Energy drinks (ED) are generally defined as beverages with a high content of caffeine, sugar and other stimulant substances such as taurine, guarana, ginseng or vitamins(Reference Higgins, Tuttle and Higgins1). However, there is no general consensus on their definition. The European Commission Scientific Committee on Food defines ED as a customary commercial name for beverages that contain high levels of caffeine together with ingredients not commonly found in sodas and juices(Reference Harris and Munsell2).

The discrepancies in the definition of ED are mainly due to the variation in their composition and the lack of rigor in their labelling. In general, most brands claim to contain between 70 and 80 mg of caffeine. On the other hand, the caffeine contained in other ingredients like guarana, which may contain up to 40–80 mg per gram, might not be declared on labels because it is not mandatory(Reference Ravelo Abreu, Rubio Armendáriz and Soler Carracedo3). It should be noted that the European Food Safety Authority recommends that the maximum daily intake of caffeine should not exceed 400 mg(4).

Control of caffeine intake is critical due to its multiple adverse effects. Caffeine can cause cardiovascular problems such as arrhythmia, especially tachycardia; gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea and vomiting and neuropsychiatric effects such as psychomotor agitation, insomnia and anxiety, among others(Reference Reissig, Strain and Griffiths5). Excess ingredients such as sugar may also lead to complications like obesity or diabetes(Reference Hafekost, Mitrou and Lawrence6).

In 2021, the European Food Safety Authority estimated the prevalence of ED consumption in sixteen European countries. The results revealed that while 30 % of adults had consumed ED in the last year, the prevalence among adolescents during the same period reached 68 %(Reference Zucconi, Volpato and Adinolfi7). Young consumers often perceive these beverages as cool, a perception that is largely influenced by marketing campaigns linking ED with extreme sports(Reference Reissig, Strain and Griffiths5,Reference Gornicka, Pierzynowska and Kaniewska8–Reference O’Brien, McCoy and Rhodes15) . Majori et al.(Reference Majori, Pilati and Gazzani16) define this consumption as a social phenomenon. Concerns regarding high underage consumption have prompted regulatory actions in some countries, such as Lithuania and Latvia, which have instituted regulations governing their sale(Reference Borzan17). Similarly, Canada has required manufacturers to comply with caffeine limits, marketing restrictions and health risk warnings(Reference Wiggers, Reid and Hammond18). Other European countries such as Poland(Reference Sejmu19) and Norway(20) are also considering following the steps of Lithuania and Latvia and implementing measures to prohibit the sale of ED to minors under the age of 16.

In order to design appropriate regulatory policies, it is necessary to acknowledge the present situation of the product to be regulated. For this reason, the aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on the consumption of ED in European countries and the characterisation of the consumers.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt21). The systematic review protocol, registered with number CRD42023473014 in the PROSPERO database, outlined a comprehensive analysis of the worldwide prevalence of ED consumption.

The studies were meticulously organised by continent to streamline the management of the voluminous information and enable a comprehensive examination of country-level variations within each continent. This categorisation enhanced the analytic precision and provided a more profound comprehension of regional disparities in ED consumption. Here, we only reviewed the studies in Europe.

Original articles that fulfilled PECOS (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome and Study design) criteria (Table 1) were selected considering the following question: ‘What is the prevalence of ED consumption in Europe and the characteristics of their consumers?’.

Table 1. PECOS criteria

Search strategy

A bibliographic search was performed in July 2023 in EMBASE, MEDLINE (Ovid), Scopus and Cochrane databases and later updated in November 2024, after applying a pre-designed search strategy drawn up by three expert reviewers (ATT, NMC, MPR) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

The search strategy was developed by combining MeSH terms, emtree terms and free terms. The MeSH and emtree terms were ‘Energy drinks’, ‘Prevalence’ and ‘Epidemiology’. The free terms were ‘drink*’, ‘beverag*’, ‘Caffein*’, ‘taurin*’, ‘consumer’ and ‘consumption’. No restrictions on country, study period, study design and language were applied for the bibliographic search.

Furthermore, the bibliographic references of selected articles were reviewed to ensure the inclusion of all possible studies.

The article with the earliest date of publication complying with the inclusion criteria set was considered the first publication on ED consumption.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The review covered all studies which included prevalence data of ED consumption in any time frame, country and population, regardless of whether their main objective was the estimation of the prevalence of consumption.

Studies with the following characteristics were excluded: (a) studies that estimated the prevalence of overall caffeine consumption, without differentiating the type of beverage; (b) those that provided the combined prevalence of ED and other beverages and substances, such as alcohol, without providing individual ED outcomes; (c) those whose target population consisted exclusively of individuals with a range of medical conditions or substance dependence and (d) studies that covered more than one country without providing individual prevalences for each of them.

Moreover, studies published in languages different from Spanish, English or Portuguese, communications to conferences, letters, opinion articles, narrative reviews, systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis, simulation studies and retracted publications were excluded. Additionally, grey literature was not included because peer review was not guaranteed.

Selection of studies and extraction of data

After eliminating duplicated references, four authors screened titles and abstracts of all studies yielded by the search through a blinded peer-review process. Subsequently, the same authors reviewed the full text of studies considered potentially relevant. Discrepancies, both in eligibility and in data extraction, were discussed and settled by consensus.

The four authors manually extracted data from the selected studies in a pre-designed extraction ad hoc sheet in Microsoft Excel, which was adapted to the STROBE checklist(Reference von Elm, Altman and Egger22). Discrepancies were discussed and settled by consensus.

Studies estimating ED consumption in European countries were selected for inclusion in this manuscript. For each study, information was extracted on:

a. Study characteristics: first author, year of publication, study period, country, study design, geographical scope (European, nationwide, regional or local), and, if applicable, the name of the study or survey from which the data were derived.

b. Population characteristics: sample size, population group (school students, university students or the general population, encompassing children, adolescents or adults), sex and age group, mean age or academic degree.

c. ED consumption data: definition of ED consumption, including the frequency of consumption (regular, occasional or infrequent) or periodicity (daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, ever in lifetime), the method used to ascertain consumption (including format of the questionnaire) and the prevalence of ED consumption, alone or mixed with alcohol. Prevalence of consumption was extracted only from studies that provided frequency data on ED consumption, both alone or mixed with alcohol. Both overall prevalence and prevalence by sex were included. Prevalence percentages stratified by age group or academic year were only included if overall prevalence was not available. When longitudinal studies estimated the prevalence of use over different time periods, the most recent year was extracted. In addition, if a study reported different intensity-based consumption percentages for the same time frame, the sum of all individual percentages was used to determine the overall prevalence for the specific period. For European studies with prevalence data from multiple countries, both global and country-specific prevalence percentages were included. If a study included the prevalence of ED consumption mixed with alcohol for different timeframes, that referring to the last month was included.

d. Characterisation of the ED consumers: dependent and independent variables conferring a higher likelihood of being an ED consumer were extracted. All models adjusted were considered, including those employing various definitions of ED consumers and those exploring sex differences and changes over time.

The results were structured in five sections: ‘Characteristics of the Studies and Population’, ‘Data Collection Methods’, ‘Prevalence of ED Consumption’, ‘Characterization of ED Consumers’ and ‘Evaluation of the Quality of the Studies’.

Assessment of quality

Study quality was evaluated using an adaptation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale(Reference Stang23). The adaptation was made to better suit the nature of the methodological design of studies in our review, which were mainly cross-sectional. This adaptation allowed for a more accurate evaluation of key aspects, such as data collection methods, the definition and characterisation of ED consumption and the stratification of prevalence data, which are not fully addressed by the original scale, designed primarily for cohort and case–control studies.

Two authors screened each study separately evaluating the sample selection/strategy (representativeness of the sample, sample size and response rate between respondents and non-respondents), assessment of ED consumption (ascertainment, definition and characterisation of the ED consumption), comparability and outcome (stratification of the prevalence data on ED consumption, statistical test and assessment of potential biases/limitations) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Studies were blindly scored from 0 to 16 by each author, with the final score being reached by agreement. In case of any difference of opinion, a third author was consulted. Studies with a score ≤ 8 points were rated as poor quality, those with a score of 9–12 points as moderate quality and those with a score of ≥ 13 points as high quality.

The quality of the studies was analysed according to the range, mean and median of the score obtained with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale; and the factors which most contributed to the decrease in the score were identified.

Results

Characteristics of the studies and population

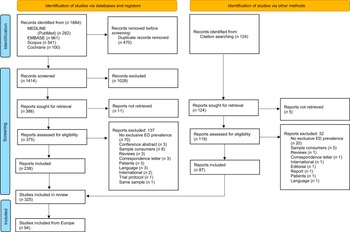

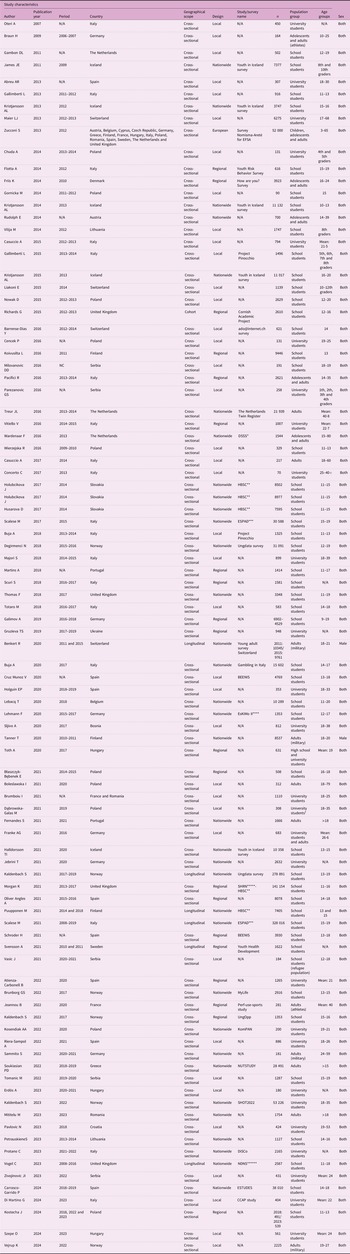

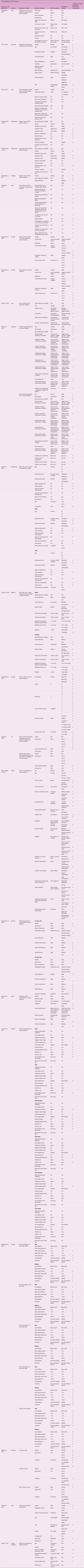

The comprehensive literature search yielded 1884 studies, of which 470 were duplicates; 1028 were excluded for not meeting the criteria and eleven were not retrieved. 375 studies from the literature search and 119 from the review of bibliographic references (citation search) from the selected studies were deemed eligible for full-text review (Figure 1). 238 studies from the literature search and eighty-seven from the citation search estimated the prevalence of ED consumption worldwide. Therefore, a total of 325 were included. Of these, ninety-four were conducted in Europe during the period 2006–2023 (Table 2). The greatest number of studies, amounting to 19(Reference Blaszczyk-Bebenek, Jagielski and Schlegel-Zawadzka24–Reference Vogel, Shaw and Strommer42), was published in 2021, indicating a notable increase in research output since the first publication in 2007. The studies spanned across twenty-seven European countries, with Italy (n 19), Poland (n 11) and Spain (n 9) emerging as the three countries with the highest volume of publications. Of the studies, the majority were conducted at the local and national levels (n 39 and 34, respectively), with one study at the European level, encompassing data from sixteen countries (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flowchart of studies selected for the systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Table 2. Study and population characteristics of the included studies (n 94)

*Dutch Sport nutrition and Supplement Study; **The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study; ***European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; ****Eating study as a KiGGS Module; *****Student Health and Wellbeing; ******National Diet and Nutrition Survey.

† Those who had contraindicated doing sport were excluded.

Eighty-eight of the studies included were cross-sectional studies and six longitudinal (Table 2). Thirty-seven studies, all in school-aged populations, specified a name of a study or survey, with some sources commonly used across multiple studies. For instance, two Italian studies utilised data from the Pinocchio Project and another two from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD). Two Spanish studies drew data from the BEENIS project. Additionally, one Finnish study and three Slovakian studies relied on data from the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) project, while all four Icelandic studies were based on data from the Youth in Iceland Survey (Table 2).

The sample size of the included studies, covering a total of 1 247 135 children, adolescents and adults, ranged from 70(Reference Concerto, Conti and Muscatello43) to 328 016(Reference Scalese, Cerrai and Biagioni31) participants. Many studies had fewer than 1000 participants (40 of 94; 42·5 %). The majority of studies (77 out of 94) focused on school-aged children (aged 9–19 years) and university students (aged 18–53 years); notably, one study focused on refugee children(Reference Vasic, Grujicic and Toskovic34). The remaining studies included adult populations, either independently or in combination with children and adolescents. Two studies exclusively involved male military participants, one conducted in Switzerland(Reference Benkert and Abel44) and the other in Finland(Reference Tanner, Harju and Pakkila45) and two focused on athletes(Reference Braun, Koehler and Geyer46,Reference Jeannou, Feuvrier and Peyre-Costa47) (Table 2).

Data collection methods

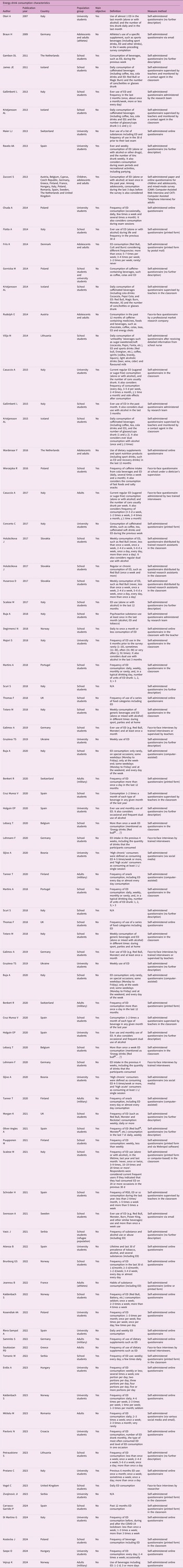

Table 3 presents the definitions and methods used in each study to ascertain the prevalence of ED consumption. Variations were observed in terms of time frame and quantity, intensity or frequency of consumption. One study did not include any specific definition of ED consumption(Reference Scuri, Petrelli and Tesauro48). Five studies addressed consumption during specific contexts such as recreational activities, special occasions, exam periods and the COVID-19 pandemic(Reference Ravelo Abreu, Rubio Armendáriz and Soler Carracedo3,Reference Fernandes, Sosa-Napolskij and Lobo26,Reference Maier, Liechti and Herzig35,Reference Chuda and Lelonek49,Reference Totaro, Avella and Giorgi50) . Thirty-four studies specified in their definitions broader categories including ED, such as common food and drinks, dietary supplements and sport nutrition products, caffeinated beverages, unhealthy drinks, psychoactive substances, snacks and fast foods. Fifteen studies focused on specific brands, mainly Red Bull and Monster, and some studies investigated ED consumption alongside other psychoactive substances, notably alcohol (n 18).

Table 3. Study characteristics of energy drink (ED) consumption

The majority of studies (86 of 94) employed self-administered questionnaires as the primary method for data collection. Sixteen studies out of the eighty-six lacked any description of the setting in which the questionnaire was completed or the format of the questionnaire itself. The classroom emerged as the most frequent setting (n 27), with some studies (n 13) noting the involvement of teachers or research assistants in data collection. The most frequent format was self-administered online (n 28), followed by printed (n 13) and email formats (n 5). Seven studies collected data via face-to-face interviews (Table 3).

Prevalence of energy drink consumption

Forty-nine of ninety-four studies aimed to estimate the prevalence of ED consumption as their primary objective (Table 3).

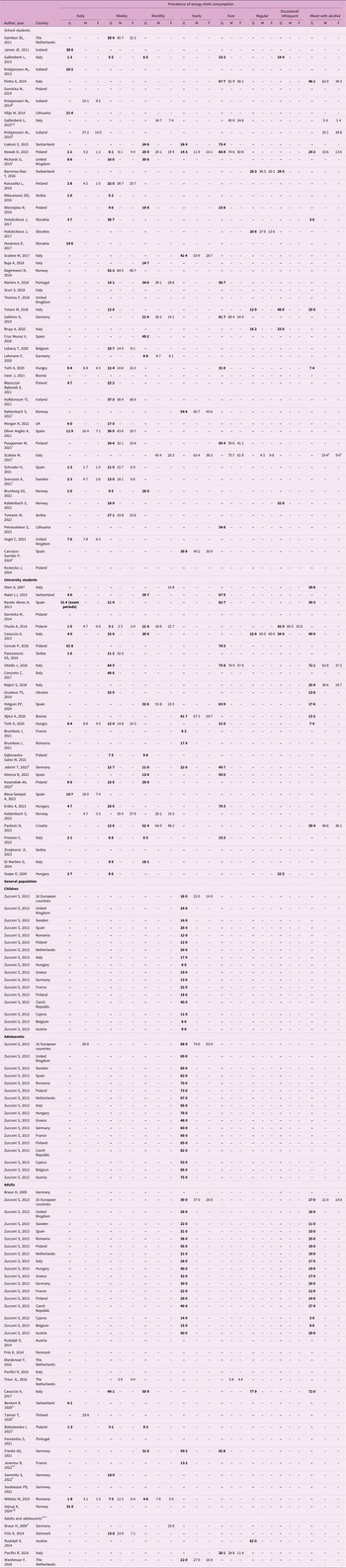

Supplemental Table 4 shows the prevalence of ED consumption by study year, population group and European country. Table 4 shows the prevalence of ED consumption in each study, grouped by population and based on the frequency of ED consumption. Fifty-one studies estimated the prevalence among school students, twenty-eight in university students and one in both groups(Reference Toth, Soos and Szovak51). The remaining eighteen studies assessed the prevalence of ED consumption in the general population, encompassing children, adolescents and/or adults.

Table 4. Prevalence of energy drink (ED) consumption in included studies (n 94) by population group

G: global; M: male; F: female.

The use of boldface is intended to highlight the overall prevalences, making key data points more visually distinct and thereby facilitating easier and quicker interpretation of the table.

† Prevalence from the most recent year.

‡ Prevalence from the last month.

§ Overall prevalence derived from the sum of the different intensity-based consumption percentages.

|| Overall prevalence derived from the sum of the different prevalences stratified by age group or academic year.

¶ Prevalence from field exercise setting (higher prevalence).

* Military population.

** Athletes.

*** This section includes studies carried out in the adult and adolescent population without differentiating between these two groups.

Fifty-four studies assessed global prevalence across different time frames. The most studied frequency was weekly (n 45), followed by daily (n 35) and monthly (n 28) (Table 4). The study by Nowak(Reference Nowak and Jasionowski52) examined the frequency of consumption in detail, whereas seven studies did not specify the frequency(Reference Gornicka, Pierzynowska and Kaniewska8,Reference Majori, Pilati and Gazzani16,Reference Fernandes, Sosa-Napolskij and Lobo26,Reference Scuri, Petrelli and Tesauro48,Reference Thomas, Thomas and Hooper53) .

The global prevalence of daily consumption varied between 0·5 % in 2022(Reference Kosendiak, Wysocki and Krysinski54) and 61·8 % in 2016(Reference Cencek, Wawryk-Gawda and Samborski55), both among Polish university students. Global prevalence of weekly consumption ranged from 3·1 % among Polish university students in 2014(Reference Chuda and Lelonek49) to 64·5 % among Italian university students in 2016(Reference Vitiello, Diolordi and Pirrone56). A single study, published in 2013(Reference Zucconi, Volpato and Adinolfi7), estimated the prevalence of yearly ED consumption globally and across sixteen European countries, encompassing children, adolescents and adults; the prevalence by country ranged from 6·0 % among Hungarian children to 85·0 % among Belgian adolescents. With regard to studies that estimate lifetime consumption, global prevalence varied from 20·1 % among Italian adolescents and adults in 2016(Reference Pacifici, Palmi and Vian57) to 83·9 % among Spanish university students in 2020(Reference Pintor Holguín, Rubio Alonso and Grille Álvarez58). A total of thirty-seven studies, irrespective of the frequency of ED consumption, stratified the prevalence by participant’s sex. In all, higher consumption was observed among males compared to females (Table 4).

Nineteen studies ascertained the prevalence of dual consumption of ED and alcohol (Table 4). The prevalence ranged from 3 % among Slovakian students in 2017(Reference Holubcikova, Kolarcik and Madarasova Geckova59) to 72·2 % among Italian adults in 2017(Reference Casuccio, Immordino and Falcone60). Interestingly, out of the nine studies that stratified the prevalence of consumption by sex, two studies(Reference Nowak and Jasionowski52,Reference Kristjansson, Mann and Sigfusdottir61) pointed out in 2015 that Icelandic and Polish school-aged girls consumed mixed ED and alcohol more frequently than boys (39·8 % v. 35·1 % and 13·6 % v. 10·6 %, respectively).

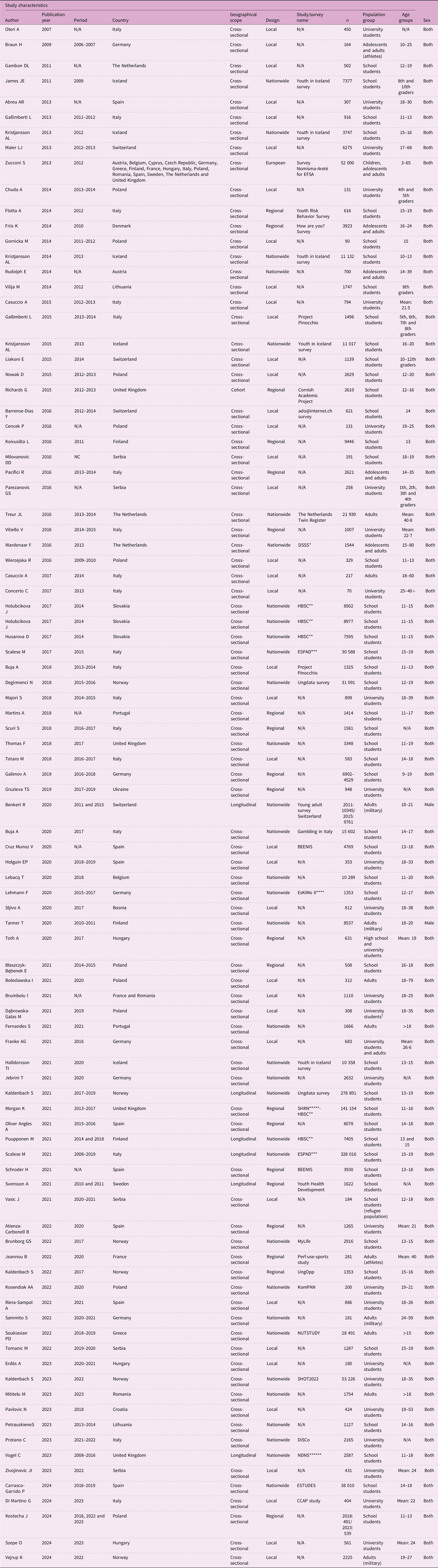

Characterisation of energy drink consumers

Table 5 shows the studies that characterised ED consumers (n 23). Fourteen studies characterised the school-age population, with weekly (n 8) and lifetime (n 3) consumption being the predominant frequencies. Italy stands out as the country with the majority of these studies (n 5). Five studies accounted for potential differences in characterisation based on participant’s sex, age or study period(Reference Puupponen, Tynjala and Tolvanen30,Reference Svensson, Warne and Gillander Gadin33,Reference Benkert and Abel44,Reference Lebacq, Desnouck and Dujeu62) . All studies collectively considered seventy-five different variables, with participant’s sex, age, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity and socio-economic-related variables being the most frequently examined. The socio-economic-related variables included aspects such as socio-economic status, household income, family affluence and structure, ethnic and migrant background, parental educational level, maternal origin, paternal and maternal occupation, place of residence and educational level. Fifty-nine variables were found to be associated with ED consumption in at least one study. Male gender, the socio-economic-related variables, tobacco and alcohol consumption were the most frequently associated variables (Table 5).

Table 5. Characterisation of energy drink (ED) consumers (n 23)

Of those characteristics assessed in more than one study, it was agreed that low academic performance(Reference Oliver Angles, Camprubi Condom and Valero Coppin29,Reference Schroder, Cruz Munoz and Urquizu Rovira32,Reference Galimov, Hanewinkel and Hansen63) , lower socio-economic status(Reference Morgan, Lowthian and Hawkins28,Reference Puupponen, Tynjala and Tolvanen30,Reference Degirmenci, Fossum and Strand64) , having sexual relationships(Reference Oliver Angles, Camprubi Condom and Valero Coppin29,Reference Flotta, Mico and Nobile65) , having accidents(Reference Oliver Angles, Camprubi Condom and Valero Coppin29,Reference Scalese, Denoth and Siciliano66) and going out with friends(Reference Oliver Angles, Camprubi Condom and Valero Coppin29,Reference Scalese, Denoth and Siciliano66) were associated with greater ED consumption in students. Tranquilizers/anxiolytics were associated with greater ED consumption when valued both in students(Reference Scalese, Denoth and Siciliano66) and the military(Reference Benkert and Abel44).

Evaluation of the quality of the studies

When assessing quality, seventy-six studies were deemed to be of low quality, while the remaining eighteen were rated as moderate (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3). The mean score was 6·43 and median score was 7. Several factors contributed to these ratings, including inadequate representation of the target population, lack of justification for sample size and low response rates. The lack of comprehensive specifications for self-administered questionnaires and inadequate supervision of interviewers also contributed to these ratings. It is noteworthy that a significant proportion of studies (n 70) only provided a descriptive analysis. Scores varied between 0 and 12, with Scuri et al.(Reference Scuri, Petrelli and Tesauro48) having the lowest score and both Zucconi et al.(Reference Zucconi, Volpato and Adinolfi7) and Holubcikova et al.(Reference Holubcikova, Kolarcik and Madarasova Geckova67) having the highest. Authors of the studies with lower scores reported lack of representativeness and differences in the method of administration of the questionnaire as the main methodological limitations; while studies with higher scores reported as limitations the cross-sectional design, the self-administration of the questionnaire and the possible influence on the results of assessing multiple comparisons.

Discussion

This study represents the first review to analyse ED consumption prevalence across twenty-seven European countries over a 17-year period. In addition to providing global, sex-stratified and frequency-stratified prevalence data, the analysis specifically considers the definitions of consumption provided by the selected studies, all possible consumption patterns and the detailed characterisation of consumers. The most studied frequency was weekly consumption, and the most studied population was school students. In studies that tracked ED consumption over time, an increase in prevalence was observed. It was not possible to estimate an overall value for the prevalence of consumption due to the great variability in its assessment. Characteristics most related to consumption were low socio-economic status, alcohol and tobacco consumption, physical activity, age and sex.

Prevalence of consumption

The assessment of temporal trends in ED consumption prevalence and differences in ED consumption by year and country was not possible due to the significant variability among studies. This diversity encompasses differences in study design, study populations, measurement methods and definitions of consumption. The populations under study have different demographic and socio-economic characteristics that condition their consumption. In turn, the measurement methods varied from brief questionnaires, through an in-depth battery of questions, face-to-face interviews to online surveys. The studies included have different approaches to consumption, and their definition relies on the establishment of variable time frames of evocation, from daily to lifetime, and a wide variability in the characterisation of frequency and/or intensity. Some studies did not even evoke recall to a specific time frame and used approximations of frequency and intensity based on imprecise aspects such as occasional or regular consumption. These differences prevent the comparison of ED prevalence estimations.

The eight studies that assessed trends in ED consumption identified an increasing trend, with the study by Scalese et al.(Reference Scalese, Cerrai and Biagioni31) being the one that covered the longest period, from 2008 to 2019. Data derived from independent studies developed in the same population are difficult to compare, mainly due to changes in the methodology or the definition of consumption.

In studies that use the same methodology to estimate prevalence in different population groups, prevalence varies. An example of this is the study by Zucconi et al.(Reference Zucconi, Volpato and Adinolfi7), a study of the European population performed in 2012 that estimated the prevalence of ED consumption in children, adolescents and adults. The prevalence varied between these three groups, with adolescents having higher consumption. This study(Reference Zucconi, Volpato and Adinolfi7) shows variations between countries. For example, the Czech Republic is one of the countries with the highest prevalence of consumption for all age groups, and Cyprus is one of the countries with the lowest prevalence. The individual studies identified endorse these results, with the eastern European countries showing higher prevalence. This is consistent with studies that relate poor health status in these populations to lack of health and behavioural information, greater belief in uncontrollable influences and lower emotional well-being, which are associated with unhealthy lifestyles(Reference Steptoe and Wardle68). In relation to Cyprus, there are no other published studies with prevalence estimations.

High variability of the prevalence of ED consumption was also found in another study performed by Aonso-Diego et al.(Reference Aonso-Diego, Krotter and Garcia-Perez69) about worldwide ED consumption. This study presented their meta-analysis results, even though they were not conclusive due to high heterogeneity.

The disparity in prevalence rates is such that even within the same population group, country and year, the prevalence differs significantly. For example, in 2012 in Italy, Gallimberti et al.(Reference Gallimberti, Buja and Chindamo70) estimated that 33·3 % of school students had ever consumed ED, while Flotta et al.(Reference Flotta, Mico and Nobile65) estimated a prevalence of 67·7 % for the same frequency of consumption. To date, the impact of the wording of the questions ascertaining prevalence on ED consumption has not been evaluated. However, it is a crucial factor to consider, as subtle differences in how questions are phrased can potentially influence respondents’ answers and subsequently affect prevalence estimates.

High variability in the study results may be due to questionnaire characteristics and their administration, especially inadequate supervision of interviewers. Different methods to ascertain prevalence have different biases that could result in implications for the validity of the research, and for the evidence used for public policy making(Reference Bowling71). In addition, inadequate representation of the target population, lack of justification for sample size and low response rates may also have introduced selection and non-response bias.

In general, most European countries do not have a clear picture of the full scenario of the consumption in their population. As mentioned, most studies focused on school and university students. Furthermore, most countries have few studies conducted to assess ED consumption prevalence. These studies often do not follow the same methodology, so they are not useful for describing the evolution of consumption.

Characteristics of consumers

Most of the studies that assessed sex identified that being male increased the probability of ED consumption. Many explanations were postulated to describe this association. The most widely accepted is that it is related to the marketing campaigns that associate ED with extreme sports and physical, sexual and academic performance aimed at men(Reference Reissig, Strain and Griffiths5,Reference Friis, Lyng and Lasgaard9–Reference O’Brien, McCoy and Rhodes15) . This is also an explanation used to associate higher ED consumption with enhanced physical activity. Prevalence in athletes should stand out due to marketing campaigns directed at them and the misinformation that these drinks are good for those who practice sports(Reference Finnegan11–Reference Carvajal-Sancho and Moncada-Jiménez13). Once again, the supposed higher prevalence of consumption among athletes could not be verified due to a lack of consistency in methodologies.

Another possible explanation is the difference in the motive for consumption. According to Branco et al., females consume out of curiosity(Reference Branco, Flor-de-Lima and Ferreira72). On the other hand, some studies link higher male consumption with higher screen time(Reference Kaldenbach, Strand and Solvik27,Reference Puupponen, Tynjala and Tolvanen30,Reference Lebacq, Desnouck and Dujeu62,Reference Degirmenci, Fossum and Strand64) and gaming(Reference Larson, DeWolfe and Story73). This is consistent with the results obtained by studies which associated ED consumption with marketing campaigns and social media, specifically Twitch(Reference Ayoub, Pritchard and Bagnato74–Reference Buchanan, Yeatman and Kelly76). In general, male sex is related to unhealthier lifestyles(Reference Courtenay77). The higher ED consumption was also related to traditional masculinity ideology, hypermasculinity and jock identity(Reference Miller14,Reference Wimer and Levant78) . It can be reasonably inferred that, regardless of which of the various postulated explanations are considered for the higher consumption of ED in men, they are all related to gender aspects that the industry has been able to exploit. The concept of masculinity has long been regarded as a potential risk factor for men’s health behaviours, given the assumption that it may encourage engagement in risky practices. Extreme sports, enhancement of physical and sexual performance and gaming are all practices historically associated with the concept of masculinity(Reference Wimer and Levant78). The industry, recognising this as an opportunity, targeted this group by leveraging gender-related issues. For example, brands designed specific packaging for these beverages exclusively for men(Reference Lebacq, Desnouck and Dujeu62). In this way, their marketing campaigns became more focused on targeting the aforementioned characteristics.

It is worth noting that Kaldenbach et al.(Reference Kaldenbach, Strand and Solvik27) found that, in students, although consumption was still higher in males, ED use in females was increasing. Among those who found an association with sex, the studies that did not find greater consumption in males were anecdotal(Reference Kaldenbach, Strand and Solvik27,Reference Gallimberti, Buja and Chindamo70) .

Higher age was associated with greater consumption in school students(Reference Oliver Angles, Camprubi Condom and Valero Coppin29,Reference Galimov, Hanewinkel and Hansen63,Reference Holubcikova, Kolarcik and Madarasova Geckova67) , while younger age was associated with greater consumption in university students(Reference Friis, Lyng and Lasgaard9,Reference Majori, Pilati and Gazzani16) . Those studies that assessed the age of first consumption estimated that most people begin before age 13(Reference Flotta, Mico and Nobile65,Reference Scalese, Denoth and Siciliano66) . It is important to note that the age at which adults first consumed ED is directly related to the introduction of these drinks to the European market. Since ED were introduced in the late 1980s, adults’ first consumption occurred later compared to the first consumption in teenagers today(Reference Reissig, Strain and Griffiths5). The age of first consumption being at such a young age is worrying, especially because the adverse effects are greater in children. The risk of intoxication in children is higher due to the fact that they are still growing and their lack of pharmacological tolerance(Reference Goldman79). Some studies like Chuda et al.(Reference Chuda and Lelonek49) and Casuccio et al.(Reference Casuccio, Immordino and Falcone60) investigated, along with the prevalence of consumption, the adverse effects suffered. In both studies, more than 20 % of those who consumed ED suffered disorders related to these beverages. Casuccio et al.(Reference Casuccio, Immordino and Falcone60) associated a greater probability of suffering these effects with being female.

Some studies have stated that knowing about the effects of ED may decrease their consumption(Reference Casuccio, Immordino and Falcone60,Reference Wierzejska, Wolnicka and Jarosz80) . Most people have a low perception of the risk of ED(Reference Pacifici, Palmi and Vian57), with this perception being lower in men(Reference Parezanović and Prkosovački81). This low perception of risk makes ED a gateway for other drugs. This theory suggests that caffeine may lead to the use of other legal drugs, including alcohol and nicotine(Reference Reissig, Strain and Griffiths5,Reference Barrense-Dias, Berchtold and Akre10,Reference James, Kristjansson and Sigfusdottir82) , which would explain the association of a higher consumption of ED with both alcohol and tobacco.

It is widely observed that health education helps reduce addictive behaviours and improve global health(Reference Rizvi83). On the other hand, raising public awareness is also important to design policies that protect the population. For example, Poland, which is one of the countries with the highest number of studies carried out, prohibited sales to minors under 16 years of age in 2023(Reference Sejmu19). Other countries such as Latvia(84) have also taken this measure and, in addition, this country has established advertising restrictions and higher taxes for ED. Other measures applied to ED are maximum caffeine limits, as they have done, for example, in Denmark(85). In the European Union, it is mandatory that ED display the following warning on the label: ‘High caffeine content. Not recommended for children or pregnant or breast-feeding women’(86). Given the high consumption in European countries and the lack of regulatory measures in the majority of countries, legislative measures should be tightened to protect the most vulnerable populations.

Regarding the association of ED consumption with socio-economic-related variables, numerous previous studies have related lower socio-economic status with unhealthy lifestyles and poor health outcomes(Reference Foster, Polz and Gill87). There is an even greater association of ED consumption with obesity(Reference Bann, Johnson and Li88) than with unhealthy and poor health outcomes due to its high sugar content, in addition to the association with lower socio-economic status.

Some discrepancies in consumer characteristics between studies could be due to the difference in the frequency of consumption with which they are associated. For example, high educational level is associated with lifetime use of ED(Reference Degirmenci, Fossum and Strand64), while a low educational level is associated with a higher frequency of consumption (weekly(Reference Friis, Lyng and Lasgaard9) or daily(Reference Benkert and Abel44)).

Limitations and strengths of the study

This review has some limitations. High variability in definition and frequency of consumption prevented any conclusions about the true prevalence of ED consumption in the populations. After performing a meta-regression including those studies that estimated daily ED consumption (data not shown), heterogeneity was estimated at 100 %. This value made it impossible to obtain reliable meta-analysed prevalences. Five studies identified in the review were not described because they did not provide information about geographical location. In addition, some prevalences were not taken into account because of the lack of frequency data. Self-reported questionnaires are a valid method to obtain information about risk factors; however, interviewer-conducted questionnaires (face-to-face or Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI)) improve data quality. In this review, most of the studies were rated as low quality, with the method of obtaining information being one of the most challenging factors. Also, not all European countries had studies that estimated the prevalence of ED consumption.

This review also has strengths. The search strategy was not limited by country. Therefore, as a first step, all studies conducted worldwide were identified, and those focusing on European countries were selected in a subsequent step. Moreover, the search was very exhaustive. We performed a bibliographical search in four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus and Cochrane), in contrast to the two databases of a previous study with similar characteristics (Aonso-Diego et al.)(Reference Aonso-Diego, Krotter and Garcia-Perez69). In addition, all references to the included studies were thoroughly reviewed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were more detailed than Aonso-Diego et al. including special populations, the amount of data collected and the inclusion of the characterisation of consumers. This is the first study to review the characterisation of ED consumers. Data extraction was done through peers.

Studies that estimated the prevalence of ED consumption are highly different, even for the same frequency, population and country, and have low quality, exposing flaws in their methodology. The most studied frequency is weekly consumption, and the most studied population is students. Those who assessed consumption over time found an increase in ED consumption. Those who characterised consumers varied in the characteristics ascertained, being socio-economic-related variables, alcohol consumption, physical activity, tobacco use, age and sex the most studied. Higher consumption is related to older school students and younger university students, lower socio-economic status and substance use such as tobacco and alcohol. Higher consumption is also related to males who, with athletes, are the main target of marketing campaigns.

Given the health problems that have been related to ED consumption, regulation of these beverages is essential, especially in youth. Similar regulations to those for high-fat products or their prohibition of their sale to minors could be effective measures to prevent consumption by young people, who are the most affected population.

Ethics of human subject participation

No ethical approval was needed for this study, as it is a systematic review.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980025100463

Authorship

A.T. participated in the methodology, extraction and analysis of results, writing, review and editing of the manuscript. N.M. extracted and analysed results, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.P-R. acquired the funds and participated in the methodology, extraction and analysis of results and review and editing of the manuscript. G.G. participated in the methodology, extraction and analysis of results and review and editing of the manuscript. L.V-L., A.M-M., C.G-T., J.R-B., C.C-P. and M.M-G. participated in the extraction and analysis of results and review and editing of the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a project of the National Plan on Drugs (code 2022I006).

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of Interest.