1. Introduction

Fluvial systems undergo systematic changes in their hydrodynamic response due to ice-jams, logjams at racks and debris accumulation at waste-collection devices (to list a few) as shown in figure 1. In such cases, accumulation of floating materials can induce a transition from a free-surface flow condition to closed-channel-like flow, resulting in complex flow behaviour such as Kelvin–Helmholtz instability and flow separation that depends on the roughness characteristics of the debris at the free surface (Fang, Tachie & Dow Reference Fang, Tachie and Dow2022). Such a change in the boundary condition at the top boundary significantly alters the hydrodynamic response in both the upstream and downstream reaches of the flow domain (Saito & Pullin Reference Saito and Pullin2014; Ismail, Zaki & Durbin Reference Ismail, Zaki and Durbin2018). Specifically, in the vicinity of the transition, the flow encounters significant changes in the mean velocity profile, shear stress and acceleration that can lead to increased turbulent transport, erosion at the bottom boundary and increased instability of the accumulation layer. As a result, understanding the physics of such a flow transition due to the accumulation layer can provide crucial insights to accurately predict its stability and better design hydraulic structures that can efficiently capture floating debris.

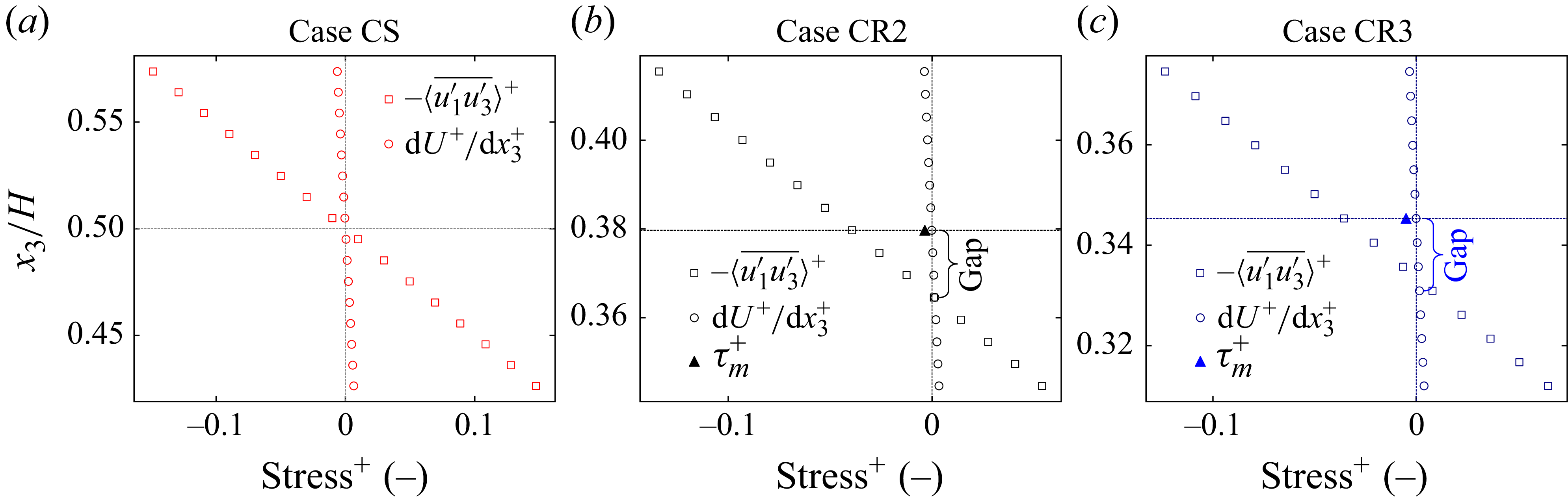

Focusing on the formation of a layer of floating material, called a carpet, its life cycle can be divided into the following stages: (i) initiation of accumulation due to the presence of hydraulic structures, (ii) progression due to incoming debris, (iii) stabilisation of the carpet and (iv) mechanical breakup or instability due to unbalanced forces. Depending on the type of debris transported by the incoming flow, carpet formation may consist of one or more layers over the depth of the channel (Shen Reference Shen2010; Schalko et al. Reference Schalko, Schmocker, Weitbrecht and Boes2018; Yan Toe et al. Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). Additionally, surface roughness characteristics of the carpet can differ greatly from those of the channel bed, leading to an asymmetric shear stress distribution as sketched in the downstream reach of the carpet in figure 1. This is typically observed in ice-jams and debris accumulation in rivers (Tatinclaux & Gogus Reference Tatinclaux and Gogus1983; Jueyi et al. Reference Jueyi, Jun, Yun and Faye2010; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Ji, Chen, Liu, Xue and Li2025). Moreover, river morphology is greatly influenced by the surface roughness of ice cover, implying that a larger ratio of ice-cover roughness to bed roughness enhances riverbed erosion (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Ji, Chen, Liu, Xue and Li2025). Moreover, there is still a debate as to whether the location of maximum velocity coincides with the location of zero shear stress in asymmetric channel flows. Hanjalić & Launder (Reference Hanjalić and Launder1972), Tatinclaux & Gogus (Reference Tatinclaux and Gogus1983) and Parthasarathy & Muste (Reference Parthasarathy and Muste1994) confirmed through experimental data that the two locations are not identical. In contrast, Shen & Harden (Reference Shen and Harden1978), Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Shan, Xu, Bai and Zhang2017) and Huai et al. (Reference Huai, Chen, Yang, Li and Wang2024) assumed these locations to coincide in their analyses, leading to the development of two distinct schools of thought. Thus, the momentum flux across the point of zero mean strain (

![]() $\partial \overline {u}_1/\partial x_3=0$

; see figure 1) still remains poorly understood for such a hydraulic system. Therefore, the asymmetry in wall roughness conditions imposes further challenges in correctly estimating the friction coefficients of the boundaries of such hydraulic systems, which are also susceptible to destabilising hydrodynamic forces (Hanjalić & Launder Reference Hanjalić and Launder1972; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Shan, Xu, Bai and Zhang2017; Yan Toe et al. Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025).

$\partial \overline {u}_1/\partial x_3=0$

; see figure 1) still remains poorly understood for such a hydraulic system. Therefore, the asymmetry in wall roughness conditions imposes further challenges in correctly estimating the friction coefficients of the boundaries of such hydraulic systems, which are also susceptible to destabilising hydrodynamic forces (Hanjalić & Launder Reference Hanjalić and Launder1972; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Shan, Xu, Bai and Zhang2017; Yan Toe et al. Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025).

As for the stability of the carpet, the hydrodynamic forces acting on the debris and interparticle forces determine the threshold mobility, and consequently the overall stability of the carpet. For plastic particles, the hydrodynamic forces affect substantially the global stability of the carpet due to a lack of interparticle cohesion, thus making them susceptible to various instability mechanisms as detailed in Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). For the ice carpets often observed in ice-jams, Beltaos (Reference Beltaos1983), Zufelt & Ettema (Reference Zufelt and Ettema2000) and Shen, Liu & Chen (Reference Shen, Liu and Chen2001) developed mathematical models to predict the carpet thickness under the static and dynamic flow conditions, assuming a continuum model for ice. Differently from the continuum assumption, Jueyi et al. (Reference Jueyi, Jun, Yun and Faye2010) experimentally investigated incipient motion of individual ice particles under cover and provided a stability criterion, similar to the Shields criterion used in sediment transport. Unlike ice-jams, plastic debris does not interact thermally or through mass transfer (i.e. ice melting), but primarily through hydrodynamic interactions with the carrier phase (i.e. water). Therefore, mechanical properties of the particles and flow conditions are mainly considered in the stability of plastic debris accumulation. In addition to the particle transport at the leading edge of the carpet (called erosion), particles inside the carpet can be squeezed out vertically due to the cumulative compressive force along the carpet (called squeezing), which is similar to the buckling phenomenon observed by Tordesillas & Muthuswamy (Reference Tordesillas and Muthuswamy2009) in force chains. To that end, Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025) developed and validated analytical formulae of these two instability modes, based on the mean flow velocity, particle diameter and particle density in an idealised single-layer carpet of mono-dispersed spherical plastic particles.

Figure 1. Flow transitions from open channel to closed channel. (a) Ice-jam in a river (photo: Bryan Hopkins). (b) Plastic waste accumulation upstream of a waste-collection device (photo: The Ocean Cleanup). (c) Debris jam (Copyright Albert Bridge (image reused under CC Attribution-Sharealike)). (d) Schematic of the flow transition from an open channel to a closed channel (not to scale), based on Yan Toe, Uijttewaal & Wüthrich (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025).

For the squeezing instability, a proper estimate of the cumulative shear stress is required to estimate the destabilising force acting on a particle. Since the flow transitions from an open channel flow to a closed channel with varying hydraulic roughness, estimation of shear stress is non-trivial, especially in the transition region. On this front, Li et al. (Reference Li, De Silva, Rouhi, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2019) and Rouhi, Chung & Hutchins (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) studied a turbulent boundary layer with roughness transition, and Van Buren et al. (Reference Van Buren, Floryan, Ding, Hellström and Smits2020) studied a turbulent pipe flow with a similar transition, proving that adjustment of turbulent stresses requires a longer downstream fetch than the development length required for the mean flow recovery.

Although there is a substantial literature discussing the boundary-layer development subject to a rough–smooth transition (Antonia & Luxton Reference Antonia and Luxton1971; Van Buren et al. Reference Van Buren, Floryan, Ding, Hellström and Smits2020), the hydrodynamics subject to free slip (open channel) to no slip (closed channel) at the top boundary has not been extensively explored. This is particularly interesting as the boundary layers at the smooth bottom and the rough top interact in the downstream fetch of the carpet, leading to a peculiar flow response in the vicinity of the transition. Adding to the complexity, different roughnesses at the top and bottom boundaries further complicate the momentum mixing and consequently it is more challenging to estimate the friction coefficients. These hydrodynamic interactions hinder the prediction of particle instability, irrespective of the material properties of the particle, i.e. sediment at the riverbed, or plastic particles at the floating carpet. Consequently, in this work, we aim to address the hydrodynamics of an idealised open-to-closed channel transition (figure 1), and its implications for the stability of mono-dispersed spherical particles inside a floating carpet.

To this end, three research questions are formulated as follows:

-

(i) How do the shear stresses and the friction coefficients develop along the bottom and top surfaces beyond the carpet transition?

-

(ii) What changes in the mean flow are observed near the transition?

-

(iii) What are the implications for erosion processes at the bottom boundary and particle instability of debris accumulation?

By better understanding the boundary-layer development at the transition, we aim to further improve the analytical formulations for particle instability, and subsequently better design waste-collection devices and improve river sediment management. It should be noted that the present study considers only mono-dispersed spherical particles as roughness elements, which differ from realistic debris that is more complex in composition, size and shape. For example, plastic waste with cylindrical or foil-like shapes is often found mixed with organic materials, complicating the characterisation of surface roughness. Similarly, large wood accumulations differ in size and shape from spherical elements, with their random orientations leading to a complex porosity within the accumulation layer. Therefore, the flow properties and streamlines, particularly the turbulent stresses near and within the accumulation layer, may differ between the simulation results and realistic configurations. Nevertheless, the present direct numerical simulation (DNS) study is expected to provide valuable insight about mean flow development and Reynolds stress profiles below a generic carpet of debris, waste or ice, and should serve as a baseline for future studies that would address the complex factors described above.

In the following sections, we first present the computational method and various flow configurations to answer the above-mentioned research questions. This is followed by a detailed discussion of the various hydrodynamic parameters of interest. Finally, we present concluding remarks and outline future work to support our analytical model.

2. Methods

The flow configurations investigated in this work are addressed using DNS of the Navier–Stokes equations, coupled with a volume penalisation method (Fadlun et al. Reference Fadlun, Verzicco, Orlandi and Mohd-Yusof2000) to represent a rough carpet layer in the computational domain.

2.1. Governing equations and numerical methods

The differential forms of the incompressible Navier–Stokes momentum and mass conservation equations are considered in this work, given by

where

![]() $t$

is time,

$t$

is time,

![]() $x_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the coordinate vector,

$x_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the coordinate vector,

![]() $u_i$

are the velocity components,

$u_i$

are the velocity components,

![]() $p$

is the pressure,

$p$

is the pressure,

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

![]() $\rho$

is the fluid density,

$\rho$

is the fluid density,

![]() $F_i$

is the penalisation forcing term, added to the momentum transport equation to enforce the no-slip/no-penetration boundary condition on a particle’s boundary, and

$F_i$

is the penalisation forcing term, added to the momentum transport equation to enforce the no-slip/no-penetration boundary condition on a particle’s boundary, and

![]() $\varPi$

is the driving force term used for periodic flow simulations. Kronecker delta

$\varPi$

is the driving force term used for periodic flow simulations. Kronecker delta

![]() $\delta _{i1}$

indicates the direction of the driving force term. The penalisation forcing term (Fadlun et al. Reference Fadlun, Verzicco, Orlandi and Mohd-Yusof2000) is calculated as

$\delta _{i1}$

indicates the direction of the driving force term. The penalisation forcing term (Fadlun et al. Reference Fadlun, Verzicco, Orlandi and Mohd-Yusof2000) is calculated as

where

![]() $v_i$

is the velocity imposed at the boundary of the particle (i.e. zero for a stationary object) and

$v_i$

is the velocity imposed at the boundary of the particle (i.e. zero for a stationary object) and

![]() $\Delta t$

is the time step used in the simulation. Here, the index

$\Delta t$

is the time step used in the simulation. Here, the index

![]() $i=1,\ 2$

and

$i=1,\ 2$

and

![]() $3$

denotes the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions, respectively, as sketched in figure 1.

$3$

denotes the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions, respectively, as sketched in figure 1.

The governing equations are spatially discretised using a second-order accurate, finite-difference method over a staggered grid, and integrated in time using a third-order accurate, three-step Runge–Kutta method based on the fractional-step algorithm (Kim & Moin Reference Kim and Moin1985; Costa Reference Costa2018; Ferziger, Perić & Street Reference Ferziger, Perić and Street2019). All the terms in the momentum equation are discretised explicitly and the time integration is performed such that the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy number does not exceed a value of 0.95. The governing equations are solved using the massively parallel numerical simulation framework CaNS, which has been extensively validated for channel flows at high Reynolds numbers (Costa Reference Costa2018). The computational domain is parallelised using the two-dimensional pencil domain decomposition library developed by Li & Laizet (Reference Li and Laizet2010) and implemented using modern Fortran (Fortran 2004) using the Message-Passing Interface (MPI) for efficient parallel communication over multiple nodes. Additional details of the computational methodology are discussed in Costa (Reference Costa2018) and are not repeated here for brevity.

To introduce a floating carpet composed of individual spheres, an MPI-enabled signed-distance-field (SDF) generator is used (Patil, Paranjothi & García-Sánchez Reference Patil, Paranjothi and García-Sánchez2025), which is based on a geometry-local distance algorithm. All solid objects introduced within the computational domain are identified by correctly masking the negative SDF values that correspond to the inside of the solid object. As for the initial condition, to guarantee rapid development of a turbulent boundary layer for the flow transition simulations (figure 2

f–h), a physical obstacle is placed at the bottom wall to mimic a tripping device traditionally used in experimental facilities. For the simulations with periodic boundary conditions along the streamwise and the spanwise directions, however, a pair of vortices is introduced at the top of the channel that descend downwards to induce turbulence (Perry, Lim & Teh Reference Perry, Lim and Teh1981; Wu Reference Wu2023). A no-slip condition is enforced at the bottom boundary and the top (smooth and rough) boundary, and a free-slip condition is imposed for the free surface assuming the rigid-lid assumption. All data are averaged in time and along the homogeneous directions, respectively, after an initial spin-up time of 10 eddy turnovers (

![]() $T_\epsilon \equiv H/u_{{*b}}$

, where

$T_\epsilon \equiv H/u_{{*b}}$

, where

![]() $H$

is the channel height and

$H$

is the channel height and

![]() $u_{{*b}}$

is the friction velocity at the smooth bottom boundary) and the results are averaged over a total of

$u_{{*b}}$

is the friction velocity at the smooth bottom boundary) and the results are averaged over a total of

![]() $15T_\epsilon$

.

$15T_\epsilon$

.

Figure 2. Various simulation scenarios considered in this work. (a–e) Periodic boundary conditions are employed with a constant bulk velocity

![]() $U_{bH}$

, while in (f–h) inflow/outflow conditions are used with a tripping mechanism for a rapid development of the turbulent boundary layer. (a,b,d,e) Auxiliary simulations that are used to compare the flow development of the cases in (f–h). The latter three simulations consider the flow transition from the free-slip to no-slip condition at the top boundary. In further analysis of transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3, the

$U_{bH}$

, while in (f–h) inflow/outflow conditions are used with a tripping mechanism for a rapid development of the turbulent boundary layer. (a,b,d,e) Auxiliary simulations that are used to compare the flow development of the cases in (f–h). The latter three simulations consider the flow transition from the free-slip to no-slip condition at the top boundary. In further analysis of transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3, the

![]() $x_1^*=x_1-75H$

coordinate is used for streamwise direction as shown in (f–h).

$x_1^*=x_1-75H$

coordinate is used for streamwise direction as shown in (f–h).

In this work, the flow quantity

![]() $\theta$

is decomposed as

$\theta$

is decomposed as

where

![]() $\overline {\theta }$

denotes the time-averaged quantity,

$\overline {\theta }$

denotes the time-averaged quantity,

![]() $\theta '$

the temporal (turbulent) fluctuation,

$\theta '$

the temporal (turbulent) fluctuation,

![]() $\langle \overline {\theta } \rangle$

the time- and plane-averaged quantity and

$\langle \overline {\theta } \rangle$

the time- and plane-averaged quantity and

![]() $\widetilde {\theta }$

the dispersive or spatial deviations when compared with the time-averaged quantity

$\widetilde {\theta }$

the dispersive or spatial deviations when compared with the time-averaged quantity

![]() $\overline {\theta }$

. For cases where the streamwise and spanwise directions are homogeneous, a periodic boundary condition is applied along these directions (i.e.

$\overline {\theta }$

. For cases where the streamwise and spanwise directions are homogeneous, a periodic boundary condition is applied along these directions (i.e.

![]() $x_1$

and

$x_1$

and

![]() $x_2$

), thus allowing for the (intrinsic) plane averaging to be performed over these two coordinate directions. For cases where a flow transition is considered, the streamwise direction

$x_2$

), thus allowing for the (intrinsic) plane averaging to be performed over these two coordinate directions. For cases where a flow transition is considered, the streamwise direction

![]() $x_1$

is no longer considered homogeneous, and the plane average is performed only over the spanwise direction

$x_1$

is no longer considered homogeneous, and the plane average is performed only over the spanwise direction

![]() $x_2$

. However, in the streamwise direction the spatial averaging is performed over a diameter of the spheres in such cases, although the same notation

$x_2$

. However, in the streamwise direction the spatial averaging is performed over a diameter of the spheres in such cases, although the same notation

![]() $\langle \theta \rangle$

is used. A detailed explanation of the different simulation scenarios is presented in § 2.2 and figure 2.

$\langle \theta \rangle$

is used. A detailed explanation of the different simulation scenarios is presented in § 2.2 and figure 2.

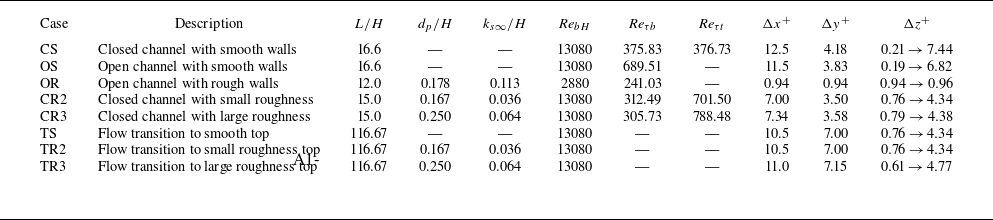

Table 1. Numerical simulations corresponding to the illustrations in figure 2. For cases CR2 and CR3, the parameters are normalised by the friction velocity at the smooth bottom boundary

![]() $u_{{*b}}$

specific to each case. For cases TR2 and TR3, however, the mesh parameters are normalised by

$u_{{*b}}$

specific to each case. For cases TR2 and TR3, however, the mesh parameters are normalised by

![]() $u_{{*b}}$

from cases CR2 and CR3, respectively. In case TS, the flow parameters are normalised by

$u_{{*b}}$

from cases CR2 and CR3, respectively. In case TS, the flow parameters are normalised by

![]() $u_{{*b}}$

from case CR2.

$u_{{*b}}$

from case CR2.

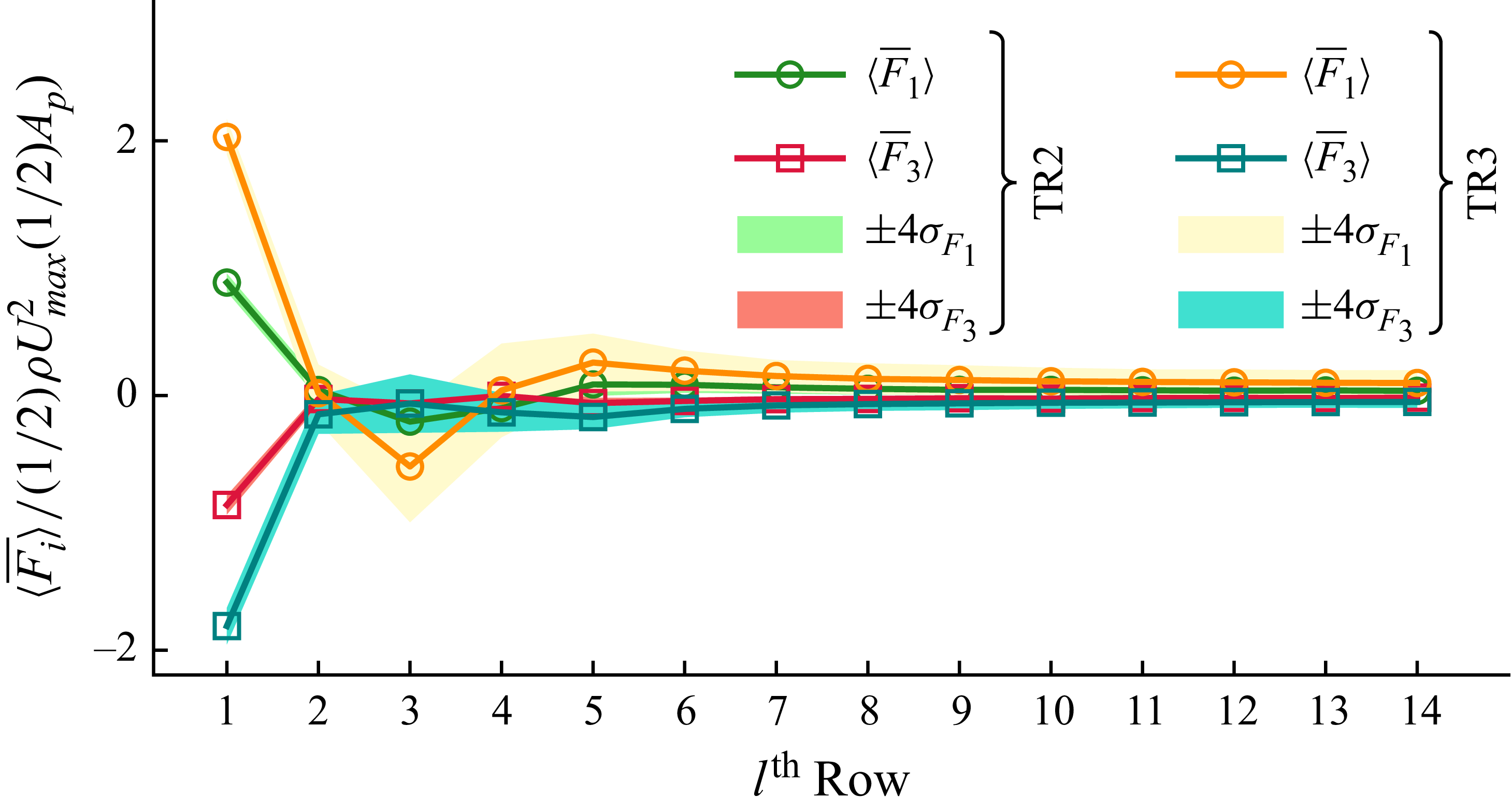

The total force acting on the particles is extracted by integrating the penalisation forcing term over the volume of the roughness layer. The force is in turn used to determine the friction velocity at the rough layer

![]() $u_{*{t}}$

via

$u_{*{t}}$

via

![]() $u_{*{t}} = \sqrt {\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}} \rangle /\rho }$

(Yuan & Piomelli Reference Yuan and Piomelli2014; Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019), where

$u_{*{t}} = \sqrt {\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}} \rangle /\rho }$

(Yuan & Piomelli Reference Yuan and Piomelli2014; Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019), where

![]() $\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}} \rangle$

is the time- and space-averaged wall shear stress. Alternatively, the wall shear stress can be obtained from the extrapolation of the linear shear stress profile to the bed, though this approach is not applicable to flow transition cases where the fully developed flow is not yet realised. Therefore, in such cases the shear stress

$\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}} \rangle$

is the time- and space-averaged wall shear stress. Alternatively, the wall shear stress can be obtained from the extrapolation of the linear shear stress profile to the bed, though this approach is not applicable to flow transition cases where the fully developed flow is not yet realised. Therefore, in such cases the shear stress

![]() $\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}}\rangle$

acting on each row of particles within the carpet (denoted as the

$\langle \overline {\tau }_{{t}}\rangle$

acting on each row of particles within the carpet (denoted as the

![]() $l{\rm th}$

row for

$l{\rm th}$

row for

![]() $l=1,2,3,\dots$

in figure 2

g,h) is calculated by dividing the horizontal component of the averaged penalisation force

$l=1,2,3,\dots$

in figure 2

g,h) is calculated by dividing the horizontal component of the averaged penalisation force

![]() $\langle \overline {F}_1 \rangle _l$

acting on that row by the projected area, i.e. the product of the channel width

$\langle \overline {F}_1 \rangle _l$

acting on that row by the projected area, i.e. the product of the channel width

![]() $B$

and sphere diameter

$B$

and sphere diameter

![]() $d_{{p}}$

.

$d_{{p}}$

.

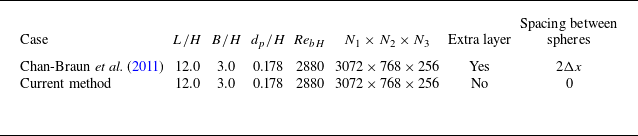

2.2. Simulation scenarios

To investigate the hydrodynamics of floating carpets under various flow conditions, we consider eight flow configurations as detailed in table 1 and illustrated in figure 2. The first five cases are described as (a) case CS: closed channel flow with both smooth bottom and top boundaries; (b) case OS: open channel flow with a smooth bottom boundary and free surface at the top; (c) case OR: open channel flow with a rough bottom boundary and free surface at the top; (d) case CR2; and (e) case CR3: closed channel with a rough top boundary and a smooth bottom boundary. Case CR2 has a relative roughness given by

![]() $d_{{p}}/H = 1/6$

and case CR3 has

$d_{{p}}/H = 1/6$

and case CR3 has

![]() $d_{{p}}/H=1/4$

. The aforementioned five cases are intended as the benchmark cases, while case OR is considered to validate the volume penalisation methodology implemented for this study. Case OR corresponds to the F50 configuration in Chan-Braun, García-Villalba & Uhlmann (Reference Chan-Braun, García-Villalba and Uhlmann2011). As presented in Appendix A.1, the comparison between the methodology used in this work and the results in Chan-Braun et al. (Reference Chan-Braun, García-Villalba and Uhlmann2011) shows a good agreement, thus validating the current numerical framework. Details about the validation procedure can be found in Appendix A.1. As for cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3, flow conditions and geometry parameters are identical to those of the laboratory experiments of Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). In cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3, a constant pressure gradient drives the flow such that the bulk Reynolds number

$d_{{p}}/H=1/4$

. The aforementioned five cases are intended as the benchmark cases, while case OR is considered to validate the volume penalisation methodology implemented for this study. Case OR corresponds to the F50 configuration in Chan-Braun, García-Villalba & Uhlmann (Reference Chan-Braun, García-Villalba and Uhlmann2011). As presented in Appendix A.1, the comparison between the methodology used in this work and the results in Chan-Braun et al. (Reference Chan-Braun, García-Villalba and Uhlmann2011) shows a good agreement, thus validating the current numerical framework. Details about the validation procedure can be found in Appendix A.1. As for cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3, flow conditions and geometry parameters are identical to those of the laboratory experiments of Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). In cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3, a constant pressure gradient drives the flow such that the bulk Reynolds number

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{bH}=13\,080$

is achieved, where

$ \textit{Re}_{bH}=13\,080$

is achieved, where

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{bH}={(U_{bH}\!H)}/{\nu }$

, in which

$ \textit{Re}_{bH}={(U_{bH}\!H)}/{\nu }$

, in which

![]() $U_{bH}=(1/H)\int _{0}^H \langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle {\rm d}x_3$

is the bulk velocity based on

$U_{bH}=(1/H)\int _{0}^H \langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle {\rm d}x_3$

is the bulk velocity based on

![]() $H$

.

$H$

.

To examine the impact of the transition, three main simulations are considered in this work, namely cases TS, TR2 and TR3 and illustrated in figures 2(f)–2(h), respectively. Case TS is the case with a transition from a smooth open channel to a smooth closed channel. Case TR2 denotes the scenario with a transition from a smooth open channel to a closed channel with a rough top boundary characterised by relatively small roughness (

![]() $d_{{p}}/H=1/6$

). Case TR3 considers a flow configuration similar to that of case TR2 with relatively larger roughness (

$d_{{p}}/H=1/6$

). Case TR3 considers a flow configuration similar to that of case TR2 with relatively larger roughness (

![]() $d_{{p}}/H=1/4$

). In these transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3, a uniform velocity profile is prescribed at the inlet boundary, and the flow develops towards a turbulent boundary layer due to the tripping placed at the bottom wall (see figure 2

f–h). The tripping used in this study consists of a line of hemispheres of diameter

$d_{{p}}/H=1/4$

). In these transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3, a uniform velocity profile is prescribed at the inlet boundary, and the flow develops towards a turbulent boundary layer due to the tripping placed at the bottom wall (see figure 2

f–h). The tripping used in this study consists of a line of hemispheres of diameter

![]() $d_{{p}}=0.01$

(

$d_{{p}}=0.01$

(

![]() $d_{{p}}/H\approx 0.08$

) placed at

$d_{{p}}/H\approx 0.08$

) placed at

![]() $x_1=0.10$

m downstream of the inlet plane. The floating carpet is placed at a distance

$x_1=0.10$

m downstream of the inlet plane. The floating carpet is placed at a distance

![]() $x_1/H=75$

away from the inlet boundary to allow a sufficiently long fetch for a fully developed condition. The length of the floating carpet layer

$x_1/H=75$

away from the inlet boundary to allow a sufficiently long fetch for a fully developed condition. The length of the floating carpet layer

![]() $\lambda$

is set to

$\lambda$

is set to

![]() $\lambda /H = 100/3$

. At the outlet boundary of the flow domain, a Neumann velocity boundary condition is prescribed, while the pressure at the outlet boundary is set to

$\lambda /H = 100/3$

. At the outlet boundary of the flow domain, a Neumann velocity boundary condition is prescribed, while the pressure at the outlet boundary is set to

![]() $p = 0$

. It is noted that the current method of imposing a Neumann boundary condition on the streamwise velocity component, combined with the prescribed inflow, naturally imposes the net pressure difference that sustains the flow in this spatially developing channel as in the experiments, whereas this particular combination is not suitable for simulations of a zero-pressure-gradient turbulent boundary layer.

$p = 0$

. It is noted that the current method of imposing a Neumann boundary condition on the streamwise velocity component, combined with the prescribed inflow, naturally imposes the net pressure difference that sustains the flow in this spatially developing channel as in the experiments, whereas this particular combination is not suitable for simulations of a zero-pressure-gradient turbulent boundary layer.

For all rough-channel cases CR2, CR3, TR2 and TR3, the roughness height

![]() $k$

is defined as the radius of the individual spherical particles (

$k$

is defined as the radius of the individual spherical particles (

![]() $0.5d_{{p}}$

) of the floating carpet as assumed by Wu, Christensen & Pantano (Reference Wu, Christensen and Pantano2020). Therefore, the relative roughness for cases CR2 and TR2 is

$0.5d_{{p}}$

) of the floating carpet as assumed by Wu, Christensen & Pantano (Reference Wu, Christensen and Pantano2020). Therefore, the relative roughness for cases CR2 and TR2 is

![]() $k/H=0.0833$

and for cases CR3 and TR3 is

$k/H=0.0833$

and for cases CR3 and TR3 is

![]() $k/H=0.125$

. While the roughness height is known a priori, the equivalent sand grain roughness for large Reynolds number

$k/H=0.125$

. While the roughness height is known a priori, the equivalent sand grain roughness for large Reynolds number

![]() $k_{s\infty }$

and the virtual origin

$k_{s\infty }$

and the virtual origin

![]() $z_0$

(Nikuradse Reference Nikuradse1933) are derived in Appendix A.2. For some of the cases listed in table 1, the location of the maximum streamwise velocity (

$z_0$

(Nikuradse Reference Nikuradse1933) are derived in Appendix A.2. For some of the cases listed in table 1, the location of the maximum streamwise velocity (

![]() $U_{\textit{max}}$

) is a length scale of interest and, therefore, a friction Reynolds number at the bottom boundary is defined as

$U_{\textit{max}}$

) is a length scale of interest and, therefore, a friction Reynolds number at the bottom boundary is defined as

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{{\tau b}} = u_{{*b}} z_m/\nu$

, where

$ \textit{Re}_{{\tau b}} = u_{{*b}} z_m/\nu$

, where

![]() $z_m$

is the location of

$z_m$

is the location of

![]() $U_{\textit{max}}$

normal to the wall, and a friction Reynolds number at the rough top boundary is defined as

$U_{\textit{max}}$

normal to the wall, and a friction Reynolds number at the rough top boundary is defined as

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{{\tau t}} = u_{{*t}} (H-z_m)/\nu$

. In all rough-channel simulations, the spheres are placed in a regular uniform arrangement.

$ \textit{Re}_{{\tau t}} = u_{{*t}} (H-z_m)/\nu$

. In all rough-channel simulations, the spheres are placed in a regular uniform arrangement.

Figure 3. Mean velocity profiles (a) upstream of the transition for all transition cases and (b–d) downstream of the transition for cases TS, TR2 and TR3. The hatched area indicates

![]() $\pm 2\,\%$

of velocity profiles of cases OS, CS, CR2 and CR3, respectively. The colourbars mark the positions of the mean velocity profiles along the streamwise direction of the channel with respect to the location of the transition. The red shading in (b) marks

$\pm 2\,\%$

of velocity profiles of cases OS, CS, CR2 and CR3, respectively. The colourbars mark the positions of the mean velocity profiles along the streamwise direction of the channel with respect to the location of the transition. The red shading in (b) marks

![]() $\pm \sigma /2$

around the experimental data of Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025) (

$\pm \sigma /2$

around the experimental data of Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025) (

![]() $\sigma$

is the standard deviation). The colourbars indicate the streamwise position with respect to the transition point.

$\sigma$

is the standard deviation). The colourbars indicate the streamwise position with respect to the transition point.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Streamwise development of global quantities

To analyse the fully developed flow condition as a function of the streamwise distance from the inflow boundary, we discuss the development of the time- and plane-averaged flow parameters, i.e. mean velocity and Reynolds shear stress, for cases TR2 and TR3. These quantities are compared with the results from cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3 that serve as benchmark datasets.

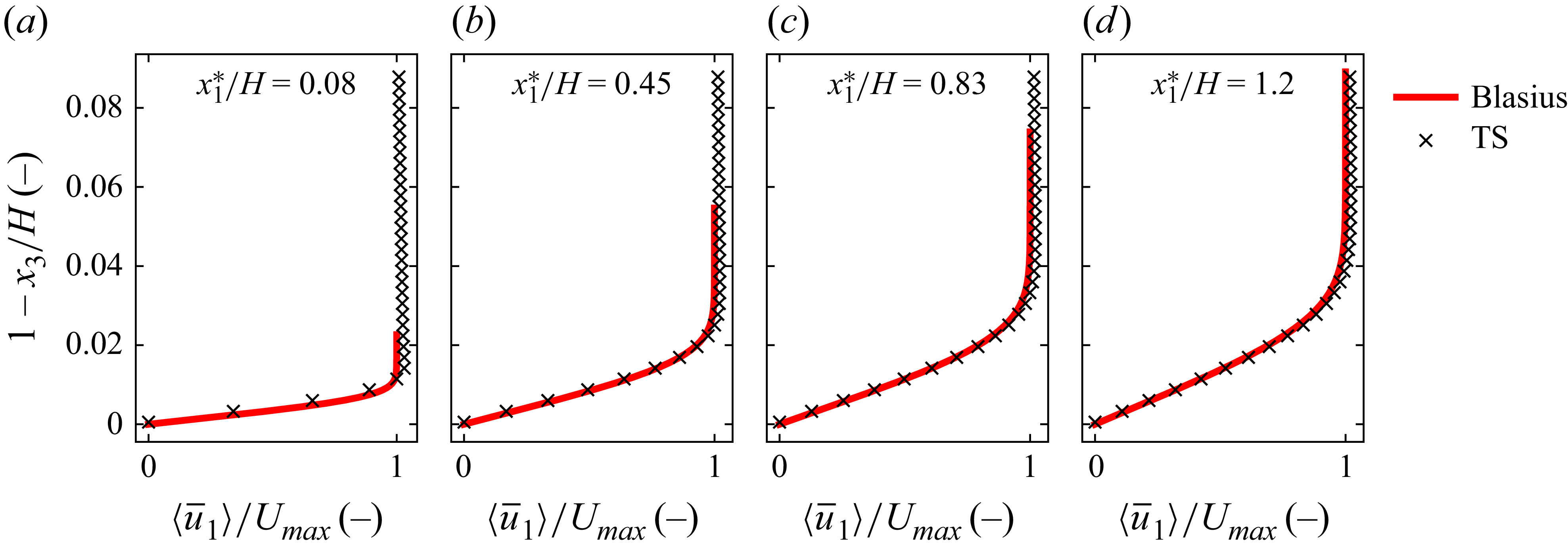

Figure 3 compares the development of time- and plane-averaged velocity profiles along the streamwise direction of the channel for cases TS, TR2 and TR3. Here the streamwise coordinate origin is set at the start of the floating carpet such that the negative values for the streamwise direction

![]() $(x_1-75H)/H\lt 0$

correspond to the flow domain upstream of the carpet, while the positive values for the streamwise direction

$(x_1-75H)/H\lt 0$

correspond to the flow domain upstream of the carpet, while the positive values for the streamwise direction

![]() $(x_1 - 75H)/H\gt 0$

correspond to the downstream reach of the carpet. Hereafter,

$(x_1 - 75H)/H\gt 0$

correspond to the downstream reach of the carpet. Hereafter,

![]() $(x_1-75H)/H$

will be referred to as

$(x_1-75H)/H$

will be referred to as

![]() $x_1^*/H$

, where

$x_1^*/H$

, where

![]() $x_1^*=x_1-75H$

, denoted by the colourbars in figure 3. The time- and plane-averaged streamwise velocity profile

$x_1^*=x_1-75H$

, denoted by the colourbars in figure 3. The time- and plane-averaged streamwise velocity profile

![]() $\langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle (x_3)$

upstream of the transition in cases TS, TR2 and TR3 is observed to compare well with the profile obtained for the statistically stationary flow of case OS within

$\langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle (x_3)$

upstream of the transition in cases TS, TR2 and TR3 is observed to compare well with the profile obtained for the statistically stationary flow of case OS within

![]() $2\,\%$

range of accuracy (figure 3

a). At the transition point

$2\,\%$

range of accuracy (figure 3

a). At the transition point

![]() $x_1^*/H=0$

and downstream locations

$x_1^*/H=0$

and downstream locations

![]() $x_1^*/H\gt 0$

as shown in figure 3(b–d), the flow encounters a floating carpet and thus undergoes an adaptation to the no-slip boundary condition. In case TS, the velocity profiles do not reach the fully developed velocity profile when compared with the benchmark profile of case CS (figure 3

b). In contrast, case TR2 (figure 3

c) and case TR3 (figure 3

d) exhibit a fully developed flow condition at

$x_1^*/H\gt 0$

as shown in figure 3(b–d), the flow encounters a floating carpet and thus undergoes an adaptation to the no-slip boundary condition. In case TS, the velocity profiles do not reach the fully developed velocity profile when compared with the benchmark profile of case CS (figure 3

b). In contrast, case TR2 (figure 3

c) and case TR3 (figure 3

d) exhibit a fully developed flow condition at

![]() $x_1^*/H \approx 33$

. The benchmark results from cases CS, CR2 and CR3 are also shown in figure 3(b–d).

$x_1^*/H \approx 33$

. The benchmark results from cases CS, CR2 and CR3 are also shown in figure 3(b–d).

Figure 4. Comparison of mean velocity profiles normalised by inner scaling: (a) comparison in the vicinity of the physical tripping, (b) comparison upstream of the transition, (c) comparison in the lower half of the channel for case TS, (d) comparison for the upper half of the channel where the debris accumulates, (e) comparison for the bottom half of the channel for case TR2 after the transition and (f) comparison for the upper half of the channel for case TR2 after the transition. In cases TS and TR2, the velocity profiles under the carpet are divided based on the location of the maximum streamwise velocity

![]() $z_m$

. Since velocity profiles of case TR3 do not show any significant difference from those of case TR2, results of case TR3 are omitted.

$z_m$

. Since velocity profiles of case TR3 do not show any significant difference from those of case TR2, results of case TR3 are omitted.

To investigate the flow behaviour in the near-wall region, the above-mentioned velocity profiles are plotted again using the viscous length scale or wall unit in figure 4. In all subfigures, the velocity profiles are shifted by

![]() $\Delta U^+=5$

for clear visualisation. Figure 4(a) shows the evolution of the flow immediately downstream of the tripping mechanism, and the logarithmic profile is recovered at

$\Delta U^+=5$

for clear visualisation. Figure 4(a) shows the evolution of the flow immediately downstream of the tripping mechanism, and the logarithmic profile is recovered at

![]() $x_1^*/H=-40$

. The development of flow profiles upstream of the transition point is depicted in figure 4(b), showing that the approach flow to the carpet compares well against the logarithmic mean velocity profile. To study the velocity profiles in the closed channel region of cases TS and TR2, the profiles are divided based on the location of maximum streamwise velocity, and shown separately in figure 4(c–f). For the rough-channel case TR2, the velocity profiles in the top part need to be shifted for their virtual origins where the logarithmic velocity profile begins, which is further elaborated in Appendix A.2, in figure 4(f). The velocity profiles in all cases are observed to recover at

$x_1^*/H=-40$

. The development of flow profiles upstream of the transition point is depicted in figure 4(b), showing that the approach flow to the carpet compares well against the logarithmic mean velocity profile. To study the velocity profiles in the closed channel region of cases TS and TR2, the profiles are divided based on the location of maximum streamwise velocity, and shown separately in figure 4(c–f). For the rough-channel case TR2, the velocity profiles in the top part need to be shifted for their virtual origins where the logarithmic velocity profile begins, which is further elaborated in Appendix A.2, in figure 4(f). The velocity profiles in all cases are observed to recover at

![]() $x_1^*/H=30$

and agree with benchmark results. Since the velocity profiles of case TR3 show shapes similar to those of case TR2, the results of case TR3 are omitted here.

$x_1^*/H=30$

and agree with benchmark results. Since the velocity profiles of case TR3 show shapes similar to those of case TR2, the results of case TR3 are omitted here.

A rapid recovery of first-order statistics, i.e. mean streamwise velocity, is observed in the rough transition cases TR2 and TR3 due to the additional momentum mixing induced by the spheres of the rough carpet. However, in the smooth transition case TS, the first-order statistics cannot be recovered immediately downstream of the transition. Moreover, the simulation results of cases CR2 and TR2 show a good comparison with the experimental result from Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025) in the fully developed condition, except for a slight deviation near the top rough wall (figure 3

c). It should be noted that the laboratory experiments used spheres with a slightly higher submergence of

![]() $87\,\%$

.

$87\,\%$

.

Figure 5. Reynolds shear stress profiles for case TR2: (a) upstream of the flow transition and (b) downstream of the transition. The colourbars mark the positions of the Reynolds shear stress profiles along the streamwise direction of the channel with respect to the location of the transition. Since the streamwise position

![]() $x_1^*/H\approx 36$

is beyond the end of the carpet and the flow transitions to open-channel flow again (figure 2

g), the stress profile does not follow the benchmark profile.

$x_1^*/H\approx 36$

is beyond the end of the carpet and the flow transitions to open-channel flow again (figure 2

g), the stress profile does not follow the benchmark profile.

The streamwise evolution of the Reynolds shear stress profile for case TR2 is compared against the benchmark cases OS and CR2 in figures 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. Upstream of the transition, the Reynolds stress profiles for cases TR2 and OS are observed to be in good agreement (figure 5

a), whereas the profiles under the carpet in figure 5(b) fail to recover to the linear stress profile observed for the benchmark case CR2. It is noted that at

![]() $x_1^*/H \approx -1$

, which is very close to the transition point, the flow already experiences the step change and consequently the profile near the bottom boundary does not agree exactly with the benchmark velocity profile of case OS (figure 5

a). Similarly, since the streamwise position

$x_1^*/H \approx -1$

, which is very close to the transition point, the flow already experiences the step change and consequently the profile near the bottom boundary does not agree exactly with the benchmark velocity profile of case OS (figure 5

a). Similarly, since the streamwise position

![]() $x_1^*/H\approx 36$

represents the location downstream of the end of the carpet, the flow transitions again to the open channel flow (denoted as free-slip boundary condition in figure 2

g) and the stress profile is found to deviate from the benchmark case CR2 in figure 5(b). The relatively slow response of the Reynolds stress under the carpet follows the trends previously observed by Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) and Van Buren et al. (Reference Van Buren, Floryan, Ding, Hellström and Smits2020). A similar trend was seen for case TR3, which is not shown here for brevity. There are, however, some minor differences observed closer to the bottom wall when comparing the numerical and the experimental results, which can be presumably attributed to the experimental measurement limitations and additional sidewall effects of the flume. Overall, both the time- and plane-averaged mean flow response and the Reynolds stress profile compare well with the benchmark cases, suggesting that the approach flow conditions upstream of the transition are fully developed in cases TS, TR2 and TR3. Moreover, larger shear stresses are observed near the rough top boundary compared with those near the bottom boundary downstream of the transition point because of roughness-induced turbulence stresses. It is noted that variations in debris size and shape can lead to different observations of the stress distribution.

$x_1^*/H\approx 36$

represents the location downstream of the end of the carpet, the flow transitions again to the open channel flow (denoted as free-slip boundary condition in figure 2

g) and the stress profile is found to deviate from the benchmark case CR2 in figure 5(b). The relatively slow response of the Reynolds stress under the carpet follows the trends previously observed by Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) and Van Buren et al. (Reference Van Buren, Floryan, Ding, Hellström and Smits2020). A similar trend was seen for case TR3, which is not shown here for brevity. There are, however, some minor differences observed closer to the bottom wall when comparing the numerical and the experimental results, which can be presumably attributed to the experimental measurement limitations and additional sidewall effects of the flume. Overall, both the time- and plane-averaged mean flow response and the Reynolds stress profile compare well with the benchmark cases, suggesting that the approach flow conditions upstream of the transition are fully developed in cases TS, TR2 and TR3. Moreover, larger shear stresses are observed near the rough top boundary compared with those near the bottom boundary downstream of the transition point because of roughness-induced turbulence stresses. It is noted that variations in debris size and shape can lead to different observations of the stress distribution.

Streamwise development of turbulent normal stresses

![]() $\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle$

is also investigated using inner scaling and outer scaling in figures 6(a–c) and 6(d–f), respectively, for case TR2. The profiles are found to approach the benchmark results gradually as expected. As reported by Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008), the normal stress profiles also show an asymmetric shape in the rough–smooth closed channel due to the different roughnesses. Detailed study of turbulent normal stresses is presented in Appendix A.3 for cases TS and TR3, including the development of the profiles at the inflow section, downstream of the tripping point.

$\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle$

is also investigated using inner scaling and outer scaling in figures 6(a–c) and 6(d–f), respectively, for case TR2. The profiles are found to approach the benchmark results gradually as expected. As reported by Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008), the normal stress profiles also show an asymmetric shape in the rough–smooth closed channel due to the different roughnesses. Detailed study of turbulent normal stresses is presented in Appendix A.3 for cases TS and TR3, including the development of the profiles at the inflow section, downstream of the tripping point.

Figure 6. Vertical profiles of turbulent normal stresses

![]() $\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle$

downstream of the transition point

$\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle$

downstream of the transition point

![]() $x_1^*/H\gt 0$

: (a–c) using inner scaling and (d–f) using outer scaling. Yellow-coloured areas in (d–f) indicate the height of the roughness.

$x_1^*/H\gt 0$

: (a–c) using inner scaling and (d–f) using outer scaling. Yellow-coloured areas in (d–f) indicate the height of the roughness.

Figure 7. Development of top boundary layer

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

, displacement thickness

$\delta ^{{t}}$

, displacement thickness

![]() $\delta _*^{{t}}$

and momentum thickness

$\delta _*^{{t}}$

and momentum thickness

![]() $\varTheta ^{{t}}$

: (a,c,e) near the transition (zoom-in view for the horizontal dimension) and (b,d,f) under the carpet for cases (a,b) TS, (c,d) TR2 and (e,f) TR3. Yellow regions represent the floating carpet (not to scale).

$\varTheta ^{{t}}$

: (a,c,e) near the transition (zoom-in view for the horizontal dimension) and (b,d,f) under the carpet for cases (a,b) TS, (c,d) TR2 and (e,f) TR3. Yellow regions represent the floating carpet (not to scale).

To study the impact of the floating carpet on the bulk flow, we consider three different metrics that quantify the boundary-layer development: the displacement thickness (

![]() $\delta _*^{{t}}$

) given by

$\delta _*^{{t}}$

) given by

the momentum thickness (

![]() $\varTheta ^{{t}}$

) given by

$\varTheta ^{{t}}$

) given by

and the top boundary layer (

![]() $\delta ^{{t}} \equiv z_m$

) defined as the distance from the wall where the streamwise velocity has a maximum value (

$\delta ^{{t}} \equiv z_m$

) defined as the distance from the wall where the streamwise velocity has a maximum value (

![]() $U_{\textit{max}}$

). Figure 7 compares the above-mentioned metrics for the boundary-layer growth under the floating carpet for cases TS, TR2 and TR3. As the flow approaches the floating carpet, the mean flow is observed to experience the effect of the carpet even in the upstream region as indicated by

$U_{\textit{max}}$

). Figure 7 compares the above-mentioned metrics for the boundary-layer growth under the floating carpet for cases TS, TR2 and TR3. As the flow approaches the floating carpet, the mean flow is observed to experience the effect of the carpet even in the upstream region as indicated by

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

(figure 7

a,c,e). A more pronounced effect is observed in the case of the rough carpet (figure 7

c,e), whereas a smaller effect is seen in the smooth transition case TS (figure 7

a). Subsequently, the mean flow deflects with a vertically downward flow as shown in figure 17. For case TR2, the top boundary layer (red dashed-dot line in figure 7

d) extends from the top wall to the vertical position of

$\delta ^{{t}}$

(figure 7

a,c,e). A more pronounced effect is observed in the case of the rough carpet (figure 7

c,e), whereas a smaller effect is seen in the smooth transition case TS (figure 7

a). Subsequently, the mean flow deflects with a vertically downward flow as shown in figure 17. For case TR2, the top boundary layer (red dashed-dot line in figure 7

d) extends from the top wall to the vertical position of

![]() $(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \approx 0.4$

and asymptotes to a constant value along the streamwise direction at

$(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \approx 0.4$

and asymptotes to a constant value along the streamwise direction at

![]() $x_1^*/H\geqslant 30$

, suggesting a fully developed flow condition underneath the carpet. The momentum thickness

$x_1^*/H\geqslant 30$

, suggesting a fully developed flow condition underneath the carpet. The momentum thickness

![]() $\varTheta ^{{t}}$

and the displacement thickness

$\varTheta ^{{t}}$

and the displacement thickness

![]() $\delta _*^{{t}}$

are observed to be relatively smaller compared with

$\delta _*^{{t}}$

are observed to be relatively smaller compared with

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

as expected. Comparing the boundary-layer growths across cases TS, TR2 and TR3, the relatively larger roughness height in case TR3 induces a larger boundary-layer thickness (figure 7

f), while a smaller boundary layer is observed in the smooth carpet case TS (figure 7

b) for all the metrics discussed above. This is especially true when comparing the asymptotic behaviour where case TR2 is observed to attain a value of

$\delta ^{{t}}$

as expected. Comparing the boundary-layer growths across cases TS, TR2 and TR3, the relatively larger roughness height in case TR3 induces a larger boundary-layer thickness (figure 7

f), while a smaller boundary layer is observed in the smooth carpet case TS (figure 7

b) for all the metrics discussed above. This is especially true when comparing the asymptotic behaviour where case TR2 is observed to attain a value of

![]() $(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \approx 0.4$

, while case TS attains a smaller value of

$(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \approx 0.4$

, while case TS attains a smaller value of

![]() $(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H\approx 0.6$

and case TR3 attains a slightly larger value of

$(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H\approx 0.6$

and case TR3 attains a slightly larger value of

![]() $(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \lt 0.4$

(here smaller values mean a deeper top boundary layer), thus clearly illustrating the impact of the relative roughness height.

$(H-\delta ^{{t}})/H \lt 0.4$

(here smaller values mean a deeper top boundary layer), thus clearly illustrating the impact of the relative roughness height.

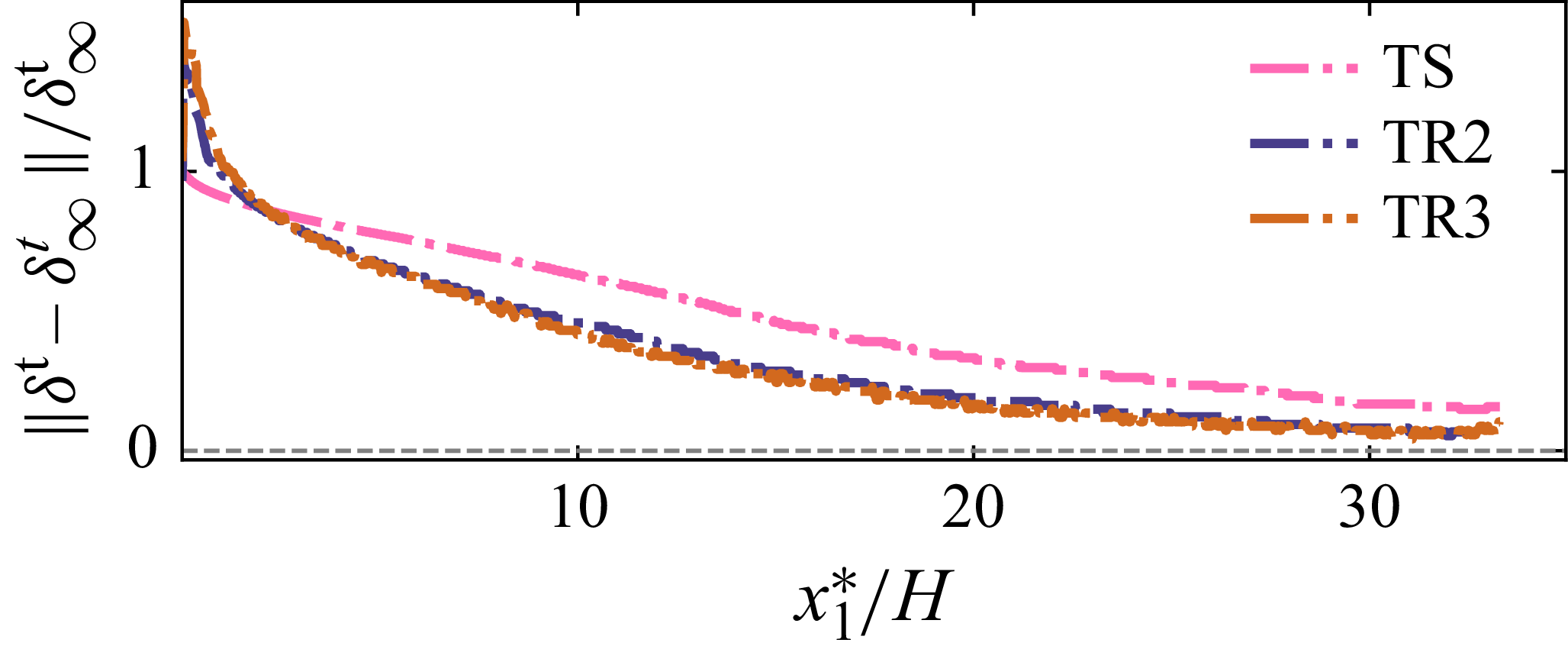

We also quantify the relative development of

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

with respect to the asymptotic value

$\delta ^{{t}}$

with respect to the asymptotic value

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

that is obtained from the corresponding benchmark cases, giving the ratio

$\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

that is obtained from the corresponding benchmark cases, giving the ratio

![]() $\| \delta ^{{t}} - \delta ^{{t}}_\infty \|/\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

as shown in figure 8. All cases TS, TR2 and TR3 exhibit a similar relative growth of

$\| \delta ^{{t}} - \delta ^{{t}}_\infty \|/\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

as shown in figure 8. All cases TS, TR2 and TR3 exhibit a similar relative growth of

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

although the shape of case TS differs slightly from that of cases TR2 and TR3, which share an identical shape. Therefore, different roughness heights do not affect the relative growth rate of the boundary layer,

$\delta ^{{t}}$

although the shape of case TS differs slightly from that of cases TR2 and TR3, which share an identical shape. Therefore, different roughness heights do not affect the relative growth rate of the boundary layer,

![]() $\| \delta ^{{t}} - \delta ^{{t}}_\infty \|/\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

.

$\| \delta ^{{t}} - \delta ^{{t}}_\infty \|/\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

.

Figure 8. Relative development of top boundary layer

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

with respect to its asymptotic value

$\delta ^{{t}}$

with respect to its asymptotic value

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

. The asymptotic value is obtained from the corresponding periodic benchmark cases.

$\delta ^{{t}}_\infty$

. The asymptotic value is obtained from the corresponding periodic benchmark cases.

Similar to a conventional smooth boundary layer, the displacement thickness

![]() $\delta ^{*{t}}$

and the momentum thickness

$\delta ^{*{t}}$

and the momentum thickness

![]() $\varTheta ^{{t}}$

are smaller than the boundary-layer thickness

$\varTheta ^{{t}}$

are smaller than the boundary-layer thickness

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

in all transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3. At the location of the fully developed flow in case TR2, their ratios are found to be

$\delta ^{{t}}$

in all transition cases TS, TR2 and TR3. At the location of the fully developed flow in case TR2, their ratios are found to be

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}/\delta _*^{{t}}=3.8$

and

$\delta ^{{t}}/\delta _*^{{t}}=3.8$

and

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}/\varTheta ^{{t}}=9.6$

, respectively. The momentum thickness is observed within the roughness layer (figure 7

d), meaning that the loss of momentum in the rough boundary layer occurs mostly inside the roughness elements. In case TR3, the thicknesses of the aforementioned three layers (

$\delta ^{{t}}/\varTheta ^{{t}}=9.6$

, respectively. The momentum thickness is observed within the roughness layer (figure 7

d), meaning that the loss of momentum in the rough boundary layer occurs mostly inside the roughness elements. In case TR3, the thicknesses of the aforementioned three layers (

![]() $\delta ^{{t}},\ \delta _*^{{t}}$

and

$\delta ^{{t}},\ \delta _*^{{t}}$

and

![]() $\varTheta ^{{t}}$

) are found to be larger than those in case TR2 because the larger roughness pushes the mass and momentum mixing layers further away. Nevertheless, the ratios

$\varTheta ^{{t}}$

) are found to be larger than those in case TR2 because the larger roughness pushes the mass and momentum mixing layers further away. Nevertheless, the ratios

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}/\delta _*^{{t}}=3.3$

and

$\delta ^{{t}}/\delta _*^{{t}}=3.3$

and

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}/\varTheta ^{{t}}=9.8$

are found in case TR3, which are approximately similar to those observed in case TR2.

$\delta ^{{t}}/\varTheta ^{{t}}=9.8$

are found in case TR3, which are approximately similar to those observed in case TR2.

In addition to the study of boundary-layer thickness, we examined the internal boundary layer (IBL)

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and internal equilibrium layer (IEL)

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and internal equilibrium layer (IEL)

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

which show the immediate response of the flow to changes in the boundary roughness. The layer to which the effect of the new boundary roughness reaches is defined as the IBL, and the lower part of the IBL which obtains a new equilibrium with the new surface is called the IEL (Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). Previous work of Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) is referred to for detailed explanation and calculation method of

$\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

which show the immediate response of the flow to changes in the boundary roughness. The layer to which the effect of the new boundary roughness reaches is defined as the IBL, and the lower part of the IBL which obtains a new equilibrium with the new surface is called the IEL (Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). Previous work of Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) is referred to for detailed explanation and calculation method of

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

that we apply here. In brief, the slope curve

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

that we apply here. In brief, the slope curve

![]() $\mathrm{d}U^+/\mathrm{d}\ln {x_3^+}$

is plotted for each

$\mathrm{d}U^+/\mathrm{d}\ln {x_3^+}$

is plotted for each

![]() $x_1$

position as shown in figure 9, and two successive local extrema of the slope curve are identified. Then, two linear fits are applied to the velocity profile in the semi-log scale corresponding to these extrema, and the intersection point of the two fitted lines is determined. This intersection defines the position of

$x_1$

position as shown in figure 9, and two successive local extrema of the slope curve are identified. Then, two linear fits are applied to the velocity profile in the semi-log scale corresponding to these extrema, and the intersection point of the two fitted lines is determined. This intersection defines the position of

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

. Here

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

. Here

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

is obtained by locating the vertical position corresponding to the first logarithmic region in a composite velocity profile consisting of several individual profiles (Savelyev & Taylor Reference Savelyev and Taylor2005). Figure 9 shows

$\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

is obtained by locating the vertical position corresponding to the first logarithmic region in a composite velocity profile consisting of several individual profiles (Savelyev & Taylor Reference Savelyev and Taylor2005). Figure 9 shows

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

at the rough top surface for cases TR2 and TR3. Both internal layers (

$\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

at the rough top surface for cases TR2 and TR3. Both internal layers (

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

) are found to be almost identical, and inside the external top boundary layer

$\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

) are found to be almost identical, and inside the external top boundary layer

![]() $\delta ^{{t}}$

of the rough surface as observed in the work of Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). Some noise is observed in case TR2 which may be attributed to the sensitivity of the slope-finding method. The green line in figure 9 denotes a power-law fitted line,

$\delta ^{{t}}$

of the rough surface as observed in the work of Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). Some noise is observed in case TR2 which may be attributed to the sensitivity of the slope-finding method. The green line in figure 9 denotes a power-law fitted line,

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}} \propto (x_1^*)^\alpha$

as suggested by Li et al. (Reference Li, de Silva, Chung, Pullin, Marusic and Hutchins2022), for

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}} \propto (x_1^*)^\alpha$

as suggested by Li et al. (Reference Li, de Silva, Chung, Pullin, Marusic and Hutchins2022), for

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

to estimate its growth rate, and it is found that

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

to estimate its growth rate, and it is found that

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

varies as

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

varies as

![]() $(x_1^*)^{0.67}$

in case TR2 and varies as

$(x_1^*)^{0.67}$

in case TR2 and varies as

![]() $(x_1^*)^{0.38}$

in case TR3. The observed

$(x_1^*)^{0.38}$

in case TR3. The observed

![]() $\alpha$

values lie within 0.22 and 0.886 as reported by Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). It should be noted that previous studies on step changes (Antonia & Luxton Reference Antonia and Luxton1971; Li et al. Reference Li, De Silva, Rouhi, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2019; Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) did not consider the influence of the bottom boundary, but here the presence of the smooth bottom boundary is incorporated in the DNS study of rough boundary-layer development, creating a closed and asymmetric flow geometry.

$\alpha$

values lie within 0.22 and 0.886 as reported by Rouhi et al. (Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019). It should be noted that previous studies on step changes (Antonia & Luxton Reference Antonia and Luxton1971; Li et al. Reference Li, De Silva, Rouhi, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2019; Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Chung and Hutchins2019) did not consider the influence of the bottom boundary, but here the presence of the smooth bottom boundary is incorporated in the DNS study of rough boundary-layer development, creating a closed and asymmetric flow geometry.

Figure 9. Internal boundary layer

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and internal equilibrium layer

$\delta _{\textit{IBL}}$

and internal equilibrium layer

![]() $\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

at the top rough surface for (a) case TR2 and (b) case TR3. The vertical coordinate is the inverted coordinate such that

$\delta _{\textit{IEL}}$

at the top rough surface for (a) case TR2 and (b) case TR3. The vertical coordinate is the inverted coordinate such that

![]() $1-x_3/H=0$

is the top surface. The green line is a power-law fit.

$1-x_3/H=0$

is the top surface. The green line is a power-law fit.

Figure 10. Different terms in the streamwise momentum balance for the fully developed flow in the closed section of case TR2. (a) Overall development along the streamwise direction after the transition and (b) change in bottom shear stress

![]() $\tau _{{b}}$

(of case TR2) and

$\tau _{{b}}$

(of case TR2) and

![]() $\tau _{{bS}}$

(of case TS) in the vicinity of the transition. Throughout the transition region, the momentum balance is not complete without including the momentum flux term.

$\tau _{{bS}}$

(of case TS) in the vicinity of the transition. Throughout the transition region, the momentum balance is not complete without including the momentum flux term.

Time- and spanwise-averaged momentum balance in the streamwise direction is assessed for case TR2 in figure 10 and for case TR3 in figure 11. The streamwise momentum equation for the developing flow condition can be expressed as

where the term on the left-hand side is the advective acceleration term, the first term on the right-hand side is the pressure gradient and the last term is the streamwise gradient of the diffusive force. For the fully developed flow, the force balance equation reads after simplification

implying that the pressure drop (left-hand side) is balanced by the sum of the wall shear stresses (right-hand side) at the top and the bottom walls of the closed-channel region. Here,

![]() $\tau _{{t}}$

is the stress at the top boundary and

$\tau _{{t}}$

is the stress at the top boundary and

![]() $\tau _{{b}}$

is the stress at the bottom boundary where only the viscous stress is present. For the open-channel flow upstream of the carpet, i.e.

$\tau _{{b}}$

is the stress at the bottom boundary where only the viscous stress is present. For the open-channel flow upstream of the carpet, i.e.

![]() $x_1^*/H\lt 0$

, the driving pressure gradient

$x_1^*/H\lt 0$

, the driving pressure gradient

![]() $\mathrm{d}\langle \overline {p} \rangle /\mathrm{d}x_1$

is balanced by the shear stress only at the bottom wall

$\mathrm{d}\langle \overline {p} \rangle /\mathrm{d}x_1$

is balanced by the shear stress only at the bottom wall

![]() $\tau _{{b}}$

as shown in figure 10(b). In the vicinity of the transition, the momentum balance (3.4) is not valid since the flow is developing towards the new equilibrium. In this region, the local acceleration term

$\tau _{{b}}$

as shown in figure 10(b). In the vicinity of the transition, the momentum balance (3.4) is not valid since the flow is developing towards the new equilibrium. In this region, the local acceleration term

![]() $ ({\mathrm{d}}/{\mathrm{d}x_1}) \int _0^H \langle \overline {u_1^2} \rangle \mathrm{d}x_3$

also plays an important role to balance with the pressure gradient force. Afterwards, the flow approaches the fully developed condition at

$ ({\mathrm{d}}/{\mathrm{d}x_1}) \int _0^H \langle \overline {u_1^2} \rangle \mathrm{d}x_3$

also plays an important role to balance with the pressure gradient force. Afterwards, the flow approaches the fully developed condition at

![]() $x_1^*/H \approx 30$

where the total wall shear stress (

$x_1^*/H \approx 30$

where the total wall shear stress (

![]() $\tau _{{t}}-\tau _{{b}}$

) is equal to the pressure gradient force. The acceleration term vanishes in the fully developed flow region as expected, and the contribution of the streamwise diffusive term

$\tau _{{t}}-\tau _{{b}}$

) is equal to the pressure gradient force. The acceleration term vanishes in the fully developed flow region as expected, and the contribution of the streamwise diffusive term

![]() $\nu ({\mathrm{d}^2}/{\mathrm{d}x_1^2}) \int _0^H \langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle \mathrm{d}x_3$

is found to be insignificant (figures 10 and 11). A similar stress balance is also observed in case TR3 as shown in figure 11, however exhibiting a larger pressure drop due to the rougher surface at the top boundary. Moreover, the flow recovery is observed faster in case TR3 than in case TR2 due to additional turbulent mixing.

$\nu ({\mathrm{d}^2}/{\mathrm{d}x_1^2}) \int _0^H \langle \overline {u}_1 \rangle \mathrm{d}x_3$

is found to be insignificant (figures 10 and 11). A similar stress balance is also observed in case TR3 as shown in figure 11, however exhibiting a larger pressure drop due to the rougher surface at the top boundary. Moreover, the flow recovery is observed faster in case TR3 than in case TR2 due to additional turbulent mixing.

Figure 11. Same as figure 10 for case TR3. In contrast to case TR2, the flow is observed to approach the fully developed condition faster in case TR3.

A remarkable increase in the bottom shear stress

![]() $\tau _{{b}}$

is noticed upstream of the rough transition in cases TR2 and TR3 around

$\tau _{{b}}$

is noticed upstream of the rough transition in cases TR2 and TR3 around

![]() $x_1^*/H \approx 0$

, compared with the bottom shear stress

$x_1^*/H \approx 0$

, compared with the bottom shear stress

![]() $\tau _{{bS}}$

of the smooth transition case TS as seen in figures 10(b) and 11(b). In fact, the roughness condition of the carpet (in cases TR2 and TR3) enhances the bottom shear stress by two mechanisms: (i) the additional mixing or higher Reynolds shear stress near the rough wall pushes the position of maximum velocity further towards the smooth bottom wall, thus increasing the velocity gradient near the bottom wall, and (ii) the presence of the rough top boundary increases flow blockage, which leads to a slightly higher effective bulk velocity, resulting in a higher shear stress at the bottom boundary. The second mechanism is associated with streamline convergence and flow acceleration, inducing a downward mean flow in the vicinity of the carpet. Therefore, the presence of the rough carpet, which alters the open channel flow into the closed channel, is mainly responsible for this increase in

$\tau _{{bS}}$

of the smooth transition case TS as seen in figures 10(b) and 11(b). In fact, the roughness condition of the carpet (in cases TR2 and TR3) enhances the bottom shear stress by two mechanisms: (i) the additional mixing or higher Reynolds shear stress near the rough wall pushes the position of maximum velocity further towards the smooth bottom wall, thus increasing the velocity gradient near the bottom wall, and (ii) the presence of the rough top boundary increases flow blockage, which leads to a slightly higher effective bulk velocity, resulting in a higher shear stress at the bottom boundary. The second mechanism is associated with streamline convergence and flow acceleration, inducing a downward mean flow in the vicinity of the carpet. Therefore, the presence of the rough carpet, which alters the open channel flow into the closed channel, is mainly responsible for this increase in

![]() $\tau _{b}$

, and consequently may enhance possibly the bed erosion in the river. Such observations were reported in a study of ice-jams in a river by Luo et al. (Reference Luo, Ji, Chen, Liu, Xue and Li2025).

$\tau _{b}$

, and consequently may enhance possibly the bed erosion in the river. Such observations were reported in a study of ice-jams in a river by Luo et al. (Reference Luo, Ji, Chen, Liu, Xue and Li2025).

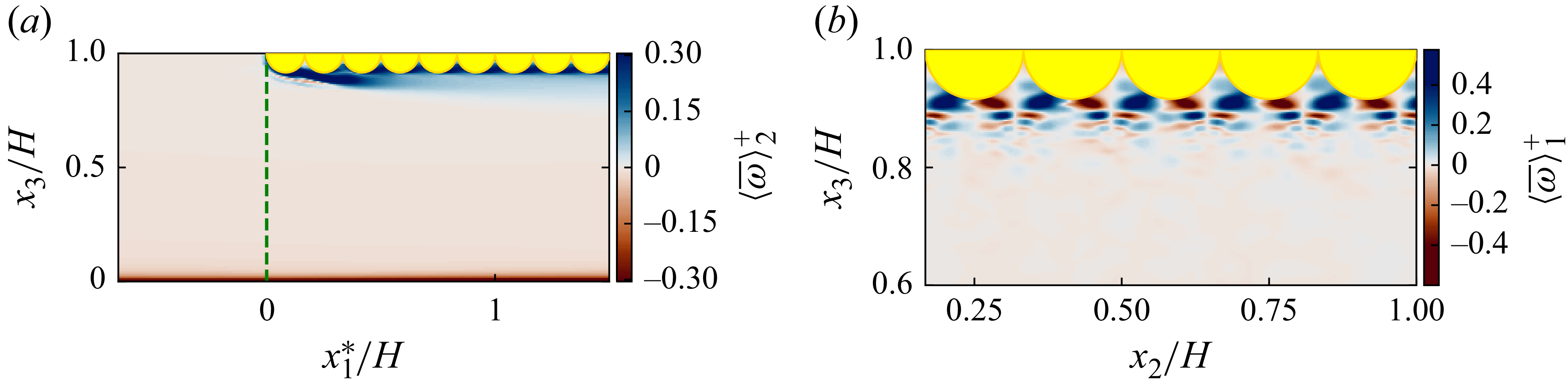

The above described phenomena are also reflected in the development of the turbulent kinetic energy (

![]() $K=\langle \overline { u_i' u'_i}\rangle /2$

) shown in figure 12 for case TR2. Near the transition (figure 12

a), high values of

$K=\langle \overline { u_i' u'_i}\rangle /2$

) shown in figure 12 for case TR2. Near the transition (figure 12

a), high values of

![]() $K$

are observed due to intense turbulent fluctuations or normal Reynolds stresses. In the closed-channel section (figure 12

b),

$K$

are observed due to intense turbulent fluctuations or normal Reynolds stresses. In the closed-channel section (figure 12

b),

![]() $K$

is generally higher near the rough top wall than near the smooth bottom wall because turbulent fluctuations are more intense due to the rough surface. The rougher top surface of case TR3 causes higher

$K$

is generally higher near the rough top wall than near the smooth bottom wall because turbulent fluctuations are more intense due to the rough surface. The rougher top surface of case TR3 causes higher

![]() $K$

and the smooth top surface of case TS produces a lower

$K$

and the smooth top surface of case TS produces a lower

![]() $K$

level, compared with case TR2. Moreover, the roughness of the top surface promotes the

$K$

level, compared with case TR2. Moreover, the roughness of the top surface promotes the

![]() $K$

level near the bottom boundary as well, implying that, in the case of a mobile bed, more erosion can be expected.

$K$

level near the bottom boundary as well, implying that, in the case of a mobile bed, more erosion can be expected.

Figure 12. Turbulent kinetic energy

![]() $K=\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle /2$

(a) upstream of the transition and (b) downstream of the transition of case TR2, normalised by the friction velocity of smooth open-channel flow, case OS. Due to the transition, higher

$K=\langle \overline {u_i' u_i'} \rangle /2$

(a) upstream of the transition and (b) downstream of the transition of case TR2, normalised by the friction velocity of smooth open-channel flow, case OS. Due to the transition, higher

![]() $K$

level is observed not only near the top boundary but also close to the bottom boundary, which in turn enhances the mixing processes and potentially increases sediment erosion. The effect of the transition on the bottom boundary is via the convection of vortex shedding from the top shown in figure 22.

$K$

level is observed not only near the top boundary but also close to the bottom boundary, which in turn enhances the mixing processes and potentially increases sediment erosion. The effect of the transition on the bottom boundary is via the convection of vortex shedding from the top shown in figure 22.

3.2. Skin friction

The friction coefficient for the carpet surface

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{{t}}$

is required to estimate the cumulative shear force acting on the carpet which is responsible for the squeezing instability, as discussed by Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). Though that study assumed fully developed flow conditions along the whole carpet, the flow transition from free slip to no slip in the presence of the carpet introduces non-negligible variation of friction coefficient along the streamwise direction, affecting the accurate estimation of the compressive force. Similarly, the friction coefficient at the bottom

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{{t}}$

is required to estimate the cumulative shear force acting on the carpet which is responsible for the squeezing instability, as discussed by Yan Toe et al. (Reference Yan Toe, Uijttewaal and Wüthrich2025). Though that study assumed fully developed flow conditions along the whole carpet, the flow transition from free slip to no slip in the presence of the carpet introduces non-negligible variation of friction coefficient along the streamwise direction, affecting the accurate estimation of the compressive force. Similarly, the friction coefficient at the bottom

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{b}$

determines the bed shear stress and the associated turbulence level present in the water column at the transition as explained in § 3.1.

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{b}$

determines the bed shear stress and the associated turbulence level present in the water column at the transition as explained in § 3.1.

In this section, we discuss the local friction coefficients varying with the local Reynolds number

![]() $ \textit{Re}^*=x_1^*U_{\textit{max}}/\nu$

. Unlike the common definition, the local skin friction coefficient

$ \textit{Re}^*=x_1^*U_{\textit{max}}/\nu$

. Unlike the common definition, the local skin friction coefficient

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is defined here as

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is defined here as

![]() $2\tau _w/(\rho U_{\textit{max}}^2)$

, where

$2\tau _w/(\rho U_{\textit{max}}^2)$

, where

![]() $\tau _w$

denotes the wall shear stress for any type of surface and

$\tau _w$

denotes the wall shear stress for any type of surface and

![]() $U_{\textit{max}}$

the maximum streamwise velocity of the fully developed flow of the corresponding cases. First, simulations with periodic streamwise and spanwise boundary conditions (i.e. cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3) provide benchmark values for the friction coefficient at the smooth bottom

$U_{\textit{max}}$

the maximum streamwise velocity of the fully developed flow of the corresponding cases. First, simulations with periodic streamwise and spanwise boundary conditions (i.e. cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3) provide benchmark values for the friction coefficient at the smooth bottom

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{b}$

and at the rough top

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{b}$

and at the rough top

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{{t}}$

, indicated by the different-coloured dashed lines in figure 13. Since the flow conditions in cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3 are fully developed flow, their friction coefficients do not vary with respect to

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}^{{t}}$

, indicated by the different-coloured dashed lines in figure 13. Since the flow conditions in cases CS, OS, CR2 and CR3 are fully developed flow, their friction coefficients do not vary with respect to

![]() $x_1^*$

. Moreover, the friction coefficients of smooth surfaces are found to be identical in the fully developed flow condition, regardless of any surface type at the other side of the channel, provided that the Reynolds numbers are the same. A small difference can be expected in the comparison if the maximum velocity is slightly different and its location is slightly displaced. This is observed in our results as well in figure 13(a), showing that three dashed lines for

$x_1^*$