Introduction

Over the past two decades, the architecture of global influence has transformed, challenging conventional notions of state power. Contemporary statecraft increasingly relies on reputation and persuasion alongside military and economic might to steer the direction of world politics (Brooks and Wohlforth Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2016; Dueck Reference Dueck2008). In this context, reliability and moral authority have become key currencies of power. As Nye’s concept of soft power (1990) suggests, influence today depends on attraction over coercion, with legitimacy and credibility as its essential foundations.

China’s strategic evolution connotes a clear awareness of these shifting realities. Recognizing that its rise on the global stage would provoke anxiety if perceived as coercive or revisionist, Beijing has sought to develop and project an alternative model of influence (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Feng, He and Hu2021; Goldstein Reference Goldstein2020; Smith Reference Smith2021). China has deliberately crafted a distinct soft power model, grounded in its civilisational legacy, independent of replicating Western approaches. Yu Keping (Q. Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2015), a well-known Chinese theorist on Chinese-style democracy and good governance, conceives soft power as rooted in education, governance quality, cultural sophistication, and public morality, dimensions reflecting the Communist Party of China (CCP)’s broader developmental agenda. Confucian ideals, reframed for modern governance, inform China’s soft power strategy by linking ethical cultivation with administrative competence. This two-pronged approach—grounded in political hierarchy and moral responsibility—evinces how China’s soft power operates along distinct normative axes.

China institutionalized soft power as a foreign policy priority in the early 2000s. The 16th National Congress of the CCP in 2002 officially declared culture a strategic asset, heralding a new phase in its international relations strategy. Subsequent policy initiatives, most prominently through the 2006 National Planning Guidelines for Cultural Development, advanced the “going out” strategy, encouraging the global dissemination of Chinese language, arts, philosophy, and values (Chu Reference Chu, Chen and Zhong2005; Glaser and Murphy Reference Glaser, Murphy and McGiffert2009; Zhang Reference Zhang2010).

The institutional commitment gained new ideological urgency with the leadership of Xi Jinping, whose emphasis on Confucianism serves dual purposes, legitimizing Communist Party rule domestically and projecting an alternative model of global influence internationally (Minzner Reference Minzner2018; Pang Reference Pang2019; Zhao Reference Zhao2018). Domestically, Xi has cast Confucian thought in the role of an ideological anchor to address the social dislocations of modernisation and to construct a moral and cultural framework that links the Party’s legitimacy to China’s civilisational heritage. In his 2014 address commemorating Confucius’ 2565th birthday, Xi argued that Confucianism contributed to “the cultivation of the Chinese civilisation and its uninterrupted continuation” and “the formation and consolidation of China as a big harmonious family.” By emphasizing “to understand present-day China, one must delve into the cultural bloodline of China,” Xi portrayed the Communist Party as the legitimate heir to China’s cultural tradition (Xi Reference Xi2014).

Internationally, the same framework evolves into a vehicle for articulating an alternative to the liberal democratic order (K. Kim Reference Kim, Min, Hironao and Wah2017; Lam Reference Lam2025). Xi (Reference Xi2014) framed the Confucian principles of “coordinate and seek harmony with all nations” and “within the four seas, all men are brothers” as universal solutions to contemporary global problems. This rhetorical strategy has enabled China to recast its foreign policy into a return to a benevolent and civilized order, notwithstanding a disruptive power shift. While Beijing promotes a unified message, the reception of its Confucian-infused soft power efforts is far from uniform. The gap between China’s Confucian appeals and its assertive actions—particularly in disputed maritime areas—undermines these claims among Southeast Asian publics who interpret ethical leadership through the relational and reciprocal expectations central to Confucian ethics themselves (Minzner Reference Minzner2018).

The promotion of Confucianism operates primarily through institutions such as the Confucius Institutes. Established in 2004, these centres have expanded rapidly, reaching 496 worldwide by 2023 (Chinese International Education Foundation 2024). They function as key nodes in China’s soft power architecture, especially across Southeast Asia, where enduring Confucian legacies intersect with local traditions of elite governance and political hierarchy (Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen2015). The reception of these institutes, however, hinges on public perceptions of China’s regional conduct and moral consistency.

Southeast Asia is pivotal to China’s soft power calculations, with Beijing regarding it as a crucial periphery and key arena for expanding its reach (Huong Reference Huong2023). Accordingly, China’s approach has evolved from limited engagement to active management, seeking to influence regional norms and institutions (Smith Reference Smith2019). Yet, Emmerson (Reference Emmerson2017) argues that ASEAN’s strategic behaviour increasingly reflects “default realism,” prioritizing tangible benefits and risk mitigation over normative alignment with Chinese initiatives. Realist adaptation constrains the effectiveness of China’s moral and cultural diplomacy, as Southeast Asian states often prioritize survival and strategic flexibility over ideological affinity. Reception of China’s Confucian-oriented soft power has been uneven. Domestic political systems, historical memories, territorial disputes, and evolving national identities all inform how Southeast Asian publics interpret and respond to China’s initiatives. Confucian appeals may gain more traction in states with institutional or ideological alignment with China’s political model, whereas unresolved disputes over sovereignty can provoke scepticism despite shared cultural ground.

In recent years, Confucianism has gained renewed attention as a key element of China’s soft power strategy. Many scholars have studied the philosophical underpinnings of Confucianism and its compatibility with democratic values (e.g., Carleo III Reference Carleo III2021; Huang Reference Huang2024; S. Kim Reference Kim2016; Li Reference Li2019; Yang Reference Yang2024). Quantitative research complements this philosophical work and shows that citizens who favour strong leadership and express scepticism toward institutional checks and balances are more likely to view China’s influence positively (Sanyarat and Park Reference Meesuwan and Park2025). These findings underscore how domestic political attitudes shape the regional reception of China’s soft power

This study fills the gap by empirically analysing the relationship between receptivity to Confucian values and public perceptions of China’s international role in five Southeast Asian states: Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The region’s political diversity creates a rich environment to examine how Confucian norms are received across various institutional settings. Moreover, the five countries have different relationships with Beijing. Cambodia and Thailand have strong connections, while Vietnam and the Philippines experience ongoing tensions, particularly over territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Indonesia, meanwhile, maintains a policy of strategic neutrality and balances significant economic engagement with China against assertions of its own sovereignty. These differences provide an ideal setting to assess public reactions to China’s value-based diplomacy across diverse political and geopolitical contexts.

Accordingly, the study poses the following two research questions:

RQ1. To what extent do Confucian values shape public perceptions of China’s influence at the domestic, regional, and global levels across Southeast Asia?

RQ2. How do the political system, economic exposure to China, and territorial disputes in the South China Sea moderate the relationship between Confucian values and perceptions of China’s influence?

Both questions guide examination of how China’s values-based diplomacy interacts with different domestic circumstances and strategic relationships in Southeast Asia. They also connect Confucian normative outreach directly to measurable public attitudes toward China’s influence at the national, regional, and global levels.

Soft Power, Confucianism, and Public Perception of Foreign Powers as an Analytical Framework

Soft power theory, Confucianism, and public perception form the core analytical framework of this study. The approach centres on conceptual clarity, empirical operationalisation, and the causal connections between values and perceptions.

Soft Power

Soft power has become a central concept in international relations, though its meanings and applications remain contested. Nye first introduced the term to describe the ability of states to shape the preferences of others through attraction rather than coercion. He later defined it as influence grounded in culture, political values, and foreign policy perceived as legitimate or admirable (Nye Reference Nye2004). In his more recent reflections, Nye (Reference Nye2011, Reference Nye2019) identified the growing importance of credibility in the digital age, noting that audiences now judge power less by curated images and more by the perceived authenticity of policies and practices. The power of attraction rests on resonance: influence expands when foreign publics detect harmony between a state’s projected values and their own institutional or cultural frameworks. This dynamic is evident in China’s case, where audiences interpret its outreach through Confucian lenses that can either affirm or erode perceived legitimacy.

Much of the scholarly debate since Nye has emphasized the communicative processes by which attraction is generated. Identification and narrative resonance are regarded as central to persuasion (Hayden Reference Hayden2012). Research on public diplomacy similarly argues that credibility requires dialogic interaction over unilateral projection (Melissen Reference Melissen2005). Critical perspectives redirect attention to resources. Fan (Reference Fan2008) observes that attractive assets alone rarely produce influence. Audiences interpret and evaluate external narratives through their own historical and cultural lenses. Interpretation remains contingent on moral congruence—when foreign behaviour diverges from Confucian expectations of reciprocity or restraint, attraction weakens.

Chinese discourse often frames soft power in civilisational terms, grounded in cultural depth and symbolic continuity. Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen2015) foregrounds the emotional and intellectual resonance of heritage, while Wu (Reference Wu2018) articulates the role of identity projection in sustaining appeal. Other contributions highlight the normative dimension. Hall (Reference Hall1997) links influence to moral credibility, and Ohnesorge (Reference Ohnesorge2020) positions communicative legitimacy and cultural rootedness at the core of durable attraction. Yet unresolved territorial disputes and political frictions often erode cultural affinity, prompting publics to reinterpret soft power within strategic competition.

Economic relations further complicate reception. Chinese investment in infrastructure, manufacturing, and development assistance often delivers material benefits, though concerns about dependency, unequal distribution of gains, and elite capture remain widespread (Morgan Reference Morgan2019). The public assesses initiatives economically and morally. Initiatives perceived to be fair and balanced reinforce attraction, while those seen as unequal or exploitative foster scepticism.

Thus, soft power represents a multilayered phenomenon in which meaning, legitimacy, and emotion intersect with material exchanges to produce alignment. In this study, soft power denotes a state’s capacity to influence external audiences by drawing them toward its culture, values, and models of governance, contingent on these elements being positively received by foreign publics. Influence is realized in the act of reception, not projection, when states are judged to be admirable, trustworthy, and legitimate.

Scholars increasingly consider public opinion both an indicator and an outcome of soft power. Studies of Confucius Institutes show how cultural cooperation can improve attitudes toward China (Yeh et al. Reference Yeh, Wu and Huang2021). Ji (Reference Ji, Chitty, Ji and Rawnsley2023) adds perception-based measures, namely international surveys, reputational indices, and media sentiment, which offer valuable tools for gauging attraction, provided interpretation remains context-sensitive. Positive cultural evaluations often coexist with scepticism in security or governance domains, highlighting the multidimensional nature of perception.

Consequently, this study treats public perception as the primary manifestation of soft power. Incorporating Confucian dimensions allows examination of how social ethics and political values filter and translate reception, clarifying why China’s influence gains recognition in some settings despite meeting resistance in others. The theoretical expectation is that Confucian values shape perception by furnishing the moral and relational standards—grounded in reciprocity, virtue, and legitimacy—used by foreign publics to evaluate China’s conduct and credibility.

Confucianism

Confucianism continues to underpin moral, social, and political life in Asia, remaining a flexible tradition adapting to modern governance, culture, and international relations. Its core tenets rest on moral cultivation, ethical regulation of social relationships, and political authority grounded in virtue. Leadership gains legitimacy from moral practice, while coercion undermines harmony and authority (Bell Reference Bell2008; Goldin Reference Goldin2014; Ivanhoe Reference Ivanhoe, Angle and Slote2013; Rainey Reference Rainey2010; Yu Reference Yu, Sellers and Kirste2023).

Tu (Reference Tu, Slote and Vos1998) defines Confucianism as a form of moral humanism, in which individual growth unfolds within networks of obligation. Filial piety, kindness, ritual propriety, and civic responsibility function not as private virtues but as public expectations linking family, community, and political order. Van Norden (Reference Van Norden and Mou2017) further aligns Confucian ethics with Aristotelian virtue ethics, contending moral character is cultivated by the practice of defined roles—parent, student, ruler, or citizen—where obligations are enacted in lived relationships. Both accounts underscore the relational foundation of Confucian morality.

Scholars distinguish political and ethical strands in the tradition. Fukuyama (Reference Fukuyama1995) traces the role of political Confucianism in legitimizing hierarchical authority and bureaucratic elitism. Ethical Confucianism, by contrast, promotes respect for elders, social trust, and a strong regard for education. Shin (Reference Shin2012) suggests this dual legacy allows Confucianism to constrain democratisation and strengthen civic engagement, depending on the aspect that predominates.

From the wider literature, three dimensions of Confucianism can be identified. The ethical-social domain includes family-centred obligations, interpersonal harmony, and communal trust. The political domain emphasizes the legitimation of authority through meritocracy, hierarchy, and virtuous governance. The civic-cultural domain reflects adaptation to modern contexts, visible in education, rituals, and administrative norms (S. Kim Reference Kim2020; Tseng Reference Tseng2020). Comparative research shows these values continue to shape political culture in East and Southeast Asia through historical ties, migration, and regional exchange (Shin and H. Kim Reference Shin and Kim2018; Zhao Reference Zhao2018). These dimensions provide practical standards for evaluating authority and the quality of moral governance.

For empirical purposes, the study focuses on two dimensions most relevant to perceptions of foreign powers: social ethics and political values. Social ethics centre on reciprocity, filial piety, and collective responsibility—the moral vocabulary used to judge daily conduct. Political values concern the linkage between authority and virtue, requiring rulers to act with benevolence, fairness, and discipline to maintain legitimacy. Publics across the region apply these criteria to appraise governance domestically and internationally (Bell Reference Bell2008; S. Kim Reference Kim2020; Tu Reference Tu, Slote and Vos1998).

The distinction between social ethics and political values reflects the arenas in which attraction is tested. Social ethics underpin perceptions of China’s bilateral role, as publics form views on reciprocity in trade, aid, and investment. Political values guide evaluations of China’s regional and global leadership, with claims of stewardship inviting moral scrutiny. Together, they form the normative mechanism that anchors Confucianism’s role in soft power reception—social ethics that guide perceptions of fairness and cooperation, and political values defining expectations of moral legitimacy.

In essence, Confucianism furnishes the moral compass orienting perceptions of China’s conduct. Social ethics inform views of bilateral reciprocity, whereas political values frame interpretations of China’s claims to moral leadership at the regional and global levels.

Public Perception Toward Foreign Powers

The effectiveness of soft power depends on how external audiences receive and interpret cultural, political, and policy signals. Without meaningful reception, even ambitious cultural diplomacy efforts risk superficial impact. Public opinion entails active interpretation as audiences construct, negotiate, and sometimes contest foreign narratives (Braghiroli and Salini Reference Braghiroli and Salini2014). The reception of Confucian values in China reveals both immediate reactions and long-term judgments of credibility and moral authority (Yeh et al. Reference Yeh, Wu and Huang2021).

Projection alone does not create influence; perception conditions the realisation of attraction. Evaluations of foreign powers are multidimensional, arising from tangible exchanges, comprising trade, aid, and alliances, and intangible elements like cultural narratives and political ideals (Goldsmith et al. Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush2021). Domestic contexts further filter these signals in the light of ideology, emotion, and historical memory (Xie and Jin Reference Xie and Jin2022). Some studies stress enduring structural factors, while others highlight volatility, showing how crises or diplomatic gestures can swiftly reshape opinion (He et al. Reference He, Zhang and Xie2022).

Material interaction is particularly crucial for China, as it intersects with Confucian expectations of reciprocity and fairness. Investment, loans, and development aid are judged financially and ethically. Equitable cooperation strengthens attraction and trust, whereas unequal arrangements generate scepticism and narratives of dominance. Ultimately, reception captures the dynamic interplay between short-term reactions and deeper moral appraisals of trustworthiness and normative integrity.

Understanding how these perceptions are formed requires moving beyond a simple coercion–attraction binary. The analysis builds on recent scholarship that conceptualizes influence in multiple, distinct modes (Ferchen and Mattlin Reference Ferchen and Mattlin2023). This approach distinguishes between two key elements: China’s intended actions, such as persuasion, inducement, and demonstration, and how those actions are ultimately received by foreign publics. A multimodal perspective offers crucial insight by explaining why Chinese initiatives framed in Confucian rhetoric generate divergent interpretations across contexts. The Confucian values identified constitute the moral and evaluative framework governing reception. This mechanism determines whether an act of persuasion is regarded as genuine or perceived to involve coercive or induced compliance.

Three structural moderators refine this analysis. The political system influences receptivity: consolidated democracies tend to resist hierarchical ideals; publics in less-institutionalized democracies may find Confucian models more compatible (Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Hanson, Dzutsati and DeBell2024; Shin and H. Kim Reference Shin and Kim2018). Geopolitical disputes—especially in the South China Sea—undermine trust, prompting publics in countries like Vietnam and the Philippines to interpret Chinese outreach as rivalry rather than partnership (Cull Reference Cull2022). Economic exposure also plays a significant role. Equitable engagement tends to enhance goodwill, and asymmetrical dependence often generates suspicion.

Cross-national variation within Southeast Asia illustrates these dynamics. Maritime tensions in Vietnam and the Philippines heighten scepticism, casting Chinese influence in strategic rather than cultural terms. In Thailand and Cambodia, political alignment and economic cooperation have produced more favourable attitudes, though concerns about dependency remain. Indonesia presents a mixed case, where deepening economic ties coexist with ambivalent public perceptions coloured by domestic diversity.

The analytical model (Figure 1) designates Confucian social ethics and political values the independent variables shaping perceptions of China at the domestic, regional, and global levels. Public perception at each level forms the dependent variable. Political systems, territorial disputes, and economic exposure serve as structural moderators influencing these relationships. Integrating both normative and material factors allows the framework to capture the real-world contexts in which audiences interpret China’s influence and to clarify how Confucian traditions shape evaluations of foreign power.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the relationship between Confucianism, soft power, and public perceptions of China.

Data and Methods

Data

This study uses data from the sixth wave of the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), the most comprehensive cross-national dataset linking Confucian values, democratic orientations, and perceptions of major powers in Asia. The survey was conducted between 2021 and 2022 in Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Cambodia, among respondents aged 18 and older. A total of 6419 respondents took part in the survey: 1200 from the Philippines, 1200 from Thailand, 1540 from Indonesia, 1237 from Vietnam, and 1242 from Cambodia.

Wave 6 of the Asian Barometer Survey remains the latest available round containing a full Confucianism module, making it uniquely suited to the study’s theoretical framework. More recent regional surveys—for example, The State of Southeast Asia 2025—contain questions on perceptions of China and certain soft power dimensions, including attraction to study, work, or travel there (Seah et al. Reference Seah, Lin, Martinus, Fong, Thao and Aridati2025). Yet these surveys focus on policy experts and think-tank elites rather than the general public and omit any measures of Confucian moral values. Despite its extensive coverage of social and political attitudes, the World Values Survey Wave 7 (WVS–7) contains several items that indirectly reflect Confucian and broader Asian value orientations, e.g., respect for authority, family obligations, and social harmony. However, WVS–7 does not assess public perceptions of China’s influence (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Medrano, Lagos, Norris, Ponarin and Puranen2022). As a result, neither dataset provides the conceptual or empirical basis required to examine how Confucian values anchor mass perceptions of China’s influence in Southeast Asia.

Variables

Dependent variables

Public perception of a foreign country’s role refers to the relational and mediated aggregation of external audiences’ judgments regarding the influence of a country’s external behaviour. This study gauges respondents’ perceptions of China among five Southeast Asian countries using three survey items: Q176, Q177, and Q182.

Question Q176 investigates the statement “Does China do more good or harm to Asia?” with response options coded as 1 = Much more good than harm, 2 = Somewhat more good than harm, 3 = Somewhat more harm than good, and 4 = Much more harm than good.

Question Q177 focuses on the item “Generally speaking, the influence China today has on world affairs is,” and Q182 measures attitudes toward “Generally speaking, the influence China has on our country is.” Both questions Q177 and Q182 employ a six-point scale: 1 = Very positive, 2 = Positive, 3 = Somewhat positive, 4 = Somewhat negative, 5 = Negative, and 6 = Very negative.

In all three questions, higher values initially corresponded to less favourable perceptions of China. To ensure interpretive consistency, the dependent variables were recoded so that higher values correspond to more positive perceptions. The items conceptually align with soft power understood as received influence—how external audiences perceive a state’s legitimacy, moral credibility, and attractiveness (Nye Reference Nye2004, Reference Nye2019). Positive evaluations in these domains signify the extent to which China’s actions and values generate voluntary approval instead of coercive compliance. This approval, defined by attitudinal reception, operationalises soft power, excluding reliance on institutional output. Public judgments of influence mark a direct and observable proxy for the level of non-coercive attraction China commands. Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for each item.

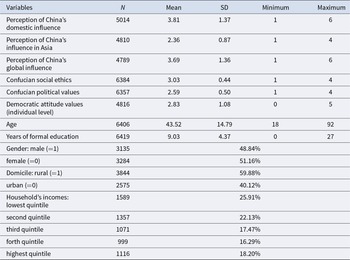

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of variables

Note: All items and composite indices are recoded so that higher values represent stronger positive evaluations—specifically, more favourable perceptions of China and stronger endorsement of Confucian attitudes. Percentages for categorical variables indicate the proportion of total respondents.

To isolate the distinct facets of public perception, each of the three survey items—perceptions of China’s role in Asia (Q176), its global influence (Q177), and its influence on the respondent’s own country (Q182)—was treated as a separate dependent variable. This study, therefore, presents the results of three separate regression models, allowing for an in-depth analysis of how Confucian values and other factors shape these different dimensions of China’s perceived influence.

Independent variables

Confucianism was measured using selected items from the ABS, based on established approaches in the literature. Questions Q56, Q57, Q58, Q59, Q60, Q62, Q63, Q64, Q65, Q132, Q137, Q149, Q150, and Q154 were chosen based on the conceptual frameworks of Shin (Reference Shin2012) and Huang (Reference Huang2024). Although the wording and coverage differ slightly, the items reflect the same theoretical foundations for identifying two dimensions of Confucianism: Confucian social ethics, centred on harmony, reciprocity, and moral conduct, and Confucian political values, emphasizing hierarchy, moral authority, and virtuous governance. Each question in the ABS is scored on a four-point scale (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree). All items were reverse-coded; higher scores signify stronger endorsement of Confucian attitudes.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to extract underlying factors and to assign questions to their respective dimensions. Table 2 presents the details of the questions included and the PCA results. Questions Q56, Q57, Q58, Q59, Q63, Q64, and Q65 show statistically significant correlations with the Confucian social ethics dimension. A loading score of 0.4 or above was set as the threshold for inclusion into each category (Hair, Jr. et al. Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2019). For the Confucian political values index, questions Q62, Q132, Q137, Q149, Q150, and Q154 met the criteria.

Table 2. Factors loading of Confucian social ethics and Confucian political values

Note: KMO and Bartlett’s test using Principal Component Analysis .796, p<0.001, 36.31 contribution to variance; Cronbach’s Alpha: Confucian social ethics .725, Confucian political values .645, N=5040.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy exceeded 0.70, indicating sufficient intercorrelations among the variables and confirming the suitability of factor analysis. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, in addition, yielded statistically significant results, supporting the appropriateness of the factor structure.

Reliability of the question groupings was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha. The Confucian social ethics and political values groups both reported Alpha values above 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency (Nunnally and Bernstein Reference Nunnally and Bernstein1994). Composite indices for each group of questions were subsequently created.

Explanatory and Control Variables

The analysis incorporates several variables to address alternative explanations and moderating effects while building a comprehensive model to test the study’s second research question. These variables comprise individual-level factors such as democratic values and key demographics, as well as country-level factors such as the national political system, economic exposure to China, and involvement in territorial disputes.

Democratic values were gauged using five items from the Asian Barometer Survey that reflect cognitive engagement with foundational democratic principles (Huang Reference Huang2024). The items addressed a range of beliefs, from regime preference to institutional trade-offs. Q124 asked respondents to express their general stance on the political system by selecting from three options: democracy is always preferable; authoritarianism may be acceptable in some cases; or regime type is of no concern. In Q125, respondents indicated whether they believe democracy can solve societal problems. Q126 presented a choice between prioritizing democracy or economic development. The survey then moved to Q127, which forced a choice between safeguarding political freedom and mitigating economic inequality. Finally, Q128 examined agreement with the idea that, despite its flaws, democracy remains the optimal form of government. Collectively, these questions probe different dimensions of democratic belief, each of which links back to a core element of political reasoning (Shin and H. Kim Reference Shin and Kim2018).

Responses were recoded into a binary format, with each item assigned a value of 1 when it reflected support for a democratic principle and 0 otherwise. The resulting five dichotomous variables were summed into a composite scale ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores signalled stronger endorsement of democratic norms. Cronbach’s alpha records an internal consistency of 0.363 for the index. A low value of this nature is anticipated because the index is an additive indicator of distinct democratic orientations, not a unidimensional scale of a single latent trait. The additive approach, following Freeze and Montgomery (Reference Freeze and Montgomery2016), is suitable for capturing belief consistency spanning multiple facets of democratic cognition. This composite variable was used as an explanatory factor in the regression analysis to assess variation in support for democratic governance at the individual level.

Alongside these micro-level attitudes, the analysis integrates country-level indicators to capture structural and geopolitical factors that influence perceptions of China (see Table 3). The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2021 Democracy Index provides a standardised measure of regime quality on a ten-point scale covering five dimensions: electoral process, government function, participation, political culture, and civil liberties. The inclusion enables cross-national comparison of democratic development. Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand fall under flawed democracies; Cambodia and Vietnam fall under authoritarian regimes.

Table 3. Country-level indicators of democracy, economic exposure, and territorial disputes in the South China Sea

Note: All data refer to 2021. FDI and GDP figures are reported in billions of US dollars (current prices). Democracy Index scores are from the Economist Intelligence Unit (scale 0–10) (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022). FDI data are drawn from the IMF Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS), and GDP data are from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database (International Monetary Fund, 2025). FDI-to-GDP ratio (%) expresses Chinese FDI as a share of national GDP. The variable Disputes with China is coded 1 for countries involved in the South China Sea disputes (Philippines, Vietnam) and 0 otherwise.

Economic exposure to China is represented by the share of Chinese outward foreign direct investment (FDI) relative to each country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021. The ratio, calculated using FDI data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), captures the scale of Chinese investment in proportion to domestic economic output. Higher ratios of FDI to GDP reflect stronger economic reliance on Chinese investment. Among the five countries, exposure to China is most pronounced in Cambodia, which reflects strong integration into the Chinese economic orbit. The relatively low ratios in the other Southeast Asian states show that economic ties with China are significant, but these ties remain less dominant within their overall economic structures.

The 2021 reference year was selected, given that survey data were collected between 2021 and 2022, ensuring country-level indicators reflect the actual conditions participants experienced at the time of their responses.

Finally, participation in the South China Sea disputes is treated as a geopolitical variable, coded 1 for countries involved in territorial conflicts with China (the Philippines and Vietnam) and 0 for those without such disputes (Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia) (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Dolven and O’Rourke2023).

Controls for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were incorporated to strengthen the validity of the analysis: gender, rural–urban residency, education, age, and household income. Existing research advises that differences in political attitudes, exposure to international narratives, and responsiveness to cultural messaging often reflect underlying social structures (Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Accounting for these factors helps ensure observed associations constitute genuine relationships, free from background variation across individuals.

Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical framework linking Confucian values to soft power reception through public perception, this study advances three hypotheses addressing how social ethics and political values shape evaluations of China under different contextual conditions.

H1. Confucian social ethics will be significantly associated with perceptions of China’s influence at domestic, regional, and global levels.

Social ethics provide standards for judging interactions between states and publics (Tu, Reference Tu, Slote and Vos1998). These principles favour balanced exchange and long-term relationships over purely transactional ones. Therefore, audiences with strong Confucian social ethics form perceptions of China depending on whether its economic engagement seems genuinely reciprocal or produces asymmetric dependency.

H2. Confucian political values will be significantly associated with perceptions of China’s influence at domestic, regional, and global levels.

Confucian political thought offers a distinct lens for assessing leadership. While legitimate authority requires moral cultivation and virtuous governance (Bell Reference Bell2008; Shin Reference Shin2012), the tradition also accommodates hierarchical rule. This duality means that public perception will depend on whether audiences prioritise moral virtue or acceptance of hierarchy when judging China’s conduct.

H3. The relationships between Confucian values and perceptions of China will be moderated by the political system, economic exposure to China as measured by the FDI-to-GDP ratio, and territorial disputes with China.

The effect of Confucian values does not occur in a vacuum. Broader national contexts—political systems, economic ties, and geopolitical tensions —structure this relationship. Liberal democratic norms of popular sovereignty may clash with certain Confucian ideals, economic dependence may complicate perceptions of reciprocity, while territorial disputes can introduce strategic distrust and override cultural affinity. This hypothesis posits that these contextual factors will significantly moderate how Confucian values translate into public perceptions of China, a proposition warranting empirical verification through interaction analysis.

Analysis Strategy

The three dependent variables measuring perceptions of China’s influence are analyzed using ordered probit models, which are appropriate for ordinal outcomes. Coefficients represent changes in the latent propensity toward a more positive evaluation.

Two key explanatory variables characterise the theoretical dimensions of Confucianism: social ethics (Socᵢ) and political values (Polᵢ). Individual democratic attitudes (Demᵢ), measured on a 0–5 scale, capture support for democratic principles. Additional individual-level controls (Xᵢ′γ) consist of income quintile, rural or urban residence, gender, age, and years of education. Country-level predictors encompass broader structural contexts: the Democratic Index (Democ c(i)), the Chinese FDI-to-GDP ratio (FDI/GDP c(i)), and the presence of territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea (Disputes c(i)).

Because respondents were drawn from five countries, their answers may reflect unobserved national-level effects. To address possible within-country dependence in the error terms, the analysis employs robust standard errors clustered by country. Although the small number of clusters (five) may yield slightly conservative standard errors in some specifications, the method is accepted in comparative political science research (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Cameron and Miller Reference Cameron and Douglas2015).

To test the moderating role of national context proposed in H3, the analysis includes cross-level interaction terms between each Confucian value dimension and the macro-level variables. These interactions determine whether the effects of Confucian orientations differ by democratic consolidation, economic exposure, or geopolitical tension. Significant interaction coefficients indicate that the influence of Confucian values depends on a given national condition, and their interpretation is supplemented by marginal effects and predicted probabilities.

The analysis proceeds through a series of nested models:

Model 1: Baseline individual-level model

Model 2: Adding country-level contextual variables

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{}} = {\textrm{Model}}1{\textrm{}} + {\delta _1}Demo{c_{c(i)}} + {\delta _2}FDI/GD{P_c}_{(i)} + {\delta _3}Dispute{s_{c(i)}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{}} = {\textrm{Model}}1{\textrm{}} + {\delta _1}Demo{c_{c(i)}} + {\delta _2}FDI/GD{P_c}_{(i)} + {\delta _3}Dispute{s_{c(i)}}\end{equation*}Model 3: Confucian social ethics with interaction effects

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{ }} = {\textrm{ Model }}2{\textrm{ }} + {\theta _1}\left( {So{c_i} \times Demo{c_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{ }} + {\theta _2}\left( {So{c_i}{\textrm{ }} \times FDI/GD{P_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{ }} + {\theta _3}(So{c_i}{\textrm{ }} \times Dispute{s_c}_{\left( i \right)})\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{ }} = {\textrm{ Model }}2{\textrm{ }} + {\theta _1}\left( {So{c_i} \times Demo{c_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{ }} + {\theta _2}\left( {So{c_i}{\textrm{ }} \times FDI/GD{P_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{ }} + {\theta _3}(So{c_i}{\textrm{ }} \times Dispute{s_c}_{\left( i \right)})\end{equation*}Model 4: Confucian political values with interaction effects

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{}} = {\textrm{Model}}2{\textrm{}} + {\varphi _1}\left( {Po{l_i} \times Demo{c_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{}} + {\varphi _2}\left( {Po{l_i} \times FDI/GD{P_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{}} + {\varphi _3}\left( {Po{l_i} \times Dispute{s_{c(i)}}} \right)\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\eta _i}{\textrm{}} = {\textrm{Model}}2{\textrm{}} + {\varphi _1}\left( {Po{l_i} \times Demo{c_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{}} + {\varphi _2}\left( {Po{l_i} \times FDI/GD{P_{c(i)}}} \right){\textrm{}} + {\varphi _3}\left( {Po{l_i} \times Dispute{s_{c(i)}}} \right)\end{equation*}All models were estimated via maximum likelihood with cluster-robust standard errors. Statistical analyses were conducted using a combined software approach. Descriptive statistics, correlation tests, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), including factor loadings, were computed in SPSS. Ordered probit regressions, the computation of marginal effects, and variance inflation factors (VIF) were carried out in Python 3.12 on Google Colab, utilizing the statsmodels library (version 0.14.5). For each dependent variable—perceptions of China’s domestic, regional, and global influence—the study reports coefficient estimates, log-likelihood, AIC, BIC, McFadden R 2, and the number of observations and clusters. This combination creates a theoretically consistent and statistically rigorous framework for examining how Confucian values shape public perceptions of China’s influence in Southeast Asia.

Research Findings

Confucian Social Ethics and Perceptions of China

The ordered probit results substantiate substantial support for H1 and reveal how Confucian social ethics surface in perceptions of China’s influence at the domestic, regional, and global levels. The relationship is conditional and varies systematically with evaluative context.

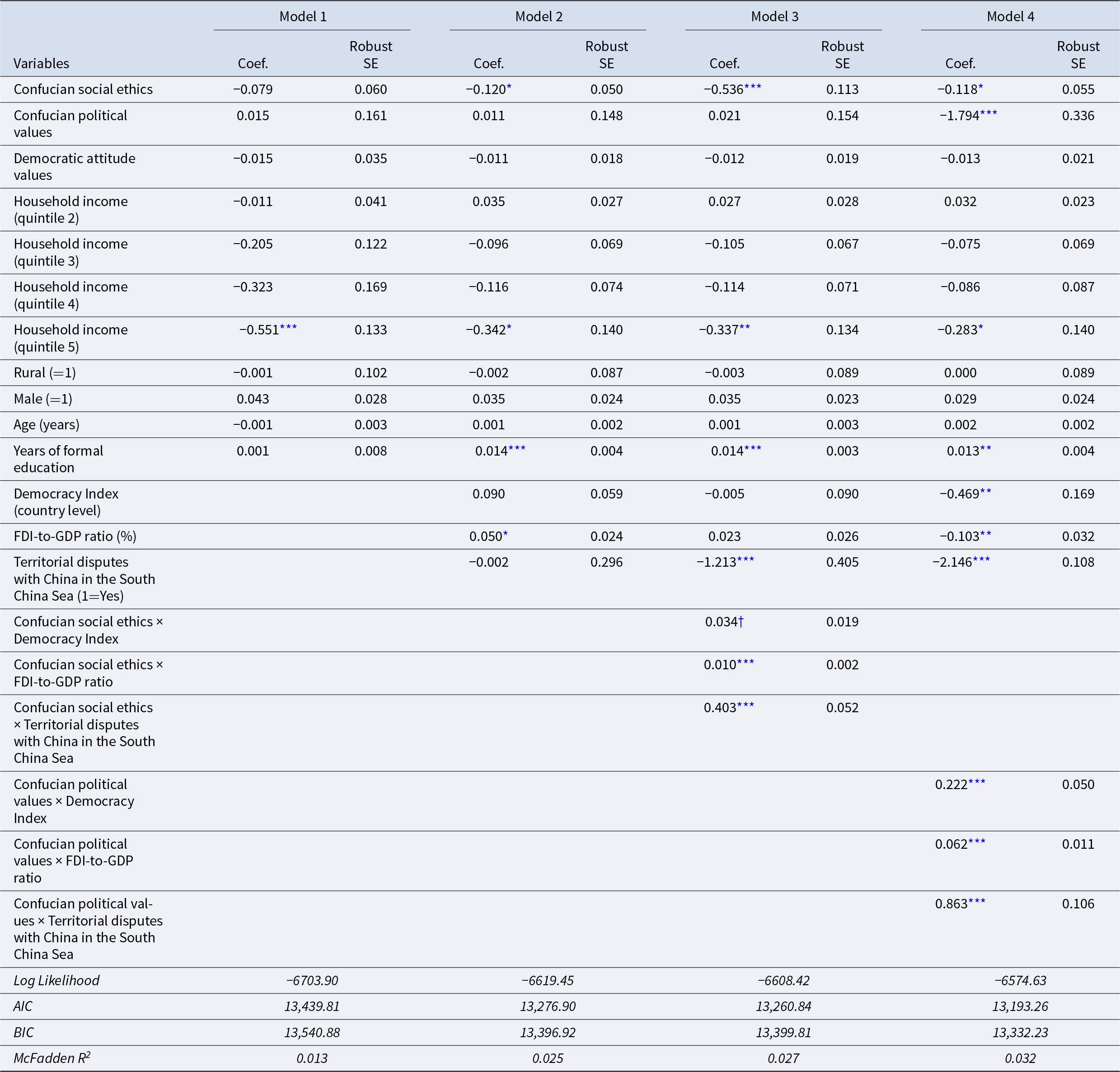

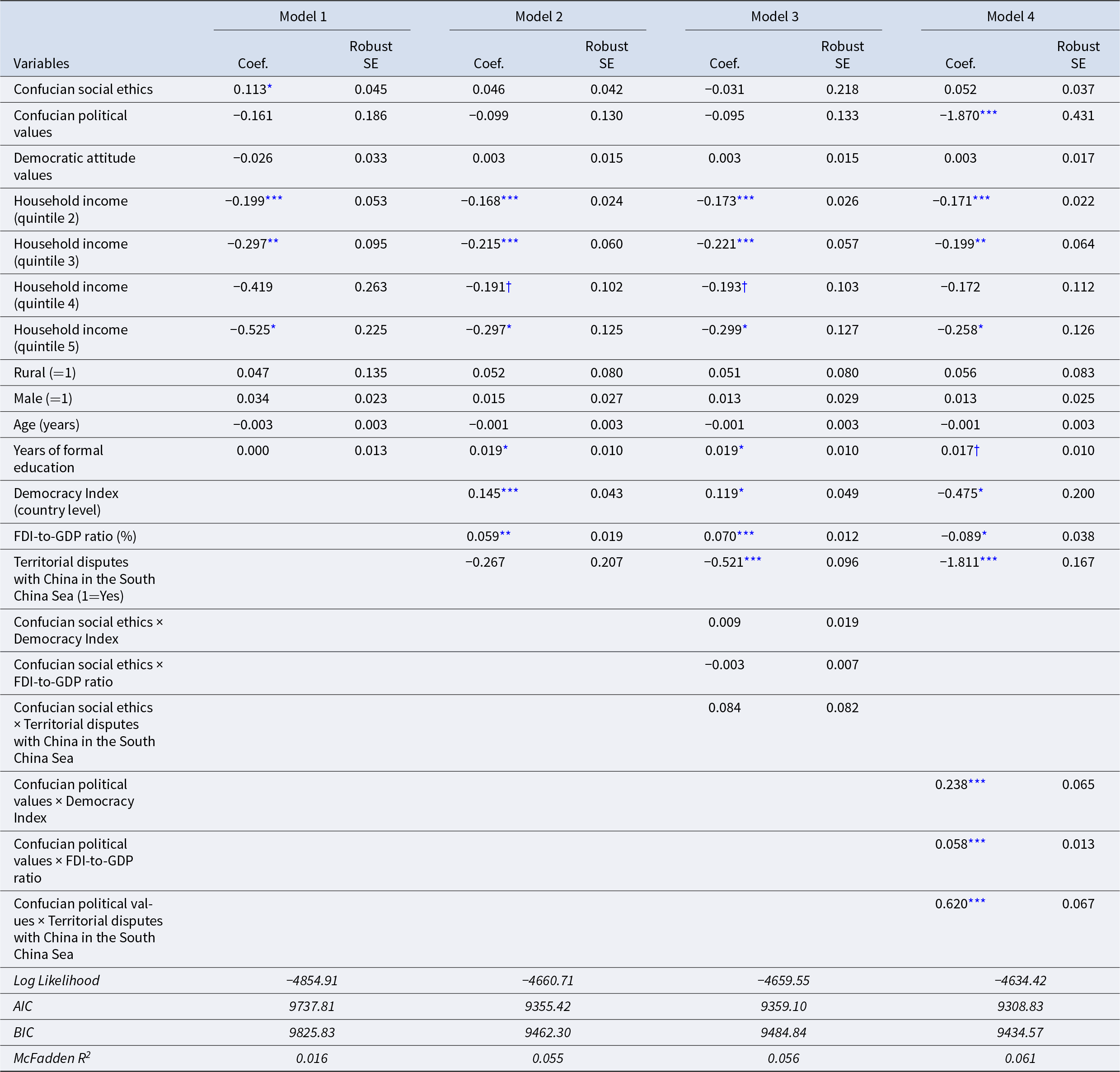

Domestic perceptions illustrate this context-dependent trend (Table 4). Social ethics have limited explanatory weight in the baseline model (Model 1: −0.079, n.s.). The inclusion of structural variables produces a negative and significant coefficient (Model 2: −0.120, p < .05), setting a key evaluative benchmark. People who emphasise reciprocity, trust, and collective responsibility tend to scrutinise China’s domestic influence more critically. Approval emerges only when behaviour shows benevolence and mutual balance.

Table 4. Ordered probit regression results for perception of China’s domestic influence across five Southeast Asian countries

† Note: N = 4092; clusters = 5 (five countries). Coef. = coefficient; Robust SE = robust standard error. Significance levels:p < .10;

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001. For Models 3 and 4, the coefficients for the non-interacted variables represent the conditional effects when the corresponding macro-level moderators are set to zero.

Introducing interaction effects deepens this pattern in Model 3. When Chinese economic engagement forms a larger share of national GDP, the social ethics × FDI-to-GDP term is positive and highly significant (0.010, p < .001). Publics with strong social ethics interpret deeper economic integration as evidence of reciprocity and shared prosperity, leading to more favourable evaluations. Territorial disputes produce a comparable effect. The social ethics × dispute coefficient (0.403, p < .001) indicates individuals with strong social ethics maintain restraint under geopolitical strain. Their evaluations embody relational reasoning that values reciprocal balance and the possibility of renewed stability. The addition of these interaction terms substantially enhances explanatory power (McFadden R 2 rises from 0.013 to 0.027).

Regional perceptions present a distinct configuration (Table 5). Social ethics report initial significance in Model 1 (0.113, p < .05) and diminished explanatory power once controlling for macro-level variables (Model 2: 0.046, n.s.). Interaction terms in Model 3 similarly fail to reach significance. These patterns suggest a shift toward structural rather than moral evaluation. At this level, public attitudes centre on China’s role within the Southeast Asian state system, where bilateral relationships and territorial claims override interpersonal moral frameworks. Structural factors drive model performance substantially (McFadden R 2 jumps from 0.016 to 0.056), confirming that strategic considerations outweigh moral reasoning in regional assessments.

Table 5. Ordered probit regression results for perception of China’s regional influence across five Southeast Asian countries

† Note: N = 3972; clusters = 5 (five countries). Coef. = coefficient; Robust SE = robust standard error. Significance levels:p < .10;

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001. For Models 3 and 4, the coefficients for the non-interacted variables represent the conditional effects when the corresponding macro-level moderators are set to zero.

Global perceptions (Table 6) largely mirror domestic patterns, albeit with smaller effect sizes. Social ethics again turn negative and significant after accounting for structural variables (Model 2: −0.088, p < .01). Interaction effects in Model 3 exhibit consistent contextual patterns. Economic engagement reinforces favourable evaluations (social ethics × FDI: 0.008, p < .001), and heightened geopolitical tension does not lead to outright rejection (social ethics × Disputes: 0.149, p < .05). Incorporating context-dependent mechanisms progressively strengthens model specification (McFadden R 2 advances from 0.012 to 0.037).

Table 6. Ordered probit regression results for perception of China’s global influence across Five Southeast Asian countries

† Note: N = 3977; clusters = 5 (five countries). Coef. = coefficient; Robust SE = robust standard error. Significance levels:p < .10;

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001. For Models 3 and 4, the coefficients for the non-interacted variables represent the conditional effects when the corresponding macro-level moderators are set to zero.

At all three analytical levels, Confucian social ethics inform public evaluations of China through adaptive moral reasoning. Even amid geopolitical tension, individuals guided by these values tend toward balanced and measured judgments, emphasizing relational stability over confrontation. The pattern is most pronounced at the domestic and global levels, while regional outcomes reflect the dominance of structural geopolitics in shaping perception frameworks.

Confucian Political Values and Perceptions of China

Confucian political values operate differently from social ethics, lending strong support to H2 and highlighting that political Confucianism depends on situational activation instead of forming baseline attitudes.

Political values yield no significant main effects across analytical levels. At the domestic level (Table 4), coefficients remain insignificant in Models 1 and 2, suggesting no foundational link between political Confucianism and domestic perceptions when structural influences are taken into account. Model 4 reverses this pattern. Where democratic institutions are stronger, individuals with Confucian political orientations evaluate China more favourably (political values × Democracy Index: 0.222, p < .001), possibly because they perceive institutional complementarity or benefit from information openness in pluralistic settings. Economic linkages produce a comparable effect. Material ties encourage audiences with Confucian frameworks to interpret Chinese influence as aligned with national prosperity (political values × FDI-to-GDP: 0.062, p < .001). The strongest activation occurs under geopolitical tension. Even in dispute contexts, political Confucianism corresponds with less hostile evaluations (political values × Disputes: 0.863, p < .001), a pattern consistent with governance traditions that prioritise accommodation over confrontation. Model fit improves modestly (McFadden R 2 from 0.025 to 0.032), affirming the explanatory value of these conditional relationships.

Regional perceptions (Table 5) highlight China’s strategic position among neighbouring states, defined by alliances, power balances, and rivalries. Political value interactions contribute additional explanatory depth (McFadden R 2 from 0.055 to 0.061), even within a domain dominated by state-level factors. All three interaction terms are positive and statistically significant—political values × Democracy Index (0.238, p < .001), political values × FDI (0.058, p < .001), and political values × Disputes (0.620, p < .001)—results consistent with hierarchically oriented publics maintaining approval when institutional quality, economic ties, or territorial tensions become salient.

Globally (Table 6), the overall pattern holds. Political values display no main effect (Model 2: −0.073, n.s.). Nonetheless, when moderated by structural conditions in Model 4, their influence intensifies: Democracy (0.167, p < .001), FDI (0.065, p < .001), and Dispute (0.822, p < .001). These substantively large coefficients show that Confucian political frameworks profoundly shape evaluations of China’s global normative leadership, particularly under contexts of democratic governance, economic interdependence, and geopolitical tension.

Comparative Interpretation and Substantive Effects

Figure 2 synthesises regression results from Tables 4–6 through coefficient plots at all three analytical levels. At the domestic scale (Panel A), the two Confucian dimensions exhibit contrasting logics. Social ethics turn increasingly hostile from Model 2 to Model 3, establishing a baseline of moral scrutiny. Political values, conversely, shift from initial scepticism in Model 4 to strong approval when democracy, FDI, and disputes activate hierarchical reasoning. The regional scale (Panel B) sharpens this contrast—social ethics interactions disappear entirely while political values maintain positive relationships under each moderator. Global patterns (Panel C) parallel domestic findings, with political values producing consistently larger interactions than social ethics.

Figure 2. Ordered probit regression coefficient plots for perceptions of China’s influence. The figure presents the estimated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals across four nested models for three dependent variables: (A) domestic influence, (B) regional influence, and (C) global influence.

Social ethics impose consistent evaluative standards, softened only under specific material or geopolitical circumstances. Political values, by contrast, remain dormant until institutional or strategic contexts trigger hierarchical accommodation. Social ethics fail to engage regional assessments because interpersonal moral logic struggles with strategic calculations among states.

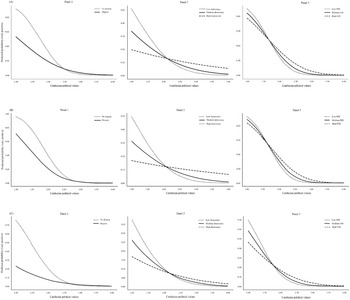

Marginal effects convert regression estimates into changes in probability. Supplement Figure 1 traces social ethics at the domestic and global levels (regional effects are absent). Individuals with strong social ethics tend to move toward more favourable domestic views when territorial disputes arise, or FDI deepens, a tendency driven by relational norms that prioritise pragmatic engagement over rigid antagonism. Global patterns follow similar trajectories at reduced intensity, consistent with moral frameworks operating most forcefully in proximate contexts.

Figure 3 maps political values over nine panels—three moderators at three analytical levels. Domestically, high political Confucianism predicts scepticism in low-democracy, low-FDI, non-dispute settings. In the presence of disputes, it reverses, as hierarchical accommodation tends to override sovereignty concerns. Regionally, political values maintain distinctive traction: all three moderators substantially alter probability distributions, which confirms that governance-oriented frameworks extend across multiple strategic scales. Global appraisals follow suit, with disputes again producing the strongest effects.

Figure 3. Predicted Probability of favourable perceptions conditioned by contextual factors. The figure displays the marginal effect of Confucian political values on the probability of reporting a positive influence (y-axis) as moderated by three contextual variables, organized by panel: Panel 1 (territorial disputes in the South China Sea), Panel 2 (democratic index), and Panel 3 (FDI-to-GDP ratio). Sub-panels (A), (B), and (C) correspond to domestic, regional, and global influence, respectively.

Political values generate larger contextual effects than social ethics in nearly all scenarios. Critically, at the regional level, political values operate in domains that social ethics cannot, demonstrating that hierarchical governance frameworks possess both broader applicability and greater mobilizing potential than interpersonal moral standards.

Aggregate patterns mask important national variation (Supplement Table 1). A striking paradox emerges in Cambodia: negative social ethics correlations (domestic: −0.089, p < .01; global: −0.085, p < .05) alongside null political values suggest moral disillusionment with Chinese conduct despite Phnom Penh’s strategic alignment—economic dependency and political partnership fail to override relational disappointment. This dynamic inverts entirely in the Philippines, where political values correlate positively at the domestic (0.201, p < .01), regional (0.108, p < .01), and global (0.122, p < .01) levels while social ethics remain inert. Manila’s accommodation strategy under Duterte and Marcos Jr., emphasizing infrastructure deals and downplaying maritime disputes (Velasco and Bacay Reference Velasco and Bacay2024), resonates with hierarchically minded publics who prioritise stability over sovereignty assertions.

The remaining three cases illustrate how national environments shape value activation. Social ethics in Thailand register significance at the regional level (0.160, p < .01). As ASEAN’s central hub, Thailand experiences Chinese economic activity—trade, tourism, and Mekong cooperation—more directly than neighbouring states (Suebpong Reference Suksom2024), making regional judgment particularly salient. Political values show weak domestic effects (0.094, p < .05); authoritarian governance appears insufficient to activate hierarchical orientations without tangible economic benefits. Vietnam diverges sharply. Negative regional correlations for political values (−0.112, p < .01) align with findings from Vu et al. (2024), who document how decades of maritime disputes and historical tensions obstruct accommodation even under shared communist governance. Territorial rivalry supersedes cultural affinity. Indonesia displays null results for both Confucian dimensions. In this Muslim-majority, non-claimant nation, neither moral nor hierarchical frameworks substantially influence China attitudes, though interaction models still detect contextual dynamics absent in bivariate analyses.

Multicollinearity diagnostics validate model specifications (Supplement Table 2): FDI-to-GDP (5.75), Democracy Index (4.76), interaction terms (2.88–4.57), and core variables (2.30–2.74) all fall below conventional thresholds (VIF < 10). Individual-level variables exhibit minimal collinearity (1.02–2.06). Overall, the findings strongly support H1 and H2 and offer partial support for H3. Confucian social ethics and political values shape perceptions of China’s influence, while their effects vary with democracy, economic exposure, and geopolitical tension.

Discussion

These findings challenge Nye’s (Reference Nye2004) belief that shared values naturally attract others. Cultural affinity by itself does not secure legitimacy. In Southeast Asia, Confucian ideals—moral or political—work less as inherited bonds than as interpretive frames for understanding China’s behaviour. Values set the parameters of interpretation and organise the formation of allegiance. Attraction arises when moral expectations are met through credible action.

Confucian social ethics capture this process most vividly. Specifically, people who prize reciprocity, sincerity, and collective responsibility are not automatically sympathetic toward China. Approval grows when engagement reflects mutual benefit; its absence, by contrast, prompts scepticism. In short, moral consistency, more than cultural resemblance, sets the horizon for how audiences judge China’s behaviour. Shin (Reference Shin2012) reminds us virtue in the Confucian tradition must be enacted, not declared. When Chinese conduct conveys respect and restraint, observers interpret it within a moral lens grounded in virtue. Once actions appear self-serving or opaque, the lens turns critical.

Survey evidence from the ASEAN Studies Centre’s State of Southeast Asia 2025 report supports this interpretation, showing how admiration for China’s economic rise coexists with unease about its strategic motives (Seah et al. Reference Seah, Lin, Martinus, Fong, Thao and Aridati2025). Regionwide, the public respects China’s accomplishments while questioning its intentions. The tension between esteem and suspicion delineates how moral reasoning operates—it rewards perceived sincerity and exposes coercion.

Political Confucianism follows a subtler course. Ideas of hierarchy, harmony, and competent governance derive their meaning from the social and political environments in which they are embedded. In settings marked by stable institutions, deep economic ties, or peaceful dispute management, citizens inclined toward hierarchical reasoning interpret order and restraint to imply reliability. W. Wang (Reference Wang2024) posits that hierarchy acquires moral weight when exercised with benevolence, a pattern echoed in the data. Leadership demonstrating cooperation and competence strengthens approval among hierarchically minded publics, whereas displays of domination transform the same moral language into a source of distrust. Therefore, political Confucianism constitutes a conditional interpretive frame, defined by circumstance rather than inherited identity.

The adaptability of this reasoning pinpoints how Confucian traditions have evolved into flexible instruments of judgment. Ferchen and Mattlin’s (Reference Ferchen and Mattlin2023) multimodal framework clarifies the process by distinguishing between persuasion, inducement, and demonstration as distinct modes of soft power. China’s engagement in Southeast Asia moves across these modes, with Confucian values shaping the moral evaluation of each. Mutually beneficial projects suggest persuasion; secretive or coercive initiatives expose inducement. Confucianism, thereby, provides the moral vocabulary that enables citizens to discern the difference between credible persuasion and strategic manipulation.

Hierarchy, too, carries this ambivalence, functioning like a situational moral lens. Authority built on hierarchy is delicate, sustained by performance and moral restraint. Shih (Reference Shih2022) terms such a dynamic a “balance of relationships”: authority promotes harmony so long as relationships remain reciprocal and performance credible. A decline in performance converts the ideals that conferred legitimacy into the very grounds for its discredit.

The regional mosaic underscores how moral reasoning adapts to local ethical landscapes. In political orders that emphasise hierarchy or stability, Confucian values tend to resonate more strongly. However, in societies shaped by conflictual histories or alternative religious traditions, their influence fades. These contrasts show that Confucian soft power does not travel as a uniform moral export, but emerges in dialogue with indigenous ethical vocabularies. According to Xi and Primiano (Reference Xi and Primiano2020), the moral terrain of Southeast Asia is plural: Buddhist, Islamic, and syncretic traditions continually reshape the interpretation of Confucian concepts. The force of Confucianism abroad, hence, lies less in cultural transmission than in moral translation.

This diversity also underscores the limits of China’s moral diplomacy. When moral appeals intertwine with nationalism, Callahan (Reference Callahan2015) demonstrates, the China Dream narrative often elicits scepticism. Such instrumentalisation drains Confucianism of its ethical depth and transforms virtue from a source of attraction into a strategic burden (Lo and Pan, Reference Lo and Pan2016). Virtue as a device for strategy undermines persuasion. The harmonious world and Chinese Dream narratives embody this tension: they inspire when they seem genuine, yet calculation breeds suspicion (Hagström and Nordin, Reference Hagström and Nordin2020; Rezepa, Reference Rezepa2025). Moral language then creates normative pressure. Beijing’s invocation of virtue elevates the very moral bar it must clear—falling short erodes its credibility more sharply than remaining silent would.

The implications of this analysis are twofold. China’s regional legitimacy depends on moral congruence between declared values and observable behaviour. The resurgence of Confucianism in Chinese foreign discourse, exemplified by the Confucius Institutes and people-to-people connectivity in the Belt and Road Initiative, generates normative expectations, the disappointment of which renders its moral appeal vulnerable. The multimodal framework underscores the reciprocal nature of influence. Preserving moral credibility depends on policy coherence and perceptual awareness, since meaning lies in interpretation, not in intention.

Comparative evidence suggests China’s moral appeal is mediated by plural ethical landscapes. Future research should examine these interpretive differences through qualitative approaches sensitive to context, such as ethnographic interviews, experimental framing studies, or discourse analyses focused on specific countries, to unpack how Confucian moral reasoning is localised or resisted.

Conclusion

The findings point to a broader shift in how influence operates in international politics: power now depends less on cultural persuasion and more on moral credibility. China’s turn to Confucian ideas in diplomacy illustrates this transition, revealing both the promise and the difficulty of grounding international legitimacy in virtue while pursuing strategic aims.

In Southeast Asia, public reactions remain diverse. Trust emerges from ongoing negotiation between China’s ethical claims and the expectations of those who evaluate them.

This evolving dynamic reflects a broader transformation in world politics. With ethical traditions diverging, moral authority can no longer rest on universal narratives. It must be earned through consistent conduct and reciprocal respect. The renewed appeal to Confucian philosophy thus marks more than a cultural revival—it signals the return of morality as a measure of power in an increasingly contested international order.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2025.10013.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical Statement

This study utilises secondary data from the Asian Barometer Survey, which adheres to strict confidentiality protocols. No identifiable personal information is disclosed in the dataset. Exempt approval was obtained (Approval Number: 291-203/2025).

AI Assistance Declaration

The authors employed ChatGPT, Grammarly, and Gemini to improve the manuscript’s language clarity and readability. Additionally, Gemini was used to assist in generating Python code for statistical analysis conducted in Google Colab. All AI-generated outputs, including code and text, were carefully reviewed and validated by the authors to ensure accuracy and integrity. The authors assume full responsibility for all content in the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data analysed in this article were collected by the Asian Barometer Project (sixth wave). The ABS project was co-directed by Yun-han Chu and Min-hua Huang and received funding support from the National Science and Technology Council, Academia Sinica, and National Taiwan University. The data can be accessed at https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10.

Funding statement

This research was funded by Mahasarakham University in Thailand.