Symbolic Class Signalling and Voting

The relationship between social class and voting has become more complex. One-dimensional political competition structured around economic redistribution has lost in importance, as ‘new left’ and populist radical right parties have put cultural issues in the spotlight (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). This has created new social identities that align along a cultural divide (Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann and Kriesi2015; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024). Nevertheless, several studies show that class identities still exist and continue to shape electoral behaviour, even though it is not as simple as it was in the past, when workers were the main constituents of left-wing parties (Angelucci and Vittori Reference Angelucci and Vittori2023; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Stubager and Langsæther2022; Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2017; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). However, the literature has only started to address the question of how parties and politicians appeal to existing class identities beyond traditional class politics.

In this letter, we argue that symbolic class signalling has gained importance as a result of the political realignment. We rely on an emerging literature in political sociology that argues that politicians can appeal to symbolic class identities by embedding them in cultural rather than economic class appeals (Westheuser Reference Westheuser2020; Westheuser and Zollinger Reference Westheuser and Zollinger2025; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024). Specifically, politicians can emphasize different forms of ‘cultural consumption’ – that is, cultural tastes and preferences such as music, cuisine, or arts – to signal attachment to a certain class identity (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984, Reference Bourdieu1998; Chan and Goldthorpe Reference Chan and Goldthorpe2007; Katz-Gerro Reference Katz-Gerro2004; Prieur and Savage Reference Prieur and Savage2013). For example, drinking beer in a pub may evoke symbolic associations with working-class identities, while drinking wine or prosecco is linked to upper-class identities (Westheuser Reference Westheuser2020). Despite the long sociological tradition of studying cultural consumption, its electoral consequences have rarely been studied with systematic quantitative empirical analysis.

We claim that symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption is particularly effective for politicians to attract voters on the socio-cultural divide, especially populist radical right voters. In part, this may be due to a purely compositional effect: contemporary radical right parties draw substantial support from the working class (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018), so politicians highlighting working-class cultural consumption are likely to gain support among these voters. However, although working-class voters are by no means limited exclusively to the radical right (for example, Angelucci and Vittori Reference Angelucci and Vittori2023), we expect that symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption is less effective among working-class voters of centre-left and centre-right parties. These parties have always politicized along the traditional class cleavage, while radical right parties neither have a long-standing history of class conflict nor do they provide a coherent economic agenda that signals class affinity in different ways (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967). Moreover, culturally embedded symbolic class identities may appeal to the radical right’s working-class voters because cultural consumption is more closely related to Weberian social status than to an economic understanding of class (Chan and Goldthorpe Reference Chan and Goldthorpe2007). Politicians signalling working-class affinity through cultural consumption can thus also address status concerns that have been shown to play a major role in radical right voting (Engler and Weisstanner Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020).

In this letter, we analyse the electoral success of politicians’ symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption across voters from different parties and socioeconomic backgrounds. Our empirical analysis builds on an original conjoint survey experiment conducted in Switzerland in 2023. We follow recent sociological literature to operationalize the concept of cultural consumption empirically and test how voters respond to politicians who either claim they enjoy going to drink a beer in a pub, compared to politicians who enjoy listening to classical music with a glass of wine (Jæger and Larsen Reference Jæger and Larsen2024; Prieur and Savage Reference Prieur and Savage2013; Reeves Reference Reeves2019; Reeves and de Vries Reference Reeves and de Vries2019). Our findings show that Swiss voters are less likely to support politicians displaying cultural consumption associated with the upper classes (classical music/wine). Furthermore, while voters are not generally more likely to support politicians displaying cultural consumption associated with the working classes (drinking beer in a pub), this attribute significantly increases support among radical right voters. This effect is driven by lower-educated, lower-status radical right voters in working-class occupations.

This study contributes to the existing literature in three ways. First, our findings contribute to the growing body of research on the electoral effects of symbolic appeals. Barnes et al. (Reference Barnes, Kerevel and Saxton2023) have shown that politicians have incentives to showcase their working-class background as it increases their credibility with voters. Symbolic working-class appeals detached from objective class belonging have been discussed as a tool frequently used by populist radical right parties, including references to working-class activities (Westheuser Reference Westheuser2020). Our study shows that one of these activities, frequently mentioned – drinking beer in a pub – indeed has the assumed positive effect among radical right voters and thus contributes to similar debates about the electoral appeal of simple language and dialects (Bischof and Senninger Reference Bischof and Senninger2025; Kittel Reference Kittel2025; Ziblatt et al. Reference Ziblatt, Hilbig and Bischof2024).

Second, our study adds nuances to the literature on descriptive and symbolic representation of the working class. Literature on descriptive representation, which focuses on economic class congruence between politicians and voters, usually starts from the assumption that working-class voters across all parties prefer politicians with working-class attachments (Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2016, Reference Carnes and Lupu2023; Vivyan et al. Reference Vivyan, Wagner, Glinitzer and Eberl2020; Wüest and Pontusson Reference Wüest and Pontusson2022). Work on symbolic representation,Footnote 1 however, finds an overall positive effect of having more politicians with a working-class background on citizens’ satisfaction with politics, not just the working class (Barnes and Saxton Reference Barnes and Saxton2019). Our analysis confirms that citizens are generally favourable of working-class politicians, but we also find that stating to enjoy having a beer in a pub appeals to radical right voters only. Working-class voters from other parties, or voters in general, do not positively respond to this. This indicates that radical right voters are more responsive to politicians addressing class identities in cultural terms than other voters are.

Third, we contribute to the literature on radical right voting by showing that although negative claims against the political establishment and immigrants form the core of these parties’ political campaign (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), in-group signalling can be similarly effective. Addressing class identities not just in economic terms works among radical right voters and supports the claim that we cannot weigh economic against cultural explanations to understand radical right voting (Engler and Weisstanner Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020).

Empirical Approach

We conducted a conjoint survey experiment in Switzerland to test whether politicians’ symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption increases voter support. The survey, carried out by Bilendi between January to February 2023, includes 1,550 eligible voters representative of the German-speaking part of Switzerland.Footnote 2

The Swiss case

Switzerland is a particularly suitable case for evaluating the effect of symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption. Electoral realignment along the cultural divide already happened in the 1990s, with the populist radical right Swiss People’s Party (SVP) becoming the strongest party, forming distinct cultural identities along a new divide between SVP and Green voters (Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024; Zollinger and Traber Reference Zollinger and Traber2023). Moreover, despite the salience of cultural issues, strong class divisions persist between the left-wing camp (social democrats and greens) and the right-wing camp (centre party, liberals, and SVP) (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2010). This context allows us to test how signalling to class identities works when the cultural dimension has fully consolidated (not expecting large vote shifts due to it anymore), but in a context comparable to most European multi-party systems. For these reasons, we treat the Swiss case as a ‘most likely’ case to analyse the effect of cultural consumption.

Measuring cultural consumption

Cultural consumption is highly context-specific, and citizens of different countries and cultures vary in evaluating what they consider cultural activities higher up or lower down the social hierarchy (Jæger and Larsen Reference Jæger and Larsen2024; Reeves Reference Reeves2019). For this reason, we constrain our analysis to the German-speaking part of Switzerland and focus on class markers of cultural consumption that are associated with either working-class or upper-class activities in the German-speaking context. We follow recent sociological literature in empirically operationalizing class-specific tastes and behaviours on cuisine, arts, and music (Jæger and Larsen Reference Jæger and Larsen2024; Prieur and Savage Reference Prieur and Savage2013). Jæger and Larsen (Reference Jæger and Larsen2024) show for Denmark that people associate classical music and wine tasting with ‘highbrow’ cultural activities. Noordzij et al. (Reference Noordzij, de Koster and van der Waal2024b, p. 7, Reference Noordzij, de Koster and van der Waal2024a) have created experiments with politicians drinking beer in the pub to measure ‘affinity with low-status lifestyle preferences’. Data from the Swiss Federal Statistic Office points towards the same direction in Switzerland and shows that listening to classical music is an activity of mainly tertiary-educated people (BFS 2009). Furthermore, rather than wine, beer is traditionally the most popular and affordable alcoholic drink in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. This is different in the French-speaking part with its large vineyards, where wine has been more popular among all segments of society (see Gmel et al. Reference Gmel, Notari, Georges and Wicki2012: 15).

Correspondingly, in our conjoint experiment (described below), ‘listening to classical music with a glass of wine’ signals upper-class cultural consumption, while ‘going to drink a beer in [a] favourite pub’ (Lieblingsbeiz) signals working-class cultural consumption. The term Beiz refers to affordable, accessible places common across Switzerland, not associated with a stereotypical Swiss activity that might resonate more with voters of conservative-nationalist attitudes or rural voters. Places referred to as Beiz are popular in small villages and large cities. They also serve as a popular meeting point for political parties and their members on voting days, for socialists, greens, and right-wing parties alike (Comtesse et al. Reference Comtesse, Odermatt, Schönmann and Bürki2023; Fritzsche Reference Fritzsche2019). This illustrates that going there is not an expression of Swissness associated with right-wing ideologies. We also include a class-neutral category of cultural consumption: ‘enjoys meeting friends in his/her spare time’. This item could have a social desirability bias by indicating sociability, but serves as an additional reference point.

The conjoint experiment

The conjoint experiment presented participants with hypothetical scenarios involving two fictitious politicians competing for party leadership in the upcoming Swiss parliamentary elections on 22 October 2023. Participants received the prompt: ‘The [own party]Footnote 3 is preparing for the 2023 election campaign. Please imagine that there are new elections for the party leadership before the election. We will present several hypothetical scenarios in which two politicians stand for the election.’

We focus on party leadership of respondents’ own party to control for the parties’ overall ideology and include differences in the party leadership’s ideological positions as a more nuanced additional attribute. This allows us to measure the impact of symbolic class signalling while controlling for ideological shifts within parties, but without partisanship confounding voters’ preferences. This approach has greater external validity than asking voters about their preferences without any party label attached, and where ideology may serve as a heuristic for partisanship, nevertheless (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2025).

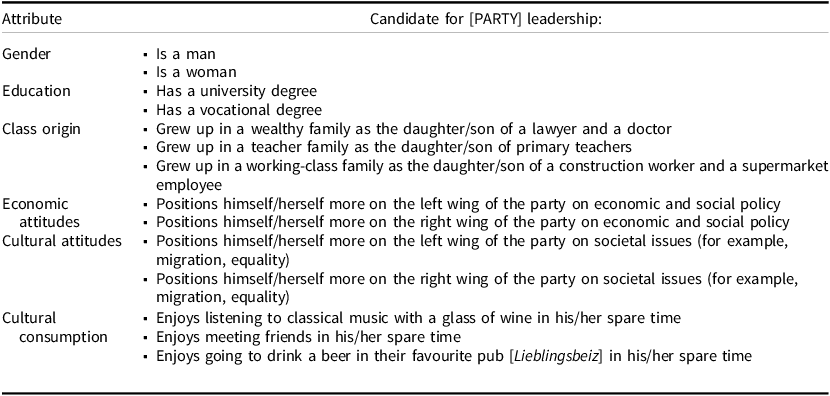

Respondents evaluated leadership candidates based on six attributes, described in Table 1: gender, education, economic attitudes, cultural attitudes, class origin, and cultural consumption – our key measurement discussed in the previous section. Attributes were fully randomised except for economic and cultural attitudes, which were kept together to reduce complexity.

Table 1. Conjoint attributes

Our outcome variables measured the likelihood of voting for the party if candidate 1 or candidate 2 became the leader and the preferred choice between the two candidates. The main results discussed below are based on the latter, but we find similar patterns using the continuous vote likelihood (see Appendix D). Respondents made five sets of choices between candidate pairs.

Preceding the conjoint experiment, the survey collected socio-demographic variables, voting behaviour in 2019, party affiliation, and an attention check. After the experiment, participants answered attitudinal questions. Appendix A provides question wordings and screenshots of the experiment.

Statistical approach

We follow Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) and use marginal means to evaluate the impact of different candidate attributes on choice probability. To calculate marginal means, we employ OLS regression with clustered standard errors. Appendix C shows that our results are robust and substantively similar to using average marginal component effects (AMCEs), the main alternative estimation method (Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).

Findings

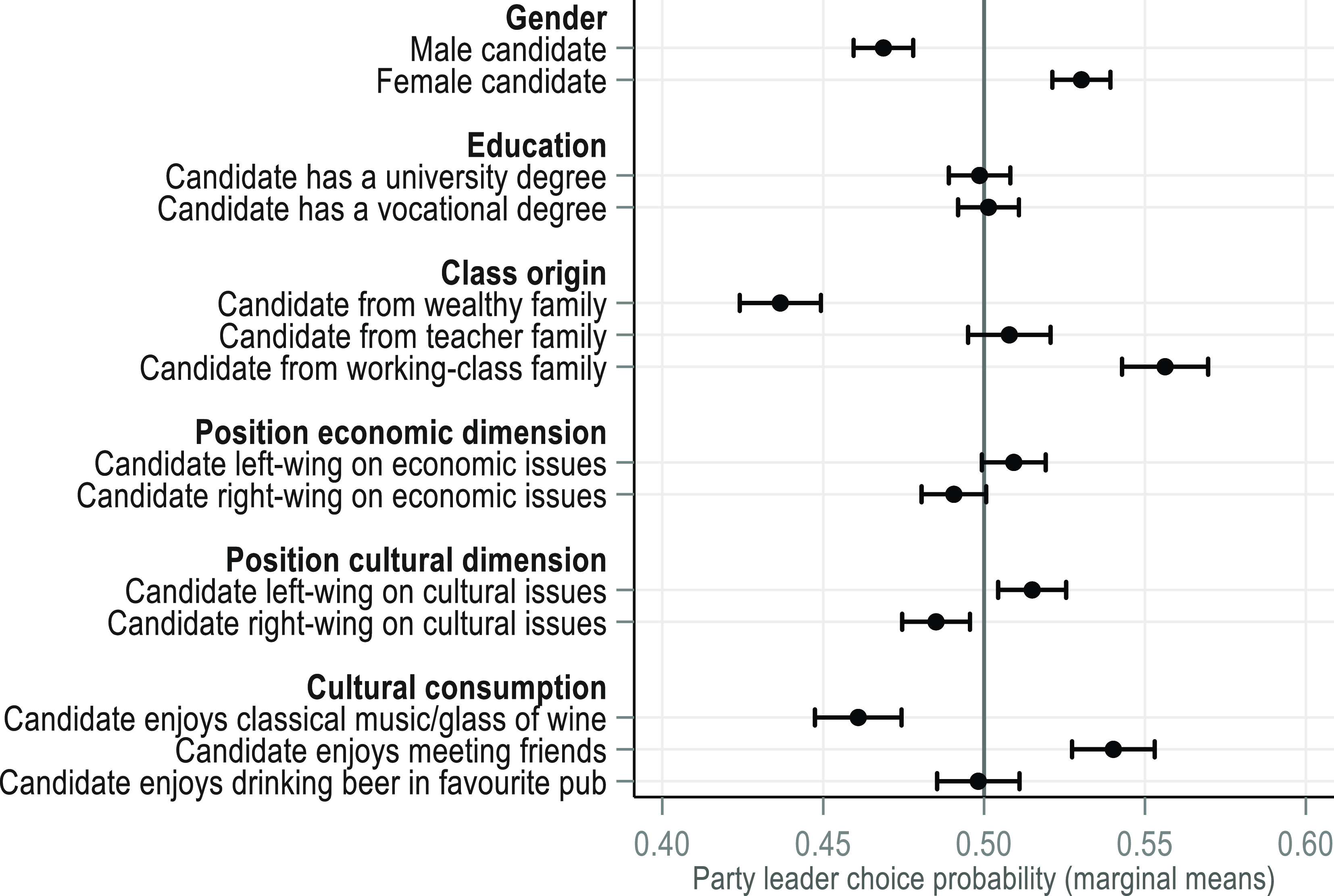

Figure 1 presents the baseline findings from our conjoint experiment. The estimates show the predicted probability of choosing a party leader with given characteristics (marginal means). We observe that respondents prefer female candidates, working-class origin candidates, and more progressive candidates within their party, while they are indifferent between university-educated candidates and those with vocational degrees. Our focus is on the effect of symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption. We find lower choice probabilities (46 per cent) for candidates enjoying classical music and wine, our measure for upper-class cultural consumption. By contrast, we find no significant effect (that is, choice probabilities indistinguishable from 50 per cent) for candidates that enjoy drinking beer in their favourite pub, our measure for working-class cultural consumption. Finally, we find higher choice probabilities (54 per cent) for candidates that enjoy meeting friends, but this effect is likely explained by sociability (see discussion on potential mechanisms below), hence we focus on the classical music/wine and beer cultural consumption attributes.

Figure 1. Effects of candidate attributes on party leader choice probability

Note: Conjoint estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Underlying regression models: Appendix B.

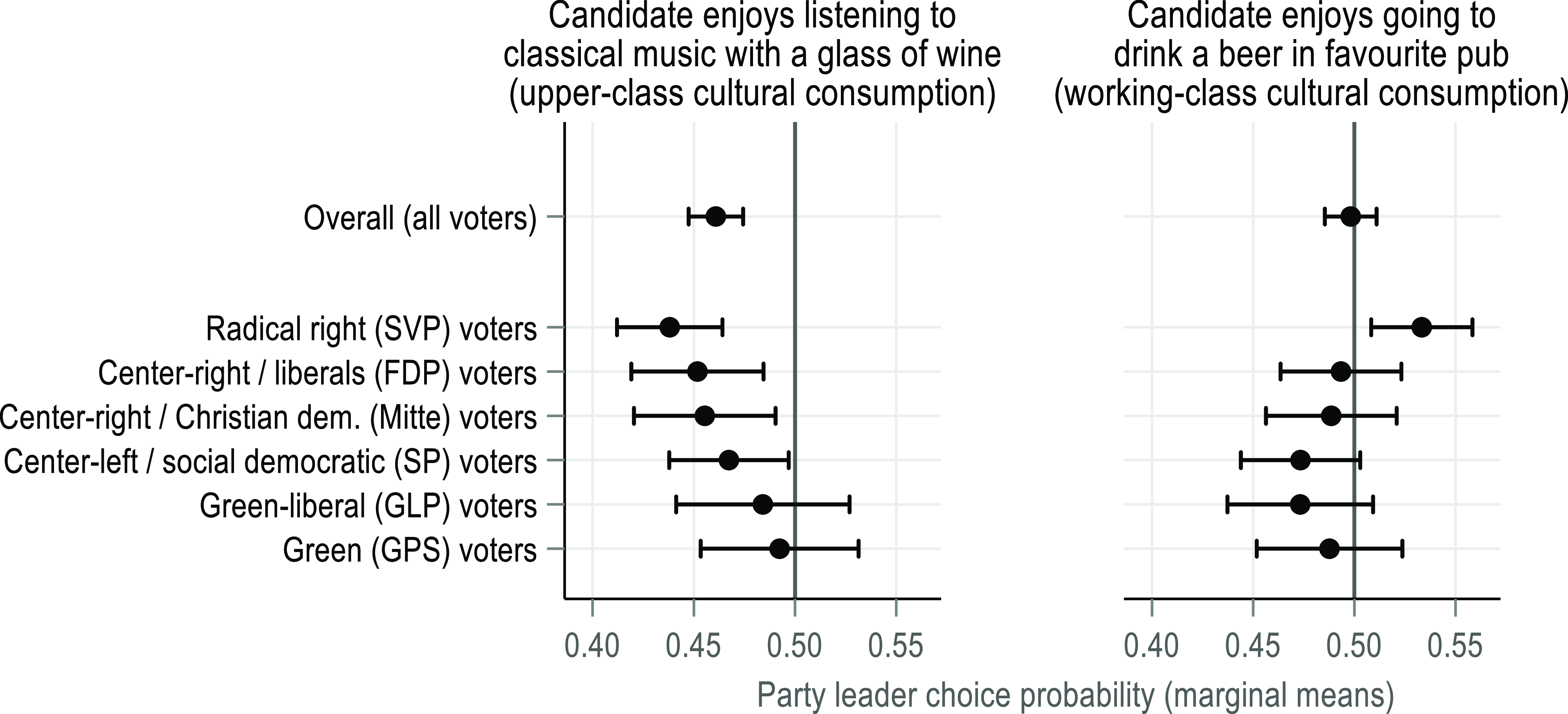

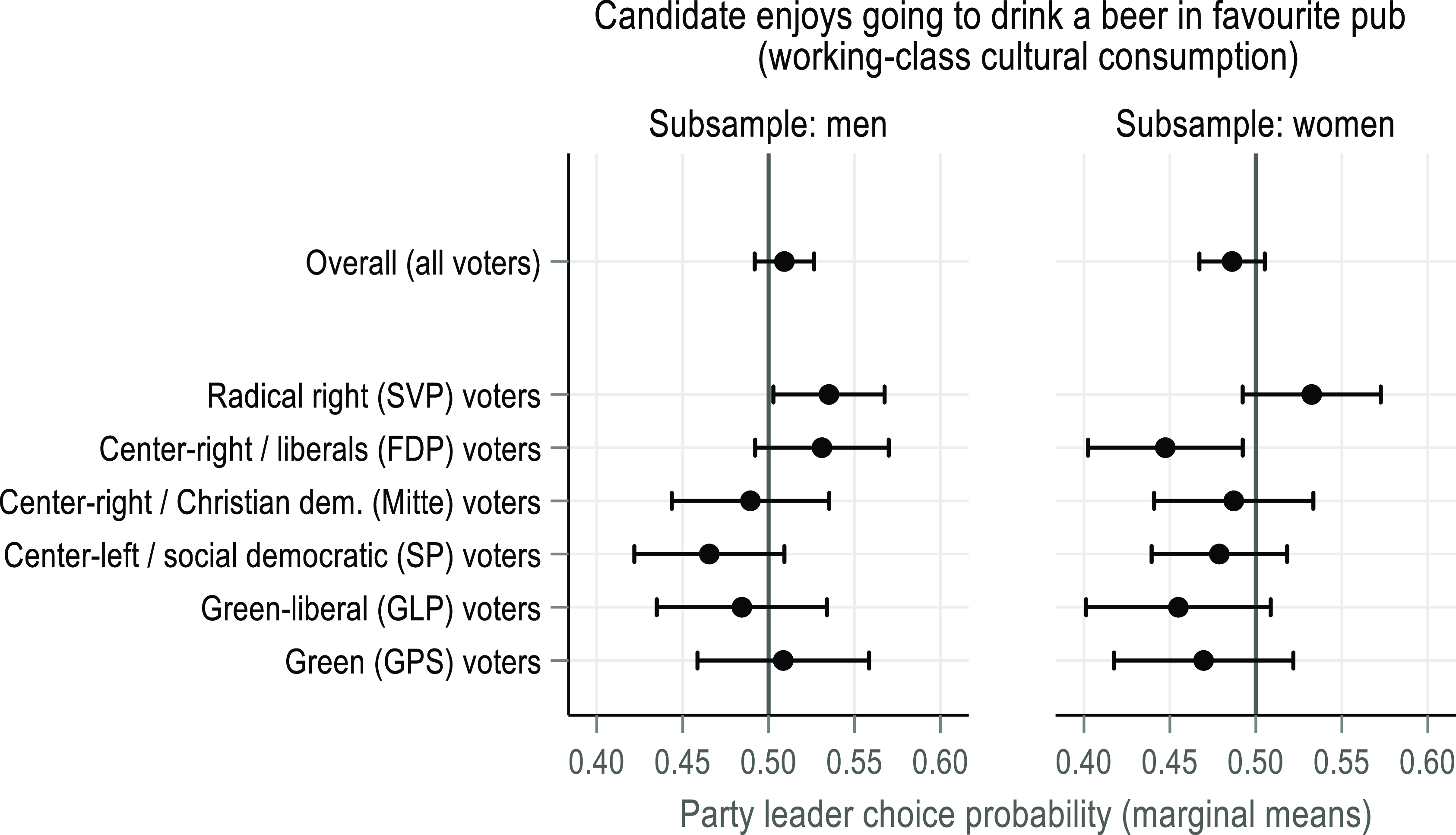

Figure 2 shows that the effect of the classical music/wine and the beer cultural consumption attributes differs substantially across political parties. Radical right (SVP) voters oppose the classical music/wine attribute (p<0.001) and are the only group positively influenced by the beer attribute (p<0.01). By contrast, mainstream centre-right (FDP, Mitte) and centre-left (SP) voters also oppose the classical music/wine attribute, but the beer attribute has no statistically significant effect and tends to be negative.Footnote 4 Finally, green party voters (GLP, GPS) do not significantly oppose the classical music/wine attribute, nor are they attracted to the beer attribute. The differences in the effect of the beer attribute between SVP voters and all other voters are statistically significant at p<0.05. This aligns with our expectation that symbolic class signalling through working-class cultural consumption, as measured with the beer drinking attribute, mainly appeals to radical right voters.

Figure 2. Effects of classical music/wine and beer attributes, by party

Note: Conjoint estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Underlying regression models: Appendix B.

Robustness tests

Appendices C and D present two crucial robustness tests of our main finding. First, our results are similar when estimating average marginal component effects (AMCEs) instead of marginal means. The AMCE of the beer attribute is statistically significant only among SVP voters (Figure C1). Moreover, the AMCE of the beer attribute among SVP voters is statistically significant in combination with any other candidate attribute; for instance, it has a positive effect among SVP voters for both male and female candidates (Figure C2). In contrast, the AMCEs are mostly not statistically significant among non-SVP voters.

Second, we find similar patterns using party vote probability (0-100 scale) as an alternative dependent variable (DV). While our main DV (party leader choice) captures internal preferences within the party, this alternative DV offers broader insights into electoral dynamics. SVP voters stand out with the highest party vote probabilities when the party leader holds the beer attribute. The beer attribute increases vote probabilities among SVP voters and decreases their likelihood of vote switching. However, we also find that SVP voters remain loyal to their party even when party leaders claim to enjoy classical music and wine. Moreover, the beer attribute has some impact on vote switching patterns of other parties’ voters too (depending on the vote switching threshold), pointing to the broader electoral relevance of working-class cultural consumption (see Appendix D).

Mechanisms

Why does the effect of working-class cultural consumption differ between the radical right and all other parties? We discuss four potential explanations: sociability, objective class affinity, the cultural interpretation of symbolic class identities, and gender stereotypes. We only find clear support for the cultural interpretation of symbolic class identities, which corresponds with the theoretical debates elaborated above.

First, although drinking beer in a pub could be interpreted as ‘being social’ compared to drinking wine alone, we find no evidence that this drives our results. Leveraging the class-neutral ‘meeting friends’ attribute as an indicator of sociability, Appendix E (Figure E6) shows that SVP voters do not differ from non-SVP voters regarding the preference for candidates who enjoy meeting friends. This attribute is popular among most parties.

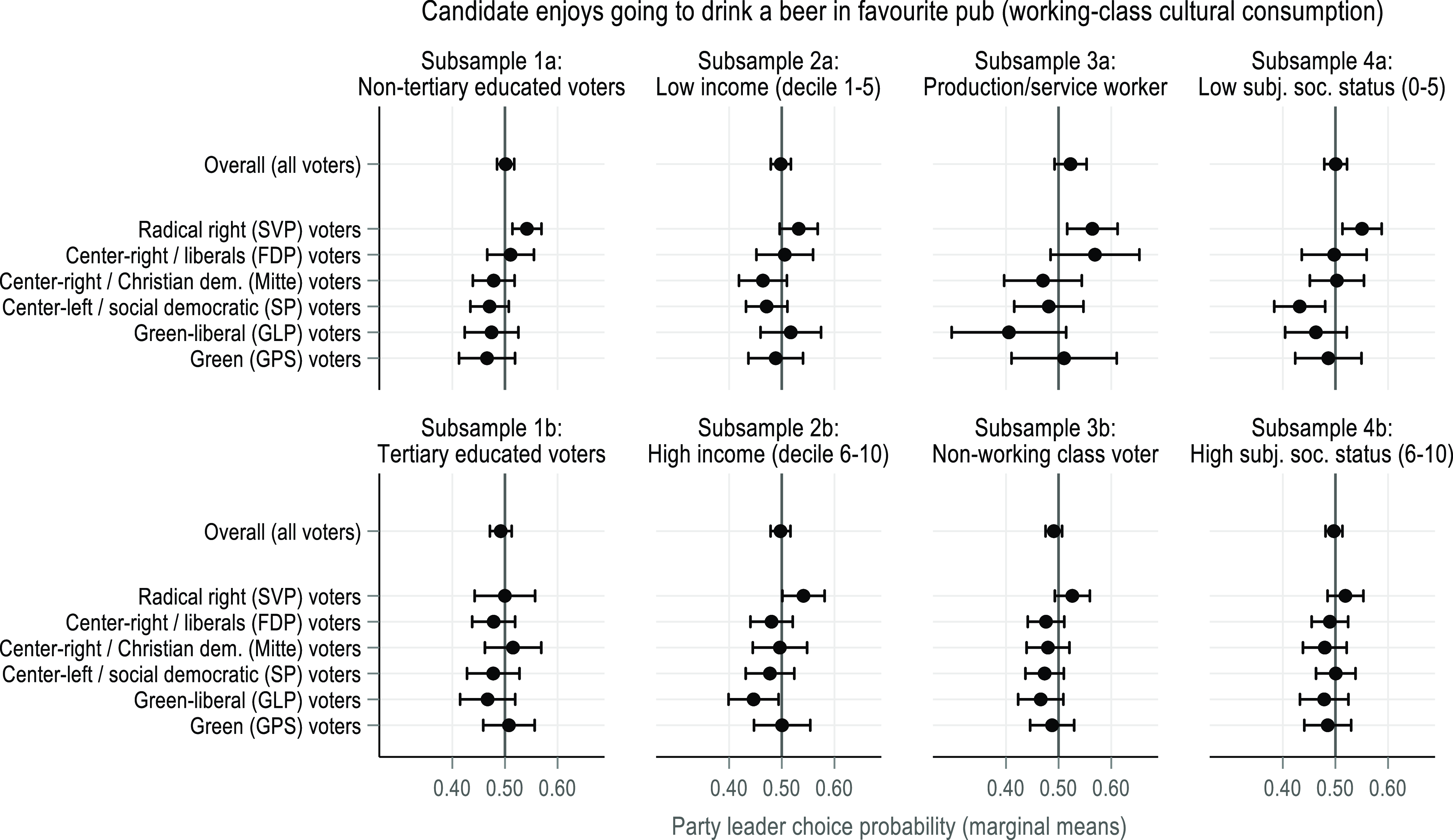

A second potential explanation is objective class affinity. Following the literature on descriptive representation, voters with lower socioeconomic status may be attracted to working-class cultural consumption due to an affinity for ‘objective’ class congruence (Vivyan et al. Reference Vivyan, Wagner, Glinitzer and Eberl2020). Since the SVP overrepresents working-class, non-tertiary-educated, low-income, and low-status voters (see Appendix G), the positive effect of working-class cultural consumption among SVP voters might therefore stem from a compositional effect. However, the subsample analyses in Figure 3 show that the beer attribute has no significant positive effect among non-SVP voters, even those with ‘congruent’ lower socioeconomic status (top row of Figure 3). This indicates that the positive effect of working-class cultural consumption cannot be explained by objective class affinity, since it does not appeal to working-class voters outside the radical right. Moreover, Appendix E (Figure E3) shows that SVP voters prefer candidates with (objective) working-class origin, but so do most of the other parties, with a lower prevalence of working-class backgrounds. Finally, we find no significant interaction between the beer attribute and class origin (Appendix F), suggesting that working-class cultural consumption appeals to SVP voters even for candidates without an actual working-class background.

Figure 3. Effects of beer attribute, by party and socioeconomic status

Note: Conjoint estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Third, we find support that a cultural interpretation of symbolic class signalling explains our results. The subsample analyses in Figure 3 show that the positive effect of working-class cultural consumption among SVP voters is driven by radical right voters with working-class occupations, vocational degrees, and low subjective social status (differences by income are less pronounced). Social class, education, and subjective social status are socioeconomic characteristics closely associated with radical right support because they are not interpreted only in economic terms but form part of culturally interpreted symbolic class identities (Engler and Weisstanner Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). Moreover, only SVP voters are attracted by non-university educated candidates, while all other parties prefer university-educated candidates or are indifferent (Appendix E, Figure E2). In line with this interpretation, supplementary analyses show that the beer attribute appeals particularly to SVP voters with stronger anti-immigration attitudes (Appendix H, Figure H1). This unique attraction of radical right voters to candidates with working-class cultural consumption or lower education cannot be explained by objective class affinity, but points to a culturally interpreted affinity based on symbolic class identities.

A final interpretation could be that the effect of working-class cultural consumption is driven by underlying gender stereotypes. Figure 4 shows that the effect of the beer attribute is statistically significant among male but not female SVP voters. However, the latter are still clearly distinct from female non-SVP voters. Moreover, the AMCE of the beer attribute among SVP voters is statistically significant for both female and male candidates (Appendix C, Figure C2). Hence, the appeal of working-class cultural consumption among radical right voters does not vary obviously by gender. That said, we lack specific data on gender-related attitudes to test this explanation in more depth, and we know that sexism and gender backlash influence radical right support (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024). Nevertheless, we believe that the strong impact of the beer attribute among radical right voters with low socioeconomic status and anti-immigration attitudes suggests a broader cultural interpretation of symbolic class identities not limited solely to gender-related dynamics.

Figure 4. Effects of beer attribute, by party and gender

Note: Conjoint estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Conclusion

In this letter, we argued that symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption (such as food, arts, and music) makes politicians appealing to voters. Despite the decline of traditional class politics in times of cultural realignment and the rise of the radical right as the main symptom of this transformation, class identities still matter. We argued that radical right parties address class in less economic terms, and thus benefit the most from symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption. Mainstream left- and right-wing parties, however, still politicize class along the traditional left-right divide, and hence benefit less from a culturally framed class signalling. We thus expected that even though symbolic class signalling in theory can attract voters with lower socioeconomic backgrounds in general, it appeals to radical right voters more than to other parties’ voters.

Our conjoint survey experiment in Switzerland confirmed that symbolic class signalling through cultural consumption matters. All parties lose support when party leadership candidates state that they enjoy listening to classical music with a glass of wine, except for the green parties. Politicians drinking beer in a pub, however, appeal only to radical right voters. Hence, even though symbolic class signalling effectively attracts voters from low socioeconomic backgrounds, this only works when they are also responsive to culturally conservative appeals. In contrast, mainstream party voters punish candidates who listen to classical music and drink wine, but neither reward nor punish candidates who drink beer.

Our study has several limitations. First, our treatment covers only a limited set of cultural consumption behaviours. Drinking beer or wine clearly has context-specific meanings, and while our analyses do not suggest that simply ‘being social’ drives our results, there may be other confounders, such as group cohesion, responsible for our results. Drinking beer in a pub might foster a sense of belonging and shared identity, which could appeal to certain voter groups beyond class distinctions (Bolet Reference Bolet2021). Future research should therefore explore a broader range of cultural consumption behaviours to better isolate the impact of symbolic class signalling on candidate choice and party support.

Second, our survey experiment focuses on party electorates and vote choices within their own party. We also analysed party vote probability as an alternative dependent variable, which confirmed that the beer attribute helps radical right parties to retain voter support and even shows some electoral potential among mainstream parties despite not being their preferred attribute. However, future research should measure vote choices across parties to explore how symbolic class signalling influences the electoral potential of mainstream parties relative to radical right parties.

Our measure of symbolic class signalling goes beyond a purely economic understanding of class and shows that what people often associate with class but is not economic per se, matters for voters. Going to the ‘Beiz’ (pub) is a moderate treatment for the Swiss context – something progressives and conservatives do alike, and that is affordable for everyone. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that the reason why it resonates more with radical right voters than other working-class voters has to do with various stereotypes that people have in mind when thinking about the working class. The working class has become more diverse in recent decades, with rising shares of women and immigrant-origin individuals in the service sector and a declining share of the traditionally male manufacturing-based working class (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Oesch Reference Oesch2013). However, when appealing to a stereotypical working-class activity such as going to the pub, we might still project to a more traditional image of the working class (white male production worker). Our analysis hinted at the stronger impact of the treatment among individuals with anti-immigration attitudes, but this did not explain the large difference between the radical right and all other parties, and the appeal of working-class cultural consumption among radical right voters also did not differ significantly by gender. Another limitation of our study is that we cannot distinguish between voters with and without immigrant origins to see whether different groups within the working class react differently to class signalling through cultural consumption and to what extent they explain our results. In future research, we thus do not just need to look at parties’ appeals to the working class and their electoral effects, but also what different parties and voters mean when referring to ‘the working class’.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary materials for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425100513

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GEG7WJ.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joshua Starbatty for excellent research assistance. We thank Matthias Dilling, Geoffrey Evans, Jessica Fortin-Rittberger, Susanne Garritzmann, Ari Ray, Mathilde van Ditmars, Christina Zuber, and participants of the PolSem Brown Bag seminar 2023 (Lucerne), ‘Inequality and Political Behaviour’ workshop 2023 (Oxford), the CES conference 2023 (Reykjavik), Comparative Politics and Political Economy Research Series (University of Konstanz), the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Political Science Association 2024 (St. Gallen), the ‘2024 Workshop: Responding to the demand? Voters’ grievances, PRR success, and mainstream party strategies (Swansea University)’, the MZES Colloquium (University of Mannheim), the research seminar of the Institute for Democracy Studies (University of Göttingen), the CEU Research Seminar (Vienna), the research colloquium at the University of Bern, and the staff seminar at the University of Geneva for valuable comments on previous versions of this paper.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University Research Priority Program “URPP Equality of Opportunity” of the University of Zurich.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

This work was approved by Aarhus University’s Research Ethics Committee/Research Ethics Committee - BSS (Institutional Review Board) in accordance with Aarhus University’s guidelines for the university’s Research Ethics Committee (IRB) and the considerations listed in the guidelines. Approval was granted on 26 October 2022 (approval number BSS-2022-099).