Introduction

Capacity development is widely recognized as central to achieving development, conservation, and sustainability goals (UNDP, 2008; Bloomfield et al., Reference Bloomfield, Bucht, Martínez-Hernández, Ramírez-Soto, Sheseña-Hernández and Lucio-Palacio2018; Franco & Tracey, Reference Franco and Tracey2019). Investments in biodiversity conservation and sustainable development have been complemented by growing efforts to advance individual and organizational capacity (Bellamy & Hill, Reference Bellamy and Hill2010; Ling & Roberts, Reference Ling and Roberts2012; WCPA, 2015).

The need for conservation capacity development continues to grow and change. The next decade will be pivotal for leveraging the full potential of the global network of protected and conserved areas. Strengthening the effectiveness of existing protected areas (Eklund & Cabeza, Reference Eklund and Cabeza2016; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Mascia, Ahmadia, Glew, Lester and Barnes2017) and improving the management of new areas to internationally accepted standards will require investments to build new capacity, increase the competency of the existing workforce, and replace staff upon retirement (Coad et al., Reference Coad, Watson, Geldmann, Burgess, Leverington and Hockings2019). Ambitious species-specific goals also form part of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2020). With c. 32,000 species classified as threatened with extinction, this target will demand an exponential scaling up of global capacity.

There is also a pressing need to promote in-country capacity of government employees, local stewards and citizens (WCPA, 2015). Furthermore, the diversity of protected and conserved area governance models and the growing complexity of species conservation projects (McCool et al., Reference McCool, Freimund, Breen, Worboys, Lockwood, Kothari, Feary and Pulsford2015; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Davila, Toomey and Wyborn2017; Copsey et al., Reference Copsey, Black, Groombridge and Jones2018) have resulted in a broader constituency of people involved in protecting, managing and interpreting biodiversity. Part of the new complexity includes greater engagement with local stakeholders, including an extension of conservation benefits to meet their interests and needs, and planning jointly at a broader landscape scale with attention to local context and capacity development. In this context, collaborative and multi-stakeholder approaches, as well as locally led efforts, are strongly associated with conservation success (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Waylen and Mulder2013; Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Betley, Sigouin, Gomez, Toomey and Cullman2017, Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Coolsaet, Sterling, Loveridge, Gross-Camp and Wongbusarakum2021), and are becoming the norm for state actors, communities, businesses, user groups and academia (Margerum & Robinson, Reference Margerum, Robinson, Margerum and Robinson2016; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Miller, Goodman and Parker2018; Thomas & Mendezona Allegretti, Reference Thomas and Mendezona Allegretti2020).

New investments in capacity development should acknowledge the dynamic and interlinked nature of the social–ecological systems we live in and depend on. The conservation sector operates within complex systems (contexts with many parts that depend on and interact with each other), and practitioners increasingly seek to embrace their ecological, political, social and economic dimensions (Game et al., Reference Game, Meijaard, McDonald-Madden and Sheil2014; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cook, Redford, Biggs, Romero and Ortega-Argueta2019). As we strive to do so, the sector needs leaders and practitioners at all levels with the expertise to execute conservation action and act as systems thinkers, adaptive learners, conveners, network builders, collaboration brokers, effective communicators and innovators (Black & Copsey, Reference Black and Copsey2014; Sawrey et al., Reference Sawrey, Copsey and Milner-Gulland2017; Bruyere et al., Reference Bruyere, Bynum, Copsey, Porzecanski and Sterling2020).

Systems thinking is both ‘an approach to seeing the world and a set of methods and tools’, and comprises a set of complementary analytic skills that help us identify and understand systems, predict their behaviours and devise interventions according to our aims (Betley et al., Reference Betley, Sterling, Akabas, Paxton and Frost2021, p. 9). Seeing the world through a systems lens can make connections and relationships more visible and improve our decision-making abilities; systems thinkers ask broader questions and accept that often there is not a single solution to a problem but a set of linked actions that could guide a system towards a desired outcome (Betley et al., Reference Betley, Sterling, Akabas, Paxton and Frost2021). Using a systems lens to better understand the relationships and feedback loops between social and environmental dimensions can prepare individuals to work effectively in complex and changing contexts, and ultimately to transform the systems that drive biodiversity loss and unsustainable, inequitable resource use and its impacts (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard and Arneth2019). To meet these challenges, the conservation sector is not only in need of more capacity development, it is in need of new approaches to capacity development.

The author team comprises capacity development practitioners and researchers based in the USA, UK, Peru and Madagascar. Our practice has been informed by substantive capacity development engagements in 106 countries over the course of our careers, representing 260 years of combined experience. Here we discuss what we consider to be some of the most persistent challenges in conservation capacity development and propose a broad conceptual framework to guide capacity development planning and evaluation. Our analysis and proposed framework are based on our joint experience, discussions and lessons learnt, as well as a review of practices from conservation and other sectors.

Persistent conservation capacity development challenges

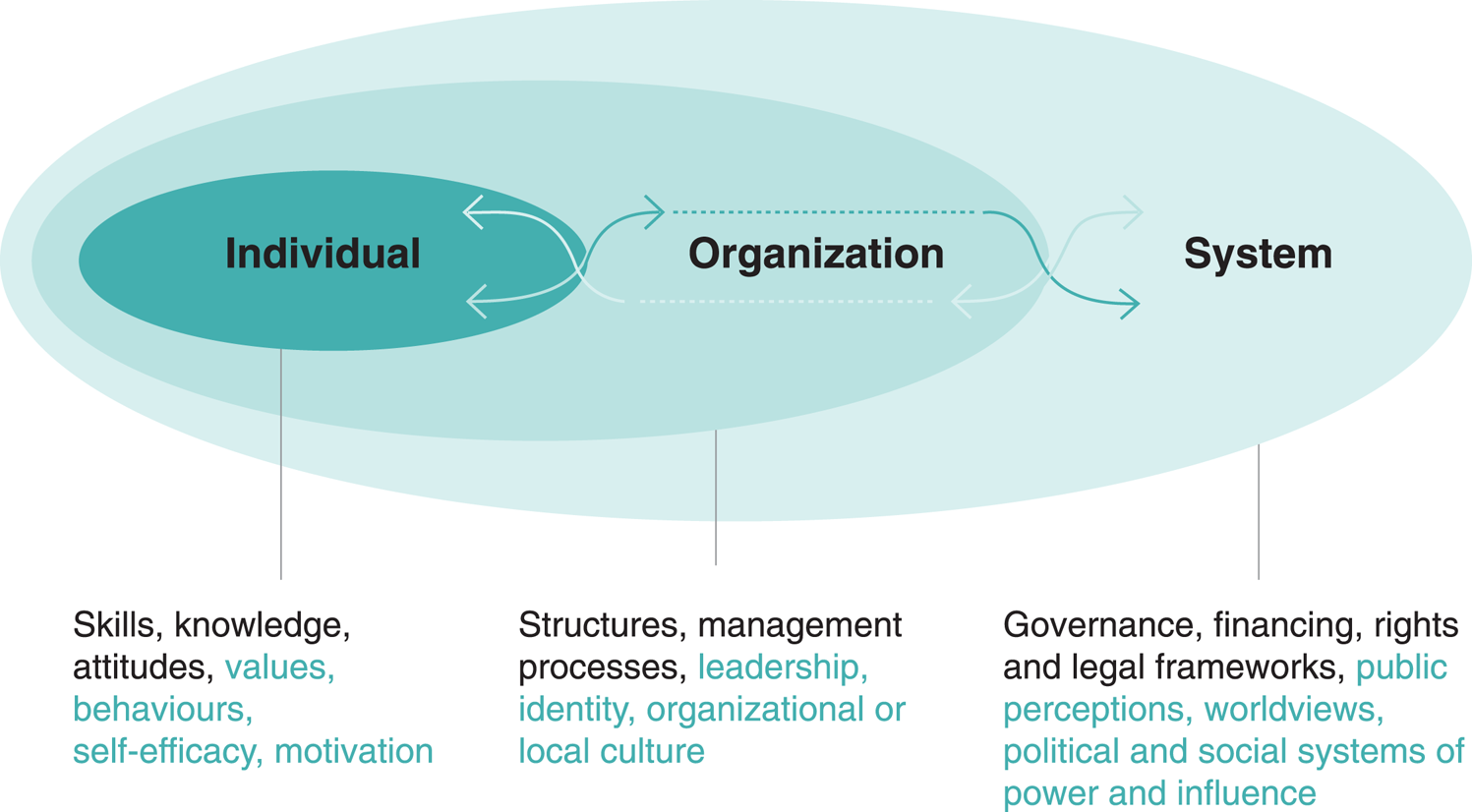

Current models guiding capacity development recognize that actions are required at multiple levels, from individuals to society (OECD, 2006; CADRI, 2011). These models encompass an individual, an organizational and a societal or system level. The individual level encompasses the attitudes, skills and knowledge, as well as motivation and self-efficacy (the belief in one's own ability to perform a particular task or skill), that are present in individuals. The organizational level encompasses rules, systems and structures within collective contexts, such as diverse organizations, collaborations and local communities. These include leadership dynamics, evolving workplace cultures, and the ability to produce results and to adapt to change, as well as to provide relevant rewards and incentives. Societal systems act as an enabling environment for capacity development: they are the cultural, social, political, financial/economic, legal and environmental contexts in which individuals and organizations operate, providing both constraints and opportunities (UNDP, 2008; CADRI, 2011; Fig. 1). A range of capacity development activities are typically carried out at each of these levels (Table 1).

Fig. 1 Practitioners recognize the need to address capacity at multiple levels (represented in this figure by ovals; see text for details). These levels are nested and connect in multiple ways and directions (shown by arrows depicting both direct and indirect linkages as solid and dashed, multidirectional lines, respectively). Relevant dimensions of capacity at each level are indicated below each oval; some are often recognized and targeted (black text), whereas others are less visible and have traditionally received less attention (lighter text).

Table 1 Examples of methods for developing capacity at the individual, organization and community, and societal levels. Although many of these approaches can be used at all three levels, we have listed them here under the level where they are most commonly employed. For useful illustrations of some of these methods see WCPA (2015), Bloomfield et al. (Reference Bloomfield, Bucht, Martínez-Hernández, Ramírez-Soto, Sheseña-Hernández and Lucio-Palacio2018), Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cook, Redford, Biggs, Romero and Ortega-Argueta2019) and O'Connell et al. (Reference O'Connell, Maru, Grigg, Walker, Abel and Wise2019a).

Although practitioners recognize linkages between individuals, organizations and societal systems, as well as the need to strengthen capacity at these multiple levels, we argue that prevailing planning, evaluation and learning practices in conservation capacity development currently limit our ability to assess effectiveness at each of these levels, and to learn from implementation. Here we discuss two persistent challenges we have identified pertaining to conservation capacity development.

The need to understand context and clarity of purpose in planning stages

Under a so-called ripple model, the impacts of interventions at the individual level are expected to be far-reaching over time (James, Reference James2009). In our experience, this model informs prevailing planning philosophies such that capacity development interventions target singular aspects of the wider system (predominantly individuals), frequently with an implicit belief that this will lead to change throughout other parts of the system.

Capacity development efforts have documented the advancement and increasing influence of individuals trained over time as they come to occupy leadership positions (e.g. Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Porzecanski, Valdés-Velásquez, Aguirre, Aguilera, Arrascue, Aguirre, Sukumar and Medellín2016; Sawrey et al., Reference Sawrey, Copsey and Milner-Gulland2017), but connections to biodiversity outcomes are infrequently documented or evaluated, making it challenging to assess whether a ripple effect occurs. The field would benefit from clearer definitions of capacity targets, envisioned capacity outcomes, as well as the alignment between these and conservation outcomes.

In addition, capacity development programmes are often short-term or centred on single events as opposed to longer-term processes, planned with a limited understanding of local needs and priorities, or in isolation from other related efforts. This can stem from the need to work efficiently, with limited resources and under tight project timescales, but can reduce impact and relevance or even cause unintended harm. For example, the Game Rangers Association of Africa has expressed concerns regarding militarized training of rangers, in which foreign and/or military contractors can lack understanding and appreciation of the political, cultural and social environment in which local rangers operate (GRAA, 2017). A broader lens that involves an understanding of the governance and social-cultural context would provide more opportunities to design actions that are the best fit for a given context, share lessons and coordinate actions with sectors beyond conservation.

Increased attention is needed regarding how we can effectively target, measure and support less visible but vital elements of capacity, such as values and motivation, leadership and organizational culture, and governance, by using approaches from psychology and the social sciences. Indicators of psychological capacity such as meaningful ownership, effective autonomy and feeling needed are informative regarding capacity at the individual level and increasingly recognized in conservation (Black & Copsey, Reference Black and Copsey2014; Cranston, Reference Cranston2016). At a collective level, capacity can be targeted and assessed using indicators of organizational or community capacity. Mumaw et al. (Reference Mumaw, Maller and Bekessy2019) for example, proposed a systems-based framework for community capacity with indicators in five categories: human capital, socio-cultural capital, natural capital, economic capital and conservation action. At a societal level, we see a need for diverse indicators that assess collective capacity to target and measure those aspects of human–environmental systems that affect biodiversity loss. Narrow assumptions about collective values and motivations, omissions or limited framings can lead to missed opportunities for crucial capacity development. For example, Agol et al. (Reference Agol, Latawiec and Strassburg2014) have examined context-specific sustainability indicators (i.e. income-generating activities, presence of community-based groups, welfare index, disease incidence, women's leadership). Similarly, Sterling et al. (Reference Sterling, Pascua, Sigouin, Gazit, Mandle and Betley2020) have highlighted important dimensions contributing to sustainability that are overlooked in many global metric frameworks. Finally, including different systems of knowledge and learning (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Eckert, Lane, Young, Hinch and Darimont2021) in capacity development would enrich these initiatives, diversify measures of success and reduce some of the barriers to the exchange of information, skills and practices.

Evaluating for outcomes and impact

The evaluation of capacity development is evolving. There is a desire to document results beyond outputs, towards outcomes and system impacts, but in our experience this has proved challenging. It is common for a project to target individuals with the intention of producing conservation or organizational gains, but then report only on outputs (e.g. people trained or events held) or the results of specific activities (e.g. satisfaction with a given course) with no subsequent evaluation of larger or longer-term impacts (Simister & Smith, Reference Simister and Smith2010). Given that individuals are likely to participate in multiple capacity development events over time, it is more realistic to document contributions to outcomes than to attribute such changes to specific interventions (Mayne, Reference Mayne2008; Simister & Smith, Reference Simister and Smith2010; Vallejo & Wehn, Reference Vallejo and Wehn2016), something that both practitioners and donors should take into account. A broader, or systems lens on evaluation would assess capacity development impacts across capacity levels, how changes within levels influence each other, and what is needed for systemic change to occur (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cook, Redford, Biggs, Romero and Ortega-Argueta2019).

Some recent evaluations of long-running capacity development programmes reveal the critical role of context, or the enabling environment, which can either facilitate or act as a constraint to change (see below, and Table 2). For example, such barriers may take the form of recruitment, promotion, inclusion and retention policies. A recent evaluation of a long-term training programme in Mauritius shows that if a trainee's work environment was negative, the impact of training on practical skills, job performance and trainee perception of control was lower (Sawrey et al., Reference Sawrey, Copsey and Milner-Gulland2017). Multi-level, longer-term evaluation frameworks would help shed light on the existence of organizational and/or systemic barriers that must be addressed for the potential of individual capacity gains to be fully realized. In summary, we see critical needs and opportunities to adapt how we currently plan, evaluate and learn from capacity development practice in conservation.

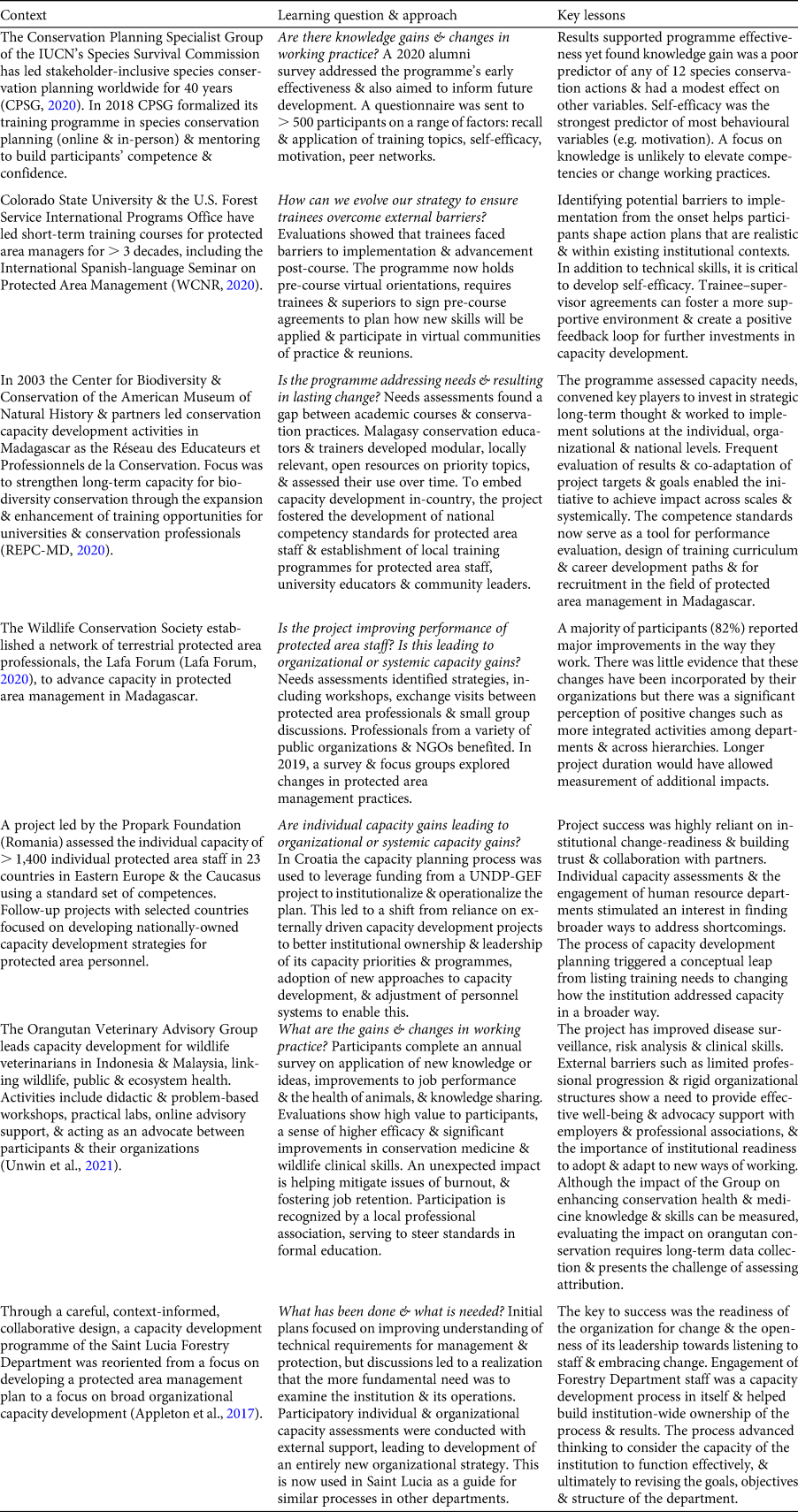

Table 2 Examples of conservation capacity development initiatives that have used double or triple loop learning to examine effectiveness and system-wide implications, and key lessons learnt.

A broader conceptual framework to guide capacity development planning and evaluation

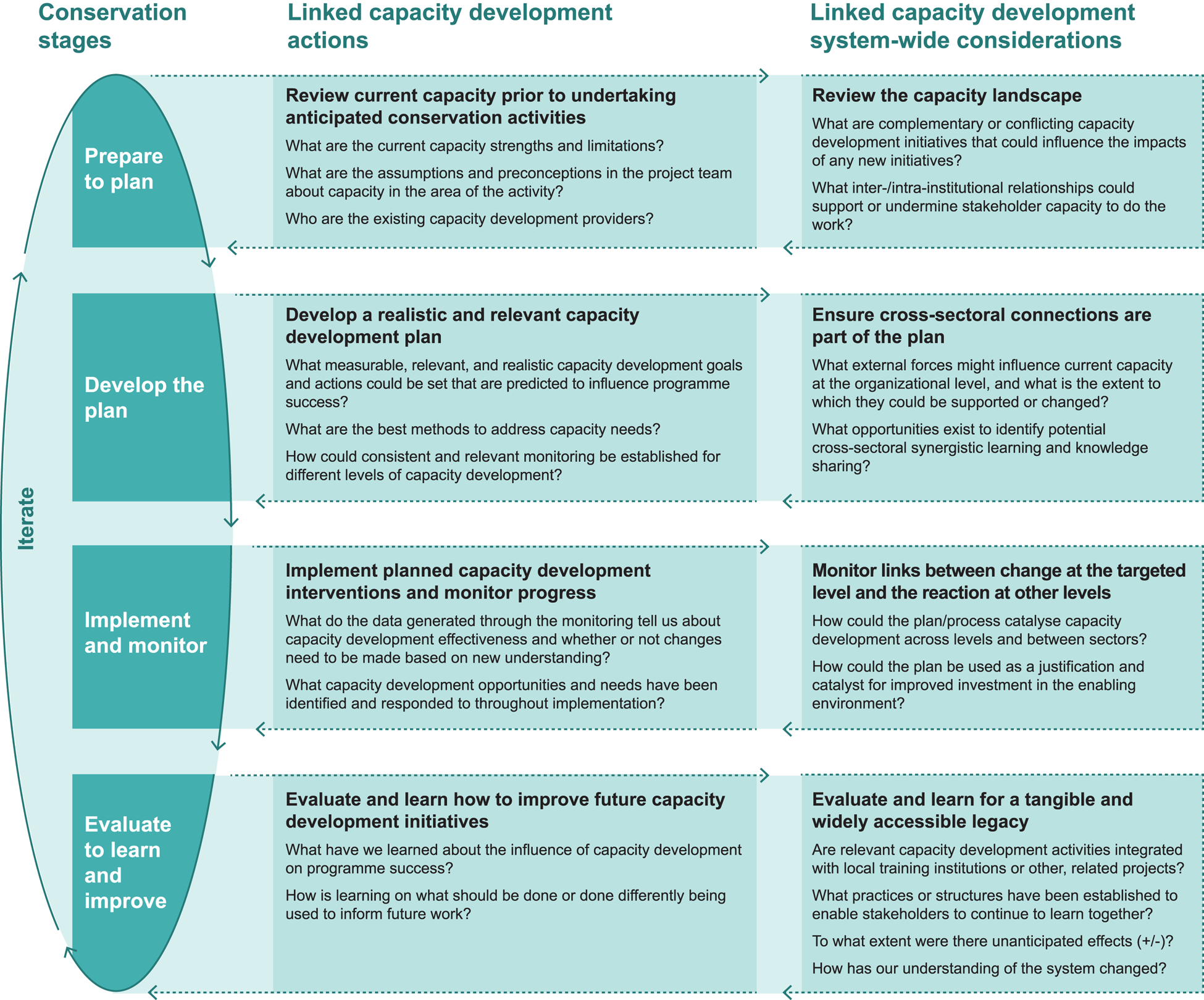

Based on our collective experience and our review of practices from conservation and other sectors, we have organized these ideas into a framework, comprising four stages: preparing, planning and designing, implementing and monitoring, and evaluating and learning (Fig. 2). Our framework is informt by lessons learnt from capacity development efforts in other fields, including health/medicine (LaFond et al., Reference LaFond, Brown and Macintyre2002) and economic development (Ling & Roberts, Reference Ling and Roberts2012) as well as literature on learning loops and their application to natural resource management (Kohl & McCool, Reference Kohl and McCool2016), which provide useful ideas for practitioners in the conservation arena.

Fig. 2 A conceptual framework for an iterative, multi-loop learning process for conservation and capacity development planning, implementation and evaluation. The framework lays out guiding questions that can help connect conservation actions at different stages to capacity development actions and cross-level, cross-sectoral considerations, to catalyse learning at multiple levels during the capacity development process. For our purposes we view a stakeholder as being an individual or an organization that has a vested interest in or power over the plan to be implemented.

Discussion

The framework builds on established steps for planning and programme implementation such as adaptive management (McCarthy & Possingham, Reference McCarthy and Possingham2009; Keith et al., Reference Keith, Martin, McDonald-Madden and Walters2011), the Conservation Standards (CMP, 2020), international guidelines for species conservation planning (IUCN-SSC, 2017), and the principles and steps that underpin participatory planning approaches. The framework aims to foster capacity development efforts that are: (1) aligned and interwoven with the planning and implementation of conservation activities, and (2) conceived using a systems lens, such that efforts consider pre-existing and concurrent efforts, as well as other levels of influence (individuals, organizations, societal systems) as both important context and an opportunity for impact.

If we have reason to believe that achieving conservation outcomes requires coordinated capacity change at multiple levels of a system, or across sectors, then we need to be more explicit in designing and evaluating capacity development activities in this way, a radical departure from how conservation capacity development is typically carried out. Causal models, or theories of change (models that ‘detail the logic and assumptions around how a series of interdependent steps will lead to intended outcomes’; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, McKinnon, Masuda, Garside, Jones and Miller2020, p. 2), are a potentially helpful way to make our expectations explicit about the effects of an intervention and the role of all actors in a system. Theories of change need to be well-defined, and their assumptions and pathways should be logical and plausible (Aragón, Reference Aragón2010; Mayne, Reference Mayne2017; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, McKinnon, Masuda, Garside, Jones and Miller2020). However, capacity development causal models currently tend to focus mostly on individuals, presenting a bias towards the more visible aspects of capacity, such as training for knowledge gains, application or strategic planning (e.g. see capacity development theories of change in the Conservation Actions & Measures Library; CAML, 2020).

Another useful idea, that of learning loops (Argyris, Reference Argyris1977; Hargrove, Reference Hargrove2002), has been increasingly applied to natural resource management to capture the need for different kinds of learning (see Kohl & McCool, Reference Kohl and McCool2016; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Maru, Grigg, Walker, Abel and Wise2019a). Authors identify three kinds of learning loops: single loop learning adjusts and refines existing practices (i.e. asks: Are we doing things right? Are we efficient?), and double loop learning reframes or reforms assumptions, goals and strategies (Are we doing the right things? Are we effective?). Finally, triple-loop learning entails questioning our goals and assumptions about the way things are and should be, and leads to further transformation of worldviews and values (Are we pursuing the right outcomes? Are we asking the right questions?). The framework and questions for practitioners that we present here aim to foster learning along all three loops.

Practitioners from the field of human development have framed capacity development as a complex process of change, with a focus on individuals or groups as change agents, perhaps not ripples activated by an external intervention but rather capable of initiating and generating their own ripples, and even chain reactions. In recognition of the long timeframes of capacity development, there is an increasing focus on monitoring and evaluating intermediate capacity outcomes that can facilitate or drive further change. The World Bank Institute defines these as ‘improvements in the ability or disposition of the local change agents to take actions that will effect institutional changes towards a development goal’ (Ling & Roberts, Reference Ling and Roberts2012, p. 15). They illustrate six types of intermediate capacity outcomes: raised awareness, enhanced knowledge or skills, improved consensus and teamwork, strengthened coalitions, enhanced networks and new implementation know-how. Combined with resources (financial, human, technology and infrastructure), these types of outcomes are expected to lead to changes in institutional capacity over longer time frames yet can be assessed in the medium term, and could be useful for conservation.

In conservation, we see capacity development practitioners using double loop learning through adaptive management and reflection (Manolis et al., Reference Manolis, Chan, Finkelstein, Stephens, Nelson and Grant2009; Black, Reference Black2019). There is also a growing emphasis on assessing results in terms of both outputs and outcomes (Howe & Millner-Gulland, Reference Howe and Milner-Gulland2012). Some practitioners are striving to measure learning and competence outcomes beyond outputs, including whether the learning was retained and applied later (Sawrey et al., Reference Sawrey, Copsey and Milner-Gulland2017).

In addition, there is increasing reflection about the capacity development methods used, the things we are doing, because as conservation strategies diversify, methods may not be optimal for the full diversity of participants. For example, many capacity development activities aimed at protected area management or species conservation have focused on short-term, one-off training events, or on academic programmes (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Ryan and Wyborn2018), which often focus on research training. Although this strategy is adequate for some capacity development objectives, it may not be effective for all. Training courses continue to have an important role, and additional approaches to learning such as mentoring and regional networks can fulfil a learning need that formal training courses cannot (Pietri et al., Reference Pietri, Stevenson and Christie2015; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nasirwa, Carter, Farmer, Appleton and Arinaitwe2019b).

We recommend that practitioners reflect on their work by asking questions at each stage of conservation to promote a broader lens for the design, implementation and evaluation of capacity development in conservation; illustrative questions are included in Fig. 2. We have aimed to include triple loop questions in our framework through cross-level considerations and stage 4, Evaluate to learn and improve (Fig. 2). Sterling et al. (Reference Sterling, Sigouin, Betley, Zavalata Cheek, Solomon and Landrigan2021) provide an analysis of the current state of capacity development evaluation, and highlight the need for systems approaches to evaluation that explore the links between interventions and effects at other levels, including effects on biodiversity and other outcomes. The considerations and questions outlined in our framework can help orient practitioners towards envisioned outcomes, and encourage the monitoring of peer efforts, consideration of broader contexts and evaluation at all levels through cycles of reflection and learning (Manolis et al., Reference Manolis, Chan, Finkelstein, Stephens, Nelson and Grant2009). The framework is meant to be applied in an iterative way, promoting evaluation cycles.

To connect these ideas to capacity development practice, we have compiled selected, illustrative examples of conservation capacity development projects to explore how they have applied double and triple loop learning (Table 2). These examples support the practitioner recommendations presented in the framework and highlight several lessons for practitioners. A number of examples support targeting more than gains in knowledge and technical skills and highlight the importance of monitoring dimensions such as individual confidence and self-efficacy, and even the holistic well-being of practitioners. Most examples also demonstrate a need to engage with the broader context of the work and with stakeholders in all stages. This is especially important in capacity development, given that important barriers to efficacy can stem from rigid or organizational cultures and structures.

Several of the examples demonstrate the enabling influence of learning spaces where it is safe to experiment and try out new methods, tools and practices within organizations and across them, through networks. The readiness for change of organizations and systems should be an important focus for conservation moving forward. This can be advanced by both practitioners and donors by promoting monitoring and evaluation approaches that focus on learning, and include learning from failure (Redford & Taber, Reference Redford and Taber2000; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cook, Redford, Biggs, Romero and Ortega-Argueta2019).

Conclusion

As we face a shifting understanding of the social and ethical context for conservation, updated modes of leadership, and the limitations of conventional planning practices for the complexities and needs of our time, there is a pressing need to evolve capacity development practice in conservation. Our aim was to highlight how this new understanding can apply to capacity development planning, spark discussion of an initial conceptual model, and promote its testing and refinement in the design and delivery of programmes. The framework we present here describes conservation capacity development as a cyclical and ongoing process that includes opportunities for stakeholders to engage in collective reflection and learning from experience. Convening together, for instance through ongoing communities of practice at local and regional scales or through dedicated gatherings for directed reflection could help create spaces for this type of collective exchange.

The hard questions inherent in double and triple loop learning demand significant time, attention and resources, possibly resulting in major restructuring, and diverting time from other activities. Yet some of the most fundamental questions around conservation capacity development are double and triple loop questions: Does capacity development contribute to achieving conservation goals? Does the evidence demonstrate it leads to impact? Does it empower individuals and organizations to lead transformational change? Asking, and endeavouring to answer, these questions will strengthen the case for capacity development and its value, as well as conservation practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues at the IUCN World Commission of Protected Areas and our institutions, who have discussed these ideas with us over the years. We thank N. Gazit for valuable assistance with figures, and the Editor and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments. This research received no specific grant, commercial or not-for-profit funding.

Author contributions

Developing the content, writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.