while others are geared toward intensified control and value extraction. For Lamb, digital intimacy foregrounds and undoes traditional hierarchies of care in human-wildlife relations in how it troubles the relation between caring and knowing in ways not previously possible. This differs somewhat to Sharma (Reference Sharma2025) who argues for an ethical stance and approach, which centers on multispecies justice, where a critical examination of commodified encounters exemplifies and reproduces hierarchies of control, care, and value that are deemed ‘superficial’ and ‘socially and ecologically harmful’. In a similar vein, Moriarty (Reference Moriarty2025) maintains that a failure to think with the non-human in seascapes adds to its vulnerability. In other words, everything matters, and everything is agentic including matter itself (Barad Reference Barad2007) aligning with post-human theorization. The challenge remains in finding the right balance between what matters (literally, ideologically, and ethically) and the significant (or insignificant role) that language and other forms of semiosis play in our analyses of anthropocenic landscapes and planetary matters.

Entangled and expanded space

Theory drives our analyses in entangled and expanded spaces. In this collection of papers, a unifying theoretical concept emerged, namely, that of assemblage (Deleuze & Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari1988). Assemblage theory has a long intellectual trajectory in the social sciences equipped with a plethora of growing modifiers (linguistic, semiotic, sociomaterial, text, temporary, rhizomatic, surveillant, critical, sociotechnical, multisensory, epistemic, privatized). For language scholars, assemblage is known in both applied linguistics (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018, Reference Pennycook2024) and sociolinguistics (Pietikäinen Reference Pietikäinen2021, Reference Pietikäinen2024) as ‘an alternative way to look at the world that starts with multiplicity and focuses on relations, connections and processes’ (Pietikäinen Reference Pietikäinen2021:235), rejecting binaries and dualisms. Drawing on concepts of entanglements or assemblage ‘helps to understand the multiple ways in which animals (and other non-human entities) are enmeshed in linguistic, social, cultural, material, and political relations’ (Cornips, Deumert, & Pennycook Reference Pennycook2024:170). This is complicated (much like nexus analysis, network theory, and complexity theory) and most likely messy, but necessary, possible, and even magnetic (Lamb Reference Lamb2025) as the articles in this issue have shown, especially as we account for different types of communicative fields and spaces encompassing the physical, ideological, digital, urban, and remote while simultaneously reckoning with diverse kinds of multispecies and Indigenous encounters (and lack thereof) on land, sea, and in the sky.

From the work of Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith1991), space is always realized in the ways we represent it—for example, how we write about it, talk about it, photograph it, advertise it, and design it. The ways in which places and spaces were represented differed in the articles, but all of them approached different sites of engagement located at the ‘phygital’ (Lyons Reference Lyons2019) interface of the ‘offline-online nexus’ (Androutsopolous Reference Androutsopoulos, Blackwood, Tufi and Amos2024; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2024; Gonçalves & Lanza Reference Gonçalves, Lanza, Blackwood, Tufi and Amos2024). This is most likely to become the ‘new’ methodological norm in LL studies if it isn’t already raising questions of (trans)disciplinary boundaries that appear to be crumbling, which broaches another question: are these crumbs organically feeding into entangled epistemic assemblages or are they being forcefully fed?

Online platforms and social media sites are spaces of ‘public pedagogy’ (Giroux Reference Giroux2004) where we go to read, see, learn, post, and perform engaging in discursive, intertextual, and semiotic practices that get ‘recycled’ through processes of remediation, re-semiotization, and in some cases, also resignification, while simultaneously serving as communal spaces for protest, resistance, and dialogic exchange (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025; Snajdr & Trinch Reference Snajdr and Trinch2025; Lamb Reference Lamb2025; Sharma Reference Sharma2025; Smith Reference Smith2025; & Kosatica Reference Kosatica2025). Online spaces are also transactional and are where digital and attention economies meet (Blackwood Reference Blackwood2018; Smith Reference Smith2019), and a virtual space where attention transforms into a scarce type of capital given its abstract quality and measurability (Terranova Reference Terranova2012:2). For Kelly-Holmes (Reference Kelly-Holmes2022), our growing ‘technologized reality demands that we build algorithmic reflexivity into both our teaching and research’. And while semiosis comes in many forms, we cannot underestimate written language since according to Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Williams and Zalasiewicz2020) it ‘allows us to transfer complex knowledge across time and space to coordinate conquest, administer vast territories and exploit resources and people’. Recent scholarship extends the idea of writing to ‘all forms of symbolic signification, or sign-making’ (Jaworski & Li Wei Reference Jaworski and Wei2021:4). Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the field of linguistic and semiotic landscapes.

As scholars of language, we are well versed in the effective functions of storytelling (Labov Reference Labov1972; De Fina & Georgakopoulou Reference De Fina and Georgakopoulou2012) and Foucault’s (Reference Foucault and Smith1972) notion of discursive regimes and the power dynamics involved in the creation and legitimatization of knowledge and ‘truth’ within a specific place and historical time. Truth is therefore relative, fiction is fabricated, and not all stories get told (Snajdr &Trinch 2025; Kosatica Reference Kosatica2025). For the forces in our field breaking new ground, continued ‘academic migration’ (Thorpe Reference Thorpe2011; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2020a) is a must as is the inclusion of epistemic perspectives from different cultures of the world regardless of how we geographically label them (Southern, Northern, Eastern, Western; and their non’s) since these too are socially constructed cartographic designations and ‘abyssal lines’ (Santos Reference Santos2007) that get reproduced in our discussions and materialized in our publications. As scholars researching anthropocenic landscapes, we need to carefully and consciously situate ourselves as knowledge-producing subjects, read widely, remain critical and reflexive of our own patterns of consumption in whatever algorithms and configurations they may be. These include ideological consumption via media and their biases, bodily consumption of all kinds of matter (organic and/or junk), and so on, knowing that whatever we feed on influences our opinions, semiotic practices, and mobile performances (even those framed in the name of conservation research). Such practices affect planetary matters in our contemporary post-everything world while we navigate the future terrain of anthropocenic landscapes and the conflicting ideological values we attach to them including our ethical loyalities (for those who still have them).

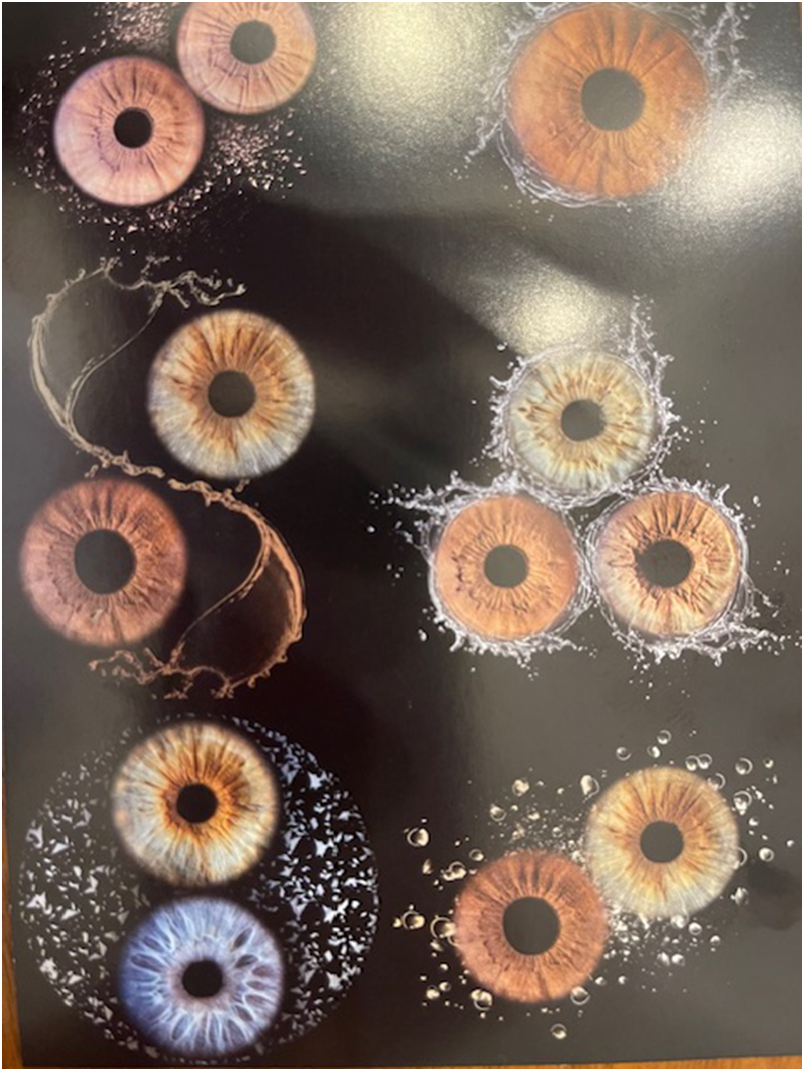

For years, many of us with access to technology have had to confirm being human by reading distorted texts and typing them into small boxes as proof that we aren’t robots. Today, we are living in an age where ChatGPT is regarded as an ‘intellectual partner’ (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2025) and money can be made with air (Pietikäinen Reference Pietikäinen2024). Our sense of sight allows us to detect, unquestionably devour, and query semiotic regimes locally as well as in different sociocultural, political, and environmental contexts. Moreover, our irises are multifunctional in that they can now serve as a piece of artwork (Figure 12) and simultaneously operate as a biometric identification method used for reasons of access and (border) control.

Figure 12. A postcard of Iris Art.

Currently, colonialism and coloniality (as well as their counterparts) come in many forms (Makoni Reference Makoni2019) including appropriation (Rambukwella & Zavala Reference Rambukwella and Zavala2025) and governmentality manifests itself in colors. Our society is filled with people who prefer the comfort of belonging to a flock or a herd (so-called sheeple) that operate in an echo chamber rather than thinking for themselves. We’re social beings and yearn for membership (Milroy Reference Milroy1987) so this isn’t that surprising. Nevertheless, I encourage you to take an ontological, ethical, epistemic, and semiotic deep dive into multisensory discovery and address the elephants in the room and the black sheep that often get sidelined.

For scholars of language, human language (in whatever form) has always mattered, but it’s never the only or most important semiotic code that matters. Context matters and this too is nothing new. For scholars in the field of linguistic landscapes, we’re experiencing ‘epistemic rupture’ (Bachelard Reference Bachelard1938/1986) in real time. Therefore, it’s time to start thinking outside the box (of human language), which is challenging when we’ve been in the box for so long.Footnote 8 The sticker in Figure 13 with its affirmation to nature sums it up quite nicely.

Figure 13. Think outside, no box required sticker.Footnote 9

For linguistic landscape scholars it might be time to consider leaving city streets to explore different and perhaps less traveled paths (Banda, Jimaima, & Mokwena Reference Banda, Jimaima, Mokwena, Sherris and Adami2019) regardless of who may follow. It’s time to acquire planetary repertoires by starting to fine-tune our senses that underscore interpretive codes among multispecies located in different entangled spaces. As we know, signs come in many forms and so do semiotic codes, which we need to learn, de-code, and make sense of in the world in which we live in order to understand axiological functions and their connotative and sociocultural values. On the one hand, it appears that natural landscapes have the power to change human language (Magnason Reference Magnason2025). On the other hand, we are also witnessing how semiotic codes in the form of actual human language are losing their value, but more work is required.Footnote 10 Drawing on theories of post-humanism and assemblage-thinking where everything matters, and complex, networked connectivity is crucial, may be a good starting point while not losing sight of the many ‘elephants in the room’ including replicability. Whether it be in the form of seascapes, beefscapes, magnetic landscapes, eco-semiotic landscapes, mytopic landscapes, and certainly beyond, ‘I may be wrong’, but the articles in this special issue have shown that ‘research is a zoo’ and the epistemic after party has already begun.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to express my thanks to Federico Erba and Tabea Geissmann for their assistance with references and article formatting. My thanks to Sean Smith for the invitation to contribute to this special issue in the form of a discussion piece. Thank you to all of the contributors and their work, which has allowed me to read extensively and learn more about anthropocenic landscapes. I’d also like to thank Sinfree Makoni and various scholars from the African Studies Global Virtual Forum Group for an enriching and very helpful discussion in August 2025. And finally, my sincere gratitude to Britta Schneider, Robert Blackwood, and Sean Smith for their insight and useful feedback on an earlier draft of this article. All shortcomings are my own.